Submitted:

16 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

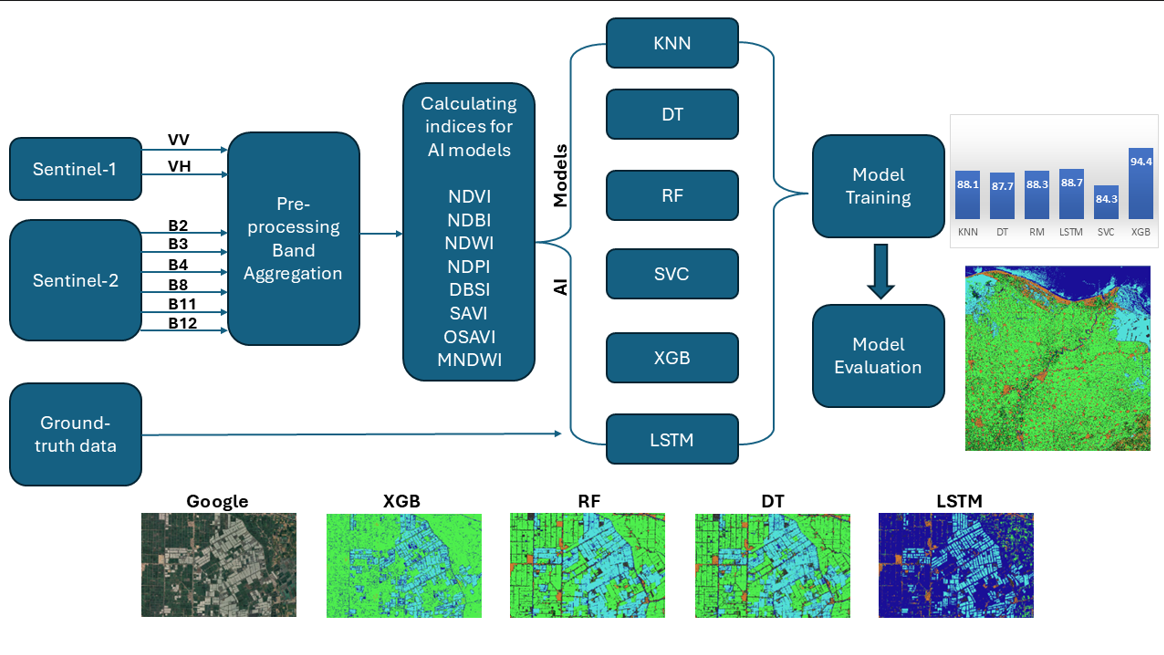

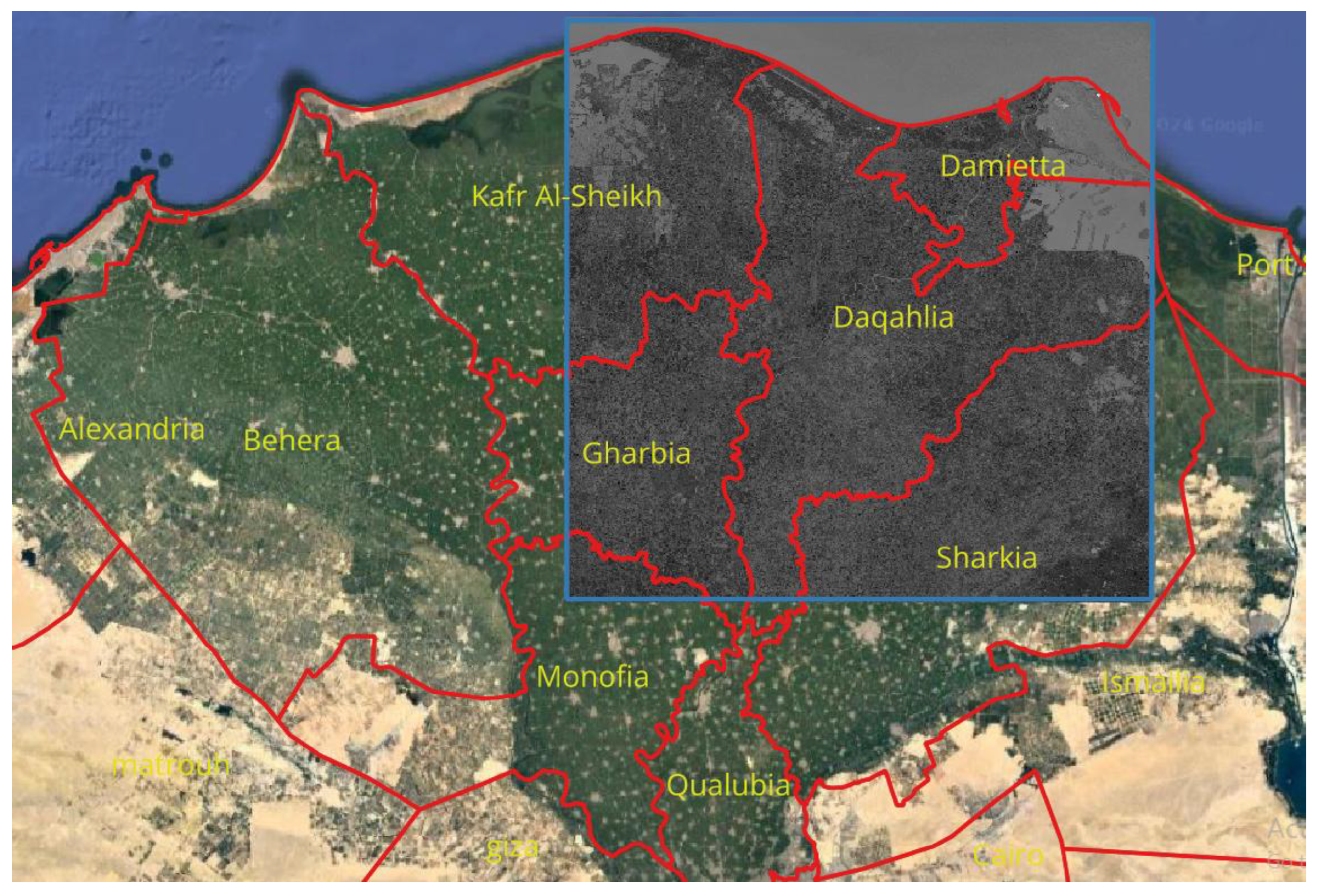

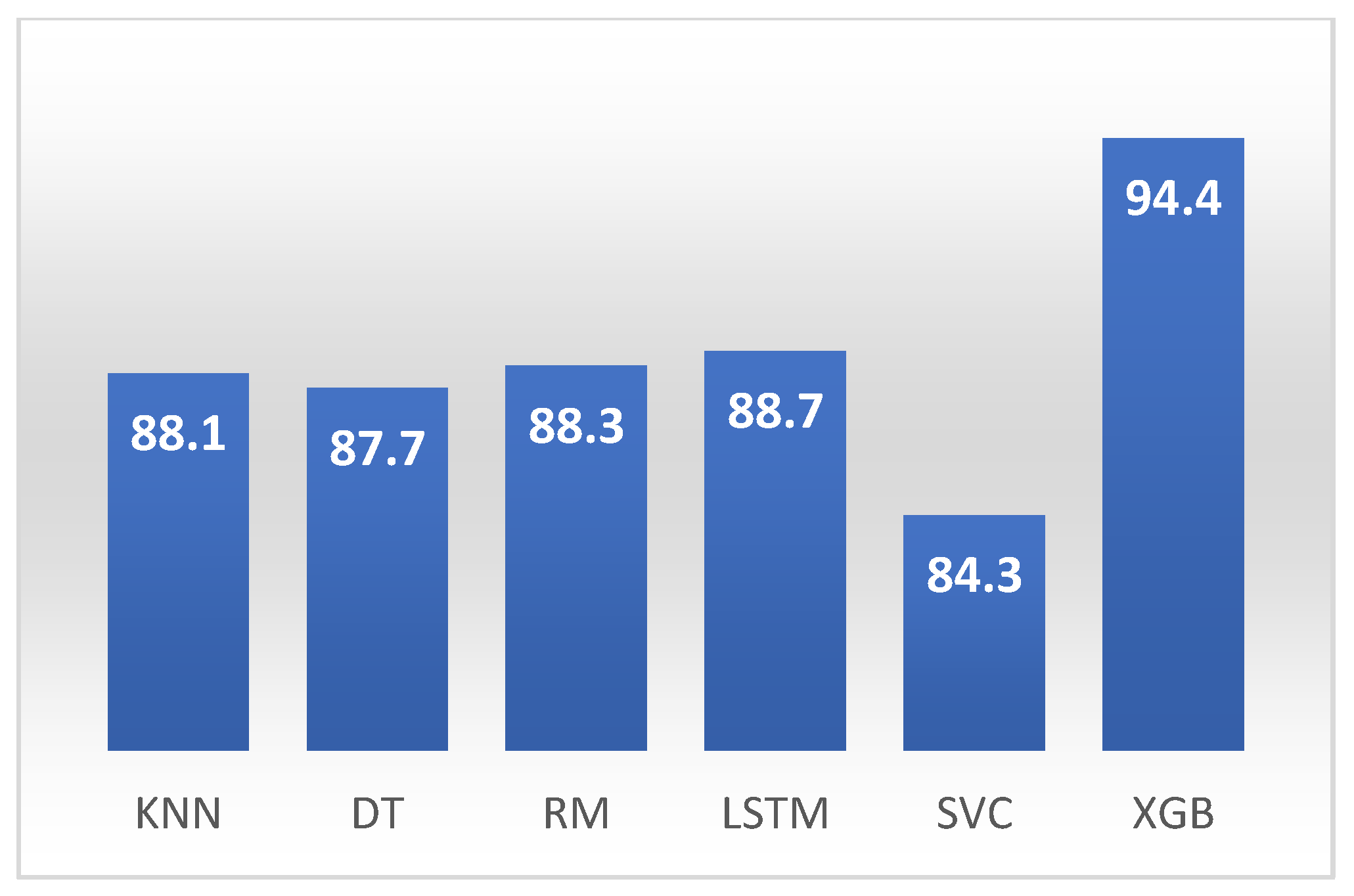

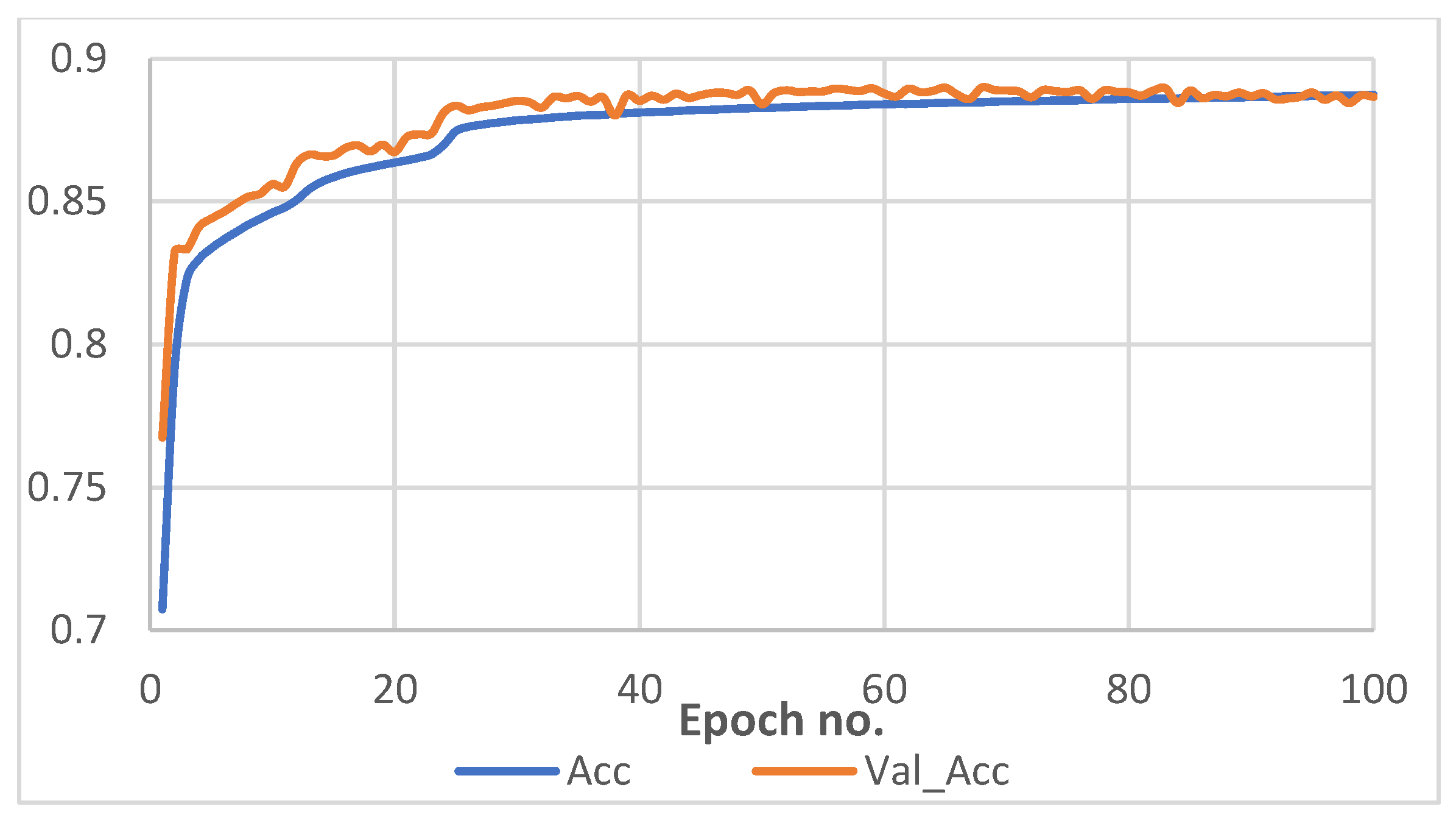

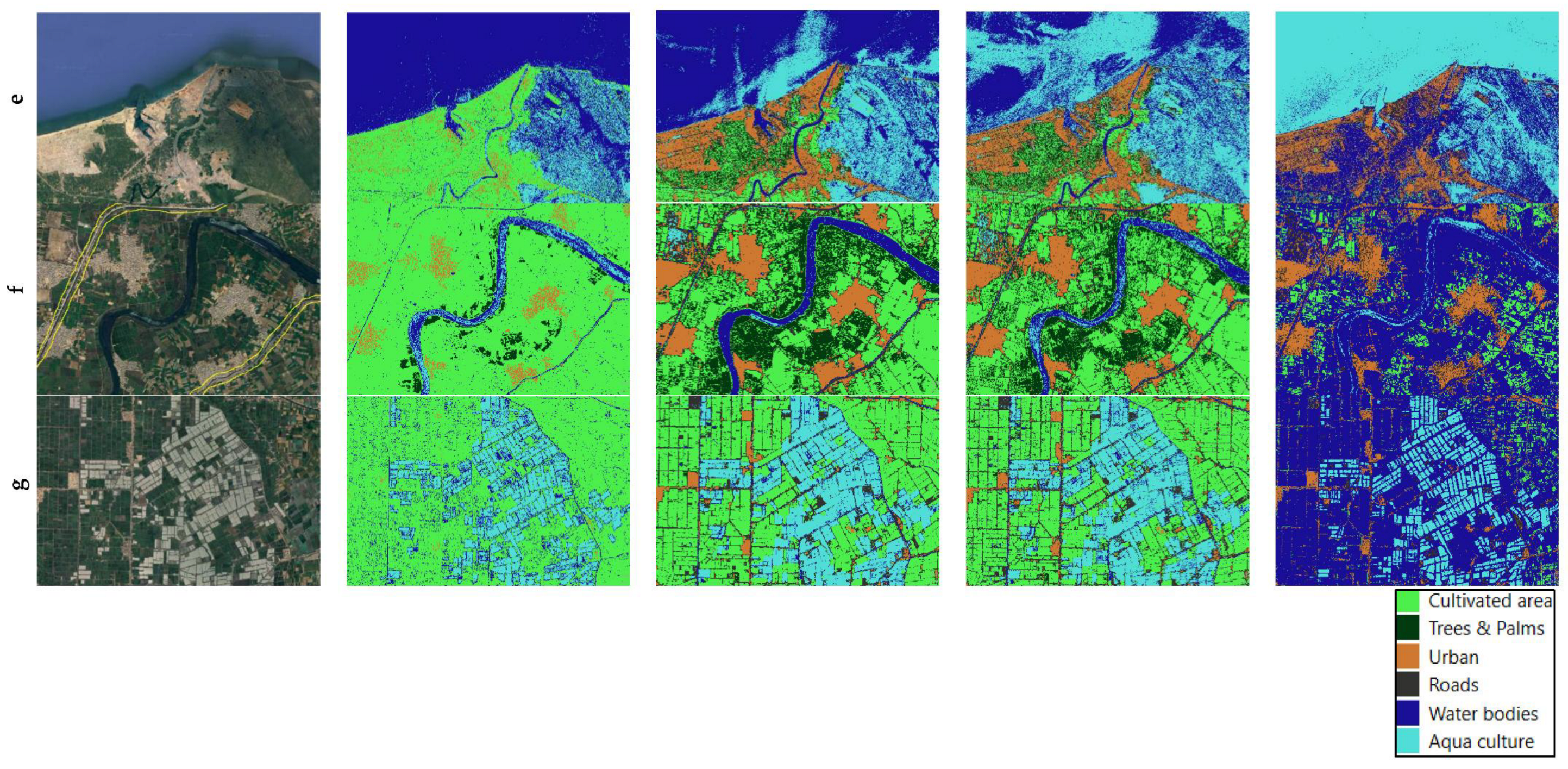

This study investigated Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) classification east of the Nile Delta, Egypt, using Sentinel-2 bands, spectral indices, and Sentinel-1 data. The aim was to enhance agricultural planning and decision-making by providing timely and accurate information, addressing limitations of manual data collection. Several Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) models were trained and tested using distinct temporal datasets to ensure model independence. Ground truth annotations, validated against a reference Google satellite map, supported training and evaluation. XGBoost achieved the highest overall accuracy (94.4%), surpassing the Support Vector Classifier (84.3%), while Random Forest produced the most accurate map with independent data. Combining Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data improved accuracy by approximately 10%. Strong performance was observed across Recall, Precision, and F1-Score metrics, particularly for urban and aquaculture classes. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) technique effectively visualized data distribution, though complete class separation was not achieved. Despite their small size, road area predictions were reliable. This research highlights the potential of integrating multi-sensor data with advanced algorithms for improved LULC classification and emphasizes the need for enhanced ground truth data in future studies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

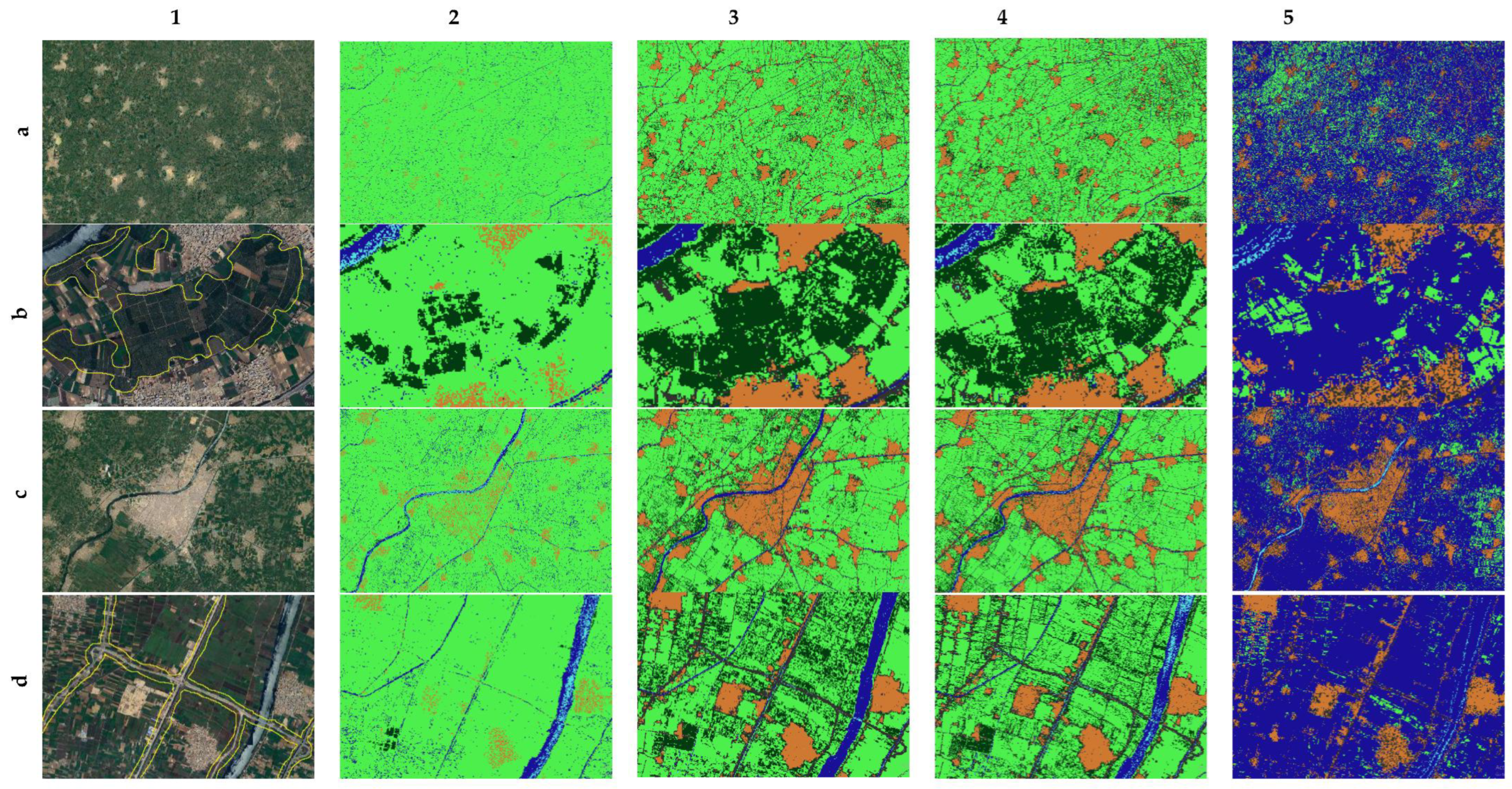

2.2. Data Annotation

2.3. Satellite Image Processing

2.3.1. Sentinel-1 Data

2.3.2. Sentinel-2 Data

2.4. Additional Features for Sentinel-1 and 2 Bands

2.5. Data Preprocessing

2.6. AI Models

| Spectral index | Formula | Characteristics / Definitions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) | NDVI= (NIR – R)/(NIR+R) | Measures vegetation health by comparing the reflectance of near-infrared (NIR) and red light, with NIR being reflected by vegetation and red light being absorbed by vegetation. | [75] |

| kernel Normalized difference vegetation index (kNDVI) | kNDVI = tanh((NIR – red/ 2σ)2)σ = 0.5 (NIR + red) | Enhances the performance of NDVI by incorporating automatic and pixel-wise adaptive stretching, ensuring that all aspects of the relationship between NIR and red bands are considered. | [76] |

| Normal Difference Built-up Index (NDBI) | NDBI = (SWIR – NIR) / (SWIR + NIR) | Asserts built-up areas by utilizing the NIR and short-wave infrared (SWIR) bands. | [77] |

| Dry Bare Soil Index (DBSI) | DBSI = ((SWIR – GREEN) / (SWIR + GREEN) ) – NDVI | Combines spectral bands including blue, red, NIR, and SWIR to capture variations in soil composition. | [78] |

| Normal Difference Water Index (NDWI) | NDWI = (GREEN - NIR) / (GREEN + NIR) | Identifies open water features in satellite imagery, distinguishing water bodies from soil and vegetation. | [79] |

| Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) | MNDWI = (GREEN − SWIR1)/(GREEN + SWIR1) | Effectively distinguishes between water bodies and urban areas in satellite images. | [80] |

| Normalized Difference Pond Index (NDPI) | NDPI = (SWIR1 - GREEN)/(SWIR1 + GREEN) | Exhibits enhanced discriminatory power for aquatic and wetland vegetation compared to NDVI, which is a general indicator of vegetation presence. | [81] |

| Shortwave infrared transformed reflectance (STR) | STR = (1 - SWIR)2 / 2 SWIR | Calculates reflectance for bare soils using SWIR bands. | [82] |

| Soil adjusted vegetation index (SAVI) | SAVI= 1.5(NIR – R) (NIR+R+0.5) | Reduces the influence of soil brightness by incorporating a correction factor for soil-brightness. | [83] |

| Optimized soil adjusted vegetation index (OSAVI) | OSAVI= 1.16(NIR – R)/ (NIR+R+0.16) | A modified version of SAVI that utilizes reflectance in the red and NIR spectrum. | [84] |

| Enhanced vegetation index (EVI) | EVI= 2.5(NIR – R)/(NIR+6 R – 7.5B+1) | Similar to NDVI, but EVI incorporates corrections for atmospheric influences and canopy background effects, thereby enhancing its sensitivity, notably in densely vegetated regions. | [85] |

| Automated Water Extraction Index (AWEI) | AWEIsh = BLUE + 2.5 × GREEN − 1.5 × (NIR + SWIR1) − 0.25 × SWIR2 | Contributes to enhanced land cover classification accuracy through its capacity to discriminate between binary water and non-water areas irrespective of environmental conditions. | [80] |

| Sentinel-1 | Sentinel-2 |

|---|---|

| July 04, 2021 | July 07, 2021 |

| July 10, 2021 | July 12, 2021 |

| July 16, 2021 | July 17, 2021 |

| July 28, 2021 | July 27, 2021 |

| August 03, 2021 | August 01, 2021 |

| August 09, 2021 | August 11, 2021 |

| August 15, 2021 | August 16, 2021 |

| August 21, 2021 | August 21, 2021 |

| August 27, 2021 | August 26, 2021 |

| August 07, 2023 | August 06, 2023 |

| Model | Search space |

|---|---|

| KNN | n_neighbors = [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] |

| DT | Criterion = {‘gini’, ‘entropy’}, max_depth = [10,13,15,18,20], min_sample_split = [50,80,100] |

| RF | n_estimators = [500,700,1000], max_depth = [10,13,15,18,20], min_sample_split = [50,80,100] |

| SVC | Kernels = ’RBF’, C = [10,20,30,40], Gamma = [0.1,0.5,1,5,10] |

| XGB | n_estimators = [500,700,1000], max_depth = [5,8,10,12,15], gamma = [0,0.001,0.005,0.1,0.5], learning_rate = [0.1,0.5,0.8,1,1.2,1.5,2], tree_method = ‘hist’ |

2.7. Models’ Evaluation

2.7. Experiment and Analysis

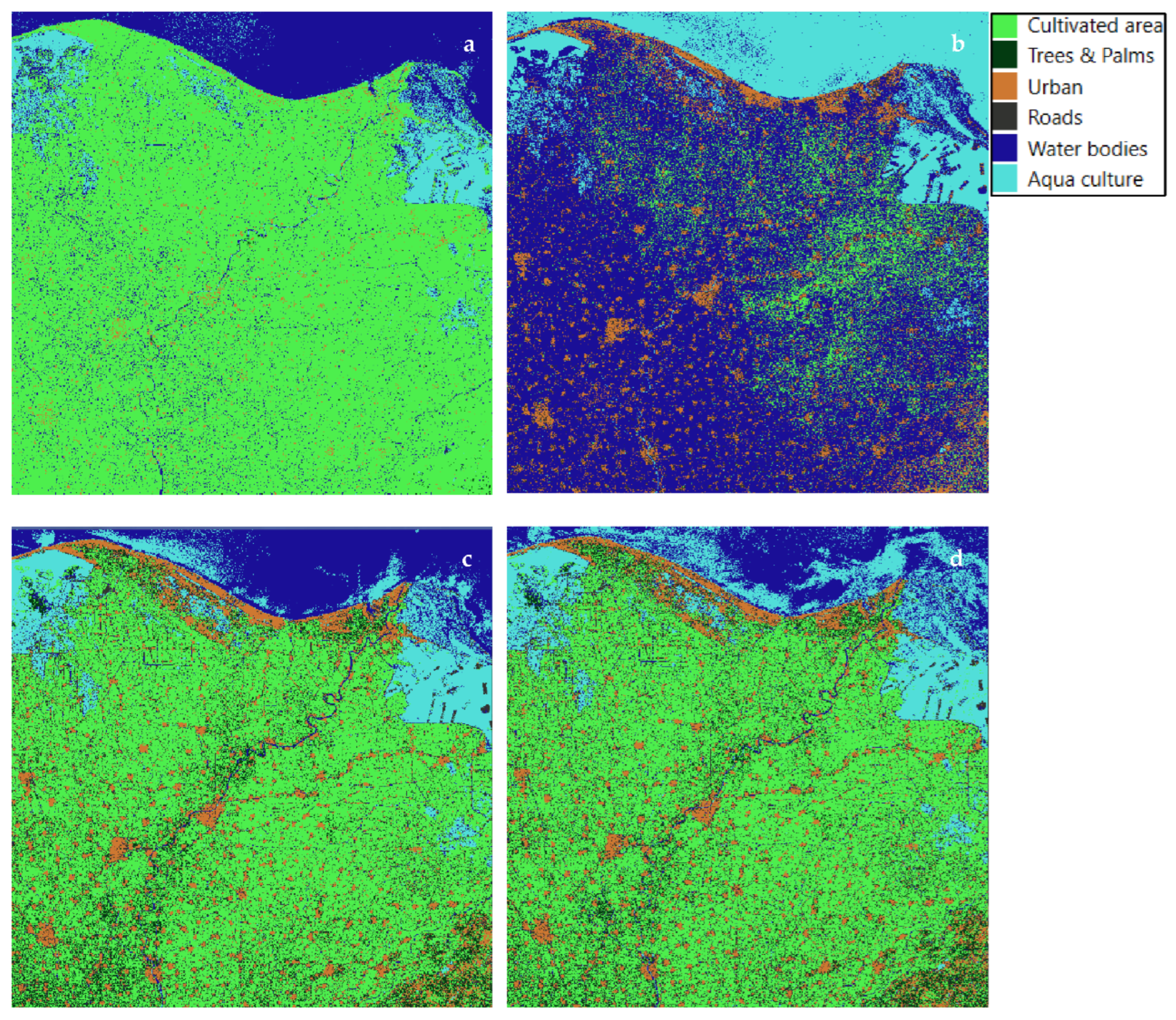

3. Results

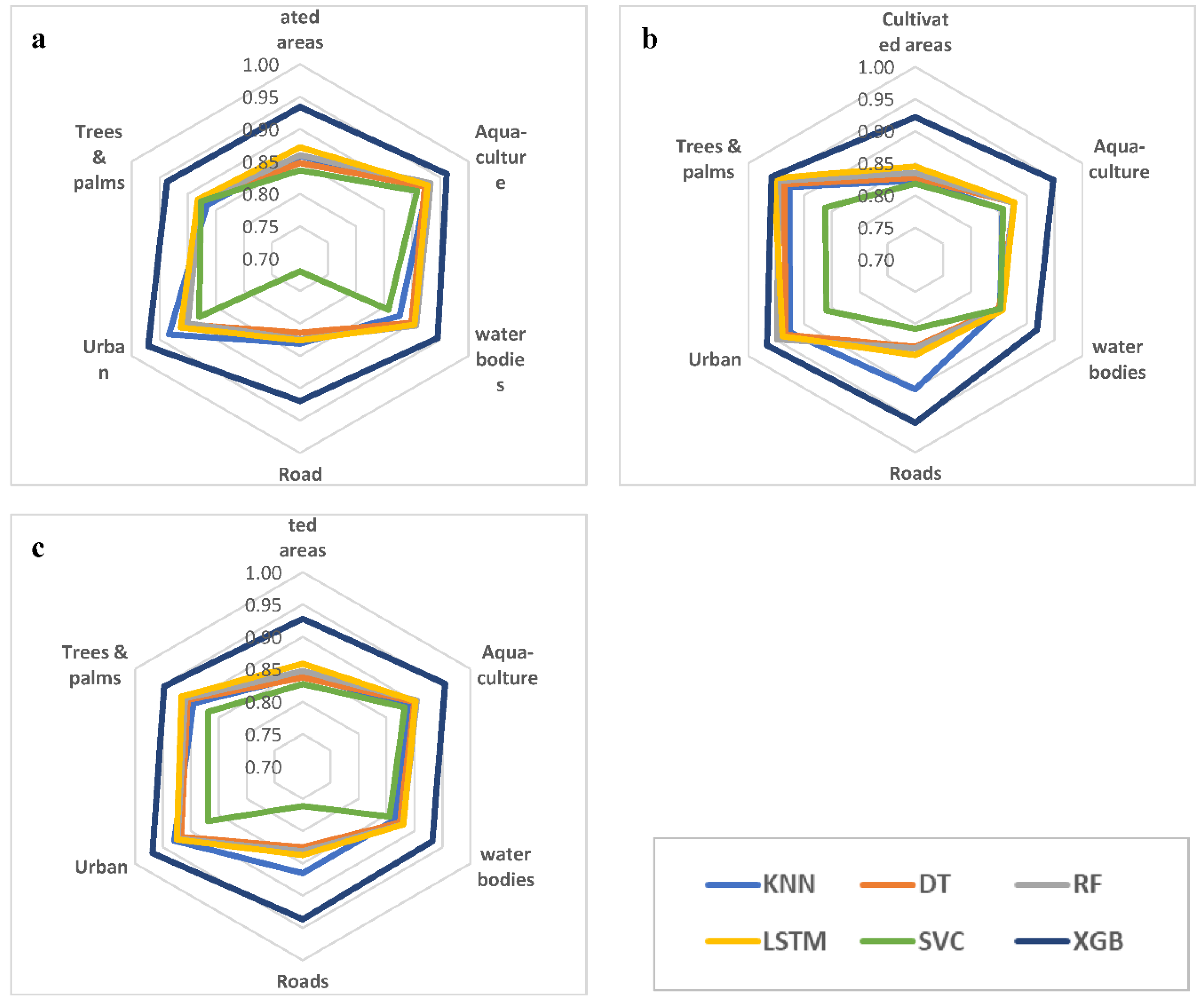

3.1. Models’ Performance

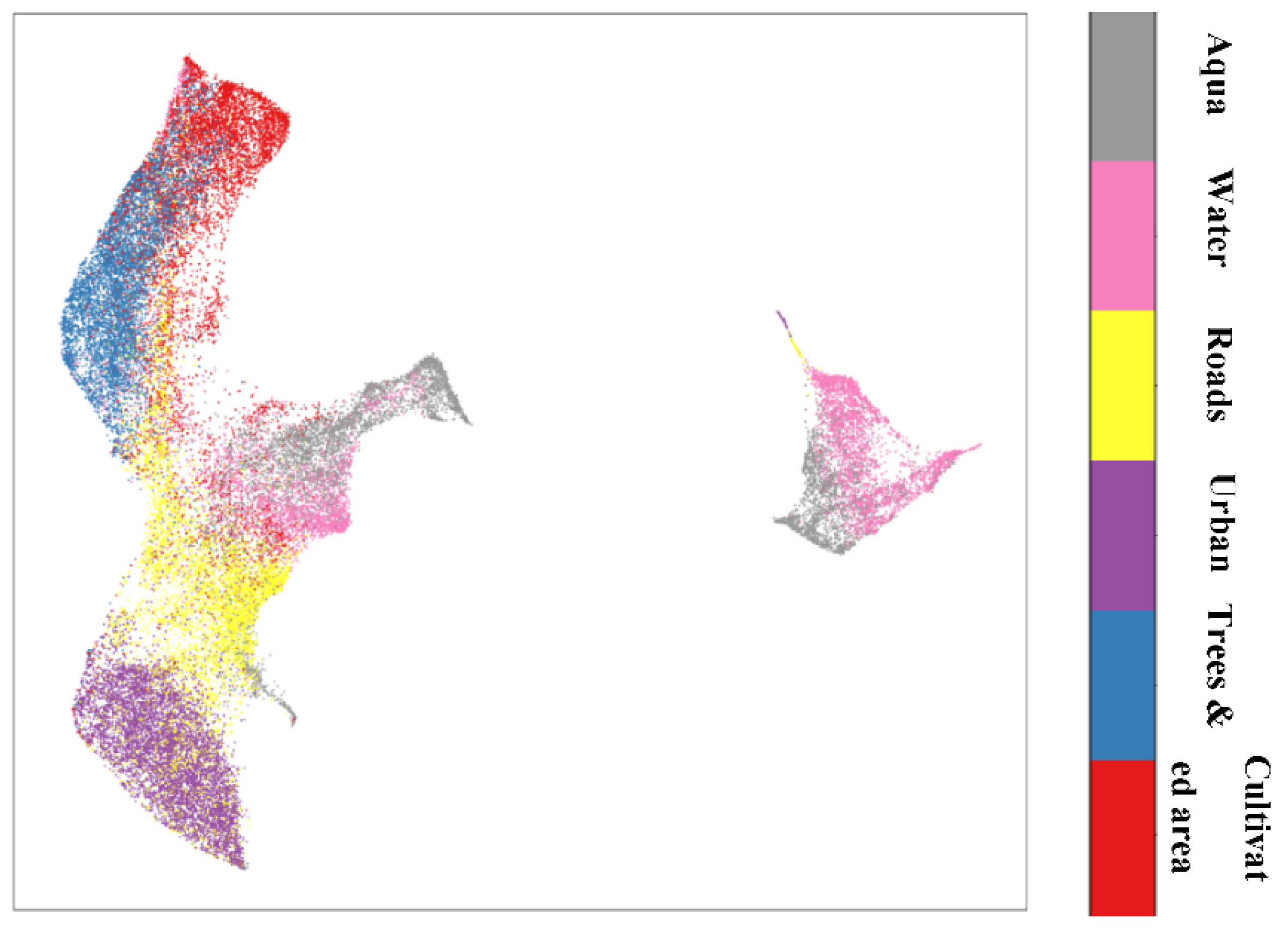

3.2. Data Visualisation

3.2. Models’ Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LULC | Land Use and Land Cover |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| UMAP | Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| DT | Decision Trees |

| XGB | Xtreme Gradient Boosting |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Networks |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| VIs | Vegetation Indices |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| GRD | Ground Range Detected |

| IW | Wide Swath |

| AOI | Area Of Interest |

| CRS | Coordinate Reference System |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique |

| OA | Overall Accuracy |

References

- C. A. f. P. M. a. S. CAPMAS, Statistical Year Book., 2023.

- S. M. Karimi, M. M., A. Dehghani, H. Galavi and Y. F. Huang, “Hybrids of machine learning techniques and wavelet regression for estimation of daily solar radiation,” Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment, vol. 36, p. 4255–4269, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Mirzaei, H. Yu, A. Dehghani, H. Galavi, V. Shokri, S. Mohsenzadeh Karimi and M. Sookhak, “A Novel Stacked Long Short-Term Memory Approach of Deep Learning for Streamflow Simulation,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 23, p. 13384, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Yazici and B. Inan, “Determination of temporal change in land use by geographical information systems: the case of Candir village of Turkey,” Fresenius Environmental Bulletin, vol. 29, no. 5, p. 3579–3593, 2020.

- Z. Xu, “Dynamic monitoring and management system for land resource based on parallel network algorithm and remote sensing,” Journal of Intelligent and Fuzzy System, vol. 37, no. 1, p. 249–262, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, Y. Wang, J. Li, X. Chang, Y. Cao, J. Xie and J. Gong, “High-resolution urban land-cover mapping and landscape analysis of the 42 major cities in China using zy-3 satellite images,” Science Bulletin, vol. 65, p. 1039–1048, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Li, X. He, M. Qiao, X. Cheng, Z. Li, H. Luo, D. Song, D. Li, S. Hu, R. Li, P. Han, F. Qiu, H. Guo, J. Shang and Z. Tian, “Robust Deep Neural Networks for Road Extraction From Remote Sensing Images,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 59, no. 7, pp. 6182-6197, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Liu, N. Chen, X. Zhang, C. Wang and W. Du, “Annual large-scale urban land mapping based on landsat time series in google earth engine and openstreetmap data: A case study in the middle yangtze river basin,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 159, pp. 337-351, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Lu, X. Yang, Z. Wang and Z. Li, “Using multi-level fusion of local features for landuse scene classification with high spatial resolution images in urban coastal zones,” International journal of applied earth observation and geoinformation, vol. 70, p. 1–12, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Leichtle, C. Geiß, T. Lakes and H. Taubenböck, “Class imbalance in unsupervised change detection–a diagnostic analysis from urban remote sensing,” International journal of applied earth observation and geoinformation, vol. 60, p. 83–98, 2017. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, J. He, Y. Yao, J. Zhang, H. Liang, H. Wang and Y. Hong, “Classifying urban land use by integrating remote sensing and social media data,” International Journal of Geographical Information Science, vol. 31, p. 1675–1696, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Jagannathan and C. Divya, “Deep learning for the prediction and classification of land use and land cover changes using deep convolutional neural network,” Ecological Informatics, vol. 65, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Patino and J. C. Duque, “A review of regional science applications of satellite remote sensing in urban settings,” Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, vol. 37, pp. 1-17, 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Cassidy, M. Binford, J. Southworth and G. Barnes, “Social and ecological factors and land-use land-cover diversity in two provinces in Southeast Asia,” Journal of Land Use Science, vol. 5, p. 277–306, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Qiao, X. He, X. Cheng, P. Li, H. Luo, Z. Tian and H. Guo, “Exploiting hierarchical features for crop yield prediction based on 3d convolutional neural networks and multi-kernel gaussian process,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 1-14, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Remelgado, S. Zaitov, S. Kenjabaev, G. Stulina, M. Sultanov, M. Ibrakhimov, M. Akhmedov, V. Dukhovny and C. Conrad, “A crop type dataset for consistent land cover classification in central asia,” Scientific Data, vol. 7, pp. 1-6, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Rudke, T. Fujita, D. de Almeida, M. Eiras, A. Xavier, S. Abou Rafee, E. Santos, M. de Morais, L. Martins, R. de Souza, R. Souza, R. Hallak, E. de Freitas, C. Uvo and J. Martins, “Land cover data of Upper Parana River Basin, South America, at high spatial resolution,” International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, vol. 83, p. 101926, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, S. Du and Q. Wang, “Integrating bottom-up classification and top-down feedback for improving urban land-cover and functional-zone mapping,” Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 212, pp. 231-248, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Bryan, M. Nolan, L. McKellar, J. Connor, D. Newth, T. Harwood, D. King, J. Navarro, Y. Cai, L. Gao, M. Grundy, P. Graham, A. Ernst, S. Dunstall, F. Stock, T. Brinsmead, I. Harman, N. Grigg, M. Battaglia, B. Keating and A. Wonhas, “Land-use and sustainability under intersecting global change and domestic policy scenarios: Trajectories for Australia to 2050,” Global Environmental Change, vol. 38, pp. 130-152, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Chaplin-Kramer, R. Sharp, L. Mandle, S. Sim, J. Johnson, I. Butnar, L. Milà i Canals, B. Eichelberger, I. Ramler, C. Mueller, N. McLachlan, A. Yousefi, H. King and P. Kareiva, “Spatial patterns of agricultural expansion determine impacts on biodiversity and carbon storage,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 112, no. 24, pp. 7402-7407, 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. DeFries, J. Foley and G. Asner, “Land-use choices: balancing human needs and ecosystem function,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 249-257, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, N. Li, L. Wang, J. Zhu and F. Qin, “A multi-angle comprehensive solution based on deep learning to extract cultivated land information from high-resolution remote sensing images,” Ecological Indicators, vol. 141, p. 108961, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Kuemmerle, K. Erb, P. Meyfroidt, D. Müller, P. Verburg, S. Estel, H. Haberl, P. Hostert, M. Jepsen, T. Kastner, C. Levers, M. Lindner, C. Plutzar, P. Verkerk, E. van der Zanden and A. Reenberg, “Challenges and opportunities in mapping land use intensity globally,” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 484-493, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Wulder, N. Coops, D. Roy, J. White and T. Hermosilla, “Land cover 2.0,” International Journal of Remote Sensing, vol. 39, no. 12, p. 4254–4284, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Rogan and D. Chen, “Remote sensing technology for mapping and monitoring land-cover and land-use change,” Progress in Planning, vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 301-325, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Saadeldin, R. O’Hara, J. Zimmermann, B. M. Namee and S. Stuart Green, “Using deep learning to classify grassland management intensity in ground-level photographs for more automated production of satellite land use maps,” Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, vol. 26, p. 100741, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Willis, “Remote sensing change detection for ecological monitoring in United States protected areas,” Biological Conservation, vol. 182, pp. 233-242, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Abdi, “Land cover and land use classification performance of machine learning algorithms in a boreal landscape using Sentinel-2 data,” GIScience & Remote Sensing, vol. 57, no. 1, p. 1–20, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, W. Shen, M. Li and Y. Lv, “Assessing spatio-temporal changes in forest cover and fragmentation under urban expansion in Nanjing, eastern China, from long-term Landsat observations (1987–2017),” Applied Geography, vol. 117, p. 102190, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Zhu, H. Wang, M. Li, J. Diao, W. Shen, Y. Zhang and H. Wu, “Characterizing the effects of climate change on short-term post-disturbance forest recovery in southern China from Landsat time-series observations (1988–2016),” Frontiers of Earth Science, vol. 14, p. 816–827, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Hislop, S. Jones, M. Soto-Berelov, A. Skidmore, A. Haywood and T. Nguyen, “Using landsat spectral indices in time-series to assess wildfire disturbance and recovery,” Remote Sensing, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 460, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Dou and Y. Chen, “Dynamic monitoring of land-use/land-cover change and urban expansion in shenzhen using landsat imagery from 1988 to 2015,” International Journal of Remote Sensing, vol. 38, no. 19, pp. 5388-5407, 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Kussul, M. Lavreniuk, S. Skakun and A. Shelestov, “Deep learning classification of land cover and crop types using remote sensing data,” IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 778-782, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Schultz, J. Clevers, S. Carter, J. Verbesselt, V. Avitabile, H. Quang and M. Herold, “Performance of vegetation indices from Landsat time series in deforestation monitoring,” International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, vol. 52, pp. 318-327, 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Fung, Y. Huang, H. Chai and M. Mirzaei, “Improved SVR machine learning models for agricultural drought prediction at downstream of Langat River Basin, Malaysia,” Journal of Water and Climate Change, vol. 11, no. 4, p. 1383–1398, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Navin and L. Agilandeeswari, “Multispectral and hyperspectral images based land use /land cover change prediction analysis: an extensive review,” Multimedia Tools and Applications, vol. 79, no. 11, p. 29751–29774, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. T. Nguyen, A. Chidthaisong, P. K. Diem and L.-Z. Huo, “A Modified Bare Soil Index to Identify Bare Land Features during Agricultural Fallow-Period in Southeast Asia Using Landsat 8,” Land, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 231, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Tong, G. Xia, Q. Lu, H. Shen, S. Li, S. You and L. Zhang, “Land-cover classification with high-resolution remote sensing images using transferable deep models,” Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 237, p. 111322, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Tavares, N. Beltrão, U. Guimarães and A. Teodoro, “Integration of sentinel-1 and sentinel-2 for classification and LULC mapping in the urban area of Belém, eastern Brazilian Amazon,” Sensors, vol. 19, no. 5, p. 1140, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Iannelli and P. Gamba, “Jointly exploiting Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 for urban mapping,” in IGARSS 2018, Valencia, Spain, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Rousset, M. Despinoy, K. Schindler and M. Mangeas, “Assessment of deep learning techniques for land use land cover classification in southern New Caledonia,” Remote Sensing, vol. 13, no. 12, pp. 1-22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Kotaridis and M. Lazaridou, “Remote sensing image segmentation advances: a meta-analysis,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 173, pp. 309-322, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Maxwell, T. Warner and F. Fang, “Implementation of machine-learning classification in remote sensing: an applied review,” International Journal of Remote Sensing, vol. 39, no. 9, pp. 2784-2817, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Gupta and L. Sharma, “Mixed tropical forests canopy height mapping from spaceborne LiDAR GEDI and multisensor imagery using machine learning models,” Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, vol. 27, p. 100817, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Caffaratti, M. Marchetta, L. Euillades, P. Euillades and R. Forradellas, “Improving forest detection with machine learning in remote sensing data,” Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, vol. 24, p. 100654, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Ma, M. Li, X. Ma, L. Cheng, P. Du and Y. Liu, “A review of supervised object-based land-cover image classification,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 130, pp. 277-293, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Belgiu and L. Drăgut¸, “Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 114, pp. 24-31, 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Mountrakis, J. Im and C. Ogole, “Support vector machines in remote sensing: A review,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 66, no. 3, pp. 247-259, 2011. [CrossRef]

- X. Murray, A. Apan, R. Deo and T. Maraseni, “Rapid assessment of mine rehabilitation areas with airborne LiDAR and deep learning: bauxite strip mining in Queensland, Australia,” Geocarto International, vol. 37, no. 26, pp. 11223-11252, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Yang, Z. Ahmed, U. Schulthess, M. Kamal and R. Rai, “Detecting functional field units from satellite images in smallholder farming systems using a deep learning based computer vision approach: a case study from Bangladesh,” Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, vol. 20, p. 100413, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Milojevic-Dupont and F. Creutzig, “Machine learning for geographically differentiated climate change mitigation in urban areas,” Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 64, p. 102526, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Galar, A. Fernandez, E. Barrenechea, H. Bustince and F. Herrera, “A Review on Ensembles for the Class Imbalance Problem: Bagging-, Boosting-, and Hybrid-Based Approaches,” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews), vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 463-484, 2012. [CrossRef]

- L. Barroso, “The Price of Performance: An Economic Case for Chip Multiprocessing,” Queue, vol. 3, no. 7, pp. 48 - 53, 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Pal, “Random forest classifier for remote sensing classification,” International Journal of Remote Sensing, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 217-222, 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Pal and P. Mather, “Support vector machines for classification in remote sensing,” International Journal of Remote Sensing, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1007-1011, 2005. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, J. Wang, Z. Liu, J. Zhu and F. Qin, “Evaluation of a deep-learning model for multispectral remote sensing of land use and crop classification,” The Crop Journal, vol. 10, p. 1435–1451, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Chen and C. Guestrin, “XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System,” in In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’16), New York, NY, USA, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Ma, Y. Liu, X. Zhang, Y. Ye, G. Yin and B. Johnson, “Deep learning in remote sensing applications: a meta-analysis and review,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 152, pp. 166-177, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Cheng, X. He, M. Qiao, P. Li, S. Hu, P. Peng Chang and Z. Tian, “Enhanced contextual representation with deep neural networks for land cover classification based on remote sensing images,” International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, vol. 107, p. 102706, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Mohammadi, M. Belgiu and A. Stein, “Improvement in crop mapping from satellite image time series by effectively supervising deep neural networks,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 198, p. 272–283, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu, Y. Zhu, R. Zhong, Z. Lin, J. Xu, H. Jiang, J. Huang, H. Li and T. Lin, “DeepCropMapping: A multi-temporal deep learning approach with improved spatial generalizability for dynamic corn and soybean mapping,” Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 247, p. 111946, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Teimouri, M. Dyrmann and R. Jørgensen, “A novel spatio-temporal FCN-LSTM network for recognizing various crop types using multi-temporal radar images,” Remote Sensing, vol. 11, no. 8, p. 990, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Rußwurm and M. Körner, “Temporal vegetation modelling using long short-term memory networks for crop identification from medium-resolution multi-spectral satellite images,” in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 2017, 2017.

- P. Werbos, “Backpropagation through time: what it does and how to do it,” in IEEE, 1990. [CrossRef]

- T. Kattenborn, J. Leitloff, F. Schiefer and S. Hinz, “Review on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) in vegetation remote sensing,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, vol. 173, pp. 24-49, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Portales-Julia, M. Campos-Taberner, F. Garcia-Haro and M. Gilabert, “Assessing the sentinel-2 capabilities to identify abandoned crops using deep learning,” Agronomy, vol. 11, no. 4, p. 654, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Ramsay, “Reviews,” Psychometrika, vol. 68, no. 4, p. 611–612, 2003.

- M. Fishar, “Nile Delta (Egypt),” in The Wetland Book, Finlayson, C., Milton, G., Prentice, R., Davidson, N. ed., Springer, Dordrecht, 2016.

- Sentinel-1, “SAR GRD: C-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar Ground Rane Detected, Log Scaling| Earth Engine data Catalog| Google for Developers,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/COPERNICUS_S1_GRD. [Accessed 04 April 2024].

- M. M. E. R. M. D. A. T. Microsoft Open Source, “Microsoft/PlanetaryComputer,” Microsoft, 28 October 2022. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7261897. [Accessed 2024].

- S. online, “Copernicus Sentinel-2: Major Products Upgrade Upcoming,” Copernicus, 29 September 2021. [Online]. Available: https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/web/sentinel/-/copernicus-sentinel-2-major-products-upgrade-upcoming. [Accessed 2024].

- P. Computer, “Datasets: Sentinel-2 Lvel-2A. Adjusting for the Sentinel-2 Baseline Change,” Microsoft, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://planetarycomputer.microsoft.com/dataset/sentinel-2-l2a#Basline-Change. [Accessed June 2024].

- M. M. A. M. M. Buda, “A systematic study of the class imbalance problem in convolutional neural networks,” Neural Networks, vol. 106, pp. 249-259, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. B. K. H. L. K. W. Chawla, “SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique,” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research , vol. 16, pp. 321-357, 2002. [CrossRef]

- J. Rouse, R. Haas, J. Schell and D. Deering, “Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS,” in NASA. Goddard Space Flight Center 3d ERTS-1 Symp., Vol. 1, Sect. A, Washington DC, 1973.

- G. Camps-Valls, M. Campos-Taberner, Á. Moreno-Martinez, S. Walther, G. Duveiller, A. Cescatti, M. D. Mahecha, J. Muñoz-Mari, F. J. Garcia-Haro, L. Guanter, M. Jung, J. A. Gamon, M. Reichstein and S. W. Running, “A unified vegetation index for quantifying the terrestrial biosphere,” Science Advances, vol. 7, no. 9, p. eabc7447, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. He, P. Shi, D. Xie and Y. Zhao, “Improving the normalized difference build-up index to map urban built-up areas using a semiautomatic segmentation approach,” Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 213-221, 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. Rasul, H. Balzter, G. Ibrahim, H. Hameed, J. Wheeler, B. Adamu, S. Ibrahim and P. Najmaddin, “Applying built-up and bare-soil indices from Landsat 8 to cities in dry climates,” Land, vol. 7, no. 3, p. 81, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Gao, “NDWI—a normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space,” Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 58, p. 257–266, 1996. [CrossRef]

- J. Laonamsai, P. Julphunthong, T. Saprathet, B. Kimmany, T. Ganchanasuragit, P. Chomcheawchan and N. Tomun, “Utilizing NDWI, MNDWI, SAVI, WRI, and AWEI for Estimating Erosion and Deposition in Ping River in Thailand,” Hydrology, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 70, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Lacaux, Y. Tourre, C. Vignolles, J. Ndione and M. Lafaye, “Classification of ponds from high-spatial resolution remote sensing: Application to Rift Valley Fever epidemics in Senegal,” Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 106, no. 1, pp. 66-74, 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Sadeghi, E. Babaeian, M. Tuller and S. B. Jones, “The optical trapezoid model: A novel approach to remote sensing of soil moisture applied to Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 observations,” Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 198, pp. 52-68, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Huete, “A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI),” Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 295-309, 1988. [CrossRef]

- G. Rondeaux, M. Steven and F. Baret, “Optimization of soil-adjusted vegetation indices,” Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 95-107, 1996. [CrossRef]

- A. Huete, K. Didan, T. Miura, E. Rodriguez, X. Gao and L. Ferreira, “Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices,” Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 83, no. 1-2, pp. 195-213, 2002. [CrossRef]

- N. Kumari and S. Min, “Deep Residual SVM: A Hybrid Learning Approach to obtain High Discriminative Feature for Land Use and Land Cover Classification,” in International Conference on Machine Learning and Data Engineering, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Jia, S. Jiang, Z. Lin, N. Li, M. Xu and S. Yu, “A survey: Deep learning for hyperspectral image classification with few labeled samples,” Neurocomputing, vol. 448, p. 179–204, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Dotel, A. Shrestha, A. Bhusal, R. Pathak, A. Shakya and S. Panday, “Disaster Assessment from Satellite Imagery by Analysing Topographical Features Using Deep Learning,” in IVSP ’20: Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Image, Video and Signal Processing, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Jiang, “A Survey on Spatial Prediction Methods,” IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, vol. 20, no. 10, pp. 1-20, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Tran, H. Zhang, J. McMaine, X. Zhang and D. Luo, “10 m crop type mapping using Sentinel-2 reflectance and 30 m cropland data layer product,” International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, vol. 107, p. 102692, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Li, B. Clark, J. Taylor, H. Kendall, G. Jones, Z. Li, S. Jin, C. Zhao, G. Yang, C. Shuai, X. Cheng, J. Chen, H. Yang and L. Frewer, “A hybrid modelling approach to understanding adoption of precision agriculture technologies in Chinese cropping systems,” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, vol. 172, p. 105305, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. D. D. Altarez, A. Apan and T. Maraseni, “Deep learning U-Net classification of Sentinel-1 and 2 fusions effectively demarcates tropical montane forest’s deforestation,” Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, vol. 29, p. 100887, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Arjasakusuma, S. Kusuma, Y. Vetrita, I. Prasasti and R. Arief, “Monthly burned-area mapping using multi-sensor integration of sentinel-1 and sentinel-2 and machine learning: case study of 2019’s fire events in south sumatra province, Indonesia,” Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, vol. 27, p. 100790, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Use, S. Images and T. Methods, “Land Use and Land Cover Mapping Using Sentinel-2, Landsat-8 Two Composition Methods,” Remote Sensing, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 1977, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Mercier, J. Betbeder, F. Rumiano, J. Baudry, V. Gond, L. Blanc, C. Bourgoin, G. Cornu, C. Ciudad, M. Marchamalo, R. Poccard-Chapuis and L. Hubert-Moy, “Evaluation of sentinel-1 and 2 time series for land cover classification of forest–agriculture mosaics in temperate and tropical landscapes,” Remote Sensing, vol. 11, no. 979, p. 1–20, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Bouvet, S. Mermoz, M. Ballère, T. Koleck and T. Le Toan, “Use of the SAR shadowing effect for deforestation detection with Sentinel-1 time series,” Remote Sensing, vol. 10, no. 8, pp. 1-19, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Spracklen and D. Spracklen, “Synergistic use of sentinel-1 and sentinel-2 to map natural forest and acacia plantation and stand ages in north-central vietnam,” Remote Sensing, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 1-19, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Hirschmugl, J. Deutscher, C. Sobe, A. Bouvet, S. Mermoz and M. Schardt, “Use of SAR and optical time series for tropical forest disturbance mapping,” Remote Sensing, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 727, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Khan, M. Fraz and M. Shahzad, “Deep learning based land cover and crop type classification: a comparative study,” in 2021 International Conference on Digital Futures and Transformative Technologies (ICoDT2), Islamabad, Pakistan, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang, L. Gu, X. Li, T. Jiang and R. Ren, “Crop classification method based on optimal feature selection and hybrid CNN-RF networks for multi-temporal remote sensing imagery,” Remote Sensing, vol. 12, no. 19, p. 3119, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Sainburg, L. McInnes and G. T. Q., “Parametric UMAP Embeddings for Representation and Semisupervised Learning,” Neural Computation, vol. 33, no. 11, p. 2881–2907, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Breiman, “Random forests,” Machine Learning, vol. 45, p. 5–32, 2001. [CrossRef]

- B. Yu, W. Qiu, C. Chen, A. Ma, J. Jiang, H. Zhou and Q. Ma, “SubMito-XGBoost: predicting protein submitochondrial localization by fusing multiple feature information and eXtreme gradient boosting,” Bioinformatics, vol. 36, no. 4, p. 1074–1081, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G.-H. Kwak, C.-W. Park, H.-Y. Ahn, S.-I. Na, K.-D. Lee and N.-W. Park, “Potential of Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Networks for Crop Classification with Multitemporal Remote Sensing Images,” Korean Journal of Remote Sensing, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 515-525, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Rußwurm and M. Körner, “Multi-temporal land cover classification with sequential recurrent encoders,” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, vol. 7, no. 4, p. 129, 2018. [CrossRef]

| Operating system | Windows 11 Pro | |

|---|---|---|

| Software environment | Deep learning framework | Tensor Flow |

| Machine learning framework | Sklean, thundersvm, xgboost | |

| Program editor | Python 3 | |

| CUDA | CUDA Toolkit | |

| Hardware environment | CPU | AMD Ryzen 9 9 590HX with Radeon Graphics – 3.30 GHz |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 47.7 GB | |

| Running memory | 64 GB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).