Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Dementia Classification and Neuroinflammation

2.1. Vascular Dementia and Neuroinflammation

2.2. Lewy Body Dementia and Neuroinflammation

2.3. Frontotemporal Dementia and Neuroinflammation

3. Distinctions Between Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease in Pathophysiology and Inflammation

3.1. Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s Disease Versus Other Dementia

3.2. Neuroinflammation as a Shared Mechanism Across Dementias and Implications

4. Current Research and Findings in Dementia and Neuroinflammation

4.1. Genetic Research and Inflammatory Pathways

4.2. Biomarkers of Neuroinflammation

4.3. Neuroimaging and Neuroinflammation

5. Current Treatment Methods

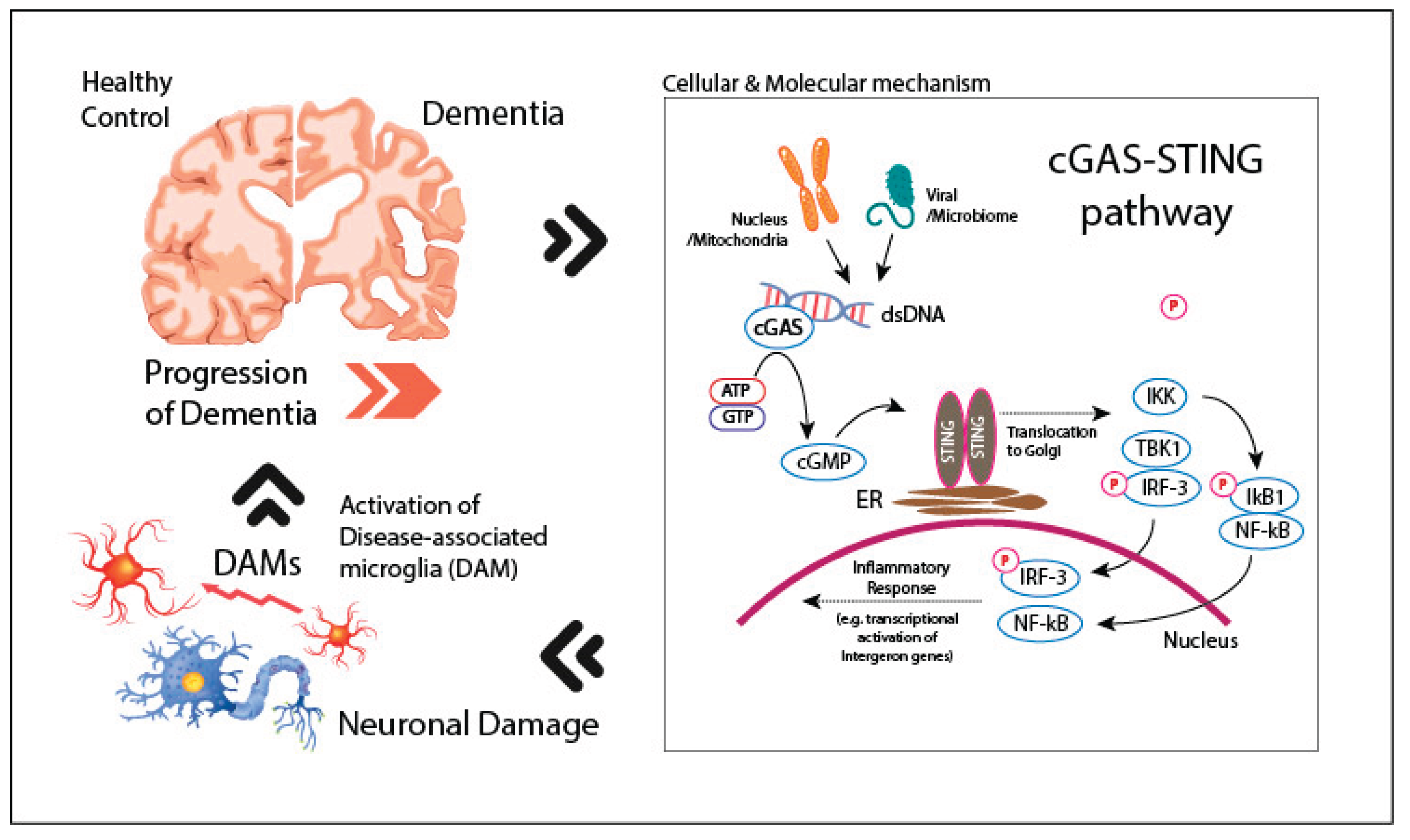

5.1. cGAS-STING Pathway and Neuroinflammation in Dementia: A Potential Therapeutic Target

5.2. Therapeutic Targeting of cGAS-STING in Neurodegeneration

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- 2020. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 16, 391-460. [CrossRef]

- ABLASSER, A. & CHEN, Z. J. 2019. cGAS in action: Expanding roles in immunity and inflammation. Science, 363, eaat8657. [CrossRef]

- ASKEW, K. E., BEVERLEY, J., SIGFRIDSSON, E., SZYMKOWIAK, S., EMELIANOVA, K., DANDO, O., HARDINGHAM, G. E., DUNCOMBE, J., HENNESSY, E., KOUDELKA, J., SAMARASEKERA, N., SALMAN, R. A., SMITH, C., TAVARES, A. A. S., GOMEZ-NICOLA, D., KALARIA, R. N., MCCOLL, B. W. & HORSBURGH, K. 2024. Inhibiting CSF1R alleviates cerebrovascular white matter disease and cognitive impairment. Glia, 72, 375-395. [CrossRef]

- ASSOCIATION, A. S. 2024. “What Is Dementia?” [Online]. Alzheimer’s Association. Available: https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia [Accessed September 10 2024].

- BACHILLER, S., JIMÉNEZ-FERRER, I., PAULUS, A., YANG, Y., SWANBERG, M., DEIERBORG, T. & BOZA-SERRANO, A. 2018. Microglia in Neurological Diseases: A Road Map to Brain-Disease Dependent-Inflammatory Response. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 12. [CrossRef]

- BAKER, M., MACKENZIE, I. R., PICKERING-BROWN, S. M., GASS, J., RADEMAKERS, R., LINDHOLM, C., SNOWDEN, J., ADAMSON, J., SADOVNICK, A. D. & ROLLINSON, S. 2006a. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature, 442, 916-919. [CrossRef]

- BAKER, M., MACKENZIE, I. R., PICKERING-BROWN, S. M., GASS, J., RADEMAKERS, R., LINDHOLM, C., SNOWDEN, J., ADAMSON, J., SADOVNICK, A. D., ROLLINSON, S., CANNON, A., DWOSH, E., NEARY, D., MELQUIST, S., RICHARDSON, A., DICKSON, D., BERGER, Z., ERIKSEN, J., ROBINSON, T., ZEHR, C., DICKEY, C. A., CROOK, R., MCGOWAN, E., MANN, D., BOEVE, B., FELDMAN, H. & HUTTON, M. 2006b. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature, 442, 916-9. [CrossRef]

- BEVAN-JONES, W. R., COPE, T. E., JONES, P. S., KAALUND, S. S., PASSAMONTI, L., ALLINSON, K., GREEN, O., HONG, Y. T., FRYER, T. D., ARNOLD, R., COLES, J. P., AIGBIRHIO, F. I., LARNER, A. J., PATTERSON, K., O’BRIEN, J. T. & ROWE, J. B. 2020. Neuroinflammation and protein aggregation co-localize across the frontotemporal dementia spectrum. Brain, 143, 1010-1026.

- BRIGHT, F., CHAN, G., VAN HUMMEL, A., ITTNER, L. M. & KE, Y. D. 2021. TDP-43 and Inflammation: Implications for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia. Int J Mol Sci, 22. [CrossRef]

- BRIGHT, F., WERRY, E. L., DOBSON-STONE, C., PIGUET, O., ITTNER, L. M., HALLIDAY, G. M., HODGES, J. R., KIERNAN, M. C., LOY, C. T., KASSIOU, M. & KRIL, J. J. 2019. Neuroinflammation in frontotemporal dementia. Nat Rev Neurol, 15, 540-555. [CrossRef]

- BRYANT, J. D., LEI, Y., VANPORTFLIET, J. J., WINTERS, A. D. & WEST, A. P. 2022. Assessing Mitochondrial DNA Release into the Cytosol and Subsequent Activation of Innate Immune-related Pathways in Mammalian Cells. Curr Protoc, 2, e372. [CrossRef]

- CALSOLARO, V. & EDISON, P. 2016. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: Current evidence and future directions. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 12, 719-732. [CrossRef]

- CHAPUIS, J., HANSMANNEL, F., GISTELINCK, M., MOUNIER, A., VAN CAUWENBERGHE, C., KOLEN, K. V., GELLER, F., SOTTEJEAU, Y., HAROLD, D., DOURLEN, P., GRENIER-BOLEY, B., KAMATANI, Y., DELEPINE, B., DEMIAUTTE, F., ZELENIKA, D., ZOMMER, N., HAMDANE, M., BELLENGUEZ, C., DARTIGUES, J. F., HAUW, J. J., LETRONNE, F., AYRAL, A. M., SLEEGERS, K., SCHELLENS, A., BROECK, L. V., ENGELBORGHS, S., DE DEYN, P. P., VANDENBERGHE, R., O’DONOVAN, M., OWEN, M., EPELBAUM, J., MERCKEN, M., KARRAN, E., BANTSCHEFF, M., DREWES, G., JOBERTY, G., CAMPION, D., OCTAVE, J. N., BERR, C., LATHROP, M., CALLAERTS, P., MANN, D., WILLIAMS, J., BUÉE, L., DEWACHTER, I., VAN BROECKHOVEN, C., AMOUYEL, P., MOECHARS, D., DERMAUT, B. & LAMBERT, J. C. 2013. Increased expression of BIN1 mediates Alzheimer genetic risk by modulating tau pathology. Mol Psychiatry, 18, 1225-34. [CrossRef]

- CHIA, R., SABIR, M. S., BANDRES-CIGA, S., SAEZ-ATIENZAR, S., REYNOLDS, R. H., GUSTAVSSON, E., WALTON, R. L., AHMED, S., VIOLLET, C., DING, J., MAKARIOUS, M. B., DIEZ-FAIREN, M., PORTLEY, M. K., SHAH, Z., ABRAMZON, Y., HERNANDEZ, D. G., BLAUWENDRAAT, C., STONE, D. J., EICHER, J., PARKKINEN, L., ANSORGE, O., CLARK, L., HONIG, L. S., MARDER, K., LEMSTRA, A., ST GEORGE-HYSLOP, P., LONDOS, E., MORGAN, K., LASHLEY, T., WARNER, T. T., JAUNMUKTANE, Z., GALASKO, D., SANTANA, I., TIENARI, P. J., MYLLYKANGAS, L., OINAS, M., CAIRNS, N. J., MORRIS, J. C., HALLIDAY, G. M., VAN DEERLIN, V. M., TROJANOWSKI, J. Q., GRASSANO, M., CALVO, A., MORA, G., CANOSA, A., FLORIS, G., BOHANNAN, R. C., BRETT, F., GAN-OR, Z., GEIGER, J. T., MOORE, A., MAY, P., KRÜGER, R., GOLDSTEIN, D. S., LOPEZ, G., TAYEBI, N., SIDRANSKY, E., SOTIS, A. R., SUKUMAR, G., ALBA, C., LOTT, N., MARTINEZ, E. M., TUCK, M., SINGH, J., BACIKOVA, D., ZHANG, X., HUPALO, D. N., ADELEYE, A., WILKERSON, M. D., POLLARD, H. B., NORCLIFFE-KAUFMANN, L., PALMA, J.-A., KAUFMANN, H., SHAKKOTTAI, V. G., PERKINS, M., NEWELL, K. L., GASSER, T., SCHULTE, C., LANDI, F., SALVI, E., CUSI, D., MASLIAH, E., KIM, R. C., CARAWAY, C. A., MONUKI, E. S., BRUNETTI, M., DAWSON, T. M., ROSENTHAL, L. S., ALBERT, M. S., PLETNIKOVA, O., TRONCOSO, J. C., FLANAGAN, M. E., MAO, Q., BIGIO, E. H., RODRÍGUEZ-RODRÍGUEZ, E., INFANTE, J., LAGE, C., GONZÁLEZ-ARAMBURU, I., SANCHEZ-JUAN, P., GHETTI, B., et al. 2021. Genome sequencing analysis identifies new loci associated with Lewy body dementia and provides insights into its genetic architecture. Nature Genetics, 53, 294-303. [CrossRef]

- COLLABORATORS, G. D. 2019. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol, 18, 88-106. [CrossRef]

- CUNNINGHAM, C. 2013. Microglia and neurodegeneration: the role of systemic inflammation. Glia, 61, 71-90. [CrossRef]

- CUSTODERO, C., CIAVARELLA, A., PANZA, F., GNOCCHI, D., LENATO, G. M., LEE, J., MAZZOCCA, A., SABBÀ, C. & SOLFRIZZI, V. 2022. Role of inflammatory markers in the diagnosis of vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Geroscience, 44, 1373-1392. [CrossRef]

- DANIILIDOU, M., HOLLEMAN, J., HAGMAN, G., KÅREHOLT, I., ASPÖ, M., BRINKMALM, A., ZETTERBERG, H., BLENNOW, K., SOLOMON, A., KIVIPELTO, M., SINDI, S. & MATTON, A. 2024. Neuroinflammation, cerebrovascular dysfunction and diurnal cortisol biomarkers in a memory clinic cohort: Findings from the Co-STAR study. Translational Psychiatry, 14, 364. [CrossRef]

- DE STROOPER, B. & KARRAN, E. 2016. The Cellular Phase of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell, 164, 603-15. [CrossRef]

- DECOUT, A., KATZ, J. D., VENKATRAMAN, S. & ABLASSER, A. 2021. The cGAS–STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nature Reviews Immunology, 21, 548-569. [CrossRef]

- DIB, S., PAHNKE, J. & GOSSELET, F. 2021. Role of ABCA7 in Human Health and in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci, 22. [CrossRef]

- EWERS, M., BIECHELE, G., SUÁREZ-CALVET, M., SACHER, C., BLUME, T., MORENAS-RODRIGUEZ, E., DEMING, Y., PICCIO, L., CRUCHAGA, C., KLEINBERGER, G., SHAW, L., TROJANOWSKI, J. Q., HERMS, J., DICHGANS, M., BRENDEL, M., HAASS, C. & FRANZMEIER, N. 2020. Higher CSF sTREM2 and microglia activation are associated with slower rates of beta-amyloid accumulation. EMBO Mol Med, 12, e12308. [CrossRef]

- FENG, T., MAI, S., ROSCOE, J. M., SHENG, R. R., ULLAH, M., ZHANG, J., KATZ, II, YU, H., XIONG, W. & HU, F. 2020. Loss of TMEM106B and PGRN leads to severe lysosomal abnormalities and neurodegeneration in mice. EMBO Rep, 21, e50219. [CrossRef]

- FERECSKÓ, A. S., SMALLWOOD, M. J., MOORE, A., LIDDLE, C., NEWCOMBE, J., HOLLEY, J., WHATMORE, J., GUTOWSKI, N. J. & EGGLETON, P. 2023. STING-Triggered CNS Inflammation in Human Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomedicines, 11. [CrossRef]

- FROZZA, R. L., LOURENCO, M. V. & DE FELICE, F. G. 2018. Challenges for Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy: Insights from Novel Mechanisms Beyond Memory Defects. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12. [CrossRef]

- GORELICK, P. B., SCUTERI, A., BLACK, S. E., DECARLI, C., GREENBERG, S. M., IADECOLA, C., LAUNER, L. J., LAURENT, S., LOPEZ, O. L., NYENHUIS, D., PETERSEN, R. C., SCHNEIDER, J. A., TZOURIO, C., ARNETT, D. K., BENNETT, D. A., CHUI, H. C., HIGASHIDA, R. T., LINDQUIST, R., NILSSON, P. M., ROMAN, G. C., SELLKE, F. W. & SESHADRI, S. 2011. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke, 42, 2672-713. [CrossRef]

- GOUILLY, D., SAINT-AUBERT, L., RIBEIRO, M. J., SALABERT, A. S., TAUBER, C., PÉRAN, P., ARLICOT, N., PARIENTE, J. & PAYOUX, P. 2022. Neuroinflammation PET imaging of the translocator protein (TSPO) in Alzheimer’s disease: an update. European Journal of Neuroscience, 55, 1322-1343. [CrossRef]

- GOVINDARAJULU, M., RAMESH, S., BEASLEY, M., LYNN, G., WALLACE, C., LABEAU, S., PATHAK, S., NADAR, R., MOORE, T. & DHANASEKARAN, M. 2023. Role of cGAS-Sting Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci, 24. [CrossRef]

- GRICIUC, A., SERRANO-POZO, A., PARRADO, A. R., LESINSKI, A. N., ASSELIN, C. N., MULLIN, K., HOOLI, B., CHOI, S. H., HYMAN, B. T. & TANZI, R. E. 2013. Alzheimer’s disease risk gene CD33 inhibits microglial uptake of amyloid beta. Neuron, 78, 631-43. [CrossRef]

- GUERREIRO, R., WOJTAS, A., BRAS, J., CARRASQUILLO, M., ROGAEVA, E., MAJOUNIE, E., CRUCHAGA, C., SASSI, C., KAUWE, J. S., YOUNKIN, S., HAZRATI, L., COLLINGE, J., POCOCK, J., LASHLEY, T., WILLIAMS, J., LAMBERT, J. C., AMOUYEL, P., GOATE, A., RADEMAKERS, R., MORGAN, K., POWELL, J., ST GEORGE-HYSLOP, P., SINGLETON, A. & HARDY, J. 2013. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med, 368, 117-27. [CrossRef]

- GUO, X., YANG, L., WANG, J., WU, Y., LI, Y., DU, L., LI, L., FANG, Z. & ZHANG, X. 2024. The cytosolic DNA-sensing cGAS-STING pathway in neurodegenerative diseases. CNS Neurosci Ther, 30, e14671. [CrossRef]

- HARDY, J. & SELKOE, D. J. 2002. The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and Problems on the Road to Therapeutics. Science, 297, 353-356. [CrossRef]

- HENEKA, M. T., CARSON, M. J., EL KHOURY, J., LANDRETH, G. E., BROSSERON, F., FEINSTEIN, D. L., JACOBS, A. H., WYSS-CORAY, T., VITORICA, J., RANSOHOFF, R. M., HERRUP, K., FRAUTSCHY, S. A., FINSEN, B., BROWN, G. C., VERKHRATSKY, A., YAMANAKA, K., KOISTINAHO, J., LATZ, E., HALLE, A., PETZOLD, G. C., TOWN, T., MORGAN, D., SHINOHARA, M. L., PERRY, V. H., HOLMES, C., BAZAN, N. G., BROOKS, D. J., HUNOT, S., JOSEPH, B., DEIGENDESCH, N., GARASCHUK, O., BODDEKE, E., DINARELLO, C. A., BREITNER, J. C., COLE, G. M., GOLENBOCK, D. T. & KUMMER, M. P. 2015. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol, 14, 388-405. [CrossRef]

- HEPPNER, F. L., RANSOHOFF, R. M. & BECHER, B. 2015. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16, 358-372. [CrossRef]

- HINKLE, J. T., PATEL, J., PANICKER, N., KARUPPAGOUNDER, S. S., BISWAS, D., BELINGON, B., CHEN, R., BRAHMACHARI, S., PLETNIKOVA, O., TRONCOSO, J. C., DAWSON, V. L. & DAWSON, T. M. 2022. STING mediates neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in nigrostriatal α-synucleinopathy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119. [CrossRef]

- HUANG, Y., LIU, B., SINHA, S. C., AMIN, S. & GAN, L. 2023. Mechanism and therapeutic potential of targeting cGAS-STING signaling in neurological disorders. Molecular Neurodegeneration, 18, 79. [CrossRef]

- INTERNATIONAL, A. S. D. 2024. Dementia statistics. Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- JACK, C. R., JR., BENNETT, D. A., BLENNOW, K., CARRILLO, M. C., DUNN, B., HAEBERLEIN, S. B., HOLTZMAN, D. M., JAGUST, W., JESSEN, F., KARLAWISH, J., LIU, E., MOLINUEVO, J. L., MONTINE, T., PHELPS, C., RANKIN, K. P., ROWE, C. C., SCHELTENS, P., SIEMERS, E., SNYDER, H. M. & SPERLING, R. 2018. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement, 14, 535-562. [CrossRef]

- JAUHARI, A., BARANOV, S. V., SUOFU, Y., KIM, J., SINGH, T., YABLONSKA, S., LI, F., WANG, X., OBERLY, P., MINNIGH, M. B., POLOYAC, S. M., CARLISLE, D. L. & FRIEDLANDER, R. M. 2020. Melatonin inhibits cytosolic mitochondrial DNA-induced neuroinflammatory signaling in accelerated aging and neurodegeneration. J Clin Invest, 130, 3124-3136. [CrossRef]

- JONSSON, T., STEFANSSON, H., STEINBERG, S., JONSDOTTIR, I., JONSSON, P. V., SNAEDAL, J., BJORNSSON, S., HUTTENLOCHER, J., LEVEY, A. I., LAH, J. J., RUJESCU, D., HAMPEL, H., GIEGLING, I., ANDREASSEN, O. A., ENGEDAL, K., ULSTEIN, I., DJUROVIC, S., IBRAHIM-VERBAAS, C., HOFMAN, A., IKRAM, M. A., VAN DUIJN, C. M., THORSTEINSDOTTIR, U., KONG, A. & STEFANSSON, K. 2013. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med, 368, 107-16. [CrossRef]

- KALARIA, R. N. 2016. Neuropathological diagnosis of vascular cognitive impairment and vascular dementia with implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol, 131, 659-85. [CrossRef]

- KARCH, C. M. & GOATE, A. M. 2015. Alzheimer’s disease risk genes and mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Biol Psychiatry, 77, 43-51. [CrossRef]

- KUNKLE, B. W., GRENIER-BOLEY, B., SIMS, R., BIS, J. C., DAMOTTE, V., NAJ, A. C., BOLAND, A., VRONSKAYA, M. V., VAN DER LEE, S. J., AMLIE-WOLF, A., BELLENGUEZ, C., FRIZATTI, A., CHOURAKI, V., MARTIN, E. R., SLEEGERS, K., BADARINARAYAN, N., JAKOBSDÓTTIR, J., HAMILTON-NELSON, K. L., MORENO-GRAU, S., OLASO, R., RAYBOULD, R., CHEN, Y., KUZMA, A. B., HILTUNEN, M., MORGAN, T., AHMAD, S., VARDARAJAN, B. N., EPELBAUM, J., HOFFMANN, P., BOADA, M., BEECHAM, G. W., GARNIER, J.-G., HAROLD, D. H., FITZPATRICK, A. L., VALLADARES, O., MOUTET, M.-L., GERRISH, A., SMITH, A. V., QU, L., BACQ, D., DENNING, N., JIAN, X., ZHAO, Y., DEL ZOMPO, M., FOX, N. C., CHOI, S. H., MATEO, I., HUGHES, J. T., ADAMS, H. H. H., MALAMON, J. S., SÁNCHEZ-GARCÍA, F., PATEL, Y., BRODY, J. A., DOMBROSKI, B. A., NARANJO, M. C. D., DANIILIDOU, M., EIRIKSDOTTIR, G., MUKHERJEE, S., WALLON, D., UPHILL, J. B., ASPELUND, T., CANTWELL, L., GARZIA, F., GALIMBERTI, D., HOFER, E., BUTKIEWICZ, M., FIN, B., SCARPINI, E., SARNOWSKI, C., BUSH, W. S., MESLAGE, S., KORNHUBER, J., WHITE, C. C., SONG, Y., BARBER, R. C., ENGELBORGHS, S., SORDON, S., VOIJNOVIC, D., ADAMS, P. M., VANDENBERGHE, R., MAYHAUS, M., CUPPLES, L. A., ALBERT, M. S., DE DEYN, P. P., GU, W., HIMALI, J. J., BEEKLY, D. L., SQUASSINA, A., HARTMANN, A. M., ORELLANA, A., BLACKER, D., RODRÍGUEZ-RODRÍGUEZ, E., LOVESTONE, S., GARCIA, M. E., DOODY, R., MUNOZ-FERNADEZ, C., SUSSAMS, R., LIN, H., FAIRCHILD, T. J., BENITO, Y. A., et al. 2019. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nature Genetics, 51, 414–430. [CrossRef]

- LEDO, J. H., LIEBMANN, T., ZHANG, R., CHANG, J. C., AZEVEDO, E. P., WONG, E., SILVA, H. M., TROYANSKAYA, O. G., BUSTOS, V. & GREENGARD, P. 2021. Presenilin 1 phosphorylation regulates amyloid-β degradation by microglia. Molecular Psychiatry, 26, 5620-5635. [CrossRef]

- LEE, S., DEVANNEY, N. A., GOLDEN, L. R., SMITH, C. T., SCHWARTZ, J. L., WALSH, A. E., CLARKE, H. A., GOULDING, D. S., ALLENGER, E. J., MORILLO-SEGOVIA, G., FRIDAY, C. M., GORMAN, A. A., HAWKINSON, T. R., MACLEAN, S. M., WILLIAMS, H. C., SUN, R. C., MORGANTI, J. M. & JOHNSON, L. A. 2023. APOE modulates microglial immunometabolism in response to age, amyloid pathology, and inflammatory challenge. Cell Rep, 42, 112196. [CrossRef]

- LEYNS, C. E. G., ULRICH, J. D., FINN, M. B., STEWART, F. R., KOSCAL, L. J., REMOLINA SERRANO, J., ROBINSON, G. O., ANDERSON, E., COLONNA, M. & HOLTZMAN, D. M. 2017. TREM2 deficiency attenuates neuroinflammation and protects against neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, 11524-11529. [CrossRef]

- LIU, Y., ZHANG, B., DUAN, R. & LIU, Y. 2024. Mitochondrial DNA Leakage and cGas/STING Pathway in Microglia: Crosstalk Between Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration. Neuroscience, 548, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- LOVE, S. & MINERS, J. S. 2016. Cerebrovascular disease in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica, 131, 645-658. [CrossRef]

- LOVELAND, P. M., YU, J. J., CHURILOV, L., YASSI, N. & WATSON, R. 2023. Investigation of Inflammation in Lewy Body Dementia: A Systematic Scoping Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24, 12116. [CrossRef]

- MARQUES, C., HELD, A., DORFMAN, K., SUNG, J., SONG, C., KAVUTURU, A. S., AGUILAR, C., RUSSO, T., OAKLEY, D. H., ALBERS, M. W., HYMAN, B. T., PETRUCELLI, L., LAGIER-TOURENNE, C. & WAINGER, B. J. 2024. Neuronal STING activation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol, 147, 56. [CrossRef]

- MATHUR, V., BURAI, R., VEST, R. T., BONANNO, L. N., LEHALLIER, B., ZARDENETA, M. E., MISTRY, K. N., DO, D., MARSH, S. E., ABUD, E. M., BLURTON-JONES, M., LI, L., LASHUEL, H. A. & WYSS-CORAY, T. 2017. Activation of the STING-Dependent Type I Interferon Response Reduces Microglial Reactivity and Neuroinflammation. Neuron, 96, 1290-1302.e6. [CrossRef]

- MISHRA, S., KNUPP, A., YOUNG, J. E. & JAYADEV, S. 2022. Depletion of the AD risk gene SORL1 causes endo-lysosomal dysfunction in human microglia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 18, e068943. [CrossRef]

- MOYSE, E., KRANTIC, S., DJELLOULI, N., ROGER, S., ANGOULVANT, D., DEBACQ, C., LEROY, V., FOUGERE, B. & AIDOUD, A. 2022. Neuroinflammation: A Possible Link Between Chronic Vascular Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14. [CrossRef]

- NABIZADEH, F., SEYEDMIRZAEI, H. & KARAMI, S. 2024. Neuroimaging biomarkers and CSF sTREM2 levels in Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal study. Scientific Reports, 14, 15318. [CrossRef]

- NAJ, A. C., JUN, G., BEECHAM, G. W., WANG, L. S., VARDARAJAN, B. N., BUROS, J., GALLINS, P. J., BUXBAUM, J. D., JARVIK, G. P., CRANE, P. K., LARSON, E. B., BIRD, T. D., BOEVE, B. F., GRAFF-RADFORD, N. R., DE JAGER, P. L., EVANS, D., SCHNEIDER, J. A., CARRASQUILLO, M. M., ERTEKIN-TANER, N., YOUNKIN, S. G., CRUCHAGA, C., KAUWE, J. S., NOWOTNY, P., KRAMER, P., HARDY, J., HUENTELMAN, M. J., MYERS, A. J., BARMADA, M. M., DEMIRCI, F. Y., BALDWIN, C. T., GREEN, R. C., ROGAEVA, E., ST GEORGE-HYSLOP, P., ARNOLD, S. E., BARBER, R., BEACH, T., BIGIO, E. H., BOWEN, J. D., BOXER, A., BURKE, J. R., CAIRNS, N. J., CARLSON, C. S., CARNEY, R. M., CARROLL, S. L., CHUI, H. C., CLARK, D. G., CORNEVEAUX, J., COTMAN, C. W., CUMMINGS, J. L., DECARLI, C., DEKOSKY, S. T., DIAZ-ARRASTIA, R., DICK, M., DICKSON, D. W., ELLIS, W. G., FABER, K. M., FALLON, K. B., FARLOW, M. R., FERRIS, S., FROSCH, M. P., GALASKO, D. R., GANGULI, M., GEARING, M., GESCHWIND, D. H., GHETTI, B., GILBERT, J. R., GILMAN, S., GIORDANI, B., GLASS, J. D., GROWDON, J. H., HAMILTON, R. L., HARRELL, L. E., HEAD, E., HONIG, L. S., HULETTE, C. M., HYMAN, B. T., JICHA, G. A., JIN, L. W., JOHNSON, N., KARLAWISH, J., KARYDAS, A., KAYE, J. A., KIM, R., KOO, E. H., KOWALL, N. W., LAH, J. J., LEVEY, A. I., LIEBERMAN, A. P., LOPEZ, O. L., MACK, W. J., MARSON, D. C., MARTINIUK, F., MASH, D. C., MASLIAH, E., MCCORMICK, W. C., MCCURRY, S. M., MCDAVID, A. N., MCKEE, A. C., MESULAM, M., MILLER, B. L., et al. 2011. Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet, 43, 436-41. [CrossRef]

- O’ROURKE, J. G., BOGDANIK, L., YÁÑEZ, A., LALL, D., WOLF, A. J., MUHAMMAD, A. K., HO, R., CARMONA, S., VIT, J. P., ZARROW, J., KIM, K. J., BELL, S., HARMS, M. B., MILLER, T. M., DANGLER, C. A., UNDERHILL, D. M., GOODRIDGE, H. S., LUTZ, C. M. & BALOH, R. H. 2016. C9orf72 is required for proper macrophage and microglial function in mice. Science, 351, 1324-9. [CrossRef]

- PAN, J., HU, J., MENG, D., CHEN, L. & WEI, X. 2024. Neuroinflammation in dementia: A meta-analysis of PET imaging studies. Medicine (Baltimore), 103, e38086. [CrossRef]

- PASINELLI, P. & BROWN, R. H. 2006. Molecular biology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from genetics. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7, 710-723. [CrossRef]

- PAUL, B. D., SNYDER, S. H. & BOHR, V. A. 2021. Signaling by cGAS-STING in Neurodegeneration, Neuroinflammation, and Aging. Trends Neurosci, 44, 83-96. [CrossRef]

- PICCA, A., CALVANI, R., COELHO-JUNIOR, H. J., LANDI, F., BERNABEI, R. & MARZETTI, E. 2020. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Neuroinflammation: Intertwined Roads to Neurodegeneration. Antioxidants (Basel), 9. [CrossRef]

- RANSOHOFF, R. M. 2016a. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science, 353, 777-783. [CrossRef]

- RANSOHOFF, R. M. 2016b. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science, 353, 777-83. [CrossRef]

- SALTER, M. W. & STEVENS, B. 2017. Microglia emerge as central players in brain disease. Nature Medicine, 23, 1018-1027. [CrossRef]

- SHARMA, O., KAUR GREWAL, A., KHAN, H. & GURJEET SINGH, T. 2024. Exploring the nexus of cGAS STING pathway in neurodegenerative terrain: A therapeutic odyssey. Int Immunopharmacol, 142, 113205. [CrossRef]

- SHI, Y., YAMADA, K., LIDDELOW, S. A., SMITH, S. T., ZHAO, L., LUO, W., TSAI, R. M., SPINA, S., GRINBERG, L. T., ROJAS, J. C., GALLARDO, G., WANG, K., ROH, J., ROBINSON, G., FINN, M. B., JIANG, H., SULLIVAN, P. M., BAUFELD, C., WOOD, M. W., SUTPHEN, C., MCCUE, L., XIONG, C., DEL-AGUILA, J. L., MORRIS, J. C., CRUCHAGA, C., FAGAN, A. M., MILLER, B. L., BOXER, A. L., SEELEY, W. W., BUTOVSKY, O., BARRES, B. A., PAUL, S. M. & HOLTZMAN, D. M. 2017. ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature, 549, 523-527. [CrossRef]

- SIDDIQUI, S. S., MATAR, R., MERHEB, M., HODEIFY, R., VAZHAPPILLY, C. G., MARTON, J., SHAMSUDDIN, S. A. & AL ZOUABI, H. 2019. Siglecs in Brain Function and Neurological Disorders. Cells, 8, 1125. [CrossRef]

- SIERKSMA, A., LU, A., MANCUSO, R., FATTORELLI, N., THRUPP, N., SALTA, E., ZOCO, J., BLUM, D., BUÉE, L., DE STROOPER, B. & FIERS, M. 2020. Novel Alzheimer risk genes determine the microglia response to amyloid-β but not to TAU pathology. EMBO Mol Med, 12, e10606. [CrossRef]

- SLITER, D. A., MARTINEZ, J., HAO, L., CHEN, X., SUN, N., FISCHER, T. D., BURMAN, J. L., LI, Y., ZHANG, Z., NARENDRA, D. P., CAI, H., BORSCHE, M., KLEIN, C. & YOULE, R. J. 2018. Parkin and PINK1 mitigate STING-induced inflammation. Nature, 561, 258-262. [CrossRef]

- SPIRES-JONES, TARA L. & HYMAN, BRADLEY T. 2014. The Intersection of Amyloid Beta and Tau at Synapses in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron, 82, 756-771. [CrossRef]

- STOLL, A. C. & SORTWELL, C. E. 2022. Leveraging the preformed fibril model to distinguish between alpha-synuclein inclusion- and nigrostriatal degeneration-associated immunogenicity. Neurobiology of Disease, 171, 105804. [CrossRef]

- SURENDRANATHAN, A., SU, L., MAK, E., PASSAMONTI, L., HONG, Y. T., ARNOLD, R., VÁZQUEZ RODRÍGUEZ, P., BEVAN-JONES, W. R., BRAIN, S. A. E., FRYER, T. D., AIGBIRHIO, F. I., ROWE, J. B. & O’BRIEN, J. T. 2018. Early microglial activation and peripheral inflammation in dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain, 141, 3415-3427. [CrossRef]

- TEJERA, D. & HENEKA, M. T. 2019. Microglia in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Methods Mol Biol, 2034, 57-67. [CrossRef]

- TIAN, Z., JI, X. & LIU, J. 2022. Neuroinflammation in Vascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Current Evidence, Advances, and Prospects. Int J Mol Sci, 23. [CrossRef]

- ULLAND, T. K. & COLONNA, M. 2018. TREM2—a key player in microglial biology and Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol, 14, 667-675. [CrossRef]

- VENKAT, P., CHOPP, M. & CHEN, J. 2015. Models and mechanisms of vascular dementia. Experimental neurology, 272, 97-108. [CrossRef]

- VRILLON, A., BOUSIGES, O., GÖTZE, K., DEMUYNCK, C., MULLER, C., RAVIER, A., SCHORR, B., PHILIPPI, N., HOURREGUE, C., COGNAT, E., DUMURGIER, J., LILAMAND, M., CRETIN, B., BLANC, F. & PAQUET, C. 2024. Plasma biomarkers of amyloid, tau, axonal, and neuroinflammation pathologies in dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 16, 146. [CrossRef]

- YIN, Z., ROSENZWEIG, N., KLEEMANN, K. L., ZHANG, X., BRANDÃO, W., MARGETA, M. A., SCHROEDER, C., SIVANATHAN, K. N., SILVEIRA, S., GAUTHIER, C., MALLAH, D., PITTS, K. M., DURAO, A., HERRON, S., SHOREY, H., CHENG, Y., BARRY, J. L., KRISHNAN, R. K., WAKELIN, S., RHEE, J., YUNG, A., ARONCHIK, M., WANG, C., JAIN, N., BAO, X., GERRITS, E., BROUWER, N., DEIK, A., TENEN, D. G., IKEZU, T., SANTANDER, N. G., MCKINSEY, G. L., BAUFELD, C., SHEPPARD, D., KRASEMANN, S., NOWARSKI, R., EGGEN, B. J. L., CLISH, C., TANZI, R. E., MADORE, C., ARNOLD, T. D., HOLTZMAN, D. M. & BUTOVSKY, O. 2023. APOE4 impairs the microglial response in Alzheimer’s disease by inducing TGFβ-mediated checkpoints. Nat Immunol, 24, 1839-1853. [CrossRef]

- YU, X., CAI, L., YAO, J., LI, C. & WANG, X. 2024. Agonists and Inhibitors of the cGAS-STING Pathway. Molecules, 29. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, J. 2015. Mapping neuroinflammation in frontotemporal dementia with molecular PET imaging. J Neuroinflammation, 12, 108. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, W., XIAO, D., MAO, Q. & XIA, H. 2023. Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 8, 267. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, Y., ZOU, M., WU, H., ZHU, J. & JIN, T. 2024. The cGAS-STING pathway drives neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration via cellular and molecular mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiology of Disease, 202, 106710. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG, Z. & ZHAO, Y. 2022. Progress on the roles of MEF2C in neuropsychiatric diseases. Molecular Brain, 15, 8. [CrossRef]

- ZHAO, P., XU, Y., JIANG, L. L., FAN, X., KU, Z., LI, L., LIU, X., DENG, M., ARASE, H., ZHU, J. J., HUANG, T. Y., ZHAO, Y., ZHANG, C., XU, H., TONG, Q., ZHANG, N. & AN, Z. 2022. LILRB2-mediated TREM2 signaling inhibition suppresses microglia functions. Mol Neurodegener, 17, 44. [CrossRef]

| Gene | Chromosom Location |

Role in Microglia Activation | Associated Dementia |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR1 | 1q32.2 | Variants in CR1 impair complement regulation and enhance microglial activation via the complement cascade. | AD | (Karch and Goate, 2015) |

| BIN1 | 2q14.3 | BIN1 variants may regulate microglial activity through interaction with the immune system, including modulation of pro-inflammatory responses. | AD | (Chapuis et al., 2013) |

| MEF2C | 5q14.3 | MEF2C regulates microglial homeostasis and suppresses pro-inflammatory gene expression, thereby protecting neurons from excessive neuroinflammation. | AD | (Zhang and Zhao, 2022) |

| TREM2 | 6p21.1 | TREM2 mutations impair microglial phagocytic function and lead to chronic neuroinflammation, enhancing microglial activation. | AD, FTD | (Jonsson et al., 2013, Guerreiro et al., 2013) |

| MS4A | 11q12.2 | Modulates microglial inflammatory signaling by altering membrane protein interactions and intracellular communication pathways. | Alzheimer’s Disease | (Naj et al., 2011, Kunkle et al., 2019) |

| SORL1 | 11q24.2 | SORL1 mutations altered lysosome function of microglia, leading to amyloid ϐ accumulation. | AD | (Mishra et al., 2022) |

| PS1 | 14q24.2 | PS1 modulates microglial response to amyloid ϐ and to maintain brain homeostasis by regulating lysosomal calcium signaling and autophagy. | AD | (Ledo et al., 2021) |

| PLCG2 | 16q23.3 | Activating mutations in PLCG2 promote microglial activation and phagocytosis, improving immune response in Alzheimer’s disease. | AD | (Sierksma et al., 2020) |

| APOE ε4 | 19q13.32 | APOE ε4 induces pro-inflammatory microglial activation through various pathways, including C1q complement activation. | AD | (Shi et al., 2017) |

| CD33 | 19q13.41 | Loss of function of CD33 reduces microglial activation and enhances amyloid clearance, suggesting CD33 inhibits microglial activation in dementia. | AD | (Griciuc et al., 2013, Siddiqui et al., 2019) |

| ABCA7 | 19p13.3 | ABCA7 regulates microglial activation by modulating cholesterol efflux and lipid metabolism, which influences the microglial inflammatory response and phagocytic activity. | AD | (Dib et al., 2021) |

| LILRB2 | 19q13.42 | LILRB2 is co-expressed with TREM2 in microglia and associated with microglial activation by regulating the inflammatory response and the phagocytic activity of microglia. | AD | (Zhao et al., 2022) |

| TMEM106B | 7p21.3 | Loss of TMEM106B along with PGRN triggers the lysosomal dysfunction in microglia and exacerbates microglial activation, leading to neurodegeneration. | FTD | (Feng et al., 2020) |

| C9orf72 | 9p21.2 | C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions lead to neuroinflammation and dysregulated microglial activation, contributing to neurodegeneration. | FTD, ALS | (O’Rourke et al., 2016) |

| GRN | 17q21.31 | GRN mutations reduce progranulin levels, leading to increased neuroinflammation and excessive microglial activation. | FTD | (Baker et al., 2006b) |

| SOD1 | 21q22.11 | Mutant SOD1 increases oxidative stress and promotes neuroinflammation through enhanced microglial activation in ALS. | ALS | (Pasinelli and Brown, 2006) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).