1. Introduction

Semiconductor based flexible micro-/nano electronic devices has modernized the living standards of peoples worldwide [

1,

2,

3]. Efforts have been made to maintain the ecological balance by conserving natural resources as well as ensuring the safety of both current and future generations. Among III-V compounds, the indium pnictides (InP, InAs, InSb), their ternary InAs

1-xSb

x(P

x) and quaternary InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys are preferred due to direct band gap alignments [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. These materials have played important roles for restructuring the landscape of conventional electronic technology. Historical milestones are achieved over the years by preparing epitaxially grown films. Novel digital products have been developed especially the light emitting diodes (LEDs), and laser diodes (LDs), etc. [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] Rapidly evolving innovations also helped reshaping/creating new business opportunities in photonic/optoelectronic industries. Several advanced modules are being integrated into low-powered and ultrahigh speed electronic circuits. These units have been employed to design portable nano-/micro- electronic devices for acquiring solutions in the growing needs of renewable energy, medical diagnostics, and optical communications.

Recently, III-V based photodetectors (PDs) are intensively employed for operations in the mid-wavelength infrared (IR) to long-wavelength IR region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Coupling optical sensors (OSs) with the PDs, and LEDs has enabled detecting absorption lines of pollutants in the environment [

11,

12]. Compared to solid-state and chemical-based sensing technology, the OSs have offered advantages of miniaturization for quick response -, and real-time detection of biogases in the extended short wavelength IR region. More recently, OSs are integrated in electronics for medical diagnostics (i.e., detecting biological molecules or pathogens in human body), drug analysis, ecological monitoring, and optical communications, etc. Such crucial developments have sparked research interests among scientists and engineers to design efficient electronic devices with low power consumption and high emission intensity [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Depending upon the composition x, the InAs

1-x(P

x)Sb

x ternary alloys exhibit energy bandgap

between 0.1 eV–1.34 eV. Significant lattice mismatch in the binary materials [

13,

14,

15,

16] leads to strain and intrinsic defects during the epitaxial growth of alloyed epilayers. Despite these constraints, ultrathin InAs

1-x(P

x)Sb

x films are widely used as active medium in optoelectronic devices. Quaternary InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys are employed as cladding layers for achieving high performance cascade lasers, PDs, and OSs. Due to bandgap tunability, the InAs

1-xSb

x/InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y multi-quantum-wells (MQWs) are favored to engineer 3 μm to 12 μm IR detectors. For unipolar carrier transport, the electrons and holes in MQWs can be well separated [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. This reduces electron-hole (e-h) generation-recombination current and enable device operations at higher temperature, T. The exploitation of InAs

1-x(P

x)Sb

x in active region without requiring aluminum has also helped simplifying the structural designs for fabricating photonic devices.

Irrespective of many positive features, the epitaxial growth of Sb-based materials has been and still is a challenge. Major issues to engineer device structures using InAs(P)Sb are linked to (

a) the low vapor pressure of Sb, (

b) limitations of kinetically controlled growth regime, (

c) inexistence of chemically stable hydrides as precursors, and (

d) lack of insulating substrates [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Despite these problems, attempts are made for creating alloys and heterostructures by using liquid phase epitaxy (LPE) [

34], organo-metallic vapor phase epitaxy (OMVPE) [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], and molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) techniques [

41,

42]. Recently improved growth efforts along with superior Sb-based materials, have motivated both engineers and scientists to design bipolar junction transistors (BJTs), LDs, PDs, and OSs. Earlier reports [

20,

21,

22] in InAs/GaSb type-2 SLs (T2SL) have advocated limited value of minority carrier lifetime due to the presence of Ga-related native defects. Now InAs/InAs

1-xSb

x based T2SL, with longer minority carrier lifetime, has been projected as an alternative system to InAs/GaSb for IR detection. Simple interface of InAs/InAs

1-xSb

x helps preparing it easily. Moreover, strain-engineered InAs/InAsSb LEDs have demonstrated room temperature (RT) electroluminescence between 2.7 μm - 3.3 μm.

Intrinsic carrier recombination in MQWs is a crucial process. Determined by radiative and Auger recombination, the carrier lifetime in InAs

1-xSb

x/InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y is influenced by alloy compositions x, y and strain. Compressive strain can reduce the Auger recombination and increases the radiative recombination rate. This behavior is not universal, it rather depends upon the choice of specific materials and structures. Nonradiative recombination is also a major channel. Possibilities involving Auger recombination exist, where the electron (e) and hole (h) pairs unite by transferring energy and momentum to another carrier rather than emitting photons. In this process, the probability of nonradiative Auger recombination increases exponentially as

decreases. This reduces the efficiency of optoelectronic devices like solar cells and LEDs. Despite these issues, many efforts are made for the growth of InAs

1-xSb

x/InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y MQWs to design electronic devices for photonic applications [

20,

21,

22]. The material systems with sharp and clean interfaces have advantages of normal incidence, with a broadband absorption.

Despite the successful growth of InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y/n-InAs or GaAs epilayers, very few attempts are made to study their structural and phonon characteristics. While the structural traits of these materials are influenced by alloy compositions x, y and lattice mismatch, their vibrational properties can have significant impact on the device performance through phonon scattering and thermal transport. For exploring these attributes, a variety of experimental techniques can be adopted. Methods that are frequently employed include Raman scattering spectroscopy (RSS), Fourier transformed infrared (FTIR) reflectivity [

43,

44,

45], high resolution x-ray diffraction (HR-XRD) [

41], transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [

41], extended x-ray absorption fine structures (EXAFs) [

46,

47,

48,

49], electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) [

41], photoluminescence (PL) [

41], spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE) [

50,

51], and electron energy loss (EEL) measurements [

41] etc. For InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y epilayers, limited efforts are made using EXAFS, Raman scattering and FTIR spectroscopy for systematically assessing their structural and vibrational behavior. Meticulous evaluation of these properties is important to optimize device structures for achieving high-performance waveguide modulators, injection lasers, PDs, LDs, and LEDs [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

This paper reports the results of our methodical studies (cf. Sec. 2, 2.1–2.4) by carefully analyzing the experimental data for assessing the structural and phonon characteristics of InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y epilayers. Except for the S4-S9 samples which are prepared on GaAs substrate, most other epilayers are grown on n-InAs by using gas source MBE (GS-MBE). TEM was used earlier to investigate the structural and chemical distributions of atoms [

41]. For InAs

1-x(P

1-x)Sb

x alloys the evaluation of Sb composition, x was achieved by performing electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) [

41]. Hall studies with van der Pauw methods were conducted at RT on Be- and Si-doped InAs

1-x(P

1-x)Sb

x/GaAs epilayers [

41] to appraise their electrical properties. While the optical characteristics were reported by PL measurements [

41] limited studies exist, however, on the phonon characteristics using FTIR and Raman scattering spectroscopy [

43]. For Raman (cf.

Section 3) studies, we have used a Renishaw In Via spectrometer equipped with a 576 × 400-pixel Peltier cooled (−70 ◦C) CCD detector. Besides RSS (cf.

Section 4.3), the phonon characteristics are also examined by reflectivity measurements using a Bruker IFS 120 v/S Fourier transformed infrared spectrometer. Numerical simulations of the reflectivity spectra are achieved by adopting a standard methodology of multilayer optics (cf.

Section 4.4) within the transfer-matrix-method (TMM) [

52]. The structural traits of InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y epilayers are carefully assessed using the polarization dependent (cf.

Section 4.5) synchrotron radiation SR-EXAFS measurements [

46,

47,

48,

49]. We have focused our attention on the EXAFS oscillations well above the P K-edge and In K-edge for selectively studying the P- and In-centered local surroundings in InAsPSb. Systematic simulations are performed to comprehend the SR-EXAFS data for attaining average coordination number, and the nearest neighbor In-Sb, In-P, and In-As bond lengths (cf.

Section 4.5), etc. Meticulous studies are performed by exploiting IFEFFIT software package consisting of ATOMS, ATHENA, AUTOBK, ARTEMIS programs along with residual space mappings (RSMs) using a valence force field (VFF) model [

41] for attaining the distortion energies in InAsPSb alloys. Results of structural and phonon properties on GS-MBE grown InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y samples are compared/contrasted (cf.

Section 4) against the available experimental and theoretical data with concluding remarks presented in

Section 5.

4. Results and Discussions

Quaternary III-V alloy semiconductors InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y are commonly used as detectors and emitters in the MWIR optoelectronics [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Basic traits of these alloys include tunable bandgaps

and lattice constant

a which depend on their specific compositions, x, y. These fundamental features are required to design electronic devices for various applications. InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y involves three binary InP, InAs and InSb compounds of zb crystal structures. Growth of high-quality quaternary alloys can be difficult due to potential challenges of mismatch with substrates, compositional non-uniformity, and optimizing growth kinetics [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Lattice constant of quaternary InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloy can be adjusted by varying x, y. Techniques like step-graded or metamorphic buffer layers are also suggested to overcome the issues of lattice mismatch [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. These developments have allowed flexibility in device design by preparing high-quality epilayers on lattice-matched InAs and/or GaAs substrates [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Such epilayers have been employed in strain-engineered heterostructures. Tensile-strained barriers are used compensating the high compressive strain in InAs

1-xSb

x/InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y QWs. Larger bandgap InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y barrier relative to active InAs

1-xSb

x layer is known for enhancing the carrier confinement. This choice of QW in LEDs has also led [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33] to higher carrier extraction efficiency with improved quantum efficiency, and reduced efficiency droop.

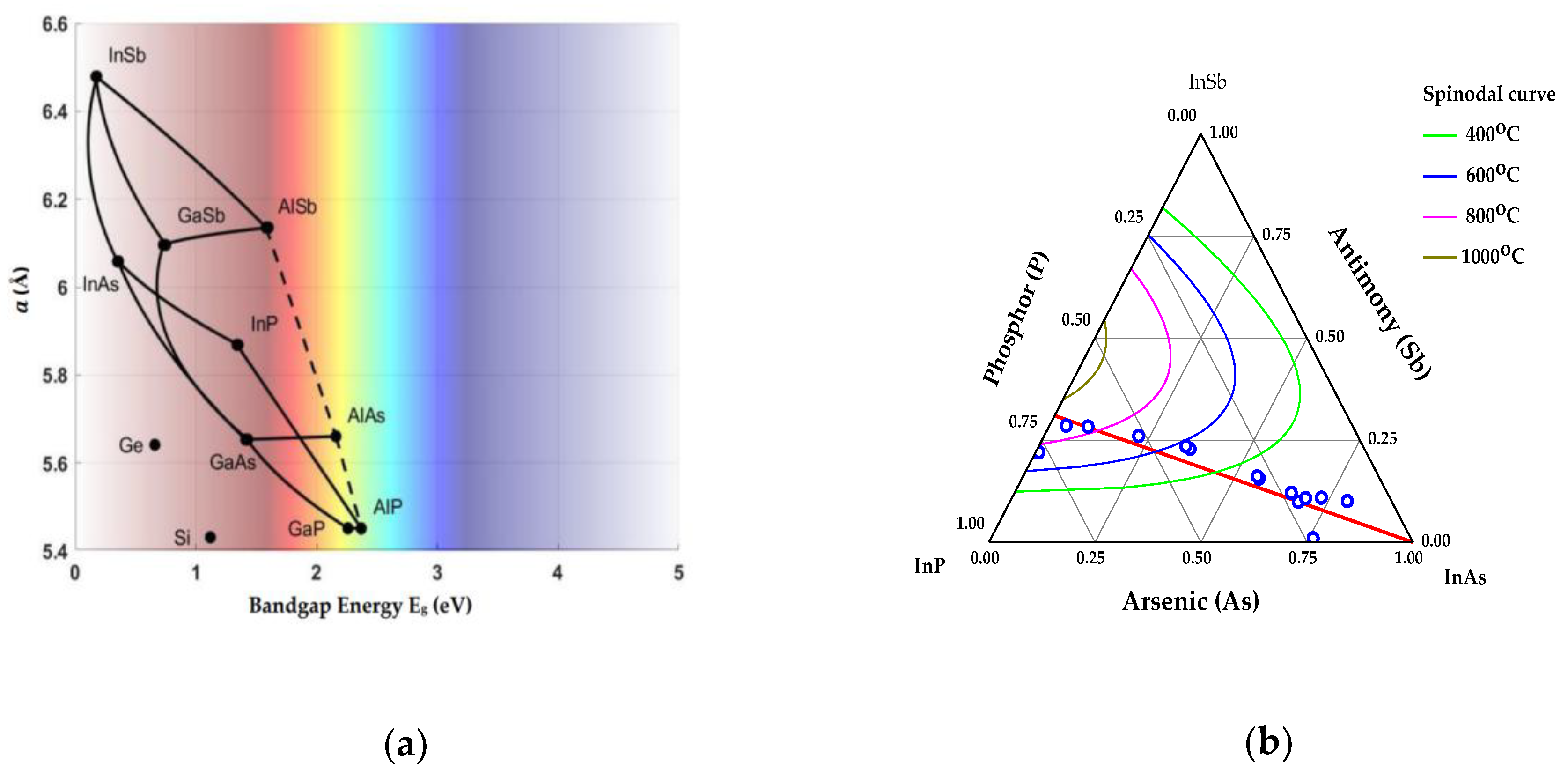

4.1. Crystalline and Structural Properties

In

Figure 1a) we have displayed the lattice constant

a (Å) versus electron energy bandgap

of several III-V compound semiconductors.

Figure 1b) shows the calculated composition planes along with spinodal curves for different growth temperatures in the quaternary InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys.

Open blue colored circles in

Figure 1 b) represent the composition, determined by EPMA [

41] for several GS-MBE grown samples (see

Table 1). Composition plane, along with spinodal curves are calculated using delta lattice parameter (DLP) model [

61]. Results are displayed for the growth temperatures of 400

oC, 600

oC, 800

oC and 1000

oC using green, blue, violet and black color lines, respectively. Calculations of spinodal curves assume thermodynamic equilibrium conditions. However, GS-MBE approach is generally thought to be far from the thermodynamic equilibrium. Thus, epitaxial growth kinetics has played important role in determining the materials’ structural characteristics. Several researchers have pointed out that as the depositing layer is slightly mismatched to the substrate, the effect of resulting coherent strain may decrease the critical, T of the spinodal point [

41]. This allows meta-stable growth in the immiscibility region as shown in

Figure 1 b). One may note that the six samples with low composition of arsenic are grown inside the immiscibility region. The lattice constant of InAs is 6.0583 Å, and the calculated lattice mismatch of the grown layers is found to be less than 0.4%, with only those samples within the immiscibility region having a lattice constant smaller than that of the InAs.

4.2. Comparative Lattice Dynamics of Indium Pnictides

Lattice dynamics of indium pnictides has been extensively studied by using experimental (e., IR and, Raman scattering spectroscopy) and theoretical methods [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. Inelastic neutron scattering (INS) spectroscopy [

54,

55,

56] is one of the most accurate techniques for measuring phonon dispersions

of different materials including semiconductors. Experimental data on lattice dynamics has encouraged researchers to develop theoretical methods by exploiting both the first principles and phenomenological models. Ab initio studies are used for determining the atomic-scale vibrational properties of materials from their basic physical traits without including experimental data or empirical parameters. Such calculations have employed density functional theory (DFT) to solve the Schrödinger equation for accomplishing accurate descriptions of

, and thermodynamic properties [

57,

58]. For InP, InAs and InSb, many ab initio calculations have employed commercial packages of ABINIT software and Quantum-Espresso programs for predicting their phonon and electronic characteristics [

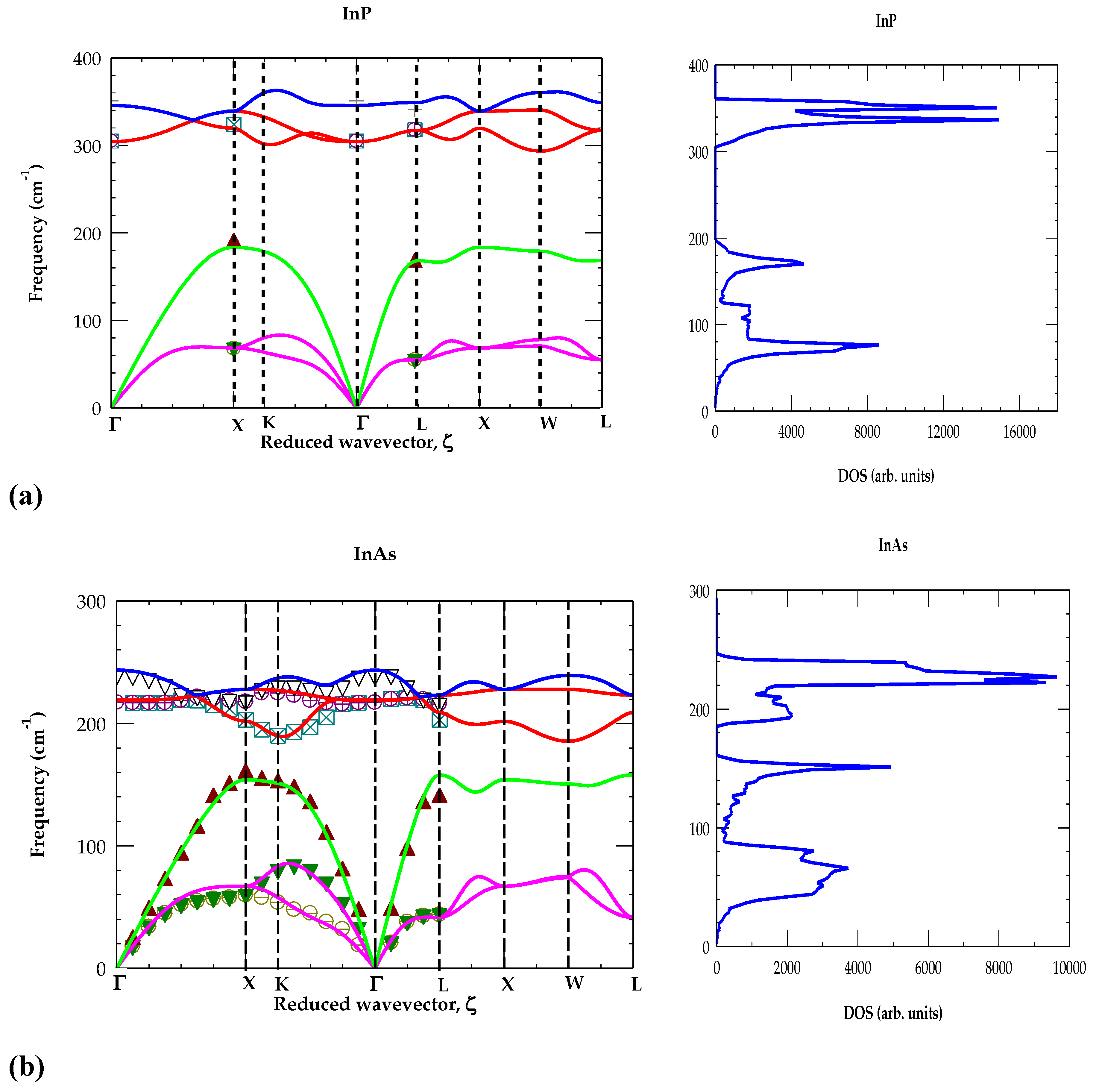

58]. Here, we have used a realistic rigid-ion-model (RIM) [

57] and reported our calculations of

(see

Figure 2 ac)) for indium pnictides. Theoretical results are compared/contrasted reasonably well with the existing INS, RSS [

53,

54,

55,

56] data, and ab initio simulations [

58].

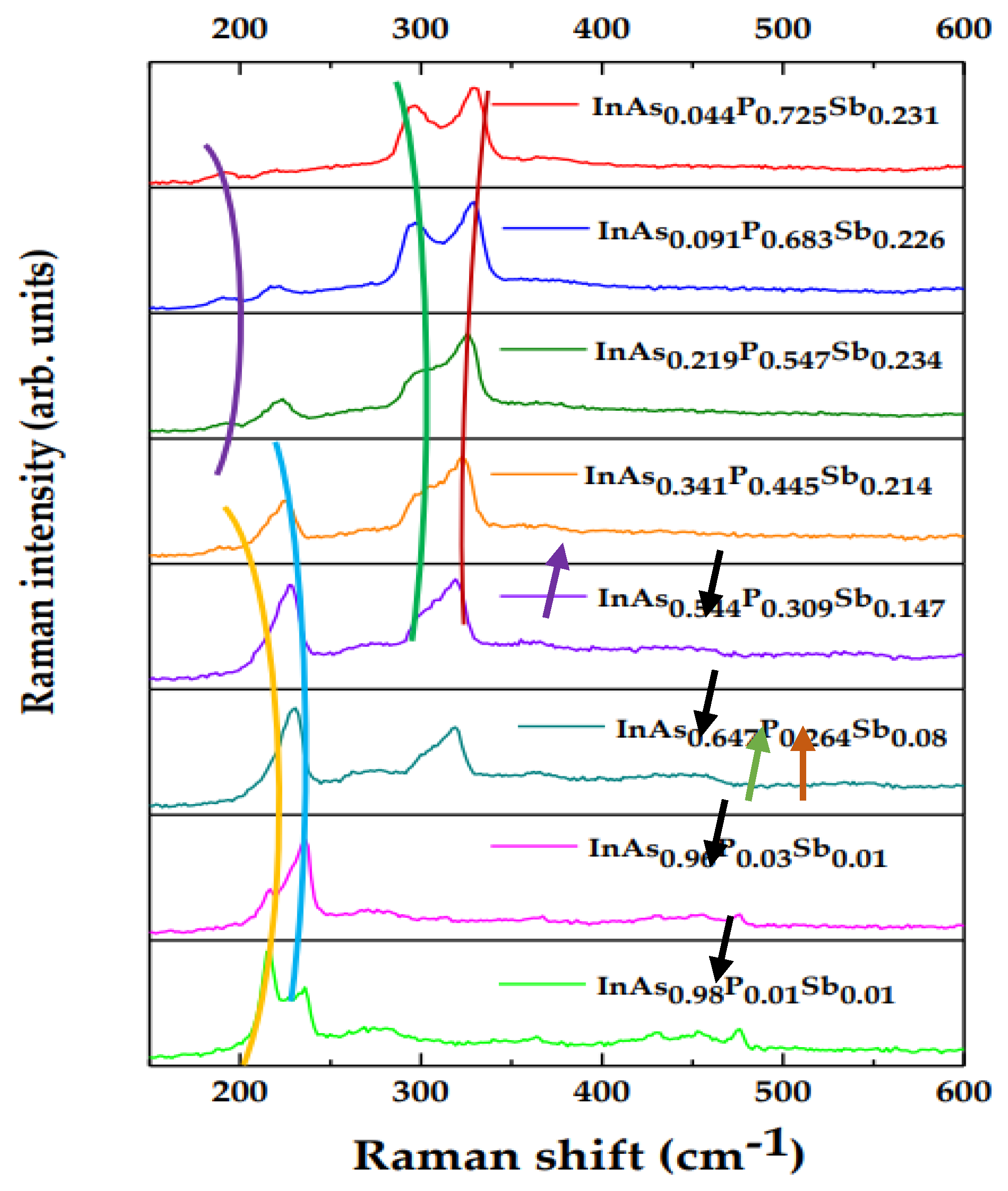

Perusal of

Figure 2 ac) show identical features of phonon dispersions for InP, InAs, and InSb materials because of their common zb structures. Results also revealed significant differences due to the variation of group-V anion P, As, Sb masses. Increasing mass ratio of the two atoms have demonstrated several key trends across the InP→ InAs → InSb series: (i) InP has the highest phonon frequencies of longitudinal optical LO (

) and transverse optical TO (

) modes with wider separation between its acoustic and optical branches, (ii) in InAs the

phonon mode frequencies are lower than InP due to heavier As atom, and (iii) InSb showed the lowest

phonon values than InP and InAs due to the involvement of heaviest mass of Sb.

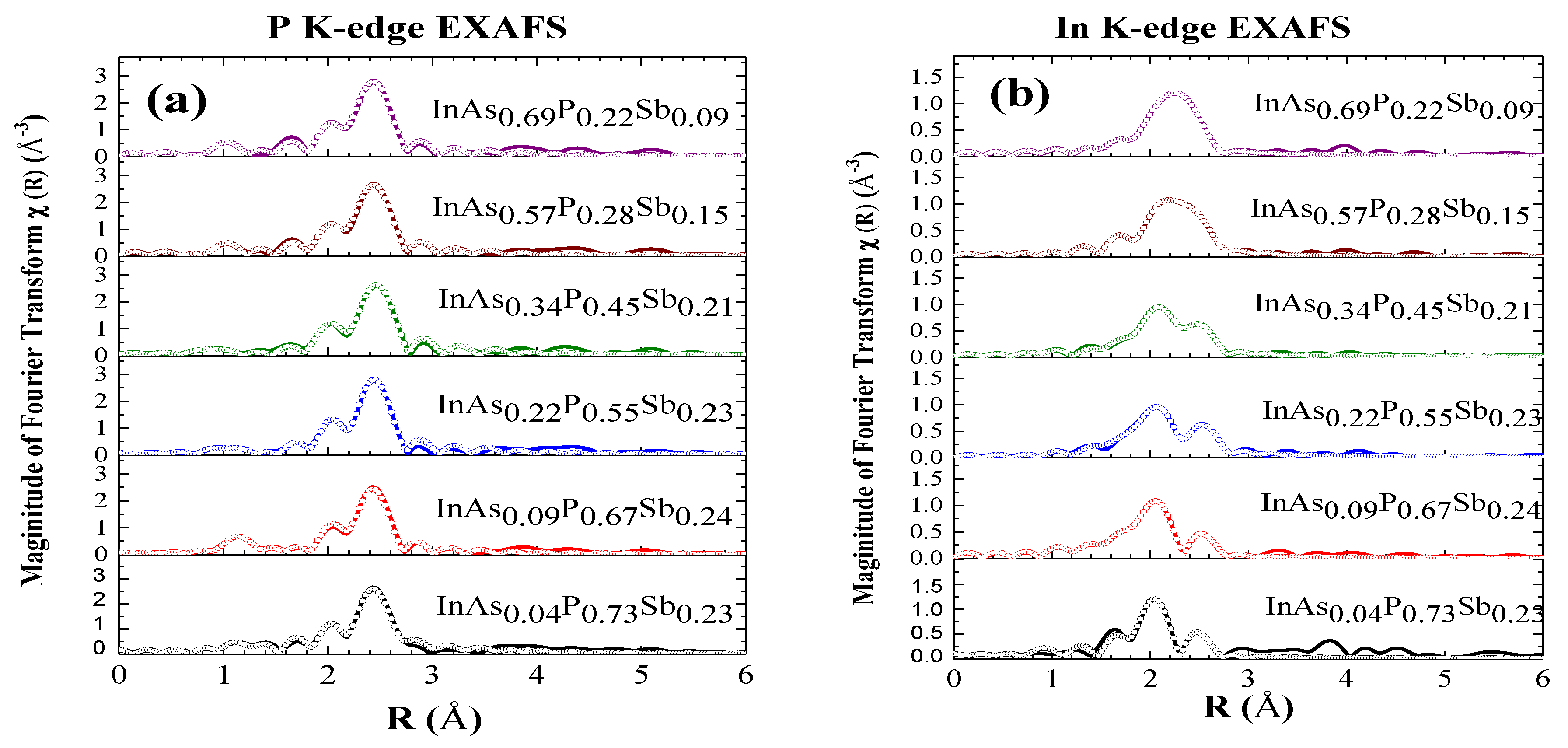

4.3. Composition Dependent Raman Scattering Spectra

Raman scattering is a powerful and non-destructive method. It has been frequently used for exploring the vibrational features of both simple and complex ionic materials [

43,

44,

45]. In the ternary and/or quaternary alloys, the RSS is employed for characterizing the composition dependent phonon modes. In epitaxially grown heterostructures, the analysis of Raman scattering data has helped assessing the crucial information on their structural, interfacial, strain, electronic transitions, confinement of acoustic phonons, as well as the photoexcited e-h plasmas for creating coupled-plasmon LO modes, [

43,

44,

45], etc.

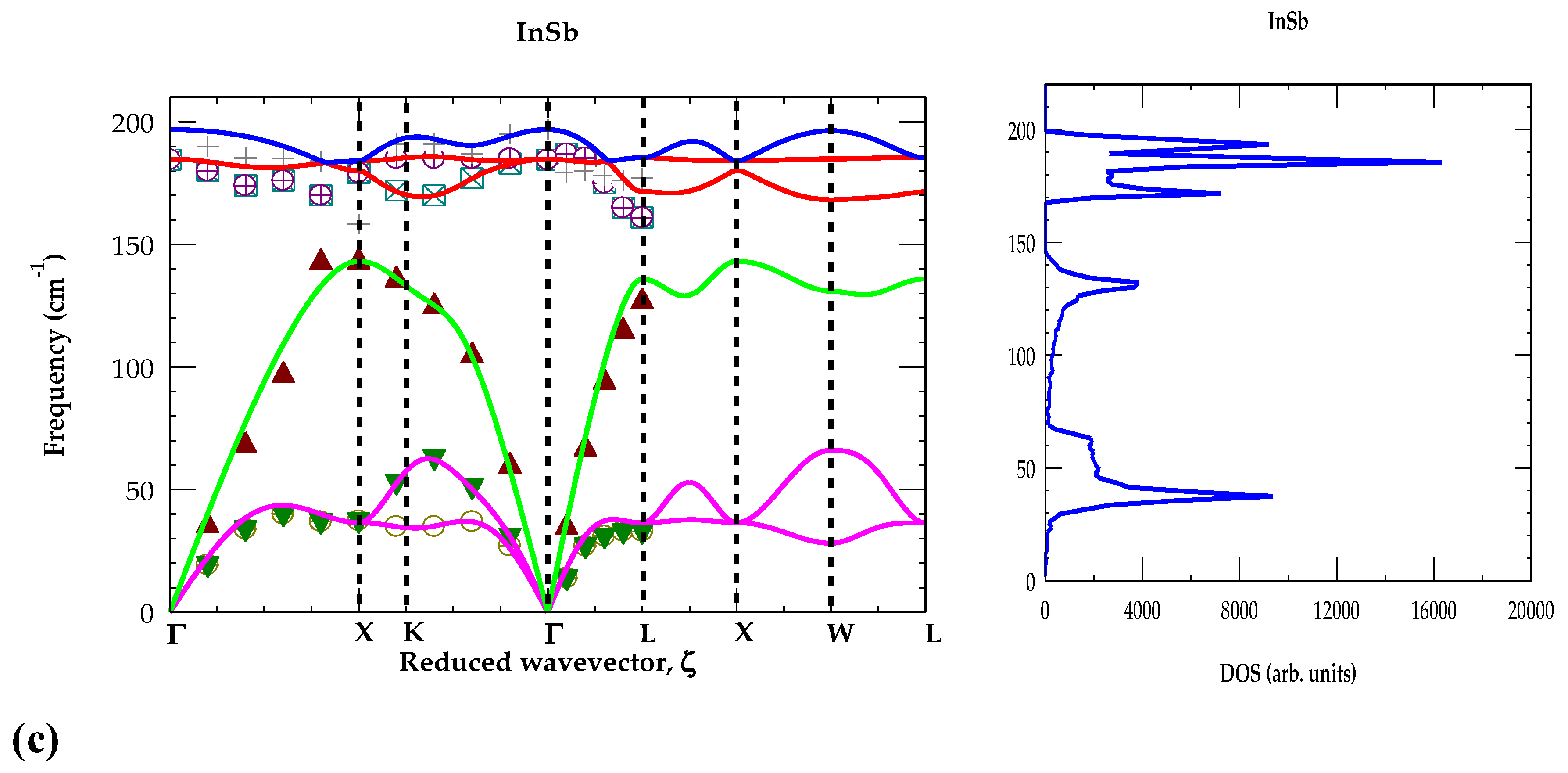

In

Figure 3, we have displayed our RT results of the Raman scattering studies performed on eight different GS-MBE grown samples in the backscattering geometry. In this configuration, one would expect observing only the

modes as the

phonons are forbidden. The observation of both

modes in InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys are possibly caused by disorder. Results on different InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y/n-InAs samples with increasing values of As have provided useful information on: (

a) the specific compositions of constituent materials, (

b) disorder induced modes, and (

c) lattice mismatch-induced strain between epilayers and substrates. In

Figure 3, the vibrational features with shifts of Raman peaks of InP-, InAs-, and InSb-like modes are markedly visible. In InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y/n-InAs the observed phonon modes along with the presence of additional disorder-related broad bands are used for monitoring their overall crystalline quality, strain, and composition.

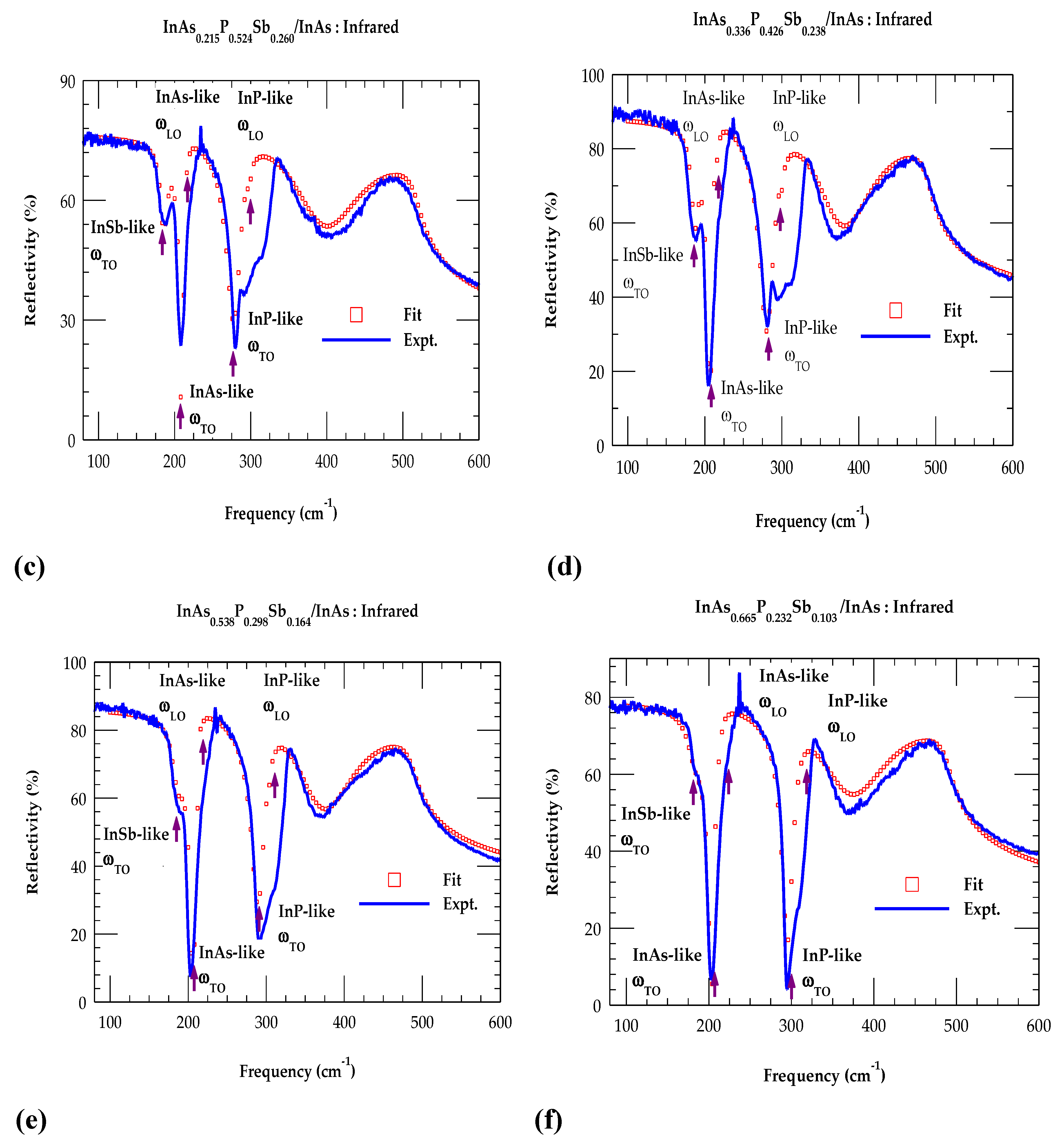

Raman scattering results in InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y/n-InAs epilayers (see

Figure 3) have revealed InAs-like

and

modes

(~218 cm

-1) and

(~238 cm

-1)] when the As composition is increased between 0.219 to 0.98. As a guide to the eye, the InAs-type phonons are shown by using the orange and sky-blue curved lines. In samples with P composition between 0.264 to 0.725, the observed InP-like

(~307 cm

-1) and

(~345 cm

-1) modes are indicated by green and brown color arrows or curved lines. In InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y/n-InAs epilayers with Sb composition between 0.214 to 0.234, our Raman scattering measurements have identified a prominent InSb-like

(~182 cm

-1) phonon peak shown by a violet arrow or curved line. A broad phonon feature shown by black colored arrows near (~275 cm

-1) that appeared between InAs- and InP- like modes is assigned as a disorder-activated optical phonon band within the immiscibility region [

41] or as a InAs:P local vibrational mode. The ability of examining strain and disorder in GS-MBE grown samples can be valuable for evaluating the performance of photonic devices when they are integrated in MQWs. Clearly, the Raman scattering results have confirmed the prospects of “three-phonon-mode behavior”. The assignments of InP, InAs and InSb-like optical phonons are consistent and fully supported by our FTIR reflectivity, RIM results of phonon dispersions (see

Figure 2 ac)) and other Raman scattering data (see:

Table 2).

4.4. Composition Dependent Infrared Spectra

Very few measurements are known using FTIR reflectivity spectroscopy to comprehend the vibrational characteristics in InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y quaternary alloys. In the related III-V ternary AB

1-xC

x alloys, several IR and RSS experiments have provided strong basis of identifying phonon features in terms of their binary AB, AC compounds. Following Chang and Mitra [

62], one can classify the one-phonon-mode behavior in Ga

xIn

1-xP and two-phonon-mode behavior in InAs

1-xP

x(Sb

x) ternary alloys. In the quaternary InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y compounds, however, the vibrational feature has not been firmly confirmed. Our FTIR measurements on GS-MBE grown InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y/n-InAs epilayers have revealed multiple phonon features with distinct vibrational bands. These characteristics are clearly linked to three In-P, In-As, In-Sb like bonds of the binary zb indium pnictides.

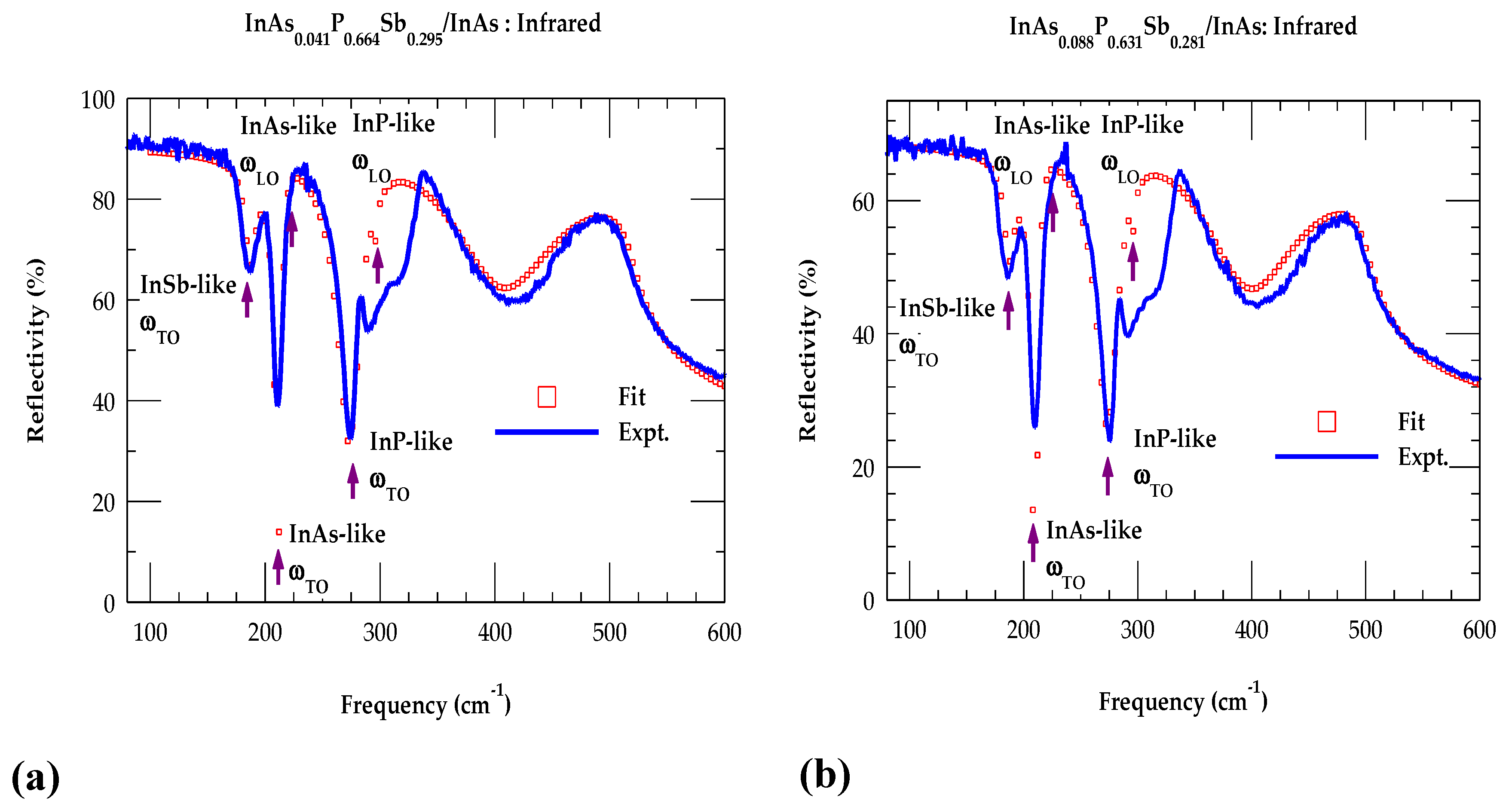

In

Figure 4 a-f) we have reported our infrared reflectivity spectra on several GS-MBE grown InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y/n-InAs samples having different alloy compositions x, y. The experimental results recorded at RT, are displayed by using full blue color lines. The FTIR spectra are contrasted against our theoretical fit achieved by using TMM [

52]. The simulated results are indicated by red color open squares. Clearly our experimental and theoretical results have confirmed the observed frequency shifts, influenced by In-P, In-As, In-Sb like phonon energies including the disorder activated modes. Consistent with the Raman scattering spectroscopy, the FTIR reflectivity results on samples with explicit alloy compositions x, y has provided a reasonably good theoretical fit. Undoubtedly, the FTIR spectra of InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys have demonstrated a “three-phonon-mode” behavior.

4.4.1. Three Phonon Mode Behavior

Distinct optical phonon peaks corresponding to In-P, In-As, and In-Sb-like lattice vibrations are observed in Raman scattering (cf.

Section 4.3) spectroscopy, as well as FTIR reflectivity measurements (cf.

Section 4.4). Analyses of these results using RIM calculations of lattice dynamics have revealed InP, InAs and InSb like phonons along with alloys’ structural disorder modes (cf.

Figure 5). Unlike III-V ternary alloys including Ga

1-xIn

xP and InAs

1-xSb

x(P

x) which displayed either one-phonon mode and two-mode behavior, respectively – in InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys our studies have exhibited “three-mode” behavior of different bond types by observing their appropriate optical phonon peaks.

Summarizing the vibrational results on epitaxially grown InAs1-x-ySbxPy/n-InAs specimens, we have noticed that Raman scattering spectroscopy and FTIR reflectivity measurements are complementary to each. Theoretical analyses of experimental data have confirmed that: (a) InP-like modes are the most stable features across a wide range of P composition, (b) InAs-like phonons appear at higher As concentration, and (c) InSb-like modes are noticed only at higher Sb composition.

4.5. Composition Dependent SR-EXAFS Spectra

SR-EXAFS spectroscopy is a powerful technique commonly used for analyzing the local atomic structure of different materials [

46,

47,

48,

49]. It is an element-specific approach usually employed for probing atomic environment around the absorbing atom. When applied to InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y/GaAs epilayers, the SR-EXAFS spectra are extremely sensitive to the alloy compositions, x, y. Careful analysis of EXAFS data for such materials can provide valuable information of their bond lengths, coordination numbers, and local disorder.

In exploring polarization dependent SR-EXAFS data, we have studied experimental oscillations well above the P K-edge and In K-edge, respectively. These results helped us selectively studying the P- and In-centered local surroundings of GS-MBE grown samples. When the core-level electron is excited by incident x-ray, the resulting photoelectron scatters off the surrounding neighboring atoms. Interference patterns of such scattered photoelectrons with outgoing wave provided oscillations in the x-ray absorption coefficient μ [

63]. For InAsPSb, the EXAFS spectra without double crystal monochromator (DCM) energy calibrations can cause systematic errors, rendering unreliable data (cf.

Section 4.5.2).

Analysis of EXAFS oscillations via the Fourier transformation, have exhibited radial distribution χ(E) functions. These functions offer estimating distances and number of neighboring atoms from the absorbing atom. One can express the energy-dependent χ(E) using x-ray absorption coefficient μ, where the single scattering mechanism dominates. The function χ(E) may be evaluated by using the following relationship: [

63]

In Equation (1), the term is the experimentally observed absorption coefficient; (E) is a smooth background function representing the x-ray absorption by an isolated atom; is the measured jump (‘edge-step’) in the absorption at the threshold energy (i.e., the binding energy of the core-level electron). In InAs1-x-ySbxPy epilayers, the x-ray absorption spectral coefficient μ as a function of E has revealed the sharp rise in intensities at the P K-edge and In K-edge, respectively. The absorption results initiated almost step-like functions with weak oscillatory wiggles observed beyond several hundred eV above the edge. The region closer to absorption edge is often dominated by the strong scattering processes including the local atomic resonances.

Since the EXAFS data is best described by the wave-like behavior of the photoelectron created in the x-ray absorption process, it has been a common practice to exploit the EXBACK program to convert the x-ray energy E to wavenumber of the photoelectron. This has helped us evaluating the χ(k) results as a function of from the raw data. Thus, we focused our attention on the region of EXAFS oscillations covering the x-ray photon energy E from nearly tens of eV above the absorption edge. The results are carefully analyzed for extracting the structural characteristics.

From the observed P K-edge and In K-edge EXAFS oscillations including the non-Gaussian disorder for the InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y materials, χ(k) is expressed in the single scattering and plane wave approximations: [

63]

where,

is the electron mean free path;

is the atomic backscattering amplitude; the angular bracket < > is the thermal average;

is the net phase shift;

is an amplitude reduction factor due to many body effect; N is the coordination number; and R is the instantaneous bond length between the backscattering and absorbing atoms. From Eq. (2), it is obvious that one requires χ(k) – the key quantity for experimental analysis of the EXAFS data. Extraction of the EXAFS modulation function χ(k) is achieved from the raw absorption data (cf. Sec. 2.4) following the standard procedures described elsewhere [

63].

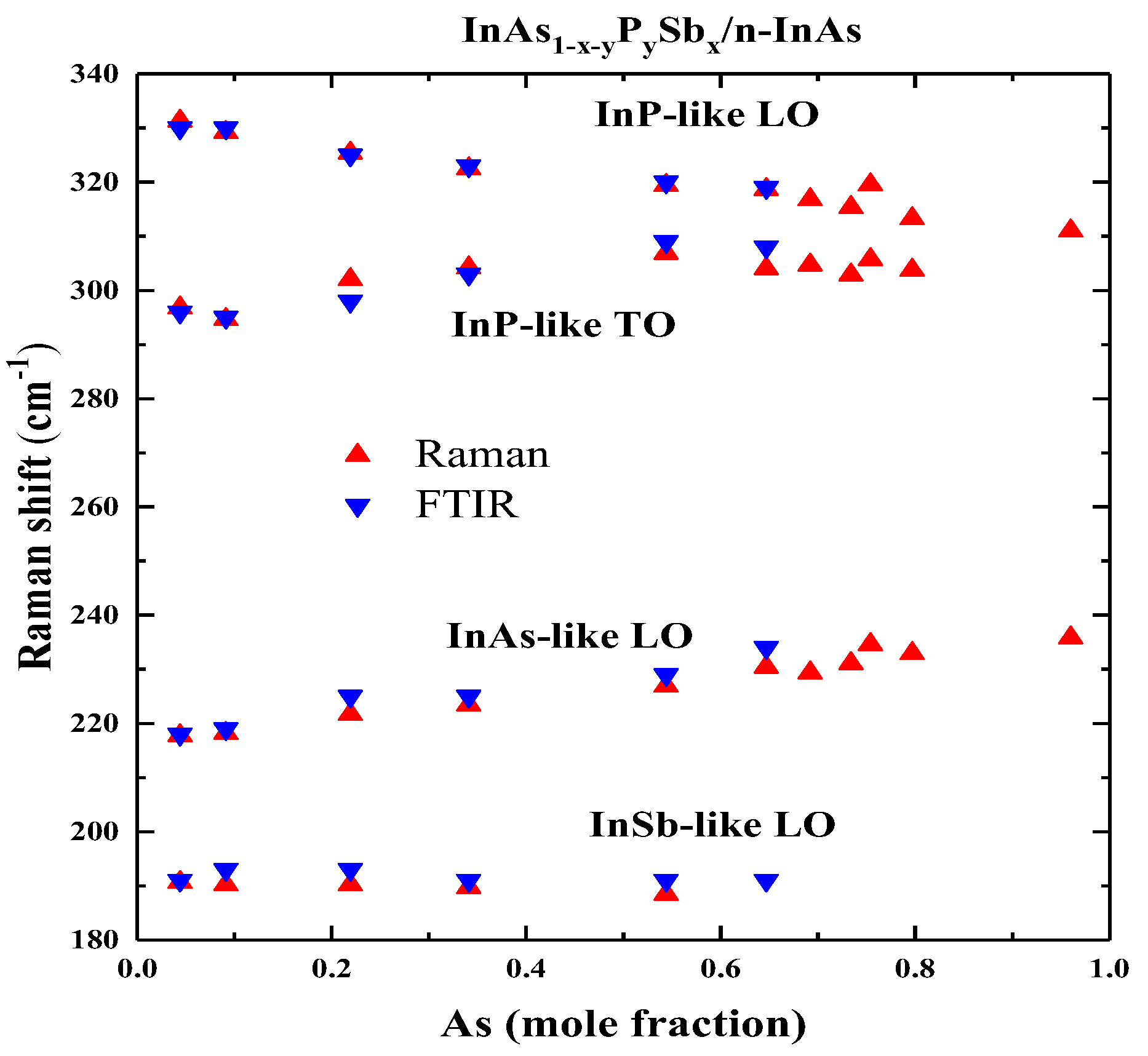

In

Figure 6 ab) we have reported the results of Fourier transformed EXAFS spectra χ(R) versus R between 0 to 6 Å in the P K-edge and In K-edge, respectively for the GS-MBE grown samples of different compositions x, y.

To fit the experimental EXAFS data of χ(R) (cf.

Figure 6 ab)), we have adopted appropriate programs from the IFEFFIT package. These programs consist of ATOMS, ATHENA, AUTOBK, ARTEMIS that helped us converting the oscillating features of absorption coefficients to the Fourier transform spectra. The AUTOBK program [

63] was exploited for removing the background contributions from the k-space signals. The perusal of

Figure 6 a) in the P K-edge spectra for InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y samples has clearly revealed In-P bond lengths exhibiting nearly identical values, despite the changes in P compositions. These values of In-P bond lengths are closer to the bond length of bulk InP binary material [

48]. For larger P compositions three distinct peaks at R ~2.1 Å, R ~3.9 Å, and R ~ 4.6 Å are linked representing to the scattering from first (P), second (In), and third (P) nearest neighbors (NNs), respectively [

48]. Technically, the In K-edge EXAFS spectra are expected for providing the signals from In-P, In-Sb, and In-As bonds. From

Figure 6 b), one can notice that for InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y samples with low As compositions, separate peaks representing to In-P [

48] and In-Sb ~ 2.79 Å [

49] bonds are evident. By increasing As composition, the peaks are spotted gradually merging into the In-As ~ 2.60 Å signal [

46].

4.5.1. Valence Force Field Model Analysis of SR-EXAFS Spectra

To further explicate the EXAFS spectra, accurate numerical simulations are necessary. In InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys, theoretical methods must account for the four atomic species forming In-P, In-As and In-Sb bonds, as well as compositions and carefully varying the bond lengths and bond angles. Here, we have adopted a VFF model to calculate the bond lengths which includes both the bond-stretching and bond-bending terms. Calculations are performed for the atomic positions in the InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys of the In-centered configurations. Here, we have carefully selected the group III atom and used random numbers to consider the position of each group V atom in the supercell. The numbers of P, As and Sb atoms were chosen according to their mole fractions determined from EPMA. To fit the EXAFS signals we have meticulously adopted the ARTEMIS codes [

63]. Choice of these arrangements are linked to the values of the bond-lengths close to In-P estimated in the EXAFS spectra.

Atomic positions in InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys are carefully estimated by minimizing the total energy. Once the atomic positions with minimized energies are achieved by using a VFF– the output can be carefully exploited for simulating the reciprocal space maps of the quaternary alloys [

59,

60]. Modeling of RSMs is a sophisticated approach for predicting the atomic structure by linking it to the observed HR-XRD patterns in the quaternary alloys. We have used RSMs to inspect the lattice relaxation of InAsPSb grown on GaAs substrates to extract vertical

az and horizontal

axy lattice constants (see:

Table 3). For details of this approach, we refer to one of our earlier papers [

41] epilayers. The ratio

az/

axy describes the deformation of the crystal unit cell relative to its relaxed, unstrained state.

4.5.2. Calibrated SR-EXAFS Spectra

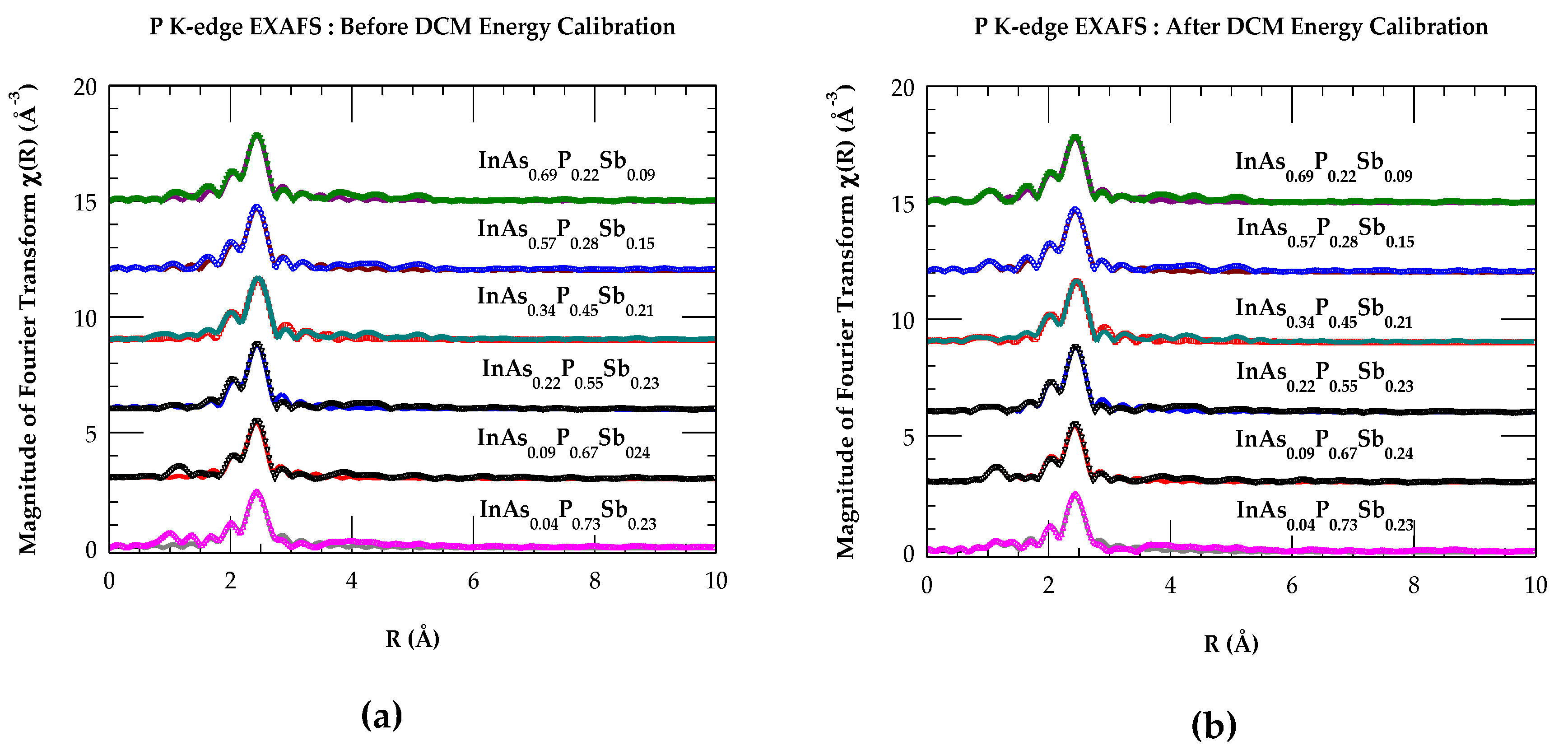

For complex alloy systems, the measurement of EXAFS spectra without DCM energy calibrations can introduce systematic errors, rendering the resulting data unreliable for quantitative analysis. The DCM energy calibration is an essential step to ensure that the detected absorption features correspond to the correct X-ray energies, which is critical for the structural analysis of InAsPSb alloys. Hence, the EXAFS data for materials must have their energy calibrations done before performing the quantitative fits. This is a critical prerequisite for accurate analysis, not an optional post-step. In

Figure 7 ab) we have reported our P K-edge EXAFS spectral results on the GS-MBE InAsPSb samples before and after the DCM energy calibration.

Careful fitting procedure of EXAFS data (

Figure 7 ab) has provided structural parameters (see:

Table 4). These are linked to the definition of absorption edge energy [

63].

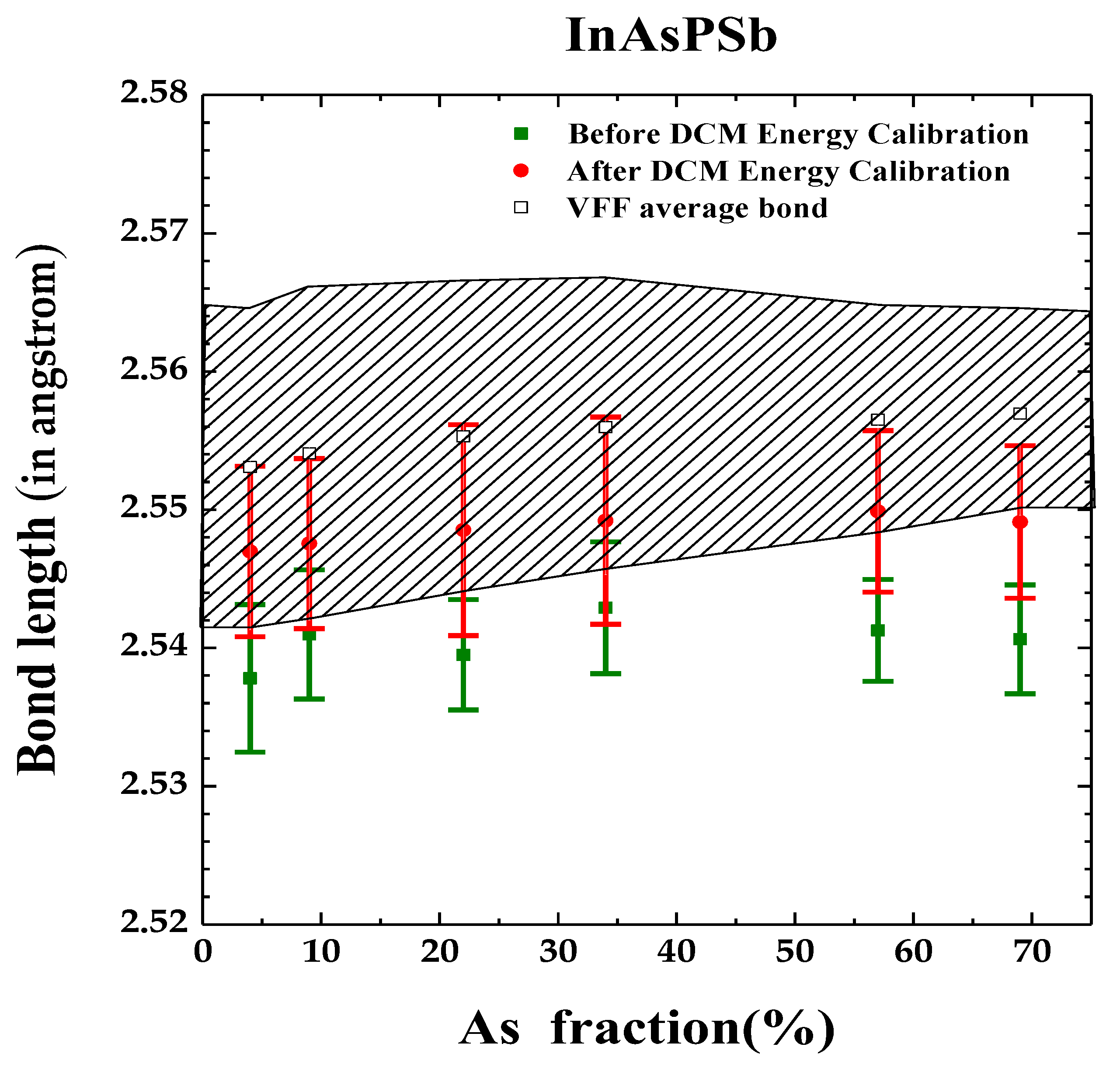

In

Table 4, we have listed the necessary EXAFS fitting parameters evaluated carefully before and after DCM energy calibrations. These parameters (cf.

Section 4.5) include the amplitude reduction factor

, relative square displacements

, coordination number N, bond length R, and ΔR, etc. For InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y/GaAs epilayers, we have compared in

Figure 8 the simulated bond length variation versus As composition. The displayed results include our meticulous analysis of the EXAFS data (

Table 4) as well as the simulations of bond lengths from the VFF model. Clearly, the perusal of

Figure 8 has indicated the alloy bond lengths which are closer to their values in the binary materials. The consistency of experimental and simulated results has also supported the validity of the two approaches.

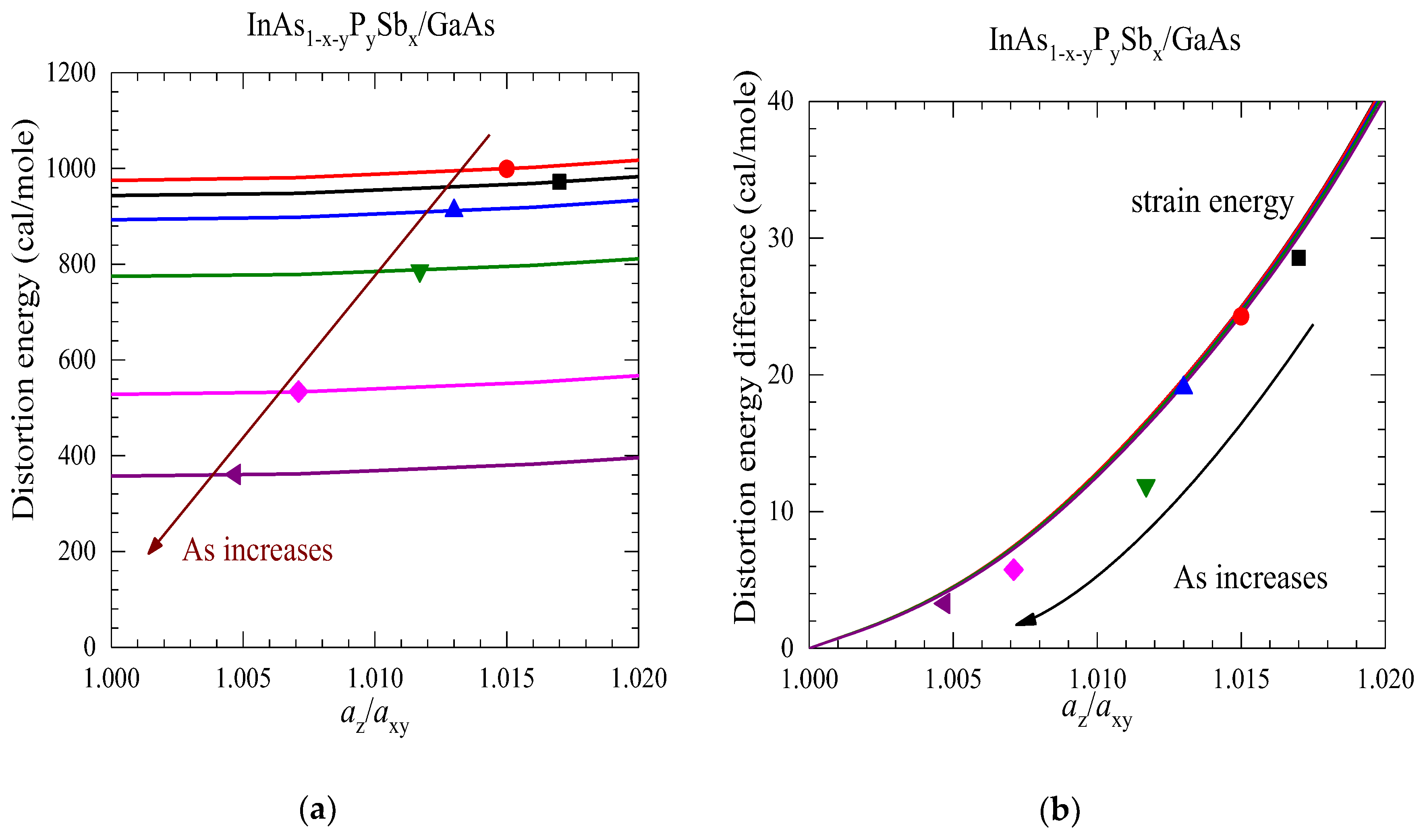

4.5.3. Internal Distortion Energy in InAs1-x-yPySbx/n-InAs Epilayers

In

Figure 9 a) we have plotted the simulated results of distortion energy as a function of

az/

axy for the GS-MBE grown InAs

1-x-yP

ySb

x/GaAs samples (

Table 4).

Figure 9 b) denotes the energy differences by using the energy at

az/

axy = 1 as a reference. In fact, we fixed the

az/

axy ratio and find the lowest distortion energy for each specified ratio for generating six curves displayed in

Figure 9(a). The strain energy curves in

Figure 9b) are calculated from the curves in

Figure 9a) by subtracting the distortion energy with

az/

axy = 1 from each distortion energy (with different

az/

axy). Again, we have noticed that the strain energy curves coincide the results calculated using the elastic constants of the alloys and their values are much lower than the distortion energies. This result clearly suggests that the internal distortion is much stronger than the stress resulting from the lattice mismatch. Obviously, it supports our earlier argument that the internal distribution hinders the lattice relaxation. Thermal mismatch between InAsPSb and InAs substrate causes a thermal strain. However, its level being < 0.1 % is certainly negligeable.

5. Concluding Remarks

Epitaxial growth of different InAsPSb, AlGaAsSb and InGaAsSb ultrathin films has played valuable roles for designing high-performance, low-power integrated circuits, inter-band cascade lasers [

65] and next-generation flexible and portable electronic devices [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Optimum performance of various device structures, involving these epilayers is contingent on their structural and lattice dynamical characteristics. Vibrational and structural behavior is generally influenced by the film thickness, alloy composition, interfacial strain and epitaxial growth conditions, etc. [

8,

9,

10] In the nanostructured epilayers, the interaction of phonons with intrinsic and/or extrinsic charge carriers has been and still is a major issue for evaluating their role in thermal management, thermoelectric energy conversion, and thermal insulation of different electronic devices. Lack of such important basic traits has encouraged crystal growers to select appropriately the quaternary alloyed III-V semiconductor materials and meticulously prepare them epitaxially on different substrates viz., InAs, GaSb, GaAs and Si, etc. [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] Attempts are made by fine-tuning their structural and phonon properties for achieving specific electronic and optical responses in various electronic devices. Good quality InAs

1-x-yP

ySb

x/n-InAs (GaAs) samples of nearly ~1 mm thick films are successfully grown by GS-MBE technique. Systematic experimental measurements are performed on these epilayers by exploiting Raman scattering spectroscopy (cf.

Section 4.3), high resolution FTIR reflectivity (cf.

Section 4.4) and SR-EXAFS (cf.

Section 4.5) techniques. These methods have played valuable roles for comprehending their vibrational and structural characteristics.

Combining the experimental reflectivity data with a standard methodology of multilayer optics using TMM approach has helped us assessing the refractive index

and extinction coefficient

for both the epilayers and substrate. The values of

and

are used for modelling the reflectivity spectra to achieve a very good agreement with the experimental data. The FTIR reflectivity results have complemented the Raman scattering data and provided a complete picture of phonon characteristics in the InAs

1-x-yP

ySb

x /n-InAs samples. Composition-dependent phonon shifts, linewidths and Raman intensity peaks offered valuable information about the crystalline quality of InAs

1-x-yP

ySb

x epilayers. While sharp and intense peaks have indicated the high-quality materials, the broadened and/or weak intensity features pointed out either to the structural defects and/or disorder in the GS-MBE grown samples (cf.

Section 4.3). Most importantly, both the Raman scattering and FTIR reflectivity measurements have complemented each other by confirming a “three-phonon-mode” behavior in InAs

1-x-yP

ySb

x alloys. Vibrational frequencies of InAs-like, InSb-like, and InP-like modes are observed in these samples, while disorder-related dynamical features are noticed within and/or near the miscibility gap region. Defects previously described in the GS-MBE-grown InPSb epilayers [

67] are also expected here in InAsPSb samples with lower Sb content than remainder of the films.

Structural features of InAs

1-x-yP

ySb

x/GaAs epilayers are carefully examined by measuring the EXAFS oscillations well above the P K-edge and In K-edge (cf.

Section 4.5). By combining the standard procedures required to fit the EXAFS spectra with VFF approach [

63], we have analyzed the SR-EXAFS data for comprehending the alloys’ local atomic structures. In a complex InAsPSb alloy with a potential of phase separation, the SR-EXAFS method helped us characterizing the short-range order which otherwise cannot be adequately attained by HR-XRD [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Analysis of In K-edge spectra provided results of the average bond lengths between In and its nearest neighbor, P, As and Sb atoms. It has been recently argued [

66] that probing the P K-edge EXAFS spectra for different P-based materials is challenging as compared to the higher K-edge spectra due to potential self-absorption effects. In InAsPSb alloys, our analysis of P K-edge data offered complementary information of the local environment as obtained in the In K-edge spectra. Atomic positions in InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys are carefully estimated by minimizing the total energy [

41]. Once achieving the atomic positions with minimized energies in the quaternary alloys by VFF [

41], the results are exploited for simulating RSMs for estimating

az and

axy of InAsPSb epilayers for evaluating the distortion energy [

41]. The ratio

az/

axy has described the deformation of the crystal unit cell relative to its relaxed, unstrained state. Calculated results of the distortion energy in InAs

1-x-ySb

xP

y alloys are noticed decreasing as a function of

az/

axy with the increase of As composition. The simulations have also indicated that the distortion energy increases when the ratio

az/

axy deviates from 1 – suggesting that greater lattice distortion requires more energy.