Introduction

Apoptosis (also known as programmed cell death) is a tightly regulated orderly process necessary for maintaining the homeostasis and development of tissues. It is an energy requiring biological process that plays a major role in mammary gland development and carcinogenesis, with specific morphological changes. These morphological changes include cell shrinkage, condensation of chromatin, membrane blebbing, fragmentation of nucleus and formation of apoptotic bodies [Kerr, 1972; Saraste, 1999; Elmore, 2007]. Abnormality in the regulation of apoptosis can lead to increased cell survival and is a key mechanism underlying tumorigenesis [Zubair, 2025].

BCL2 associated Athano-Gene 1 (BAG1) is a multifunctional protein that interacts with a wide range of target molecules to regulate apoptosis, proliferation, transcription, metastasis and motility and has attained considerable attention due to its potentially important role in several cancer types [Cutress, 2002; Townsend, 2003]. BAG1 can regulate both intrinsic and extrinsic pathway of apoptosis by interacting with diverse proteins like Bcl-2, RAF-1, Hsp70, and nuclear hormone receptors [Knee et al., 2001; Tang, 2002; Nguyen et al., 2020]. This regulatory diversity is contributed by the different localization of BAG1 isoforms, where Nuclear BAG1(BAG1L) enhance transcriptional activity, while cytoplasmic BAG1 isoforms regulate chaperone activity and apoptotic resistance [Liu et al., 2008; Cutress, 2002]. Several cancer types including lung cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, acute myeloid leukaemia and squamous cell carcinoma have reported an overexpression of BAG1, linking with unfavourable prognosis and resistance to chemotherapy [Aveic et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2008; Tang, 2002; Krajewska et al., 2006].

BAG1 has emerged as a potential therapeutic target due to its pivotal role in suppression of apoptosis and thereby progression of cancer. Recent studies show that silencing of BAG1 can enhance chemosensitivity of cells and restore apoptosis through modulation of BCL2 family proteins and caspase activation [Liu et al., 2010; Takahashi et al., 2003]. Thus, sensitizing cancer cells to apoptosis may achieved by selective inhibition of BAG1 protein

Natural compounds have long served as anti-cancer agents. Nigella sativa (Black cumin) is considered as a medicinal plant due to its diverse pharmacological properties [Salem, 2005; Khan & Afzal, 2016]. The phytocompounds present in Nigella sativa , notably thymoquinone (TQ), Fuzitine and α-hederin, are reported to have cytotoxic as well as pro-apoptotic properties, mostly by regulating genes related to the apoptosis, against various types of cancer cells [Farah, 2003; Gali-Muhtasib, 2004; Shafiq, 2014; Bourgou, 2010; Al-Sheddi, 2014]. Extracts from Nigella sativa has been also shown to inhibit the proliferation of MCF-7 cells in Breast Cancer significantly, demonstrating its potential in treating hormone-dependent malignancies [Shafiq, 2014].

At the same time, the advances in computational drug discovery and targeted drug therapy have expanded the potential to discover small molecules that can specifically bind to oncogenic proteins such as BAG1 and inhibit its activity. Targeted therapies have limited adverse effects since they disrupt tumour-promoting proteins with great precision in contrast to traditional chemotherapy, which effects both the cancerous and normal dividing rapidly cells [Padma, 2015].In this context, Molecular Docking serves as a crucial tool in structure-based drug discovery experiments by predicting the affinity, stability, and interaction profiles of Ligand-Protein Binding [Guedes et al., 2013; Agarwal & Mehrotra, 2016]. Particularly, AutoDock has been widely recognized as a reliable docking platform that offers both efficient high-throughput virtual screening of ligand binding conformations and its accurate modeling[Morris et al., 2009; El-Hachem et al., 2017].

Taken together, targeting BAG1 using natural product-based inhibitors such as those derived from Nigella sativa represents a promising therapeutic strategy. This study aims to explore the potential of N. sativa phytochemicals in inhibiting BAG1 through molecular docking simulations, providing mechanistic insights into their role as anti-cancer agents

Materials and Methods

Computational Tools

For computational works, a desktop computer having an active internet connection and adequate computational power to perform molecular modelling,docking and visualization was used. The mentioned softwares and online databases were employed inorder to aid the study: PubChem (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) for obtaining the three-dimensional structures and canonical SMILES of the selected phytochemicals; the Protein Data Bank (PDB;

https://www.rcsb.org/) inorder to aquire the crystal structure of the target protein; SwissADME (

http://www.swissadme.ch/) to screen the chemical compounds for pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness properties; PubMed and Google Scholar for literature collection; Discovery Studio (BIOVIA, Dassault Systèmes, USA) for protein and ligand preprocessing and visualization; the KNApSAcK database (

http://kanaya.naist.jp/KNApSAcK/) for verification of phytochemical composition; AutoDock 4.2 (The Scripps Research Institute, USA) for molecular docking simulations (Morris et al., 2009); and PyMOL for structural visualization and analysis (Schrödinger, LLC).

Methods

Selection and Preparation of the Target Protein

The crystal structure of the Bcl-2-associated athanogene 1 (BAG1) protein (PDB ID: 3M3Z) derived from Homo sapiens was selected as the target protein of study and was downloaded from PDB. . The structure was resolved by X-ray diffraction with a resolution of less than 3 Å and contained the co-crystallized natural ligand 5′-O-(2-amino-2-oxoethyl)-8-(methylamino)adenosine (C15H19N7O5). The structure was imported into Discovery Studio where it is subjected to preprocessing steps for removing the molecules, heteroatoms, and irrelevant side chains. The active binding cavity of the crystal structure containing the co-crystallized ligand (3F5) was identified and isolated for docking studies. The cleaned and optimized structure was saved in PDB format for further analyses.

Identification of Phytocompounds in Nigella sativa

The bioactive compounds reported in Nigella sativa identified through an extensive literature study done with the aid of Peer-reviewed articles, reviews, and books sourced primarily from PubMed (MEDLINE) and Google Scholar. Additional informations were collected from institutional libraries and the KNApSAcK phytochemical database, which provides a comprehensive list of naturally occurring metabolites. Phytocompounds with previously reported pharmacological activities were primarily considered for analysis. Their mechanisms of action and molecular targets were further explored based on published studies (Ahmad et al., 2013; Forouzanfar et al., 2014; Randhawa and Alghamdi, 2011).

Retrieval and Preparation of Ligands

The 3D structures of the selected phytochemicals were downloaded from the PubChem database in SDF format. These structures were converted into PDB format using Discovery Studio. Ligands were energy-minimized and checked for missing hydrogen atoms and bond order corrections to ensure proper geometry before docking

Protein Preparation for Docking

The preprocessed structure of BAG1 protein was loaded into AutoDock 4.2 for further preparationsa. To the protein structure, Polar hydrogen atoms were added (Edit → Hydrogen → Add → Polar Only), and Kollman charges were assigned (Edit → Charge → Add Kollman Charges). The prepared protein was saved in PDBQT format. This step ensured proper charge distribution and optimized configuration for grid and docking parameter generation

Ligand Preparation for Docking

Each and all of the ligands were imported into AutoDock Tools and configured as a flexible molecule. To each of the configured ligands Hydrogen atoms were added (Edit → Hydrogen → Polar Only), and Gasteiger partial charges were computed (Edit → Charge → Compute Gasteiger). The torsion tree was detected, and the number of rotatable bonds was optimized to allow conformational flexibility during docking. The final ligand files were saved in PDBQT format

Identification of Active Site Residues

The amino acid residues present in the Active site of BAG1 were identified based on structural analysis of the co-crystallized ligand and previously reported literature (Bimston et al., 1998). The amino acids forming the ligand-binding pocket were noted for generating grid box. This ensured that the docking simulations were restricted to the biologically relevant region of the protein.

Grid Generation and Parameter Setup

AutoDock’s Grid Module was used to create a three-dimensional grid box enclosing the active site amino acoid residues. The dimensions of the grid box and its center coordinates were adjusted to fully cover the active binding pocket. These parameters were stored in a Grid Parameter File (GPF). Docking parameters were then defined in a Docking Parameter File (DPF) using the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) as the search method. The number of GA runs was set to 360 to ensure comprehensive conformational sampling. Both the protein (rigid) and ligand (flexible) files were linked in the parameter files for execution.

Docking Simulations

Energy maps using the parameters specified in the GPF file was computed by executed the The AutoGrid program. Subsequently, docking simulations were carried out using AutoDock 4.2 with the DPF file as input. The optimal ligand orientations and conformations within the binding site was predicted using the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm. The docking log file (DLG) generated after completion contained information on all binding modes and their corresponding binding energies.

Analysis and Visualization of Docking Results

Docking results were analyzed by examining the DLG file for conformations with the lowest binding energy. Hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and π–π stacking between the ligand and active site residues were assessed by visualising the best-scoring conformations using AutoDock Tools and Discovery Studio. The most stable complexes were visualized in PyMOL, and interacting amino acid residues were labelled to highlight the binding interactions.

Post-Docking ADME/T Analysis

The canonical SMILES of the top-ranked ligands were retrieved from PubChem and analysed using the SwissADME web tool. Each compound was evaluated for pharmacokinetic parameters and toxicity predictions, including human intestinal absorption, aqueous solubility, blood–brain barrier permeability, hepatotoxicity, CYP2D6 inhibition, plasma protein binding, and lipophilicity (AlogP). Compounds with optimal pharmacokinetic and physicochemical characteristics were shortlisted as potential BAG1 inhibitors for further consideration.

Result

1. Molecular docking of 3m3z with 3F5

3F5 have a binding energy of -6.38 against BAG1 with a mean binding energy of -6.38 through the 360 runs and strong interactions of 5 hydrogen-bonds and 2 carbon-hydrogen. However there appears to be an unfavourable donor-donor clash between nitrogen (N25) of the ligand 3F5 and lysine (LYS A:271) amino acid residue of the protein BAG1

Table 1.

Binding Energy and Types of interactions between 3F5 and BAG1.

Table 1.

Binding Energy and Types of interactions between 3F5 and BAG1.

| SI NO. |

COMPOUND |

LOWEST BINDING ENERGY

(KCal/mol) |

NUMBER OF RUN |

MEAN BINDING ENERGY

(KCal/mol) |

TYPES OF INTERACTIONS

|

| FAVOURABLE |

UNFAVOURABLE |

| 1. |

3F5 |

-6.38 |

43 |

-6.38 |

Hydrogen Bond

2 Inter-molecular 3 Intra-molecular 2 Carbon-Hydrogen Bond |

1 Donor-Donor clash (LYS A:271-N45) |

2. Molecular docking of BAG1 with Nigella sativa phytochemicals

Out of 58 phytochemicals screened, molecular docking simulation identified 20 compunds showing greater binding affinity than that of 3F5 and are summarised in

Table 2. The complete docking result is provided in Appendix Table A1

When compared to all the phytochemicals derived from

Nigella sativa exhibiting lower binding energy than that of 3F5, Fuzitine demonstrated a binding energy of -7.17 and a mean binding energy of -6.68 towards BAG1 with strong interactions as shown in

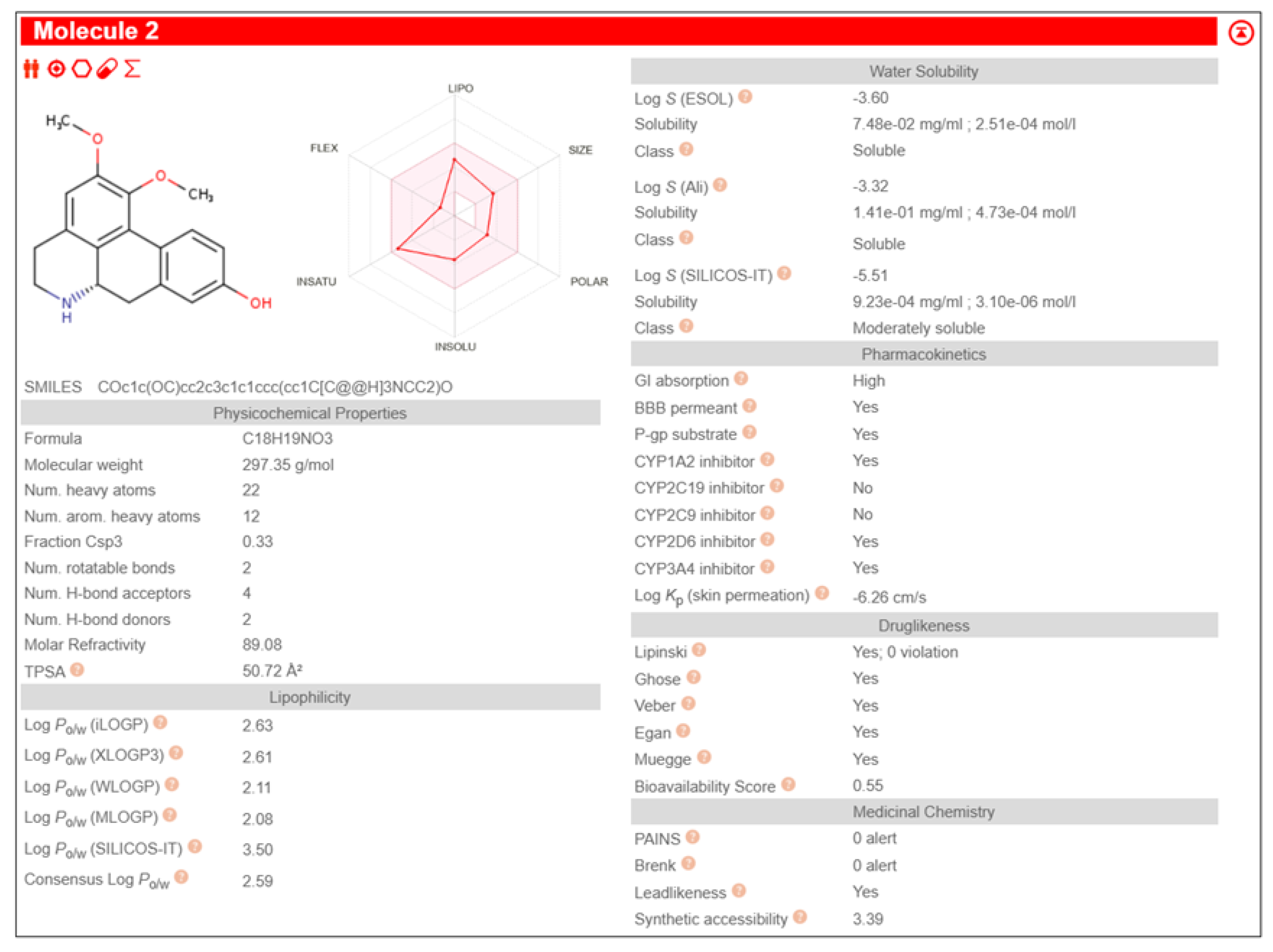

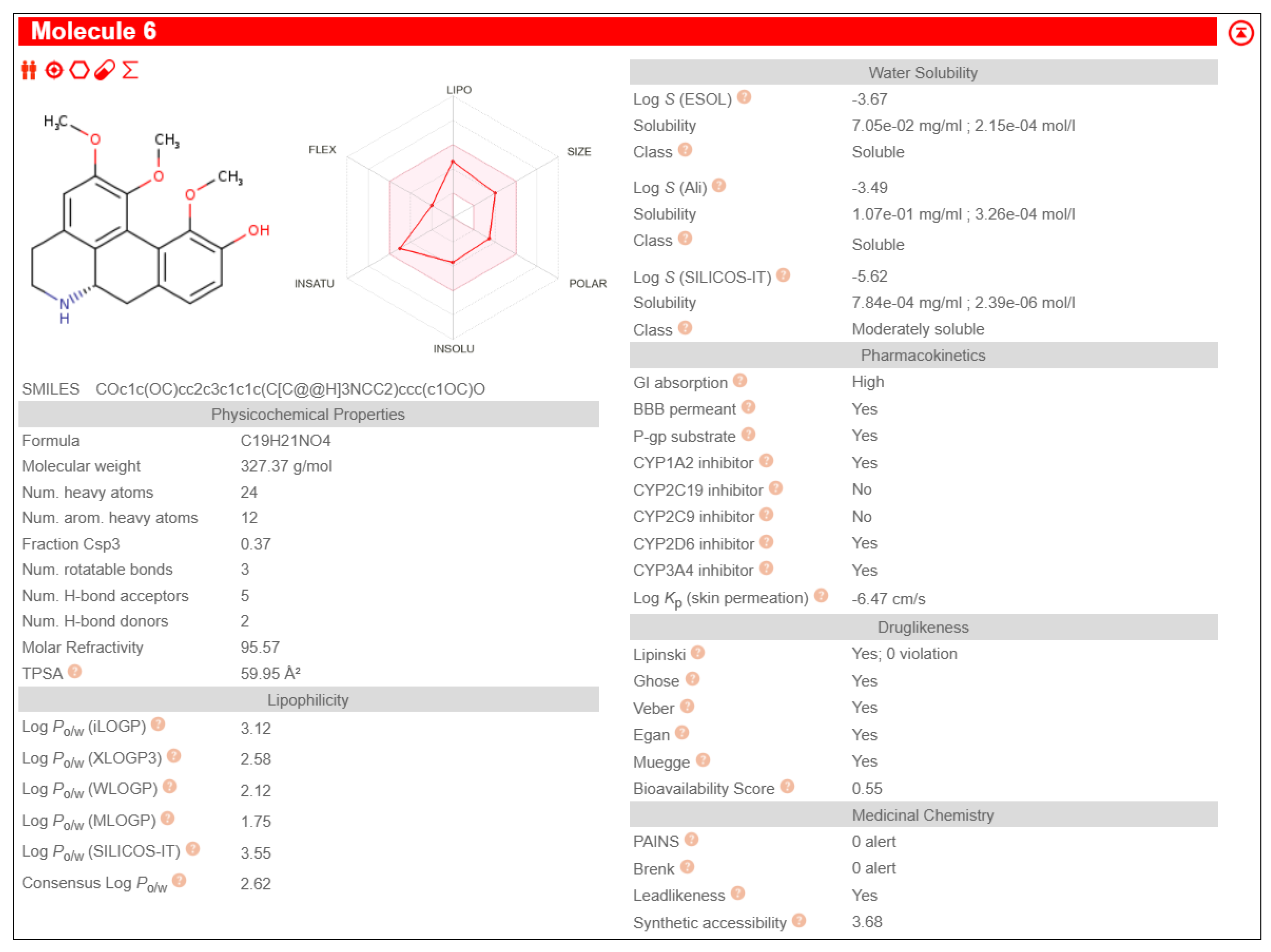

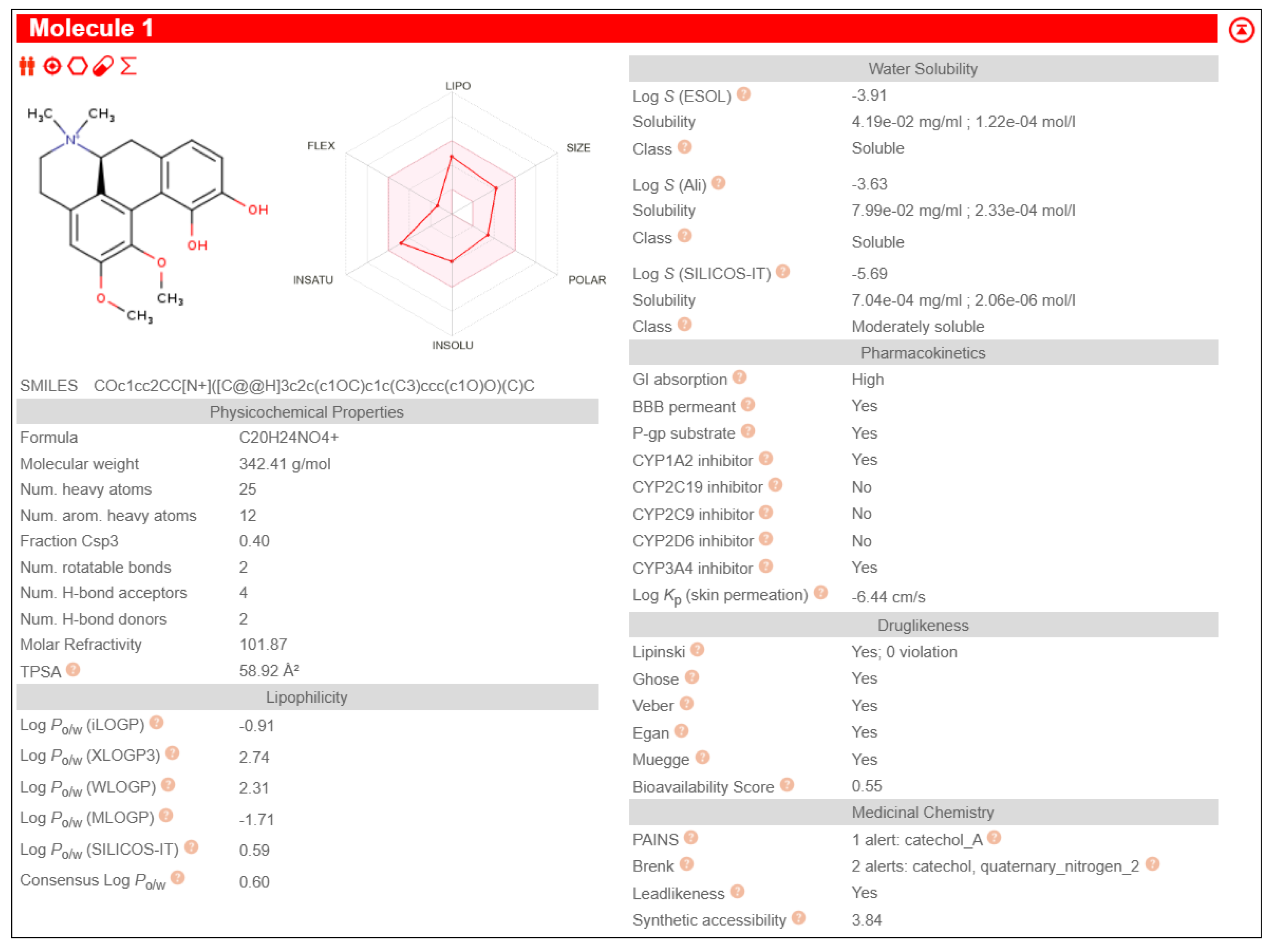

Table 3. It also exhibited pharmacological properties like high GI absorption, high aqueous solubility, low lipid content, no CYP2D6 inhibition and high brain-blood barrier permeability than other phytochemicals, shown in

Figure 1.

- 2.

Molecular Docking of BAG1 with Fuzitine homologues

The binding energy and types of iunteraction between top 5 fuzitine homologues and BAG1 are summarised in

Table 4

- 3.

Post-Docking ADME/T Analysis of selected Fuzitine homologues

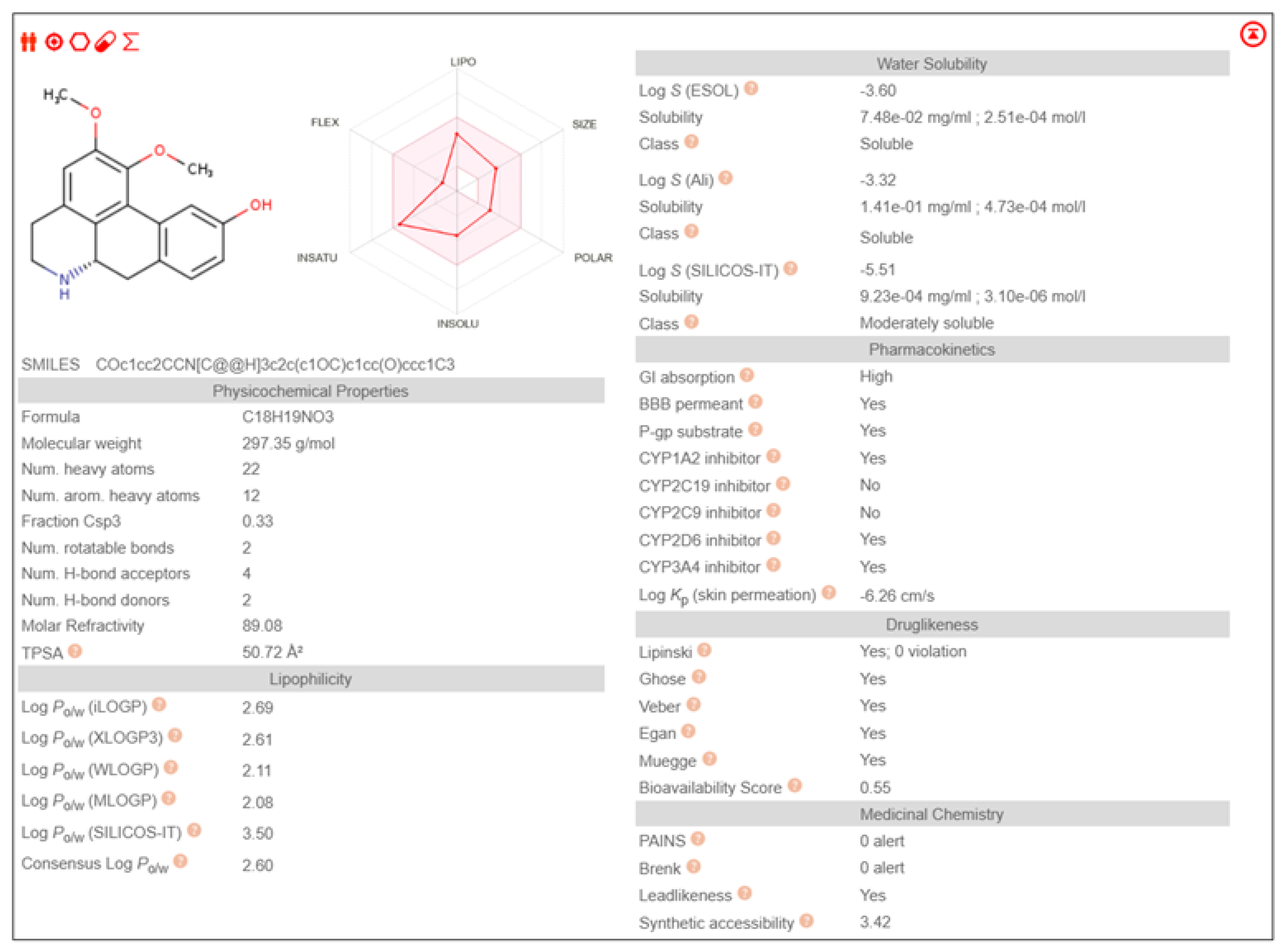

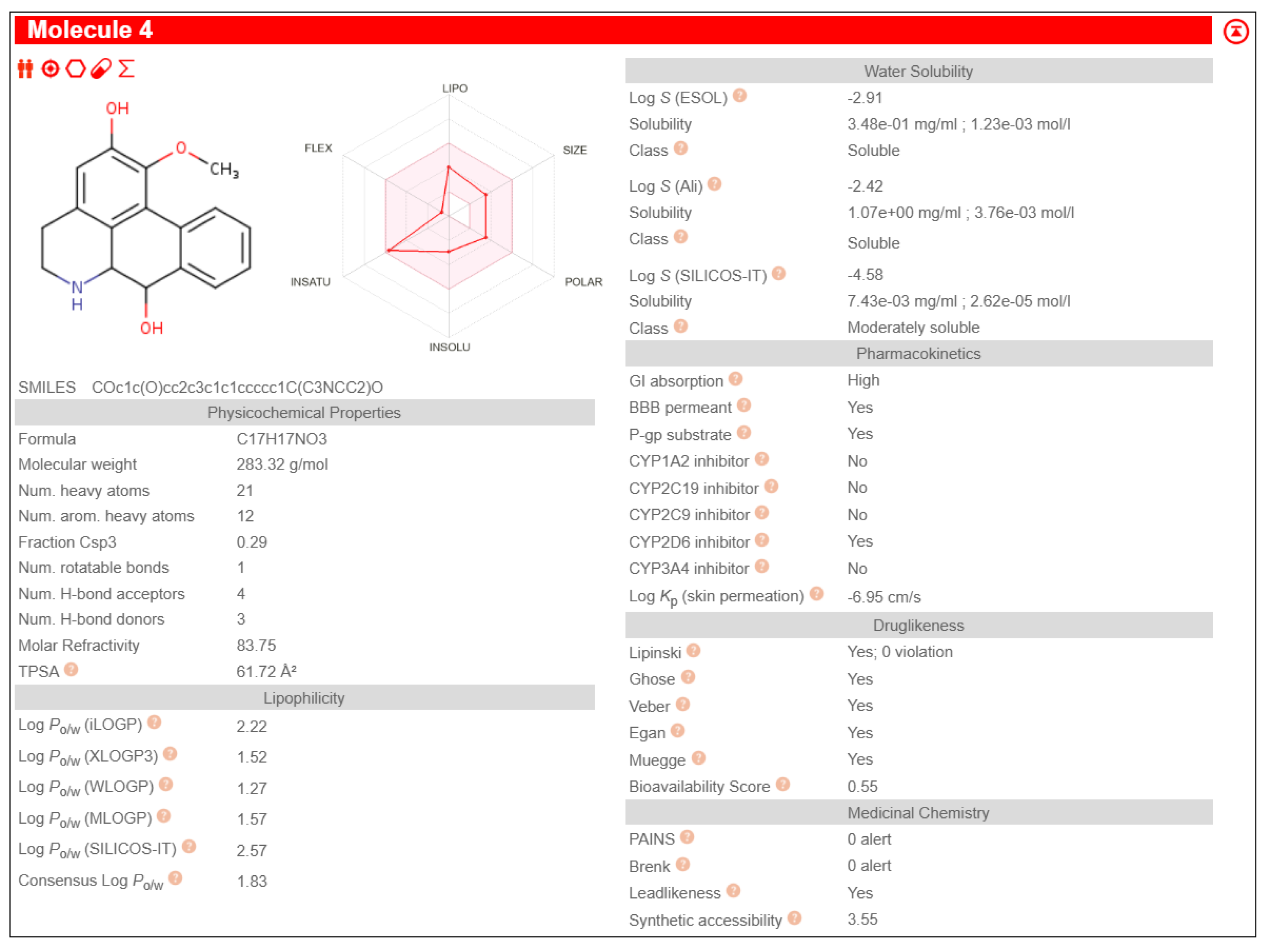

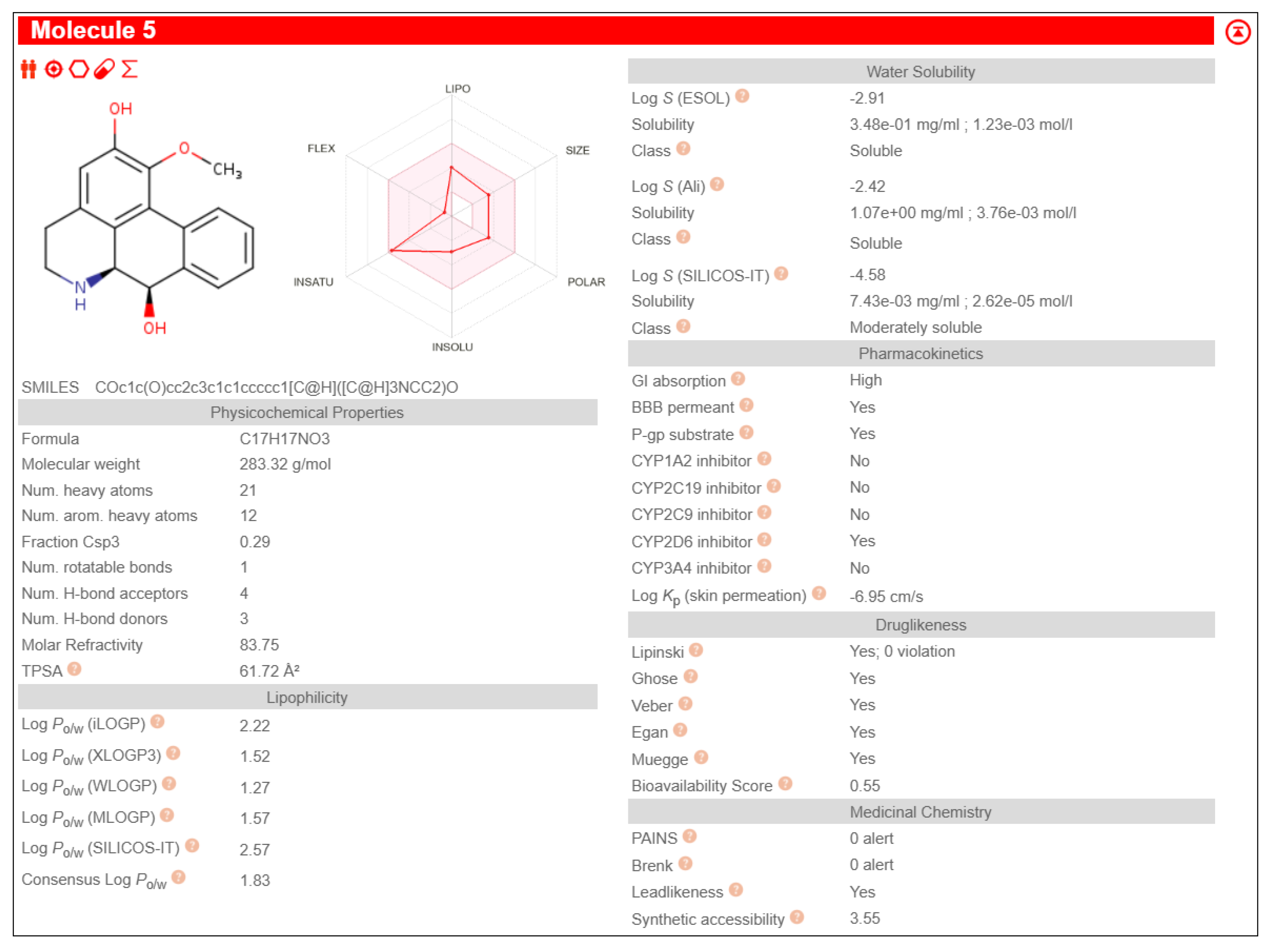

All the 5 Fuzitine homologues fulfilled the druglikeness , with all the compounds showing high G1 absorption and no P-gp substrate activity. Among them, Anaxagoreine exhibited Brain-Blood Barrier Permeability. The data is summarised in

Table 5. The detailed ADME/T analysis report is given in Appendix

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3,

Figure A4 and

Figure A5

Discussion

Overexpression of BAG-1 suppresses activation of caspases and apoptosis induced by a very broad range of agents like chemotherapeutic agents, radiation and growth factor withdrawal in different cell types. Therefore, in addition to contributing negative regulation of apoptosis in cancer development, BAG-1 may also contribute to resistance to important therapeutic modalities.

All BAG inhibitor identified so far are not approved by the FDA. Targeted therapy using BAG1 inhibitors will inhibit the cancer cell’s ability to resist apoptosis and can be used along with chemotherapeutic treatments to increase its efficiency in destroying cancer cells.

I conducted study using phytocompounds derived from Nigella sativa, which has been described to have several therapeutic properties. To analyze the sensitivity of BAG 1 towards the phytocompounds, molecular docking of each molecule was conducted and further filtered top performing candidates through ADME/T analysis to determine their potential as therapeutic drugs and I found that one of the phytochemical Fuzitine performed well in both.

The study was further proceeded by identifying and screening Fuzitine homologues that showed greater affinity to BAG1 than that of Fuzitine in inhibiting its action and found five potential dibenzoquinoline derivative Fuzitine homologue compounds that showed greater affinity to BAG1 with favourable pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness properties.

6aS)-1,2-dimethoxy-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline-9-ol exhibited high Gastro-Intestinal absorption, low BBB permeability and no P-gp substrate activity, which aid in longer systemic retention in cells. This suggests a stable pharmacokinetic profile. On special note, it does not inhibit any of the major CYP450 enzymes, which is beneficial in reducing the risks of drug-drug interactions during combined drug therapies. It also satisfies all five drug likeness filters (Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Egan, and Muegge), making it a potentially strong candidate for oral drug development without targeting the Central Nervous System (CNS)

(6aS)-1,2-dimethoxy-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline-10-ol showcased high Gastro-Intestinal absorption and low BBB permeability, indicating its potential for applications in peripheral therapeutics. It does not show any P-gp substrate activity but inhibited CYP1A2. This indicates the possibilities of interactions with the co-administered drugs metabolized through its pathway during combined drug therapies. Its exhibit moderate skin permeability while satisfying all five major drug likeness profiles, making it as a potentially viable lead compound for oral formulations with little CNS activity.

Anaxagoreine displayed high GI absorption and capability to permeate the BBB, suggesting its potential suitability as drug in CNS-targeted treatments and therapies. It does not have any P-gp substrate activity, aiding longer availability in the cells. However, it inhibits CYP1A2 as well as CYP2C19, which may increase to possibilities of drug-drug metabolic interactions during combined drug therapies. It’s permeability through skin (Log Kp: –5.38 cm/s) backs its pharmacokinetic qualities. It also fulfils all five major drug likeness rules, making it a promising candidate especially in conditions that requires CNS penetration.

4H-Dibenzo[de,g]quinoline-2,7-diol, 5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-1-methoxy-, (6aS,7R)- showed high GI absorption, no BBB permeability and no P-gp substrate activity. It inhibits CYP1A2 leading to the possibility of metabolic interactions during multi-drug treatments. Its skin penetration value (Log Kp: –5.98 cm/s) indicate a moderate absorption. It satisfies all the five major drug likeness criteria, supporting its potential as an orally incorporable therapeutic agent.

(6aS)-1,2,11-trimethoxy-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline shows high GI absorption, no BBB permeability and no P-gp substrate activity. It also showed no inhibition of any major CYP450 enzymes, indicating little to no drug-drug interactions. The molecule complies with all five major drug-likeness profiles.

To wrap up, Research on BAG as a target protein for inhibiting cancer development has been actively pursued in recent years. The Binding Energy significantly lower that its natural ligand 3F5 showed the interference of Fuzitine homologues inhibiting the proteins action. My study revealed five dibenzoquinoline Fuzitine homologues having more affinity and specificity to BAG1 than the rest and also have potential pharmacological properties, especially due to their Blood-Brain Barrier permeability and drug likeness. The Molecular Docking results along with the ADME/T profiles of these Dibenzoquinoline derivatives support the further investigation to determine if the dibenzoquinoline derivatives can be a potential drug to inhibit anti apoptotic property of cancer cell and increase the success rate of cancer treatments by promoting apoptosis of cancer cell., especially in preclinical and clinical studies aiming to develop novel anticancer as well as neuroactive agents.

Appendix A. Complete Molecular Docking Result

Table A1.

Complete molecular docking result of 58 phytochemicals derived from Nigella sativa with BAG1.

Table A1.

Complete molecular docking result of 58 phytochemicals derived from Nigella sativa with BAG1.

| SI NUMBER |

COMPOUND |

LOWEST BINDING ENERGY |

NUMBER OF RUN |

MEAN BINDING ENERGY |

| 1 |

24-Methylenecycloartan-3beta-ol |

-9.69 |

93 |

-9.25 |

| 2 |

(3beta,5alpha)-Stigmastan-3-ol |

-9.13 |

96 |

-8.75 |

| 3 |

(-)-Butyrospermol |

-9.11 |

74 |

-8.53 |

| 4 |

beta-Stigmasterol |

-8.83 |

120 |

-8.19 |

| 5 |

24-Ethylidenelophenol |

-8.83 |

120 |

-8.19 |

| 6 |

Nigellamine C |

-8.82 |

33 |

-8.80 |

| 7 |

Lophenol |

-8.74 |

52 |

-8.37 |

| 8 |

Obtusifoliol |

-8.74 |

52 |

-8.22 |

| 9 |

Tirucallol |

-8.69 |

87 |

-8.20 |

| 10 |

Gramisterol |

-8.16 |

100 |

-8.13 |

| 11 |

Nigellone |

-7.95 |

16 |

-7.48 |

| 12 |

Taraxerol |

-7.69 |

40 |

-7.68 |

| 13 |

beta-Amyrin |

-7.55 |

111 |

-7.54 |

| 14 |

Cholesterol |

-7.54 |

10 |

-7.54 |

| 15 |

Fuzitine |

-7.41 |

58 |

-7.22 |

| 16 |

Nigellidine |

-7.05 |

72 |

-6.97 |

| 17 |

Nigellicine |

-6.85 |

18 |

-5.91 |

| 18 |

Quercetin |

-6.78 |

87 |

-5.98 |

| 19 |

Junosmarin |

-6.65 |

68 |

-6.58 |

| 20 |

Nigellamine A1 |

-6.52 |

20 |

-6.34 |

| 21 |

Quercetin 3-(6′’’’-feruloylglucosyl)-(1->2)-galactosyl-(1->2)-glucoside |

-6.30 |

9 |

|

| 22 |

Salfredin B11 |

-6.30 |

9 |

-5.82 |

| 23 |

alpha-Longipinene |

-6.21 |

29 |

-6.20 |

| 24 |

Longifolene |

-6.05 |

56 |

-6.04 |

| 25 |

Nigeglanine |

-5.77 |

96 |

-5.76 |

| 26 |

Nigellimine |

-5.56 |

9 |

5.51 |

| 27 |

Fenchone |

-5.44 |

77 |

-5.44 |

| 28 |

Apiol |

-5.43 |

113 |

-5.33 |

| 29 |

2,5-Dihydroxy-p-cymene |

-5.39 |

117 |

-5.21 |

| 30 |

Thymoquinone |

-5.39 |

49 |

-5.22 |

| 31 |

Myristicin |

-5.28 |

50 |

-5.24 |

| 32 |

Linoleic acid |

-5.23 |

51 |

-4.08 |

| 33 |

4-Terpineol |

-5.13 |

92 |

-5.04 |

| 34 |

Dihydrocarvone |

-5.11 |

64 |

-5.02 |

| 35 |

alpha-Phellandrene |

-5.10 |

56 |

-4.93 |

| 36 |

Cycloartenol |

-5.10 |

74 |

-5.02 |

| 37 |

m-Thymol |

-5.08 |

49 |

-5.05 |

| 38 |

Cycloeucalenol |

-5.00 |

90 |

-5.00 |

| 39 |

4(10)-Thujene |

-4.99 |

71 |

-4.78 |

| 40 |

Carvone |

-4.97 |

98 |

-4.97 |

| 41 |

4-Methoxythujane |

-4.90 |

63 |

-4.85 |

| 42 |

alpha-Pinene |

-4.65 |

36 |

-4.65 |

| 43 |

p-Cymene |

-4.54 |

31 |

-4.46 |

| 44 |

alpha-Thujene |

-4.47 |

64 |

-4.41 |

| 45 |

beta-Pinene |

-4.47 |

22 |

-4.41 |

| 46 |

Anisaldehyde |

-4.46 |

66 |

-4.44 |

| 47 |

gamma-Terpinene |

-4.36 |

29 |

-4.29 |

| 48 |

Carvacrol |

-4.34 |

70 |

-4.39 |

| 49 |

Estragol |

-4.16 |

9 |

-4.15 |

| 50 |

beta-Myrcene |

-3.90 |

61 |

-3.71 |

| 51 |

Lauric acid |

-3.89 |

51 |

-3.46 |

| 52 |

alpha-Linolenic acid |

-3.65 |

18 |

-3.51 |

| 53 |

7-Octadecenoic acid |

-3.47 |

98 |

-3.23 |

| 54 |

Nonane |

-3.21 |

49 |

-3.03 |

| 55 |

Butyl propyl disulfide |

-2.83 |

50 |

-2.66 |

| 56 |

Nigellamine A2 |

-0.02 |

43 |

0.06 |

| 57 |

Nigellamine B1 |

1.52 |

38 |

1.68 |

| 58 |

Nigellamine B2 |

1.78 |

45 |

1.93 |

Appendix B. Detailed ADME/T Analysis

Figure A1.

ADME/T ANALYSIS OF (6aS)-1,2-dimethoxy-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline-9-ol.

Figure A1.

ADME/T ANALYSIS OF (6aS)-1,2-dimethoxy-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline-9-ol.

Figure A2.

ADME/T ANALYSIS OF (6aS)-1,2-dimethoxy-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline-10-ol.

Figure A2.

ADME/T ANALYSIS OF (6aS)-1,2-dimethoxy-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline-10-ol.

Figure A3.

ADME/T ANALYSIS OF Anaxagoreine.

Figure A3.

ADME/T ANALYSIS OF Anaxagoreine.

Figure A4.

ADME/T ANALYSIS OF 4H-Dibenzo(de,g)quinoline-2,7-diol, 5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-1-methoxy-, (6aS,7R)-.

Figure A4.

ADME/T ANALYSIS OF 4H-Dibenzo(de,g)quinoline-2,7-diol, 5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-1-methoxy-, (6aS,7R)-.

Figure A5.

ADME/T ANALYSIS OF (6aS)-1,2,11-trimethoxy-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline.

Figure A5.

ADME/T ANALYSIS OF (6aS)-1,2,11-trimethoxy-5,6,6a,7-tetrahydro-4H-dibenzo[de,g]quinoline.

References

- Agarwal, S., & Mehrotra, R. (2016). An overview of Molecular Docking. JSM Chemistry.

- Ahmad, A., Husain, A., Mujeeb, M., Khan, S. A., Najmi, A. K., Siddique, N. A., Damanhouri, Z. A., & Anwar, F. (2013). A review on therapeutic potential of Nigella sativa: A miracle herb. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 3(5), 337–352. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sheddi, E. S., Farshori, N. N., Al-Oqail, M. M., Musarrat, J., Al-Khedhairy, A. A., & Siddiqui, M. A. (2014). Cytotoxicity of Nigella sativa seed oil and extract against human lung cancer cell line. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 15(2), 983–987. [CrossRef]

- Aveic, S., Pigazzi, M., & Basso, G. (2011). BAG1: The Guardian of Anti-Apoptotic proteins in acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS ONE, 6(10), e26097. [CrossRef]

- Bimston, D., Song, J., Winchester, D., Takayama, S., Reed, J. C., & Morimoto, R. I. (1998). BAG-1, a negative regulator of Hsp70 chaperone activity, uncouples nucleotide hydrolysis from substrate release. The EMBO Journal, 17(23), 6871–6878. [CrossRef]

-

Black cumin (Nigella sativa) and its constituent (thymoquinone): a review on antimicrobial effects. (2014, December 1). PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25859296/.

- Bourgou, S., Pichette, A., Marzouk, B., & Legault, J. (2009). Bioactivities of black cumin essential oil and its main terpenes from Tunisia. South African Journal of Botany, 76(2), 210–216. [CrossRef]

- Cutress, R. I., Townsend, P. A., Brimmell, M., Bateman, A. C., Hague, A., & Packham, G. (2002). BAG-1 expression and function in human cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 87(8), 834–839. [CrossRef]

- El-Hachem, N., Haibe-Kains, B., Khalil, A., Kobeissy, F. H., & Nemer, G. (2017). AutoDock and AutoDockTools for Protein-Ligand docking: Beta-Site Amyloid precursor Protein Cleaving Enzyme 1(BACE1) as a case study. Methods in Molecular Biology, 391–403. [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. (2007). Apoptosis: A review of Programmed Cell Death. Toxicologic Pathology, 35(4), 495–516. [CrossRef]

- Farah, I. O., & Begum, R. A. (2003). Effect of Nigella sativa (N. sativa L.) and oxidative stress on the survival pattern of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Biomedical Sciences Instrumentation, 39, 359–364. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12724920.

- Gali-Muhtasib, H., Diab-Assaf, M., Boltze, C., Al-Hmaira, J., Hartig, R., Roessner, A., & Schneider-Stock, R. (2004). Thymoquinone extracted from black seed triggers apoptotic cell death in human colorectal cancer cells via a p53-dependent mechanism. International Journal of Oncology, 25(4), 857–866. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15375533.

- Guedes, I. A., De Magalhães, C. S., & Dardenne, L. E. (2013). Receptor–ligand molecular docking. Biophysical Reviews, 6(1), 75–87. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J. F. R., Wyllie, A. H., & Currie, A. R. (1972). Apoptosis: A Basic Biological Phenomenon with Wideranging Implications in Tissue Kinetics. British Journal of Cancer, 26(4), 239–257. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., & Afzal, M. (2016). Chemical composition of Nigella sativa Linn: Part 2 Recent advances. Inflammopharmacology, 24(2–3), 67–79. [CrossRef]

- Knee, D. A., Froesch, B. A., Nuber, U., Takayama, S., & Reed, J. C. (2001). Structure-Function analysis of BAG1 proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276(16), 12718–12724. [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, M., Turner, B. C., Shabaik, A., Krajewski, S., & Reed, J. C. (2006). Expression of BAG-1 protein correlates with aggressive behavior of prostate cancers. The Prostate, 66(8), 801–810. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Bai, Y., Liu, B., Wang, Z., Wang, M., Zhou, Q., & Chen, J. (2008). [The expression of BAG-1 and its clinical significance in human lung cancer.]. DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals), 11(4), 489–494. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Liang, Y., Li, Y., Li, Y., Wang, J., Wu, H., Wang, Y., Tang, S., Chen, J., & Zhou, Q. (2010). Gene silencing of BAG-1 modulates apoptotic genes and sensitizes lung cancer cell lines to cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Cancer Biology & Therapy, 9(10), 832–840. [CrossRef]

- Morris, G. M., Huey, R., Lindstrom, W., Sanner, M. F., Belew, R. K., Goodsell, D. S., & Olson, A. J. (2009). AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 30(16), 2785–2791. [CrossRef]

- Morris, G. M., Huey, R., Lindstrom, W., Sanner, M. F., Belew, R. K., Goodsell, D. S., & Olson, A. J. (2009). AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 30(16), 2785–2791. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P., Hess, K., Smulders, L., Le, D., Briseno, C., Chavez, C. M., & Nikolaidis, N. (2020). Origin and evolution of the human BCL2-Associated athanogene-1 (BAG-1). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(24), 9701. [CrossRef]

- Padma, V. V. (2015). An overview of targeted cancer therapy. Biomedicine, 5(4). [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, M. A., & Alghamdi, M. S. (2011). Anticancer Activity of Nigella sativa (Black Seed) — A Review. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine, 39(06), 1075–1091. [CrossRef]

- Salem, M. L. (2005). Immunomodulatory and therapeutic properties of the Nigella sativa L. seed. International Immunopharmacology, 5(13–14), 1749–1770. [CrossRef]

- Saraste, A. (1999). Morphologic criteria and detection of apoptosis. Herz, 24(3), 189–195. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0.

- Shafiq, H., Ahmad, A., Masud, T., & Kaleem, M. (2014). Cardio-protective and anti-cancer therapeutic potential of Nigella sativa. Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, 17(12), 967–979. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25859300.

- Takahashi, N., Yanagihara, M., Ogawa, Y., Yamanoha, B., & Andoh, T. (2003). Down-regulation of Bcl-2-interacting protein BAG-1 confers resistance to anti-cancer drugs. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 301(3), 798–803. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S. (2002). BAG-1, an Anti-Apoptotic Tumour marker. IUBMB Life, 53(2), 99–105. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, P. A., Cutress, R. I., Sharp, A., Brimmell, M., & Packham, G. (2003). BAG-1: a multifunctional regulator of cell growth and survival. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer, 1603(2), 83–98. [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M., & Bokhari, S. R. A. (2025, April 12). Apoptosis. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499821/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).