1. Introduction

Until 1978, classical thermodynamics had been developed through the contributions of Sadi Carnot (1796-1832), Rudolf Clausius (1822-1888), William Thomson (Lord Kelvin, 1824-1907), Max Planck (1858-1947), and James Joule (1818-1889) regarding the first and second laws of thermodynamics [

1].

Based on experimental observations, the first law of classical thermodynamics states that energy cannot be created or destroyed during a process; it can only change forms [

1,

2,

3,

4].

A conventional thermodynamic analysis of an energy conversion system involves the application of the first law of thermodynamics, also known as energy analysis [

2]. This analysis shows how internal energy, heat, and work done are related during the processes occurring within the system. Since energy is a conserved property and no process has ever been observed to violate the first law, it is reasonable to conclude that any process occurring in nature must comply with the first law for it to take place. However, satisfying the first law does not guarantee that the process can occur. This is because processes advance in a specific direction and not in the reverse direction. The first law imposes no restrictions on the direction in which a process occurs [

1]. This insufficiency of the first law to determine whether a process can occur is resolved by introducing another general principle: the second law of thermodynamics. In the literature, there are several standard forms of the second law, which are believed to be equivalent and are attributed to Clausius, Kelvin, and Planck [

5,

6,

7].

The second law of thermodynamics allows for the identification of the direction in which natural processes occur, defines the degree of perfection of thermodynamic processes, and can be used to quantify this level of perfection, effectively pointing the way to optimize efficiency losses. It introduces the new state function called entropy and asserts that energy possesses quality as well as quantity [

2]. Therefore, a process cannot occur unless it satisfies both the first and second laws of thermodynamics.

However, starting in 1979, Serrin’s research in thermodynamics provided new insights into the meaning of temperature and the definition of the absolute temperature scale, the definition of a thermodynamic system and a system formed by the product of two thermodynamic systems, new formulations of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, the introduction of the concept of the accumulation function, and how it operates in thermal processes for cycles. It was also demonstrated; that the first law for a cycle implies an inequality for the work done within it, which involves Clausius’ integral [

8].

Serrin’s work in thermodynamics offers a perspective different from what is typically found in the literature and in classical thermodynamics courses for science and engineering.

In

Section 2, an alternative mathematical development is presented to calculate the inequality for the work done in a cycle, considering the temperature bounds in the processes experienced by a thermal cycle, following the approaches of Serrin and Huilgol [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In

Section 3, the derivation of the accumulation function for the ideal air-standard Brayton cycle is presented, where the temperature constraints

and

of the adiabatic compression and expansion processes under which it operates are analyzed. Subsequently, a practical example of the accumulation function for this cycle is provided, along with its graphical representation. Finally, in

Section 4, the conclusions are presented, along with a brief discussion of potential applications.

2. Work Done in a Thermodynamic Cycle

The inequality for the work done during a thermodynamic cycle is calculated, as obtained by Serrin [

12], with the difference that this case is based on bounding the temperature range within which the heat absorption and rejection processes occur in the system.

Following Huilgol and Serrin [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], consider a thermodynamic system

that undergoes a regular thermodynamic cycle. As examples, consider a gas body or an elastic solid. Such a system

is endowed with a set of processes

that it can undergo, denoted by

P,

R,

S, etc. Moreover, the set

of processes has a subset

of reversible and irreversible cyclic processes.

A reversible system

is endowed with a finite-dimensional state space

, which is an open and connected subset of

. For each process

, there exists a corresponding unique path

associated with

, such that

. Where

denotes a closed time interval and the function

is differentiable. In particular, the path of any cyclic process is assumed to be closed, i.e.,

. Additionally, it is assumed that there exist two differential forms

and

defined on

, with constant coefficients. These two expressions have the property of yielding the work done and the heat transferred in a process, and they operate as follows:

where

is the path associated with the process

P.

The first law for any cyclic process of a thermodynamic system takes the form

[

8]. The accumulation function is defined by Serrin as the difference between the heat absorbed by the working substance in a cyclic process,

, and the heat rejected during the cycle,

[

12]. That is,

, so that

Now, consider the finite time interval

of a cycle denoted by

with

. The interval

is defined as the time interval during which the heat transfer rate is positive,

, i.e., a positive amount of heat is absorbed by the cycle. Subsequently, the interval

is defined as the time interval during which heat is rejected by the cycle and therefore

. Finally, the interval

is defined for an adiabatic process where

. According to Huilgol [

17]:

is defined as the heat absorbed by a body and

is the heat rejected by the body. Thenceforth, Diaz used two constant temperatures at the beginning and end of each process that undergoes a thermodynamic cycle [

14]. This means that during the energy transfer process occurring in the interval

, there are minimum and maximum constant temperatures, i.e.,

, ensuring that the temperature during this interval is bounded. Considering the inverse, which is also bounded:

Multiplying (2) by

, which is positive, and integrating over

, it follows that:

where Equation (

3) has been considered and

and

are constants. Similarly, for the interval

with

there are two constant temperatures such that

, and it follows that:

where Equation (

4) has been considered. Next, adding (

6) and (

7) and taking into account that:

Since over

there is an adiabatic process and

, it follows that:

Now, solving Equation (2) for

and substituting into

On the other hand, using

in

It follows that

and, from Equations (2) and (

13), the expression for the first law of thermodynamics derived by Huilgol is obtained [

8]:

The above demonstrates that the first law, as stated by Serrin for cycles, implies an inequality involving the minimum and maximum temperatures of the processes experienced by the system during a cycle, as well as the Clausius integral. In other words, the first law anticipates, so to speak, the importance of this integral in the second law, as pointed out by Huilgol [

8], since it defines the absolute temperature scale.

3. The Accumulation Function for the Ideal Air-Standard Brayton Cycle

The ideal Brayton cycle is a theoretical thermodynamic cycle in which a working fluid undergoes four reversible processes cyclically [

4]. When the working fluid is air, this thermodynamic cycle is also known as the ideal air-standard Brayton cycle and represents the ideal operating processes of a gas turbine [

2]. This cycle operates under the following two main idealizations [

3]:

Under these two assumptions, the properties

and

, referred to as specific heats, remain constant [

4], meaning that:

where the property

is the specific heat ratio. Furthermore, effects on the system due to kinetic and potential energy are neglected; likewise, irreversibilities such as pressure drops due to friction or heat losses to the surroundings are ignored while the air undergoes the processes of a complete cycle [

2].

The processes experienced by the working fluid during a complete cycle are described below [

1,

2,

3,

4]:

- 1-2

Adiabatic compression: Work is done on the air as it transitions from state 1 to state 2, decreasing its volume and increasing its pressure, with no heat exchange. The relationship between the temperatures and pressures of these states is given by the following adiabatic equation:

- 2-3

Isobaric heating: Heat is transferred to the compressed air at high pressure as it transitions from state 2 to state 3, increasing its temperature and volume.

- 3-4

Adiabatic expansion: The high-temperature, high-pressure air expands, performing work and decreasing its temperature and pressure with no heat exchange. The adiabatic equation that relates these two states is:

- 4-1

Isobaric cooling: The low-pressure expanded air transitions from state 4 to state 1 while rejecting heat to the low-temperature reservoir, reducing its volume and temperature and returning to the initial condition of the cycle.

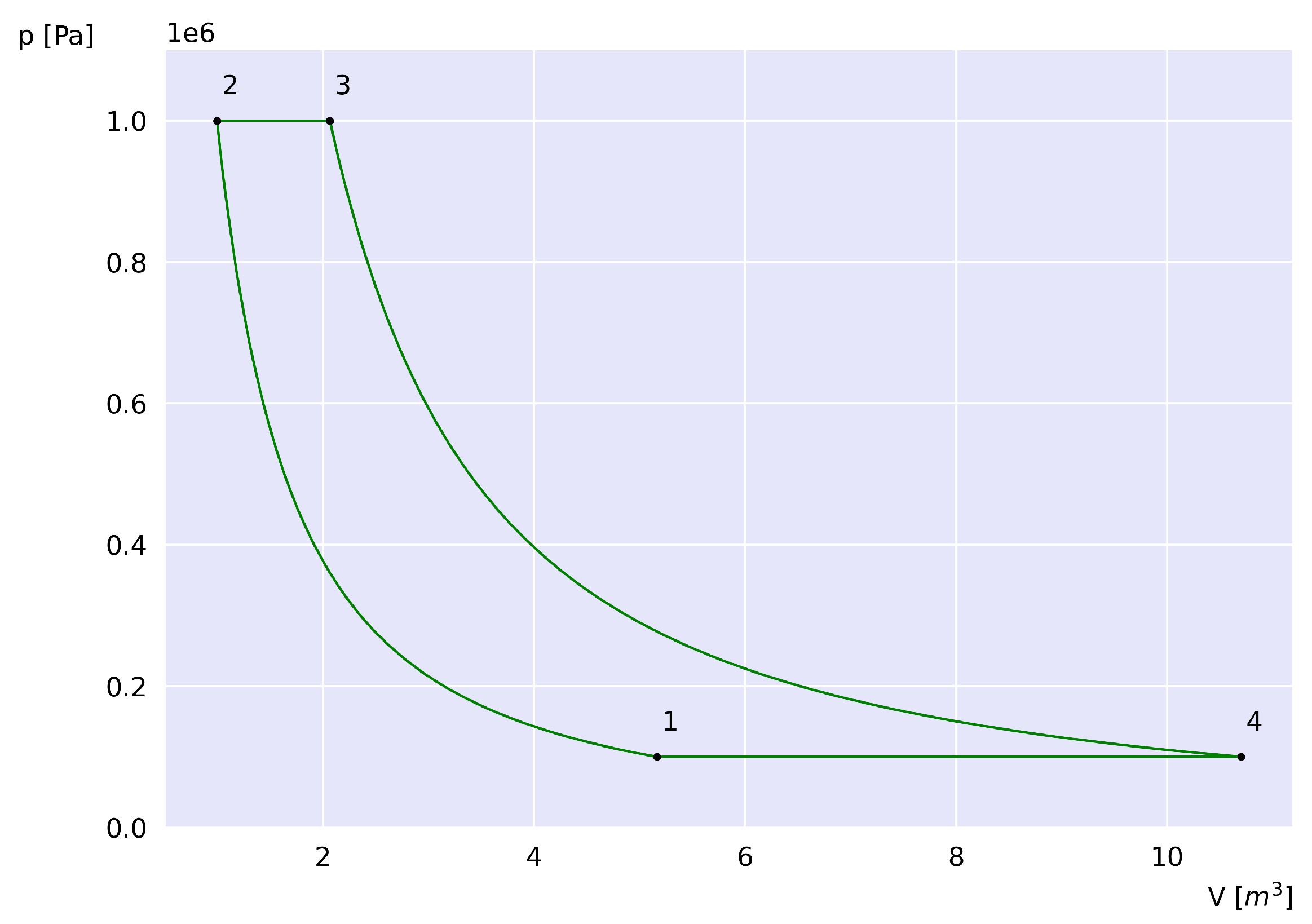

As an exercise to illustrate how energy is transferred and transformed within the system, and whose results will later serve for comparison,

Figure 1 shows the curves of the ideal air-standard Brayton cycle in the p-V plane, where at point 1 the system has a temperature

K, pressure

kPa, number of moles

, and a pressure ratio

, and reaches a temperature

K at point 3.

3.1. Calculation of the Accumulation Function

In the non-adiabatic processes of the ideal air-standard Brayton cycle, it is possible to determine the amount of heat transferred as a function of temperature. However, during the adiabatic processes, such a relationship is difficult to determine because the heat transferred is zero. Specifically, in adiabatic compression no heat is transferred while the temperature increases; similarly, in adiabatic expansion the temperature decreases without any heat exchange. To determine the accumulation function of the ideal air-standard Brayton cycle, the absolute temperature scale

T is considered. Subsequently, from Equations (3) and (3), an equation can be obtained that relates the four temperatures and the two important pressures present in a complete cycle:

Since

,

,

,

and considering Equation (

15), it can be deduced that

. Now, it is necessary to specify how the values of

compare with

. To obtain a relationship between these two temperatures, Equations (

15) and (3) can be used again, and it is found that, for

to hold, the following condition must be satisfied:

where

r is the pressure ratio of the process 1-2. That is,

will be greater than

whenever Equation (

19) holds. However, when

, the less than symbol in Equation (

19) changes to a greater than symbol since

.

Next, during the isobaric heating process corresponding to the transition from state 2 to state 3, the accumulation function must ensure that the heat absorption process occurs at constant pressure,

. Thus:

And employing the Heaviside function, which works as follows

,

,

,

, the following is obtained:

For

. Similarly, during process 4-1, the heat rejection process occurs at

, yielding:

And using the Heaviside function:

For

. Consequently, over a complete cycle, it follows that:

For

. Therefore, the accumulation function over the positive real axis is:

To verify that this function is correct, it must satisfy Serrin’s Accumulation Theorem and Clausius’ integral for a cycle. First, from the Accumulation Theorem, it follows that:

By evaluating each integral and eliminating similar terms, the expression simplifies to:

However, from Equations (3) and (3), it follows that the four temperatures satisfy the following condition:

Then, using the result given by Equation (

27), it is found that the function Q satisfies the integral from the Accumulation Theorem, namely:

Finally, for Clausius’ integral, it follows that over a complete cycle:

And from Equation (

28), it follows that

Thus, Q also satisfies Clausius’ integral for a complete cycle.

3.2. Example Case

To illustrate the application of the accumulation function Equation (

25) for the ideal air-standard Brayton cycle and to analyze how it describes the behavior of the exchanged heat and explicitly identifies the key temperatures over a complete cycle, consider that air enters the compressor of an ideal cold air-standard Brayton cycle at 100 kPa, 300 K, and

. First, the value of

relative to

must be considered.

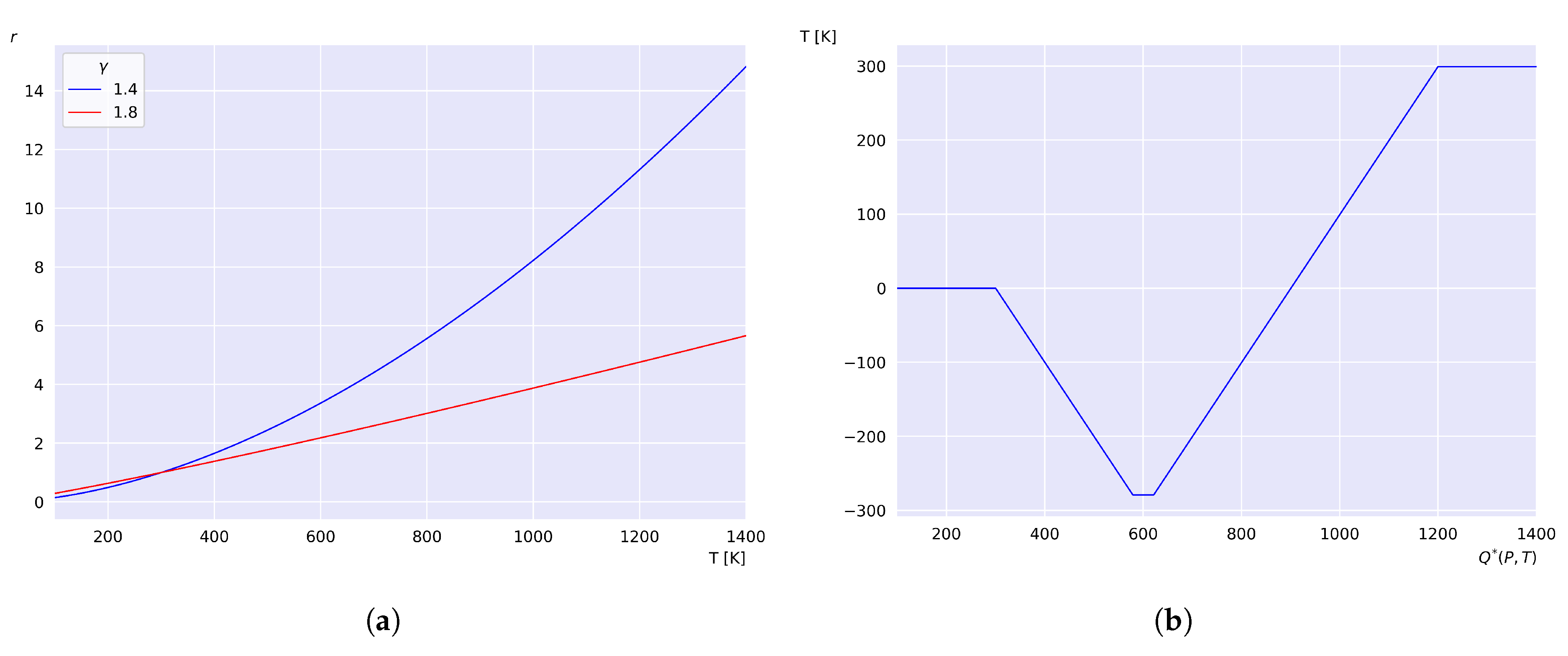

Figure 2 (a) shows the behavior of

r as a function of

. Taking

K and

, it is obtained that

K and

K, satisfying the condition established by Equation (

19). The accumulation function according to Equation (

25) for these values is:

The behavior of

as a function of

T is shown in

Figure 2 (b), where it has been defined such that

. It can be observed that the heat remains constant at zero for values below

, corresponding to the heat exchanged between the system and the environment prior to state 1, as shown in the p-V diagram in

Figure 1. During process 4-1, the amount of heat decreases as the temperature drops from

to

. Then, the heat remains constant for temperature values between

and

. Upon reaching

, the heat begins to increase until the temperatures approaches

are reached. The total exchanged heat is obtained upon reaching

and remains constant for

T, i.e., during the compression process 1-2, and the expansion process 3-4 the heat remains constant. The accumulation function given by Equation (

25) explicitly determines the amount of heat transferred up to and including any temperature at any system state during each process, including the four key temperatures of the cycle.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

In this work, the explicit form of the accumulation function for the ideal air-standard Brayton cycle is presented, derived from Serrin’s thermodynamics. It compares the four temperatures and the relationship that must hold when is less than . Furthermore, it is shown that the accumulation function satisfies Serrin’s accumulation theorem and Clausius’ integral over a complete cycle, in agreement with classical thermodynamics.

The derivation of the inequality for the work done in a thermodynamic cycle is also shown, taking into account the restriction imposed by the accessible range of the processes involved in the cycle. With this expression, a continuous representation of the heat exchange behavior during each process of the cycle is obtained, clearly showing the key temperatures , , , and . This approach facilitates the physical interpretation of the heat transfer process and energy accumulation across the entire temperature range.

The example case shows that during the adiabatic processes, heat remains constant, while in the isobaric processes, energy changes occur as a result of heat absorption and rejection.

The accumulation function is a piecewise continuous function that enables the analysis of how the system exchanges heat at each temperature interval experienced by the processes. This could help identify which range of the cycle requires more energy for heating or cooling and determine zones where heat recovery is feasible.

Furthermore, in applications where a heat recuperator is integrated, the Q function provides a simple framework for evaluating the impact of residual heat and its potential reuse. The Q function offers a quick reference for how much heat can be extracted and at what temperature, which could aid in designing more efficient heat exchangers. The Q function represents a perspective distinct from that studied in standard thermodynamics courses, providing a clear reference for the transition temperatures between each process and helping to identify the global thermodynamic behavior of the cycle.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.J.S.-S.; methodology, V.A.J.S.-S.; software, V.A.J.S.-S.; validation, V.A.J.S.-S.; formal analysis, V.A.J.S.-S.; investigation, V.A.J.S.-S.; resources, V.A.J.S.-S.; data curation, V.A.J.S.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.J.S.-S.; writing—review and editing, V.A.J.S.-S.; visualization, V.A.J.S.-S.; supervision, P.Q.D.; project administration, V.A.J.S.-S.; funding acquisition, V.A.J.S.-S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zemansky, M. W.; Dittman, R. H. Heat and Thermodynamics, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1997; 784p. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, M. J.; Shapiro, H. N.; Boettner, D. D.; Bailey, M. B. Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics; John Wiley & Sons: U.S.A, 2010; 880p. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, I.; Müller, W. H. Fundamentals of Thermodynamics and Applications: With Historical Annotations and Many Citations from Avogadro to Zermelo; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin Heidelberg, 2009; XVI, 404p. [Google Scholar]

- Çengel, Y. A.; Boles, M. A. Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY 10121, 2018; 1008p. [Google Scholar]

- Clausius, R. On a modified form of the second fundamental theorem in the mechanical theory of heat. In Fourth Memoir, Mechanical Theory of Heat with its Applications to the Steam Engine and to the Physical Properties of Bodies; Hirst, T. A., Ed.; John van Voorst: London, 1867; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- GH, B. Treatise on Thermodynamics. Nature 1903, 69(1783), 194–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W. (Lord Kelvin). On the dynamical theory of heat: with numerical results deduced from Mr. Joule’s equivalent of a thermal unit and M. Regnault’s observations on steam. Trans. R. Soc. Edinburgh 1882, and Phil. Mag. IV, 1852. Reprinted in Mathematical and Physical Papers, I; Cambridge University Press.

- Huilgol, R. R. Serrin’s accumulation function, the First and the Second Laws of Thermodynamics. Applications in Engineering Science 2021, 7, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. C. Theory of Heat; Longmans, Green, and Company: U.S.A, 1872; p. 333. [Google Scholar]

- Mach, E. Principles of the Theory of Heat, Translation of the Second Ed. of Die Principien Der Warmelehre (in German); McGuiness, B., Ed.; Reidel Publishing: Dordrecht, Holland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Serrin, J. Conceptual analysis of the classical second laws of thermodynamics. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis 1979, 70(4), 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrin, J. An outline of thermodynamical structure. In New Perspectives in Thermodynamics; Serrin, J., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, 1986; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Huilgol, R. R. The role of Clausius’ and entropy inequalities in thermodynamics. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 1979, 7, 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, J. B. Mathematical prolegomena to every theory of homogeneous heat engines. SIAM Rev. 1978, 20(2), 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrin, J. On the elementary thermodynamics of quasi-static systems and other remarks. In Thermoelastic Problems and the Thermodynamics of Continua; ASME Applied Mechanics Division: 1995; pp. 53–62, AMD-198.

- Man, C.-S.; Massoudi, M. On the thermodynamics of some generalized second-grade fluids. Continuum Mech. Thermodyn. 2010, 22(1), 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huilgol, R. R. Improved bounds for the work done by irreversible heat engines. Lett. Heat Mass Transf. 1978. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).