1. Introduction

As a naturally abundant material with high thermal insulation and load-bearing capacity, snow offers a unique construction medium in environments where conventional building resources are scarce or difficult to transport. Indigenous peoples, notably the Inuit, have used snow to build semipermanent structures such as igloos for centuries, leveraging its compacted strength and insulating qualities [1]. More recently, architects and designers in countries like Norway, Finland, and Canada have explored snow and ice as eco-friendly construction materials for seasonal tourism infrastructure such as ice hotels, snow restaurants and bars, as well as emergency shelters [1]. This traditional knowledge has evolved into a growing field of research encompassing the strategic use of snow in military and scientific applications.

For military operations in Arctic and subarctic regions, snow fortifications offer significant logistical advantages. Research by the US Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) has advanced our understanding of snow’s structural behavior under varying conditions, including blast resistance and dynamic loading [2,3]. These insights have informed the design of compacted snow runways, foundations, and protective berms [4] (pp. 1-11). Scientific research, particularly in the context of climate-resilient infrastructure, has focused on how snow and ice can be stabilized or enhanced using additives like biodegradable fibers to extend the life and safety of snow-based structures in changing weather conditions [2,5,6].

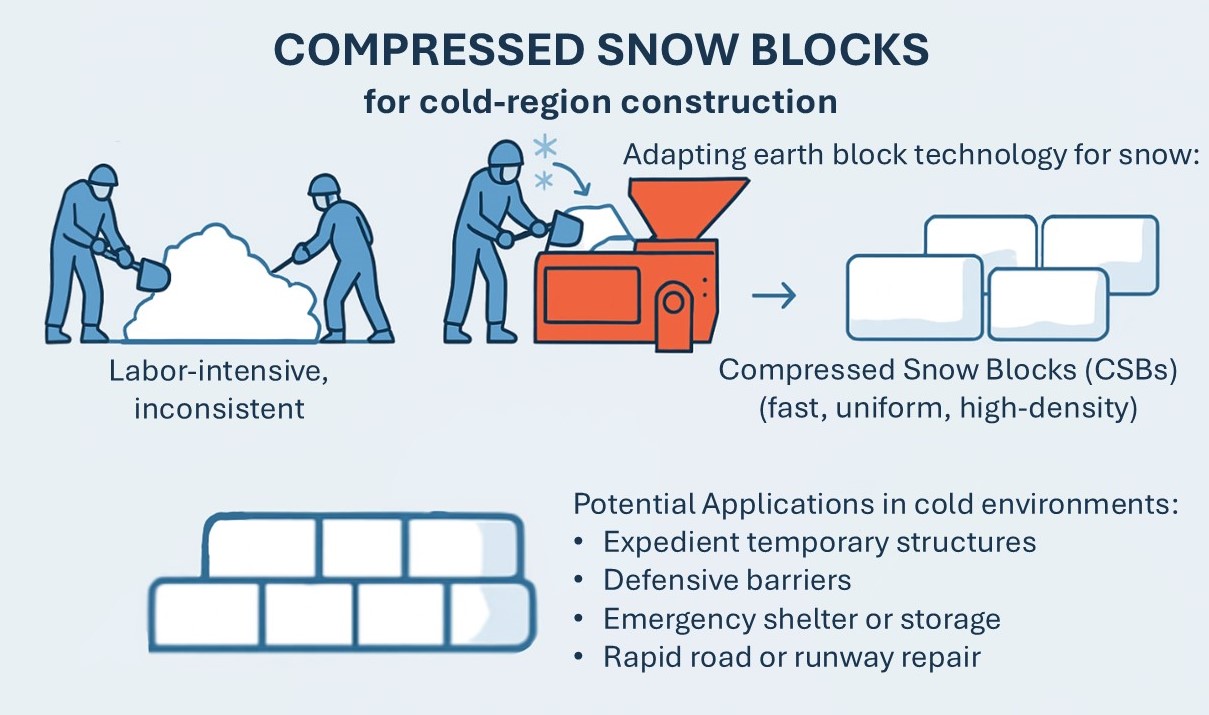

While snow fortification has traditionally relied on manual methods such as shoveling, piling, and compacting snow into forms or molds, these techniques are labor-intensive and can produce variable results depending on snow type, temperature, and operator experience (Blaisdell et al. 2021). In military or emergency scenarios where speed, uniformity, and structural reliability are critical, the current ad hoc methods of building snow walls, windbreaks, or shelters can pose limitations. A novel and promising approach involves the adaptation of compressed earth block (CEB) machines for use with snow. CEBs have a long-standing history as a sustainable building material across a range of climates and cultures. Originating from ancient earthen construction techniques (e.g., adobe) seen in regions such as Zimbabwe and Britain [7] (pp. 259-271), CEBs are made by mechanically compacting a mixture of soil, stabilizers, and sometimes cement into dense, modular units [8,9] (pp. 1-9; pp. 47-55). These blocks offer high thermal mass, fire resistance, and low embodied energy, making them attractive for both rural development and environmentally conscious urban projects [8] (pp. 1-9). Modern applications of CEBs span humanitarian housing initiatives, low-cost construction in developing nations, and innovative green architecture in urban settings.

By modifying these devices to operate effectively in subfreezing temperatures and to accommodate the unique physical properties of snow, it may be possible to produce compressed snow blocks (CSBs) with consistent density, shape, and strength. These blocks could serve as modular units for rapid, scalable snow construction in both military and civilian contexts. The application of CSBs over traditional shovel- or hand-packed snow could improve load-bearing capacity, lead to faster assembly times, and the potential for prefabrication. For example, CSBs could be stockpiled and transported short distances for use in building perimeter defenses, thermal shelters, or temporary infrastructure like storage igloos, bunkers, and explosive detonation structures. Additionally, integrating water or slush into the compaction process could allow the blocks to partially freeze into ice upon setting, further enhancing structural integrity. This hybrid approach mirrors recent techniques in snow architecture where water is sprayed onto snow forms to increase hardness and longevity [2]. Research studies and field experiments have long explored mechanized snow compaction methods, though to our knowledge, none have directly applied existing CEB press technology to snow.

The objective of this study is to learn how to operate a traditional CEB machine and investigate the feasibility of using it with snow to produce CSBs (i.e., modular and mechanically compacted snow units) as an alternative to traditional snow compacting methods for construction and fortification applications. Specifically, this study aims to answer two main questions: 1) can a CEB machine produce CSBs when snow is applied to the system, and 2) are the resulting blocks unform in size and density? If successful, CSBs could offer several advantages in cold region construction and fortification, such as improved consistency and efficiency, enhanced strength and durability, and scalability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CEB Machine

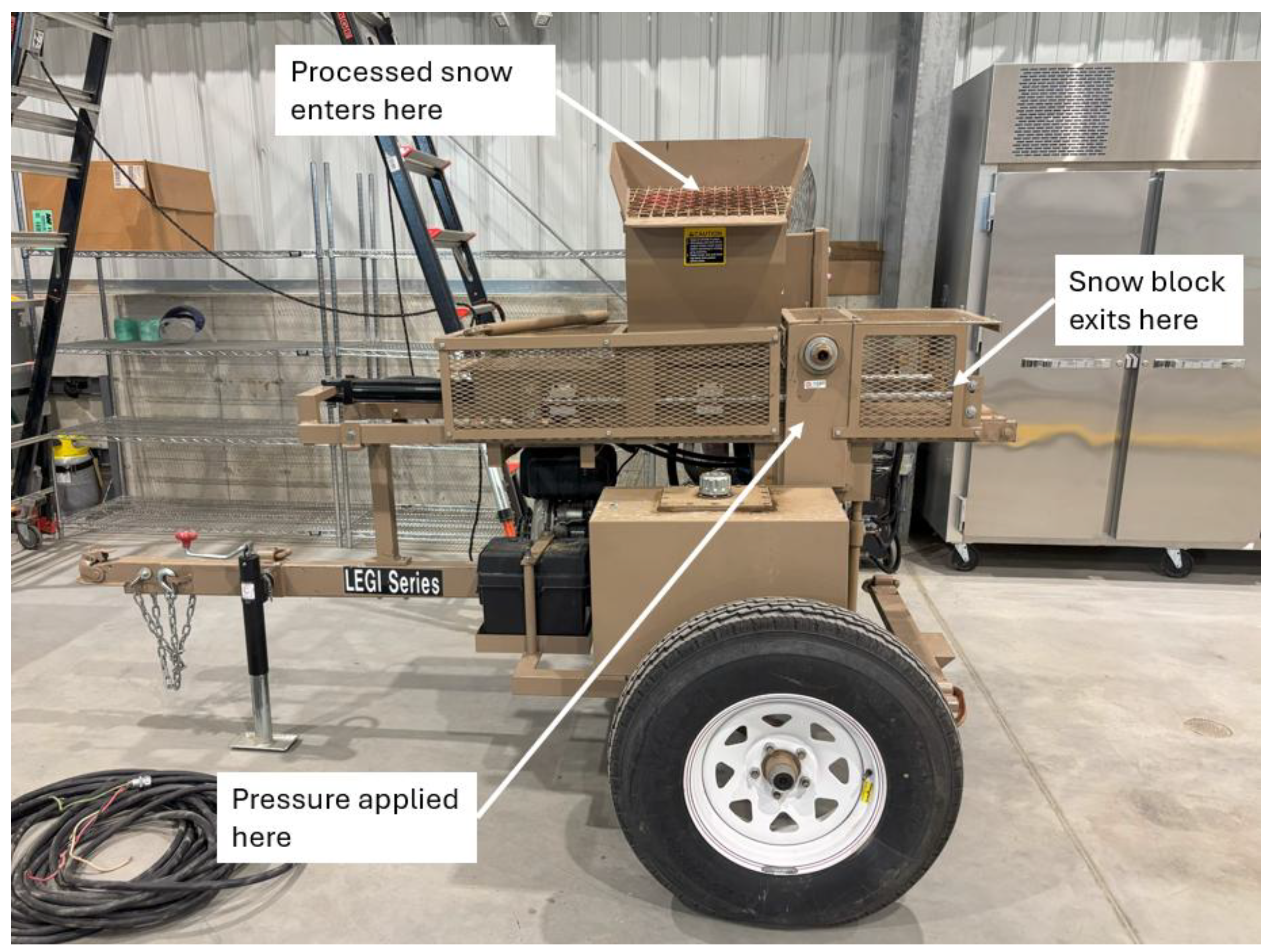

To evaluate the viability of producing CSBs using existing CEB technology, this study utilized the Impact 2001A hydraulic press manufactured by Advanced Earthen Construction Technologies (AECT; San Antonio, Texas, USA) (

Figure 1). Originally designed for the compaction of soil-based materials, the Impact 2001A features a steel mold box and piston assembly capable of generating significant compressive force, making it a suitable candidate for initial trials with snow. We used an existing soil block compactor from the US Army Geotechnical and Structures Laboratory (GSL) to test and create methods specifically for applying this block machine in cold weather.

The operational mechanism of the Impact 2001A is described in Burroughs et al. (2015) [9]. In brief, it is a trailer-mounted automated machine that efficiently produces CEBs at a rate of four blocks per minute, with each block measuring 30.48 cm long and 15.24 cm wide, with an adjustable height between 5.08–11.43 cm tall. It operates using a diesel-powered engine, compressing manually loaded soil under up to 20,684 kPa of pressure to form durable blocks. The machine features an adjustable hydraulic ram, allowing users to control block thickness (i.e., block height) based on soil moisture, which influences final dimensions. With an automated pressing and ejection system, it continues production if soil is continuously supplied. Per discussion with the manufacturer, it may be possible to modify parameters of the block machine such as the block size, maximum applied pressure, size of the equipment itself, how it is mounted (e.g., trailer mounted vs. stand-alone), reorganization of electrical components to protect from increased moisture conditions, and changes to the motor including a cold weather start and the ability to support the flashpoint of JP8 fuel for use in extreme cold environments.

2.2. Proof-of-Concept Field Test

A field trial was conducted at CRREL in Hanover, New Hampshire, following a period of sustained subfreezing temperatures (i.e., 4 days) to ensure snow stability during handling and compression. The snow used was naturally occurring, sourced from undisturbed, previously accumulated material next to one of the CRREL buildings. To improve the consistency and flowability of the snow prior to compaction, a gas-powered snowblower (Honda HS828 Snowblower, Torrance, California, USA) was employed to mechanically break down and disaggregate the snow particles (

Figure 2) [1] (pp. 311-320). This process helped create a more uniform particle size and moisture distribution, enhancing its workability during subsequent handling. Processing also allows the snow to restart the sintering process to increase strength uniformity throughout the block and increase strength gain capability [2,3]. Following snow processing, the material was manually shoveled into the feed hopper of the Impact 2001A, where it was compacted into blocks using the machine’s standard operation cycle at the maximum operating pressure of 20,684 kPa (per recommendation by AECT). Given that the machine was not originally designed for low-temperature operations or for compressing fine, cold particulate matter like snow, special attention was paid to machine performance, material ejection, and any mechanical sticking or jamming during pressing cycles.

Unlike traditional applications of the CEB machine, no stabilizers, additives, or moisture controls were applied to the snow. The primary focus of this study was to assess the machine’s ability to produce structurally intact CSBs using unmodified natural snow. Because of equipment and time constraints due to weather and resulting snow availability, the only quantitative data collected from each block were the dimensions (length, width, and height), weight, and density (calculated as mass divided by volume). Long-term strength and durability were not assessed as part of this initial phase. The collected data and metrics served as the basis for evaluating consistency and comparing outputs and uniformity across multiple blocks. In addition, preliminary observations focused on identifying necessary modifications or operational adjustments that could improve block formation and reliability. This proof-of-concept study served as the foundation for assessing both the technical feasibility and the logistical practicality of using mechanized compaction to produce snow-based construction units in cold region environments.

3. Results & Discussion

A total of 25 CSBs were produced throughout the field test process of learning how to operate the piece of equipment. One of the main objectives of this test was to learn how to operate and adjust the Impact 2001A as needed, specifically the block height adjuster (the block length and width are fixed). Through this process, we observed that following initial startup and after making any adjustment to the block height during the operational cycle, the following 3–4 produced were not the correct block height. This was a valuable observation to note for future testing that it takes 3–4 operational cycles to achieve the new block height set on the machine. These blocks were thereby considered “unsuccessful” as they tended to be half of the intended block height or less and were set aside (

Figure 3). After these first 3–4 unsuccessful blocks, the machine would return to a steady state cyclic mode wherein blocks of consistent height were produced. In addition, structural failures (e.g., block collapse or chipping) were observed upon ejection from the block machine, and these were also set aside. After learning these operational limitations of the machine and excluding any failed block and those produced immediately following system startup or block height adjustment, 8 “successful” blocks remained (

Figure 4). These 8 were produced with a block height setting of 7.62 cm, were immediately measured, and then weighed approximately 45 minutes after being ejected from the machine. The collected data were used to calculate the density of each block, and to evaluate uniformity across blocks, offering insight into the variability and compactness achievable with mechanized snow compaction.

Preliminary observations indicate that the Impact 2001A is capable of producing dimensionally consistent CSBs after accounting for the first few cycles following start up and block height adjustment. The mean block height was 7.76 cm (± 0.56 cm) and the actual block height for all 8 blocks was within 1 cm of the intended block height (i.e., block height set on the machine) (

Table 1). Mean block mass was 3288.54 g (± 296.95 g), with block mass generally increasing with block height except for Block E which was nearest to the average block height, but had the greatest mass along with Block H. Slight variations in blocks were noted, most likely due to uneven snow loading into the hopper and the presence of impurities in the snow (e.g., small amounts of soil or small gravel from the surrounding collection areas). As described in

Section 2, the processed snow was manually added to the hopper using a shovel. Unfortunately, there was no way to ensure a perfectly even distribution of the snow across the bottom opening of the hopper where the snow would fall into the compression chamber during the operational cycle. Also mentioned in

Section 2 was that the Impact 2001A machine was borrowed from another lab who used it for extensive soil testing (as that is the traditional material for CEBs). As a result, there was residual soil or sediment in the machine despite cleaning prior to adding snow, making the CSBs produced with the machine to appear dirty or orange or brown in color.

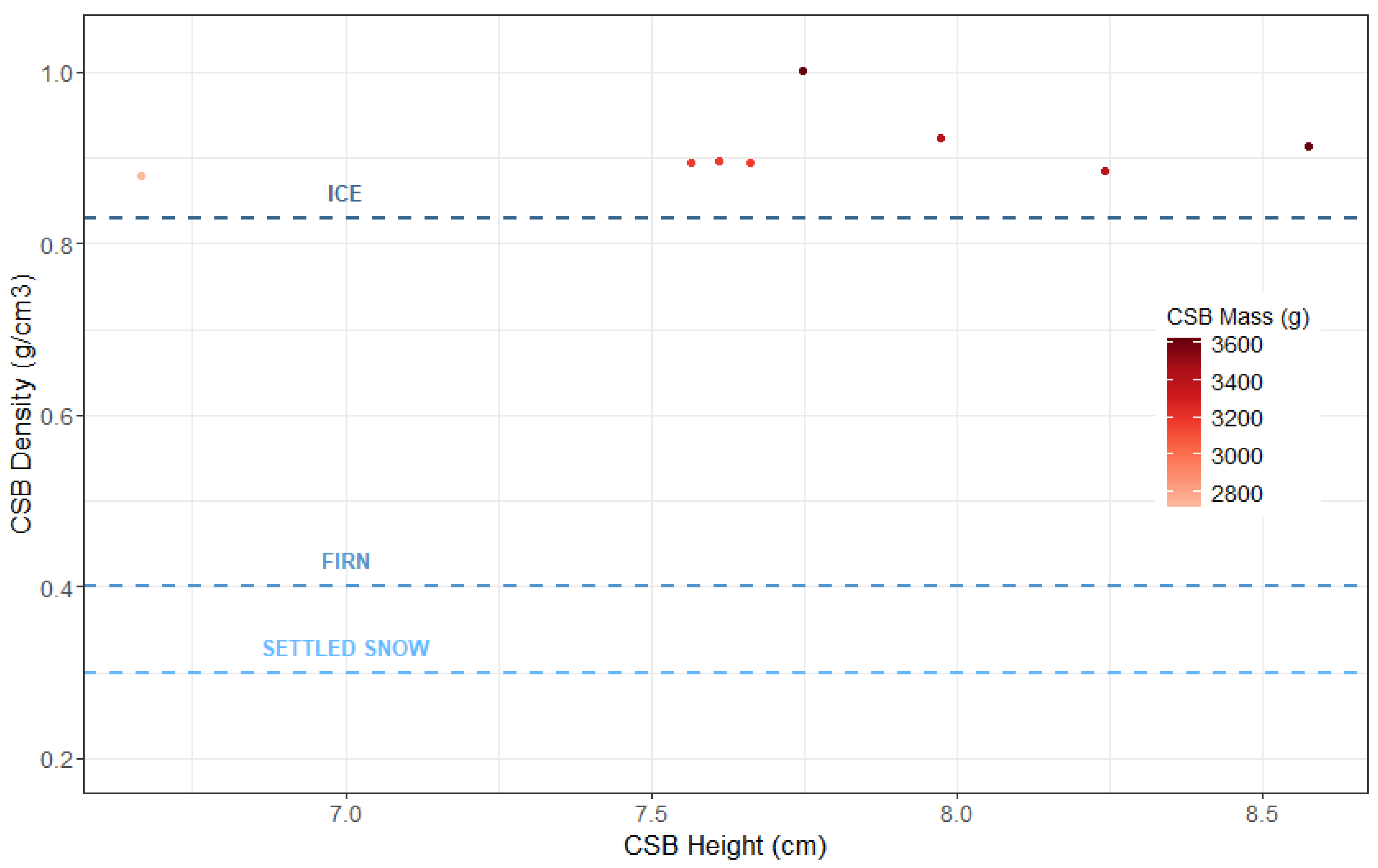

The analysis of CSB density showed that density increased in tandem with block mass, which is to be expected since the block height (and therefore, block volume) remained relatively consistent (

Figure 5). All eight of the measured CSBs had a density consistent with ice (i.e., density greater than or equal to 0.83 g/cm

3) [11]. This indicates that applying the maximum available pressure of the machine (i.e., 20,684 kPa) may not be necessary to achieve a reasonably strong CSBs depending on the intended use. For example, Russell-Head et al. (1984) demonstrated that a compacted snow runway test section with a density of 0.60 g/cm

3 was sufficient to support the load of a C-130 aircraft [12] (pp. 231-247). Haehnel et al. (2019) also demonstrated successful C-17 aircraft operations after constructing the Phoenix Runway in Antarctica that had an average density of about 0.75 g/cm

3 at a depth of approximately 150–500 mm [3]. Alternatively, snow manually compacted into gabions at an average density of approximately 0.58 g/cm

3 was successfully able to stop a range of ammunition showing its potential for ballistic protection in cold regions [2]. While snow density can provide a rough idea of potential snow strength, it is not a direct indicator of snow strength. Denser snow may suggest a more compact structure, but strength is influenced by additional factors such as grain type, temperature history, bonding between layers, and moisture content [13]. Therefore, assumptions about snow stability or load-bearing capacity should not be based on density alone. Additional testing is required to further this potential technology for snow and cold regions applications (e.g., block strength through penetration and compression testing, use of potential additives, the impact of cure time, etc.).

Qualitatively, the proof-of-concept test revealed several areas for potential development and optimization that could improve this CEB technology for application with snow in cold regions, specifically to enhance efficiency, block consistency, and field usability. First, the hopper system could be redesigned to include an auger-fed or conveyor-driven snow intake, enabling continuous and even distribution of snow into the compression chamber, eliminating the inconsistency caused by manual shoveling. The chamber size should also be adjustable or enlarged to accommodate the formation of larger snow blocks, suitable for faster construction of snow shelters or defensive structures. Additionally, the frame and mechanical components should be winterized with cold-resistant materials and lubricants to ensure operation in subzero temperatures. During this field test, we observed a large amount of moisture dripping from the block mold down onto the mechanical components of the machine. While the current machine does have waterproof protection around the wiring directly under the mold, other components do not, and while this protects from moisture it does not protect from cold. Lastly, portability enhancements (e.g., collapsible components, large tires, trackpads) would improve deployment in rugged, snow-covered terrain (e.g., snow collection and compression equipment [14] (p. 9564)). These changes would optimize the machine for rapid, reliable snow block production in remote and harsh extreme cold military environments. Overall, the findings of this proof-of-concept study support the technical feasibility of adapting CEB equipment for snow-based construction in remote or cold environments. However, further development is needed to improve repeatability and ensure consistent block integrity under varying snow conditions, as well as potential additives aimed at either increasing block strength or decreasing the required cure time to achieve said strength [2,5].

4. Conclusions

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of putting snow in a traditional CEB machine to produce CSBs for construction and fortification applications in cold environments. The primary objective was to determine whether natural snow could be compacted into structurally sound, uniform blocks using a machine designed for compacting earth materials with stabilizers and additives. The results indicate that the CEB machine is capable of consistently producing CSBs with uniform dimensions and reliable structural integrity, even when using unmodified natural snow. The narrow range of block height, mass, and density observed across samples suggests that CSBs can be produced with the consistency required for scalable, modular construction. These findings are particularly significant for military and logistical operations in cold regions, where the need for rapid, efficient construction is crucial. CSBs could offer clear advantages over traditional snow fortification methods, such as enhanced load-bearing capacity, faster assembly times, and reduced labor requirements. The ability to produce uniform, durable blocks on-site would streamline the construction of temporary infrastructure, such as protective berms, shelters, and storage units, all critical to military operations in remote or hostile Arctic environments. While this study provides promising results, several factors need further investigation, such as the effect of varying snow types and environmental conditions on block quality, as well as the scalability of the process. Future research should also explore the practical challenges and opportunities associated with using CSBs in large-scale military fortifications and rapid-response infrastructure development. The successful production of compressed snow blocks opens exciting possibilities for military logistics in cold regions, providing a potentially game-changing method for constructing durable, transportable snow structures. Further exploration of this technique could enhance the speed, efficiency, and reliability of construction operations in challenging environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D. and T.M.; methodology, K.D. and C.C.; software, N/A; validation, K.D. and C.C.; formal analysis, K.D.; investigation, K.D. and C.C.; resources, K.D., T.M., and C.C.; data curation, N/A; writing—original draft preparation, K.D.; writing—review and editing, K.D., T.M., and C.C.; visualization, K.D.; supervision, T.M.; project administration, K.D. and T.M.; funding acquisition, T.M.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article: The tests described, and the resulting data presented in this paper, unless otherwise noted, were obtained from research funded by the U.S. Air Force Civil Engineering Center and performed by the U.S. Army ERDC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to continued research on this topic that is currently in progress. Upon request, the data as well as all code for processing, analysis, and visualization will be made available via a GitHub repository:

https://github.com/kld93/SnowFort.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to GSL for lending the AECT Impact 2001A CEB machine for use in this study, and for providing their valuable insight and knowledge of methods and troubleshooting when using the machine in field testing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AECT |

Advanced Earthen Construction Technologies |

| CEB |

Compressed Earth Block |

| CRREL |

Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory |

| CSB |

Compressed Snow Block |

| ERDC |

Engineer Research and Development Center |

| GSL |

Geotechnical and Structures Laboratory |

References

- Sun, J., Zhang, Q., Zhang, G., and Fan, F. Building with Snow: Technical Exploration and Practice of Snow Materials and Snow Architecture.” Buildings 2025, 15(8). [CrossRef]

- Blaisdell, G.L., Melendy, T.D., & Blaisdell, M.N. Ballistic protection using snow. Int J of Impact Engineering 2021, 155. [CrossRef]

- Haehnel, R.B., Blaisdell, G.L., Melendy, T.D., Shoop, S., & Courville, Z. A Snow Runway for Supporting Wheeled Aircraft. US Army ERDC-CRREL 2019, Technical Report TR-19-4. www.erdc.usace.army.mil.

- Wang, E., Fu, X., Han, H., Liu, X., Xiao, Y., and Leng, Y. Study on the Mechanical Properties of Compacted Snow Under Uniaxial Compression and Analysis of Influencing Factors. Cold Regions Science and Technology 2021, 182, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Asenath-Smith, E., Melendy, T.D., Menke, A.M., Bernier, A.P., and Blaisdell, G.L. Evaluation of Airfield Damage Repair Methods for Extreme Cold Temperatures. US Army ERDC-CRREL 2019, Technical Report TR-19-2. [CrossRef]

- Carruth, W. D., Melendy, T.D., Blaisdell, G.L., Watts, B.E., Kennedy, D.E., Tingle, J.S., and Bianchini, A. Extreme Cold Weather Airfield Damage Repair Testing at Goose Bay Air Base, Canada. US Army ERDC-CRREL 2024, Technical Report TR-24-3. [CrossRef]

- Zami, M. S., and Lee, A. Economic Benefits of Contemporary Earth Construction in Low-Cost Urban Housing—State of the Art Review. J of Building Appraisal 2010, 5: 259–271. [CrossRef]

- Aranda-Jiménez, Y., Zuñiga-Leal, C., Moreno-Chimely, L., and Robles-Aranda, M. E. Compressed Earth Blocks (CEB) Compression Testing Under Two Earth Standards. Cogent Engineering 2023, 10 (1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, J. F., Rushing, T.S., and Rusche, C.P. A Comparison of Automated and Semi-Automated Compressed Earth Block Presses Using Natural and Stabilized Soils. Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Autonomous and Robotic Construction of Infrastructure 2015, 47–55.

- White, G.; McCallum, A. Review of ice and snow runway pavements. Int J of Pavement Research and Technology 2017, 11(3), 311–320. [CrossRef]

- Cuffey, K.M., and Paterson, W.S.B. The Physics of Glaciers 2006, 4th edition. Academic Press. https://shop.elsevier.com/books/the-physics-of-glaciers/cuffey/978-0-12-369461-4.

- Russell-Head, D.; Budd, W.; Moore, P. Compacted snow as a pavement material for runway construction. Cold Regions Science and Technology 1984, 9(3), 231–247. [CrossRef]

- Abele, G., and Frankenstein, G. Snow and Ice Properties as Related to Roads and Runways in Antarctica. US Army ERDC-CRREL 1967, Technical Report TR-176. www.erdc.usace.army.mil.

- Zhang, Y., Guo, J., Zhu, Y., Chen, S., Gao, C., Sun, R., & Wang, Y. Snow resource reutilization: Design of snow collection and compression equipment based on functional analysis method. Sustainability 2024, 16(21), 9564. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).