I. Introduction

The global automotive industry is currently under immense pressure to address environmental concerns, meet stringent fuel economy regulations, and shift toward sustainable manufacturing practices. A central strategy in achieving these objectives is the use of lightweight materials, which significantly contribute to reducing vehicle mass, enhancing fuel efficiency, and lowering greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, without compromising safety or performance [

1].

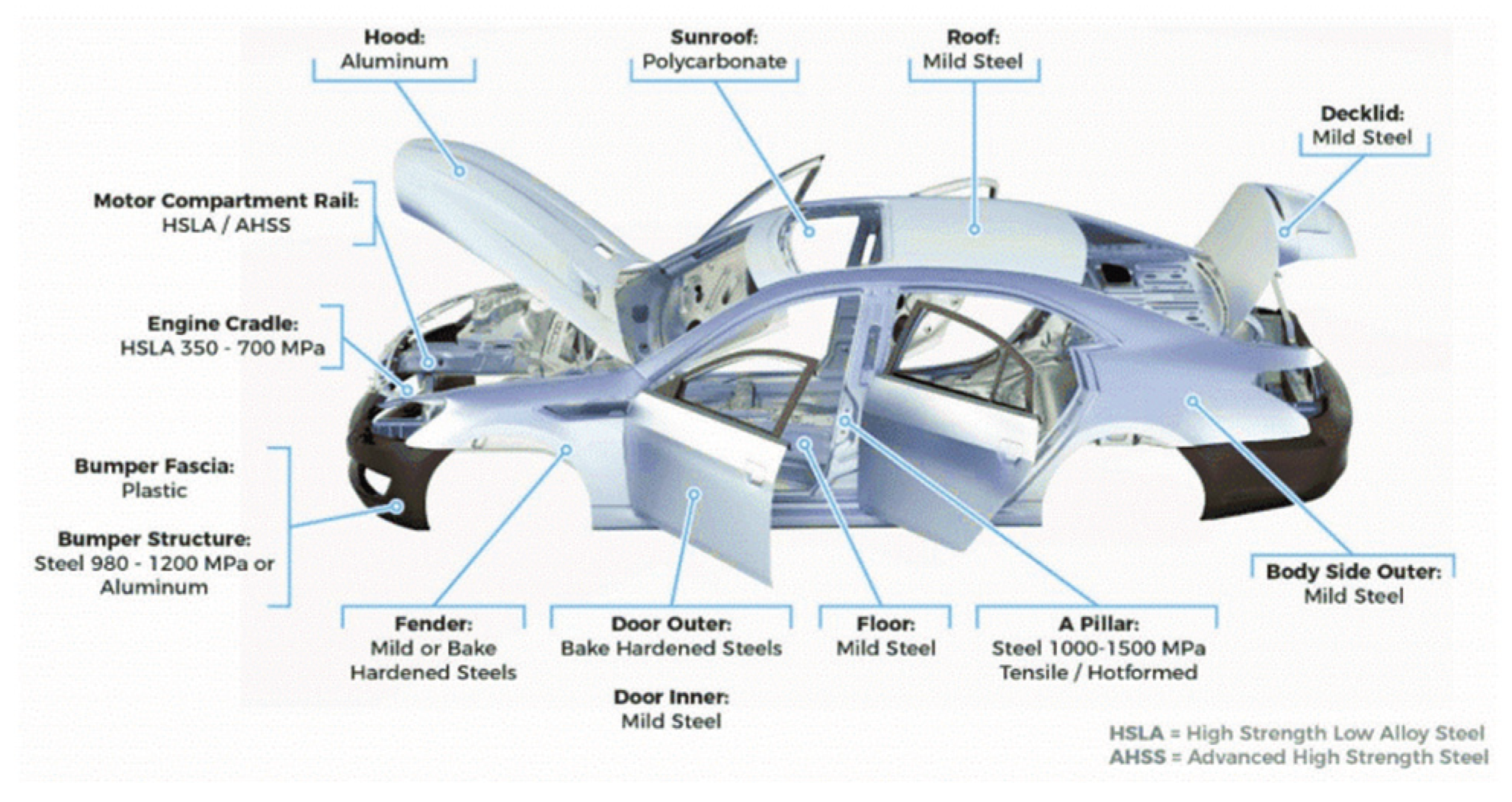

Figure 1.

Lightweight Material Distribution in Modern Vehicles (Source: Overview of current automotive materials, highlighting steel, aluminum, magnesium, and composites used in various body-in-white components).

Figure 1.

Lightweight Material Distribution in Modern Vehicles (Source: Overview of current automotive materials, highlighting steel, aluminum, magnesium, and composites used in various body-in-white components).

Vehicle weight reduction has long been recognized as a direct pathway to lower fuel consumption. According to widely cited studies, a 10% reduction in vehicle weight can result in a 6–8% improvement in fuel economy ([

2]). In the context of electric vehicles (EVs), light weighting is even more vital—it translates into greater driving range, reduced charging frequency, and more efficient power consumption. This has led to a dramatic rise in the use of aluminum alloys, magnesium alloys, titanium-based composites, and carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRPs) in modern EV manufacturing [

3].

In particular, composite materials—especially natural fiber-reinforced and hybrid composites—are playing a transformative role in automotive body design. These materials have been shown to reduce the weight of vehicle components by 10–60%, while also contributing to sustainability goals through improved recyclability and lower manufacturing emissions [

4]. They are increasingly favored not only for their low density and mechanical robustness but also for their potential to reduce the environmental footprint of the automotive lifecycle [

5].

Recent innovations in advanced manufacturing are amplifying these benefits. Techniques such as additive manufacturing, foam injection molding, and multi-material structural design are being employed to optimize material placement, enhance crash resistance, and minimize cost and waste [

6]. For example, graphene-polypropylene foams have emerged as a hybrid solution that offers superior stiffness, thermal insulation, and energy absorption, aligning well with safety and sustainability priorities [

7].

Another critical innovation is the integration of high-strength steels and stainless-steel alloys like grade 1.4376, which provide manufacturers with a unique balance between performance, cost-efficiency, and sustainability in structural parts such as the chassis and cylinder head [

8]. These materials also support efforts in modular manufacturing, making vehicle platforms more adaptable and lighter across different models [

9].

As industry standards evolve, manufacturers are increasingly required to demonstrate material efficiency across the entire product lifecycle. Lightweight designs are therefore not just about cutting mass, but also about achieving holistic optimization—balancing structural integrity, recyclability, cost, and crashworthiness [

10].

Emerging research points to integrated design frameworks that combine advanced materials with machine learning and digital twin technologies to simulate and validate lightweight designs in real-time, speeding up innovation while reducing trial-and-error costs [

11]. Such data-driven tools are essential for optimizing complex, multi-material structures and maintaining regulatory compliance [

12].

Finally, a promising direction in this domain is the development of biodegradable and bio-based lightweight composites, which offer performance on par with synthetic materials while addressing end-of-life disposal concerns. These innovations are likely to shape the future of sustainable automotive manufacturing, enabling greener and smarter mobility solutions [

13].

This review aims to comprehensively explore the development, processing methods, mechanical properties, and applications of lightweight materials in automotive design. It also delves into integration challenges, recyclability, cost-performance trade-offs, and future innovations, offering strategic insights for sustainable vehicle design.

II. Advanced High Strength Steels (AHSS)

Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) represent a class of steel alloys engineered to optimize strength-to-weight ratios, a critical requirement for the modern automotive industry seeking to achieve lightweight designs without compromising passenger safety. AHSS exhibit complex microstructures derived through sophisticated thermo-mechanical processing, enabling superior formability, high tensile strength, and excellent crash performance [

14].

The development of AHSS has evolved through three generations, each offering progressive improvements in ductility and strength. First-generation AHSS includes dual-phase (DP), transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP), complex-phase (CP), and martensitic (MS) steels, characterized by multiphase microstructures of ferrite, martensite, and bainite. These steels offer a balanced trade-off between ductility and strength and are widely adopted in body-in-white components [

15]. Second-generation steels, such as twinning-induced plasticity (TWIP) steels, exhibit high elongation due to mechanical twinning. However, they are less commercially viable due to their high alloying cost [

16]. The latest third-generation AHSS aims to deliver mechanical performance close to TWIP steels while minimizing alloying elements. Medium manganese steels and quenching and partitioning (Q&P) steels are representative of this generation and are under active development for mass production [

17].

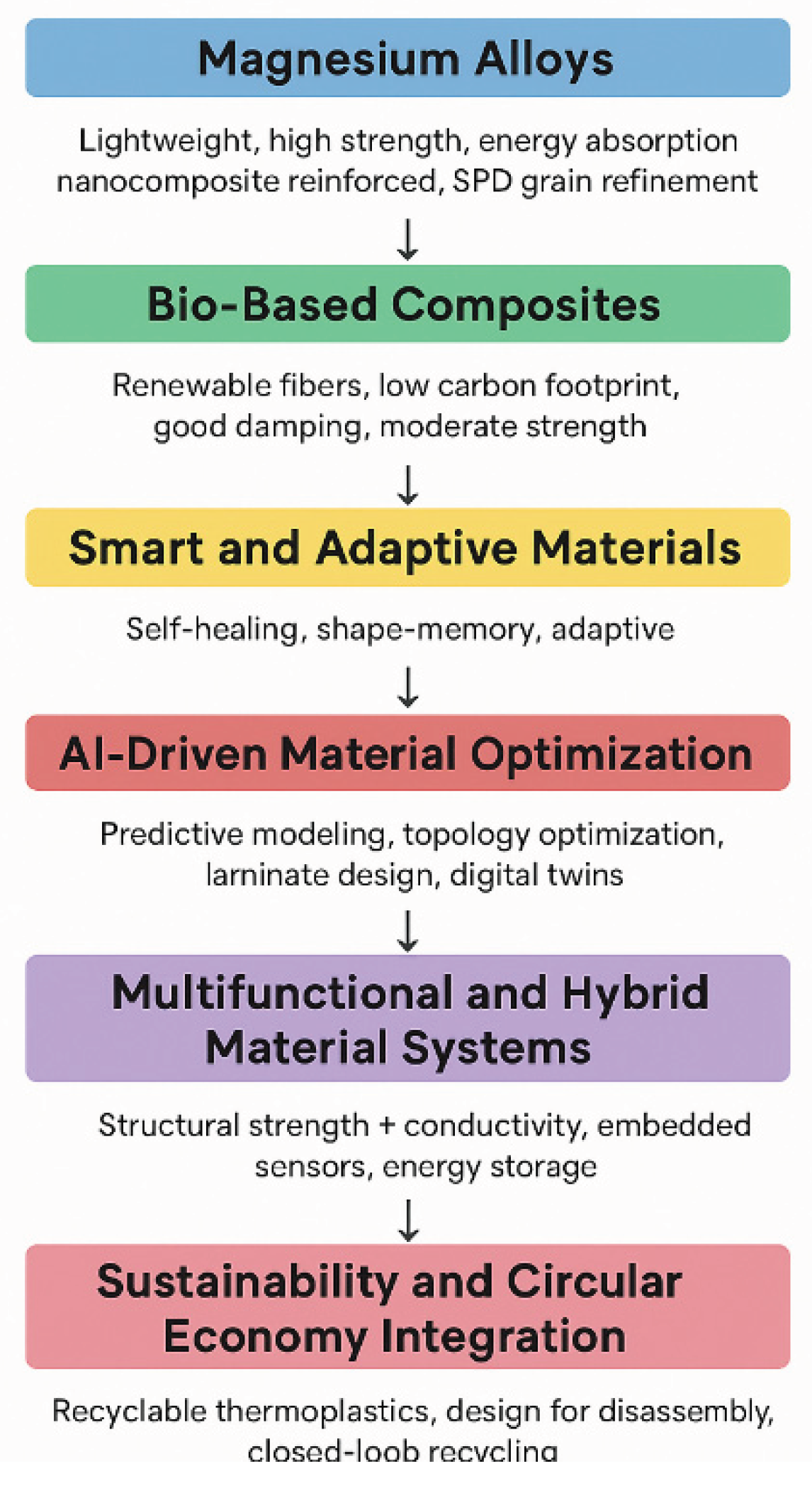

This evolutionary progression of AHSS is visually represented in

Figure 2, which plots steel grades on a strength versus ductility map. The classic “banana curve” illustrates the trade-off and improvements in mechanical performance across the three generations. First-generation AHSS such as DP and TRIP steels strike a balance between moderate strength and ductility, while second-generation TWIP steels exhibit exceptional elongation but are limited by cost. Third-generation steels—including Q&P and medium-Mn—push the curve toward the upper-right quadrant, combining high strength (above 1000 MPa) with enhanced ductility (30–60%), fulfilling the dual demand for crashworthiness and formability in automotive applications. This figure contextualizes the role of microstructural engineering in advancing steel performance, aligning closely with current automotive light weighting priorities.

Recent literature emphasizes the role of integrated computational materials engineering (ICME) in designing these complex alloys. Demeri (2024) extensively outlines how the incorporation of ICME principles has enabled more precise control over phase transformations and texture evolution during thermal treatments, ultimately improving crashworthiness and weight reduction outcomes [

14]. Moreover, research has shown that manufacturing routes such as Compact Strip Production (CSP) enhance the uniformity of thickness and microstructure across steel sheets, thus improving mechanical properties, particularly edge ductility [

18].

The formability of AHSS is intricately linked to microstructural features and edge conditions. Henrique et al. (2024) demonstrate that flange stretch ability in multiphase 780 MPa steels is significantly influenced by the method of edge preparation, with laser cutting offering superior hole expansion compared to mechanical punching

6. Similarly, intrinsic formability parameters such as strain localization and void nucleation behavior are central to predicting ductility under edge loading conditions. Investigations into the local toughness and its correlation with hole expansion ratio have yielded insights into formability limitations under complex stamping operations [

19].

Despite their high strength, AHSS present challenges in fracture behavior under dynamic and localized loading. It has been established that fracture resistance cannot be reliably inferred from conventional tensile tests alone, as factors such as retained austenite distribution, inclusion density, and microstructural inhomogeneity play a decisive role in crack propagation [

20]. Studies employing microstructural characterization and hole expansion testing underline the necessity for more comprehensive mechanical assessment methods, particularly when steels are used in crash-relevant components [

21].

The welding behavior of AHSS is another critical aspect influencing their integration into vehicle assemblies. Advanced joining techniques such as laser welding, gas metal arc welding (GMAW), and rotary friction welding (RFW) have shown varying levels of effectiveness in preserving joint strength and microstructural integrity. Salas Reyes et al. (2024) indicate that welded joints between dissimilar AHSS combinations are prone to increased corrosion susceptibility at the interface due to galvanic effects [

22]. Furthermore, joint efficiency is often reduced by the formation of hard, brittle phases within the heat-affected zone (HAZ), especially when high-strength martensitic grades are involved [

23]. The presence of hard inclusions such as TiN and susceptibility to liquid metal embrittlement (LME) during high-temperature operations remain significant obstacles to large-scale welding applications [

24].

Recent progress in the additive manufacturing of AHSS, particularly through laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) and selective laser melting (SLM), has opened new avenues for customizing geometries and optimizing part weight. However, Królicka and Malawska (2024) caution that these processes remain underdeveloped for AHSS, citing insufficient data on the behavior of medium-Mn and bainitic grades under rapid solidification conditions13. Further research is required to overcome residual stress management and cracking issues associated with laser-based manufacturing.

Microstructural evolution during processing is another focal point in the development of next-generation AHSS. Researchers have identified key mechanisms such as dislocation-controlled plasticity, martensitic transformation, and twinning at the austenite level as being central to the mechanical behavior of these materials14. Engineering austenite grain stability and phase retention is particularly vital in enhancing strain hardening and delay of necking in automotive applications. Novel approaches involving vacuum induction melting followed by austenite reversion heat treatments have achieved plastic strain energy densities exceeding 86 GPa%, marking significant strides in mechanical performance optimization15.

In conclusion, Advanced High Strength Steels continue to play a pivotal role in automotive light weighting strategies. Through microstructural innovation, tailored thermal processing, and integration of advanced manufacturing and joining techniques, AHSS offer a pathway to safer, lighter, and more energy-efficient vehicles. Future research must address existing challenges in weld ability, additive manufacturability, and fracture predictability to unlock their full potential in next-generation vehicle design.

III. Aluminum Alloys

Aluminum alloys have become integral to the light weighting strategies employed in the automotive sector due to their exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and energy absorption capacity. Their increasing utilization is primarily driven by the global demand to reduce vehicular emissions and improve fuel efficiency. However, the development and integration of aluminum alloy components in vehicles are accompanied by challenges in formability, recyclability, and cost, necessitating further material innovations and processing advancements.

A. Lightweight Optimization of Aluminum Components

Recent innovations in structural design have enabled significant reductions in the weight of aluminum-based automotive parts without compromising mechanical integrity. For instance, the front sub frame of a vehicle—a critical load-bearing component—was optimized using multi-objective topology optimization and particle swarm algorithms. This optimization achieved a 12% reduction in mass (2.4 kg) while preserving strength, static stiffness, and modal performance indices [

25]. Stress values remained below yield limits across multiple loading conditions, and critical stiffness levels were retained.

C. Material Properties and Alloying Strategies

The mechanical performance of aluminum alloys is heavily influenced by alloying elements and thermal processing. Alloys such as LM26 and Al–Si systems are preferred for their castability, strength, and fatigue resistance. Prakash [

27] highlighted the suitability of LM26 in dynamically loaded automotive parts due to its high thermal conductivity and endurance. Al-Si alloys benefit from silicon additions that refine microstructures and reduce porosity [

28].

Aluminum-silicon (Al-Si) alloys exhibit a versatile combination of mechanical and thermal properties, which can be significantly tailored through the careful addition of alloying elements.

Table 1 summarizes the effects of key alloying elements on Al-Si alloys, highlighting how each element contributes to specific material characteristics. Silicon (Si) is the primary alloying element and plays a crucial role in improving castability by reducing shrinkage and enhancing fluidity during solidification. Additionally, silicon refines the microstructure, reduces porosity, and improves wear resistance, making it suitable for engine and automotive components subjected to mechanical stress [

28]. Magnesium (Mg) contributes to strengthening via solid solution strengthening and precipitation hardening while also enhancing corrosion resistance, which is critical for automotive parts exposed to moisture and environmental degradation. Copper (Cu) further increases the hardness and thermal conductivity of the alloy, providing improved performance under elevated temperatures, while nickel (Ni) enhances high-temperature strength and creep resistance, enabling the alloy to withstand sustained thermal loads in critical applications. The combined effects of these alloying elements allow Al-Si alloys to achieve a balance of strength, wear resistance, thermal stability, and corrosion resistance, supporting their widespread use in high-performance automotive and aerospace components (Dash & Chen, 2023; Takata et al., 2022). These insights align with advanced alloy development strategies, such as quinary Al–Mg–Zn–Cu–Ni systems, where controlled formation of intermetallic phases like Al

3(Ni,Cu)

2 along grain boundaries further enhances creep resistance and thermal stability under demanding conditions [

29].

Table 1.

Performance Metrics of Optimized Aluminum Sub frame.

Table 1.

Performance Metrics of Optimized Aluminum Sub frame.

| Parameter |

Performance Metrics |

| Original Design |

Optimized Design |

Change |

| Weight |

20 kg |

17.6 kg |

-12% |

| Max Stress (MPa) |

180 |

140 |

-22% |

| First-order Modal Frequency |

92 Hz |

101 Hz |

+9.8% |

| Static Stiffness |

Comparable |

Maintained |

≈0% Change |

Table 2.

Effect of Alloying Elements on Al-Si Alloys.

Table 2.

Effect of Alloying Elements on Al-Si Alloys.

| Effect of Alloying Elements on Al-Si Alloys |

Alloying Element |

| Alloying Element |

Effect on Properties |

| |

Silicon (Si) |

Improves castability, wear resistance |

| |

Magnesium (Mg) |

Increases strength and corrosion resistance |

| |

Copper (Cu) |

Enhances thermal conductivity and hardness |

| |

Nickel (Ni) |

Improves high-temperature strength |

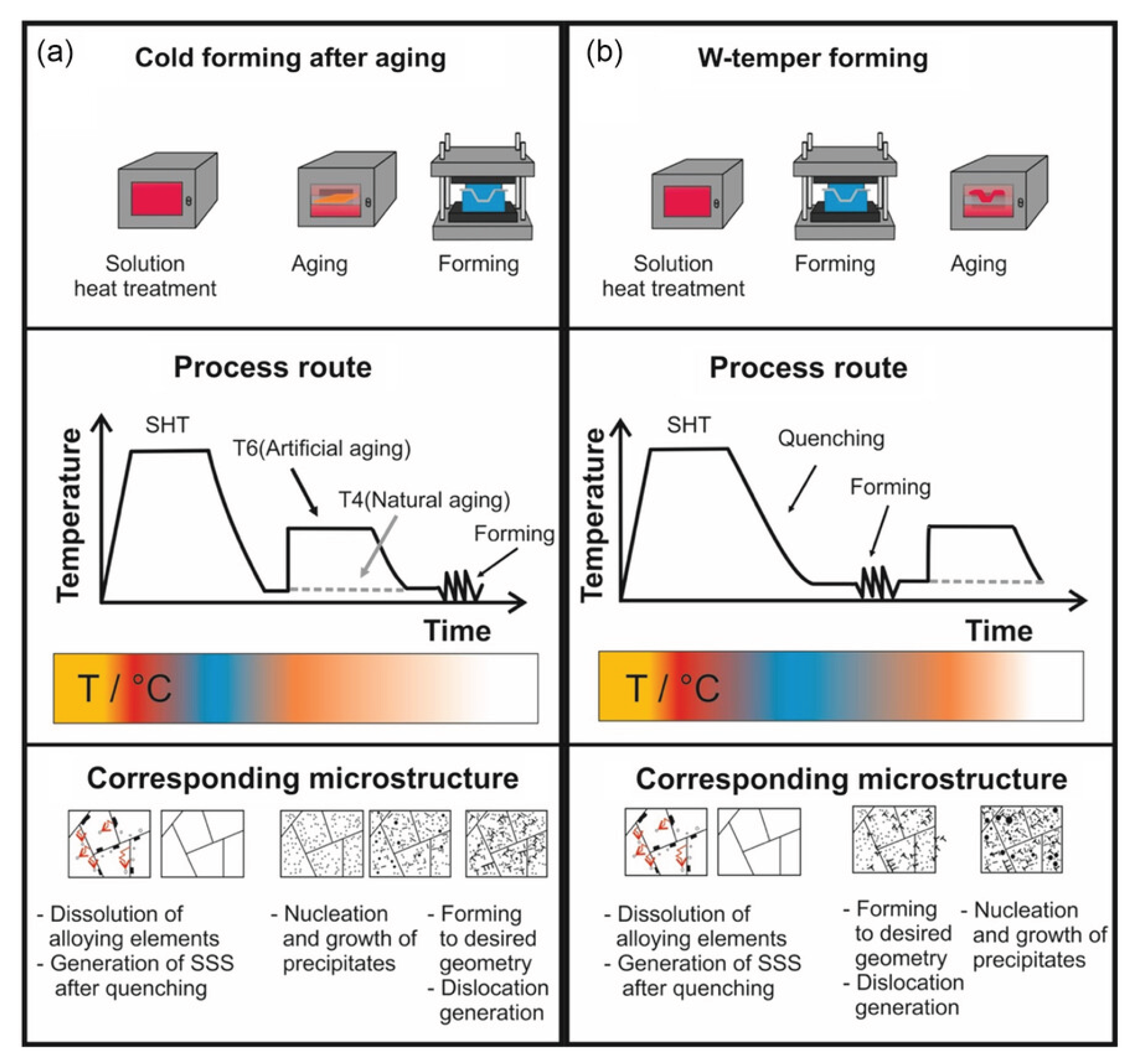

D. Advances in Alloy Design and Processing

Beyond conventional alloys, the Al-Mg-Zn(-Cu) system has emerged as a standout for automotive light weighting due to its mechanical performance and corrosion resistance. Shen [

30] emphasized that compositional design and microstructural control are critical for property enhancement. However, production scalability and economic feasibility remain limiting factors. The processing chain—including melting, homogenization, rolling, and heat treatment—must be optimized, especially under high-temperature pre-treatment (HTPT) conditions to enhance intergranular corrosion resistance and aging behavior.

To improve joining performance, Bamberg et al. (2022) investigated the effect of cladding technologies in resistance spot welding of Al-Mg-Si alloys. A cladded AW-6111 alloy with an AW-4040 layer demonstrated improved weld ability and reduced electrode degradation. While promising, cost-benefit analyses for mass production remain a subject of further investigation.

Additive manufacturing (AM) is another emerging frontier. Kotadia [

31] reviewed AM processes for Al alloys and identified challenges in microstructural control due to rapid solidification. Defect mitigation through microstructural modifications is key, though deeper metallurgical insight is needed to tailor alloys for AM-specific conditions.

Hybrid metal matrix composites (MMCs) based on Al–Mg–Si alloys reinforced with SiC and muscovite show potential for high-load applications. Sharma [

32] found that increasing muscovite content improves wear resistance while maintaining strength. However, environmental durability and long-term stability of such systems require further validation.

A notable innovation in processing, vibration-assisted rolling (VAR), was explored by Attarilar et al. (2021). VAR significantly enhanced the tensile and yield strength of AA5052 alloys by producing ultrafine-grained structures and favorable textures. Even post-annealing, materials retained superior properties, suggesting VAR as a cost-effective method for producing high-performance aluminum sheets.

E. Environmental and Recycling Considerations

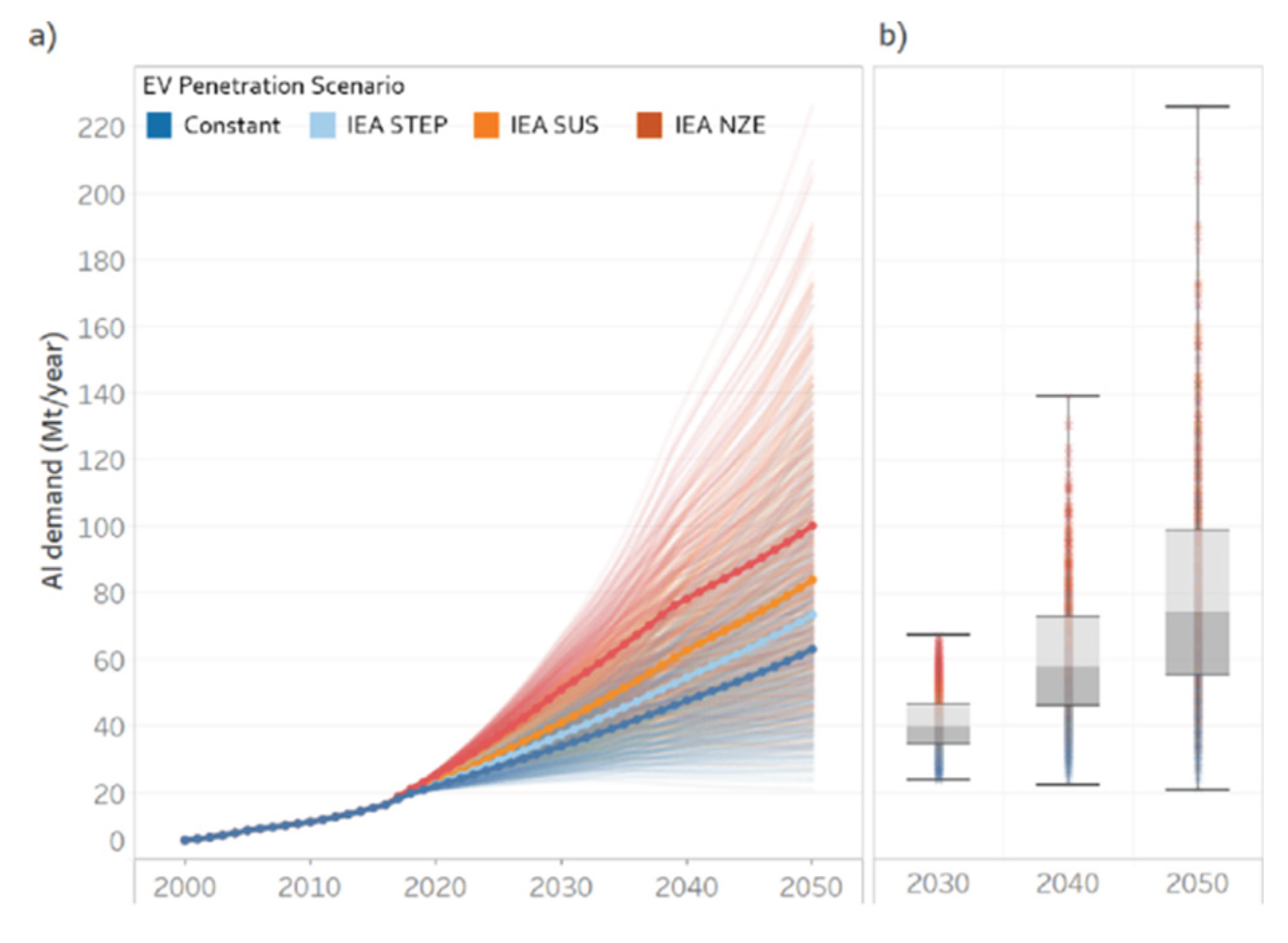

Although aluminum is highly recyclable, increased usage in vehicles introduces environmental and systemic recycling concerns. Billy and Müller project a fourfold increase in aluminum usage by 2050, largely due to electrification. However, this may result in excessive mixed-alloy scrap, particularly from castings, due to growing preference for wrought aluminum in electric vehicles. Innovations in alloy sorting and circular economy policies are crucial for mitigating these impacts.

Figure 4 illustrates this projected rise in global aluminum demand for passenger cars under different electrification scenarios. In part (a), each line represents a model run based on various parameter combinations, with thick dotted lines showing the average trend for scenarios such as Constant, STEP (Stated Energy Policies), SUS (Sustainable Development), and NZE (Net Zero Emissions). Part (b) presents a box-and-whisker plot for 2030, 2040, and 2050, depicting the statistical distribution of aluminum demand across all scenarios. Each colored dot signifies an individual simulation. The boxes encapsulate the interquartile ranges (IQR), while whiskers indicate extreme values. This visualization highlights the broad uncertainty range in material demand projections and underscores the importance of proactive policy and material management.

IV. Magnesium Alloys

The automotive industry faces increasing pressure to improve fuel efficiency and reduce emissions, driving the need for lightweight materials. Magnesium (Mg) alloys have emerged as a promising solution due to their exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, which is superior to aluminum and steel [

33]. With a density of only 1.74 g/cm

3, magnesium alloys can significantly reduce vehicle weight, leading to enhanced fuel economy and lower CO

2 emissions [

34]. Recent advancements in alloy design, processing techniques, and corrosion resistance have expanded the potential applications of magnesium alloys in automotive components. This section reviews the latest developments in magnesium alloys for lightweight automotive parts, focusing on mechanical properties, fabrication methods, and challenges in implementation.

Mechanical Properties and Alloy Design for Automotive Applications

Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of magnesium alloys to achieve high strength and stiffness, making them suitable for structural automotive components. Zhu et al. [

35] developed an Mg-11Y-1Al alloy with a yield strength of 350 MPa and 8% elongation, combining high mechanical performance with improved corrosion resistance. Similarly, multicomponent magnesium alloys have been designed to achieve exceptional compressive strength up to 627 MPa and a Young’s modulus of 65 GPa [

36], which is critical for load-bearing parts such as chassis and suspension systems.

The Mg-Sn-based alloys have also gained attention due to their aging response and mechanical performance. Zhuo et al. [

37] reviewed the relationship between aging treatment and room-temperature strength, highlighting that optimized Mg-Sn alloys can provide a balance between strength and ductility. Furthermore, the development of high-performance Mg–Al–Ca alloys processed via high-pressure die casting (HPDC) has shown yield strengths of up to 196 MPa after aging treatment [

38], making them viable for engine blocks and transmission cases.

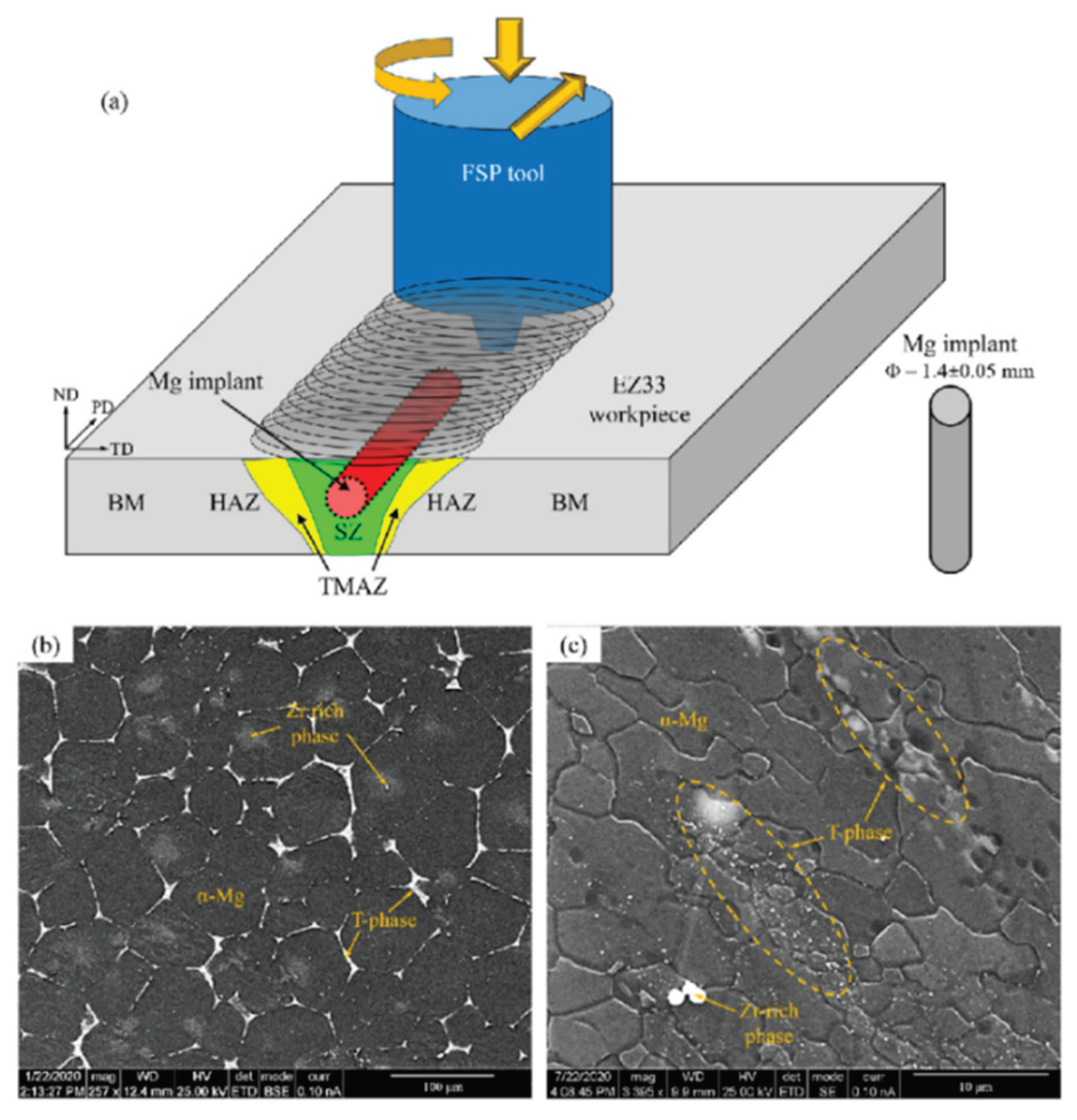

A. Friction Stir Processing (FSP) and Additive Manufacturing

Friction stir processing (FSP) has been widely adopted to refine the microstructure of magnesium alloys, improving their mechanical properties. Wang et al. [

39] demonstrated that FSP enhances grain refinement and homogenization, leading to superior strength and ductility. Additionally, selective laser melting (SLM) has emerged as a promising technique for fabricating complex magnesium components with high relative density (up to 99%) and improved mechanical properties compared to traditional casting [

40].

Figure 5 illustrates the microstructural evolution of an EZ33 magnesium alloy subjected to FSP. The process effectively refines grains and breaks down precipitates, contributing to enhanced mechanical performance critical for automotive applications.

B. Advanced Processing and Applications of Magnesium Alloys in Automotive Components

The template is used to format your paper and style the text. All margins, column widths, line spaces, and text fonts are prescribed; please do not alter them. You may note peculiarities. For example, the head margin in this template measures proportionately more than is customary. This measurement and others are deliberate, using specifications that anticipate your paper as one part of the entire proceedings, and not as an independent document. Please do not revise any of the current designations.

Magnesium alloys are increasingly utilized in automotive applications due to their lightweight nature, high strength-to-weight ratio, and excellent energy absorption characteristics. Recent advancements focus on enhancing mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and manufacturability through innovative processing techniques and nanocomposite reinforcement.

Thixomolding and Nanocomposite Reinforcement:

The thixomolding process has been effectively employed to disperse graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) into AZ91D magnesium alloys. This technique produces strong interfacial bonding between the matrix and the nanoparticles, resulting in enhanced mechanical properties suitable for lightweight structural components such as brackets and housings [

41].

Severe Plastic Deformation (SPD) for Grain Refinement:

SPD techniques, including equal-channel angular pressing (ECAP) and high-ratio differential speed rolling (HRDSR), have been instrumental in producing ultrafine-grained magnesium alloys. These fine-grained microstructures improve both strength and ductility, which are essential for forming automotive sheets with enhanced stretch formability [

42,

43].

Corrosion Resistance and Surface Modifications:

A significant limitation of magnesium alloys is their poor corrosion resistance. Strategies such as micro-alloying with calcium (Ca) and aluminum (Al) have shown promise in improving corrosion performance. Deng et al. [

44] reported that Ca micro-alloying reduces corrosion rates to below 0.1 mm/y in NaCl solutions. Similarly, Al-assisted passive film growth (Y

2O

3/Y(OH)

3 and Al

2O

3/Al(OH)

3) significantly enhances corrosion resistance in Mg-Y-Al alloys [

36].

Applications in Automotive Components:

Structural and Body Parts: Magnesium alloys are increasingly used in door frames, seat frames, and roof structures due to their lightweight nature and high stiffness. Development of high-ductility Mg alloys has enabled their application in crash-relevant components, where energy absorption is critical [

36,

45].

Powertrain and Engine Components: High-pressure die-cast Mg-Al-Ca alloys are used in transmission cases and oil pans, offering excellent thermal conductivity and strength. The WZA631 alloy, characterized by equiaxed α-Mg grains and LPSO phases, demonstrates superior high-temperature performance [

38,

46].

Interior and Miscellaneous Parts: Carbon nanotube (CNT)-reinforced Mg composites have been explored for self-lubricating and wear-resistant parts such as steering columns and pedal brackets. CNT additions enhance tribological performance while maintaining lightweight properties [

47].

Challenges and Future Directions:

Despite advancements, key challenges remain:

Anisotropy and Ductility: Magnesium alloys exhibit intrinsic brittleness at room temperature, limiting formability. Future research should target texture modification and alloy design to improve ductility [

48].

Corrosion Resistance: While micro-alloying improves corrosion performance, long-term durability under harsh conditions requires further investigation [

35].

Cost-Effectiveness: Industrial adoption depends on scalability and production cost optimization [

49].

V. Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymers (CFRPs)

Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymers (CFRPs) have emerged as a pivotal material in the ongoing revolution of the automotive industry, primarily due to their exceptional properties such as high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and thermal stability. The global automotive sector’s drive toward fuel efficiency, reduced emissions, and enhanced vehicle dynamics has catalyzed the incorporation of CFRPs into various components. This shift is further supported by the urgent demand for electrification and light weighting in electric vehicles (EVs), where weight directly influences battery range and efficiency. In 2021, global CFRP demand reached 181 kilotons, more than doubling since 2014, and is projected to reach 285 kilotons by 2025, highlighting the material’s rapid adoption in key industries including aerospace, wind energy, and increasingly, automotive sectors [

50].

The integration of CFRPs into automotive designs has shown substantial benefits in reducing the weight of structural components without compromising mechanical performance. Structural applications are among the most prominent in the automotive use of CFRPs. Components such as vehicle chassis, B-pillars, crash boxes, roof panels, and floor structures have been effectively re-engineered using CFRPs. For instance, CFRP floor panels achieved a 27.5% weight reduction—approximately 6.8 kilograms—while still conforming to stringent crashworthiness standards and impact resistance benchmarks [

50]. Similarly, CFRP-reinforced B-pillars have demonstrated superior energy absorption capabilities compared to their steel counterparts, offering significant weight savings along with improved crash performance metrics [

51].

One of the major benefits of CFRPs in automotive engineering lies in their high specific strength and stiffness. Unlike conventional metallic materials like steel or aluminum, CFRPs allow for the design of parts that are not only lighter but also stronger in specific orientations. This advantage becomes particularly significant in safety-critical zones of vehicles where the structure must withstand substantial loads while minimizing mass. Additionally, the thermal and chemical stability of CFRPs makes them ideal for under-the-hood applications and battery enclosures in EVs, where exposure to fluctuating temperatures and harsh conditions is common.

The role of CFRPs extends beyond structural parts to functional and aesthetic interior applications. Steering columns, seat frames, pedal brackets, and dashboard components are increasingly being fabricated from CFRP materials due to their wear resistance, self-lubrication (especially when reinforced with carbon nanotubes), and ability to maintain dimensional stability over long durations. These benefits, combined with CFRPs’ modern aesthetic appeal, have also contributed to their rising popularity among automotive designers and OEMs.

Furthermore, CFRPs have found significant applications in electric vehicles, particularly in protecting high-voltage battery packs. A notable example is the use of thermoplastic CFRP battery underbody shields that limit deformation during ground impacts to less than 5 mm, thereby safeguarding the structural integrity of battery systems and enhancing passenger safety. As battery technology evolves, CFRPs offer a robust solution for lightweight and thermally stable encapsulation.

Recent advancements in CFRP technology have further propelled their automotive applicability. The integration of graphene oxide (GO) into CFRP matrices has shown to improve interfacial bonding between fibers and resin, leading to notable enhancements in tensile strength, thermal conductivity, and durability [

52]. Sharma et al. (2022) found that GO-reinforced epoxy CFRPs demonstrated improved load transfer efficiency due to better adhesion between carbon fibers and the polymer matrix. Similarly, novel fiber sizing techniques using cationic poly(amide-imide) were shown to increase interlinear shear strength by up to 56.8%, thereby extending the fatigue life of the composite [

53].

Thermoplastic CFRPs represent another major innovation. Unlike traditional thermoset-based CFRPs, thermoplastics such as PEEK and PET offer recyclability, faster processing cycles, and improved toughness. These advantages position thermoplastics as an ideal matrix for high-volume automotive applications. The capability to reshape or reform components using heat without compromising mechanical integrity makes thermoplastic CFRPs especially appealing for modular vehicle design and end-of-life material recovery strategies.

Additive manufacturing (AM), particularly fused filament fabrication (FFF) and fused deposition modeling (FDM), has opened new horizons for CFRP implementation. By embedding continuous carbon fibers into polymer filaments during the printing process, highly complex and optimized structures can be fabricated with tailored mechanical properties. Although current limitations such as fiber impregnation uniformity and interlayer adhesion persist, ongoing research shows promise. Notably, co-extrusion processes have achieved tensile strength prediction errors below 5%, with nylon matrices yielding optimal results in printed CFRP components [

56].

VI. Hybrid Composites

Hybrid composites have emerged as a transformative class of materials in the automotive industry, driven by the imperative need for lightweight, high-performance, and sustainable alternatives to traditional metal-based components. These composites are engineered by combining two or more types of reinforcements—typically natural and synthetic fibers or metals with ceramics—in a polymeric or metallic matrix, which enables a synergistic enhancement of mechanical, thermal, and tribological properties beyond those achievable by conventional monolithic materials [

1,

2].

A. Natural/Synthetic Polymer Hybrid Composites

Natural/synthetic hybrid composites have emerged as a promising class of materials for automotive applications, combining the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of natural fibers with the superior mechanical properties of synthetic reinforcements [

56]. Recent research has demonstrated their potential in enhancing crashworthiness, reducing vehicle weight, and improving environmental sustainability, though challenges remain in optimizing their performance for widespread industrial adoption [

57].

Crashworthiness and Energy Absorption Performance

Thin-walled structures fabricated from natural/synthetic hybrid composites have shown significant potential as energy-absorbing components in automotive safety systems, including crush boxes, impact attenuators, and battery enclosures [

56]. Awd Allah et al. (2025) conducted a comprehensive review of these structures, highlighting that circular cross-sections exhibit superior energy absorption compared to square or rectangular geometries due to more stable deformation modes under axial crushing [

56]. While natural fiber-reinforced composites (NFCs) can achieve energy absorption levels comparable to glass fiber-reinforced polymers (GFRPs), they still fall short of carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRPs) [

56]. This performance gap has driven research into hybridization strategies, where natural fibers such as flax, jute, or hemp are combined with synthetic reinforcements like glass or carbon fibers to achieve an optimal balance of mechanical properties and cost efficiency [

58].

The energy absorption mechanisms in these hybrid composites are influenced by several factors, including fiber-matrix interfacial bonding, stacking sequences, and geometric triggers [

56]. Foam filling has been identified as an effective method to enhance energy absorption efficiency by promoting more uniform plastic deformation, while geometric triggers help reduce initial peak loads during impact events [

56]. However, the strain-rate sensitivity of these materials remains a complex issue, with performance under dynamic loading conditions often differing from quasi-static behavior depending on the dominant failure mechanisms [

56].

Material Challenges and Enhancement Strategies

One of the most significant limitations of natural fibers in structural applications is their inherent hydrophilicity, which leads to moisture absorption and subsequent degradation of mechanical properties [

58]. This issue is particularly problematic for automotive components exposed to variable environmental conditions. Recent studies have explored multiple approaches to mitigate moisture sensitivity, including chemical treatments (alkali, silane, acetylation), polymer coatings, and the incorporation of nanofillers such as graphene or nanoclay [

58]. These modifications not only improve water resistance but also enhance fiber-matrix adhesion, leading to better stress transfer and overall mechanical performance [

58].

Fiber consistency and quality present additional challenges, as natural fibers exhibit variability in properties due to factors such as plant source, growth conditions, and processing methods [

59]. This variability can lead to inconsistencies in composite performance, necessitating rigorous quality control measures. Optimization of manufacturing processes, including resin transfer molding (RTM) and compression molding, has been shown to improve fiber alignment and reduce defects, thereby enhancing the reproducibility of hybrid composite components [

59].

Automotive Applications and Industry Adoption

The automotive industry has increasingly adopted natural/synthetic hybrid composites for both interior and exterior applications, driven by regulatory pressures for light weighting and sustainability [

57]. Interior components such as door panels, seat backs, and parcel shelves have been primary targets for implementation due to their non-structural or semi-structural nature [

57]. For instance, BMW has successfully integrated natural fiber composites into the i3 electric vehicle, where injection-molded polyamide seat backrests weighing only 2 kg demonstrate significant weight reduction without compromising performance [

57]. Similarly, Ford’s use of pultruded composite beams in the F-150 Lightning highlights the potential of hybrid materials in structural applications, offering improved crash protection while reducing weight [

57].

Figure 6.

Seat backrests in the BMW i3 electric vehicle [

2].

Figure 6.

Seat backrests in the BMW i3 electric vehicle [

2].

Exterior applications have also seen progress, with sheet molding compounds (SMC) being used for closures such as hoods and lift gates [

57]. Continental Structural Plastics has demonstrated that SMC components can compete with aluminum in terms of weight reduction while offering greater design flexibility for complex geometries. The growing electrification of vehicles has further expanded opportunities for hybrid composites, particularly in battery enclosures where their combination of lightweight properties and impact resistance is highly valued [

57]. Tesla’s Model 3 battery enclosure exemplifies this trend, utilizing composite materials to achieve both weight savings and structural protection for battery systems.

VII. Future Outlook and Emerging Innovations

The evolution of materials used in automotive engineering is at a pivotal juncture, driven by the intersecting demands of environmental sustainability, vehicle electrification, intelligent systems, and cost efficiency. Lightweight materials, long a focus of performance-driven design, are now expected to be multifunctional, adaptive, and environmentally conscious. This section outlines the key future directions and innovations shaping the next generation of automotive materials.

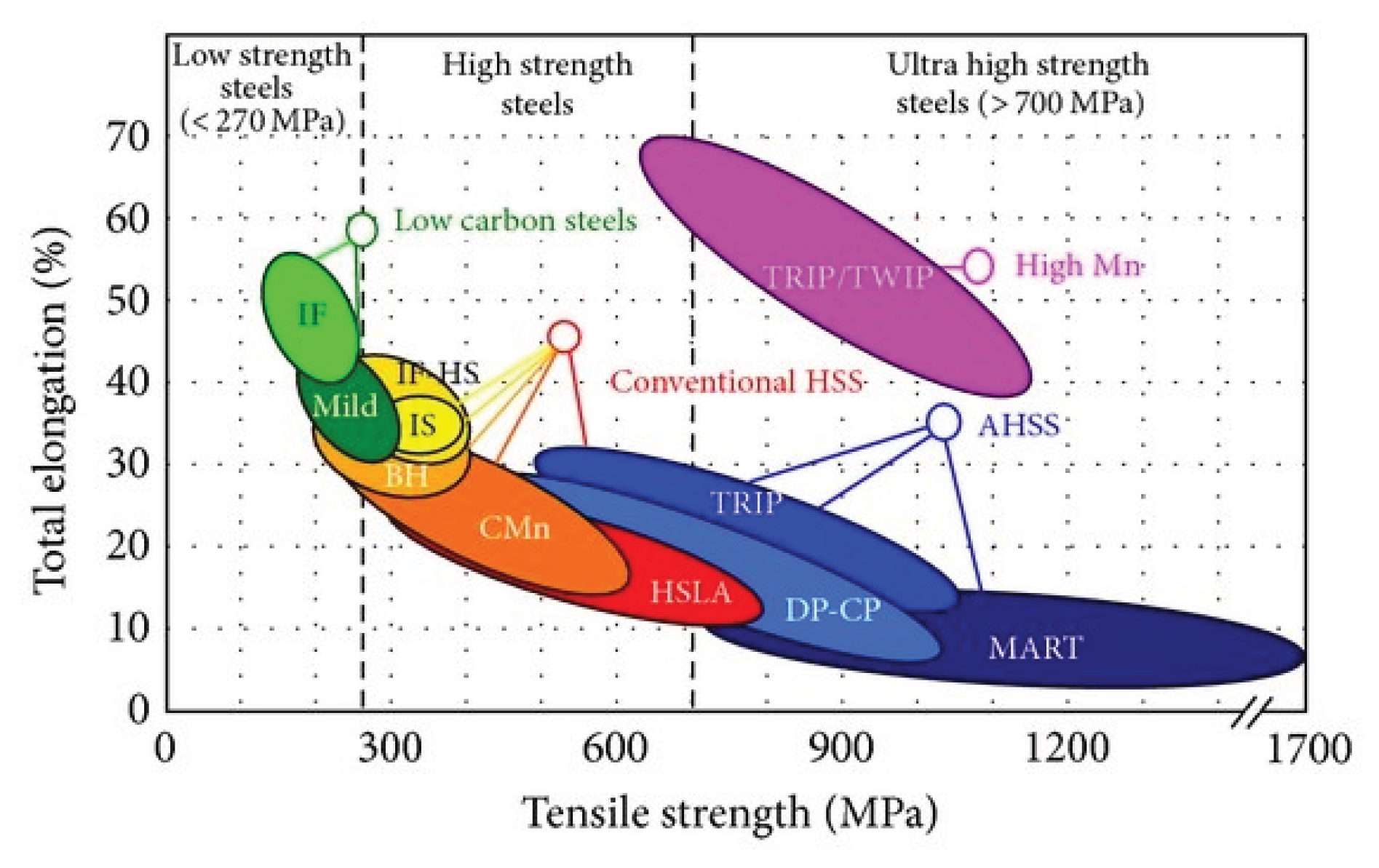

Magnesium alloys have emerged as highly attractive materials for automotive applications due to their low density, high strength-to-weight ratio, and excellent energy absorption capabilities. Recent advances focus on enhancing mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and manufacturability through innovative processing techniques and nanocomposite reinforcement. For instance, the dispersion of graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) into AZ91D magnesium alloys has been shown to improve interfacial bonding and mechanical strength, making them suitable for lightweight structural components such as brackets and housings. Severe plastic deformation (SPD) techniques, including equal-channel angular pressing (ECAP) and high-ratio differential speed rolling (HRDSR), enable ultrafine-grained microstructures that enhance both strength and ductility, facilitating the production of automotive sheets. Corrosion resistance can be further improved through micro-alloying with elements like calcium or aluminum, combined with the formation of protective passive films (Y2O3/Y(OH)3, Al2O3/Al(OH)3). Magnesium alloys find applications in structural and body parts (door and seat frames), powertrain components (transmission cases, oil pans), and interior elements (steering columns, pedal brackets), although challenges such as intrinsic brittleness, anisotropy, long-term corrosion resistance, and industrial scalability remain critical considerations.

Figure 7.

Materials for Next-Generation Automotive Applications.

Figure 7.

Materials for Next-Generation Automotive Applications.

Alongside metallic solutions, bio-based composites are gaining attention as sustainable alternatives to conventional synthetic materials. These composites replace petrochemical-based polymers with renewable natural fibers, such as flax, hemp, jute, kenaf, and sisal, embedded in biodegradable or recyclable matrices like polylactic acid (PLA) or bio-based epoxies. They offer reduced reliance on fossil resources, lower life-cycle carbon emissions, good vibration damping, and high strength-to-weight ratios. Typically applied in non-load-bearing parts such as door panels, headliners, seat backs, and trims, ongoing research focuses on fiber surface functionalization, nano-reinforcement (e.g., nanocellulose, graphene), and hybridization with synthetic fibers to improve moisture resistance, fiber consistency, and flammability, potentially extending their use to semi-structural components.

Smart and adaptive materials further expand the capabilities of modern vehicles by sensing, responding, and adapting to environmental or structural changes. Self-healing composites enable autonomous repair of micro-cracks through microcapsules, vascular networks, or reversible covalent bonding, while shape-memory polymers (SMPs) can return to predefined shapes under heat, electrical current, or light. Such materials find applications in crashworthy sub frames, energy-absorbing zones, adjustable aerodynamic components, and thermally adaptive insulation layers, enhancing vehicle lifespan, safety, and maintenance efficiency.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are increasingly integrated into material design, accelerating optimization and application. AI-driven predictive modeling can anticipate material behavior under complex loads, while topology optimization reduces weight without compromising strength. Automated laminate design—including fiber orientation, stacking, and resin content—along with data-driven material screening, supports rapid R&D and real-time quality control. Coupled with finite element analysis (FEA) and digital twin technologies, these approaches allow full lifecycle simulations, minimizing physical prototyping and optimizing performance.

Modern automotive demands also call for multifunctional and hybrid material systems. Hybrid nanocomposites combine mechanical strength with thermal or electrical conductivity, making them ideal for battery housings and electronics. Structural composites embedded with sensors enable real-time health monitoring of cracks, stress, and temperature, while energy-storing laminates act as structural batteries or capacitive materials, supporting mechanical loads while storing energy. These multifunctional materials facilitate system-level integration, paving the way for smart, connected, and energy-efficient vehicles.

Finally, sustainability and circular economy principles are increasingly central to material selection. Strategies include recyclable thermoplastic composites for remelting and reshaping, design for disassembly (DfD) to enable easy material separation, closed-loop recycling of waste carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRP) into reusable fibers or fillers, and low-temperature solvolysis for energy-efficient fiber recovery. Future trends point toward the use of material passports, embedding detailed composition, sourcing, and recyclability metadata to ensure transparency and regulatory compliance throughout automotive manufacturing.

VIII. Conclusions

The automotive industry’s shift toward lightweight materials is driven by the urgent need to enhance fuel efficiency, reduce emissions, and improve vehicle performance, particularly in the era of electrification. This review has explored the latest advancements in Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS), aluminum alloys, magnesium alloys, carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRPs), and hybrid composites, evaluating their mechanical properties, manufacturing challenges, and applications in modern automotive design. AHSS remains a cornerstone for structural components due to its high strength and crashworthiness, though weldability and fracture resistance require further refinement. Aluminum alloys offer an optimal balance between weight reduction and durability, yet their formability and recycling complexities demand innovative processing techniques. Magnesium alloys, with their ultra-low density, hold immense potential but face limitations in corrosion resistance and ductility, necessitating advances in micro-alloying and severe plastic deformation methods. CFRPs stand out for their exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, particularly in electric vehicles, but high costs and recyclability issues must be addressed to facilitate mass adoption. Hybrid composites, combining natural and synthetic reinforcements, present a sustainable alternative, though challenges in moisture sensitivity and manufacturing scalability persist.

Looking ahead, the future of automotive light weighting will be shaped by smart materials, bio-based composites, and AI-driven design optimization, enabling multifunctional solutions that enhance performance while minimizing environmental impact. Self-healing polymers, shape-memory alloys, and structural batteries are emerging as game-changers, offering adaptive and energy-efficient solutions. Additionally, the integration of circular economy principles—such as recyclable thermoplastics and closed-loop material systems—will be crucial in achieving sustainable automotive manufacturing. As the industry moves toward autonomous and electrified mobility, continued innovation in material science and manufacturing technologies will be essential to overcoming existing limitations and unlocking the full potential of lightweight materials. By prioritizing sustainability, safety, and efficiency, automakers can pave the way for a new generation of vehicles that are not only lighter and more efficient but also environmentally responsible. The ongoing evolution of lightweight materials underscores their critical role in shaping the future of transportation, ensuring greener and smarter mobility solutions for years to come.

References

- W. Zhang and J. Xu, “Advanced lightweight materials for automobiles: A review,” Materials & Design, vol. 221, p. 110994, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Guo, X. Zhou, and Z. Liu, “Advanced lightweight structural materials for automobiles: Properties, manipulation, and perspective,” Science of Advanced Materials, vol. 16, no. 5, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Wei, Z. Zhou, Z. Liu, and L. Wang, “A review of some new materials for lightweight and better performance purposes in vehicle components,” Theoretical and Natural Science, vol. 28, no. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Anonymous, “Roles of composite materials for the application of lightweight automotive body parts and their environmental effect: Review,” International Journal of Scientific Research in Science and Technology, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 293, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Shiferaw, A. Tegegne, A. Asmare, B. Wubneh, and T. Belachew, “An overview of the role of composites in the application of lightweight body parts and their environmental impact: Review,” Engineering Solid Mechanics, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 33–45, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. G. Boopathi, M. S. Muthuraman, R. Palka, et al., “Modeling and simulation of electric motors using lightweight materials,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 14, p. 5183, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. C. V. R. M. Naidu, N. Kalidas, S. Venkatachalam, et al., “Microstructure, worn surface, wear assessment and Taguchi’s approach of titanium alloy hybrid metal matrix composites for automotive applications,” SAE Technical Paper Series, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Pradeep, A. M. Deshpande, B. Shah, et al., “Advancing automotive light-weighting: Material–Process–Microstructure–Performance (MP2) relationships of supercritical foam injection of PP–graphene nanocomposite foams and over-molding,” SAE International Journal of Materials and Manufacturing, vol. 13, no. 5, p. 0019, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. E. K. Sato and T. Nakata, “Analysis of the impact of vehicle lightweighting on recycling benefits considering life cycle energy reductions,” Resources, Conservation and Recycling, vol. 164, p. 105118, 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Mundt and L. C. Schröder, “Innovative and sustainable lightweight solutions while staying cost-competitive,” in Proceedings, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Kayacan, S. Pischinger, K. Ahlborn, et al., “Additively manufactured lightweight automobile cylinder head—A new process for structural optimization from concept to validated hardware,” SAE International Journal of Engines, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Stolz and X. Fang, “New method for lightweight design of hybrid components made of isotropic and anisotropic materials,” Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization, 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, L. Yang, Y. Gong, et al., “Lightweight design of multi-material body structure based on material selection method and implicit parametric modeling,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. R. M. Asyraf, M. R. Ishak, M. Rafidah, R. A. Ilyas, N. M. Nurazzi, M. N. F. Norrrahim, et al., “Natural/Synthetic Polymer Hybrid Composites—Lightweight Materials for Automotive Applications,” in Green Hybrid Composite in Engineering and Non-Engineering Applications, Singapore: Springer Nature, 2023, pp. 159–177.

- S. Choudhary, M. K. Sain, V. Kumar, P. Saraswat, and M. K. Jindal, “Advantages and applications of sisal fiber reinforced hybrid polymer composites in automobiles: A literature review,” Materials Today: Proceedings, 2023.

- Q. Wang, T. Chen, X. Wang, Y. Zheng, J. Zheng, G. Song, and S. Liu, “Recent progress on moisture absorption aging of plant fiber reinforced polymer composites,” Polymers, vol. 15, no. 20, p. 4121, 2023.

- Z. Sun, F. L. Guo, Y. Q. Li, J. M. Hu, Q. X. Liu, X. L. Mo, et al., “Effects of carbon nanotube-polydopamine hybridization on the mechanical properties of short carbon fiber/polyetherimide composites,” Composites Part B: Engineering, vol. 236, p. 109848, 2022.

- S. J. Arunachalam, S. Thanikodi, and R. Saravanan, “Effect of nano-hybridization on flexural and impact behavior of jute/kenaf/glass fiber-epoxy composites for automotive application,” Results in Engineering, vol. 25, p. 104571, 2025.

- C. M. Mohanraj, R. Rameshkumar, M. Mariappan, A. Mohankumar, B. Rajendran, P. Senthamaraikannan, et al., “Recent Progress in Fiber Reinforced Polymer Hybrid Composites and Its Challenges—A Comprehensive Review,” Journal of Natural Fibers, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 2495911, 2025.

- G. Gebremichael, S. Tesfaye Mekonone, T. Mucheye Baye, and A. Asratie Ejigu, “Mechanical and microstructural characterization of sisal fiber-reinforced polyester laminate composites for improved durability in automotive applications,” Journal of Materials Science: Composites, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 1, 2025.

- Z. G. A. K. Al-Jlaihawi, S. Ghani, A. A. Diwan, and A. A. Taher, “Enhancement of Mechanical Properties of Hybrid Composite Materials,” Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education, vol. 12, no. 11, pp. 298–302, 2021.

- S. Ishtiaq, M. Q. Saleem, R. Naveed, M. Harris, and S. A. Khan, “Glass–Carbon–Kevlar fiber reinforced hybrid polymer composite (HPC): Part (A) mechanical and thermal characterization for high GSM laminates,” Composites Part C: Open Access, vol. 14, p. 100468, 2024.

- F. Mohamed, S. Yaknesh, G. Radhakrishnan, and P. M. Kumar, “FEA of composite leaf spring for light commercial vehicle: Technical note,” International Journal of Vehicle Structures and Systems, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 369–371, 2020.

- M. I. Khan, S. Soni, A. Patel, and C. Nayak, “Weight optimization of leaf spring assembly using design for manufacturing approach and FEM in graduated leaves for Electric Vehicle,” International Journal of Applied Mechanics and Engineering, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 89–100, 2025.

- Y. Sun, J. He, and W. Li, “Multi-objective lightweight optimization design of the aluminum alloy front subframe of a vehicle,” Metals, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 705, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Scharifi, V. A. Yardley, U. Weidig, D. Szegda, J. Lin, and K. Steinhoff, “Hot sheet metal forming strategies for high-strength aluminum alloys: A review,” Advanced Engineering Materials, vol. 25, no. 7, p. 2300141, 202. [CrossRef]

- P. Prakash, A. M. A. Rani, and M. Hussain, “Experimental analysis of LM 26 aluminum alloy in automotive application,” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 1176, no. 1, p. 012007, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Dash and D. Chen, “A review on processing–microstructure–property relationships of Al-Si alloys: Recent advances in deformation behavior,” Metals, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 609, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Takata, A. Suzuki, and M. Kobashi, “Design of heat-resistant Al–Mg–Zn–Cu–Ni quinary alloy: Controlling intermetallic phases and mechanical performance at elevated temperature,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, p. 144055, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Shen, X. Chen, J. Yan, L. Fan, Z.-Q. Yang, J. J. Zhang, and R.-F. Guan, “A review of progress in the study of Al-Mg-Zn(-Cu) wrought alloys,” Metals, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 345, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Kotadia, G. J. Gibbons, A. Das, and P. D. Howes, “A review of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing of aluminium alloys: Microstructure and properties,” Additive Manufacturing, p. 102155, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Sharma, J. Singh, M. K. Gupta, M. Mia, S. P. Dwivedi, A. Saxena, et al., “Investigation on mechanical, tribological and microstructural properties of Al–Mg–Si–T6/SiC/muscovite-hybrid metal-matrix composites for high strength applications,” Journal of Materials Research and Technology, vol. 10, pp. 368–383, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Gao, Y. Li, Y. Zhu, and L. Zhang, “Designing lightweight multicomponent magnesium alloys with exceptional strength and high stiffness,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 847, p. 143901, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhu, Y. Li, F. Cao, et al., “Towards development of a high-strength stainless Mg alloy with Al-assisted growth of passive film,” Nature Communications, vol. 13, p. 6016, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Verma, S. Kumar, and S. Suwas, “Evolution of microstructure and texture during hot rolling and subsequent annealing of the TZ73 magnesium alloy and its influence on tensile properties,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 823, p. 141480, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. R. Zhuo, L. Zhao, W. Gao, et al., “Recent progress of Mg-Sn based alloys: The relationship between aging response and mechanical performance,” Journal of Materials Research and Technology, vol. 20, pp. 3332–3344, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, H. Peng, P. Peng, et al., “Friction stir processing of magnesium alloys: A review,” Acta Metallurgica Sinica (English Letters), vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 355–368, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang, B. Jiang, D. Chen, et al., “Strategies for enhancing the room-temperature stretch formability of magnesium alloy sheets: A review,” Journal of Materials Science, vol. 56, pp. 14480–14517, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Ahmadi, S. Tabary, D. Rahmatabadi, et al., “Review of Selective Laser Melting of magnesium alloys: Advantages, microstructure and mechanical characterizations, defects, challenges, and applications,” Journal of Materials Research and Technology, vol. 19, pp. 1822–1840, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Liwen, Y. Zhao, L. Muxi, et al., “Reinforced AZ91D magnesium alloy with thixomolding process facilitated dispersion of graphene nanoplatelets and enhanced interfacial interactions,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 802, p. 140793, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Maqbool, N. Z. Khan, and A. N. Siddiquee, “Towards Mg based light materials of future: Properties, applications, problems, and their mitigation,” Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, vol. 144, no. 3, p. 030801, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Matli, A. Krishnan, V. Manakari, et al., “A new method to lightweight and improve strength to weight ratio of magnesium by creating a controlled defect,” Journal of Materials Research and Technology, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 2614–2621, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, J. Zhang, J. Wang, et al., “Toward the development of Mg alloys with simultaneously improved strength and ductility by refining grain size via the deformation process,” International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy, and Materials, vol. 28, pp. 154–164, 2021. [CrossRef]

- U. M. Chaudry, S. Tekumalla, M. Gupta, et al., “Designing highly ductile magnesium alloys: Current status and future challenges,” Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences, vol. 46, no. 5, pp. 443–474, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Shen, X. Chen, J. Yan, et al., “A review of progress in the study of Al-Mg-Zn(-Cu) wrought alloys,” Metals, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 345, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Deng, L. Wang, D. Höche, et al., “Approaching ‘stainless magnesium’ by Ca micro-alloying,” Materials Horizons, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 872–878, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bai, B. Ye, L. Wang, et al., “A novel die-casting Mg alloy with superior performance: Study of microstructure and mechanical behavior,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 804, p. 140655, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhou, “Microstructure, tribology, and corrosion characteristics of hot-rolled AZ31 magnesium alloy,” in Materials Horizons, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gökçe, “Metallurgical assessment of novel Mg–Sn–La alloys produced by high-pressure die casting,” Metals and Materials International, vol. 26, pp. 810–820, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, G. Lin, U. K. Vaidya, et al., “Past, present and future prospective of global carbon fibre composite developments and applications,” Composites Part B: Engineering, vol. 264, p. 110463, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Pawlak, T. Górny, Ł. Dopierała, and P. Paczos, “The Use of CFRP for Structural Reinforcement—Literature Review,” Metals, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 1470, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Sharma, S. Thakur, and R. Ahlawat, “Enhancing Mechanical Properties of CFRP Composites Using Graphene Oxide: A Review,” Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 56, pp. 2147–2153, 2022.

- J. Xie, L. Liu, Q. Zhang, and J. Zhang, “Improvement in interlaminar shear strength of CFRP composites via fiber sizing,” Composite Structures, vol. 261, p. 113590, 2021.

- C. S. Hiremath and N. M. Badiger, “3D Printing of Continuous CFRP Composites by FDM Technology,” Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 27, pp. 214–221, 2020.

- H. Li, Y. Zhao, Q. Wang, and C. Sun, “Structural Optimization of CFRP Wheels Based on DOE and FEA,” Composite Structures, vol. 309, p. 116835, 2023.

- M. M. Awd Allah, M. F. Abd El-Halim, A. S. Almuflih, S. F. Mahmoud, D. I. Saleh, and M. A. Abd El-baky, “Innovative, high-performance, and cost-effective hybrid composite materials for crashworthiness applications,” Polymer Composites, 2025.

- L. Yan and H. Xu, “Lightweight composite materials in automotive engineering: State-of-the-art and future trends,” Alexandria Engineering Journal, vol. 118, pp. 1–10, 2025.

- C. M. Mohanraj, R. Rameshkumar, M. Mariappan, A. Mohankumar, B. Rajendran, P. Senthamaraikannan, et al., “Recent Progress in Fiber Reinforced Polymer Hybrid Composites and Its Challenges—A Comprehensive Review,” Journal of Natural Fibers, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 2495911, 2025.

- M. Pant and S. Palsule, “Study on flax and ramie fibers reinforced functionalized polypropylene hybrid composites: Processing, properties, and sustainability assessment,” Journal of Polymer Research, vol. 32, no. 1, p. 8, 2025.

- C. Dong, “Carbon and glass fibre-reinforced hybrid composites in flexure,” Hybrid Advances, vol. 10, p. 100471, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).