1. Introduction

Urban flooding has long been considered one of the most severe environmental-social hazards, causing significant losses of life and property, interrupting production- business activities, and adversely affecting community well-being [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. According to statistics from the United Nations and many international organizations, floods and inundation accounted for approximately 44% of all natural disasters during 1970–2019 and caused over 31% of total global economic losses [

7]. In the period 2010–2019 alone, 1,298 major floods occurred worldwide [

8]. In tropical regions, the frequency of major floods quadrupled between 1985 and 2015, while global flood risk increased by 20–24% from 2000 to 2018 [

9,

10,

11]. These figures indicate that flood risk is increasing rapidly under the combined impacts of climate change and urbanization, creating an urgent need for sustainable disaster risk management [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

The reasons for urban flooding are not only extreme rainfall events but also stem from many complex anthropogenic factors, such as unplanned urban growth [

17], changes in land use and surface coverage [

18], degradation of urban ecosystem [

19], outdated or non-uniform drainage systems [

18,

20,

21,

22], and ineffective management of green infrastructure [

23]. In the context of unpredictable climate change and rapid urbanization, population growth and the expansion of urban areas have become key drivers exacerbating flood hazards [

21,

24]. Therefore, urban flooding should be viewed as the cumulative outcome of interactions among climate, geomorphology and uncontrolled human-induced factors [

6,

25,

26].

Southeast Asia, characterized by low-lying terrain and high population density, is particularly vulnerable to flooding. Serious floods in recent decades in Hanoi (2008), Bangkok (2011), Beijing (2012), and Ho Chi Minh City (2018) illustrate the escalating level of risk [

3,

27,

28,

29,

30]. This emphasizes that urban flooding is not only an extreme meteorological phenomenon but also a consequence of unsustainable spatial development and inadequate infrastructure management [

29,

31].

In Vietnam, Hanoi is a typical example of urban flooding. Its low-lying terrain and gentle slope hinder natural drainage, making many areas prone to inundation. Older streets are less affected by flooding, while many new urban areas frequently experience severe flooding, highlighting the imbalance between urban spatial expansion and the capacity of drainage infrastructure [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Since 2012, repeated heavy rainfall events have caused serious floods in rapidly developing districts, resulting in substantial socio-economic damage and directly impacting on people’s lives [

34]. Recent studies have proposed various solutions to control floods, ranging from technical measures to prevention planning based on risk analysis [

34,

35].

Numerous methods have been developed to analyze and predict flooding. Hydrological-hydraulic models such as HEC-RAS, LISFLOOD-FP, MIKE NAM, MIKE 11, Flo-2D, etc., are widely used in flow simulation and flood mapping [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Raster models [

40], GIS-based flood modeling [

41], and uncertainty analysis in flooding mapping [

42] have further improved simulation accuracy and provided more reliable information for management. However, these models require detailed input data, which poses challenges for application in data-scarce urban contexts. Another approach is GIS combined with multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA, AHP) to classify flood risk zones based on elevation, rainfall, land use, and infrastructure factors [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Despite its efficiency, it is still affected by subjectivity in determining weights [

48,

49,

50,

51].

In recent decades, remote sensing technology has played an increasingly important role in monitoring and assessing inundation [

52,

53,

54]. In particular, SAR Sentinel-1 imagery offers the ability to collect data under all weather conditions and penetrate clouds [

55,

56]. Recent studies have integrated Sentinel-1 with deep learning models (CNN–LSTM) and MODIS data to create high-resolution maps to support planning and risk management [

57,

58]. In Vietnam, the use of Sentinel-1 for urban flooding studies remains limited, mainly focusing on large river basins or pilot studies [

2,

59,

60,

61], creating opportunities for applications in large urban areas.

Geomorphology also plays a vital role in flooding analysis. Many domestic studies have shown the relation between terrain features (plains, lowlands, paleochannels) and flooding risk [

6,

26,

32,

62,

63]. Studies in the Red River Delta, Tra Khuc, Hue, and Thu Bon demonstrate that geomorphology affects flood distribution, drainage capacity, and re-flooding [

6,

32,

62,

63,

64]. However, most studies have been limited to theoretical warnings or geomorphological mapping without integrating quantitative analysis with modern remote sensing data such as Sentinel-1.

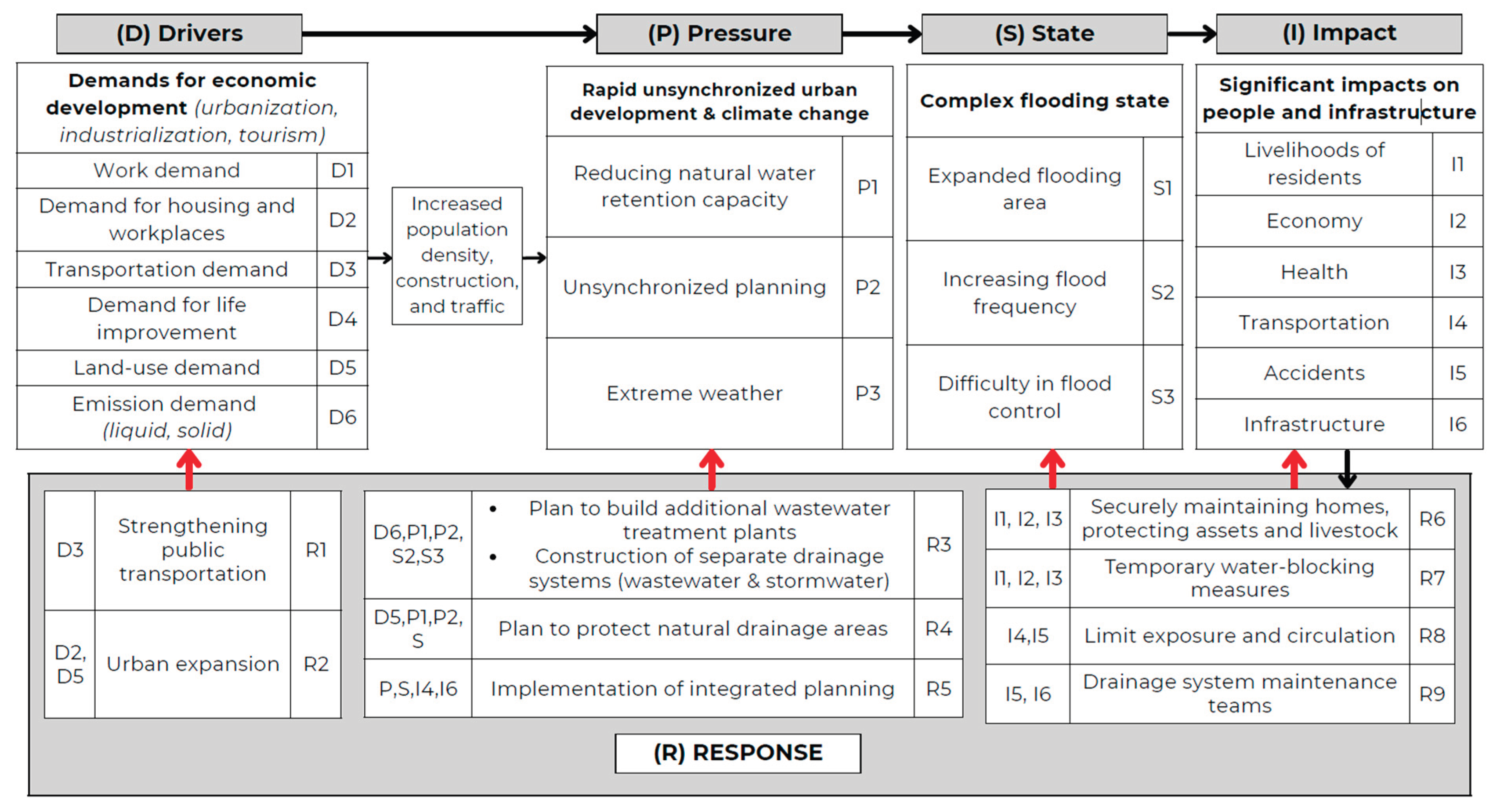

Urban flooding is also associated with institutions and planning [

65,

66]. Planning that does not integrate hydrological factors, climate change, natural drainage mechanisms, or account for increased impervious surfaces and unreasonable ground elevation can overload drainage systems and cause localized flooding. Modern urban planning requires integrating nature-based solutions such as flood corridors, detention basins, and ecological buffers from the master planning stage. From a system analysis perspective, the DPSIR (Drivers–Pressures–State–Impacts–Responses) framework, proposed by the European Environment Agency (EEA) in 1999, provides a systematic approach to analyze cause–effect relationships of environmental issues [

67,

68]. Many international studies have applied DPSIR to analyze flood and inundation, constructing aggregate indices such as the Integrated Flood Risk Index (IFRI) or Coastal Risk Index (CRI) [

68,

69]. In Vietnam, DPSIR has only been applied in the Vu Gia–Thu Bon basin and some cities in the Central region [

70,

71]. These studies have not fully integrated DPSIR with quantitative data such as geomorphology and remote sensing.

The overview shows that each approach has its advantages and disadvantages: Hydraulic models simulate details but require extensive data [

38,

40,

42]; GIS–AHP is flexible but remains subjective [

45,

46,

72]; Sentinel-1 performs well in status monitoring but requires integration with spatial analysis [

58,

59]; DPSIR is systemic but has not yet been deeply integrated with quantitative data [

68,

69,

71]. These gaps highlight the need for an integrated approach combining geomorphology data and remote sensing with DPSIR to fully assess urban flooding risk.

In this context, this study adopts an integrated geomorphology–Sentinel-1–DPSIR approach to assess urban flooding risks in Hanoi. Study objectives include: (i) geomorphological analysis to identify flood-prone areas; (ii) using Sentinel-1 to detect and monitor actual flood areas; and (iii) integrating these findings into the DPSIR framework to analyze the system of drivers–pressures–state–impacts–responses. The study is expected to provide a scientific basis for urban planning and propose solutions for sustainable flood risk management and climate change adaptation.

In parallel, the rapid digital transformation of urban governance in Hanoi highlights the necessity of integrating flood risk information into smart management systems. Combining geospatial analysis and inundation mapping with digital decision-support tools can strengthen data sharing, transparency, and coordination among sectors. This approach ensures that scientific assessments are not isolated from practice but become part of a broader framework for adaptive and resilient urban management.

2. Study Area

Hanoi city is geographically located between 20

53' and 21

23' North latitude and 105

' to 106

' East longitude, situated in the center of the Red River Delta. It is the capital and one of the major political, administrative, economic, and cultural centers of Vietnam. Hanoi has a high level of urbanization and population density, covering an area of 3,359.84 km² with a population of over 8.5 million [

73,

74]. As one of the two main economic growth poles of Vietnam, the city experiences increasing pressure on its infrastructure and urban environment [

74,

75] (

Figure 1).

Hanoi's topography is relatively low and flat, characterized by a dense river network and a tropical monsoon climate. Rainfall is concentrated mainly in the wet season, accounting for about 89% of the annual total, making the city highly prone to flooding, especially in low-lying central districts during heavy rain events [

74,

75] (

Figure 2).

Hanoi's terrain is also profoundly shaped by its river system. Rivers such as the Day, Nhue, To Lich, and Ca Lo once had strong natural flows but, through geological and hydrological evolution, have left behind traces in the form of paleochannels, residual lakes, and interlaced ridges of varying elevation. Large water bodies such as West Lake, Yen So Lagoon, and a chain of smaller lakes along riverbanks are remnants of these processes, forming the city’s distinctive “mound–depression” landscape pattern [

76].

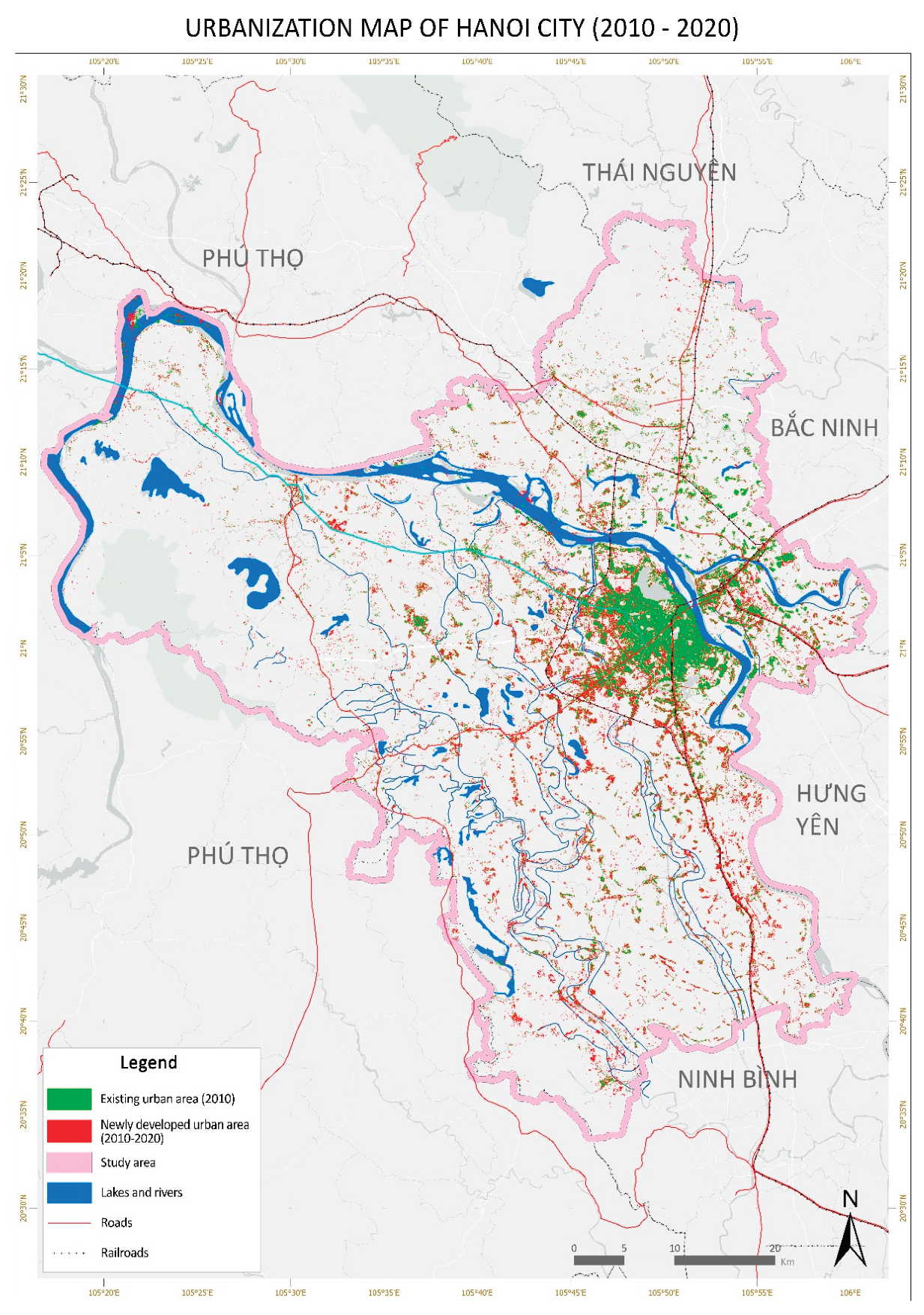

Over the past decade, Hanoi has experienced rapid urbanization, with an urbanization rate reaching 49.1%—5.4% higher than the national average in 2024. Urban expansion has occurred primarily toward the southern and southwestern peripheries, accompanied by increases in both building density and height. However, this expansion has not been synchronized with infrastructure development, posing major challenges for sustainable urban management and planning (

Figure 3).

Hanoi has a comprehensive system of rivers, lakes, and dikes designed for flood control, but recent inundations are mainly caused by localized heavy rainfall that exceeds the drainage capacity. The existing drainage infrastructure is insufficient to meet the growing demands under rapid urbanization and population increase. In recent years, intense rainfall events have repeatedly caused serious flooding in many inner-city districts, resulting in considerable damage to assets and public infrastructure.

The scope of this study focuses on 12 inner-city districts and 4 suburban districts (Dan Phuong, Hoai Duc, Gia Lam, and Thanh Tri) (

Figure 1), representing areas experiencing intensive urbanization and extensive land-use conversion from agricultural to non-agricultural purposes. These areas have also recorded numerous severe flooding locations between 2010 and 2024. Furthermore, they face critical planning challenges, particularly regarding drainage systems, land-use management, and urban development control under conditions of climate change and rapid population growth.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

The study integrates multi-source datasets including remote sensing data, topographic and geomorphological maps, statistics data, and field surveys to assess the current status and flooding risk in Hanoi (Table ). Data were selected according to three criteria: (i) reliability of the sources; (ii) spatial and temporal resolution suitable for GIS analysis; and (iii) direct relevance to each component of the DPSIR (Drivers–Pressures–State–Impacts–Responses) framework. All spatial data were standardized to the WGS84/UTM Zone 48N coordinate system. Preprocessing steps included speckle filtering of SAR image, DEM correction, and synchronization of the LULC layer to ensure consistency prior to overlay analysis.

Table 1.

Data sources for the study.

Table 1.

Data sources for the study.

| Types of data |

Formats |

Duration |

Source / references |

Purposes of use |

| Sentinel-1 SAR (C-band, IW) |

Raster (10m) |

2015–2024 (Jul–Oct) |

ESA/Copernicus Hub |

Flood mapping, constructing maps of flood frequency |

| ALOS AVNIR-2 |

Raster (30 m) |

2010, 2020 |

JAXA |

Analysis of urban fluctuation |

| VLULC Vietnam Land Use Land Cover |

Vector/Raster |

2010–2020 |

Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, VLULC update |

Map of land use, urban expansion |

| DEM (SRTM v3) |

Raster (30 m) |

2011 |

USGS |

Topographic analysis, geomorphological indices |

| Geomorphological map of Hanoi |

Vector (1:320,000) |

2015 |

Dao Dinh Bac |

Classification of 9 geomorphological units |

| Historical flooded points |

Vector (GPS points) |

2012-2022 |

Reports of authority, press, field surveys |

Flood map validation |

| Population (Statistical yearbook) |

Data tables |

2013-2021 |

Hanoi Statistics Office |

Assessment of “Drivers” in DPSIR (non-GIS) |

| Drainage systems |

Documents |

2018-2022 |

Hanoi Sewerage and Drainage Company Limited |

Assessment of “Pressures” in DPSIR (non-GIS) |

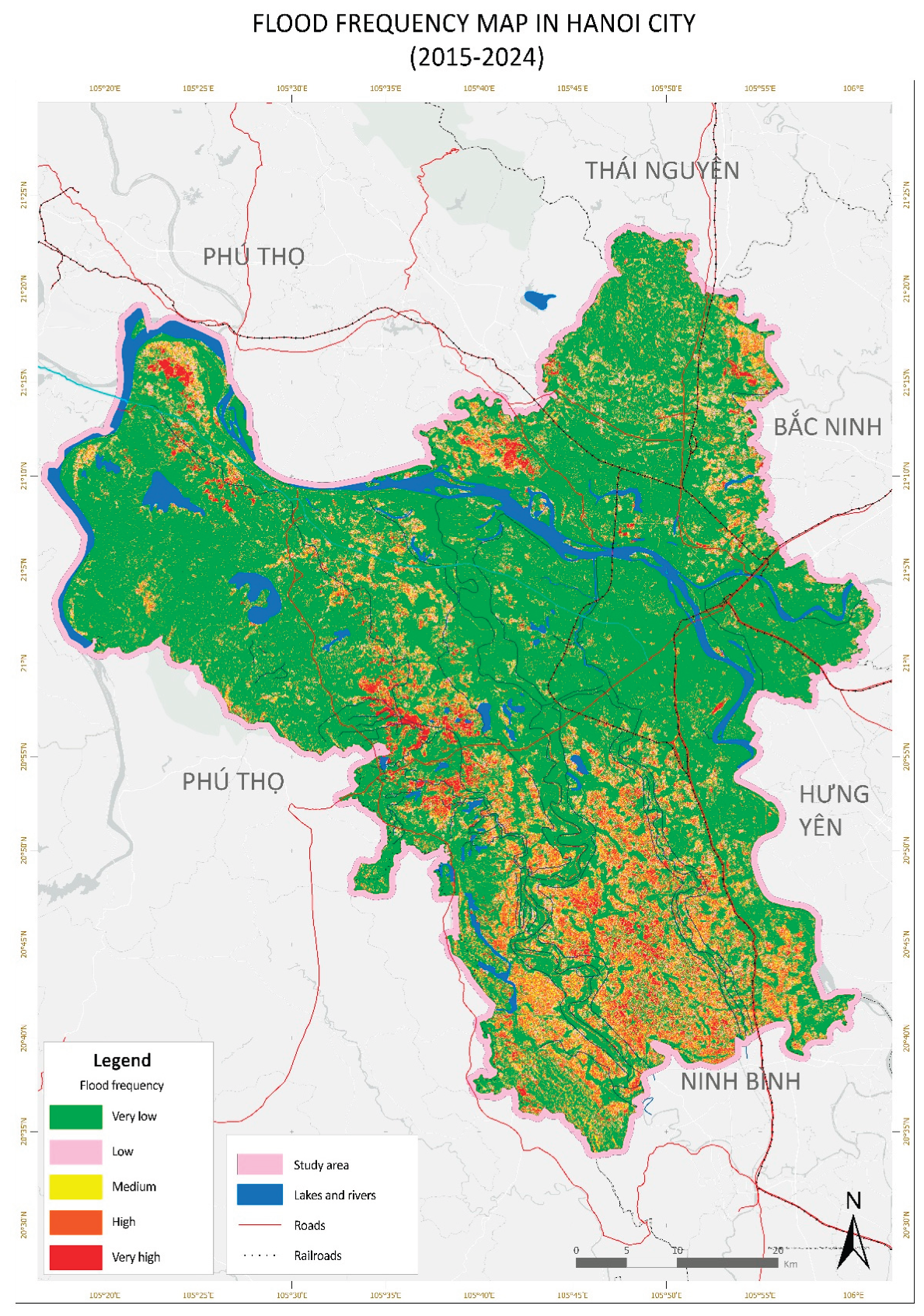

3.2. Constructing Flood Maps from Sentinel-1 SAR

Sentinel-1 (A & B) operates in the C-band with a 6–12-day revisit cycle, which is highly suitable for flood monitoring as it is unaffected by cloud cover or weather conditions. Sentinel-1 SAR images (VV and VH polarizations, C-band) from 2015 to 2024 (rainy season, July–October) were processed on Google Earth Engine (GEE) following these steps:

Preprocessing: Orbit and terrain correction, radiometric calibration, and speckle filtering using the Refined Lee filter (5×5 kernel).

Flood classification: Calculation of the SAR-based NDWI index, application of Otsu’s automatic thresholding method to classify water and non-water pixels, and generation of binary flood maps for each image.

Flood frequency mapping: Compilation of the image series to count the number of times each pixel was classified as inundated during 2015–2024. Flood frequency was then categorized into five levels (very low, low, medium, high, very high) according to pixel occurrence.

Validation: Using 148 historical flood points (2012–2024) collected from official reports, media sources, and GPS surveys for spatial–temporal matching. The validation focused on flood occurrence and distribution rather than flood depth or duration, due to the limited resolution of reference data.

The overall accuracy reached 87% (Kappa = 0.79), consistent with international studies [

77,

78]. The GIS–remote sensing framework developed in this study not only supports quantitative flood risk assessment but also provides a standardized spatial database that can be incorporated into digital management systems. This interoperability enables continuous data updating, integration with monitoring networks, and long-term application in e-government platforms for flood control and urban planning.

3.3. Analysis of Urbanization and Land Use

ALOS AVNIR-2 images (2010 and 2020), combined with VLULC datasets (2010–2020), were used to detect changes in land cover and identify newly urbanized areas compared with pre-existing urban zones.

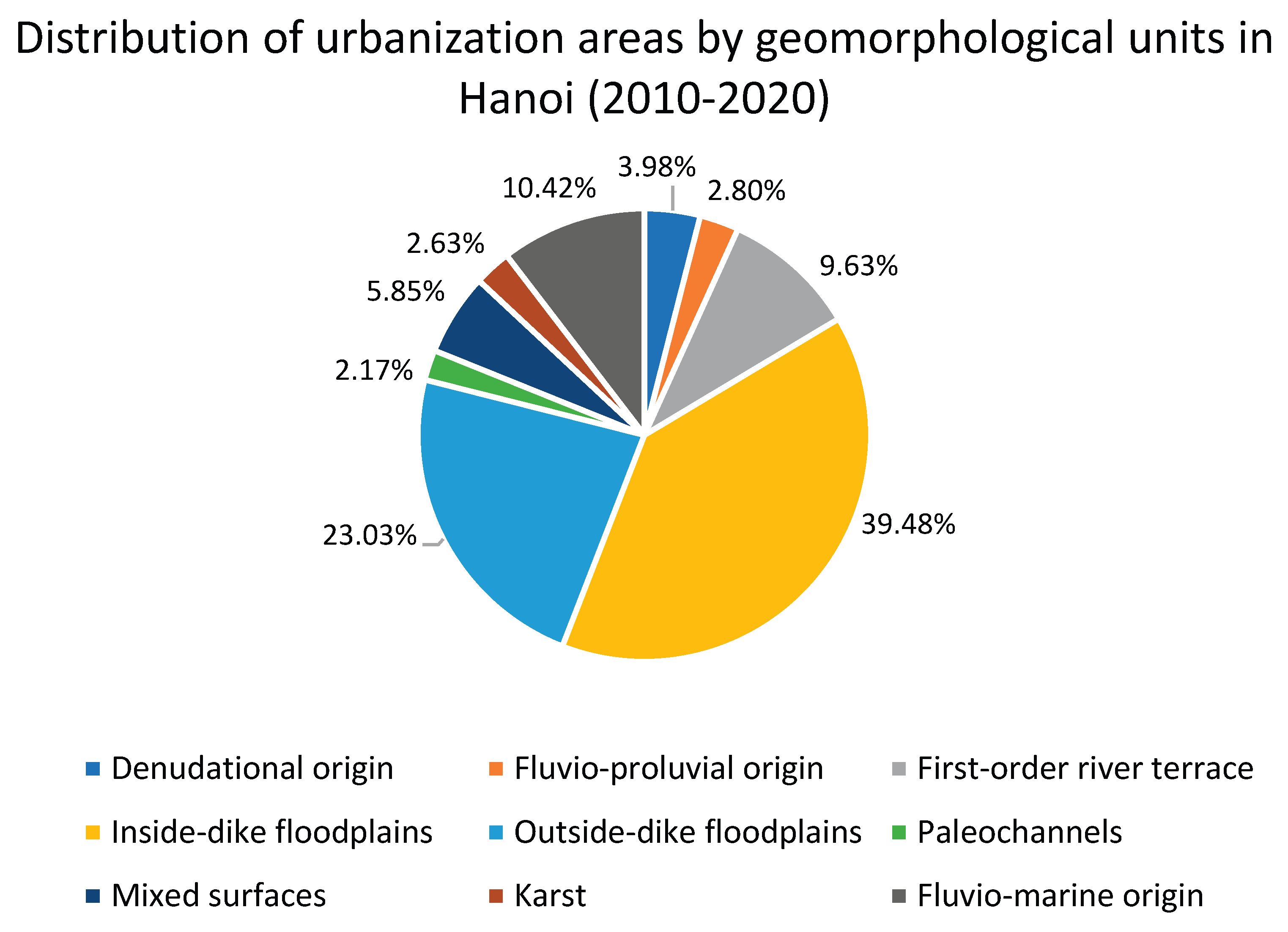

Old urban areas were defined as those urbanized prior to 2010, while new urban areas refer to regions developed after 2010. Urbanization layers were overlaid with the geomorphological map to determine which geomorphological units were most affected by new urban expansion, particularly those in low-lying terrains (inner and outer-dike floodplains and fluvio-marine plains).

Previous studies have consistently shown that urban expansion in low-elevation zones increases flood susceptibility [

79].

3.4. Flood Risk Assessment by Geomorphology

The geomorphological map of Hanoi (scale 1:320,000) delineates nine geomorphological units, including inner and outer-dike floodplains, paleochannels, karst areas, fluvio-marine plains, denudation surfaces, fluvial surfaces, mixed surfaces, and river terraces.

The flood frequency map (

Section 3.2) and urbanization layer (

Section 3.3) were overlaid with this geomorphological map to identify terrain units most vulnerable to inundation.

A Weighted Overlay Analysis was performed in GIS, assigning each geomorphological unit a weight from 0 (very low) to 5 (very high) based on its susceptibility to flooding. Weighting values were derived from a synthesis of international studies [

80] and adjusted to reflect Hanoi’s specific topographic features, including elevation, slope, and natural drainage capacity.

3.5. DPSIR Framework

The Drivers–Pressures–State–Impacts–Responses (DPSIR) framework was applied to systematically examine the cause–effect relationships among factors influencing flooding in Hanoi (

Figure 4).

Drivers: Population growth, rapid urbanization, and climate change.

Pressures: Increasing impervious surfaces, infilling of lakes and ponds, and reduced drainage capacity.

State: Current flood frequency and urbanization maps, combined with geomorphological conditions.

Impacts: Results from field and sociological surveys assessing effects on livelihoods, infrastructure, and the economy.

Responses: Policies, planning solutions, and infrastructure projects that have been implemented or are under development.

The DPSIR framework has been widely and successfully applied in environmental and risk management research both in Vietnam and internationally [

81]. Its use in this study enables a comprehensive analysis of the root causes and evolution of flooding, and supports the formulation of adaptive and sustainable planning strategies.

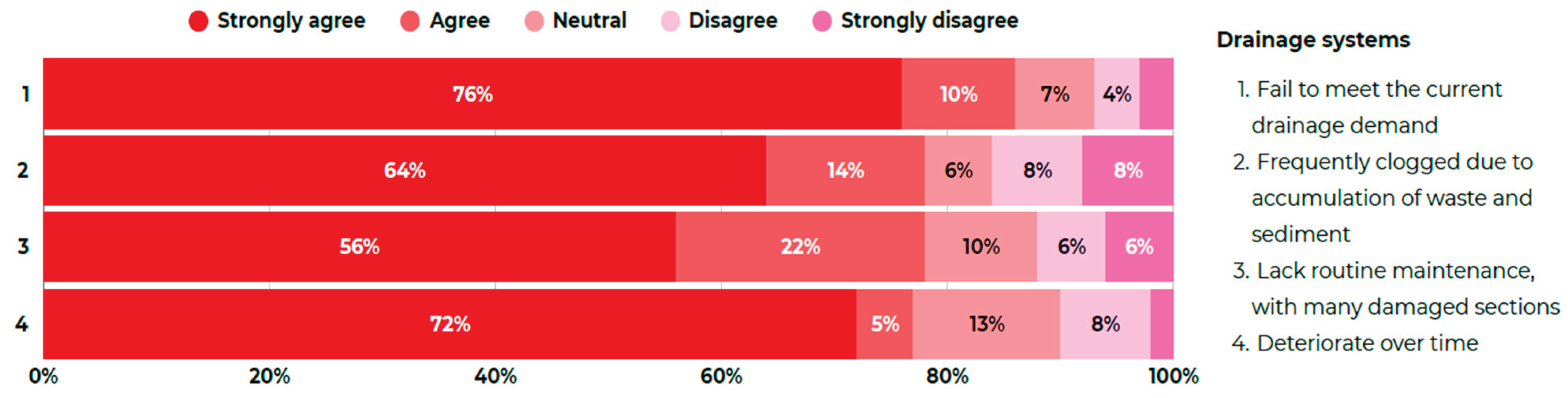

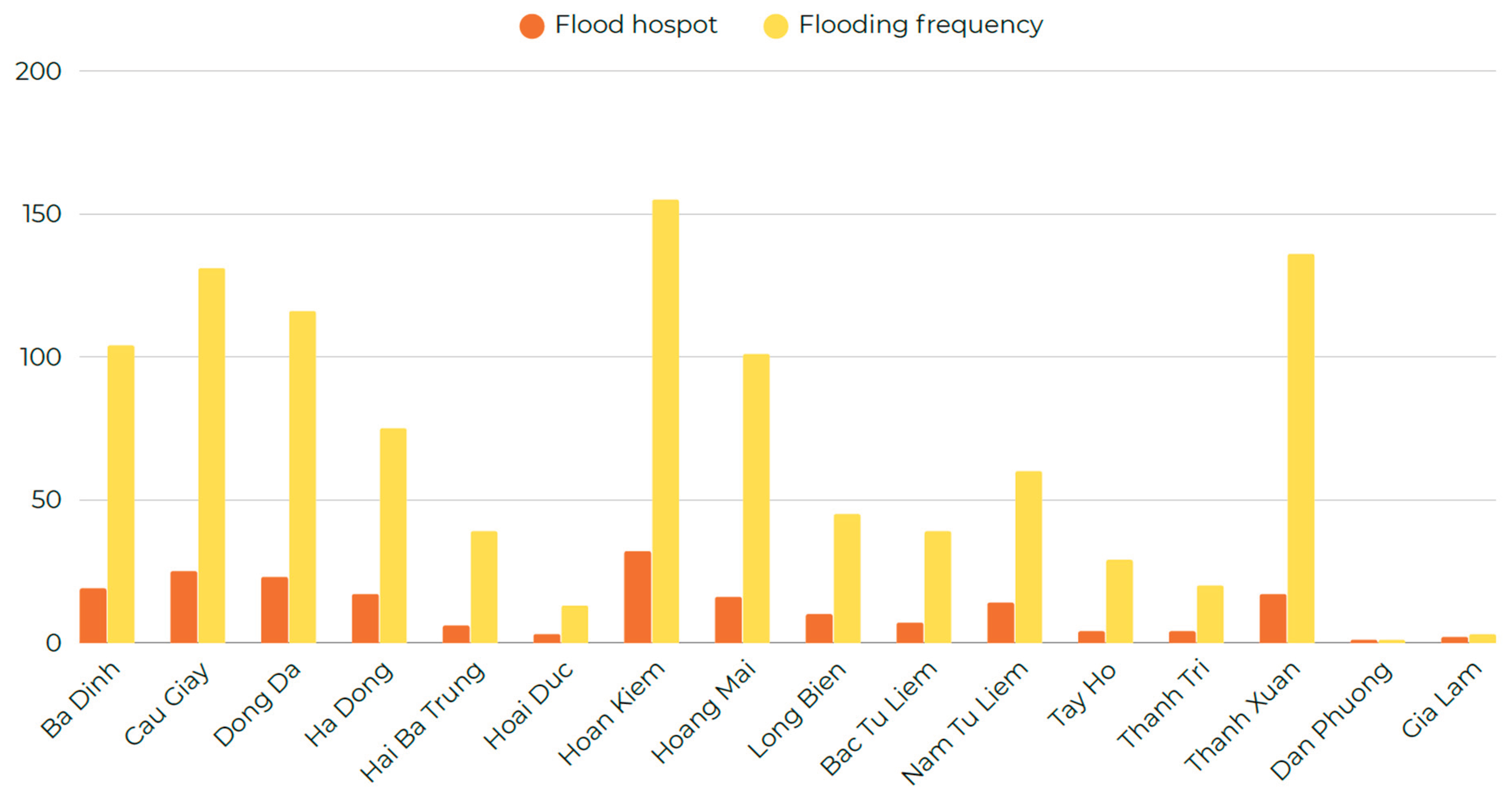

3.6. Field Surveys and Sociological Investigations

Field surveys were conducted from 22 to 30 March 2025 in four districts with high flood frequency (Thanh Xuan, Hoang Mai, Nam Tu Liem, and Hoai Duc). The surveys documented flooded sites, drainage infrastructure, photographic evidence, and GPS coordinates.

For sociological investigations, 80 structured questionnaires were distributed to households and individuals in flood-affected areas. The questionnaires covered flood frequency and duration, damages, drainage performance, and expectations for future planning solutions. These data were used to validate Sentinel-1 flood maps (State) and to assess Impacts and Responses within the DPSIR framework.

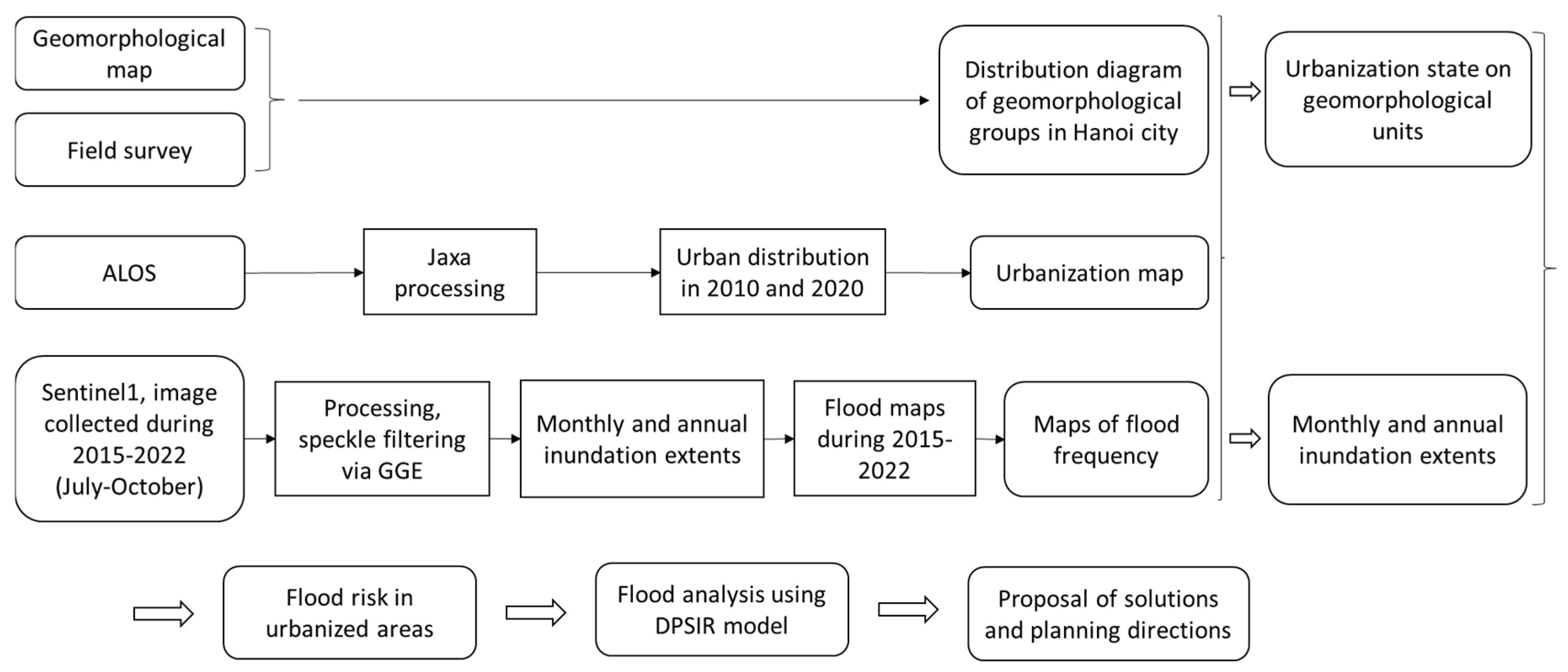

3.7. Study Process

The overall study process comprised four main stages (

Figure 5):

Data collection and preprocessing: Compilation and preparation of Sentinel-1, ALOS, VLULC, DEM, geomorphological, flood point, population, and drainage datasets.

Geomorphological and urbanization analysis: Generation of old and new urban maps and analysis by geomorphological unit.

Flood mapping and frequency analysis: SAR image processing, flood frequency calculation, and validation using historical flood points.

Risk assessment and adaptive planning proposals: Integration of Weighted Overlay results with the DPSIR framework and social survey data to identify high-risk zones and propose adaptation-oriented solutions.

5. Conclusions

Urban flooding has become a major challenge to sustainable development in Hanoi, as its frequency, extent, and severity continue to increase. This study applied an integrated approach combining geomorphological analysis, Sentinel-1 remote sensing data, and the DPSIR framework to assess the relationship between urbanization and flood risk.

The results show that more than 70% of inundated areas are located in low-lying geomorphological units such as floodplains, paleochannels, and fluvio-marine terrains. Notably, approximately 80% of newly urbanized areas have been developed in sensitive zones, of which 36.5% are situated on inner-dike floodplains. The flood map validated using 148 field points achieved an overall accuracy of 87% (Kappa = 0.79), confirming the effectiveness of radar data in spatio-temporal monitoring of urban flooding.

The DPSIR analysis identified three major groups of pressures: the reduction of natural water retention spaces, unsynchronized infrastructure planning and management, and the increase in extreme rainfall events caused by climate change. Among these, uncontrolled urbanization and weak planning enforcement were recognized as root causes, leading to recurrent and expanding flood incidents.

This study provides scientific evidence of the combined impacts of urbanization on flooding and proposes adaptive planning orientations for Hanoi, including the preservation of water retention spaces, development of green–gray infrastructure, and upgrading of the drainage system. However, the scope of this study was limited to Hanoi during 2015–2024 and did not consider extreme climate scenarios. Future research should expand the study area, employ high-resolution remote sensing data, integrate urban hydrological models, and apply artificial intelligence techniques to enhance reliability and support the development of a solid scientific foundation for sustainable urban planning in Vietnam. The findings of this study also demonstrate the potential of integrating geomorphological and remote-sensing data into digital management frameworks. Future work should focus on developing interoperable geospatial infrastructures and applying artificial intelligence for dynamic flood prediction and urban monitoring. Embedding these analytical frameworks into smart-city and e-government systems will enhance resilience, transparency, and the overall efficiency of urban governance in Vietnam.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Trinh Thi Kieu Trang and Dang Kinh Bac; methodology, Trinh Thi Kieu Trang; software, Nguyen Minh Hieu; validation, Trinh Thi Kieu Trang, Dang Kinh Bac, and Pham Thi Phuong Nga; formal analysis, Vu Thi Kieu Oanh and Nguyen Minh Hieu; investigation, Vu Thi Kieu Oanh, Pham Thi Phuong Nga, Tran Van Tuan, Pham Thi Phin, Pham Sy Liem, Do Thi Tai Thu, and Vu Khac Hung; resources, Dang Kinh Bac and Pham Thi Phuong Nga; data curation, Nguyen Minh Hieu; writing—original draft preparation, Trinh Thi Kieu Trang; writing—review and editing, Trinh Thi Kieu Trang and Dang Kinh Bac; visualization, Nguyen Minh Hieu; supervision, Trinh Thi Kieu Trang and Dang Kinh Bac; project administration, Trinh Thi Kieu Trang; funding acquisition, Trinh Thi Kieu Trang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.