1. Introduction

The circadian system comprises organ- and tissue-specific clocks that regulate and synchronize physiological functions on a 24-hour time scale, aligning them with the environmental day-night cycle. Disruption of this alignment—such as that caused by shift work or jet lag—impairs the regulation of bodily functions and may ultimately contribute to metabolic syndrome, addictive behaviors, cardiovascular disease, and neurological disorders [

1].

At the cellular level, the circadian clock operates through a transcriptional-translational feedback loop with an approximately 24-hour period. In mammals, the core clock genes include

Bmal1 and

Clock (or its homolog

Npas2), which activate the transcription of

Per and

Cry genes. These, in turn, inhibit their own activation, forming a negative feedback loop. The nuclear receptors REV-ERBα and RORα further regulate the expression of

Bmal1,

Clock, and

Npas2 by repressing or activating their transcription, respectively, thereby completing the core clock mechanism [

2]. This mechanism can be modulated by: (1) molecules that bind to nuclear receptors—such as free fatty acids and glucocorticoids acting on PPARα and REV-ERBα—and (2) indirectly via glutamate and its receptors [

3].

Circadian behavioral activity is primarily modulated by light. Changes in light intensity trigger adaptive responses, either advancing or delaying the organism’s activity phase depending on the timing of exposure. For instance, a 15-minute light pulse late in the subjective night (e.g., circadian time 22; CT22) advances the clock phase, whereas light exposure early in the subjective night (e.g., CT14) delays it [

4,

5,

6]. At the cellular level, light stimulates the release of neurotransmitters—such as glutamate—at synapses connected to the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN), the master pacemaker of the circadian system. This leads to the induction of immediate early genes, such as

Fos, and clock genes, such as

Per1 and Per2 [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Notably, mutation of the

Per2 gene in all cells of mice shortens the circadian period, diminishes phase delays, and enhances phase advances. In contrast, global deletion of

Per1 shortens the period and reduces phase advances only [

12,

13]. Cell-type-specific deletion of

Per2 in astrocytes or neurons also shortens the clock period, but only neuronal deletion affects phase shifts [

14]. The distinct role of

Per1 in astrocytes and neurons regarding period regulation and phase-shifting remains unclear. Therefore, we investigated the contributions of

Per1 in these cell types to circadian period and light-induced phase-shifting responses.

3. Discussion

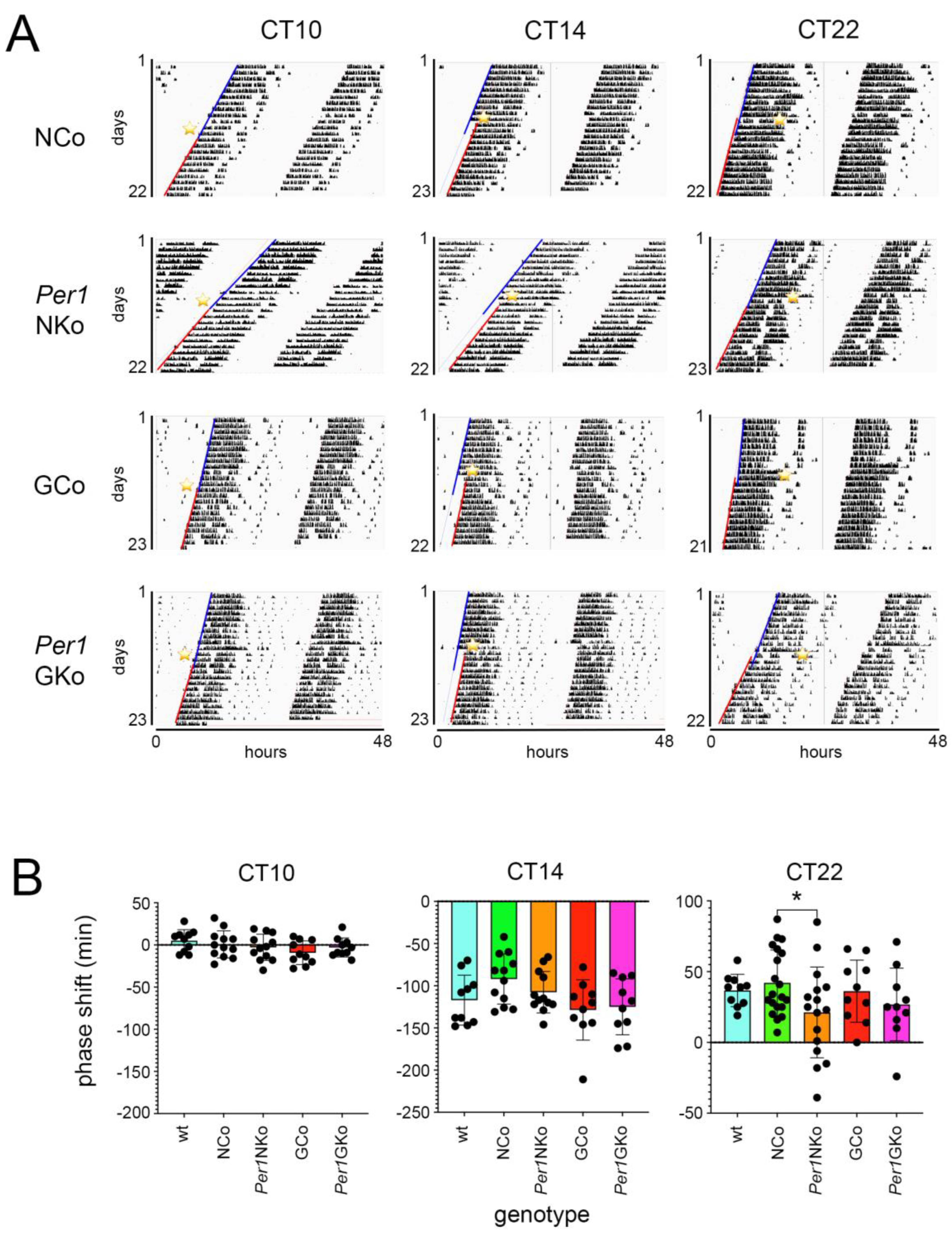

In this study, we investigated how the absence of the Per1 gene in neurons and astrocytes affects circadian period and phase, using wheel-running activity as a behavioral paradigm. Our experiments revealed that deletion of Per1 in astrocytes had no measurable impact on these parameters. In contrast, the absence of Per1 in neurons led to a shortened circadian period and diminished phase advances in response to a light pulse administered at CT22.

Previous studies have reported that

Per1::luc reporter expression is undetectable in glial cells within organotypic SCN slice cultures from rat brain [

18]. However,

Per1::luc rhythms were observed in cultured astrocytes derived from cortical rat tissue [

19]. This discrepancy suggests that

Per1 expression in astrocytes may be substantially lower or more diffuse than in neurons, where

Per1::luc expression is readily detectable [

18]. Our immunohistochemistry data support this interpretation (

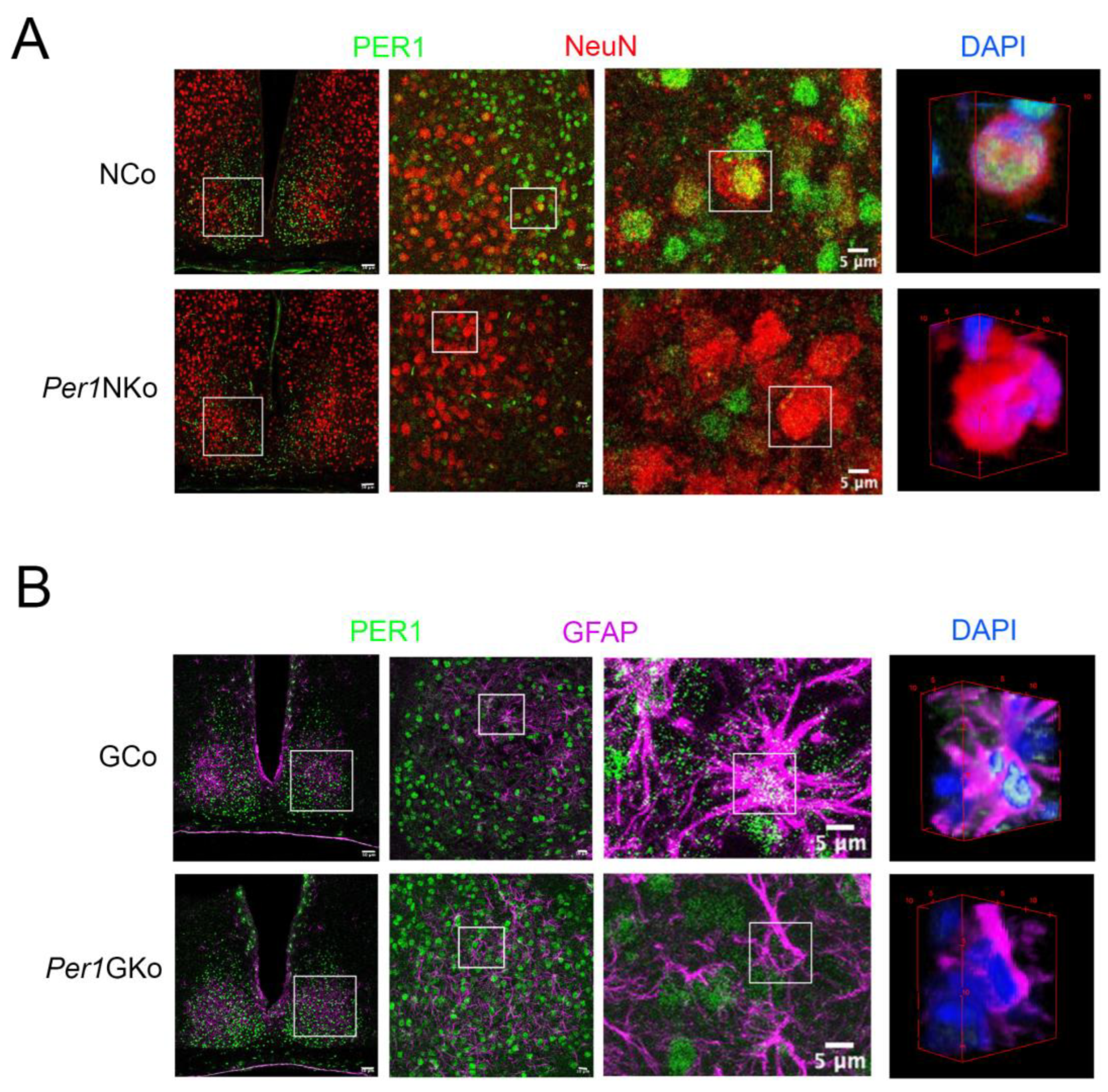

Figure 1): we observed high levels of PER1 protein in SCN neurons (

Figure 1A), while PER1 signal in astrocytes was markedly lower (

Figure 1B).

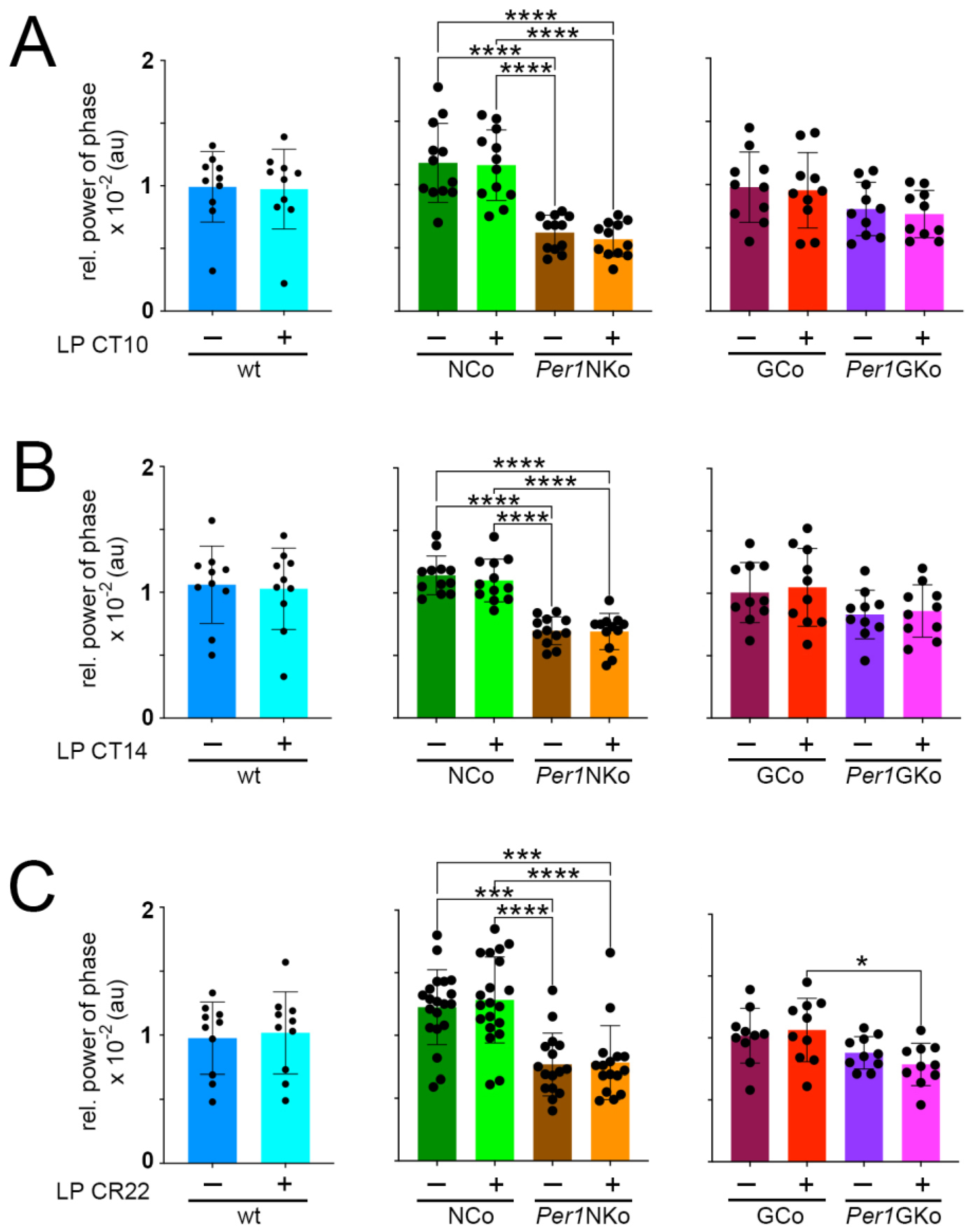

Consistent with these findings, all behavioral circadian parameters assessed in mice lacking

Per1 in glial cells (

Per1GKo) were indistinguishable from controls. Phase shifting remained unaffected (

Figure 3), period was comparable (

Figure 4), amplitude was normal (

Figure 5), and relative power of phase was unchanged (

Figure 6). Total wheel-running activity also matched that of control animals (

Figure 7). These results suggest that astrocytic

Per1 plays a minimal, if any, role in regulating behavioral circadian clock parameters

in vivo.

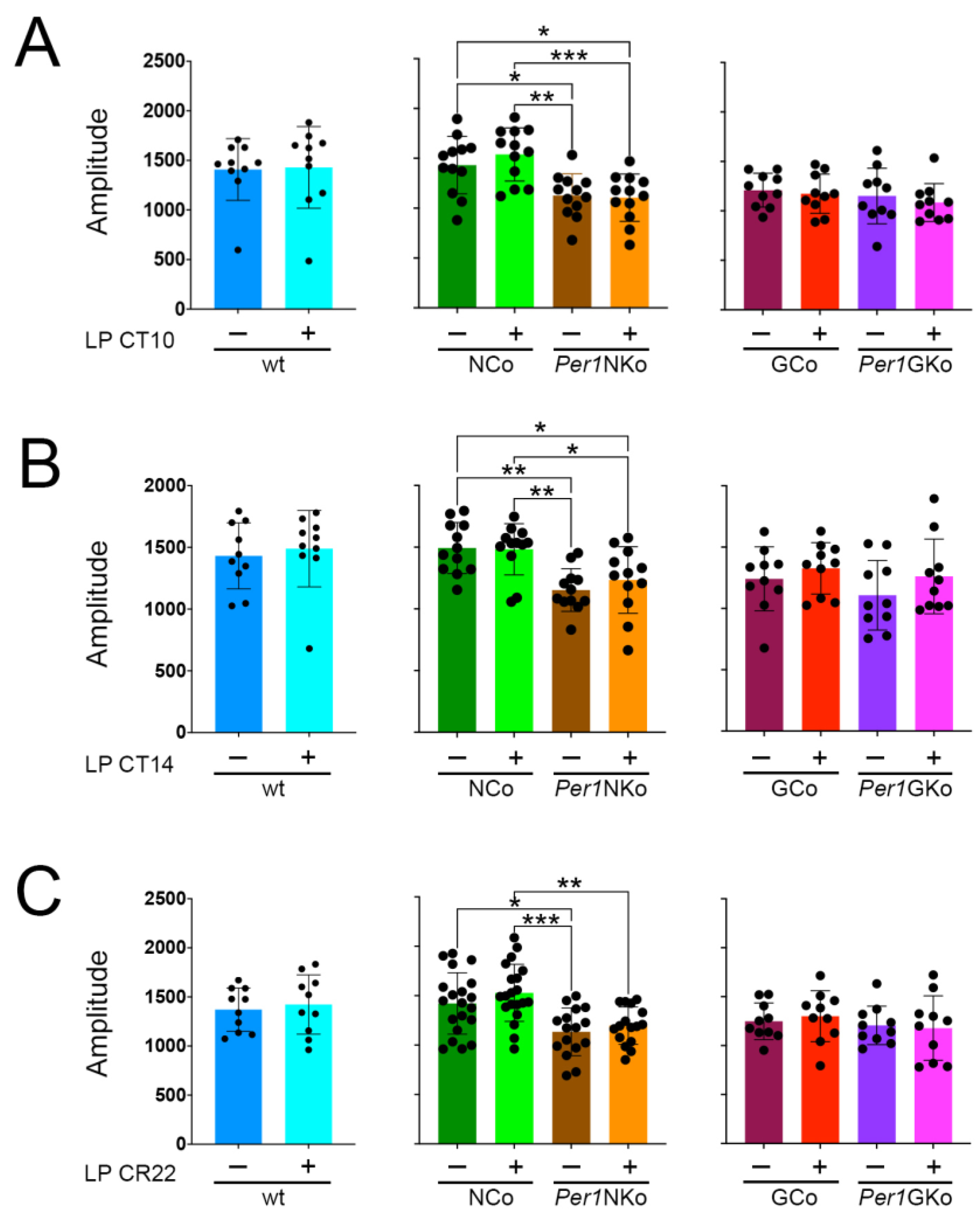

In contrast, deletion of

Per1 in neurons resulted in reduced light-induced phase advances (

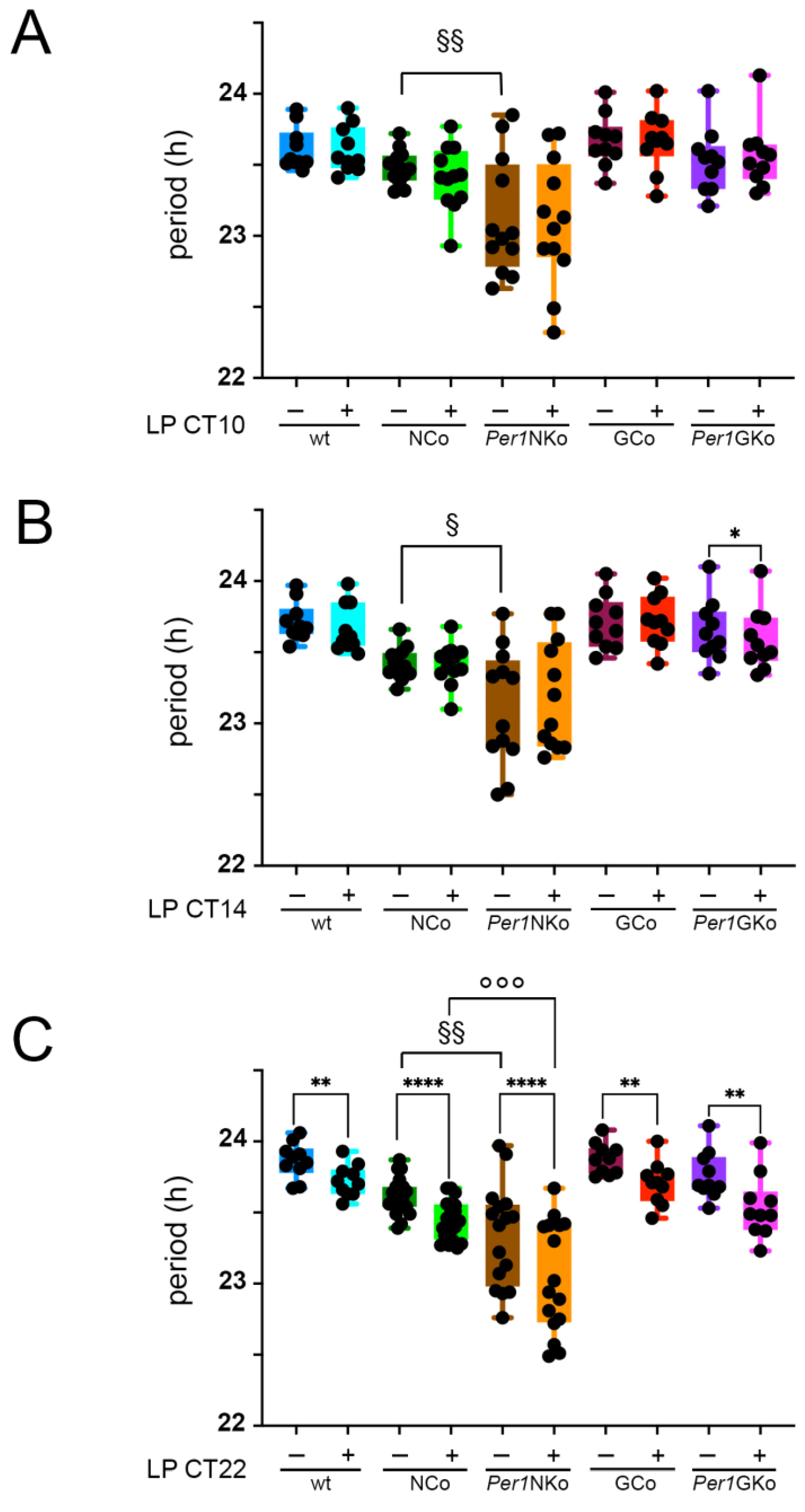

Figure 3), shortened period (

Figure 4), and decreased amplitude (

Figure 5), culminating in reduced relative power of phase (

Figure 6)—indicative of a weakened circadian oscillator. Notably, these changes were not attributable to differences in total wheel-running activity, which remained consistent across all groups. These findings, in line with previous reports [

18], reinforce the notion that

Per1 primarily influences behavioral circadian parameters through neuronal mechanisms rather than astrocytic ones.

Several studies have demonstrated that

Per1 expression in the SCN can be induced by brief light exposure [

7,

10,

11]. Moreover, global deletion of

Per1 in mice has been shown to impair phase advances without affecting phase delays [

12], suggesting that light-induced

Per1 expression is specifically linked to phase advances. Our findings support and extend this view by showing that

Per1 expression in neurons—but not astrocytes—is necessary for light-induced phase advances (

Figure 3).

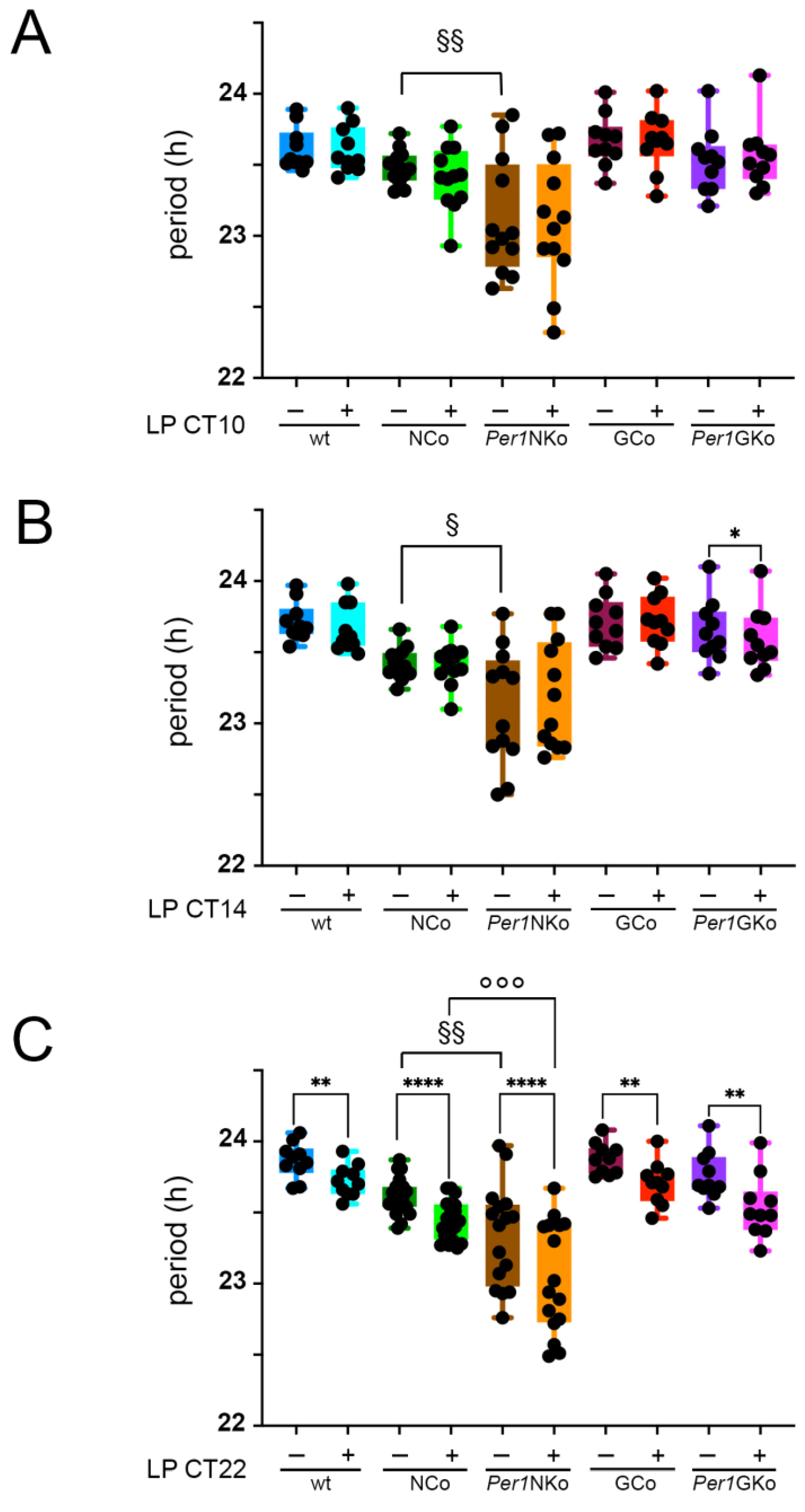

The reduction in phase advances observed in

Per1NKo mice cannot be solely attributed to light-induced period shortening at CT22 (

Figure 4C). All genotypes exhibited period shortening following a light pulse at CT22, which could be interpreted as an earlier onset of activity the next day, contributing to the phase advances seen in

Figure 3. This effect was also present in

Per1NKo mice (

Figure 4C, orange bar), and the difference in period between NCo and

Per1NKo mice increased post-light pulse, with

Per1NKo mice showing an even shorter period (

Figure 4C, §§ and °°°). If period shortening alone accounted for phase advances,

Per1NKo mice would be expected to show greater advances than controls. However, the opposite was observed, indicating that

Per1's role in phase advancement in response to light at CT22 involves a molecular pathway distinct from its role in period regulation.

The functions of

Per1 and

Per2 genes appear to be distinct [

12,

20,

21], and this distinction is evident when comparing their roles in neurons and astrocytes. In this study, we found that

Per1 in neurons—but not astrocytes—was critical for regulating period and phase advances. In contrast,

Per2 influenced period in both cell types, but only neuronal

Per2 was essential for phase delays [

14]. This functional segregation aligns with previous reports showing that

Per1-reporter expression is predominantly neuronal, while

Per2-reporter expression is more restricted to non-neuronal populations [

22]. Our findings also corroborate a recent study indicating that astrocytes regulate circadian period but not phase in the SCN [

23].

In summary, astrocytic Per1 appears to have limited importance for circadian regulation, whereas astrocytic Per2 contributes to period control but not to light-mediated phase shifts. In neurons, both Per paralogs are essential: Per1 for phase advances and Per2 for phase delays.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E. and U.A.; methodology, D.E.; validation, D.E, and U.A.; formal analysis, D.E.; investigation, D.E.; resources, U.A.; data curation, D.E.; writing—original draft preparation, U.A.; writing—review and editing, D.E.; visualization, U.A.; supervision, U.A.; project administration, U.A.; funding acquisition, U.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry of PER1 expression in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) of neuronal control (NCo), neuronal Per1 knock-out (Per1NKo), glial control (GCo) and glial Per1 knock-out (Per1GKo) mice at Zeitgeber time (ZT) 12. (A) Photomicrographs of SCNs from NCo and Per1NKO mice at low to high magnification (from left to right, white line = 50 µm, 10 µm, 5 µm). White squares indicate the magnified areas. The images at right show 3D reconstructions of cells with DAPI nuclear staining (blue). Green = PER1, red = NeuN specific to neuronal cells. (B) Photomicrographs of SCNs from GCo and Per1GKO mice at low to high magnification (from left to right, white line = 50 µm, 10 µm, 5 µm). White squares indicate the magnified areas. The images at right show 3D reconstructions of cells with DAPI nuclear staining (blue). Green = PER1, pink = glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) specific to glial cells including astrocytes.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry of PER1 expression in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) of neuronal control (NCo), neuronal Per1 knock-out (Per1NKo), glial control (GCo) and glial Per1 knock-out (Per1GKo) mice at Zeitgeber time (ZT) 12. (A) Photomicrographs of SCNs from NCo and Per1NKO mice at low to high magnification (from left to right, white line = 50 µm, 10 µm, 5 µm). White squares indicate the magnified areas. The images at right show 3D reconstructions of cells with DAPI nuclear staining (blue). Green = PER1, red = NeuN specific to neuronal cells. (B) Photomicrographs of SCNs from GCo and Per1GKO mice at low to high magnification (from left to right, white line = 50 µm, 10 µm, 5 µm). White squares indicate the magnified areas. The images at right show 3D reconstructions of cells with DAPI nuclear staining (blue). Green = PER1, pink = glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) specific to glial cells including astrocytes.

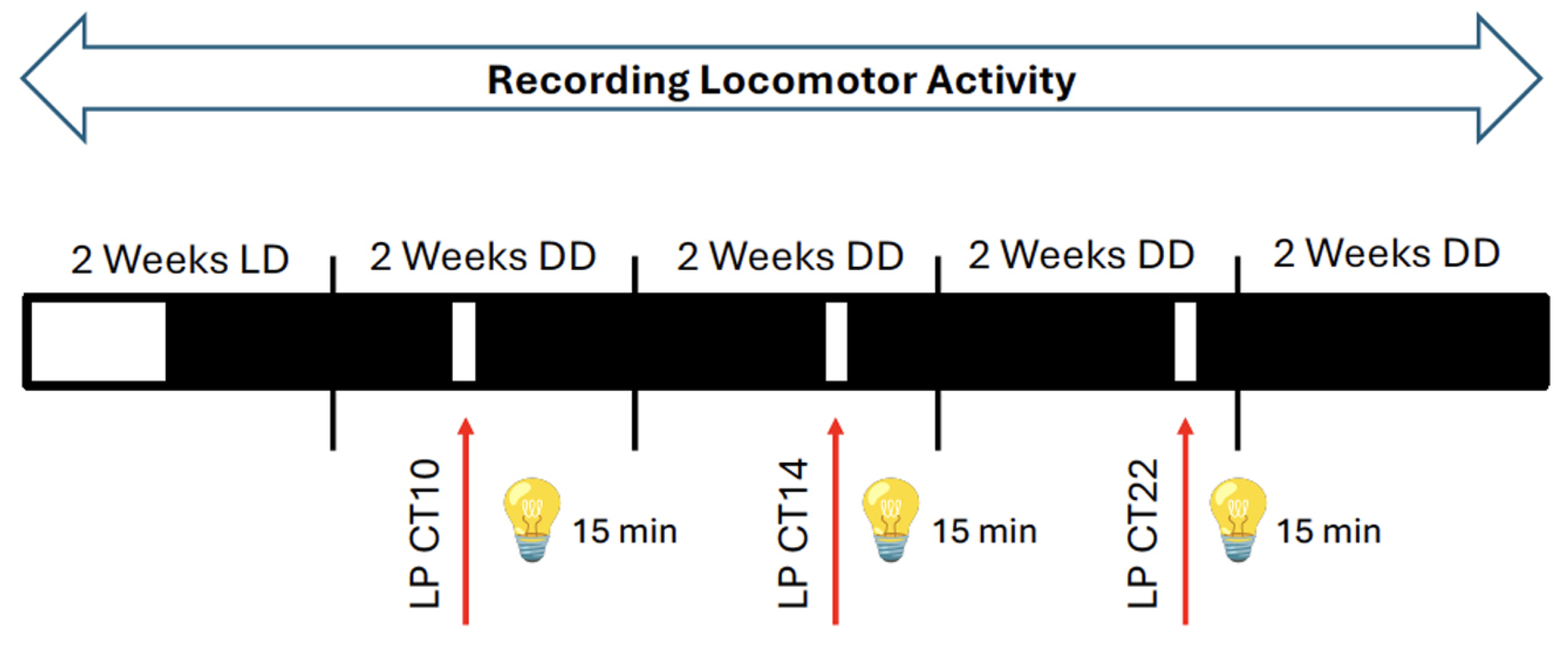

Figure 2.

Experimental design for application of 15-minute light pulses (LPs, red arrows) using the Aschoff type I protocol. Mice were kept in a light / dark cycle (LD) for 2 weeks and then they were released into constant darkness (DD) before receiving a LP at circadian time (CT) 10. Subsequently, the animals were kept for 2 weeks in DD before they received a LP at CT14 (early subjective night). The mice were again kept for 2 weeks in DD and then they received a LP at CT22 (late subjective night). Subsequently, the animals were kept again in DD for 2 weeks. During the whole experiment locomotor activity was recorded. White and black bars represent light or dark, respectively.

Figure 2.

Experimental design for application of 15-minute light pulses (LPs, red arrows) using the Aschoff type I protocol. Mice were kept in a light / dark cycle (LD) for 2 weeks and then they were released into constant darkness (DD) before receiving a LP at circadian time (CT) 10. Subsequently, the animals were kept for 2 weeks in DD before they received a LP at CT14 (early subjective night). The mice were again kept for 2 weeks in DD and then they received a LP at CT22 (late subjective night). Subsequently, the animals were kept again in DD for 2 weeks. During the whole experiment locomotor activity was recorded. White and black bars represent light or dark, respectively.

Figure 3.

Wheel-running activity and effect of light pulses on control and cell type specific Per1 knock-out mice under constant darkness (DD) conditions (Aschoff type I protocol). (A) Representative actograms of wheel-running activity of neuronal control (NCo), neuronal Per1 knock-out (Per1NKo), glial control (GCo) and glial Per1 knock-out (Per1GKo) animals. A 15-minute light pulse (LP) was applied at circadian time (CT) 10, 14, and 22 (yellow asterisk). The blue lines indicate onset of wheel-running activity before the LP and the red lines onset of activity after the LP. (B) Quantification of the distances between the blue and red lines in A representing the amount of phase shift in minutes after an LP at CT10 (left panel), CT14 (middle panel) and CT22 (right panel). Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10 for wt (light blue), GCo (red), Per1GKo (pink) and n = 20 for NCo (green) and n = 16 for Per1NKo (orange). A diminished phase advance in Per1 NKo mice was observed in response to an LP at CT22 (*p < 0.05, unpaired t-test).

Figure 3.

Wheel-running activity and effect of light pulses on control and cell type specific Per1 knock-out mice under constant darkness (DD) conditions (Aschoff type I protocol). (A) Representative actograms of wheel-running activity of neuronal control (NCo), neuronal Per1 knock-out (Per1NKo), glial control (GCo) and glial Per1 knock-out (Per1GKo) animals. A 15-minute light pulse (LP) was applied at circadian time (CT) 10, 14, and 22 (yellow asterisk). The blue lines indicate onset of wheel-running activity before the LP and the red lines onset of activity after the LP. (B) Quantification of the distances between the blue and red lines in A representing the amount of phase shift in minutes after an LP at CT10 (left panel), CT14 (middle panel) and CT22 (right panel). Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10 for wt (light blue), GCo (red), Per1GKo (pink) and n = 20 for NCo (green) and n = 16 for Per1NKo (orange). A diminished phase advance in Per1 NKo mice was observed in response to an LP at CT22 (*p < 0.05, unpaired t-test).

Figure 4.

Period length in control (wt, NCo, GCo) and Per1 knock-out animals (Per1NKo, Per1GKo) and effect of a light pulse (LP) on period. (A) Period before and after an LP at CT10 are similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Period in Per1NKo mice (brown) before the LP is significantly shorter compared to NCo animals (dark green)(§§p < 0.01, n = 12, unpaired t-test). (B) Period before and after an LP at CT14 are similar in all genotypes investigated, except for Per1GKo mice which show a significantly shortened period after the LP (*p < 0.05, n = 10, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test). Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Period in Per1NKo mice (brown) before the LP is significantly shorter compared to NCo animals (dark green)(§p < 0.05, n = 12, unpaired t-test). (C) Period before and after an LP at CT22 are significantly different in all genotypes investigated (**p < 0.01, n = 10 for wt, GCo, Per1GKo; ****p < 0.0001, n = 20 for NCo and 16 for Per1NKo, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Period in Per1NKo mice (brown) before the LP is significantly shorter compared to NCo animals (dark green)(§§p < 0.01, n = 16-20, unpaired t-test). Also after an LP at CT22 period in Per1NKo mice (orange) is significantly shorter compared to NCo animals (green)(°°°p < 0.001, n = 16-20, unpaired t-test).

Figure 4.

Period length in control (wt, NCo, GCo) and Per1 knock-out animals (Per1NKo, Per1GKo) and effect of a light pulse (LP) on period. (A) Period before and after an LP at CT10 are similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Period in Per1NKo mice (brown) before the LP is significantly shorter compared to NCo animals (dark green)(§§p < 0.01, n = 12, unpaired t-test). (B) Period before and after an LP at CT14 are similar in all genotypes investigated, except for Per1GKo mice which show a significantly shortened period after the LP (*p < 0.05, n = 10, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test). Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Period in Per1NKo mice (brown) before the LP is significantly shorter compared to NCo animals (dark green)(§p < 0.05, n = 12, unpaired t-test). (C) Period before and after an LP at CT22 are significantly different in all genotypes investigated (**p < 0.01, n = 10 for wt, GCo, Per1GKo; ****p < 0.0001, n = 20 for NCo and 16 for Per1NKo, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Period in Per1NKo mice (brown) before the LP is significantly shorter compared to NCo animals (dark green)(§§p < 0.01, n = 16-20, unpaired t-test). Also after an LP at CT22 period in Per1NKo mice (orange) is significantly shorter compared to NCo animals (green)(°°°p < 0.001, n = 16-20, unpaired t-test).

Figure 5.

Amplitude in control (wt, NCo, GCo) and Per1 knock-out animals (Per1NKo, Per1GKo) and effect of a light pulse (LP) on amplitude. (A) Amplitude before and after an LP at CT10 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Amplitude in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)(*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n = 12, one-way ANOVA). (B) Amplitude before and after an LP at CT14 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Amplitude in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)(*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 12, one-way ANOVA). (C) Amplitude before and after an LP at CT22 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Amplitude in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)(**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n = 12, one-way ANOVA).

Figure 5.

Amplitude in control (wt, NCo, GCo) and Per1 knock-out animals (Per1NKo, Per1GKo) and effect of a light pulse (LP) on amplitude. (A) Amplitude before and after an LP at CT10 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Amplitude in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)(*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n = 12, one-way ANOVA). (B) Amplitude before and after an LP at CT14 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Amplitude in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)(*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 12, one-way ANOVA). (C) Amplitude before and after an LP at CT22 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Amplitude in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)(**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n = 12, one-way ANOVA).

Figure 6.

Relative power of phase in control (wt, NCo, GCo) and Per1 knock-out animals (Per1NKo, Per1GKo) and effect of a light pulse (LP) on relative power of phase. (A) Relative power of phase before and after an LP at CT10 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Relative power of phase in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)( ****p < 0.0001, n = 12, one-way ANOVA). (B) Relative power of phase before and after an LP at CT14 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Relative power of phase in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)(****p < 0.0001, n = 12, one-way ANOVA). (C) Relative power of phase before and after an LP at CT22 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Relative power of phase in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)(***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, n = 12, one-way ANOVA). Relative power of phase in Per1GKo (magenta) is lower compared to GCo animals (red) after an LP at CT22 (*p < 0.05, n = 10, one-way ANOVA).

Figure 6.

Relative power of phase in control (wt, NCo, GCo) and Per1 knock-out animals (Per1NKo, Per1GKo) and effect of a light pulse (LP) on relative power of phase. (A) Relative power of phase before and after an LP at CT10 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Relative power of phase in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)( ****p < 0.0001, n = 12, one-way ANOVA). (B) Relative power of phase before and after an LP at CT14 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Relative power of phase in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)(****p < 0.0001, n = 12, one-way ANOVA). (C) Relative power of phase before and after an LP at CT22 is similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. Relative power of phase in Per1NKo mice before (brown) and after (orange) the LP is significantly lower compared to NCo animals (green)(***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, n = 12, one-way ANOVA). Relative power of phase in Per1GKo (magenta) is lower compared to GCo animals (red) after an LP at CT22 (*p < 0.05, n = 10, one-way ANOVA).

Figure 7.

Total wheel-running activity in control (wt, NCo, GCo) and Per1 knock-out animals (Per1NKo, Per1GKo) and effect of a light pulse (LP) on wheel-running activity. (A) Wheel revolutions per day before and after an LP at CT10 are similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. (B) Wheel revolutions per day before and after an LP at CT14 are similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. (C) Wheel revolutions per day before and after an LP at CT22 are similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12.

Figure 7.

Total wheel-running activity in control (wt, NCo, GCo) and Per1 knock-out animals (Per1NKo, Per1GKo) and effect of a light pulse (LP) on wheel-running activity. (A) Wheel revolutions per day before and after an LP at CT10 are similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. (B) Wheel revolutions per day before and after an LP at CT14 are similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12. (C) Wheel revolutions per day before and after an LP at CT22 are similar in all genotypes investigated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = 10-12.

Table 1.

Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry.

Table 1.

Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry.

| Antibody |

Species |

Company |

Catalog number |

Lot Number |

Dilution |

Anti-mPER1

(residues 6-21) |

Rabbit |

Merck Millipore |

AB2201 |

3480987 |

1:8000 |

| Anti-GFAP |

Goat |

Abcam |

AB53554 |

1046529-1 |

1:1000 |

| Anti-NeuN |

Chicken |

Merck Millipore |

ABN91 |

4049831 |

1:2000 |

| Alexa Fluor 647- AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Chicken IgG (H+L) |

Donkey |

Jackson Immunoresearch |

703-605-155 |

134612 |

1:1000 |

| Alexa Fluor 568 Donkey Anti-Goat IgG (H+L) |

Donkey |

Abcam |

Ab175704 |

GR3278446-1 |

1:1000 |

| Alexa Fluor 488-AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) |

Donkey |

Jackson Immunoresearch |

711-545-152 |

132876 |

1:1000 |