1. Introduction

Ensuring the supply of drinking water in cities whose populations exceed their carrying capacity [

1,

2] is becoming an increasingly complex challenge. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as part of the 2030 Agenda, have facilitated the implementation of actions and strategies focused on global sustainability, while also providing significant statistical data at both regional and national levels.

According to the United Nations [

3], under the framework of SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, it was reported in 2022 that 43% of Mexico’s population had access to safely managed drinking water services. In contrast, by 2023 it was reported that only 57% of monitored water bodies in Mexico exhibited adequate quality for human consumption, while 41% of water resources were managed through integrated approaches.

The aforementioned data reveal a mixed outlook regarding access to and management of water resources, highlighting both progress and limitations in achieving integrated management. This situation can be exacerbated by conventional tourism, given the increasing demand for water resources in areas with high tourist inflows. In 2023, Mexico ranked sixth worldwide in terms of international tourist arrivals [

4], underscoring the importance of ensuring the preservation of the country’s natural and cultural heritage.

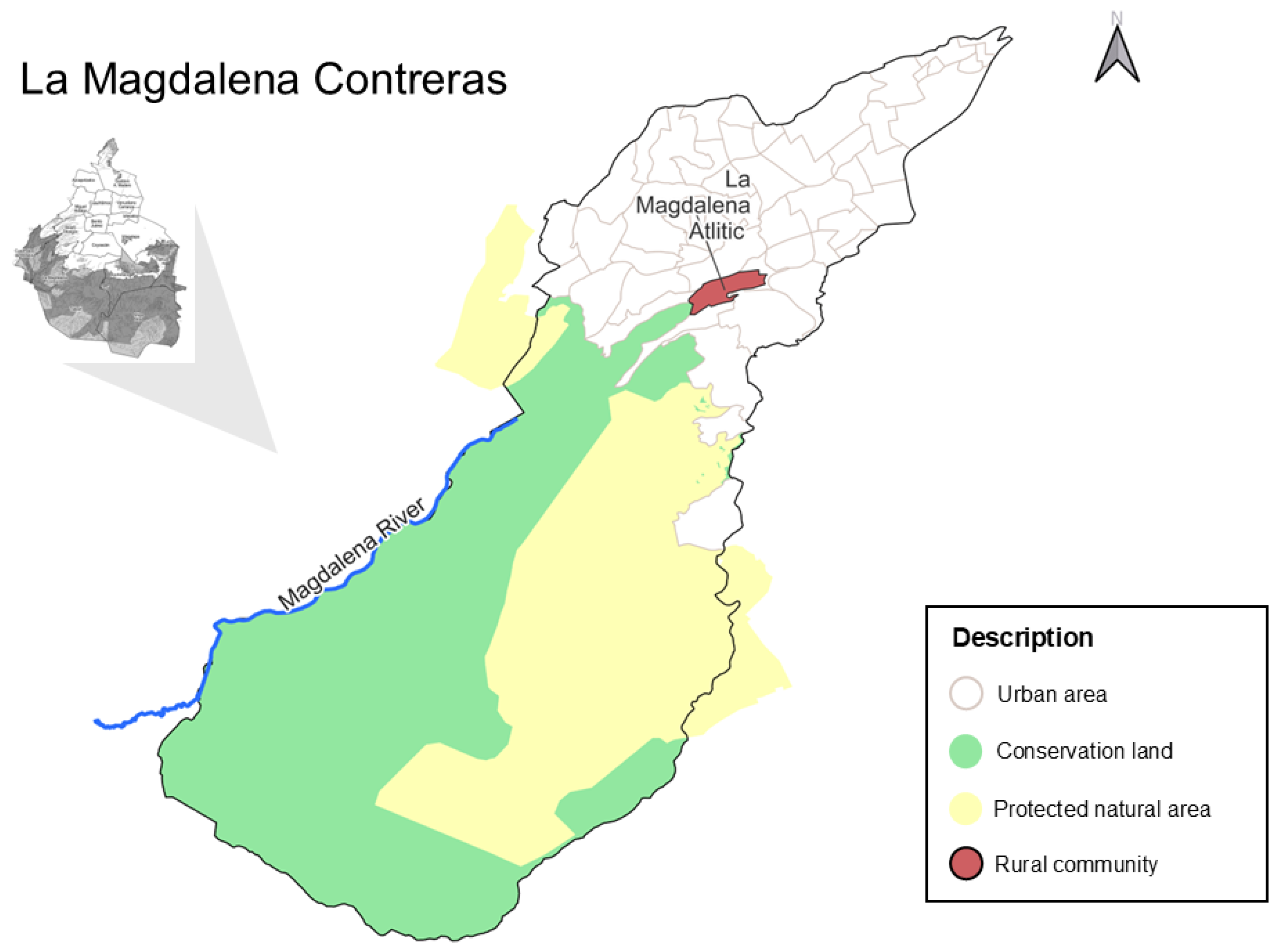

Mexico City (

Figure 1), with an estimated population of 12.2 million inhabitants in 2024 [

5], faces significant challenges in maintaining a balance that accounts for economic, social, political, and environmental factors. Among its geographical features, the city stands out for its altitude of 2,240 metres above sea level and its location within a high-mountain valley. This valley is surrounded by an extensive range of mountains and volcanoes, notably

Popocatépetl and

Iztaccíhuatl. The region experiences a temperate sub-humid climate, with rainfall concentrated mainly during the summer months.

As illustrated in the map, the metropolis is subdivided into sixteen boroughs, each with distinctive cultural and socio-economic characteristics. In addition, the city comprises 599 rural localities, which add an extra layer of diversity to its overall structure [

7]. This complexity reflects the richness and heterogeneity of both urban and rural fabrics, enriching the city’s cultural life while presenting specific challenges related to water management and tourism dynamics. The result is a multifaceted landscape in which diverse realities and needs intersect simultaneously.

The system under study in this research focuses on the rural community of

La Magdalena Atlitic (LMA) (

Figure 2), located in the borough of

La Magdalena Contreras, which covers an area of 63.4 km². This community maintains a close relationship with the Magdalena River, considered the last living river in Mexico City, with a total length of 28.2 km from its source to its confluence with the

Churubusco River, of which 14.8 km lie within conservation land [

8].

LMA is located within the Los Dinamos National Park, a Protected Natural Area encompassing 2,429 hectares of forest, an environment of high ecological value that provides essential environmental processes for sustaining human life. These attributes make the community a key actor in sustainable water management, as its direct connection with the river represents a significant opportunity for environmental preservation.

In this context, the social enterprises operating in LMA aim to strengthen community cohesion and promote a form of local governance capable of responding resiliently to the socio-environmental challenges derived from mass tourism and urbanisation. The objective of this research is to develop a diagnostic analysis of the social enterprises in LMA, identifying how their organisational structures and decision-making processes support sustainable water management through practices that flexibly adapt to current challenges.

2. Literature Review

The concept of entrepreneurship has its earliest roots in the late eighteenth century with Adam Smith [

9], who introduced the terms ‘projector’ and ‘undertaker’ to describe individuals who performed administrative and managerial functions within an individual project. This recognition of actors involved in both innovation and economic activity encouraged other economic theorists, such as Say, Mill, Marshall, and Schumpeter [

10,

11,

12,

13], to expand and consolidate the concept.

This evolution reflects how entrepreneurship has come to be understood as a higher-level activity associated with innovation, risk-taking, and the capacity to generate structural changes in both the economy and society. At present, entrepreneurship continues to operate as part of a complex system, directly influenced by factors such as the environment, public policies, government strategies, and societal dynamics. It is even acknowledged that national culture plays a significant role in shaping how entrepreneurship is practised and developed [

14].

As a result of these multiple influences, the role of entrepreneurship has been redefined, placing greater emphasis on the social sphere and the generation of collective benefits. Although there is currently no universally accepted definition of the concept, the literature highlights contributions such as that of Dees [

15], who defines it as the identification and exploitation of opportunities for transformative social change by visionary individuals.

While various interpretations exist, the social value generated through the application of innovative, sustainability-oriented approaches is widely recognised [

16]. Furthermore, social entrepreneurship is understood to address local challenges using the resources and capacities of individuals, with the aim of delivering systemic solutions and transformative change [

17].

2.1. Social Entrepreneurship and Its Link to Rural Tourism

Addressing these challenges takes on particular importance in communities deeply connected to natural environments. The relevance of their initiatives lies not only in generating economic income but also in strengthening social cohesion, preserving cultural identity, and ensuring the sustainability of the natural resources upon which they depend [

18], such as water, forests, and soil.

Thus, social entrepreneurship embedded within rural communities becomes a complex system capable of driving innovation through local governance, contributing to community resilience in the face of external pressures such as climate change, urbanisation, or overtourism. This space enables the implementation of dynamics that support environmental well-being and the development of community projects focused on environmental conservation, community-based water management, and cultural preservation [

19].

In rural contexts with a strong tourism orientation, social entrepreneurship stands out for introducing innovative solutions that strengthen community resilience in the face of environmental and social challenges. An illustrative example can be found in Iran [

20], where social enterprises have significantly contributed to transforming the tourism dynamic into a more sustainable model.

These practices not only strengthen the local economy but also help achieve social and international objectives, such as those established in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The study of such cases in rural communities with a tourism vocation provides valuable insights for the design of policies and the implementation of rural tourism practices that emphasise the importance of an approach combining sustainability, community resilience, and local development. Moreover, this form of tourism contributes to the preservation of local traditions and customs, as it actively involves the community in the tourism dynamic [

21,

22].

This is reflected in the tourism products and services developed by the community, which not only respond to tourist demand but also represent models applicable to both developed and developing countries. Countries such as Spain, which combines densely populated urban areas with rural communities affected by urban expansion, have found in rural tourism a viable solution, one that requires the implementation of rural adaptation policies to avoid compromising the environment [

23].

Another example can be found in the rural areas of the Balinese islands in Indonesia, where the use of natural resources is guided by principles of preservation and an appreciation of Indigenous knowledge. This approach seeks to meet tourist demand without irreversibly transforming rural landscapes, thereby avoiding the negative impacts typically associated with overtourism [

24]. In Miao, China, a study explored the growth of rural tourism and how entrepreneurial initiatives have driven sustainable economic development in the region’s rural areas. These efforts have particularly benefited women artisans, improving both their income levels and social standing [

25].

In contrast, in

Bodaofeng Forest Farm, China, rural tourism fosters a constant negotiation between modernisation and tradition. In this process, communities reconfigure their identities to integrate into the tourism economy without abandoning their cultural roots, resulting in a complex process of social transformation [

26]. Another study, also conducted in China, revealed that the success of social enterprises largely depends on two key factors: 1. Legitimacy, represented by the recognition and acceptance they receive from both the community and institutions; and; 2. Social capital, understood as the networks of trust, cooperation, and reciprocity built within the community [

27].

In the Philippines, strategies have been implemented to develop tourism enterprises based on sustainable farms, where visitors engage in educational experiences that promote awareness of eco-friendly agricultural techniques. These initiatives generate both economic and social benefits by fostering environmental education and strengthening community resilience [

28]. In the case of Mexico, the implementation of a systemic model has contributed to advancing social entrepreneurship in rural tourism contexts towards the achievement of the SDGs, promoting collective well-being and reinforcing the cultural identity of the community [

29].

This interconnection between social entrepreneurship and rural tourism is particularly significant, as it provides communities with the tools to adapt to external pressures through productive models that prioritise collective participation and the responsible use of resources [

30]. Thus, rural tourism transcends its purely economic dimension to become a space for social innovation, fostering resilience in the face of threats such as climate change, uncontrolled urbanisation, and pressure on water systems.

2.2. Water Management in Rural Communities with a Tourism Vocation

Geographical factors directly influence both the volume and the type of water use, as seen in rural areas or less urbanised environments. In the case of tourism in rural zones, water-use patterns tend to differ, generally showing lower consumption levels compared with urban areas [

31]. This level of water consumption varies according to the type of tourism dynamic that develops within each context.

In this regard, water management in rural contexts with a tourism vocation has gained increasing importance in its role of protecting aquatic ecosystems and the biodiversity of these particularly vulnerable areas. The crises faced by such regions are often driven by overtourism, which demands collaboration among local actors [

32]. The effectiveness of these efforts depends on the implementation of integrated and adaptive approaches that recognise the socio-ecological complexity of the environments in which they operate.

Specifically, the tourism dynamic involves significant water consumption, making it essential to implement targeted water-saving policies and efficient management practices. These measures aim to balance tourism development, particularly in rural and coastal areas [

33]. Several studies warn that mass tourism exerts direct pressure on local water resources, especially in rural tourism destinations or regions already facing some degree of water stress [

34].

In this scenario, the adoption of water-efficient technologies emerges as an effective strategy, as it is estimated that such measures can reduce water consumption by up to 30% in tourism facilities, directly contributing to lowering the sector’s environmental impact Moreover, it is crucial to identify the role of each stakeholder involved in the tourism dynamic, such as tourism managers and local authorities, who are responsible for designing public policies capable of integrating other actors, both public and private, to anticipate potential crises and respond to increasing demand [

36]. This approach leads to a comprehensive water management system that considers both the pressures of tourism and the needs of rural communities.

Within this framework, water management in rural communities entails the construction of a collaborative governance process, in which local actors, rural communities, authorities, tourism managers, and social entrepreneurs actively participate in decision-making [

37]. This form of management does not reduce water resources to a mere component of tourism; rather, it recognises them as a common good, essential for daily life and the preservation of cultural heritage.

Research has shown that when water management incorporates the voice of local communities, it fosters resilient institutional arrangements capable of responding effectively to crises such as prolonged droughts or aquifer overexploitation [

38]. In this regard, social enterprises can also play a strategic role as mediators between the demands arising from tourism dynamics and the needs of the community, helping to balance environmental protection with local well-being.

Likewise, water management in rural areas with a tourism vocation requires a systemic perspective, one that not only addresses the immediate pressures of tourism, but also anticipates future scenarios linked to climate change and urbanisation. To achieve this, it is essential to integrate models, practices, and mechanisms operating across multiple levels of reality, where community initiatives, public policies, and technological innovation converge. Recognising this complexity allows the adoption of governance frameworks that ensure the sustainability of tourism, strengthen social cohesion, and safeguard the well-being of present and future generations.

2.3. Agile Governance

Agility, understood as the adaptive capacity and speed of an organisation to respond effectively to changes in its environment [

39], has gained increasing relevance within complex systems, particularly in contexts characterised by constant change and uncertainty. This complexity compels organisations to adopt an adaptive stance, enabling them to anticipate and respond effectively to emerging challenges. Those that successfully sustain this agile capability are able to strengthen their connections across multiple levels of reality, the macro, meso and microenvironments, thus enhancing coherence, coordination, and systemic resilience.

The implementation of flexible governance models that distribute authority and encourage collective participation enables organisations to deliver responses aligned with continuous learning and adaptive improvement [

40]. Possessing this characteristic is fundamental for complex systems with high levels of human interaction, as it allows them to remain viable and self-organising over time. This is especially critical when facing environmental, social, or economic pressures, where resilience depends not only on control mechanisms but also on the organisation’s capacity to learn, adapt, and co-evolve with its surroundings.

Agility plays a crucial role in social enterprises, as it reinforces their connection with the environment while enhancing their ability to adapt and generate meaningful structural change. Governance is essential for this process, as it enables the creation of systems and processes that regulate themselves voluntarily [

41]. Traditional corporate governance literature, however, tends to focus on easily measurable aspects, such as board size, composition, and cost reduction—often overlooking other key dimensions like adaptive capacity [

42].

This limitation has given rise to emerging concepts such as agile governance, understood as the organisation’s ability to balance control and flexibility in decision-making, adapting governance processes to improve responsiveness [

43]. It involves interdisciplinary collaboration, transparency, and iterative review and distribution cycles. Moreover, it is characterised by open information flows and less hierarchical structures, which promote both agility and effective coordination in times of crisis.

The relevance of agile governance within social enterprises carries a deeper meaning, as these systems often operate in territories where economic, ecological, and political conditions change rapidly. This demands a management approach capable of adapting without compromising community values. It translates into governance processes in which trust, reciprocity, and cooperation serve as regulatory mechanisms, replacing organisational rigidity with responsible autonomy that preserves alignment with the organisation’s social purpose.

Models such as Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM) [

44] provide a meaningful bridge between structure and adaptability. This framework proposes that a system’s viability depends on the balance among five interrelated subsystems, which together ensure internal cohesion and the capacity to respond effectively to changing environmental conditions. The VSM enables organisations to maintain stability while preserving both autonomy and operational flexibility.

Agile governance complements this model by introducing the dynamic dimension required for systems to remain viable and evolutionary. It contributes the fluidity and openness that the VSM establishes methodologically, creating a synergy between systemic structure and adaptive capability. Combined, these perspectives offer a more holistic understanding of organisations as living systems, capable of continuous learning, adaptation, and transformation. In rural communities with a tourism vocation, this integration proves particularly valuable, as it enables them to balance environmental preservation, cultural resilience, and sustainable local development.

In rural communities with a tourism vocation, this integration becomes particularly meaningful. The social enterprises operating in these territories face a constant tension between cultural preservation, environmental sustainability, and the pursuit of economic wellbeing. Analysing their functioning through the complementarity between the VSM and agile governance provides insight into how these systems integrate and evolve over time.

In this way, systems thinking emerges as a framework for fostering organisational systems that are adaptive and environmentally aware, capable of maintaining their viability without losing their capacity for transformation. This theoretical foundation sets the stage for the following methodological section, which employs the VSM to diagnose the organisational viability and adaptive capacity of the social enterprises in LMA.

3. Method

The VSM, developed by Beer [

44], is a framework designed to ensure the sustainability and adaptability of organisations operating in environments characterised by complexity and constant change. Its core principle asserts that every system must possess a set of essential functions that allow it to maintain internal stability while adapting to external dynamics. The model is structured around five interconnected subsystems, each performing a distinct but complementary role: Operations (S1), responsible for executing the organisation’s primary activities; Coordination (S2), which harmonises communication and workflow among operational units; Control and Audit (S3/S3*), tasked with internal supervision and performance monitoring; Intelligence (S4), which analyses the environment and anticipates future transformations; and Policy or Identity (S5), which defines the organisation’s strategic direction, purpose, and values [

45].

These subsystems embody the core functions that any organisation must perform to adapt effectively to its environment and ensure long-term sustainability. Through the interaction of these subsystems, this model provides a cybernetic architecture capable of achieving both autonomy and coherence. The strength of the VSM lies in its ability to integrate both structure and dynamism, making it particularly relevant for the analysis of rural communities with a tourism vocation, where environmental and social pressures demand adaptive responses without undermining local identity and cultural integrity.

This research adopts the VSM as a methodological framework to diagnose the social enterprises operating in LMA, with the aim of identifying their strengths, limitations, and adaptive potential in response to the challenges posed by overtourism and its impact on the Magdalena River’s water resources. Through this approach, it becomes possible to assess the viability of existing governance mechanisms and evaluate how agile and responsive these systems are to changes in tourism demand, ecological conditions, and other external pressures.

The VSM is complemented here with the agile governance approach, enabling an exploration of how social enterprises develop the capacity for collective learning, process reconfiguration, and sustained viability without relying solely on hierarchical structures. The integration of both frameworks strengthens the analytical depth of this study by addressing two essential dimensions: the structural coherence of the system, as conceptualised by Beer, and its adaptive capacity to respond to uncertain and rapidly changing contexts.

For the data collection, field visits and virtual sessions were conducted with local stakeholders in LMA. These activities enabled the documentation of interactions among entrepreneurs, community representatives, and tourists in relation to water resource management and the impacts of tourism activities. This process was essential for engaging the community in the study and for jointly planning strategies aimed at achieving sustainable water management.

Through these sessions, participants were able to reflect on their own practices and identify the main challenges related to resource management. Collectively, the application of the VSM made it possible to map the functional relationships within the system under study, identify its vulnerabilities, and propose more agile and resilient coordination mechanisms. This methodological process not only provides an organisational diagnosis but also serves as a practical guide for adaptive water and tourism management in rural communities, aligned with the principles of sustainability and collaborative governance.

4. VSM Diagnosis

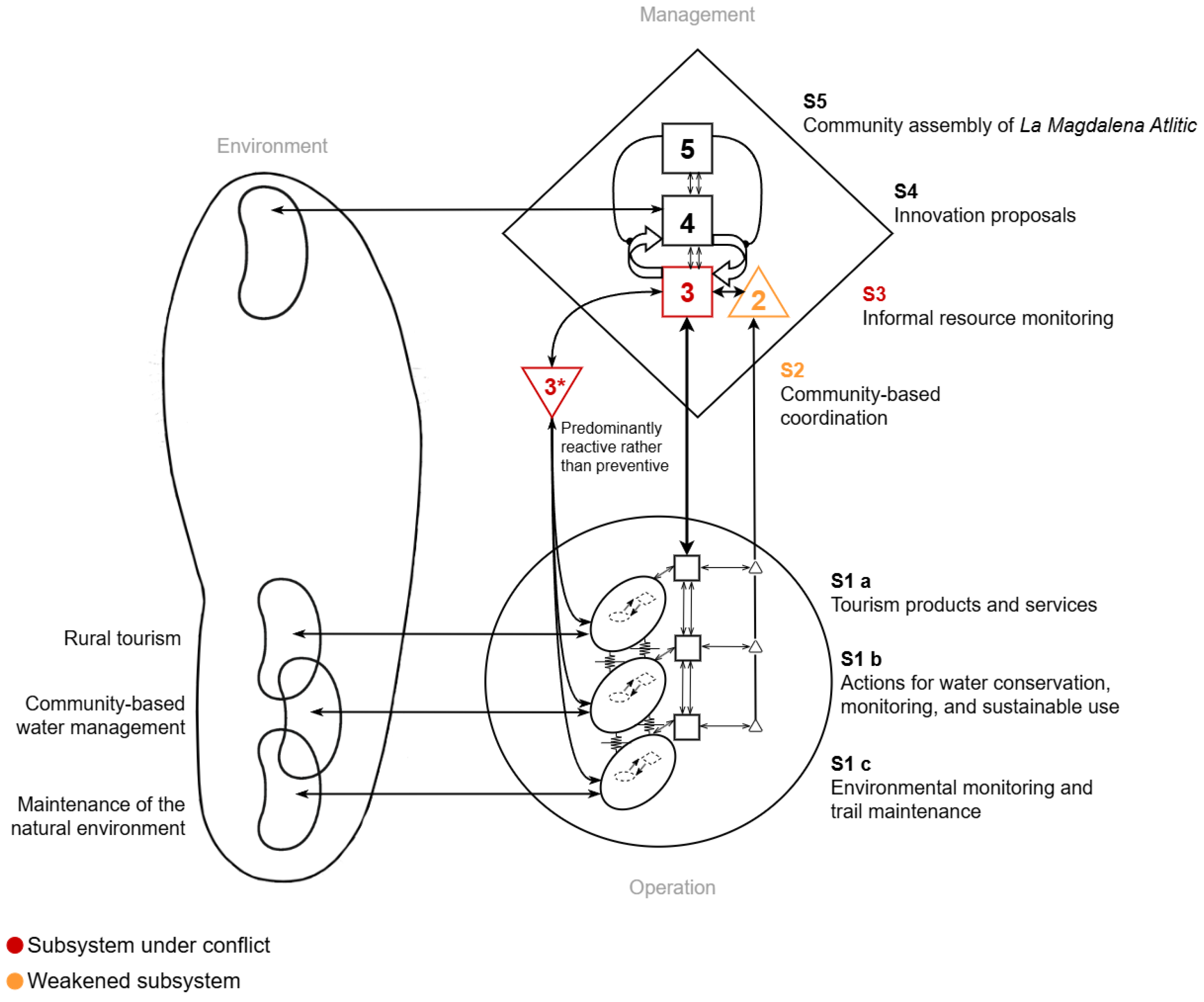

The application of the VSM revealed the organisational structure underpinning the social enterprises involved in tourism and water management. This representation (

Figure 3) illustrates how the community integrates economic, ecological, and cultural activities to sustain its functioning in the face of external pressures such as urbanisation, mass tourism, and climate change.

The diagnosis indicates that social enterprises operate as the core operational component of the system (S1). These are structured into three operational units:

S1a: Rural tourism initiatives and the provision of local products and services such as guided tours, food and craft sales, hiking, and cultural experiences.

S1b: Activities focused on the care, monitoring, and use of the water resource (the Magdalena River), including channel cleaning and agreements on water use among local actors.

S1c: Environmental maintenance through reforestation practices and the cleaning of trails within Los Dinamos National Park.

Each of these units performs autonomous yet interdependent functions, linked through informal communication flows and collaborative agreements. Together, they constitute the productive structure that sustains the system.

System 2 (S2) represents the synchronisation and coordination mechanisms among the operational units, designed to prevent conflicts and redundancies. This corresponds to the community-level coordination processes that regulate interactions between the operational subsystems. The diagnosis reveals that such coordination relies heavily on individual commitment and mutual trust among community members, making it vulnerable to internal tensions and the absence of formal procedures. Despite the existence of a local collaboration network, communication among its members remains inefficient, resulting in a subsystem weakened by both internal and external disruptions.

System 3 (S3), responsible for internal supervision and resource control, is in a fragile condition that exposes the system’s limitations in sustaining agile governance. Control activities, such as monitoring water use, organising tourism operations, and maintaining the surrounding environment is conducted through informal agreements and collective oversight. These processes rely more on goodwill and mutual understanding than on formalised or standardised mechanisms, which restricts the community’s ability to ensure consistent accountability and efficiency. This fragility suggests that while there is a sense of shared responsibility, the absence of institutionalised tools for evaluation and feedback prevents the establishment of a learning cycle essential for adaptive and agile management.

The management of both the enterprises and the water resource follows a reactive logic: actions are taken only in response to immediate contingencies, such as a decrease in the river’s flow, the accumulation of waste along trails, or disputes among tourism service providers, rather than through anticipatory planning or preventive procedures. This lack of monitoring instruments and performance evaluation mechanisms prevents the collection of reliable data on water consumption and environmental impacts. Consequently, it hinders agile decision-making and disrupts effective feedback loops toward the higher subsystems, limiting the system’s ability to learn, adapt, and coordinate collective responses in a timely manner.

Together with System 3* (S3*), which functions as an external corrective mechanism, occasional support is provided by governmental institutions such as administrative managers from La Magdalena Contreras borough and environmental and tourism agencies at various levels. However, the non-permanent and fragmented nature of this external intervention restricts the potential of S3*. It is also essential to consider other external actors from the academic and social spheres. In this regard, the Centro de Estudios de la Cuenca del Río Magdalena (CECRM), composed of both residents from LMA and external collaborators, plays a pivotal role in sustaining the functioning of System 3*.

By introducing external information, the CECRM stimulates internal improvement and reconfigures the relationships among subsystems. For example, through technical assistance in socio-environmental projects, joint river-cleaning campaigns, and meetings to define water-use boundaries, the centre provides structured control practices and fosters transparency in resource management. These collaborative interactions enhance the system’s learning capacity and reinforce the community’s ability to adapt its governance processes in alignment with sustainability principles.

System 4 (S4) embodies the community’s organisational and adaptive intelligence of the system under study. It is responsible for environmental scanning, anticipating change, and fostering innovation. Within this subsystem, processes of collective learning emerge from the interaction between social enterprises and external actors, including academic institutions and environmental organisations. This continuous exchange nurtures the community’s capacity to interpret external signals and integrate new knowledge into local practices.

At this level, local practices are connected with technical and scientific knowledge, fostering the creation of strategies for water management, the improvement of tourism services, and the conservation of the natural environment. This organisational intelligence also integrates local knowledge, traditional practices, and the community’s accumulated experience, elements that are essential for agile governance, which recognises learning as a distributed and collaborative process.

Agile governance introduces a dynamic dimension to this subsystem by fostering flexibility in decision-making. In practice, this translates into the system’s capacity to readjust its strategies as environmental conditions or tourism demand fluctuate, without compromising its collective identity. For instance, during high tourist seasons, the community reorganises routes and reallocates work shifts among enterprises, demonstrating a process of self-organisation aligned with the principles of agility.

To strengthen systemic viability, System 4 (S4) must develop internal intelligence mechanisms that do not rely solely on external projects or political cycles. An effective strategy for this context would be the establishment of community learning spaces, where the outcomes of local experiences, environmental observations, and management agreements are systematically recorded and shared as part of a collective organisational memory.

System 5 (S5) represents the identity and purpose of the system, embodied in the community assembly of La Magdalena Atlitic. This collective space establishes community rules, validates decisions regarding resource use, and guides the actions of local enterprises towards a shared goal: the preservation of the Magdalena River and the gradual replacement of mass tourism with sustainable rural tourism and other low-impact activities.

The teleology of the system rests on two fundamental pillars: the preservation of the Magdalena River and the regulation of tourism dynamics to prevent massification processes that threaten the ecological and cultural balance. System 5 (S5) thus transcends a merely normative role—it also fulfils ontological and cultural functions, sustaining a sense of belonging, reciprocity, and mutual care that legitimises collective action. Through this level, the system operates as a second-order metasystem regulator, interpreting and reframing external influences according to the community’s core principles and values.

It serves as the moral compass and strategic anchor that keeps the system adaptable yet grounded in its collective purpose. In this way, S5 provides continuity and coherence between identity and action, ensuring that decisions taken within the community remain aligned with its long-term vision of cultural integrity, environmental stewardship, and systemic viability.

The diagnosis reveals that this system faces the challenge of maintaining cohesion among all actors involved. The tensions between those seeking to strengthen rural tourism and those who perceive it as a threat to environmental balance indicate that the system’s identity is undergoing a process of continuous redefinition. From a cybernetic perspective, this tension should not be seen as a weakness but rather as a sign of adaptive evolution, where the community continuously learns to integrate diversity without fragmenting.

The synthesis of the five subsystems reveals that the viability of the community system depends on its ability to balance autonomy and cohesion. Subsystems S3, S3* and S2 exhibit structural weaknesses and internal conflicts that hinder feedback between systems and the production of reliable information for decision-making. This condition explains why much of the community’s management remains intuitive and reactive, rather than preventive or strategic.

5. Discussion

The diagnosis conducted through the VSM revealed the strengths, weaknesses, and structural tensions of the social tourism enterprises in LMA, as well as their potential to foster sustainable water management through flexible and self-organised organisational structures. Consistent with other studies that apply organisational cybernetics within Latin American contexts [

46], the findings confirm that the viability of community systems depends equally on their internal cohesion and their capacity to adapt to the external environment. This dual dependency underscores the importance of creating governance frameworks that can both preserve cultural identity and remain agile in the face of social and environmental change.

The results indicate that the operational subsystems (S1a, S1b, and S1c) maintain a strong interrelationship, as they integrate economic, ecological, and cultural activities that sustain the community as a whole. However, this strength has not yet been translated into effective mechanisms of coordination, control, and auditing (S2, S3, and S3*). As a consequence, information gaps persist, weakening the flow of communication between units and limiting collective learning processes.

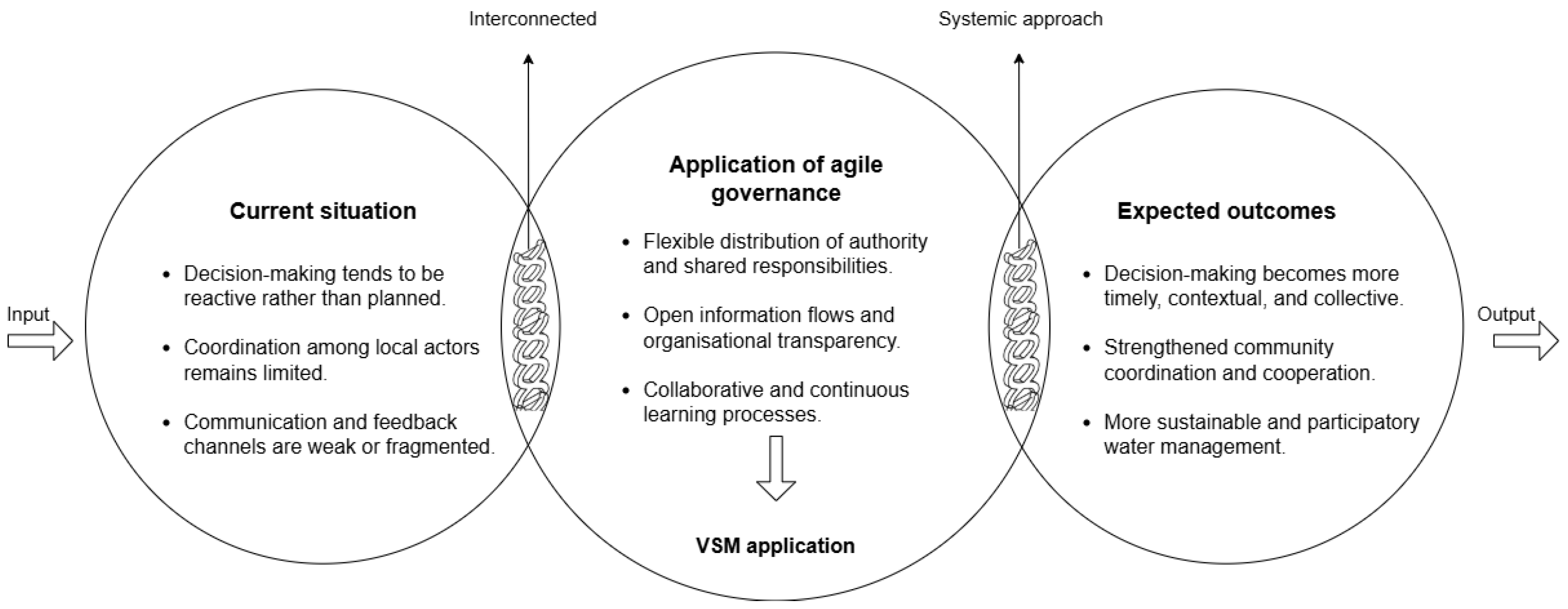

These systemic pathologies can be reframed as opportunities to evolve towards states of homeostasis and organisational balance. The integration of agile governance provides a pathway to overcoming structural rigidity and operational limitations, reinforcing collective learning processes within the system. Through adaptive and participatory mechanisms, social enterprises can adjust their tourism products and services in response to the complexity of their environment, for instance, by reconfiguring operations during fluctuating tourist seasons or adapting practices to changes in the Magdalena River’s water flow.

The intelligence (S4) and identity (S5) subsystems stand out as vital spaces that nurture community resilience through continuous learning. The S4 subsystem acts as a bridge between the community and its external environment, fostering partnerships with universities, environmental organisations, and institutional actors. This highlights the need to consolidate an organisational intelligence capable of sustaining innovation beyond temporary external interventions. Building such intelligence ensures that the community’s development remains internally driven, contextually relevant, and adaptable to environmental and social shifts. The S5 subsystem, in turn, embodies the identity and overarching purpose of the system, manifested through the community assembly that safeguards the coherence of collective values.

At this level, agile governance reinforces the teleology of the system under study, enabling the integration of autonomy and flexibility, both essential principles of organisational viability as outlined by Beer [

47]. The coexistence of diverse actors—entrepreneurs, local authorities, and tourists—within the same systemic environment highlights the urgency of strengthening communication channels and feedback mechanisms among them. Improved connectivity would foster better coordination, mutual understanding, and shared responsibility in decision-making processes.

At present, information within the system circulates in a fragmented manner, with limited formal feedback mechanisms, which constrains the community’s ability to make well-informed and timely decisions. Implementing agile mechanisms, such as regular system reviews, simplified monitoring indicators, and collaborative work cycles among community members, could significantly enhance traceability in decision-making and improve water resource management.

Figure 4 illustrates how agile governance can transform the current reactive and fragmented management model of social enterprises into a collaborative and sustainable structure, aligned with the real conditions and challenges faced by the rural community. This transition from fragmented decision-making to coordinated adaptability represents a cultural shift toward a governance model rooted in participation and continuous learning.

The community currently exists in a partial state of viability. The operational subsystems demonstrate vitality and sustained activity; however, the management subsystems require reinforcement to achieve long-term autonomy and stability. This imbalance reveals structural weaknesses that limit the system’s ability to maintain coherence and adapt to its evolving reality.

The convergence between the VSM and agile governance opens the possibility of designing living, conscious, and resilient organisations, where a shared identity becomes the guiding axis for achieving sustainable water management. By integrating systemic principles with agile practices, the community can develop mechanisms that are both structured and adaptable, enabling proactive responses to environmental and social challenges.

Within the Systemic Approach, this transition introduces a necessary dynamic element, the “how,” to achieve homeostasis grounded in the teleology of the system under study. It encourages the strengthening of the community’s organisational capacity and collective learning, allowing it to thrive amid complexity while remaining faithful to its ecological and cultural purpose.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the application of the VSM, in conjunction with the principles of agile governance, provides an effective framework for diagnosing and strengthening the organisational viability of social enterprises engaged in rural tourism, such as those in LMA. This integrated approach made it possible to identify specific mechanisms to improve the structure, activities, and operational processes of social enterprises and to show how such improvements can lead to more sustainable water management within the dynamics of tourism.

S1 holds a pivotal role within the system under study, as it integrates economic, ecological, and cultural activities that sustain community life in LMA. However, the weaknesses and conflicts identified in S2 and S3 reveal the urgent need to transition from a reactive posture to one that is preventive and strategically guided, grounded in reliable information and continuous feedback across all operational levels.

This limitation is closely related to System 3, which, although functioning as a corrective external mechanism, has not yet evolved into a formal auditing body capable of ensuring both accountability and organisational learning. Strengthening this function would enable the community to establish clearer feedback loops, improve coordination, and support the development of adaptive practices aligned with the principles of agile governance.

S4 and S5 demonstrate notable progress in developing adaptive processes and in aligning the teleology of the system. The community’s organisational intelligence is evidenced through its collaboration with the CECRM, which enables the integration of external knowledge and fosters innovation. Meanwhile, the community assembly plays a crucial role in reinforcing the identity and shared purpose of the system under study, ensuring coherence between ecological preservation and social objectives. It is essential, however, that both subsystems formalise continuous learning processes to ensure their persistence beyond the immediate success of specific social enterprises.

The relationship between the VSM and agile governance establishes a crucial systemic collaboration that enables a deeper understanding of how complex human activity systems situated in rural communities with a tourism vocation can achieve balance despite environmental, touristic, and urban challenges. This study provides empirical evidence that organisational viability in rural contexts does not rely solely on rigid or formal structures but rather on the community’s capacity for self-organisation, collective learning, and adaptive transformation.

Future research should consider applying the VSM to socio-ecological systems, integrating agile governance principles to design or reshape organisational structures that remain both adaptive and sustainable. In summary, the LMA community exemplifies how the combination of systemic thinking and adaptive governance can contribute to sustainable rural tourism and responsible water management, paving the way toward the development of viable and self-organising communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.P.-M and R.T.-P.; methodology and validation, R.T.-P and I.B.-P.; formal analysis, Z.P.-M., R.T.-P and I.B.-P; investigation and resources, R.T.-P., Z.P.-M. and E.M.B.-R.; data acquisition, E.M.B.-R. and I.B.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.P-M., R.T.-P. and E.M.B.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Instituto Politécnico Nacional, México, through the transdisciplinary project SIP 3420, granted by the Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado and Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI), México.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the community of La Magdalena Atlitic for their openness, collaboration, and trust throughout the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xess, S.; Bhargava, D.A. Carrying Capacity of Urban Transportation Networks: A Case Study of Designed Ideal City. In Proceedings of the 7th GoGreen Summit 2021; Singh, S., Kianmehr, P., Aurifullah, M., Dragomirescu, M., Eds.; Technoarete, 2021; pp. 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrino Figueroa, L.J. Dinámica Demográfica, Forma Urbana y Densidad de Población En Ciudades de México, 1990-2020: ¿urbanización Compacta o Dispersa? Estud. Demogr. Urbanos Col. Mex. 2024, 39, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONU Instantánea Del ODS 6 En México. Available online: https://sdg6data.org/es/country-or-area/Mexico#anchor_6.1.1.

- ONU Turismo En 2023, Con La Reapertura de Asia y El Pacífico Al Turismo, China Recuperó Su Primera Posición En La Clasificación de Países Que Más Gastan Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/news/en-2023-con-la-reapertura-de-asia-y-el-pacifico-al-turismo-china-recupero-su-primera-posicion-en-la-clasificacion-de-paises-que-mas-gastan#:~:text=En cuanto a los ingresos,56 000 millones de USD).

- World, P.R. Mexico Population 2025. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/mexico (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- INEGI México En Cifras. La Magdalena Contreras. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/#collapse-Resumen.

- INEGI Población Rural y Urbana. 2020.

- Zamora, I.B. Dos Modelos de Gestión En La Historia Del Río Magdalena, Ciudad de México. El Repartimiento Colonial y La Junta de Aguas. Cuicuilco Rev. Ciencias Antropológicas 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1976 Ed.). Norman S. B. Dunwoody, GA, 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Economic Theory and Entrepreneurial History. In Explorations in enterprise; Harvard University Press, 1965; pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Say, J.B. Cours Complet d’Economique Politique Pratuque. Adam Smith’s Legacy. M. Fry. London and New York 1829.

- Mill, J.S. Principles of Political Economy. London, Engl. John W. Park. 1848. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. 1920. Principles of Economics. London: Mac-Millan, 1890; 1–627. [Google Scholar]

- Bate, A.F.; Pittaway, L.; Sàndor, D. Unveiling the Influence of National Culture on Entrepreneurship: Systematic Literature Review. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2025, 17, 875–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G. The Meaning of “Social Entrepreneurship, 2001.

- Nicholls, A. The Legitimacy of Social Entrepreneurship: Reflexive Isomorphism in a Pre–Paradigmatic Field. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 611–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.L.; Kothari, T.H.; Shea, M. Patterns of Meaning in the Social Entrepreneurship Literature: A Research Platform. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Martí, I. Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Source of Explanation, Prediction, and Delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Zhu, Z.; Trachung, B.; Golog, D.; Riley, M.; Zhi, L.; Li, L. Communities in Ecosystem Restoration: The Role of Inclusive Values and Local Elites’ Narrative Innovations. People Nat. 2024, 6, 1655–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, A.; Nasrolahi Vosta, L.; Ebrahimi, A.; Jalilvand, M.R. The Contributions of Social Entrepreneurship and Transformational Leadership to Performance. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2019, 39, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan Ayhan, Ç.; Cengi̇z Taşlı, T.; Özkök, F.; Tatlı, H. Land Use Suitability Analysis of Rural Tourism Activities: Yenice, Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C.; Miranda-Salazar, S.P.; Tierra-Tierra, N.P. Strengthening of Community Tourism Enterprises as a Means of Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Case Study of Community Tourism Development in Chimborazo. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E.; González-Portillo, A. Limiting Rural Tourism: Local Agency and Community-Based Tourism in Andalusia (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2024, 104, 104938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, P.D.; Wang, Y.; Dupre, K.; Putra, I.N.D.; Jin, X. Rural Tourism in Bali: Towards a Conflict-Based Tourism Resource Typology and Management. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 0, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Z. Cultural Heritage as Rural Economic Development: Batik Production amongst China’s Miao Population. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Knight, D.W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zi, M. Rural Tourism and Evolving Identities of Chinese Communities in Forested Areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Huang, K. How Does Social Entrepreneurship Achieve Sustainable Development Goals in Rural Tourism Destinations? The Role of Legitimacy and Social Capital. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 0, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaye, D.C. Climate Smart Agriculture Edu-Tourism: A Strategy to Sustain Grassroots Pro-Biodiversity Entrepreneurship in the Philippines. In Proceedings of the Cultural Sustainable Tourism: A Selection of Research Papers from IEREK Conference on Cultural Sustainable Tourism (CST), Greece, 2017; Springer, 2019; pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Tejeida-Padilla, R.; Pérez-Matamoros, Z.; Rodríguez-Escalona, M.L.; Hernández-Simón, L.M.; Badillo-Piña, I. Social Entrepreneurship and SDGs in Rural Tourism Communities: A Systemic Approach in Yecapixtla, Morelos, Mexico. World 2025, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, B. Rural Tourism in China: ‘Root-Seeking’ and Construction of National Identity. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.; Dubois, G.; Vergne, L.; Scott, D. Progress in Tourism Management Tourism and Water Use: Supply, Demand, and Security. An International Review. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; ElDidi, H.; Masuda, Y.J.; Meinzen-Dick, R.S.; Swallow, K.A.; Ringler, C.; DeMello, N.; Aldous, A. Community-Based Conservation of Freshwater Resources: Learning from a Critical Review of the Literature and Case Studies. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2023, 36, 733–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.; Lyu, W.; Luo, W.; Yao, W. Analysis of Water Resource Management in Tourism in China Using a Coupling Degree Model. Water Policy 2021, 23, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Overtourism in Rural Areas. In Overtourism; Séraphin, H., Gladkikh, T., Vo Thanh, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 27–43. ISBN 978-3-030-42458-9. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, W. Sustainable Tourism: Pathways to Environmental Preservation, Economic Growth, and Social Equity. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 66, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phong, N.T.; Van Tien, H. Water Resource Management and Island Tourism Development: Insights from Phu Quoc, Kien Giang, Vietnam. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 17835–17856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.Z.; Tejeida, P.R.; Patiño, A.R. La Sistémica Transdisciplinar En La Gestión Sostenible Del Agua En Emprendimientos Sociales Turísticos de Comunidades Rurales de La Ciudad de México 1. 2024; 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delves, J.L.; Clark, V.R.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Barker, N.P.; Szarzynski, J.; Tondini, S.; Vidal, J.d.D.; Membretti, A. Scrutinising Multidimensional Challenges in the Maloti-Drakensberg (Lesotho/South Africa). Sustain. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruchten, P. Contextualizing Agile Software Development. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2013, 25, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, C.; Abrantes, B.F. Strategic Adaption (Capabilities) and the Responsiveness to COVID-19’s Business Environmental Threats. In Essentials on Dynamic Capabilities for a Contemporary World; Abrantes, B.F., Madsen, J.L., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-3-031-34814-3. [Google Scholar]

- Calame, P.; Talmant, A.; et Chaussées, I.d.P. L’État Au Cœur: Le Meccano de La Gouvernance; Desclée de Brouwer: Paris, 1997; ISBN 2220040542. [Google Scholar]

- Lehn, K. Corporate Governance and Corporate Agility. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, A.J.; Kruchten, P.; Pedrosa, M.L.; Neto, H.R.; De Moura, H.P. State of the Art of Agile Governance: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2014, 6, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S. The Heart of the Enterprise. Chichester, UK al, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. Brain of the Firm, Chichester” 1981.

- Martinez-Lozada, A.C.; Espinosa, A. Corporate Viability and Sustainability: A Case Study in a Mexican Corporation. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2022, 39, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S. What Is Cybernetics? Kybernetes 2002, 31, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).