Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Donor Horses and Sampling

2.2. Static In Vitro Batch Model Derived from SHIME® System

2.2.1. Determination of HGA Concentration in Batch System

2.2.3. Chemical Reagents and Consumable Materials

2.2.4. Static Batch Model

2.2.5. Sampling Procedure

2.3. Microbiota Assessment

2.3.1. Bacterial DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

2.3.2. Sequence Analysis and 16S rDNA Profiling

2.3.3. Microbiota Statistical Analysis

2.4. Quantification of Short Chain Fatty Acids and Statistical Analysis

2.5. Quantification of Hypoglycin A and Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Preliminary Assessment of Hypoglycin A Stability in the Nutritional Medium

2.5.2. Hypoglycin A Stability in the Nutritional Medium: Data Analysis

2.5.3. Hypoglycin A Concentration in the Batch Fermenters: Data Analysis

2.5.4. Normalised HGA Degradation Kinetics

2.6. Quantification of Methylenecyclopropylacetyl-Carnitine

3. Results

3.1. Donor Horses

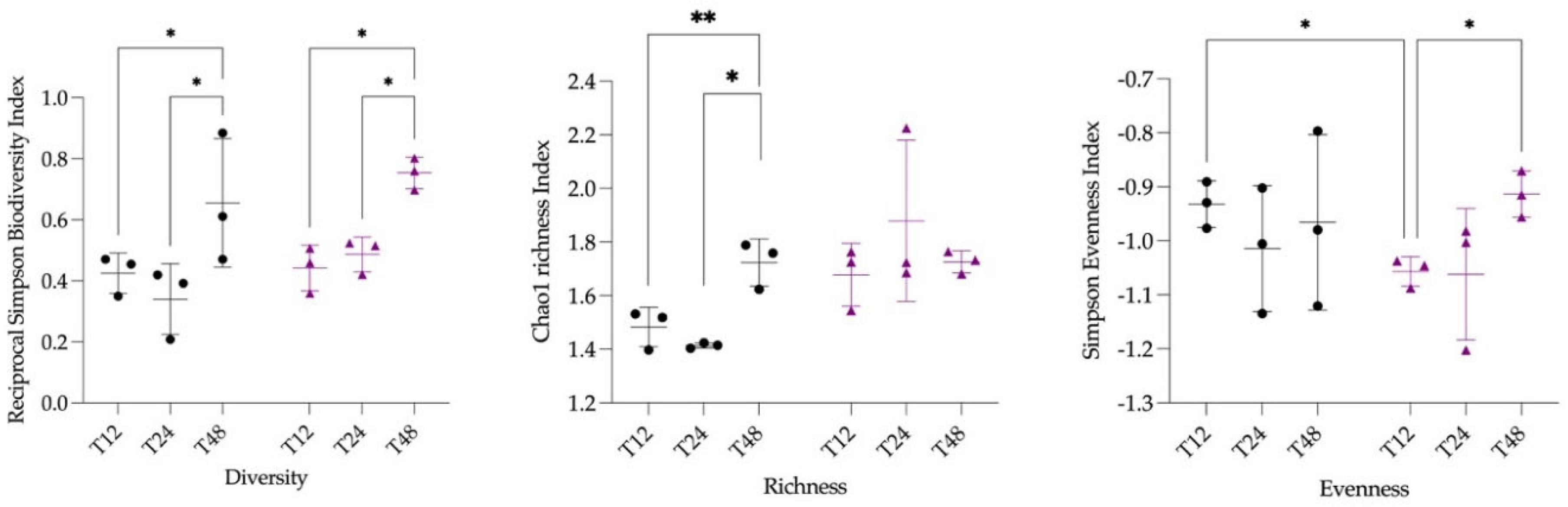

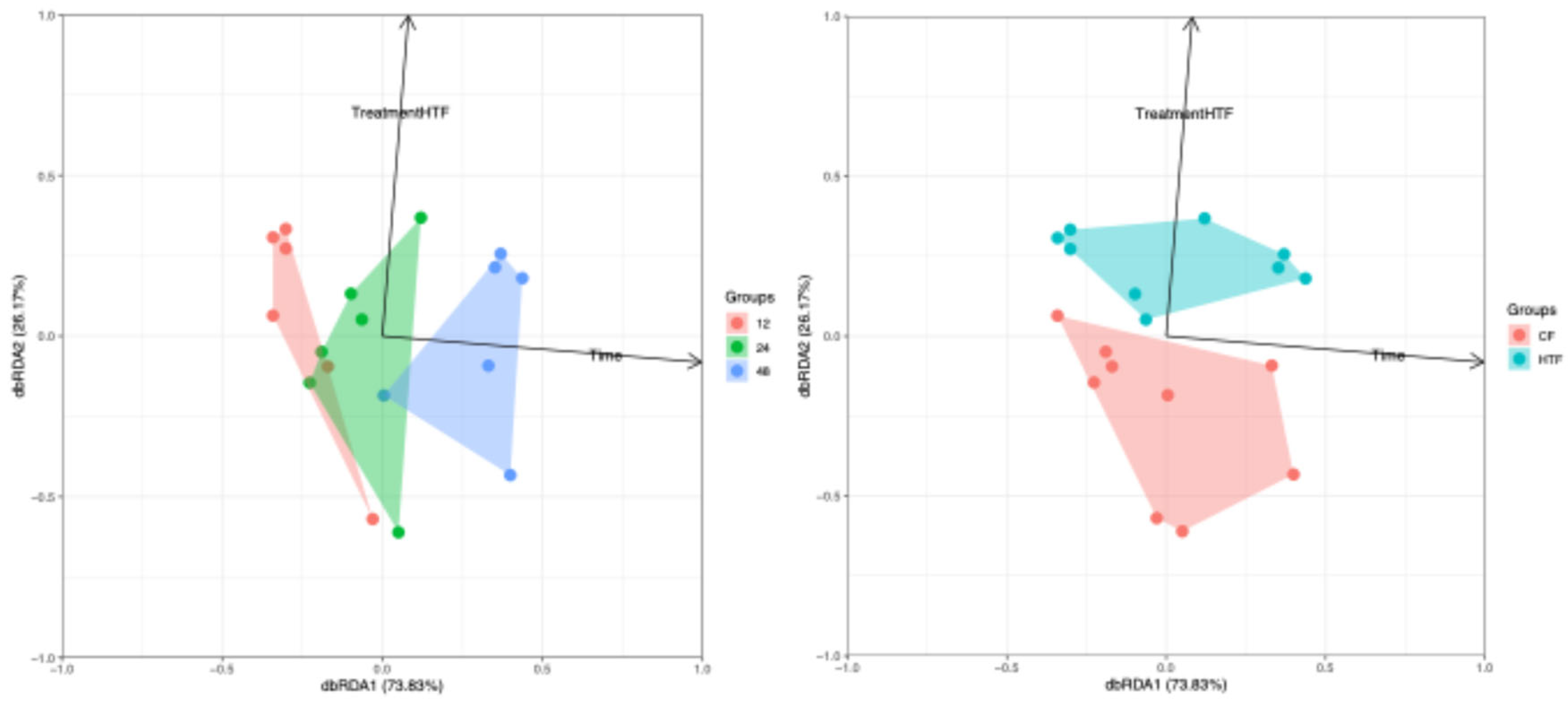

3.2. Microbiota Statistical Analysis

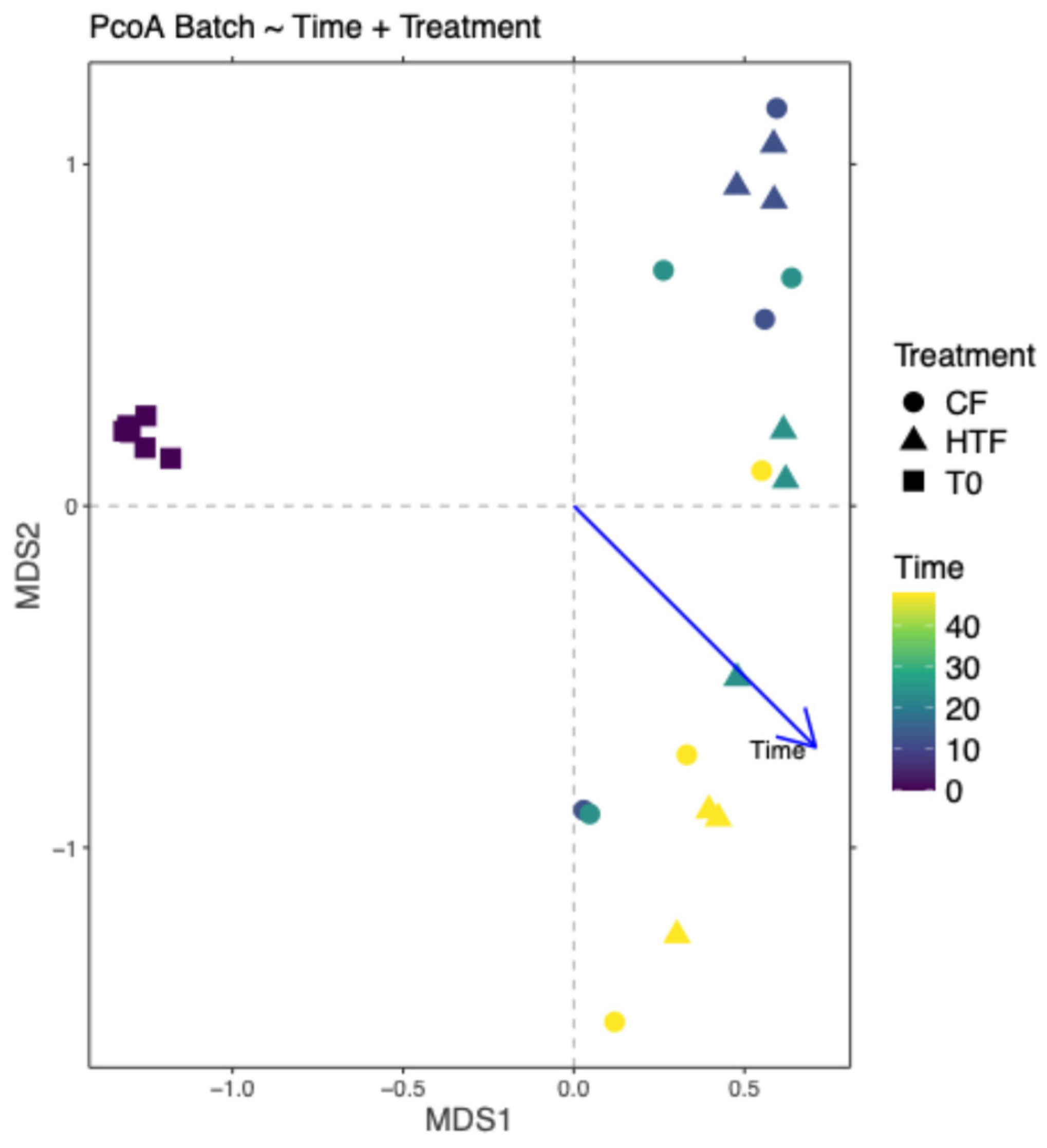

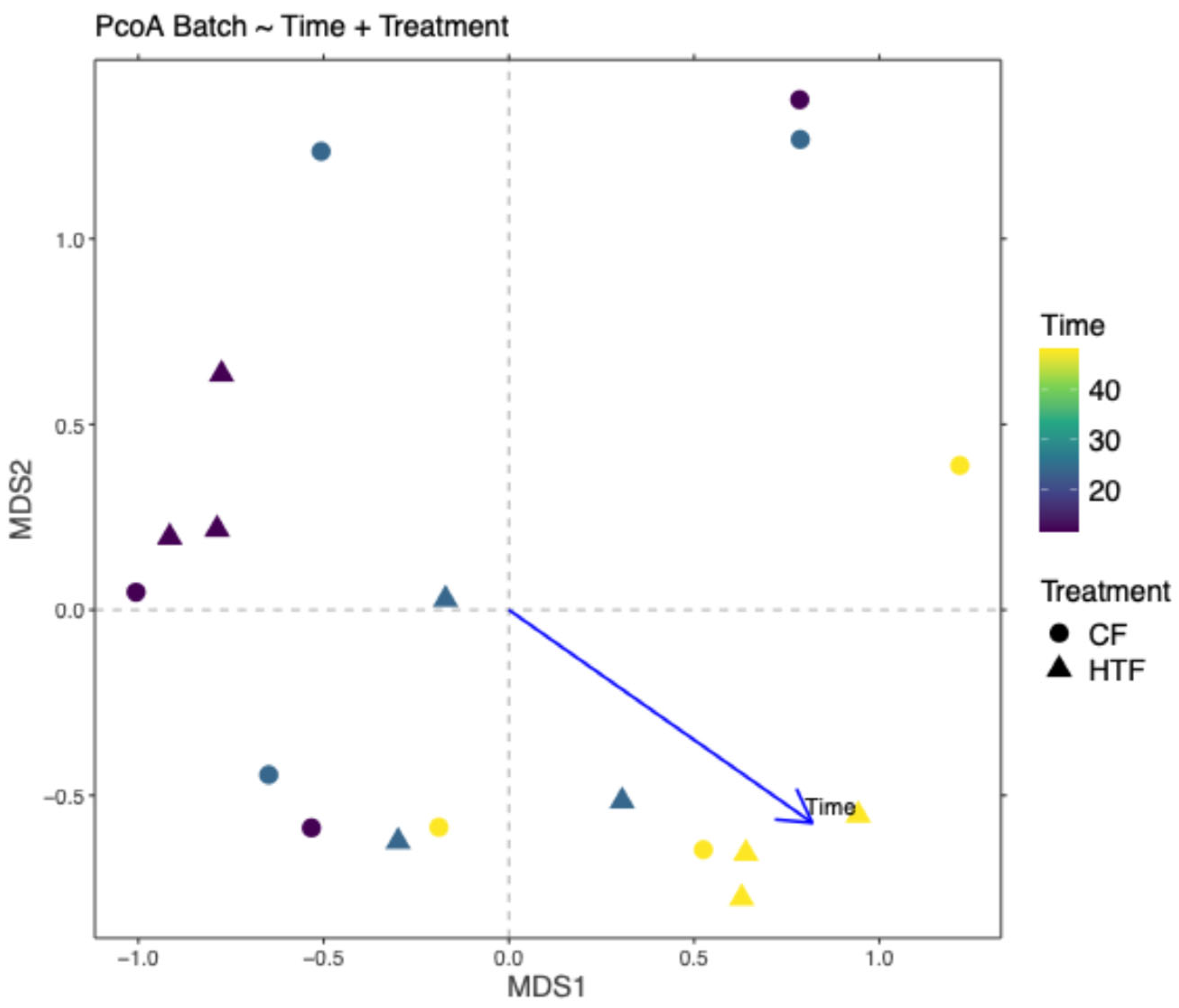

3.2.1. Composition of Microbiota

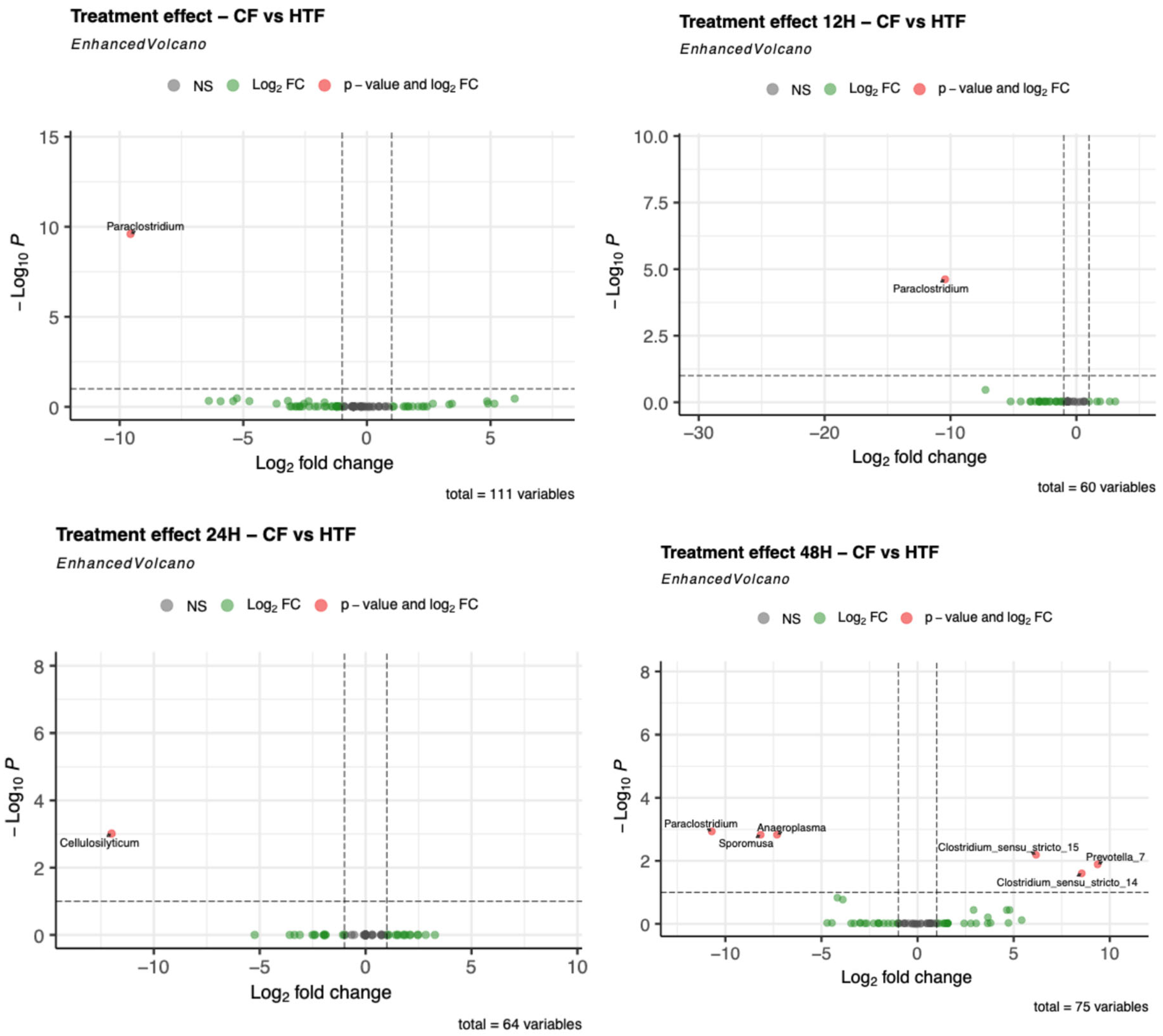

3.2.4. Differences in Microbiota Composition Between Groups

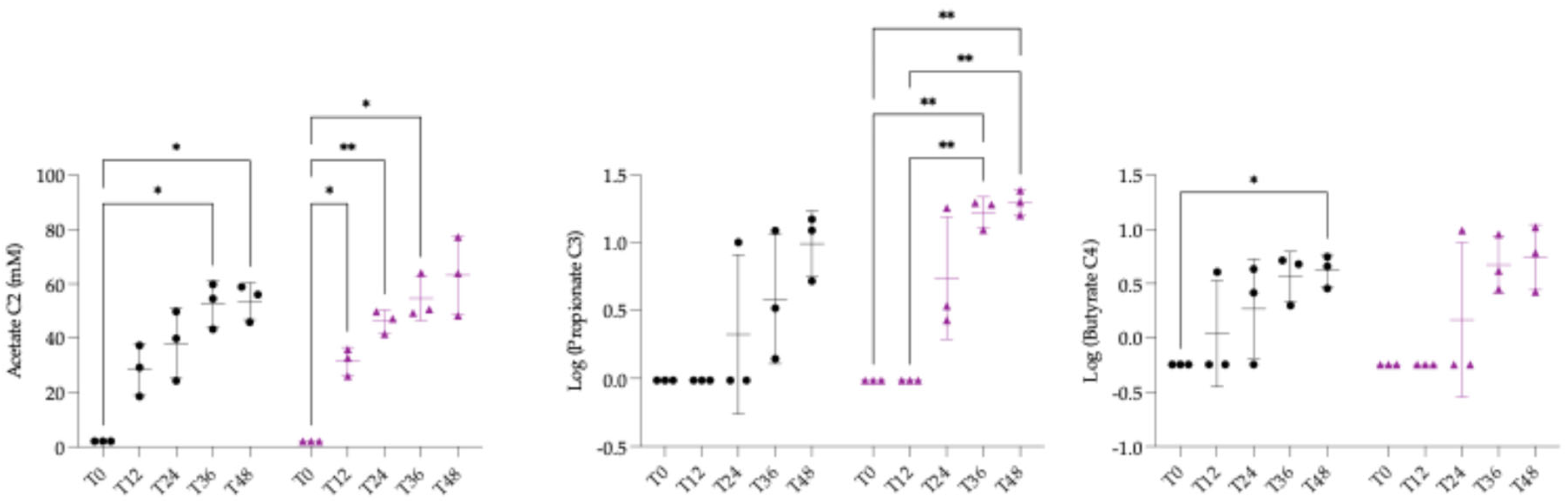

3.3. Quantification of Short Chain Fatty Acids and Statistical Analysis

3.4. Quantification of Hypoglycin A and Statistical Analysis

3.4.1. Stability of Hypoglycin A in the Nutritional Medium and Statistical Analysis

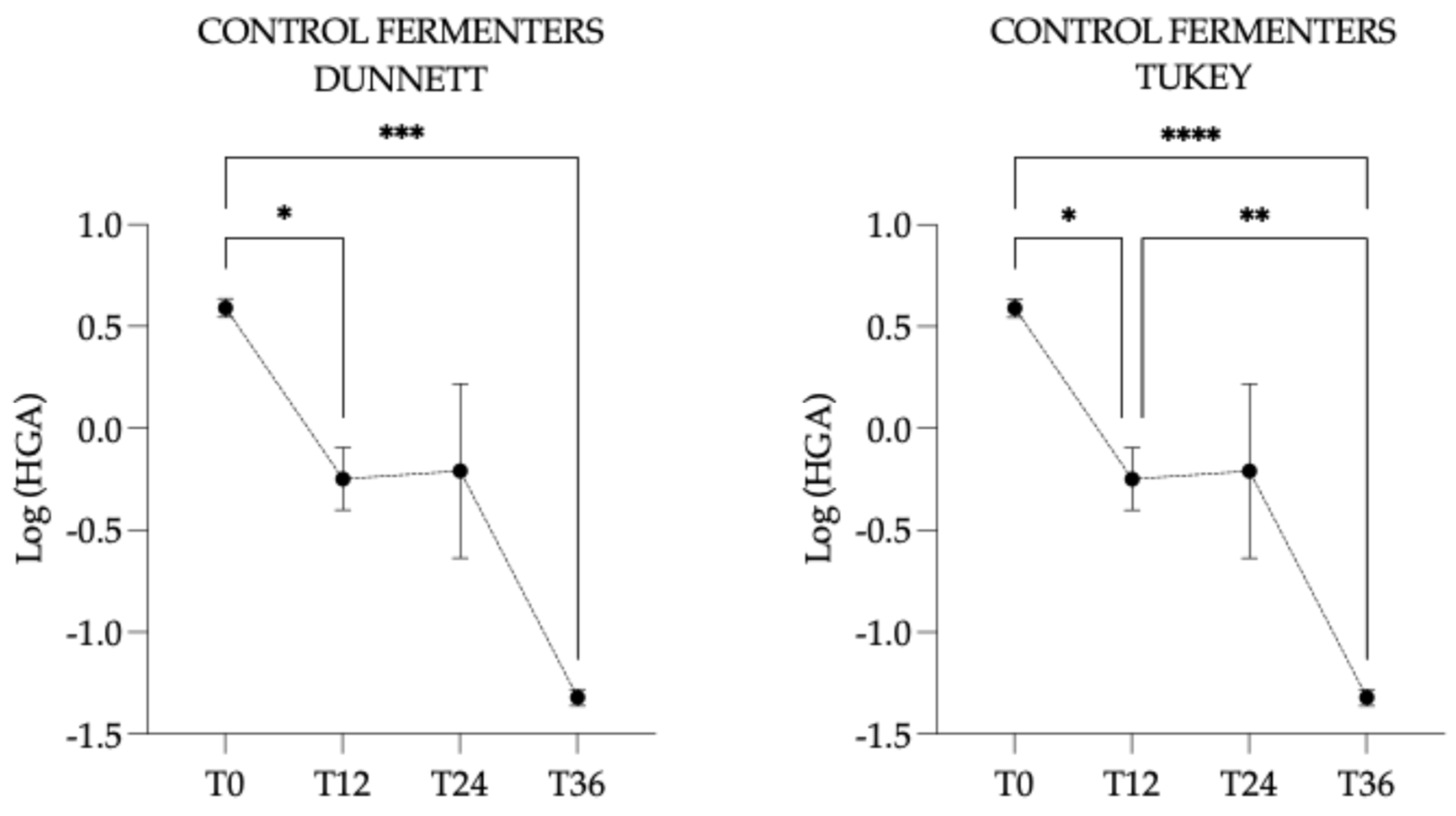

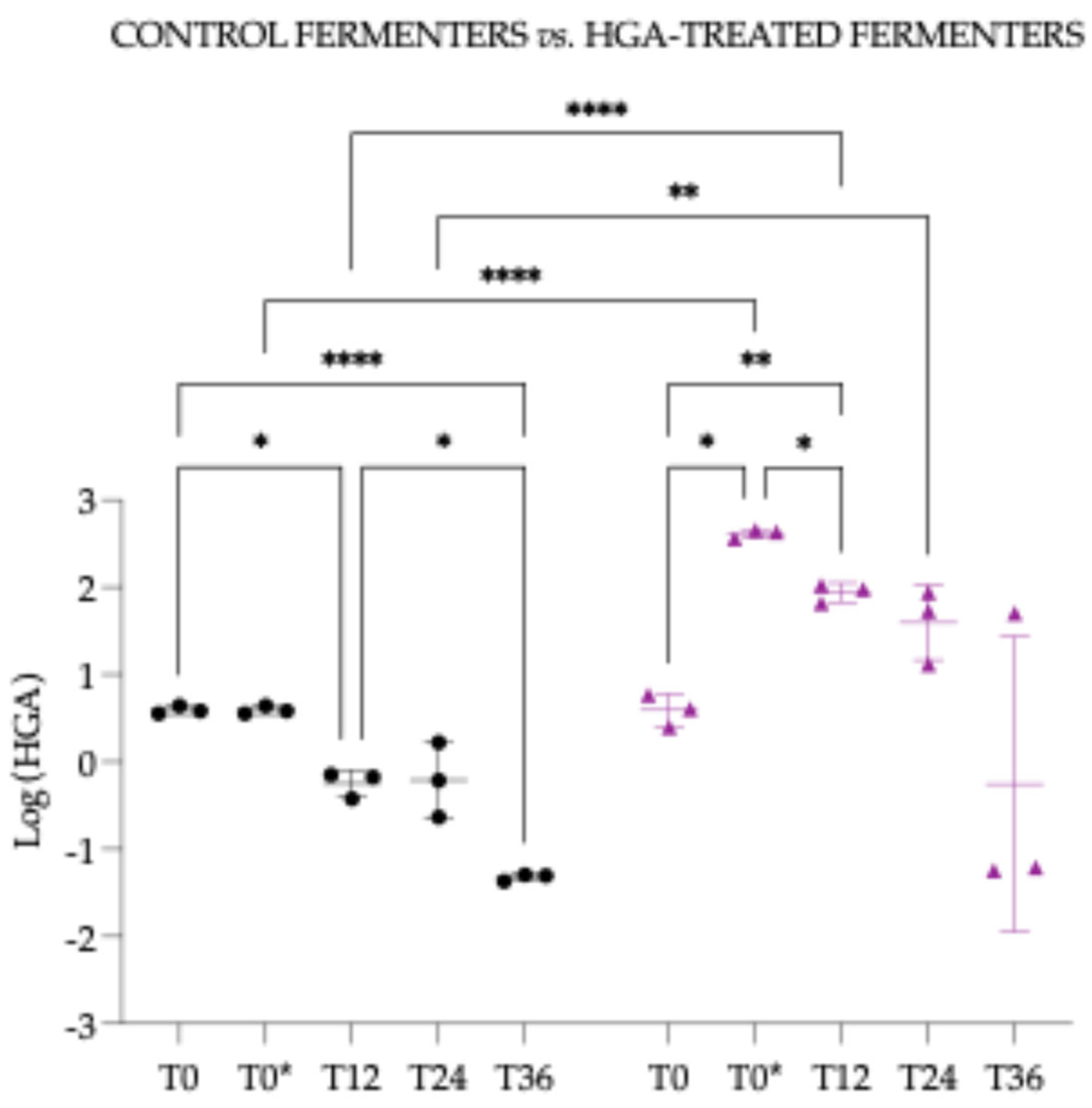

3.4.2. Hypoglycin A Concentration Within the Control Fermenters

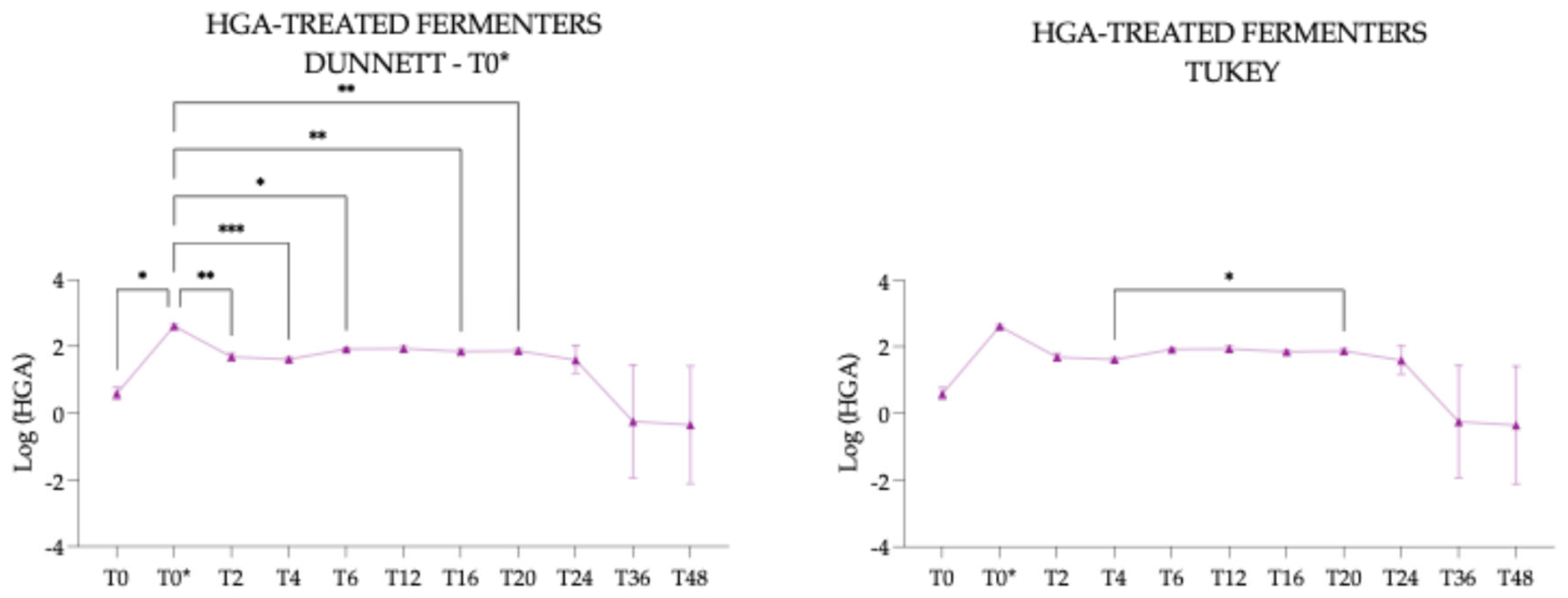

3.4.3. Hypoglycin A Concentration Within the Hypoglycin A-Treated Fermenters

3.4.4. Hypoglycin A Concentration Comparison Between “Control Fermenters” and “Hypoglycin A-Treated Fermenters”

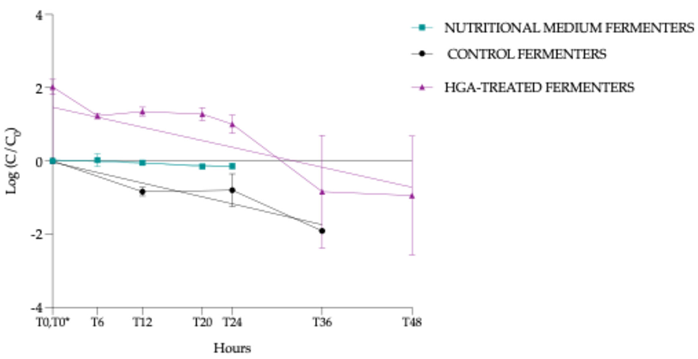

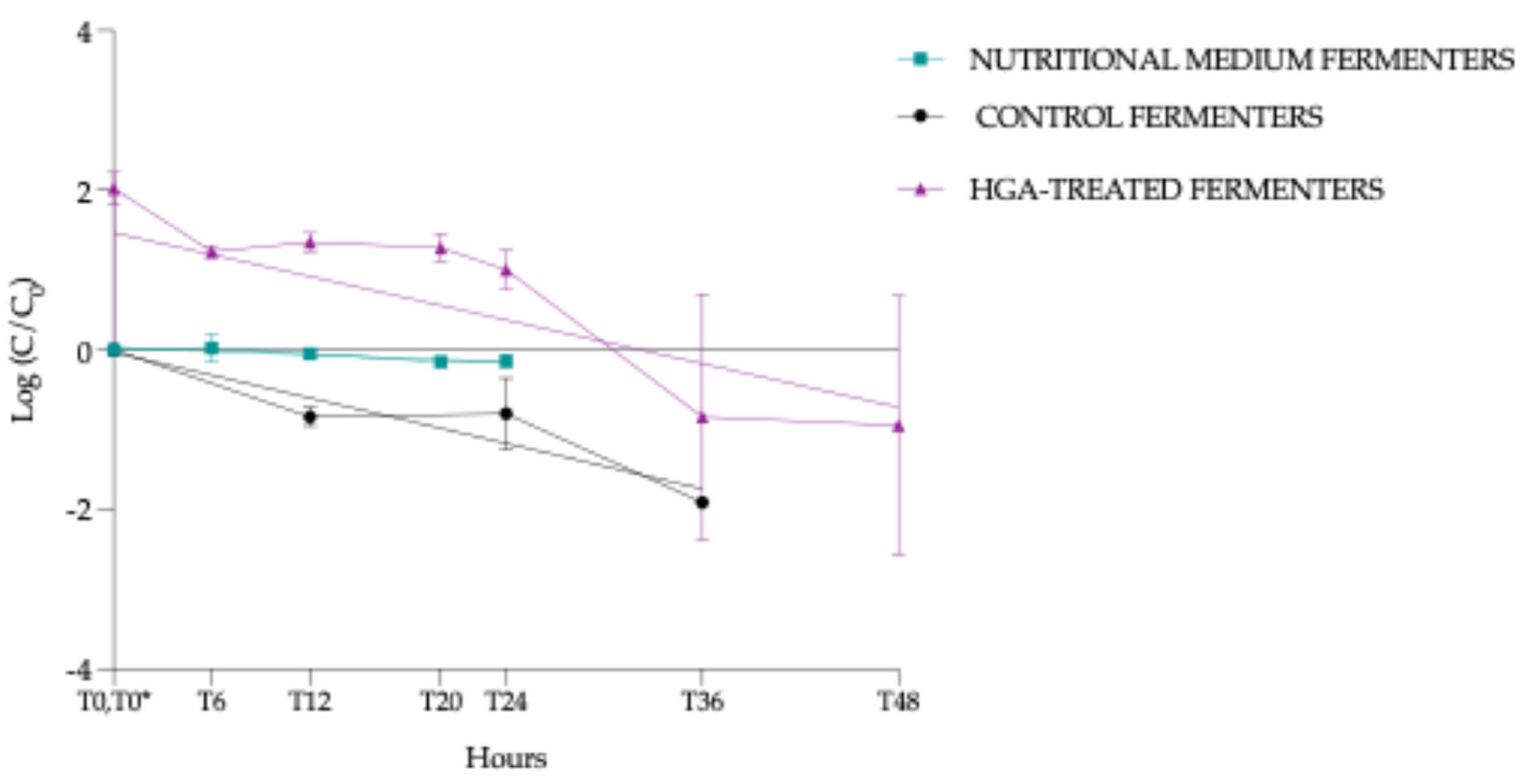

3.4.5. Normalised HGA Degradation Kinetics

- (i)

- NMF: slope - 0.00749 (95% confidence interval (Cl) = -0.013 à -0.0020, p = 0.0111, *)

- (ii)

- CF: slope -0.0474 (95% Cl = -0.063 à -0.0315, p < 0.0001, ***)

- (iii)

- HTF: slope -0.0455 (95% Cl= -0.073 à -0.0181, p = 0.0024, **)

3.5. Quantification of Methylenecyclopropylacetyl-Carnitine and Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Atypical myopathy |

| HGA | Hypoglycin A |

| MCPrG | Methylenecyclopropylglycine |

| BCAA | Branched chain amino acids |

| MCPA-CoA | Methylenecyclopropylacetyl-Coenzyme A |

| MCPA-carnitine | Methylenecyclopropylacetic acid-carnitine |

| MCPA-glycine | Methylenecyclopropylacetic acid-glycine |

| UPLC-MS/MS | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry |

| LOQ | Limit of quantification |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| MTD | Maximum tolerated dose |

| HED | Human equivalent dose |

| BSA | Body surface area |

| CF | Control fermenters |

| HTF | HGA-treated fermenters |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| ANOVA | Analysis Of Variance |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| dbRDA | Distance-based redundancy analysis |

| SPME | Solid phase microextraction |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry |

| LLOQ | Lower limits of quantification |

| ULOQ | Upper limits of quantification |

| NMF | Nutritional medium fermenters |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

Appendix A

Sampling Design and Analysis

References

- Votion, D.M.; van Galen, G.; Sweetman, L.; Boemer, F.; de Tullio, P.; Dopagne, C.; Lefère, L.; Mouithys-Mickalad, A.; Patarin, F.; Rouxhet, S.; et al. Identification of Methylenecyclopropyl Acetic Acid in Serum of European Horses with Atypical Myopathy. Equine Vet J 2014, 46, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baise, E.; Habyarimana, J.A.; Amory, H.; Boemer, F.; Douny, C.; Gustin, P.; Marcillaud-Pitel, C.; Patarin, F.; Weber, M.; Votion, D.M. Samaras and Seedlings of Acer Pseudoplatanus Are Potential Sources of Hypoglycin A Intoxication in Atypical Myopathy without Necessarily Inducing Clinical Signs. Equine Vet J 2016, 48, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, L.; Nicholson, A.; Jewitt, E.M.; Gerber, V.; Hegeman, A.; Sweetman, L.; Valberg, S. Hypoglycin A Concentrations in Seeds of Acer Pseudoplatanus Trees Growing on Atypical Myopathy-Affected and Control Pastures. J Vet Intern Med 2014, 28, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowden, L.; Pratt, H.M. Cyclopropylamino Acids of the Genus Acer. Phytochemistry 1973, 12, 1677–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochnia, M.; Sander, J.; Ziegler, J.; Terhardt, M.; Sander, S.; Janzen, N.; Cavalleri, J.M.V.; Zuraw, A.; Wensch-Dorendorf, M.; Zeyner, A. Detection of MCPG Metabolites in Horses with Atypical Myopathy. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.K.; Landor, S.R. A New Synthesis of Hypoglycin a; Pergamon Press Ltd., 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Billington, D.; Sherratt, H.S. Hypoglycin and Metabolically Related Inhibitors. 1981, 72, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khatib, A.H.; Engel, A.M.; Weigel, S. Co-Occurrence of Hypoglycin A and Hypoglycin B in Sycamore and Box Elder Maple Proved by LC-MS/MS and LC-HR-MS. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, P.C.; Patrick, S.J. Studies of the Action of Hypoglycin-A, an Hypoglycaemic Substance. J. Pharmacol 1958, 13, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunert, C.; Langer, S.; Votion, D.M.; Boemer, F.; Müller, A.; Ternes, K.; Liesegang, A. Atypical Myopathy in Père David’s Deer (Elaphurus Davidianus) Associated with Ingestion of Hypoglycin A. J Anim Sci 2018, 96, 3537–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, B.; Kruse, C.J.; François, A.C.; Grund, L.; Bunert, C.; Brisson, L.; Boemer, F.; Gault, G.; Ghislain, B.; Petitjean, T.; et al. Acer Pseudoplatanus: A Potential Risk of Poisoning for Several Herbivore Species. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.K.; Anderson, R.C.; Mccowen, M.C.; Harris, P.N. PHARMACOLOGIC ACTION OF HYPOGLYCIN A AND B. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1957, 121, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassall, C.H.; Reyle, K.; Feng, P. Hypoglycin A,B- Biologically Active Polypeptides from Blighia Sapida. Nature 1954, 173, 356–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirz, M.; Gregersen, H.A.; Sander, J.; Votion, D.M.; Schänzer, A.; Köhler, K.; Herden, C. Atypical Myopathy in 2 Bactrian Camels. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 2021, 33, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.O.; Burrows, W. The Vomiting Sickness of Jamaica, B. W. I. and Its Relation to Akee Poisoning. Am J Epidemiol 1937, 25, 520–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Kean, E.A.; Johnson, B. Jamaican Vomiting Sickness: Biochemical Investigation of Two Cases. N Engl J Med. 1976, 295, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, B.; Kruse, C.-J.; François, A.-C.; Cesarini, C.; van Loon, G.; Palmers, K.; Boemer, F.; Luis, G.; Gustin, P.; Votion, D.-M. Large-Scale Study of Blood Markers in Equine Atypical Myopathy Reveals Subclinical Poisoning and Advances in Diagnostic and Prognostic Criteria. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2024, 104515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, C.-J.; Stern, D.; Mouithys-Mickalad, A.; Niesten, A.; Art, T.; Lemieux, H.; Votion, D.-M. In Vitro Assays for the Assessment of Impaired Mitochondrial Bioenergetics in Equine Atypical Myopathy. Life 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Holt, C. Methylenecyclopropaneacetic Acid, a Metabolite of Hypoglycin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1966, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boemer, F.; Detilleux, J.; Cello, C.; Amory, H.; Marcillaud-Pitel, C.; Richard, E.; Van Galen, G.; Van Loon, G.; Lefère, L.; Votion, D.M. Acylcarnitines Profile Best Predicts Survival in Horses with Atypical Myopathy. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlíková, R.; Široká, J.; Jahn, P.; Friedecký, D.; Gardlo, A.; Janečková, H.; Hrdinová, F.; Drábková, Z.; Adam, T. Equine Atypical Myopathy: A Metabolic Study. Veterinary Journal 2016, 216, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, D.; Sass, J.O.; Graubner, C.; Schoster, A. Diagnosis of Atypical Myopathy Based on Organic Acid and Acylcarnitine Profiles and Evolution of Biomarkers in Surviving Horses. Mol Genet Metab Rep 2021, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochnia, M.; Ziegler, J.; Sander, J.; Uhlig, A.; Schaefer, S.; Vollstedt, S.; Glatter, M.; Abel, S.; Recknagel, S.; Schusser, G.F.; et al. Hypoglycin a Content in Blood and Urine Discriminates Horses with Atypical Myopathy from Clinically Normal Horses Grazing on the Same Pasture. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermann, C.M.; Dorland, L.; Votion, D.M.; de Sain-van der Velden, M.G.M.; Wijnberg, I.D.; Wanders, R.J.A.; Spliet, W.G.M.; Testerink, N.; Berger, R.; Ruiter, J.P.N.; et al. Acquired Multiple Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency in 10 Horses with Atypical Myopathy. Neuromuscular Disorders 2008, 18, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westermann, C.M.; de Sain-van der Velden, M.G.M.; van der Kolk, J.H.; Berger, R.; Wijnberg, I.D.; Koeman, J.P.; Wanders, R.J.A.; Lenstra, J.A.; Testerink, N.; Vaandrager, A.B.; et al. Equine Biochemical Multiple Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (MADD) as a Cause of Rhabdomyolysis. Mol Genet Metab 2007, 91, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuziel, G.A.; Lozano, G.L.; Simian, C.; Li, L.; Manion, J.; Stephen-Victor, E.; Chatila, T.; Dong, M.; Weng, J.K.; Rakoff-Nahoum, S. Functional Diversification of Dietary Plant Small Molecules by the Gut Microbiome. Cell 2025, 188, 1967–1983.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; An, K.; Su, J. Review: Mechanism of Herbivores Synergistically Metabolizing Toxic Plants through Liver and Intestinal Microbiota. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part - C: Toxicology and Pharmacology 2024, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska-van der Molen, M.A.; Berasategui-Lopez, A.; Coolen, S.; Jansen, R.S.; Welte, C.U. Microbial Degradation of Plant Toxins. Environ Microbiol 2023, 25, 2988–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.M.; El-Khatib, A.H.; Bachmann, M.; Wensch-Dorendorf, M.; Klevenhusen, F.; Weigel, S.; Pieper, R.; Zeyner, A. Release of Hypoglycin A from Hypoglycin B and Decrease of Hypoglycin A and Methylene Cyclopropyl Glycine Concentrations in Ruminal Fluid Batch Cultures. Toxins (Basel) 2025, 17, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Weese, J.S. Methods and Basic Concepts for Microbiota Assessment. Veterinary Journal 2019, 249, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer-Scherr, C.; Taminiau, B.; Renaud, B.; van Loon, G.; Palmers, K.; Votion, D.; Amory, H.; Daube, G.; Cesarini, C. Comparison of Fecal Microbiota of Horses Suffering from Atypical Myopathy and Healthy Co-Grazers. Animals 2021, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- François, A.-C.; Cesarini, C.; Taminiau, B.; Renaud, B.; Kruse, C.-J.; Boemer, F.; van Loon, G.; Palmers, K.; Daube, G.; Wouters, C.P.; et al. Unravelling Faecal Microbiota Variations in Equine Atypical Myopathy: Correlation with Blood Markers and Contribution of Microbiome. Animals 2025, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garber, A.; Hastie, P.; Murray, J.A. Factors Influencing Equine Gut Microbiota: Current Knowledge. J Equine Vet Sci 2020, 88, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, L.; Leduc, L.; Leclère, M.; Costa, M.C. Current Understanding of Equine Gut Dysbiosis and Microbiota Manipulation Techniques: Comparison with Current Knowledge in Other Species. Animals 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Walton, G.; Swann, J.; Darby, A.; Ragione, R. La; Proudmana, C. “Bowel on the Bench”: Proof of Concept of a Three-Stage, in Vitro Fermentation Model of the Equine Large Intestine. Appl Environ Microbiol 2020, 86, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowman, R.S.; Theodorou, M.K.; Hyslop, J.J.; Dhanoa, M.S.; Cuddeford, D. Evulation of an in Vitro Batch Culture Technique for Estimating the in Vivo Digestibility and Digestible Energy Content of Equine Feeds Using Equine Faeces as the Source of Microbial Inoculum. Anim Feed Sci Technol 1999, 80, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boemer, F.; Deberg, M.; Schoos, R.; Baise, E.; Amory, H.; Gault, G.; Carlier, J.; Gaillard, Y.; Marcillaud-Pitel, C.; Votion, D. Quantification of Hypoglycin A in Serum Using ATRAQ® Assay. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2015, 997, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valberg, S.J.; Sponseller, B.T.; Hegeman, A.D.; Earing, J.; Bender, J.B.; Martinson, K.L.; Patterson, S.E.; Sweetman, L. Seasonal Pasture Myopathy/Atypical Myopathy in North America Associated with Ingestion of Hypoglycin A within Seeds of the Box Elder Tree. Equine Vet J 2013, 45, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, M.; Ramiro-Garcia, J.; Koenen, M.E.; Venema, K. To Pool or Not to Pool? Impact of the Use of Individual and Pooled Fecal Samples for in Vitro Fermentation Studies. J Microbiol Methods 2014, 107, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, O.A.; Bennink, M.R.; Jackson, J.C. Ackee (Blighia Sapida) Hypoglycin A Toxicity: Dose Response Assessment in Laboratory Rats. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2006, 44, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.B.; Jacob, S. A Simple Practice Guide for Dose Conversion between Animals and Human. J Basic Clin Pharm 2016, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leśniak, K.; Whittington, L.; Mapletoft, S.; Mitchell, J.; Hancox, K.; Draper, S.; Williams, J. The Influence of Body Mass and Height on Equine Hoof Conformation and Symmetry. J Equine Vet Sci 2019, 77, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.S. Take a Deeper Look into Body Surface Area. Nursing (Brux) 2019, 49, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintz, H.F. Digestive Physiology of the Horse. J S Afr Vet Assoc 1975, 46, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Molly, K.; Woestyne, M. Vande; Smet, I. De; Verstraete, W. Validation of the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME) Reactor Using Microorganism-Associated Activities. Microb Ecol Health Dis 1994, 7, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goya-Jorge, E.; Bondue, P.; Gonza, I.; Laforêt, F.; Antoine, C.; Boutaleb, S.; Douny, C.; Scippo, M.L.; de Ribaucourt, J.C.; Crahay, F.; et al. Butyrogenic, Bifidogenic and Slight Anti-Inflammatory Effects of a Green Kiwifruit Powder (Kiwi FFG®) in a Human Gastrointestinal Model Simulating Mild Constipation. Food Research International 2023, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merritt, A.M.; Julliand, V. Gastrointestinal Physiology. In Equine Applied and Clinical Nutrition; Geor, R.J., Harris, P.A., Coenen, M., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, 2013; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Joskow, R.; Belson, M.; Vesper, H.; Backer, L.; Rubin, C. Ackee Fruit Poisoning: An Outbreak Investigation in Haiti 2000-2001, and Review of the Literature. Clin Toxicol 2006, 44, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, S.; Taminiau, B.; de Lusancay, A.H.C.; Lecoq, L.; Amory, H.; Daube, G.; Cesarini, C. Effect of Oral Administration of Omeprazole on the Microbiota of the Gastric Glandular Mucosa and Feces of Healthy Horses. J Vet Intern Med 2020, 34, 2727–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing Mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahé, F. VSEARCH: A Versatile Open Source Tool for Metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpso, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Package “vegan” - Community Ecology Package Available online:. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/vegan.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Kers, J.G.; Saccenti, E. The Power of Microbiome Studies: Some Considerations on Which Alpha and Beta Metrics to Use and How to Report Results. Front Microbiol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.K.; Caruso, T.; Buscot, F.; Fischer, M.; Hancock, C.; Maier, T.S.; Meiners, T.; Müller, C.; Obermaier, E.; Prati, D.; et al. Choosing and Using Diversity Indices: Insights for Ecological Applications from the German Biodiversity Exploratories. Ecol Evol 2014, 4, 3514–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Chazdon, R.L.; Shen, T.J. A New Statistical Approach for Assessing Similarity of Species Composition with Incidence and Abundance Data. Ecol Lett 2005, 8, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Kindt, R.; Simpson, G. Package “vegan3d” - Static and Dynamic 3D and Editable Interactive Plots for the “Vegan” Package Available online:. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan3d/vegan3d.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Martinez Arbizu, P. PairwiseAdonis: Pairwise Multilevel Comparison Using Adonis_. R Package Version 0.4. Available online: https://github.com/pmartinezarbizu/pairwiseAdonis (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Douny, C.; Dufourny, S.; Brose, F.; Verachtert, P.; Rondia, P.; Lebrun, S.; Marzorati, M.; Everaert, N.; Delcenserie, V.; Scippo, M.L. Development of an Analytical Method to Detect Short-Chain Fatty Acids by SPME-GC–MS in Samples Coming from an in Vitro Gastrointestinal Model. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2019, 1124, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Medina, S.; Hyde, C.; Lovera, I.; Piercy, R.J. Detection of Hypoglycin A and MCPA-Carnitine in Equine Serum and Muscle Tissue: Optimisation and Validation of a LC-MS–Based Method without Derivatisation. Equine Vet J 2021, 53, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavao, A.; Graham, M.; Arrieta-Ortiz, M.L.; Immanuel, S.R.C.; Baliga, N.S.; Bry, L. Reconsidering the in Vivo Functions of Clostridial Stickland Amino Acid Fermentations. Anaerobe 2022, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britz, M.L.; Wilkinson, R.G. Leucine Dissimilation to Isovaleric and Isocaproic Acids by Cell Suspensions of Amino Acid Fermenting Anaerobes: The Stickland Reaction Revisited. Can J Microbiol 1981, 28, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.-L.; Wu, G.; Zhu, W.Y. Amino Acid Metabolism in Intestinal Bacteria- Links between Gut Ecology and Host Health. Front Biosci 2011, 16, 1768–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, A.M.; Blachier, F.; Gotteland, M.; Andriamihaja, M.; Benetti, P.H.; Sanz, Y.; Tomé, D. Intestinal Luminal Nitrogen Metabolism: Role of the Gut Microbiota and Consequences for the Host. Pharmacol Res 2013, 68, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, E.N. Energy Contributions of Volatile Fatty Acids From the Gastrointestinal Tract in Various Species. Physiol Rev 1990, 70, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryde, S.E.; Duncan, S.H.; Hold, G.L.; Stewart, C.S.; Flint, H.J. The Microbiology of Butyrate Formation in the Human Colon. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2002, 217, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, S.H.; Holtrop, G.; Lobley, G.E.; Calder, A.G.; Stewart, C.S.; Flint, H.J. Contribution of Acetate to Butyrate Formation by Human Faecal Bacteria. British Journal of Nutrition 2004, 91, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Diversity, Metabolism and Microbial Ecology of Butyrate-Producing Bacteria from the Human Large Intestine. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2009, 294, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Medina, S.; Bevin, W.; Alzola-Domingo, R.; Chang, Y.M.; Piercy, R.J. Hypoglycin A Absorption in Sheep without Concurrent Clinical or Biochemical Evidence of Disease. J Vet Intern Med 2021, 35, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Meijere, A. Bonding Properties of Cyclopropane and Their Chemical Consequences. Angewandte Chemie 1979, 18, 809–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.L.; Cox, M.M.; Hoskins, A. Principles of Biochemistry, 8th ed.; Freeman, W.H., Ed.; Macmillan International, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bressler, R.; Corredor, C.; Brendel, K. HYPOGLYCIN AND HYPOGLYCIN-LIKE COMPOUNDS. Pharmacol Rev. 1969, 21, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magasanik, B. Catabolite Repression. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 1961, 26, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jones, V. V. The Structure of Leucenol. J Am Chem Soc 1947, 69, 1803–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, A.F. On the Structure of Leucaenine (Leucaenol) from Leucaena Glauca Bentham. J Am Chem Soc 1947, 69, 1801–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.J. Does Ruminal Metabolism of Mimosine Explain the Absence of Leucaena Toxicity in Hawaii? Aust Vet J 1981, 57, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.J.; Lowry, J.B. Australian Goats Detoxify the Goitrogen 3-Hydroxy-4(IH) Pyridone (DHP) after Rumen Infusion from an Indone-Sian Goat. Experientia 1984, 40, 1435–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.J.; Megarrity, R.G. Successful Transfer of DHP-Degrading Bacteria from Hawaiian Goats to Australian Ruminants to Overcome the Toxicity of Leucaena. Aust Vet J. 1986, 63, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, M.J.; Mayberry, W.R.; Mcsweeney, C.S.; Stahl, D.A. Synergistes Jonesii, Gen. Nov., Sp.Nov.: A Rumen Bacterium That Degrades Toxic Pyridinediols. Syst Appl Microbiol 1992, 15, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, M.J.; Hammond, A.C.; Jones, R.J. Detection of Ruminal Bacteria That Degrade Toxic Dihydroxypyridine Compounds Produced from Mimosine. Appl Environ Microbiol 1990, 56, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraille, M.; Buttet, M.; Grimm, P.; Milojevic, V.; Julliand, S.; Julliand, V. Changes of Faecal Bacterial Communities and Microbial Fibrolytic Activity in Horses Aged from 6 to 30 Years Old. PLoS One 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theelen, M.J.P.; Luiken, R.E.C.; Wagenaar, J.A.; van Oldruitenborgh-Oosterbaan, M.M.S.; Rossen, J.W.A.; Zomer, A.L. The Equine Faecal Microbiota of Healthy Horses and Ponies in The Netherlands : Impact of Host and Environmental Factors. Animals 2021, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Chao, Y.; Li, Y.; Peng, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, K. Effect of Gender Bias on Equine Fecal Microbiota. J Equine Vet Sci 2021, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Galen, G.; Saegerman, C.; Marcillaud Pitel, C.; Patarin, F.; Amory, H.; Baily, J.D.; Cassart, D.; Gerber, V.; Hahn, C.; Harris, P.; et al. European Outbreaks of Atypical Myopathy in Grazing Horses (2006-2009): Determination of Indicators for Risk and Prognostic Factors. Equine Vet J 2012, 44, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votion, D.M.; François, A.C.; Kruse, C.; Renaud, B.; Farinelle, A.; Bouquieaux, M.C.; Marcillaud-pitel, C.; Gustin, P. Answers to the Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Horse Feeding and Management Practices to Reduce the Risk of Atypical Myopathy. Animals 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, K.A.; Rogers, C.W.; Gee, E.K.; Kittelmann, S.; Bolwell, C.F.; Bermingham, E.N.; Biggs, P.J.; Thomas, D.G. Resilience of Faecal Microbiota in Stabled Thoroughbred Horses Following Abrupt Dietary Transition between Freshly Cut Pasture and Three Forage-Based Diets. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, K.A.; Gee, E.K.; Rogers, C.W.; Kittelmann, S.; Biggs, P.J.; Bermingham, E.N.; Bolwell, C.F.; Thomas, D.G. Seasonal Variation in the Faecal Microbiota of Mature Adult Horses Maintained on Pasture in New Zealand. Animals 2021, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspa, F.; Chessa, S.; Bergero, D.; Sacchi, P.; Ferrocino, I.; Cocolin, L.; Corvaglia, M.R.; Moretti, R.; Cavallini, D.; Valle, E. Microbiota Characterization throughout the Digestive Tract of Horses Fed a High-Fiber vs. a High-Starch Diet. Front Vet Sci 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.E.; Maddox, T.W.; Berg, A.; Antczak, P.; Ketley, J.M.; Williams, N.J.; Archer, D.C. Variation in Faecal Microbiota in a Group of Horses Managed at Pasture over a 12-Month Period. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Sacy, A.; Karges, K.; Apper, E. Gastro-Intestinal Microbiota in Equines and Its Role in Health and Disease: The Black Box Opens. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krägeloh, T.; Cavalleri, J.M.V.; Ziegler, J.; Sander, J.; Terhardt, M.; Breves, G.; Cehak, A. Identification of Hypoglycin A Binding Adsorbents as Potential Preventive Measures in Co-Grazers of Atypical Myopathy Affected Horses. Equine Vet J 2018, 50, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, C.H.; Urschel, K.L. Amino Acid Requirements in Horses. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2020, 33, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, P.G.; Potter, G.D.; Schelling, G.T.; Kreider, J.L.; Boyd, C.L. DIGESTION OF HAY PROTEIN IN DIFFERENT SEGMENTS OF THE EQUINE DIGESTIVE TRACT. J Anim Sci 1988, 66, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitnour, C.M.; Salsbury, R.L. Digestion and Utilization of Cecally Infused Protein by the Equine. J. Anim Sci 1972, 35, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glade, M.J. NITROGEN PARTITIONING ALONG THE EQUINE DIGESTIVE TRACT. J Anim Sci 1983, 57, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.D.; Holcombe, S.J.; Steibel, J.P.; Staniar, W.B.; Colvin, C.; Trottier, N.L. Cationic and Neutral Amino Acid Transporter Transcript Abundances Are Differentially Expressed in the Equine Intestinal Tract. J Anim Sci 2010, 88, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, L.M.; Bishop, R.; Morris, J.G.; Robinson, D.W. Digestion and Absorption of 15N-Labelled Microbial Protein in the Large Intestine of the Horse. Br Vet J 1971, 127, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neis, E.P.J.G.; Dejong, C.H.C.; Rensen, S.S. The Role of Microbial Amino Acid Metabolism in Host Metabolism. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2930–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pairs | p-value adjusted | |

|---|---|---|

| T12 vs. T24 | 0.5416 | nsig |

| T12 vs. T48 | 0.0189 | * |

| T24 vs. T48 | 0.0265 | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).