1. Introduction

Singularities in light wave fields may affect the intensity, the phase and the polarization [

1,

2]. Intensity singularities are probably the least studied. They appear naturally in ray optics as caustics [

3], but they are supposed to dissolve in the wave description of light. Even so, there still exist wave fields with diverging intensity, which are thus disregarded as unphysical or mathematical artifacts of an approximate model. A well-known example is self-focusing and collapse in cubic Kerr nonlinear media, where a regular wave develops spontaneously a singularity. The singularity in fact disappears when the effect of higher-order nonlinearities [

4], or of nonparaxial propagation are accounted for [

5]. The relevance of the singularity in the approximate model, however, should not be underestimated. It is its existence that pushes the model to its limits, demanding a more precise model where the intensity remains finite and new phenomena appear; in self-focusing, those involved in light filamentation —ionization, self-defocusing, spectral broadening, etc.

The example studied here is the development of an intensity singularity in

linear focusing of the so-called exploding or concentrating paraxial light beams. They were first described with Cartesian geometry [

6], and later with cylindrical symmetry and incorporating vortices and cylindrical vector exploding beams with radial/azimuthal polarization [

7]. Recently, the idea has been extended to exploding wave packets with spatio-temporal spherical symmetry [

8].

Ideal focusing consists of introducing a convergent spherical wavefront, represented in the paraxial approximation by a negative quadratic phase. When doing so to the exploding beam profile, a singularity is produced at the focus, in sharp contrast with standard beams, e.g. Gaussian-type beams, and imitating focusing an ideal plane to a spherical wave. However, exploding beams form the singularity with finite power. They are shaped such that the radial tails decay sufficiently fast for the power to be finite, but sufficiently slow for them to constantly supply light to the focus regardless of the radial distance from the lens center, and forming the singularity. This seems a mathematical artifact of the paraxial approximation since, from a certain radial distance, light rays are not focused at small angles.

Nevertheless, while focusing remains paraxial by blocking nonparaxial focusing light with an aperture, the existence of the singularity in ideal focusing with infinite aperture produces a physically observable effect, absent with standardlight beams. When focusing, e.g., a Gaussian beam, the radius of the aperture becomes irrelevant once it is a few times the Gaussian beam spot size. In contrast, when focusing the exploding beam, the focal intensity increases and the focal spot concentrates with increasing aperture as these properties approach those of focusing with infinite aperture radius. This is the concentrating or exploding effect that has been demonstrated experimentally with Cartesian geometry [

9], and for exploding vortex beams with cylindrical symmetry [

10].

In this paper, we leave aside the paraxial approximation and introduce a nonparaxial treatment that considers the electromagnetic nature of light. We find that the singularity disappears in the limit of unit numerical aperture NA, equivalent to infinite aperture. Yet, as a physical reminiscence of the paraxial singularity, the exploding or concentrating behaviour continues to work, i.e., the focal intensity increases continuously and the spot size continuously diminishes with increasing NA up to NA. This result maintains in nonparaxial focusing the most relevant property of exploding beams: A continuous and monotonous control of the peak intensity and resolution with the aperture radius using a single beam. Thus, the exploding beams mimics with a finite amount of power the focusing properties of an ideal plane wave.

Among all variants of exploding beams, we focus here on the most interesting case of radially and azimuthally polarized exploding beams due to the numerous applications, and pay particular emphasis on the comparison with radially and azimuthally polarized vector beams with standard profiles, such as Laguerre-Gauss profiles and flat-top profiles.

2. Paraxial Exploding Vortex Beam

Let us first recall the basic properties of the exploding beam in a semi-scalar approach valid for paraxial focusing. We consider a slowly varying, complex envelope

of a monochromatic light beam

, where

are polar coordinates at a transversal plane, the integer

s is the vortex topological charge, and the unit vector

specifies the polarization state. The exploding beam is characterized by the transversal profile

with revolution symmetry. The parameter

scales the exploding profile to the desired size, and

is a radial decay parameter. If

then the power is finite. Choosing

, with

c the speed of light and

the permittivity in vacuum,

has units of electric field (V/m), and

P coincides with the beam power in watts. The focused profile

at the focal plane of an ideal lens of focal length

f is provided by the Fresnel diffraction integral. For a cylindrically symmetric beam with a vortex of charge

s, Fresnel integral for propagation up to the focal plane takes the form [

7]

where

k is the propagation constant, and

is the first kind Bessel function of order

n. Ignoring lens aperture effects (

), the focal profile has an intensity singularity if

. Thus, the condition

for

ensures physical realizability (finite power) and a singularity at the focal plane. For

—the case of interest here—, the focused field features an infinitely intense and narrow ring of light surrounding a punctual vortex of zero intensity.

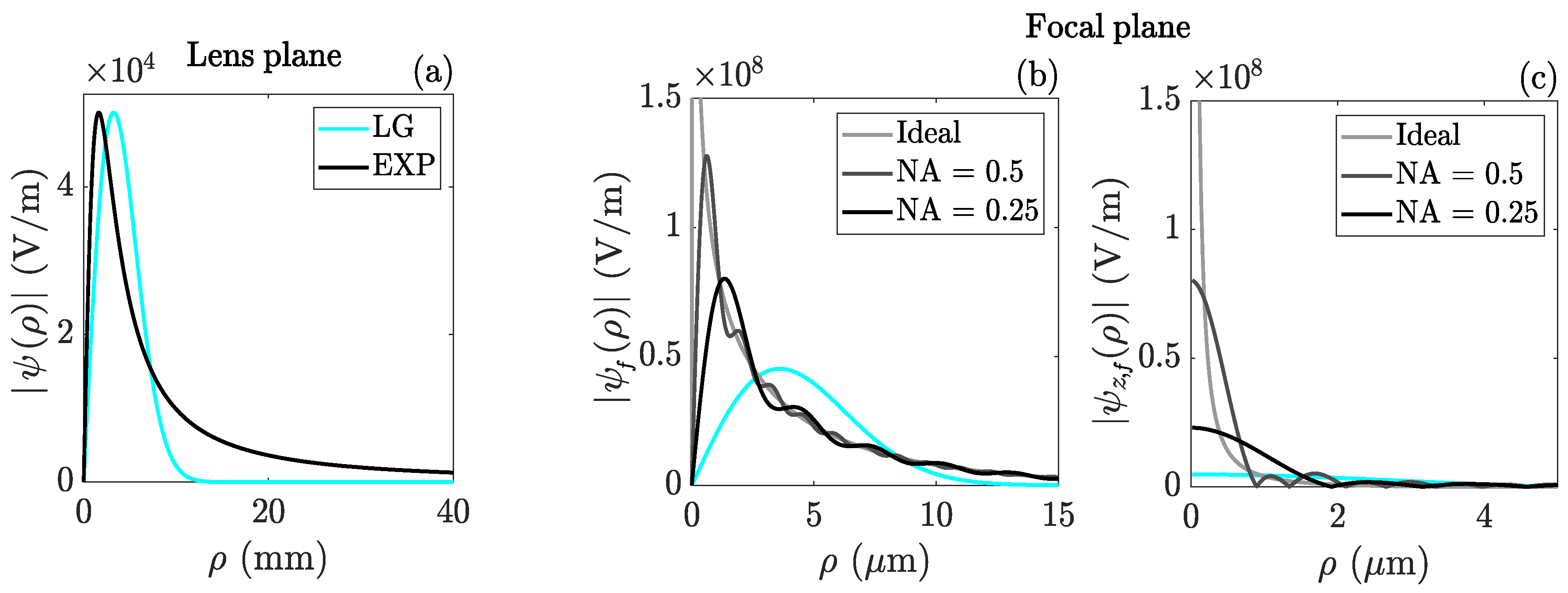

Figure 1(a) and (b) illustrate with an example the exploding beam at the lens,

, and at the focal plane,

.

One can construct left- and right-handed circularly polarized exploding beams with these transversal profiles taking

, where

. Further, radially and azimuthally polarized focused exploding beams can be constructed by superposing left-handed circularly polarized exploding vortex beams with

and a right-handed circularly polarized exploding vortex beam with topological charge

[

7], namely,

where

are radial and azimuthal unit vectors in the transversal plane.

In addition, Gauss’s divergence in free space imposes the existence of an associated axial component, small in paraxial focusing, given in this regime by

[

11], where

is the transverse divergence operator. For the radially and azimuthally focused fields in Equation (

4), the axial components are [

7]

The axial component is singular at

for ideal focusing with

when polarization is radial, as seen in

Figure 1(c).

This singular behaviour is the origin of the exploding effect in real situations with finite aperture. With increasing aperture radius, or numerical aperture NA

, the transversal and axial components approach the respective singularities in ever more intense and narrower intensity profiles, as illustrated in

Figure 1(b) and (c) for increasing NA. The exploding effect allows us to exert continuous control over peak intensity and resolution with a single beam. This is impossible with a radially polarized beam with LG profile. The focused radially polarized LG beam of the same power and peak intensity on the lens as the exploding beam (for a proper comparison) in

Figure 1(a, blue curve) is less focused and does not experience any change once its main ring is well inside the aperture, as in

Figure 1(b,c, blue curves) for the radial and axial components.

For comparison with the results of a nonparaxial, full electromagnetic model, we can construct paraxial electromagnetic fields. Given the symmetry of Maxwell equations in free space, we can identify the radially polarized

and

with the electric field or with the magnetic field. With the electric field,

where

c is the velocity of light in free space. The radially polarized electric field

, the magnetic field

and the propagation direction

z form a right-handed triad. With the magnetic field,

The azimuthally polarized electric field

,

and

z also form a right-handed triad. The electromagnetic field of with radial polarization (of the electric field) at the lens and at the focal plane is conceptually illustrated in

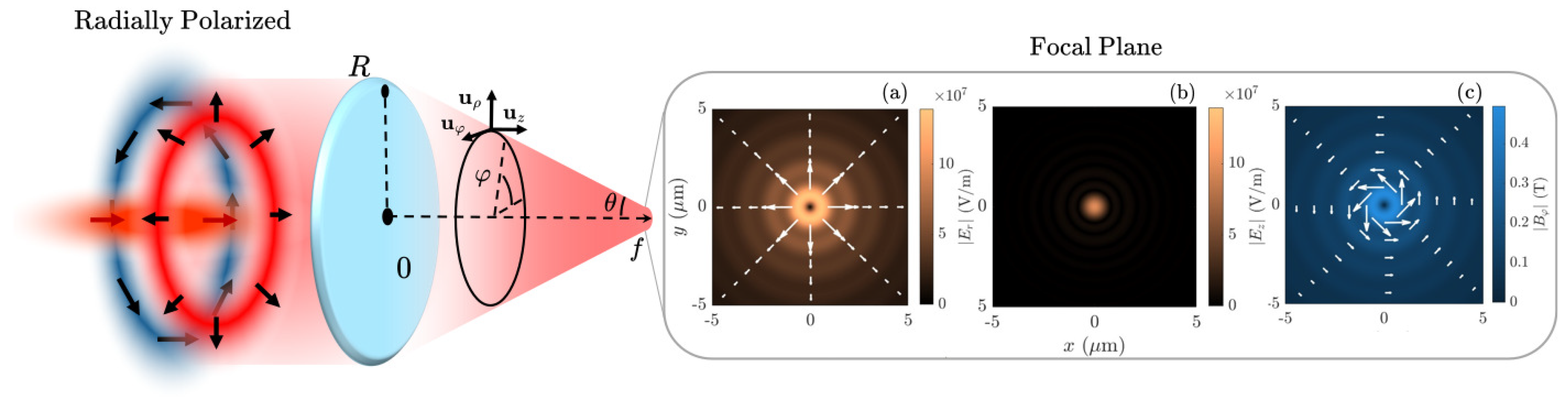

Figure 2.

3. Tightly Focused Exploding Cylindrical Vector Beams

The singular behaviour and the associated exploding effect may be an artifact of the paraxial approximation as this approximation does not describe adequately focusing with large numerical apertures, say NA

, equivalent to 30 degrees for a marginal ray. For nonparaxial focusing, a full vectorial treatment is necessary. We make use of Richard-Wolf’s theory applied to tightly focusing of radially and azimuthally polarized light. For radial polarization, the non-vanishing components of the electromagnetic field at the focal plane are given by [

12]

and for azimuthal polarization, by [

12]

In the above formulas,

is the maximum angle of incidence of the illumination seen from the focus, related to the numerical aperture by NA

.

is the pupil function, which is obtained by replacing

in the exploding profile

in Equation (

1) by

when adopting the Helmholtz focusing condition [

12], and multiplying by the obliquity factor

under this focusing condition [

12], i.e.,

. An example of focused exploding beam with nonparaxial NA

is depicted in

Figure 2(a-c). For radial electric field polarization (a) and (b) represent the amplitudes of the radial and axial components, and (c) the azimuthal magnetic field. By symmetry of the Equations (

8) and (

9), for azimuthal electric field polarization, (c) represents the azimuthal electric field, and (a) and (b) the radial and axial components of the magnetic field. Strong focusing with high NA results in sub-wavelength focused spots, with peak amplitudes of the order of

V/m, and magnetic fields of the order of the Tesla.

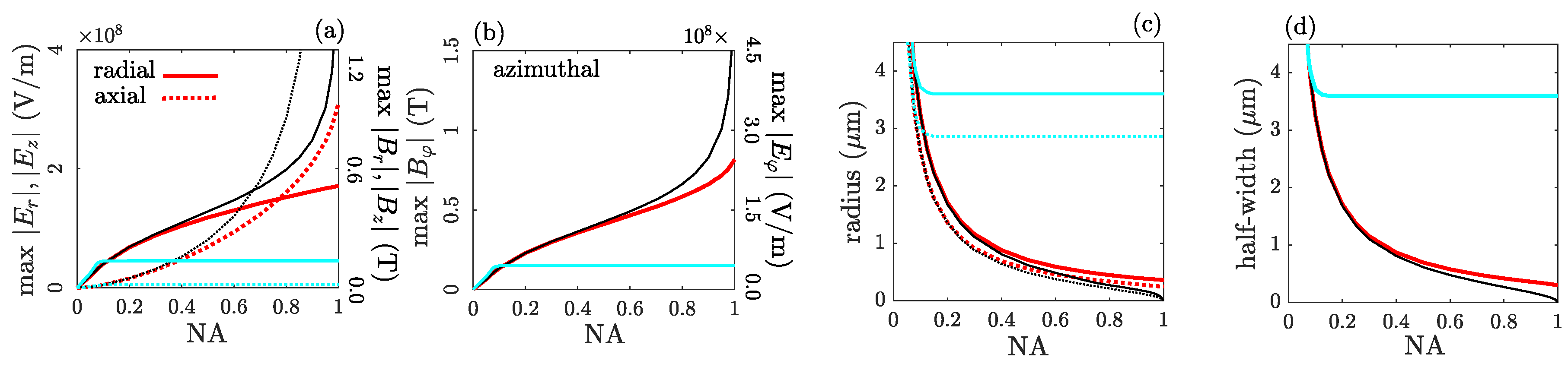

Figure 3 (red curves) illustrates, with the left vertical axes, the behaviour of (a,b) the maximum values, and (c, d) the beam radii of

,

and

at the focal plane for radial polarization, as functions of NA, numerically evaluated from Equation (

8). By symmetry of Equations (

8) and (

9),

Figure 3 also shows, with the right vertical axes, the same quantities for

,

and

for azimuthal polarization. For

(

) and

(

), the beam radius is taken as the radius of their bright rings, and for

(

), the radius of

-decay of its central maximum. The paraxial predictions (black curves), with amplitudes approaching infinity and radii approaching zero when NA

, cease to be valid about NA

. Actually, no singularities are formed when NA

, equivalent to infinite aperture, and no zero radius is reached, in either the radial, axial or azimuthal components, but they reach finite values. The singularities in exploding light beams are indeed an artifact of the paraxial approximation. However, the exploding or concentrating behaviour, i.e., peak amplitudes that increase monotonously, and radii that monotonously decrease with NA

, continues to exist, particularly in the axial component as the light from the tails of the exploding profile comes from angles approaching 90 degrees. Of course, no change is observed in the LG beam of the same power and peak intensity on the lens (blue curves) once the aperture completely incorporates its main lobe (NA

), which prevents from any control of the features of the focused field.

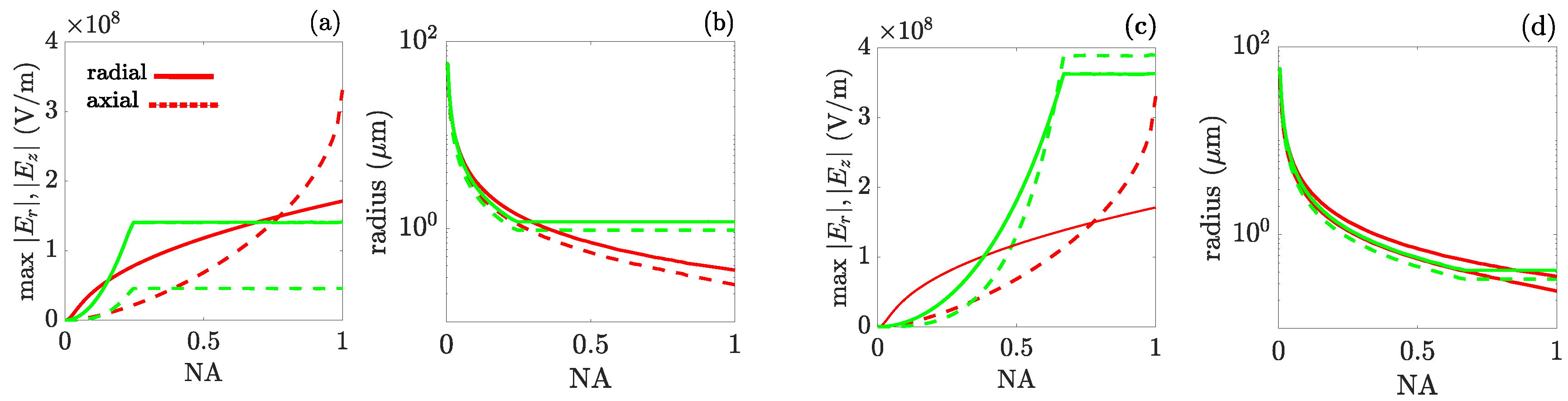

4. Comparison with Cylindrical Vector Beams of Uniform Amplitude

Thus, the exploding beam reproduces with a finite amount of power the concentrating behaviour that would also take place when focusing an ideal plane wave of infinite power. Since these idealized waves do not exist, we proceed to a fairer comparison between the focusing capabilities of the exploding amplitude profile versus a physically realizable uniform amplitude profile, i.e., flat-top profile, with the same power, both radially or azimuthally polarized. A first comparison would be a flat-top profile of the same power that always fills the aperture each time it is opened. As shown in [

7], the concentrating capacity of the flat-top profile is superior to that of the exploding beam, at least for paraxial NAs. However, this comparison involves a single exploding beam and a flat-top beam that must be continuously reconfigured for the same power to fill each aperture of radius

R.

Figure 4 compares the focusing performance of radially polarized exploding beam and a flat-top beam of the same power without reshaping. The exploding beam turns out to be the only real, finite-power beam that maintains the concentrating behaviour for arbitrary NA without resorting to any reshaping. We chose two radially polarized flat-top beams of fixed radii

[

Figure 4(a,b)] and

[

Figure 4(c,d)], both with the same power as the exploding beam, as these two values illustrate the two possible relative situations: The exploding beam focuses to higher intensity and smaller size than the flat-top when approaching maximum NA, and vice versa.

Figure 4 (a) and (c) show the peak amplitudes at the focal plane of the radial and axial components as functions of the NA, and

Figure 4 (b) and (d) their widths. Regardless of whether focusing with the flat-top beam is stronger or not, the intensity and size of the flat-top beams (green) always saturate to constant values beyond the numerical aperture NA

at which the entire flat-top is collected by the lens, while the curves of the intensity and size (red) never saturate, allowing unlimited and monotonous control of the focal properties with just one beam of light, like with an ideal plane wave but with finite power.

5. Conclusions

We have conducted an exact electromagnetic analysis of the focusing properties of the so-called exploding or concentrating beams with radial or azimuthal polarization, characterized by ever increasing focal intensity and shrinking focal spot as the numerical aperture of the focusing system increases. We have confirmed that this exploding behaviour holds not only under paraxial focusing conditions but also under tight, nonparaxial focusing conditions up to infinite aperture radius. As exploding beams carry finite power, they bring to the real world the focusing behaviour of an ideal plane wave of infinite lateral extent. The intensity singularity predicted by the paraxial focusing theory disappears, but as a memory of it in the approximate theory, the exploding behaviour continues to work.

Focusing, either weak or strong, is the most universal operation in the applications of light. We have demonstrated the existence of a physically realizable light beam that, contrary to previously known light beams, offers a smooth, continuous control of the focal properties solely through numerical aperture variation. Furthermore, under strong focusing conditions, exploding beams sustain strong and narrow axial electric and magnetic field components that far exceed the transversal components.

Acknowledgments

M.A.P. acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Gobierno de España, under Contract No. PID2021-122711NB-C21. M.G.B. acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Gobierno de España, through the European Union - NextGenerationEU grant. M.H. acknowledges support from Spanish Ministry of Education, Vocational Training and Sports, through the Becas de Colaboración en Departamentos Universitarios (No.C01) grant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dennis, M.R.; O’Holleran, K.; Padgett, M.J. Optical Vortices and Polarization Singularities. Progress in Optics 2009, 53, 293–363. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, J.F.; Berry, M.V. Dislocations in wave trains. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1974, 336, 165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, M.V.; Upstill, C. catastrophe optics: morphologies of caustics and their diffraction patterns. Progress in Optics 1980, 18, 257–346. [Google Scholar]

- Liangwei Zeng, J.Z. Preventing critical collapse of higher-order solitons by tailoring unconventional optical diffraction and nonlinearities. Communications Physics 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feit, M.D.; Fleck, J.A. Beam nonparaxiality, filament formation, and beam breakup in the self-focusing of optical beams. Optical Society of America B 1988, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A. Spontaneous generation of singularities in paraxial optical fields. Optics Letters 2016, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porras, M.A. Exploding paraxial beams, vortex beams, and cylindrical beams of light with finite power in linear media, and their enhanced longitudinal field. Physical Review A 2021, 103, 033506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1, M.G.B.; Holguín, M.; de Lara-Montoya, P.; Mata-Cervera, N.; Porras, M.A. Three-Dimensional Exploding Light Wave Packets. Photonics 2024, 11, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; Paúr, M.; Stoklasa, B.; Hradil, Z.; Řeháček, J.; Sánchez-Soto, L.L. Observation of concentrating paraxial beams. OSA Continuum 2020, 3, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Cervera, N.; Sharma, D.K.; Maruthiyodan Veetil, R.; Mass, T.W.W.; Porras, M.A.; Paniagua-Domínguez, R. Observation of Exploding Vortex Beams Generated by Amplitude and Phase All-Dielectric Metasurfaces. ACS Photonics 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lax, M.; Louisell, W.H.; McKnight, W.B. From Maxwell to paraxial wave optics. Physical Review A 1975, 11, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Q. Cylindrical vector beams: from mathematical concepts to applications. Advances in Optics and Photonics 2009, 1, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Paraxial exploding effect towards intensity singularity. Amplitude profile of a exploding beam at the lens plane. (b,c) Amplitude of the radial component and of the axial component of a radially polarized exploding beam at the focal plane for numerical apertures NA and NA and ideally focused with infinite aperture. The blue curves are the respective amplitudes at the lens and focal planes of the radially polarized LG beam of the same peak intensity and power at the lens. Data: nm, mm, , W, and mm.

Figure 1.

Paraxial exploding effect towards intensity singularity. Amplitude profile of a exploding beam at the lens plane. (b,c) Amplitude of the radial component and of the axial component of a radially polarized exploding beam at the focal plane for numerical apertures NA and NA and ideally focused with infinite aperture. The blue curves are the respective amplitudes at the lens and focal planes of the radially polarized LG beam of the same peak intensity and power at the lens. Data: nm, mm, , W, and mm.

Figure 2.

Illustration of a focused radially polarized exploding beam. Left: in red the electric field, in blue, the magnetic field. (a) Radial component, (b) axial component of the electric field, and (b) azimuthal component of the magnetic field at the focal plane. For azimuthally polarized exploding beam, the electric field is in blue, and the magnetic field is in red, (c) is the focused electric field and (a,b) is the magnetic field. Data: NA = 0.7. Data: nm, mm, , W, mm.

Figure 2.

Illustration of a focused radially polarized exploding beam. Left: in red the electric field, in blue, the magnetic field. (a) Radial component, (b) axial component of the electric field, and (b) azimuthal component of the magnetic field at the focal plane. For azimuthally polarized exploding beam, the electric field is in blue, and the magnetic field is in red, (c) is the focused electric field and (a,b) is the magnetic field. Data: NA = 0.7. Data: nm, mm, , W, mm.

Figure 3.

Nonparaxial exploding effect without singularity. (a,b) Focal peak amplitude of , and . (c,d) Radius of bright ring of , half-width (1/2-decay) of main lobe of and radius of the bright ring of , all them as functions of the numerical aperture NA. Red: exploding, black: paraxial exploding, blue: LG of the same peak intensity and power on the lens. Data: nm, mm, , W, mm.

Figure 3.

Nonparaxial exploding effect without singularity. (a,b) Focal peak amplitude of , and . (c,d) Radius of bright ring of , half-width (1/2-decay) of main lobe of and radius of the bright ring of , all them as functions of the numerical aperture NA. Red: exploding, black: paraxial exploding, blue: LG of the same peak intensity and power on the lens. Data: nm, mm, , W, mm.

Figure 4.

Radially polarized exploding vs. uniform beams. (a) Focal peak amplitudes of the radial and axial components of the electric field, (b) radius of the bright ring of the radial component and half width of the central lobe of the axial component, all as functions of the NA. In red, exploding beam; in green, uniform beam of the same power. Data: nm, mm, , W, mm, . (c,d) The same but for .

Figure 4.

Radially polarized exploding vs. uniform beams. (a) Focal peak amplitudes of the radial and axial components of the electric field, (b) radius of the bright ring of the radial component and half width of the central lobe of the axial component, all as functions of the NA. In red, exploding beam; in green, uniform beam of the same power. Data: nm, mm, , W, mm, . (c,d) The same but for .

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).