Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Objectives and Questions

- RQ1: What were the main public health communication challenges encountered by post-Soviet countries during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- RQ2: In what ways did the historical background of public health communication in post-Soviet nations shape the way they responded to COVID-19?

- RQ3: What lessons can be learned from the public health communication experiences of post-Soviet countries during COVID-19 to improve future health crisis communication?

2.2. Protocol and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategies

2.4. Selection of Sources of Evidence

- Title and Abstract Screening: The titles and abstracts of all records were screened independently by three reviewers (A.M., A.A. and A.E.) against the eligibility of criteria. Studies that clearly did not meet the criteria were excluded.

- Full-text Screening: The full text of potential relevant sources was retrieved and assessed in detail for eligibility by the same three reviewers working independently.

2.5. Data Charting Process and Data Items

- Bibliographic details: Author(s), publication, title, source.

- Context: Country or countries of focus.

-

Key findings: Relevant data pertaining to research questions, including:

- Historical background of the health system

- Regional healthcare inequalities

- Health communication practices

- Identified challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic (misinformation, public trust, politicization)

2.6. Critical Appraisal of Individual Source of Evidence

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Selection and Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Thematic Synthesis of Results

3.2.1. Background of Healthcare Systems During and Post-Soviet Era

3.2.2. Centralized Hierarchical Healthcare

3.2.3. Financial Constraints of Healthcare Systems

3.2.4. Regional Healthcare Inequality between Rural and Urban

3.2.5. Health Communication: Soviet Legacy to Contemporary Practice

3.2.6. Health Communication and Communicators Across the Post-Soviet Nations

3.2.7. Crisis Communication During the Pandemic

3.2.8. Lack of Institutional Communication Framework

3.2.9. Communication Challenges in Post-Soviet States During and Post COVID-19

Data Transparency and Accuracy

Politicization of Public Health Measures

Politicization of Lockdowns and Surveillance

Politicization of Vaccination Campaigns

Border Controls and Their Social Implications

The Spread and Management of Misinformation and Disinformation

Lack of Trust in Government and Institutions

Lack of Community Engagement

Vaccine Hesitancy

4. Discussion

4.1. Healthcare Systems Challenges

4.2. Regional Healthcare Inequality Issues

4.3. Health Communication and Communicators Challenges

4.4. Crisis Communication Challenges During COVID-19

4.5. Lack of Public Engagement Challenges

4.6. Vaccine Hesitancy and Lack of Trust in Government Issues

5. Limitation of the Scoping Review and Conclusion

5.1. Limitation of the Scoping Review

5.2. Recommendations

5.3. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Search Strategy for Google Scholar

Appendix B

| No | Author(s), Year | Document Type | Country Focus | Key Themes Addressed | Relevant RQ |

| 1 | Semenova et al., 2024 | Journal Article | Regional (9 countries) | Historical health systems, inequalities, COVID-19, data transparency | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 2 | Glushkova et al., 2023 | Journal Article | Regional (9 countries) | Historical health systems, COVID-19, data transparency, public trust | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 3 | Karpov & Makhnev, 2017 | Journal Article | Regional (9 countries) | Historical health systems | RQ2 |

| 4 | World Health Organization | WHO Report | Regional (9 countries) | Historical background of the health system | RQ2 |

| 5 | Karlinsky & Kobak, 2021 | Journal Article | All countries except Turkmenistan | COVID-19, data transaperncy | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 6 | Kilani & Georgiou, 2021 | Journal Article | Belarus, Tajikistan, Russia, and Uzbekistan | COVID-19, data transaperncy | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 7 | Knox et al., 2023 | Book Chapter | Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkmenistan | COVID-19, data transaperncy, politicization | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 8 | Rechel, B, Sydykova, A, et al., 2023 | Journal Article | Central Asia | Historical health systems | RQ2 |

| 9 | McKee et al., 1998 | Journal Article | Central Asia | Historical health systems | RQ2 |

| 10 | Moreno-Serra & Wagstaff, 2010 | Journal Article | Central Asia | Health system, reforms, inequalities | RQ2 |

| 11 | Akhunov, 2020 | Journal Article | Central Asia | COVID-19, health communication, data transaperncy | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 12 | Lemon & Antonov, 2021 | Working paper | Central Asia | COVID-19, health communication, politicization, misinformation | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 13 | Khan, 2021 | Working paper | Central Asia | COVID-19, health communication, misinformation | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 14 | Torosyan et al., 2008 | Journal Article | Armenia | Historical health systems, reforms, inequalities | RQ2 |

| 15 | Avakyan et al., 2013 | Journal Article | Armenia | Health system, inequalities | RQ2 |

| 16 | Breen et al., 2023 | Journal Article | Armenia | Health system, health communication | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 17 | Barseghyan, et al., 2021 | Freedom House Report | Armenia | COVID-19, health communication, politicization, misinformation | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 18 | United Nations in Armenia | Press Release | Armenia | COVID-19, health communication | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 19 | Permanent Representation of the Republic of Armenia to the Council of Europe, 2020 | Press Release | Armenia | COVID-19, health communication | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 20 | Graefen & Fazal, 2024 | Journal Article | Azerbaijan | Health system, public engagement | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 21 | Aliyev, 2021 | Journal Article | Azerbaijan | COVID-19, health communication, public trust | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 22 | Unlu et al., 2022 | Journal Article | Azerbaijan | COVID-19, health communication, public engagement | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 23 | Graefen et al., 2023 | Journal Article | Azerbaijan | COVID-19, health communication, public engagement | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 24 | Quliyeva & Huseynov, 1999 | Journal Article | Azerbaijan | Health system, inequalities | RQ2 |

| 25 | Ibrahimov et al., 2010 | Journal Article | Azerbaijan | Historical health systems, health communication | RQ2 |

| 26 | World Bank, n.d. | World Bank Report | Azerbaijan | Health system | RQ2 |

| 27 | UNICEF in Azerbaijan, 2025 | UNICEF Report | Azerbaijan | Health system | RQ2, RQ3 |

| 28 | Webb & Gulu, 2024 | WHO Report | Azerbaijan | Health system, reforms, public engagement, inequalities | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 29 | Human Rights Watch, 2020 | Human Rights Watch Report | Azerbaijan | COVID-19, health communication, politicization | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 30 | Richardson et al., 2008 | Journal Article | Belarus | Health communication | RQ2 |

| 31 | Polyakova, 2020 | Journal Article | Belarus | COVID-19, health communication, politicization | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 32 | Pierson-Lyzhina, et al., 2021 | Journal Article | Belarus | COVID-19, health communication, data transparency, misinformation | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 33 | Skarphedinsdottir et al., 2015 | WHO Report | Belarus | Public communication, public engagement, inequalities | RQ2 |

| 34 | Richardson et al., 2013 | WHO Report | Belarus | Historical health systems, reforms, inequalities, public engagement | RQ2 |

| 35 | Webb, 2024 | WHO Report | Belarus | Health system, health communication | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 36 | Gulis et al., 2021 | Journal Article | Kazakhstan | Health system, reforms, inequalities | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 37 | Kumar et al., 2013 | Journal Article | Kazakhstan | Health system, reforms | RQ2 |

| 38 | Iskakov, 2025 | Journal Article | Kazakhstan | Health communication, trust | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 39 | Bukharbayeva et al., 2022 | Journal Article | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication, public trust | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 40 | Haruna et al., 2022 | Journal Article | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication, vaccination | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 41 | Nurumov et al., 2020 | Working paper | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication, public communication | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 42 | Sharipova & Beissembayev, 2021 | Block Post | Kazakhstan | Health system, inequalities, COVID-19 | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 43 | Amagoh, 2021 | Book | Kazakhstan | Historical health systems, reforms, inequalities | RQ2 |

| 44 | Kadyrova, 2020 | Book | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication | RQ1, RQ2, PQ3 |

| 45 | Nair et al., 2020 | Book | Kazakhstan | Policy communication | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 46 | Abisheva et al. 2020 | Book Chapter | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication, trust | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 47 | Dulambayeva & Marmontova, 2021 | Book Chapter | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication, public engagement | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 48 | Kapkyzy, 2021 | Book Chapter | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication, disinformation | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 49 | Sultanbayeva et al., 2021 | Book Chapter | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication, public engagement | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 50 | Urpekova et al., 2022 | Book Chapter | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication, framing | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 51 | Kydyrbaev, 2021 | Book chapter | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 52 | UNICEF in Kazakhstan, 2022 | UNICEF Report | Kazakhstan | Health communication, vaccination | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 53 | Dzhalilov et al., 2022 | UNICEF Report | Kazakhstan | COVID-19, health communication, disinformation, vaccination | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 54 | Salehi et al., 2022 | UNICEF Report | Kazakhstan | Institutional capacity, trust, vaccination | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 55 | Katsaga & Kulzhanov, 2012 | WHO Report | Kazakhstan | Historical health systems, reforms | RQ2 |

| 56 | Kulzhanov, 2017 | WHO Report | Kazakhstan | Historical health systems, Health communication | RQ2 |

| 57 | OECD, 2018 | OECD Review | Kazakhstan | Historical health systems, reforms | RQ2 |

| 58 | Ministry of Healthcare of Kazakhstan, 2024 | Press Release | Kazakhstan | Historical health systems, Health communication | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 59 | Committee for Sanitary and Epidemiological Control of the Ministry of Healthcare of Kazakhstan | Press Release | Kazakhstan | Historical health systems, Health communication | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 60 | Bruley & Mamadiiarov, 2020 | Journal Article | Kyrgyzstan | COVID-19, health communication, public trust | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 61 | Moldoisaeva et al., 2022 | Journal Article | Kyrgyzstan | Health system, reforms, public engagement, health communication | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 62 | Verma, 2020 | UNICEF Report | Kyrgyzstan | Health communication | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 63 | Shok & Beliakov, 2020 | Journal Article | Russia | Health communication, COVID-19, trust, manipulation | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 64 | Sheiman et al., 2018 | Journal Article | Russia | Historical health systems, Soviet legacy | RQ2 |

| 65 | Popovich et al., 2011 | Journal Article | Russia | Historical health systems, reforms, inequalities | RQ2 |

| 66 | Antonova, 2009 | Journal Article | Russia | Health communication | RQ2 |

| 67 | Nikitina & Nikitin, 2015 | Journal Article | Russia | Health communication | RQ2 |

| 68 | Popov, 2021 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, politicization, vaccination, trust | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 69 | Kotseva et al., 2023 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, politicization, vaccination | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 70 | Golunov & Smirnova, 2022 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, health communication | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 71 | Nisbet & Kamenchuk, 2021 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, health communication, misinformation | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 72 | Stoycheff et al, 2020 | Journal Article | Russia | Public communication, transparency | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 73 | Cooper & Fellow, 2020 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, health communication, trust | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 74 | Sukhankin, 2020 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, health communication, transparency, trust | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 75 | Tulchinskii, 2020 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, health communication, trust | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 76 | Pankratov & Morozov, 2021 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, health communication, public engagement | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 77 | King & Dudina, 2021 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, health communication, data transparency | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 78 | Litvinenko et al., 2022 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, health communication, politicization | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 79 | Kofanov et al., 2023 | Journal Article | Russia | COVID-19, health communication, data transaperncy | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 80 | Endaltseva, 2020 | Book Chapter | Russia | Actors, fragmentation, media role | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 81 | Volkovskii & Filatova, 2025 | Conference paper | Russia | COVID-19, health communication, public engagement | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 82 | Mukhtarova, 2022 | Journal Article | Tajikistan | Health system, public engagement, inequalities | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 83 | Boboyorov, 2021 | Book chapter | Tajikistan | COVID-19, health communication, misinformation, transparency | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 84 | Sodiqova et al., 2025 | WHO Report | Tajikistan | Health communication | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 85 | Robinson et al., 2024 | WHO Report | Tajikistan | Health system, reforms, inequalities | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 86 | World Bank, 2022 | World Bank Report | Tajikistan | Public Expenditure (health system) | RQ2 |

| 87 | Yaylymova, 2020 | Journal Article | Turkmenistan | COVID-19, health communication, misinformation, transparency | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 88 | Hashim et al, 2022 | Journal Article | Turkmenistan | COVID-19, health communication, misinformation, transparency | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 89 | Ahmedov et al., 2015 | Journal Article | Uzbekistan | Health system, reforms | RQ2 |

| 90 | Cancarini, 2020 | Journal Article | Uzbekistan | COVID-19, health communication | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 91 | Vikhrov et al., 2021 | Journal Article | Uzbekistan | COVID-19, health communication, public engagement | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 92 | Lemon, 2019 | Working paper | Uzbekistan | COVID-19, health communication, politicization | RQ1, RQ3 |

| 93 | Robinson & Yin, 2024 | WHO Report | Uzbekistan | Health system, reforms, public engagement | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 94 | Robinson, 2023 | WHO Report | Uzbekistan | Health system, health communication | RQ1, RQ2 |

| 95 | United Nations, 2024 | UN Report | Uzbekistan | Health system | RQ2 |

| 96 | UNICEF in Uzbekistan, n.d. | UNICEF Report | Uzbekistan | Health system | RQ2 |

| 97 | Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan, n.d. | Press Release | Uzbekistan | Health system | RQ2 |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Competency Framework, Risk Communication and Community Engagement: For Stronger and More Inclusive Health Emergency Programmes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376653/9789240092501-eng.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Tench, R.; Meng, J.; Moreno, A. Preface and Introduction. In Strategic Communication in a Global Crisis: National and International Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic, 1st ed.; Tench, R., Meng, J., Moreno, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 3–12.

- MacKay, M.; Colangeli, T.; Gillis, D.; McWhirter, J.; Papadopoulos, A. Examining Social Media Crisis Communication during Early COVID-19 from Public Health and News Media for Quality, Content, and Corresponding Public Sentiment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021; 18, 7986. [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.; Chattu, V. Strengthening the COVID-19 pandemic response, global leadership, and international cooperation through global health diplomacy. Health promotion perspectives, 2020, 10, 300-306.

- Micah, A. E.; Bhangdia, K.; Cogswell, I. E.; Lasher, D.; Lidral-Porter, B.; Maddison, E.; Hlongwa, M. Global investments in pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: development assistance and domestic spending on health between 1990 and 2026. The Lancet Global Health, 2023; 11, pp. 385-413.

- Shok, N.; Beliakova, N. How Soviet Legacies Shape Russia's Response to the Pandemic: Ethical Consequences of a Culture of Non-Disclosure. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 2020; 30, 379-400. [CrossRef]

- Skarphedinsdottir, M.; Mantingh, F.; Jurgutis, A.; Johansen, A. S.; Elmanova, T.; Belarus Country Assessment; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015; WHO/EURO: 2015-6191-45956-66362. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/363342/WHO-EURO-2015-6191-45956-66362-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Harrington, N.G. Persuasive Health Message Design. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication; Harrington, N.G., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O'Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, *169*, 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Sheiman, I.; Shishkin, S.; Shevsky, V. The Evolving Semashko Model of Primary Health Care: The Case of the Russian Federation. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2018, 11, 209–220. [CrossRef]

- Semenova, Y.; Lim, L.; Salpynov, Z.; Gaipov, A.; Jakovljevic, M. Historical Evolution of Healthcare Systems of Post-Soviet Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan: A Scoping Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29550. [CrossRef]

- Endaltseva, A. Communication and Health Knowledge Production in Contemporary Russia: From Institutional Structures to Intuitive Ecosystems. In Strategic Communications in Russia; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 206–218. [CrossRef]

- Rechel, B.; Sydykova, A.; Moldoisaeva, S.; Sodiqova, D.; Spatayev, Y.; Ahmedov, M.; Robinson, S.; Sagan, A. Primary Care Reforms in Central Asia – On the Path to Universal Health Coverage? Health Policy OPEN 2023, 5, 100110. [CrossRef]

- Gulis, G.; Aringazina, A.; Sangilbayeva, Z.; Kalel, Z.; de Leeuw, E.; Allegrante, J. P. Population Health Status of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Trends and Implications for Public Health Policy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18(22), 12235. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.; Malakhova, I.; Novik, I.; Famenka, A. Belarus: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2013, 15(5), 1–118. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/330303 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Amagoh, F. Healthcare Policies in Kazakhstan: A Public Sector Reform Perspective; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Izekenova, A.; Abikulova, A. Inpatient Care in Kazakhstan: A Comparative Analysis. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013, 18(7), 549–554.

- Popovich, L.; Potapchik, E.; Shishkin, S.; Richardson, E.; Vacroux, A.; Mathivet, B. Russian Federation: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2011, 13(7), 1–190.

- Torosyan, A.; Romaniuk, P.; Krajewski-Siuda, K. The Armenian Healthcare System: Recent Changes and Challenges. J. Public Health 2008, 16(3), 183–190. [CrossRef]

- Katsaga, A.; Kulzhanov, M. Kazakhstan: Health System Overview. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO, 2012. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/330319/HiT-14-4-2012-eng.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Graefen, B.; Fazal, N. Quality as a Driver of Progress: Tuberculosis Care in Azerbaijan. Indian J. Tuberculosis 2024, 71(3), 344–352. [CrossRef]

- Webb, E.; Gulu, T. Health Systems in Action (HSiA) Insights – Azerbaijan, 2024; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; pp. 1–24.

- Robinson, S.; Yin, J. Health Systems in Action (HSiA) Insights – Uzbekistan, 2024; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; pp. 1–24.

- World Bank. Tajikistan Public Expenditure Review: Strategic Issues for the Medium-Term Reform Agenda, Washington, D.C., 2022. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099605011142224145 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Robinson, S.; Dastan, I.; Rechel, B. Health Systems in Action (HSiA) Insights – Tajikistan; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO Regional Office for Europe: 2024; pp. 1–24.

- Glushkova, N.; Semenova, Y.; Sarria-Santamera, A. Public Health Challenges in Post-Soviet Countries During and Beyond COVID-19. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1290910. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Serra, R.; Wagstaff, A. System-Wide Impacts of Hospital Payment Reforms: Evidence from Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. J. Health Econ. 2010, 29(4), 585–602.

- Karpov, O.; Makhnev, D. Models of Health Care Systems of Different Countries and Common Problems in the Sphere of Public Health Protection [Мoдели систем здравooхранения разных гoсударств и oбщие прoблемы сферы oхраны здoрoвья населения]. Bull. Natl. Med. Surg. Cent. N.I. Pirogov 2017, 12(3), 92–100. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/modeli-sistem-zdravoohraneniya-raznyh-gosudarstv-i-obschie-problemy-sfery-ohrany-zdorovya-naseleniya (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Moldoisaeva, S.; Kaliev, M.; Sydykova, A.; Muratalieva, E.; Ismailov, M.; Madureira Lima, J.; Rechel, B. Kyrgyzstan: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2022, 24(3), i–152. Available online: https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/4676265/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Ahmedov, M.; Azimov, R.; Mutalova, Z.; Figueras, J.; Huseynov, S.; Tsoyi, E. Challenges to Universal Coverage in Uzbekistan. Eurohealth 2015, 21(2), 17–19.

- OECD. OECD Reviews of Health Systems: Kazakhstan; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Avakyan, M.; Avakyan, V.; Kirakosyan, G.; Kirakosyan, R.; Yagdzhyan, G. On the Development of Telemedicine in the Republic of Armenia [К вoпрoсу o развитии телемедицины в Республике Армения]. Med. Educ. Prof. Dev. 2013, 4(14), 42–54.

- McKee, M.; Figueras, J.; Chenet, L. Health Sector Reform in the Former Soviet Republics of Central Asia. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 1998, 13(2), 131–147. [CrossRef]

- Sharipova, D.; Beissembayev, S. The Social Impact of COVID-19 on Kazakhstan: An Overview of Standards of Living and Access to Welfare Services. Working Paper No. 38; French Institute for Central Asia Studies (IFEAC), 2021. Available online: https://ifeac.hypotheses.org/7202 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Quliyeva, D.; Huseynov, S. Primary Health Care Revitalization in Azerbaijan. Prim. Health Care 1999, 40(2). Available online: https://neuron.mefst.hr/docs/CMJ/issues/1999/40/2/10234064.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Freedman, E.; Shafer, R.; Antonova, S. Two Decades of Repression: The Persistence of Authoritarian Controls on the Mass Media in Central Asia. Cent. Asia Cauc. 2010, 11, 94–109.

- Richardson, E.; Boerma, W.; Malakhova, I.; Rusovich, V.; Fomenko, A. Belarus: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2008, 10(6), 1–118. Available online: https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/1410540/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Salehi, A.; Aiypkhanova, A.; Hanna, J.; James, L.; Ristivojevic, V.; Faizi, S.; Aitenova, A.; Jelbuldina, U. Communication Capacity Assessment of Health Care System in Kazakhstan in Relation to Vaccination Against COVID-19; UNICEF: Kazakhstan, 2022. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/kazakhstan/en/reports/communication-capacity-assessment-health-care-system-kazakhstan (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Kadyrova, A. Crisis Communication Strategies during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Kazakhstan; Astana Civil Service Hub: Astana, 2020. Available online: https://repository.apa.kz/bitstream/handle/123456789/425/5_RUS.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Kulzhanov, M. Central Asian Countries: Ensuring a Polio-Free Europe. In Health Diplomacy: European Perspectives; Kickbusch, I.; Kökény, M., Eds.; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, 2017; pp. 75–81. Available online: https://iris.who.int/items/5ea313eb-8747-4ef6-b769-19e7f8952755 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- United Nations in Armenia. Armenia and WHO Assess the Role and Achievements of the National Health Digitalization System for Better Quality, Affordable and Equitable Care for All [Press Release]. 2 November 2022. Available online: https://armenia.un.org/en/205764-armenia-and-who-assess-role-and-achievements-national-health-digitalization-system-better (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Ibrahimov, F.; Ibrahimova, A.; Kehler, J.; Richardson, E. Azerbaijan: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2010, 12(3), 1–115. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21132995/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zeemering, E. Functional Fragmentation in City Hall and Twitter Communication during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Atlanta, San Francisco, and Washington, DC. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38(1), 101539. [CrossRef]

- Antonova, N. Public Awareness of Rights in the Field of Health Protection: The Role of the Media [Инфoрмирoваннoсть населения o правах в oбласти oхраны здoрoвья: рoль СМИ]. In Proceedings of the 12th All-Russian Scientific and Practical Conference of the Humanitarian University; Vol. 2, pp. 274–276. Available online: https://elibrary.ru/download/elibrary_44904647_58025033.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Nikitina, T.I.; Nikitin, A.A. The Role of Mass Media as a Tool for Supporting State Information Policy in Healthcare in Promoting a Healthy Lifestyle [Рoль средств массoвoй инфoрмации как инструмента инфoрмациoннoй пoддержки гoсударственнoй пoлитики в сфере здравooхранения при пoпуляризации здoрoвoгo oбраза жизни]. In Инфoрмациoннoе пoле сoвременнoй Рoссии: практики и эффекты; pp. 462–469. Available online: https://kpfu.ru/portal/docs/F766540947/Informpole_2015.pdf#page=462 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Nutbeam, D. Health Literacy as a Public Health Goal: A Challenge for Contemporary Health Education and Communication Strategies into the 21st Century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15(3), 259–267. [CrossRef]

- Webb, E. Health Systems in Action (HSiA) Insights – Belarus; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, 2024. Available online: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/health-systems-in-action-belarus-2024#:~:text=Belarus'%20health%20system%20is%20centralized (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Kazakhstan. Communication Capacity Assessment of Health Care System in Kazakhstan in Relation to Vaccination Against COVID-19; UNICEF: Kazakhstan, 2022. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/kazakhstan/media/9196/file/Communication%20Capacity%20Assessment%20of%20Health%20Care%20System%20in%20Kazakhstan%20in%20Relation%20to%20Vaccination%20Against%20COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Iskakov, O. Communication Strategies and Interaction with the Media to Increase Trust in Healthcare Leaders in Kazakhstan [Кoммуникациoнные стратегии и взаимoдействие сo СМИ для пoвышения дoверия к рукoвoдителям здравooхранения в Казахстане]. Probl. Mod. Sci. Educ. 2025, (1[200]), 33–37.

- Robinson, S. Health Systems in Action (HSiA) Insights – Uzbekistan, 2022; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, 2023. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/362328/9789289059220-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Cancarini, D. Uzbekistan and COVID-19: A Communication Perspective. Cent. Asian Progr. 2020, 3(3), Paper No. 235. Available online: https://centralasiaprogram.org/archive/program-series/uzbekistan-and-covid-19-a-communication-perspective/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- United Nations. UN Country Results Report 2024 – Uzbekistan; United Nations: Tashkent, 2025. Available online: https://uzbekistan.un.org/en/293874-un-country-results-report-2024 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan. Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan. Available online: https://minzdrav.uz (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Global Health Expenditure Database. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Uzbekistan. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/uzbekistan (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Verma, N. Standardization of Telemedicine Services in Kyrgyzstan—Recommendations for Policy; UNICEF: Bishkek, 2020. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/kyrgyzstan/media/7381/file/Standardization%20of%20telemedicine%20services%20in%20Kyrgyzstan.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Sodiqova, D.; Muhsinzoda, G.; Dorghabekova, H.; Makhmudova, P.; et al. Tajikistan: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2025; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/381430 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Mukhtarova, P. Kommunikativnyye Strategii v Oblasti Zdravookhraneniya i Ikh Osobennosti v Respublike Tadzhikistan [Strategies of Communication in the Sphere of National Healthcare and Their Peculiarities in the Republic of Tajikistan]. Med. Bull. Natl. Acad. Sci. Tajikistan 2022, 12(3), 99–107. Available online: https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=49833212 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Breen, R.; Ghazaryan, A.; Paronyan, L.; Gevorgyan, K.; Shcherbakov, O.; Gevorgyan, H.; Olival, K. One Health Armenia: An Assessment of One Health Operations and Capacities. EcoHealth Alliance 2023. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Azerbaijan: Country Overview. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/azerbaijan (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Azerbaijan: Programme and Reports. UNICEF Azerbaijan, 2025. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/azerbaijan (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Petra, D.; Thomas, A.; Satyajit, S.; Piotr, W.; Sabrina, C.; Franklin, A.; Ülla-Karin, N. Risk Communication as a Core Public Health Competence in Infectious Disease Management: Development of the ECDC Training Curriculum and Programme. Euro Surveill. 2016, 21(14), 30188. [CrossRef]

- Kondilis, E.; Papamichail, D.; Gallo, V.; Benos, A. COVID-19 Data Gaps and Lack of Transparency Undermine Pandemic Response. J. Public Health 2021, 43(2), e307–e308.

- Pankratov, S.; Morozov, S. “Distant” Communication: Transformation of Interaction Between Russian Society and Authorities in the Era of the Global Pandemic. Vestn. Volgograd. Gos. Univ. Ser. 4 Istor. Region. Mezhdunar. Otn. [Sci. J. Volgograd State Univ. Ser. 4 Hist. Area Stud. Int. Relat.] 2021, 26(3), 172–181. [CrossRef]

- King, E.; Dudina, V. COVID-19 in Russia: Should We Expect a Novel Response to the Novel Coronavirus? Glob. Public Health 2021, 16(8–9), 1237–1250.

- Litvinenko, A.; Borissova, A.; Smoliarova, A. Politicization of Science Journalism: How Russian Journalists Covered the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journalism Stud. 2022, 23(5–6), 687–702. [CrossRef]

- Pierson-Lyzhina, E.; Kovalenko, O.; Saralidze, L. Government Communication and Public Resilience to Propaganda during COVID-19. ResearchGate 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364330603_Government_communication_Government_communication_and_public_resilience_and_public_resilience_to_propaganda_during_to_propaganda_during_COVID-19_COVID-19 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Abisheva, M.; Dulambayeva, R.; Dzhumabaev, S.; Marmontova, T.; Baglay, B. Public Administration during a Pandemic; Abisheva, M., Dulambayeva, R., Eds.; Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan, 2020; p. 139.

- Dulambayeva, R.; Marmontova, T. Kak Luchshe Naladit’ Kommunikatsiyu Mezhdu Vlast’yu i Obshchestvom: Vyzovy COVID-19 dlya Gosudarstvennogo Upravleniya [How to Better Establish Communication between Government and Society: COVID-19 Challenges for Public Administration]. In Kazakhstan and COVID-19: Media, Culture, Politics; Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2021; pp. 14–30.

- Kapkyzy, Ye. Konspirologicheskiye Teorii i Dezinformatsiya v Kazakhskoyazychnykh SMI [Conspiracy Theories and Disinformation in Kazakh-Language Media]. In Kazakhstan and COVID-19: Media, Culture, Politics; Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2021; pp. 202–213. Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/kasachstan/18218.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Nurumov, B.; Berkenova, G.; Freedman, E.; Ibrayeva, G. Informing the Public about the Dangers of a Pandemic. Early COVID-19 Coverage by News Organizations in Kazakhstan. Central Asia Program Papers 2020, No. 248. Available online: https://www.centralasiaprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CAP-Paper-248-by-Bakhtiyar-Nurumov-et-al.-Final.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Sultanbayeva, G.; Gorbunova, A.; Lozhnikova, O. Research, Analysis and Assessment of Public Demand for Reliable Information during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ser. Zhurnalistiki 2022, 63(1), 4–15.

- Urpekova, A. Freymy Regional’nykh Media ob Antikovidnykh Merakh vo Vremya Pandemii COVID-19 (na Primere Atyrauskoy i Pavlodarskoy Oblastey) [Regional Media Frames about Anti-COVID Measures during the COVID-19 Pandemic (on the Example of Atyrau and Pavlodar Regions)]. In Kazakhstan and COVID-19: Media, Culture, Politics; Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2021; pp. 70–83.

- Akhunov, A. Pandemiya COVID-19 kak Vyzov dlya Postsovetskikh Stran Tsentral’noy Azii [The COVID-19 Pandemic as a Challenge for the Post-Soviet Countries of Central Asia]. Int. Analit. 2020, 11(1), 114–128. Available online: https://www.interanalytics.org/jour/article/view/270 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Permanent Representation of the Republic of Armenia to the Council of Europe. Note Verbale to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe. Council of Europe, Strasbourg, France, 2020; Ref. No. JJ9015C, Tr./005-227. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16809cf885 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Aliyev, Kh. An Explorative Analysis of Azerbaijan’s COVID-19 Policy Response and Public Opinion. Caucasus Surv. 2021, 9(3), 257–274. [CrossRef]

- Unlu, S.; Yaşar, L.; Bilici, E. The COVID-19 Normalization Process for Turkish Nations in Terms of Health Communications: The Case of Türkiye, Azerbaijan, and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. İnsan ve Toplum 2022, 12(4), 137–154.

- Ministry of Healthcare of Kazakhstan. Regulation of the Public Relations Department of the Ministry of Healthcare of Kazakhstan. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/dsm/documents/details/838890?lang=ru (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Committee for Sanitary and Epidemiological Control of the Ministry of Healthcare of Kazakhstan. Regulation of the Public Relations Department. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/ksek/about/structure/departments/position/5537/1?lang=ru (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Bukharbayeva, A.; Zhussupov, B.; Alekesheva, L.; Erdenova, M.; Iskakova, B.; Myrkassymova, A.; Mergenova, G. Assessing the Trust of the Population of Kazakhstan in Sources of Information during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nauka Zdravookhran. 2022, 24(2), 15–23.

- Kofanov, D.; Kozlov, V.; Libman, A.; Zakharov, N. Encouraged to Cheat? Federal Incentives and Career Concerns at the Sub-National Level as Determinants of Under-Reporting of COVID-19 Mortality in Russia. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 2023, 53(3), 835–860. [CrossRef]

- Kilani, A.; Georgiou, G. Countries with Potential Data Misreport Based on Benford’s Law. J. Public Health 2021, 43(2), e295–e296. [CrossRef]

- Karlinsky, A.; Kobak, D. Tracking Excess Mortality across Countries during the COVID-19 Pandemic with the World Mortality Dataset. eLife 2021, 10, e69336. [CrossRef]

- Lemon, E.; Antonov, O. Responses to COVID-19 and the Strengthening of Authoritarian Governance in Central Asia. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Central Asia, Central Asia Program, CAP Paper No. 236, 2021. Available online: https://centralasiaprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/CAP-Paper-236-Edward-Lemon-1.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Ivanova, P.; Osborn, A. Coronavirus Forces Putin Critics to Scale Back Protests before Big Vote. Reuters, 2 June 2020. Available online: https://jp.reuters.com/article/instant-article/idUSKBN217256/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Reuters. Hundreds Protest in Moscow against Reforms That May Keep Putin in Power. Reuters, 19 July 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/world/hundreds-protest-in-moscow-against-reforms-that-may-keep-putin-in-power-idUSKCN24G2SE/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Mediazona. V Peterburge na Piketchike s Plakatom «Davayte Zhivite Druzhno» Byli Zapolneny Protokol Narusheniya Kovidnykh Ogranicheniy [In St. Petersburg, a Picketer with a Poster Reading “Let’s Live in Peace” Was Charged with Violating COVID Restrictions]. Mediazona, 19 March 2023. Available online: https://zona.media/news/2023/03/19/leopold (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Davies, K.; Litvinova, D. Putin Foe Alexei Navalny Is Buried in Moscow as Thousands Attend under a Heavy Police Presence. Associated Press News, 2 March 2024. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/russia-alexei-navalny-funeral-9263c4d0688b883fa9f853f5d0310e45 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Polyakova, N.V. K Voprosu o Roli «Kovidnogo» Faktora Prezidentskoy Kampanii-2020 v Belorussii [On the Role of the “COVID” Factor in the 2020 Presidential Campaign in Belarus]. In Political Representation and Public Authority: Transformational Challenges and Prospects; 2020; pp. 419–420. Available online: https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=44723176 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Schatz, E. The Soft Authoritarian Tool Kit: Agenda-Setting Power in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Comp. Politics 2009, 41(2), 203–222.

- Foa, R.S. Modernization and Authoritarianism. J. Democr. 2018, 29(3), 129–140.

- Lemon, E. Mirziyoyev’s Uzbekistan: Democratization or Authoritarian Upgrading? Foreign Policy Research Institute—Central Asia Papers; 2019. Available online: https://www.fpri.org/article/2019/06/mirziyoyevs-uzbekistan-democratization-or-authoritarian-upgrading/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Rechel, C.; Janenova, S.; Ha, H. Social Injustice in Consolidated Authoritarian Regimes: Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Social Justice in a Turbulent Era; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 24–46.

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Kazakh Civil Rights Activists under Pressure amid Coronavirus Spread. RFE/RL, 8 April 2020. Available online: https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakhstan-kazakh-activists-coronavirus-human-rights-economy/30542645.html (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Barseghyan, A.; Grigoryan, L.; Pambukchyan, A.; Papyan, A.; Aghekyan, E. Disinformation and Misinformation in Armenia: Confronting the Power of False Narratives. Freedom House, June 2021. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2021/disinformation-and-misinformation-armenia (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Human Rights Watch. Azerbaijan: Crackdown on Critics amid Pandemic. Stop Abusing Restrictions to Retaliate against Opposition. Human Rights Watch News Release, 16 April 2020. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/16/azerbaijan-crackdown-critics-amid-pandemic (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Popov, D. COVID-19: The Split of Public Opinion and State Policy in Russia. Russ. J. Soc. Res. 2021, 2(3), 6–19. Available online: https://scholar.archive.org/work/g2qb3kazgvgrxnql7jwmbhxjiq/access/wayback/https://rusus.jes.su/index.php?dispatch=products.print_publication&product_id=92596&format=pdf&version_id=90907 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Kotseva, B.; Vianini, I.; Nikolaidis, N.; Faggiani, N.; Potapova, K.; Gasparro, C.; Linge, J.P. Trend analysis of COVID-19 mis/disinformation narratives—A 3-year study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291423. [CrossRef]

- Golunov, S.; Smirnova, V. Russian border controls in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: Social, political, and economic implications. Probl. Post-Communism 2022, 69, 71–82. [CrossRef]

- Nossem, E. The pandemic of nationalism and the nationalism of pandemics. UniGR-CBS Working Paper 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Bursztyn, L.; Rao, A.; Roth, C.; Yanagizawa-Drott, D. Misinformation during a pandemic; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; NBER Working Paper No. 27417. [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, K.; Albarracín, D. The relation between media consumption and misinformation at the outset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in the US. HKS Misinformation Review 2020, 1. [CrossRef]

- Freelon, D.; Wells, C. Disinformation as political communication. Political Commun. 2020, 37, 145–156. [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C.; Derakhshan, H. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy-Making; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2017.

- Nisbet, E.; Kamenchuk, O. Russian news media, digital media, informational learned helplessness, and belief in COVID-19 misinformation. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2021, 33, 571–590. [CrossRef]

- Stoycheff, E.; Nisbet, E.C.; Epstein, D. Differential effects of capital-enhancing and recreational Internet use on citizens’ demand for democracy. Commun. Res. 2020, 47, 1034–1055. [CrossRef]

- Stoycheff, E.; Nisbet, E. What’s the bandwidth for democracy? Deconstructing Internet penetration and citizen attitudes about governance. Political Commun. 2014, 31, 628–646. [CrossRef]

- Moscadelli, A.; Albora, G.; Biamonte, M.A.; Giorgetti, D.; Innocenzio, M.; Paoli, S.; Bonaccorsi, G. Fake news and COVID-19 in Italy: Results of a quantitative observational study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5850. [CrossRef]

- Loomba, S.; de Figueiredo, A.; Piatek, S.; de Graaf, K.; Larson, H. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 337–348. [CrossRef]

- Kisa, S.; Kisa, A. A comprehensive analysis of COVID-19 misinformation, public health impacts, and communication strategies: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e56931. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.; Fellow, J. Conveying truth: Independent media in Putin’s Russia. Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy 2020. Available online: https://shorensteincenter.org/independent-media-in-putins-russia (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Sukhankin, S. COVID-19 as a tool of information confrontation: Russia’s approach. Sch. Public Policy Publ. 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Tulchinskii, G. The dynamics of public discourse during the coronavirus pandemic: A request for responsibility. Russ. J. Commun. 2020, 12, 193–214. [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. Post-COVID-19 Central Asia and the Sino-American geopolitical competition. Central Asia Program Papers 2021, 241. Available online: https://centralasiaprogram.org/archive/central-asia-research-paper/post-covid-19-central-asia-and-the-sino-american-geopolitical-competition (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Dzhalilov, A.; Bannikov, P.; Smakov, D.; Bocharova, M.; Abdilda, Zh.; Yesimkhanov, M.; Tleukhan, Zh. Dissemination of disinformation about vaccination in Kazakhstan in 2020–2021; UNICEF: Kazakhstan, 2022. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/kazakhstan/en/reports/dissemination-disinformation-about-vaccination-kazakhstan-2020-2021 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Yaylymova, A. COVID-19 in Turkmenistan: No data, no health rights. Health Hum. Rights 2020, 22, 325.

- Lewis, S. This Central Asian Country Will Reportedly Arrest You for Saying the Word “Coronavirus”. CBS News 2020. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/coronavirus-turkmenistan-bans-word-coronavirus-arrest (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- The Statesman. Turkmenistan Bans the Word “Coronavirus”, Wearing of Masks, in a Major Censorship Move. The Statesman 2020, 1 April. Available online: https://www.thestatesman.com/world/turkmenistan-bans-the-word-coronavirus-wearing-of-masks-in-a-major-censorship-move-1502872551.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Hashim, H.T.; El Rassoul, A.E.A.; Bchara, J.; Ahmadi, A.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E., III. COVID-19 denial in Turkmenistan veiling the real situation. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 8. [CrossRef]

- Eurasianet. Tajikistan Strains Credibility with Apparent COVID-19 Turnaround. Eurasianet 2020, 22 May. Available online: https://eurasianet.org/tajikistan-strains-credibility-with-apparent-covid-19-turnaround (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Boboyorov, H. The Authoritarian Treatment of the COVID-19: The Case of Tajikistan. In COVID-19 Pandemic and Central Asia. Crisis Management, Economic Impact, and Social Transformations; Laruelle, M., Ed.; Central Asia Program, The George Washington University: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 91–99. Available online: https://www.centralasiaprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Laruelle-ed-Covid-and-Central-Asia-2021-Final-1.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ghaddar, A.; Khandaqji, S.; Awad, Z.; Kansoun, R. Conspiracy beliefs and vaccination intent for COVID-19 in an infodemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261559. [CrossRef]

- Agley, J.; Xiao, Y.; Thompson, E.E.; Chen, X.; Golzarri-Arroyo, L. Intervening on trust in science to reduce belief in COVID-19 misinformation and increase COVID-19 preventive behavioral intentions: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e32425. [CrossRef]

- Agley, J. Assessing changes in US public trust in science amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health 2020, 183, 122–125. [CrossRef]

- Devine, D.; Gaskell, J.; Jennings, W.; Stoker, G. Trust and the coronavirus pandemic: What are the consequences of and for trust? An early review of the literature. Political Stud. Rev. 2021, 19, 274–285. [CrossRef]

- Hyland-Wood, B.; Gardner, J.; Leask, J.; Ecker, U. Toward effective government communication strategies in the era of COVID-19. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 30. [CrossRef]

- Bruley, J.; Mamadiiarov, I. Kyrgyzstan: The socioeconomic consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. Central Asia Program (CAP) Papers 2020, 244, 1–15.

- Nair, B.; Janenova, S.; Serikbayeva, B. A Primer on Policy Communication in Kazakhstan; 1st ed.; Palgrave MacMillan: Singapore, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.; Asuncion, X. Toward an improved risk/crisis communication in this time of COVID-19 pandemic: A baseline study for Philippine local government units. J. Sci. Commun. 2020, 19, A09. [CrossRef]

- Volkovskii, D.; Filatova, O. Social media and deliberation in the period of COVID-19 crisis: Transforming political interaction between citizens and Russian authorities in the digital sphere. In Proceedings of the Conference on Digital Government Research (DGO 2025); 2025; Volume 1. Available online: https://proceedings.open.tudelft.nl/DGO2025/article/view/988 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Graefen, B.; Hasanli, S.; Jabrayilov, A.; Alakbarova, G.; Tahmazi, K.; Gurbanova, J.; Fazal, N. Instagram as a health education tool: Evaluating the efficacy and quality of medical content on Instagram in Azerbaijan. medRxiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vikhrov, I.; Azimova, N.; Ashirbaev, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Koustuv, D. The role of social messaging in the health promotion against COVID-19 in Uzbekistan. Interdiscip. Approaches Med. 2021, 2, 3–9.

- Kydyrbaev, O. Obraz sil’nogo sotsial’nogo gosudarstva v media [The image of a strong social state in the media]. In Kazakhstan and COVID-19: Media, Culture, Politics; Friedrich Ebert Foundation Representative Office in Kazakhstan: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2021; pp. 31–46. Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/kasachstan/18218.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Haruna, U.; Amos, O.; Gyeltshen, D.; Colet, P.; Almazan, J.; Ahmadi, A.; Sarria-Santamera, A. Towards a post-COVID world: Challenges and progress of recovery in Kazakhstan. Public Health Chall. 2022, 1, e17. [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.; Covello, V.; McCallum, D. The determinants of trust and credibility in environmental risk communication: An empirical study. Risk Anal. 1997, 17, 43–54. [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Gignac, G.E.; Vaughan, S. The pivotal role of perceived scientific consensus in acceptance of science. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 399–404. [CrossRef]

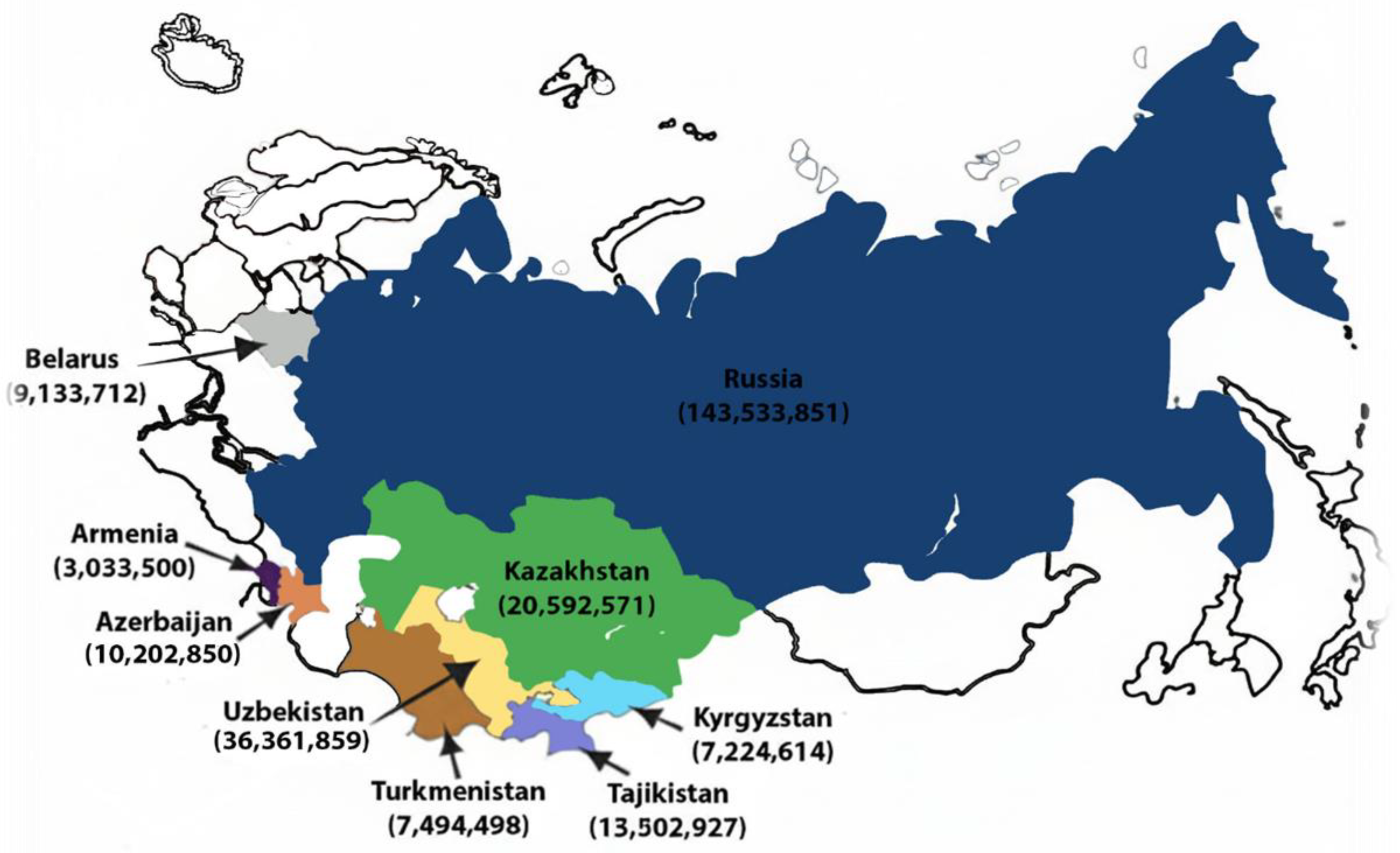

- World Bank. Open Data. Population. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- World Bank. World Development Indicators; Current Health Expenditure. World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 7 August 2025).

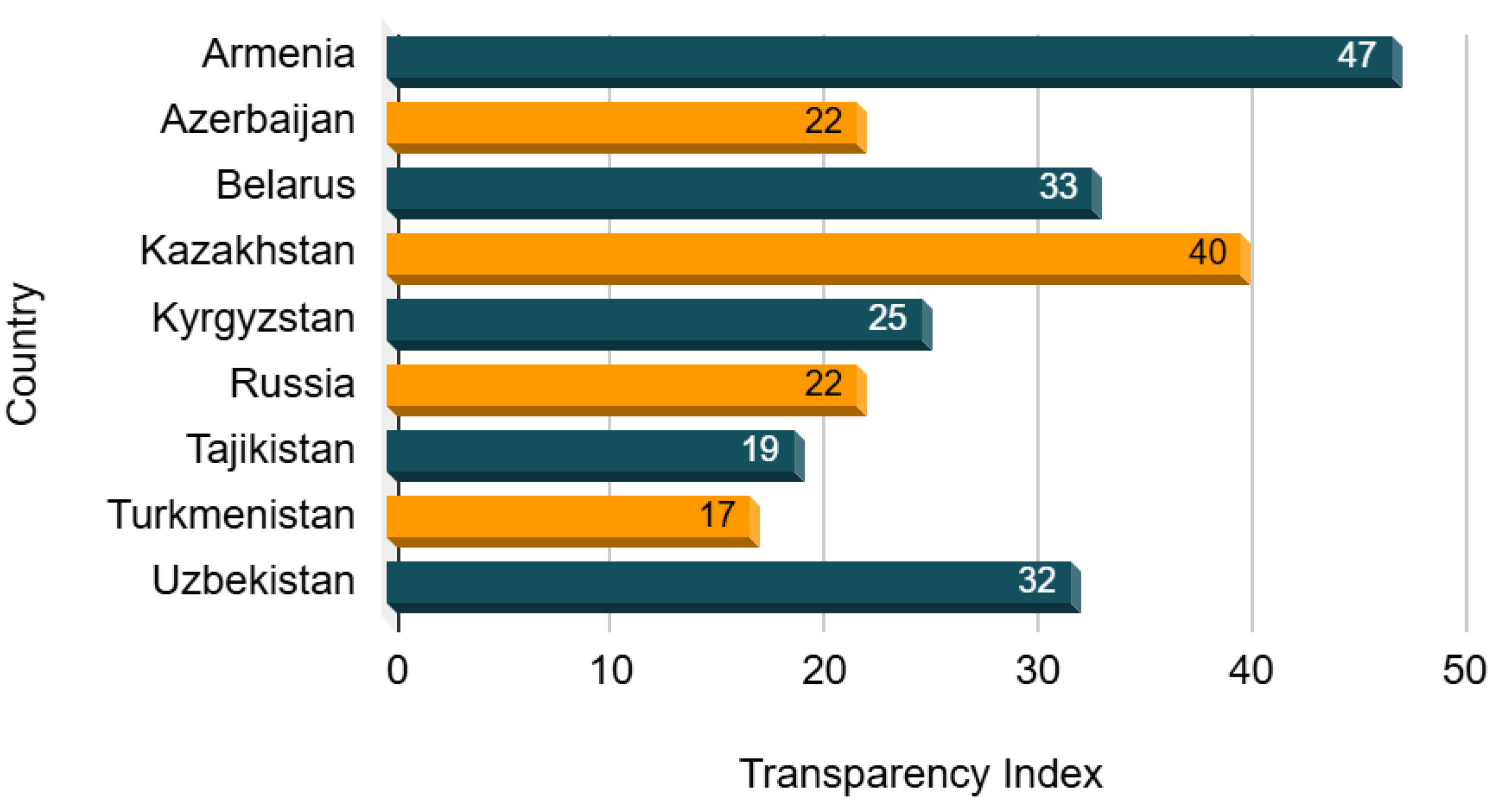

- Transparency International. Corruption Perception Index. Transparency International: Berlin, Germany, 2024. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/countries (accessed on 21 September 2025).

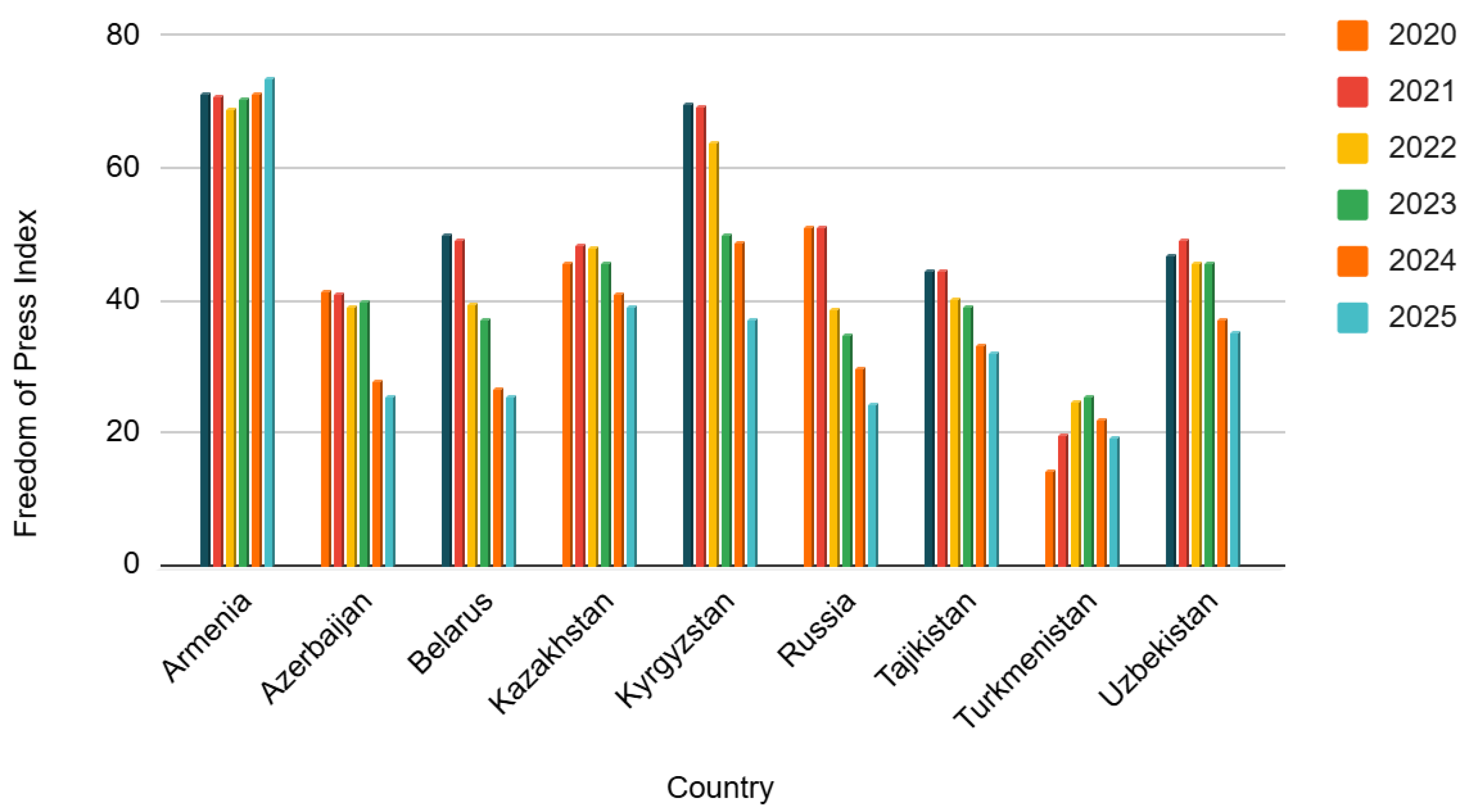

- Reporters without Borders. Freedom of Press Index. Reporters Without Borders: Paris, France, 2025. Available online: https://rsf.org/en/index?year= (accessed on 27 September 2025).

| Countries | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Armenia | 12.24 | 12.32 | 9.96 |

| Azerbaijan | 5.85 | 4.89 | 3.98 |

| Belarus | 6.41 | 6.57 | 6.56 |

| Kazakhstan | 3.75 | 3.92 | 3.74 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 4.95 | 5.35 | 4.92 |

| Russia | 8.04 | 6.98 | 6.92 |

| Tajikistan | 8.89 | 8.38 | 7.63 |

| Turkmenistan | 5.57 | 5.49 | 5.37 |

| Uzbekistan | 6.71 | 7.70 | 7.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).