1. Introduction

Accurate Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) information is essential for applications ranging from agricultural monitoring and forest management to urban planning and climate change adaptation [12,15,16]. Over the past decade, freely available medium-resolution satellite data, particularly from the Sentinel-2 constellation [11], have transformed the ability to generate such information at regional and global scales. At the same time, advances in machine learning—especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [22] and, more recently, transformer-based models [10]—have driven rapid improvements in classification accuracy.

Benchmark datasets such as EuroSAT [18] have played a central role in these developments. By providing large volumes of labeled Sentinel-2 image patches, they have enabled reproducible experiments and accelerated methodological innovation. Reported accuracies on EuroSAT often exceed 98%, creating an impression that LULC classification with Sentinel-2 is largely a solved problem. However, this perception contrasts sharply with the reality observed in operational systems, where accuracies typically fall in the 75-85% range [1,4,43]. This discrepancy between academic benchmarks and real-world performance raises important methodological and practical questions.

Several factors contribute to this gap. Methodological issues, including spatial autocorrelation in validation design [24], can lead to substantial overestimation of accuracy. Domain adaptation remains a major challenge: models trained in one geographic region or time period often fail to generalize when applied elsewhere [20,40]. The availability and diversity of labeled data further complicate the picture, with operational systems requiring vast amounts of annotated samples [19]. Even when multi-spectral bands are exploited [28], the gains are modest relative to the additional computational costs.

Recognizing these challenges, this review analyzes recent literature on Sentinel-2-based LULC classification, with emphasis on studies published between 2020 and 2024. The objective is to identify the methodological pitfalls that inflate benchmark performance, assess the factors limiting transferability to operational contexts, and evaluate current best practices for improving reliability. In doing so, the review aims to provide both a synthesis of the state of the art and practical recommendations for bridging the gap between research results and real-world applications.

2. Review Scope and Methodology

This review examines recent advances and challenges in Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) classification using Sentinel-2 imagery, with particular emphasis on the performance gap between benchmark datasets and operational systems. Rather than attempting complete coverage, this review focuses on identifying key methodological issues, performance patterns, and best practices that have emerged in recent literature.

2.1. Literature Coverage

The review draws on peer-reviewed studies published primarily between 2020 and 2024, identified through Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar using search terms including: “Sentinel-2”, “land use land cover classification”, “deep learning”, “domain adaptation”, “accuracy assessment”, “EuroSAT” and “operational land cover”. Additional references were identified through citation chaining from important works in the field.

The selection prioritized studies that:

Report quantitative results on LULC classification using Sentinel-2 imagery with clear validation methodologies;

Include performance metrics such as overall accuracy, F1-score, or kappa coefficient;

Apply machine learning or deep learning approaches in either benchmark or operational contexts;

Provide transparent reporting of both successes and limitations;

Represent diverse geographic regions and application domains.

Foundational works published prior to 2020 are also cited to provide essential theoretical and methodological background, including the Sentinel-2 mission description, the EuroSAT benchmark dataset, and important contributions on accuracy assessment and domain adaptation.

2.2. Synthesis Approach

This review employs a thematic synthesis approach, organizing findings around key themes that emerged from the literature: (i) the benchmark-to-operations performance gap, (ii) methodological pitfalls inflating accuracy claims, (iii) domain adaptation challenges, (iv) training data requirements, and (v) operational deployment considerations. Where possible, we highlight consensus findings across multiple studies and identify areas of ongoing debate or uncertainty in the field.

3. Current State of Real-World LULC Classification Performance

3.1. Achievable Accuracy Benchmarks

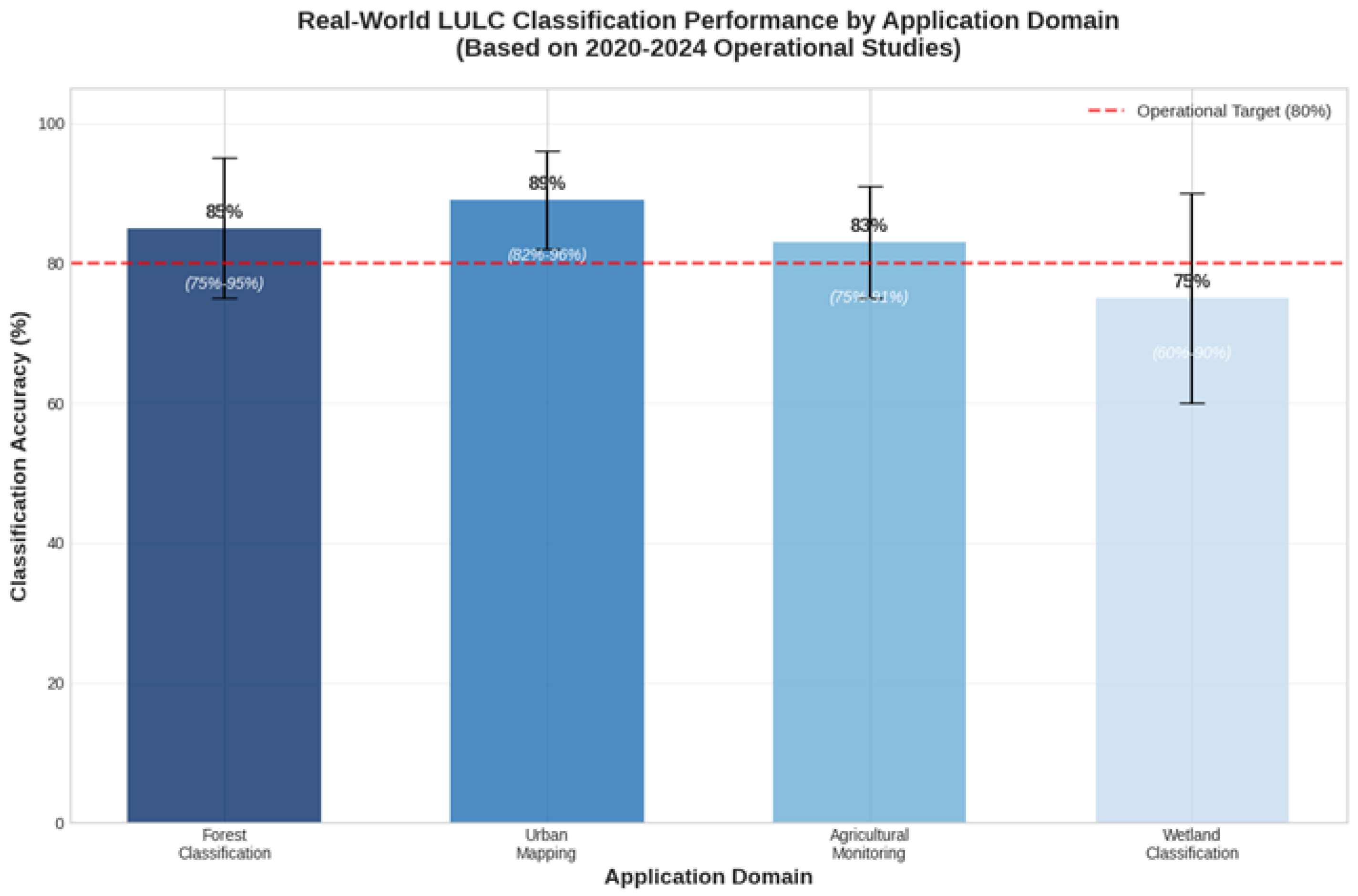

Recent literature (2020-2024) consistently indicates that operational LULC classification systems based on Sentinel-2 imagery typically achieve overall accuracies between 75% and 85%, a level that remains well below the >98% often reported in benchmark settings [5,9]. Performance varies across application domains and geographic regions, reflecting differences in landscape complexity, data availability, and methodological design (

Figure 1).

Forests generally represent one of the strongest classes, with accuracies commonly reaching 85-95% in dense forest areas, but dropping to 65-80% in mixed or fragmented forest conditions [23]. Urban land cover tends to be more consistent, with built-up detection usually reported in the 88-96% range. Agricultural monitoring shows moderate performance: crop type classification is often situated between 83-91%, but results vary depending on crop diversity and field size [2,28].

Individual case studies highlight both the potential and the limitations of current approaches. For example, Forkuo et al. (2024) achieved 93.8% accuracy with a Random Forest classifier for forest mapping in the Congo Basin, supported by extensive field validation [14]. Similarly, multi-temporal ensemble approaches have reported exceptional results, with accuracies above 98% when using extended time series [26]. Such outcomes, however, remain the exception rather than the norm.

3.2. Application-Specific Performance Patterns

Wetlands remain the most challenging application domain. Boundary delineation typically achieves only 70-90% accuracy, while wetland type classification rarely exceeds 65-85% [30]. These limitations are linked to the inherent spectral similarity of wetland classes and seasonal variations in water levels, which reduce classification separability.

By contrast, temporal analysis has proven to be an effective strategy for dynamic land cover types. Multi-temporal use of Sentinel-2 imagery often delivers 10-15% improvements compared to single-date classifications in agricultural applications, although the magnitude of this gain depends strongly on crop type and phenological stage [9].

4. The EuroSAT Benchmark Paradox

4.1. Exceptional Benchmark Performance

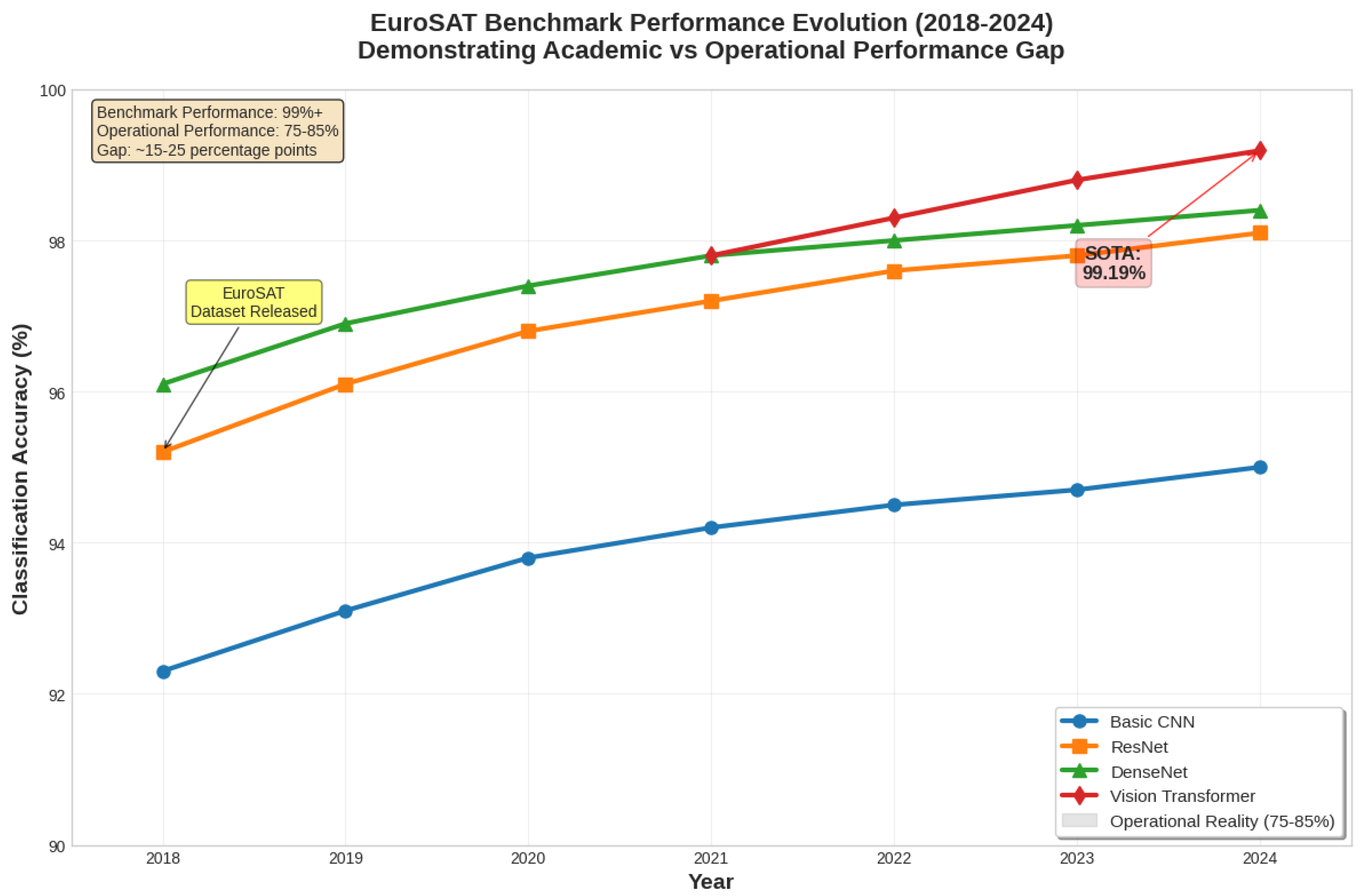

The EuroSAT dataset continues to demonstrate outstanding results in benchmark experiments. Recent evaluations using Vision Transformer models have reported accuracies close to 99%, confirming that this dataset provides conditions highly favorable to classification [10]. With 27,000 standardized image patches of 64×64 pixels, EuroSAT represents an idealized environment in which class boundaries are clear and consistent.

State-of-the-art deep learning architectures—CNNs, ResNets, DenseNets, and Transformers—routinely achieve above 98% accuracy on EuroSAT [21].

Figure 2 illustrates the progression of reported performance across these architectures. While these results showcase the rapid methodological advances of the last five years, they also create expectations that are rarely matched in operational contexts, where performance typically remains in the 75–85% range.

4.2. Domain Adaptation Challenges

The transition from EuroSAT to real-world applications exposes substantial domain adaptation difficulties. Models trained on European datasets often lose 15–25% accuracy when applied in African or Asian regions, primarily due to differences in climate, vegetation phenology, and soil reflectance [20,40]. Vegetation classification is particularly sensitive: phenological variability strongly influences spectral signatures, requiring fine-tuning or retraining when models are deployed in tropical or arid conditions [24].

Temporal generalization adds another layer of complexity. Single-season models frequently experience 10–20% degradation when applied to different seasonal windows [5]. Multi-temporal approaches can partially mitigate this effect, but reported gains of 4–7% remain insufficient to fully address domain adaptation limitations. Together, these findings highlight that while EuroSAT serves as a powerful benchmark for methodological innovation, it does not reflect the challenges inherent in transferring models to diverse geographic and temporal settings.

5. Methodological Pitfalls Inflating Accuracy Claims

5.1. Spatial Autocorrelation in Cross-Validation

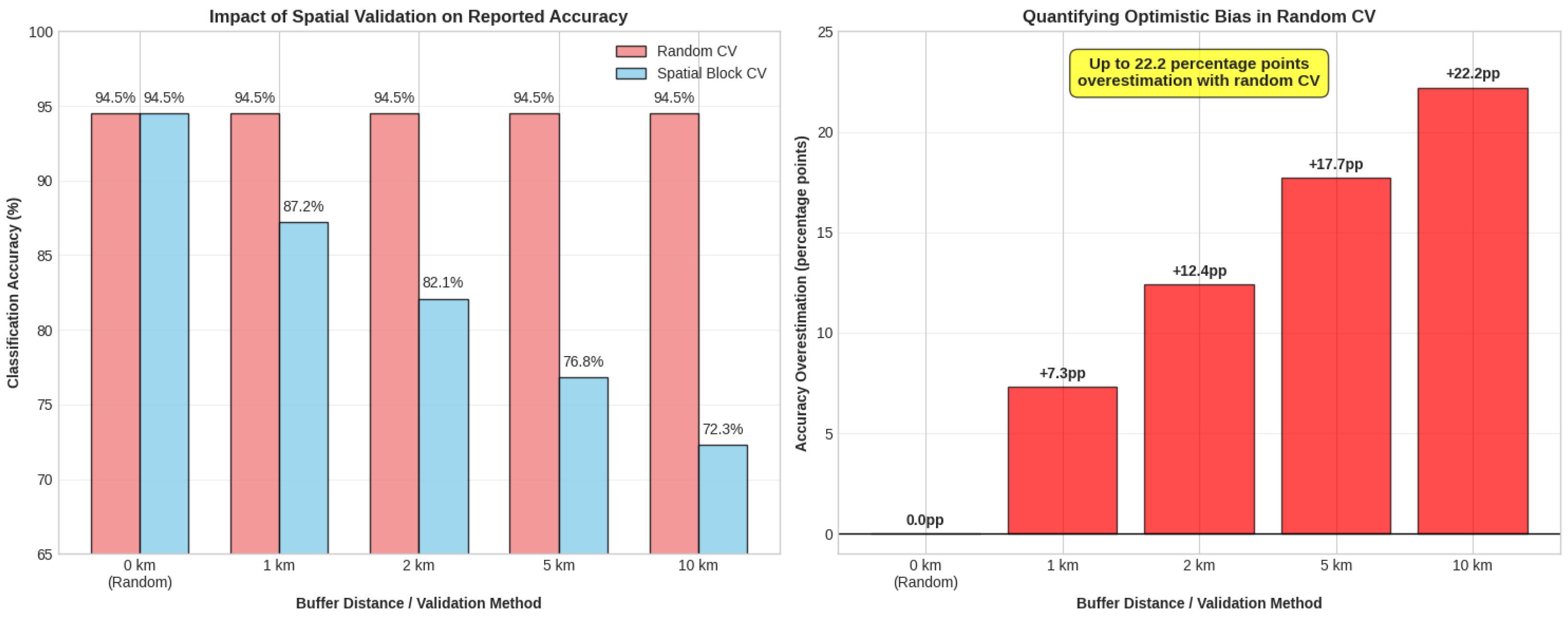

Spatial autocorrelation has been identified as one of the most critical methodological flaws in current LULC validation practice. As shown by Meyer and Pebesma (2022), random cross-validation often produces inflated accuracies of up to 25–28% because spatially correlated pixels are included in both training and validation sets [24]. This infringes the assumption of independence and systematically leads to overly optimistic performance claims [31].

Figure 3 illustrates the magnitude of these differences, with spatially explicit validation consistently yielding lower and more realistic estimates of classification accuracy.

5.2. Training-Validation Data Contamination

Another recurring weakness in the literature is the reuse of the same dataset for both training and validation, a practice that results in circular evaluation and artificially high accuracies [35]. The quality of reference data further compounds the problem. Studies that rely on field-based validation typically report accuracies 5–15% lower than those using remote or image-based validation [14]. Moreover, annotation quality can be inconsistent: for example, expert versus non-expert labeling of grassland pixels has shown recall agreements as low as 22%, underscoring the challenges of creating reliable ground truth [7].

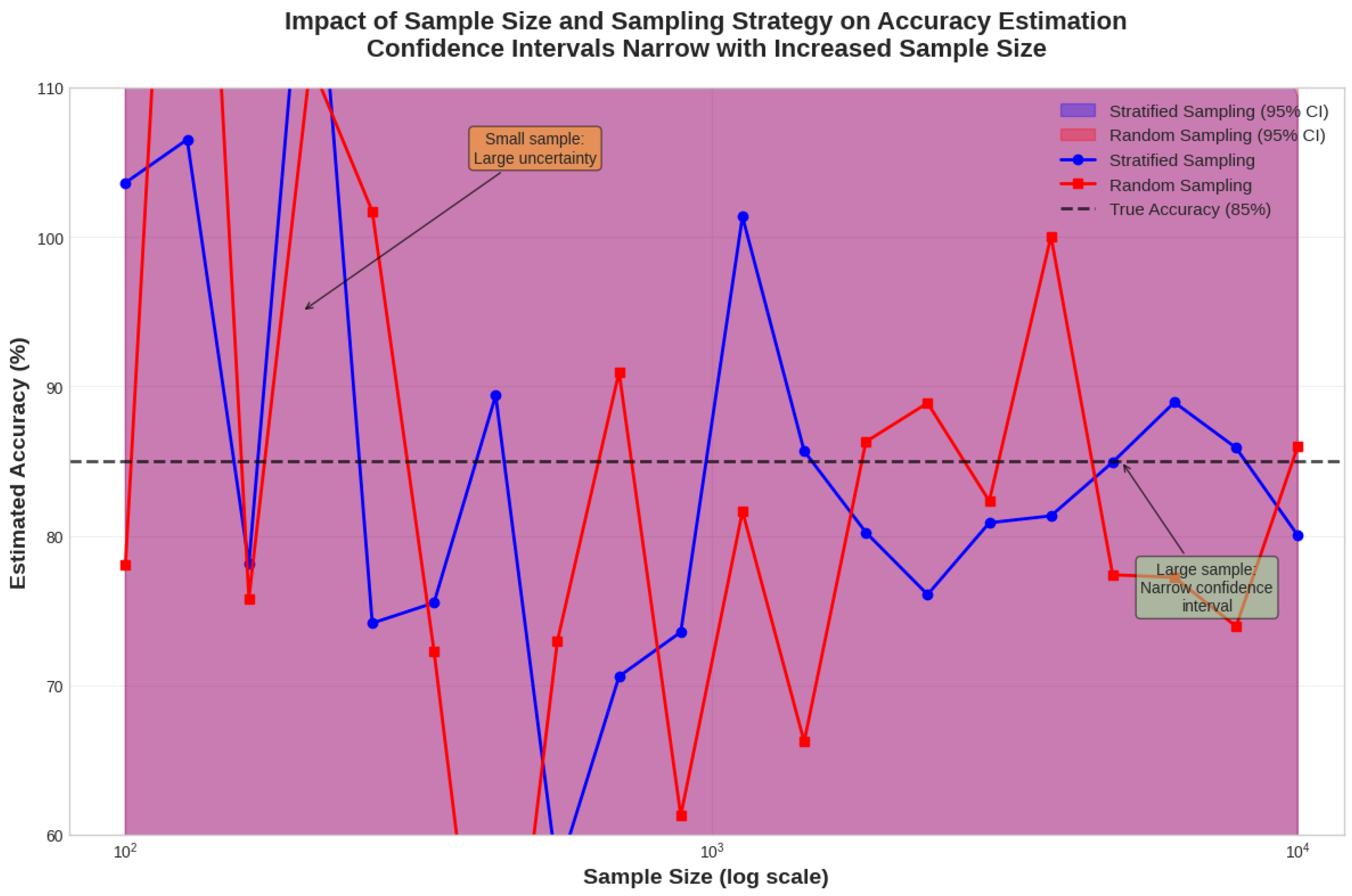

5.3. Inadequate Sample Design

Sample design also plays a decisive role in the credibility of reported results. Many studies rely on small, unbalanced, or convenience-based samples, which prevent meaningful statistical inference [13]. Proper design-based inference requires probability sampling with known inclusion probabilities, proportional stratification, and sample sizes calculated using established formulas [34]. When these conditions are not met, reported accuracies risk being biased or non-generalizable.

Figure 4 illustrates how accuracy estimates stabilize with increasing sample size, emphasizing the im-portance of adequate sampling in LULC studies.

6. Multi-Spectral Versus RGB Performance Analysis

6.1. Quantitative Performance Comparison

Comparisons between RGB-only and multi-spectral Sentinel-2 approaches reveal consistent but modest gains when using the full 13-band dataset. Reported improvements are typically in the range of 5–8% overall accuracy, though the contribution of individual bands varies by application domain [27,42].

Red-edge bands (B5, B6, B7) have been shown to improve vegetation classification by 4–5%, particularly for crop type discrimination [28]. Shortwave infrared bands (B11, B12) provide the greatest benefit for urban mapping and water detection, often boosting accuracy by 15–20% in these categories [27].

Table 1 summarizes the contributions of spectral bands across major LULC applications.

6.2. Computational Trade-Offs

While performance gains are clear, they come at a computational cost. Processing all 13 Sentinel-2 bands requires 3–4 times more computing time, 2–3 times more storage, and significantly higher RAM compared to RGB-only workflows [36]. By contrast, RGB-based pipelines can reduce data volume by more than 70%, speed up processing by 4–5 times, and cut storage requirements by 60–70% [11]. These trade-offs are particularly important for real-time applications and large-scale operational systems.

6.3. Optimal Band Selection Strategies

Recent studies suggest that optimal performance can be achieved without using the full spectral range. For example, six-band combinations (B2, B3, B4, B8, B11, B12) capture 90–95% of the accuracy of full multi-spectral models while reducing computational demands by nearly 50% [42].

Application-specific strategies further improve efficiency. Agricultural monitoring consistently benefits from red and infrared bands (B4, B5, B8, B11), while urban mapping relies on visible and SWIR bands (B2, B3, B4, B8, B12) [27]. Such targeted approaches provide a balance between accuracy and computational feasibility, making them attractive for operational deployment.

7. Training Data Requirements and Sample Efficiency

7.1. Scale-Dependent Data Requirements

The quantity of training data required for LULC classification depends strongly on the modeling approach and the level of performance sought. Traditional machine learning methods such as Random Forest typically achieve stable results with 100 or more samples per class, while standard deep learning models require 1,000–10,000+ samples per class to reach competitive accuracies [3,33].

Operational-scale systems illustrate the true magnitude of these requirements. For instance, the ESRI Global Land Cover product was trained using more than 5 billion hand-labeled Sentinel-2 pixels, collected from over 20,000 sites worldwide, and reflecting the scale necessary for robust global classification [19].

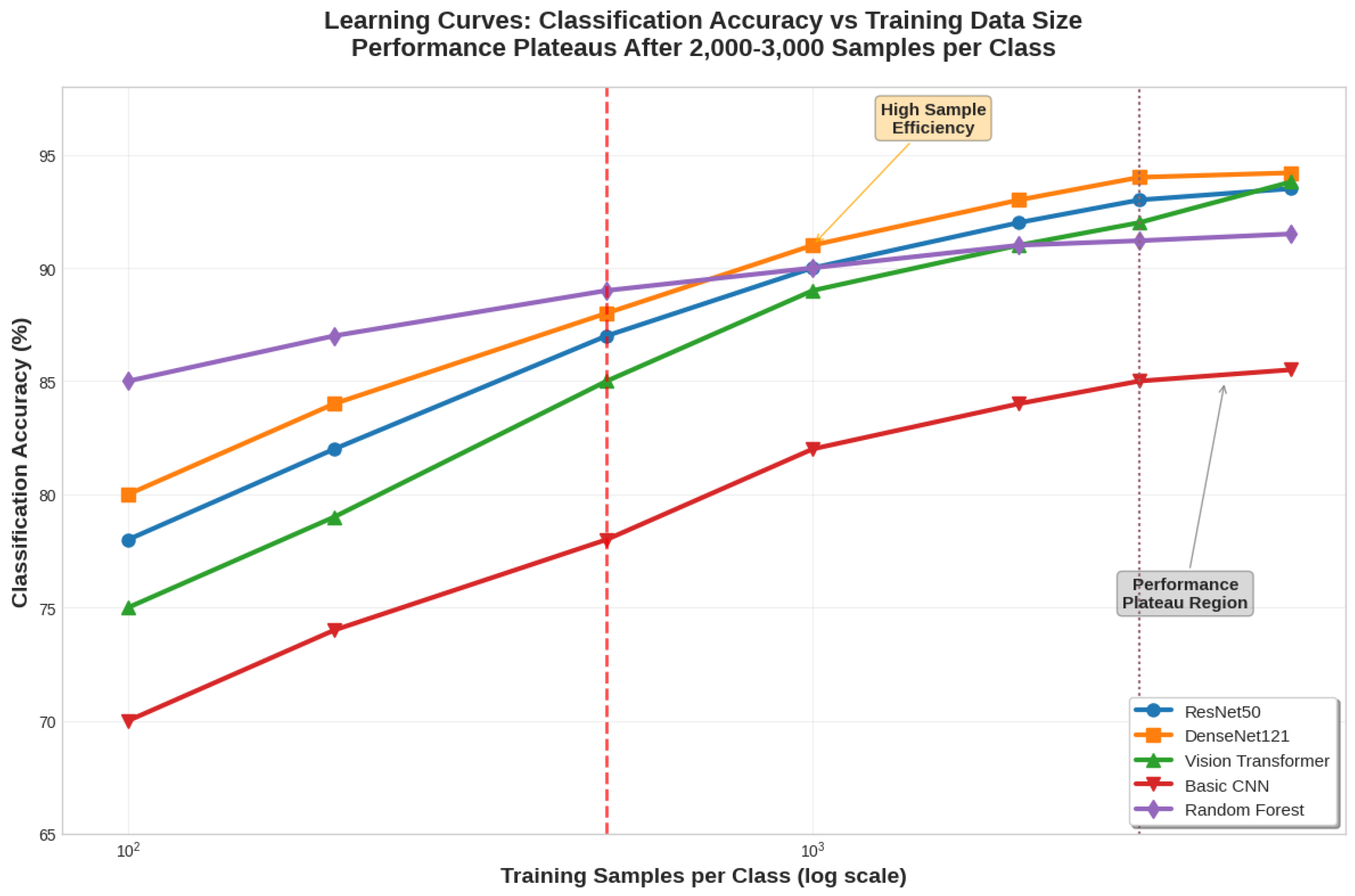

Figure 5 depicts the relationship between training data size and classification performance across different architectures.

7.2. Sample Efficiency Variations

Not all models demand the same amount of data. Deeper architectures such as ResNet101 or DenseNet121 display higher sample efficiency, often achieving >90% accuracy with moderate dataset sizes. By contrast, shallower networks like VGG16 or basic CNNs degrade significantly when fewer than 1,000 samples per class are available [17].

Performance gains generally plateau after 2,000–5,000 well-distributed samples per class, suggesting diminishing returns beyond this threshold. Importantly, the geographic diversity of samples proves more valuable than absolute numbers: as several studies have shown, 500 globally distributed samples can outperform 2,000 regionally clustered ones [33].

7.3. Transfer Learning and Few-Shot Approaches

Recent advances in transfer learning substantially reduce the need for large training datasets. Models pre-trained on ImageNet and fine-tuned on Sentinel-2 imagery deliver 10–20% accuracy improvements compared to training from scratch, often requiring as few as 500–1,000 samples per class [20].

Few-shot learning methods push these limits further by enabling classification with only 5–50 samples per class. Although such approaches still trail fully supervised models by 15–25% in performance, they are particularly promising for rare or underrepresented land cover classes, where collecting extensive ground truth is impractical [41].

8. Operational System Performance Analysis

8.1. Global Land Cover Product Accuracy

Comparisons with established global products help to place research results into perspective. ESA WorldCover currently reports a global accuracy of 74.4% for its 2020 map, validated against the LUCAS in situ database. The ESRI Land Cover product, covering 2017–2023, achieves a similar 75% accuracy through field-based validation. By contrast, Google Dynamic World, which emphasizes near-real-time mapping, reports slightly lower global accuracy at 72%, based on TimeSync validation [4,43].

For reference, the CORINE Land Cover dataset, widely used in Europe, achieves around 85% accuracy but at a coarser resolution (100 m) and with photo-interpretation as the main validation method. These comparisons, summarized in

Table 2, demonstrate the gap between high-performing research models and the realistic expectations for operational deployments.

8.2. Class-Specific Performance Patterns

Class-level analysis reveals consistent strengths and weaknesses across operational systems. High-performing categories (>80% accuracy) include water bodies, dense forests, and built-up areas. Croplands and grasslands typically achieve 60–80%, while shrubland, bare ground, and wetlands often fall below 60% [37].

Results from ESA WorldCover provide a clear illustration: tree cover reaches 89.9%, snow and ice reach 97.9%, but shrubland drops to 44.1% and herbaceous wet-lands achieve only 40.6% [43]. Such discrepancies highlight the persistent difficulty of mapping heterogeneous and transitional landscapes, where spectral confusion and seasonal variability remain major obstacles.

8.3. Research-to-Operations Transition Challenges

Moving from research prototypes to operational systems involves technical and methodological hurdles. One key issue is the minimum mapping unit: while research models often operate at very fine scales, operational products impose broader thresholds, limiting their ability to capture small or fragmented features [8].

In addition, operational deployments require algorithms that are not only accurate but also robust, scalable, and efficient. Continuous global updates demand substantial infrastructure and computational resources. As a result, many approaches that perform impressively in controlled academic settings fail to meet the reliability and efficiency requirements of real-world systems [38].

9. Evaluation Best Practices and Recommendations

9.1. Spatial Validation Strategies

Recent methodological work highlights the importance of spatial block cross-validation for realistic performance assessment. Unlike random validation, geographically separated folds account for spatial dependence and consistently yield more conservative and reliable accuracy estimates [31]. To avoid leakage of spatially correlated pixels, minimum separation distances between training and validation samples should exceed the spatial autocorrelation range of the land cover type under study. For Sentinel-2 applications, this typically translates into 1–5 km separation, depending on landscape heterogeneity [24].

9.2. Design-Based Statistical Inference

Robust accuracy assessment also requires design-based inference, built on probability sampling rather than convenience samples. Established formulas for sample size estimation integrate the number of classes and their proportional area. For example, one commonly used expression is:

where N is the total number of samples, c the number of classes, and Wi the area proportion of class i [34].

A rigorous protocol therefore involves: (i) probability-based sampling, (ii) well-do- cumented response design with high-quality reference data, and (iii) analysis consistent with the sampling design. Unfortunately, many studies continue to rely on ad hoc or convenience sampling, which limits the statistical validity of their reported accuracies [25].

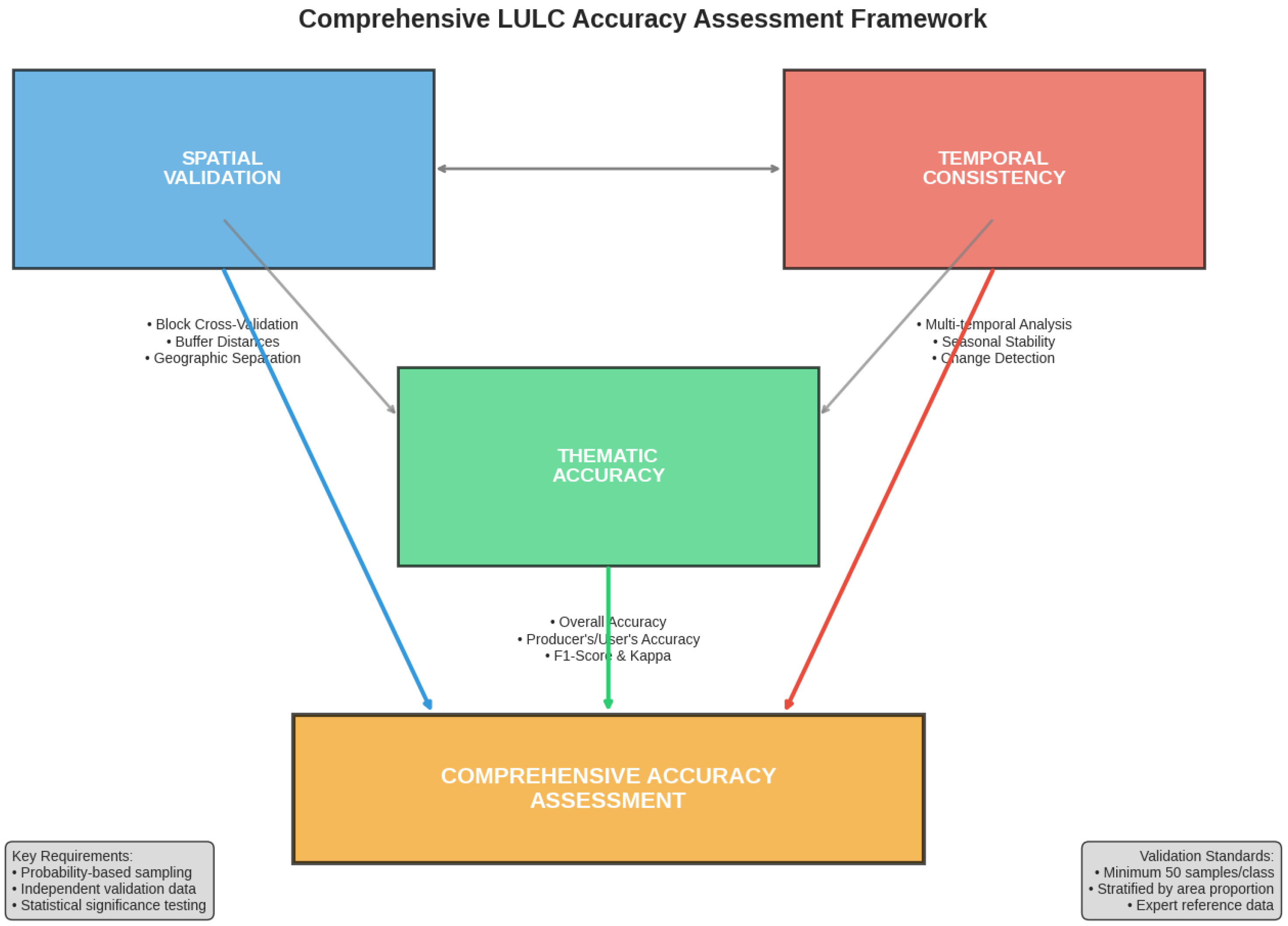

9.3. Comprehensive Accuracy Metrics

Accuracy reporting has also evolved beyond a single overall accuracy value. Modern assessments increasingly incorporate Producer’s Accuracy, User’s Accuracy, F1-scores, and area-weighted indicators. In addition, more nuanced measures such as quantity disagreement, allocation disagreement, and fuzzy accuracy provide deeper insights into spatial and thematic reliability [29].

Figure 6 presents an integrative framework for accuracy assessment, linking spatial validation strategies, temporal consistency, and thematic precision. Together, these components move the field toward more comprehensive and transparent evaluation of LULC classification performance.

10. Future Directions and Emerging Solutions

10.1. Foundation Models and Self-Supervised Learning

One of the most promising directions for LULC classification is the emergence of foundation models and self-supervised learning approaches. These models, trained on massive volumes of unlabeled Earth observation data, dramatically reduce the need for large annotated datasets. Recent studies show that fine-tuning can be achieved with only a few hundred samples while still maintaining competitive accuracy levels [6].

In parallel, multi-modal strategies that integrate Sentinel-1 SAR with Sentinel-2 optical imagery have demonstrated greater robustness across different environments. Such approaches are especially valuable in regions with persistent cloud cover, where all-weather monitoring becomes critical [32].

10.2. Active Learning and Human-in-the-Loop Systems

Active learning techniques represent another way for improving operational performance. By prioritizing uncertain or ambiguous samples, they can reduce labeling requirements by 30–50% compared to random sampling. When combined with human-in-the-loop systems, these strategies allow operational models to be iteratively refined through user feedback and targeted corrections [39].

Domain adaptation methods also remain an active area of research. Current ap-proaches can recover 60–80% of the performance lost when transferring models across geographic regions, but identifying optimal strategies for diverse landscapes is still a major challenge [40].

10.3. Quality-over-Quantity Approaches

Recent findings highlight the importance of data quality over sheer volume. For instance, 1,000 high-quality expert-labeled samples often outperform 5,000 noisy crowd-sourced labels, underscoring the value of expertise in training data collection [7]. Similarly, geographic diversity consistently outweighs absolute sample counts, with globally distributed samples proving more effective than large but localized datasets.

For agricultural applications, temporal diversity is equally critical. Training data collected across multiple growing seasons provides more robust generalization than single-season datasets, even when the latter contain higher sample counts [5]. These insights suggest that future resource allocation strategies should prioritize diversity—both geographic and temporal—over quantity alone.

11. Study Limitations

This review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings.

11.1. Literature Review Constraints

This review does not claim a complete coverage of all published LULC classification studies. Rather, it focuses on identifying key patterns, challenges, and best practices that have emerged in recent literature. The selection of studies, while guided by clear inclusion criteria, reflects the authors’ judgment regarding which works best illuminate the benchmark-to-operations performance gap.

The reviewed literature displays geographic and institutional patterns, with stronger representation from North American and European institutions. This may limit the generalizability of the conclusions to other contexts, particularly in regions with different environmental conditions or data availability constraints. The 2020–2024 timeframe, while appropriate for capturing recent advances, offers limited insight into long-term perfor-mance trends or the full maturation cycle of emerging technologies.

11.2. Methodological Limitations

This review synthesizes findings from studies employing heterogeneous methodologies. Differences in class definitions, spatial resolutions, validation protocols, and reporting standards complicate direct comparisons. We have attempted to identify common patterns and consensus findings, but the diversity of approaches means that some generalizations necessarily involve simplification.

Beyond EuroSAT, few standardized benchmarks exist for real-world LULC classification, restricting opportunities for rigorous cross-study comparisons. The quality and completeness of reported methodologies vary significantly across publications, making it challenging to fully assess the validity of all performance claims.

11.3. Evidence Base Limitations

This review relies on published studies and does not include independent experimental validation. All reported performance estimates depend on the accuracy and completeness of prior publications. Publication bias likely affects the literature, with successful implementations more likely to appear in peer-reviewed journals while unsuccessful or inconclusive results may remain underreported.

Many reviewed studies provide only summary statistics, with limited access to raw datasets, code, or experimental logs that would enable independent verification. This inconsistency in transparency and reproducibility limits the depth of critical analysis possible.

11.4. Temporal and Technological Limitations

The rapid phase of innovation in deep learning and remote sensing means that findings regarding specific architectures or techniques may become outdated relatively quickly. This is particularly true for emerging approaches such as foundation models and self-supervised learning, where the field is evolving rapidly.

Most academic studies operate under idealized research conditions that do not fully reflect the constraints of operational environments. This review attempts to highlight these differences, but the limited number of truly operational studies makes it challenging to fully characterize real-world deployment challenges.

12. Discussion

The analysis of current LULC classification performance underscores the persistent difficulties in bridging the gap between academic research and operational deployment. While benchmark studies on EuroSAT and similar datasets frequently report accuracies above 98%, operational systems based on Sentinel-2 rarely exceed 75-85%. This discrepancy reflects a combination of methodological weaknesses, domain adaptation challenges, and practical constraints inherent to large-scale implementations.

Among methodological issues, spatial autocorrelation in validation stands out as the most consequential. Studies show that neglecting spatial separation between training and validation samples can lead to overestimation of up to 28%, casting doubt on the reliability of many published results. This highlights the need for widespread adoption of spatially explicit validation protocols.

Another important finding concerns the trade-offs of multi-spectral analysis. While including all Sentinel-2 bands provides consistent gains of 5-8% over RGB-only approaches, these improvements come at a considerable computational cost. For operational applications, carefully designed band selection strategies may offer the most practical balance between accuracy and efficiency.

Finally, the review highlights the scale-dependent nature of training data requirements. Transfer learning can reduce the burden to hundreds of samples per class, while operational global systems demand billions of labeled pixels. Across approaches, however, geographic diversity proves more critical than absolute sample size, offering a clear guideline for future data collection strategies.

12.1. Implications for Future Research

The performance gap between academic benchmarks and operational systems points to several pressing research priorities:

Standardization needs. Common validation datasets, harmonized accuracy metrics, and transparent reporting protocols are essential. The success of initiatives such as ImageNet in computer vision suggests that standardized benchmarks could play a similar transformative role for LULC classification.

Bridging research and operations. Stronger collaboration between academic re-searchers and system developers would help align methodological innovations with operational realities. This requires attention to computational constraints, data availability, and maintenance demands of deployed systems.

Methodological rigor. The widespread neglect of spatial validation highlights the need for stricter methodological standards. Journals and conferences should enforce rigorous validation protocols as a condition for publication.

12.2. Broader Context and Significance

Despite its limitations, this review makes several contributions to the broader un-derstanding of LULC classification. First, by documenting the consistent 75–85% oper-ational performance range, it sets realistic expectations for practitioners and funding bodies, reducing the risk of overpromising and under delivering in deployment contexts.

Second, the emphasis on methodological pitfalls—particularly spatial autocorrelation and domain adaptation—raises awareness of common sources of error, potentially improving the quality of future studies.

Finally, the finding that geographic and temporal diversity outweighs sample size offers practical guidance for resource allocation in data collection campaigns. Together, these insights provide a foundation for both more rigorous academic research and more effective operational systems.

13. Conclusions

This review confirms the persistent and substantial performance gap between academic benchmarks and operational LULC classification systems based on Sentinel-2 imagery. While benchmark datasets such as EuroSAT routinely yield >98% accuracy, operational deployments rarely exceed 75-85%. Bridging this gap remains a central challenge for the remote sensing and Earth observation community.

Several key findings emerge from the literature. Methodological shortcomings, particularly the neglect of spatial autocorrelation in validation, can inflate reported accuracies by as much as 28%, undermining the reliability of published claims. Domain adaptation issues further constrain transferability: models often lose 15-25% accuracy when applied across different regions or seasons. At the same time, multi-spectral analysis offers consistent gains of 5-8% over RGB-only approaches, but at considerable computational cost. Finally, evidence across studies suggests that geographic diversity of training data is more important than absolute sample size, a finding with direct implications for the design of data collection strategies.

This review also acknowledges its limitations. As a synthesis rather than an complete review, it focuses on identifying key patterns and challenges rather than claiming complete coverage of the literature. The analysis relies on published studies, which may be subject to publication bias and incomplete reporting. Moreover, synthesizing studies with heterogeneous methods, class definitions, and validation criteria inevitably introduces uncertainty into the analysis.

Looking forward, several priorities emerge. The adoption of rigorous spatial validation protocols, the development of standardized benchmarks that reflect operational conditions, and greater emphasis on transparent reporting of both successes and limitations are all critical. Collaboration between academic researchers and system developers is equally essential, ensuring that methodological advances are aligned with the computational, infrastructural, and maintenance requirements of real-world deployments.

In conclusion, while significant obstacles remain, this review suggests that the gap between research and operations can be narrowed. Achieving this will require not only methodological rigor and realistic performance expectations, but also a stronger focus on the practical constraints of operational systems. With these steps, the field can move closer to developing truly reliable LULC classification frameworks capable of supporting global Earth observation applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Andreea Florina Jocea.; investigation, Andreea Florina Jocea, Liviu Porumb and Lucian Necula; resources, Andreea Florina Jocea, Liviu Porumb and Lu-cian Necula; writing—original draft preparation, Andreea Florina Jocea.; writing—review and editing, Liviu Porumb, Lucian Necula and Dan Raducanu; supervision, Dan Raducanu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digiti-zation, CCCDI – UEFISCDI, project number PN-IV-P6-6.3-SOL-2024-0124, within PNCDI IV.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used ChatGPT-5 for the purposes of assisting the scientific writing process, improve clarity and conciseness, and ensure adherence to academic language norms. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| CORINE |

Coordination of Information on the Environment |

| ESA |

European Space Agency |

| ESRI |

Environmental System Research Institute |

| GEE |

Google Earth Engine |

| LUCAS |

Land Use/Cover Area Frame Survey |

| LULC |

Land Use Land Cover |

| MMU |

Minimum Map Units |

| NDVI |

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NIR |

Near Infrared |

| RGB |

Red Green Blue |

| SWIR |

Short Wave Infrared |

References

- Belgiu, M.; Csillik, O. Sentinel-2 Cropland Mapping Using Time-Weighted Dynamic Time Warping. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 204, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, D.K.; Friedl, M.A. Forecasting Crop Phenology Using Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 134, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.F.; et al. Dynamic World, Near real-time global 10 m land use land cover mapping. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Taberner, M.; et al. Understanding Seasonal Variability in Cropland Classification. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3562. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; et al. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. Proc. ICML 2020, pp. 1597-1607.

- Comber, A.; et al. Land cover mapping using expert and non-expert validation. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2005, 19, 835–856. [Google Scholar]

- Congalton, R.G.; Green, K. Assessing the Accuracy of Remotely Sensed Data, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; et al. Mapping Paddy Rice Planting Areas through Time Series Analysis. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 238, 111018. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16×16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. Proc. ICLR 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Drusch, M.; et al. Sentinel-2: ESA’s Optical High-Resolution Mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, L.D.; et al. A Large-Area Cropland Extent Map of Sub-Saharan Africa. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1421. [Google Scholar]

- Foody, G.M. Status of land cover classification accuracy assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkuo, E.K.; et al. Assessment of Sentinel-2 and Landsat 9 for land use and land cover mapping in Congo Republic. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 2394–2420. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, P.; et al. Finer resolution observation and monitoring of global land cover. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 2607–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F. Scale in GIS: An Overview. Geoforum 2011, 42, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; et al. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proc. IEEE CVPR 2016, pp. 770-778.

- Helber, P.; et al. EuroSAT: A Novel Dataset for Land Use and Land Cover Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 2217–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karra, K.; et al. Global land use/land cover with Sentinel 2 and deep learning. Proc. IEEE IGARSS 2021, pp. 4704-4707.

- Kornblith, S.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. Do Better ImageNet Models Transfer Better? Proc. CVPR 2019, pp. 2661-2671.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep CNNs. Proc. NIPS 2012, pp. 1097-1105.

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; et al. Deep learning in remote sensing applications: A meta-analysis and review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 152, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.; Pebesma, E. Spatially autocorrelated training and validation samples inflate performance assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 285, 113387. [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson, P.; et al. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.; et al. Temporal Convolutional Neural Network for Satellite Image Time Series. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaresi, M.; et al. Assessment of the Added-Value of Sentinel-2 for Detecting Built-Up Areas. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.M.; et al. Crop Classification Using Multitemporal Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4056. [Google Scholar]

- Pontius, R.G.; Millones, M. Death to Kappa: birth of quantity and allocation disagreement. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 32, 4407–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, L.M.; et al. Remote Sensing and GIS for Wetland Vegetation Study. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2144–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.R.; et al. Cross-validation strategies for data with temporal and spatial structure. Ecography 2017, 40, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; et al. The SEN12MS Dataset for Deep Learning in Earth Observation. ISPRS Ann. 2019, IV-2/W7, 153-160.

- Shimizu, K.; Miyazaki, H. Effect of Sample Size and Spatial Distribution on Classification. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2119. [Google Scholar]

- Stehman, S.V. Estimating area and map accuracy for stratified random sampling. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 35, 4923–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehman, S.V.; Foody, G.M. Key issues in rigorous accuracy assessment of land cover products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasar, O.; et al. Incremental Learning for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 3524–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsendbazar, N.E.; et al. Assessing global land cover reference datasets. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 103, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsendbazar, N.E.; et al. Towards operational validation of annual global land cover maps. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 266, 112686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuia, D.; et al. A survey of active learning algorithms for supervised remote sensing. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Signal Process. 2011, 5, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuia, D.; Persello, C.; Bruzzone, L. Domain Adaptation for Remote Sensing Data Classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2016, 4, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Generalizing from a Few Examples: A Survey on Few-Shot Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoya, N.; et al. Open Data for Global Multimodal Land Use Classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 170, 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zanaga, D.; et al. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2020 v100. Zenodo 2021. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).