1. Introduction

The fashion industry is experiencing a deep transformation as sustainability concerns propel the necessity to transition to circular economy practices. The traditional linear pattern of consumption, characterized by rapid production and disposal, has resulted in textile waste, pollution, and resource depletion [

1,

2]. Amid this transition, the second-hand fashion market has emerged as a key strategy for sustainable fashion, offering a substitute for fast fashion by prolonging the lifespan of clothing, reducing textile waste, and mitigating environmental degradation [

3]. By reintegrating pre-owned clothing into the consumption cycle, resale markets contribute to reducing overproduction and lowering carbon emissions associated with new garment manufacturing [

4]. In global markets, the second-hand fashion sector has experienced significant growth. According to a Global Data report commissioned by ThredUp, the global resale market was valued at

$211 billion in 2023, reflecting a 19% year-over-year increase [

5]. Projections estimate that by 2028, the market will grow to

$350 billion, making up 10% of the total fashion industry [

5].

As the world’s largest clothing market, China faces unique challenges and opportunities in its transition to sustainable fashion. The country generates nearly 20 million tons of textile waste annually, contributing to a substantial portion of global material waste [

6]. Historically, second-hand clothing (SHC) has been associated with hygiene concerns and social stigma, which has hindered its widespread adoption [

7]. However, policy-driven sustainability initiatives, such as China’s goal to peak carbon emissions by 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2060 [

8], alongside consumers’ increasing awareness of environmental and social issues, are driving demand for alternative fashion consumption models that align with sustainability values [

9]. Research indicates that with Millennials and Generation Z emerging as dominant consumer groups, the landscape is shifting. Despite being in its early stages, China’s second-hand fashion sector holds strong expansion prospects. According to Statista’s research, China’s apparel market reached an astonishing

$326 billion valuation in 2022, reflecting the potential for second-hand fashion growth [

10]. Influenced by digital platforms, global vintage fashion trends, and increasing sustainability awareness, second-hand fashion is gaining recognition in major Chinese cities [

11]. The rise of vintage stores, online resale platforms, and upcycling brands reflects this growing acceptance.

While previous research has extensively examined Western second-hand fashion markets, focusing on consumer motivations such as economic factors, product quality, affordability, and sustainability considerations, studies on Chinese consumers, particularly younger generations, remain limited. The specific drivers and barriers that influence second-hand fashion adoption in China, as well as how these forces interact to shape consumer intentions, have yet to be fully examined. Moreover, limited research has considered the role of emerging business models in facilitating the acceptance of resale fashion among younger consumers. Addressing this gap is essential to understanding how evolving cultural values, sustainability awareness, and digital consumption habits are reshaping fashion consumption in China. Building on this context, the study focuses on emerging generations, particularly Millennials and Generation Z, as they represent a key consumer demographic driving the transition toward sustainable fashion. While Millennials were traditionally defined as those born between 1981 and 1996 [

12], this study expands the scope to include both Millennials and Generation Z to capture their influence on second-hand fashion consumption. By adopting this broader perspective, the research examines the primary factors influencing younger consumers’ willingness to purchase SHC and explores the barriers that limit its widespread adoption.

Guided by these aims, this study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1. What are the main motivations and barriers shaping Millennials’ and Generation Z’s willingness to purchase second-hand fashion in China?

RQ2. How do these drivers and barriers interact to influence young consumers’ attitudes and behavioural intentions toward second-hand fashion?

RQ3. How do different business models, such as online platforms, vintage stores, and upcycling brands, shape consumer perceptions and contribute to the broader transition toward sustainable fashion in China?

By examining these questions, this study aims to advance understanding of the behavioural and cultural dynamics underpinning sustainable fashion consumption in China and to provide empirical insights that can inform policy, education, and industry strategies promoting circularity within the fashion sector.

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodology

2.1. Consumer Motivations and Barriers in SHC Adoption

Based on the reasoned action theory, intention serves as a critical psychological mechanism that bridges motivation and observable consumer actions [

13]. Purchase intention represents a cognitive evaluation process in which individuals assess a product’s perceived utility, necessity, and emotional appeal before making a transactional decision [

14]. Several studies have shown that affordability is a key motivator for SHC consumption, especially among younger consumers seeking quality fashion at lower prices. Hur [

15] identified price sensitivity as a primary factor influencing SHC adoption, demonstrating a strong correlation between perceived cost savings and purchase intentions. Similarly, Sumo

, et al. [

16] found that financial pragmatism drives SHC purchases, particularly in areas with limited disposable income. Meanwhile, other studies have pointed out that while cost savings remain the main purchasing motivation for SHC, millennials and Generation Z are not only price-driven, but also driven by desire to maintain a fashionable and individualistic image. Sorensen and Johnson Jorgensen [

17] identified a consumer segment known as trendy economists that actively seek to balance fashion trends with budget constraints. Ferraro

, et al. [

18] pointed out that 83% of consumers are driven by the desire for fashionable items, highlighting the importance of fashionability in SHC consumption. Bly

, et al. [

19] highlighted originality, creativity, and aesthetics as primary influences on the adoption of sustainable fashion choices. Additionally, Guiot and Roux [

20] emphasized the importance of communal participation, the excitement of exploration, and interactive shopping experiences in enhancing consumer interest in SHC. These studies reveal the significance of aesthetic preferences and social interaction in sustainable fashion consumption.

Rising concerns about sustainability and ethical values have also become important drivers of SHC consumption. Lundblad and Davies [

21] highlighted the complex interplay between individual ethics and fashion choices, particularly the role of social justice ethics in supporting sustainable fashion consumption. Lee and Chen (2022) argued that SHC consumption provides psychological satisfaction, as consumers align their purchases with ethical and environmental commitments. Ciechelska

, et al. [

22] identified four key drivers of sustainable fashion adoption: awareness of industry impact, ethical fulfillment, perceived authenticity, and support for local businesses, emphasizing consumers’ growing commitment to socially and environmentally responsible choices. Taken together, these studies illustrate that SHC adoption is shaped by a combination of economic affordability, cultural identity, social influence, and sustainability motivations.

Despite growing interest in sustainable consumption, multiple challenges hinder the broad acceptance of SHC.A key concern is consumers’ hygiene-related anxieties, as many associate pre-owned garments with contamination risks or poor cleanliness. Research indicates that buyers often avoid SHC due to fears that items retain physical or symbolic traces of prior owners, reducing perceived safety and appeal [

23]. Beyond concerns over hygiene risks, negative stereotypes surrounding SHC stores further deter potential buyers. Consumers associate SHC shops with bad smells, stained garments, and disorganized store layouts, further reinforce negative perceptions and hinder the mainstream adoption of SHC [

17,

24]. Additionally, social stigma linked to second-hand consumption persists, particularly in cultures valuing collective status. For instance, in regions like East Asia, purchasing used clothing is often interpreted as financial instability rather than environmental responsibility [

25,

26]. While niche markets like vintage fashion attract style-driven consumers, mainstream adoption remains limited due to enduring cultural associations between SHC and economic disadvantage.

China’s eco-friendly fashion landscape integrates diverse models, such as online resale marketplaces, physical vintage shops, and brands focused on garment reuse and recycling. Recent studies highlight rapid growth in urban second-hand luxury markets, fueled by younger consumers prioritizing sustainability and the demand for unique fashion pieces [

27]. Digital platforms like Alibaba’s Xianyu and Tencent-backed Zhuanzhuan dominate the sector, offering accessible solutions for trading pre-owned goods. For example, Xianyu, established in 2014, has become a leading platform in China’s second-hand market [

28], while Zhuanzhuan’s acquisition of a luxury resale brand in 2023 underscores its ambition to attract high-end buyers [

23]. Beyond online spaces, boutique vintage stores cater to shoppers seeking distinctive styles, contrasting fast fashion’s uniformity. Meanwhile, innovative brands like Reclothing Bank emphasize creative material repurposing, extending clothing longevity and reducing waste [

29]. This dynamic ecosystem, combining digital convenience, curated retail experiences, and environmental innovation, reflects shifting consumer values toward sustainability and personalized consumption in China.

2.2. Methodology

This study adopts a mixed-method design to holistically examine drivers of second-hand fashion consumption in China, combining qualitative insights with quantitative validation [

30,

31]. The process includes two sequential phases: first, exploratory semi-structured interviews identify consumer attitudes and contextual challenges. These findings guide the development of a structured survey for the second phase, ensuring alignment between theoretical frameworks and empirical data. By cross-referencing interview themes with statistical results, the approach strengthens the reliability of the findings through methodological triangulation [

32]. (Johnson, 2018). Such integration addresses limitations inherent in single-method studies, offering nuanced explanations for behavioral patterns while maintaining analytical rigor.

The first phase comprises 20 semi-structured interviews. Participants were purposefully sampled, aged between 25 and 40 years, and actively engaged in second-hand fashion consumption, including Xianyu users (n=8), offline second-hand store customers (n=7), and stakeholders of upcycling brands (n=5). Recruitment was conducted through online sustainable fashion communities—including REDNote (also known as Xiaohongshu, a Chinese social networking platform combining user-generated content with digital consumption activities), WeChat groups, and Xianyu forums—as well as offline networks. The sample size was determined based on theoretical saturation [

33] to ensure that no new data would yield fundamentally novel insights. Interviews were conducted via Zoom and WeChat voice calls, each lasting between 30 and 45 minutes. The discussions were structured around four key themes: participants’ personal experiences and perceptions of second-hand fashion, motivations for purchasing SHC, barriers and challenges encountered in second-hand fashion consumption, and comparative experiences across different consumption channels (including online platforms, offline vintage stores, and upcycling brands). The transcribed interview data were analysed using NVivo to identify nodes, themes, and word frequency, employing thematic analysis to interpret the findings.

The second phase consists of a structured survey (N=306), designed based on insights from the qualitative phase. The sample profile is presented in

Table 1. The survey aims to assess the key determinants influencing purchase intentions and behaviors regarding SHC. The questionnaire is divided into two sections: (1) demographic information, including participants’ gender, age, educational background, and employment status; and (2) measurement of key factors influencing SHC purchase intention, with core variables derived from the qualitative findings. All items are measured using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, 5 = strongly agree) and adapted from established studies to ensure reliability and validity. Data analysis was conducted by SPSS, including regression analysis (examining the key factors influencing purchase intention), correlation analysis (exploring the relationship between variables) and difference analysis (identifying differences in purchase attitudes between different population groups).

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research protocol was approved by the Arts, Humanities and Cultures Research Ethics Committee at the University of Leeds (Ref. No. FAHC 22-010, approved 1 November 2022). Written informed consent was obtained from all interview participants prior to data collection. For the survey phase, participants provided informed consent electronically before accessing the questionnaire. Data were anonymised upon collection, with identifying information securely separated from response data.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Qualitative Analysis of SHC Purchase Intention

Through qualitative analysis and interview data coding, this study identified five key determinant factors that influence SHC purchase intention (as shown in

Table 2).

Economic Accessibility: Economic factors emerged as the primary driver, with 12 participants (60%) highlighting cost savings, such as lower prices compared to new clothing and the ability to manage budgets effectively.

Style and Uniqueness: Aesthetic preferences and fashion diversity played a key role in SHC adoption. 11 participants (55%) emphasized that SHC provides access to vintage designs and personalized fashion choices that are rarely available in mainstream markets.

Eco-Consciousness: Environmental consciousness was also a consideration, mentioned by 11 participants (55%); however, some participants expressed skepticism regarding the actual sustainability impact of second-hand fashion at the same time.

Shopping Experience: Experiences were mixed. Positive experiences (8 participants) included the excitement of discovering vintage pieces through a “treasure hunt” and the convenience of online platforms. In contrast, negative experiences (15 participants) were primarily related to concerns over hygiene, (“There’s no way to verify if the clothes have been properly cleaned or disinfected”), as well as restrictive return policies and the risk of counterfeit products.

Cultural and Social Influence: 10 participants (50%) indicated that recommendations from social media influencers, discussions within peer groups, and the rising popularity of vintage fashion trends directly enhanced their interest in SHC.

The qualitative findings indicate varying consumer preferences and behaviors regarding SHC purchasing channels. Participants identified online platforms (62%) and offline SHC stores (54%) as the most popular choices, followed by personal social media accounts (50%), such as WeChat Stores, REDNote, Douyin (TikTok China), and Weibo. Beyond traditional consumption models, online second-hand platforms facilitate consumer participation in circular economy practices through both buying and selling SHC. C2C platforms, such as Xianyu, serve as both resale marketplaces and sources of second-hand fashion. Some consumers use these platforms primarily for purchasing, while others engage in resale to generate additional income. A frequent Xianyu user described their transactional motivation behind SHC purchases, “I use Xianyu mainly to declutter and make some extra money. Sometimes, I come across second-hand clothes with a good price and style.”

Social media has become a highly influential platform for SHC purchases, offering curated fashion collections, direct seller interactions, and personalized recommendations. Many participants noted the efficiency and convenience of discovering SHC through influencers and community-driven platforms. A participant highlighted the role of influencers in SHC discovery, “I have been following a vintage fashion influencer on REDNote, and she has a WeChat store where I buy most of my vintage clothing.” Another participant emphasized the engagement and interactivity of social media in SHC transactions, “I like how social media provides personalized recommendations and allows me to interact with sellers directly before purchasing.” Meanwhile, the qualitative analysis also revealed challenges faced by upcycled fashion brands attempting to integrate into China’s second-hand clothing market. Emerging brands, such as Reclothing Bank, focus on transforming textile waste into high-end fashion but face significant production constraints. A designer in the upcycling industry described the difficulties of scalability and pricing, “Each upcycled coat requires extra handcrafting. Many customers say they love it, but pricing and production limitations make it difficult to scale.” Despite increased media attention, participants noted that upcycled fashion brands continue to face substantial challenges in brand operations and cost constraints.

3.2. Quantitative Validation of Key Determinants

Building on the qualitative findings, this study conducted a survey (N = 306) to further quantitatively assess the correlation between these determinants and purchase intention. A correlation analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) to examine the significance of the relationships between these key factors and purchase intention. A multiple linear regression analysis was employed to identify the key determinants influencing consumers’ SHC purchase intention.

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix among key variables. According to Pearson’s correlation analysis, all variables exhibited significant positive relationships (p < 0.01). The overall model was statistically significant (F = 22.143, p < 0.001) and explained 27.8% of the variance in purchase intention (R² = 0.278), with an adjusted explanatory power of 26.5%. This indicates that Economic Accessibility, Stylistic Identity, Eco-Consciousness, Shopping Experience, and Social Influence together form the core driving factors of SHC adoption.

Regression results revealed the relative strength of each determinant in shaping SHC purchase intention:

Social Influence was the most significant predictor (β = 0.174, p = 0.006), with a non-standardized coefficient of 0.181, indicating that for each unit increase in social recommendation strength, purchase intention increases by 0.181 units. This highlights the impact of fashion trends, social media influence, peer recommendations, and word-of-mouth effects.

Stylistic Identity (β = 0.170, p = 0.004) also played a crucial role, suggesting that the pursuit of unique and vintage fashion directly drives SHC consumption. Consumers seek individuality through SHC, integrating their fashion choices with self-expression and social validation.

Economic Accessibility (β = 0.140, p = 0.014) and Shopping Experience (β = 0.132, p = 0.033) are fundamental drivers, reflecting price sensitivity and service convenience, respectively. Cost-effectiveness remains a critical factor, while user-friendly shopping platforms and policies (e.g., logistics, return policies) enhance consumer confidence.

Eco-Consciousness (β = 0.120, p = 0.041) validates the behavioral translation of sustainability awareness into purchasing actions, suggesting that many consumers view SHC as a means of supporting environmental responsibility.

All independent variables passed the multicollinearity test, with variance inflation factors (VIF < 2) and tolerance values (> 0.6) within acceptable thresholds, ensuring the robustness of the model. Furthermore, the Durbin-Watson statistic remained close to 2, confirming that the estimated results are reliable and free from autocorrelation issues.

3.3. Synergistic Interactions Among Motivational Factors

Pearson’s correlation analysis further clarified the interrelationships among key variables (as shown in

Table 4), revealing strong synergies between different determinants:

Interaction Between Social Influence and Shopping Experience optimization (r = 0.512): The high correlation between these two variables suggests that enhancing platform services (such as transparent hygiene and sanitation measures, return policies, and improved customer experiences) can create viral spread through word-of-mouth effects.

Social Empowerment of Stylistic Identity (r = 0.439): The strong association between Stylistic Identity and Social Influence indicates that SHC is not merely a personal aesthetic choice but also a social fashion trend. Fashion individuality is increasingly validated through social media and peer recognition, reinforcing consumer motivation to explore niche fashion styles, thereby further accelerating SHC adoption.

Value Coexistence of Economic and Environmental Considerations (r = 0.382): The positive relationship between Economic Accessibility and Eco-Consciousness challenges traditional perceptions, as 61.3% of participants believe that SHC consumption simultaneously achieves the dual goals of saving money and green shopping. This reinforces the dual motivation behind sustainable consumption behaviors.

3.4. Demographic Variations in SHC Adoption

Table 5 presents the ANOVA results assessing demographic differences in SHC adoption. The findings indicate that female consumers demonstrate significantly higher purchase intentions across all key determinants compared to male consumers (p < 0.05). This disparity is particularly evident in Stylistic Identity (F = 505.852, p < 0.001) and Social Influence (F = 57.548, p < 0.001), suggesting that women are more driven by fashion uniqueness and peer influence when engaging with SHC.

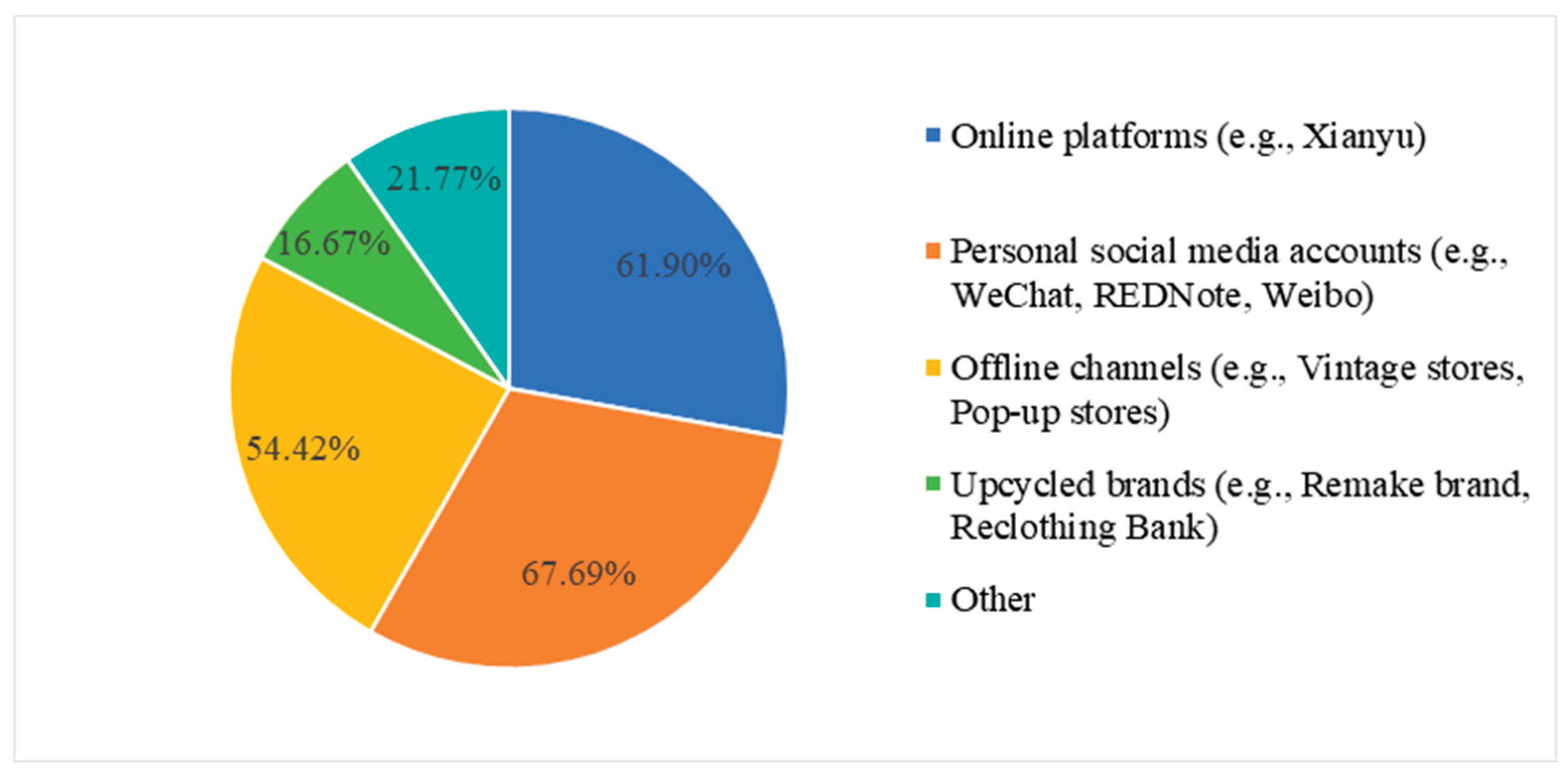

Among all purchasing channels, as shown in

Figure 1, 67.69% of participants reported using personal social media accounts (such as WeChat Stores, REDNote, Douyin, and Weibo) to buy SHC, making it the most popular option. This was followed by online platforms (61.9%) and offline vintage stores (54.42%). These findings underscore the growing role of social media in second-hand fashion, likely due to its ability to offer personalized recommendations, influencer engagement, and interactive purchasing experiences.

An age-based analysis further reveals that younger consumers (18 and below, 19-25) prefer social media-based second-hand transactions, with 67.37% and 62.14% of participants in these age groups, respectively, choosing this option. In contrast, consumers aged 26-30 and above show a relatively lower preference for social media-based transactions but exhibit a higher inclination toward offline channels (e.g., vintage stores). Notably, 43.75% of participants aged 26-30 reported purchasing second-hand fashion through offline vintage stores, a significant contrast to the younger demographic. No significant differences (p > 0.05) were found among different education levels, or occupational categories, suggesting that SHC consumption patterns remain relatively stable across these demographic variables.

4. Discussion

This study reveals the nuances of second-hand fashion consumption among Chinese millennials and Generation Z, highlighting the complex interplay between key determinants of SHC purchase intention. It illustrates how social influence, shopping experience, economic accessibility, eco-consciousness, and stylistic identity collectively shape consumer behavior.

4.1. Economic Accessibility and Pragmatic Environmentalism

While economic accessibility (β = 0.140) serves as a foundational enabler, stylistic identity and social influence emerged as stronger predictors of purchasing behavior. This finding contrasts with prior studies that emphasized price sensitivity [

34] or environmental altruism [

35]. The study indicates that although financial capacity enables purchasing power, it rarely serves as an independent motivator. Qualitative data highlight a key issue: participants acknowledge cost savings as a primary entry point for SHC but emphasize that price alone does not sustain engagement: “If it’s not a special item, I would rather buy a new product”, “Aesthetic appeal matters more than just affordability”.

Notably, the positive correlation between economic accessibility and eco-consciousness (r = 0.382) underscores a pragmatic duality, 61.3% of participants consider SHC a means of both saving money and green shopping. Chinese consumers exhibit pragmatic environmental consciousness, motivated more by waste reduction through resale than ideological environmentalism. Qualitative analysis reveals that participants generally hold a positive attitude toward SHC, particularly regarding waste reduction and support for sustainability initiatives. However, despite overall positivity, a segment of respondents expressed skepticism about SHC’s practical environmental impact. For example, one participant stated, “Buying second-hand helps reduce waste, but I’m unsure if it truly protects the environment.” These findings reveal a utilitarian green mindset, where SHC adoption is driven by practical benefits (cost, style) rather than purely ethical considerations. Retailers could therefore balance functional value with strategies to bridge the credibility gap in sustainability claims. Furthermore, the weaker regression coefficient for eco-consciousness (β = 0.120) suggests that environmental benefits still rank below social and stylistic motivations. The moderate correlation between eco-consciousness and social influence (r = 0.416) indicates that social media and peer influence play an important role in shaping environmental perceptions. Policymakers could leverage this duality by subsidizing shared economy platforms that transparently quantify environmental impact, thereby linking individual thriftiness to collective sustainability goals.

4.2. The Dominance of Social Influence and Stylistic Identity

Social influence (β = 0.174, p = 0.006) emerged as the most significant factor affecting SHC purchase intention, followed closely by stylistic identity (β = 0.170, p = 0.004). The strong correlation between stylistic identity and social influence (r = 0.439) highlights the crucial role of peer networks, influencer endorsements, and social validation in shaping fashion choices. Qualitative findings further suggest that aesthetic uniqueness profoundly impacts consumer behavior, particularly in the realm of vintage fashion. Unlike previous generations, who associated SHC with economic necessity, younger consumers reinterpret thrift shopping as a cultural identity and fashion exploration practice. Some participants actively seek second-hand fashion due to their interest in vintage aesthetics, archival fashion, or discontinued designer collections. Respondents frequently described SHC as a means of self-expression, allowing them to acquire unique, high-quality pieces not available in mainstream retail. Moreover, fashion individuality is increasingly validated through social media, where self-expression and peer recognition drive consumer participation. This finding aligns with China’s broader digital fashion ecosystem, where trend-driven consumption and influencer culture significantly impact purchasing behavior. Platforms such as REDNote, Douyin, and Weibo play a pivotal role in shaping SHC perceptions, supporting prior research on social media’s role in consumer engagement and trend diffusion.

4.3. Synergies in Platform Optimization

Analysis revealed the strongest correlation between social influence and shopping experience (r = 0.512), emphasizing the critical role of platform design in SHC adoption. Qualitative insights corroborate existing literature, identifying hygiene apprehensions and trust deficits as persistent barriers to SHC engagement, particularly due to consumers’ aversion to perceived contamination risks [

36]. Similarly, trust in sellers and platforms emerged as a crucial determinant, confirming prior research that transparent sourcing and authentication processes are essential for building consumer confidence [

37]. Therefore, reducing these barriers by verifying hygiene protocols, enhancing seller accountability and flexible return policies could increase SHC adoption.

The interplay between platform functionality and sociocultural dynamics highlights the distinctiveness of China’s SHC ecosystem. Unlike Western counterparts such as eBay or Vinted, which prioritize transactional efficiency, Chinese platforms like Xianyu and REDNote seamlessly integrate commerce with community-driven content creation. This fusion transforms SHC consumption into a culturally embedded, interactive lifestyle, where users engage in fashion discovery, peer recommendations, and creative reuse discussions. To succeed in this market, retailers could adopt dual strategies. They should optimize practical features such as authentication and logistics while leveraging Key Opinion Leaders, livestream influencers, and user-generated content to reframe SHC as a collective, trend-driven experience rather than an isolated purchasing decision.

4.4. Demographic Differences and Strategic Segmentation

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed statistically significant gender differences across several dimensions influencing second-hand fashion consumption (P < 0.05). Scores for stylistic identity (F = 505.852, p < 0.001) and social influence (F = 57.548, p < 0.001) were significantly higher among female participants, suggesting that aesthetic self-expression and socially mediated interaction play a more prominent role in their engagement with second-hand fashion. This tendency is particularly evident within digital environments where visual presentation and community interaction reinforce one another. Within hybrid social-commerce platforms such as REDNote, Douyin, WeChat Stores, and Xianyu, female-driven communities have become crucial spaces for aesthetic expression, social interaction, and sustainability-oriented discourse. These platforms combine social networking functions with second-hand retail, amplifying the visibility of sustainable fashion through participatory practices such as outfit sharing, product reviews, and peer recommendations. The prominence of these interactions indicates that gender remains a key analytical factor in understanding differences in participation and communication dynamics within China’s sustainable fashion market.

Age-related differences were also evident, especially in channel preferences. Younger participants (aged 18–25) demonstrated a stronger inclination towards social media platforms (67.37%), indicating the role of digital interactivity, peer endorsement, and influencer marketing in shaping their purchase behaviour. By contrast, older millennials (aged 30–40) exhibited a higher preference for offline second-hand stores (43.75%), valuing product authenticity, tactile experience, and interpersonal trust. These generational distinctions reflect different forms of experiential consumption shaped by digital literacy and lifestyle orientation.

From a strategic perspective, these demographic variations highlight the importance of segmented marketing approaches. For younger consumers, brand engagement may be strengthened through user-generated content, gamified sustainability campaigns, and collaborations with influencers. For older cohorts, integrating offline authenticity with online convenience, such as QR-based authenticity verification or hybrid events, could enhance trust and long-term retention. Overall, demographic segmentation in the Chinese second-hand fashion market underscores the need for differentiated communication strategies that align with both gendered motivations and generational consumption logics.

4.5. Limitations

This study acknowledges several limitations. The sample size and the use of an online survey may not fully reflect the diversity of second-hand fashion consumers. Moreover, participants’ prior experience with second-hand shopping was not explicitly measured, which could have influenced their perceptions and reported motivations. Future research should examine longitudinal changes in second-hand fashion adoption, generational differences, and the influence of emerging digital commerce ecosystems on sustainable fashion consumption in China.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the key determinants influencing second-hand clothing consumption among Chinese consumers, particularly younger generations. By integrating qualitative and quantitative methods, the research identifies economic accessibility, stylistic identity, eco-consciousness, shopping experience, and social influence as the primary factors shaping purchase intention. The findings highlight the dominance of social influence and stylistic identity, underscoring the critical role of peer networks, influencer culture, and aesthetic uniqueness in driving SHC adoption. Additionally, this study reveals the interdependence between economic and environmental motivations, where pragmatic consumers perceive SHC as a means of both saving money and contributing to sustainable consumption. Furthermore, the results demonstrate significant demographic differences in SHC adoption. Female consumers exhibit stronger engagement, particularly in fashion-driven and social validation aspects, while younger consumers show a clear preference for social media-based second-hand transactions. In contrast, older consumers are more inclined towards offline vintage stores, suggesting that different consumer segments priorities distinct purchasing channels. The correlation analysis further reveals the synergies between platform optimization and social influence, indicating that enhancing hygiene transparency, return policies, and interactive shopping experiences can significantly boost consumer confidence and engagement.

The findings provide several practical recommendations for second-hand clothing retailers, digital platforms, and policymakers to enhance sustainable fashion consumption in China. To promote second-hand clothing adoption, retailers and platforms could leverage social media engagement, collaborating with influencers on REDNote, Douyin, and Weibo, while integrating live-stream shopping, virtual try-ons, and AI-driven recommendations to enhance consumer experience. Trust and hygiene concerns can be addressed through verified seller programs, transparent authentication, and robust return policies. Marketing strategies should be tailored to consumer segments, with fashion-focused campaigns for women, economic-driven appeals for men, and multichannel approaches bridging social media and offline vintage stores for different age groups. Given the positive correlation between economic accessibility and eco-consciousness, policymakers should incentivize sustainable shopping through subsidies for circular economy platforms and eco-labelling schemes, reinforcing affordability and environmental responsibility. Implementing these strategies will strengthen consumer confidence, expand market reach, and drive SHC adoption in China’s growing resale economy.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research protocol was approved by the Arts, Humanities and Cultures Research Ethics Committee at the University of Leeds (Ref. No. FAHC 22-010, approved 1 November 2022). This research forms part of the author’s doctoral project on fashion design education in China, conducted under the broader PhD research programme examining the impact of socio-economic and cultural change on the fashion industry. All procedures complied with institutional and international ethical standards for research involving human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

References

- Fletcher, K.; Grose, L. Fashion & sustainability: Design for change; Hachette UK: 2012.

- Zamani, B.; Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Life cycle assessment of clothing libraries: can collaborative consumption reduce the environmental impact of fast fashion? Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 162. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Song, Y.; Tong, S. Sustainable Retailing in the Fashion Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2017, Vol. 9, Page 1266 2017, 9. [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.; Paulos, E. Second-hand interactions: Investigating reacquisition and dispossession practices around domestic objects; 2011; pp. 2385-2394.

- ThredUp. ThredUp 2024 Resale Report. Available online: https://cf-assets-tup.thredup.com/resale_report/2024/ThredUp_2024_Resale%20Report.pdf (accessed on February 10, 2025).

- Xu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, T.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, D. Insights into the pyrolysis behavior and adsorption properties of activated carbon from waste cotton textiles by FeCl3-activation. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2019, 582. [CrossRef]

- Cervellon, M.C.; Carey, L.; Harms, T. Something old, something used: Determinants of women’s purchase of vintage fashion vs second-hand fashion. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 2012, 40. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, R.R.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Fang, K. Multi-objective energy planning for China’s dual carbon goals. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2022, 34. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Griffiths, M.A. Share more, drive less: Millennials value perception and behavioral intent in using collaborative consumption services. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2017, 34. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. Global apparel market: projected value worldwide from 2017 until 2022, by country; Statista: 2023.

- Yao, Y.; Xu, H.; Song, H.-Y. Exploring the Key Factors Affecting Customer Satisfaction in China’s Sustainable Second-Hand Clothing Market: A Mixed Methods Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Dimock, M. Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Research Center 2019, 17, 1-7.

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. organizational behaviour and human decision processes, 50, 179-211. De Young 1991, 50, 509-526.

- Stankevich, A. Explaining the consumer decision-making process: Critical literature review. Journal of international business research and marketing 2017, 2.

- Hur, E. Rebirth fashion: Secondhand clothing consumption values and perceived risks. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 273. [CrossRef]

- Sumo, P.; Arhin, I.; Danquah, R.; Nelson, S.K.; Achaa, L.; Nweze, C.; Liling, C.; Ji, X. An assessment of Africa’s second-hand clothing value chain: a systematic review and research opportunities. Textile Research Journal 2023, 93, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, K.; Johnson Jorgensen, J. Millennial Perceptions of Fast Fashion and Second-Hand Clothing: An Exploration of Clothing Preferences Using Q Methodology. Social Sciences 2019, Vol. 8, Page 244 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, C.; Sands, S.; Brace-Govan, J. The role of fashionability in second-hand shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2016, 32. [CrossRef]

- Bly, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Reisch, L.A. Exit from the high street: an exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2015, 39. [CrossRef]

- Guiot, D.; Roux, D. A Second-Hand Shoppers’ Motivation Scale: Antecedents, Consequences, and Implications for Retailers. Journal of Retailing 2010, 86, 383-399. [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, L.; Davies, I.A. The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 2016, 15. [CrossRef]

- Ciechelska, A.; Kusterka-Jefmańska, M.; Zaremba-Warnke, S. Consumers’ motives for engaging in second-hand clothing circulation in terms of sustainable consumption. Economics and Environment 2024, 88, 632. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, P. Zhuan Zhuan: Pioneering Sustainability in Second-Hand E-Commerce: Business & Management Book Chapter | IGI Global Scientific Publishing; 2025.

- Tarai, S.; Shailaja, K. Consumer perception towards the sale of second-hand clothes in the localities of Odisha, State of India. Journal of Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology 2020, 6, 159-162.

- González, A.M.; Bovone, L. Identities Through Fashion: A Multidisciplinary Approach; Bloomsbury Publishing: 2013.

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Burman, R.; Zhao, H. Second-hand clothing consumption: a cross-cultural comparison between A merican and C hinese young consumers. International journal of consumer studies 2014, 38, 670-677.

- Wang, X.; Liang, H.e.; Wang, Z. The Emerging Fashion Market: A Study of Influencing Factors of Shanghai’s Second-Hand Luxury Consumers’ Purchasing Behavior with Grounded Theory. Sustainability 2024, Vol. 16, Page 10201 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, T.C.; Lien, C.C.; Sun, X.; Shen, C.; Shen, H. Consumer Evaluation of Xianyu E-commerce. Information Systems and Economics 2024, 5. [CrossRef]

- Finnane, A. Between Beijing and Shanghai: fashion in the party state. Paris: Capital of Fashion 2019, 116-139.

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches; Sage publications: 2017.

- Pathak, V.; Jena, B.; Kalra, S. Qualitative research. Perspectives in Clinical Research 2013, 4. [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. 4.6 triangulation in qualitative research. A companion to qualitative research 2004, 178-183.

- Charmaz, K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis; sage: 2006.

- Borusiak, B.; Szymkowiak, A.; Horska, E.; Raszka, N.; Żelichowska, E. Towards Building Sustainable Consumption: A Study of Second-Hand Buying Intentions. Sustainability 2020, Vol. 12, Page 875 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ciechelska, A.; Kusterka-Jefmańska, M.; Zaremba-Warnke, S. Consumers’ motives for engaging in second-hand clothing circulation in terms of sustainable consumption. Economics and Environment 2024, 88. [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y.; Cheah, C.W.; Lom, H.S. Does perceived risk influence the intention to purchase second-hand clothing? A multigroup analysis of SHC consumers versus non-SHC consumers. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2023, 32, 530-543.

- Rendel, E. Is Second-Hand the New Black? Understanding the Factors Influencing People’s Intention to Purchase Second-Hand Clothing through Peer-to-Peer Sharing Platforms. University of Twente, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).