Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

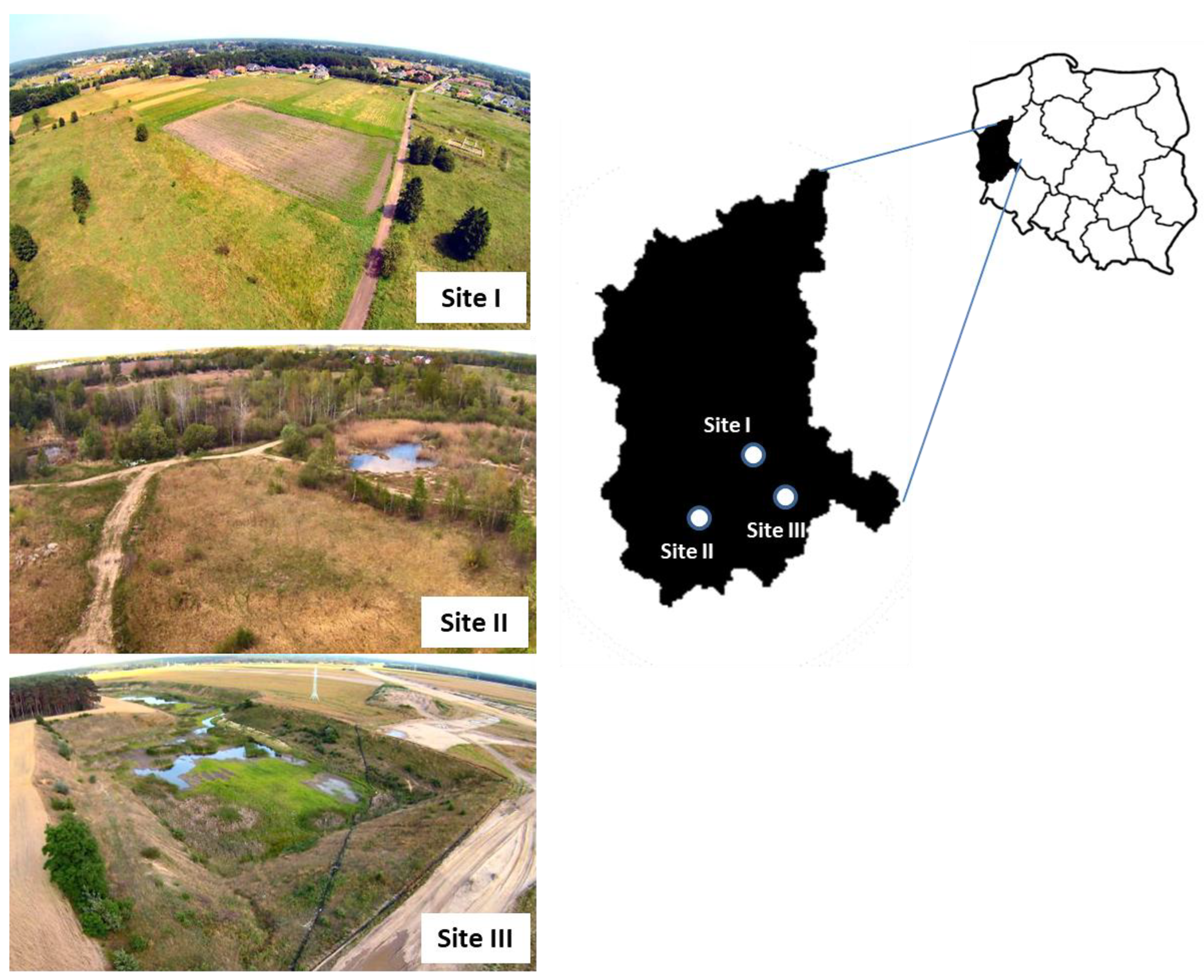

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Lizard Capture and Tick Collection

2.3. DNA Extraction

2.4. Screening for Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. DNA

2.5. Identification of Borrelia Species by Sequencing

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Lizards and Their Ticks

| Site | Host (No./MI)a | Tick stage | No. collected |

No. isolates tested/positive | MIR (%) b | BLc | BB | BA |

| I (ZG) | LA (55/5.5) | Larvae | 171 | 47/11 | 6,4 | 5 | 6 | 0 |

| Nymphs | 109 | 45/6 | 5,5 | 2 | 3 | 1 [1] d | ||

| Subtotal | 280 | 92/17 | 6,1 | 7 | 9 | 1 | ||

| II (Z) | LA (65/10.8) | Larvae | 581 | 123/10 | 1,7 | 8 | 2 | |

| Nymphs | 124 | 61/30 | 24,2 | 29 | 1 | |||

| Subtotal | 705 | 184/40 | 5,7 | 37 | 3 | |||

| III (NS) | LA (51/2.8) | Larvae | 85 | 41/6 | 7,1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Nymphs | 59 | 41/8 | 13,6 | 6 | 2 | [1] d | ||

| Subtotal | 144 | 82/14 | 9,7 | 8 | 5 | 1 | ||

| TOTAL | LA (167/6.8) | Larvae | 837 | 211/27 | 3,2 | 15 (55.6) | 11 (40.7) | 1 (3.7) |

| Nymphs | 292 | 147/44 | 15,1 | 37 (84.1) | 6 (13.6) | 1 (2.3) | ||

| TOTAL | 1129 | 358/71 | 6,3 | 52 (73.2) | 17 (23.9) | 2 (2.8) | ||

| I (ZG) | ZV (42/3.9) | Larvae | 116 | 33/7 | 6,0 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Nymphs | 48 | 21/3 | 6,3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||

| TOTAL | 164 | 54/10 | 6,1 | 1 (10.0) | 9 (90.0) | 0 |

| Site | Host | No. tested | No. positive (%) | BL* | BB | BA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (ZG) | LA | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| II (Z) | LA | 50 | 8 (16.0) | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| III (NS) | LA | 46 | 7 (15.2) | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| TOTAL | LA | 131 | 15 (11.5) | 5 (33.3) | 9 (60.0) | 1 (6.7) |

| I (ZG) | ZV | 41 | 2 (4.9) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

3.2. Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. DNA in Ticks and Lizards

3.3. Prevalence of B. burgdorferi Sensu Lato Species

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andres, C.; Franke, F.; Bleidorn, C.; Bernhard, D.;, Schlegel, M. Phylogenetic analysis of the Lacerta agilis subspecies complex. Systematics and Biodiversity. 2014, 12, 43-54. [CrossRef]

- Gill, I.; McGeorge, I.; Jameson, T.J.M.; Moulton, N.; Wilkie, M.; Försäter, K.; Gardner, R.; Bockreiß, L.; Simpson, S.; Garcia,; G.. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines for Sand Lizard (Lacerta agilis). First edition. European Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023.

- Berman, D.I.; Bulakhova, N.A.; Alfimov, A.V.; Meshcheryakova, E.N. How the most northern lizard, Zootoca vivipara, overwinters in Siberia. Polar. Biol. 2016, 39, 2411–2425. [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, D.; Strijbosch, H.; Stumpel,; A.H.P. The Lizards Lacerta agilis and L. vivipara as Hosts to Larvae and Nymphs of the Tick Ixodes ricinus. Holarctic Ecology. 1983, 6, 32-40. [CrossRef]

- Ekner, A.; Majlath, I.; Majlathova, V.; Hromada, M.; Bona, M.; Antczak, M.; Bogaczyk, M.; Tryjanowski, P. Densities and Morphology of Two Co-existing Lizard Species (Lacerta agilis and Zootoca vivipara) in Extensively Used Farmland in Poland. Folia Biol. 2008, 56, 165-17. [CrossRef]

- Gwiazdowicz, D.J.; Gdula, A.K.; Kurczewski, R.; Zawieja, B. Factors influencing the level of infestation of Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) on Lacerta Agilis and Zootoca vivipara (Squamata: Lacertidae). Acarologia. 2020, 60, 390–397. [CrossRef]

- Wodecka, B.; Kolomiiets, V. Genetic Diversity of Borreliaceae Species Detected in Natural Populations of Ixodes ricinus Ticks in Northern Poland. Life. 2023, 13, 972. [CrossRef]

- Strnad, M.; Hönig, V.; Růžek, D.; Grubhoffer, L.; Rego, R.O.M. Europe-wide meta-analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00609-17. [CrossRef]

- Stanek, G.; Strle, F. Lyme borreliosis – from tick bite to diagnosis and treatment. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2018, 42. 233–258. [CrossRef]

- Steinbrink, A.; Brugger, K.; Margos, G.; Kraiczy, P.; Klimpel, S. The evolving story of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato transmission in Europe. Parasitol Res. 2022, 121, 781-803. [CrossRef]

- Majláthová, V.; Majláth, I.; Derdáková, M.; Víchová, B.; Pet'ko, B. Borrelia lusitaniae and green lizards (Lacerta viridis), Karst Region, Slovakia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006, 12, 1895–1901. [CrossRef]

- Richter, D.; Matuschka, F.R. Perpetuation of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia lusitaniae by lizards. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 4627–4632. [CrossRef]

- Földvári, G.; Rigó, K.; Majláthová, V.; Majláth, I.; Farkas, R.; Pet’ko, B. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Lizards and Their Ticks from Hungary. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009, 9, 331-336.

- Ekner ,A.; Dudek, K.; Sajkowska, Z.; Majláthová, V.; Majláth, I.; Tryjanowski, P. Anaplasmataceae and Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato in the sand lizard Lacerta Agilis and co-infection of these bacteria in hosted Ixodes ricinus ticks. Parasit Vectors. 2011, 4:182. [CrossRef]

- Musilová, L; Kybicová, K.; Fialová, A.; Richtrová, E.; Kulma, M. First isolation of Borrelia lusitaniae DNA from green lizards (Lacerta viridis) and Ixodes ricinus ticks in the Czech Republic. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2022, 13, 101887. [CrossRef]

- Cirkovic, V.; Veinovic, G.; Stankovic, D.; Mihaljica, D.; Sukara, R.; Tomanovic, S. Evolutionary dynamics and geographical dispersal of Borrelia lusitaniae. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1330914. [CrossRef]

- Poupon, M.; Lommano, E.; Humair, P.; Douet, V.; Rais, O.; Schaad, M.; Jenni, L.; Gern, L. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato in Ticks Collected from Migratory Birds in Switzerland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72, 976–979. [CrossRef]

- Norte, A.C.; Margos, G.; Becker, N.S.; Albino Ramos, J.; Nuncio, M.S.; Fingerle, V.; Araujo, P.M.; Adamik, P.; Alivizatos, H.; Barba, E.; et al. Host dispersal shapes the population structure of a tick-borne bacterial pathogen. Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 485–501. [CrossRef]

- Norte, A.C.; Alves da Silva, A.; Alves, J.; da Silva, L.P.; Nuncio, M.S.; Escudero, R.; Anda, P.; Ramos, J.A.; Lopes de Carvalho, I. The importance of lizards and small mammals as reservoirs for Borrelia lusitaniae in Portugal. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2015, 7, 188–193. [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, I.L.; Zeidner, N.; Ullmann, A.; Hojgaard, A.; Amaro, F.; Ze-Ze, L.; Alves, M.J.; de Sousa, R.; Piesman, J.; Nuncio, M.S. Molecular characterization of a new isolate of Borrelia lusitaniae derived from Apodemus sylvaticus in Portugal. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010, 10, 531–534. [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, L.; Perazzo, S.; Venturino, E.; Giacobini, M.; Bertolotti, L.; Mannelli, A. Modeling the effects of variable feeding patterns of larval ticks on the transmission of Borrelia lusitaniae and Borrelia afzelii. Theor Popul Biol. 2017, 116, 27-32. [CrossRef]

- Rizzoli, A.; Silaghi, C.; Obiegala, A.; Rudolf, I; Hubálek, Z.; Földvári, G.; Plantard, O.; Vayssier-Taussat, M.; Bonnet, S; Spitalská, E,; Kazimírová, M. Ixodes ricinus and its transmitted pathogens in urban and periurban areas in Europe: new hazards and relevance for public health. Front Public Health. 2014, 2, 251. [CrossRef]

- Siuda, K., 1993. Ticks (Acari: Ixodida) of Poland. Part II: Taxonomy and Distribution. Polskie Towarzystwo Parazytologiczne, Warszawa (in Polish).

- Rijpkema, S.; Bruinink, H. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by PCR in 1070 questing Ixodes ricinus larvae from the Dutch North Sea island of Ameland. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1996, 20, 381–385. [CrossRef]

- Courtney, J.W.;, Kostelnik, L.M.;, Zeidner, N.S.;, Massung, R.F. Multiplex real-time PCR for detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42, 3164-3168. [CrossRef]

- Wodecka, B.; Leońska, A.; Skotarczak, B. A comparative analysis of molecular markers for the detection and identification of Borrelia spirochaetes in Ixodes ricinus. J Med Microbiol. 2010, 59, 309–314. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018, 35, 1547-1549. [CrossRef]

- Fracasso, G.; Grillini, M.; Grassi, L.; Gradoni, F.; Rold, G.d.; Bertola, M. Effective Methods of Estimation of Pathogen Prevalence in Pooled Ticks. Pathogens. 2023, 12, 557. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, M.; Najbar, B. Ectoparasitism of castor bean ticks Ixodes ricinus (Linnaeus, 1758) on sand lizards Lacerta agilis (Linnaeus, 1758) in western Poland. Studia Biologica. 2022, 16, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Dudek, K.; Skórka, P.; Sajkowska, Z.A.; Ekner-Grzyb, A.; Dudek, M.; Tryjanowski, P. (2016) Distribution pattern and number of ticks on lizards. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016, 7, 172–179. [CrossRef]

- Dyczko, D.; Krysmann, A.; Kolanek, A.; Borczyk, B.; Kiewra, D. Bacterial pathogens in Ixodes ricinus collected from lizards Lacerta agilis and Zootoca vivipara in urban areas of Wrocław, SW Poland– preliminary study. Exp Appl Acarol. 2024, 93, 409–420. [CrossRef]

- Köhler, C.F.; Sprong, H.; Fonville, M.; Esser, H., De Boer, W.F.; Van der Spek, V.; Spitzen-van der Sluijs, A. Sand lizards (Lacerta agilis) decrease nymphal infection prevalence for tick-borne pathogens Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in a coastal dune ecosystem. J Appl Ecol. 2023, 60, 1115–26.

- Gryczyńska-Siemiątkowska, A.; Siedlecka, A.; Stańczak, J.; Barkowska, M. Infestation of sand lizards [Lacerta Agilis] resident in the Northeastern Poland by Ixodes ricinus [L.] ticks and their infection with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Acta Parasitol. 2007, 52, 165–170. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, M.; Rektor, R.; Najbar, B.; Morelli, F. Tick parasitism is associated with home range area in the sand lizard, Lacerta agilis. Amphibia-Reptilia. 2020, 41, 479–488. [CrossRef]

- Majláthová, V.; Majláth, I.; Hromada, M.; Tryjanowski, P.; Bona, M.; Antczak, M.; Víchová, B.; Dzimko, Š.; Mihalca, A.; Peťko, B. The role of the sand lizard (Lacerta sgilis) in the transmission cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Internat J Med Microbiol. 2008, 298 S1, 161–167. [CrossRef]

- Ciebiera, O.; Grochowalska, R.; Łopińska, A.; Zduniak, P.; Strzała, T.; Jerzak, L. Ticks and spirochetes of the genus Borrelia in urban areas of Central-Western Poland. Exp Appl Acarol. 2024, 93, 421–437. [CrossRef]

- Collares-Pereira, M.; Couceiro, S.; Franca, I.; Kurtenbach, K.; Schafer, S.M.; Vitorino, L.; Goncalves, L.; Baptista, S.; Vieira, M.L.; Cunha, C. First isolation of Borrelia lusitaniae from a human patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 1316–1318. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, I.L.; Fonseca, J.E.; Marques, J.G.; Ullmann, A.; Hojgaard, A.; Zeidner, N.; Núncio, M.S. 2008. Vasculitis-like syndrome associated with Borrelia lusitaniae infection. Clin. Rheumatol. 2008. 27, 1587–1591. [CrossRef]

- Veinović, G.; Malinić, J.; Sukara, R.; Mihaljica, D.; Katanić, N.; Poluga, J.; Tomanović, S. Isolation and cultivation of Borrelia lusitaniae from the blood of a patient with multiple erythema migrans. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2025, 19, 630-635. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.P.; Brito, M.J.; de Carvalho, I.L. Borrelia lusitaniae Infection Mimicking Headache, Neurologic Deficits, and Cerebrospinal Fluid Lymphocytosis. Journal of Child Neurology. 2019, 34, 748-750. [CrossRef]

- Brisson, D.; Dykhuizen, D.E. OspC diversity in Borrelia burgdorferi: different hosts are different niches. Genetics. 2004, 168, 713–722.

- Vuong, H.B.; Canham, C.D.; Fonseca, D.M.; Brisson, D.; Morin, P.J.; Smouse, P.E.; Ostfeld, R.S. Occurrence and transmission efficiencies of Borrelia burgdorferi ospC types in avian and mammalian wildlife. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 27, 594–600. [CrossRef]

- Michalik, J.; Wodecka, B.; Liberska, J.; Dabert, M.; Postawa, T.; Piksa, K.; Stańczak, J. Diversity of Lyme borreliosis spirochete species in Ixodes spp. ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) associated with cave-dwelling bats from Poland and Romania. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101300. [CrossRef]

- Radolf, J.D.; Strle, K.; Lemieux, J.E.; Strle, F. Lyme disease in humans. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 42, 333–384. [CrossRef]

- Strzelczyk, J.K.; Gaździcka, J.; Cuber, P.; Asman, M.; Trapp, G.; Gołąbek, K.; Zalewska-Ziob, M.; Nowak-Chmura, M.; Siuda, K.; Wiczkowski, A.; Solarz, K. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus ticks collected from southern Poland. Acta Parasitol. 2015, 60, 666–674. [CrossRef]

- Wójcik-Fatla, A.; Zając, V.; Sawczyn, A.; Sroka, J.; Cisak, E.; Dutkiewicz, J. Infections and mixed infections with the selected species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex in Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in eastern Poland: a significant increase in the course of 5 years. Exp Appl Acarol. 2016, 68, 197–212. [CrossRef]

- Sawczyn-Domańska, A.; Zwoliński, J.; Kloc, A.; Wójcik-Fatla, A. Prevalence of Borrelia, Neoehrlichia mikurensis and Babesia in ticks collected from vegetation in eastern Poland. Exp Appl Acarol. 2023, 90, 409-428. [CrossRef]

- Strnad, M.; Hönig, V.; Ružek, D.; Grubhoffer, L.; Rego, R.O.M. Europe-wide meta-analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00609-17. [CrossRef]

- Paradowska-Stankiewicz, I.; Zbrzeźniak, J.; Skufca, J.; Nagarajan, A.; Ochocka, P.; Pilz, A.; Vyse, A.; Begier, E.; Dzingina, M.; Blum, M.; Riera-Montes, M.; Gessner, B.D.; Stark, J.H. A Retrospective Database Study of Lyme Borreliosis Incidence in Poland from 2015 to 2019: A Public Health Concern. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2023, 23, 247-255. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).