1. Introduction

Every aspect of animal physiology and behavior is influenced by circadian rhythms, which enable organisms to anticipate and adapt to predictable environmental changes. In mammals, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) functions as the central pacemaker, coordinating the synchronization of peripheral clocks [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Several oscillatory structures are also present within the central nervous system (CNS), among which the hippocampus plays a pivotal role in modulating daily variations in learning and memory efficiency [

5]. Within this structure, the muscarinic cholinergic system (MChS) is fundamental to the neural circuitry underlying learning and memory processes [

6,

7,

8,

9].

The activity of the MChS in mammals exhibits a pronounced circadian rhythm. Acetylcholine (ACh) is predominantly released during wakefulness, which is why it is considered a wakefulness-associated neurotransmitter [

10]. Two primary approaches are commonly used to analyze ACh in the CNS: one involves quantifying ACh release through microdialysis assays, and the other measures ACh content in tissue extracts. Studies assessing ACh release in the hippocampus, cortex, and other central structures of rats have consistently demonstrated a positive correlation with periods of behavioral activity [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. In contrast, measurements of ACh in rat hippocampal and cortical tissue extracts have shown an inverse relationship with activity, with the highest levels occurring during the light period [

16,

17,

18].

Regarding muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs), several reports indicate that they exhibit circadian rhythmicity, although findings on the timing of peak expression are inconsistent, with peaks reported during both the light and dark periods [

10,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Despite analyses across different strains, species, and brain regions, most studies suggest a higher number of mAChRs during the animals’ rest periods. It is important to note that these studies are relatively old and methodologically limited, typically analyzing only a few time points per day and often employing a single radioligand concentration in binding assays.

mAChRs are G-protein-coupled receptors classified into five subtypes (M

1–M

5) based on their structure and the second messenger pathways to which they are coupled. Specifically, M

2 and M

4 subtypes are generally linked to the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and a reduction in cAMP, thereby negatively regulating ACh release, whereas M

1, M

3, and M

5 are stimulatory, associated with increased intracellular calcium and inositol triphosphate (IP3) levels [

8]. The M

1 subtype, through activation of MAP kinase pathways, contributes to long-term changes in gene expression underlying learning and memory processes [

23].

All five mAChR subtypes are expressed in the CNS with distinct regional distributions [

8,

24,

25]. In the hippocampus, immunoprecipitation studies indicate a predominance of the M

1 subtype (55%), with lower levels of M

2 (12%), M

3 (11%), M

4 (16%), and only mRNA detected for the M

5 subtype [

24].

Hippocampal mAChRs are closely associated with learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity, with each subtype exerting specific functional roles. Postsynaptic localization has been reported for M

1 and M

3 receptors on principal hippocampal neurons, whereas M

2 and M

4 receptors are predominantly presynaptic. M

2 receptors, in particular, are considered the primary cholinergic autoreceptors on septohippocampal nerve terminals, inhibiting ACh release and thereby critically modulating cholinergic tone [

8,

25,

26].

Neurodegenerative processes, such as Alzheimer’s disease, are associated with deficits in cholinergic neurotransmission, primarily affecting the hippocampus and cortex. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are commonly used to counteract impaired ACh release, as the development of selective agonists for specific mAChR subtypes is challenging due to the high conservation of orthosteric binding sites among mAChRs [

23].

Circadian modulation of learning and memory efficiency is an evolutionarily conserved phenomenon, observed across organisms ranging from invertebrates to higher mammals, including humans. The hippocampus exhibits intrinsic oscillatory capabilities, with clock genes such as

Per1,

Per2,

Clock, and

Bmal rhythmically expressed in this structure, which has functional implications for synaptic plasticity and behavior [

1,

5,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Given the critical role of mAChRs in learning and memory, and their modulation by the circadian system, the objective of this study was to characterize daily variations in hippocampal mAChR expression. This involved assessing both the total receptor quantity and binding affinity across a 24-hour cycle at 4-hour intervals (Zeitgeber times: ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22) using a radioligand binding approach. In addition, the expression of the five mAChR subtypes (M1–M5) was examined at two specific time points, ZT2 and ZT14, corresponding to the light and dark periods, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

Animals

Male and female Wistar rats were supplied and housed in the vivarium room of the Neurobiology Laboratory at the Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of São Paulo, in polypropylene boxes (4 animals per box). They were kept in rooms with controlled lighting (light/dark cycle of 12h/12h) and temperature (21±3ºC), along with an exhaust system, with water and food provided ad libitum (rodent food - Nuvilab CR1®). Two rooms were utilized: one with an inverted light cycle, where the animals euthanized during the dark phase were placed (Zeitgeber Times: 14, 18, and 22), with lights turned on at 19:00 h; and another room with a normal cycle, housing the animals euthanized during the light phase (Zeitgeber Times: 2, 6, and 10), with lights turned on at 07:00 h. The project received approval from the Animal Use Ethics Committee (CEUA) of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences at the University of São Paulo (ICB-USP) under CEUA no. 9805191021, and the experimental protocol adhered to all standards established by CONCEA.

Experimental Procedure

Male and female rats were housed in the vivarium until they reached 90 days of age, at which point they were euthanized every 4 hours over a 24-hour period, specifically at the Zeitgeber Times (ZTs): 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 corresponded to the light phase, while ZTs 14, 18, and 22 were during the dark phase. ZT stands for “zeitgeber time”, which refers to the light-dark cycle, with ZT=0 marking the start of the light period. The hippocampi were then dissected, isolated, and preserved for the analysis of mAChR expression.

Hippocampal Membrane Preparation

Hippocampal membranes were prepared from 5 animals at each time point (ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18 and 22) across all experiments, following the protocol established by Cardoso et al. [

31]. Briefly, the entire hippocampus was isolated, minced, and homogenized in 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 (buffer: 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride-PMSF; with the addition of 0.3 M sucrose) using an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (T-25, Ika Labortechnik, Staufen, Germany). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was filtered through two layers of gauze and subsequently centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 min. The final pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, with a Dounce homogenizer, and stored at -80 °C. All procedures were conducted at 4 °C. Protein concentration was measured using a BioRad protein assay, with BSA as the standard (Bio Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

[3H]Quinuclidinyl Benzilate ([3H] QNB) Binding Assay

In saturation binding experiments [

31], hippocampal membranes (100 µg protein) were incubated with 0.02 - 2.0 nM [

3H]QNB, a subtype-nonselective antagonist with high affinity and very slow dissociation (specific activity 80.0 Ci/mmol; American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA), both in the absence (total binding) and presence (nonspecific binding) of 1 µM atropine for 1 h at 30 °C. Following incubation, the binding reaction was halted by cooling on ice and rapidly filtered through GF/B glass fiber filters (Whatman International Ltd., Maidstone, UK) under vacuum. The filters were washed three times with ice-cold buffer, partially dried under vacuum, and placed in vials containing OptiPhase HiSafe 3 (Perkin Elmer, Loughborough Leics., UK) scintillation liquid. The amount of radioactivity was measured using a liquid scintillation counter (Perkin Elmer Tri-Carb 5110TR, USA). Specific binding was calculated as the difference between total and nonspecific binding. Nonspecific binding, near the K

D value, accounted for approximately 10% of total [

3H]QNB binding (data not shown). Saturation binding data were analyzed using the weighted nonlinear least-squares interactive curve-fitting program GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Prism Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A mathematical model for one or two binding sites was employed. The equilibrium dissociation constant (K

D) and the binding capacity (B

max) were determined from a specific saturation hyperbola [

32].

Immunoprecipitation Assays for Detection of mAChR Subtypes

Hippocampal membranes (100 µg, in duplicate) from male and female rats at ZT 2 and ZT 14 were radiolabeled with 1.5 nM of [3H]QNB (the maximum binding obtained in saturation binding experiments) in the absence (total binding) and presence of 1 µM atropine (nonspecific binding) for 1 h at 30 °C. The binding reaction was halted by cooling on ice and rapidly filtering through GF/B glass fiber under vacuum. The filters were washed three times with ice-cold buffer, partially dried under vacuum, and placed in scintillation vials containing OptiPhase HiSafe 3. The amount of radioactivity was measured using a scintillation β-counter. Specific binding was calculated as the difference between total and nonspecific binding.

To solubilize the receptors [

33,

34,

35], the membrane preparation (100 µg) (in duplicate) was incubated with 1.5 nM [

3H]QNB in the absence (total binding) and presence of 1 µM atropine (nonspecific binding) for 1 h at 30 °C. [

3H]QNB-receptors were solubilized with digitonin and sodium deoxycholate in a 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4 (containing 0.1% sodium deoxycholate), for 1 h at 4 °C. After this, 0.1% digitonin was added. The sample was incubated for 15 min at 4 °C and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant, which contained the solubilized receptors, was collected and the amount of radioactivity was determined.

The supernatant (100 µl), containing the solubilized receptors, was immunoprecipitated using subtype-specific antibodies. This sample was incubated with 0.5 µg of polyclonal antibodies against goat mAChR subtypes [M1 (C-20, sc 7470), M2 (C-18, sc 7472), M3 (C-20, sc 7474), M4 (C-19, sc 7476), and M5 (C-20, sc 7478), Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA] (specific) or with IgG (nonspecific) (Sigma Co, MO, USA) in a 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, for 4 h at 4 °C. Following this incubation, 20 µl of Pansorbin (Calbiochem, CA, USA) was added and incubated with agitation for 1 h at 4 °C, then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min. The pellet was washed with 200 µl Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, and centrifuged again at 15,000 g for 10 min. The amount of radioactivity was measured in 50 µl of Pansorbin deposit ([3H]QNB-subtype-specific antibodies) (total) or Pansorbin deposit ([3H]QNB-IgG) (nonspecific). The specific immunoprecipitation (the difference between total and nonspecific) was determined, and results were expressed as fmol/mg of protein.

To validate our immunoprecipitation assays, the percentage of specific immunoprecipitation for each mAChR subtype in hippocampal membranes from male rats was calculated by dividing the amount of [

3H]QNB counts in the Pansorbin pellet by the total counts in the supernatant and Pansorbin pellet (Shiozaki et al. 1999) [

35].

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Data were subjected to the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Statistical differences between groups were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Newman-Keuls post-test. Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups. The significance level for rejection of the null hypothesis was set at 5% (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

In mammals, circadian rhythms are generated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, which functions as the master pacemaker and coordinates peripheral oscillators throughout the central nervous system (CNS) and in peripheral organs. The hippocampus is considered a secondary oscillator, as it displays oscillations in long-term potentiation (LTP), as well as in memory encoding, consolidation, and retrieval. These rhythmic variations are accompanied by time-dependent expression of core clock genes such as

Per1,

Per2,

Clock, and

Bmal1, suggesting that local molecular clocks modulate synaptic plasticity and cognitive performance across the day-night cycle [

1,

5,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) are widely distributed throughout the CNS, particularly in the hippocampus, where they play a crucial role in learning and memory processes. A major source of cholinergic projections to the hippocampus arises from the basal forebrain and establishes synaptic contacts with intrinsic glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons within this structure [

8].

Extensive evidence documents the rhythmicity of acetylcholine (ACh) release and content in several CNS regions, including the hippocampus and cortex, indicating a correlation between the peak activity of this neurotransmitter system and the behavioral activity patterns of the studied animals. However, data concerning the circadian rhythmicity of mAChRs remain scarce and are mostly derived from studies conducted in the 1980s. Moreover, many of these early investigations relied on a single concentration of the mAChR antagonist [³H]QNB rather than constructing full saturation binding curves [

19,

22,

38]. Using [³H]QNB binding, Por and Bondy [

22] reported a peak in hippocampal mAChR expression at midnight, corresponding to the dark period. Similarly, Mash et al. [

21] observed circadian rhythmicity in mAChRs within the forebrain and brainstem, noting an increased number of receptors at the onset of the light phase. According to the review by Hut and Van der Zee [

10], muscarinic cholinergic transmission in the nervous system is more active during wakefulness due to elevated ACh release, which inversely correlates with receptor density.

The present study demonstrates that daily rhythmicity characterizes the expression of mAChRs in the hippocampus—a region rich in these receptors and fundamentally involved in learning and memory. This rhythmicity affects both receptor density and sensitivity, as reflected by changes in binding affinity. Such variations were observed in both male and female rats; however, the timing of peak expression and affinity differed between sexes.

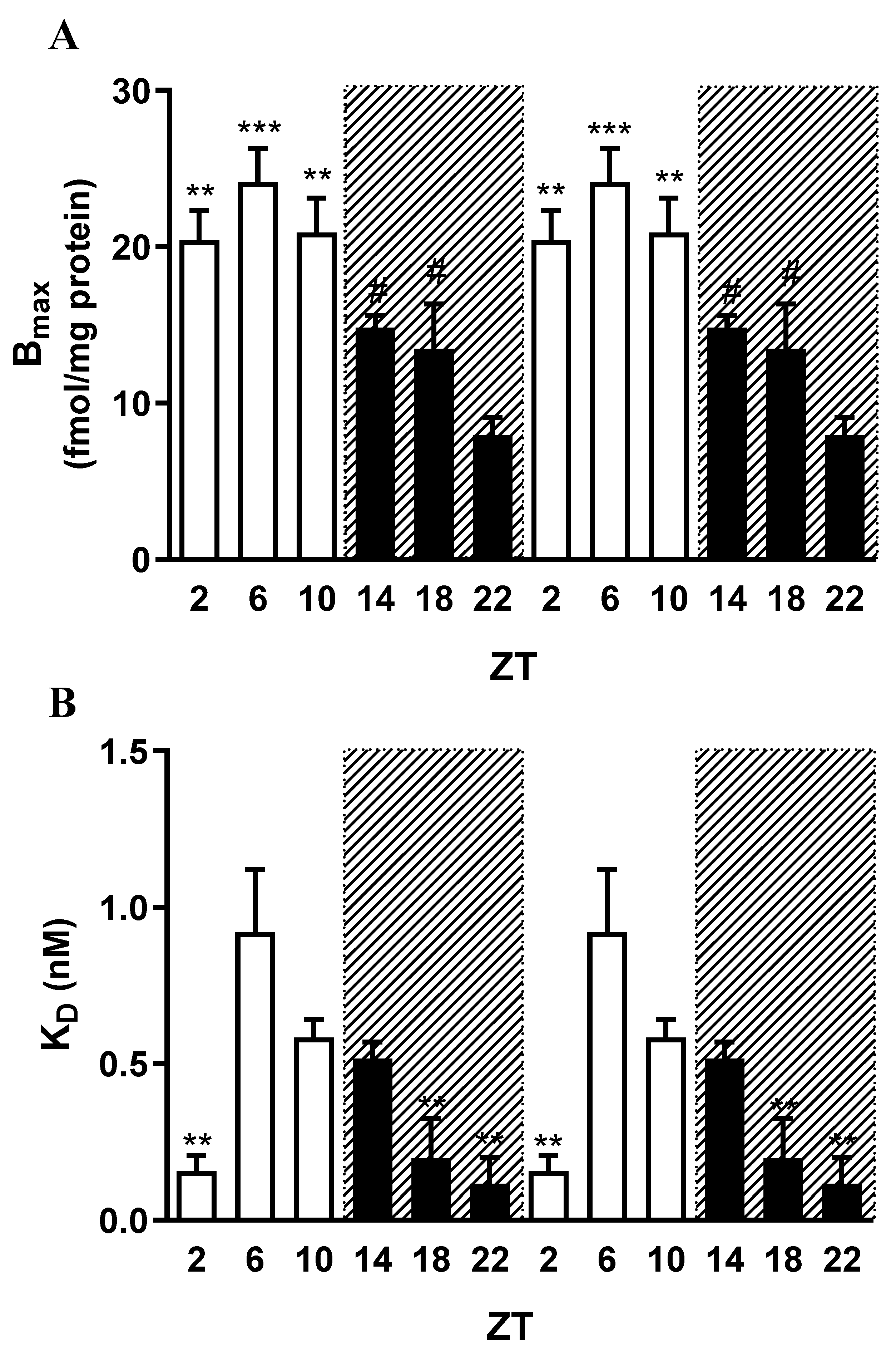

The analysis of parameters derived from the [³H]QNB binding curves, specifically Bmax and KD, revealed that 90-day-old male rats exhibit a higher density of hippocampal mAChRs during the light period at ZTs 2, 6, and 10, whereas receptor density decreases during the dark period at ZTs 14, 18, and 22. Regarding receptor affinity, an increase was observed at ZT2 during the light phase and again at ZTs 18 and 22 during the dark phase. It is noteworthy that muscarinic cholinergic function in the hippocampus appears to be enhanced when both receptor density and affinity are elevated simultaneously, which occurs at the beginning of the light period (ZT2). At ZTs 18 and 22, although receptor affinity remains high, receptor density is reduced.

Although previous studies have not reported daily variations in mAChR affinity [

20]—with the exception of Mash et al. [

21]—our findings suggest that, in addition to fluctuations in receptor expression, hippocampal mAChRs also exhibit daily variations in binding affinity throughout the day.

Our data for male rats contradict the limited literature reporting an increase in hippocampal mAChRs during the night (Por and Bondy 1981) [

22]. It is important to note that several studies associate enhanced cholinergic function with the wakefulness period of the studied animals [

10,

39]. This relationship holds true for ACh release; however, it does not apply to the number or affinity of mAChRs in males, in which the highest receptor density is observed during the light period. Indeed, Mizuno et al. [

15] demonstrated variations in hippocampal ACh release in female rats, showing a significant increase during the dark phase, coinciding with elevated motor activity. Other studies have also confirmed that ACh release in the rat hippocampus correlates with locomotor activity, showing a marked increase at the onset of the dark period. This rhythm persists under constant darkness, suggesting regulation by a circadian oscillator, most likely the suprachiasmatic nucleus [

12,

40].

In our study, mAChRs were analyzed under conditions in which a light–dark cycle was maintained and, therefore, under entrained conditions; consequently, we cannot ascertain whether this rhythm persists in the absence of a zeitgeber.

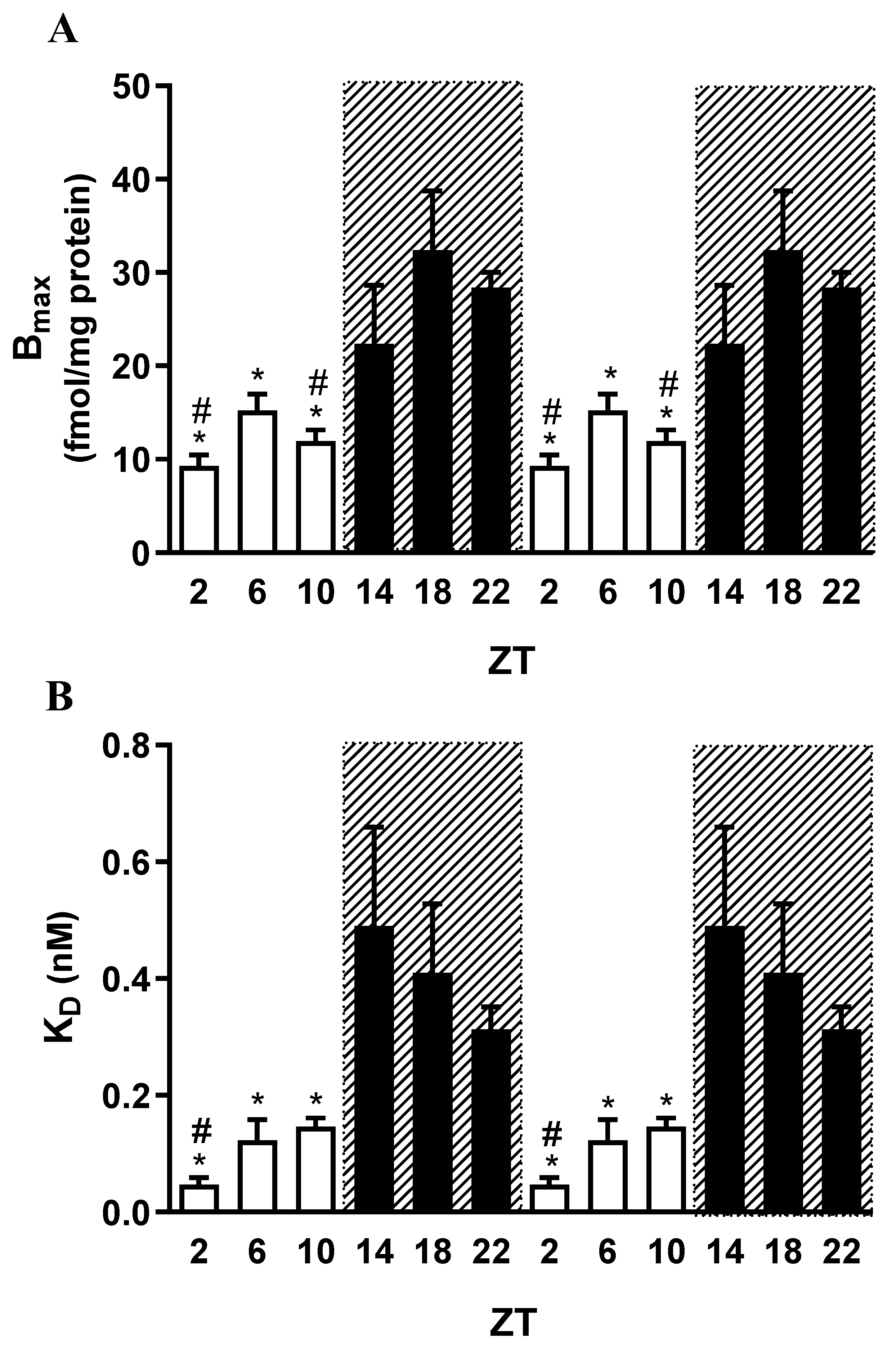

A contrasting pattern of maximal mAChR density was observed between males and females. In males, receptor expression peaked during the light period, whereas in females, the highest expression occurred during the dark period. The relationship between receptor density and affinity indicated greater functional activity of mAChRs at ZT2—corresponding to the beginning of the light phase in males—and at ZT22—near the end of the dark phase in females—showing a relatively small temporal difference between sexes.

In females, it is important to note that the phases of the estrous cycle were not determined, resulting in a random distribution of animals across different stages. Estrogen acts as a potent modulator of circadian rhythmicity, influencing the expression of specific clock genes, clock-controlled genes, and, most notably, locomotor activity [

41]. According to Alvord et al. [

40], the proestrus and estrus phases in rats are associated with a phase advance and a prolonged duration of locomotor activity.

The regulation of cholinergic neurotransmission by steroid hormones is also well established. Cardoso et al. [

31,

33] demonstrated that hippocampal mAChRs are upregulated following ovariectomy compared with rats in the proestrus phase, with increases observed across all receptor subtypes (M

1–M

5). Several other studies have similarly reported that estrogen modulates mAChR expression in various brain regions of female rats, leading to greater variability in mAChR density and affinity in females than in males [

42,

43,

44]. Furthermore, estrogen receptor expression in the hippocampus fluctuates across the estrous cycle, rendering this region particularly sensitive to changes in ovarian hormone levels [

45].

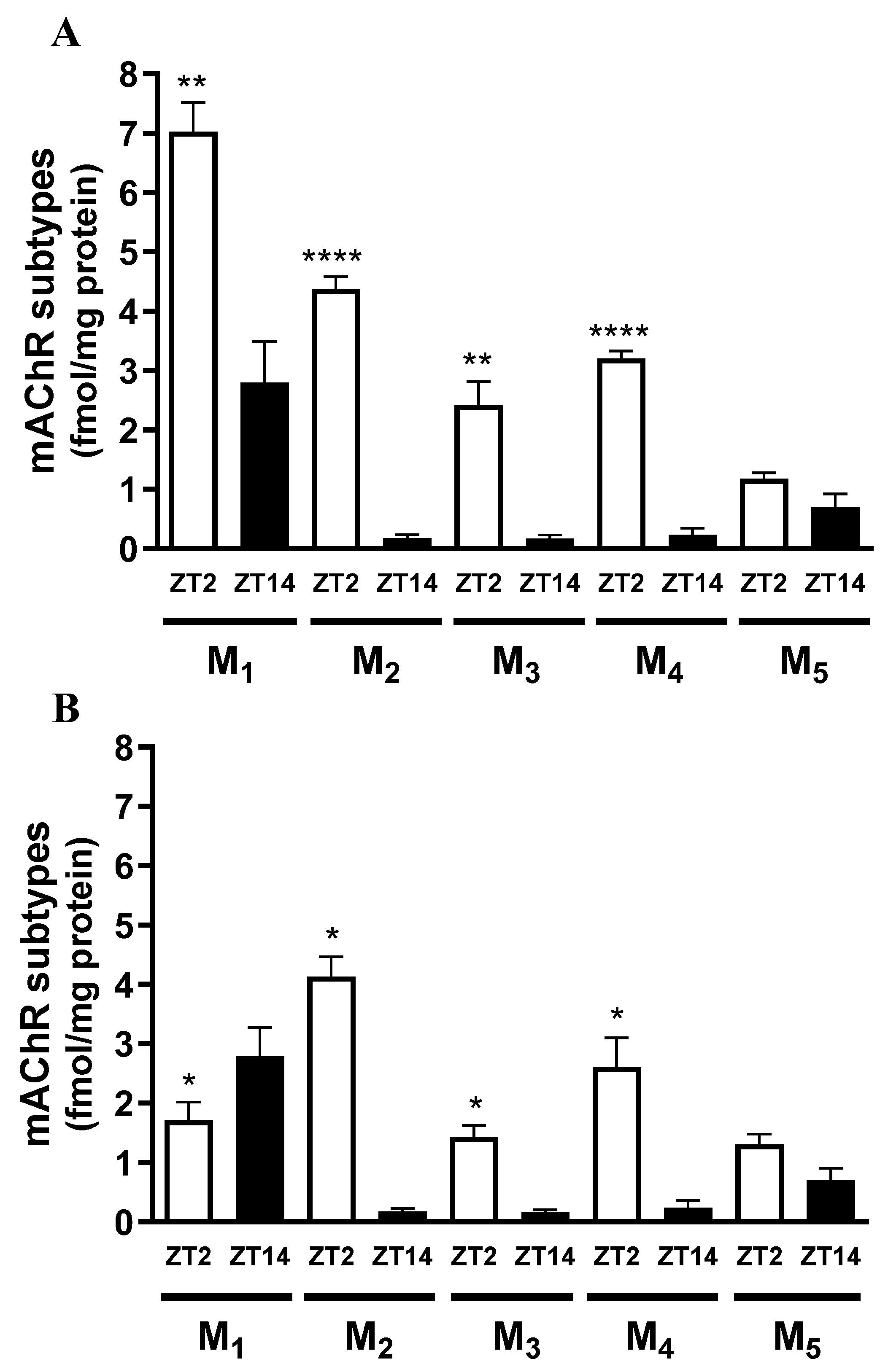

In general, the expression of mAChR subtypes was higher during the light period compared with the dark period, although this difference did not reach statistical significance for M5. An exception was observed in females, in which M1 expression was elevated during the dark period. Consistent with these findings, the total number of mAChRs in males was also higher during the light phase. In contrast, females exhibited greater total mAChR expression during the dark phase, while M2–M4 subtypes were predominantly expressed during the light phase. The increased expression of the M1 subtype at night may partly account for the higher overall mAChR levels during this period, given the predominance of M1 in the rat hippocampus.

Our results also revealed that mAChR sensitivity—reflecting both receptor density and affinity—is higher in males at the beginning of the light period, whereas in females it peaks at the end of the dark period. Interestingly, when considering male receptor affinity alone, an increase is observed toward the end of the dark phase, coinciding with a rise in ACh release and thereby enhancing cholinergic function at that time. Notably, mAChR functionality in females appears to be maximal at the end of the dark period, characterized by increased receptor density and affinity accompanied by elevated ACh release.

In conclusion, cholinergic transmission in the hippocampus—crucial for learning and memory processes—exhibits daily rhythmicity in its functional activity. While ACh release is primarily associated with periods of behavioral activity, an opposite pattern is observed for mAChR expression in male rats. This inverse relationship may reflect a negative feedback mechanism between ACh release and mAChR expression, given that receptor internalization constitutes a key regulatory process for mAChRs [

46]. A comprehensive investigation simultaneously assessing both mAChR expression and ACh release in the rat hippocampus across the circadian cycle would further elucidate the dynamics of this interaction.

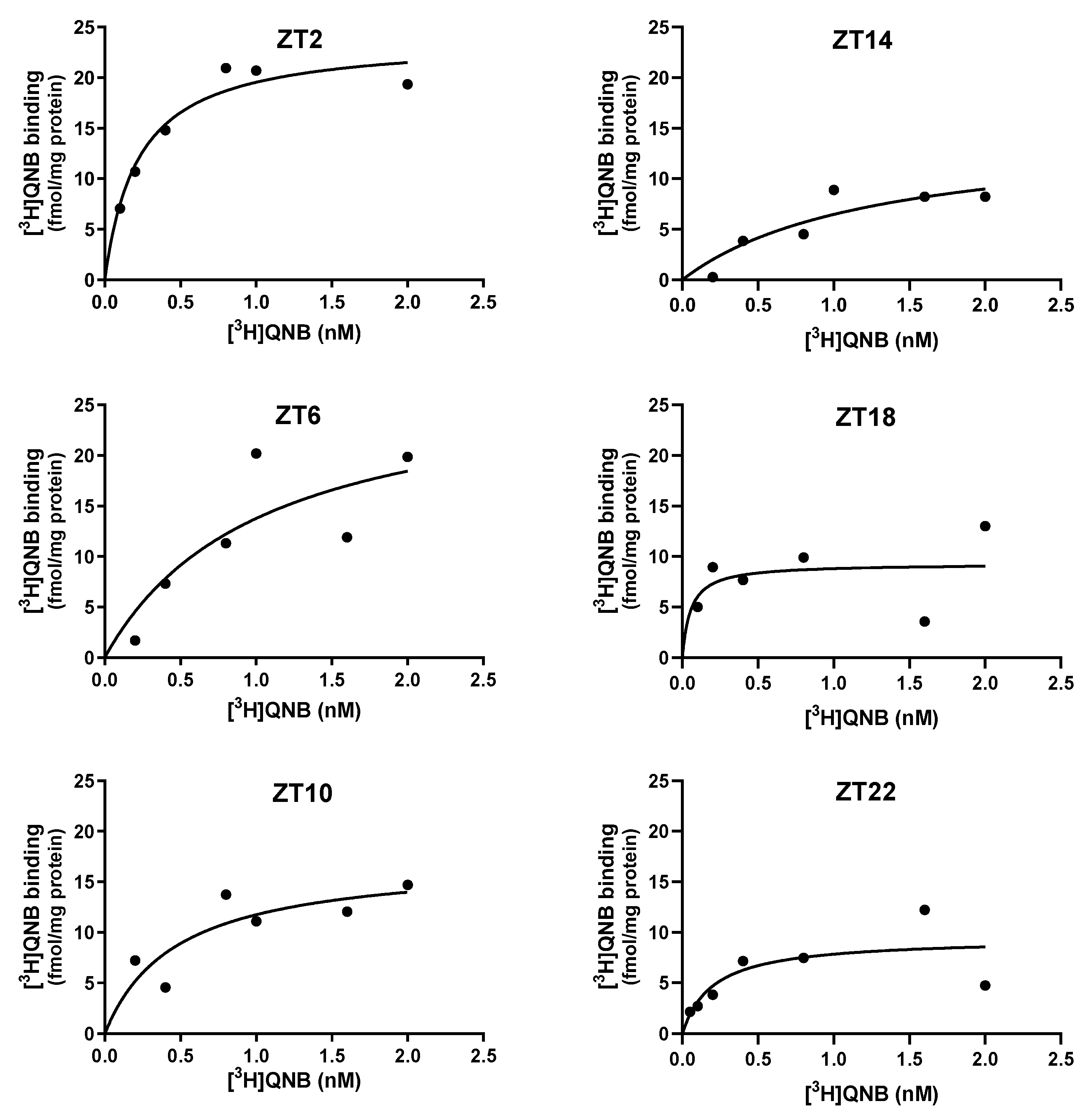

Figure 1.

Specific saturation curves of [³H]QNB binding to hippocampal membrane preparations from male rats at ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase. Results are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3), each performed in duplicate.

Figure 1.

Specific saturation curves of [³H]QNB binding to hippocampal membrane preparations from male rats at ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase. Results are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3), each performed in duplicate.

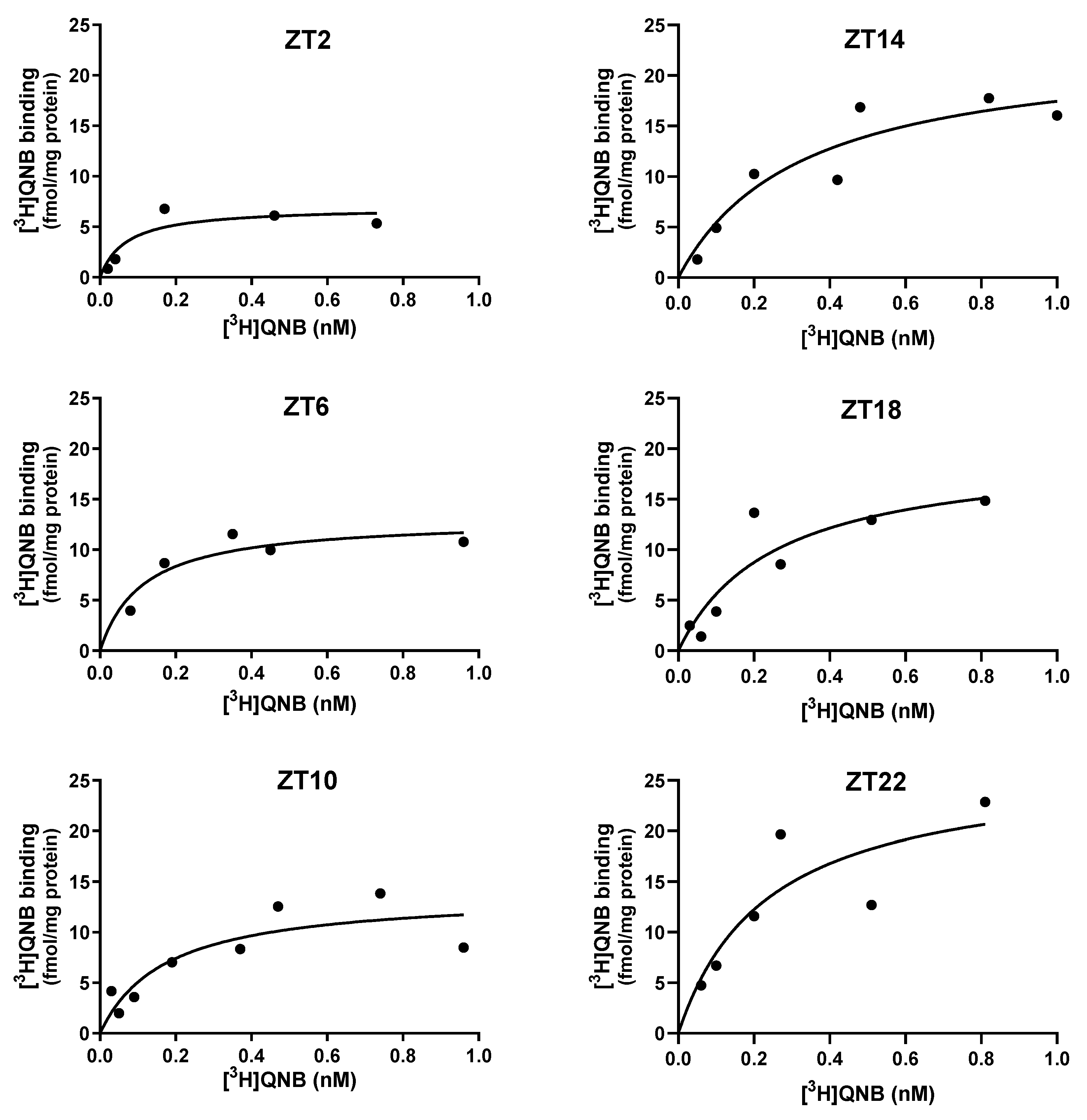

Figure 2.

Specific saturation curves of [³H]QNB binding to hippocampal membrane preparations from female rats at ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase. Results are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3), each performed in duplicate.

Figure 2.

Specific saturation curves of [³H]QNB binding to hippocampal membrane preparations from female rats at ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase. Results are representative of three independent experiments (n = 3), each performed in duplicate.

Figure 3.

Daily variations in hippocampal mAChRs in 90-day-old male rats, measured through binding assays at ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase. The analysis shows mAChR densities (Bmax) (A) and affinities (B), expressed as dissociation constants (KD). The 24-hour period is duplicated for better visualization. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. of three experiments, each performed in duplicate (one-way ANOVA: p < 0.01; Newman–Keuls test: Bmax: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. ZT22; #p < 0.05 vs. ZT6; KD: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. ZT6).

Figure 3.

Daily variations in hippocampal mAChRs in 90-day-old male rats, measured through binding assays at ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase. The analysis shows mAChR densities (Bmax) (A) and affinities (B), expressed as dissociation constants (KD). The 24-hour period is duplicated for better visualization. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. of three experiments, each performed in duplicate (one-way ANOVA: p < 0.01; Newman–Keuls test: Bmax: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. ZT22; #p < 0.05 vs. ZT6; KD: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. ZT6).

Figure 4.

Daily variations in hippocampal mAChRs in 90-day-old female rats, evaluated through binding assays at ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase. The analysis shows mAChR densities (Bmax) (A) and affinities (B), expressed as dissociation constants (KD). The 24-hour period is duplicated for better visualization. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. of three experiments, each performed in duplicate. (One-way ANOVA: p < 0.001; Newman–Keuls: Bmax: *p < 0.05 vs. ZT18; #p < 0.05 vs. ZT22; KD: *p < 0.05 vs. ZT14; #p < 0.05 vs. ZT18.).

Figure 4.

Daily variations in hippocampal mAChRs in 90-day-old female rats, evaluated through binding assays at ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase. The analysis shows mAChR densities (Bmax) (A) and affinities (B), expressed as dissociation constants (KD). The 24-hour period is duplicated for better visualization. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. of three experiments, each performed in duplicate. (One-way ANOVA: p < 0.001; Newman–Keuls: Bmax: *p < 0.05 vs. ZT18; #p < 0.05 vs. ZT22; KD: *p < 0.05 vs. ZT14; #p < 0.05 vs. ZT18.).

Figure 5.

Expression levels of M1–M5 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in the hippocampus of 90-day-old male rats (A) and 90-day-old female rats (B). Samples were analyzed at ZT2 (light phase) and ZT14 (dark phase). Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M., with n = 3–7. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001, indicating a statistically significant difference from ZT14 for each mAChR subtype (t-test).

Figure 5.

Expression levels of M1–M5 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in the hippocampus of 90-day-old male rats (A) and 90-day-old female rats (B). Samples were analyzed at ZT2 (light phase) and ZT14 (dark phase). Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M., with n = 3–7. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001, indicating a statistically significant difference from ZT14 for each mAChR subtype (t-test).

Table 1.

[³H]QNB saturation binding parameters. Receptor densities (Bmax) and dissociation constants (KD) of muscarinic receptors in hippocampal membrane preparations from male rats at Zeitgeber times (ZTs) 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase.

Table 1.

[³H]QNB saturation binding parameters. Receptor densities (Bmax) and dissociation constants (KD) of muscarinic receptors in hippocampal membrane preparations from male rats at Zeitgeber times (ZTs) 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase.

| ZT |

Bmax

(fmol/mg protein) |

KD

(nM) |

| 2 |

20.45 ± 1.86**

|

0.16 ± 0.05**

|

| 6 |

24.14 ± 2.14***

|

0.92 ± 0.20 |

| 10 |

20.92 ± 2.20**

|

0.58 ± 0.05 |

| 14 |

14.81 ± 0.79#

|

0.51 ± 0.05 |

| 18 |

13.46 ± 2.88#

|

0.19 ± 0.12**

|

| 22 |

7.94 ± 1.11 |

0.12 ± 0.09*

|

Table 2.

[³H]QNB saturation binding parameters. Receptor densities (Bmax) and dissociation constants (KD) of muscarinic receptors in hippocampal membrane preparations from female rats at Zeitgeber times (ZTs) 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase.

Table 2.

[³H]QNB saturation binding parameters. Receptor densities (Bmax) and dissociation constants (KD) of muscarinic receptors in hippocampal membrane preparations from female rats at Zeitgeber times (ZTs) 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. ZTs 2, 6, and 10 correspond to the light phase, whereas ZTs 14, 18, and 22 correspond to the dark phase.

| ZT |

Bmax

(fmol/mg protein) |

KD

(nM) |

| 2 |

9.28 ± 1.18*#

|

0.05 ± 0.01*#

|

| 6 |

15.24 ± 1.74*

|

0.12 ± 0.03*

|

| 10 |

11.92 ± 1.21*#

|

0.15 ± 0.01*

|

| 14 |

22.35 ± 6.29 |

0.49 ± 0.17 |

| 18 |

32.39 ± 6.35 |

0.41 ± 0.12 |

| 22 |

28.41 ± 1.61 |

0.31 ± 0.04 |