Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

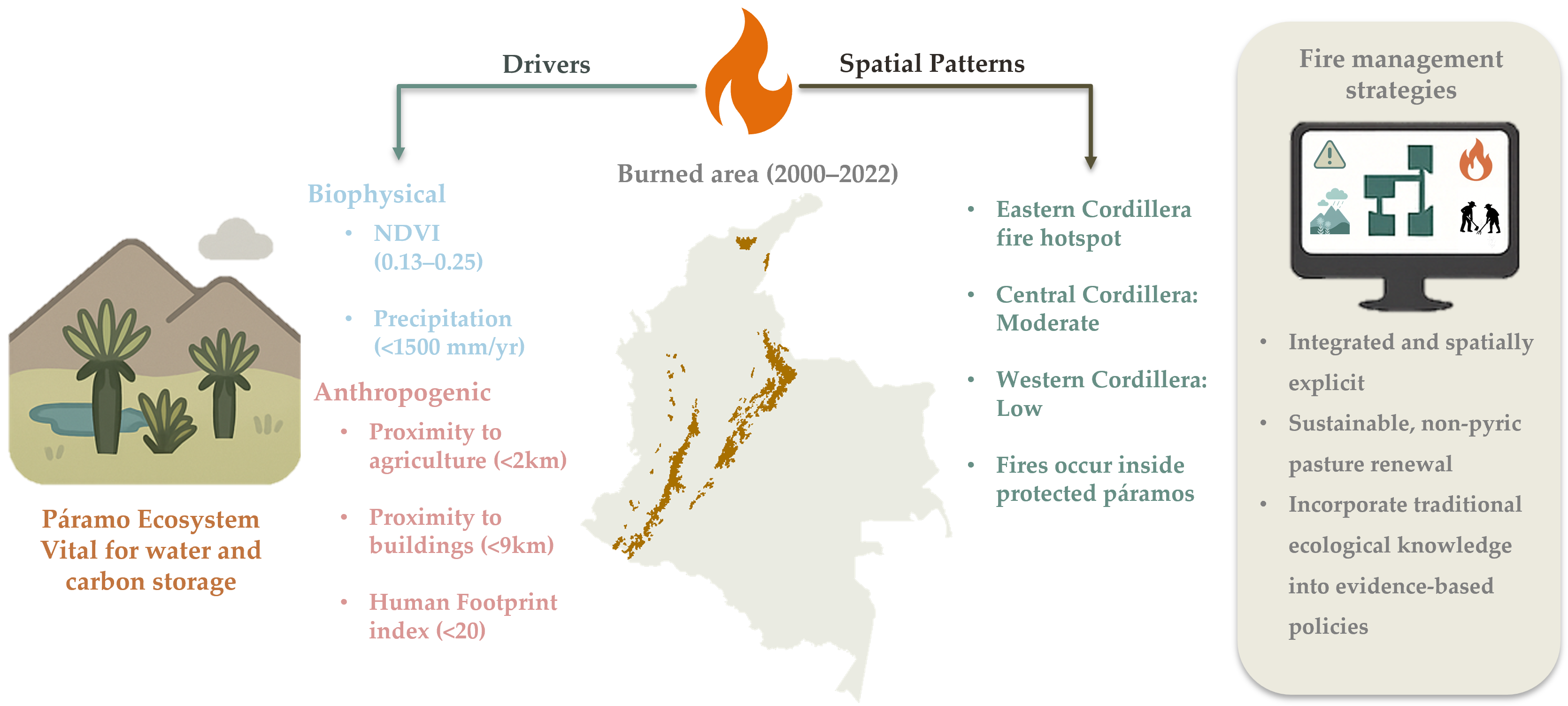

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sets

2.2.1. Burned Area Data for the Páramos Unit

2.2.2. Explanatory Variables

2.2.3. Spatial Analysis

3. Results

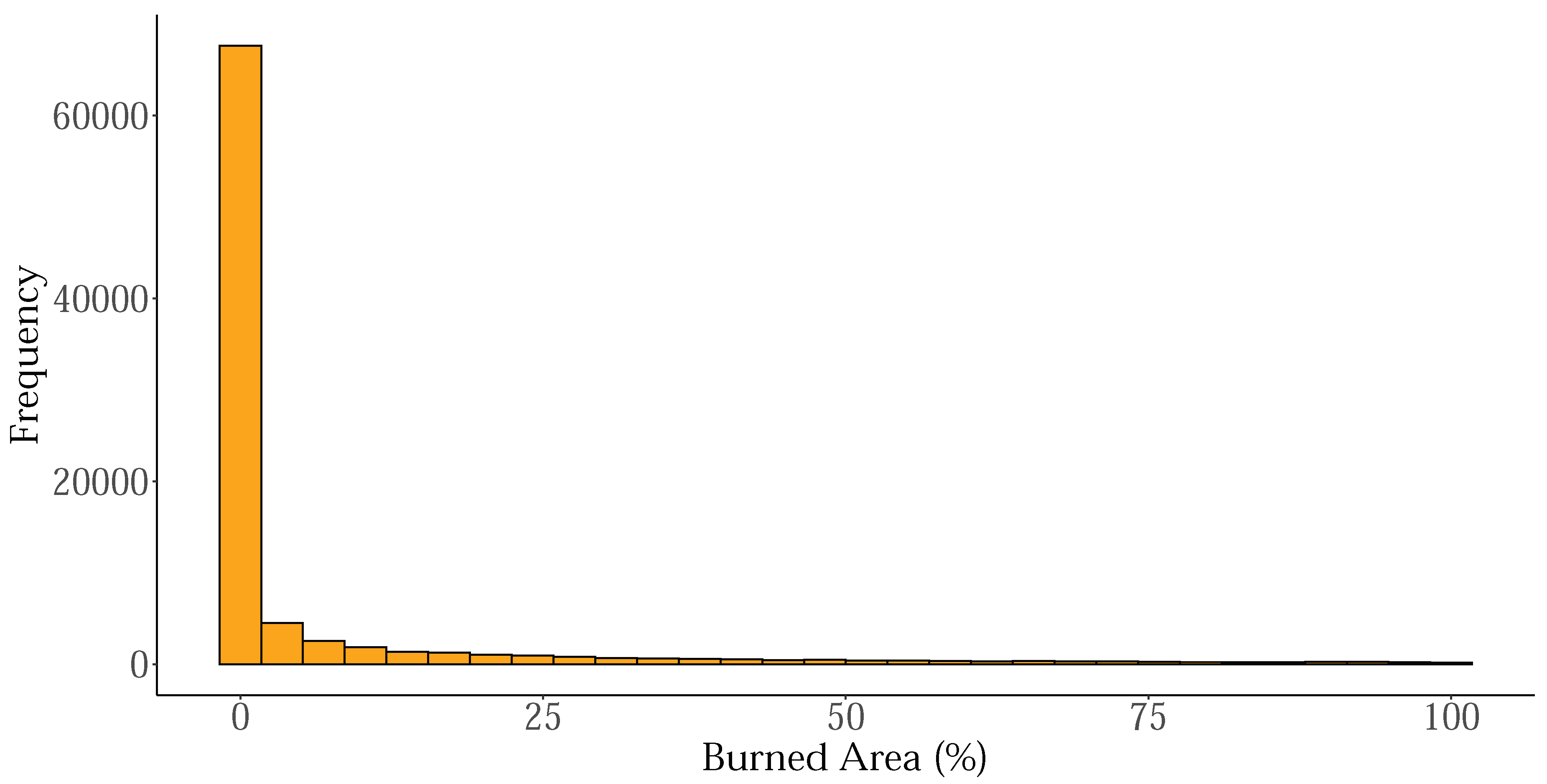

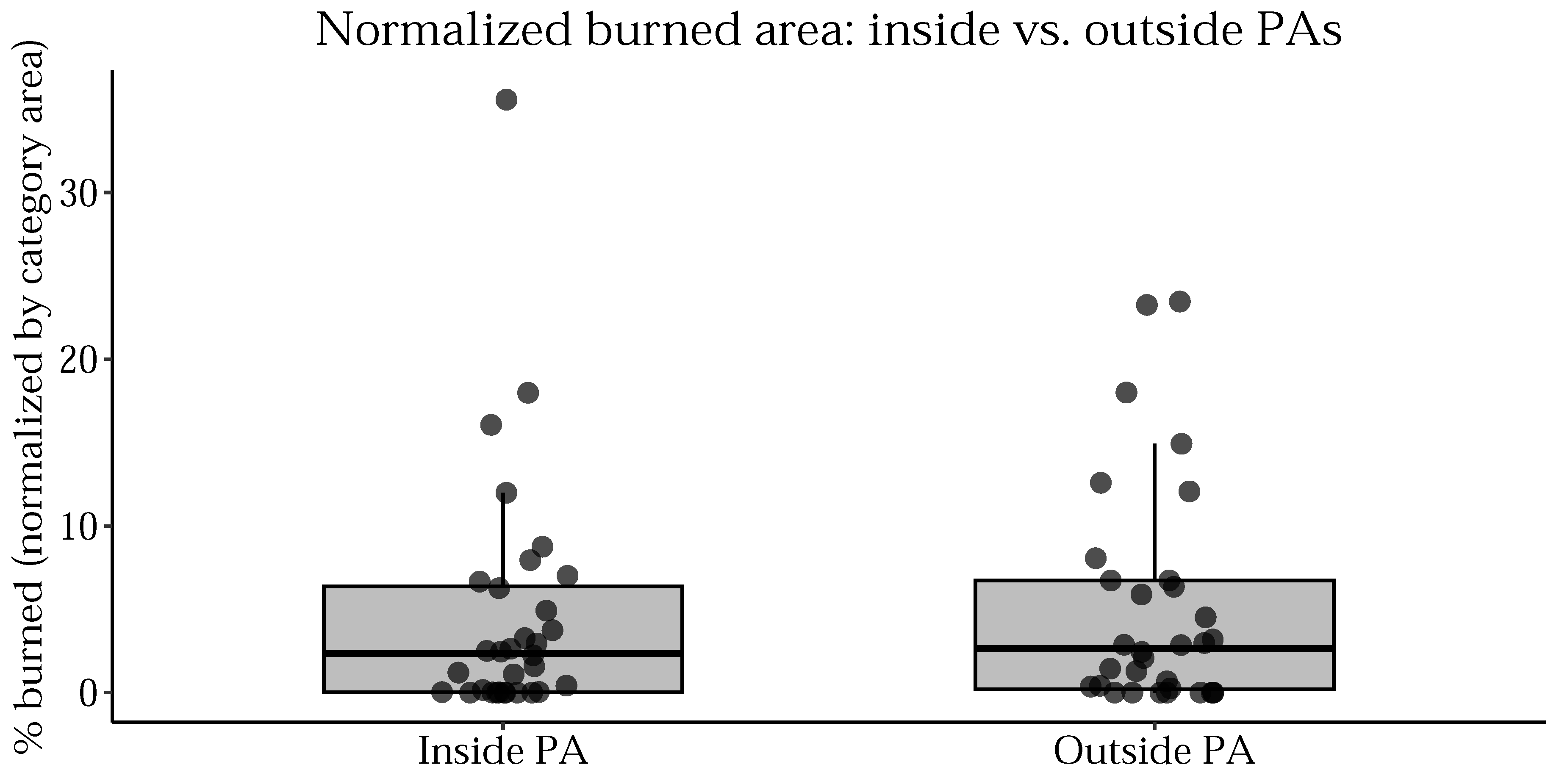

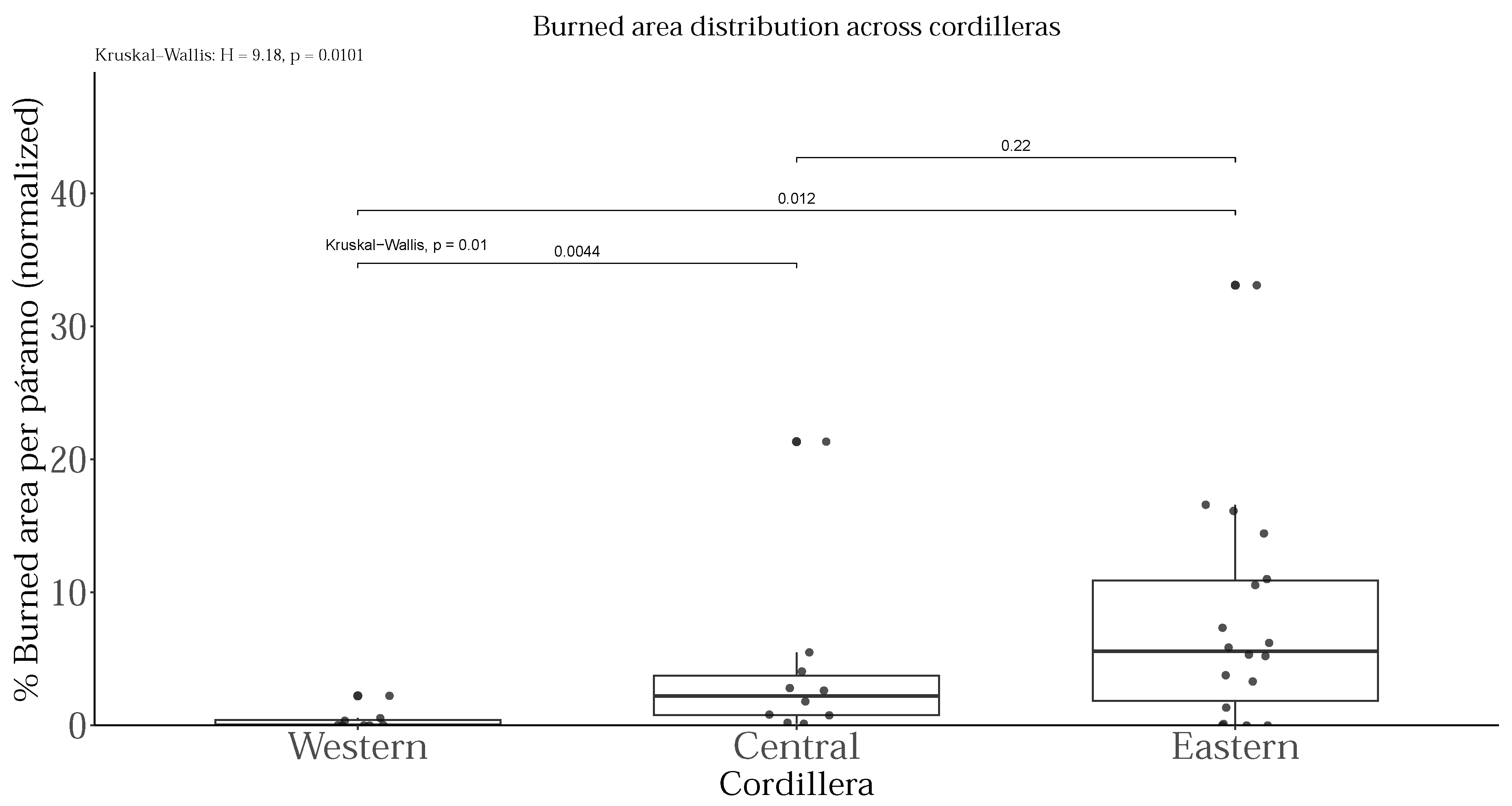

3.1. Burned Area

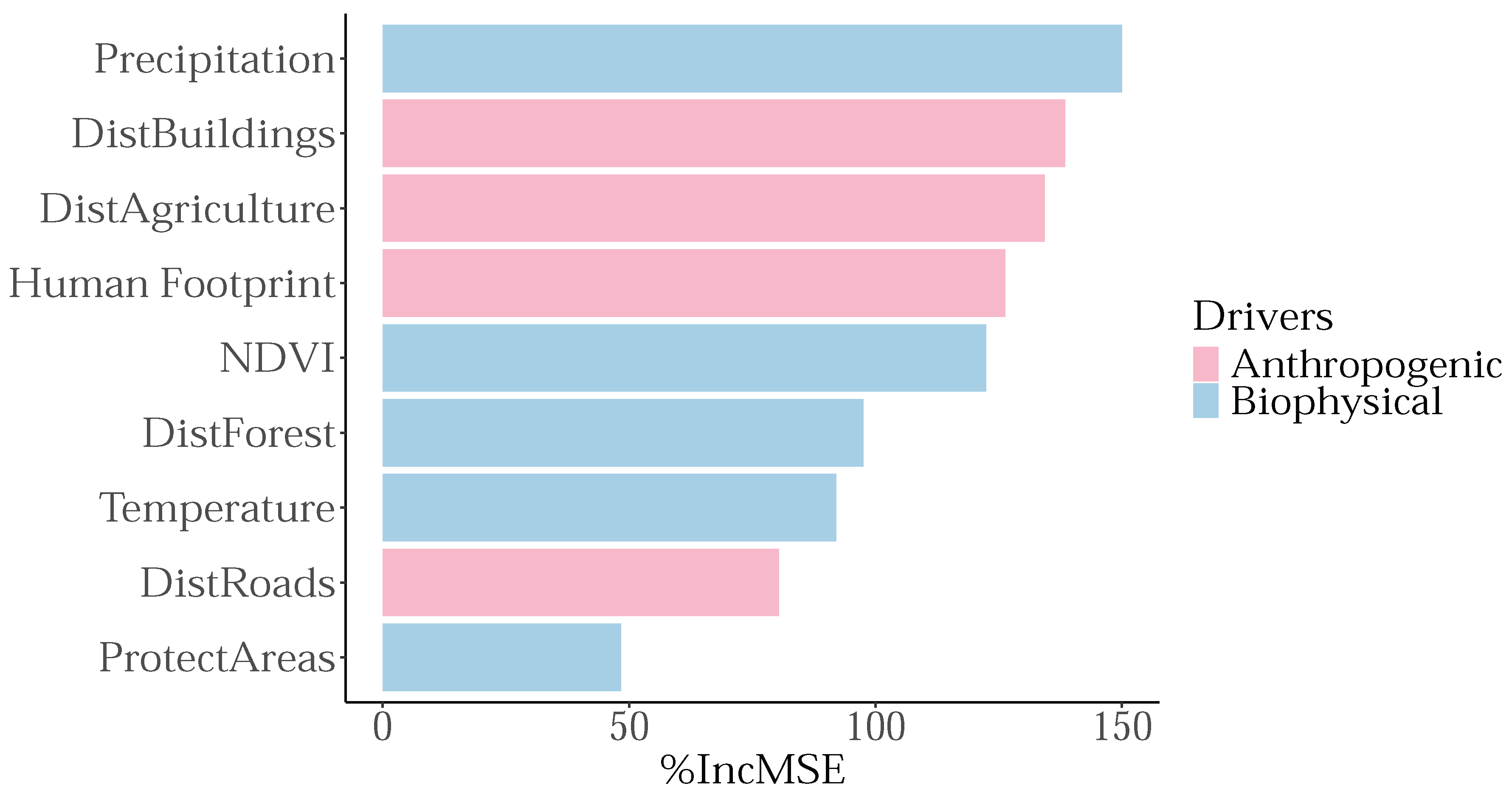

3.2. Drivers of burned area across the páramo ecosystem

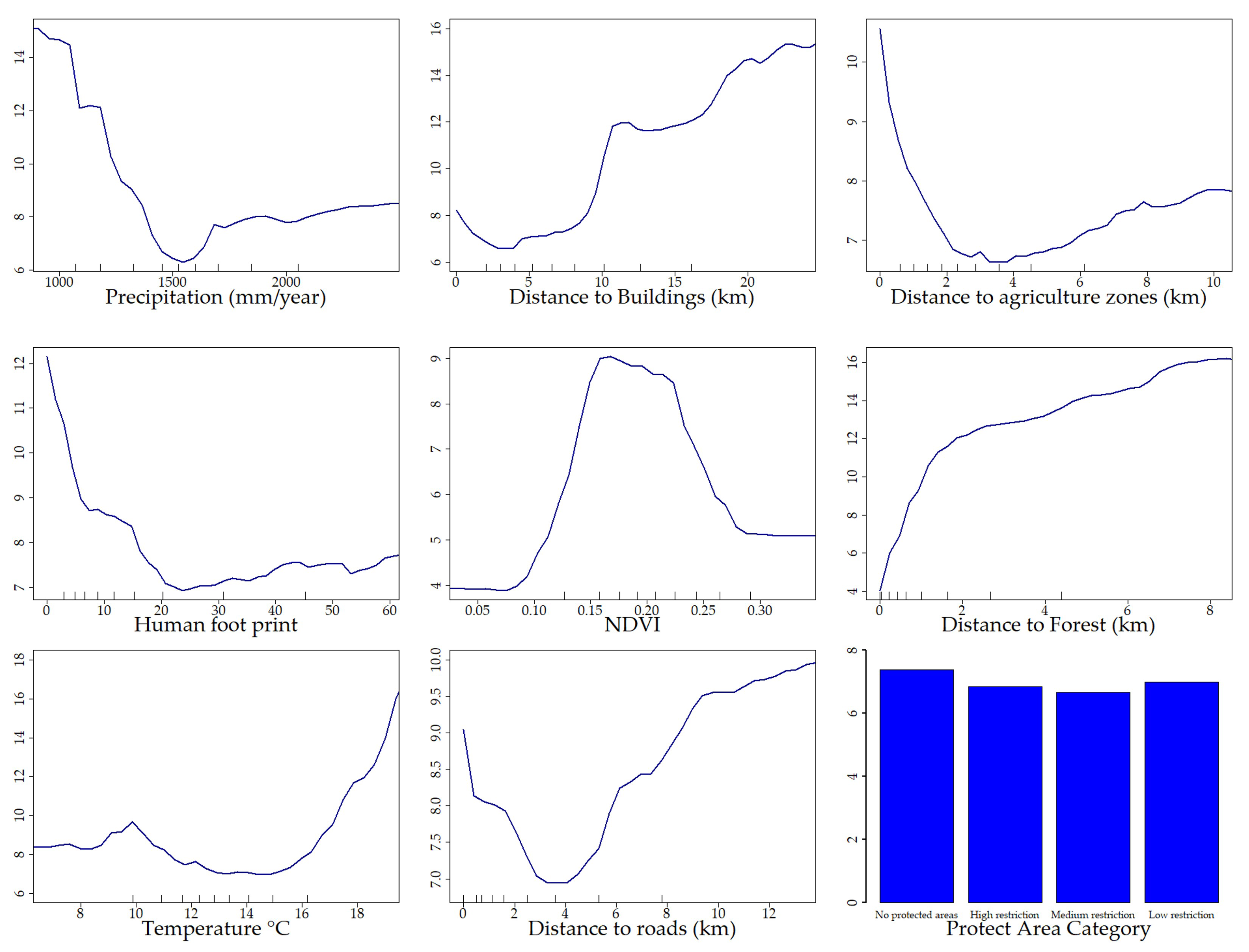

3.2.1. Biophysical Variables

3.2.2. Human Pressure

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| SINA | Sistema Nacional Ambiental |

| SINAP | Sistema Nacional de Areas Protegidas |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Páramo | % burned | % protected area | Cordillera |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belmira | 2.23 | 100.00 | Western |

| Cerro Plateado | 0.55 | 18.22 | |

| Frontino - Urrao | 0.35 | 84.49 | |

| Paramillo | 0.04 | 99.88 | |

| Farallones de Cali | 0.02 | 100.00 | |

| Tatamá | 0.01 | 100.00 | |

| Citará | 0.00 | 56.11 | |

| El Duende | 0.00 | 39.77 | |

| Chiles - Cumbal | 21.34 | 16.99 | Central |

| Los Nevados | 5.49 | 56.03 | |

| Nevado del Huila - Moras | 4.06 | 78.22 | |

| Guanacas - Puracé - Coconucos | 2.81 | 24.96 | |

| Las Hermosas | 2.62 | 65.08 | |

| Chilí - Barragán | 1.80 | 35.73 | |

| La Cocha - Patascoy | 0.82 | 34.98 | |

| Sotará | 0.76 | 42.05 | |

| Sonsón | 0.20 | 43.39 | |

| Doña Juana - Chimayoy | 0.13 | 50.85 | |

| Perijá | 33.11 | 79.67 | Eastern |

| Tota - Bijagual - Mamapacha | 16.59 | 54.60 | |

| Altiplano Cundiboyacense | 16.13 | 11.89 | |

| Cruz Verde - Sumapaz | 14.44 | 53.23 | |

| Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta | 11.00 | 100.00 | |

| Pisba | 10.56 | 29.86 | |

| Guantiva - La Rusia | 7.34 | 50.82 | |

| Iguaque - Merchán | 6.21 | 54.27 | |

| Almorzadero | 5.86 | 0.64 | |

| Sierra Nevada del Cocuy | 5.33 | 71.27 | |

| Rabanal y río Bogotá | 5.22 | 68.56 | |

| Guerrero | 3.78 | 85.34 | |

| Jurisdicciones - Santurbán - Berlín | 3.31 | 43.00 | |

| Chingaza | 1.34 | 81.53 | |

| Tamá | 0.12 | 75.03 | |

| Los Picachos | 0.00 | 88.20 | |

| Miraflores | 0.00 | 84.57 | |

| Yariguíes | 0.00 | 99.36 |

| Cordillera | Total area (ha) | Burned cells | % burned |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central | 1,013,731 | 35,121 | 3.46 |

| Eastern | 1,490,635 | 133,452 | 8.95 |

| Western | 77,968 | 362 | 0.46 |

| Variable | Thresholds |

|---|---|

| DistForest | 1.72 |

| Temperature | 17.08 |

| Precipitation | 1577.41 |

| DistBuildings | 9.60 |

| DistRoads | 5.60 |

| DistAgriculture | 2.14 |

| NDVI | 0.14 |

| ProtectAreas | – |

| Human Footprint | 20.50 |

References

- Ramsay, P.M.; Oxley, E.R. Fire temperatures and postfire plant community dynamics in Ecuadorian grass páramo. Vegetatio 1996, 124, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, R.G.; Llambí, L.D. Plant Diversity in Páramo—Neotropical High Mountain Humid Grasslands. In Encyclopedia of the World’s Biomes; Elsevier, 2020; Vol. 1-5, pp. 362–372. [CrossRef]

- Madriñán, S.; Cortés, A.J.; Richardson, J.E. Páramo is the world’s fastest evolving and coolest biodiversity hotspot. Frontiers in genetics 2013, 4, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, W.J.; Woodward, F.I.; Midgley, G.F. The global distribution of ecosystems in a world without fire. New Phytologist 2005, 165, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuncho, C.; Chuncho, G. Páramos del Ecuador, importancia y afectaciones: Una revisión. Technical report, 2019.

- Sarmiento, P.C.E.; Cadena, V.C.E.; Sarmiento, G.M.V.; Zapata, J.J.A. Aportes a la conservación estratégica de los páramos de Colombia : actualización de la cartografía de los complejos de páramo a escala 1:100.000; 2013; p. 87.

- Borrelli, P.; Armenteras, D.; Panagos, P.; Modugno, S.; Schütt, B. The implications of fire management in the andean paramo: A preliminary assessment using satellite remote sensing. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 11061–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Stradic, S.; Alvarado, S.T.; Ríos, O.V.; Silveira, F.A.O.; Le Stradic, S.; Alvarado, S.T.; Ríos, O.V.; Silveira, F.A.O. Fire Ecology on Megadiverse Montane Grasslands 2025. pp. 187–211. [CrossRef]

- Keating, P.L. Fire ecology and conservation in the high tropical Andes: Observations from northern Ecuador. Journal of Latin American Geography 2007, 6, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.E.; Young, K.R.; Josse, C. Vulnerability of Tropical Andean Ecosystems to Climate Change. Technical report, 2011.

- White, S. Grass páramo as hunter-gatherer landscape. The Holocene 2013, 23, 898–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, M.B.; Rozas-Davila, A.; Raczka, M.; Nascimento, M.; Valencia, B.; Sales, R.K.; McMichael, C.N.; Gosling, W.D. A palaeoecological perspective on the transformation of the tropical Andes by early human activity, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Obando-Cabrera, L.; Díaz-Timoté, J.J.; Bastarrika, A.; Celis, N.; Hantson, S. The Paramo Fire Atlas: quantifying burned area and trends across the Tropical Andes. Environmental Research Letters 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, I.G.; Franco-Gaviria, F.; Castañeda, I.; Robinson, C.; Room, A.; Berrío, J.C.; Armenteras, D.; Urrego, D.H. Holocene Fires and Ecological Novelty in the High Colombian Cordillera Oriental. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2022, 10, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, D.L.; Balslev, H.; Sklenář, P. Human impact on tropical-alpine plant diversity in the northern Andes. Biodiversity and Conservation 2015, 24, 2673–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.P.; Kappelle, M. Fire in the páramo ecosystems of Central and South America. In Tropical Fire Ecology; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009; pp. 505–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- League, B.L.; Horn1, S.P. A 10 000 year record of Páramo fires in Costa Rica. Journal of Tropical Ecology 2000, 16, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Paladines, V.; Correa-Quezada, L.; Valdiviezo Malo, H.; Zurita Ruáles, J.; Pereddo Tumbaco, A.; Zambrano Pisco, M.; Lucio Panchi, N.; Jiménez Álvarez, L.; Benítez; Loján-Córdova, J. Exploring the ethnobiological practices of fire in three natural regions of Ecuador, through the integration of traditional knowledge and scientific approaches. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2024, 20, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Salazar, P.; Ramsay, P.M. Physiognomic responses of páramo tussock grass to time since fire in northern Ecuador. Revista Peruana de Biología 2020, 27, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomer, M.A.; Ramsay, P.M. Post-fire changes in plant growth form composition and diversity in Andean páramo grassland. Applied Vegetation Science 2021, 24, e12554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Veraverbeke, S.; Andela, N.; Lasslop, G.; Forkel, M.; Smith, A.J.; Burton, C.; Betts, R.A.; van der Werf, G.R.; et al. Global and Regional Trends and Drivers of Fire Under Climate Change. Reviews of Geophysics 2022, 60, e2020RG000726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, O.; Keeping, T.; Gomez-Dans, J.; Prentice, I.C.; Harrison, S.P. The global drivers of wildfire. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2024, 12, 1438262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, C.; Bar-Massada, A.; Chuvieco, E. A European-scale analysis reveals the complex roles of anthropogenic and climatic factors in driving the initiation of large wildfires. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 917, 170443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calviño-Cancela, M.; Chas-Amil, M.L.; García-Martínez, E.D.; Touza, J. Interacting effects of topography, vegetation, human activities and wildland-urban interfaces on wildfire ignition risk. Forest Ecology and Management 2017, 397, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Cuesta, R.M.; Carmona-Moreno, C.; Lizcano, G.; New, M.; Silman, M.; Knoke, T.; Malhi, Y.; Oliveras, I.; Asbjornsen, H.; Vuille, M. Synchronous fire activity in the tropical high Andes: an indication of regional climate forcing. Global Change Biology 2014, 20, 1929–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Ríos, X.; Lopez-Fabara, C.; Navarrete, A.; Torres-Paguay, S.; Flores, M. Spatiotemporal patterns of burned areas, fire drivers, and fire probability across the equatorial Andes. Journal of Mountain Science 2021, 18, 952–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.C.; Quezada, L.C.; Álvarez, L.J.; Loján-Córdova, J.; Carrión-Paladines, V. Indigenous use of fire in the paramo ecosystem of southern Ecuador: a case study using remote sensing methods and ancestral knowledge of the Kichwa Saraguro people. Fire Ecology 2023, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zomer, M.A. Fire Ecology of Northern Andean grasslands: Estimating recent fire history and its impact on páramo plants 2016.

- Oliveras, I.; Anderson, L.O.; Malhi, Y. Application of remote sensing to understanding fire regimes and biomass burning emissions of the tropical Andes. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2014, 28, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomer, M.A.; Ramsay, P.M. The impact of fire intensity on plant growth forms in high-altitude Andean grassland. bioRxiv, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Ríos, O. Bases ecológicas y sociales para la restauración de los páramos. Technical report, 2021.

- Zomer, M.A.; Ramsay, P.M. Espeletia giant rosette plants are reliable biological indicators of time since fire in andean grasslands. Plant Ecology 2018, 219, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luteyn, J.L. Páramos: A checklist of Plant Diversity, Geographical Distribution and Botanical Literature. Technical report, 1999.

- Balslev, H.; Luteyn, J.L. Paramo: an Andean ecosystem under human influence. Paramo: an Andean ecosystem under human influence. 1992.

- Curatola Fernández, G.F.; Obermeier, W.A.; Gerique, A.; López Sandoval, M.F.; Lehnert, L.W.; Thies, B.; Bendix, J. Land cover change in the Andes of southern Ecuador-Patterns and drivers. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 2509–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.M.; Dinerstein, E.; Wikramanayake, E.D.; Burgess, N.D.; Powell, G.V.; Underwood, E.C.; D’Amico, J.A.; Itoua, I.; Strand, H.E.; Morrison, J.C.; et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: A new map of life on Earth, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Peyre, G.; Osorio, D.; François, R.; Anthelme, F. Mapping the páramo land-cover in the Northern Andes. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2021, 42, 7777–7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano-Girón, J.; Molina Berbeo, M.A.; Gutiérrez Montoya, C.; Ochoa-Quintero, J.M. Estado de conservación de los páramos en colombia. Biodiversidad 2020. Estado y tendencias de la biodiversidad continental de Colombia 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia (PNN). Mapa de áreas protegidas de Colombia (RUNAP). Shapefile y metadatos, 2023.

- Instituto de Hidrología Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales (IDEAM).; Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible (MADS). Actualización de cifras de monitoreo de la superficie de bosque – Año 2024. Resumen de resultados de monitoreo. Technical report, República de Colombia, 2025.

- Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (IGAC). Cartograf\’\ia vectorial a escala 1:100,000 con cobertura total de la República de Colombia, 2022.

- Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica (CNMH). Geoportal de Datos Abiertos: Casos Acciones bélicas, 2022.

- Instituto de Hidrología Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales (IDEAM). Cobertura de la Tierra. Metodolog\’\ia CORINE Land Cover Adaptada para Colombia. Per\’\iodo 2018. República de Colombia. Escala 1:100,000, 2021.

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Parks, S.A.; Hegewisch, K.C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Scientific Data 2018, 5, 170191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (IGAC). Modelo Digital de Elevación. Colombia. SRTM 30 metros, 2011.

- Correa Ayram, C.; Etter, A.; Díaz-Timoté, J.; Buriticá, S.; Ramírez, W.; Corzo, G. Spatiotemporal evaluation of the human footprint in Colombia: Four decades of anthropic impact in highly biodiverse ecosystems, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.; McCarthy, G.; Mellor, A.; Newell, G.; Smith, L. Training data requirements for fire severity mapping using Landsat imagery and random forest. Remote Sensing of Environment 2020, 245, 111839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Feng, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, F. Identifying Forest Fire Driving Factors and Related Impacts in China Using Random Forest Algorithm. Forests 2020, Vol. 11, Page 507 2020, 11, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Oehler, F.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Camia, A.; Pereira, J.M. Modeling spatial patterns of fire occurrence in Mediterranean Europe using Multiple Regression and Random Forest. Forest Ecology and Management 2012, 275, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine on JSTOR.

- Hijmans, R. terra: Spatial Data Analysis. R package version 1.8-73, 2025.

- Taiyun, W.; Viliam, S. R package ’corrplot’: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix (Version 0. 95) 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Wang, X. Spatial-Temporal NDVI Variation of Different Alpine Grassland Classes and Groups in Northern Tibet from 2000 to 2013. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-14-00110.1 2015, 35, 254–263. [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Cocero, D.; Riaño, D.; Martin, P.; Martínez-Vega, J.; de la Riva, J.; Pérez, F. Combining NDVI and surface temperature for the estimation of live fuel moisture content in forest fire danger rating. Remote Sensing of Environment 2004, 92, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podwojewski, P.; Poulenard, J. La degradación de los suelos de los páramos Risque hydrométéorologique à Quito View project PALAS : PAleoclimate from LAke Sediments on Kerguelen Archipelago View project. Technical report, 2000.

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Colombia: Country dossier 2021 – National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan / Protected Areas Management Effectiveness. Technical report, Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), 2021.

| Spatial variable (Abbrev.) | Description | Reference | Data source (URL) | Resolution/Scale | Time series |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance to Forest (DistForest, DF) | Euclidean distance from forest in km calculated for the forest to the nearest source. | IDEAM (2024)[40] | https://www.ideam.gov.co/transparencia/datos-abiertos/seccion-de-datos-abiertos/resultados-monitoreo-de-bosques | 30 m | 2024 |

| Distance to buildings (DistBuildings, DB) | Euclidean distance from buildings in km calculated for the buildings to the nearest source. | IGAC (2022)[41] | https://www.colombiaenmapas.gov.co/?e=-82.43784778320864,-0.17644239911865092,-71.23179309571162,9.90326984502256,4686&b=igac&u=0&t=23&servicio=205 | 1:100,000 | 2016–2022 |

| Distance to roads (DistRoads, DR) | Euclidean distance from roads in km calculated for the roads to the nearest source. | IGAC (2022)[41] | https://www.colombiaenmapas.gov.co/?e=-82.43784778320864,-0.17644239911865092,-71.23179309571162,9.90326984502256,4686&b=igac&u=0&t=23&servicio=205 | 1:100,000 | 2014–2016 |

| Log conflict density (ConflictDens_log, CDl) | Based on kernel density from conflict-related places; transformation was applied due to strong concentration near zero. | CNMH (2022)[42] | https://geoportal-de-datos-abiertos-cnmh-cnmh.hub.arcgis.com/datasets/285a0cfe6aa34f65ab49c95aee298d0e_1/about | 30 m | 1980–2024 |

| Distance to agricultural areas (DistAgriculture, DA) | Euclidean distance from agricultural areas in km to the nearest source. | IDEAM (2021)[43] | https://www.colombiaenmapas.gov.co/?e=-90.24363391601412,-5.572398896778716,-55.74656360352328,13.859268426770145,4686&b=igac&l=881&u=0&t=4302&servicio=881 | 1:100,000 | 2018 |

| Precipitation (P) | Multi-annual accumulated precipitation from TerraClimate. | TerraClimate (2024)[44] | https://www.climatologylab.org/terraclimate.html | 4,000 m | 2000–2022 |

| Max Temperature (°C) (T) | Multi-year mean of maximum temperature from TerraClimate. | TerraClimate (2024)[44] | https://www.climatologylab.org/terraclimate.html | 4,000 m | 2000–2022 |

| Elevation (E) | Altitude above sea level. | IGAC (2011)[45] | https://www.colombiaenmapas.gov.co/?e=-82.66306750976614,-1.8784752954619761,-65.83201282227061,11.877955613394604,4686&b=igac&u=0&t=23&servicio=159 | 30 m | 2011 |

| NDVI (NDVI) | Median normalized difference vegetation index computed from Landsat 5, 7, 8, and 9. | Processing was performed in Google Earth Engine using code developed by the authors of this study | https://code.earthengine.google.com/b14e1f08d76eb28c45e35148517f485d | 30 m | 2000–2024 |

| Human footprint (HFP) | Degree of impact of human activities (0=no impact, 100=maximum impact). | Correa et al. (2020)[46] | https://geonetwork.humboldt.org.co/geonetwork/srv/spa/catalog.search#/metadata/e29b399c-24ee-4c16-b19c-be2eb1ce0aae | 300 m | 1990–2015 |

| Protected Areas (PA) | Boundary of protected areas in Colombia. | RUNAP (2025)[39] | https://storage.googleapis.com/pnn_geodatabase/runap/latest.zip | 1:100,000 | 2025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).