1. Introduction

Hypertension, defined as blood pressure of 130 mmHg or higher and/or a diastolic blood pressure of 80 mmHg or higher, is a major global health challenge and leading risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and kidney failure [

1,

2,

3]. In 2019, over 1.2 billion people worldwide were affected, with prevalence exceeding 50% in some regions [

2]. Despite its silent clinical course, hypertension contributes to over 8 million deaths annually [

3]. Risk factors include age, genetics, obesity, inactivity, and unhealthy diet [

1]. While treatment options exist, improved prevention and personalized therapies remain essential.

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) regulates blood pressure and fluid balance. Renin release from the kidney cleaves angiotensinogen to angiotensin I, which is converted by the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) into angiotensin II [

4]. Angiotensin II raises blood pressure via vasoconstriction, stimulation of aldosterone and vasopressin release, enhanced sodium reabsorption, and increased sympathetic tone [

5]. Dysregulation of the RAAS underlies hypertension, heart failure, and kidney disease.

Pharmacological treatments target RAAS at multiple points. Beta-blockers lower renin, direct renin inhibitors (e.g., aliskiren) block its activity, ACE inhibitors (e.g., ramipril) prevent angiotensin II formation, and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) (e.g., losartan) selectively antagonize AT1 receptors [

5,

6,

7,

8]. ARBs offer high specificity by blocking receptor-mediated effects of angiotensin II without interfering with its synthesis. Other antihypertensive drug classes include diuretics and calcium channel blockers [

9,

10].

Losartan, the first ARB approved in 1995, is widely prescribed for hypertension and related complications [

11,

12]. By competitively blocking AT1 receptors, it reduces vasoconstriction, aldosterone secretion, and water retention. Its major active metabolite, E3174, is generate through CYP2C9 mediated conversion and 10–40 times more potent [

13], though losartan itself remains an effective antagonist. Both compounds contribute to clinical efficacy. Losartan is well tolerated, with dizziness and mild respiratory symptoms as the most common side effects [

12]. It is available as monotherapy or combined with hydrochlorothiazide for greater blood pressure reduction [

14]. Standard dosing ranges from 25–100 mg/day. Like other ARBs, it is contraindicated in pregnancy [

11].

Losartan shows rapid oral absorption, with peak plasma levels after 1–2 h and bioavailability of about 33% due to first-pass metabolism [

13,

15]. E3174 peaks later (3–4 h) and has 4–8-fold higher systemic exposure [

13,

16]. Both compounds bind strongly to plasma proteins and are eliminated via hepatic metabolism and renal/fecal excretion, with terminal half-lives of 2 h (losartan) and 4–6 h (E3174) [

17,

18]. Only small fractions are excreted unchanged renally [

19]. Minor metabolites such as L158 reflect additional metabolic pathways [

18,

20].

Pharmacodynamically, losartan lowers blood pressure by blocking AT1 receptors, thereby reducing aldosterone secretion [

21,

22,

23]. AT1 blockade also increases renin and angiotensin levels due to loss of feedback control [

24,

25]. Enhanced stimulation of AT2 receptors may further contribute to vasodilation [

26].

Liver cirrhosis reduces losartan clearance by about 50% and doubles bioavailability, leading to higher plasma levels, though E3174 exposure increases only modestly [

11,

27]. Renal impairment decreases clearance of losartan and E3174 but generally does not elevate E3174 levels due to compensatory mechanisms [

19,

28,

29]. Neither compound is dialyzable, and dose adjustments are mainly required in hepatic dysfunction [

30].

Drug response varies due to genetic polymorphisms in ABCB1 and CYP2C9 genes. Variants of ABCB1, a gene encoding for a drug efflux transporter also known as P-glycoprotein or MDR1, influence losartan absorption and blood pressure response, though findings are inconsistent [

31,

32,

33]. CYP2C9 polymorphisms (*2, *3, *13) reduce metabolism to E3174, increasing losartan exposure and diminishing therapeutic effect [

13,

34,

35,

36,

37]. The frequency of these alleles varies by population [

38,

39,

40].

Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic/ pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) models integrate ADME processes (absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination) with drug effects using differential equations [

41]. They allow simulation of dosing regimens, organ dysfunction, and genetic variability on drug behavior. In this work, a PBPK/PD model of losartan was developed to investigate dose-dependent PK/PD effects, the influence of hepatic and renal impairment and the impact of ABCB1 and CYP2C9 variants. The aim is to clarify sources of variability in losartan response and support individualized therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Research

A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed and PKPDAI [

42] on 27 August 2024 using the terms

losartan AND pharmacokinetics. Eligible studies included human clinical trials with PK/PD data in healthy volunteers, hepatic/renal impairment, or CYP2C9 genotypes. Excluded were animal studies, pediatric/ single-patient reports, reviews, computational models, cocktail or combination designs, and PD-only studies. Where data were redundant, representative studies were selected. Additional

in vitro reports were included to derive kinetic parameters.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search and study selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search and study selection process.

2.2. Data Curation

Relevant study data were curated into PK-DB [

43]. Extracted metadata included group and individual characteristics (age, sex, genotype, comorbidities), interventions (dose, route, regimen), and outcomes (concentration-time profiles of losartan and metabolites, RAAS biomarkers, blood pressure, heart rate). Digitization of graphical data was performed using WebPlotDigitizer [

44]. Data were organized according to PK-DB standards into groups, individuals, interventions, and time courses, providing the heterogeneous dataset used for modeling and validation.

2.3. Computational Model

A physiologically-based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) model was built in the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) [

45,

46] using sbmlutils [

47], visualized using cysbml [

48], simulated with sbmlsim [

49] based on libroadrunner [

50,

51], and shared under CC-BY 4.0 at Zenodo (v0.7.1) [

52]. The model consists of submodels for intestine, liver, kidney, and RAAS, connected by systemic circulation. Hepatic impairment was implemented as progressive cirrhosis [

53,

54], aligned with Child-Pugh classes [

55,

56]. Renal impairment was modeled as reduced clearance based on glomerular filtration rate following KDIGO guidelines [

57,

58]. CYP2C9 genetic variability was incorporated using allele-specific activity scaling [

59,

60,

61], and ABCB1 activity was adjusted according to published polymorphism data [

62,

63].

2.4. Parameter Optimization

Model parameters were estimated by minimizing weighted residuals between clinical data and simulations. The cost function was defined as

with weights

based on study size and measurement error. One hundred optimization runs with varying initial conditions were performed. Fitting proceeded in two stages: first pharmacokinetic, then pharmacodynamic parameters. Independent datasets including multiple dosing and impairment scenarios were used for validation.

2.5. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Parameters

Pharmacokinetic parameters for losartan, E3174, and L158 were derived using non-compartmental methods. The elimination rate () was estimated from log-linear regression of the terminal phase. The area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) was computed by trapezoidal rule and extrapolation. Apparent clearance () and volume of distribution () were derived from and , where D is dose. Pharmacodynamic outputs (renin, angiotensin, aldosterone, blood pressure) were summarized by maximal and minimal values.

3. Results

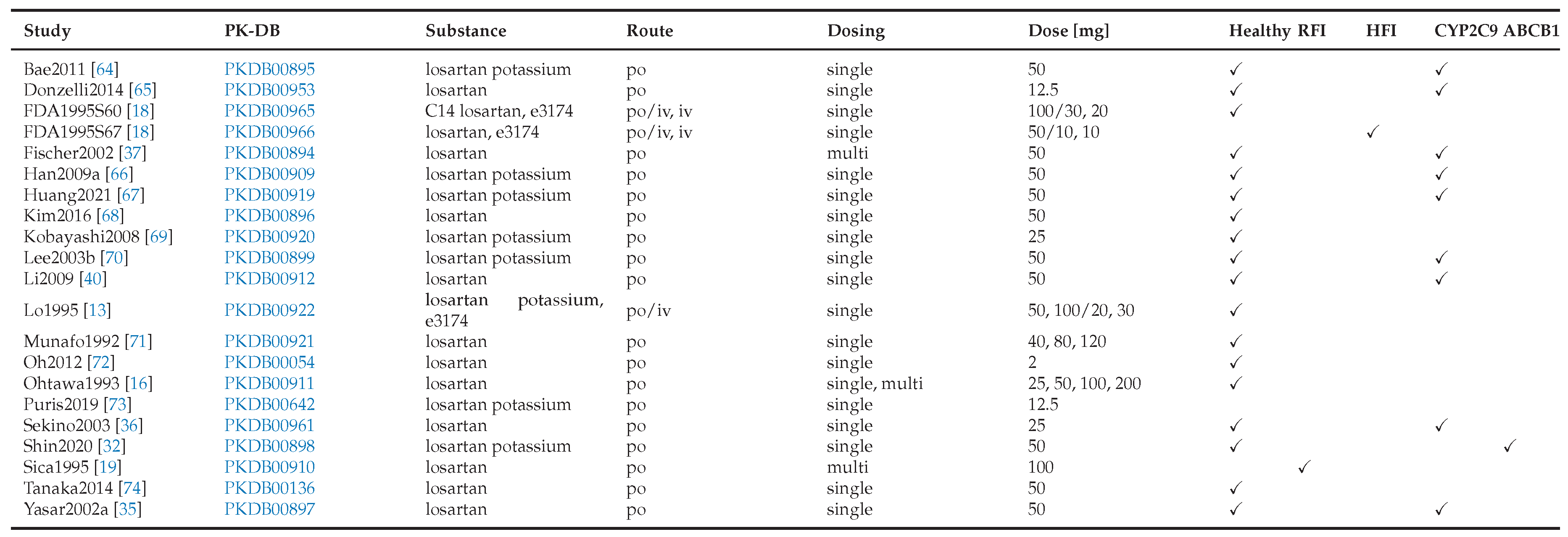

3.1. Losartan Database

An open database containing pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data of losartan from 24 clinical studies was compiled, covering a range of dosing regimens, physiological conditions and different genotypes (

Table 1). This dataset served as the basis for developing the losartan PBPK/PD model.

3.2. Computational Model

A PBPK/PD model of losartan was created that includes key factors that determine intra- and inter-individual variability (

Figure 2). The model includes the organs involved in the pharmacokinetics of losartan (gastrointestinal tract, liver, and kidney), connected through the systemic circulation, as well as the main pharmacodynamic outputs of the RAAS (renin, angiontensin I, aldosterone, systolic and diastolic blood pressure). The main patient-specific factors that are known to affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of losartan are included in the model. Specifically, four key factors were included: dose dependency, liver impairment, renal impairment, and genotype variability.

3.3. Dose Dependency

Dose-dependent behavior of the losartan PBPK/PD model was assessed by simulating oral doses between 10 and 100 mg (

Figure 3). The model captures the pharmacokinetics of losartan and its active metabolite E3174 in plasma, urine, and feces, as well as the associated pharmacodynamic responses (aldosterone, renin, angiotensin I, and blood pressure). Simulations reproduced key dose-related trends: increasing exposure with dose, a decreasing E3174/losartan ratio at higher doses, nonlinear increases in AUC and

(particularly for E3174), and dose-dependent prolongation of E3174 half-life. On the pharmacodynamic level, higher doses produced stronger suppression of aldosterone and blood pressure, accompanied by compensatory increases in renin and angiotensin I. These patterns are consistent with findings from published clinical studies (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

3.4. Hepatic Impairment

Figure 5 shows the impact of hepatic dysfunction on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of losartan and E3174. As cirrhosis severity increases, losartan plasma and urine concentrations rise, while E3174 levels and the E3174/losartan ratio decrease. Fecal excretion remains largely unchanged, indicating that hepatic impairment predominantly affects metabolic clearance rather than biliary elimination.

Pharmacokinetic analysis reveals increasing AUC, C

max, and half-life for both losartan and E3174 with worsening cirrhosis, accompanied by a decline in the elimination rate constant (kel). While losartan accumulation is qualitatively consistent with clinical observations from patients with mild to moderate cirrhosis [

8,

11], the model underestimates absolute concentrations, particularly for E3174, which shows a delayed but modest increase in plasma levels at higher cirrhosis degrees. This discrepancy likely reflects unaccounted factors such as reduced hepatic blood flow, altered enzyme activity, or additional compensatory mechanisms [

27].

Pharmacodynamically, impaired liver function attenuates the formation of E3174 and modifies RAAS regulation. Early renin and angiotensin I responses are reduced, while aldosterone and blood pressure increase initially, with prolonged elevation in more severe cirrhosis. These trends correspond to delayed normalization of hormonal and hemodynamic parameters. Despite sparse PD data and limited control groups, the model reproduces general concentration–time and dose–response patterns, supporting the clinical recommendation of dose adjustment in hepatic impairment. This is particularly relevant for patients with comorbidities such as heart failure, where sensitivity to RAAS inhibition is increased [

35,

36].

3.5. Renal Impairment

Figure 6 illustrates the effect of declining renal function on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of losartan and its active metabolite E3174. As renal function decreases, losartan plasma concentrations remain largely unchanged, whereas E3174 levels increase, accompanied by reduced urinary excretion of both compounds. Fecal excretion of losartan shows a slight compensatory rise, and the E3174/losartan ratio increases with impaired renal clearance.

On the pharmacokinetic level, the model predicts stable AUC and C

max values for losartan, while E3174 shows rising AUC, C

max, and half-life as renal function declines, reflecting reduced clearance. These results align qualitatively with the physiology of renal elimination, though they overestimate metabolite accumulation compared to clinical findings [

19,

28], where E3174 exposure remained stable across renal function groups. This discrepancy may indicate unaccounted processes such as altered absorption, metabolism, or hepatic clearance of E3174 [

11].

Pharmacodynamically, impaired renal function amplifies losartan’s antihypertensive effects. The model predicts stronger suppression of aldosterone and systolic blood pressure, along with compensatory rises in renin and angiotensin I. While direct PD data in renally impaired populations are limited, these predictions are physiologically plausible and extend clinical observations. Nevertheless, the degree of RAAS suppression may be slightly overestimated due to the absence of compensatory mechanisms such as altered hepatic clearance or long-term feedback regulation [

36,

37,

77].

3.6. ABCB1 Genotypes

Figure 7 illustrates the influence of ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein) transporter activity on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of losartan and E3174. Simulations across varying transporter activity levels, including common diplotypes (GG/CC, GT/CT, TT/TT), show that reduced ABCB1 activity leads to increased plasma and urinary concentrations of both compounds, while fecal excretion of losartan declines due to decreased intestinal and biliary efflux.

Pharmacokinetic analysis indicates modest increases in AUC and C

max for losartan and E3174 with lower ABCB1 activity, whereas elimination rate constants (kel) and half-life remain largely unchanged. The plasma and urine E3174/losartan ratio decreases slightly under low transporter activity. These trends are qualitatively consistent with clinical observations [

32], although absolute concentrations are slightly underestimated by the model.

Pharmacodynamically, reduced ABCB1 activity slightly enhances RAAS-related effects, including modest increases in renin and angiotensin I and marginal reductions in aldosterone and blood pressure. While these changes are small and unlikely to necessitate dose adjustments based on ABCB1 diplotype alone, the model demonstrates the capacity to predict subtle genotype-dependent differences in drug exposure and pharmacodynamic response. Future refinement could include better representation of renal P-gp expression and its contribution to systemic clearance, as well as additional clinical data on pharmacodynamic outcomes to improve predictive accuracy [

32].

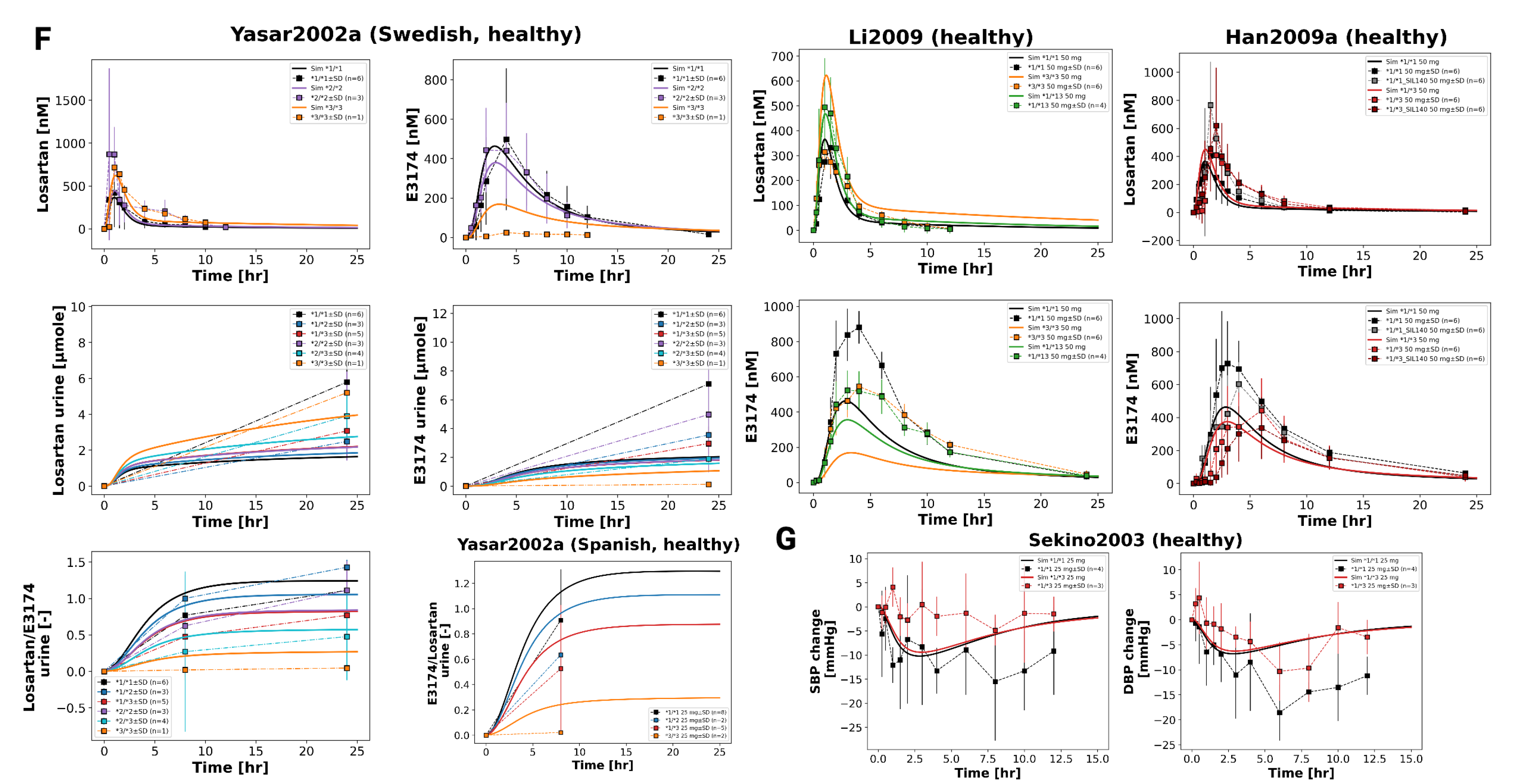

3.7. CYP2C9 Genotypes

Figure 8 illustrates the impact of CYP2C9 genetic variability on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of losartan and its active metabolite E3174. Simulations across a continuous range of CYP2C9 activity, as well as genotype-specific simulations for *1/*1, *1/*2, *1/*3, *1/*13, *2/*2, *2/*3, and *3/*3, demonstrate that reduced enzyme activity leads to impaired metabolic conversion, resulting in higher plasma, urine, and fecal levels of losartan and decreased E3174 exposure.

Pharmacodynamically, lower CYP2C9 activity diminishes RAAS inhibition, with smaller reductions in aldosterone and systolic blood pressure, and attenuated compensatory increases in renin and angiotensin I. AUC and C

max for losartan rise with declining enzyme activity, while E3174 exposure decreases; elimination rate constants and half-life remain relatively stable. These model predictions are consistent with clinical observations, which report 1.6- to 3-fold increases in losartan AUC and significantly reduced E3174 levels in carriers of reduced-function alleles [

35,

36,

37], although absolute concentrations tend to be slightly underestimated.

The use of a continuous CYP2C9 activity scale enables the simulation of nonlinear relationships between enzyme activity and metabolite formation across a spectrum of genotypes. While CYP2C9 genotype is a major determinant of inter-individual variability, other factors such as age, comorbidities, and concomitant medications may further influence pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. From a clinical perspective, these findings support the potential of genotype-guided dosing for patients with reduced-function alleles, although high variability within genotype groups suggests that genetic testing should be applied selectively, focusing on individuals with inadequate response or elevated risk of adverse effects.

Figure 9.

continued: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of losartan and metabolites across varying CYP2C9 activity levels. (F) Simulated versus observed losartan pharmacokinetics. Data from [

35,

40,

66]. Simulated versus observed SBP and DBP for different CYP2C9 genotypes [

36].

Figure 9.

continued: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of losartan and metabolites across varying CYP2C9 activity levels. (F) Simulated versus observed losartan pharmacokinetics. Data from [

35,

40,

66]. Simulated versus observed SBP and DBP for different CYP2C9 genotypes [

36].

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed and evaluated a physiologically based pharmacokinetic/ pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) model of losartan, informed by a curated database of 24 clinical studies covering diverse dosing regimens, populations, and physiological conditions. The model integrates intestinal absorption, hepatic metabolism via CYP2C9, and renal excretion, while linking systemic exposure of the active metabolite E3174 to downstream pharmacodynamic effects through a simplified RAAS submodel. This framework enables simulation of losartan and metabolite concentrations in plasma, urine, and feces, as well as prediction of pharmacodynamic endpoints such as renin, angiotensin I, aldosterone, and systolic blood pressure under baseline and perturbed conditions. By reproducing key clinical observations, the model demonstrates its potential to provide mechanistic insights into inter-individual variability and support personalized dosing strategies.

The curated database was essential for calibration and validation of the model, but it also highlights important limitations. While losartan pharmacokinetics are well characterized, data on RAAS dynamics remain limited, particularly with respect to circadian variability and long-term feedback regulation. Excretion data—especially for fecal elimination and the secondary metabolite L158—were sparse, and pharmacodynamic datasets showed high variability across studies. These gaps restrict the predictive accuracy of the model under complex physiological conditions but do not preclude its use in capturing system-level dose–exposure–response relationships.

Our dose dependency simulations reproduced the nonlinear pharmacokinetics of losartan and E3174, demonstrating a decreasing metabolite-to-parent ratio at higher doses due to saturable CYP2C9 metabolism. Consistent with clinical findings, increasing doses resulted in stronger and more sustained suppression of aldosterone and systolic blood pressure, accompanied by compensatory increases in renin and angiotensin I. This supports the model’s ability to capture both nonlinear PK behavior and dose-dependent RAAS responses.

In hepatic impairment, the model predicted elevated losartan plasma concentrations, reduced clearance, and attenuated metabolite formation, reflecting impaired CYP2C9 metabolism and hepatic blood flow. While the model underestimated the reported accumulation of E3174 in cirrhosis, it nonetheless confirmed the need for dose reduction in patients with liver dysfunction, particularly in comorbid conditions such as heart failure where sensitivity to RAAS inhibition is heightened.

Renal impairment simulations predicted reduced clearance of both losartan and E3174, leading to prolonged systemic exposure. While these results are qualitatively consistent with PK data, the model overestimated E3174 accumulation compared to reported clinical findings. Importantly, in the absence of PD data from impaired populations, the model allowed prediction of enhanced RAAS suppression and blood pressure reduction—although these effects may be slightly exaggerated due to the omission of compensatory mechanisms.

Genetic variability was also explored. For CYP2C9, the model captured the pronounced impact of reduced-function alleles on E3174 formation and downstream pharmacodynamic effects, reproducing the diminished blood pressure reduction observed clinically. The use of a continuous enzyme activity scale enabled simulation across a spectrum of genotypic variability. In contrast, ABCB1 (P-gp) variability had only minor effects on systemic exposure and blood pressure, consistent with limited clinical data, although the model suggests possible contributions via altered intestinal efflux and renal secretion. These findings emphasize the potential of PBPK/PD modeling to disentangle the contributions of genetic variability to losartan response.

Looking forward, several opportunities for refinement exist. Incorporating circadian rhythm, sodium and water balance, and autonomic feedback would enhance physiological fidelity of the RAAS submodel. Expanding datasets for fecal excretion, L158 kinetics, and pharmacodynamic outcomes would strengthen calibration. Future model extensions could also integrate additional sources of variability, such as age, comorbidities, or transporter–enzyme interactions, to support population-level simulations. Ultimately, the losartan PBPK/PD framework provides a mechanistically grounded platform for exploring inter-individual variability and optimizing dosing strategies, with potential applications in precision medicine and clinical decision support.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a comprehensive physiologically based pharmacokinetic/ pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) model of losartan was developed and validated using an extensive clinical database. The model successfully reproduced key pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic behaviors, including dose-dependent RAAS inhibition and nonlinear metabolite formation resulting from saturable CYP2C9 metabolism. Simulations captured the attenuated pharmacodynamic response under hepatic impairment and predicted enhanced RAAS suppression in renal dysfunction. Furthermore, the model quantified the pronounced impact of CYP2C9 genetic variability on metabolite exposure and blood pressure effects, while ABCB1 activity contributed only minor modulation of systemic exposure.

Despite certain limitations in clinical data and model scope, the framework provides valuable mechanistic insight into inter-individual variability in losartan response. It highlights the potential of systems pharmacology modeling to support dose optimization across physiological and genetic conditions. Together, the losartan database and PBPK/PD model establish a solid foundation for future integration into digital twin platforms and personalized therapy design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K..; methodology, M.K.; software, M.K.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, E.T.; investigation, E.T.; resources, M.K.; data curation, E.T., M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.T.; writing—review and editing, M.K., E.T.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

M.K. was supported by the BMBF grant number 031L0304B and by the DFG grant number 436883643 and 465194077.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the BMBF-funded de.NBI Cloud within the German Network for Bioinformatics Infrastructure (de.NBI) (031A537B, 031A533A, 031A538A, 031A533B, 031A535A, 031A537C, 031A534A, 031A532B).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- (WHO), W.H.O. Hypertension. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension, 2023.

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide Trends in Hypertension Prevalence and Progress in Treatment and Control from 1990 to 2019: A Pooled Analysis of 1201 Population-Representative Studies with 104 Million Participants. Lancet (London, England) 2021, 398, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, F.D.; Whelton, P.K. High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 1979) 2020, 75, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, J.H.; Kaur, J.; Lappin, S.L. System. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Atlas, S.A. The Renin-Angiotensin Aldosterone System: Pathophysiological Role and Pharmacologic Inhibition. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 2007, 13, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, D.; Flather, M.D.; Altman, D.G.; Holmes, J.; Rosano, G.; Wikstrand, J.; Packer, M.; Coats, A.J.S.; Manzano, L.; Böhm, M.; et al. Heart Rate and Rhythm and the Benefit of Beta-Blockers in Patients With Heart Failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017, 69, 2885–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R. RAAS Inhibition and Mortality in Hypertension. Global Cardiology Science and Practice 2013, 2013, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnier, M.; Wuerzner, G. Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of Losartan. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology 2011, 7, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.; Mandalia, R. Diuretics and the Kidney. BJA education 2022, 22, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.E.; Hayden, S.L.; Meyer, H.R.; Sandoz, J.L.; Arata, W.H.; Dufrene, K.; Ballaera, C.; Lopez Torres, Y.; Griffin, P.; Kaye, A.M.; et al. The Evolving Role of Calcium Channel Blockers in Hypertension Management: Pharmacological and Clinical Considerations. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2024, 46, 6315–6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sica, D.A.; Gehr, T.W.B.; Ghosh, S. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Losartan. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2005, 44, 797–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Cozaar Labeling-Package Insert. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/020386s064lbl.pdf, 2021.

- Lo, M.W.; Goldberg, M.R.; McCrea, J.B.; Lu, H.; Furtek, C.I.; Bjornsson, T.D. Pharmacokinetics of Losartan, an Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonist, and Its Active Metabolite EXP3174 in Humans. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 1995, 58, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goa, K.L.; Wagstaff, A.J. Losartan Potassium: A Review of Its Pharmacology, Clinical Efficacy and Tolerability in the Management of Hypertension. Drugs 1996, 51, 820–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.A.; Hagenbuch, B.A.; Reed, G.A. Losartan Is a Substrate of Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide 2B1. The FASEB Journal 2010, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtawa, M.; Takayama, F.; Saitoh, K.; Yoshinaga, T.; Nakashima, M. Pharmacokinetics and Biochemical Efficacy after Single and Multiple Oral Administration of Losartan, an Orally Active Nonpeptide Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonist, in Humans. British journal of clinical pharmacology 1993, 35, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, D.D. Human Plasma Protein Binding of the Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonist Losartan Potassium (DuP 753/MK 954) and Its Pharmacologically Active Metabolite EXP3174. Journal of clinical pharmacology 1995, 35, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. 020386Orig1s000rev - COZAAR FDA Review. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/96/020386Orig1s000rev.pdf, 1995.

- Sica, D.A.; Lo, M.W.; Shaw, W.C.; Keane, W.F.; Gehr, T.W.; Halstenson, C.E.; Lipschutz, K.; Furtek, C.I.; Ritter, M.A.; Shahinfar, S. The Pharmacokinetics of Losartan in Renal Insufficiency. Journal of hypertension. Supplement : official journal of the International Society of Hypertension 1995, 13, S49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonen, A.; Finel, M.; Kostiainen, R. The Human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase UGT1A3 Is Highly Selective towards N2 in the Tetrazole Ring of Losartan, Candesartan, and Zolarsartan. Biochemical pharmacology 2008, 76, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.H. Aldosterone Biosynthesis, Regulation, and Classical Mechanism of Action. Heart Failure Reviews 2005, 10, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, G.P.; Lenzini, L.; Caroccia, B.; Rossitto, G.; Seccia, T.M. Angiotensin Peptides in the Regulation of Adrenal Cortical Function. Exploration of Medicine 2021, 2, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamohan, S.B.; Raghuraman, G.; Prabhakar, N.R.; Kumar, G.K. NADPH Oxidase-Derived H(2)O(2) Contributes to Angiotensin II-induced Aldosterone Synthesis in Human and Rat Adrenal Cortical Cells. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2012, 17, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, B.; Schrankl, J.; Steppan, D.; Neubauer, K.; Sequeira-Lopez, M.L.; Pan, L.; Gomez, R.A.; Coffman, T.M.; Gross, K.W.; Kurtz, A.; et al. Angiotensin II Short-Loop Feedback: Is There a Role of Ang II for the Regulation of the Renin System In Vivo? Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 1979) 2018, 71, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerl, M.C.; Richthammer, W.; Kurtz, A.; Krämer, B.K. Angiotensin II Feedback Is a Regulator of Renocortical Renin, COX-2, and nNOS Expression. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2002, 282, R1613–R1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante, B.; Piras, O.; De Paolis, P.; Porcellini, A.; Natale, A.; Volpe, M. Role of the Angiotensin II AT2-subtype Receptors in the Blood Pressure-Lowering Effect of Losartan in Salt-Restricted Rats. Journal of Hypertension 1998, 16, 2039–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, M.; Caffe, S.E.; Michalak, R.A.; Reid, J.L. Losartan, an Orally Active Angiotensin (AT1) Receptor Antagonist: A Review of Its Efficacy and Safety in Essential Hypertension. Pharmacology & therapeutics 1997, 74, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, A.A.; Gehr, T.W.; Brophy, D.F.; Sica, D.A. The Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Losartan in Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis. Journal of clinical pharmacology 2000, 40, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitani, T.; Yagi, H.; Inotsume, N.; Yasuhara, M. Effect of Experimental Renal Failure on the Pharmacokinetics of Losartan in Rats. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin 2002, 25, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, D.A.; Halstenson, C.E.; Gehr, T.W.; Keane, W.F. Pharmacokinetics and Blood Pressure Response of Losartan in End-Stage Renal Disease. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2000, 38, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göktaş, M.T.; Pepedil, F.; Karaca, Ö.; Kalkışım, S.; Cevik, L.; Gumus, E.; Guven, G.S.; Babaoglu, M.O.; Bozkurt, A.; Yasar, U. Relationship between Genetic Polymorphisms of Drug Efflux Transporter MDR1 (ABCB1) and Response to Losartan in Hypertension Patients. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2016, 20, 2460–2467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.B.; Jung, E.H.; Kang, P.; Lim, C.W.; Oh, K.Y.; Cho, C.K.; Lee, Y.J.; Choi, C.I.; Jang, C.G.; Lee, S.Y.; ABCB1, c.; et al. 2677G>T/c.3435C>T Diplotype Increases the Early-Phase Oral Absorption of Losartan. Archives of pharmacal research 2020, 43, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haufroid, V. Genetic Polymorphisms of ATP-binding Cassette Transporters ABCB1 and ABCC2 and Their Impact on Drug Disposition. Current Drug Targets 2011, 12, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, U.; Eliasson, E.; Forslund-Bergengren, C.; Tybring, G.; Gadd, M.; Sjöqvist, F.; Dahl, M.L. The Role of CYP2C9 Genotype in the Metabolism of Diclofenac in Vivo and in Vitro. European journal of clinical pharmacology 2001, 57, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, U.; Forslund-Bergengren, C.; Tybring, G.; Dorado, P.; Llerena, A.; Sjöqvist, F.; Eliasson, E.; Dahl, M.L. Pharmacokinetics of Losartan and Its Metabolite E-3174 in Relation to the CYP2C9 Genotype. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2002, 71, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekino, K.; Kubota, T.; Okada, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Horiuchi, R.; Kimura, K.; Iga, T. Effect of the Single CYP2C9*3 Allele on Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Losartan in Healthy Japanese Subjects. European journal of clinical pharmacology 2003, 59, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.L.; Pieper, J.A.; Graff, D.W.; Rodgers, J.E.; Fischer, J.D.; Parnell, K.J.; Goldstein, J.A.; Greenwood, R.; Patterson, J.H. Evaluation of Potential Losartan-Phenytoin Drug Interactions in Healthy Volunteers. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2002, 72, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miners, J.O.; Birkett, D.J. Cytochrome P4502C9: An Enzyme of Major Importance in Human Drug Metabolism. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1998, 45, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taube, J.; Halsall, D.; Baglin, T. Influence of Cytochrome P-450 CYP2C9 Polymorphisms on Warfarin Sensitivity and Risk of over-Anticoagulation in Patients on Long-Term Treatment. Blood 2000, 96, 1816–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, G.; Wang, L.S.; Zhang, W.; Tan, Z.R.; Fan, L.; Chen, B.L.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Tu, J.H.; et al. Effects of the CYP2C9*13 Allele on the Pharmacokinetics of Losartan in Healthy Male Subjects. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems 2009, 39, 788–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.F.; Liu, J.P.; Chowbay, B. Polymorphism of Human Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and Its Clinical Impact. Drug Metabolism Reviews 2009, 41, 89–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez Hernandez, F.; Carter, S.J.; Iso-Sipilä, J.; Goldsmith, P.; Almousa, A.A.; Gastine, S.; Lilaonitkul, W.; Kloprogge, F.; Standing, J.F. An Automated Approach to Identify Scientific Publications Reporting Pharmacokinetic Parameters. Wellcome Open Research 2021, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorzewski, J.; Brandhorst, J.; Green, K.; Eleftheriadou, D.; Duport, Y.; Barthorscht, F.; Köller, A.; Ke, D.Y.J.; De Angelis, S.; König, M. PK-DB: Pharmacokinetics Database for Individualized and Stratified Computational Modeling. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D1358–D1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer - a Computer Vision Assisted Software That Helps Extract Numerical Data from Images of a Variety of Data Visualizations, 2024.

- Hucka, M.; Bergmann, F.T.; Chaouiya, C.; Dräger, A.; Hoops, S.; Keating, S.M.; König, M.; Novère, N.L.; Myers, C.J.; Olivier, B.G.; et al. The Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML): Language Specification for Level 3 Version 2 Core Release 2. Journal of Integrative Bioinformatics 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, S.M.; Waltemath, D.; König, M.; Zhang, F.; Dräger, A.; Chaouiya, C.; Bergmann, F.T.; Finney, A.; Gillespie, C.S.; Helikar, T.; et al. SBML Level 3: An Extensible Format for the Exchange and Reuse of Biological Models. Molecular Systems Biology 2020, 16, e9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, M. Sbmlutils: Python Utilities for SBML. Zenodo, 2024. [CrossRef]

- König, M.; Dräger, A.; Holzhütter, H.G. CySBML: A Cytoscape Plugin for SBML. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2402–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, M. Sbmlsim: SBML Simulation Made Easy. Zenodo, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, C.; Xu, J.; Smith, L.; König, M.; Choi, K.; Sauro, H.M. libRoadRunner 2.0: A High Performance SBML Simulation and Analysis Library. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somogyi, E.T.; Bouteiller, J.M.; Glazier, J.A.; König, M.; Medley, J.K.; Swat, M.H.; Sauro, H.M. libRoadRunner: A High Performance SBML Simulation and Analysis Library. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3315–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tensil, E.; König, M. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic/ Pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) Model of Losartan. Zenodo, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Köller, A.; Grzegorzewski, J.; König, M. Physiologically Based Modeling of the Effect of Physiological and Anthropometric Variability on Indocyanine Green Based Liver Function Tests. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12, 757293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köller, A.; Grzegorzewski, J.; Tautenhahn, H.M.; König, M. Prediction of Survival After Partial Hepatectomy Using a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model of Indocyanine Green Liver Function Tests. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12, 730418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, C.G.; Turcotte, J.G. Surgery and Portal Hypertension. Major Problems in Clinical Surgery 1964, 1, 1–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, R.N.; Murray-Lyon, I.M.; Dawson, J.L.; Pietroni, M.C.; Williams, R. Transection of the Oesophagus for Bleeding Oesophageal Varices. The British Journal of Surgery 1973, 60, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallol, B.S.; Grzegorzewski, J.; Tautenhahn, H.M.; König, M. Insights into Intestinal P-glycoprotein Function Using Talinolol: A PBPK Modeling Approach, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, K.; Harakawa, N.; Sugiyama, E.; Tohkin, M.; Kim, S.R.; Kaniwa, N.; Katori, N.; Hasegawa, R.; Yasuda, K.; Kamide, K.; et al. Substrate-Dependent Functional Alterations of Seven CYP2C9 Variants Found in Japanese Subjects. Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals 2009, 37, 1895–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusama, M.; Maeda, K.; Chiba, K.; Aoyama, A.; Sugiyama, Y. Prediction of the Effects of Genetic Polymorphism on the Pharmacokinetics of CYP2C9 Substrates from in Vitro Data. Pharmaceutical research 2009, 26, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.H.; Pan, P.P.; Dai, D.P.; Wang, S.H.; Geng, P.W.; Cai, J.P.; Hu, G.X. Effect of 36 CYP2C9 Variants Found in the Chinese Population on Losartan Metabolism in Vitro. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems 2014, 44, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmeyer, S.; Burk, O.; von Richter, O.; Arnold, H.P.; Brockmöller, J.; Johne, A.; Cascorbi, I.; Gerloff, T.; Roots, I.; Eichelbaum, M.; et al. Functional Polymorphisms of the Human Multidrug-Resistance Gene: Multiple Sequence Variations and Correlation of One Allele with P-glycoprotein Expression and Activity in Vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2000, 97, 3473–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegmund, W.; Ludwig, K.; Giessmann, T.; Dazert, P.; Schroeder, E.; Sperker, B.; Warzok, R.; Kroemer, H.K.; Cascorbi, I. The Effects of the Human MDR1 Genotype on the Expression of Duodenal P-glycoprotein and Disposition of the Probe Drug Talinolol. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2002, 72, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.w.; Choi, C.i.; Kim, M.j.; Oh, D.h.; Keum, S.k.; Park, J.i.; Kim, B.h.; Bang, H.k.; Oh, S.g.; Kang, B.s.; et al. Frequency of CYP2C9 Alleles in Koreans and Their Effects on Losartan Pharmacokinetics. Acta pharmacologica Sinica 2011, 32, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donzelli, M.; Derungs, A.; Serratore, M.G.; Noppen, C.; Nezic, L.; Krähenbühl, S.; Haschke, M. The Basel Cocktail for Simultaneous Phenotyping of Human Cytochrome P450 Isoforms in Plasma, Saliva and Dried Blood Spots. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2014, 53, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Guo, D.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tan, Z.R.; Zhou, H.H. Effect of Silymarin on the Pharmacokinetics of Losartan and Its Active Metabolite E-3174 in Healthy Chinese Volunteers. European journal of clinical pharmacology 2009, 65, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.X.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, T.; Ai, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, Y. Effect of CYP2C9 Genetic Polymorphism and Breviscapine on Losartan Pharmacokinetics in Healthy Subjects. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems 2021, 51, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.G.; Kim, Y.; Jeon, J.Y.; Kim, D.S. Effect of Fermented Red Ginseng on Cytochrome P450 and P-glycoprotein Activity in Healthy Subjects, as Evaluated Using the Cocktail Approach. British journal of clinical pharmacology 2016, 82, 1580–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Takagi, M.; Fukumoto, K.; Kato, R.; Tanaka, K.; Ueno, K. The Effect of Bucolome, a CYP2C9 Inhibitor, on the Pharmacokinetics of Losartan. Drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics 2008, 23, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.R.; Pieper, J.A.; Hinderliter, A.L.; Blaisdell, J.A.; Goldstein, J.A. Losartan and E3174 Pharmacokinetics in Cytochrome P450 2C9*1/*1, *1/*2, and *1/*3 Individuals. Pharmacotherapy 2003, 23, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munafo, A.; Christen, Y.; Nussberger, J.; Shum, L.Y.; Borland, R.M.; Lee, R.J.; Waeber, B.; Biollaz, J.; Brunner, H.R. Drug Concentration Response Relationships in Normal Volunteers after Oral Administration of Losartan, an Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonist. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 1992, 51, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.S.; Park, S.J.; Shinde, D.D.; Shin, J.G.; Kim, D.H. High-Sensitivity Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry for the Simultaneous Determination of Five Drugs and Their Cytochrome P450-specific Probe Metabolites in Human Plasma. Journal of chromatography. B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences 2012, 895–896, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puris, E.; Pasanen, M.; Ranta, V.P.; Gynther, M.; Petsalo, A.; Käkelä, P.; Männistö, V.; Pihlajamäki, J. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery Influenced Pharmacokinetics of Several Drugs given as a Cocktail with the Highest Impact Observed for CYP1A2, CYP2C8 and CYP2E1 Substrates. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology 2019, 125, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Uchida, S.; Inui, N.; Takeuchi, K.; Watanabe, H.; Namiki, N. Simultaneous LC-MS/MS Analysis of the Plasma Concentrations of a Cocktail of 5 Cytochrome P450 Substrate Drugs and Their Metabolites. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin 2014, 37, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M.R.; Bradstreet, T.E.; McWilliams, E.J.; Tanaka, W.K.; Lipert, S.; Bjornsson, T.D.; Waldman, S.A.; Osborne, B.; Pivadori, L.; Lewis, G. Biochemical Effects of Losartan, a Nonpeptide Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonist, on the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System in Hypertensive Patients. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 1979) 1995, 25, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doig, J.K.; MacFadyen, R.J.; Sweet, C.S.; Lees, K.R.; Reid, J.L. Dose-Ranging Study of the Angiotensin Type I Receptor Antagonist Losartan (DuP753/MK954), in Salt-Deplete Normal Man. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 1993, 21, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. FDA1995S67 - 020386Orig1s000rev - COZAAR FDA Review. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/96/020386Orig1s000rev.pdf, 1995.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).