2. Characteristics of the Regional Architecture of the Beskid Mountains

The beginnings of the development of the regional architecture of the Polish Beskids can be dated to their colonization in the 16th and 17th centuries by a small population arriving from Upper Silesia and pastoral settlers of Vlach origin, who arrived from the southeastern Carpathians. The Vlachs, whose exoethnonym refers to a people speaking a Romance language, were ethnically diverse South Balkan tribes, probably of Illyrian and Thracian origin. After the Slavs occupied the Balkans, the Vlach population, who had inhabited areas of Romania, Moldova, and Bulgaria, mostly moved to the less attractive mountainous regions [

5]. They also adopted a relatively simple, pastoral way of life engaged in sheep and cattle breeding. The colonization of the Polish Beskids occurred in multiple stages and gradually contributed to the development of pastoralism, which, above all, gave rise to the regional architecture characteristic of the area. The mutual, long-term interaction of Polish and Vlach cultures ultimately shaped a new cultural quality in the development of local architecture, which has many features in common with both Carpathian building styles and the architecture typical of other regions of Poland.

Living needs, probably the most easily identifiable of the needs that influence spatial development, clearly follow geographical conditions, including landforms, access to fresh water, and climate [

6]. The traditional architecture of the region’s wooden houses was therefore designed to suit the region’s mountainous terrain, harsh climate, and pastoral way of life. The most iconic features of these buildings are the use of pine, fir, spruce, and larch wood [

7], as well as the steep, high-pitched gable roofs with overhanging eaves that helped protect the wooden walls from heavy rain and snow and provide a dry area around the house over a relatively low ground floor. These solutions protect the wooden houses from the strong winds common in the region and conserve heat in the interiors.

The gradually evolving functional plan of wooden houses [

8] was based on a rectangular layout divided in the middle by an entrance hall (

sień), sometimes augmented with two utility rooms or a

zachata (annex). Their layout was characterized by the symmetry of their arrangement relative to this hall [

9,

10], albeit of a historically questioned origin [

11]. This layout not only met the needs of the Beskid inhabitants but was also economically feasible. A characteristic feature of the buildings erected in this style was the use of relatively cheap, easily accessible [

12], and, when properly protected, durable building materials.

River stone was most commonly used for the foundations. At the same time, other structural elements were made from locally sourced coniferous wood—uncured spruce or pine hewn into beams with variable cross-sections—either round

okrąglaki (logs); semi-round

połowizny (halved logs); or nearly quadrilateral,

obliny (adzed logs). Oak wood was also used for building sill plates (

podwaliny) and sometimes other essential structural elements. Wooden cottages were built using log construction, which is formed from individual logs [

13,

14] joined at the corners using dovetail, half-lap, or simple butt joints. As Szymanowska-Gwiżdż [

15] claims based on visitation records from the 18th century, log construction is considered native to Polish Silesia as well. The corners were often adorned with decorative elements protruding beyond the edges of the walls, so-called

ostatki (log ends), which also provided a stiffening function. The

ostatki, if not cut to the same length, were often short for the lower logs and longer for the upper logs to create the effect called

rysie (extended corner logs), which acted as a corner bracket for the roof. Moss, oakum, or straw was inserted between the logs for insulation; these materials were often twisted into “braids” and also constituted an essential decorative element for the wall.

The gables of the buildings were boarded up with wooden planks, which were arranged vertically, horizontally, diagonally, or in a herringbone pattern. In rare cases, two types of layout were combined for each gable; for example, vertical boarding for the lower half of the gable, with diagonal boarding above. Vertically arranged gable boards extended beyond the wall surface, and their ends often featured a decorative finish. In such cases, they were separated by a second, upper pediment, called a przystrzeszka (small roof overhang). At the end of the gables, at the point of contact with the eaves, additional boards (sometimes richly decorated) were attached to prevent water from entering the building and to hold back the wind.

Hipped-gable or gable roofs were most commonly used in the regional architecture of the Beskid Mountains [

16]. The upper part of the roof, based on a truss made in the rafters or collar-tie construction, often had a steeper pitch than the lower part that was located closer to the eaves. The rafters could also be reinforced from underneath with diagonally attached boards or battens, called

wiatrownice (wind braces), which reinforced the entire roof structure in the longitudinal direction.

Traditionally, the roof was covered with wooden shingles, with one side overlapping and the other joined using a tongue-and-groove method. These shingles tend to be several dozen centimeters long and a dozen or so centimeters wide, with very diverse durability depending on the wood species (the best ones are without knots), the method and period of their preparation, and the state of drying. Shingles, locally called

szyndzioły, were made by cutting or splitting (

szczypanie) wood with an axe along the natural grain. This results in small boards with a triangular cross-section, called split shingles or shakes, which are characterized by increased durability compared to sawn shingles. The shingles created this way were originally nailed with wooden pegs (although now metal nails are generally used) to wooden battens [

17].

Architectural detail, although relatively sparse in the oldest rural cottages, often appeared as sculptural decorations on structural elements that were visible inside the buildings, such as ceiling beams. In cottages located in village centers, however, the architectural detail was noticeably richer. The rising sun placed on the gables was a common Beskid decorative motif, similar to the Podhale region; this motif is prevalent throughout Slavic architecture and occurs practically throughout Slavic territory, as well as in lands subjected to Slavic cultural influences, including continental Greece. Four- or six-pane—as well as rare two-pane windows—frames and shutters, doors, and wooden cornices were also often decorated.

A particularly popular decorative motif was based on the varied shapes and sizes of holes in the boards; this was used in many, diverse applications such as illuminating the attic. Regional architectural detail reached its most complete and perfect expression in the wooden houses built in the 19th century were often two-story; they frequently featured richly decorated

gible (projecting gable-end structures or “noses”) placed on the front side, which housed a porch on the ground floor and additional rooms in the attic (

Figure 1).

A specific element of regional construction was—and still is—their interior furnishings. This includes the furniture and items that can be used today, as well as those that only have museum significance. The first group of items, often undergoing renovation, includes wooden, often historic beds, as well as wooden tables (occasionally inlaid) and chairs, painted wooden chests, and stoves, including bread ovens. In the second group, we can include extremely attractive historic agricultural tools and numerous everyday objects made of wood and metal. Properly preserved, they take on new meaning and help to consolidate the cultural identity of the Polish Beskids. Although the application of all of these functional or aesthetic solutions directly in modern recreational architecture is neither necessary nor possible [

18], as has become increasingly visible in the architectural landscape of the Beskid Mountains [

19], their significance lies in the conscious use of chosen elements to continue the tradition and spirit of the region and thus to preserve the culture of the place.

3. Between Tradition and Modern Needs: Recreational Architecture

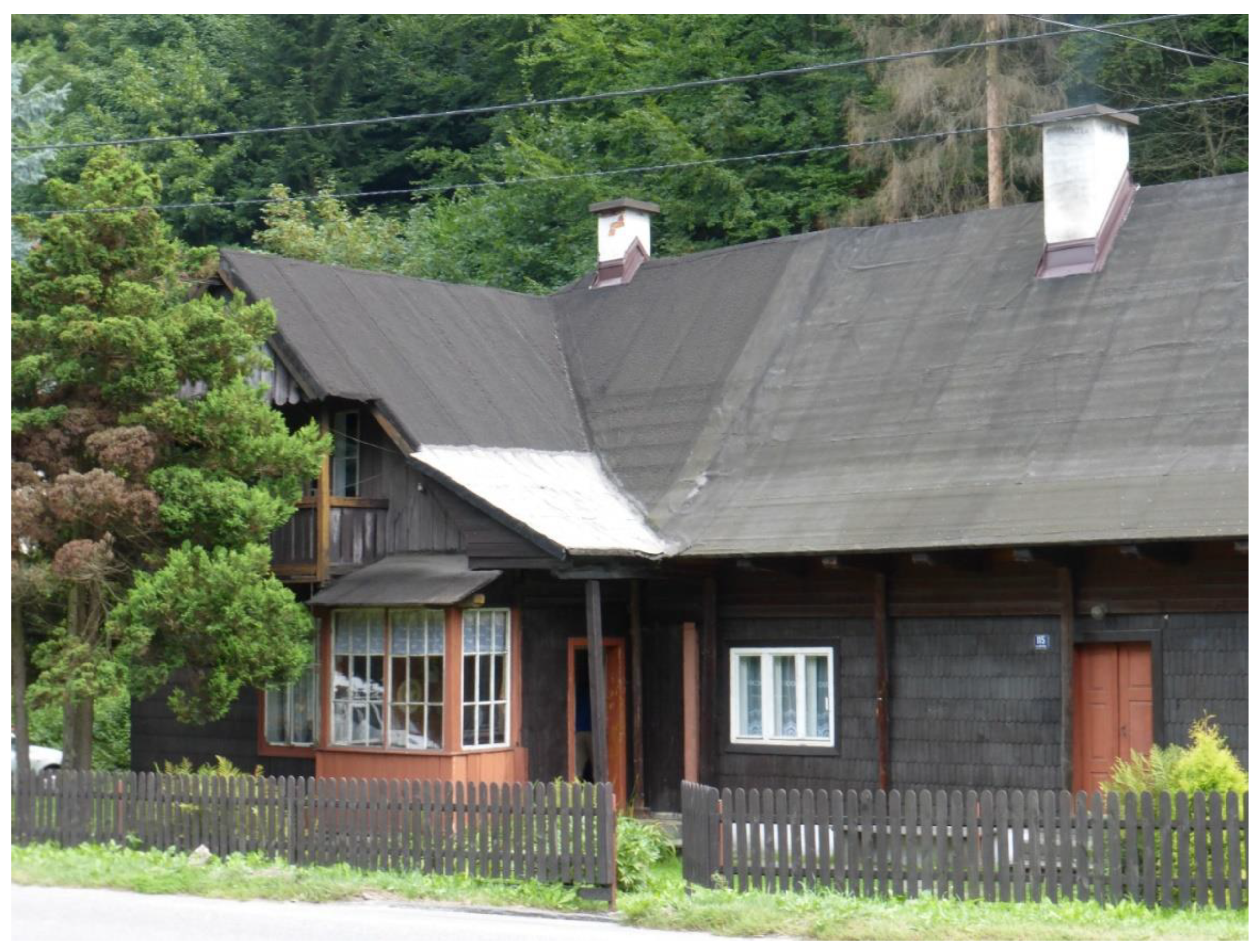

The development of recreational construction in southern Poland has included the location of new buildings and the adaptation of existing buildings, often of significant aesthetic value, from the beginning. In the adaptation of existing buildings, the fundamental values of regional architecture are usually preserved—or at least the shape of the building, the pitch of the roof, or, in most cases, the color scheme. Any repairs to these wooden cottages tend to be carried out due to progressive wood deterioration but require relatively small financial outlays. More serious interventions, such as replacing the truss or other structural elements, are more expensive. Nevertheless, this type of construction continues to contribute significantly to the preservation of regional traditions, although it is not the state but the educated social strata that take the role of cultural patrons, as they tend to be aware of the value of the often historic objects being renovated and adapted (

Figure 2).

However, it should be noted that adapting regional buildings for the needs of modern users often leads to aesthetic conflicts. A common issue is replacing the original wooden roof. This is often associated with the use of alternative materials such as colorful painted sheet metal. Ad hoc repairs are also frequently employed, most commonly through the application of one or more layers of roofing felt. This contributes to the creation of a color-inconsistent landscape, which is particularly visible from higher elevations or houses. Consistent landscape protection at the local government level could, however, help prevent this. A similar situation occurs with chimneys, which are often not plastered but instead faced with various types of tiles, which also disrupts the local color scheme, so chimneys in the Beskid region now appear to be notably different from each other.

The current needs of recreational building owners also include the use of more traditional as well as modern utilities. Despite many advantages, such as making it possible to spend more time outside the city or to work remotely thanks to internet access, the use of utilities, including television, is a source of many problems that affect not only well-being but also aesthetics. For example, there are now numerous antennas placed on wooden elevations and roofs, which reduces the aesthetic level of their architecture. The solution to this problem would be the use of modern collective receiving systems or completely or partially abandoning such devices in regional buildings adapted for recreational use.

Windows and doors are essential elements of regional construction. When regional buildings are adapted, these features are often replaced with joinery or metalwork that not only does not reference their prototypes in terms of color or material but also feature different proportions, divisions (in the case of windows), or opening methods. They also tend to lack the frequent Beskid practice of boarding with various patterns, including the rising sun motif on doors. New doors with an arched or, most commonly, rectangular lintel also lack the high thresholds characteristic of regional Beskid construction, which were originally made from the lowest log beams and intended to protect the interior from the incursion of rain or snow. It would be more appropriate for the original wooden joinery to be replaced based on the previous state, while preserving the color, shape, opening method, and decoration of doors and window divisions. In some cases, the renovation of old, wooden joinery is also possible. This often allows for the preservation of original shutters and even part of the interior fittings, although these usually require thorough renovation. However, most often, the most effective and economically justified solution is the replacement of the preserved but seriously damaged joinery elements with new pieces based on the existing ones and made from the same material. This approach prevents the introduction of foreign forms into the existing building and helps to preserve architectural harmony.

The constantly improved method of conservation technology remains a serious issue that constitutes a problem in the case of historic wooden constructions. Due to the poor technical condition of many these objects, which have both biotic and non-biotic sources, it is necessary to use hydrophobic agents in the renovation process to strengthen the wood tissue, as well as stabilizing agents to enable the preservation of historic wooden elements that are quite often heavily damaged [

20].

Another type of recreational construction, popular especially in the Beskids in the 1970s, is now less widespread. These were small or medium-sized (

Figure 3) wooden or wood-masonry buildings with a maximum usable floor area limited, by the legal regulations at that time, to 70 square meters. This required investors to erect buildings that precisely matched this measurement, rather than larger buildings [

21]. The reasons for this limitation, which has had a strong impact on the aesthetics of the mountainous landscapes, were:

Socialist ideology: the communist state promoted collective ownership and frowned upon private property, especially for leisure, which was seen as a bourgeois concept. The state preferred to organize leisure through state-owned vacation resorts or trade union resorts.

Urbanization and the housing shortage: Under First Secretary Edward Gierek, the 1970s were a period of intensive industrialization and urbanization. Large housing estates (e.g., large blocks of flats) were built to accommodate workers, and the state prioritized providing primary housing rather than secondary, recreational homes.

“Wild” construction: Despite state ideology, there was huge social demand for weekend getaways. This led to the spontaneous, unregulated construction of small cabins, often on agricultural land or in forests, without formal permits or infrastructure. The government planned to gain control over this phenomenon.

A significant advantage of this type of construction was the integration of these objects into the mountain landscape. This was caused not only by the material used—wood and sometimes stone or bricks—but, at least in some cases, also by their design by architects. Even if many of the objects built during that period were prefabricated buildings, it should be noted that the quality of their architecture, including the functional layout adapted to the needs of potential users, was relatively high.

Although these small recreational buildings fit very well into the mountain landscape, a specific problem remained: the lack of a standardized architectural detail referring to the local traditional architecture. To a large extent, this resulted from relying on patterns from other countries, particularly Scandinavia. Due to entrenched cultural poverty caused by a long period of low wealth, architecture originating from that region of Europe did not develop architectural detail. It was, rather, characterized by great simplicity, very economical modesty of form, and significant functionality. The development and adaptation of Scandinavian folk art to the needs of modern design and, to a somewhat lesser extent, construction, began only in the 20th century. Its pioneers, still in Finland, were primarily artists and Finnish architects. It thus follows that despite creating functional architecture, largely successfully adapted to new conditions, Polish architects introduced foreign cultural patterns into the Beskid areas, which contributed to the partial loss of the cultural identity of the region.

With the increase in wealth in Polish society, which was especially noticeable in the late 1970s in Upper Silesia, recreational construction quickly gained in popularity. Instead of buildings with minimal volume, large buildings began to appear with greater frequence, with sizes corresponding to the requirements of year-round, single-family buildings. The interior layout of these buildings was also able to meet the needs of practically the entire family, with fully functionality. Buildings from this stage of regional development in the Beskids are often characterized by apparent durability and enormous functional diversity, and, considering architectural detail, formal diversity. This fundamentally changed the perception of mountain areas as a recreational base. From an exclusive getaway that provided complete contact with nature—not without a harsh tinge, a form of rest very popular primarily among the Polish intelligentsia—spending free time in the mountains became a relatively common custom. The effect was also the transfer of many ludic aspects of entertainment-connected recreation foreign to this region from the Silesian agglomeration to the Beskid villages. With the spread of recreational construction, the region inevitably lost its previous character.

The new type of recreational buildings, usually quite large, significantly changed the mountain landscape. These buildings began to resemble houses built after the war for permanent village residents, although they possessed certain distinguishing features. One of them, easily noticeable, was their steeply pitched roofs, conditioned by both actual needs and the resulting building law. Furthermore, at least initially, these new buildings were distinguished by visible evidence of the greater financial capabilities of their investors in the form of bold color schemes, very original architectural detail, and possibly plot development. The fundamental problems with this type of recreational construction became:

The very heavy structures compared to buildings erected using regional methods and previously popular light, wooden recreational houses;

An elaborate functional interior layout, generating high construction and maintenance costs, as well as a significant amount of work for users during time potentially intended for rest;

Considering only to a small degree of selected elements from the existing natural landscape;

A practical lack of reference to regional architecture in terms of volume, shape, color scheme, and architectural detail, combined with the application of elements of foreign origin (initially Scandinavian, and then most often Tyrolean or Bavarian); and

The use of very diverse, often culturally foreign patterns of plot development.

The Silesian Beskids are built of Godula and Istebna sandstone in the southern part of the Magura Flysch. The large weight of these new structures therefore adversely affected the preservation of objects in mountainous and foothill areas (

Figure 4). The Beskids are mountains, but from the point of view of constructing buildings, they have a relatively poor-quality substrate.

This mismatch between architecture and substrate increases the probability of landslides of varying scales. The local substrate requires an appropriate design approach that considers soil preservation during the frequent intense rainfall in the area. Failure to consider these conditions has often led to consequences commensurate with the size of the construction errors. Notably, cracks in the structure and other damage began to appear quickly in some buildings, which indicated serious construction flaws that could, in exceptional cases, even threaten the safety of their users. The construction approaches to foundations commonly used in flatland areas do not work in mountain conditions; the inability for water to flow just below the foundation level could also lead to flooding and even damage to parts of these new buildings.

Regional construction had solved this problem earlier by filling foundations with stone strip footings made of the same material—stones or brick rubble—and leaving openings on the slope and opposite sides to allow air or water flow. The foundations themselves were not deeply embedded, so the course of water was not disturbed, thus ensuring the proper functioning of natural water management. This method of foundation construction effectively prevented potential disasters and dampness at the base of the building base or the ground floor, which could be caused by the stoppage of water runoff.

Nevertheless, the knowledge developed over centuries of inhabiting mountainous areas was not use in new recreational construction. The use of deeply founded foundations in these buildings caused significant disturbances in water runoff, which contributed to frequent flooding of lower floors and subsequent damage. The risk of landslides, especially during heavy rainfall, begam to increase in these areas, which has led to construction disasters, including landslides carrying away entire buildings, which could only be demolished. These problems concern not only the buildings themselves but also plot development, as this involves unproven or ill-considered structural solutions such as extensive retaining walls that hinder proper water runoff. The construction of numerous retaining walls has primarily been caused by the building of heavy masonry structures in mountainous areas. The solution to the problems created by the use of retaining walls is the construction of lighter buildings—such as wooden structures that are adapted to the requirements of the terrain.

The elaborate functional interiors resulted from the direct transfer of typical lowland single-family construction to mountainous areas. Construction solutions proven for year-round, intensive occupation began to be used for entirely different tasks. Recreational buildings, which usually served the function of rest, should, in principle, have a functional layout adapted to that need. This involves limiting the expenditure of unnecessary work to maintain the building in a state of appropriate usability while also supporting an appropriate aesthetic level.

This principle has often been omitted in new recreational construction, which could lead to the perception of free time spent in recreational houses as a matter of constant work to maintain an aesthetic and functional state appropriate to the users’ needs. The weekly activation of heating, often requiring a long start-up period in spring or autumn, became practically a common custom, as did the frequently lengthy opening of the building secured against thieves. A similar problem became the systematic in plot development as well, with weekly grass mowing that often disturbed the rest of the neighbors. In this way, one of the main ideas of recreational construction was partially wasted—namely, that it consisted of rest combined with intensified contact with nature and the possibility of quieting the mind after a week of work in the city.

The aesthetics of the Beskid area include conditions resulting from terrain formation, the distribution of diverse types of vegetation, and objects erected by human hand, including technical infrastructure. Supported by the remoteness of urban planning [

22], lack of consideration of the existing natural landscape became, in the case of the described direction of recreational construction development, a principle that changed the appearance of the Polish Beskids for many years. The lack of harmony in village development is the primary manifestation of this state of affairs, with the very diverse terrain formation. The frequent placement of buildings in places violating the principles of spatial composition has ultimately led to a partial reduction of the landscape values in numerous villages and mountainous areas. It should be emphasized that the natural landscape is a national asset that constituted—and still constitutes—one of the main reasons for the development of recreational construction in mountainous areas. The reduction of the aesthetic values of improperly developed areas has contributed to a significant decrease in their value not only for further construction but also, to a lesser extent, for tourist traffic.

This problem concerns not only the location of recreational buildings, which remains inappropriate in relation to the natural terrain, but also the lack of reference to existing forests or groves. The consideration of already existing trees on the developed plot was a serious cultural challenge for people building recreational houses. Their presence was one of the reasons for recreational construction, but the reduction of sunlight on the plot or the possibility of damage to the building during a storm remained widespread fears among investors. Frequent, though often unconscious, destruction of existing vegetation largely contributed to the partial, though reversible, degradation of the Beskid landscape. The generally low level of knowledge about the care of diverse tree species—to preserve their health and aesthetic condition—also remains a problem. Knowledge regarding the use of tree and shrub species appropriate for the harsh mountain climate is also at a relatively low level.

The widespread, until recently, lack of reference to natural conditions and regional architecture was described—probably for the first time—long before the Second World War [

23]—in terms of volume, shape, color scheme, and architectural detail. This directly influenced the shaping of the Beskid landscape and contributed to its fundamental change. Starting from the 1980s, objects began to appear in the Beskids referencing foreign architecture—this time not Scandinavian, but Alpine, most often Tyrolean (

Figure 5) or Bavarian styles.

The direct inspiration for this trend in recreational construction was the increasingly frequent contacts of the Silesian population with that part of Europe. After 2000, however, a gradual return to wooden recreational construction can be noticed. New recreational objects are being built in the Polish Beskids that increasingly reference regional tradition in terms of building material, size, and shape (

Figure 6).

These buildings have diverse functional programs, most often very carefully tailored to the owners’ needs. They are executed in traditional log or frame construction, a Scandinavian or North American borrowing. Their advantage is, as in the case of regional construction, relatively low construction costs and low weight, which is adapted to mountain conditions. Log structures are often made of spruce, pine, larch, or fir wood, with logs usually having a cross-section between 18 and 32 cm. This means that additional internal thermal insulation must be applied. However, the most crucial role is played by the gradual change in the awareness of Poles, who generally associated wooden construction with a kind of technological “backwardness.” Currently, this situation is changing rapidly, and one of the reasons is the new discoveries regarding the beneficial influence of wooden objects on the health and well-being of their inhabitants.

4. Current State of Recreational Construction in the Beskid Mountains: Discussion

It follows that the tendency to cultivate native culture has not entirely disappeared. After a period of Polish fascination with foreign cultural patterns, references to regional architecture are increasingly encountered in the Polish mountains. These are related both to the form and typical Beskid color scheme and often also to architectural detail, particularly for windows and doors. Very frequently, however, they do not include decorative carpentry work. Most probably, this results from lack of familiarity among investors and the increasingly rapid disappearance of this art in the Beskids. The applied references to regional architecture are also often characterized by a low understanding of the often efficient and sound principles of Beskid construction. This may indicate the further disappearance of the region’s cultural identity. Often, references to Polish regional patterns can be observed in the Beskid area, but they do not originate from the area but from other regions of the country.

The use of diverse, and often culturally foreign, patterns of plot development became a common phenomenon at this stage of the development of recreational construction in the Beskids. Small, wooden recreational objects previously located in the Beskid areas were often landscaped with plant species typical of this area, for economic as well as aesthetic reasons. The next stages of development were characterized by much greater freedom and the use of a much wider selection of individual tree and shrub species. The development of recreational plots often referenced Alpine patterns, foreign to the local culture, including in the specific placement of certain plant species or garden gnomes, storks, other figures, and small fountains.

The popularization of knowledge about the architecture of the Beskid region has not proceeded in a linear fashion. Selected aspects concerning wood and river stone as basic building materials are widely known throughout the country. Still, a problem remains: the relatively limited knowledge about methods of preventing landslides and dampness in buildings and expertise in non-climatic and cultural conditions of Beskid construction, especially the scale and proportions of recreational buildings and their architectural detail. An ad hoc way to solve these problems in the Beskid area could be consultations, held at the beginning of construction processes, between designers and the local population, who have dealt with the climatic conditions specific to this area for generations.

It is also essential to gather this knowledge and make it available to architects designing recreational buildings in the Beskids. Comprehensive studies of Beskid regional architecture using the latest research methods and based on the inventory of existing buildings, indicating differences between its various varieties, would therefore be essential. Basic design guidelines for the development of modern recreational construction that consider the current needs of investors while preserving cultural identity, would need to be developed as well.

The use of regional architectural solutions in modern Beskid recreational construction does not mean that modern technologies should not be used, in terms of both modern technical and technological solutions. The tradition of Beskid regional architecture, as part of the Polish cultural heritage, should favor the development of regional art and construction using the latest achievements in all fields. Relaxation in recreational buildings should occur in increasingly better conditions in every respect, including aesthetically, as precise care for aesthetics has become exceptionally important due to the increasing population of the Beskids. Knowledge and the ability to apply the aesthetics proper to a given region in spatial development are indicators of the level of cultural development in a society. In the case of Beskid recreational construction, where investors usually come from other regions of the country—most often Silesia—it constitutes an indicator of respect for and understanding of the culture of the community inhabiting the mountainous and foothill areas.

It should also be emphasized that, from the point of view of spatial development, the use of solutions typical of regional construction or the construction of entire rural houses in cities and vice versa—the location of typically urban objects in the countryside—is aesthetically problematic and professionally improper. The effect of this process, which is noticeable in Upper Silesia and practically throughout the Beskid area, is the systematic destruction of the cultural landscape of Polish cities and villages. As a result of these actions, future generations will be forced either to leave the environment developed in this way or to pay the costs for changing this state of affairs. The earlier the planned prevention of such actions begins, the smaller the losses will be and the greater the possibilities for creating new, appropriately and highly aesthetically developed rural and urban spaces that preserve their cultural and aesthetic distinctiveness.