1. Introduction

The global burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has reached critical levels, which poses substantial health and economic challenges [

1,

2]. However, a major challenge in T2DM management is optimizing treatment, as standardized drug dosing approaches can lead to inadequate glycemic control and increase the risk of adverse events like hypoglycemia [

3]. To address this, personalized dosing strategies, integrating patient-specific data, are increasingly recognized as vital for improving therapeutic effect and safety [

4].

Glimepiride, a second-generation sulfonylurea, is widely used in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus [

5,

6]. It primarily acts by binding to the sulfonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1) subunit of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in pancreatic

-cells, which triggers channel closure, membrane depolarization, and calcium influx, ultimately stimulating insulin secretion and thereby lowering blood glucose levels [

5,

7].

Despite its widespread use, glimepiride exhibits notable inter-individual variability in its pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) response [

8]. This variability is largely driven by factors such as genetic polymorphisms in the metabolizing enzyme CYP2C9, as well as common comorbidities in T2DM including renal and hepatic impairment [

6,

8,

9]. CYP2C9 genetic variants, particularly *2 (Arg144Cys) and *3 (Ile359Leu) alleles, greatly reduce enzymatic activity compared to the wild-type (*1), with carriers demonstrating up to 2.5-fold increased glimepiride exposure and heightened hypoglycemia risk [

8,

10]. Similarly, renal and hepatic dysfunction can further impact systemic drug exposure and therapeutic response [

11,

12]. Consequently, reliably predicting patient response and selecting optimal, safe glimepiride doses remains a clinical difficulty.

While empirical glimepiride pharmacokinetics models have explored aspects like genetic influence [

8] or drug-effects [

13], they are limited in their ability to capture the integrated effects of genetic polymorphisms, impaired organ function, and physiological characteristics. This partial integration of variability factors constrains their utility for patient-specific dosing decisions in clinical practice [

14,

15].

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling provides a potentially powerful framework to address this challenge [

4,

15,

16]. Unlike traditional empirical pharmacokinetic methods, PBPK simulates drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion based on drug specific properties integrated with physiological systems [

4,

17]. This allows the integration of patient-specific factors (e.g., genetics, organ function) to predict individual drug exposure [

4,

16]. This enables the development of a digital twin, a validated computational replica designed to mirror the drug’s behavior within specific patient populations or individuals, facilitating

in silico pharmacokinetic prediction and personalized simulation of dosing outcomes.

This study details the development and evaluation of a whole-body PBPK model serving as a digital twin for glimepiride. Incorporating key determinants of patient variability, the model demonstrates strong predictive performance against clinical data from diverse patient groups. This digital twin serves as a quantitative tool for exploring individual therapeutic scenarios, enabling patient stratification, and laying the foundation for future clinical decision support tools.

2. Results

2.1. Glimepiride Database

Clinical pharmacokinetic data from 19 studies (

Table 1) were systematically curated to develop the glimepiride digital twin, encompassing diverse patient populations, dosing regimens, and physiological conditions. The workflow for study selection is illustrated in the supplements (

Figure S1). Each study received a unique PK-DB identifier linked to its PubMed ID for traceability, and the curated dataset was made publicly available to promote transparency and reproducibility.

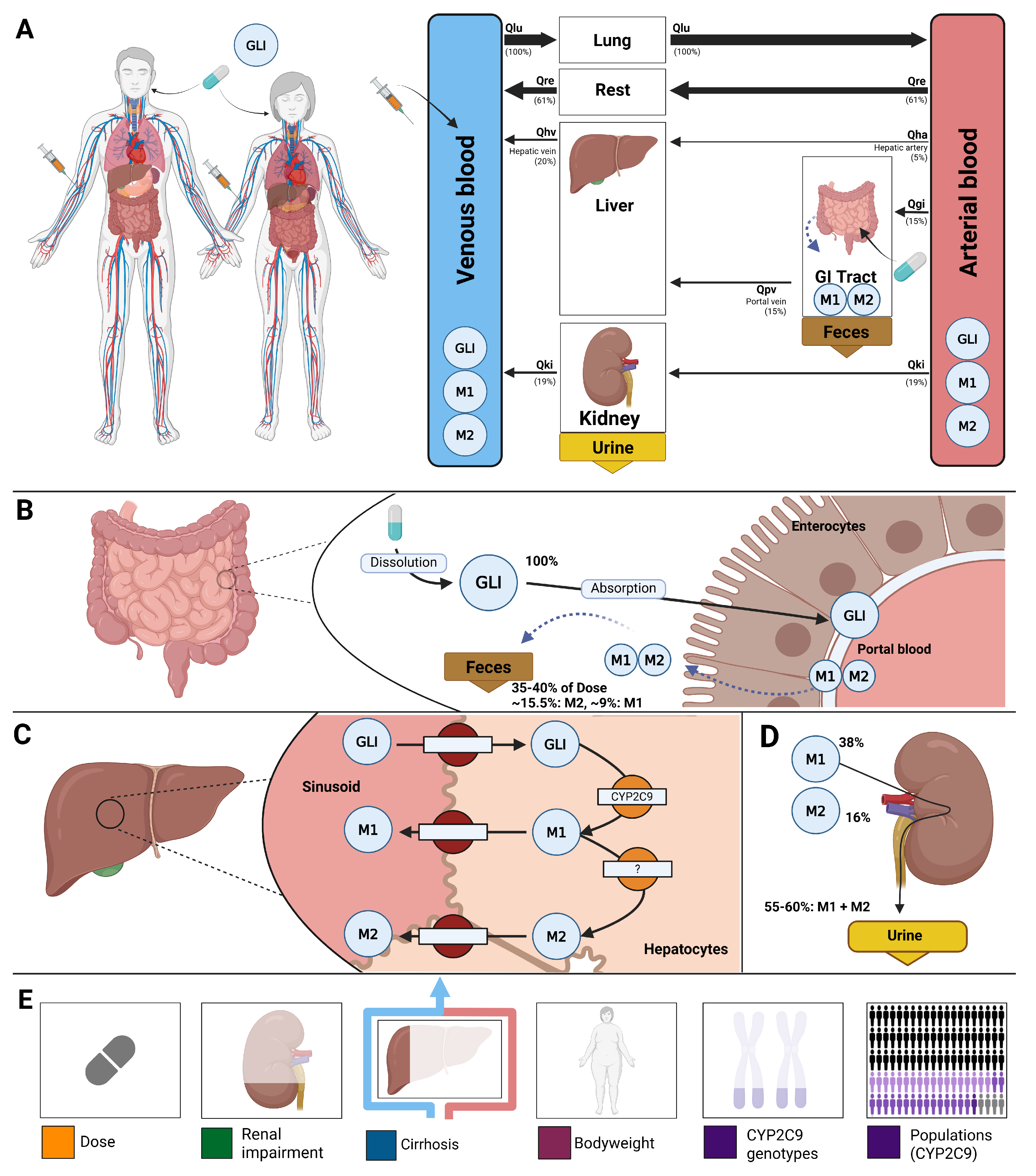

2.2. Computational Model

A whole-body physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model was developed to serve as a digital twin of glimepiride, integrating key determinants of inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability (

Figure 1). The model comprises key organs involved in glimepiride pharmacokinetics: gastrointestinal tract (dissolution and absorption), liver (CYP2C9-mediated metabolism to metabolites M1 and M2), and kidneys (metabolite excretion), connected via systemic circulation compartments. Visualizations of the submodels are provided in the supplements (

Figure S2). The digital twin incorporates patient-specific factors known to influence glimepiride pharmacokinetics: CYP2C9 genotype variants (*1, *2, *3) through enzyme activity scaling (f

cyp2c9), renal function impairment via glomerular filtration rate scaling (f

renal_function), hepatic dysfunction through Child-Turcotte-Pugh score-based scaling (f

cirrhosis), and anthropometric characteristics including bodyweight. Food effects on absorption are captured through bioavailability (f

absorption). This framework enables systematic exploration of how genetic polymorphisms, organ dysfunction, and physiological characteristics influence drug exposure, providing a foundation for personalized dosing strategies. Mathematical descriptions of the model equations and ODEs for all submodels are provided in the supplements (

Sections S3.1–S3.3).

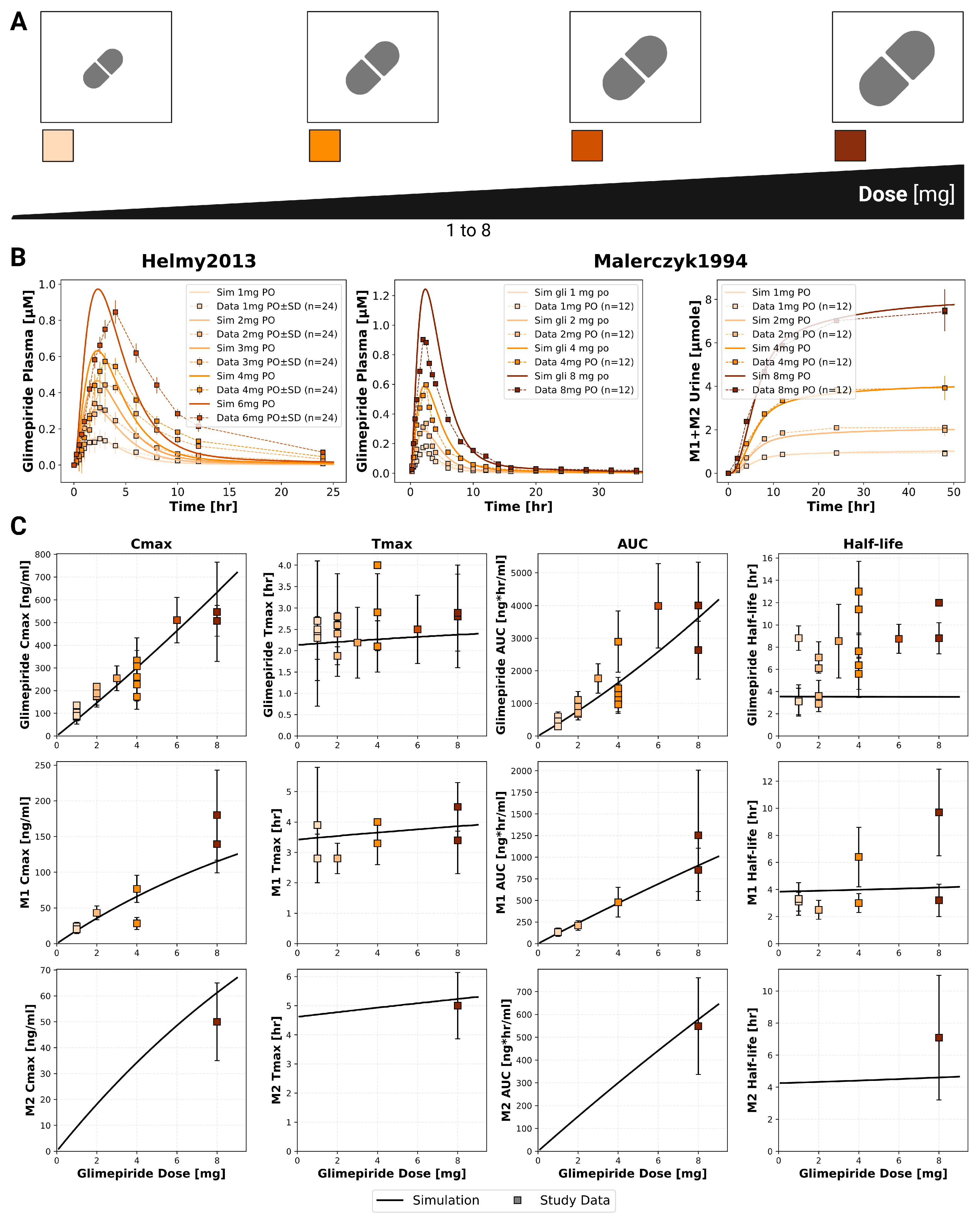

2.3. Dose Dependency

The model confirmed dose-proportional pharmacokinetics within the therapeutic dose range (1–8 mg), with C

max and AUC showing linear increases while T

max and half-life remained consistent across doses (

Figure 2). Specifically, glimepiride C

max increased linearily from approximately 100 ng/mL at 1 mg to 700 ng/mL at 8 mg, while AUC increased proportionally from 500 to 4000 ng*hr/mL. T

max remained stable at 2.0–2.5 hours and half-life at approximately 4 hours across all doses, confirming linear pharmacokinetics. Metabolites M1 and M2 demonstrated similar dose-proportional behavior. Simulations showed good agreement with clinical data from two dose-dependency studies. Comparison with Helmy2012 [

22] and Malerczyk1994 [

28] demonstrated accurate predictions across the dose range. These findings confirm current dosing approaches and supporting the model’s utility for dose optimization and reliable dose titration in clinical practice.

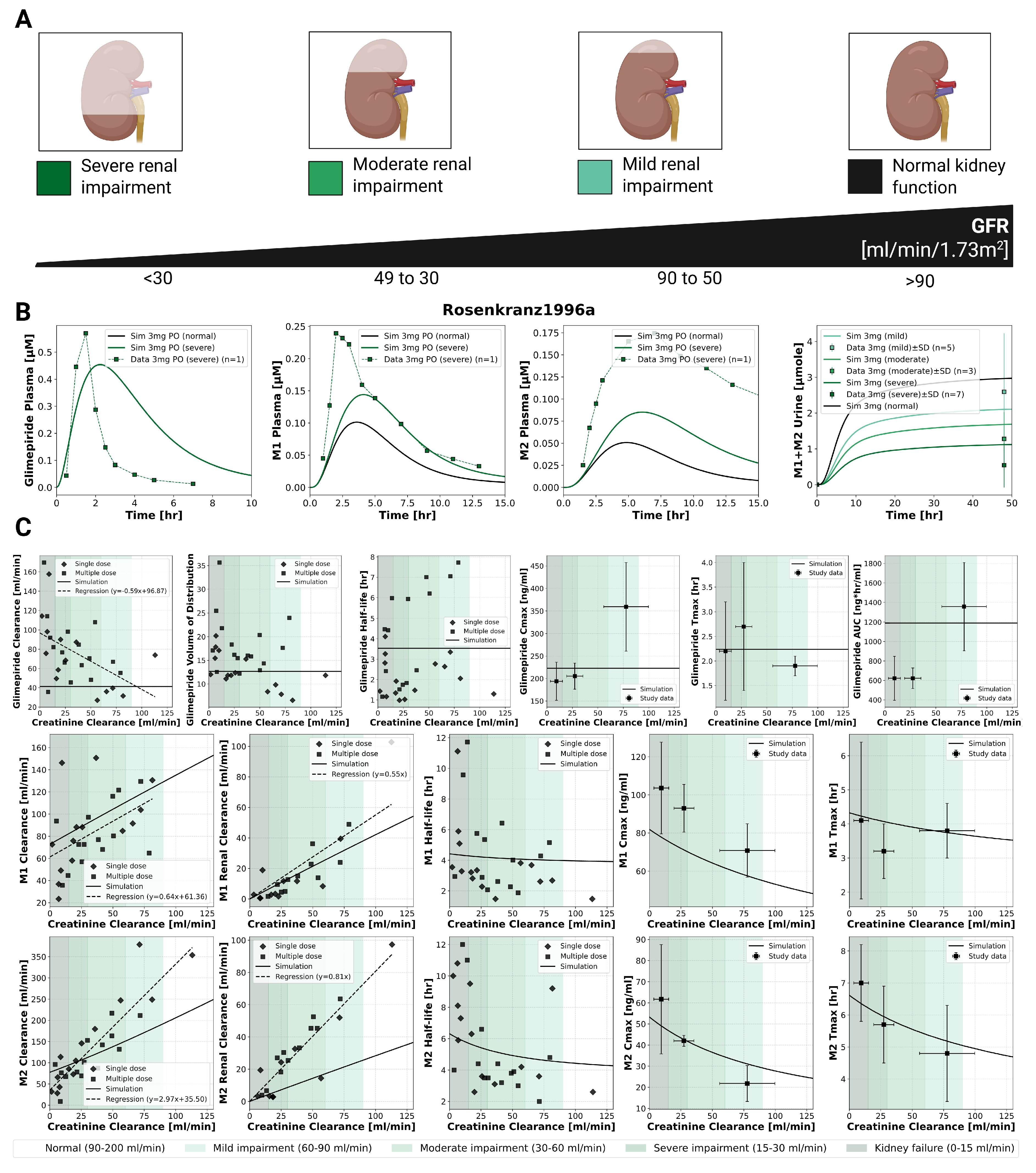

2.4. Renal Impairment

The model incorporated four categories of renal function based on glomerular filtration rate [mL/min/1.73m

2]: normal (>90), mild impairment (50–90), moderate impairment (30–49), and severe impairment (<30). Renal dysfunction primarily affected metabolite clearance with unchanged parent drug exposure (

Figure 3). Simulations accurately reproduced clinical observations from Rosenkranz1996a [

12], showing unchanged glimepiride pharmacokinetics from normal function to severe impairment. In contrast, metabolites M1 and M2 showed progressive accumulation with worsening renal function, with metabolites AUC increasing and clearance decreasing proportionally. This effect confirms the unchanged dosing requirements in renal impairment, though M1 accumulation may be relevant for any residual pharmacological activity.

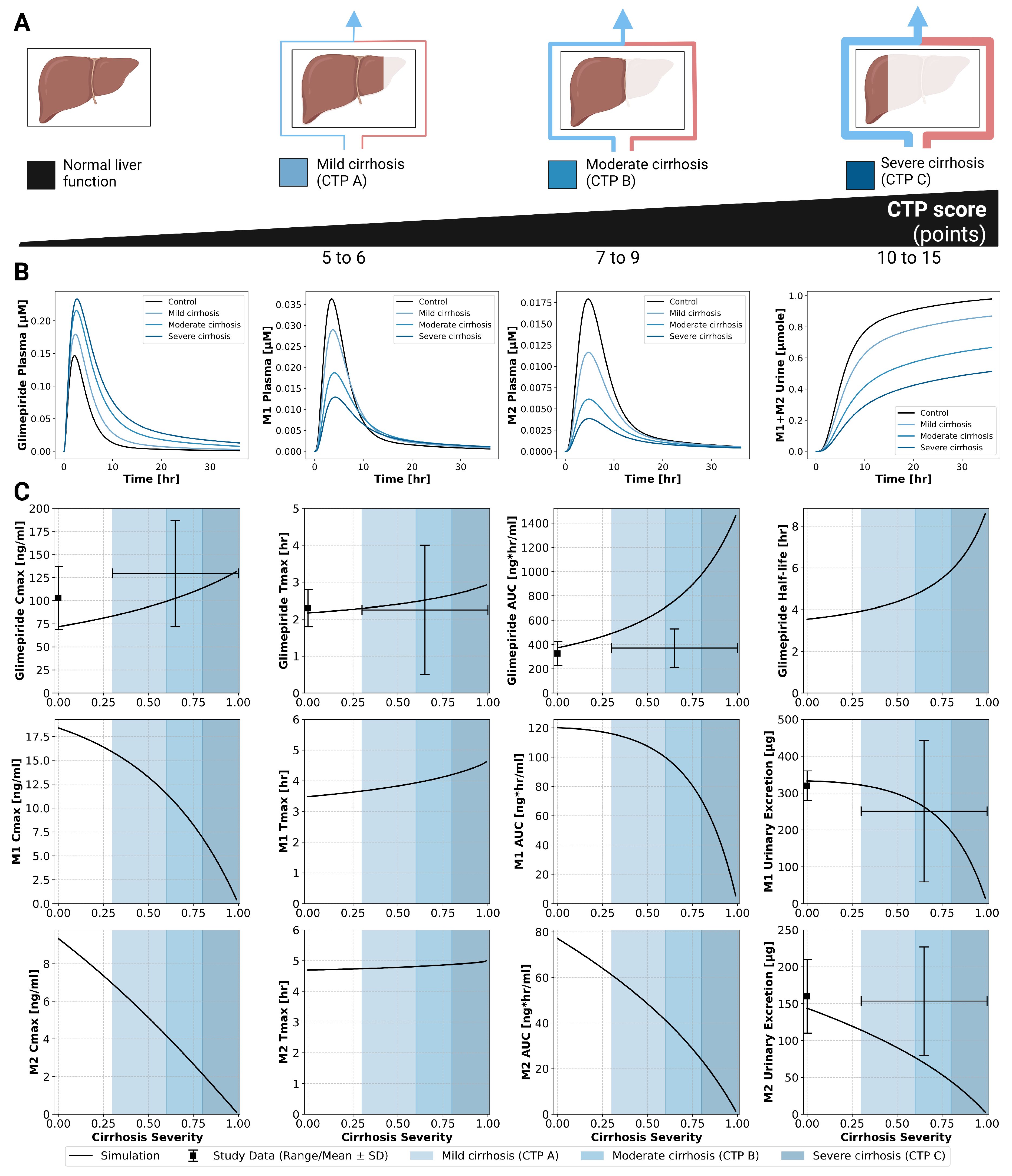

2.5. Hepatic Impairment

The model incorporated Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) classifications: CTP A (mild cirrhosis, 5–6 points), CTP B (moderate cirrhosis, 7–9 points), and CTP C (severe cirrhosis, 10–15 points). Hepatic dysfunction demonstrated a strong impact on parent drug exposure (

Figure 4). Model predictions matched limited clinical data, showing progressive increases in glimepiride concentrations with worsening liver function. C

max nearly doubled from 75 ng/mL in normal function to 125 ng/mL in severe cirrhosis, while AUC increased even more substantially by approximately 3.5-fold. Conversely, metabolite concentrations decreased greatly, reflecting reduced CYP2C9-mediated metabolism due to liver impairment. Comparison with limited clinical data from Rosenkranz1996 [

11] showed reasonable agreement. These findings strongly support dose reduction recommendations in hepatic impairment.

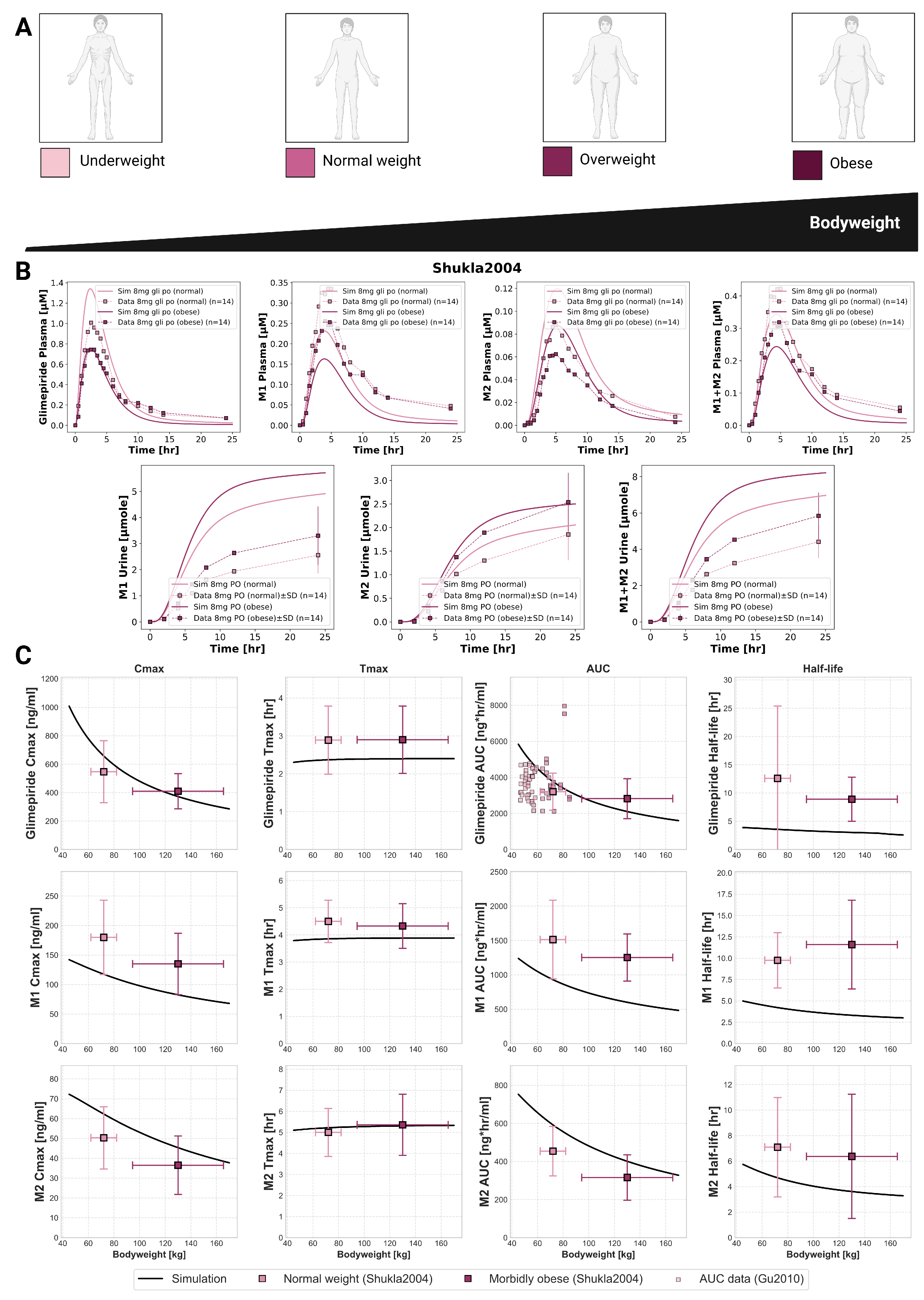

2.6. Bodyweight Dependency

An inverse relationship between bodyweight and systemic exposure was confirmed through simulations across a wide weight range (40–170 kg) and compared against clinical studies (

Figure 5). Glimepiride C

max decreased from 1000 ng/mL at 40 kg to 300 ng/mL at 170 kg, while AUC declined from 6000 to approximately 2000 ng*hr/mL. Despite these exposure changes, T

max and half-life remained stable across the weight range. Model predictions accurately captured observed differences between normal-weight and morbidly obese patients in Shukla2004 [

31], with peak concentrations of 1.4

g/mL in normal-weight versus 0.8

g/mL in obese individuals following an 8 mg dose. Metabolites showed similar behavior. Additional comparison using AUC data from Gu2010 [

33] further confirmed the model’s accuracy. These findings show exposure differences that may explain variable glycemic responses in obese patients, suggesting bodyweight may be an underappreciated factor in dosing practices.

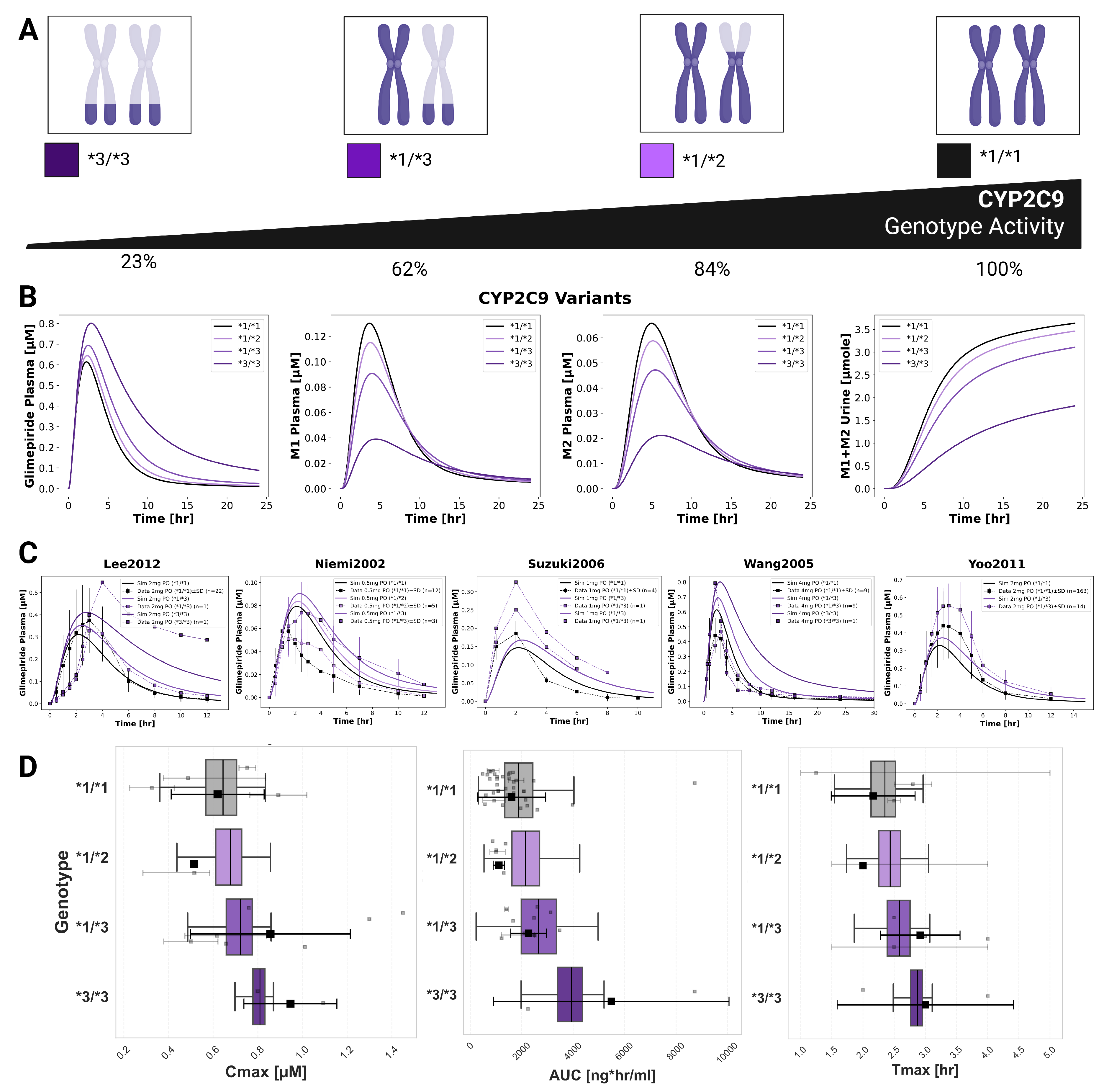

2.7. CYP2C9 Polymorphisms

CYP2C9 genetic polymorphisms showed the most pronounced impact on individual pharmacokinetics (

Figure 6). The model incorporated allele-specific enzyme activities (*1=100%, *2=68%, *3=23%), resulting in diplotype activities of 100% (*1/*1), 84% (*1/*2), 62% (*1/*3), and 23% (*3/*3). Simulations accurately captured substantially increased glimepiride exposure in carriers of reduced-function alleles with *3/*3 homozygotes showing up to 2.5-fold higher AUC compared to wild-type carriers. Metabolites displayed inverse patterns, with reduced formation and excretion in poor metabolizers. Model predictions demonstrated good agreement across five clinical studies (Lee2012 [

25], Yoo2011 [

8], Niemi2002 [

30], Suzuki2006 [

10], Wang2005 [

32]) with doses ranging from 0.5 to 4 mg. A probabilistic modeling approach was implemented to capture inter-individual variability within genotypes, providing more realistic distributions than fixed scaling factors. This approach successfully reproduced the observed variability in pharmacokinetic parameters across genotypes.

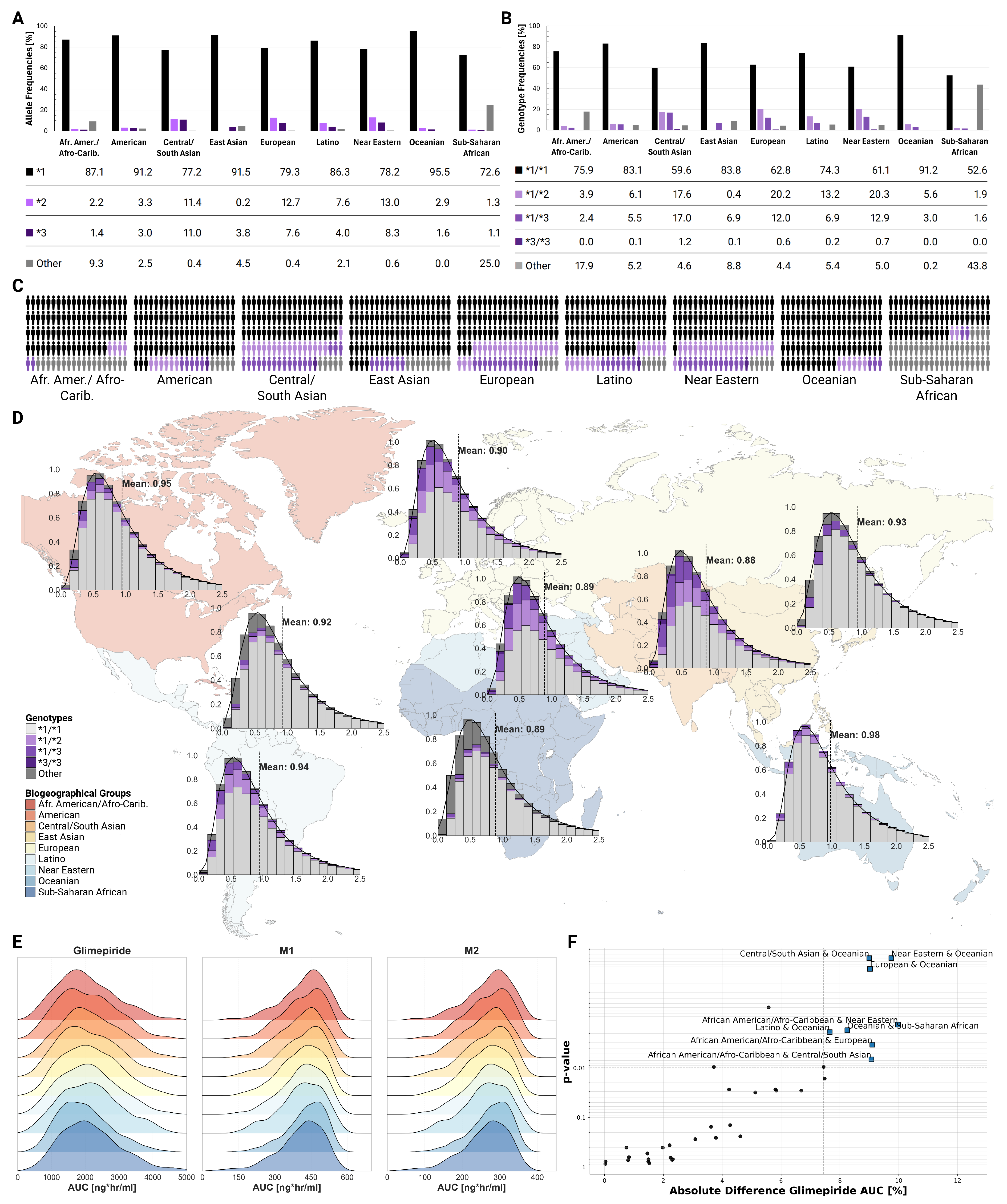

2.8. Populations

Population-level simulations incorporating known genotype frequencies across biogeographical groups revealed modest differences in average CYP2C9 activity and pharmacokinetic parameters between populations, despite varying genotype frequencies (

Figure 7). The *2 allele showed highest frequencies in European (12.7%) and Central/South Asian (11.4%) populations, while the *3 allele was most prevalent in Central/South Asians (11.0%). Mean CYP2C9 activity ranged from 0.88 in Central/South Asian to 0.98 in Oceanian populations. Despite these differences in genetic makeup, ridgeline plots of AUC distributions showed substantial overlap across all populations. While Kolmogorov-Smirnov testing identified statistically significant differences between certain population pairs (e.g., bCentral/South Asian and Oceanian, Near Eastern and Oceanian, European and Oceanian; all p<0.01), the clinical magnitude remained small with mean differences less than 10%.

3. Methods

3.1. Systematic Literature Research and Data Curation

A systematic literature search was conducted for studies reporting glimepiride pharmacokinetic data. PubMed was searched using the keywords

glimepiride AND pharmacokinetics, and the PKPDAI database [

35] was queried on 2024-08-30. Inclusion criteria focused on clinical trials involving healthy volunteers or patients with T2DM, and studies investigating the effects of renal impairment, hepatic impairment, bodyweight variations, or CYP2C9 genotypes on glimepiride pharmacokinetics. Studies involving pediatric populations, non-human subjects, or with insufficiently reported pharmacokinetic data were excluded. The systematic review also included

in vitro studies providing kinetic parameters (particularly CYP2C9 activity) required for PBPK model development. The literature review process yielded 19 clinical studies for analysis.

Data from these selected studies were systematically curated and uploaded to the open pharmacokinetics database PK-DB

[

36]. Patient-specific information (e.g., age, sex, comorbidities, dosing regimens, pharmacokinetic profiles) was extracted following established curation protocols [

36]. Figure-based pharmacokinetic data were digitized using WebPlotDigitizer [

37], while tabular and textual data were reformatted according to standardized guidelines [

36]. Curated data encompassed cohort characteristics, individual-level data, intervention details, time-course concentration profiles of glimepiride and its metabolites, and reported pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters. This dataset formed the basis for PBPK model development, calibration, and validation, and is publicly accessible via PK-DB to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

3.2. Computational Model

The PBPK model and tissue-specific submodels were developed using the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) [

38,

39]. Programming and visualization of the models were performed using the

sbmlutils [

40] and

cy3sbml [

41] libraries. Numerical solutions for the ordinary differential equations (ODEs) underlying the model were computed using

sbmlsim [

42], powered by the high-performance SBML simulation engine

libRoadRunner [

43,

44].

The developed model comprises a whole-body framework with submodels for the intestine, liver, and kidney to characterize glimepiride’s ADME processes. Key processes include oral dissolution and first-order absorption in the intestine, CYP2C9-mediated hepatic metabolism of glimepiride to M1 followed by further metabolism to M2, and renal excretion of M1 and M2. The mathematical descriptions and ODEs for all submodels are provided in

Supplementary Equations S1.1–S1.3. The model and all associated materials (simulation scripts, parameters, and documentation) are publicly available in SBML format under a CC-BY 4.0 license at

https://github.com/matthiaskoenig/glimepiride-model, version

0.6.1 [

45].

The model was designed to incorporate several key factors influencing inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability.

Renal impairment was addressed using the parameter

frenal_function (1.0 for normal function), with scaling factors for mild (0.6), moderate (0.35), and severe (0.2) impairment derived from KDIGO guidelines [

46] and the approach of Stemmer-Mallol et al. [

47]. This parameter directly scales M1 and M2 metabolite renal excretion rates.

Hepatic impairment was implemented via the

fcirrhosis parameter (ranging from 0.0 for normal function to 1.0 for severe impairment), with values mapped to the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) classification [

48,

49,

50]. This parameter modifies the fraction of functional liver parenchyma and the extent of blood shunting around the liver.

Tissue distribution of glimepiride and its metabolites was described via the parameters

ftissuegli (rate of tissue distribution) and

Kpgli (tissue-plasma partition coefficient), assuming similar distribution properties for the parent drug and metabolites to reduce model complexity.

Bodyweight effects were incorporated by scaling organ volumes, blood flows, and metabolic rates according to allometric relationships.

CYP2C9 genetic variability was modeled based on allele-specific scaling factors for the common alleles ⁎1 (wild-type, activity 1.0), ⁎2 (activity 0.68), and ⁎3 (activity 0.23), derived from

in vitro data [

51,

52,

53]. Genotype-specific activities were calculated as the mean of the two constituent allele activities. These genetic factors were implemented via the parameter

fcyp2c9, which modulates the maximal velocity (

) of glimepiride conversion to M1. The Michaelis constant (

GLI2M1Km_gli) was parameterized using literature values [

10,

52,

54]. For population-level simulations, observed intrinsic clearance (CL

int) distribution for diclofenac (a CYP2C9 substrate) [

55] was characterized using a lognormal function. This distribution shape was retained for modeling allele-specific effects, with the scale parameter adjusted to match the mean activity of each allele. Diplotype activities were calculated as the average contribution of both alleles. Simulations also incorporated published CYP2C9 genotype frequencies across nine biogeographical populations [

34].

3.3. Model Parameterization

Key model parameters related to glimepiride’s absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion were optimized by minimizing a weighted sum of squared residuals between model predictions and a curated dataset from clinical studies in healthy, fasted subjects. This optimization utilized multiple (n=100) runs of a local optimization algorithm. The model was optimized using a subset of the curated clinical data (healthy and fasted), achieving successful convergence and demonstrating good predictive performance across the datasets (see

supplementary Figure S2). The optimized model successfully captured glimepiride pharmacokinetics with satisfactory goodness-of-fit, though some inter-study variability was observed, likely reflecting differences in study design and population characteristics. Final optimized parameters are provided in the

supplementary Table S1. Following parameterization, the model’s predictive performance was evaluated across diverse physiological and pathological conditions.

3.4. Pharmacokinetic Parameters

Standard pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from simulated and observed concentration-time profiles using standard non-compartmental analysis methods. Simulated profiles and derived PK parameters were then compared against the curated experimental data from all 19 clinical studies.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed a whole-body PBPK model as a digital twin for glimepiride, mechanistically integrating key patient-specific factors like organ function, bodyweight, and CYP2C9 genetics. Assessed against diverse clinical data, the model provides a quantitative framework to explore the drivers of pharmacokinetic variability and support personalized dosing strategies for type 2 diabetes.

The digital twin quantifies the influence of various patient factors, enabling patient stratification. It provides a quantitative platform that guides the personalization of glimepiride therapy and helps determine when an adjusted initial dosage is necessary to ensure patient safety.

While our model confirms that glimepiride exposure is unaffected by renal impairment, it highlights the clinical significance of metabolite accumulation. The progressive buildup of the active M1 metabolite, which retains partial hypoglycemic activity, suggests a risk of prolonged adverse effects in patients with severe renal dysfunction. Therefore, although glimepiride dose adjustments may not be required, enhanced glycemic monitoring is warranted in this population.

In contrast to renal function, hepatic impairment dramatically increased glimepiride exposure by hindering its CYP2C9-mediated metabolism. Standard doses in patients with moderate to severe cirrhosis could lead to a significant risk of hypoglycemia. Current clinical guidelines are qualitative, only advising caution. Our digital twin provides a quantitative tool that addresses this issue by enabling in silico evaluation of dose adjustments needed to maintain safety in this vulnerable population.

The model demonstrated an inverse relationship between bodyweight and glimepiride exposure, showing how systemic drug concentrations change with body size. This understanding supports the current clinical practice, where this level of variability is effectively managed by titrating the dose according to a patient’s glycemic response, rather than adhering to a strict weight-based protocol.

CYP2C9 genetic polymorphism substantially influences glimepiride exposure. Individuals with reduced-function alleles are at a higher risk of experiencing adverse events from a standard dose. However, our analysis shows substantial pharmacokinetic variability even within the same genotype group. This indicates that genotype alone is not a good predictor of patient response. Furthermore, although genotype effects were evident at the individual level, the model predicted only modest differences in pharmacokinetics across biogeographical populations. Therefore, ethnicity alone provides limited value for guiding dosing decisions.

A key strength of this PBPK approach is its ability to integrate multiple patient factors simultaneously. Unlike traditional studies that often isolate single variables, our integrated model more accurately reflects the complex clinical reality where patients present with multiple conditions affecting drug disposition. This framework is especially valuable for evaluating pharmacokinetic risks in underrepresented populations or complex scenarios where clinical evidence is lacking, providing a robust platform to support dosing decisions.

The model’s development was constrained by the limited availability of public pharmacokinetic data, particularly for metabolite disposition. For instance, quantitative data on metabolite elimination pathways and the specific enzymes responsible for M1-to-M2 conversion are sparse. During optimization, certain parameters reached their constraint boundaries, suggesting areas where model structure could be refined with future data. Despite these limitations, the model provided physiologically reasonable predictions across diverse clinical conditions, and the curated dataset formed an adequate basis for characterizing glimepiride’s core pharmacokinetic properties.

In conclusion, this study presents a digital twin of glimepiride which successfully quantifies the impact of genetics, organ function, and physiology on pharmacokinetic variability. This PBPK model lays the basis for future clinical decision support tools that can guide personalized initial dosing, especially for patients with high-risk profiles. Future work should focus on refining the model using larger population studies and expanding its application to include pharmacodynamics between drug exposure and glycemic response. As precision medicine advances, such digital twin approaches have the clear potential to become valuable tools for optimizing drug therapy in complex diseases like type 2 diabetes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on

Preprints.Org.

Acknowledgments

Matthias König (MK) was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, Germany) within LiSyM by grant number 031L0054. MK, HMT and BSM were supported by the BMBF within ATLAS by grant number 031L0304B. MK and HMT was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the Research Unit Program FOR 5151 "QuaLiPerF (Quantifying Liver Perfusion-Function Relationship in Complex Resection - A Systems Medicine Approach)" by grant number 436883643 and by grant number 465194077 (Priority Programme SPP 2311, Subproject SimLivA). This work was supported by the BMBF-funded de.NBI Cloud within the German Network for Bioinformatics Infrastructure (de.NBI) (031A537B, 031A533A, 031A538A, 031A533B, 031A535A, 031A537C, 031A534A, 031A532B).

References

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee.; ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Bannuru, R.R.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Ekhlaspour, L.; Gaglia, J.L.; Hilliard, M.E.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: StandardsofCareinDiabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S20–S42. [CrossRef]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Burden of Disease 2021: Findings from the GBD 2021 Study. Technical report, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, 2021.

- Douros, A.; Yin, H.; Yu, O.H.Y.; Filion, K.B.; Azoulay, L.; Suissa, S. Pharmacologic Differences of Sulfonylureas and the Risk of Adverse Cardiovascular and Hypoglycemic Events. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1506–1513. [CrossRef]

- Hartmanshenn, C.; Scherholz, M.; Androulakis, I.P. Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Models: Approaches for Enabling Personalized Medicine. Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics 2016, 43, 481–504. [CrossRef]

- McCall, A.L. Clinical Review of Glimepiride. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2001, 2, 699–713. [CrossRef]

- Langtry, H.D.; Balfour, J.A. Glimepiride. A Review of Its Use in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Drugs 1998, 55, 563–584. [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, F. Mechanisms of the Glycaemic Effects of Sulfonylureas. Hormone and Metabolic Research 1996, 28, 456–463. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.D.; Kim, M.S.; Cho, H.Y.; Lee, Y.B. Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Glimepiride with CYP2C9 Genetic Polymorphism in Healthy Korean Subjects. European journal of clinical pharmacology 2011, 67, 889–898. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Glimepiride Drug Label – FDA Approved Information. Technical report, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 1995.

- Suzuki, K.; Yanagawa, T.; Shibasaki, T.; Kaniwa, N.; Hasegawa, R.; Tohkin, M. Effect of CYP2C9 Genetic Polymorphisms on the Efficacy and Pharmacokinetics of Glimepiride in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2006, 72, 148–154. [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, B. Pharmacokinetic Basis for the Safety of Glimepiride in Risk Groups of NIDDM Patients. Hormone and Metabolic Research = Hormon- Und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones Et Metabolisme 1996, 28, 434–439. [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, B.; Profozic, V.; Metelko, Z.; Mrzljak, V.; Lange, C.; Malerczyk, V. Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Glimepiride at Clinically Effective Doses in Diabetic Patients with Renal Impairment. Diabetologia 1996, 39, 1617–1624. [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.Y.; Park, H.C.; Kang, W.; Kwon, K.I. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Modelling of the Effects of Glimepiride on Insulin Secretion and Glucose Lowering in Healthy Humans. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics 2006, 31, 469–476. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, H.F.; Liu, C.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.D. Prediction of Drug Disposition in Diabetic Patients by Means of a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2015, 54, 179–193. [CrossRef]

- Berton, M.; Bettonte, S.; Stader, F.; Battegay, M.; Marzolini, C. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling to Identify Physiological and Drug Parameters Driving Pharmacokinetics in Obese Individuals. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2023, 62, 277–295. [CrossRef]

- Sager, J.E.; Yu, J.; Ragueneau-Majlessi, I.; Isoherranen, N. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling and Simulation Approaches: A Systematic Review of Published Models, Applications, and Model Verification. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2015, 43, 1823–1837. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, F.; Läer, S. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling: Methodology, Applications, and Limitations with a Focus on Its Role in Pediatric Drug Development. BioMed Research International 2011, 2011, 907461. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.A.; El-Say, K.M.; Aljaeid, B.M.; Fahmy, U.A.; Abd-Allah, F.I. Transdermal Glimepiride Delivery System Based on Optimized Ethosomal Nano-Vesicles: Preparation, Characterization, in Vitro, Ex Vivo and Clinical Evaluation. International journal of pharmaceutics 2016, 500, 245–254. [CrossRef]

- Badian, M.; Korn, A.; Lehr, K.H.; Malerczyk, V.; Waldhäusl, W. Absolute Bioavailability of Glimepiride (Amaryl) after Oral Administration. Drug metabolism and drug interactions 1994, 11, 331–339. [CrossRef]

- Badian, M.; Korn, A.; Lehr, K.H.; Malerczyk, V.; Waldhäusl, W. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of the Hydroxymetabolite of Glimepiride (Amaryl) after Intravenous Administration. Drug metabolism and drug interactions 1996, 13, 69–85. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, S.H.; Bang, K.; Han, S.; Lim, H.S.; Bae, K.S. Evaluation of Pharmacokinetic Drug Interactions between Gemigliptin (Dipeptidylpeptidase-4 Inhibitor) and Glimepiride (Sulfonylurea) in Healthy Volunteers. Drugs in R&D 2014, 14, 165–176. [CrossRef]

- Helmy, S.A.; El Bedaiwy, H.M.; Mansour, N.O. Dose Linearity of Glimepiride in Healthy Human Egyptian Volunteers. Clinical pharmacology in drug development 2013, 2, 264–269. [CrossRef]

- Kasichayanula, S.; Liu, X.; Shyu, W.C.; Zhang, W.; Pfister, M.; Griffen, S.C.; Li, T.; LaCreta, F.P.; Boulton, D.W. Lack of Pharmacokinetic Interaction between Dapagliflozin, a Novel Sodium-Glucose Transporter 2 Inhibitor, and Metformin, Pioglitazone, Glimepiride or Sitagliptin in Healthy Subjects. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 2011, 13, 47–54. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.O.; Oh, E.S.; Kim, H.; Park, M.S. Pharmacokinetic Interactions between Glimepiride and Rosuvastatin in Healthy Korean Subjects: Does the SLCO1B1 or CYP2C9 Genetic Polymorphism Affect These Drug Interactions? Drug design, development and therapy 2017, 11, 503–512. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Lim, M.s.; Lee, J.; Jegal, M.Y.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, W.K.; Jang, I.J.; Shin, J.G.; Yoon, Y.R. Frequency of CYP2C9 Variant Alleles, Including CYP2C9*13 in a Korean Population and Effect on Glimepiride Pharmacokinetics. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics 2012, 37, 105–111. [CrossRef]

- Lehr, K.H.; Damm, P. Simultaneous Determination of the Sulphonylurea Glimepiride and Its Metabolites in Human Serum and Urine by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography after Pre-Column Derivatization. Journal of chromatography 1990, 526, 497–505. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.q.; Zhu, J.m.; Jia, J.y.; Liu, Y.m.; Liu, G.y.; Li, S.; Weng, L.p.; Yu, C. Bioequivalence and Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of Two Formulations of Glimepiride 2 Mg: A Single-Dose, Randomized-Sequence, Open-Label, Two-Way Crossover Study in Healthy Chinese Male Volunteers. Clinical therapeutics 2010, 32, 986–995. [CrossRef]

- Malerczyk, V.; Badian, M.; Korn, A.; Lehr, K.H.; Waldhäusl, W. Dose Linearity Assessment of Glimepiride (Amaryl) Tablets in Healthy Volunteers. Drug metabolism and drug interactions 1994, 11, 341–357. [CrossRef]

- Matsuki, M.; Matsuda, M.; Kohara, K.; Shimoda, M.; Kanda, Y.; Tawaramoto, K.; Shigetoh, M.; Kawasaki, F.; Kotani, K.; Kaku, K. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Glimepiride in Type 2 Diabetic Patients: Compared Effects of Once- versus Twice-Daily Dosing. Endocrine journal 2007, 54, 571–576. [CrossRef]

- Niemi, M.; Cascorbi, I.; Timm, R.; Kroemer, H.K.; Neuvonen, P.J.; Kivistö, K.T. Glyburide and Glimepiride Pharmacokinetics in Subjects with Different CYP2C9 Genotypes. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2002, 72, 326–332. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, U.A.; Chi, E.M.; Lehr, K.H. Glimepiride Pharmacokinetics in Obese versus Non-Obese Diabetic Patients. The Annals of pharmacotherapy 2004, 38, 30–35. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, K.; Wen, S.y.; Li, J.; Wang, S.q. Pharmacokinetics of Glimepiride and Cytochrome P450 2C9 Genetic Polymorphisms. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2005, 78, 90–92. [CrossRef]

- Gu, N.; Kim, B.H.; Rhim, H.; Chung, J.Y.; Kim, J.R.; Shin, H.S.; Yoon, S.H.; Cho, J.Y.; Shin, S.G.; Jang, I.J.; et al. Comparison of the Bioavailability and Tolerability of Fixed-Dose Combination Glimepiride/Metformin 2/500-Mg Tablets versus Separate Tablets: A Single-Dose, Randomized-Sequence, Open-Label, Two-Period Crossover Study in Healthy Korean Volunteers. Clinical therapeutics 2010, 32, 1408–1418. [CrossRef]

- Gene-Specific Information Tables for CYP2C9. https://www.pharmgkb.org/page/cyp2c9RefMaterials.

- Gonzalez Hernandez, F.; Carter, S.J.; Iso-Sipilä, J.; Goldsmith, P.; Almousa, A.A.; Gastine, S.; Lilaonitkul, W.; Kloprogge, F.; Standing, J.F. An Automated Approach to Identify Scientific Publications Reporting Pharmacokinetic Parameters. Wellcome Open Research 2021, 6, 88. [CrossRef]

- Grzegorzewski, J.; Brandhorst, J.; Green, K.; Eleftheriadou, D.; Duport, Y.; Barthorscht, F.; Köller, A.; Ke, D.Y.J.; De Angelis, S.; König, M. PK-DB: Pharmacokinetics Database for Individualized and Stratified Computational Modeling. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D1358–D1364. [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer, 2024.

- Hucka, M.; Bergmann, F.T.; Chaouiya, C.; Dräger, A.; Hoops, S.; Keating, S.M.; König, M.; Novère, N.L.; Myers, C.J.; Olivier, B.G.; et al. The Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML): Language Specification for Level 3 Version 2 Core Release 2. Journal of Integrative Bioinformatics 2019, 16. [CrossRef]

- Keating, S.M.; Waltemath, D.; König, M.; Zhang, F.; Dräger, A.; Chaouiya, C.; Bergmann, F.T.; Finney, A.; Gillespie, C.S.; Helikar, T.; et al. SBML Level 3: An Extensible Format for the Exchange and Reuse of Biological Models. Molecular Systems Biology 2020, 16, e9110. [CrossRef]

- König, M. Sbmlutils: Python Utilities for SBML. Zenodo, 2024. [CrossRef]

- König, M.; Dräger, A.; Holzhütter, H.G. CySBML: A Cytoscape Plugin for SBML. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2402–2403. [CrossRef]

- König, M. Sbmlsim: SBML Simulation Made Easy. [object Object], 2021. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, C.; Xu, J.; Smith, L.; König, M.; Choi, K.; Sauro, H.M. libRoadRunner 2.0: A High Performance SBML Simulation and Analysis Library. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac770. [CrossRef]

- Somogyi, E.T.; Bouteiller, J.M.; Glazier, J.A.; König, M.; Medley, J.K.; Swat, M.H.; Sauro, H.M. libRoadRunner: A High Performance SBML Simulation and Analysis Library. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3315–3321. [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.; König, M. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Model of Glimepiride. Zenodo, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International 2024, 105, S117–S314. [CrossRef]

- Mallol, B.S.; Grzegorzewski, J.; Tautenhahn, H.M.; König, M. Insights into Intestinal P-glycoprotein Function Using Talinolol: A PBPK Modeling Approach, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Child, C.G.; Turcotte, J.G. Surgery and Portal Hypertension. Major Problems in Clinical Surgery 1964, 1, 1–85.

- Infante-Rivard, C.; Esnaola, S.; Villeneuve, J.P. Clinical and Statistical Validity of Conventional Prognostic Factors in Predicting Short-Term Survival among Cirrhotics. Hepatology 1987, 7, 660–664. [CrossRef]

- Köller, A.; Grzegorzewski, J.; Tautenhahn, H.M.; König, M. Prediction of Survival After Partial Hepatectomy Using a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model of Indocyanine Green Liver Function Tests. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12, 730418. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Xiong, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, S.; Xiong, Y.; Hu, X.; Xia, C. CYP2C9 and OATP1B1 Genetic Polymorphisms Affect the Metabolism and Transport of Glimepiride and Gliclazide. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 10994. [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, K.; Harakawa, N.; Sugiyama, E.; Tohkin, M.; Kim, S.R.; Kaniwa, N.; Katori, N.; Hasegawa, R.; Yasuda, K.; Kamide, K.; et al. Substrate-Dependent Functional Alterations of Seven CYP2C9 Variants Found in Japanese Subjects. Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals 2009, 37, 1895–1903. [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.P.; Wang, S.H.; Geng, P.W.; Hu, G.X.; Cai, J.P. InVitro Assessment of 36 CYP 2 C 9 Allelic Isoforms Found in the C Hinese Population on the Metabolism of Glimepiride. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology 2014, 114, 305–310. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Qi, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, F.; Zou, L.; Zhou, Q.; Geng, P.; Hong, Y.; Yang, H.; Luo, Q.; et al. Identification and in Vitro Functional Assessment of 10 CYP2C9 Variants Found in Chinese Han Subjects. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2023, 14, 1139805. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; He, M.M.; Niu, W.; Wrighton, S.A.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, C. Metabolic Capabilities of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Chinese Liver Microsomes Compared with Those in Caucasian Liver Microsomes. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2012, 73, 268–284. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).