1. Introduction

The Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015 under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), marked a huge milestone in the global fight against climate change (Savaresi, 2016;) . It established ambitious goals to limit the rise in average global temperatures to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, with an aspiration to achieve a limit of 1.5 °C (UNFCCC, 2015; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2019; Jotzo et al., 2018). However, repeated U.S. disengagement, particularly during the Trump administration, has significantly complicated international climate negotiations (White House, 2025; Horton et al., 2025). Despite its economic and political power, the U.S. has often exhibited inconsistent leadership in global climate efforts. This pattern of withdrawal and re-engagement, coupled with domestic political volatility, has depleted diplomatic energy, constrained potential achievements, and overshadowed more consistent leadership from other nations (MacNeil, 2017; Horton et al., 2025). Trump’s outright rejection of climate politics and his desire to revert to previous conditions positions him as a unique actor in the debate over global norms, akin to a reactionary norm entrepreneur (Ettinger, A., & Collins, A. M., 2025; Yong-xiang et al., 2017).

As the world’s second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, U.S. involvement is crucial for making substantial progress in these talks. Many perceive its participation in agreements like the Paris Agreement as highly important. Without the US involved, it’s hard to make real progress (EPA, 2023;Yong-xiang et al., 2017). The U.S. has a complicated role when it comes to global climate efforts. As the second-biggest emitter and the biggest economy in the world, many see its involvement in deals like the Paris Agreement as pretty important. This review examines the U.S. decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, considering its effects on both developed and least developed countries. It also analyzes the scientific implications for global warming efforts and its potential influence on the upcoming UN COP30 climate conference in Brazil in 2025.

2. Methodology

This systematic review synthesizes empirical and policy analyses on the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, assessing its political, economic, and scientific impacts, with emphasis on disparities between developed and least-developed countries (LDCs).

2.1. Research Questions

What are the political, economic, and scientific consequences of the U.S. withdrawal?

How do these consequences differentially affect developed countries and LDCs?

2.2. Search Strategy

Databases: Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar.

Grey Literature: UNFCCC, IPCC, OECD reports, NGO publications.

Keywords: Combinations of (“Paris Agreement” + “U.S. withdrawal”), (“climate finance” + “LDCs”), *(“COP30” + “global governance”)*.

Timeframe: No date restrictions (coverage up to 2025).

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Included: Peer-reviewed studies, policy analyses, and reports addressing U.S. withdrawal impacts on global climate governance, finance, or emissions. English-language only.

Excluded: Opinion pieces, domestic U.S. policy studies, non-Paris Agreement-related documents.

2.5. Data Extraction

Variables: Publication details, study type, key findings (political/economic/scientific impacts), LDC vs. developed country disparities, policy recommendations.

2.6. Synthesis

Approach: Thematic narrative synthesis (no meta-analysis due to data heterogeneity).

Focus: Comparative analysis of consequences across regions, implications for COP30.

3. Thoughts on the U.S. Withdrawal from the Paris Agreement.

3.1. Viewpoint from Developed Countries

From the perspective of developed nations, the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement constituted a significant detriment to global climate efforts (Yong-xiang et al., 2017;Hai-bin et al., 2017;Falkner et al., 2010). Historically, countries like the U.S. have been the biggest sources of greenhouse gases and possess the financial resources and technology to spearhead climate solutions (IEA, 2022). The U.S. departure fragmented the diplomatic framework that had encouraged nations to establish and implement more ambitious carbon emission reduction plans (Bodansky, 2021).

Nevertheless, some argue that the U.S. stepping back could potentially foster a more robust and flexible global system for climate governance. A reduced focus on U.S. priorities might empower other climate leaders, such as the EU and China, along with smaller groups, to undertake more equitable and ambitious climate initiatives (Pavone, 2018). Following the withdrawal, concerns arose that other countries might follow suit, potentially weakening the Paris Agreement and impeding global climate action (von Allwörden, L., 2025). “This decision also created a leadership void, potentially enabling major emitters like China and India to reduce their own climate commitments (Hai-bin et al., 2017;Horton et al., 2025; Falkner, 2020;Stoddard et al., 2021).

Pavone, (2018) highlights the U.S.’s recurrent pattern of withdrawing from and rejoining international climate treaties. This oscillation has consumed substantial diplomatic effort and has rendered global climate efforts less stable and ambitious over time (Zhang et al., 2017). Some contend that the persistent political complexities and internal blocking within the U.S. have consistently hindered effective global climate efforts. They suggest that a permanent U.S. absence could potentially facilitate more streamlined and stable international cooperation. (MacNeil, 2025). It also lowers the overall goals of the Paris Agreement because other countries might see the U.S. as not fully committed. That could make them less motivated to keep up their efforts too (Sælen et al., 2020). Some people say that the messy politics and constant blocking inside the U.S. have always made it hard to work well on global climate efforts. They think that if the U.S. stayed out forever, international cooperation might become easier and more steady (MacNeil, 2025).

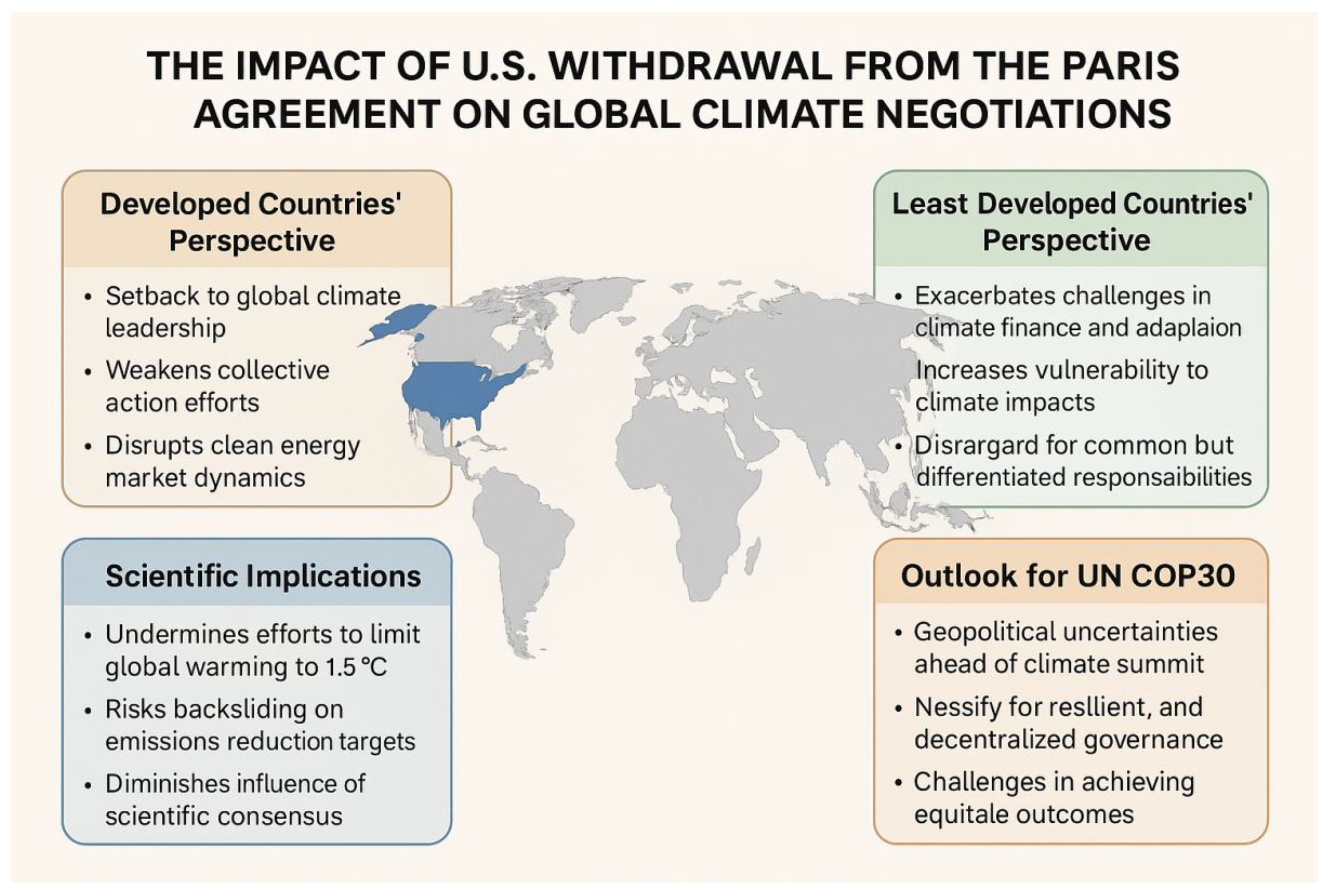

The implications of the U.S. withdrawal, as summarized in

Figure 1, are multifaceted. The withdrawal significantly impacted the economies of developed countries, disrupting the global clean energy market (Alessi et al., 2024). Consequently, other nations, particularly China, assumed leadership in technology and business; today, China is the largest producer of solar panels worldwide (IEA, 2022). Domestically, this shift likely impeded the growth of renewable energy in the U.S., complicated U.S.-European collaboration on climate efforts, and eroded investor confidence in green technologies. Evidence of this is apparent in the decline of jobs in the U.S. solar industry following the withdrawal (see

Figure 1). The U.S. often acts as a free rider on environmental issues and trade, prioritizing its national laws over international agreements. This approach tends to emphasize short-term economic gains but can undermine long-term global climate mitigation efforts. (DOE, 2021;Pavone, 2018).

3.2. Perspective of Least Developed Countries

For Least Developed Countries (LDCs), the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement presents a serious challenge (Ullah et al., 2025). While the Paris Agreement aims for inclusivity, many LDCs, particularly in Africa, continue to face significant long-standing obstacles in international climate negotiations. These issues, including insufficient representation, limited access to technical expertise, and inadequate funding, severely impede their engagement and ability to advocate for equitable climate solutions (Chinoko et al., 2025 ;Havukainen et al., 2022).

Many LDCs are disproportionately affected by climate change, experiencing rising sea levels, more intense storms and floods, and prolonged droughts. They heavily rely on international climate funds to implement their climate adaptation and mitigation plans. Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the Paris Agreement stipulates that developed countries should maintain leadership by setting comprehensive, transparent emission reduction targets across their entire economies (MacNeil, 2025; Alessi et al., 2024). However, the U.S. withdrawal diminished this leadership role and disrupted global climate finance mechanisms. From the LDC perspective, the observed positive correlation between international cooperation (SDG-17) and climate action (SDG-13) among G-20 countries underscores the vital importance of fostering stronger, more comprehensive global partnerships. These partnerships should prioritize amplifying the voices of the world’s most vulnerable communities, who are most severely impacted by climate change (Ullah et al., 2025) .

The U.S. was expected to play a substantial role in achieving the pledged $100 billion per year in climate funding under the Paris Agreement. Its departure created significant funding deficits, impeding crucial projects such as flood defenses, early warning systems, and climate-resilient infrastructure (OECD, 2021; Zhang et al., 2017;Chai et al., 2017) . This decision contravened the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC), which aims to ensure equitable burden-sharing in climate efforts. Instead, it disproportionately shifted the burden onto developing countries, deviating from the original intent (UNFCCC, 2015). While the Agreement encourages developing countries to pursue emission reductions and gradually set economy-wide targets, the withdrawal of a major emitter like the U.S. sends a discouraging signal (MacNeil, 2025).

The U.S. withdrawal raised concerns that other major polluters might also renege on their commitments. It damaged the moral standing and diplomatic trust in the Paris Agreement, complicating the establishment and enforcement of robust international climate policies, particularly for countries most affected by climate change (IPCC, 2023). Despite widespread global support for the Paris Agreement, the Trump administration adopted a “free-riding” approach, prioritizing immediate U.S. interests over collective global efforts (MacNeil, 2025).

3.3. Scientific Justification and Global Warming Implications

The overwhelming scientific consensus indicates that limiting global warming to approximately 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels is essential to avert the most severe and irreversible impacts of climate change. The IPCC (2023) highlights the necessity of reducing global greenhouse gas emissions by nearly half by 2030 and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 to meet this target. These targets are not merely aspirational; they are critical benchmarks derived from extensive climate studies and risk analyses. However, achieving such significant reductions fundamentally depends on concerted global cooperation, especially from major emitters like the U.S.

3.3.1. Emission Trajectory Scenarios

As the world’s second-largest overall emitter, U.S. participation is crucial for combating climate change. Its decision to withdraw from global climate agreements has profound scientific and environmental consequences. Integrated assessment models, such as GCAM-TU, are utilized to explore various global emission pathways based on implemented policies.

1. Emission Trajectory Scenarios

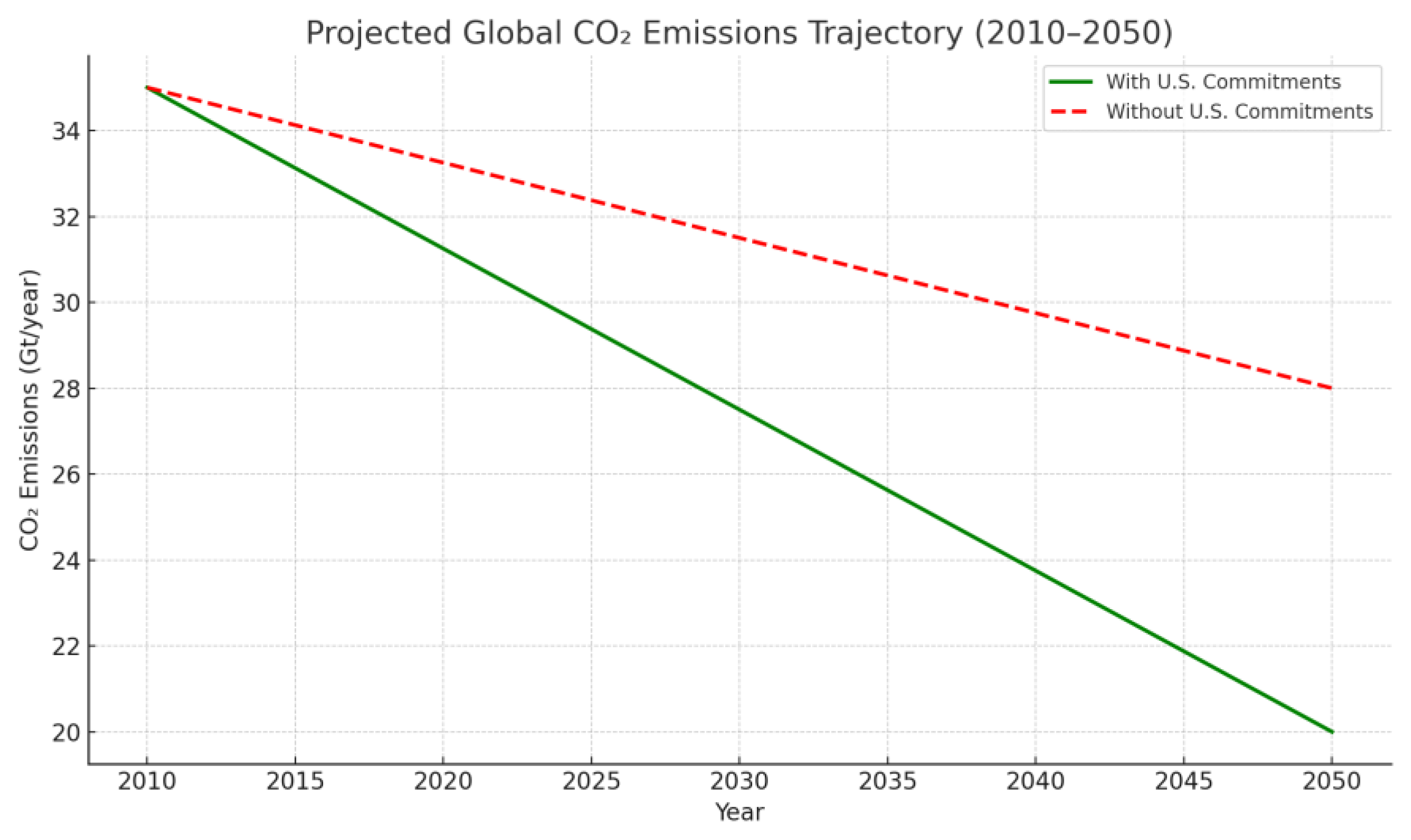

Figure 2 illustrates global CO₂ emissions projections with and without U.S. climate commitments. U.S. leadership significantly affects the global capacity to remain within the 1.5 °C or 2 °C warming thresholds.

These models demonstrate that without U.S. emission reduction efforts, global emission levels in 2100 could be substantially higher, leading to increased warming and more severe climate change impacts. International agreements like the Paris Agreement aim to keep global temperature increases below 2 °C, ideally below 1.5 °C, to prevent dangerous alterations and feedback loops within the climate system(Chen et al., 2018).

The U.S. withdrawal could lead to increased global emissions. Recent research indicates that the U.S. accounts for approximately 15% of global CO₂ emissions. If the U.S. fails to contribute its share to emission reductions, it significantly impedes overall global progress in curbing pollution. This exacerbates pressure on the remaining carbon budget—the finite amount of CO₂ that can still be released while aiming to limit global warming to 1.5 °C or 2 °C. This limit is very tight and challenging to manage, as depicted in

Figure 1(Grigoroudis et al., 2018).

The U.S. withdrawal could lead to increased global emissions. Recent research indicates that the U.S. accounts for approximately 15% of global CO₂ emissions (Global Carbon Atlas, 2023). If the U.S. doesn’t do its part to cut emissions, it makes it much harder for the whole world to make progress on reducing pollution. If the U.S. fails to contribute its share to emission reductions, it significantly impedes overall global progress in curbing pollution. This exacerbates pressure on the remaining carbon budget the finite amount of CO₂ that can still be released while aiming to limit global warming to 1.5 °C or 2 °C. This limit is very tight and challenging to manage, as depicted in

Figure 1.

3.3.2. Tipping Points and Carbon Budgets

The delay or insufficient action from the U.S. increases the likelihood of falling behind on emission reduction targets and heightens the risk of crossing dangerous climate tipping points. These are critical thresholds in the Earth’s climate system which, if exceeded, can lead to irreversible changes, often with cascading effects. Examples include the irreversible melting of Arctic sea ice, destabilization of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, and the critical shrinkage of the Amazon rainforest to a point where it could become a net carbon source rather than a sink (Lovejoy & Nobre, 2023). Once crossed, these tipping points could trigger a, they could set off a chain reaction in the climate system that makes global warming much worse and harder to control cascading effect within the climate system, intensifying global warming and making it much harder to control.

Understanding the concept of a “carbon budget” is crucial here. This budget represents the finite amount of CO₂ that can be emitted globally while keeping global warming below a specific temperature target, such as 1.5 °C or 2 °C, with a certain probability (Global Carbon Atlas, 2023). Given the tight nature of this budget, the substantial emissions from a major economy like the U.S. directly consume a significant portion of it. Any failure to contribute its fair share to emission reductions, especially following a withdrawal from international commitments, further constrains the remaining budget for the rest of the world. This situation exacerbates the challenge for all nations, particularly those with fewer resources, to achieve their climate goals within the limited carbon space. Consequently, the likelihood of overshooting temperature targets and triggering irreversible climate impacts increases.

Furthermore, another significant impact of the U.S. withdrawal is the reduction in financial flows towards climate projects. As one of the largest contributors to global climate funds, the U.S. disengagement impedes the ability of leaders worldwide, particularly in poorer and more vulnerable regions, to combat climate change and adapt to its effects. The decline in financial resources hinders the implementation of resilience projects, technological upgrades, and the development of necessary infrastructure in countries most affected by climate change.

The withdrawal also has considerable economic and technological impacts. Transitioning to a low-carbon economy necessitates investment in green finance, renewable energy, and clean technologies. The U.S. has historically been a leader in innovation and investment in these areas. Retreating from climate commitments could decelerate progress, deter private sector engagement, and hinder the global dissemination of new energy technologies (Li et al., 2024). The Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015, played a crucial role in encouraging countries to increase investments in clean energy and establish a pathway for sustainable growth (Luo et al., 2023). . Analysis of scientific papers post-Paris reveals a clear surge in research concerning climate resilience, urban adaptation, and low-carbon transitions, demonstrating how international agreements shape both scientific inquiry and policy discourse (Sietsma et al., 2024). Thus, the Thus, the U.S. disengagement not only affects scientific efforts and financial flows but also weakens the overall framework coordinating global climate action. Climate agreements function optimally with mutual trust, shared objectives, and collective participation. When a major player like the U.S. withdraws from these agreements, it disrupts international cooperation and could encourage others to reduce or abandon their own commitments (Zhang et al., 2017). Meeting future U.S. emission reduction targets will necessitate significant transformations across various sectors, including energy, transportation, agriculture, and finance, requiring both domestic and international cooperation (Tollefson, 2021).

3.4. Implications for UN COP30 in Brazil (2025)

The 2025 United Nations Climate Change Conference (UNFCCC COP30), to be held in Brazil, represents a crucial moment for global climate action. As climate change concerns escalate, the summit offers nations an opportunity to assess progress and intensify efforts to meet the Paris Agreement’s goals. The persistent uncertainties surrounding U.S. adherence to international climate agreements significantly complicate matters. U.S. disengagement extends beyond emissions, encompassing substantial diplomatic, financial, and political ramifications. It could undermine international collaborative climate efforts and hinder global unity and effectiveness.

One of the foremost challenges preceding COP30 is the erosion of confidence in long-term climate finance commitments. There is diminished assurance regarding whether developed countries, particularly the U.S., will fulfill their pledges to provide funding for climate adaptation and mitigation projects in the Global South (Climate Home, 2023). This uncertainty may diminish the willingness of developing countries to engage, particularly if they perceive an inequitable burden-sharing. Trust forms the bedrock of international cooperation; without it, meaningful progress on global climate goals appears unattainable.

When the U.S. recedes from leadership, it severely impedes the collaborative framework that nations previously relied upon. The U.S. has historically been a key actor in convening stakeholders and shaping the architecture of international climate agreements. Its retreat has created a vacuum, leading to more fragmented diplomacy and more divided and tense negotiations (Victor et al., 2023). In the current climate, achieving consensus on complex issues such as carbon trading, climate finance, or addressing loss and damage becomes exceedingly difficult. The absence of the U.S. exacerbates the existing North-South divide in climate talks. The principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” (CBDR-RC) remains a contentious point. Many developing countries assert that wealthier, industrialized nations bear greater responsibility for climate change due to their historical emissions. Withdrawal from negotiations fosters a perception of unfairness and impedes collaborative efforts, harming the collective spirit necessary for serious global climate action (Keohane, 2023).

Brazil, as the host country, faces considerable diplomatic challenges given the prevailing geopolitical landscape. COP30 presents an opportunity for Brazil to demonstrate global leadership and assume corresponding responsibilities. Brazil should leverage its diplomatic influence to foster convergence between developed and developing countries, facilitating common ground through dialogue and collaboration. Its ability to bridge divides and mediate complex disagreements will be crucial for maintaining the integrity of the UNFCCC process (Kunio, 2024). Past conferences, such as COP21 in Paris, have demonstrated that substantive progress is contingent upon open and honest engagement from all participating nations (Halkyer, 2021).

Beyond diplomatic leadership, Brazil also has a significant opportunity to strengthen financial and technological linkages. The void left by the U.S. necessitates building stronger ties with other developed countries and international organizations. Brazil should advocate for innovative mechanisms to finance climate adaptation efforts in the Global South, while also promoting the sharing of clean technologies to enable vulnerable regions to transition towards greener, low-carbon solutions (Sharma & Payal, 2019). The global stocktake process within the Paris Agreement is a vital tool for assessing overall progress and identifying areas requiring further effort. Brazil can utilize this system to push for stronger commitments and mobilize support (Ochiai et al., 2023).

Furthermore, COP30 provides an opportune moment for Brazil to highlight its own sustainability efforts and domestic initiatives aimed at positive climate action. The country possesses unique advantages, including substantial renewable energy potential, vast forest areas, and rich biodiversity. By leading in reforestation, sustainable agriculture, and clean energy projects, Brazil can serve as an example for other developing countries striving to balance climate protection with economic growth (Herrera-Franco et al., 2024). Hosting both COP30 and the BRICS summit in 2025 places Brazil in the spotlight, emphasizing the critical importance of aligning its domestic policies with its global climate commitments (Kunio, 2024).

4. Conclusion and future prospects

The U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement during the Trump administration marked a significant turning point in global climate action. It not only disrupted the financial and institutional frameworks supporting global climate efforts but also diminished the political impetus required to sustain large-scale international cooperation. Such disengagement generates numerous challenges, including decelerated progress on emission reductions, eroded multilateral trust, and diminished stability in international climate efforts.

Some experts posit that a U.S. retreat from leadership might foster a more open and flexible climate system, allowing new actors and groups to exert greater influence, rather than being overshadowed by U.S. priorities (MacNeil, 2017). However, the tangible realities of substantial emissions and financial contributions remain paramount in shaping what is achievable. The U.S. has been one of the largest historical and contemporary sources of greenhouse gases (MacNeil, 2017). Its involvement is crucial for remaining within the global carbon budget necessary to limit warming to 1.5 °C. Protracted or recurrent U.S. disengagement would not only carry symbolic weight but could also impede global efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

From a scientific standpoint, there is unequivocal certainty regarding the immediate need for sustained and serious climate action. Delays in action, particularly from high-emitting nations, could push the planet past dangerous tipping points, such as the melting of polar ice, thawing permafrost, or the collapse of the Amazon rainforest, leading to irreversible damage to Earth’s systems. Inaction disproportionately increases the vulnerability of affected groups and erodes trust in the broader UNFCCC process.

As COP30 in Brazil approaches, the imperative for renewed global climate unity and action is clear. This summit represents a critical juncture to reorient global objectives, rebuild confidence in international cooperation, and achieve tangible outcomes that advance the goals of the Paris Agreement. Brazil, as host and a rising regional power, is strategically positioned to foster convergence among diverse nations, advocate for equitable climate solutions, and amplify voices from the Global South.

In summary, COP30 stands at a pivotal crossroads, offering both significant opportunities and potential pitfalls. It is not merely about addressing the repercussions of past decisions, such as the U.S. withdrawal. It must also serve as a catalyst for a more equitable, comprehensive, and evidence-based approach to climate action. The future of our planet is at stake. Failure to undertake strong, worldwide action now will lead to escalating climate change impacts, disproportionately affecting those who contributed least to the problem. Moving forward necessitates an unwavering focus on fairness, collaboration, and scientific integrity. A stable, livable planet for present and future generations can only be achieved through sustained global unity and inspiring leadership.

There remain significant gaps in our understanding. For example, there is insufficient knowledge regarding how ongoing political instability affects the long-term adherence to climate agreements. The effectiveness of decentralized leadership models in the absence of a clear dominant nation also requires further elucidation. Furthermore, there is a need for improved mechanisms to ensure equitable distribution of climate finance, especially for the most vulnerable populations. Practical frameworks for providing support for loss and damage in vulnerable areas are also lacking. Lastly, as some nations recede from global leadership, the evolving roles of sub-national governments and non-governmental organizations in bridging these governance gaps demand greater clarity. Future research is required to examine how global stocktake outcomes can be more effectively translated into concrete national policies and implementation plans. Moreover, further empirical research is essential to evaluate the alignment between countries’ climate commitments and actual emission trajectories, particularly given the observed policy volatility in major emitting economies.

Ethical statement

This review received no specific grant from funding agencies.

Conflicts of interest

None conflict of interest.

References

- Alessi, L., Battiston, S., & Kvedaras, V. (2024). Over with carbon ? Investors ’ reaction to the Paris Agreement and the US. Journal of Financial Stability, 71(August 2022), 101232. [CrossRef]

- Bodansky, D. (2021). The Art and Craft of International Environmental Law. Harvard University Press.

- Bodansky, D., & Rajamani, L. (2018). The evolution and governance architecture of the United Nations climate change regime. Global Climate Policy: Actors, Concepts, and Enduring Challenges, 13-66.

- Chinoko, V., Olago, D., Outa, G. O., Oguge, N. O., & Ouma, G. (2025). Prevailing Equity and Fairness Perceptions of African LDCs under the Paris Agreement Regime. 14(2), 185–205. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Wang, L., Chen, W., Luo, Y., Wang, Y., & Zhou, S. (2018). The global impacts of US climate policy: a model simulation using GCAM-TU and MAGICC. Climate Policy, 18(7), 852–862. [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, A., & Collins, A. M. (2025). Trumpism and the rejection of global climate governance. International Relations, 39(1), 76-100.

- Falkner, R. (2020). The Politics of International Climate Cooperation. Oxford University Press.

- Grigoroudis, E., Kanellos, F., Kouikoglou, V. S., & Phillis, Y. A. (2018). The challenge of the Paris Agreement to contain climate change. Intelligent Automation and Soft Computing, 24(2), 319–330. [CrossRef]

- Falkner, R., Stephan, H., & Vogler, J. (2010). International Climate Policy after Copenhagen : Towards a ‘ Building Blocks ’ Approach. 1(3), 252–262. [CrossRef]

- Hai-bin, Z., Han-cheng, D. A. I., Lai, H., & Wen-tao, W. (2017). U . S . withdrawal from the Paris Agreement : Reasons , impacts , and China ’ s response. Advances in Climate Change Research, 8(4), 220–225. [CrossRef]

- Halkyer, R. O. (2021). COP 21 – Complaints and Negotiation: The Role of the Like-Minded Developing Countries Group (LMDC) and the Paris Agreement. In Negotiating the Paris Agreement (pp. 160–181). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Havukainen, M., Mikkilä, M., & Kahiluoto, H. (2022). Global climate as a commons – Decision making on climate change in least developed countries. Environmental Science & Policy, 136, 761–.

- Herrera-Franco, G., Bravo-Montero, Lady, Caicedo-Potosí, J., & Carrión-Mero, P. (2024). A Sustainability Approach between the Water–Energy–Food Nexus and Clean Energy. Water, 16(7), 1017. [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Jacob, D., Taylor, M., Guillén Bolaños, T., Bindi, M., Brown, S., ... & Zhou, G. (2019). The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 C. Science, 365(6459), eaaw6974.

- Horton, J. B., Smith, W., & Keith, D. W. (2025). Who could deploy stratospheric aerosol injection? The United States, China, and large-scale planetary cooling. Global Policy, *16*(3), 410–422. [CrossRef]

- IEA (2022). World Energy Outlook 2022. International Energy Agency.

- IPCC (2023). Sixth Assessment Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Jotzo, F., Depledge, J., & Winkler, H. (2018). US and international climate policy under President Trump. 3062. [CrossRef]

- Kunio, U. (2024). Japan-Brazil Relations at a Time of Historical Change in the International Order: With G20 Summit, COP30, and BRICS Summit in Mind. Asia-Pacific Review, 31(2), 117–138. [CrossRef]

- 771. [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Yue, X.-G., Qin, M., & Norena-Chavez, D. (2024). Towards Paris Climate Agreement goals: The essential role of green finance and green technology. Energy Economics, 129, 107273. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Hanson-Wright, B., Dowlatabadi, H., & Zhao, J. (2023). How does personalized feedback on carbon emissions impact intended climate action? Environment, Development and Sustainability, 27(2), 3593–3607. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Allen, Heleen de Coninck, Opha Pauline Dube, Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, Daniela Jacob, Kejun Jiang, Aromar Revi, Joeri Rogelj, Joyashree Roy, Drew Shindell, William Solecki, Michael Taylor, Petra Tschakert, Henri Waisman, Sharina Abdul Halim, Philip Antwi-, 2018. (n.d.). Technical Sunnary. In: Global warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the th.

- MacNeil, R. (2025). The case for a permanent US withdrawal from the Paris Accord. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, O., Poulter, B., Seifert, F. M., Ward, S., Jarvis, I., Whitcraft, A., Sahajpal, R., Gilliams, S., Herold, M., Carter, S., Duncanson, L. I., Kay, H., Lucas, R., Wilson, S. N., Melo, J., Post, J., Briggs, S., Quegan, S., Dowell, M., … Rosenqvist, A. (2023). Towards a roadmap for space-based observations of the land sector for the UNFCCC global stocktake. iScience, 26(4), 106489. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2021). Climate Finance in 2020. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Pavone, I. R. (2018). The Paris Agreement and the Trump administration: Road to nowhere? Journal of International Studies, 11(1), 34–49. [CrossRef]

- Savaresi, A. (2016). The Paris Agreement : A New Beginning ?

- Sælen, H., Hovi, J., Sprinz, D., & Underdal, A. (2020). How US withdrawal might influence cooperation under the Paris climate agreement. Environmental Science & Policy, 108, 121–132. [CrossRef]

- Savaresi, A. (2016). The Paris Agreement: a new beginning?. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 34(1), 16-26.

- Sharma, P., & Payal, P. (2019). Climate Change and Sustainable Development: Special Context to Paris Agreement. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Sietsma, A. J., Theokritoff, E., Biesbroek, R., Canosa, I. V., Thomas, A., Callaghan, M., Minx, J. C., & Ford, J. D. (2024). Machine learning evidence map reveals global differences in adaptation action. One Earth, 7(2), 280–292. [CrossRef]

- Sorkar, M. N. I. (2020). Framing Shaping Outcomes: Issues Related to Mitigation in the UNFCCC Negotiations. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 13(3), 375–394. [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, I., Anderson, K., Capstick, S., Carton, W., Depledge, J., Facer, K., Gough, C., Hache, F., Hoolohan, C., Hultman, M., Hällström, N., Kartha, S., Klinsky, S., Kuchler, M., Lövbrand, E., Nasiritousi, N., Newell, P., Peters, G. P., Sokona, Y., … Spash, C. L. (2021). Three Decades of Climate Mitigation : Why Haven ’ t We Bent the Global Emissions Curve ? 653–689.

- Teklu, T. W. (2018). Should Ethiopia and least developed countries exit from the Paris climate accord? – Geopolitical, development, and energy policy perspectives. Energy Policy, 120, 402–417. [CrossRef]

- Tollefson, J. (2021). US pledges to dramatically slash greenhouse emissions over next decade. Nature, 592(7856), 673–673. [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC (2015). The Paris Agreement. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- Ullah, A., Pinglu, C., Khan, S., & Qian, N. (2025). Transition Towards Climate-Resilient Low-Carbon and Net-Zero Future Pathways: Investigating the Influence of Post-Paris Agreement and G-7 Climate Policies on Climate Actions in G-20 Using Quasi-Natural Experiments. Sustainable Development, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Victor, D.G., et al. (2023). Global Climate Governance and the Role of Major Powers. Nature Climate Change.

- von Allwörden, L. (2025). When contestation legitimizes: the norm of climate change action and the US contesting the Paris Agreement. International Relations, 39(1), 52-75.

- Yong-xiang, Z., Qing-chen, C., Qiu-hong, Z., & Lei, H. (2017). ScienceDirect The withdrawal of the U . S . from the Paris Agreement and its impact on global climate change governance. Advances in Climate Change Research, 8(4), 213–219. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-B., Dai, H.-C., Lai, H.-X., & Wang, W.-T. (2017). U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement: Reasons, impacts, and China’s response. Advances in Climate Change Research, 8(4), 220–225. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).