1. Introduction

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders worldwide. ADHD is characterized by symptoms such as difficulty sustaining attention, the onset of hyperactive behavior, and increased recklessness (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), usually manifesting before the age of 12 years. Both the treatment and understanding of ADHD require a multidimensional approach, as the consequences of the disorder are wide-ranging and vary considerably from person to person (Katsarou et al., 2024).

In addition to the difficulties experienced by individuals with ADHD in terms of cognitive functioning and social behavior, the disorder has been shown to have a significant impact on language development, which is regarded as particularly important for children’s overall cognitive, educational, and social development critical for both academic and social success (Al-Dakroury, 2018). Language development challenges faced by individuals with ADHD include difficulties in understanding and using language, storytelling, and producing complex language structures (Sciberras et al., 2014).

Over the past decade, an expanding body of research has underscored the multifaceted relationship between Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and language development in children. Empirical findings indicate that children with ADHD frequently encounter difficulties across various linguistic domains, including phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics, as well as in the dynamic interplay among these components (Bruce et al., 2016). Despite the accumulation of relevant evidence, the precise mechanisms through which ADHD affects language acquisition and structure remain insufficiently delineated, thereby warranting a comprehensive synthesis of existing knowledge and the identification of emerging patterns.

In light of this, the present article seeks to systematically review the extant literature concerning the impact of ADHD on children’s language development. Specifically, it examines the interrelations among core linguistic domains and addresses the persistent challenges associated with the differential diagnosis of ADHD-related language impairments (Antshel & Russo, 2019). Furthermore, attention is directed to the pivotal contributions of occupational therapists and psychologists in fostering language development among children with ADHD (Cohen et al., 2017). The article concludes by outlining evidence-based, targeted interventions designed to enhance linguistic competencies in this population..

2. Methodology

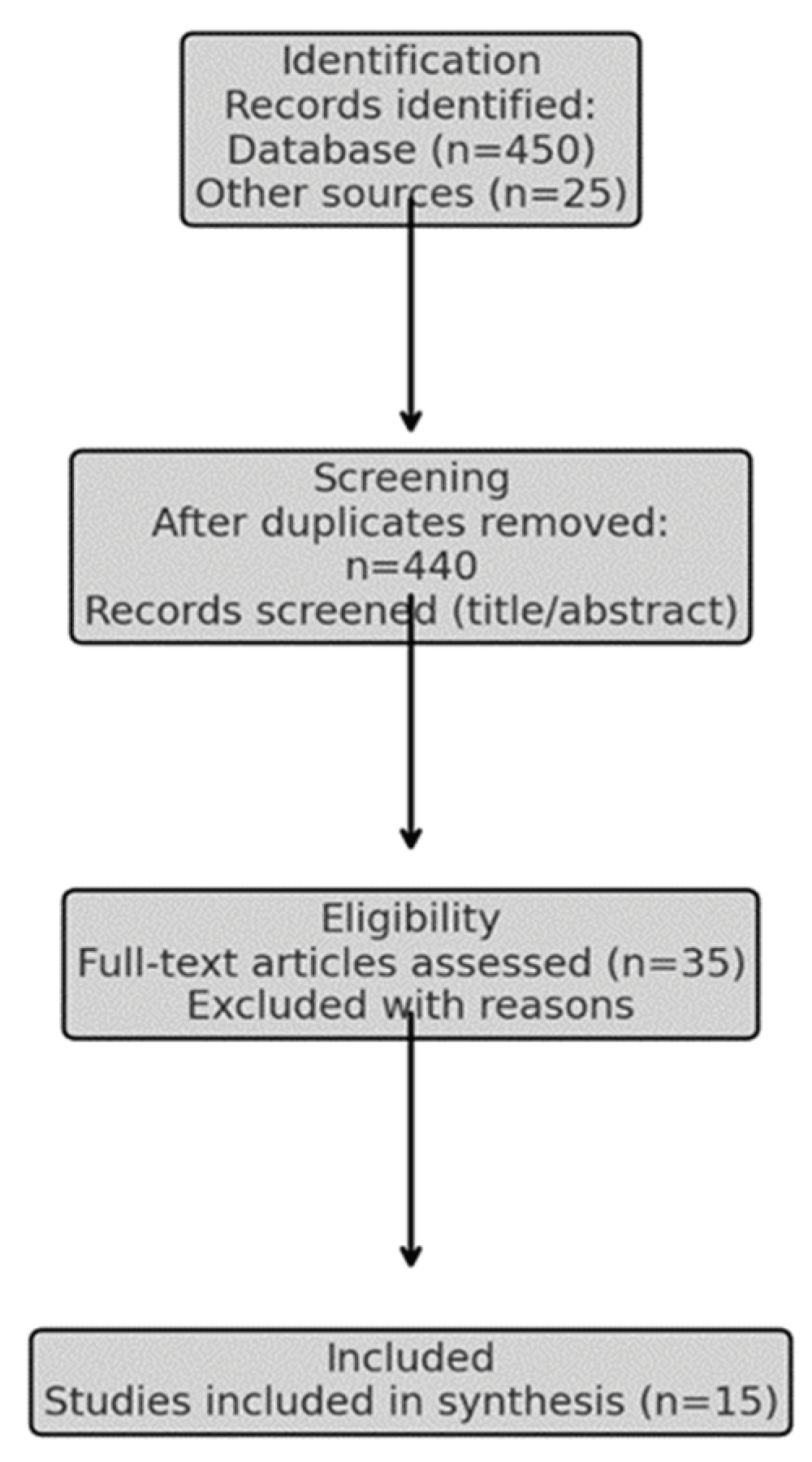

The present study employed a systematic literature review approach, following the principles of the PRISMA framework, in order to critically examine the relationship between Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and language development in children. The methodology was designed to ensure transparency, replicability, and rigor in the identification, selection, and synthesis of relevant research.

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search of the academic literature was conducted across multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. These databases were selected as they provide extensive coverage of peer-reviewed publications in psychology, psychiatry, education, and allied health sciences. The search was guided by carefully constructed Boolean expressions to maximize sensitivity and specificity. Keywords included: “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder” OR “ADHD” AND (“children” OR “adolescents”) AND (“language development” OR “phonology” OR “morphology” OR “syntax” OR “semantics” OR “pragmatics” OR “executive functions” OR “interventions”).

The time frame of the search was restricted to studies published between January 2010 and March 2025 to capture both seminal work and the most recent advancements. Only articles written in English were considered. Additional records were identified by screening the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined prior to the review process to minimize bias. Studies were included if they examined children or adolescents (ages 3–18) formally diagnosed with ADHD according to standardized diagnostic criteria (DSM-IV, DSM-5, ICD-10/11). They also had to investigate at least one aspect of language development (phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, narrative ability, or written expression). Furthermore, the studies needed to report empirical findings (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods), or were systematic reviews/meta-analyses of such studies, and finally, only studies published in peer-reviewed journals were considered.

Exclusion criteria were also clearly defined to further ensure the quality and relevance of the studies included in the review. Studies were excluded if they focused exclusively on adults with ADHD, if they did not have a confirmed ADHD diagnosis, if they were case reports, conference abstracts, opinion papers, or non-peer-reviewed sources. Additionally, articles not published in English were excluded from the review.

2.2. Study Selection

The selection process unfolded in four stages, following the PRISMA framework. During the identification phase, the initial database search yielded 450 records, with an additional 25 records identified through reference screening. After removing duplicates, 440 unique records remained and were screened by title and abstract for relevance. In the eligibility phase, 35 full-text articles were retrieved and carefully assessed against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles were excluded at this stage if they lacked an ADHD diagnosis, focused on non-linguistic outcomes, or presented methodological weaknesses. Ultimately, 15 studies met all eligibility criteria and were included in the final synthesis.

Data extraction was conducted using a structured template to ensure methodological consistency. For each study, information was recorded regarding bibliographic details (author, year, and country of study), sample characteristics (age, gender distribution, ADHD subtype, and comorbidities), methodological design (longitudinal, cross-sectional, experimental, quasi-experimental, or review), assessment tools used for ADHD diagnosis and language measurement, the specific language domains investigated (phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and written expression), as well as the main findings related to language difficulties, differential diagnosis, or intervention outcomes.

The analysis proceeded in two stages. First, the studies were categorized according to the five core domains of language development, with additional categories for executive functions, differential diagnosis, and therapeutic interventions. Second, a thematic synthesis was undertaken to identify patterns of evidence across studies, highlight methodological strengths and limitations, and pinpoint areas of consensus and disagreement within the literature. Particular attention was given to the role of occupational therapists and psychologists, recognizing their central contribution to intervention and support for children with ADHD.

2.3. PRISMA Flow

The review process adhered to the PRISMA framework. The flow of information is summarized in the PRISMA diagram (

Figure 1), which illustrates the number of studies identified, screened, assessed for eligibility, and finally included in the review. The diagram also records the number of studies excluded at each stage, together with justifications.

3. Language Development

Language skills allow individuals to use their language accurately by conveying meaning, a condition that contributes to its production and comprehension (Méndez-Freije et al., 2024). According to Méndez-Freije et al. (2024), this ability is essential for personal and academic development. Research also shows that in children with ADHD, language skills are often impaired (Korrel et al., 2017; Jepsen et al., 2024), affecting comprehension and communication in everyday contexts. The acquisition of language skills is critical for human communication and development, as it affects the individual on a personal, educational and professional level. Language skills are multidimensional since they are related to an individual's ability to listen, speak, read, write, understand and use language in specific social and cultural contexts (Goldstein & Naglieri, 2014).

Phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics are the five key linguistic domains that are considered necessary for an individual to understand and use language in an effective way. The five domains work together for the individual to form a dynamic and unified linguistic whole in order to communicate and understand, both at the level of spoken and written language, the people with whom he/she interacts (Koutsoftas, 2013).

3.1. Phonology

More specifically, regarding the five basic linguistic structures, phonology focuses on the abstract systems and phonological rules through which individuals shape the pronunciation of words. It forms the basis for morphology and syntax, as phonological constraints cannot affect the form and order of words (Bickel et al., 2014). According to Korrel et al. (2017), in children with ADHD, phonological processing is often compromised, particularly in tasks requiring fine-grained manipulation of sounds, such as phoneme deletion, blending, and nonword repetition. These deficits are not typically due to articulation problems but rather to limitations in phonological working memory and processing speed. For example, children with ADHD may struggle to hold multiple phonemes in mind simultaneously, resulting in slower or less accurate decoding of unfamiliar words.

Research by Chen et al. (2022) indicates that phonological weaknesses in ADHD are especially pronounced when co-occurring with reading disorders, suggesting an additive effect of attentional and language deficits. Moreover, neuroimaging studies (Gao et al., 2025) have shown that children with ADHD display reduced activation in left-hemisphere regions associated with phonological processing, such as the superior temporal gyrus and inferior frontal gyrus, especially under tasks that require sustained attention. This indicates that phonological deficits in ADHD are closely tied to domain-general cognitive resources rather than isolated linguistic systems.

Recent work by Vassiliu et al. (2023) highlights that interventions integrating phonological skill training with executive function supports—such as working memory scaffolding, attentional cues, and adaptive task pacing—lead to measurable improvements in decoding, reading fluency, and rapid naming speed. These findings suggest that phonological interventions for children with ADHD are most effective when they address both attentional and memory demands, rather than focusing solely on isolated sound discrimination exercises.

3.2. Morphology

Morphology deals with the structure of words and the rules of their formation, as it is shaped by phonological and syntactic constraints, while shapes can change the meaning and function of words through derivations and inflectional processes. Morphology affects semantics, as the morphological elements of a word cannot affect its meaning (Metsala, 2023). According to Bruce et al. (2016), ADHD-related morphological challenges are especially evident in contexts where words must be manipulated or integrated into complex syntactic structures. For example, producing past-tense forms in irregular verbs or deriving nouns from adjectives can impose additional cognitive load, revealing deficits in real-time morphological processing.

Research by Jepsen et al. (2024) suggests that early weaknesses in morphological awareness in children with ADHD can contribute to later difficulties in reading comprehension and written expression, particularly when executive function skills are underdeveloped. Furthermore, Cohen et al. (2017) found that morphological difficulties in ADHD often coexist with broader language processing deficits, impacting both academic and social communication.

Interventions targeting morphology in children with ADHD are most effective when individualized and EF-sensitive. As highlighted by Katsarou et al. (2024), techniques that scaffold attention, provide repetitive practice in meaningful contexts, and break down complex morphological rules into smaller steps can significantly improve both accuracy and retention. Integrating morphological exercises with narrative or reading activities further enhances generalization, supporting both language comprehension and written expression (Kovalčíková et al., 2024).

3.3. Syntax

Syntax focuses on the structure of sentences and the rules that determine how words are combined to form phrases and sentences. This system connects morphology and semantics, since it determines the relationship between words and their interpretation within a sentence. Syntax has been found to be related to morphology and semantics, as grammatical structure directly affects the semantic interpretation of a sentence. In addition, it can be influenced by morphological processes, such as rhythm and intonation, which affect the structure of sentences.

According to Massoodi et al. (2025), in children with ADHD, syntactic processing can be particularly challenging when sentences involve complex or embedded structures, such as relative clauses, passives, or center-embedded constructions. Research indicates that these difficulties often arise not from a primary syntactic deficit but from the interaction between syntactic complexity and domain-general executive functions, such as working memory, inhibitory control, and attentional allocation (Soto et al., 2021). Jepsen et al. (2022) further support this, showing that ADHD children may correctly apply syntactic rules in simpler contexts but struggle when maintaining multiple elements in memory or when suppressing competing interpretations is required.

Cross-linguistic evidence, as reported by Massoodi et al. (2025), illustrates that syntactic vulnerabilities in ADHD are modulated by language-specific properties. For instance, studies in Persian and other morphologically rich languages show that ADHD children exhibit greater difficulties in processing syntactic agreement and hierarchical embedding compared to typically developing peers, highlighting the cognitive load imposed by complex morphosyntactic integration. Similarly, Chen et al. (2022) found that sentence comprehension is frequently impaired when tasks demand integration of multiple clauses or rapid parsing of ambiguous structures, demonstrating that syntax in ADHD is highly sensitive to attentional and processing constraints.

3.4. Semantics

Semantics refers to the study of the meaning of words, phrases, and sentences, focusing on the way concepts are organized at the linguistic level and how their meaning is conveyed through grammatical and lexical elements. It has been found that semantics interacts closely with morphology and syntax, since semantic categories determine how morphemes and syntactic structures are used to convey specific meanings (Britannica, 2025). According to Cohen et al. (2017), children with ADHD often experience challenges in semantic organization that influence how they process and interpret linguistic meaning in context.

In children with ADHD, semantic processing can be affected, particularly in tasks requiring rapid lexical access, integration of meaning across sentences, or inference-making. Jepsen et al. (2022) observed that these difficulties often emerge not from a lack of knowledge of word meanings but from deficits in attention, working memory, or executive control, which can slow semantic retrieval or reduce the efficiency of integrating information across sentences or discourse. Vassiliu et al. (2023) further highlight that this leads to incomplete understanding, vague or imprecise expression, and reduced narrative coherence in everyday communication.

Interventions that support semantic development in ADHD often combine rich lexical instruction with scaffolds for executive function. Studies by Katsarou et al. (2024) show that strategies such as explicit teaching of word meanings, semantic mapping, repeated exposure in context, and the use of visual organizers can improve both vocabulary depth and comprehension. Additionally, Docking, Munro, & Cordier (2013) emphasize that integrating semantic-focused activities with attentional supports—like chunking or guided practice—further enhances learning outcomes, especially in children who show overlapping language and attentional weaknesses.

3.5. Pragmatics

Finally, pragmatics focuses on the way language is used in different communicative contexts and specifically on how speakers adapt their linguistic production, depending on the context, social conditions and relationships between interlocutors. It has been found that pragmatics interact with syntax and semantics, as linguistic expressions acquire dif-ferent meanings depending on their environment (Deppermann, 2011).

Children who have well-developed language skills tend to develop better interper-sonal relationships, as well as a greater ability to express their thoughts and feelings. Together, the acquisition of language skills has been linked to levels of self-esteem and in-dependence. Also, children with well-developed language skills tend to perform better in school and cope with learning challenges with greater ease (Richards & Rodgers, 2021; Hall & Ellis, 2022). At the same time, children who have developed language skills are fa-cilitated in terms of social inclusion, resulting in a higher level of psychological well-being and a reduced risk of developing anxiety (Lee, 2021).

It has been found that, particularly in the early developmental stages, language de-velopment has a significant impact on an individual's cognitive and social progress. The challenges that children may face in acquiring language skills due to neurodevelopmental disorders have been found to affect both their academic performance and their social in-teractions (Parks et al., 2023; Riad et al., 2023).

4. ADHD and Language Development

ADHD often affects children's language development, as it has been found that children with ADHD manifest various difficulties in understanding and using language, from delayed vocabulary development to problems in producing coherent and organized speech (Stanford & Delage, 2021; Redmond, 2016). Specifically, as shown by Goldstein & Naglieri (2014), these challenges reflect the multidimensional nature of language skills, including phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics.

Although the language difficulties experienced by children with ADHD are independent of their cognitive abilities (Cohen et al., 2017), they nevertheless often face barriers related to expression, comprehension, language pragmatics (Stanford et al., 2020), and morphosyntactic difficulties, resulting in many barriers to language acquisition (Stanford & Delage, 2020; Vassiliou et al., 2023). Research by Long (2024) further indicates that co-occurring reading disorders intensify these deficits, pointing to an additive effect of attentional and language challenges.

More specifically, research has shown that the pragmatic deficits exhibited by children with ADHD are often interconnected with the language challenges they face, which in turn are related to both social interactions and cognitive functioning (Hanna, 2023; Kapnoula et al., 2024). As highlighted by Parks et al. (2023), early pragmatic difficulties can have long-term impacts on social development and psychological well-being. At the same time, the barriers that these children present in terms of executive functions do not allow them to interact effectively in various forms of language behavior, such as, for example, dialogue and storytelling (Katsarou, 2023).

Research suggests that 35% of children with ADHD have significant difficulties in maintaining visual contact and understanding social cues, resulting in a negative impact on their pragmatic and language skills (El Sady et al., 2013). According to Kessler & Ikuta (2023), these difficulties are compounded by deficits in attentional control and phonological processing, limiting the integration of language components. At the same time, research has shown that children with ADHD have significant deficits in morphosyntactic as well as pragmatic levels (Zambrano-Sánchez et al., 2023; Soto et al., 2021; Massoodi et al., 2025).

According to Redmond & Ash (2014), children with ADHD have a high level of language difficulties compared to their peers without the disorder. These difficulties include delays in vocabulary development, comprehension, and language use, problems with storytelling, and social communication. The barriers impede the child's ability to develop coherent and organized speech, resulting in significantly affected academic performance (Bruce et al., 2016), and they often experience social rejection (Sciberras et al., 2014).

It is estimated that approximately 30% of children with ADHD have significant difficulties in reading (Rocco, et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022), and 40% in phonological processing (Jepsen, et al., 2022; Gooch et al., 2016). The difficulties are particularly pronounced in the case of children who fall into the combined ADHD-Y type (Gooch et al., 2016; Rapport et al., 2020). These challenges are further compounded since children with ADHD-Y are characterized by a poor vocabulary, have difficulty learning new words, use simple sentence structures, omit sentence elements, avoid complex expressions, and are characterized by a slow speech rate. The persistent nature of the aforementioned difficulties is exacerbated by the underlying symptoms that children with ADHD exhibit, in particular attention span and executive function deficits (Gooch, et al., 2016; Parsons et al., 2017). Attentional distraction prevents children with ADHD from mastering language skills as they are unable to effectively observe and imitate speech patterns from the social context in which they operate (Gooch et al., 2016). Furthermore, children with ADHD have difficulty pronouncing and recognizing phonemes accurately, resulting in barriers at the level of word pronunciation and issues related to lexical rhythm, a condition associated with sound processing problems and working memory deficits (Parsons et al., 2017).

Children with ADHD also face many challenges in terms of written language, as they cannot easily express their knowledge, thoughts, perceptions and feelings. 45% of children with ADHD manifest significant difficulties in written expression, with texts characterized by brevity and limited coherence (Tahıllıoğlu et al., 2024; Papaeliou, 2012; Kyriacou & Köder, 2024). These difficulties are further exacerbated by attention deficits, as children with ADHD find it difficult to follow complex instructions and complete academic tasks, resulting in a limitation of their academic productivity and, by extension, their school performance (Miller et al., 2024; Sarid et al., 2024).

4.1. The Difficulty of Applying Differential Diagnosis in the Assessment of ADHD

The differential diagnosis in the case of ADHD requires a multidimensional assessment, which includes the historical, psychological and educational history of the assessee, as well as clinical interviews. (Bélanger et al., 2018; Redmond & Ash, 2014). However, the differential diagnosis is faced with a multitude of challenges, such as comorbidity and overlapping symptoms (Cohen et al., 2017; Koyuncu et al., 2022). Specifically, children with ADHD show a high degree of comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders, which makes it difficult to distinguish between them (Marangoni et al., 2015; Bélanger et al., 2018; Hanna, 2023). It has been found that 70% of children and 50% of adults with ADHD simultaneously suffer from one of the following disorders, such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, oppositional defiant disorder, autism spectrum disorder, learning disabilities, sleep disorders, or depression (Bélanger et al., 2018).

Also, one of the biggest obstacles to diagnosing ADHD is that many of its characteristics overlap with other disorders. For example, the impulsivity and hyperactivity of ADHD are often confused with mania in the case of bipolar disorder. (Marangoni et al., 2015). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder can also occur in depression or anxiety disorders (Koyuncu et al., 2022). At the same time, children with ADHD have difficulty regulating their emotions, and as individuals they also experience mood disorders (Taurines et al., 2010). Accordingly, social interaction problems have been found to occur in both children with ADHD and children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (Baleyte et al., 2022).

In addition to the above, the differential diagnosis is faced with a lack of objective biological markers, as there are no hematological or neuroimaging tests that can diagnose the disorder with certainty (Antshel & Russo, 2019). At the same time, age differences are observed as the symptoms of the disorder manifest differently in children and adults with ADHD (Bélanger et al., 2018). For example, adults show more inattention than hyperactivity. At the same time, the differential diagnosis can be influenced by cultural factors, such as the way in which the disorder manifests itself depending on the cultural context (Schmitt et al., 2010).

In order to overcome the aforementioned obstacles, the scientific community promotes the use of multiple diagnostic tools, such as structured interviews, assessment questionnaires and analysis of behavior in different settings, in order to minimize the risk of any misdiagnosis (Wu et al., 2023; Sibley et al., 2016; Redmond & Ash, 2014). At the same time, newer research suggests differentiated diagnostic protocols that consider the neurobiological and psychological parameters of each individual (Bélanger et al., 2018; Kessler & Ikuta, 2023; Kapnoula et al., 2024). For example, the use of highly accurate tools such as the Conners Rating Scale and Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Scale is recommended. (Wu et al., 2023). At the same time, it is recommended to conduct a neuropsychological assessment to identify the patterns of executive function that differ between ADHD, anxiety and mood disorders (Sparrow & Erhardt, 2014). Finally, the scientific community suggests observing the assessed in different settings (home, school, work) (Sibley et al., 2016).

It is understood from the above that the differential diagnosis of ADHD is a complex process due to the morbidity and overlap of symptoms with other disorders. Specialists must apply multiple diagnostic approaches to ensure an accurate and reliable diagnosis (Koyuncu et al., 2022; Choi et al., 2022).

4.2. Diagnostic Challenges in ADHD Due to Comorbidity and Symptom Overlap

Diagnosing Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is often complicated by the high rate of comorbid conditions. Recent studies indicate that up to 80% of adults with ADHD present with one or more additional disorders, including anxiety, depression, substance use disorders, and oppositional defiant disorder (Choi et al., 2022; Verywell Mind, 2022). This overlap of symptoms—such as inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity—makes it difficult to distinguish ADHD from other conditions, particularly when the inattentive presentation mimics anxiety or depressive disorders (Katzman et al., 2017; Young & Goodman, 2016). The co-occurrence of multiple disorders can also exacerbate functional impairments, leading to more pronounced academic, social, and behavioral difficulties (Biederman et al., 2017; Kessler et al., 2015). Additionally, evolving diagnostic criteria, such as those in the DSM-5, allow for dual diagnoses, further complicating differentiation between primary and secondary symptomatology (Slobodin et al., 2018; Faraone et al., 2015). Accurate identification requires comprehensive assessment strategies, including multi-informant behavioral observations, standardized rating scales, and consideration of developmental history (Kessler et al., 2015; Sibley et al., 2016; Katsarou, 2023). In sum, the substantial symptom overlaps and frequent comorbidities necessitate a careful, nuanced approach to ADHD diagnosis to ensure that treatment plans address all relevant conditions and minimize misdiagnosis or under-identification (Katzman et al., 2017; Young & Goodman, 2016; Slobodin et al., 2018).

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

5. Interventions to Improve Language Development

Considering the diverse effects of ADHD on children's language development, targeted interventions are needed to improve the level of language skills while addressing the specific needs of each child (Katsarou et al., 2024).

More specifically, it is necessary to implement interventions that focus on enhancing the phonological awareness of children with ADHD, due to their difficulties in recognizing letters and sounds, which directly affects the level of their reading skills (Johnson & Tyler, 2020; Justice, 2006; Vassiliou et al., 2023). Targeted intervention at the level of phonological processing leads to significant improvements in children's reading ability (Taylor et al., 2021). At the same time, engaging in programs that incorporate tasks that address vowel and consonant recognition and management, as well as understanding syllabic word structure, has demonstrated highly positive results in the language improvement of children with ADHD (Johnson & Tyler, 2020). The exercises help children to better understand how words are composed of sounds, thereby improving both their reading ability and language fluency. At the same time, educational approaches that focus on direct teaching of cognitive strategies, such as phonetic decoding and the use of mnemonic sound rules that contribute to memorization, have been found to help the developmental progress of children with ADHD (Taylor et al., 2021).

Interventions that focus on the executive functions of children with ADHD are also considered important because of the deficits in working memory, attention and organisation that have a negative impact on language development and academic performance (Barkley, 2012). It has been found that children who participate in programs that focus on addressing challenges through engagement in targeted activities significantly improve their academic performance (Diamond, 2013).

Also, engaging children with ADHD in activities that improve working memory and attention skills, such as memory games and multitasking exercises, positively contributes to managing language demands (Goldstein & Naglieri, 2014). Teaching children with ADHD to organize using visual reminders and journals has been found to be instrumental in helping them to plan and complete tasks more efficiently (Goldstein & Naglieri, 2014; Dovis et al., 2015). Concomitantly, incorporating interventions into the school environment, such as providing regular feedback and teaching learning strategies that involve executive functions, has been found to contribute to self-regulation and academic performance of children with ADHD (Dovis et al., 2015).

Also, interventions that focus on speech and language therapy are considered crucial factors to improve children's oral and written expression as well as language comprehension (Cordier et al., 2019). Programs that focus on enhancing storytelling and organizing ideas can help children with ADHD develop coherent and language structures (Westby, 2012; Rapport, et al., 2020).

The process helps to improve the ability of the individuals involved to structure and express their thoughts clearly, enhance language fluency and narrative ability, elements that are particularly important for academic success and social interaction (Justice, 2006). At the same time, the incorporation of individualized programs that provide children with ADHD the opportunity to practice using language in real-life settings has been found to be particularly effective in improving the programmes include word reading, spelling exercises and practices that develop children's ability to follow directions and answer questions (Gillam et al., 2008).

Often the use of technology is an important intervention to improve the written expression of children with ADHD, as it has been found that technological advances can address a variety of challenges related to spelling, grammar and language structure issues. Word processing programs with spelling and grammar checking capabilities help children with ADHD to identify and correct their errors while enhancing the quality of written work (Peterson-Karlan, 2011; Maleki et al., 2024; Calderoni & Coghill, 2024).

Similarly, voice recognition software programs allow children with ADHD to dictate their thoughts orally and convert them into written language. This technique is considered particularly beneficial for children who have difficulties with fine motor skills or difficulties with writing speed (Peterson-Karlan, 2011; Maleki et al., 2024; Calderoni & Coghill, 2024). The use of tools such as the above-mentioned ones reduces the fatigue and frustration that can occur during written production, allowing children with ADHD to focus on the content and structure of their text (Maleki et al, 2024; Calderoni & Coghill, 2024). Parallel software programs such as graphic organizers and text design tools, contribute to the organization of ideas and achieving better coherence of writing (MacArthur et al., 2015). Research has shown that integrating technology tools into the school context contributes to significant improvements in the written expression and self-confidence of children with ADHD. Also, dividing written tasks into smaller, more manageable chunks can also help maintain the concentration and productivity of children with ADHD, resulting in significant improvements in the quality and coherence of written language (Tahıllıoğlu et al, 2024).

Social skills training is a particularly effective intervention for children with ADHD, which, among other things, helps them effectively deal with difficulties in understanding informal communication rules, such as taking turns in speaking, maintaining eye contact, and understanding the emotions and intentions of other people (Landau & Moore, 2015; Cordier et al., 2019; Hanna, 2023). Special educational programs related to social skills focus on strengthening pragmatic language, which includes the use of language in various social contexts, as well as the understanding of verbal communication elements, such as facial expressions and tone of voice (Landau & Moore, 2015). At the same time, by incorporating exercises that enhance the understanding of social signals, the level of linguistic exchange is improved, allowing children with ADHD to participate in conversations with greater comfort and clarity. Improving social skills helps to cultivate verbal comprehension and overall communication in children with ADHD (Cordier et al., 2019).

5.1. The Role of the Occupational Therapist in Improving the Language Development of Children with ADHD

Considering that ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder, apart from language development, it affects the individual in many ways in terms of communication skills, language structures and understanding of social skills (Watroba et al., 2023; Katsarou et al., 2024; Hanna, 2023; Green et al., 2014). It is therefore clear that the occupational therapist plays a crucial role, as through his or her specialised interventions, he or she enhances not only language skills but also the communicative and social interaction of these children (Watroba et al., 2023).

By utilizing techniques that promote language and development through activities, occupational therapists work to enhance executive function, concentration and social interaction (Green et al., 2014). More specifically, by engaging children with ADHD in playful interventions, occupational therapists teach them to express themselves in the correct way, enrich their vocabulary and understand a plethora of social and communicative cues (Docking et al., 2013). According to research results, it had been found that engaging children with ADHD in role-playing games and board games with rules improves their level of concentration and communication skills (Wilkes-Gillan et al., 2017). Also, by designing activities that involve interaction with peers, occupational therapists help these children improve their language skills through social interaction (Docking et al., 2013).

At the same time, occupational therapy has emerged as a particularly useful approach at the sensory processing level, since it helps the sensory development of children with ADHD, resulting in their language development, since it is interconnected with their ability to concentrate and with their understanding of social cues (Cordier et al., 2017; Barkley, 2012; Katsarou et al., 2024). By applying techniques that include the use of movement and touch to improve language skills, the occupational therapist helps children to connect verbal and non-verbal communication through engaging them in motor experiences (Wilkes et al., 2011; Dabiri Golchin et al., 2021).

At the same time, occupational therapy has been shown to be particularly important for the development of executive functions such as self-regulation, working memory and attention, which are considered essential for children with ADHD to organise their linguistic expression, as they have difficulty maintaining a conversation, remembering instructions or organising their speech coherently. The occupational therapist helps to develop these skills by engaging children in structured activities, such as learning planning strategies and using virtual aids (Cordier et al., 2017; Katsarou et al., 2024).

5.2. The Role of the Psychologist in Improving the Language Development of Children with ADHD

As children with ADHD struggle with language structure and organization, both their written and oral communication is affected (Staikova et al., 2013). To mitigate the difficulties, psychologists make use of cognitive behavioral therapy techniques and methods that help to enhance working memory and concentration (Mohebbi, 2023; Jepsen et al., 2024).

At the same time, psychologists also help to improve pragmatic language, i.e. the ability to use language in social situations, conditions in which children with ADHD have significant deficits (Staikova et al., 2013). Strengthening emotional awareness as well as recognition of social cues can be systematically enhanced through psychological support for children with ADHD (Cohen et al., 2017).

The role of the school and family context in enhancing the language development of children with ADHD is also considered important. The aforementioned goal is achieved through school psychologists, who work with the educational community to create individualised educational interventions. In addition, school psychologists provide advice to parents on how to support children's language development at home (Sciberras et al., 2014)

Finally, psychoeducation helps children with ADHD to understand their difficulties and develop coping strategies on their own. Teaching children to use self-regulation techniques. such as slowing down their thinking before speaking and building confidence in their communication skills, they have been able to significantly improve verbal expression and comprehension (Lincă, 2018; Powell et al, 2022; Yan & Cheng, 2022). By applying individualized intervention programs, psychologists practiced children in language self-regulation strategies, such as using inner speech and step-by-step formulation of their plans before oral expression (Pisacco et al., 2018). At the same time, self-regulation interventions implemented within the educational environment help to improve concentration and working memory of children with ADHD, enhancing their comprehension and speech production skills (Sökmen & Karaca, 2023).

Psychologists therefore play an essential role in developing the language skills of children with ADHD through social and educational interventions. By enhancing executive function, social communication and collaboration with other specialists, for example occupational therapists, psychologists help to improve children's level of everyday communication as well as academic performance (Dovis et al., 2015).

6. Discussion

The present literature review demonstrated the close relationship between ADHD and language development difficulties. As found, this is a complex relationship, which is due to the challenges that children with ADHD face due to their symptoms. As demonstrated, the main areas of language difficulties experienced by children with ADHD are phonological awareness, pragmatic understanding, executive function and written expression (Méndez-Freije et al., 2024). The difficulties are exacerbated by the deficits in attention, working memory and executive skills exhibited by children with ADHD (Korrel et al., 2017).

The present literature review demonstrated the important role of occupational therapists and psychologists in mitigating the difficulties that children with ADHD present in language development. It also established the importance of implementing targeted, interventions aimed at improving these skills can bring about significant positive outcomes for children with ADHD (Wilkes-Gillan et al., 2017). Specifically, interventions that focus on enhancing phonological awareness, through phonemic awareness training, lead to improved reading skills (Chang et al., 2020). At the same time, speech and language interventions contribute to oral and written expression, focusing specifically on improving the level of storytelling and speech structure of children with ADHD (Martins et al., 2020). Interventions that enhance executive functions, such as working memory and speech organization, improve children's ability to manage school demands, while the use of technological tools and social skills training enhance communication skills and social interactions of children with ADHD (Nejati et al., 2023).

The above demonstrates that the implementation of integrated cognitive interventions is crucial in supporting children with ADHD (Chevrier & Schachar, 2020). These interventions, when individualised and combining educational, therapeutic and technological strategies, help to improve children's language development, communication and academic performance (Pillay & Govender, 2019). A multidisciplinary approach and collaboration between teachers, parents and therapists is recommended to fully support people with ADHD and enhance their cognitive and language skills (Barkley, 2015).

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, D.V.K. and A.A..; methodology D.V.K..; analysis, D.V.K. and A.A.: investigation, D.V.K. and A.A..; writing—original draft preparation, D.V.K...; writing—review and editing, A.A..; supervision, D.VK.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al-Dakroury, W. (2018). Speech and Language Disorders in ADHD. Abnormal and Behavioural Psychology, (1), 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Antshel, K. M., & Russo, N. (2019). Autism spectrum disorders and ADHD: Overlapping phenomenology, diagnostic issues, and treatment considerations. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(5), 34. [CrossRef]

- Baleyte, J. M., Hours, C., & Recasens, C. (2022). ASD and ADHD comorbidity: What are we talking about? Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 837424. [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R. A. (2015). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

- Bélanger, S. A., Andrews, D., & Gray, C., Korczak, D. (2018). ADHD in children and youth: Part 1—Etiology, diagnosis, and comorbidity. Paediatrics & Child Health, 23(7), 447-453. [CrossRef]

- Bickel, B., Collier, K., & van Schaik, C. P. (2014). Language evolution: Syntax before phonology? Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 281(1788), 20140263. [CrossRef]

- Biederman, J., Petty, C. R., & Faraone, S. V. (2017). Comorbidity of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders: An analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68(2), 1-10.

- Booij, G. & Audring, J. (2017). Construction morphology and the parallel architecture of grammar. Cognitive Science, 41(S4), 898–923. [CrossRef]

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2025). Morphology. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/linguistics/Morphology.

- Bruce, B., Thernlund, G., & Nettelbladt, U. (2016). ADHD and language impairment: A study of the relationship between language deficits and symptoms of ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(7), 587-595. [CrossRef]

- Calderoni, S., & Coghill, D. (2024). Advancements and challenges in autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 3, 1372911. [CrossRef]

- Chang S. Yang L. Wang Y. Faraone S. V. (2020). Shared polygenic risk for ADHD, executive dysfunction and other psychiatric disorders. Translational Psychiatry, 10(1), 182. 10.1038/s41398-020-00872-932518222.

- Chen, Y., Tsao, F. M., Liu, H. M., & Huang, Y. J. (2022). Distinctive patterns of language and executive functions contributing to reading development in Chinese-speaking children with ADHD. Reading and Writing, 37, 1011–1034.

- Chevrier A. Schachar R. J. (2020). BOLD differences normally attributed to inhibitory control predict symptoms, not task-directed inhibitory control in ADHD. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 12(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s11689-020-09311-832085698.

- Choi, S. H., Lee, S. H., & Kim, B. N. (2022). Treating ADHD and Anxiety Comorbidity in Adults Using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 150, 1-8.

- Cohen, N. J., Vallance, D. D., Barwick, M. A., Im, N., Menna, R., Horodezky, N. B., & Isaacson, L. (2017). Language, social cognitive processing, and behavioral characteristics of psychiatrically disturbed children with previously identified and unsuspected language impairments. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 345-353.

- Cordier, R., Munro, N., Wilkes-Gillan, S., Ling, L., Docking, K., & Pearce, W. (2016). Evaluating the pragmatic language skills of children with ADHD and typically developing playmates following a pilot parent-delivered play-based intervention. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64(1), 11–23. [CrossRef]

- Cordier, R., Munro, N., Wilkes-Gillan, S., & Speyer, R. (2019). Applying Item Response Theory (IRT) Modeling to an Observational Measure of Childhood Pragmatics: The Pragmatics Observational Measure-2. Front Psychol, 28:10:408. eCollection 2019. [CrossRef]

-

Dabiri Golchin, M., Mirzaie, H., & Hosseini, S. A. (2021). Effect of occupational therapy interventions on improving play

performance in children with ADHD: A systematic review. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 19(3), 221-230. .

- Deppermann, A. (2011). “Pragmatics and grammar”. In W. Bublitz & N. R. Norrick (Eds.), Foundations of Pragmatics (pp. 425–456). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135-168.

- Dovis, S., Van der Oord, S., Wiers, R. W., & Prins, P. J. M. (2015). Improving executive functioning in children with ADHD: Training multiple executive functions within the context of a computer game. a randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial. PLoS One, 10(4), e0121651. [CrossRef]

- Dovis, S., Maric, M., Prins, P. J. M., & Van der Oord, S. (2019). Does executive function capacity moderate the outcome of executive function training in children with ADHD? Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11(4), 335–344. [CrossRef]

- Docking, K., Munro, N., & Cordier, R. (2013). Examining the language skills of children with ADHD following a play-based intervention. Sage Journals, 29(3). [CrossRef]

- El Sady, S. R., Nabeih, A. A., Mostafa, E. M., & Sadek, A. A. (2013). Language impairment in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in preschool children. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics, 14, 383–390.

- Faraone, S. V., & Larsson, H. (2015). Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, 20(3), 1-10.

- Gao, Z., Duberg, K., Warren, S. L., Zheng, L., Hinshaw, S. P., Menon, V., & Cai, W. (2025). Reduced temporal and spatial stability of neural activity patterns predict cognitive control deficits in children with ADHD. Nature Communications, 16(1), 2346. [CrossRef]

- Gillam, R. B., et al. (2008). Improving narrative skills in children with communication impairments. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 10(3), 192-209. [CrossRef]

- Green, B. C., & Johnson, K. A. (2014). Pragmatic language difficulties in children with hyperactivity and attention problems: An integrated review. Wiley Online Library, 49(1), 15-29.

- Goldstein, S., & Naglieri, J. A. (2014). Handbook of executive functioning. Springer.

- Gooch, D., Thompson, P., Nash, H. M., Snowling, M. J., & Hulme, C. (2016). The development of executive function and language skills in the early school years. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57, 180–187. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, A. P., Petscher, Y., & Tock, J. (2019). Morphological supports: Investigating differences in how morphological knowledge supports reading comprehension for middle school students with limited reading vocabulary. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51(3), 589–602.

- Hall, L., & Ellis, A. (2022). Language proficiency and academic success. Educational Psychology, 53(1), 10-25.

- Hanna, C. H. F. (2023). Phonic faces as a method for improving decoding for children with persistent decoding deficits (Ph.D. thesis). Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College, Baton Rouge, LA, USA.

- Jepsen, I. B., Hougaard, E., Matthiesen, S. T., & Lambek, R. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of narrative language abilities in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50, 737–751. [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, I. B., Brynskov, C., & Thomsen, P. H. (2024). The role of language in the social and academic functioning of children with ADHD. Sage Journals, 28(12). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M., & Tyler, K. (2020). Effective interventions for phonological processing in children with ADHD. Child Development, 91(4), e935-e950.

- Justice, L. M. (2006). Evidence-based practice, response to intervention, and the prevention of reading difficulties. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37(4), 284-297. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2006/033).

- Kapnoula, E. C., Jevtović, M., & Magnuson, J. S. (2024). Spoken word recognition: A focus on plasticity. Annual Review of Linguistics, 10, 233–256.

- Katsarou, D. (2019). Neurodevelopmental Perspectives in Education: The necessity for implementing innovating teaching techniques in order to improve PA. Oblomov Guidelines (pp 29-32). University of Thessaly.

- Katsarou, D. (2023). Developmental language disorders in childhood and adolescence. IGI Global: New York, NY, USA.

- Katsarou D. Nikolaou E. Stamatis P. (2023). Is coteaching an effective way of including children with autism? The Greek parallel coteaching as an example: Issues and Concerns. In EfthymiouE. (Ed.), Inclusive Phygital Learning Approaches and Strategies For Students with Special Needs (pp. 189–197). IGI Global. 10.4018/978-1-6684-8504-0.ch009.

- Katsarou, D. V., Efthymiou, E., & Kougioumtzis, G. A. (2024). Identifying language development in children with ADHD: Differential challenges, interventions, and collaborative strategies. Children, 11(7), 841. [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, D. (2024). Neurocognitive Profile in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Implementation of New Goals in Different Settings: In book: Exploring Cognitive and Psychosocial Dynamics Across Childhood and Adolescence (pp.145-160). [CrossRef]

- Katzman, M. A., Bilkey, T. S., & Stewart, S. H. (2017). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbidity: A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(1), e1-e9.

- Kessler, P. B., & Ikuta, T. (2023). Pragmatic deficits in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 27, 812–821. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., & Barkley, R. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(9), 1-8.

- Kiefer, F. (2017). “Morphology and pragmatics”. In Spencer, A. & Zwicky, A. (Eds.), The Handbook of Morphology (pp. 365–380). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Korrel, H., Mueller, K. L., Silk, T., Anderson, V., & Sciberras, E. (2017). Research review: Language problems in children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – a systematic meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 640–654. [CrossRef]

- Koutsoftas, A. D. (2013). School–age language development: Application of the five domains of language across four modalities. In Capone-Singleton, N., & Shulman, B. B. (Eds.), Language development: Foundations, processes, and clinical applications (pp. 215–229). Jones & Bartlett Learning: Seattle, WA, USA.

- Kovalčíková, I., Veerbeek, J., Vogelaar, B., Klimovič, M., & Gogová, E. (2024). Tracing progress in children’s executive functioning and language abilities related to reading comprehension via ExeFun-READ intervention. Education Sciences, 14(3), 237. [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, A., Ayan, T., İnce Guliyev, E., & Erbilgin, S. (2022). ADHD and anxiety disorder comorbidity in children and adults: Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Current Psychiatry Reports, 24(6), 511–523. [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, M., & Köder, F. (2023). Exploring the pragmatic competence of adults with ADHD: An eye-tracking reading study on the processing of irony. OSF Registries, 7, 1–12.

- Landau, S., & Moore, L. A. (2015). Social skill development in children with ADHD. Journal of Developmental Psychology, 45(3), 233-245.

- Lee, C. (2021). Social inclusion and language skills. Community Psychology, 49(4), 438-460. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. S., Lim, N., & Guerzhoy, M. (2024). Detecting a Proxy for Potential Comorbid ADHD in People Reporting Anxiety Symptoms from Social Media Data. arXiv. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.05561.

- Lincă, F. I. (2018). Solutions for improving the symptomatology of the child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Romanian Journal of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, 5(3-4), 1-23.

- Long, D. (2024, October 17). ADHD and reading disability often occur together, study finds. University of Colorado Boulder. https://www.colorado.edu/asmagazine/2024/10/17/adhd-and-reading-disability-often-occur-together-study-finds.

- MacArthur, C. A., Graham, S., & Fitzgerald, J. (2015). Handbook of writing research. Guilford Press.

- Maleki, S., Hassanzadeh, S., Rostami, R., & Pourkarimi, J. (2024). Design and effectiveness of a reading skills advancement program based on executive functions specifically for students with comorbid dyslexia and ADHD. Psychological Science, 23, 267–286.

- Massoodi, A., Ahmadi, A., Haghjou, H., Larimian, M., Mazandarani, M., Nikbakht, H.-A., Pascoe, M., Ahmadzadeh, S., & Koohestani, F. (2025). Syntax comprehension in Persian-speaking students with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry, 25(1), 390. [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, C., De Chiara, L., & Faedda, G. L. (2015). Bipolar disorder and ADHD: Comorbidity and diagnostic distinctions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(8), 60. [CrossRef]

- Martins, R., Ribeiro, M., Pastura, G., & Monteiro, M. (2020). Phonological remediation in schoolchildren with ADHD and dyslexia. Codas, 32(5):e20190086. [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Freije, I., Areces, D., & Rodríguez, C. (2024). Language skills in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and developmental language disorder: A systematic review. Children, 11(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Metsala, J. L. (2023). Longitudinal contributions of morphological awareness, listening comprehension, and early gains in word reading fluency to later word- and text-reading fluency. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1194879. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. J., Komanapalli, H., & Dunn, D. W. (2024). Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a patient with epilepsy: Staring down the challenge of inattention versus nonconvulsive seizures. Epilepsy & Behavior Reports, 25, 100651. [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, A. (2023). Optimising language learning for students with ADHD: Strategies for cultivating attentional mechanisms. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375295240_Optimising_Language_Learning_for_Students_with_ADHD_Strategies_for_Cultivating_Attentional_Mechanisms.

- Nejati, V., Derakhshan, Z., & Mohtasham, A. (2023). The effect of comprehensive working memory training on executive functions and behavioral symptoms in children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Asian journal of psychiatry, 81:103469. [CrossRef]

- Papaeliou, F. X. (2012). The development of language: Theoretical approaches and research evidence from typical and deviant language behavior. Papazisi: Athens, Greece.

- Parsons, L. Q., Cordier, R., Munro, N., Joosten, A., & Speyer, R. (2017). A systematic review of pragmatic language interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE, 12, e0172242. [CrossRef]

- Parks, K. M., Hannah, K. E., Moreau, C. N., Brainin, L., & Joanisse, M. F. (2023). Language abilities in children and adolescents with DLD and ADHD: A scoping review. Journal of Communication Disorders, 106, 106381. [CrossRef]

- Patil, S., Apare, R., Borhade, R., & Mahalle, P. (2024). Intelligent approaches for early prediction of learning disabilities in children using learning patterns: A survey and discussion. Journal of Autonomous Intelligence, 7, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Peterson-Karlan, G. (2011). Technology to support writing by students with learning and academic disabilities: Recent research trends and findings. Assistive Technology Outcomes and Benefits, 7(1), 39-62.

- Pillay, J., & Govender, N. (2019). Enhancing executive functioning in children with ADHD: A systematic review of interventions. Journal of ADHD and Related Disorders, 8(3), 207–219. [CrossRef]

- Pisacco, N. M. T., Sperafico, Y. L. S., & Enricone, J. R. B. (2018). Metacognitive interventions in text production and working memory in students with ADHD. SciELO. https://www.scielo.br/j/prc/a/h3HrCF7mnf6YfqC4JJzp3qL/?lang=en.

- Powell, L. A., Parker, J., & Weighall, A. (2022). Psychoeducation intervention effectiveness to improve social skills in young people with ADHD: A meta-analysis. Sage Journals. [CrossRef]

- Rapport, M. D., Eckrich, S. J., Calub, C., & Friedman, L. M. (2020). Executive function training for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In The Clinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment of Childhood Learning and Attention Problems (pp. 171–196). Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Riad, R., Allodi, M. W., Siljehag, E., & Bölte, S. (2023). Language skills and well-being in early childhood education and care: A cross-sectional exploration in a Swedish context. Frontiers in Education, 8, 963180. [CrossRef]

- Rice, M., Erbeli, F., & Wijekumar, K. (2023). Phonemic awareness: Evidence-based instruction for students in need of intervention. Intervention in School and Clinic. [CrossRef]

- Redmond, S. M. (2016). Markers, models, and measurement error: Exploring the links between attention deficits and language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59, 62–71. [CrossRef]

- Redmond, S. M., & Ash, A. C. (2014). Language impairment and social functioning in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(3), 235–247. [CrossRef]

- Richards, K. A., & Rodgers, T. S. (2021). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambrige University Press.

- Rocco, I., Corso, B., Bonati, M., & Minicuci, N. (2021). Time of onset and/or diagnosis of ADHD in European children: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 21, 575. [CrossRef]

- Rommelse, N., Buitelaar, J. K., & Hartman, C. A. (2016). Structural brain imaging correlates of ASD and ADHD across the lifespan: A hypothesis-generating review on developmental ASD–ADHD subtypes. Journal of Neural Transmission, 124(2), 259–271. [CrossRef]

- Salari, N., Khazaie, H., & Rezaei, N. (2023). Prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Its Comorbidities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 27(5), 1-10.

- Sciberras, E., Mueller, K. L., Efron, D., Bisset, M., Anderson, V., Schilpzand, E. J., Jongeling, B., & Nicholson, J. M. (2014). Language skills in children with ADHD: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Attention Disorders, 18(4), 277-294. [CrossRef]

- Sibley, M. H., Mitchell, J. T., & Becker, S. P. (2016). Method of adult diagnosis influences estimated persistence of childhood ADHD: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(12), 1157–1165. [CrossRef]

- Slobodin, O., & Levy, S. (2018). ADHD and comorbidity: A review of the literature. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22(6), 1-9.

- Sökmen, Z., & Karaca, S. (2023). Self-regulation based cognitive psychoeducation program on emotion regulation and self-efficacy in children diagnosed with ADHD. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 44(June), 122-128.

- Soto, E. F., Irwin, L. N., Chan, E. S. M., Spiegel, J. A., & Kofler, M. J. (2021). Executive functions and writing skills in children with and without ADHD. Neuropsychology, 35(8), 792–808. [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, E. P., & Erhardt, D. (2014). Essentials of ADHD assessment for children and adolescents. John Wiley & Sons.

- Staikova, E., Gomes, H., Tartter, V., McCabe, A., & Halperin, J. M. (2013). Pragmatic deficits and social impairment in children with ADHD. May, 54(12), 1275–1283. [CrossRef]

- Stanford, E., & Delage, H. (2020). Executive functions and morphosyntax: Distinguishing DLD from ADHD in French-speaking children. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 551824. [CrossRef]

- Stanford, E., & Delage, H. (2021). The contribution of visual and linguistic cues to the production of passives in ADHD and DLD: Evidence from thematic priming. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 37, 17–51. [CrossRef]

- Tahıllıoğlu, A., Bilaç, Ö., Erbaş, S., Barankoğlu Sevin, İ., Aydınlıoğlu, H. M., & Ercan, E. S. (2024). The association between cognitive disengagement syndrome and specific learning disorder in children and adolescents with ADHD. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 4, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Taurines, R., Schwenck, C., Westerwald, E., & Siniatchkin, M. (2012). ADHD and autism: Differential diagnosis or overlapping traits? A selective review. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 4(3), 115-139. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L., et al. (2021). Direct instruction of reading strategies: Improving literacy in children with ADHD. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 37(2), 155-174. [CrossRef]

- Thalheim, B. (2012). Syntax, semantics, and pragmatics of conceptual modelling. In R. M. K. G. F. Goossens & J. Z. Pan (Eds.), Natural Language Processing and Information Systems (pp. 1–15). Springer.

- Tirosh, E., & Cohen, A. (2017). Sentence comprehension and attention in children with ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(10), 1085–1093. [CrossRef]

- Vassiliu, C., Mouzaki, A., Antoniou, F., Ralli, A., Diamanti, V., Papaioannou, S., & Katsos, N. (2023). Development of structural and pragmatic language skills in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 44, 207–218.

- Verywell Mind. (2022). ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Verywell Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/understanding-and-treating-adhd-and-odd-6541410.

- Watroba, A., Luttinen, J., Lappalainen, P., Tolonen, J., Ruotsalainen, H. (2023). Effectiveness of School-Based Occupational Therapy Interventions on School Skills and Abilities Among Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity and Autism Spectrum Disorders: Systematic Review. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 17(2). [CrossRef]

- Westby, C. E. (2012). Assessing and developing narrative skills in children with communication difficulties. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 33(2), 112-124. [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, S., Cordier, R., Bundy, A., Docking, K., & Munro, N. (2011). A play-based intervention for children with ADHD: A pilot study. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58(4), 231–240. [CrossRef]

- Wilkes-Gillan, S., Munro, N., & Cordier, R. (2017). Pragmatic language outcomes of children with ADHD following play-based interventions. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(4), 7104220030p1–7104220030p10. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. S., Nankoo, M. M. A., Bucks, R. S., & Allen, J. (2023). Short form Conners' Adult ADHD Rating Scales: Factor structure and measurement invariance by sex in emerging adults. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 45(3), 278–295. [CrossRef]

- Yan, B. S. S., & Cheng, J. L. A. (2022). Psychoeducation and family intervention by parents of children with ADHD: A comprehensive study. Journal of Cognitive Sciences and Human Development, 8(2), 115-138.

- Young, S., & Goodman, R. (2016). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(1), 1-19.

- Zambrano-Sánchez, E., Cortéz, J. A. M., del Río Carlos, Y., Moreno, M. D., Cortés, N. A. S., Hernández, J. V., & Cervantes, T. E. R. (2023). Linguistic alterations in children with and without ADHD by clinical subtype evaluated with the BLOC-S-R test. Investigación sobre Discapacidad, 9, 109–114.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).