1. Introduction

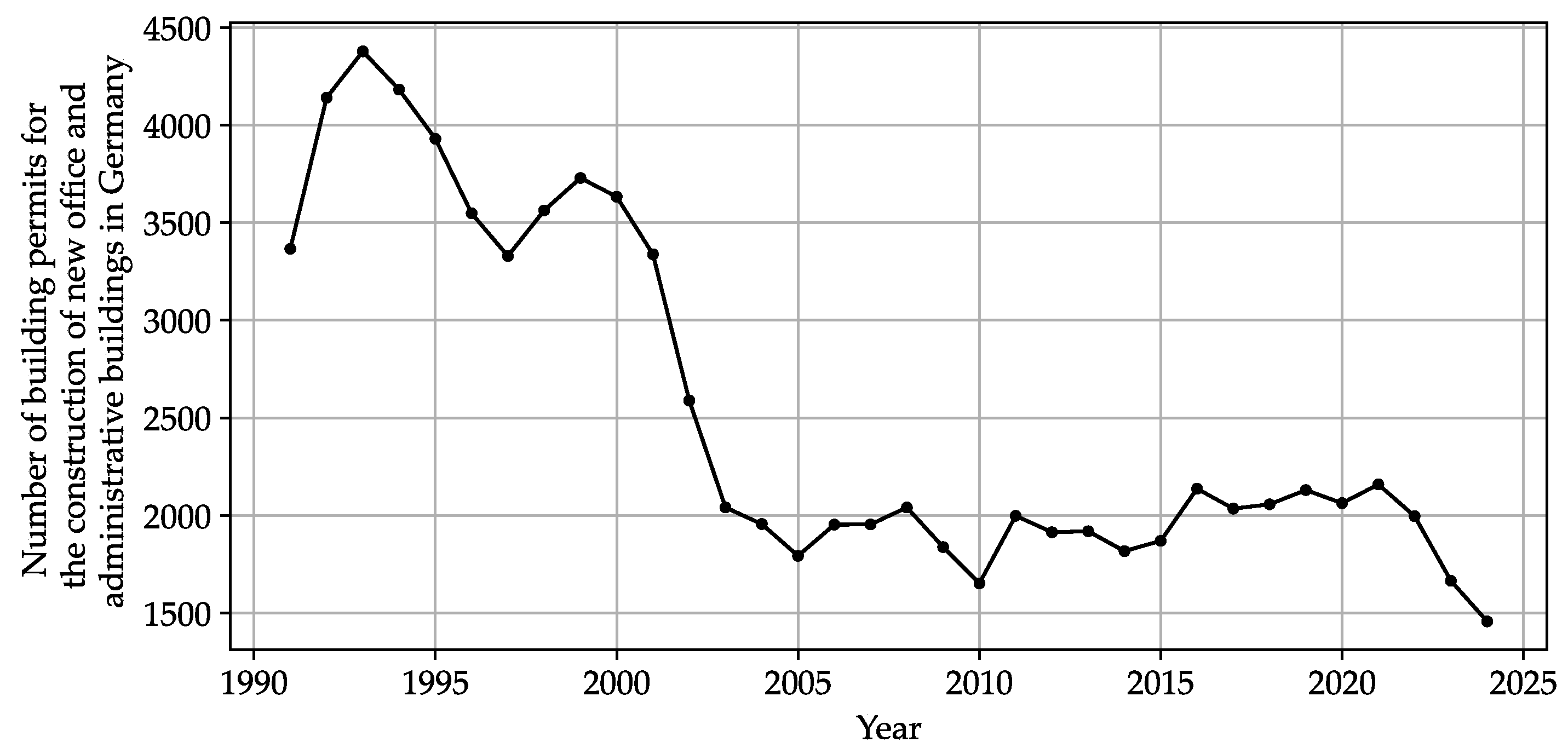

In recent years, construction costs in Germany have exhibited pronounced volatility, which may have been influenced by external factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. These cost fluctuations have contributed to a slowdown in office and administrative building initiations measured in permission numbers (

Figure 1), as developers and contractors face greater uncertainty in budgeting and scheduling.

Empirical evidence suggests also a measurable decline in construction output [

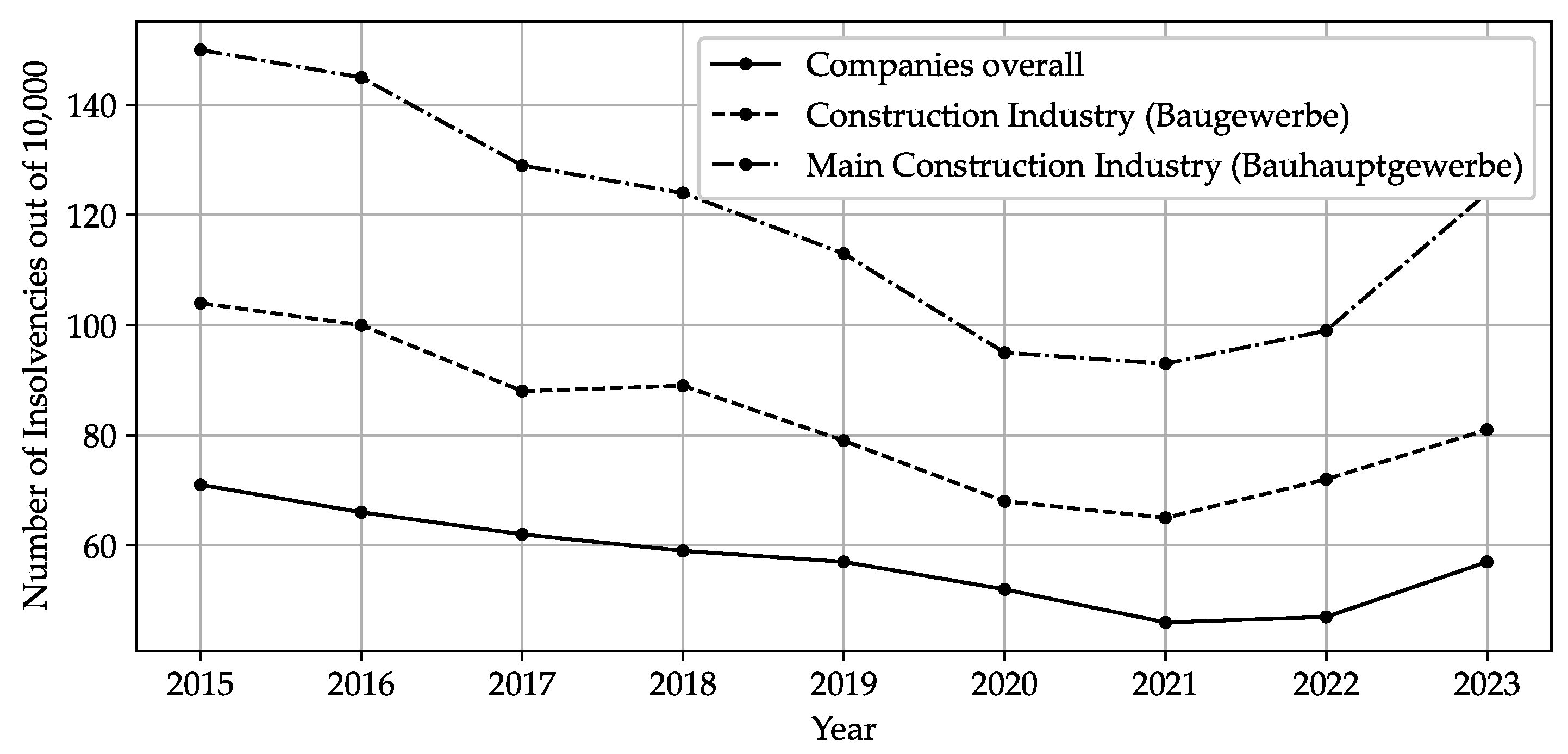

2]. Concurrently, as

Figure 2 shows, insolvency rates in the construction industry have risen, reflecting increased financial stress among market participants.

To address growing planning risks and improve cost control, this paper conducts a comprehensive analysis of 35 sub-construction-price indices for office buildings in Germany and generates forecasts over a one-year horizon. By leveraging regularized VARX-L models introduced by Nicholson et al. [

4], which are available as the BigVAR package in RStudio, our methodology captures interdependencies among sub-indices and produces accurate short- and medium-term projections. The modular framework can be readily updated and applied to future forecasting exercises, offering practitioners and policymakers a robust tool for anticipating price trends and mitigating risk in a volatile market environment. Forecast accuracy is further assessed by benchmarking the high-dimensional BigVAR forecasts against compact VARX models augmented with macroeconomic covariates with performance evaluated by MAPE and RMSE.

2. Literature Research

The importance of this topic is underscored by a growing academic literature. A systematic search in the Scopus database (see search string in

Appendix A.1) identified 29 relevant studies on forecasting construction price indices in the building sector since 2005. Numerous additional contributions address related questions in the civil-engineering and infrastructure context.

In what follows, we provide a concise overview of the identified studies. For clarity, we organize the corpus by primary methodological emphasis into: univariate (

2.1) and multivariate (

2.2) time-series analyses, machine-learning approaches (

2.3), network-based methods (

2.4), and hybrid models (

2.5). Studies that primarily compare methods or do not fit neatly into a single category—particularly those benchmarking alternative models—are grouped under comparative studies (

2.6).

2.1. Univariate Time-Series Analyses

Ashuri and Lu [

5] compare the applicability and predictive performance of univariate time-series models for construction cost indices (CCIs) and find that a seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (SARIMA) model provides the highest in-sample forecasting accuracy, while Holt–Winters exponential smoothing is the most accurate model for out-of-sample forecasts. Moon and Shin [

6] build a univariate interrupted ARIMA for Engineering News-Record (ENR) CCI that embeds the June 2008 recession as an intervention and consistently beats ARIMA and Holt–Winters on a 12-month holdout. Moon, Chi, and Kim [

7] confirm long memory in ENR CCI via rescaled range analysis and show that the developed autoregressive fractionally integrated moving average (ARFIMA) model delivers on average 9.5% lower average mean absolute percentage error than ARIMA. Zhao, Mbachu, and Zhang [

8] show on New Zealand residential building cost indices that Holt–Winters exponential smoothing is more accurate for one- and two-story houses, while seasonal ARIMA is superior for townhouses, apartments, and retirement villages, concluding that both are reliable depending on data characteristics.

2.2. Multivariate Time-Series Analyses

Shahandashti and Ashuri [

9] identify vector error correction (VEC) models as appropriate for forecasting ENR’s CCI and show that bivariate VEC models (CCI and producer price index (PPI), CCI and crude oil price) outperform univariate approaches such as seasonal ARIMA and Holt–Winters exponential smoothing in out-of-sample predictions. Xu and Moon [

10] develop a bivariate cointegrated vector autoregression (VAR) (CCI and CPI) and show on 2006–2010 out-of-sample tests that it delivers significantly lower errors than Holt–Winters benchmarks, while also offering stochastic (Monte Carlo) forecasts for uncertainty and risk assessment. Moon and Shin [

11] develop a VEC model-based CCI forecasting method using Google search query frequencies, select “project manager salary” as the final driver from 396 candidates via cointegration and diagnostics, and show it outperforms a CPI-based cointegrated VAR benchmark. Choi, Ryu, and Shahandashti [

12] examine city-level CCIs for 20 U.S. cities and evaluate four linear forecasting approaches, including ARIMA and VEC models augmented with macroeconomic indicators. They find no universally best model—the top performer depends on the city. Their guidance: use multivariate models when local leading indicators are available; otherwise, opt for a parsimonious ARIMA.

2.3. Machine Learning

The first machine learning approach in the identified works was applied by Wang and Ashuri [

13]. The authors apply two algorithms — k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) and perfect random tree ensembles (PERT) — to forecast the ENR CCI. Both methods improve forecast accuracy over benchmark time-series models (ARIMA, seasonal ARIMA, and VAR with CCI and CPI/PPI) across short-, mid-, and long-term horizons. Dong, Chen, and Guan [

14] use an long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network to forecast a CCI, leveraging 16 economic, energy, and market indicators to capture timeliness and long-range dependence. Compared with an support vector machine (SVM) baseline, the LSTM achieves higher short-term accuracy with less tuning; results hinge on careful feature selection but are limited by sparse data and a short-horizon focus. In the last machine learning paper examined Al Kailani et al. [

15] evaluate k-NN, random forest, and XGBoost algorithms for forecasting Jordan’s CCI, benchmarking them against linear regression and ARIMA. All three machine learning models outperform the traditional baselines; random forest attains the best accuracy, with the lowest MAPE and RMSE.

2.4. Network-Based Approaches

We now move on to the recently widespread network-based approaches: Zhang, Ashuri, and Deng [

16] propose a two-stage forecasting model that first converts a time series into a visibility graph and uses link prediction to produce preliminary forecasts; these are then adjusted by a rule-based fuzzy-logic system. Using both in-sample and out-of-sample tests on CCI, TAIEX, and student-enrollment series, the model attains high predictive accuracy; for the CCI case, it outperforms benchmark methods (Holt exponential smoothing, Holt–Winters, ARIMA, seasonal ARIMA). Zhang et al. [

17] also present a network-based approach in which time series are first converted into a visibility graph and future values are predicted via link prediction. In one-step-ahead forecasts, the proposed model achieves lower MAPE than simple moving average (SMA) and SARIMA but higher mean squared error (MSE) and mean absolute error (MAE). In multi-step forecasts, the method outperforms SARIMA in terms of MAPE; for longer-horizon forecasts its accuracy is mid-pack compared with other approaches. Mao and Xiao [

18] transform ENR CCI into a visibility graph, use link-prediction to derive node similarity, generate two forecasts (adjacent and linear-approximation) and combine them with distance weights, achieving slightly lower MAPE than SMA and Zhang et al.’s network baseline. Hu and Xiao [

19] propose a reconstructing-forecasting method: A series is reconstructed, mapped to a directed visibility graph, and an improved random walk yields node-similarity–based probability distributions for the next value. On CCI (and other series), it outperforms ARIMA, SARIMA, and a prior visibility-graph baseline and shows robustness to observational noise. In their second work in 2022 Hu and Xiao [

20] propose an efficient time-series forecaster that converts a series into a visibility graph and computes node similarity via a new multi-subgraph similarity measure. The normalized similarity distribution is then used to predict the next value. The method was tested with CCI and financial data and compared to ARIMA, SARIMA and Holt-Winters benchmarks. The presented method consistently achieved the highest prediction accuracy. Hu and Xiao [

21] introduce a network self-attention approach for forecasting, in which a time series is mapped to a visibility graph, node features are derived via random walks and an Recurrent NN learns similarity scores that are Softmax-normalized to weight the next-step prediction. On CCI data the method achieves the lowest error vs. ARIMA, SARIMA, and a prior visibility-graph baseline from Zhang et al. [

16]. In the subsequent year Hu and Xiao [

22] introduce prediction based on fuzzy similarity distribution (PFSD), a time-series forecaster built on the fuzzy cognitive visibility graph: the series is mapped to a directed, weighted graph, node similarity is computed via a new weighted multi-subgraph similarity metric, and a fuzzy similarity distribution is used for prediction. In benchmarks against ARIMA, exponential smoothing, and feedforward NNs, PFSD attains state-of-the-art accuracy on annual and quarterly datasets, but its performance deteriorates at long horizons due to diminishing memory effects. A novel forecasting method that converts time series into visibility graphs and computes node similarity via a superposed random walk is proposed by Zhan and Xiao [

23]. Unlike prior approaches, it forms predictions by weighted averaging over multiple similar nodes rather than using only the single closest match. Tested on CCIs among other series, the method attains the lowest forecast errors across all examined cases.

2.5. Hybrid Approaches

Combined – so-called hybrid – approaches in the field are presented now: Cao et al. [

24] propose a new approach—the self-adaptive structural radial basis neural network intelligence machine to forecast Taiwan’s CCI. In a first step, multivariate adaptive regression splines analyze the importance of different factors for the CCI; the factors identified as significant are then fed into a radial basis function NN for prediction. The model outperforms competing artificial intelligence (AI)/statistical baselines as well as ARIMA models. Xie and Fang [

25] developed a hybrid forecasting model for a CCI that combines a grey model with a backpropagation neural network. The hybrid model’s accuracy is compared with the respective single models. For one of the two forecasted quarterly values, the hybrid model shows a slight reduction in error; for the other quarter, it does not improve over the single approaches. Zhao et al. [

26] employ a transfer-function modeling framework—integrating time-series analysis, regression, and cross-correlation—to forecast the building cost index in New Zealand. Compared with a univariate ARIMA benchmark, the proposed model attains lower prediction errors, as measured by MAPE and RMSE. Kim et al. [

27] propose a hybrid ARIMA–Artificial NN (ANN) model for city-level CCI and, versus standalone ARIMA and ANN, report higher accuracy across short-, medium-, and long-term horizons at both national and city scales. Improvements in precision are attributed to ARIMA’s linear and ANN’s nonlinear modeling strengths. Myrvang and Liu [

28] compare a hybrid ARIMA-ANN, ARIMA and ANN for forecasting construction cost indices over medium- (5-year) and long-term (10-year) horizons. The hybrid model performs best at the medium horizon, while the ANN yields the most accurate long-term forecasts.

2.6. Comparative Studies

Finally, works are presented that primarily represent comparative studies. Hwang [

29] contrasts classical linear regression with dynamic regression and shows that the latter yields superior ex post, out-of-sample forecasting performance. Hwang [

30] develops a univariate autoregressive moving average (ARMA)(5,5) and a multivariate VAR(12) model (with CPI) for forecasting the ENR CCI, finds ARMA(5,5) slightly more accurate than VAR(12), shows both beat simple industry averaging methods, and notes that dynamic regression models marginally outperform the new time-series models in his comparisons. Elfahham [

31] compares in his work the forecasting accuracy of neural networks, linear regression, and univariate autoregressive time-series analysis using the Egyptian construction cost index, which he also derives, and finds that the most accurate results are achieved with univariate autoregressive time-series models. Aslam et al. [

32] conducted a similar study: The authors derive a materials-based construction cost index for Pakistan and use the different forecasting models NN, linear regression and autoregressive model for CCI predictions. Evaluated by mean error, RMSE, MAE, and Theil’s U, the neural network achieves the highest accuracy while the regression and autoregressive model perform similarly with only slightly larger errors. Aydinli [

33] evaluates with Holt–Winters, ARIMA, long-short term memory (LSTM), and gated recurrent units four models on monthly CCIs for nine European countries under two scenarios (S1: stable; S2: fluctuating) and three horizons (12/24/36 months). In the short term, models distinguish S1 from S2, but S1 leaders rarely lead in S2 and few differences are statistically significant—suggesting limited short-term impact of shocks on costs and forecast accuracy—whereas in the medium and long term S1–S2 gaps become significant, with machine learning (especially LSTM) often outperforming Holt–Winters/ARIMA, though no single model dominates across countries.

2.7. Literature Summary

Summarizing, the literature has not identified a universally superior method for forecasting construction price indices; predictive accuracy depends on data availability, horizon length, and the stochastic properties of the series. Distinct from prior work—typically single-series analyses or small bivariate systems—this study jointly models a large panel (35) of interrelated office-building price indices to deliver finer-grained, decision-relevant forecasts for budgeting and cost control. Regularized VARX models are well suited to this task. First, they are able to capture cross-series dynamics and feedback, making use of all available information compared to separate univariate models. Second, the exogenous component accommodates seasonal dummies and common price dynamics that affect multiple indices simultaneously, enabling realistic responses to economy-wide shocks and scenario-based planning. Third, shrinkage controls parameter proliferation in short samples, stabilizing estimation when T is limited. As a reference method, we also considered compact VARX specifications augmented with macroeconomic covariates (GDP, CPI, three-month interbank rate), but these benchmarks delivered inferior out-of-sample accuracy in our setting. We therefore adopt regularized VARX as the core framework for this paper.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

The empirical analysis draws on the construction price indices for office buildings published by Germany’s Federal Statistical Office [

34]. The indices are published in GENESIS table 61261-0002. The individual indices measure the temporal (quarterly) evolution of construction service prices and are rebased to 100 in a designated base year. Currently, prices for 183 "price representatives" (individual construction services) are surveyed quarterly by the state statistical offices from roughly 5,000 construction firms. Raw observations are first aggregated to state indices ("State measurement figures") and then to national indices ("National measurement figures") using turnover-based weights. Finally, building-specific weighting schemes [

35] combine the price representatives into indices at different levels of granularity, enabling reporting for both detailed trades and higher aggregates. [

36] In total, the dataset comprises 36 subindices, though not all are available from the beginning of the sample.

Table 1 summarizes the number of complete series, the number of late-starting series, and the observation count per series.

As the table indicates, the most recently introduced series contains only 18 observations. If all 36 series were included in a specification with four lags and four exogenous variables, ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation would entail, per equation,

regressors (

; see model explanation in

section 3.2). Adding the observations lost to lagging and one degree of freedom implies a minimum of 158 observations per series. Because a data share of only

is small even for regularized models, the newest series is excluded from the analysis. Restricting attention to the remaining 35 series already yields

of the sample size required for an OLS fit per equation, making a regularized approach substantially more tractable.

For one of the two model configurations, the VARX specification is augmented with German macroeconomic indicators GDP, CPI, and the three month interbank rate. Quarterly GDP is drawn from Germany’s Federal Statistical Office [

37], whereas CPI and the interest rate are sourced from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED) [

38,

39]. Because CPI and the interest rate are reported monthly, we use the observations corresponding to the study’s quarterly timestamps.

3.2. Forecasting Method

3.2.1. VARX-Models

A VARX model with

k endogenous and

m exogenous time series, of lag orders

, can be written as

where

is the

k-dimensional vector of endogenous variables at time

t,

is a

coefficient matrix associated with the

ℓ-th lag of

.

is a

k-dimensional intercept vector and

a

k-dimensional innovation vector assumed to be white noise. The exogenous regressors are collected in

, and

denotes the corresponding

coefficient matrix at exogenous lag

j [

2].

The coefficient matrices are obtained by minimizing the multivariate least-squares criterion given by

see [

2]. Here,

denotes the Frobenius norm,

. The matrices

and

denote the combined engogenous and exogenous coefficient matrices

respectively

of all lags considered. It follows that a

specification requires estimating

parameters.

3.2.2. Regularized VARX-Models

Because the number of parameters grows quadratically, VARX models quickly reach their limits when samples are low-frequency or otherwise short relative to the dimensionality of the system. To address this challenge, Nicholson, Matteson, and Bien [

2] developed the VARX-L framework, which transfers Lasso-style regularization to vector time series and thereby substantially reduces the effective parameter space. An implementation is available in the open-source R package BigVAR.

The core idea is to reduce the number of active coefficients via penalty terms. Accordingly, the general estimation problem in Equation

2 is augmented as follows:

The terms

and

denote penalty functions applied to the endogenous and exogenous coefficient blocks, respectively. The shared penalty parameter

governs the strength of regularization and must be selected as part of model estimation. Specifically, equation

3 accommodates different penalty functions.

Table 2 summarizes the variants considered: Lag, Own/Other, Sparse Lag, Sparse Own/Other, Basic and Endogenous-First.

In the lag-group specification, the entire coefficient matrix for each endogenous lag is treated as a single block, whereas for the exogenous variables each individual series forms its own group at each lag. The authors recommend this penalty when the series are similar—such as subindex series-making it a promising choice for the present application. The Own/Other model further partitions the endogenous coefficient matrices into diagonal (“own”) and off-diagonal (“other”) groups, aiming to capture settings with pronounced autocorrelation or cross-correlation. The Sparse Lag variant allows individual coefficients within an otherwise active lag block to be shrunk to zero. Sparse Own/other extends this idea to the diagonal/off-diagonal partition. The Basic approach is computationally efficient and permits elementwise zeroing in both endogenous and exogenous coefficient matrices. Finally, the Endogenous-first penalty imposes a hierarchy in which exogenous predictors (and their coefficients) may enter at a given lag only if the corresponding endogenous predictors have been selected. [

4]

3.3. Study Procedure

We implement and investigate two configurations of VARX models that differ in scope and dimensionality. In the low-dimensional models ("mVARX"), each target index is forecast individually, and the target index together with a compact set of macroeconomic variables are modeled jointly as the endogenous block; cross-series lags from other construction indices are not included, which keeps these specifications computationally light and data-sparse. In the high-dimensional models ("BigVAR"), by contrast, all indices are forecast jointly, allowing dynamic spillovers and common shocks to propagate across the panel; because the parameter space grows quickly, these systems are estimated with shrinkage/regularization using the methods explained above. We compare the ex post out-of-sample performance of both configurations and use the better-performing specification to generate ex-ante forecasts of the construction price indices.

3.3.1. Conventional VARX-Models with Macroeconomic Variables (mVARX)

The first model group consists of conventional VARX systems. For each of the 35 target series, we estimate a small VARX in which the endogenous block comprises the target index together with three macroeconomic indicators—real gross domestic product (GDP), the consumer price index (CPI), and the three-month interbank rate in germany. Exogenous terms are restricted to three seasonal dummy variables (quarter-of-year indicators). Prior to estimation, all series are tested for stationarity using the augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test. Series that appear non-stationary are differenced as required. In total, 35 VARX systems are estimated. The lag order is considered, and the final specification for each system is selected using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

3.3.2. Regularized VARX-Models with Price Dynamimcs Indicator (BigVAR)

As a second approach, we employ regularized VARX models (see

Section 3.2.2) that jointly model and forecast a large set of construction price indices. As in the small-scale models in

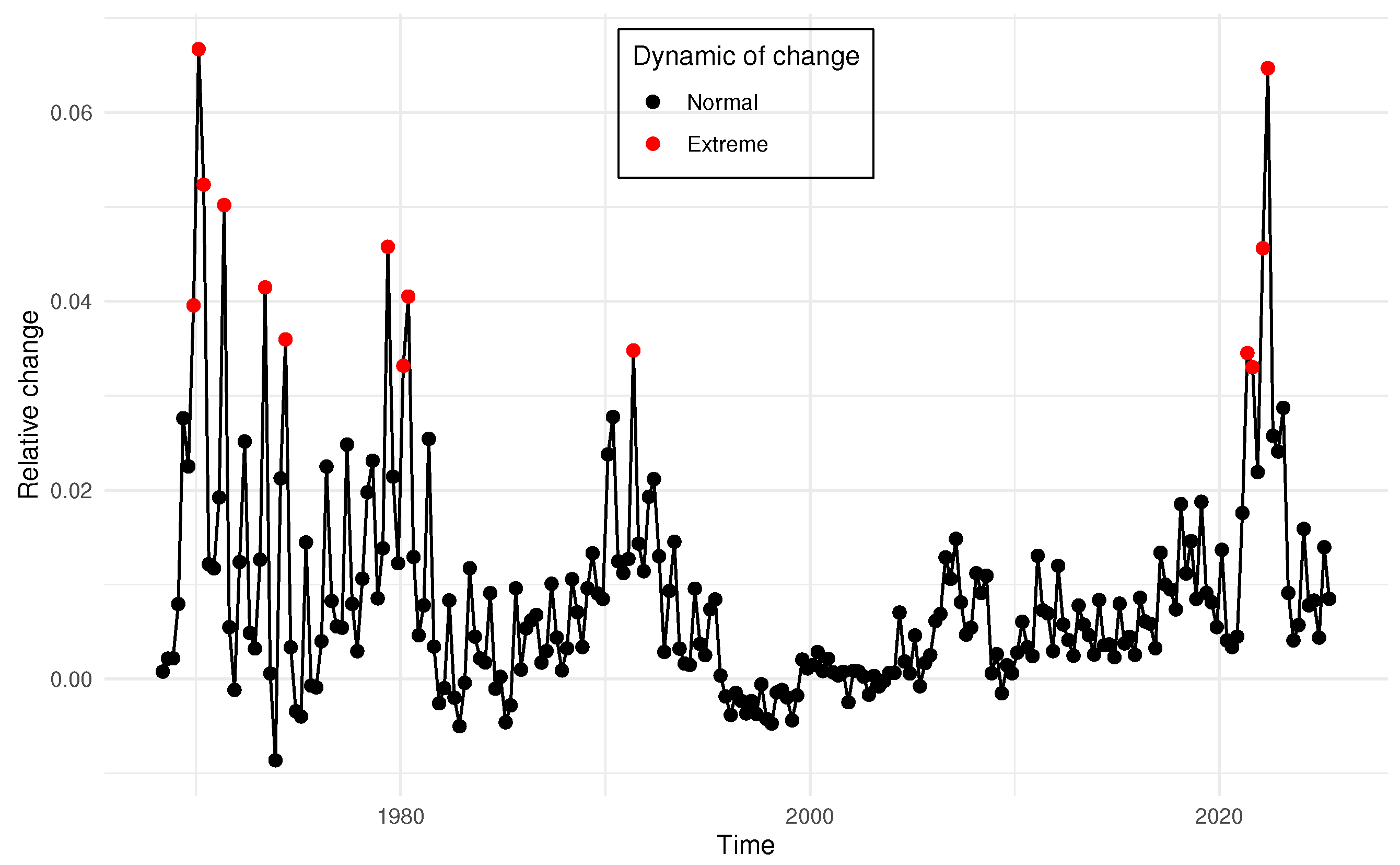

Section 3.3.1, seasonal effects are captured by quarterly dummy variables included as exogenous regressors. We deliberately exclude macroeconomic variables because the system is already high-dimensional and reliable ex-ante forecasts for these covariates are unavailable over our evaluation window. To enable a subsequent comparison between phases of elevated and subdued price movements, we derive from the data a classification indicator that tags each period as either dynamic or non-dynamic with respect to price movements. The construction of this indicator is described next.

For the identification of historical periods with dynamic price developments, we compute the Z-value on the relative changes of the aggregate construction price index

(see

Section 3.1), where

and

denote the mean and standard deviation over the estimation window [

40, p. 6]:

A period is classified as exhibiting high price dynamics if

. This decision rule implies that the observed change deviates from the estimation-window mean by at least two standard deviations in absolute terms. Values below this threshold are treated as non-remarkable with respect to price movement. The resulting classification is shown in

Figure 3, with dynamic periods marked by red dots. In total, 14 dynamic periods are identified.

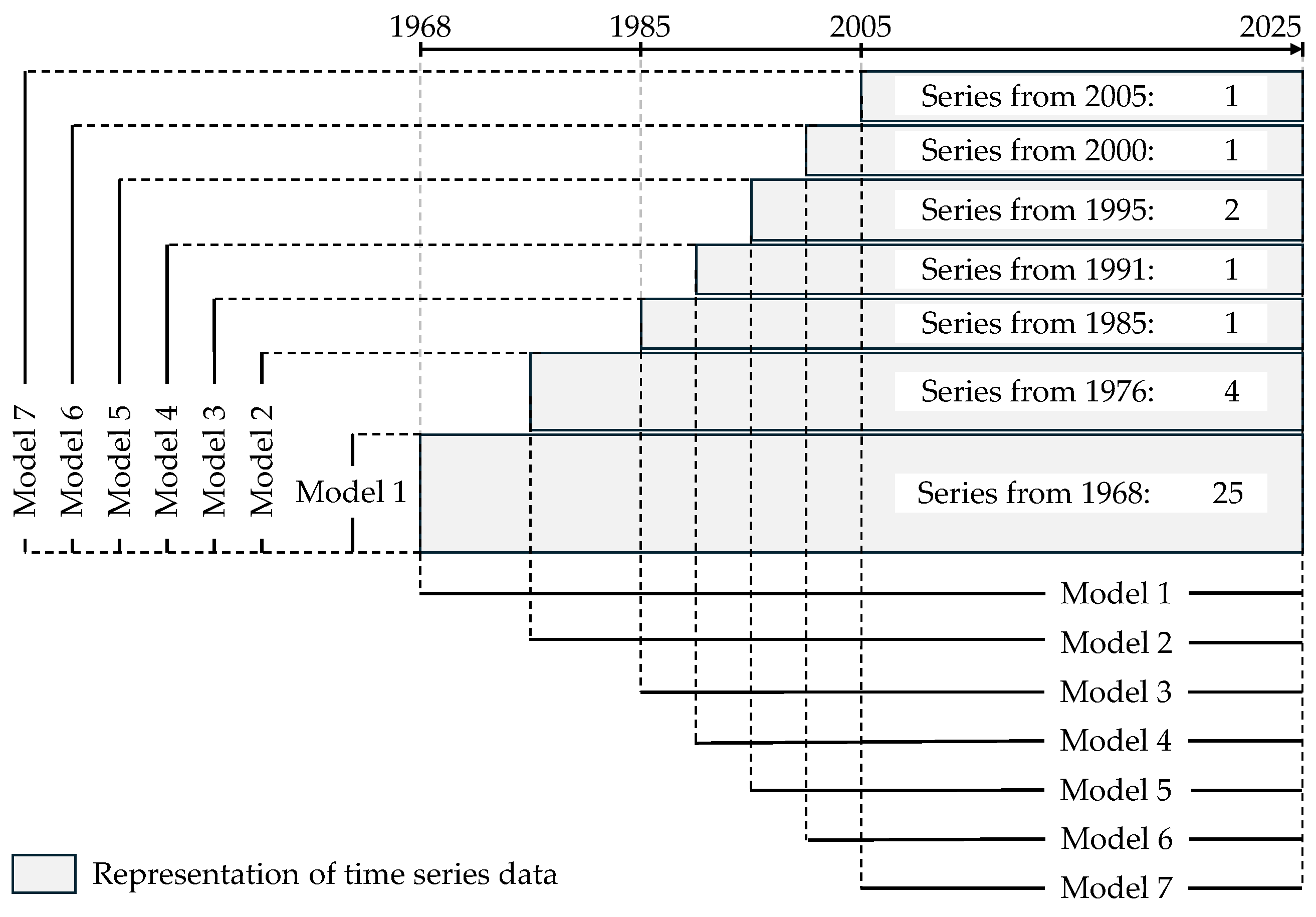

Table 1 documents that the constituent series begin at different dates. Because VARX models require a time-aligned sample, two competing strategies arise. One can (a) estimate on the longest horizon but restrict the cross-section to those indices observed throughout—maximizing the time dimension

T while reducing the cross-sectional dimension

N—or (b) retain the full set of indices and estimate only on the intersection period in which all series are available—maximizing

N but shortening

T; intermediate compromises are also possible. To sidestep this trade-off and exploit the maximum information available for each index, we adopt a model-vintage design: at every date on which additional indices become available, we estimate a separate VARX model on the longest contiguous window feasible at that vintage. This yields a sequence of models with expanding time spans and, when data permit, an enlarging cross-section. The procedure is illustrated in

Figure 4.

Building on this design, within each model vintage we estimate all six considered single-penalty specifications available in BigVAR—Lag, Own/Other, Sparse Lag, Sparse Own/Other, Basic, and Endogenous-First—across seven configuration settings, yielding

models. Due to the high dimensionality only lag orders

are considered. For each model, the regularization hyperparameter

is selected via rolling cross-validation. We first define a grid

of candidate penalty values. For every

, the model is re-estimated at each forecast origin

t on the validation window and

h-step-ahead forecasts are generated. Selection is based on the mean squared forecast error (MSFE):

The average is taken over all forecast origins

. Here,

denotes the last observation used for the initial estimation,

marks the end of the validation window,

h is the forecast horizon, and

denotes the Frobenius norm applied to the vector of forecast errors across series [

4].

3.3.3. Comparison of Prediction Accuracy of Both Employed Model Types

Using both modeling approaches, we generate

ex post out-of-sample forecasts for the last 20 available observations of all indices and compare accuracy by the mean absolute percentage error,

where

H denotes the evaluation horizon. MAPE is particularly suitable here because errors are computed on level data whose values are well away from zero; consequently, in our setting the measure does not suffer from the usual interpretational caveats [

41, chapter 3.4]. For the BigVAR class, the model selected for each series is the specification attaining the lowest forecast error.

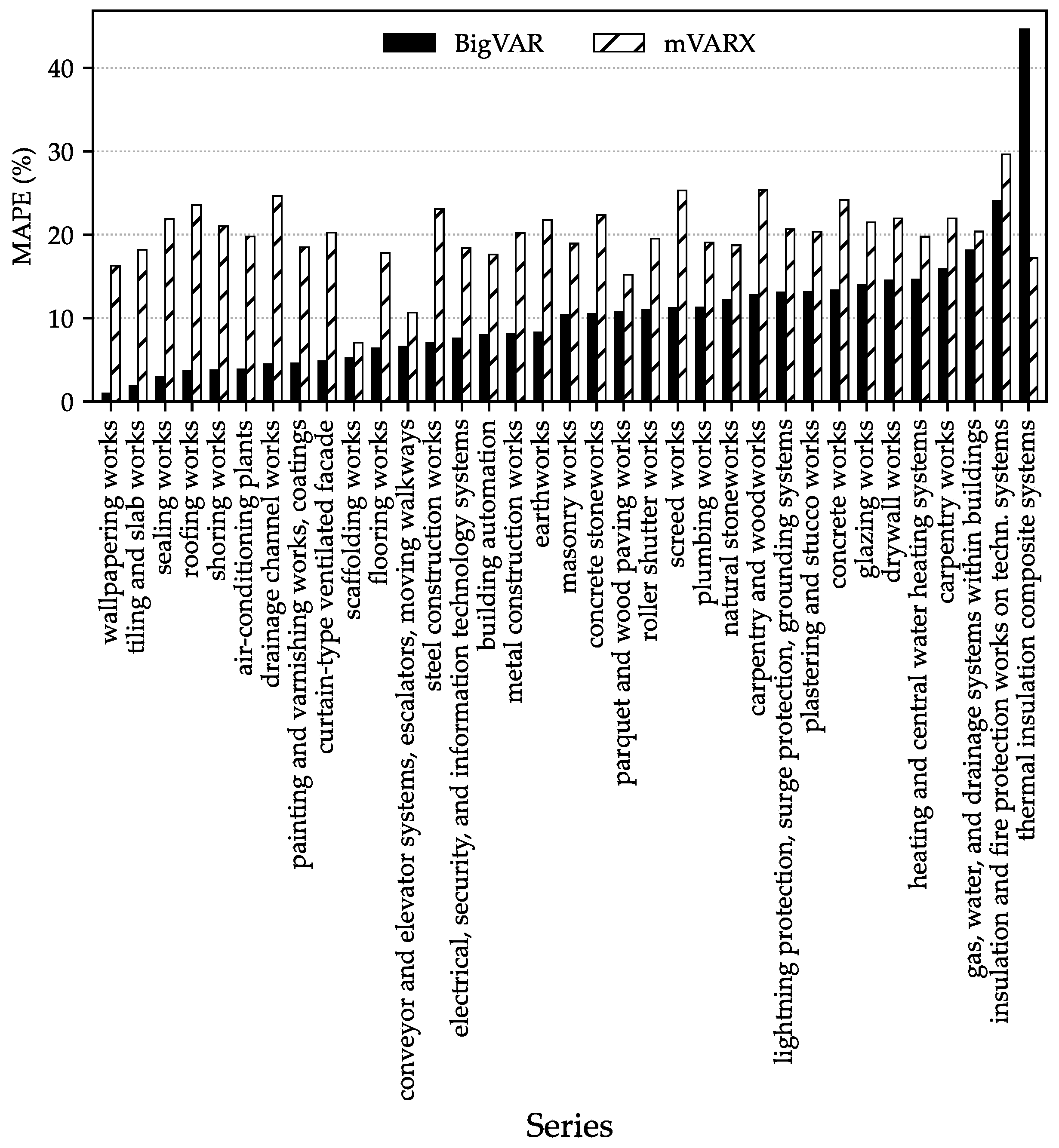

As shown in

Figure 5, the evidence on relative predictive performance is clear-cut: for 34 of the 35 series, regularized VARX (BigVAR) achieves a lower MAPE than the small VARX (mVARX) models. The best-performing BigVAR models and the corresponding error values are reported in

Table A1 in the

Appendix A.2, the exact error measures of mVARX models in

Table A2. Notably, the sole exception “thermal insulation composite systems” where mVARX outperforms BigVAR corresponds to the series with the shortest sample, beginning in 2005. Given the superior forecast accuracy of the BigVAR models, we employ, for ex ante out-of-sample projections, the best-performing BigVAR specification for each series.

3.3.4. Prediction of Price Indices

Finally, using the best-performing BigVAR specifications, we produce out-of-sample forecasts for all construction price indices over the one-year period immediately following the last available observation, obtained by iterating one-step-ahead predictions across the next four quarters. Scenario design is governed by the exogenous indicator of elevated price dynamics: in Scenario I (non-dynamic), the indicator remains zero throughout. In Scenario II (dynamic) it equals one in the first two quarters of the forecast horizon and zero thereafter. To quantify forecast uncertainty, we construct bootstrap-based prediction intervals. The near-term behavior of the indices under both scenarios is summarized in

Section 4.

4. Results

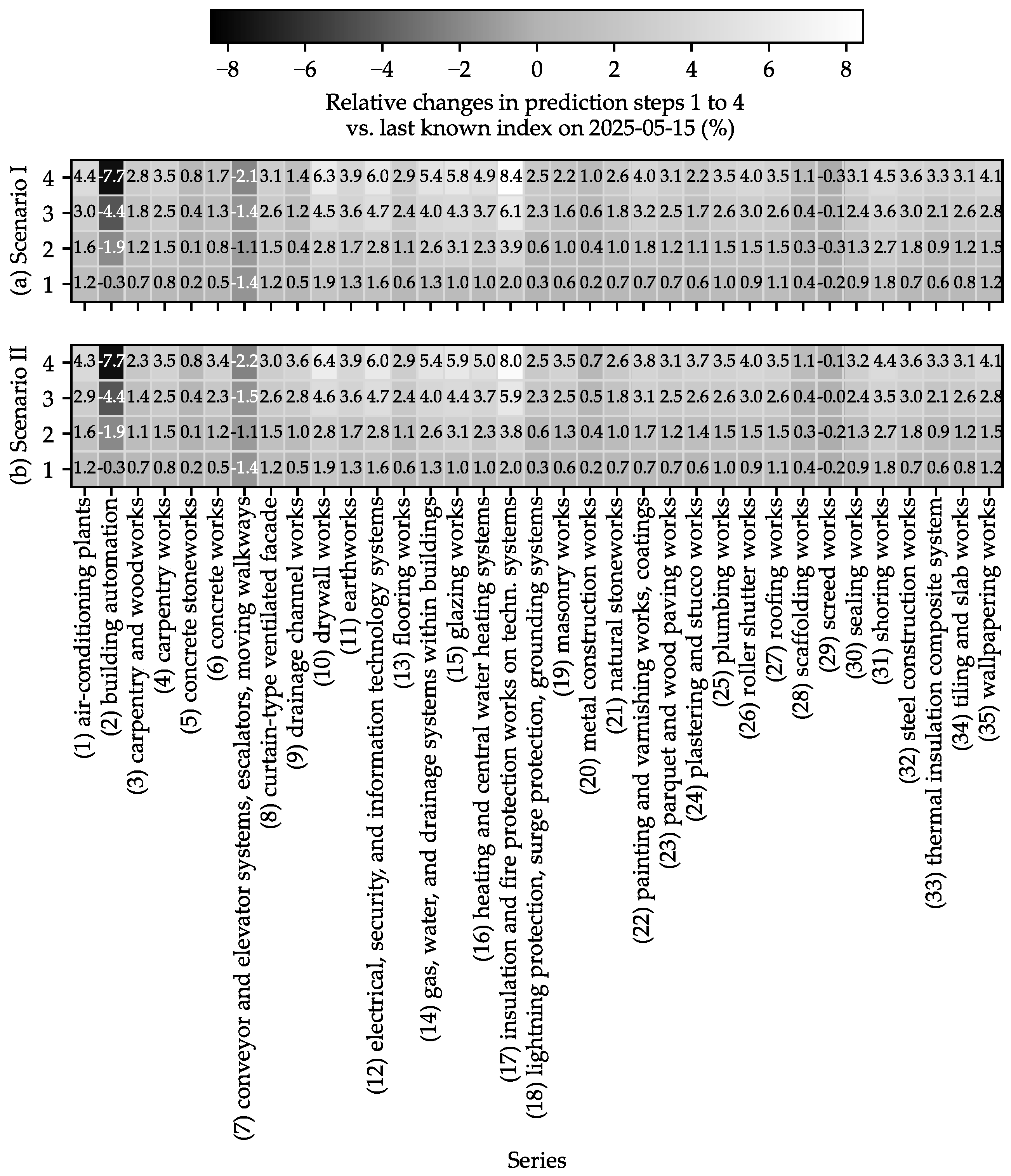

To visualize forecasts across the large set of target series, we employ a heat map.

Figure 6 compactly displays the evolution of all series over the four forecast steps under Scenarios I and II.

Shading intensity and, additionally, printed values encode the relative changes of each series at each forecast step with respect to the last available observation on 15 May 2025. The numbers prefixed to the series names on the x-axis are the Series IDs, which are referenced in subsequent figures.

Overall, the two scenarios yield very similar patterns, and most series exhibit increasingly positive changes as the horizon extends—i.e., construction works are expected to rise. Only three Series show declines over the forecasting horizon relative to the last observed value: “building automation” (S. I: , S. II: ), “conveyor and elevator systems, escalators, moving walkways” (S. I: , S. II: ) and “screed works” (S. I: , S. II: ). By contrast, the strongest relative increases—up to —are observed for “insulation and fire protection works on techn. systems” (S. I: , S. II: ), “drywall works” (S. I: , S. II: ), and “electrical, security, and information technology systems” (S. I: , S. II: ).

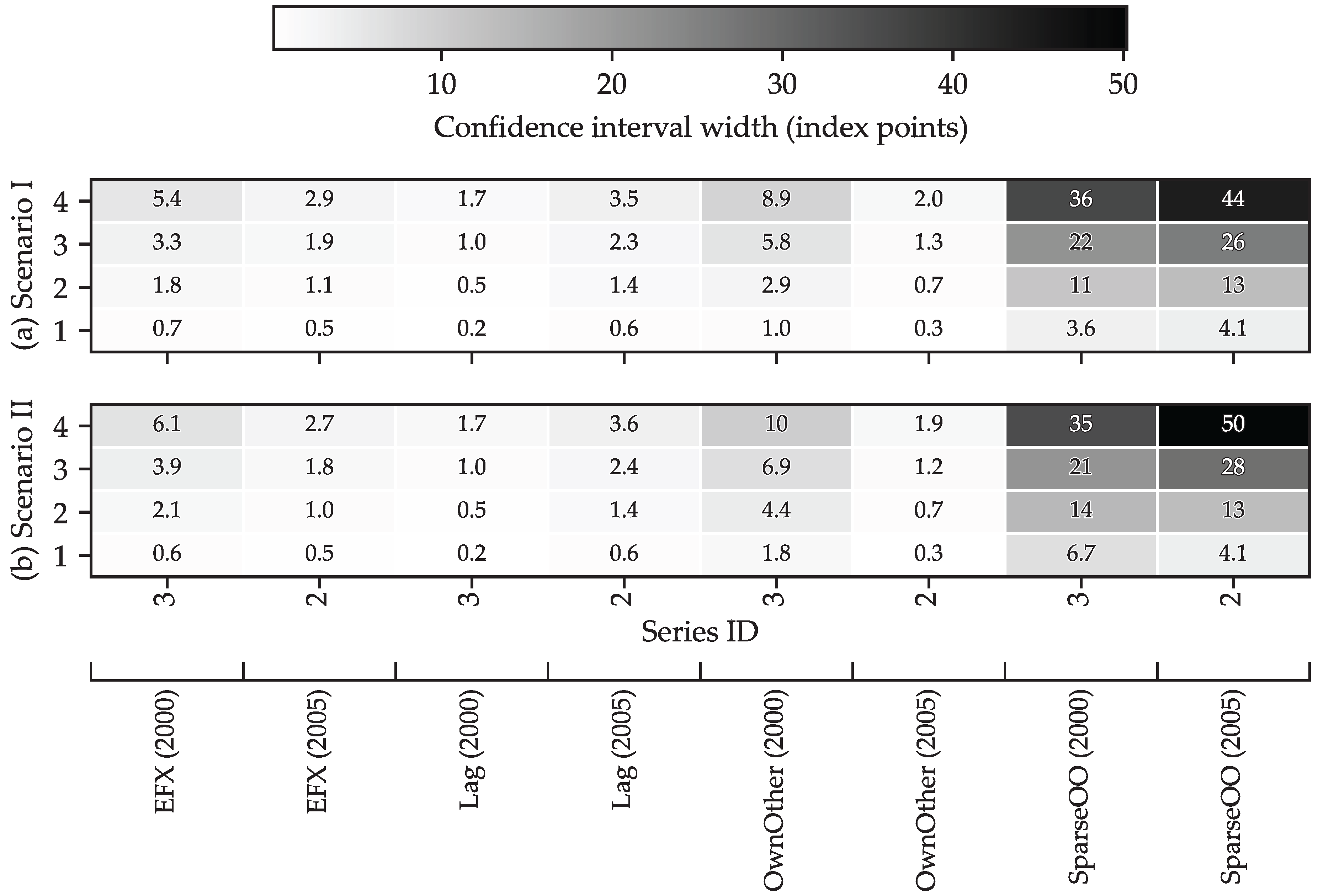

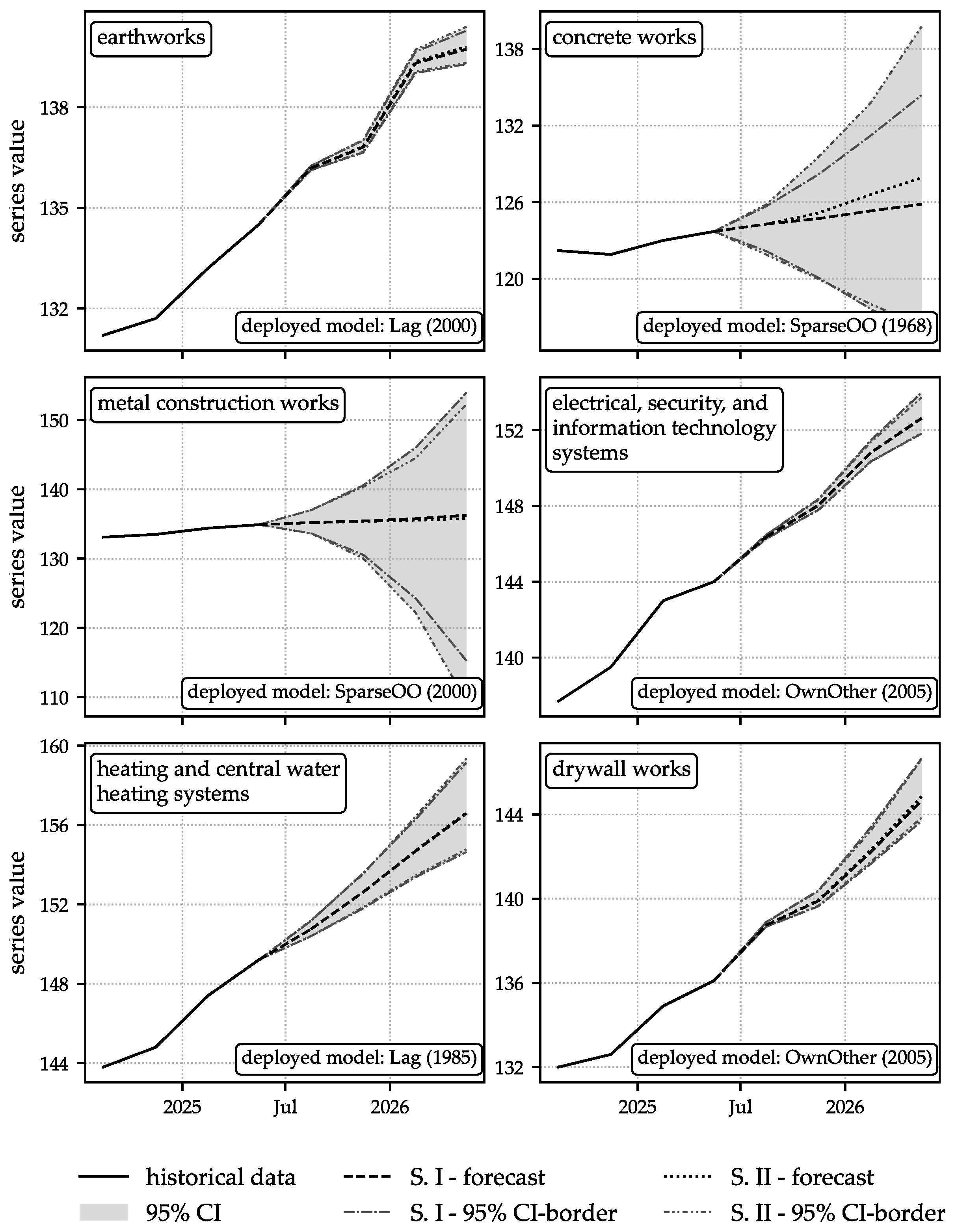

The projected paths of the six sub-indices that carry the largest weights in the aggregation to the top-level index are shown in greater detail in

Figure 7. These six series are “earthworks,” “concrete works,” “metal construction works,” “electrical, security, and information technology systems,” “heating and central water heating systems,” and “drywall works.” For each series, the figure reports the mean forecast together with the upper and lower bounds of the

confidence interval under both scenarios. Across “electrical, security, and information technology systems,” “heating and central water heating systems,” and “drywall works,” prices rise by roughly six index units over the horizon, with very similar trajectories in both scenarios. “earthworks” increases by about three index units, again with little difference between scenarios. For “metal construction works,” Scenario I exhibits an increase of approximately one index unit, whereas Scenario II grows by about 0.5 units; the confidence bands differ visually across scenarios, indicating modest differences in uncertainty. The largest scenario contrast occurs for “concrete works.” The mean forecast in Scenario I rises by roughly 1.5 units, while in Scenario II it increases by about four units, which suggests that the environment with elevated price dynamics has substantive effects for this trade. The corresponding confidence bounds shift accordingly. Overall, the widths of the

intervals vary markedly across series, indicating heterogeneous forecast uncertainty.

The extent to which the series’ trajectories differ between the two scenarios—which appear similar at first glance—is examined in detail in

Section 5. That section also discusses differences in the widths of the confidence intervals and analyzes the evolution of the aggregate index.

5. Discussion

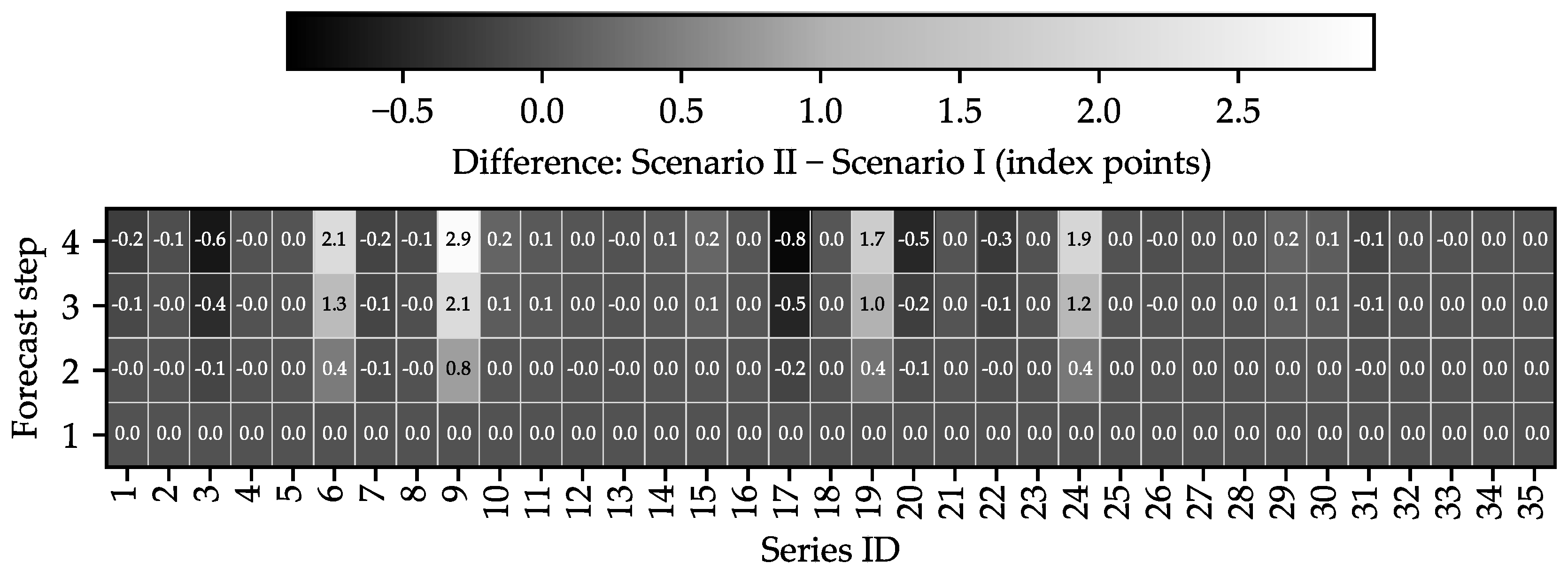

The similarity of many forecasted series across Scenario I (non-dynamic) and Scenario II (dynamic) is evident from the difference

D (Scenario II − Scenario I) shown in

Figure 8. In the final forecast step, only seven series display significant deviations (interpreted here as

): “drainage channel works” (Series ID: 9;

), “concrete works” (Series ID: 6;

), “plastering and stucco works” (Series ID: 24;

), and “masonry works” (Series ID: 19;

) are higher under Scenario II, whereas “insulation and fire protection works on technical systems” (Series ID: 17;

), “carpentry and woodworks” (Series ID: 3;

), and “metal construction works” (Series ID: 20;

) are higher under Scenario I.

By the end of the forecast horizon, seven series coincide exactly across scenarios; in fifteen cases the Scenario II forecasts exceed those of Scenario I, and in thirteen cases Scenario I is higher.

When the individual forecasts are aggregated to the composite CCI using the corresponding weights, the resulting trajectories are shown in

Figure 10. Both projected scenarios align well with the historical evolution of the index, with similarly increasing levels. As expected, the dynamic-price environment in Scenario II leads to higher index values, although the difference relative to Scenario I is not large.

Figure 8.

Illustration of absolute differences between scenario forecasts obtained by subtracting Scenario I from Scenario II (i.e., Scenario II − Scenario I). The mapping from Series IDs to series names is provided in

Figure 5.

Figure 8.

Illustration of absolute differences between scenario forecasts obtained by subtracting Scenario I from Scenario II (i.e., Scenario II − Scenario I). The mapping from Series IDs to series names is provided in

Figure 5.

Figure 9.

Representation of aggregated index trajectories, computed according to the official weighting scheme [

35], for both forecast scenarios.

Figure 9.

Representation of aggregated index trajectories, computed according to the official weighting scheme [

35], for both forecast scenarios.

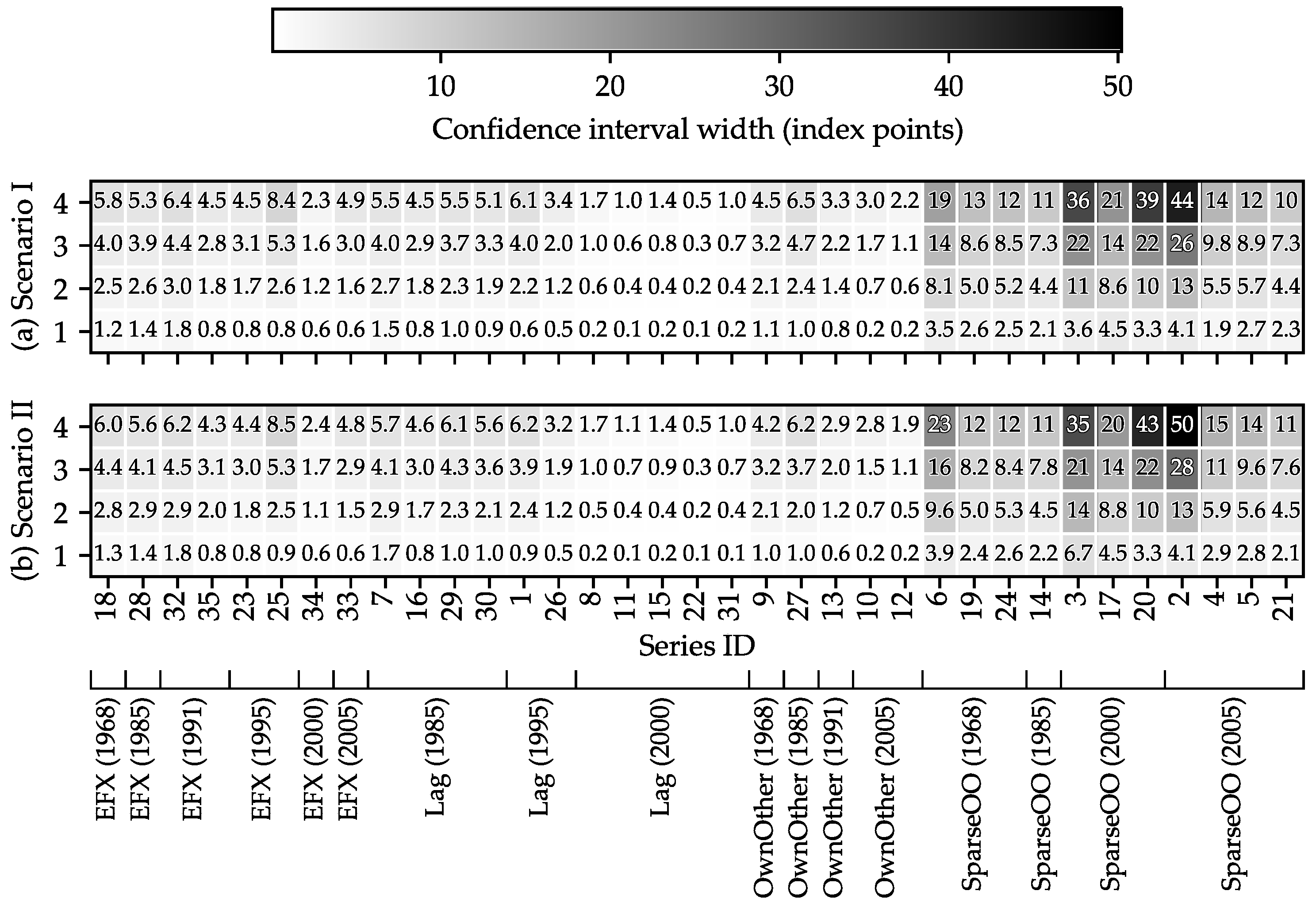

As already illustrated in

Figure 7, the forecast confidence intervals differ markedly across series. For completeness,

Figure 10 summarizes the widths of the confidence intervals for all series over the four forecast steps in both scenarios. The heat-map shading makes clear that interval widths—and thus forecast uncertainty—increase with the forecast horizon for virtually every series, in line with linear time-series theory, according to which the

h-step prediction-error variance grows as the sum of propagated innovation variances.

Figure 10.

Presentation of widths of the

confidence intervals for all forecasted series under Scenario I and Scenario II. The mapping from Series IDs to series names is provided in

Figure 5.

Figure 10.

Presentation of widths of the

confidence intervals for all forecasted series under Scenario I and Scenario II. The mapping from Series IDs to series names is provided in

Figure 5.

When the confidence-interval widths are ordered by the model used to generate the forecasts (see

Figure 11), a clear model dependence emerges: the 11 series forecast with SparseOO specifications exhibit the largest observed confidence-interval widths.

Figure A1 in

Appendix A.4 corroborates this result. Comparing the confidence interval widths for Series 2 (“building automation”) and Series 3 (“carpentry and woodworks”), the specifications selected by the minimum-MAPE criterion exhibit markedly wider intervals across the forecast horizon than those associated with alternative model types.

6. Conclusions

The study analyzes and forecasts 35 construction price indices for office buildings in Germany. With the exception of “building automation,” “conveyor and elevator systems, escalators, moving walkways,” and “screed works,” prices are projected to rise. Expected cost developments are quantified under two alternative assumptions for the first two post-sample periods: a dynamic price environment and a non-dynamic environment. Forecast uncertainty is summarized by confidence intervals, which reveal that uncertainty is model dependent. Model selection for forecasting is based on the minimum MAPE from an ex post out-of-sample evaluation. Notably, when uncertainty considerations are incorporated into the selection criterion, the preferred models may differ from those chosen solely by the MAPE metric.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and K.N.; methodology, M.P.; formal analysis, M.P.; investigation, M.P.; data curation, M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, K.N.; visualization, M.P.; supervision, K.N.; project administration, K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [ChatGPT, GPT-4o] for the purposes of coding details, as well as [DeepL] for translation and text editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADF |

Augmented Dickey-Fuller |

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| ANN |

Artificial neural network |

| ARFIMA |

Autoregressive fractionally integrated moving average |

| ARIMA |

Autoregressive integrated moving average |

| ARMA |

Autoregressive moving average |

| CCI |

Construction cost index |

| CPI |

Consumer price index |

| ENR |

Engineering News-Record |

| GDP |

Gross domestic product |

| k-NN |

k-nearest neighbors |

| LSTM |

Long short-term memory |

| MAE |

Mean absolute error |

| MAPE |

Mean absolute percentage error |

| MSE |

Mean squared error |

| MSFE |

Mean squared forecast error |

| NN |

Neural network |

| PERT |

Perfect random tree ensembles |

| PFSD |

Prediction based on fuzzy similarity distribution |

| PPI |

Producer price index |

| RMSE |

Root mean square error |

| SARIMA |

Seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average |

| SMA |

Simple moving average |

| SVM |

Support vector machine |

| VAR |

Vector autoregression |

| VARX |

Vector autoregressive models with exogenous variables |

| VEC |

Vector error correction |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Search String for the Literature Research

The following search string was used for the literature research in the Scopus database:

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( construction OR building ) AND "cost index"

AND ( forecast* OR predict* ) ) AND PUBYEAR > 2004

AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "ar" ) )

AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , "English" )

OR LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , "German" ) )

Appendix A.2. Model Comparison in ex Post Out-of-Sample Prediction

Table A1.

Selected regularized VARX models (BigVAR) for each series and corresponding ex post out-of-sample forecast errors (MAPE, RMSE) over the last 20 observations.

Table A1.

Selected regularized VARX models (BigVAR) for each series and corresponding ex post out-of-sample forecast errors (MAPE, RMSE) over the last 20 observations.

| Series |

BigVAR Model |

MAPE |

RMSE |

| air-conditioning plants |

Lag (1995) |

3.83 |

8.25 |

| building automation |

SparseOO (2005) |

7.96 |

12.29 |

| carpentry and woodworks |

SparseOO (2000) |

12.78 |

17.43 |

| carpentry works |

SparseOO (2005) |

15.87 |

23.70 |

| concrete stoneworks |

SparseOO (2005) |

10.47 |

15.46 |

| concrete works |

SparseOO (1968) |

13.35 |

17.97 |

| conveyor and elevator systems, escalators, moving walkways |

Lag (1985) |

6.58 |

10.88 |

| curtain-type ventilated facade |

Lag (2000) |

4.79 |

11.64 |

| drainage channel works |

OwnOther (1968) |

4.45 |

5.92 |

| drywall works |

OwnOther (2005) |

14.53 |

21.46 |

| earthworks |

Lag (2000) |

8.28 |

11.12 |

| electrical, security, and information technology systems |

OwnOther (2005) |

7.55 |

12.54 |

| flooring works |

OwnOther (1991) |

6.35 |

8.89 |

| gas, water, and drainage systems within buildings |

SparseOO (1985) |

18.13 |

28.92 |

| glazing works |

Lag (2000) |

13.99 |

23.66 |

| heating and central water heating systems |

Lag (1985) |

14.60 |

25.42 |

| insulation and fire protection works on techn. systems |

SparseOO (2000) |

24.05 |

44.37 |

| lightning protection, surge protection, grounding systems |

EFX (1968) |

13.07 |

19.36 |

| masonry works |

SparseOO (1968) |

10.39 |

13.97 |

| metal construction works |

SparseOO (2000) |

8.10 |

13.70 |

| natural stoneworks |

SparseOO (2005) |

12.19 |

17.23 |

| painting and varnishing works, coatings |

Lag (2000) |

4.54 |

8.50 |

| parquet and wood paving works |

EFX (1995) |

10.72 |

15.14 |

| plastering and stucco works |

SparseOO (1968) |

13.12 |

18.04 |

| plumbing works |

EFX (1995) |

11.28 |

22.10 |

| roller shutter works |

Lag (1995) |

10.94 |

16.75 |

| roofing works |

OwnOther (1985) |

3.62 |

5.04 |

| scaffolding works |

EFX (1985) |

5.19 |

7.79 |

| screed works |

Lag (1985) |

11.21 |

17.92 |

| sealing works |

Lag (1985) |

2.97 |

4.73 |

| shoring works |

Lag (2000) |

3.71 |

5.76 |

| steel construction works |

EFX (1991) |

7.02 |

10.29 |

| thermal insulation composite systems |

EFX (2005) |

44.64 |

98.62 |

| tiling and slab works |

EFX (2000) |

1.86 |

2.63 |

| wallpapering works |

EFX (1991) |

0.92 |

1.38 |

Table A2.

Ex post out-of-sample forecast (last 20 observations) evaluation (MAPE, RMSE) of small VARX models models with macro variables (mVARX).

Table A2.

Ex post out-of-sample forecast (last 20 observations) evaluation (MAPE, RMSE) of small VARX models models with macro variables (mVARX).

| Series |

MAPE |

RMSE |

| air-conditioning plants |

19.80 |

29.65 |

| building automation |

17.60 |

27.01 |

| carpentry and woodworks |

25.38 |

30.95 |

| carpentry works |

21.93 |

32.43 |

| concrete stoneworks |

22.34 |

32.33 |

| concrete works |

24.16 |

31.24 |

| conveyor and elevator systems, escalators, moving walkways |

10.64 |

15.14 |

| curtain-type ventilated facade |

20.26 |

29.81 |

| drainage channel works |

24.66 |

34.91 |

| drywall works |

21.97 |

30.66 |

| earthworks |

21.75 |

30.54 |

| electrical, security, and information technology systems |

18.38 |

27.96 |

| flooring works |

17.80 |

25.60 |

| gas, water, and drainage systems within buildings |

20.38 |

31.87 |

| glazing works |

21.50 |

31.89 |

| heating and central water heating systems |

19.76 |

31.37 |

| insulation and fire protection works on techn. systems |

29.62 |

54.75 |

| lightning protection, surge protection, grounding systems |

20.67 |

31.28 |

| masonry works |

18.93 |

25.46 |

| metal construction works |

20.20 |

29.11 |

| natural stoneworks |

18.73 |

26.36 |

| painting and varnishing works, coatings |

18.49 |

26.26 |

| parquet and wood paving works |

15.19 |

21.88 |

| plastering and stucco works |

20.37 |

28.23 |

| plumbing works |

19.06 |

27.37 |

| roller shutter works |

19.51 |

28.59 |

| roofing works |

23.58 |

34.14 |

| scaffolding works |

7.03 |

9.13 |

| screed works |

25.30 |

36.38 |

| sealing works |

21.89 |

30.86 |

| shoring works |

21.02 |

28.76 |

| steel construction works |

23.07 |

31.18 |

| thermal insulation composite systems |

17.20 |

25.03 |

| tiling and slab works |

18.20 |

24.91 |

| wallpapering works |

16.26 |

22.98 |

Appendix A.3. Ex ante Out-of-Sample Predictions with BigVAR Models

Table A3.

Scenario I: projected values for each series (Q3 2025–Q2 2026).

Table A3.

Scenario I: projected values for each series (Q3 2025–Q2 2026).

| Series |

Q3 2025 |

Q4 2025 |

Q1 2026 |

Q2 2026 |

| air-conditioning plants |

143.23 |

143.79 |

145.74 |

147.76 |

| building automation |

147.47 |

145.08 |

141.45 |

136.56 |

| carpentry and woodworks |

122.61 |

123.23 |

123.94 |

125.18 |

| carpentry works |

140.80 |

141.81 |

143.15 |

144.55 |

| concrete stoneworks |

135.22 |

135.16 |

135.53 |

136.02 |

| concrete works |

124.28 |

124.71 |

125.32 |

125.84 |

| conveyor and elevator systems, escalators, moving walkways |

118.07 |

118.51 |

118.17 |

117.30 |

| curtain-type ventilated facade |

142.98 |

143.36 |

144.98 |

145.67 |

| drainage channel works |

135.94 |

135.87 |

136.96 |

137.25 |

| drywall works |

138.74 |

139.90 |

142.22 |

144.66 |

| earthworks |

136.18 |

136.81 |

139.32 |

139.73 |

| electrical, security, and information technology systems |

146.37 |

148.04 |

150.82 |

152.62 |

| flooring works |

132.80 |

133.44 |

135.20 |

135.88 |

| gas, water, and drainage systems within buildings |

150.97 |

152.85 |

154.94 |

157.06 |

| glazing works |

142.72 |

145.67 |

147.37 |

149.43 |

| heating and central water heating systems |

150.75 |

152.62 |

154.69 |

156.58 |

| insulation and fire protection works on techn. systems |

181.36 |

184.70 |

188.71 |

192.79 |

| lightning protection, surge protection, grounding systems |

140.45 |

140.78 |

143.17 |

143.48 |

| masonry works |

126.41 |

126.99 |

127.75 |

128.42 |

| metal construction works |

135.20 |

135.43 |

135.77 |

136.26 |

| natural stoneworks |

131.97 |

132.44 |

133.48 |

134.45 |

| painting and varnishing works, coatings |

131.55 |

132.89 |

134.80 |

135.78 |

| parquet and wood paving works |

129.63 |

130.30 |

131.86 |

132.65 |

| plastering and stucco works |

130.36 |

130.97 |

131.74 |

132.42 |

| plumbing works |

139.09 |

139.73 |

141.30 |

142.47 |

| roller shutter works |

136.64 |

137.41 |

139.49 |

140.86 |

| roofing works |

141.48 |

141.98 |

143.54 |

144.80 |

| scaffolding works |

120.84 |

120.76 |

120.85 |

121.70 |

| screed works |

135.79 |

135.66 |

135.86 |

135.64 |

| sealing works |

133.88 |

134.39 |

135.86 |

136.84 |

| shoring works |

133.81 |

135.02 |

136.23 |

137.48 |

| steel construction works |

124.54 |

125.98 |

127.40 |

128.10 |

| thermal insulation composite system |

136.98 |

137.47 |

139.06 |

140.64 |

| tiling and slab works |

128.38 |

128.89 |

130.73 |

131.38 |

| wallpapering works |

130.69 |

131.17 |

132.82 |

134.45 |

Table A4.

Scenario II: projected values for each series (Q3 2025–Q2 2026).

Table A4.

Scenario II: projected values for each series (Q3 2025–Q2 2026).

| Series |

Q3 2025 |

Q4 2025 |

Q1 2026 |

Q2 2026 |

| air-conditioning plants |

143.23 |

143.76 |

145.63 |

147.53 |

| building automation |

147.47 |

145.07 |

141.42 |

136.51 |

| carpentry and woodworks |

122.61 |

123.09 |

123.52 |

124.54 |

| carpentry works |

140.80 |

141.81 |

143.15 |

144.55 |

| concrete stoneworks |

135.22 |

135.16 |

135.54 |

136.02 |

| concrete works |

124.28 |

125.15 |

126.60 |

127.91 |

| conveyor and elevator systems, escalators, moving walkways |

118.07 |

118.44 |

118.03 |

117.15 |

| curtain-type ventilated facade |

142.98 |

143.35 |

144.95 |

145.58 |

| drainage channel works |

135.94 |

136.69 |

139.04 |

140.13 |

| drywall works |

138.74 |

139.92 |

142.31 |

144.85 |

| earthworks |

136.18 |

136.83 |

139.37 |

139.80 |

| electrical, security, and information technology systems |

146.37 |

148.03 |

150.82 |

152.65 |

| flooring works |

132.80 |

133.44 |

135.20 |

135.88 |

| gas, water, and drainage systems within buildings |

150.97 |

152.86 |

154.97 |

157.11 |

| glazing works |

142.72 |

145.70 |

147.47 |

149.64 |

| heating and central water heating systems |

150.75 |

152.62 |

154.71 |

156.62 |

| insulation and fire protection works on techn. systems |

181.36 |

184.53 |

188.22 |

191.98 |

| lightning protection, surge protection, grounding systems |

140.45 |

140.78 |

143.19 |

143.51 |

| masonry works |

126.41 |

127.34 |

128.80 |

130.12 |

| metal construction works |

135.20 |

135.37 |

135.55 |

135.79 |

| natural stoneworks |

131.97 |

132.44 |

133.49 |

134.46 |

| painting and varnishing works, coatings |

131.55 |

132.85 |

134.66 |

135.51 |

| parquet and wood paving works |

129.63 |

130.30 |

131.86 |

132.65 |

| plastering and stucco works |

130.36 |

131.37 |

132.93 |

134.36 |

| plumbing works |

139.09 |

139.73 |

141.30 |

142.47 |

| roller shutter works |

136.64 |

137.42 |

139.48 |

140.83 |

| roofing works |

141.48 |

141.98 |

143.54 |

144.80 |

| scaffolding works |

120.84 |

120.76 |

120.85 |

121.70 |

| screed works |

135.79 |

135.69 |

135.97 |

135.82 |

| sealing works |

133.88 |

134.42 |

135.93 |

136.95 |

| shoring works |

133.81 |

134.99 |

136.16 |

137.34 |

| steel construction works |

124.54 |

125.98 |

127.40 |

128.10 |

| thermal insulation composite system |

136.98 |

137.47 |

139.06 |

140.64 |

| tiling and slab works |

128.38 |

128.89 |

130.73 |

131.38 |

| wallpapering works |

130.69 |

131.17 |

132.82 |

134.45 |

Appendix A.4. Confidence interval Widths of Different Forecast Models

Figure A1.

Illustration of the forecast confidence intervals widths across alternative model specifications for “carpentry and woodworks” (Series ID: 3) and “building automation” (Series ID: 2).

Figure A1.

Illustration of the forecast confidence intervals widths across alternative model specifications for “carpentry and woodworks” (Series ID: 3) and “building automation” (Series ID: 2).

References

- Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt). Number of building permits for new office and administration buildings in Germany from 1991 to 2024. In: Statista. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/257674/umfrage/baugenehmigungen-fuer-buero-und-verwaltungsgebaeude-in-deutschland/ (Accessed on August 7, 2025).

- Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt). Number of residential and non-residential building completions in Germany from 2002 to 2024 (in 1,000). In: Statista. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/70370/umfrage/baufertigstellungen-wohngebaeude-und-nichtwohngebaeude-seit-1998/ (Accessed on August 7, 2025).

- German Construction Industry Association (Hauptverband der Deutschen Bauindustrie). Number of insolvencies in the construction industry in Germany between 1995 and 2023 (per 10,000 companies). In: Statista. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/152510/umfrage/bau-insolvenzhaeufigkeit-im-branchenvergleich-in-deutschland-seit-1995/ (Accessed on August 7, 2025).

- Nicholson, W. B.; Matteson, D. S.; Bien, J. VARX-L: Structured Regularization for Large Vector Autoregressions with Exogenous Variables. Int. J. Forecast. 2017, 33, 627–651. [CrossRef]

- Ashuri, B.; Lu, J. Time Series Analysis of ENR Construction Cost Index. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2010, 136, 1227–1237. [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.; Shin, D. H. Forecasting Construction Cost Index Using Interrupted Time-Series. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2018, 22, 1626–1633. [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Chi, S.; Kim, D. Y. Predicting Construction Cost Index Using the Autoregressive Fractionally Integrated Moving Average Model. Journal of Management in Engineering 2018, 34, 04017063. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Mbachu, J.; Zhang, H. Forecasting Residential Building Costs in New Zealand Using a Univariate Approach. International Journal of Engineering Business Management 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Shahandashti, S. M.; Ashuri, B. Forecasting Engineering News-Record Construction Cost Index Using Multivariate Time Series Models. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2013, 139, 1237–1243. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Moon, S. Stochastic Forecast of Construction Cost Index Using a Cointegrated Vector Autoregression Model. Journal of Management in Engineering 2013, 29, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.; Shin, D. H. Forecasting Model of Construction Cost Index Based on VECM with Search Query. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2018, 22, 2726–2734. [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.-Y.; Ryu, K.R.; Shahandashti, M. Predicting City-Level Construction Cost Index Using Linear Forecasting Models. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management. 2021, 147, 04020158. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ashuri, B. Predicting ENR Construction Cost Index Using Machine-Learning Algorithms. International Journal of Construction Education and Research 2016, 13, 47–63. [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Chen, Y.; Guan, G. Cost Index Predictions for Construction Engineering Based on LSTM Neural Networks. Advances in Civil Engineering 2020, 2020, 6518147. [CrossRef]

- Al Kailani, H.; Sweis, G. J.; Sammour, F.; Maaitah, W. O.; Sweis, R. J.; Alkailani, M. Predicting Construction Cost Index Using Fuzzy Logic and Machine Learning in Jordan. Construction Innovation: Information, Process, Management 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ashuri, B.; Deng, Y. A Novel Method for Forecasting Time Series Based on Fuzzy Logic and Visibility Graph. Advances in Data Analysis and Classification 2017, 11, 759–783. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ashuri, B.; Shyr, Y.; Deng, Y. Forecasting Construction Cost Index Based on Visibility Graph: A Network Approach. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Application 2018, 493, 239–252. [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Xiao, F. A Novel Method for Forecasting Construction Cost Index Based on Complex Network. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2019, 527, 121306. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xiao, F. A Novel Method for Forecasting Time Series Based on Directed Visibility Graph and Improved Random Walk. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 2022, 594, 127029. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xiao, F. An Efficient Forecasting Method for Time Series Based on Visibility Graph and Multi-Subgraph Similarity. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2022, 160, 112243. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xiao, F. Network Self Attention for Forecasting Time Series. Applied Soft Computing 2022, 124, 109092. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xiao, F. Time-Series Forecasting Based on Fuzzy Cognitive Visibility Graph and Weighted Multisubgraph Similarity. IEEE Transactions Fuzzy Systems 2023, 31, 1281–1293. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Xiao, F. A Novel Weighted Approach for Time Series Forecasting Based on Visibility Graph. Pattern Recognition 2024, 155, 110720. [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.-T.; Cheng, M.-Y.; Wu, Y.-W. Hybrid Computational Model for Forecasting Taiwan Construction Cost Index. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2015, 141, 04014089. [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Fang, J. Prediction of Construction Cost Index Based on Multi Variable Grey Neural Network Model. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Change Manag. 2018, 10, 209–226. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Mbachu, J.; Liu, Z. Modelling Residential Building Costs in New Zealand: A Time-Series Transfer Function Approach. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2020, 2020, 7028049. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, C.-Y.; Shahandashti, M.; Ryu, K. R. Improving Accuracy in Predicting City-Level Construction Cost Indices by Combining Linear ARIMA and Nonlinear ANNs. Journal of Management in Engineering 2022, 38, 04021093. [CrossRef]

- Myrvang, R.; Liu, C.-Y. A. Beyond Traditional Methods: Enhancing Cost Escalation Forecasting in Commercial Construction amid Economic Turbulence. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2025, 151, 04024201. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S. Dynamic Regression Models for Prediction of Construction Costs. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2009, 135, 360–367. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S. Time Series Models for Forecasting Construction Costs Using Time Series Indexes. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2011, 137, 656–662. [CrossRef]

- Elfahham, Yasser. Estimation and Prediction of Construction Cost Index Using Neural Networks, Time Series, and Regression. Alex. Eng. J. 2019, 58, 499–506. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Maqsoom, A.; Inam, H.; Basharat, M. U.; Ullah, F. Forecasting Construction Cost Index through Artificial Intelligence. Societies 2023, 13, 219. [CrossRef]

- Aydinli, S. Impact of Unexpected Conditions on Construction Cost Forecasting Performance: Evidence from Europe. Construction Management Economics 2024, 42, 787–801. [CrossRef]

- Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt). Construction price indices for buildings in Germany (GENESIS-Online Database, Table 61261-0002). Available online: https://www-genesis.destatis.de/datenbank/online/statistic/61261/table/61261-0002/search/s/YmF1cHJlaXNpbmRpemVz (Accessed on August 7, 2025).

- Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt). Construction Price Indices – Weighting Schemes 2021. Statistical Report, published on July 10, 2024. Wiesbaden, Germany, 2024. Available online: https://www.destatis.de (Accessed on September 22, 2025).

- Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt). Qualitätsbericht: Preisindizes für die Bauwirtschaft – Statistik der Bauleistungspreise; Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Methoden/Qualitaetsberichte/Preise/qualitaetsbericht-bauleistungspreise.pdf (accessed on August 7, 2025).

- Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt). Volkswirtschaftliche Gesamtrechnungen. Bruttoinlandsprodukt, nominal, preisbereinigt, saison- und kalenderbereinigt (Tabelle 81000-118; Quartale). Statistischer Bericht, Artikelnummer 2180120253225. Wiesbaden, Deutschland, 2025. Available online: https://www.destatis.de (Accessed on August 22, 2025).

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Consumer Price Indices (CPIs, HICPs), COICOP 1999: Consumer Price Index: Total for Germany [CPALTT01DEM659N], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPALTT01DEM659N (Accessed on September 10, 2025).

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Interest Rates: 3-Month or 90-Day Rates and Yields: Interbank Rates: Total for Germany [IR3TIB01DEM156N], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IR3TIB01DEM156N (Accessed on September 10, 2025).

- Aggarwal, C. C. Outlier Analysis, (2nd ed.); Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. ISBN 978-3-319-47578-3.

- Hyndman, R. J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://otexts.com/fpp3/ (accessed on September 9, 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).