Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

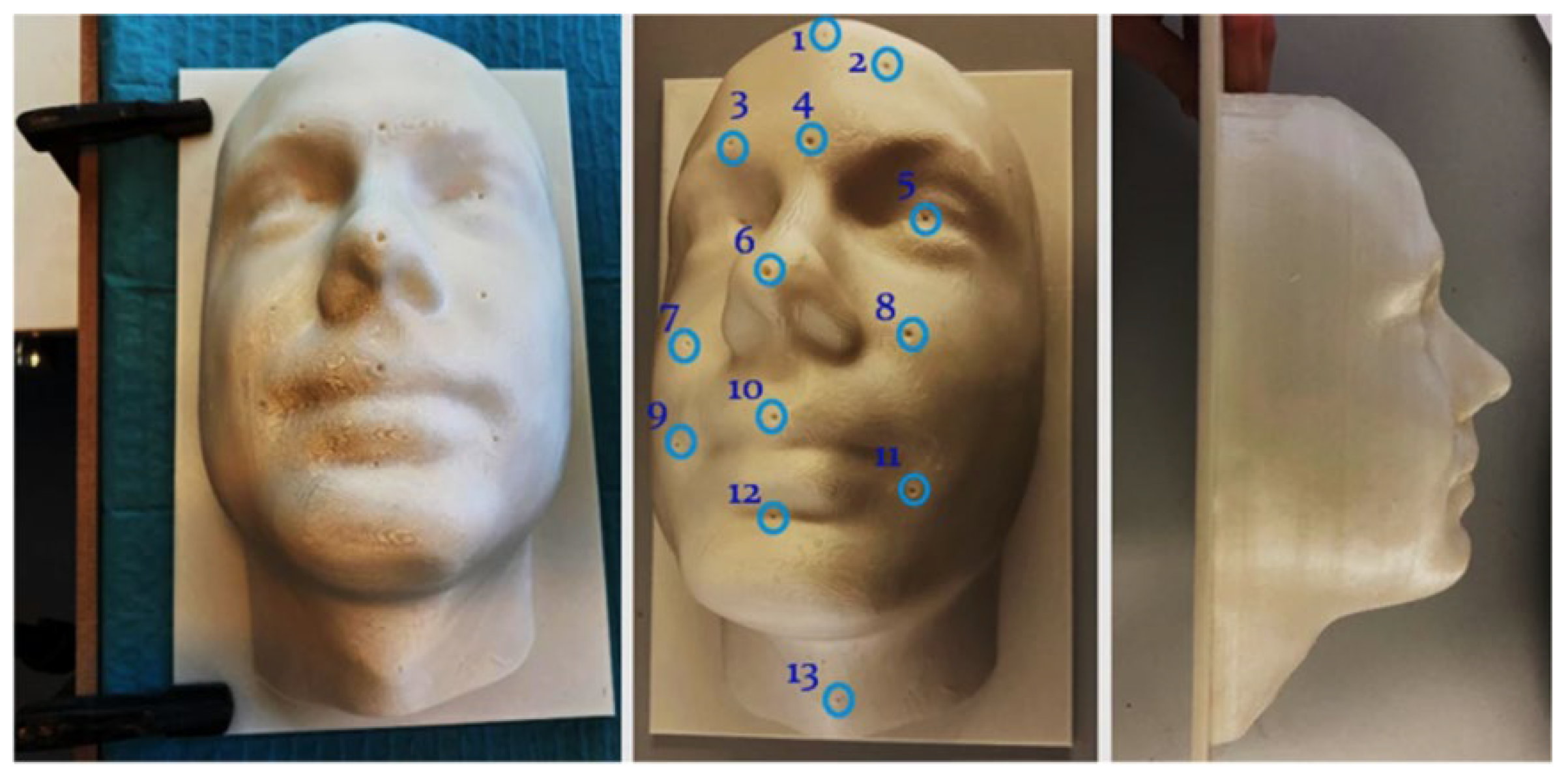

2.1. Sample and Study Area Description

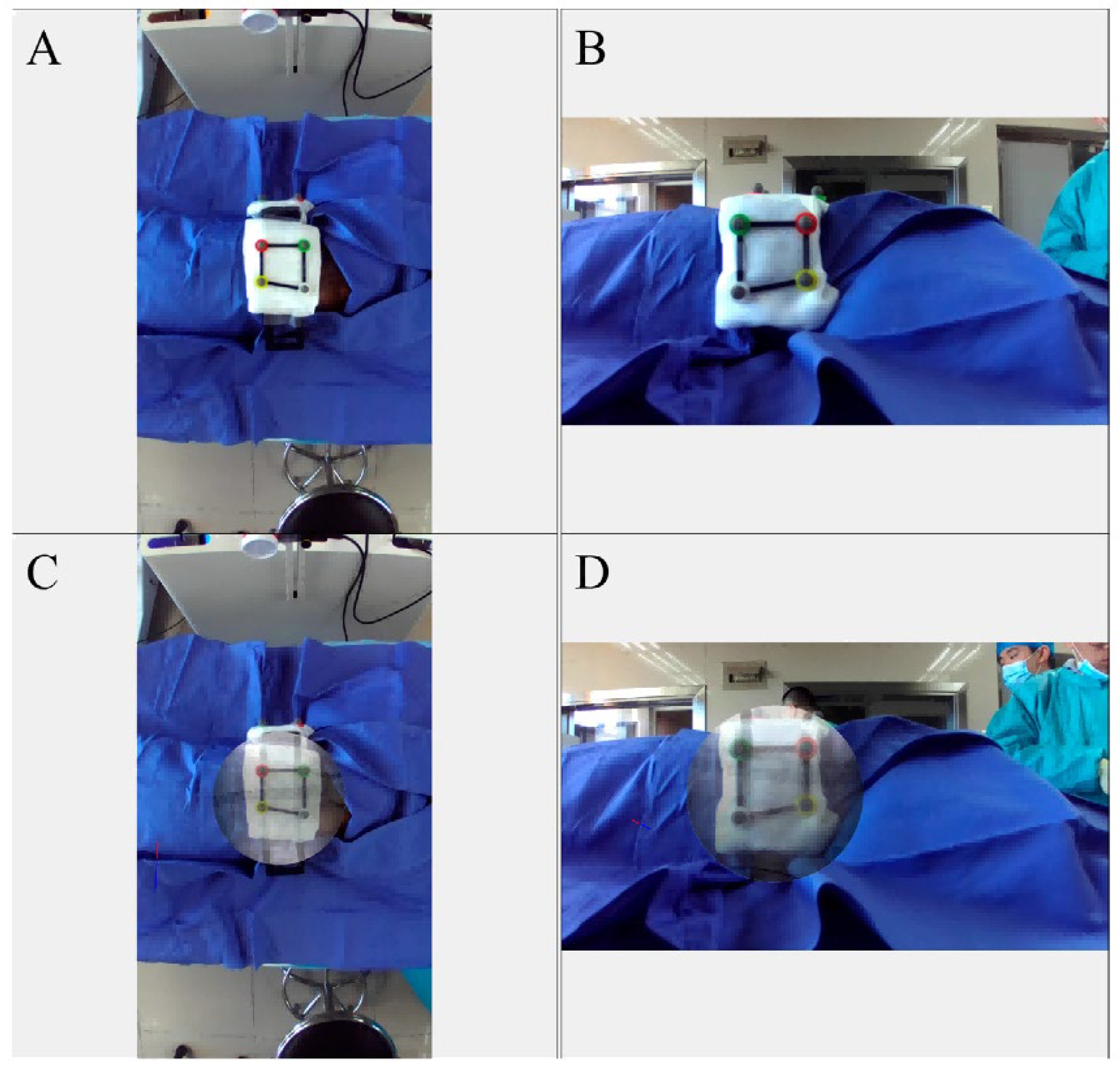

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Group

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Model Formulas

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Comparison of Registration Accuracy (TRE)

3.2. Setup Time and Usability

3.3. Regression and Correlation of TRE vs. Setup Time

3.4. Limitations, Implications, and Comparison with Prior Work

4. Conclusion

References

- Wu, C., Chen, H., Zhu, J., & Yao, Y. (2025). Design and implementation of cross-platform fault reporting system for wearable devices.

- Xu, J. (2025). Building a Structured Reasoning AI Model for Legal Judgment in Telehealth Systems.

- Fazel, A., McGee, W., & von Buelow, P. Dual-Angle Augmented Reality Method for Manual Timber Fastening. Available at SSRN 5200112.

- Wang, Y., Wen, Y., Wu, X., & Cai, H. (2024). Application of Ultrasonic Treatment to Enhance Antioxidant Activity in Leafy Vegetables. International Journal of Advance in Applied Science Research, 3, 49-58.

- Liu, J., Huang, T., Xiong, H., Huang, J., Zhou, J., Jiang, H.,... & Dou, D. (2020). Analysis of collective response reveals that covid-19-related activities start from the end of 2019 in mainland china. medRxiv, 2020-10.

- Zhang, F., Paffenroth, R. C., & Worth, D. (2024). Non-Linear Matrix Completion. Journal of Data Analysis and Information Processing, 12(1), 115-137.

- Xu, J. (2025). Semantic Representation of Fuzzy Ethical Boundaries in AI.

- Yang, Y., Leuze, C., Hargreaves, B., Daniel, B., & Baik, F. (2025). EasyREG: Easy Depth-Based Markerless Registration and Tracking using Augmented Reality Device for Surgical Guidance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.09498.

- Li, C., Yuan, M., Han, Z., Faircloth, B., Anderson, J. S., King, N., & Stuart-Smith, R. (2022). Smart branching. In Hybrids and Haecceities-Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference of the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture, ACADIA 2022 (pp. 90-97). ACADIA.

- Tian, J., Lu, J., Wang, M., Li, H., & Xu, H. (2025). Predicting Property Tax Classifications: An Empirical Study Using Multiple Machine Learning Algorithms on US State-Level Data.

- Yuan, M., Wang, B., Su, S., & Qin, W. (2025). Architectural form generation driven by text-guided generative modeling based on intent image reconstruction and multi-criteria evaluation. Authorea Preprints.

- Chen, F., Li, S., Liang, H., Xu, P., & Yue, L. (2025). Optimization Study of Thermal Management of Domestic SiC Power Semiconductor Based on Improved Genetic Algorithm.

- Sun, X., Wei, D., Liu, C., & Wang, T. (2025, June). Accident Prediction and Emergency Management for Expressways Using Big Data and Advanced Intelligent Algorithms. In 2025 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Image Processing and Computer Applications (ICIPCA) (pp. 1925-1929). IEEE.

- Yang, J. (2024). Application of Business Information Management in Cross-border Real Estate Project Management. International Journal of Social Sciences and Public Administration, 3(2), 204-213.Li, Z. Y., Li, J. H., Yang, J. F., Li, Y., & He, J. R. (2017). Validation of Fuel and Emission Calculator model for fuel consumption estimation. Advances in Transportation Studies, 1.

- Yuan, T., Zhang, X., & Chen, X. (2025). Machine Learning based Enterprise Financial Audit Framework and High Risk Identification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.06266.

- Guo, L., Wu, Y., Zhao, J., Yang, Z., Tian, Z., Yin, Y., & Dong, S. (2025, May). Rice Disease Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8n. In 2025 6th International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning (CVIDL) (pp. 123-132). IEEE.

- Xu, K., Wu, Q., Lu, Y., Zheng, Y., Li, W., Tang, X., ... & Sun, X. (2025, April). Meatrd: Multimodal anomalous tissue region detection enhanced with spatial transcriptomics. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 39, No. 12, pp. 12918-12926).

- Chen, H., Li, J., Ma, X., & Mao, Y. (2025). Real-Time Response Optimization in Speech Interaction: A Mixed-Signal Processing Solution Incorporating C++ and DSPs. Available at SSRN 5343716.

- Ahmad, F., Xiong, J., & Xia, Z. (2024). Automatic feature-based markerless calibration and navigation method for augmented reality assisted dental treatment. IET Cyber-Systems and Robotics, 6(4), e70003.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).