Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. State of Art

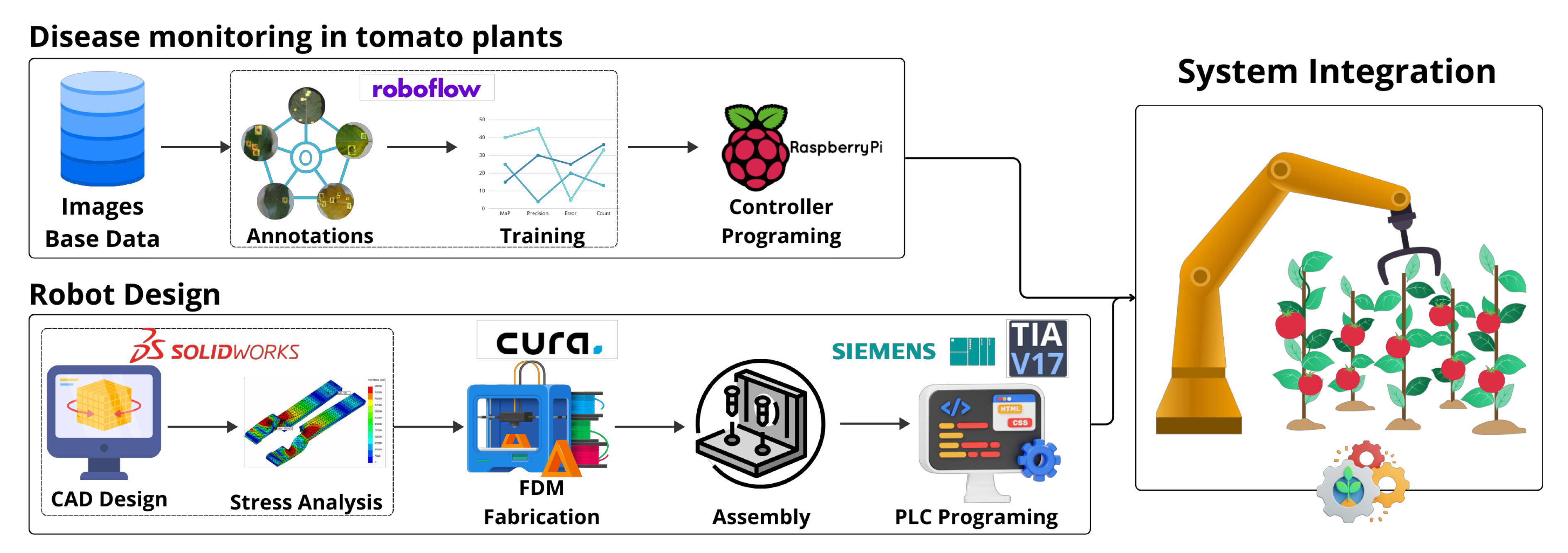

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Neural Network Methodology

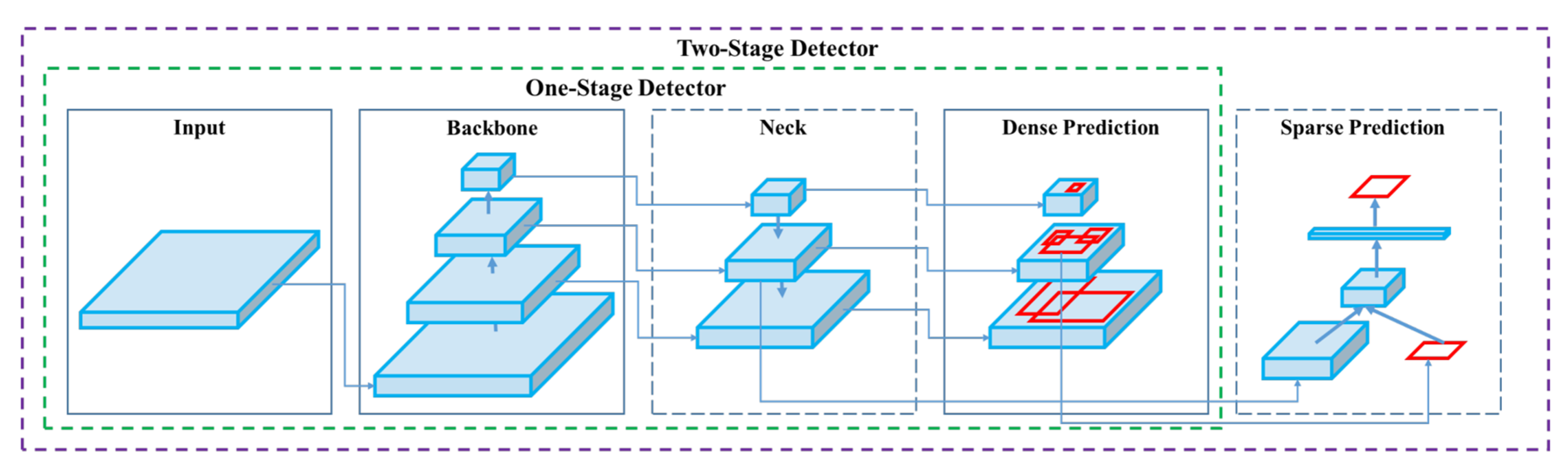

3.1.1. Detection Process

3.1.2. YOLOv5 Arquitecture

- Backbone - This is a convolutional neural network designed to aggregate and generate image features at various granularities. It forms the foundation for extracting meaningful information from input images.

- Neck - Comprising a series of layers, the neck is responsible for blending and amalgamating image features. Its role is crucial in preparing these features for subsequent prediction steps.

- Head - Taking input features from the neck, the head component executes the final steps of the process. It is responsible for making predictions related to bounding boxes and class labels, thus completing the object detection pipeline.

3.1.3. YOLO Training Procedures.

- Data Argumentation - This crucial step involves applying transformations to the foundational training data, expanding the model’s exposure to a broader spectrum of semantic variations beyond the isolated training set. By incorporating diverse transformations such as rotation, scaling, and flipping, data augmentation enhances the model’s robustness and adaptability to real-world scenarios.

- Loss Calculations - YOLOv5 employs a comprehensive approach to loss calculations, considering the Generalized Intersection over Union (GIoU), objectness (obj), and class losses. These loss functions are meticulously crafted to construct a total loss function. The objective is to maximize the mean average precision, a key metric in assessing the model’s precision-recall performance. Understanding and fine-tuning these loss functions contribute significantly to optimizing the model’s accuracy and predictive capabilities.

3.1.4. Data Augmentation in YOLOv5.

- Scaling - Adjustments in scale are applied to the training images, enabling the model to adapt to variations in object sizes and spatial relationships.

- Color Space Adjustments - Alterations in the color space of the images contribute to the model’s ability to generalize across different lighting conditions and color distributions.

- Mosaic Argumentation - A particularly innovative technique employed by YOLOv5 is mosaic data augmentation. In this approach, four images are combined into four tiles of random ratios. This method not only diversifies the training dataset but also challenges the model to comprehend and analyze complex scenes where multiple objects interact within a single image.

3.1.5. CSP Backbone (Cross Stage Partial).

3.1.6. PA-Net Neck.

- FPN - (Feature Pyramid Network): A pyramid-shaped hierarchical architecture for multi-scale feature representation.

- PAN -(Path Aggregation Network): Focused on aggregating features from different network paths to enhance information flow.

- NAS-FPN - (Neural Architecture Search - Feature Pyramid Network): Involves employing neural architecture search techniques to optimize the feature pyramid network.

- BiFPN - (Bi-directional Feature Pyramid Network): A bidirectional approach to feature pyramid networks, promoting effective information exchange.

- ASFF - (Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion): A mechanism for adaptively fusing spatial features to enhance object detection capabilities.

- SFAM - (Selective Feature Aggregation Module): A module designed for selectively aggregating features to improve the model’s discriminative power.

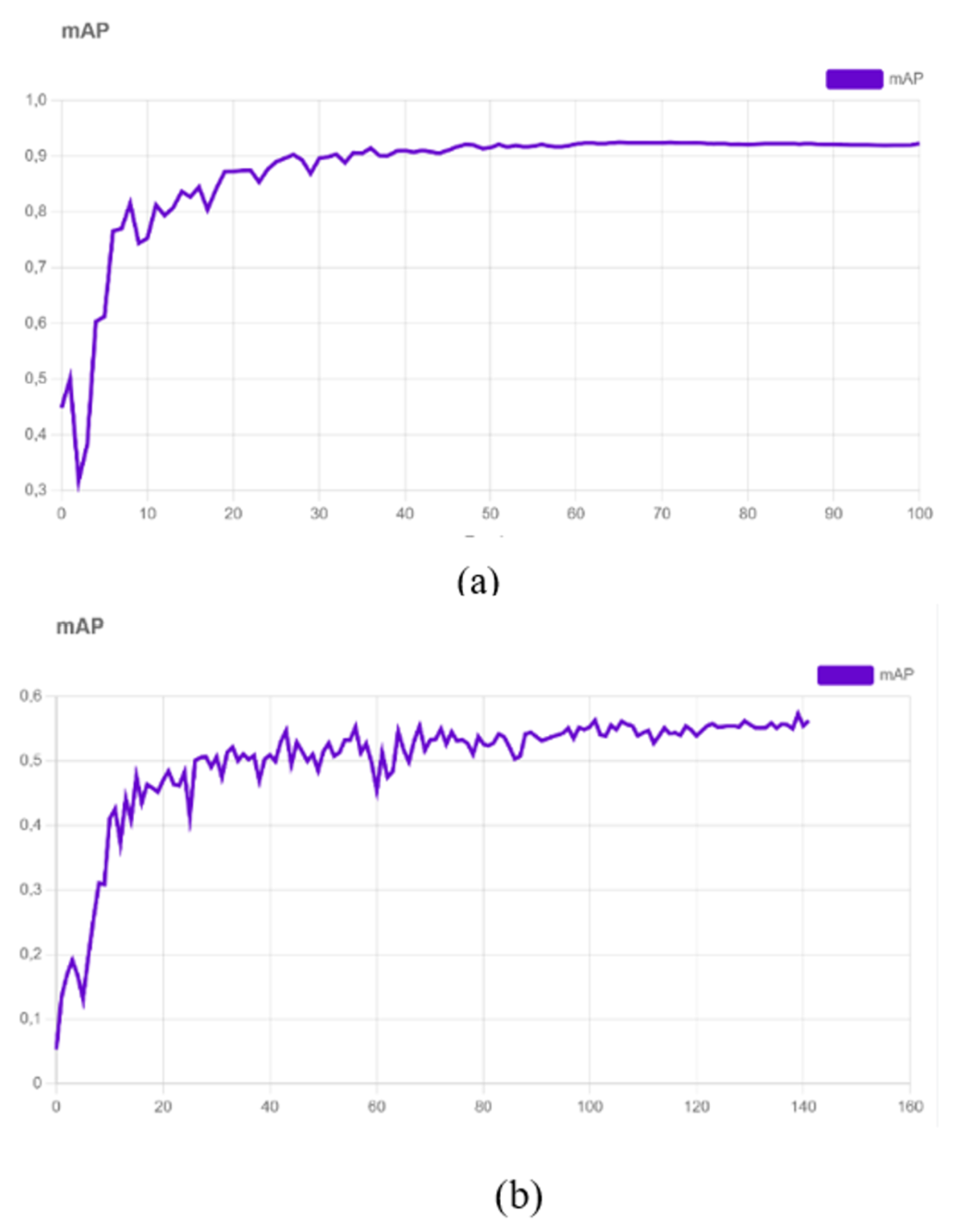

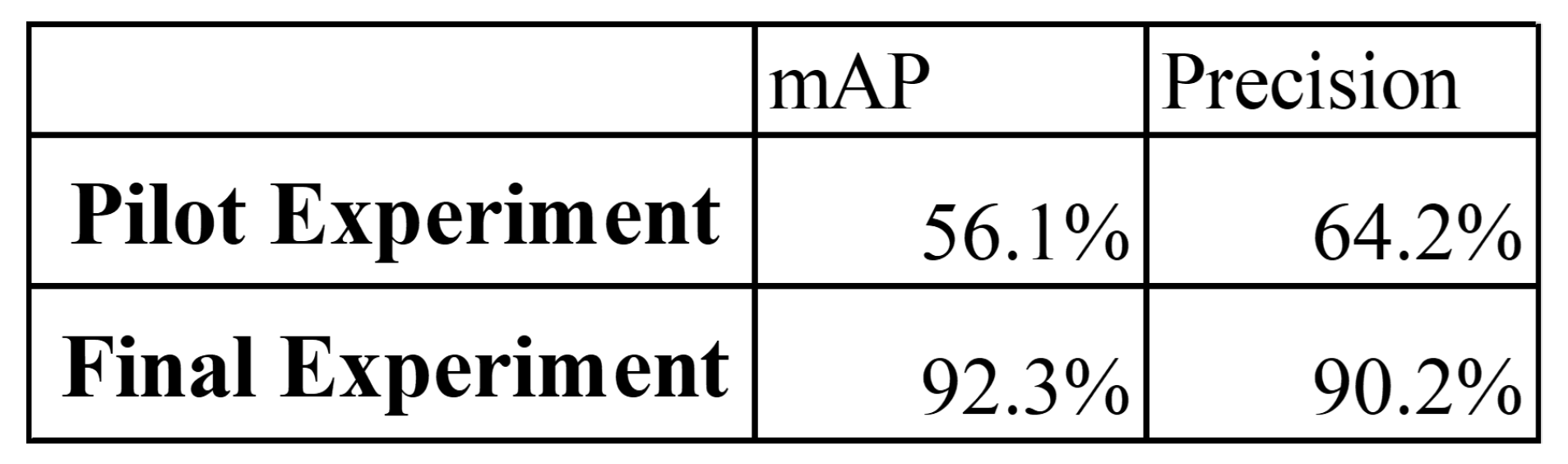

3.1.7. PILOT EXPERIMENT

3.1.8. Validity and Reproducibility

- It can be mentioned that the study presents a clear and detailed methodology for detecting plant diseases using deep transfer learning. The methods used seem to align with the study’s objective and are described with enough detail to allow study replication. However, there is no information on the validity of the data used in the study, which could impact the results. In general, more information is required to fully assess reproducibility and validity [38].

- The suggested model is addressed using data augmentation methods and capturing images in different environments and conditions. Reproducibility and validity are addressed through data augmentation techniques, careful selection of image data, and evaluation methods such as confusion matrices. However, it does not explicitly provide specific reproducibility algorithms or codes [35].

- A detailed description of the proposal and the experimental design used is provided, indicating measures taken to ensure the internal and external validity of the study. Sufficient details about the study proposal and the experimental design are given to enable other researchers to reproduce it. Simulation and experiment results are also presented, and both can be replicated using the same manipulator robot and experimental setup. Overall, while the study presents promising results, further research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of the proposal and assess its applicability in various contexts [39].

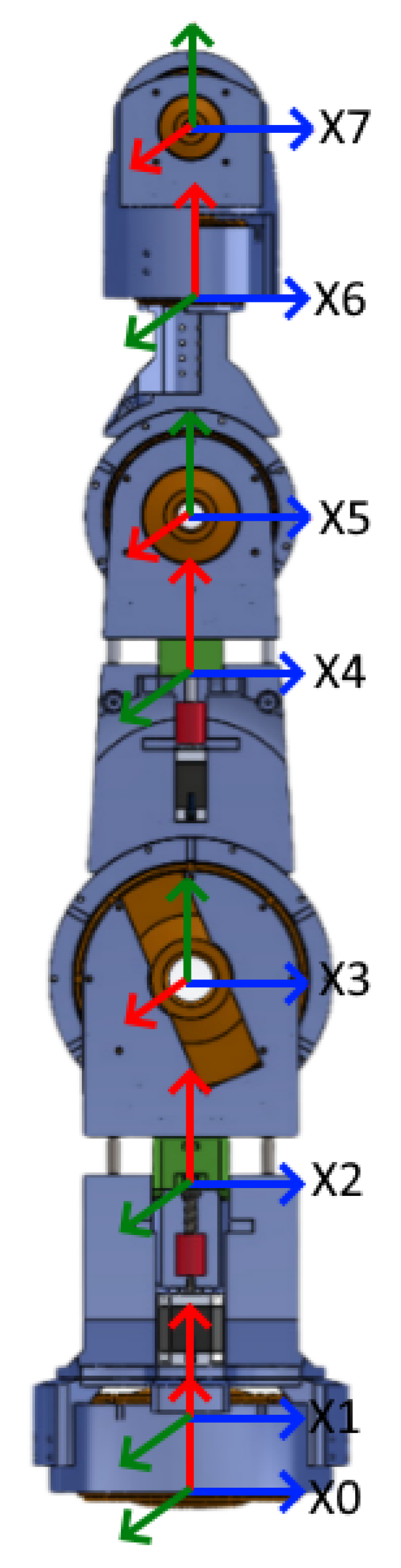

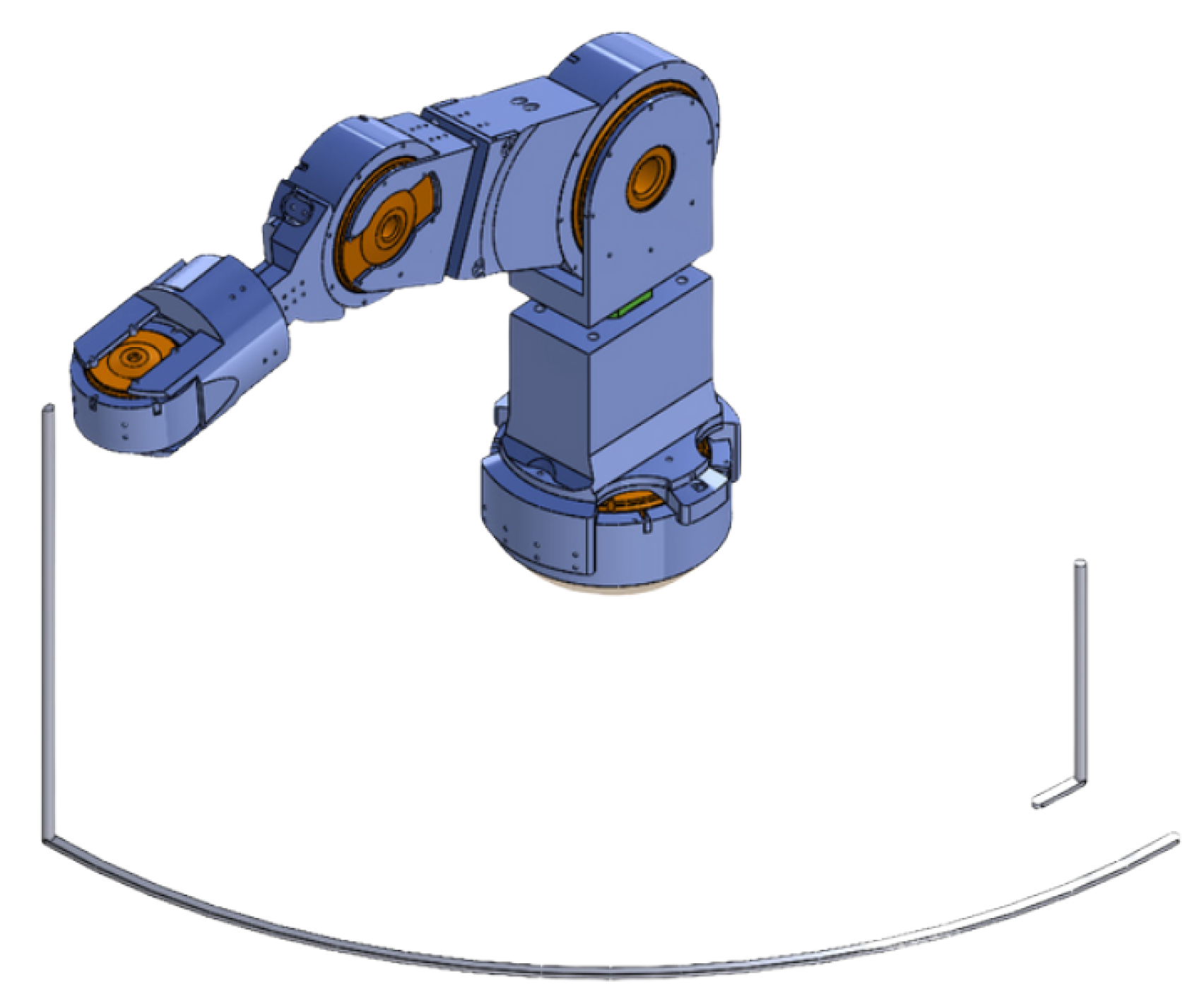

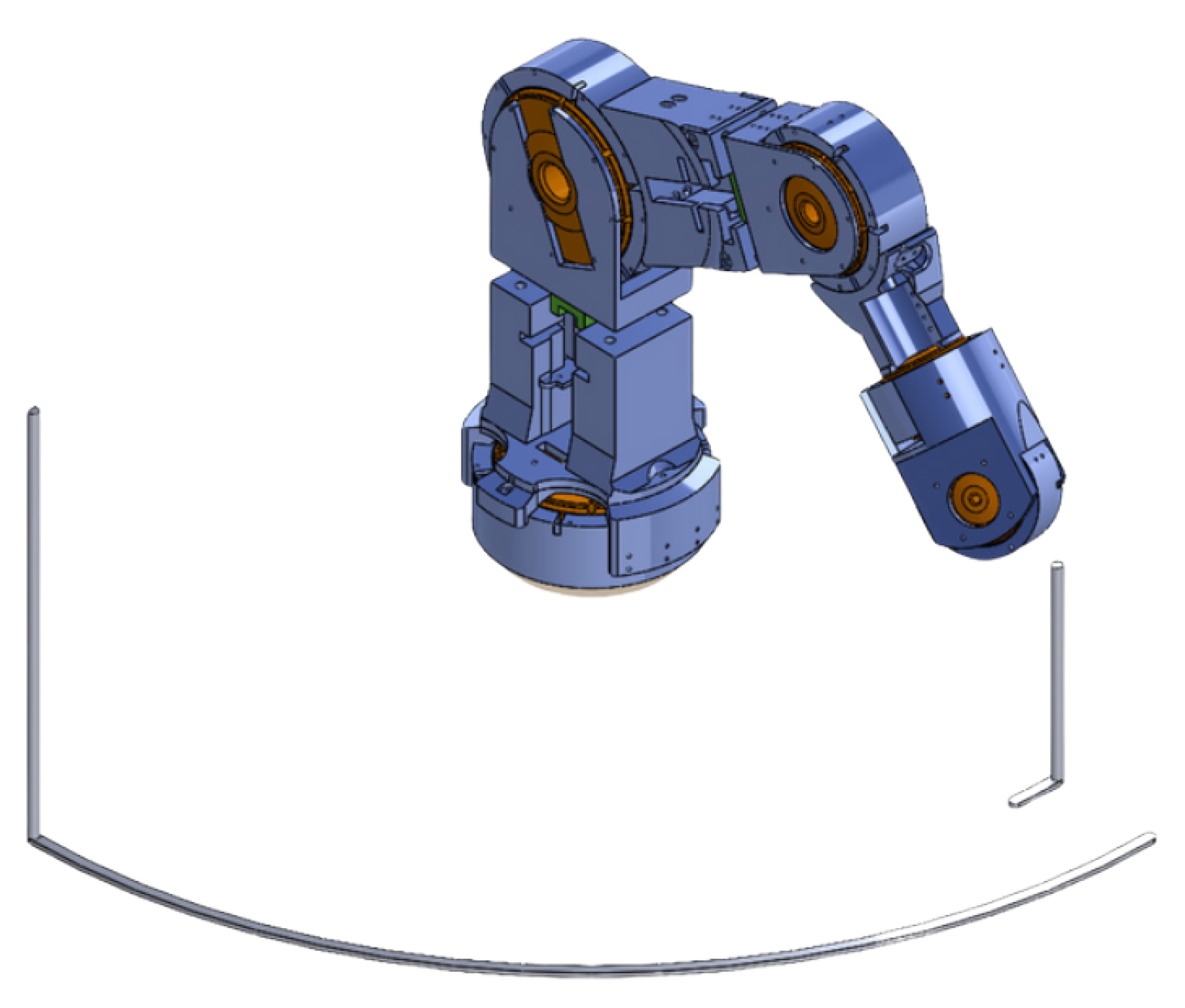

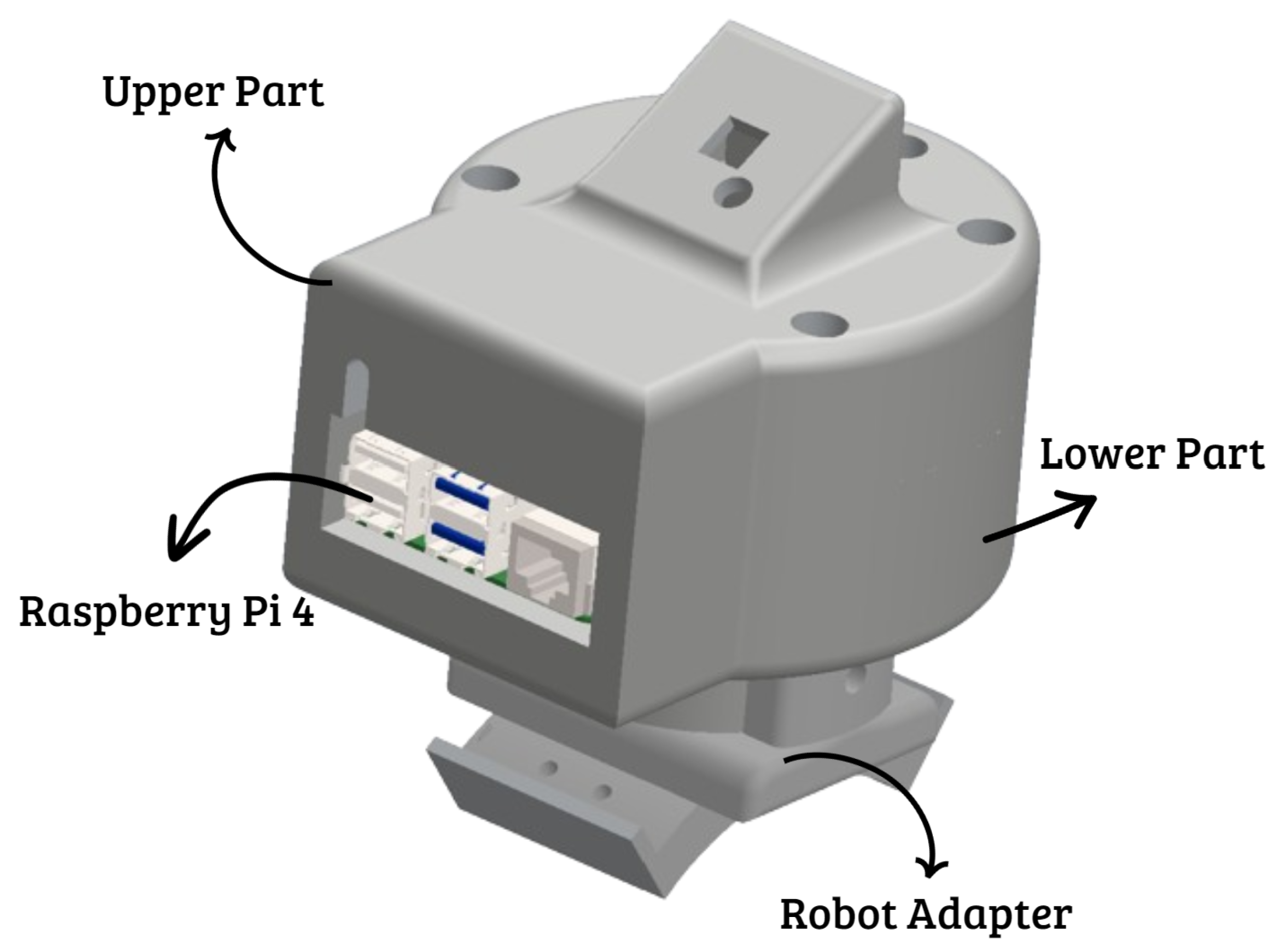

3.2. Robotic Arm Design and Manufacturing

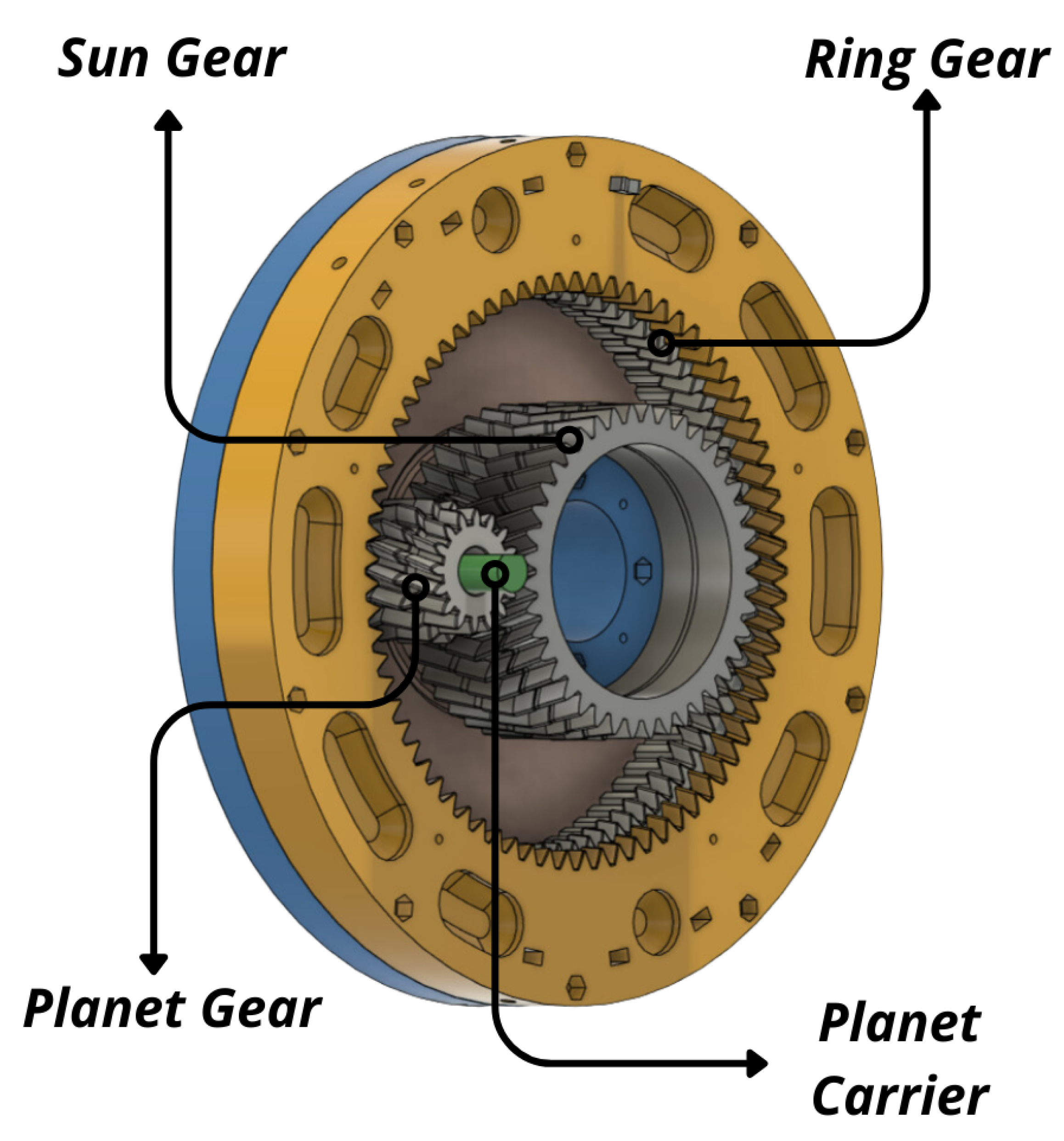

3.2.1. Cad Design

- Tr: Ring gear spin speed

- Ts: Planet spin speed

- Ty: Planet carrier spin speed

- R: Ring gear teeth

- S: Suns’s teeth

- S: Planet’s teeth

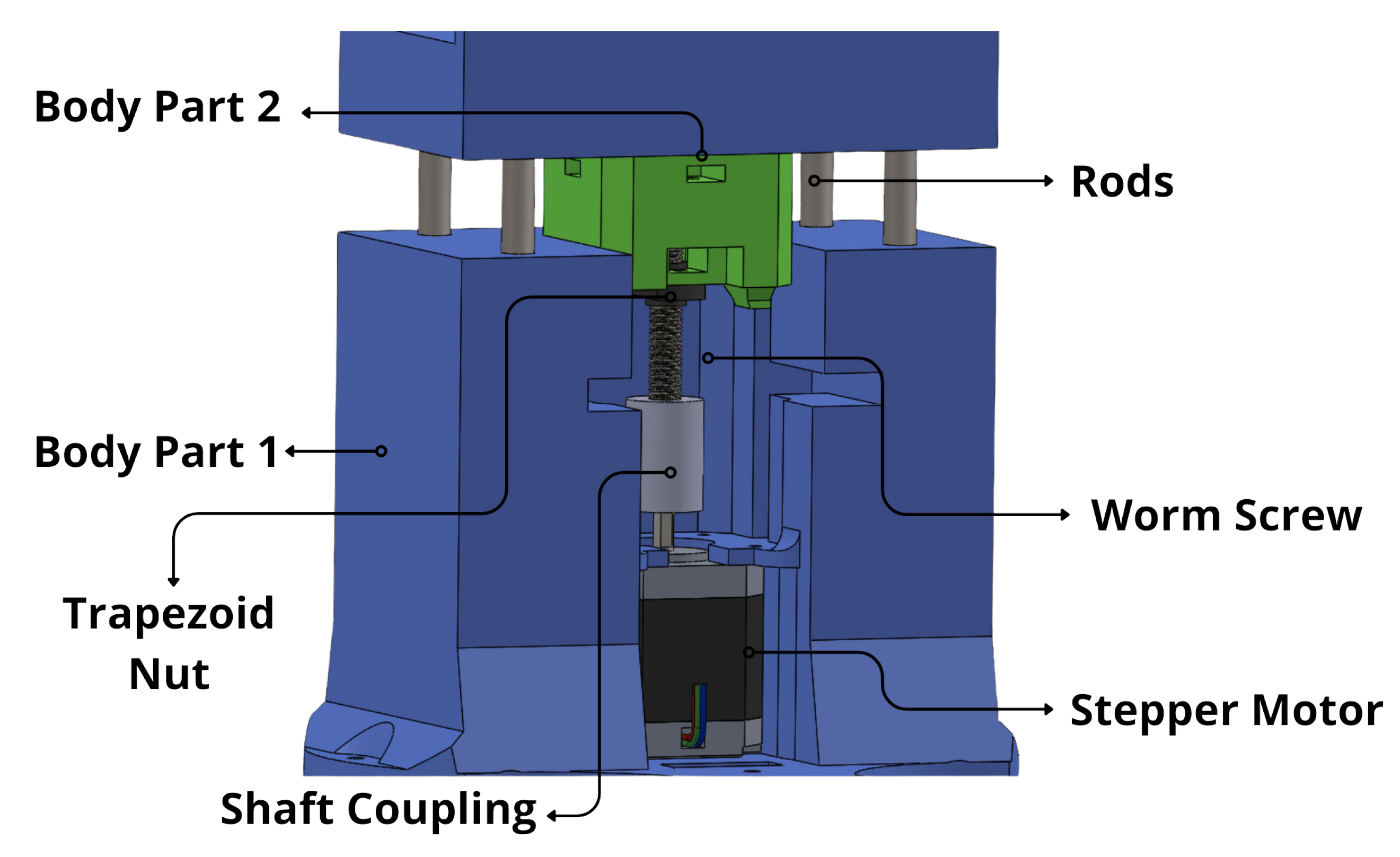

- PH Is the power required to move the material horizontally.

- PN is the power required to drive the screw in freewheeling operation.

- Pi is the power required for the case of an inclined worm screw.

- Q is the flow of transported material, in t/h

- H is the height of the installation, in m

- D is the diameter of the link section of the conveyor casing, in m

- C0 is the resistance coefficient of the transported material.

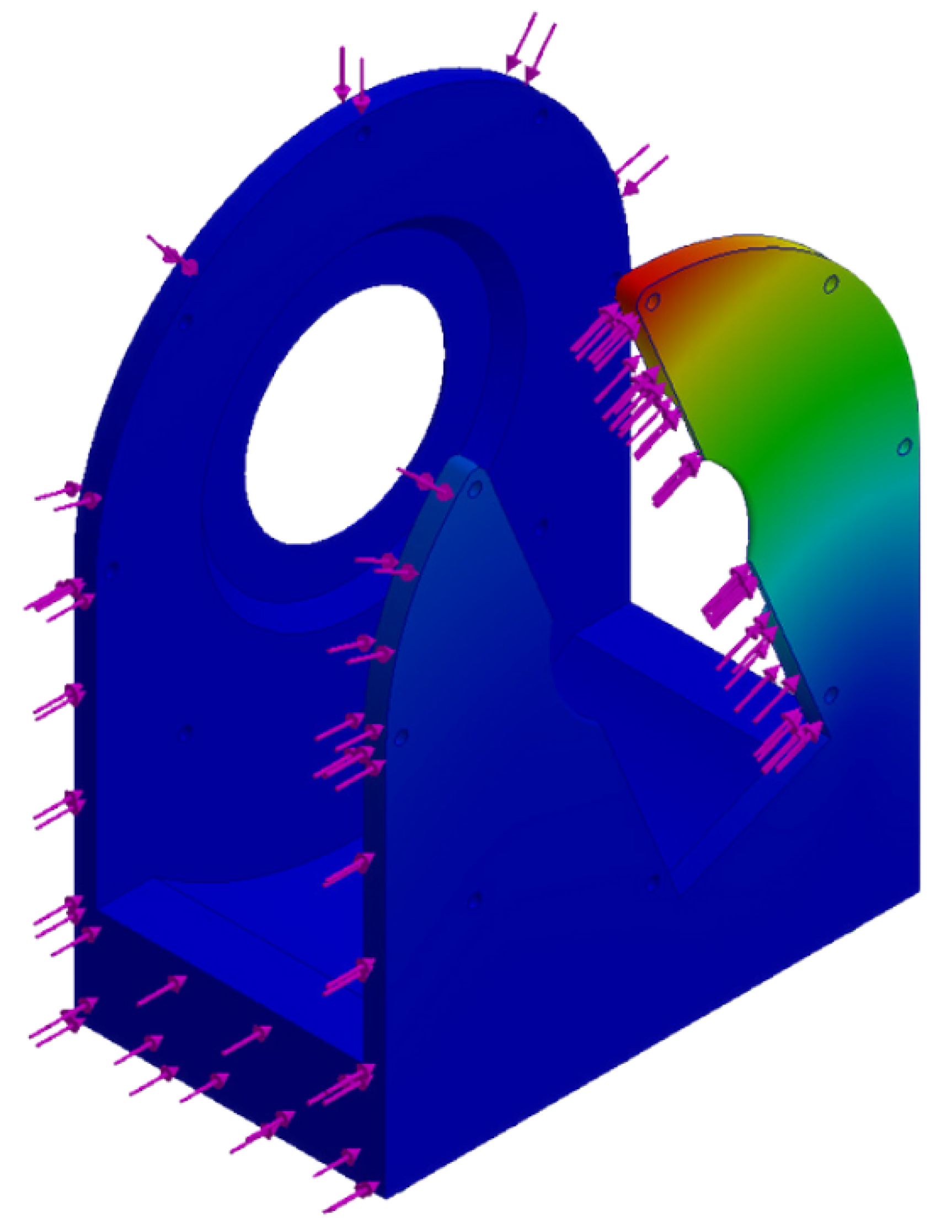

3.2.2. Motion and Stress Analysis

3.2.3. FDM Fabrication

- Step 1: Convert each of the CAD files individually to an STL extension format.

- Step 2: Obtain the 3D processing software CURA and install it on a PC, the version used for the fabrication of the parts was CURA 5.3.0.

- Step 3: Configuration in the software of each printer that will be used to manufacture the parts.

-

Step 4: General parameterization. In software, there are several configurations that the user can modify to his preference. For our parts manufacturing on both printers, we will use the same print settings profile except for the following parameters:- Layer height: When the parts to be manufactured are very small, it is required to have a layer height between 0.15mm and 0.10mm in order not to lose the shape and quality of the parts, and the larger the part, the less impact the layer height will have. A general recommended value would be a height greater than or equal to 0.2mm. The lower the value, the longer it will take the machine to manufacture the parts.- Number of external walls: This value is the number of external walls that the machine will make before starting with the shell-like filling; these walls provide rigidity to the torsion and therefore a better final finish where you do not get to see the inner filling pattern.- Infill: This parameter is the one that provides most of the rigidity to the parts and also the one that consumes the largest amount of manufacturing material, depending on the filling pattern applied to the parts.In the model, a percentage between 20 and 40 infill percentage was used in the parts in variation to their function and size. Pieces that perform mechanical work and undergo greater stress were given more infill.- Horizontal expansion: For this configuration, a test must be performed depending on the material; in this case, ABS was used. For this test, a cube measuring 20 x 20 x 20mm is made in order to measure if it has undergone an expansion or if the material is compressed. This happens due to temperature variations at the time of extruding the material through the nozzle of the printing machine and external conditions such as ambient temperature. Once the test is done, we proceed to measure with a vernier or a micrometer and see how much variation there is from the original measurements.In the test, it was verified that the material used expanded by 0.12 mm, and a parameter of -0.12 was applied to counteract this excess material.

-

Step 5: Prepare each piece in the CURA software. Once all the above is configured, each piece is added individually and processed in the software, giving us the weight data in grams and the printing time.Click on the save option, and the program will automatically generate a G-CODE file that must be saved on a microSD memory card.

- Step 6: Level the printer’s print bed manually.

- Step 7: Start printing each of the parts.

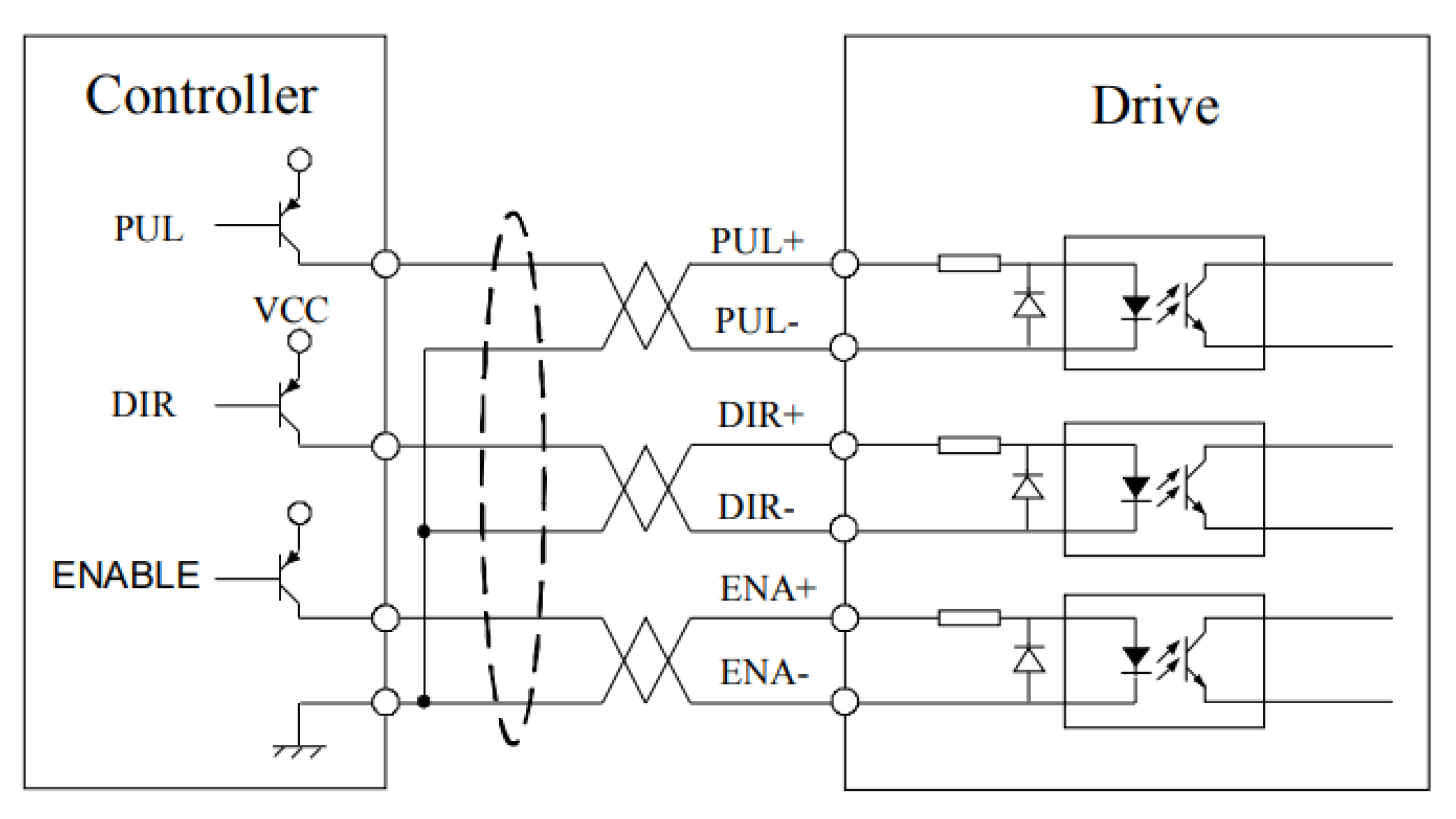

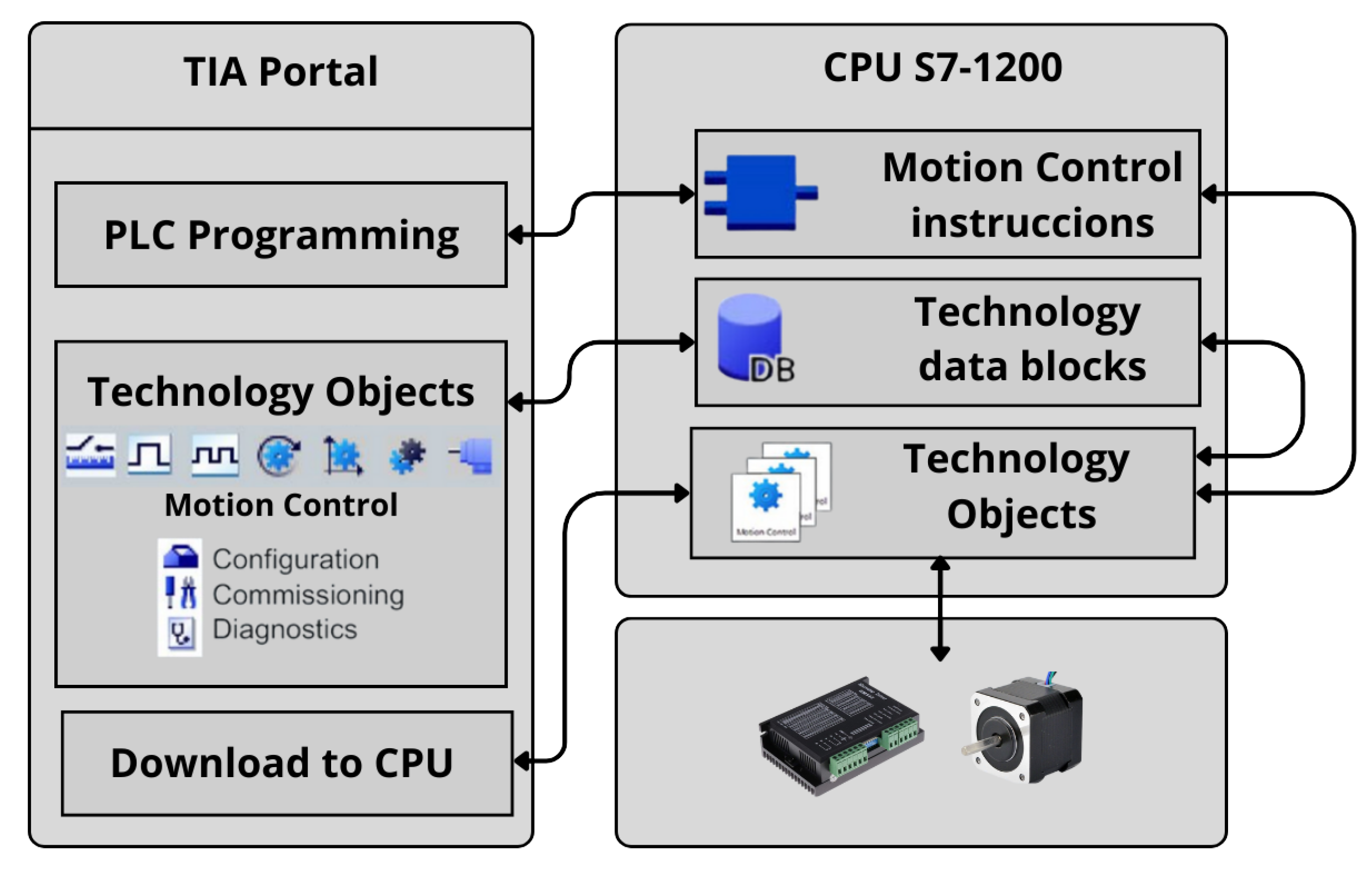

3.2.4. Robot Controller – PLC Programming

- SIMATIC S7-1200, CPU 1214 DC/DC/DC with firmware version 4.2

- SIMATIC S7-1200, CPU 1212 DC/DC/DC with firmware version 4.2

4. Results

4.1. Neural Network

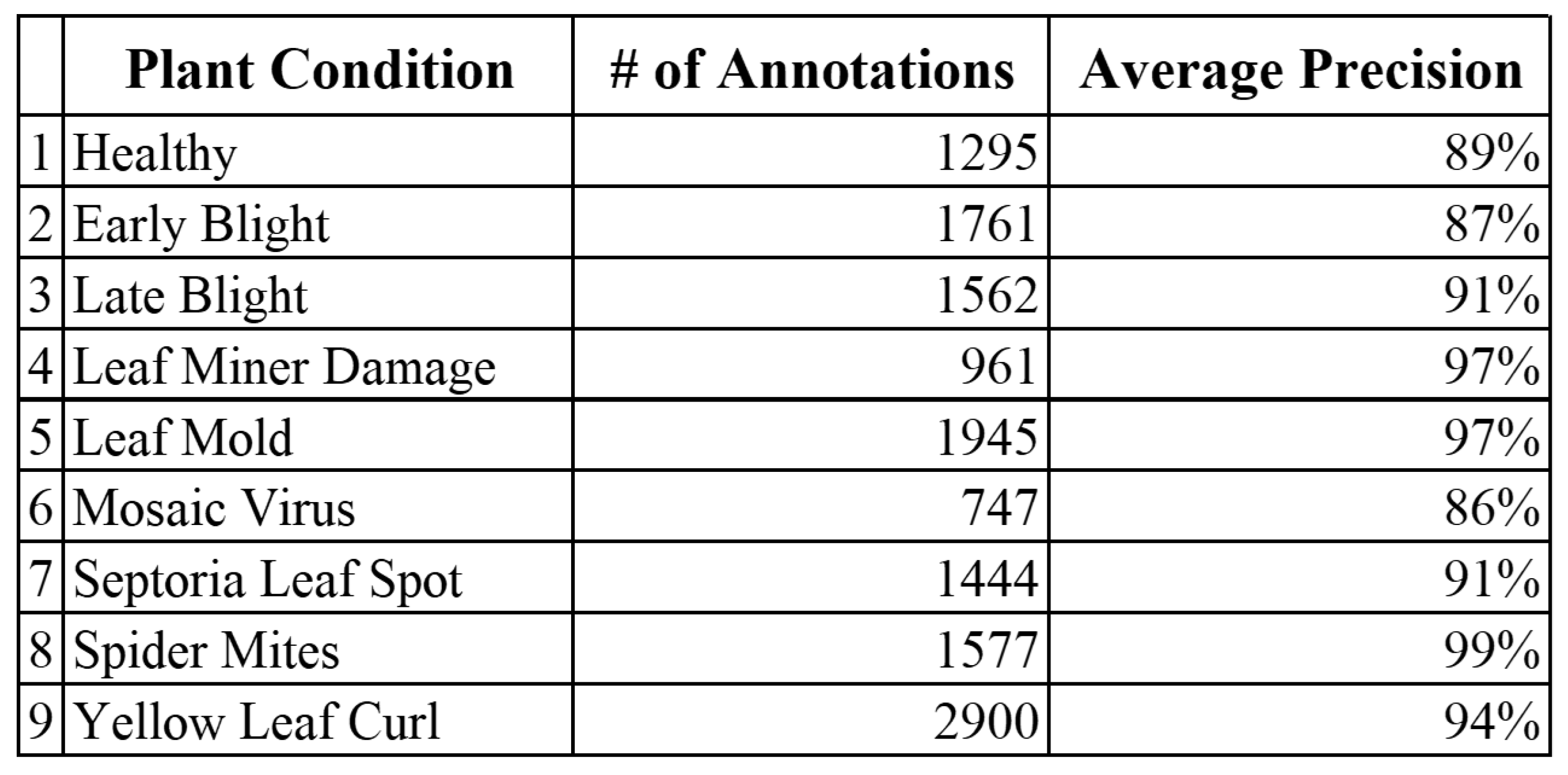

4.1.1. Precision and mAP

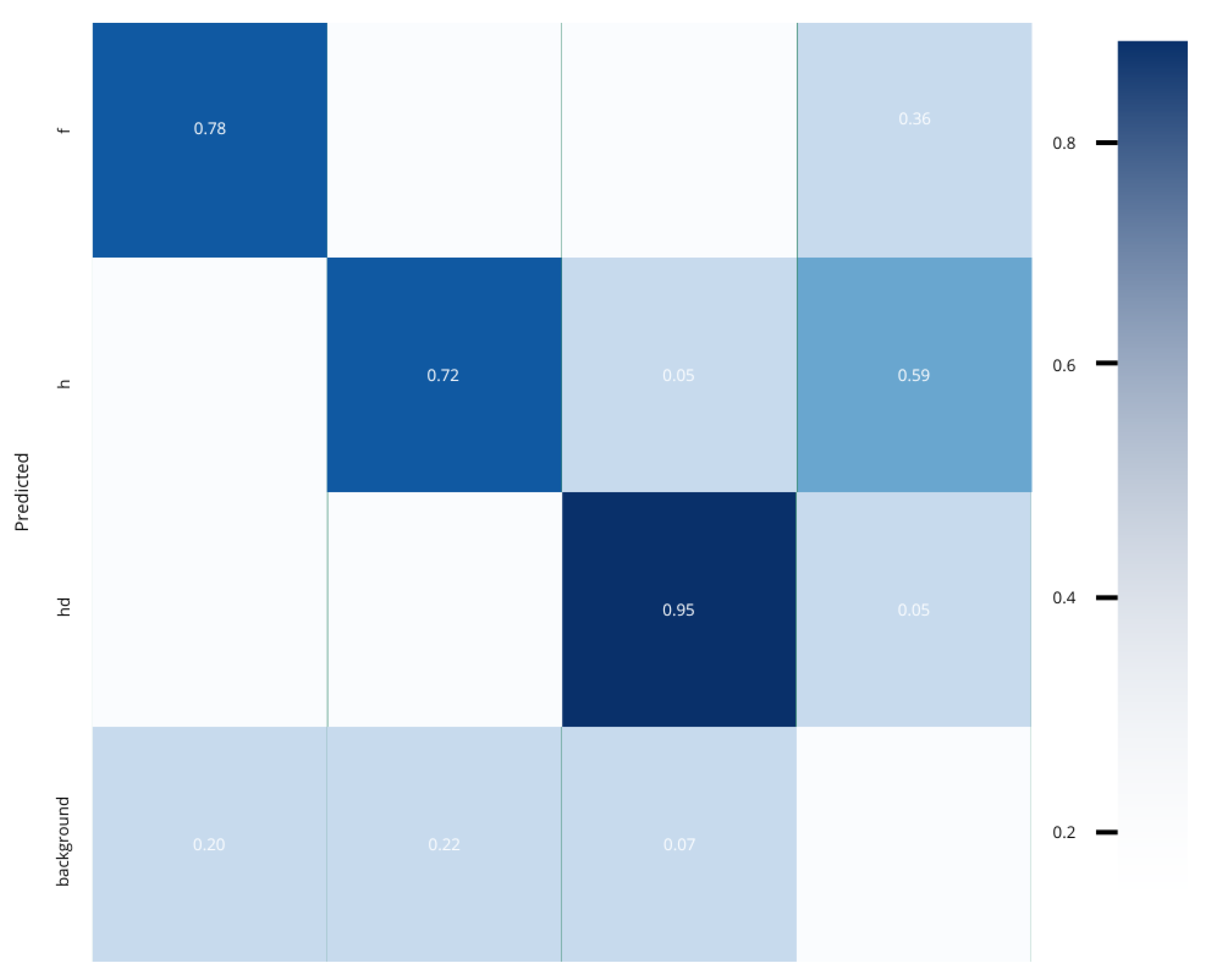

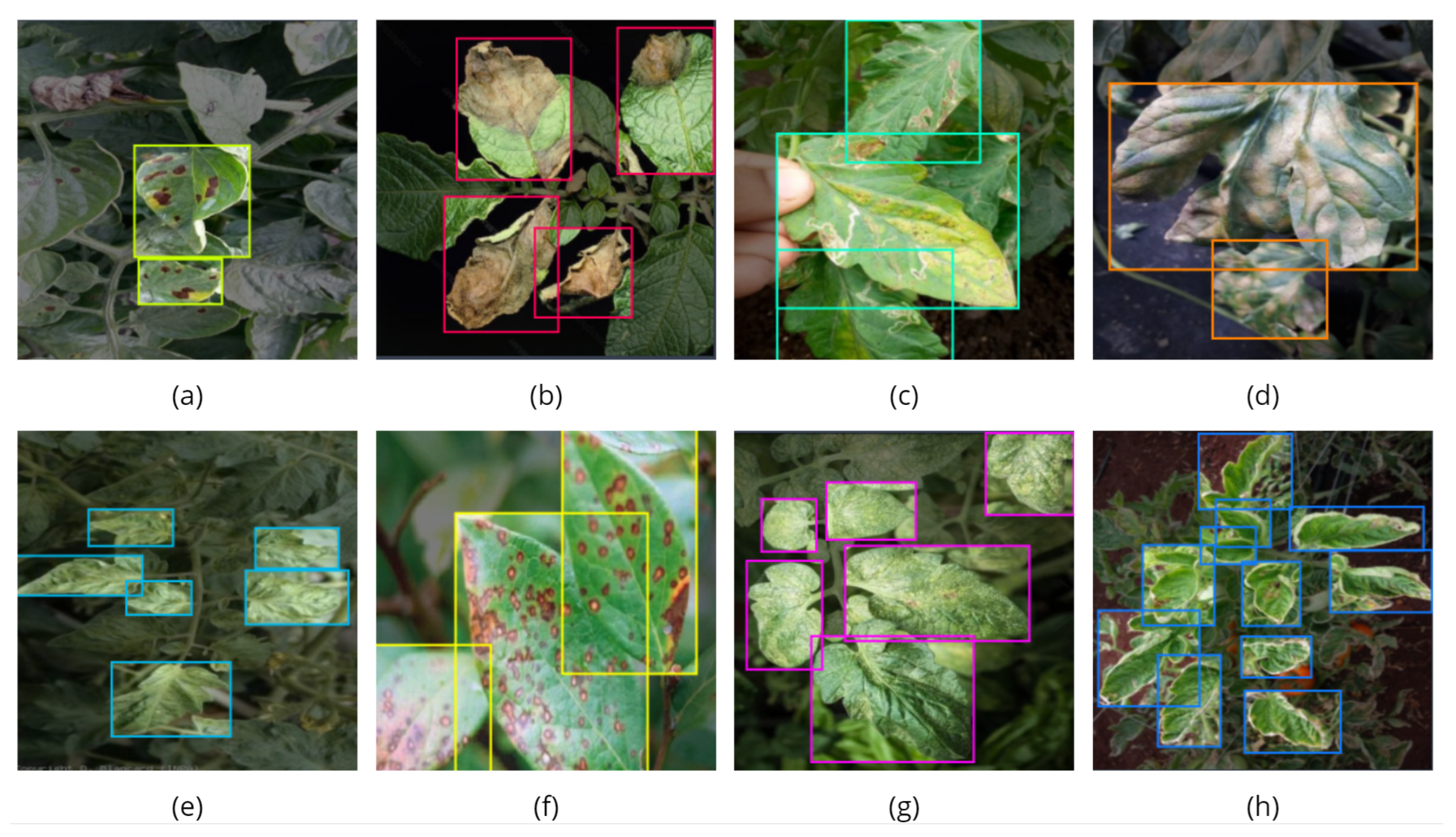

4.1.2. Disease Accuracy

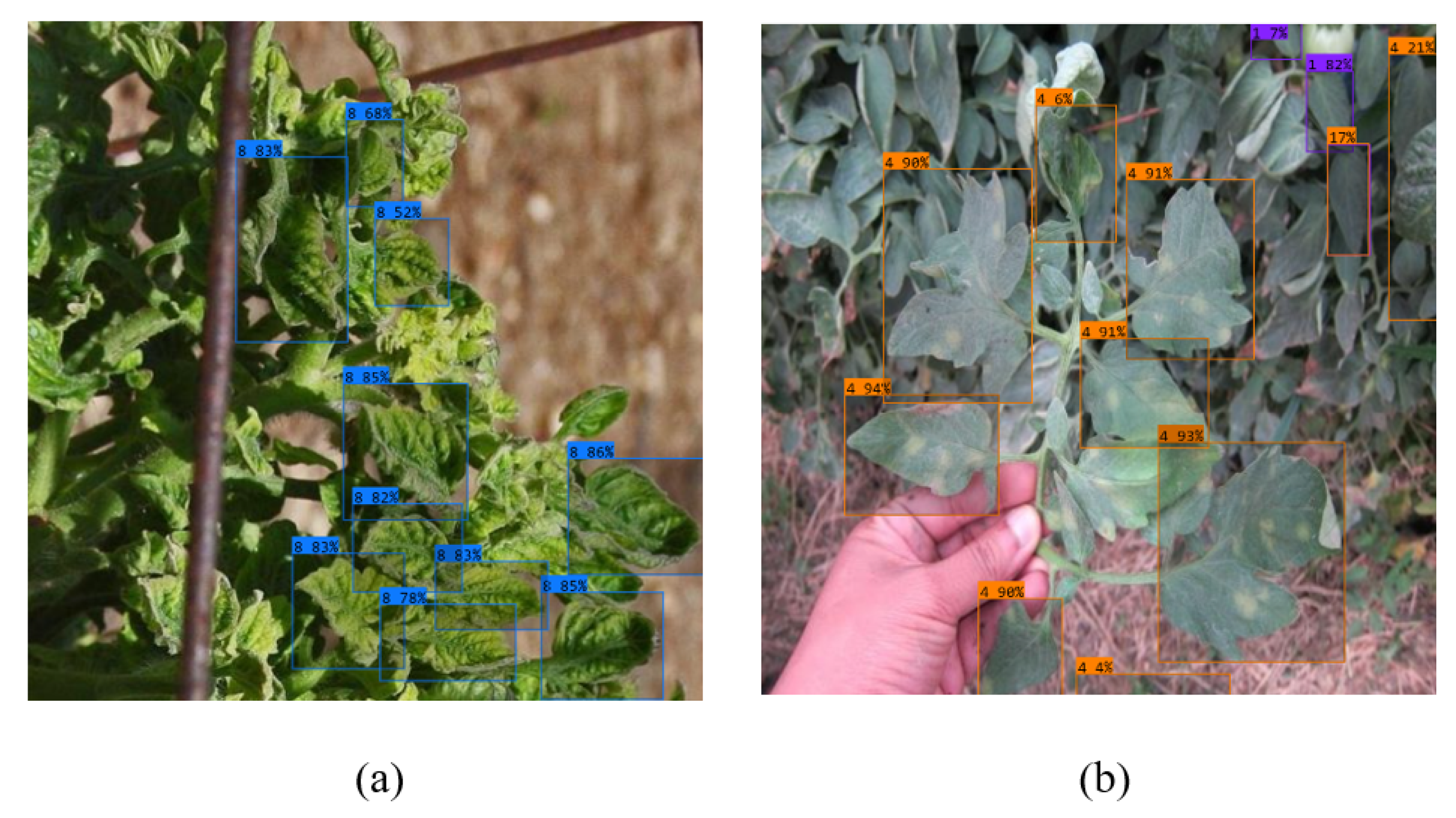

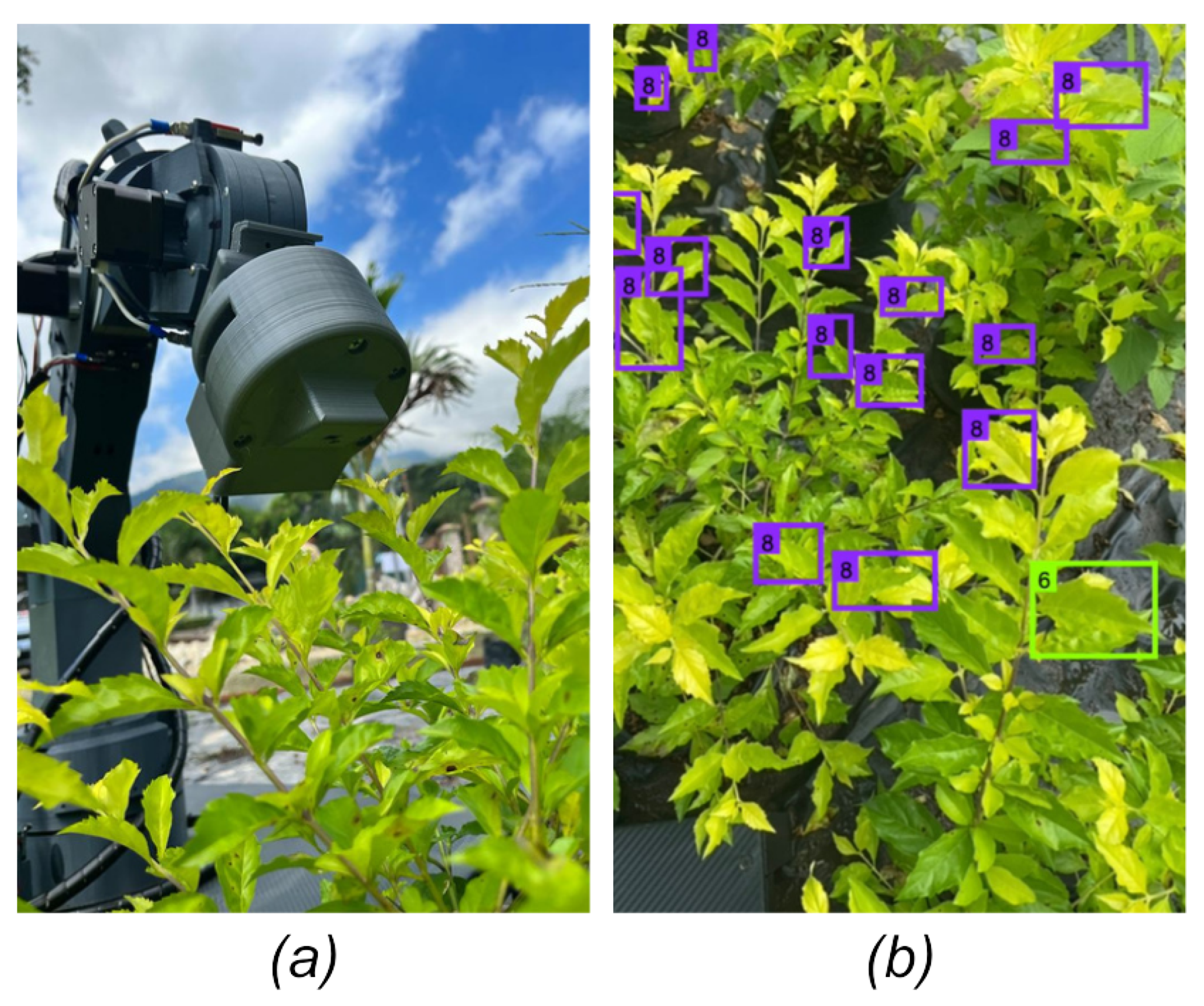

4.1.3. Real-Time Detection

4.2. End Effector

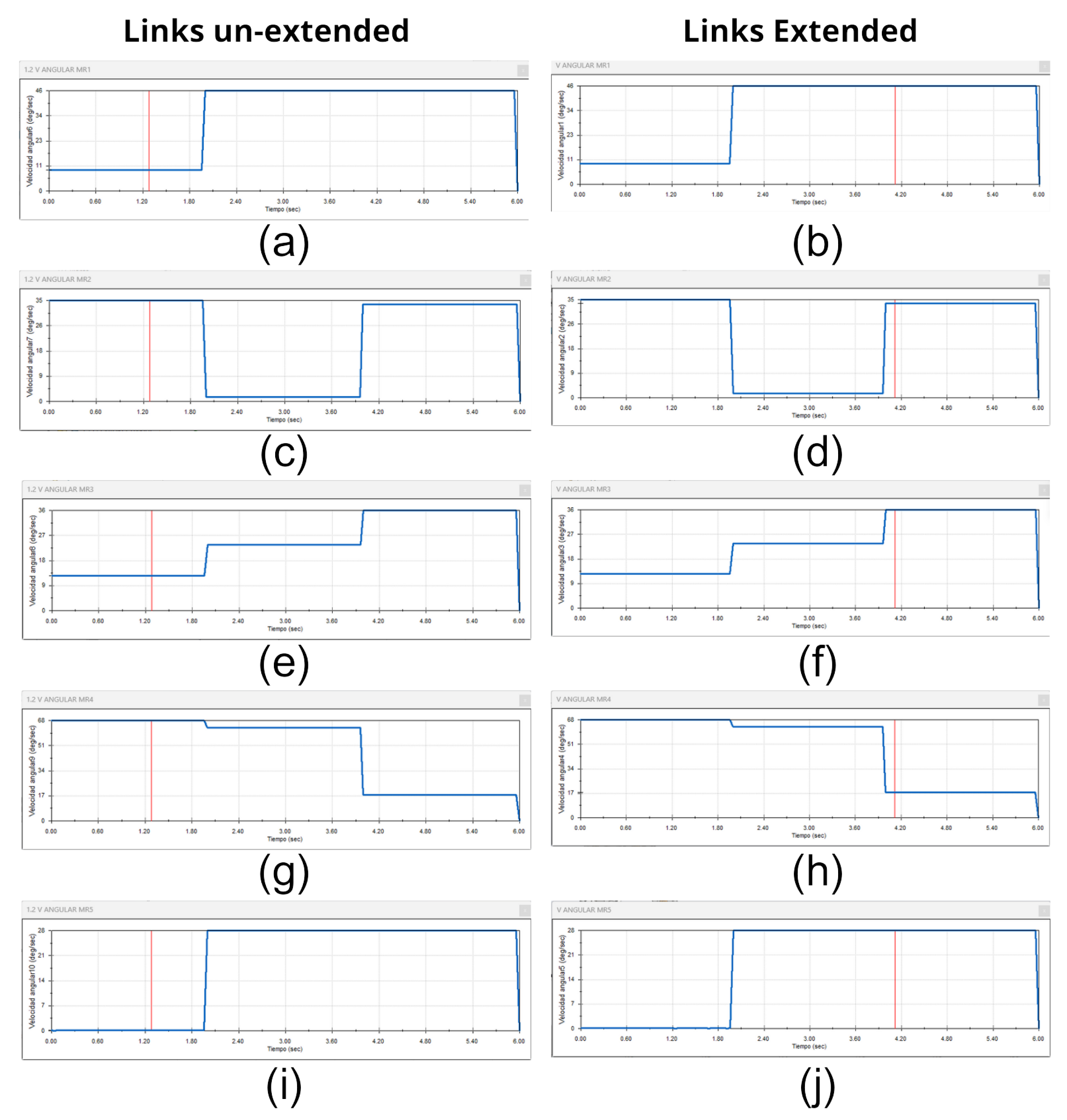

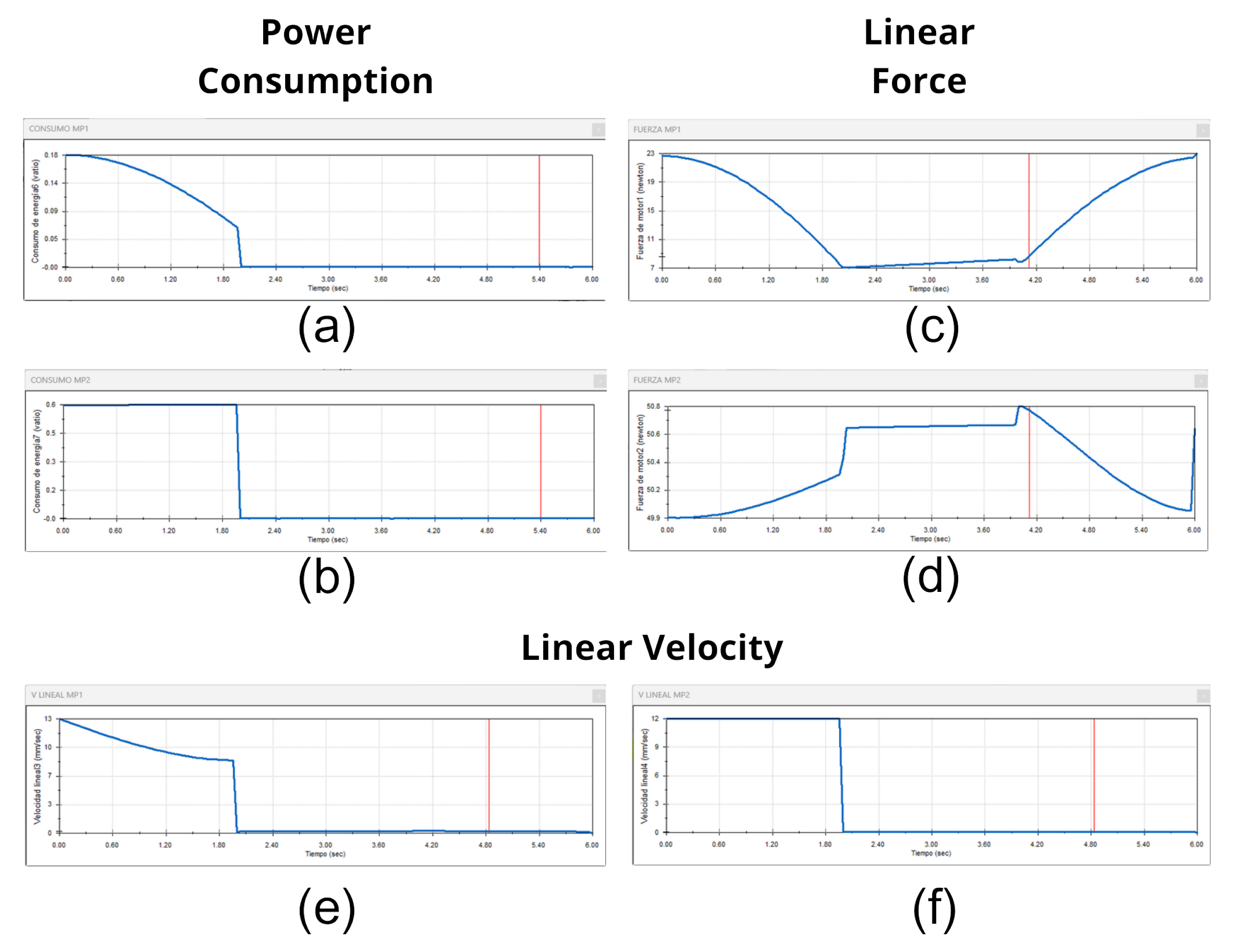

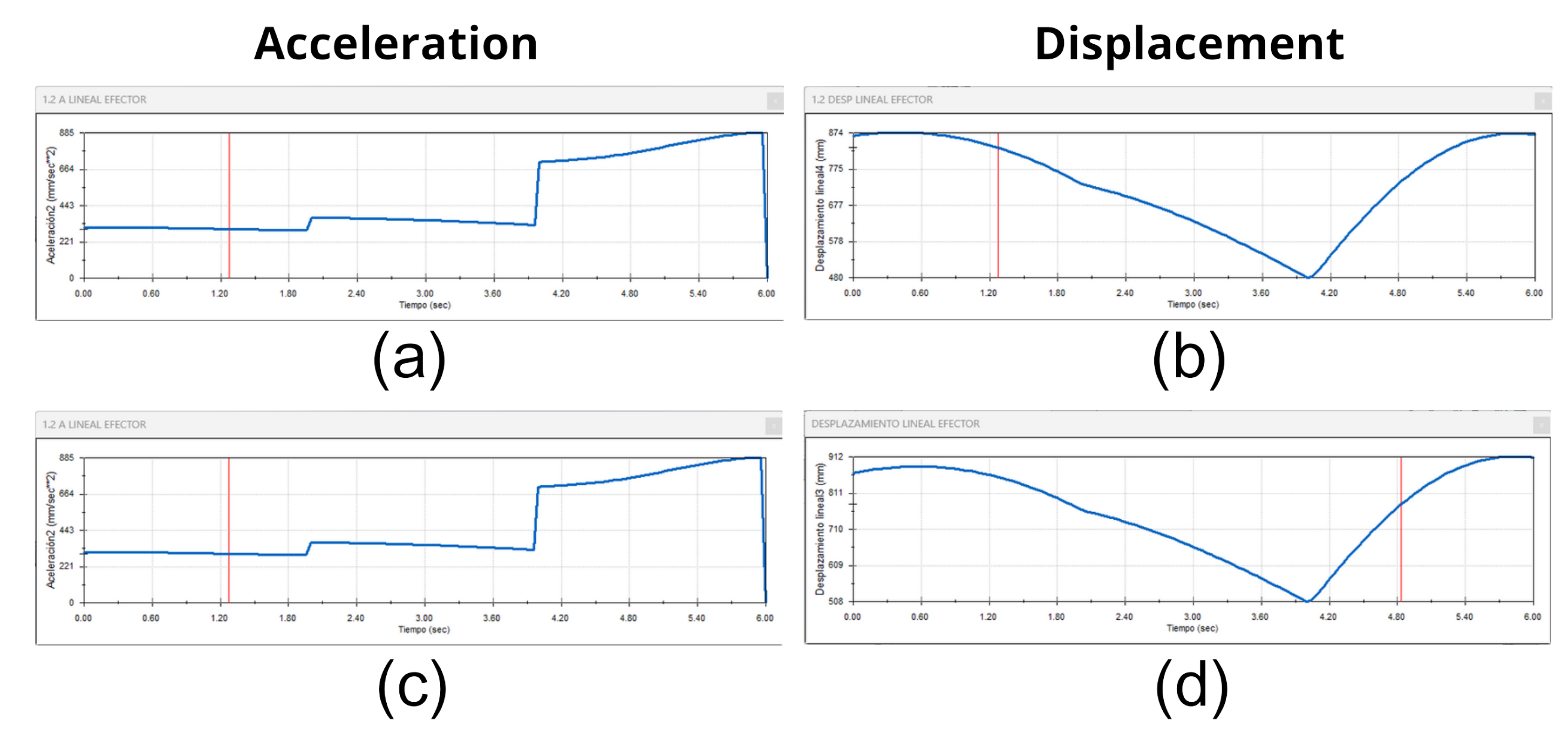

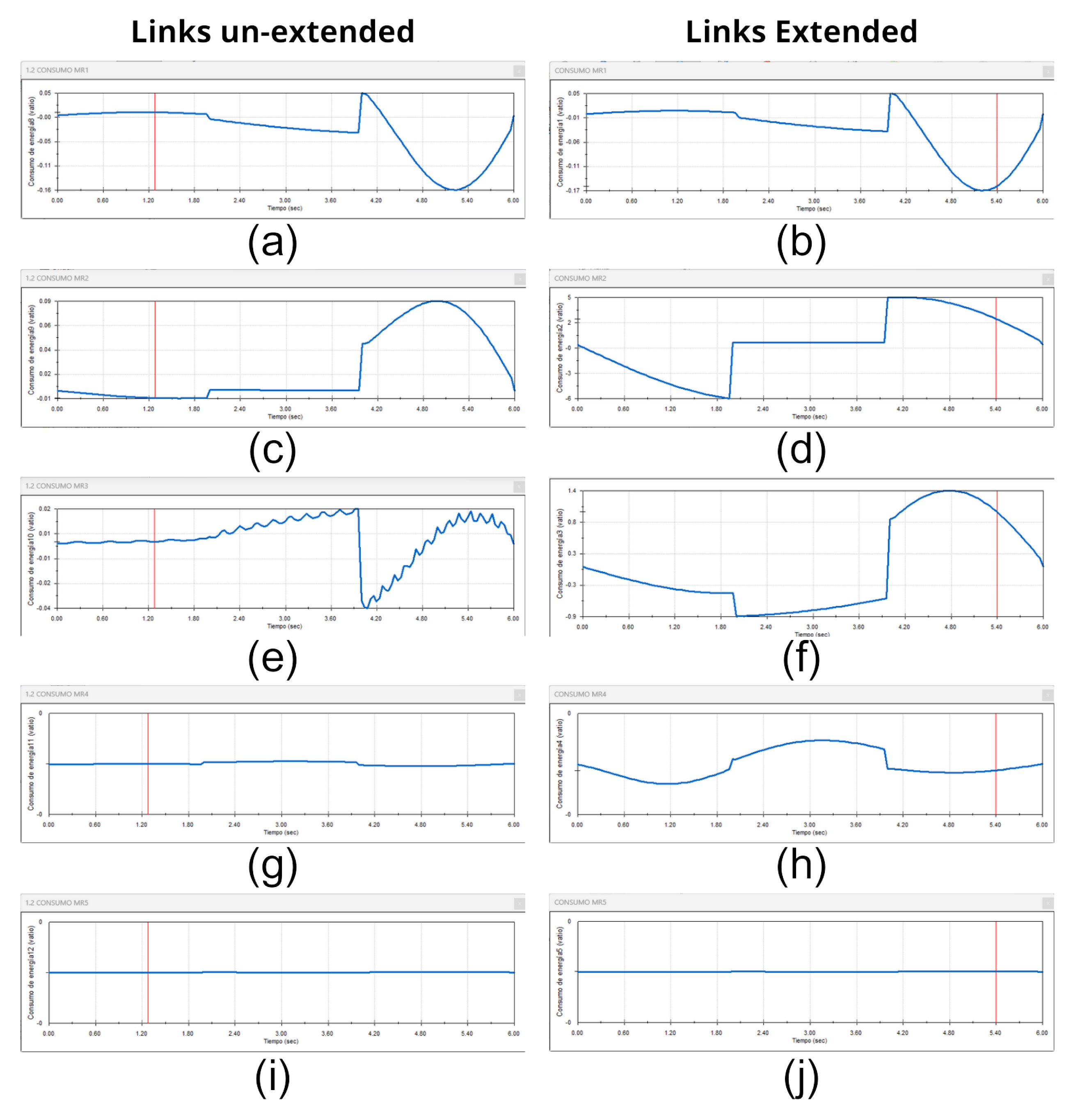

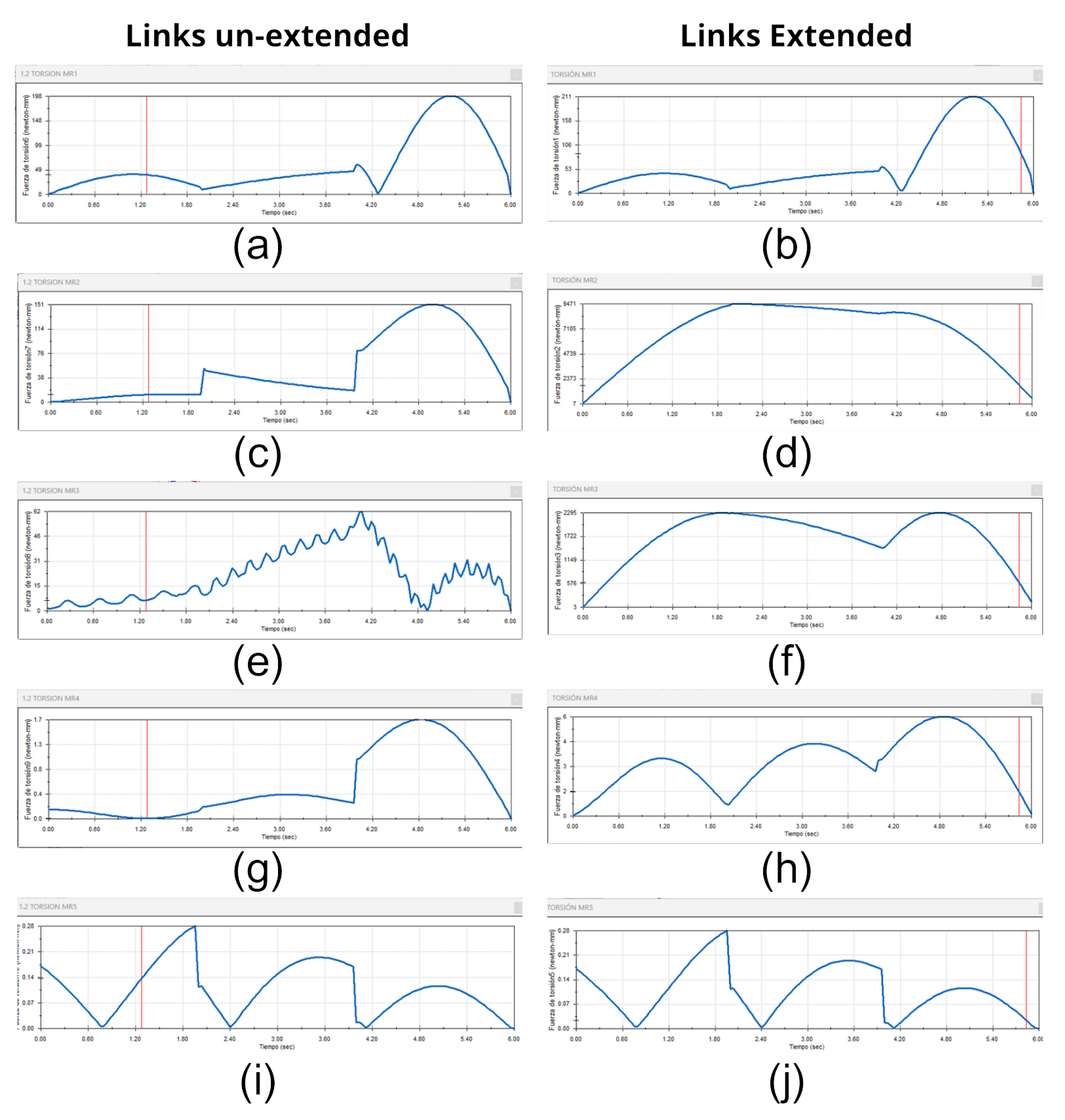

4.3. Motion Analysis

4.4. Systems Integration

5. Related Works

6. Conclusion

Abbreviations

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modeling |

| CAD | Computer Aided design |

| ABS | Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene |

| FOS | Factor of Safety |

| TPO | Pulse Train Output |

| IOT | Internet Of Things |

| AI | Artifitial Inteligence |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| TL | Transfer Learning |

| mAP | Average Precision |

| PAN | Path Aggregation Network |

| NAS | Neural Architecture Search |

| BiFPN | Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network |

| ASFF | Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion |

| SFAM | Selective Feature Aggregation Module |

References

- Sensors | Free Full-Text | Perceptual Soft End-Effectors for Future Unmanned Agriculture.

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Ju, C.; Son, H.I. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Agriculture: A Review of Perspective of Platform, Control, and Applications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 105100–105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Shu, G.; Chen, Q. Kinematic solution and singularity analysis for 7-DOF redundant manipulators with offsets at the elbow 2018. pp. 422–427. [CrossRef]

- Terreran, M.; Barcellona, L.; Ghidoni, S. A general skeleton-based action and gesture recognition framework for human–robot collaboration. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2023, 170, 104523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveriano, M.; Abu-Dakka, F.J.; Kyrki, V. Learning stable robotic skills on Riemannian manifolds. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2023, 169, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robotics | Free Full-Text | Neural Network Mapping of Industrial Robots’ Task Times for Real-Time Process Optimization.

- Riboli, M.; Jaccard, M.; Silvestri, M.; Aimi, A.; Malara, C. Collision-free and smooth motion planning of dual-arm Cartesian robot based on B-spline representation. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2023, 170, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, L. Analytical Inverse Kinematics and Self-Motion Application for 7-DOF Redundant Manipulator. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 18662–18674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yan, Z. An Adaptive Fuzzy Recurrent Neural Network for Solving the Nonrepetitive Motion Problem of Redundant Robot Manipulators. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2020, 28, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miteva, L.; Yovchev, K.; Chavdarov, I. Planning Orientation Change of the End-effector of State Space Constrained Redundant Robotic Manipulators 2022. pp. 51–56. [CrossRef]

- Ando, N.; Takahashi, K.; Mikami, S. Disposable Soft Robotic Gripper Fablicated from Ribbon Paper with a Few Steps of Origami Folding 2022. pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Samadikhoshkho, Z.; Zareinia, K.; Janabi-Sharifi, F. A Brief Review on Robotic Grippers Classifications 2019. pp. 1–4. ISSN: 2576-7046. [CrossRef]

- Woliński; Wojtyra, M. An inverse kinematics solution with trajectory scaling for redundant manipulators. Mechanism and Machine Theory 2024, 191, 105493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finite-Time Convergence Adaptive Fuzzy Control for Dual-Arm Robot With Unknown Kinematics and Dynamics \textbar IEEE Journals & Magazine \textbar IEEE Xplore.

- Zribi, S.; Knani, J.; Puig, V. Improvement of Redundant Manipulator Mechanism performances using Linear Parameter Varying Model Approach 2020. pp. 1–6. ISSN: 2378-3451. [CrossRef]

- Balaji, A.; Ullah, S.; Das, A.; Kumar, A. Design Methodology for Embedded Approximate Artificial Neural Networks 2019. pp. 489–494. [CrossRef]

- Mangal, R.; Nori, A.V.; Orso, A. Robustness of neural networks: a probabilistic and practical approach 2019. pp. 93–96. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, P.; Meng, F.; Zhou, H.; Zhong, H.; Zhou, J.; Mou, L.; Song, S. Simulated annealing for optimization of graphs and sequences. Neurocomputing 2021, 465, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, T.; Nishimoto, S. Artificial neural network modelling of the neural population code underlying mathematical operations. NeuroImage 2023, 270, 119980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, M.N.; Beck, F.; Schwegel, M.; Hartl-Nesic, C.; Nguyen, A.; Kugi, A. Machine learning-based framework for optimally solving the analytical inverse kinematics for redundant manipulators. Mechatronics 2023, 91, 102970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaptive Projection Neural Network for Kinematic Control of Redundant Manipulators With Unknown Physical Parameters.

- Machines \textbar Free Full-Text \textbar A Collision Avoidance Strategy for Redundant Manipulators in Dynamically Variable Environments: On-Line Perturbations of Off-Line Generated Trajectories.

- Alatise, M.B.; Hancke, G.P. A Review on Challenges of Autonomous Mobile Robot and Sensor Fusion Methods. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 39830–39846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.C.; Bhattacharya, M. Adoption of autonomous robots in the soft fruit sector: Grower perspectives in the UK. Smart Agricultural Technology 2023, 3, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, C.; Huang, S. Design of a Framework for Implementation of Industrial Robot Manipulation Using PLC and ROS 2 2022. pp. 41–45. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B. Study of PLC-based industrial robot control systems. 2022, 1094–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Qin, X.; Li, G. An effective self-collision detection algorithm for multi-degree-of-freedom manipulator. Measurement Science and Technology 2022, 34, 015901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganin, P.; Kobrin, A. Modeling of the Industrial Manipulator Based on PLC Siemens and Step Motors Festo 2020. pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Ma, X.; Yu, C.; Xu, P. Framework of Industrial Robot System Programming and Management Software 2019. pp. 1256–1261. ISSN: 2158-2297. [CrossRef]

- Rehbein, J.; Wrütz, T.; Biesenbach, R. Model-based industrial robot programming with MATLAB/Simulink 2019. pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Kinematics Analysis for a Heavy-load Redundant Manipulator Arm Based on Gradient Projection Method.

- Chouhan, S.S.; Kaul, A.; Singh, U.P.; Jain, S. Bacterial Foraging Optimization Based Radial Basis Function Neural Network (BRBFNN) for Identification and Classification of Plant Leaf Diseases: An Automatic Approach Towards Plant Pathology. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 8852–8863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moupojou, E.; Tagne, A.; Retraint, F.; Tadonkemwa, A.; Wilfried, D.; Tapamo, H.; Nkenlifack, M. FieldPlant: A Dataset of Field Plant Images for Plant Disease Detection and Classification With Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 35398–35410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.N.; Tran, L.V.; Dao, S.V.T. Early Disease Classification of Mango Leaves Using Feed-Forward Neural Network and Hybrid Metaheuristic Feature Selection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 189960–189973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Chen, Y.; Liu, B.; He, D.; Liang, C. Real-Time Detection of Apple Leaf Diseases Using Deep Learning Approach Based on Improved Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 59069–59080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liao, Y.; Lin, F.; Huang, B. An Improved Lightweight YOLOv5 Algorithm for Detecting Strawberry Diseases. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 54080–54092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection 2020. arXiv 2020, arXiv:arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar]

- Asha Rani, K.P.; Gowrishankar, S. Pathogen-Based Classification of Plant Diseases: A Deep Transfer Learning Approach for Intelligent Support Systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 64476–64493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; P, P.; Dutta, A.; Behera, L. Visual motor control of a 7DOF redundant manipulator using redundancy preserving learning network. Robotica Cambridge University Press. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).