1. Introduction

For the last few decades, the fashion industry has presented many innovative attempts to emphasize its environmentally friendly initiatives. The textile industry is ranked as the fourth largest industry in the world [

1] and remains one of the largest polluters of the planet [

2]. Its environmental impact is important in terms of the sustainability of our planet. Its contribution to pollution is second after the oil industry [

3]. From producing a garment to disposing of it, all the steps of the apparel industry have substantial negative effects on the planet [

4]. The fashion industry is the second biggest contributor to natural water pollution in the world due to the high amount of chemicals being used [

3]. It was responsible for at least 2.1 billion metric tons (equal to 4%) of the global greenhouse gas emissions in 2018. This level of emissions, if continued, will reach twice the limit target set by the Paris Agreement in the year 2030 [

5].

Emerging fast fashion models have transformed the way consumers buy and discard clothes. Fast fashion has significantly increased consumption by making popular styles available at cheap prices. Although hailed by some as the “democratization” of fashion by granting all consumers access to new inexpensive designs, this transition has environmental and social risks [

6]. Fast fashion has increased consumption, with prices being kept low due to contract production in countries with cheap labor. About 80 billion garments are purchased each year [

6]. The majority of these garments are made using non-biodegradable petroleum-based synthetics, creating an environmental hazard when discarded [

2]. Moreover, since the main goal is to produce more within the shortest timeframe possible, fast fashion garments are often produced in compromising environmental and social settings and under unethical work conditions [

7]. Outsourcing the production of fast fashion often occurs in developing countries, which bear the burden of environmental and health hazards of the manufacturing process, such as the pollution of water resources [

6].

Against this background, and with increasing public awareness, policy makers, regulators, and other stakeholders, including consumers, have demanded that the fashion industry should adhere to ethical and pro-sustainability logistics and measures. The fashion industry has introduced innovative measures to address sustainability from manufacturing to disposal. This includes the use of recycled fibers, the reuse of water, and improvement in workers’ conditions [

8,

9,

10]. Yet, as asserted by Pucker (2022) [

2], the sad story continues with the failure of the industry to fully meet targets due to inefficient strategies and regulations and a lack of commitment.

When looking at sustainability from a broader and more holistic perspective, consumption has gained significant attention recently. The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal no. 12, “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns”, emphasizes the need to address both consumption and production. Believing that mindful and ethical consumption is key for sustainability, this study maintains the importance of the role of consumers. Consumers’ attitudes and actions can determine whether sustainability efforts are fruitful or not. Studies have shown that even when consumers are aware and ready to contribute, several factors can hinder their actual participation or contribution to pro-sustainability efforts [

11]. This is why consumers’ roles and contributions need to be analyzed carefully.

In this paper, we bring insights from consumers as well as prominent fast fashion brands in Türkiye to discuss sustainable fashion purchase behaviors in an effort to understand and discover patterns that could promote sustainable and ethical decisions. According to Yang et al. (2017) [

12], most research studies on sustainable fashion have not thoroughly addressed developing countries. Therefore, Türkiye provides a rich context for such a study. The fashion industry in this country is one of the most vital contributors to its economy. Türkiye ranks as the fourth exporter of apparel in the world (with its share reaching 3.3% in 2020). The local market is also growing, with turnover at local retailers reaching 457% and household expenditures on clothing reaching 285% (statistics regarding the fashion industry in Türkiye were obtained from statista.com,

https://www.statista.com/topics/4844/textiles-and-clothing-industry-in-turkey/#dossierKeyfigures, and

https://www.statista.com/statistics/882430/household-spending-on-clothes-turkey, accessed on 23 November 2022). In addition, this study provides a unique approach in that it goes beyond the traditional mixed methodology in which data are collected from the same audience. This study collected its data from both consumers and experts. Given the insufficiency of previous studies in this regard, this approach helps to obtain an overall view of the situation in Türkiye, which offers a starting point for further investigation from different angles. In addition, the triangulation of data obtained from consumers and experts provides a richer understanding for further investigation and discussion.

2. Sustainable Fashion and Fast Fashion

An increasing interest in the environmental impact of industries has led to the emergence of new terms and fields of studies, such as green products, sustainability, ethical consumption, corporate social responsibility, and the circular economy. Sustainability remains a fluid and complex notion, with about three hundred definitions having been put forward [

13]. These definitions reflect a similar insight presented by the United Nations General Assembly (1987) [

14]: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [p. 43]. In the last few decades, sustainability has been studied in relation to three main aspects, namely economic, social, and environmental aspects [

15]. These three aspects include different principles, policies, methodologies, systems, and sub-systems [

16]. Publications and documents of international organizations, such as the United Nations, maintain that sustainable development should be considered holistically to include interrelated economic, social, and environmental aspects [

17]. The economic aspect refers to the profit and growth of an organization and its input into the economy. The social aspect focuses on the societal impact of an organization, such workers’ rights and safety. The environmental aspect addresses an organization’s responsibility toward the environment, including utilizing resources wisely and meeting targets [

18]. This three-dimensional approach to sustainability is called the triple bottom line (TBL) model. This model extends the conventional sustainability framework to focus on the three Ps, namely people, planet, and profit. This new framework aims to promote the type of sustainability that secures the environment, safeguards social equity, and maintains economic growth [

13,

18].

Traditionally, sustainability in fashion is considered in relation to the shortage of resources needed to produce fabric [

19]. However, considering the overall impact of the industry in all its stages [

20], this study adopted the following definition of sustainable fashion: “The variety of means by which a fashion item or behavior could be perceived to be more sustainable, including (but not limited to) environmental, social, slow fashion, reuse, recycling, cruelty-free and anti-consumption and production practices” [

21] (p. 2874). This definition allows several terms, such as ethical fashion, eco-fashion, slow fashion, and green fashion, to be used interchangeably with sustainable fashion [

21].

Fast fashion brands have been under a lot of pressure when it comes to sustainable fashion since they appear to be at the other end of the spectrum due to their goals of encouraging consumerism and viewing clothes as disposable. The word “fast” refers to “how quickly retailers can move designs from the catwalk to stores, keeping pace with constant demand for more and different styles” [

6] (p. 1). This poses a challenge to ensuring that fast fashion brands truly abide to environmental logistics since they are based on a technique of continuously introducing new models as an immediate response to consumers’ changing moods toward fashion, while maintaining a low cost and utilizing a flexible structure [

22]. This often leads to high rates of impulsive consumption and subsequent waste, leading to unsustainable outcomes [

15,

23], since cheap prices often encourage consumers to buy more and dispose more [

24]. With that being said, fast fashion seems to sustain a linear non-circular model that quickly produces large quantities of less durable clothes at low prices.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

In order to deeply understand and evaluate consumer behaviors and intentions toward sustainable fashion consumption, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) was used as the main framework of the study. This theory was developed in the 1980s in an attempt to understand the underlying causes of people’s behaviors and predict them. The TPB proposes that three key factors, including attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, can predict a person’s intention to take a certain action [

25].

The TPB is considered one of the most effective theories when it comes to analyzing behavioral decisions [

26]. Although criticized for focusing too much on consciousness and reason when making a decision, this theory remains a valid framework to study social and political phenomena and has been applied in different areas of research by many scholars [

27]. Moreover, it is one of the most prominent models frequently used by researchers to investigate behaviors related to sustainability and the environment [

28]. This theory has been adapted, and some factors have been added or highlighted more than others. In relation to sustainable fashion, researchers have extended the three main pillars of the TPB to include perceived consumer effectiveness as a fourth factor, which is argued to influence purchase intentions toward sustainable fashion.

The following sections further explain the four factors of the theory in relation to hypotheses of the current research.

3.1.1. Attitudes

Generally, studies have identified attitudes (ATTs) as an important factor that leads to higher purchase intentions toward green and sustainable products [

12]. Attitude has been defined as the level of favorability a person has toward a certain behavior [

29]. It can be regarded as an outcome of a person’s perception regarding a certain behavior and their evaluation of the consequence of performing that behavior [

25]. Within the framework of the TPB, it is argued that the more positive people’s attitudes toward the environment are, the more likely they are to purchase a sustainable product [

30]. If consumers think it is a good idea to buy green products, and if they view this action as a generator of some self-benefits, they are more likely to carry out the action. This process is also facilitated by a positive attitude toward brands that offer green products [

31]. In addition, attitudes have been identified to play a significant role in increasing consumer engagement, which in turn results in increasing purchase intentions toward sustainable fashion offerings [

32]. When compared to the other variables of the TPB, this variable has been argued to have the highest impact on purchase intentions of green products [

33]. As the majority of studies, we came across suggest a positive role of attitudes in this regard, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

Positive attitudes of Turkish consumers toward sustainable fashion have a significant effect on their purchase intentions toward sustainable fashion products.

3.1.2. Subjective Norms

Subjective norms (SNs) are mainly related to a person’s motivation to comply with pressure from significant others to behave in a certain manner. Subjective norms are argued to be a function of the interaction between the beliefs held by an individual about the extent to which significant others approve or disapprove of a behavior, or “normative beliefs”, and the individual’s own motivation to comply with such beliefs [

34,

35,

36,

37]. In this case, psychological and peer pressure play a role in shaping an individual’s intention toward a certain action [

38]. When it comes to purchase intention toward green products, research has shown that when people see others whom they view as important or whom they respect purchase green products, they are more likely to intend to buy these products [

39]. Pressure could come from family, friends, government, or social groups [

40]. Subjective norms contribute to the shaping of standards, urging people to participate in certain behaviors, including ethical consumption. This is especially evident in youth societies that promote sustainability [

32]. Although the effect of subjective norms has been found to be smaller when compared to that of attitude [

41], or even not significant [

42], in some studies, subjective norms have been identified to be the most powerful factor in shaping consumers’ purchase intentions toward sustainable fashion in other studies [

43,

44]. Given this, the second hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H2 : Subjective norms among Turkish consumers have a significant effect on their purchase intentions toward sustainable fashion products.

3.1.3. Perceived Behavioral Control

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) is subject to previous experience and perceived potential obstacles towards performing certain behaviors [

29]. It is determined by “control beliefs concerning the presence or absence of facilitators and barriers to behavioral performance, weighted by their perceived power or the impact of each control factor to facilitate or inhibit the behavior” [

45] (p. 98).

According to Ajzen (1991) [

25], a high proportion of the variance in a behavior is explained by both intentions and PBC. A review of the literature reveals an overall support of the role of PBC in enhancing purchase intentions toward sustainable products in general. Specifically, consumers who have easier access to such products will probably be encouraged to conduct an actual purchase [

46]. Nguyen et al. (2019) [

43] found a significant effect of PBC on green apparel purchase intentions. This effect was even higher than the traditionally strong effect of attitudes. Joshi and Srivastava (2019) [

32] confirmed the positive effect of PBC on purchasing intentions of sustainable clothing, concluding that consumers will be more motivated to make such a purchase when they have a higher level of certainty about it. Other studies have identified a mediation role of [

47,

48] and a moderating role [

33,

39] of PBC. A few studies did not find a significant role of PBC [

49,

50]. The majority of studies, however, confirm the positive effect of PBC on sustainable fashion purchase intentions. Consequently, the third hypothesis is proposed:

H3:

Perceived behavioral control among Turkish consumers has a significant positive effect on purchase intentions toward sustainable fashion products.

3.1.4. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness

Neumann et al. (2020) [

23] define perceived consumer effectiveness (CE) as consumers’ perception of their own capability to influence logically related problems. Consumers with high perceived CE scores see themselves as having more power in affecting the environment and related sustainable measures as a result of their consumption acts. The goal of their consumption is not limited to merely performing what they view as desirable and ethical behaviors. Rather, it extends to achieving changes in their surrounding environment [

51]. This type of consumer is socially responsible, as they consider the effects of their consumption on the public interest [

52].

Previous studies have found that people who feel that their behaviors have a positive effect on sustainable causes are highly motivated to act in a sustainable manner [

53], especially when they are certain that their behavior will make a difference [

54]. Zheng and Chi (2014) [

50] confirmed the significant role of perceived CE in positively affecting purchasing intentions in the sustainable fashion area. They concluded that consumers who feel confident that any individual contribution to this area will make a difference have a higher intention to buy sustainable apparel. Similarly, Chi et al. (2021) [

46] investigated slow fashion consumption as a part of overall sustainable fashion consumption and identified a positive significant role of perceived CE on slow fashion purchase intentions. Neumann et al. (2020) [

23] explained this, noting that consumers who feel the importance of their sustainable purchases are more motivated to conduct even more. In addition, the indirect effects of perceived CE on sustainable fashion purchasing have received a lot of interest in the literature, including its mediating effects [

20,

23,

55,

56], its moderating effects [

51], and its role in the explanation of the attitude–behavior gap [

57]. Even though earlier studies have identified perceived CE as a construct that indirectly affect intentions through attitudes, more recent studies have started to view perceived CE as a distinct factor with a direct effect towards intentions [

58]. Accordingly, the final hypothesis is proposed below:

H4:

Perceived consumer effectiveness positively influences Turkish consumers’ purchase intentions toward sustainable fashion products.

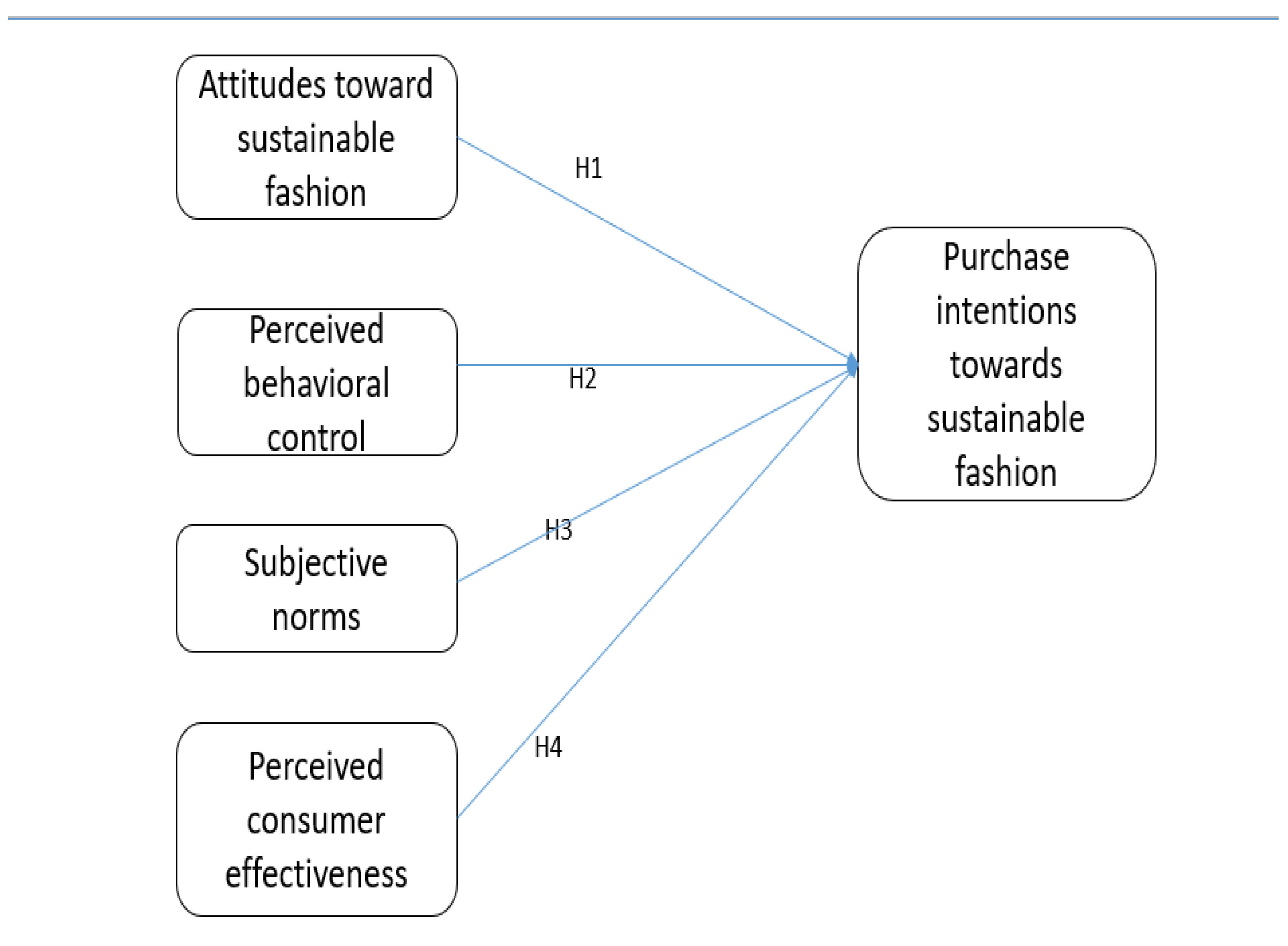

The model and the accompanying hypotheses are presented in

Figure 1. As shown in the figure, the main factors of the TPB were used to construct the model, with one major extension (i.e., perceived consumer effectiveness). All constructs were expected to significantly and directly affect purchase intentions toward sustainable fashion.

4. Research Methodology

This research utilized a mixed-methods approach, which allowed us to collect and analyze both quantitative and qualitative data in a single study. This type of research has emerged as a necessary response to the complex problems in today’s society, as responses to “these problems require amassing substantial evidence—all types of evidence gained through the measurement of precise questions, as well as more general assessment through open-ended questions” [

59] (p. 321).

This study moved beyond the “quantitative versus qualitative” debate and acknowledged the strengths of both approaches by pragmatically utilizing these methods as a third research paradigm [

60].

This study followed an exploratory sequential design [

61]. Qualitative data were first collected and analyzed, and from the findings, a quantitative phase was developed to enrich the study and assess its generalizability. The categories and insights gained from the qualitative phase assisted in the creation of the survey questionnaire.

4.1. The Qualitative Phase:

The qualitative data were gathered using semi-structured interviews. Six interviews were conducted with experts working in the sector of fashion production, sales, and marketing in Istanbul. Three respondents were the directors of the sustainability departments at three fast fashion brands in Türkiye. The other three respondents were responsible for the sales management of fast fashion brands in the Turkish market. The brands included in this study were LC Waikiki, Defacto, and Koton, these brands have more than 2000 stores combined in Türkiye (this number was obtained from the official websites of the brands,

https://corporate.lcwaikiki.com/hakkimizda, https://kurumsal.defacto.com.tr/hakkimizda.html,

https://www.koton.com/hakkimizda, accessed on 22 Sep 2022). Three interviews were conducted online via the Zoom software 5.13.5. The other three were face-to-face interviews. Five interviews were conducted in Turkish, and one was in English. Each interview was recorded using two devices.

This study used an interview guide of questions [

62] instead of a precise list of questions which encouraged a conversational approach. Each interview covered the following themes:

The rationale and motivation of the brands to go sustainable

The kinds of pro-sustainability procedures applied by the brands.

The extent to which these brands see themselves as sustainable

The perceptions of the brands of the role of the Turkish consumers’ behavior regarding sustainable fashion.

The prospect of sustainable fashion in Türkiye including opportunities and challenges the

Following the “smooth verbatim transcript” method [

63], a transcript was developed using Microsoft Word. The transcribed documents were then translated into English. A manual analysis followed using the thematic analysis method, which is “a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” [

64] (p. 79). The researchers read through the original and translated text documents several times to discover patterns and to generate categories. Major themes and subthemes were then identified from the categories.

4.2. The Quantitative Phase

Quantitative data were collected using a survey questionnaire. The scales used in the survey questions were developed by combining scales existed in literature that used TPB and addressed similar concerns [

20,

48,

65,

66,

67,

68]. As a result, a total of 6 items for ATTs, 5 items for SNs, 3 items for PBC, 3 items for CE and 5 items for purchase intentions (PI) combined to provide the measurement tool that was used in the survey. In using the Likert-scale technique, each construct of the model was evaluated using multiple items that contained statements with five response options ranging from “totally agree” to “totally disagree”. Three professors from Turkish universities provided feedback on the construction of the survey. Then, a pilot study with four respondents was conducted to ensure that the questions were understood and that the desired meaning was correctly conveyed. It was assured that these four respondents were consumers of sustainable fashion. The survey was distributed from January to February in 2023. Turkish individuals living in Istanbul were invited to participate in the survey using a convenient sampling method. Five shopping malls in different locations in Istanbul were selected to collect the data. The recruiters were informed initially that participation in the survey was anonymous and voluntary and included no rewards. All participants were above 18, residing in Istanbul and were familiar with sustainable fashion. The first question of the survey asked participants whether they bought or would buy sustainable fashion. All those who answered ‘no’ to that question were not included in the study. In studies using structural equation models (SEMs), the minimum sample size should be larger than 200, according to Kline (2011) [

69], or ranges between 200 and 400, according to Hair et al. (2010) [

70]. In this study, 268 complete survey responses were collected from a total of 311 participants. Forty-three respondents were excluded from the study due to incomplete or unclear responses.

For data analysis, the study used Spss and Amos software to establish a structural equation model. exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was first applied along with checking for reliability and validity. Then measurement model was applied by using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In the process, model fit was checked along with convergent and discriminant validity. Finally, in order to test hypotheses, a structural model was established and p values were generated in order to test the significance values of the relations.

4.3. Ethical Considerations

The researchers followed all the required ethical procedures informed by the university and the guidelines followed by PhD studies. The study obtained ethical approval from the academic supervisors and the host university’s doctoral studies committee. The study did not deal with vulnerable groups or minors. All participants were adults and were informed about the study, the research questions, and the anonymity of their participation. Consent was implied by participants when approving to take part in the survey which had a brief introduction about the research on the front page. Interviewees were informed about the research via email or by phone and at the beginning of the interview. Verbal consent was obtained and all participants were given the chance to withdraw from participating or to remove any information that was recorded.

5. Results

5.1. Qualitative Findings

Coming from mostly the “expert” side of the fashion industry, the qualitative data provided a perspective that enriched the quantitative data. In addition, using a mixed-method approach enabled us to go back and forth between different kinds of data. The interviewees revealed that sustainable fashion in the country is still in its inception phase, characterized by a desire to join the international sustainability project but lacking clear legislations and robust leadership. There is a lack of clarity about what sustainability really implies, with most efforts directed at using raw materials. In terms of a holistic framework of sustainability, the interviewees presented a limited perspective, focusing mainly on environmental sustainability practices but ignoring economic and social aspects. While our focus was to obtain insights about consumers, the following themes also emerged from the interviews:

Consumers and consumption: When addressing the consumption phase and consumers, all respondents agreed on the need to address consumers as an important stakeholder group in the sustainable fashion project in Türkiye. All respondents believe that Turkish consumers have low or inadequate knowledge of sustainability. Some referred to exceptional young voices that show a higher level of awareness:

I think Turkish customers’ consciousness level at the moment, I think, even less than 1%. We put labels on the products. […]. We say that these products save this much water or make that much contribution, but really the customers are not very aware of it” [R3].

The respondents seemed to doubt that any level of knowledge about sustainability will have a sizable impact because it is superficial and lacks the functional aspect. Even if consumers have positive attitudes about sustainability and green products, when it comes to actual purchasing behaviors, many issues are involved, such as price. Consumers also have doubts about the quality of a product with a sustainability label, branding it as “dirty” or from “garbage” materials.

People see (recycled products) as garbage or something dirty. In other words, in the research we done, for example, nobody wants recycle (garment), that is, most people do not want to buy recycle because they act as if a different treatment was done here. They think it’s dirty. That is why I believe we should raise awareness about circular economy” [R1].

According to the respondents, this lack of awareness resulted in little demand for green products and a smaller market for sustainable items in Türkiye. In a developing country, price seems to be a barrier to purchasing a pricier sustainable garment. The respondents believed that when Turkish consumers do buy sustainable products, this purchasing behavior is mainly prompted by consumers’ health concerns and less so by ethical or sustainable reasons. For instance, several respondents referred to Turkish parents’ eagerness to purchase “organic” clothes for their babies as a healthier option. One respondent also referred to a significant increase in organic underwear sales for women during the COVID-19 pandemic, clarifying that this was possibly due to a preoccupation with well-being and health aims.

Sustainable Fashion in Türkiye: The State of the Art: Although an interviewee stated that “Turkish brands are definitely starting to go sustainable” [R5], a general overview of the situation is that Türkiye is still in its primary steps, with signs of gradual development in this area. One respondent explained: “There are investments [of sustainable fashion], but I don’t think it’s enough, we are at the very beginning. […], there is a lot to do, a lot of work needs to be done” [R3].

Motivation to Become Sustainable: According to the interviewees, there are different reasons that motivate Turkish brands to move in a more sustainable direction. However, improving a brand’s image seems to be one of the most important motivations in this regard: “Here I can say mainly it is about providing better image not to actually satisfying a customer need” [R6]. The data, however, still show some respondence to customers’ needs. An example is shown by [R5], who explained that parents are attracted to organic products and perceive such products to provide healthier conditions for their children.

Challenges and prospects: Three main challenges appeared clearly within the experts’ insights. These include the higher cost of sustainable fashion production, the lack of government support, and supply chain problems. Similarly, the data reveal three major prospects as well: increasing awareness among the younger generation, decreasing costs as sustainable production increases, and the strategic importance of Türkiye in terms of resources.

5.2. Quantitative Findings

5.2.1. Sample Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 shows a brief summary of the survey sample’s distribution in terms of demographics. The table shows a relatively balanced distribution between males and females. In addition, the majority of the sample were younger participants. Education, on the other hand, is balanced. Finally, the middle-income classes (that is between 5,000 and 30,000 TRY had a higher number of participants in this sample.

5.2.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Due to the exploratory nature of the research, the first step was to apply an explanatory factor analysis (EFA). The standard procedures of an exploratory factor analysis were applied on the data in order to evaluate the measurement model. With the help of SPSS, factor loadings were calculated using the rotated component matrix technique. The loading of an absolute value of more than 0.4 had to be kept [

71]. This condition is satisfied as shown in

Table 2. In addition, the correct items were loaded on the intended factors. In addition,

Table 2 shows that the reliability test results based on the Cronbach’s alpha (α) method are satisfactory as all values exceed the rule-of-thumb value of 0.7 [

70].

In addition, KMO and Bartlett’s tests were conducted, and the results shown in

Table 3 are accepted as satisfactory [

70].

5.2.3. Measurement Model

To establish a measurement model, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the AMOS software, and a model fit was tested, and satisfactory results were obtained: CMIN= 419.838; CMIN/df ratio = 1.999; GFI = 0.881; CFI= 0.94; and RMSEA = 0.061. Regarding validity, convergent validity was also tested, as shown in

Table 4. According to the results, convergent validity was achieved since all paths were significant and the t-value was greater than 2. In addition, the average variance extracted was also used to measure convergent validity. As a rule of thumb, the AVE for a given construct needs to be more than 0.5 [

70]. As shown in

Table 4, only one construct fell just below this threshold. However, according to Bettencourt (2004), this is still acceptable since the AVE is higher than 0.4 and the corresponding CR value is high [

72]. The discriminant validity was also tested using CFA. Specifically, the maximum shared squared variance (MSV) was compared to the AVE for each given construct. As the MSV for all the constructs was lower than the AVE, we could argue that the discriminant validity was satisfactory [

70].

5.2.4. Structural Model

Once the measurement model is proven to have good fitness, it is recommended to test the structural model and the proposed hypotheses [

70]. To proceed with testing the structural model, the AMOS software was used to establish a structural equation model (SEM). SEM can have multiple advantages, including transforming theory into a relationship between latent and measured variables [

70] and conferring the ability to control a considerable number of variables [

73]. Using the theoretical framework of the TPB, a structural model was established. AMOS was used to analyze the model fit. According to the results, the model provided a good fit: x 2 (421.958) = 284.00, x 2/df ratio= 2.009; GFI = 0.88; CFI = 0.94; and RMSEA = 0.061.

5.2.5. Hypothesis Testing

Table 5 indicates that all four hypotheses found enough support in the data. The most significant predictor of purchase intentions was attitudes, followed by perceived consumer effectiveness, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.

H1: The first hypothesis was clearly supported by the results.

Table 5 shows that the t-value (critical ratio of regression weight, CR) is 6.35, with a standardized coefficient of 0.554, indicating that an increase of 1 in the standard deviation (SD) of attitudes would result in a 0.554 increase in the standard deviation of purchase intentions. This value shows that the effect of attitudes is the strongest of all factors, which is in line with the findings presented by Sreen et al. (2018) [

33]. Moreover, the p-value is less than 0.05, which indicates significant support for the hypothesis. As mentioned earlier, this result is supported by previous research results, which confirm the positive and strong role that attitudes play in shaping consumers’ intentions toward purchasing sustainable fashion products [

23,

30,

31,

32,

33,

42,

43,

44,

50,

57,

66,

74,

75,

76].

H2: The results also supported the second hypothesis, indicating a significant positive relationship between subjective norms and purchase intentions. When the SD of subjective norms of Turkish consumers increases by 1, the value of the SD of their purchase intentions toward sustainable fashion increases by 0.136. The t-value is 2.264, and the p-value is less than 0.05; thus, the hypothesis is supported. Our study result is in line with the findings of many previous studies that have confirmed the role that subjective norms play towards purchase intentions. Even though the effect is smaller compared to attitudes, Turkish consumers seem to be influenced by peer pressure and other social factors in a significant manner. The smaller effect can be explained using the argument of Ham et al. (2015) [

42] who state that sustainable fashion is a concept that is relatively new. Hence, social factors may play loss rolls here. The majority of studies, however, confirm the significant effect of subjective norms [

32,

33,

36,

37,

38,

39,

41,

43,

44,

66,

67].

H3: Support was also found for Hypothesis 3. The SD of the purchase intentions of Turkish consumers toward sustainable fashion increases by 0.124 when the SD of their PBC increases by 1. The CR is 2.26 and the p-value is less than 0.05, indicating significant support for this hypothesis. This result is in line with the findings reported in the literature [

32,

33,

39,

43,

46,

47,

48,

50], showing the important role of PBC in shaping consumers’ purchase intentions.

H4: The fourth hypothesis was also supported. Turkish consumers’ intentions toward buying sustainable fashion increase when they believe that they could make a contribution to the cause with their purchase. This result involving an extension of the main factors of the TPB is also supported by earlier studies [

20,

23,

46,

50,

53,

54,

55,

56]. The results presented in

Table 5 show a t-value of 3.44 and a p-value of less than 0.05. As the standardized coefficient value is 0.311, an increase of 1 SD in perceived CE results in a 0.311 increase in the SD of purchase intentions.

6. Discussion

While similar mixed-method studies, such as that conducted by Tran et al. (2022) [

77], have collected quantitative and qualitative data from consumers when investigating the key factors of the TPB, this study is unique in its approach by combining quantitative data from consumers and qualitative data from experts in the fast fashion sector in an effort to provide an outsider perspective in the interpretation of the TPB factors to avoid bias as much as possible. However, we also acknowledge the potential bias that can occur when bringing together data from different stakeholder groups with possibly competing interests (consumers and brands). Therefore, we tried to minimize this bias by continuously interrogating the source of the data and the positionality of each interviewee.

İn general, since consumers could be biased in their answers regarding sustainability because it appears to be the desirable and ethical thing to act sustainably, the qualitative phase aimed to identify what is really happening in the purchasing area.

Both the quantitative and qualitative data support that consumers’ attitudes and perceived consumer effectiveness influence their purchase intentions. The most prominent notion in the data is the direct association of consumers’ perception of healthy lifestyles and well-being with buying sustainable items. Taking environmental ethics into consideration, this attitude toward sustainability could be attributed to anthropocentric thinking, which claims that the environment should be saved because it is useful for humans. On the other end of the spectrum of environmental ethics stands biocentrism and eco-centric rationales, which argue that other beings have their own inherent values that are independent from what humans see as useful, and therefore, we are all ethically responsible for protecting them regardless of how useful or useless they are to us. This discussion can be enriched by studying consumer values, which is beyond the scope of this study. Although culture can impact people’s attitudes, the significant role of attitudes in creating a higher level of purchase intentions toward sustainable products has been reported in several comparative studies across cultures [

44,

50,

67].

While the quantitative data support that consumers’ intentions are influenced by their peers and family, it can be argued that since sustainability is still a new phenomenon in Turkish society, as explained by the interviewees, subjective norms may not be a strong predictor. Varshneya et al. (2017) [

42] did not find a significant effect of social norms on purchase intentions when they analyzed consumer behavior toward purchasing organic apparel. They attributed this to the fact that organic fashion products are newly introduced to the market and have not yet gained a position as a mainstream social norm.

In their study on sustainable consumption, Ayar and Gürbüz (2021) [

78] reported that PBC had an influence on intention but not on behavior, suggesting that this was due to consumers’ insufficient knowledge about sustainable behavior. In this study, the qualitative data provide further explanations of the barriers that could hinder purchase intentions.

Clearly, one of the obstacles is a lack of knowledge and sufficient information for consumers to understand and differentiate between sustainable and non-sustainable products. Most research studies on sustainable fashion have yielded similar results regarding the impact of a lack of knowledge on consumers’ purchase intentions toward sustainable products [

30,

46,

50,

66,

77,

79]. However, even when consumers have access to information, there seems to be some misinformation and misunderstanding. In fact, the qualitative data show that both consumers and experts from fast fashion brands have misconceptions about sustainable fashion. According to experts, some consumers believe that some sustainable garments are made from “dirty” or “garbage” materials and, thus, are of low quality. While the majority of studies maintain that sustainable fashion is perceived as high quality by consumers, associating sustainable garments with a lower quality was also reported by Tran et al. (2022) [

77] in a study conducted in Vietnam. This could be due to a lack of clear information on sustainable fashion in developing countries. On the other hand, even manufacturing brands also show a lack of understanding of what sustainable fashion really is. The majority of brands equate sustainable fashion with using organic raw materials and focus only on the environmental aspect of sustainability without aiming any other aspects. It can be concluded that, whether intentionally or unintentionally, brands commit greenwashing. While there is not a single definition of greenwashing, it implies different procedures that a firm can engage in to look environmentally friendly without being so, for example, by choosing to show the bright side and not disclosing the negative information [

79]. Relying on the “six sins of greenwashing” criteria developed by TerraChoice, Ecevit [

80] (2023) studied 25 Turkish apparel brands. The sins are summarized as follows: “Sins of Hidden Trade-off, Sins of No Proof, Sins of Vagueness, Sins of Irrelevance, Sin of Lesser of Two Evil, and Sin of Fibbing” (pp. 36–37). The author concluded that only five brands conducted sustainability activities (they had an existing sustainability department or division), but only one brand did not commit the sins of greenwashing. According to De Freitas Netto et al. (2020) [

79], green skepticism goes hand in hand with greenwashing, hindering the marketing of real sustainable products since it is hard for consumers to judge the reliability of green campaigns.

Data obtained from experts show that the brands themselves admit that they engage in sustainable procedures merely “for show” and to display a positive image. They promote organically manufactured children’s garments by stressing the health benefits that attract caring parents, while hiding information about the lack of social sustainability that could disturb the perfect image. According to Wolf (2013) [

81], firms can opt for certain procedures to look sustainable in order to sustain a positive image. Other motivations include to enhance the company’s financial performance [

82,

83,

84], to win in the competitional race between businesses, and to avoid any legal responsibility [

85]. Coupled with a lack of robust accountability and criminal responsibility in the country, this can lead to consumers questioning sustainable labels and claims. It can be inferred from the qualitative data of this study that brands can also justify greenwashing by blaming consumers since Turkish consumers lack the knowledge, awareness, interest, or intention to buy sustainable products.

Moreover, the qualitative data show that experts believe that Turkish consumers, regardless of how favorable their attitudes toward sustainability are, will not choose to pay more for a sustainable garment because they have other priorities to attend to. The data collected from qualitative path reveal that there is a small niche market of sustainable fashion in Türkiye that caters to a small number of rich and educated elites. Some research studies have suggested that the smaller size of the sustainable fashion market compared to the fast fashion market is what separates the fashion industry into two sides that go in different directions [

86,

87,

88]. While fast fashion focuses on encouraging purchases at all times and following rapidly changing styles, the essential nature of sustainable fashion is to encourage consumption only when needed [

89]. This alone poses a great challenge for fast fashion brands to genuinely adhere to sustainability goals since it goes against their inherent nature and aims. Realizing this ethical conflict, consumers’ distrust in sustainable labels is understandable.

7. Limitations and Future Research

A limitation of this study is that the TPB is context specific as it focuses on individual beliefs, and the findings may differ from one context to another.

This study only studied intentions toward sustainable fashion consumption. Future research should look into actual consumption behaviors and whether and to what extent intentions can influence actions to obtain a more comprehensive picture of sustainable fashion consumption in the country. Moreover, sustainable consumption includes a wide range of issues, including purchasing behaviors, purchase frequency, mending items, recycling, and disposal. These are all aspects that are worthy of investigation to further understand sustainable fashion consumption. Future studies can build on previous studies [

90] that investigate the TPB as well as the role of personal values to understand purchase behaviors since an individual’s values impact their intentions.

8. Conclusions and Implications

By employing a mixed-methods approach and drawing on the TPB to investigate Turkish consumers’ purchase intentions, this study shows that the four proposed factors of the TPB have a significant role in affecting and predicting consumers’ purchase intentions of sustainable fashion. This study, however, suggests that these factors alone are not sufficient to predict behaviors, which are often hindered by barriers such as a lack of information, misinformation, greenwashing, a lack of trust, and high costs. This study highlights some gaps between consumers’ perceptions of sustainable fashion and the perceptions of manufacturers and marketers and recommends engaging consumers as key stakeholders in any green initiative. In addition to providing further support regarding the ability of the TPB factors in predicting intentions, this study also makes an important contribution by providing an overall investigation of the situation in Türkiye, which offers researchers different directions for inspection and analysis in future research.

This study has several important practical implications. The findings can help fashion companies develop more comprehensive strategies to achieve the adoption of sustainable fashion consumption by taking into account consumers as an important stakeholder group. Sustainable fashion needs to adopt a consumer-oriented approach to better understand and implement sustainability. This study is in agreement with Sheth et al. (2011) [

91]’s model of a customer-focused approach to sustainability. Seth et al. (2011) [

91]’s study directs attention to how the majority of sustainability approaches do not address consumers. They argue that “a weak customer focus seriously restricts both the efficiency and the effectiveness of sustainability efforts” (p. 23). This study, thus, provides recommendations and data on the factors that influence consumers’ purchase intentions, which can help companies develop effective consumer-centric approaches.

Fashion producers and retailers should realize the importance of raising awareness of the urgency of sustainable choices among consumers. Consumers should have easy access to sustainable products and clear guidelines on what being sustainable really means and what it can potentially do. In their campaigns, fashion companies should prioritize attitudes and values that are important to Turkish consumers. Social media and influencers can be employed to make an impact. However, spreading the word is not enough to predict purchasing. Sustainable products themselves should be addressed in terms of quality, design, durability, and cost. Arguing that the characteristic of a sustainable product itself has more predictable power for consumers’ behavioral intention, Tran et al. (2022) [

77] suggested that fashion brands invest less in awareness campaigns and more in improving their sustainable products.

Among the brands included in the study, sustainable leadership seems to lack power, and only one brand is involved in actual auditing for sustainability. Governmental and non-governmental bodies should provide economic and technological support and guidance to existing and emerging fashion companies to ensure sustainable measures and avoid greenwashing. Ensuring accountability and liability should also be a priority. Consumers should be informed about each company’s sustainable auditing and achievements to ensure trust and prevent green skepticism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, : Shehneh, M. and Kachkar, O.; methodology, : Shehneh, M. and Kachkar, O.; software, Shehneh, M..; validation, : Shehneh, M.; Kachkar, O.; Salman, G..; formal analysis, Shehneh, M. and Kachkar, O.; investigation, Shehneh, M. resources, Salman, G..; data curation, Shehneh, M.; writing—original draft preparation Shehneh, M. and Kachkar, O.; writing—review and editing, M.; Kachkar, O.; Salman, G visualization, Shehneh, M.; supervision, M.; Kachkar, O.; Salman, G.; project administration, M.; Kachkar, O.; Salman, G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vilaça, J. Fashion Industry Statistics: The 4th Biggest Sector Is Way More Than Just About Clothing. Fashion Innovation. 2002. Available online: https://fashinnovation.nyc/fashion-industry-statistics/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Pucker, K.P.; The myth of sustainable fashion. Harvard Business Review. 2022. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/01/the-myth-of-sustainable-fashion (accessed on 7 Jan 2022).

- Conca, J.; Making climate change fashionable—The garment industry takes on global warming. Forbes. 2015. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesconca/2015/12/03/making-climate-change-fashionable-the-garment-industry-takes-on-global-warming/?sh=3e07322279e4 (accessed on 30 Jan 2023).

- Shen, B.; Li, Q.; Dong, C.; Perry, P. Sustainability issues in textile and apparel supply chains. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, K.; Granskog, A. Sustainable fashion: How the fashion industry can act urgently to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Mckinsey & Companey, 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-live/webinars/sustainable-fashion-how-the-fashion-industry-can-urgently-act-to-reduce-its-greenhouse-gas-emission (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Bick, R.; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wren, B. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion Industry: A comparative study of current efforts and best practices to address the climate crisis. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2022, 4, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandual, A.; Pradhan, S. Fashion brands and consumers approach towards sustainable fashion. In Fast Fashion, Fashion Brands and Sustainable Consumption; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvanimoghaddam, K.; Motamed, B.; Ramakrishna, S.; Naebe, M. Death by waste: Fashion and textile circular economy case. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.; Zhang, L. Innovative sustainable apparel Design: Application of CAD and redesign process. In Sustainability in the Textile and Apparel Industries: Sustainable Textiles, Clothing Design and Repurposing; Muthu, S.S., Gardetti, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- D’Astous, A. and Legendre, A. “Understanding consumers’ ethical justifications: A scale for appraising consumers’ reasons for not behaving ethically”. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.C. Effects of green brand on green purchase intention. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M.S. Sustainability: An overview of the triple bottom line and sustainability Implementation. Int. J. Strateg. Eng. 2019, 2, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Brundtland report, 1987. Available online: https://www.are.admin.ch/are/en/home/media/publications/sustainable-development/brundtland-report.html (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Presley, A.; Meade, L.M. The business case for sustainability: An application to slow fashion supply chains. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2018, 46, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavič, P.; Lukman, R. Review of sustainability terms and their definitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traer, R. Doing Environmental Ethics, 3rd ed.; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Alhaddi, H. Triple bottom line and sustainability: A literature review. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2015, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulina, S. Making Jeans Green: Linking Sustainability, Business and Fashion; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peleg Mizrachi, M.; Tal, A. Regulation for promoting sustainable, fair and circular fashion. Sustainability 2022, 14, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Liu, C.; Kim, S.H. Environmentally sustainable textile and apparel consumption: The role of consumer knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness and perceived personal relevance. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukendi, A.; Davies, I.; Glozer, S.; McDonagh, P. Sustainable fashion: Current and future research directions. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 2873–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adıgüzel, F.; Linkowski, C.; Olson, E. Do sustainability labels make us more negligent? Rebound and moral licensing effects in the clothing industry”. In Sustainability in the Textile and Apparel Industries Consumerism and Fashion Sustainability; Muthu, S.S., Gardetti, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, H.L.; Martinez, L.M.; Martinez, L.F. Sustainability efforts in the fast fashion industry: Consumer perception, trust and purchase intention. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 12, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Amatulli, C.; Pinato, G. Sustainability in the apparel industry: The role of consumers’ fashion consciousness. In Sustainability in the Textile and Apparel Industries Consumerism and Fashion Sustainability; Muthu, S.S., Gardetti, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Luo, X.; Riaz, M.U. On the Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke HA, M. Explaining Proenvironmental Intention and Behavior by Personal Norms and the Theory of Planned Behavior1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2505–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Motivating sustainable consumption. Sustainable Development Research Network. 2005. Available online: https://timjackson.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Jackson.-2005.-Motivating-Sustainable-Consumption.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Beck, L.; Ajzen, I. Predicting dishonest actions using the theory of planned behavior. J. Res. Personal. 1991, 25, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, K.; Kinley, T. Green spirit: Consumer empathies for green apparel. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Srivastava, A.P. Examining the effects of CE and BE on consumers’ purchase intention toward green apparels. Young Consum. 2019, 21, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behaviour; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, M. The effects of subjective norms on behaviour in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. British J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 48, 649–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F. The impacts of perceived moral obligation and sustainability self-identity on sustainability development: A theory of planned behavior purchase intention model of sustainability-labeled coffee and the moderating effect of climate change skepticism. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2404–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A. Green Apparel Buying: Role of Past Behavior, Knowledge and Peer Influence in the Assessment of Green Apparel Perceived Benefits. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon Kim, H.; Chung, J. Consumer purchase intention for organic personal care products. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.-M.; Wu, K.-S.; Liu, H.-H. Integrating Altruism and the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Patronage Intention of a Green Hotel. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, M.; Jeger, M.; Frajman Ivković, A. The role of subjective norms in forming the intention to purchase green food. Econ. Res. -Ekon. Istraživanja 2015, 28, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshneya, G.; Pandey, S.K.; Das, G. Impact of Social Influence and Green Consumption Values on Purchase Intention of Organic Clothing: A Study on Collectivist Developing Economy. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen MT, T.; Nguyen, L.H.; Nguyen, H.V. Materialistic values and green apparel purchase intention among young Vietnamese consumers. Young Consum. 2019, 20, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.B.; Jin, B. Predictors of purchase intention toward green apparel products. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 21, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, E.D.; Kasprzyk, D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. İn Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Wiley: San Francesco, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, T.; Gerard, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y. A study of U.S. consumers’ intention to purchase slow fashion apparel: Understanding the key determinants. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2021, 14, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatu VM, H.; Nik Mat, N.K. The Mediating Effects of Green Trust and Perceived Behavioral Control on the Direct Determinants of Intention to Purchase Green Products in Nigeria. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.C. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Investigate Purchase Intention of Green Products among Thai Consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chi, T. Factors influencing purchase intention towards environmentally friendly apparel: An empirical study of US consumers. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2014, 8, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currás-Pérez, R.; Dolz-Dolz, C.; Miquel-Romero, M.J.; Sánchez-García, I. How social, environmental, and economic CSR affects consumer-perceived value: Does perceived consumer effectiveness make a difference? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, E. Webster, Determining the Characteristics of the Socially Conscious Consumer. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, P.; Maklan, S. Feelings that Make a Difference: How Guilt and Pride Convince Consumers of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Consumption Choices. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnear, T.C.; Taylor, J.R.; Ahmed, S.A. Ecologically Concerned Consumers: Who are They? J. Mark. 1974, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, R.B.; Vann, R.J.; Mittelstaedt, J.D.; Murphy, P.E.; Sherry, J.F. Changing the marketplace one behavior at a time: Perceived marketplace influence and sustainable consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1953–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.H. The Influence of LOHAS Consumption Tendency and Perceived Consumer Effectiveness on Trust and Purchase Intention Regarding Upcycling Fashion Goods. Int. J. Hum. Ecol. 2015, 16, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, I.E.; Corbin, R.M. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Faith in Others as Moderators of Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1992, 11, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Garett, A.L. The “movement” of mixed methods research and the role of educators. South Afr. J. Educ. 2008, 28, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publication, Inc.: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution; Sprınger: Dordrecht, The, Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. The Green Purchase Behavior of Hong Kong Young Consumers: The Role of Peer Influence, Local Environmental Involvement, and Concrete Environmental Knowledge. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2010, 23, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, J.; Lee, M.Y.; Jackson, V.; Miller-Spillman, K.A. Consumer willingness to purchase organic products: Application of the theory of planned behavior. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2014, 5, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, C.; Dong, H.; Lee, Y.A. Factors influencing consumers’ purchase intention of green sportswear. Fash. Text. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al Zubaidi, N. The relationship between collectivism and green product purchase intention: The role of attitude, subjective norms, and willingness to pay a premium. J. Sustain. Mark. 2020, 1, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rosebush, Mike. Validations of the “Character Mosaic Report” Retrieved January 1, 2016. 2011. Available online: http://www.usafa.edu/Commandant/cwc/cwcs/docs/ Mosiac_Coaching/Char_Mosaic_Validation_2012.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Byrne, B.M. (2010). Structural Equation Modeling with Amos: Basic Concepts,Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Oh, K.W. Influencing Factors of Chinese Consumers’ Purchase Intention to Sustainable Apparel Products: Exploring Consumer “Attitude–Behavioral Intention” Gap. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ismail, N.; Ahrari, S.; Abu Samah, A. The effects of consumer attitude on green purchase intention: A meta-analytic path analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmed, I. Determinants of Pakistani consumers’ green purchase behavior: Some insights from a developing country. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, K.; Nguyen, T.; Tran, Y.; Nguyen, A.; Luu, K.; Nguyen, Y. Eco-friendly fashion among generation Z: Mixed-methods study on price value image, customer fulfillment, and pro-environmental behavior. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayar, I.; Gürbüz, A. Sustainable Consumption Intentions of Consumers in Turkey: A Research Within the Theory of Planned Behavior. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas Netto, S.V.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; Soares, G.R.D.L. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. The Relationship Between Sustainable Supply Chain Management, Stakeholder Pressure and Corporate Sustainability Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 119, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecevit, M.Z. Sustainability promises of Turkish origin apparel brands in the context of greenwashing. Galatasaray University Managerial and Social Sciences Letters. 2023, 1, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváthová, E. Does environmental performance affect financial performance? A meta-analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 70, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.A.; Lenox, M.J. Does it really pay to be green? An empirical study of firm environmental and financial performance: An empirical study of firm environmental and financial performance. J. Ind. Ecol. 2001, 5, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; van Phu, N.; Azomahou, T.; Wehrmeyer, W. The relationship between the environmental and economic performance of firms: An empirical analysis of the European paper industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2002, 9, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefko, R.; Steffek, V. Key ıssues in slow fashion: Current challenges and future perspectives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.; Moore, R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. Sustainable development of slow fashion businesses: Customer value approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.S.; Snowdon, J. Slow fashion—Balancing the conscious retail model within the fashion Marketplace. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchiraju, S.; Fiore, A.M.; Russell, D.W. Sustainable fashion consumption: An expanded Theory of Planned Behavior. In Proceedings of the International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings, Honolulu, Hawai, 14–17 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sethia, N.K.; Srinivas, S. Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).