Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Mean absolute error (MAE)

- Root means square error (RMSE)

- Coefficient of Determination (R2)

| Column Name |

Data Type |

Data Category |

Sample Value |

Null Count | Completeness (%) |

Unique Value |

Value Range |

Mean |

| Study_id Type of plastic Dose of plastic (%) Mixing Temp. Mixing Rate Mixing Time Type of Bitumen Age/unage Softening point Penetration Viscosity |

object object float64 float64 float64 float64 object object float64 float64 float64 |

Text Text Numeric Numeric Numeric Numeric Text Text Numeric Numeric Numeric |

St_01, St_01, St_01 R-LLDPE, R-LLDPE, R-LLDPE 3.0, 3.0, 3.0 170.0, 170.0, 170.0 3500.0, 3500.0, 3500.0 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 C320, C320, C320 Unaged, Unaged, Unaged 49.5, 83.7, 119.3 547.0, 403.0, 253.0 0.81, 1.46, 3.52 |

0 0 0 15 85 42 11 231 57 44 144 |

100 100 100 94 66 83 95 7.6 77.2 82.4 42.4 |

51 28 25 17 16 17 39 2 102 120 94 |

NA NA 0-36 120-250 20-13000 2-180 NA NA 3.83-131 15-820 0.16-10 |

NA NA 5.43 170 2110 49 NA NA 61 320 2.2 |

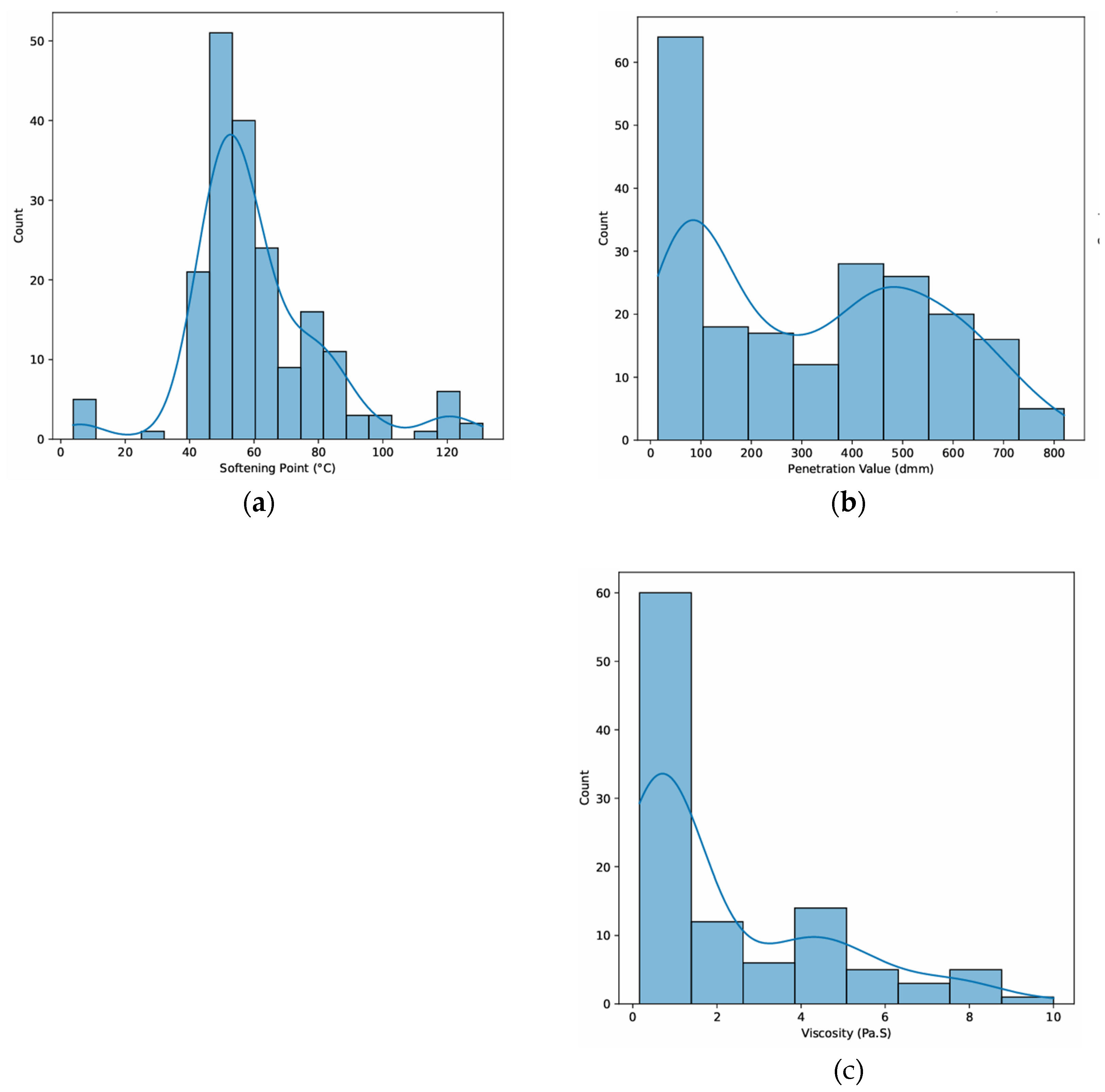

3. Results and Discussion

4. Discussion

- Incorporating plastic waste results in a higher softening point, decreased penetration, and increased viscosity, confirming the stiffening effect that improves rut resistance.

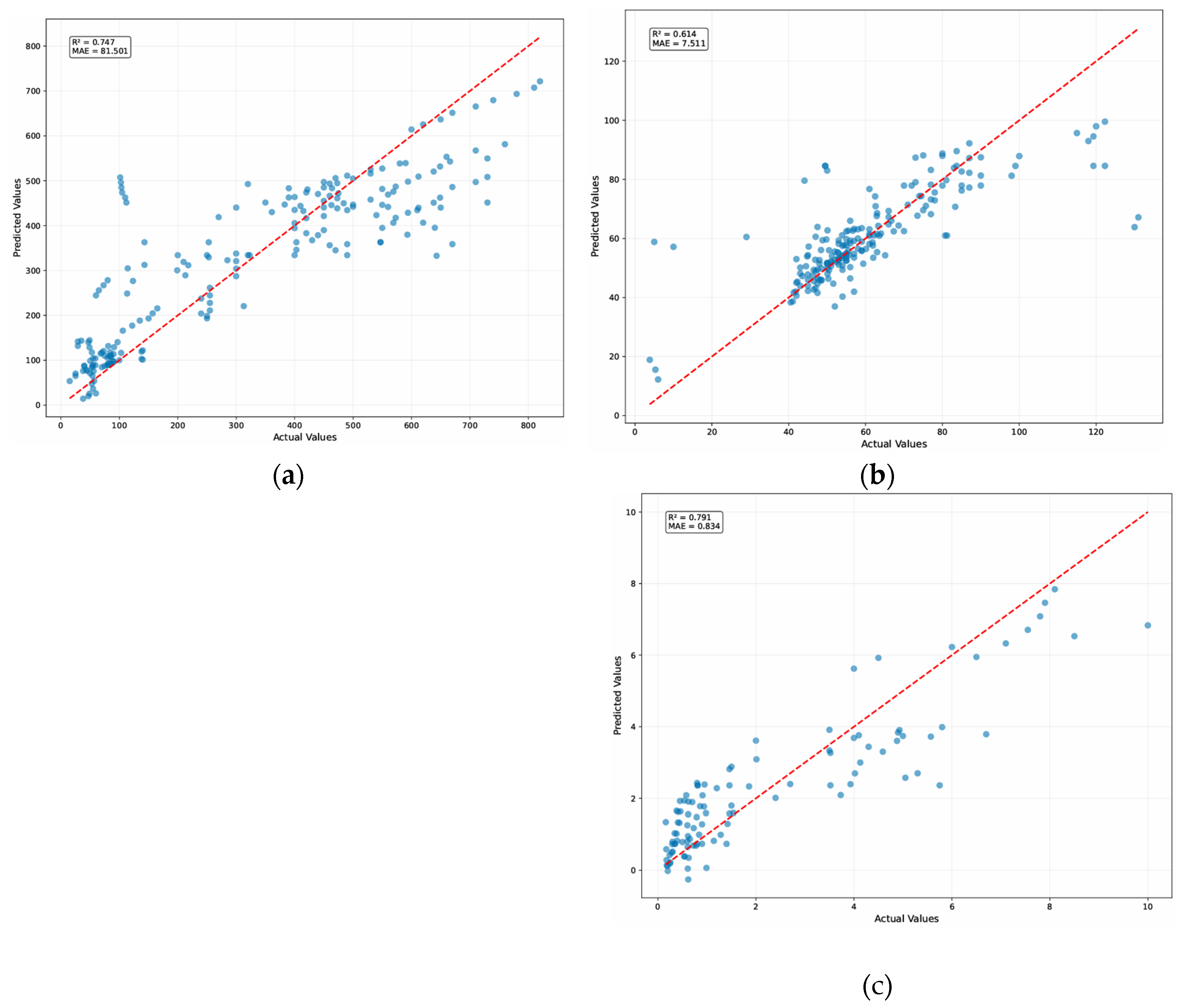

- The Softening Point model has high prediction accuracy (R2 = 0.79) but underestimated at extreme values.

- The Penetration model (R2 = 0.61) had small scale accuracy due to its susceptibility to parameters such as plastic type, particle size, and mixing consistency.

- The Viscosity model (R2 = 0.79) made accurate predictions, notably in the low to mid ranges, demonstrating a greater correlation with observable process parameters.

- Tree-based ML algorithms (Random Forest, XGBoost) outperformed linear models, demonstrating the usefulness of nonlinear techniques in predicting binder characteristics.

- Previous research has shown that PE, PET, and other plastic wastes improve high-temperature stability while decreasing ductility.

5. Conclusions

- Four models were evaluated: median baseline, linear regression, random forest, and xgboost. Tree-based models (Random Forest and XGBoost) outperformed other models in predicting softening point and viscosity, with R2 values of 0.79 and 0.61, respectively, demonstrating their ability to capture nonlinear interactions.

- Softening Point predictions were highly accurate (R2 = 0.79, MAE = 0.83), with consistent alignment between anticipated and actual values, but underestimate occurred at greater ranges.

- The penetration predictions demonstrated modest accuracy (R2 = 0.61, MAE = 7.51), showing more sensitivity to uncontrolled parameters such as plastic type, particle size, and mixing homogeneity.

- Viscosity predictions were extremely trustworthy (R2 = 0.79, MAE = 0.83), notably in the low to mid ranges, showing viscosity as a feature closely related to quantifiable processing factors.

- The results are consistent with existing research that show that plastic modification regularly increases softening point and viscosity while decreasing penetration, stiffening the binder and enhancing rutting resistance at high service temperatures.

- The findings demonstrate that nonlinear machine learning techniques outperform baseline or linear models in predicting binder performance, encouraging its usage in sustainable pavement design research.

References

- R. Geyer, J. R. Jambeck, and K. L. Law, “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made,” Science Advances, vol. 3, no. 7, p. e1700782, 2017, doi: doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782.

- G. White, “RECYCLED WASTE PLASTIC FOR EXTENDING AND MODIFYING ASPHALT BINDERS “ 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Greg-White/publication/324908837_RECYCLED_WASTE_PLASTIC_FOR_EXTENDING_AND_MODIFYING_ASPHALT_BINDERS/links/5aea9deda6fdcc03cd90c94c/RECYCLED-WASTE-PLASTIC-FOR-EXTENDING-AND-MODIFYING-ASPHALT-BINDERS.pdf.

- A. O. Sojobi, S. E. Nwobodo, and O. J. Aladegboye, “Recycling of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic bottle wastes in bituminous asphaltic concrete,” Cogent Engineering, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 1133480, 2016/12/31 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Huda and H. Anzar, “Plastic Roads: A Recent Advancement in Waste Management,” vol. 5, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.ijert.org/research/plastic-roads-a-recent-advancement-in-waste-management-IJERTV5IS090574.pdf.

- k. Edukondalu et al., “Use of Waste Plastic Materials in Flexible Pavements,” International Journal of Innovative Research in Computer Science and Technology, vol. 10, no. 5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A.Gulzat, Y. Madeniyet, Y. Dana, I. Aiganym, and M. Sofya, “The use of polyethylene terephthalate waste as modifiers for bitumen systems,” Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies, vol. 3, no. 6(117), pp. 6-13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Nizamuddin, M. Jamal, R. Gravina, and F. Giustozzi, “Recycled plastic as bitumen modifier: The role of recycled linear low-density polyethylene in the modification of physical, chemical and rheological properties of bitumen,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 266, p. 121988, 2020/09/01/ 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Ayush, “Utilization of Recycled Plastic Waste in Road Construction,” vol. 10, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.ijert.org/research/utilization-of-recycled-plastic-waste-in-road-construction-IJERTV10IS050289.pdf.

- Y. Imanbayev et al., “Modification of Bitumen with Recycled PET Plastics from Waste Materials,” Polymers, vol. 14, no. 21. [CrossRef]

- B. Saleh and R. Ms, “Study on Effect of Plastic Waste on Softer Grade (Vg-10) Bitumen,” pp. 2350-0557, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Tri, A. Chusnul, E. Shaopeng, and S. Fardzanela, “Rutting Resistance of Agricultural-Waste-Plastic Based Modified Bitumen,” Civil Engineering and Architecture, vol. 13, no. 3, 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Mashaan, A. Chegenizadeh, and H. Nikraz, “Laboratory Properties of Waste PET Plastic-Modified Asphalt Mixes,” Recycling, vol. 6, p. 49, 07/14 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, Y. Fang, L. Liu, and Q. Zhu, “Multi-Damage Healing Ability of Modified Bitumen with Waste Plastics Based on Rheological Property,” Materials, vol. 18, no. 16. [CrossRef]

- I. Elnaml et al., “Recycling waste plastics in asphalt mixture: Engineering performance and environmental assessment,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 453, p. 142180, 2024/05/10/ 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Köfteci, P. Ahmedzade, and B. Kultayev, “Performance evaluation of bitumen modified by various types of waste plastics,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 73, pp. 592-602, 2014/12/30/ 2014. [CrossRef]

- k. Edukondal et al., “Use of Waste Plastic Materials in Flexible Pavements,” International Journal of Innovative Research in Computer Science & Technology, vol. 10, no. 5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Isaac, “Recycling Waste Plastics in Asphalt Pavements,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/circulars/ec291.pdf.

- X. Dai, Lu, E. Marie, M. Hassan, and G. Filippo, “ Performance Evaluation of Post-Consumer and Post-Industrial Recycled Plastics as Binder Modifier in Asphalt Mixes,” International Journal of Pavement Research and Technology, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Mashaan, A. Chegenizadeh, and H. Nikraz, “A Comparison on Physical and Rheological Properties of Three Different Waste Plastic-Modified Bitumen,” Recycling, vol. 7, no. 2. [CrossRef]

- M. Abdelaziz and K. Mohamed, “RHEOLOGICAL EVALUATION OF BITUMINOUS BINDER MODIFIED WITH WASTE PLASTIC MATERIAL,” 2010. [Online]. Available: https://eprints.um.edu.my/3186/1/MAHREZ_Abdelaziz.pdf.

- T. Hu, Y. Luo, Y. Zhu, Y. Chu, G. Hu, and X. Xu, “Mechanochemical preparation and performance evaluations of bitumen-used waste polypropylene modifiers,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 21, p. e03471, 2024/12/01/ 2024. [CrossRef]

- U. Ghani, B. Zamin, M. Tariq Bashir, M. Ahmad, M. M. Sabri, and S. Keawsawasvong, “Comprehensive Study on the Performance of Waste HDPE and LDPE Modified Asphalt Binders for Construction of Asphalt Pavements Application,” Polymers, vol. 14, no. 17. [CrossRef]

- N. Van Hung, L. Van Phuc, and N. Thanh Phong, “Performance Evaluation of Waste High Density Polyethylene as a Binder Modifier for Hot Mix Asphalt,” International Journal of Pavement Research and Technology, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Moses, K. Reneta, N. Nsahlai, N. Jules, B. Kingsly, and C. Adriel, “Physico-Mechanical Characterization Of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET)-Modified Ashalt For Enchanced Flexible Pavements,” IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering (IOSR-JMCE, vol. 22, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Kakar, P. Mikhailenko, Z. Piao, M. Bueno, and L. Poulikakos, “Analysis of waste polyethylene (PE) and its by-products in asphalt binder,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 280, p. 122492, 2021/04/19/ 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Li et al., “Analysis of the Influence of Production Method, Plastic Content on the Basic Performance of Waste Plastic Modified Asphalt,” Polymers, vol. 14, no. 20. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Ahmad and S. A. Ahmad, “The impact of polyethylene terephthalate waste on different bituminous designs,” Journal of Engineering and Applied Science, vol. 69, no. 1, p. 53, 2022/06/22 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Joni, R. H. A. Al-Rubaee, and M. A. Al-zerkani, “Characteristics of asphalt binder modified with waste vegetable oil and waste plastics,” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 737, no. 1, p. 012126, 2020/02/01 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. White and F. Hall, “Comparing asphalt modified with recycled plastic polymers to conventional polymer modified asphalt,” 2021, pp. 3-17.

- I. Elnaml, J. Liu, L. N. Mohammad, N. Wasiuddin, S. B. Cooper, and S. B. Cooper, “Developing Sustainable Asphalt Mixtures Using High-Density Polyethylene Plastic Waste Material,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 13. [CrossRef]

- M. Gürü, M. K. Çubuk, D. Arslan, S. A. Farzanian, and İ. Bilici, “An approach to the usage of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) waste as roadway pavement material,” Journal of Hazardous Materials, vol. 279, pp. 302-310, 2014/08/30/ 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Nizamuddin, Y. J. Boom, and F. Giustozzi, “Sustainable Polymers from Recycled Waste Plastics and Their Virgin Counterparts as Bitumen Modifiers: A Comprehensive Review,” Polymers, vol. 13, no. 19. [CrossRef]

- A. Jexembayeva, M. Konkanov, L. Aruova, A. Kirgizbayev, and L. Zhaksylykova, “Modifying Bitumen with Recycled PET Plastics to Enhance Its Water Resistance and Strength Characteristics,” Polymers, vol. 16, no. 23. [CrossRef]

- S. Haider, I. Hafeez, Jamal, and R. Ullah, “Sustainable use of waste plastic modifiers to strengthen the adhesion properties of asphalt mixtures,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 235, p. 117496, 2020/02/28/ 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Umar, R. Abdur, K. Ammad Hassan, and R. Zia Ur, “USE OF PLASTIC WASTES AND RECLAIMED ASPHALT FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT,” THE BALTIC JOURNAL OF ROAD AND BRIDGE ENGINEERING, vol. 15, no. 2, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://bjrbe-journals.rtu.lv/bjrbe/article/download/bjrbe.2020-15.479/503.

- R.Manju, S. Sathya, and K. Sheema, “Use of Plastic Waste in Bituminous Pavement “ International Journal of ChemTech Research vol. 10, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rmanju-Anand/publication/320243162_Use_of_Plastic_Waste_in_Bituminous_Pavement/links/59d70660458515db19c5d8a3/Use-of-Plastic-Waste-in-Bituminous-Pavement.pdf.

- J. K. Appiah, V. N. Berko-Boateng, and T. A. Tagbor, “Use of waste plastic materials for road construction in Ghana,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 6, pp. 1-7, 2017/06/01/ 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Ambika, S. Girish, and K. Gajendra, “A sustainable approach: Utilization of waste PVC in asphalting of roads “ Construction and Building Materials, vol. 54, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Imran M, K. Shahid, A. Majed A, and A. Feras F, “Asphalt Design Using Recycled Plastic and Crumb-rubber Waste for Sustainable Pavement Construction,” Procedia Engineering, vol. 145, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A.-M. Jaffar and M. Sahar, “Preparation of sustainable asphalt pavements using polyethylene terephthalate waste as a modifier,” Zastita materijala, vol. 58, no. 3, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Malik Shoeb and M. Fareed, “Characterization of Bitumen Mixed With Plastic Waste,” International Journal of Transportation Engineering, vol. 3, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.sid.ir/en/VEWSSID/J_pdf/5060520150201.pdf.

- S. Needhidasan, R. B., and G. A. S., “Experimental investigation of bituminous pavement (VG30) using E-waste plastics for better strength and sustainable environment,” Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 22, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Abhaykumar and W. Mudassir, “Use of Waste Plastic and Waste Rubber in Aggregate and Bitumen for Road Materials,” International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering Website: www.ijetae.com, vol. 9001, no. 7, 2008. [Online]. Available: https://xilirprojects.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/1.-Use-of-Waste-Plastic-and-Waste-Rubber-in-Aggregate-and.pdf.

- X. Xu et al., “Sustainable Practice in Pavement Engineering through Value-Added Collective Recycling of Waste Plastic and Waste Tyre Rubber,” Engineering, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 857-867, 2021/06/01/ 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Agha, A. Hussain, A. S. Ali, and Y. Qiu, “Performance Evaluation of Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA) Containing Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Using Wet and Dry Mixing Techniques,” Polymers, vol. 15, no. 5. [CrossRef]

- J. Waples, “Mean Absolute Error Explained: Measuring Model Accuracy,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.datacamp.com/tutorial/mean-absolute-error.

- P. Schneider, “Mean Absolute Error - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/mean-absolute-error.

- ScienceDirect, “Root Mean Square Error - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/root-mean-square-error.

- G. Romeo, “Determination Coefficient - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/mathematics/determination-coefficient.

- S. Huda and H. Anzar, “Plastic Roads: A Recent Advancement in Waste Management,” International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT), vol. 5, no. 09, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.ijert.org/research/plastic-roads-a-recent-advancement-in-waste-management-IJERTV5IS090574.pdf.

- A. A. Amani, A.-M. Abeer, B. Gabriel, A. Sameh, S. B. A. Ahmed, and A. Ali, “Utilizing waste polyethylene for improved properties of asphalt binders and mixtures: A review,” Advances in Science and Technology Research Journal, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Zeiada, G. Al-Khateeb, E. Y. Hajj, and H. Ezzat, “Rheological properties of plastic-modified asphalt binders using diverse plastic wastes for enhanced pavement performance in the UAE,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 452, p. 138922, 2024/11/22/ 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Chen, J. Ma, X. Xu, T. Pu, Y. He, and Q. Zhang, “Performance Evaluation of Using Waste Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Derived Additives for Asphalt Binder Modification,” Waste and Biomass Valorization, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 601-611, 2025/02/01 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Sadat Hosseini, P. Hajikarimi, M. Gandomi, F. Moghadas Nejad, and A. H. Gandomi, “Optimized machine learning approaches for the prediction of viscoelastic behavior of modified asphalt binders,” Construction and Building Materials, vol. 299, p. 124264, 2021/09/13/ 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Gopakumar and K. P. Biligiri, “Morphological and Rheological Assessment of Waste Plastic-Modified Asphalt-Rubber Binder,” in Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Maintenance and Rehabilitation of Pavements, Cham, P. Pereira and J. Pais, Eds., 2024// 2024: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 405-415.

| Sl.no. | Data | Reference | ||

| Softening | Penetration | Viscosity | ||

| St_01 St_01 St_01 St_01 St_02 St_02 St_02 St_02 St_02 St_03 St_03 St_03 St_04 St_04 St_04 St_04 St_04 St_04 St_05 St_05 St_05 St_05 St_06 St_06 St_06 St_07 St_07 St_07 St_07 St_07 St_07 St_08 St_08 St_08 St_08 St_09 St_09 St_09 St_09 St_09 St_10 St_10 St_10 St_10 St_11 St_11 St_11 St_12 St_12 St_12 St_12 St_12 St_13 St_13 St_13 St_14 St_14 St_14 St_14 St_14 St_14 St_14 St_14 St_15 St_15 St_15 St_16 St_16 St_16 St_16 St_16 St_17 St_17 St_17 St_18 St_18 St_18 St_18 St_18 St_19 St_19 St_19 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_20 St_21 St_21 St_21 St_21 St_22 St_22 St_22 St_22 St_22 St_22 St_23 St_23 St_23 St_24 St_24 St_24 St_24 St_24 St_24 St_24 St_25 St_25 St_25 St_25 St_25 St_26 St_26 St_26 St_26 St_27 St_27 St_27 St_27 St_27 St_28 St_28 St_28 St_28 St_29 St_29 St_30 St_30 St_30 St_30 St_30 St_30 St_30 St_31 St_31 St_31 St_31 St_31 St_31 St_31 St_32 St_32 St_32 St_33 St_33 St_33 St_33 St_33 St_33 St_33 St_33 St_34 St_34 St_34 St_35 St_35 St_35 St_36 St_36 St_36 St_36 St_36 St_37 St_37 St_37 St_37 St_37 St_37 St_38 St_38 St_38 St_38 St_38 St_38 St_39 St_39 St_39 St_39 St_39 St_39 St_39 St_39 St_40 St_40 St_40 St_41 St_41 St_42 St_42 St_42 St_42 St_42 St_42 St_43 St_43 St_44 St_44 St_44 St_44 St_45 St_45 St_45 St_46 St_46 St_46 St_46 St_46 St_46 St_46 St_47 St_47 St_47 St_47 St_47 St_48 St_48 St_48 St_48 St_49 St_49 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_50 St_51 St_51 St_51 St_51 St_51 |

49.5 83.7 119.3 122.3 70 72 80 85 90 43 51 62 47.5 48.5 50 51.25 53 55 NA NA NA NA 80 75 90 43 48 57 61 63 66 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 42 43 43.55 67.33 83.33 73 73 115 40.5 41.3 42 55 59 61 66 71 78 81 83 6 5.3 3.833 44.1 49.5 83.7 119.3 122.3 45 46.25 51 10 5 29 130 131 41.05 41.85 42.25 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 46.9 48.4 48.8 50.1 NA 44.5 44.8 45.2 47 47.5 55.7 54.4 53.9 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 52 54 57 56 55 50 80 118 120 62.2 68.6 73.5 75.7 74 56 59.4 60.1 61 66 90 65.1 61.9 63.6 63.3 62.9 62.6 62.5 45 46.5 48 50.5 53 55.5 56 52.5 52.7 61.8 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 45 47.5 53 NA NA NA 51.6 50.3 50.1 50 49.8 63 61 59 63 57 58 75 78 85 98 99 100 77 77 77 77 87 87 87 87 47 47.5 48.5 80.7 81.2 50 55 54 54 55 59 55 58 NA NA NA NA 52 53 57 46.5 48 50.5 53 55.5 56 56.7 54 55 66.7 74.5 85 48.5 45 47.5 42 NA NA 54 56 57 58 61 64 70 54 50 55 53 54 53 59 45 46.5 47 51 52 |

547 403 253 143 490 400 320 250 200 550 450 400 820 810 780 740 710 670 NA NA NA NA 250 250 240 730 580 550 530 500 460 420 400 400 420 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 97 91 84 29 59 56 53 47 165 157 150 760 710 660 590 530 490 450 390 463 490 540 593 547 403 253 143 81 73 83 NA NA NA NA NA 135 122 106 450 420 390 350 300 450 440 430 460 470 460 450 410 415 450 80 73 65 60 101.5 102.75 103.5 104.75 110 112 47 49 53 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 730 650 610 620 640 55 40 25 15 323 285 218 199 213 422 400 383 361 NA NA 470 473 464 475 473 484 473 666 649 638 612 594 573 569 55 49 38 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 55 53 43 NA NA NA 45 50 54 57 60 320 270 210 240 500 560 730 710 670 560 530 500 300 300 300 300 255 255 255 255 650 620 600 670 490 138 100 90 85 85 80 550 440 NA NA NA NA 49 35 29 649 638 612 594 573 569 550 643 114.33 123.33 113.33 313 70 59 68 54 NA NA 140 89 90 81 80 75 70 140 138 103 90 86 85 80 75 50 40 38 25 |

0.81 1.46 3.52 5.75 0.35 0.34 0.8 0.9 1.4 NA NA NA 6.5 7.1 7.55 7.8 7.9 8.1 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 2.4 0.9 0.5 1.2 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 0.245 0.282 0.298 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 0.62 0.81 1.46 3.52 5.57 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 0.25 0.3 0.39 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 0.38 0.44 0.41 0.45 0.65 0.73 0.79 0.86 0.91 0.95 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 0.8 1.5 3.5 6.7 0.54 0.78 1.28 1.42 1.54 NA NA NA NA 1.5 2.7 0.618 0.609 0.626 0.606 0.612 0.6 0.617 0.196 0.238 0.293 0.341 0.407 0.459 0.537 0.54 0.72 0.84 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 0.2 0.18 0.175 0.17 0.16 0.7 0.578 0.38 0.6 0.98 0.94 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 2 4 4.1 4.9 3.5 5.8 4.3 5 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 3.73 3.93 4.02 4.13 4.59 4.88 4.93 0.99 1.14 1.46 1.86 2.01 NA NA NA NA 5.3 5.05 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 4 4.5 6 8.5 10 |

[7] [7] [7] [7] [8] [8] [8] [8] [8] [9] [9] [9] [10] [10] [10] [10] [10] [10] St_05 St_05 St_05 St_05 [11] [11] [11] [4] [4] [4] [4] [4] [4] [12] [12] [12] [12] [13] [13] [13] [13] [13] [14] [14] [14] [14] [15] [15] [15] [16] [16] [16] [16] [16] [15] [15] [15] [17] [17] [17] [17] [17] [17] [17] [17] [15] [15] [15] [7] [7] [7] [7] [7] [15] [15] [15] [18] [18] [18] [18] [18] [15] [15] [15] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [19] [20] [20] [20] [20] [5] [5] [5] [5] [5] [5] [21] [21] [21] [22] [22] [22] [22] [22] [22] [22] [6] [6] [6] [6] [6] [7] [7] [7] [7] [23] [23] [23] [23] [23] [24] [24] [24] [24] [25] [25] [26] [26] [26] [26] [26] [26] [26] [27] [27] [27] [27] [27] [27] [27] [28] [28] [28] [29] [29] [29] [29] [29] [29] [29] [29] [9] [9] [9] [30] [30] [30] [31] [31] [31] [31] [31] [32] [32] [32] [32] [32] [32] [33] [33] [33] [33] [33] [33] [34] [34] [34] [34] [34] [34] [34] [34] [35] [35] [35] [36] [36] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [38] [38] [39] [39] [39] [39] [40] [40] [40] [41] [41] [41] [41] [41] [41] [41] [42] [42] [42] [42] [42] [43] [43] [43] [43] [44] [44] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [37] [45] [45] [45] [45] [45] |

| Model | Target | Avg. mae | Avg. rsme | Avg_R2 | samples |

| Median Baseline Linear Model (Ridge) Random Forest XGBoost Median Baseline Linear Model (Ridge) Random Forest XGBoost Median Baseline Linear Model (Ridge) Random Forest XGBoost |

Softening Point (°C) Softening Point (°C) Softening Point (°C) Softening Point (°C) Penetration (dmm) Penetration (dmm) Penetration (dmm) Penetration (dmm) Viscosity (Pa.S) Viscosity (Pa.S) Viscosity (Pa.S) Viscosity (Pa.S) |

14.154 14.4171 11.3263 11.0965 206.7258 235.4897 238.3021 230.3848 1.7106 2.557 1.7616 1.7879 |

21.4906 18.6615 16.1304 15.9136 231.3153 275.0583 275.3899 272.7678 2.7141 3.0389 2.1424 2.2275 |

-0.0682 0.1014 0.3674 0.3894 -0.0081 -0.9856 -0.9717 -0.9346 -0.3008 -4.0487 -0.8741 -1.3455 |

193 193 193 193 206 206 206 206 106 106 106 106 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).