1. Introduction

Stress has been one of the most extensively investigated adaptive responses. It is defined as the organism’s reaction to perceived demands or threats that challenge internal stability [

1]. Exposure to stressors activates the autonomic and neuroendocrine systems to restore homeostasis. Physiologically, this involves stimulation of both the sympatho adreno medullary (SAM) system and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis [

2,

3]. Activation of the SAM system triggers the release of catecholamines such as adrenaline and noradrenaline, resulting in increased heart rate and blood pressure. In parallel, activation of the HPA axis promotes the secretion of glucocorticoids such as cortisol into the bloodstream. Cortisol exerts a profound influence on brain function, and the hippocampus is particularly sensitive to its effects [

4,

5]. Neurobehavioral research has consistently shown that stress related hippocampal dysfunction disrupts spatial learning and memory processes in mammals [

6,

7,

8], including humans [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Spatial learning and memory are fundamental cognitive functions that allow individuals to encode, store, and retrieve information about environmental layout and spatial orientation [

13]. Numerous experimental paradigms have been developed to assess these abilities under stress conditions. Among the most frequently protocols used in humans are psychological stressors such as time pressured arithmetic, the Stroop task, or complex problem-solving matrices, which reliably engage stress responsive systems and have become standard tools for acute stress induction in laboratory settings [

14,

15,

16,

17].

In pre-clinical research, the radial arm maze (RAM) or Morris Water Maze (MWM) are the most established paradigms for assessing spatial learning and memory in rodents [

18,

19]. In this task, animals must learn to retrieve rewards from specific maze arms while avoiding repeated entries into non rewarded ones. The mazes provide quantitative measures of reference memory, which reflect long term learning of rewarded locations, and working memory, which reflect short-term updating of recently visited locations [

18,

19]. However, adapting RAM to human testing presents significant logistical and methodological limitations. A physical human scale maze would require considerable space, and most human studies therefore rely on paper and pencil tasks. These traditional neuropsychological assessments often lack ecological validity because they require participants to imagine spatial transformations or manipulate visual objects in abstract contexts rather than navigate real or realistic environments.

Given these constraints, there is a growing need for experimental tools that can more directly assess hippocampal dependent spatial learning and memory. Tasks involving spatial navigation and temporal sequencing of events provide a more comprehensive and sensitive measure of episodic memory than conventional verbal or object recognition tests [

20]. The recent advancement of VR technology provides an unprecedented opportunity to meet these methodological needs [

21]. VR enables the creation of immersive and interactive environments that combine high ecological validity with precise experimental control [

22]. Virtual environments can be designed to simulate an almost infinite range of conditions while maintaining cost effectiveness and experimental precision [

23]. This approach allows the assessment of behaviors that would be difficult or impossible to reproduce in traditional laboratory settings, such as large-scale navigation or dynamic spatial problem solving.

Conventional neuropsychological assessments remain widely used in clinical contexts for identifying cognitive decline. However, their diagnostic sensitivity can be reduced by confounding variables such as education, age, examiner expertise, and testing environment. In contrast, VR based paradigms can minimize these confounds by standardizing the testing context and engaging participants in realistic and embodied cognitive experiences [

24]. Despite the increasing interest in immersive cognitive assessment, evidence is still scarce regarding the use of spatial memory performance as a discriminative marker for different mental health conditions [

25,

26,

27].

In the present study, we developed an immersive virtual reality adaptation of the radial eight arm maze named NeuroHM, designed to evaluate spatial learning and memory under controlled experimental conditions. The primary objective of this pilot study was to examine how experimentally induced acute stress affects spatial learning and memory in adults and to evaluate the feasibility of NeuroHM as a reliable tool for detecting early cognitive alterations related to stress and mental health conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

All procedures were approved by the Ethical Committees of CUCS UdeG (CUCS/CINV/0017/25) University’s Ethics Committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Prior to testing, subjects were explained on the study’s aims and required to sign informed consent forms. All participants provided their consent. No participants reported being prescribed any psychiatric medications.

2.1. Participants

A demographic questionnaire was used to assess age, sex, education level, prescribed medications situation,

Table 1. One hundred participants were recruited through advertisements posted on the Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud (CUCS) campus. Male and female volunteers were randomly assigned to either the control group (n = 50) or the stress group (n = 50), ensuring an equal distribution between conditions.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Participants were selected according to predefined exclusion criteria. Individuals were excluded if they presented (1) physical impairments that could interfere with task performance, (2) a diagnosis or history of major neurocognitive disorders or psychiatric conditions, including mood disorders, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, anxiety disorders, or developmental conditions, or (3) a history of alcohol abuse or current use of illicit substances. Inclusion criteria recruited participants of 18 to 35 years of age, demonstrate normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity (20/20), and possess the ability to complete a demographic questionnaire and accurately follow the instructions required for the allocentric navigation task.

2.3. Sample Size

Recruitment was conducted from May to August 2025. The sample size calculation was performed to ensure adequate statistical power for the comparisons. The analysis was conducted using GPower (v3.1.). Based on a Generalized linear model using within- and between-subjects interaction and a power of β = 0.80, a significance level of α = 0.05, and a medium effect size of f = 0.25, a total number of 90 participants were needed, finally we adjust to 50 participants in each group.

2.4. Equipment and Software

The experiment was developed and executed using the Unity game engine on a desktop PC with an Intel i7-12650H, 2300Mhz CPU (MSI Cyborg 15 A12V) RAM 64 GB and Nvidia RTX 4050 GPU. Immersive presentation of the virtual environment was delivered through the Meta Quest 3S visor (model P97), a standalone virtual reality headset featuring high-resolution displays, inside-out tracking with integrated cameras, a 110° field of view, and ergonomic hand-held controllers that enable precise interaction with three-dimensional environments.

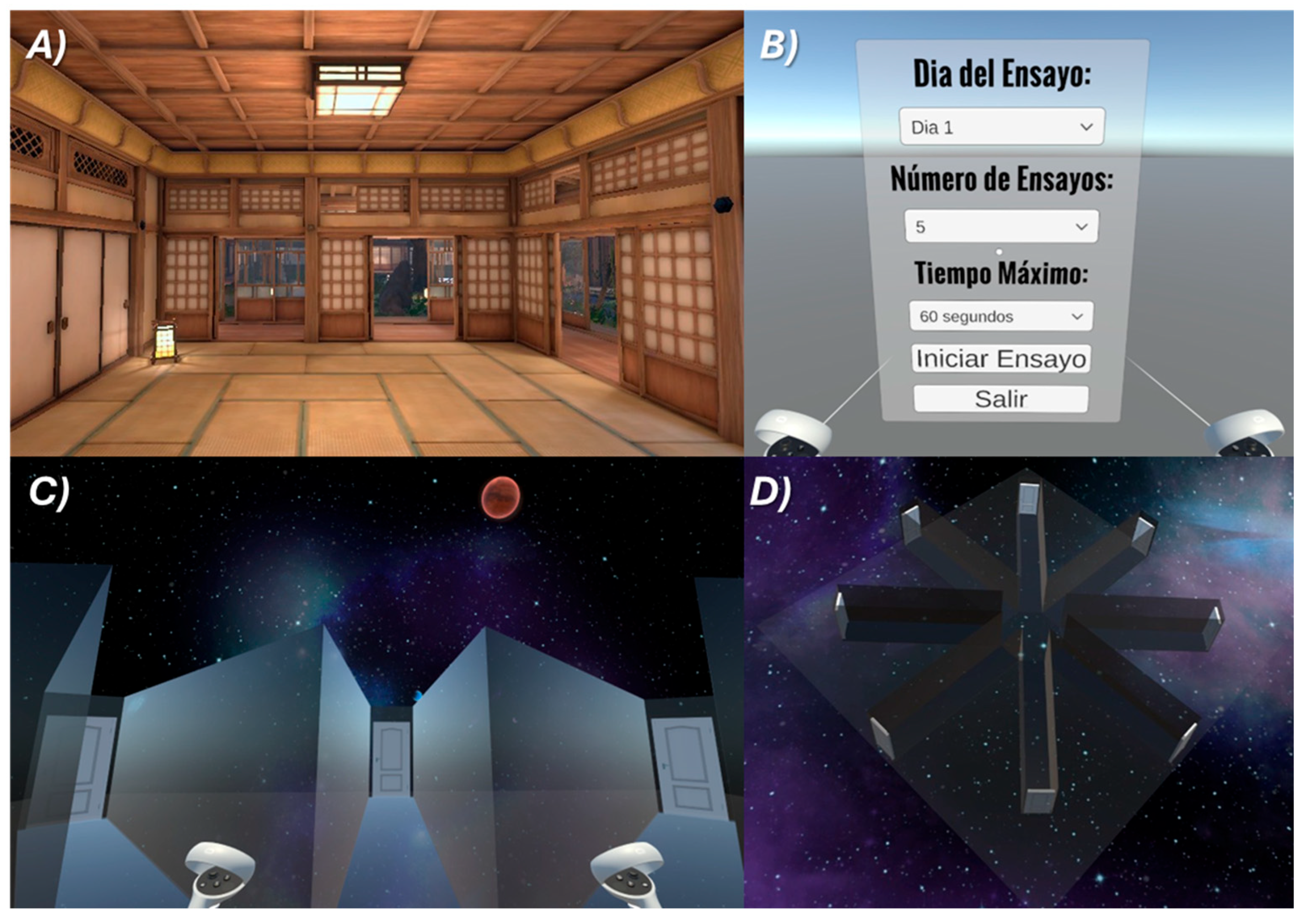

We designed a Virtual Radial Eight Arm Maze program (NeuroHM) using a Unity game engine (Unity Technologies, San Francisco, CA, USA version 6000.1.0f1). The virtual environment was constructed in three dimensions with a central octagonal platform (width: 6m x length: 6m) from which eight immersive equidistant arms (width: 2m x length: 12m x height: 4m) extended radially,

Figure 1. Each arm was designed with a uniform width and length, bounded by walls to prevent participants from leaving the defined pathway. All arms of the maze ended in visible doors, with four exit doors fixed in place. To provide distal spatial cues for allocentric navigation, four large planetary objects were positioned at the cardinal points around the maze. Participants were able to survey their surroundings in full 360° by rotating their heads and bodies while wearing the Meta Quest 3S VR headset, and their movement direction was controlled via a handheld controller.

2.5. Experimental Design

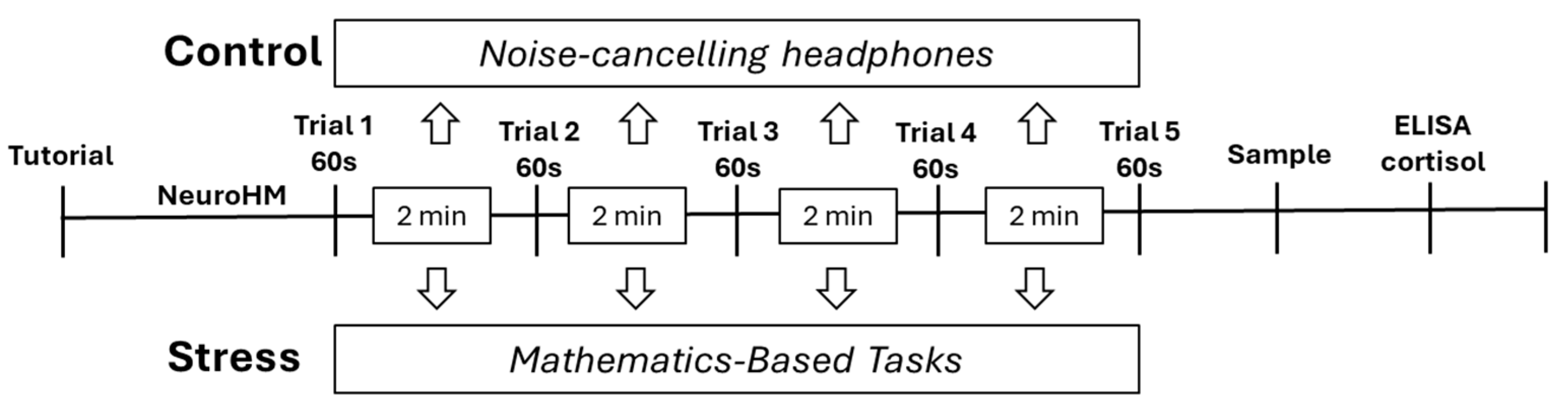

Subjects were allocated into two groups of fifty individuals to complete the virtual reality navigation task. Before the experimental session, all participants received a standardized tutorial designed to habituate them to the immersive environment and to provide instruction on the use of the hand-held controllers for navigating the maze and identifying exit doors. Each participant completed five consecutive trials, each lasting 60 seconds, with a two-minute resting interval between trials.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the control or the stress condition. The control group was not exposed to additional stimuli and remained in a quiet environment using noise-cancelling headphones throughout the session. In contrast, the stress group underwent cognitive stress induction during each two-minute intertrial interval. Specifically, they were required to perform a mathematics-based task under continuous time pressure, administered via the Quick Brain application (Brainsoft Apps). Incorrect responses forced participants to restart the task repeatedly until the interval concluded, thereby maintaining a sustained level of cognitive load and stress. Immediately after the completion of the final trial, salivary samples were collected to assess activation of the HPA axis,

Figure 2.

2.6. Procedure VR Radial Arm Maze for Humans

Cognitive performance was assessed using the NeuroHM virtual radial eight-arm maze task. The primary objective of the task was to locate the four exit doors within a maximum duration of 60 seconds per trial, minimizing the number of errors by employing mnemonic and spatial mapping strategies. The main dependent variables in NeuroHM were quantified through three behavioral parameters: (1) latency, defined as the total time required to complete the maze; (2) reference memory errors, defined as the number of first entries into arms that did not contain an exit; and (3) working memory errors, defined as the number of re-entries into previously visited arms that did not contain an exit. All behavioral variables were automatically recorded within the virtual environment for each of the five trials completed by every participant.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were first examined for normality and homogeneity of variances using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests, respectively. Descriptive statistics are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Between-group comparisons (control vs. stress) for the main dependent variables (latency, reference memory errors, working memory errors, and salivary cortisol concentrations) were analyzed using independent-sample t tests. Trial-by-trial performance across the five sessions was evaluated using repeated measures ANOVA, Sidak’s post hoc multiple comparison test was applied to identify specific differences. A significant level of p < 0.05 was used for all analyses.

3. Results

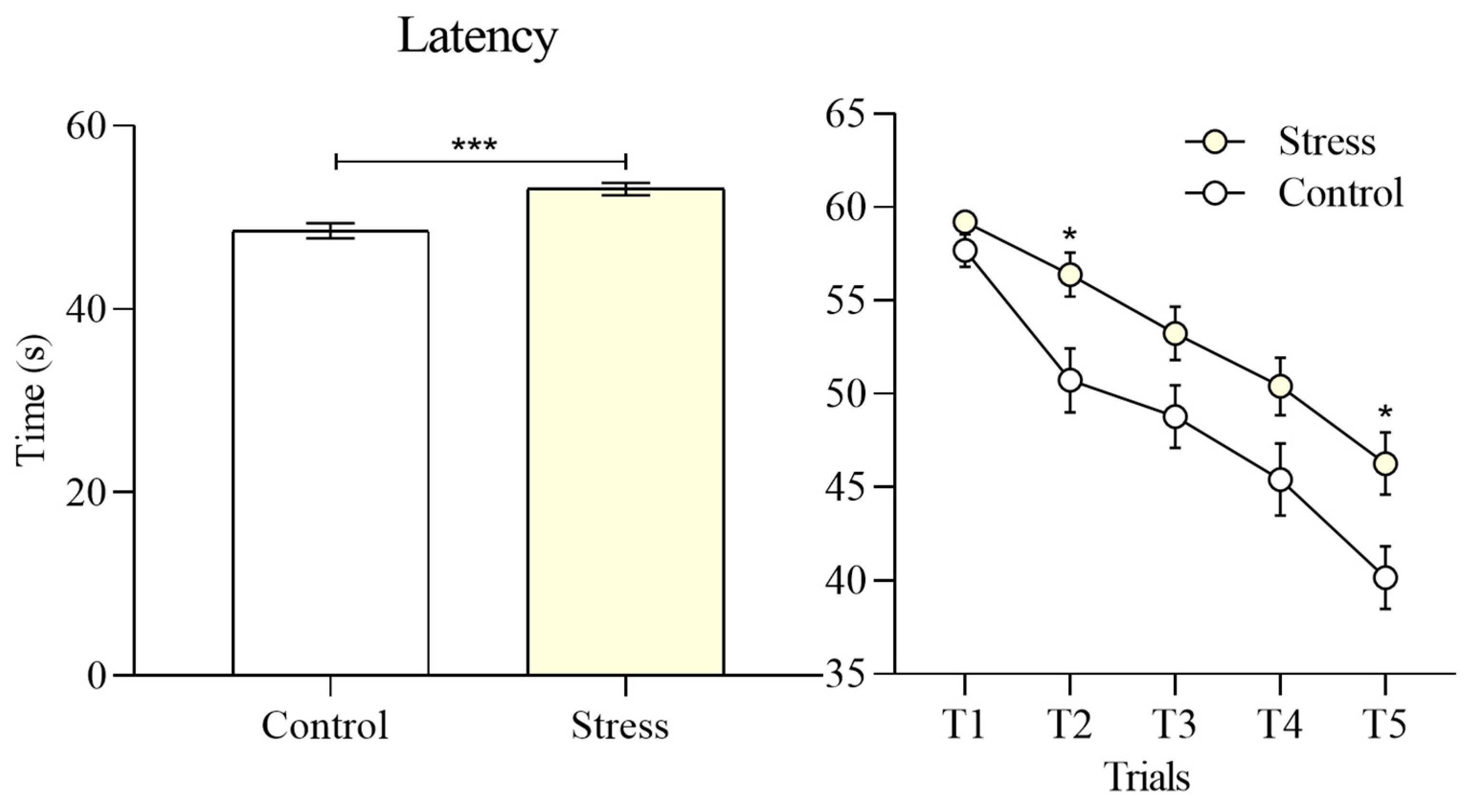

To evaluate task performance, Student’s t tests were conducted on the principal dependent variables. Latency, defined as the total time required to complete the maze, was significantly increased in the stress group compared with the control group (53.11 ± 0.66 vs 48.55 ± 0.82, t = 4.290, p < 0.001),

Figure 3. Trial-by-trial analysis revealed that this effect was particularly pronounced in the second trial (t = 2.710, p = 0.03) and the fifth trial (t = 2.925, p = 0.02). Despite this impairment, both groups demonstrated a progressive reduction in completion time across successive trials, indicating learning of the task rules and successful identification of the four exit doors.

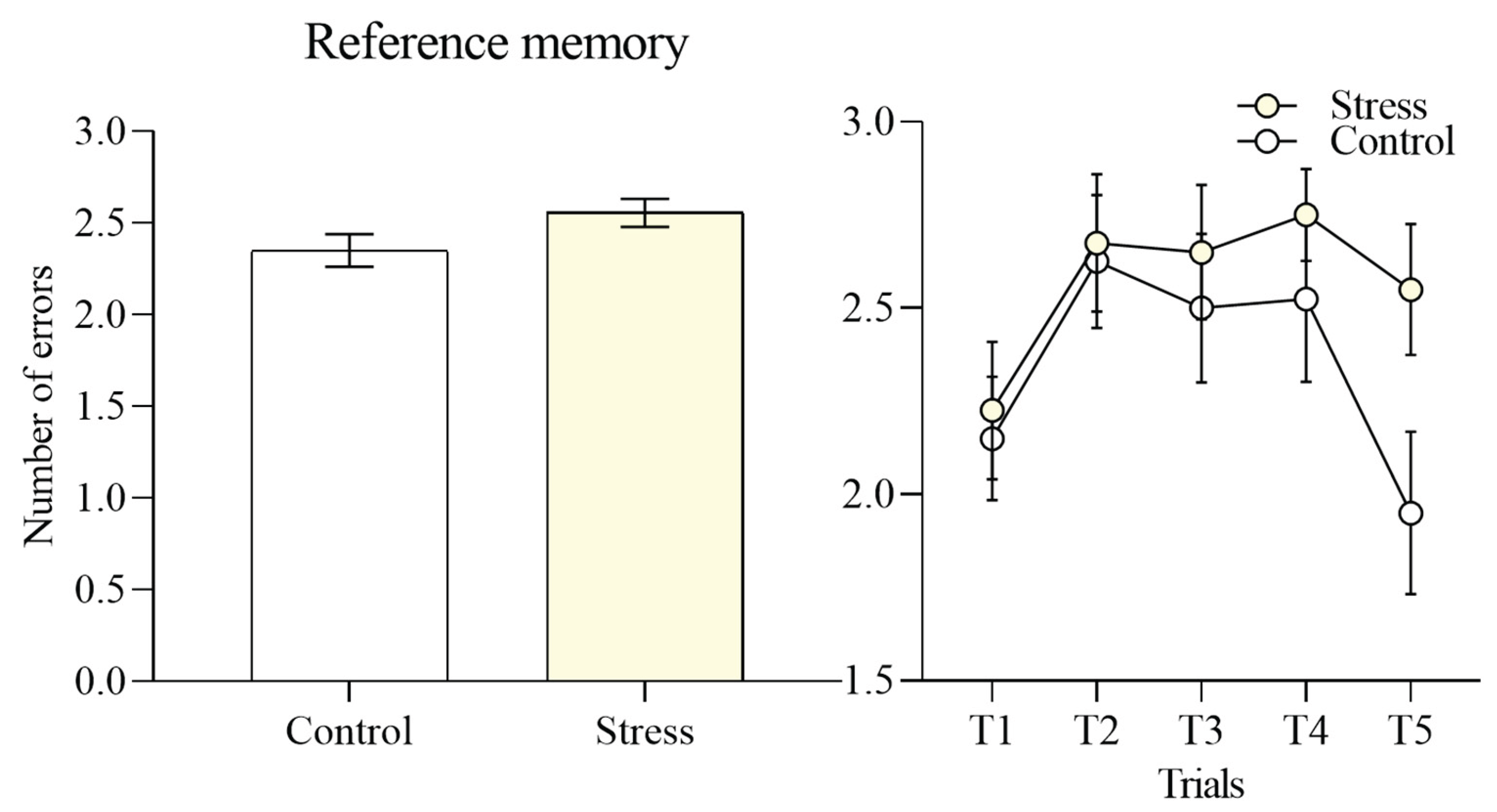

Reference memory performance, quantified as the number of initial entries into arms that did not contain an exit, did not differ significantly between groups (2.55 ± 0.07 vs 2.35 ± 0.08),

Figure 4. This indicates that both stressed and control participants were equally able to acquire long-term knowledge of the location of correct exits.

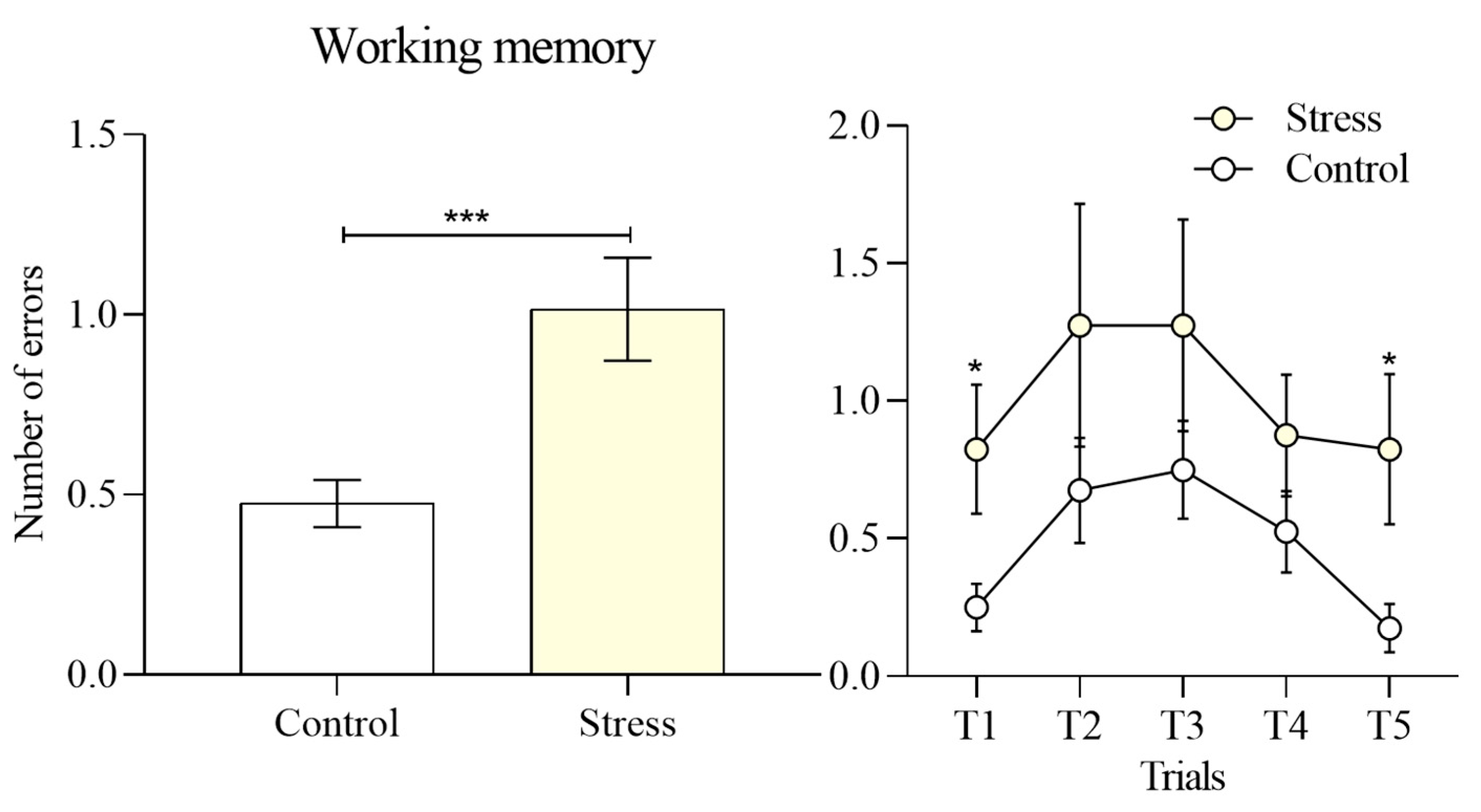

In contrast, working memory, operationalized as the number of re-entries into arms that did not contain an exit, showed a significant impairment in the stress group relative to controls (1.015 ± 0.14 vs 0.47 ± 0.66,

t = 3.416,

p < 0.001),

Figure 5. The magnitude of this effect was especially evident in the first trial (

t = 2.303,

p = 0.03) and the fifth trial (

t = 2.273,

p = 0.03). These findings suggest that acute stress selectively disrupted short-term trial-to-trial updating, leading to an increased tendency to revisit previously explored incorrect paths.

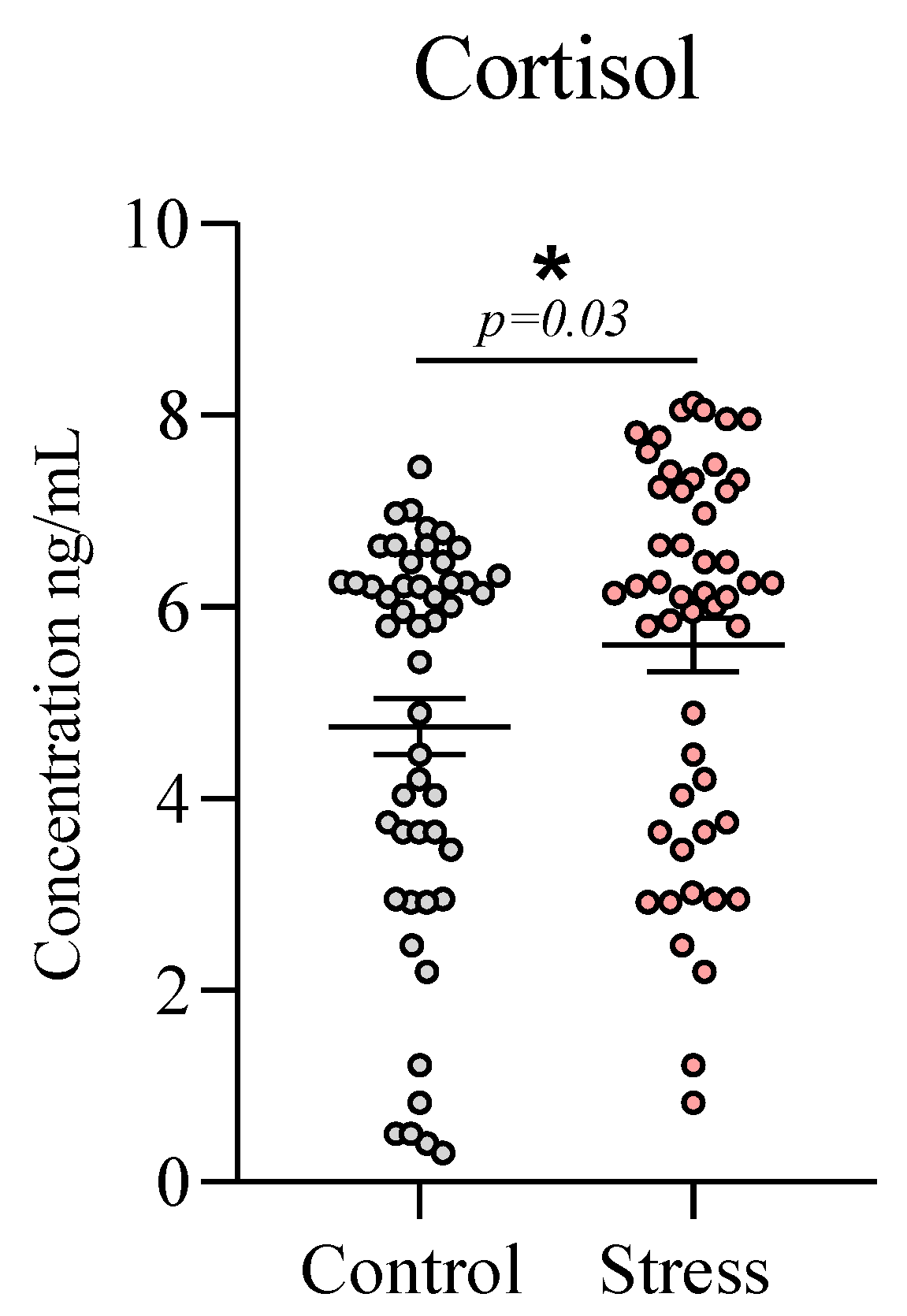

Finally, analysis of salivary cortisol concentrations confirmed the effectiveness of the stress induction procedure. The stress group exhibited a significant post-test increase compared with the control group (5.60 ± 0.28 vs 4.72 ± 0.30,

t = 2.142,

p = 0.03), confirming the efficacy of the stress induction protocol,

Figure 6.

4. Discussion

The results confirmed that the laboratory stress protocol successfully elicited a physiological stress response, as reflected by a significant increase in salivary cortisol concentrations among participants in the stress condition. As hypothesized, acute stress exposure led to a deterioration in cognitive performance, characterized by longer maze completion times and a higher number of working memory errors.

The observed data support the hypothesis that acute stress induces a shift in navigation strategies from flexible, cognitive, hippocampal-dependent mechanisms toward more rigid, habit-based, cortico-striatal strategies [

28,

29]. This finding aligns with previous studies reporting that stress alters the balance between memory systems, favoring procedural responses over spatial or declarative strategies [

6,

30,

31,

32]. Here, stressors were applied during the navigation task itself, including the intertrial intervals, suggesting that both the HPA and SAM axis were simultaneously active [

33]. Consistent with this interpretation, participants in the stress group exhibited significantly higher salivary cortisol [

34] concentrations following task completion.

The interaction between cognitive and affective cortical networks and the HPA axis suggests that stress-related hormonal activity can directly modulate cognition. One plausible mechanism for this shift involves catecholaminergic signaling within the basolateral amygdala (BLA), which promotes a transition from hippocampal-based memory retrieval toward striatal-based memory encoding [

35]. Catecholamines such as noradrenaline rapidly enhance excitatory transmission and synaptic plasticity through β-adrenergic receptors, while α-adrenergic receptors also contribute to stress-induced modulation. In parallel, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) acting through CRF1 receptors increases limbic excitability and promotes glutamate release, thereby enabling rapid structural and synaptic changing in hippocampal CA1 neurons [

36,

37]. Furthermore, catecholamines and neuropeptides exert rapid effects within minutes through membrane-bound receptors, whereas corticosteroids act more slowly by binding to intracellular glucocorticoid receptors that regulate gene transcription [

38]. Consequently, stress mediators can alter neuronal activity and plasticity over a broad temporal range—from minutes to hours to explain why brief stress exposure can influence memory management. In the current study, we observed a transient increase in working memory errors in the stress group, likely reflecting prefrontal cortical involvement and the short-term impact of acute stress on executive processes [

35].

Our research tool is meaningful because it introduces an immersive virtual reality version of the radial arm maze specifically designed for human participants, addressing the ecological and methodological limitations of previous two-dimensional or non-immersive adaptations. Earlier studies employing virtual mazes for humans often relied on flat monitors or simplified environments [

39,

40,

41], which restricted the participant’s sense of presence and reduced engagement of spatial navigation systems. More recently, Kim, Park, and Kim (2018) implemented a head-mounted display version of the radial arm maze to assess spatial learning and memory in humans, demonstrating that virtual navigation tasks can successfully reproduce spatial learning patterns similar to those observed in rodents [

42]. However, their design remained limited in environmental complexity and interactivity, highlighting the need for more immersive and ecologically valid approaches.

The NeuroHM task builds upon and extends these developments by providing a fully interactive three-dimensional environment that allows natural exploration through a head-mounted display, enhancing both ecological validity and the realism of spatial cues. We developed a fully immersive virtual reality maze that offers a 360-degree navigational experience, allowing participants to move freely and explore the environment. The maze design faithfully replicates the classical configuration of the radial arm maze, incorporating elevated walls along each corridor to recreate the perception of enclosed escape arms and maintain spatial orientation. The central platform was intentionally enlarged and designed as an active navigational area rather than a simple transition zone, allowing participants to integrate distal cues into their route-planning strategies. Furthermore, the maze was specifically configured to support real-time data acquisition, thereby allowing for immediate retrieval and comprehensive analysis of behavioral metrics by researchers.

The main limitation of the present study concerns the restricted sample size, which limited the statistical power of the analyses and the generalizability of the findings. Large-scale population studies, such as that conducted by Coutrot et al. [

43], who assessed spatial navigation ability in more than 2.5 million participants worldwide using a mobile application, emphasize the importance of extensive datasets for characterizing individual variability in spatial learning and memory. Future research should therefore aim to increase the number and diversity of participants to enhance statistical robustness and external validity. Another limitation is the absence of complementary neuropsychological assessments. Including standardized cognitive batteries would enable direct comparisons between traditional measures of memory and performance on immersive spatial navigation tasks, providing stronger construct validity. It is also important to consider that the technological characteristics of different virtual reality systems (display resolution, field of view, frame rate, and motion tracking precision), may influence the encoding and retrieval of spatial information. These variations could account for discrepancies among studies employing different hardware or software configurations. Furthermore, future investigations could integrate neuroimaging and electrophysiological techniques to examine the neural correlations of virtual navigation under experimental conditions. Moreover, future research should experimentally assess individuals with clinically diagnosed cognitive impairments. These evaluations would yield critical evidence on the sensitivity of the NeuroHM task in detecting hippocampal-dependent dysfunctions and would further substantiate its utility as a diagnostic and monitoring instrument.

5. Conclusions

The current study presents NeuroHM, a novel virtual reality system for assessing spatial learning and memory in humans. This immersive adaptation of the radial eight-arm maze proved sensitive to stress-induced cognitive alterations, as participants under acute stress showed increased cortisol levels and reduced performance. These findings highlight NeuroHM as a promising tool for cognitive assessment and translational research in mental health.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, D.F.-Q.; methodology, P.A. Á-D., D. E. M.-F., and D.F.-Q.; software, P.A. Á-D.; validation, D. E. M.-F., and D.F.-Q.; formal analysis, P.A. Á-D., and D. E. M.-F.; investigation, P.A. Á-D., D. E. M.-F., and D.F.-Q.; resources, P.A. Á-D.; data curation, D. E. M.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, P.A. Á-D., and D. E. M.-F.; writing—review and editing, D.F.-Q.; visualization, D.F.-Q.; supervision, D.F.-Q.; project administration, D.F.-Q.; funding acquisition, D.F.-Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Guadalajara, through the “Programa de Apoyo a la Mejora en las Condiciones de Producción de las Personas Integrantes del SNII y SNCA (PROSNII) 2025”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was part of a research project that had been approved by the ethics committee of the University of Guadalajara (Approval ID: CI-01225).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability Statements are available in present manuscript

Acknowledgments

We thanks to Neuroscience Department of University of Guadalajara.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRF |

Corticotropin-Releasing Factor |

| HPA |

Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal axis |

| MWM |

Morris Water Maze |

| RAM |

Radial Arm Maze |

| SAM |

Sympathy Adrenal Medullary axis |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

References

- Goldstein, D.S.; Kopin, I.J. Evolution of Concepts of Stress. Stress 2007, 10, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Herk, L.; Schilder, F.P.M.; de Weijer, A.D.; Bruinsma, B.; Geuze, E. Heightened SAM- and HPA-Axis Activity during Acute Stress Impairs Decision-Making: A Systematic Review on Underlying Neuropharmacological Mechanisms. Neurobiol Stress 2024, 31, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Kan, Y.; Wu, M.; Ball, L.J.; Duan, H. The HPA and SAM Axis Mediate the Impairment of Creativity under Stress. Psychophysiology 2024, 61, e14472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, B.E.; Harris, B.B.; Turk-Browne, N.B.; Sinha, R.; Goldfarb, E.V. Hippocampal Mechanisms Support Cortisol-Induced Memory Enhancements. J Neurosci 2023, 43, 7198–7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremen, W.S.; Panizzon, M.S.; Lyons, M.J.; Franz, C.E. Cortisol and Brain: Beyond the Hippocampus. Biol Psychiatry 2011, 69, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Quezada, D.; Moran-Torres, D.; Luquin, S.; Ruvalcaba-Delgadillo, Y.; García-Estrada, J.; Jáuregui-Huerta, F. Male/Female Differences in Radial Arm Water Maze Execution After Chronic Exposure to Noise. Noise Health 2019, 21, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazma, M.A.; Shields, G.S.; Yonelinas, A.P. The Effects of Post-Encoding Stress and Glucocorticoids on Episodic Memory in Humans and Rodents. Brain Cogn 2019, 133, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, A.; Gavini, K.; Yang, E.; Lyman-Henley, L.; Parameshwaran, K. Chronic Traumatic Stress Impairs Memory in Mice: Potential Roles of Acetylcholine, Neuroinflammation and Corticotropin Releasing Factor Expression in the Hippocampus. Behav Brain Res 2017, 335, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupien, S.J.; Fiocco, A.; Wan, N.; Maheu, F.; Lord, C.; Schramek, T.; Tu, M.T. Stress Hormones and Human Memory Function across the Lifespan. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaedflieg, C.W.E.M.; Schneider, T.R.; Daume, J.; Engel, A.K.; Schwabe, L. Stress Impairs Intentional Memory Control through Altered Theta Oscillations in Lateral Parietal Cortex. J Neurosci 2020, 40, 7739–7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, J.P.; Giorgio, L.-M.; Zaborowska, O.; Sheldon, S. Acute Psychosocial Stress during Retrieval Impairs Pattern Separation Processes on an Episodic Memory Task. Stress 2020, 23, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinbockel, H.; Wagner, A.D.; Schwabe, L. Post-Retrieval Stress Impairs Subsequent Memory Depending on Hippocampal Memory Trace Reinstatement during Reactivation. Sci Adv 2024, 10, eadm7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, N.; Maguire, E.A.; O’Keefe, J. The Human Hippocampus and Spatial and Episodic Memory. Neuron 2002, 35, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Carrasco, D.; Casa, L.G.D.L. Spanish Validation of the Maastricht Acute Stress Test (MAST): A Cost-Effective Stress Induction Protocol. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 2025, 28, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Deb, N.; Sengupta, K.; Phukan, A.; Choudhury, N.; Kashyap, S.; Phadikar, S.; Saha, R.; Das, P.; Sinha, N.; et al. SAM 40: Dataset of 40 Subject EEG Recordings to Monitor the Induced-Stress While Performing Stroop Color-Word Test, Arithmetic Task, and Mirror Image Recognition Task. Data Brief 2022, 40, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Pirke, K.M.; Hellhammer, D.H. The ’Trier Social Stress Test’--a Tool for Investigating Psychobiological Stress Responses in a Laboratory Setting. Neuropsychobiology 1993, 28, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, P.; Kirschbaum, C. Human Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Responses to Acute Psychosocial Stress in Laboratory Settings. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010, 35, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandeis, R.; Brandys, Y.; Yehuda, S. The Use of the Morris Water Maze in the Study of Memory and Learning. Int. J. Neurosci. 1989, 48, 29–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, R.H. Spatial and Temporal Response Patterns on the Eight-Arm Radial Maze. Physiol. Behav. 1986, 36, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A. Virtual Reality in Episodic Memory Research: A Review. Psychon Bull Rev 2019, 26, 1213–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimadevilla, J.M.; Nori, R.; Piccardi, L. Application of Virtual Reality in Spatial Memory. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookes, J.; Warburton, M.; Alghadier, M.; Mon-Williams, M.; Mushtaq, F. Studying Human Behavior with Virtual Reality: The Unity Experiment Framework. Behav Res Methods 2020, 52, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagaspe, P.; Amieva, H.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Olive, J.; de la Rivière, J.-B.; Chartier, C.; Taillard, J.; Philip, P. Validity and Diagnostic Performance of a Virtual Reality-Based Supermarket Application “MEMOSHOP” for Assessing Episodic Memory in Normal and Pathological Aging. Digit Health 2023, 9, 20552076231218808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-H. Can the Virtual Reality-Based Spatial Memory Test Better Discriminate Mild Cognitive Impairment than Neuropsychological Assessment? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 9950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallet, G.; Sauzéon, H.; Pala, P.A.; Larrue, F.; Zheng, X.; N’Kaoua, B. Virtual/Real Transfer of Spatial Knowledge: Benefit from Visual Fidelity Provided in a Virtual Environment and Impact of Active Navigation. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2011, 14, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddle, R.A.; Volkova, E.; Mohler, B.; Bülthoff, H.H. The Effect of Landmark and Body-Based Sensory Information on Route Knowledge. Mem Cognit 2011, 39, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehn, L.B.; Kater, L.; Piefke, M.; Botsch, M.; Driessen, M.; Beblo, T. Training in a Comprehensive Everyday-like Virtual Reality Environment Compared to Computerized Cognitive Training for Patients with Depression. Computers in Human Behavior 2018, 79, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunyé, T.T.; Wood, M.D.; Houck, L.A.; Taylor, H.A. The Path More Travelled: Time Pressure Increases Reliance on Familiar Route-Based Strategies during Navigation. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove) 2017, 70, 1439–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.I.; Gagnon, S.A.; Wagner, A.D. Stress Disrupts Human Hippocampal-Prefrontal Function during Prospective Spatial Navigation and Hinders Flexible Behavior. Curr Biol 2020, 30, 1821–1833.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, A.P.; Bullock, T.; MacLean, M.H.; Santander, T.; Raymer, J.; Stuber, A.; Jimmons, L.; Okafor, G.N.; Grafton, S.T.; Miller, M.B.; et al. Resilience of Navigation Strategy and Efficiency to the Impact of Acute Stress. Spatial Cognition & Computation 2024, 24, 195–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhang, W. Way-Finding during a Fire Emergency: An Experimental Study in a Virtual Environment. Ergonomics 2014, 57, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, A.; Munns, M.E.; Kasowski, J.; Zhou, M.; He, C.; Grafton, S.T.; Giesbrecht, B.; Hegarty, M.; Beyeler, M. Stress Affects Navigation Strategies in Immersive Virtual Reality. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 5949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.E.; VanderKaay Tomasulo, M.M. Influence of Acute Stress on Spatial Tasks in Humans. Physiology & Behavior 2011, 103, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellhammer, D.H.; Wüst, S.; Kudielka, B.M. Salivary Cortisol as a Biomarker in Stress Research. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsegyan, A.; Mackenzie, S.M.; Kurose, B.D.; McGaugh, J.L.; Roozendaal, B. Glucocorticoids in the Prefrontal Cortex Enhance Memory Consolidation and Impair Working Memory by a Common Neural Mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 16655–16660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandael, D.; Wierda, K.; Vints, K.; Baatsen, P.; De Groef, L.; Moons, L.; Rybakin, V.; Gounko, N.V. Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Induces Functional and Structural Synaptic Remodelling in Acute Stress. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsegyan, A.; Mirone, G.; Ronzoni, G.; Guo, C.; Song, Q.; van Kuppeveld, D.; Schut, E.H.S.; Atsak, P.; Teurlings, S.; McGaugh, J.L.; et al. Glucocorticoid Enhancement of Recognition Memory via Basolateral Amygdala-Driven Facilitation of Prelimbic Cortex Interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 7077–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joëls, M.; Sarabdjitsingh, R.A.; Karst, H. Unraveling the Time Domains of Corticosteroid Hormone Influences on Brain Activity: Rapid, Slow, and Chronic Modess. Pharmacological Reviews 2012, 64, 901–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astur, R.S.; Ortiz, M.L.; Sutherland, R.J. A Characterization of Performance by Men and Women in a Virtual Morris Water Task:: A Large and Reliable Sex Difference. Behavioural Brain Research 1998, 93, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Hao, X.; Wang, Z.; Duan, Y.; Liu, F.; Marsh, R.; Yu, S.; Peterson, B.S. A Virtual Radial Arm Maze for the Study of Multiple Memory Systems in a Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Environment. Int J Virtual Real 2012, 11, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zeev, T.; Weiss, I.; Ashri, S.; Heled, Y.; Ketko, I.; Yanovich, R.; Okun, E. Mild Physical Activity Does Not Improve Spatial Learning in a Virtual Environment. Front Behav Neurosci 2020, 14, 584052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, K.K. Spatial Learning and Memory Using a Radial Arm Maze with a Head-Mounted Display. Psychiatry Investig 2018, 15, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutrot, A.; Silva, R.; Manley, E.; de Cothi, W.; Sami, S.; Bohbot, V.D.; Wiener, J.M.; Hölscher, C.; Dalton, R.C.; Hornberger, M.; et al. Global Determinants of Navigation Ability. Curr Biol 2018, 28, 2861–2866.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).