Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- Technical and integration challenges: Intermittent solar and wind power generation make it difficult to balance supply and demand. Furthermore, the electricity infrastructure, designed for fossil-fuel-powered generation plants, requires modernization to integrate renewable energy and storage [17,18]. There are also limitations in the capacity and availability of current storage technologies [19].

- -

- -

- Regulatory and political challenges: Regulatory fragmentation and complex permitting processes slow project implementation [22,23]. The lack of continuity and stability in political incentives reduces investor confidence [24]. There are also legal loopholes that limit the development of energy communities and local participation [25].

- -

2. Materials and Methods

Expert Method

Questionnaire Development

Application Procedure

- 0.8 <= K <= 1.0, high expert competence coefficient

- 0.5 <= K < 0.8, medium expert competence coefficient

- K < 0.5, low expert competence coefficient

Calculation of the Argumentation Quotient (Ka)

Calculation of the Knowledge Quotient (Kc)

| Expert | Organization | Kc | Ka | K | Level of competence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | UNDP | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.95 | Alto |

| 2 | MINEM | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.95 | Alto |

| 3 | UNE | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.95 | Alto |

| 4 | IHES | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.95 | Alto |

| 5 | MINCEX | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.95 | Alto |

| 6 | FFRC | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.90 | Alto |

| 7 | UNE | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.90 | Alto |

| 8 | UNIDO | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.90 | Alto |

| 9 | CEDEL | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.85 | Alto |

| 10 | UNE | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.85 | Alto |

| 11 | INRH | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.80 | Alto |

| 12 | UNISS | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.90 | Alto |

3. Results

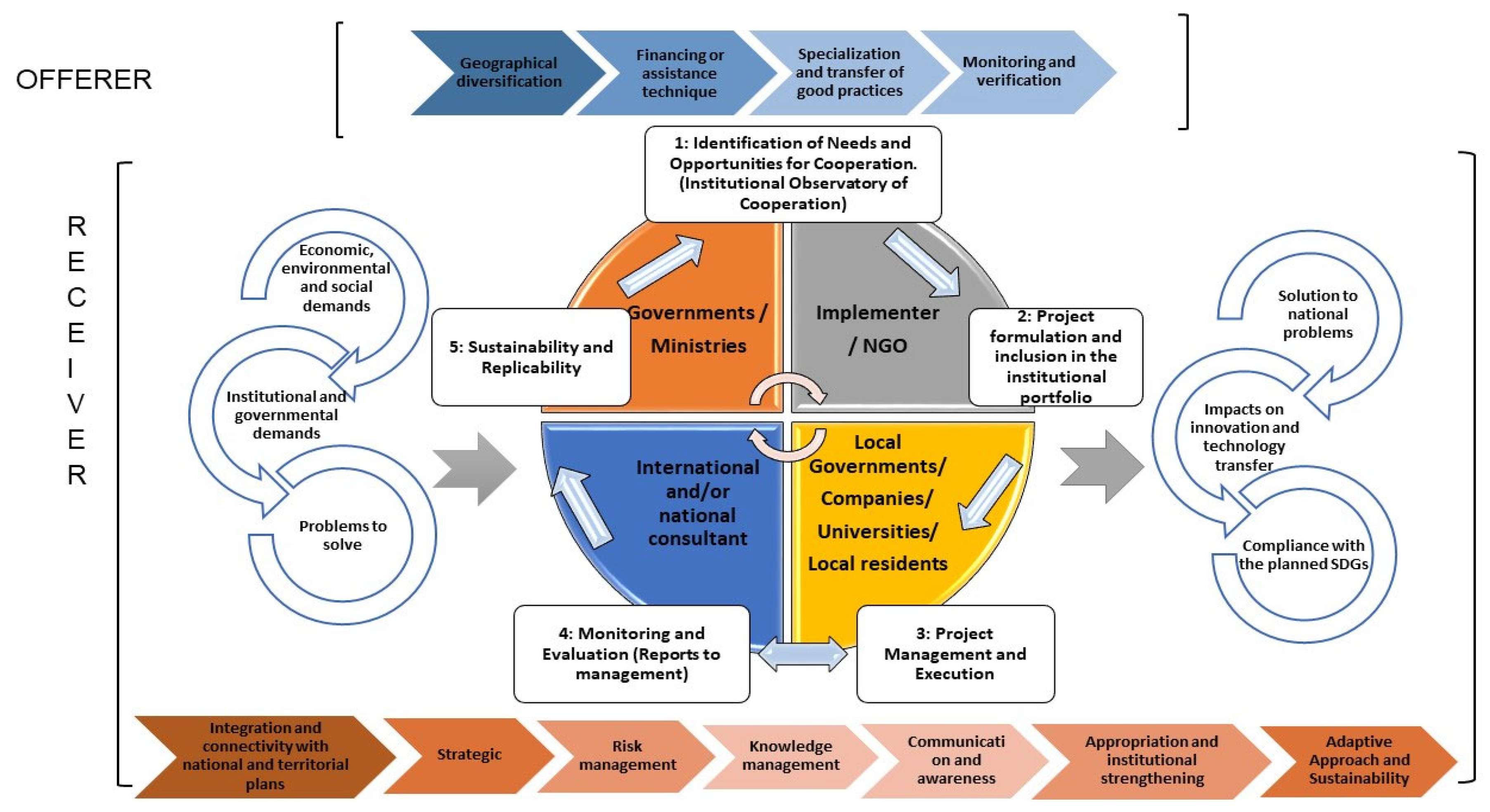

3.1. Brief Explanation of the Model

3.2. Scope of the Model

3.2.1. Subprocess 1: Identification of Cooperation Needs and Opportunities

- To conduct technological and financial gap analyses in the energy matrix.

- To identify relevant international cooperation programs and agencies.

- To analyse the geopolitical context to assess risks and opportunities.

- To develop a priority plan aligned with the identified needs and opportunities.

- To align cooperation opportunities with the priority plan.

3.2.2. Subprocess 2: Formulation of the Cooperation Project Portfolio

- To design a portfolio of projects that respond to the identified needs and are aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

- To negotiate with international partners and stakeholders to define roles and commitments.

- To design financing schemes that minimize geopolitical risks.

- To prepare the technical and administrative documents required for approval.

- Submit projects for approval at the appropriate levels.

3.2.3. Subprocess 3: Project Management and Execution

- To implement planned activities in coordination with international partners.

- To conduct technical and financial monitoring for risk management.

- To train local personnel to ensure knowledge transfer.

- To influence energy policies at the local, sectorial, provincial, and national levels to promote the adoption of renewable technologies.

3.2.4. Subprocess 4: Monitoring and Evaluation

- To design and implement a continuous monitoring system.

- To prepare periodic reports on technical, financial, and impact progress.

- To evaluate technical and social environmental impacts, as well as medium- and long-term indicators.

- To identify and document lessons learned to improve future projects.

3.2.5. Subprocess 5: Sustainability and Replicability

- To manage the technology and knowledge generated to ensure its continuity.

- To design or integrate sustainable financing mechanisms and incentives.

- To document good practices and successful experiences.

- To develop an exit strategy that allows for replication and improvement of the project in other areas.

- To record all relevant information in the organization’s digital and technological database.

- Geographic diversification of interventions (expanding and balancing alliances, projects, or exchanges between geographic regions and countries).

- Financing mechanisms or technical assistance capabilities.

- Specialization and transfer of good practices.

- Monitoring and evaluation.

- Integration and connectivity with national and regional development plans.

- Strategic alliances with institutions or universities.

- Management of risks associated with projects.

- Knowledge management based on lessons learned and products generated by projects.

- Communication and awareness-raising with key stakeholders.

- Appropriation of technology and knowledge that enable institutional strengthening.

- Sustainability, through institutional financial and supporting mechanisms from the energy sector.

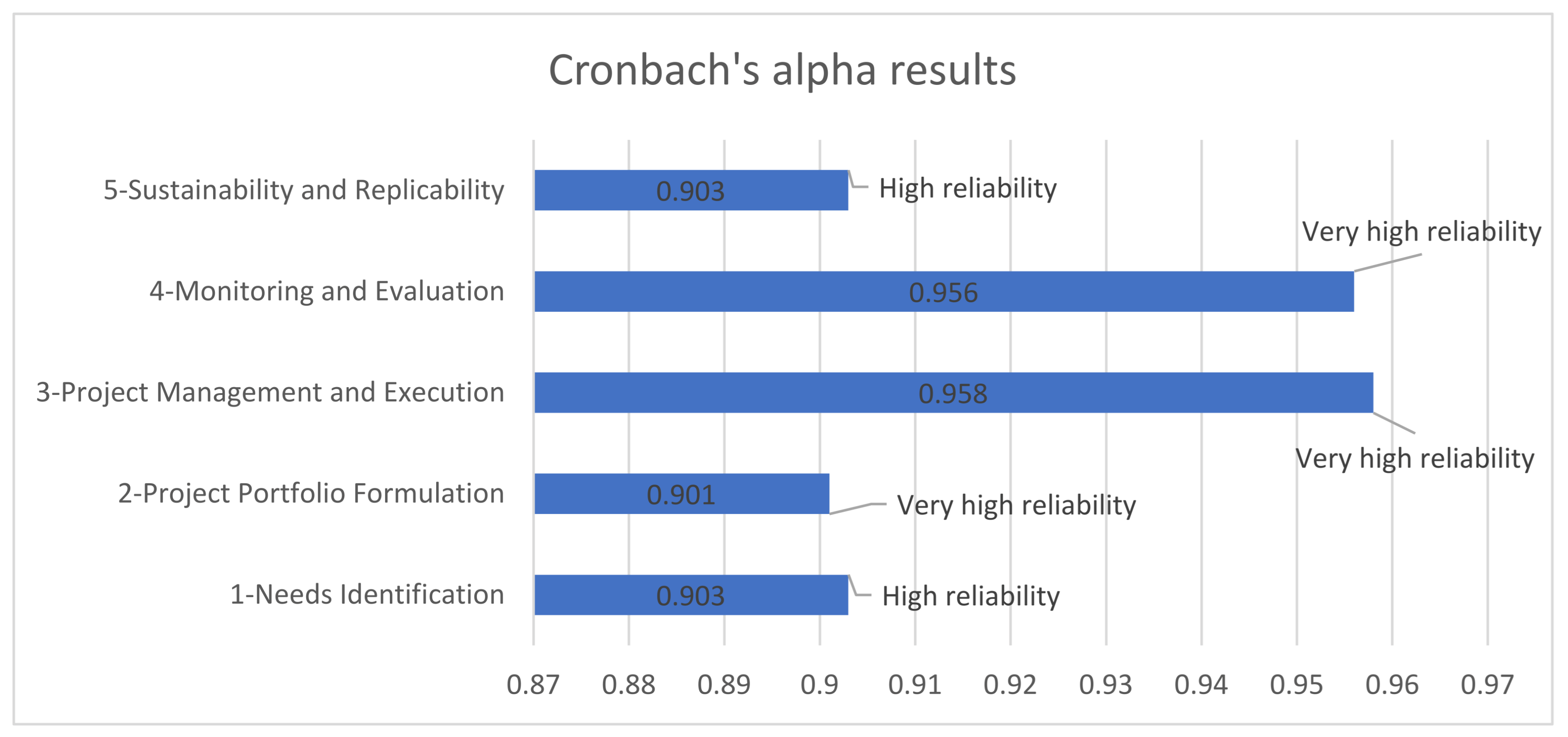

3.3. Results: Reliability Analysis (SPSS V.20)

- Very low reliability: α ≤ 0.30

- Low reliability: 0.30 < α ≤ 0.60

- Moderate reliability: 0.60 < α ≤ 0.75

- High reliability: 0.75 < α ≤ 0.90

- Very high reliability: α > 0.90.

3.3.1. Subprocess 1

- Internal consistency: The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient obtained was 0.903, and the alpha based on typed items was 0.913; both values indicate high and adequate reliability for the scale. These results suggest that the items present adequate homogeneity and consistently measure the underlying construct of Subprocess 1.

- Item descriptive statistics: Item means range from 2.75 to 3.92, with an overall mean of 3.42, indicating a medium-high level of response. Standard deviations range from 0.29 to 1.42, showing moderate response variability.

- Inter-item correlations: Most inter-item correlations are positive and moderate to high, with some items showing low or negative correlations with others, which may indicate items with less contribution to internal consistency. Items such as ACT_1.2 and ACT_3.3 show low or negative correlations with certain items, suggesting the need for revision. The corrected item-total correlation ranges from -0.023 (ACT_3.3) to 0.775 (ACT_2.2).

- Cronbach’s alpha if the item is deleted: The elimination of items with low correlation, such as ACT_3.3, does not substantially improve the overall Cronbach’s alpha, which remains above 0.90. This indicates that, overall, the items contribute positively to the instrument’s internal reliability as shown in Table 1.

| Items | Scale mean if item is deleted | Scale variance if item isdeleted | Corrected item-total correlation | Cronbach’s alpha if the item is deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT_1.1 | 72.2500 | 93.295 | .602 | .897 |

| ACT_1.2 | 72.1667 | 99.424 | .050 | .913 |

| ACT_1.3 | 72.3333 | 88.061 | .492 | .902 |

| ACT_1.4 | 71.8333 | 93.788 | .557 | .898 |

| ACT_2.1 | 72.0833 | 91.720 | .545 | .898 |

| ACT_2.2 | 72.0000 | 86.364 | .775 | .891 |

| ACT_2.3 | 71.6667 | 90.242 | .721 | .893 |

| ACT_3.1 | 72.5833 | 86.447 | .493 | .904 |

| ACT_3.2 | 71.5000 | 97.000 | .569 | .899 |

| ACT_3.3 | 71.5000 | 101.545 | -.023 | .906 |

| ACT_4.1 | 71.5833 | 95.356 | .674 | .897 |

| ACT_4.2 | 72.0000 | 90.545 | .851 | .892 |

| ACT_4.3 | 71.5833 | 92.265 | .742 | .894 |

| ACT_5.1 | 72.1667 | 90.879 | .624 | .896 |

| ACT_5.2 | 71.7500 | 88.023 | .751 | .892 |

| ACT_5.3 | 71.4167 | 100.629 | .139 | .904 |

| ACT_5.4 | 72.0000 | 93.091 | .520 | .898 |

| ACT_6.1 | 71.7500 | 92.750 | .646 | .896 |

| ACT_6.2 | 71.9167 | 94.447 | .510 | .899 |

| ACT_7.1 | 71.7500 | 95.477 | .428 | .900 |

| ACT_7.2 | 71.9167 | 91.174 | .775 | .893 |

| ACT_7.3 | 72.2500 | 91.841 | .514 | .899 |

3.3.2. Subprocess 2

- Internal consistency: The overall Cronbach’s alpha was 0.901, indicating a high level of reliability and internal consistency for the scale, suggesting that the items consistently measure the proposed construct. Upon standardization, the alpha increased slightly to 0.916.

- Item descriptive statistics: Item means ranged from 2.6667 to 3.6667, with generally moderate standard deviations, reflecting some variability in responses. Most items showed moderate to high, positive corrected item-total correlations (with values between 0.258 and 0.864), indicating that each item contributes adequately to the scale.

- Inter-item correlations: However, some items, such as ACT_3.3 (-0.026) and ACT_7.1 (-0.072), exhibited negative correlations with the total scale, suggesting that they may be measuring different constructs or require revision or elimination to improve reliability.

- Cronbach’s alpha if the item is deleted: The elimination of ACT_1.2 was necessary due to its zero variance, an indicator of lack of response variability that could affect reliability. Furthermore, the uniqueness of the covariance matrix may result from strong linear relationships between items.

| Items | Scale mean if item is deleted |

Scale variance if item is deleted | Corrected item-total correlation | Cronbach’s alpha if item is deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT_1.1 | 64.2500 | 100.568 | .495 | .898 |

| ACT_1.3 | 64.0833 | 95.538 | .790 | .891 |

| ACT_1.4 | 64.5833 | 98.992 | .583 | .896 |

| ACT_2.1 | 64.5000 | 96.455 | .608 | .895 |

| ACT_2.2 | 65.0833 | 94.083 | .405 | .903 |

| ACT_2.3 | 64.5833 | 91.720 | .851 | .888 |

| ACT_3.1 | 64.4167 | 93.720 | .776 | .890 |

| ACT_3.2 | 64.4167 | 98.083 | .583 | .896 |

| ACT_3.3 | 65.0833 | 105.174 | -.026 | .917 |

| ACT_4.1 | 64.4167 | 90.629 | .864 | .887 |

| ACT_4.2 | 64.8333 | 91.242 | .812 | .888 |

| ACT_4.3 | 64.8333 | 91.606 | .638 | .893 |

| ACT_5.1 | 64.1667 | 97.424 | .618 | .895 |

| ACT_5.2 | 64.3333 | 92.242 | .750 | .890 |

| ACT_5.3 | 64.1667 | 94.879 | .821 | .891 |

| ACT_5.4 | 64.1667 | 98.152 | .560 | .896 |

| ACT_6.1 | 64.5000 | 97.364 | .463 | .898 |

| ACT_6.2 | 64.5833 | 100.992 | .258 | .903 |

| ACT_7.1 | 64.2500 | 106.568 | -.072 | .910 |

| ACT_7.2 | 64.8333 | 99.970 | .342 | .901 |

| ACT_7.3 | 64.9167 | 94.083 | .608 | .894 |

3.3.3. Subprocess 3

- Internal consistency: The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient obtained was 0.958, indicating an excellent level of reliability according to conventional criteria (values greater than 0.90 are considered indicative of high internal consistency). This result suggests that the items are highly correlated with each other and consistently measure the underlying construct.

- Item descriptive statistics: Item means range from 2.58 to 3.58, with an overall mean of 3.18.

- Standard deviations range from 0.51 to 1.87, showing variability in responses. The average item variance is 1.036, indicates a moderate dispersion.

- Inter-item correlations: Most inter-item correlations are positive and moderate to high, with maximum values close to 0.95. Some low or negative correlations were identified (for example, ACT_2.3 presents a very low correlation with several items), which could indicate items that do not optimally contribute to the scale’s homogeneity.

- Cronbach’s alpha if the item is deleted: The elimination of no items significantly improves the overall Cronbach’s alpha, as values range between 0.953 and 0.961. This indicates that all items contribute positively to the instrument’s internal consistency.

| Items | Scale mean if item is deleted |

Scale variance if item is deleted | Corrected item-total correlation | Cronbach’s alpha if item is deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT_1.1 | 67.4167 | 250.447 | .467 | .959 |

| ACT_1.2 | 67.2500 | 249.114 | .577 | .958 |

| ACT_1.3 | 67.2500 | 242.568 | .803 | .955 |

| ACT_1.4 | 66.6667 | 242.242 | .797 | .955 |

| ACT_2.1 | 66.5833 | 239.902 | .867 | .955 |

| ACT_2.2 | 66.7500 | 234.750 | .906 | .954 |

| ACT_2.3 | 66.5833 | 262.265 | .185 | .961 |

| ACT_3.1 | 67.0000 | 236.000 | .720 | .957 |

| ACT_3.2 | 66.5833 | 242.083 | .883 | .955 |

| ACT_3.3 | 66.6667 | 247.697 | .419 | .961 |

| ACT_4.1 | 66.5000 | 238.818 | .900 | .954 |

| ACT_4.2 | 67.0000 | 228.909 | .958 | .953 |

| ACT_4.3 | 67.0833 | 231.356 | .921 | .954 |

| ACT_5.1 | 67.0000 | 251.273 | .578 | .958 |

| ACT_5.2 | 67.1667 | 233.424 | .899 | .954 |

| ACT_5.3 | 66.8333 | 244.333 | .765 | .956 |

| ACT_5.4 | 67.0833 | 239.720 | .737 | .956 |

| ACT_6.1 | 66.5833 | 238.083 | .929 | .954 |

| ACT_6.2 | 66.4167 | 245.174 | .768 | .956 |

| ACT_7.1 | 66.5000 | 260.091 | .326 | .960 |

| ACT_7.2 | 66.5833 | 258.447 | .539 | .958 |

| ACT_7.3 | 66.5000 | 258.818 | .509 | .959 |

3.3.4. Subprocess 4

- Internal Consistency: The overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.956, indicating an excellent level of reliability. This value reflects that the items exhibit high internal correlation and consistently measure the underlying construct of Subprocess 4.

- Item Descriptive Statistics: Item means range from 2.17 (minimum) to 3.75 (maximum), with an overall mean of 2.77. The standard deviation ranges from 0.45 to 1.24, showing moderate variability in responses. The average item variance is 0.864, indicating moderate dispersion.

- Inter-Item Correlations: Most inter-item correlations are positive and moderate to high, with maximum values close to 0.93, supporting internal consistency. Some items show low or negative correlations with certain other items (e.g., ACT_2.3 with a very low correlation), which could indicate items that contribute less to the scale’s homogeneity. The corrected item-total correlation ranges from 0.215 (ACT_2.3) to 0.922 (ACT_5.2), demonstrating that most items contribute significantly to the scale.

- Cronbach’s alpha if the item is deleted: Cronbach’s alpha for item deletion ranges from 0.951 to 0.958, with no item deletion substantially improving overall reliability. This indicates that all items contribute positively to internal consistency. Item ACT_2.3 has the lowest correlation (0.215), suggesting it could be a candidate for revision or possible exclusion.

| Items | Scale mean if item is deleted |

Scale variance if item is deleted | Corrected item total correlation | Cronbach’s alpha if item is deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT_1.1 | 58.4167 | 202.447 | .371 | .959 |

| ACT_1.2 | 58.0833 | 194.083 | .820 | .952 |

| ACT_1.3 | 58.4167 | 190.447 | .851 | .952 |

| ACT_1.4 | 58.0833 | 194.083 | .921 | .951 |

| ACT_2.1 | 58.2500 | 198.386 | .808 | .953 |

| ACT_2.2 | 58.6667 | 193.515 | .869 | .952 |

| ACT_2.3 | 57.6667 | 212.061 | .215 | .958 |

| ACT_3.1 | 58.5833 | 196.265 | .666 | .954 |

| ACT_3.2 | 58.0833 | 192.083 | .698 | .954 |

| ACT_3.3 | 58.1667 | 202.152 | .451 | .957 |

| ACT_4.1 | 57.9167 | 197.720 | .839 | .952 |

| ACT_4.2 | 58.3333 | 192.424 | .778 | .953 |

| ACT_4.3 | 58.5000 | 195.545 | .746 | .953 |

| ACT_5.1 | 58.5000 | 203.364 | .590 | .955 |

| ACT_5.2 | 58.5000 | 186.636 | .922 | .951 |

| ACT_5.3 | 58.0833 | 197.174 | .787 | .953 |

| ACT_5.4 | 58.5000 | 193.727 | .816 | .952 |

| ACT_6.1 | 57.8333 | 194.515 | .917 | .951 |

| ACT_6.2 | 57.4167 | 197.356 | .747 | .953 |

| ACT_7.1 | 57.0833 | 208.992 | .601 | .956 |

| ACT_7.2 | 57.0833 | 210.265 | .503 | .956 |

| ACT_7.3 | 57.3333 | 206.970 | .497 | .956 |

3.3.5. Subprocess 5

- Internal Consistency: The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient obtained was 0.903, while the alpha based on typed items was 0.913. These values indicate high internal reliability, suggesting that the items exhibit adequate homogeneity and consistently measure the construct underlying Subprocess 5.

- Item Descriptive Statistics: Item means ranged from 2.75 to 3.92, with an overall mean of 3.42, indicating a medium-high level of response. Standard deviations ranged from 0.29 to 1.42, showing moderate variability in participants’ responses.

- Interitem Correlations: Most correlations between items were positive to moderate, with some items exhibiting low or negative correlations with others, which could indicate items with a lower contribution to internal consistency. In particular, items such as ACT_1.2 and ACT_3.3 showed negative or very low correlations with certain items, suggesting the need for revision. The corrected item-total correlation ranged from -0.023 (ACT_3.3) to 0.775 (ACT_2.2).

- Cronbach’s alpha if the item is deleted: Deleting items with low correlation, such as ACT_3.3, does not substantially improve the overall Cronbach’s alpha, which remains above 0.90. This indicates that overall the items contribute positively to the instrument’s internal reliability.

| Items | Scale mean if item is deleted |

Scale variance if item is deleted | Corrected item-total correlation | Cronbach’s alpha if item is deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT_1.1 | 72.2500 | 93.295 | .602 | .897 |

| ACT_1.2 | 72.1667 | 99.424 | .050 | .913 |

| ACT_1.3 | 72.3333 | 88.061 | .492 | .902 |

| ACT_1.4 | 71.8333 | 93.788 | .557 | .898 |

| ACT_2.1 | 72.0833 | 91.720 | .545 | .898 |

| ACT_2.2 | 72.0000 | 86.364 | .775 | .891 |

| ACT_2.3 | 71.6667 | 90.242 | .721 | .893 |

| ACT_3.1 | 72.5833 | 86.447 | .493 | .904 |

| ACT_3.2 | 71.5000 | 97.000 | .569 | .899 |

| ACT_3.3 | 71.5000 | 101.545 | -.023 | .906 |

| ACT_4.1 | 71.5833 | 95.356 | .674 | .897 |

| ACT_4.2 | 72.0000 | 90.545 | .851 | .892 |

| ACT_4.3 | 71.5833 | 92.265 | .742 | .894 |

| ACT_5.1 | 72.1667 | 90.879 | .624 | .896 |

| ACT_5.2 | 71.7500 | 88.023 | .751 | .892 |

| ACT_5.3 | 71.4167 | 100.629 | .139 | .904 |

| ACT_5.4 | 72.0000 | 93.091 | .520 | .898 |

| ACT_6.1 | 71.7500 | 92.750 | .646 | .896 |

| ACT_6.2 | 71.9167 | 94.447 | .510 | .899 |

| ACT_7.1 | 71.7500 | 95.477 | .428 | .900 |

| ACT_7.2 | 71.9167 | 91.174 | .775 | .893 |

| ACT_7.3 | 72.2500 | 91.841 | .514 | .899 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UNIDO | United Nations Industrial Development Organization |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Program |

| BRICS | Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| ICMM | International Cooperation Management Model |

| MINEM | Ministry of Energy and Mines |

| UNE | Electrical Union |

| IHES | Indio Hatuey Experimental Station (University of Matanzas) |

| FFRC | Finland Futures Research Centre. University of Turku |

| CEDEL | Centre for Local and Community Development |

| MINCEX | Ministry of Foreign Trade |

| FFRC | Finland Futures Research Centre. University of Turku |

| INRH | National Institute of Hydraulic Resources |

Appendix A

| DIMENSIONS/ACTIVITIES: |

| 1. Strategic planning |

| 1.1 Identification of national priorities: Defining priority areas for the development of FRE and linking projects to national plans ensures coherence with local priorities and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). |

| 1.2 Formulation of viable projects: To design projects aligned with national needs and donor interests |

| 1.3 Analysis of technological and financial gaps: Identify specific needs in technology and financing. |

| 1.4 Political commitment: Political support at national and international levels is crucial to creating an enabling environment for practical cooperation. |

| 2. Articulation of actors |

| 2.1 Inter-institutional coordination: To establish coordination mechanisms between UNE, ministries and international organizations to avoid duplicating efforts and develop comprehensive strategies. |

| 2.2 Public-private partnerships: Promoting private sector participation in FRE projects is essential to mobilize resources and share experiences. |

| 2.3 Community participation: Involving local communities in project planning and implementation ensures that initiatives are relevant and sustainable. |

| 3. Innovation and Technology Transfer |

| 3.1 Acquisition of advanced technologies: Cooperation should include the use of new technologies to improve the effectiveness of projects and facilitate the exchange of information. |

| 3.2 Technological adaptation to the local context: To ensure that technologies are suitable for Cuban conditions, which guarantee sustainability |

| 3.3 Local capacity development: To train technicians and professionals in the use and maintenance of technologies. |

| 4. Training and capacity building |

| 4.1 Technical training programs: To implement courses and workshops for UNE staff and other key actors. |

| 4.2 International exchanges: To promote internships and technical visits to countries with experience in FRE. |

| 4.3 Citizen education and awareness: To develop awareness campaigns on the benefits of FRE. |

| 5. Financing and economic sustainability |

| 5.1 Mobilization of international resources: To create expertise to access international cooperation funds. |

| 5.2 Innovative financing mechanisms: to explore options such as green bonds, financial incentives and payment-by-results schemes. |

| 5.3 Financial sustainability of projects: To ensure that projects are economically viable in the long term, which guarantees their continuity. |

| 5.4 Diversity of cooperation modalities: Using approaches such as bilateral, multilateral, South-South and triangular cooperation allows combining resources and knowledge to maximize impact. |

| 6. Institutional strengthening |

| 6.1 Adaptation of the organizational structure: Strengthening includes training human resources, improving infrastructure, organizational structures and developing strong institutions. |

| 6.2 Effective governance: Promoting accountable and transparent governance helps build trust among local and international partners. |

| 7. Monitoring and evaluation |

| 7.1 Clear performance indicators: Establishing metrics to evaluate the progress of projects allows you to measure their real impact. |

| 7.2 Periodic reviews: To establish a monitoring system and conduct regular reviews to adjust strategies and correct deviations. |

| 7.3 Transparency and accountability: Ensuring that the organizations involved operate transparently is vital to maintaining trust and effectiveness in cooperation. Ensure that results are communicated in a clear and accessible manner. |

References

- United Nations. (2024). UNIDO Annual Report 2024, pages 6-10. https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/unido-publications/2025-04/UNIDO-AR2024-Spanish-ebook.pdf.

- UNDP. (2023). Annual Report on Development Cooperation 2024. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2024-03/informe_pnud_2023_regular_digital.pdf.

- UNDP. (2022). Strategic Plan 2022-2025. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2021-10/UNDP-Strategic-Plan-2022-2025-SP.pdf.

- European Parliament. (2025). Resolution on the implementation of the Union’s common foreign and security policy. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-10-2025-0057_ES.html.

- IRENA. (2025). Report of the 15th IRENA Assembly: Accelerating the transition to renewable energy. https://www.energiaestrategica.com/a-pesar-de-un-2024-record-irena-advierte-que-se-debe-triplicar-la-capacidad-de-renovables-en-el-mundo/.

- Petrone F. (2021). BRICS and Civil Society: Challenges and Future Perspectives in a Multipolar World. International Organisations Research Journal, vol. 16, no 4, pp. 171-195 (in English). [CrossRef]

- AECID. (2022). Intervention Formulation Document Model. Available at: https://repositorio.iica.int/bitstream/handle/11324/21564/5258-00.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Republic of Cuba. (2020). *Decree-Law No. 16 of 2020: On International Cooperation*. Official Gazette of the Republic of Cuba, Regular Edition No. 63. http://www.gacetaoficial.gob.cu.

- Romero, A. (2017). Cuban foreign policy and the updating of the economic model in a changing environment. Own Thought 45, pp. 81-110. http://www.cries.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/007-romero.pdf.

- Cabrera, V. (2014). International Cooperation for Development in Cuba. A Case Study. University Institute of Development and Cooperation IUDC—UCM. Working document No. 29, pp. 1-50. Available at: https://www.ucm.es/data/cont/docs/599-2014-05-19-PLMP_Finalista_Viviana.pdf.

- Korkeakoski, M; Filgueiras Sainz de Rozas, M.L. (2022). A look at the transition of the Cuban energy matrix. Energy Engineering. 2022. 43(3), September/December. e1508. Magazine site: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1815-59012022000300040&script=sci_arttext.

- Arias, D., Gavela, P., & Riofrio, J. (2022). State of the Art: Incentives and Strategies for Renewable Energy Penetration. Technical Journal “Energy”, 18(2 SE-ENERGY EFFICIENCY), pp. 91-103. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E., & Green, M. (2009). Making sense of change management (2nd ed.). Kogan Page. http://www.uop.edu.pk/ocontents/Change%20Management%20Book.pdf.

- Daft, R. L. (2021). Organization theory and design (13th ed.). Cengage Learning. https://www.studocu.com/row/document/abdul-wali-khan-university-mardan/business-organization/e-book-organization-theory-design-13th-edition-by-richard-daft/119022415.

- Navarro Claro, G. T., & Bayona Soto, J. A. (2024). From the Total Quality Paradigm to Quality 5.0: A Literature Review for the Manufacturing Sector. Journal of Social Sciences, 30, 551-566. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Saltos, L. M., González-González, A., & Vivas-Vivas, F. E. (2025). Analysis of the Level of Service and Production Quality at Mendoza S.A. Company. Scientific Journal INGENIAR: Engineering, Technology and Research. ISSN: 2737-6249, 8(15), 205-224. Retrieved from https://journalingeniar.org/index.php/ingeniar/article/view/289.

- Caldés, N., Del Río, P., Lechón, Y., & Gerbeti, A. (2018). Renewable energy cooperation in Europe: What next? Drivers and barriers to the use of cooperation mechanisms. Energies, 12(1), 70. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschini, F. R., Tuerk, A., & Frieden, D. (2023). Renewable Cooperation Mechanisms in the EU: Lessons Learned and Future Perspectives. Energies, 16(21), 7410. [CrossRef]

- Di Foggia, G., Beccarello, M., & Jammeh, B. (2024). A Global Perspective on Renewable Energy Implementation: Commitment Requires Action. Energies, 17(20), 5058. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., & Li, J. (2024). A Review of Renewable Energy Investment in Belt and Road Initiative Countries: A Bibliometric Analysis Perspective. Energies, 17(19), 4900. [CrossRef]

- Dębicka, A., Olejniczak, K., Radomski, B., Kurz, D., & Poddubiecki, D. (2024). Renewable Energy Investments in Poland: Goals, Socio-Economic Benefits, and Development Directions. Energies, 17(10), 2374. [CrossRef]

- Krug, M., Di Nucci, M. R., Schwarz, L., Alonso, I., Azevedo, I., Bastiani, M., Dyląg, A., Laes, E., Hinsch, A., Klāvs, G., Kudreņickis, I., Maleki, P., Massa, G., Meynaerts, E., Pappa, S., & Standal, K. (2023). Implementing European Union Provisions and Enabling Frameworks for Renewable Energy Communities in Nine Countries: Progress, Delays, and Gaps. Sustainability, 15(11), 8861. [CrossRef]

- Nergui, O., Park, S., & Cho, K.-w. (2024). Comparative Policy Analysis of Renewable Energy Expansion in Mongolia and Other Relevant Countries. Energies, 17(20), 5131. [CrossRef]

- Krug, M., Di Nucci, M. R., Caldera, M., & De Luca, E. (2022). Mainstreaming Community Energy: Is the Renewable Energy Directive a Driver for Renewable Energy Communities in Germany and Italy? Sustainability, 14(12), 7181. [CrossRef]

- Tatti, A., Ferroni, S., Ferrando, M., Motta, M., & Causone, F. (2023). The Emerging Trends of Renewable Energy Communities’ Development in Italy. Sustainability, 15(8), 6792. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sarihi, A., & Mansouri, N. (2022). Renewable Energy Development in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: Status, Barriers, and Policy Options. Energies, 15(5), 1923. [CrossRef]

- Adeshina, M. A., Ogunleye, A. M., Suleiman, H. O., Yakub, A. O., Same, N. N., Suleiman, Z. A., & Huh, J.-S. (2024). From Potential to Power: Advancing Nigeria’s Energy Sector through Renewable Integration and Policy Reform. Sustainability, 16(20), 8803. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Chirinos, R. A., Delgado Fernández, J. R., Pacheco Molina, A., Vivanco Ureña, C. I., Reyes Carrión, J. P., & Vivanco Ureña, J. (2025). Validación de contenido por expertos: concordancia interjueces y modelo estandarizado para instrumentos de investigación. Revista Latinoamericana De Educación, 3(3), e423–e423. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Quiroz, J., & Rioseco-Pais, M. (2025). Competencias digitales clave para la formación académica en estudiantes universitarios según el modelo DigComp: un estudio basado en juicio de expertos. Edutec, Revista Electrónica De Tecnología Educativa, (91), 269-286. [CrossRef]

- Piguave Carrera, K. D., Zúñiga Junco, X. M., Monge García, M. G., & Verdezoto Vizcarra, F. I. (2025). Percepción de Expertos sobre la Calidad Del Servicio en el MSP del cantón Quevedo mediante SERVQUAL. Tesla Revista Científica, 5(2), e450. [CrossRef]

- BROZIA, Ana Inés; BARITÉ, Mario. La opinión Experta Como Garantía: Elementos para un Abordaje Teórico y Metodológico. ISKO Brasil, [S. l.], n. 8, 2025. https://isko.org.br/ojs/index.php/iskobrasil/article/view/9.

- Sigüenza Orellana, Juan, Andrade Cordero, Celio, & Chitacapa Espinoza, Johanna. (2024). Validación del cuestionario para docentes: Percepción sobre el uso de ChatGPT en la educación superior. Revista Andina de Educación, 8(1), 000816. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Suárez, N., & Santoyo-Telles, F. (2024). Validesa de contingut per judici d’experts: integració quantitativa i qualitativa en la construcció d’instruments de mesura. REIRE Revista d’Innovació I Recerca En Educació, 17(2), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, O. D. R., García, T. R. G., & Suarez, J. A. T. (2024). Validación de contenido en cuestionarios de instrumentos utilizados en investigaciones de dirección en Educación Médica. Revista de Información científica para la Dirección en Salud. INFODIR. https://revinfodir.sld.cu/index.php/infodir/article/view/1611.

- Herrera Masó, Juan Rubén, Calero Ricardo, Jorge Luis, González Rangel, Miguel Ángel, Collazo Ramos, Milagros Isabel, & Travieso González, Yelamy. (2022). Method for expert consultation at three levels of validation. Revista Habanera de Ciencias Médicas, 21(1). Epub 10 de marzo de 2022. Recuperado en 24 de julio de 2025. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1729-519X2022000100014&lng=es&tlng=en.

- Castañeda Rodríguez, Taimi, López Domínguez, Abelardo, Collazo Frías, Victoria del Carmen, & Moirón Vallar, Olga Margarita. (2024). Instrumental reliability to measure the application of statistical techniques in physical culture: Cronbach’s Alp-ha. Transformación, 20(1), 128-144. Epub 01 de enero de 2024. Recuperado en 24 de julio de 2025. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2077-29552024000100128&lng=es&tlng=en.

- Carbonell-Abella, Cristina, Micó-Pérez, Rafael Manuel, Vargas-Negrín, Francisco, Bastida-Calvo, José Carlos, & Aguado-Acín, Pilar. (2025). Consenso Delphi sobre el manejo de pacientes con osteoporosis en atención primaria. Revista de Osteoporosis y Metabolismo Mineral, 17(1), 42-55. Epub 24 de abril de 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera Ramos, J.F., Kaechele, M., López Padrón, A., y Álvarez, A. (2025). Diseño y validación del cuestionario de conocimiento y percepciones sobre Inteligencia Artificial Generativa para futuros docentes. EDUTEC. Revista Electrónica de Tecnología Educativa, (92), 216-233. [CrossRef]

- Martínez Lara, Verónica, Ramírez de León, José Alberto, Morales Ramírez, Dionicio, & González Pérez, Brian. (2025). Diseño y validación de un instrumento para medir los hábitos saludables y el estado emocional en adolescentes. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 42(2), 219-231. Epub 19 de mayo de 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornetero, M. C. G., & López-Regalado, O. (2025). Validez y confiabilidad de instrumentos de investigación en el aprendizaje: una revisión sistemática. Revista Tribunal, 5(10), 653-675. [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, L. M., Diez, T. & López, A. (2022). Estructuración sistémica de los contenidos de la matemática en la ingeniería utilizando la habilidad usar asistentes matemáticos. Varona. Revista Científico Metodológica, (74), 64-74. Acceso: 10/05/2023. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1992-82382022000100064&Ing=es&tlng=es.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).