1. Introduction

Despite its critical role in saving lives, amputation is associated with considerable physical, psychological, and social challenges which profoundly impact the functionality and body image of the individuals [

1,

2,

3] Body image refers to an individual’s perception, thoughts, and feelings about their body, as well as their awareness of how others perceive and emotionally respond to their appearance [

4,

5,

6,

7]. It is shaped by both internal factors (e.g., age, sex) and external factors (e.g., social and environmental influences) [

8,

9].

Body image plays a critical role in the rehabilitation process following amputation, influencing both psychosocial adjustment and prosthesis use [

10,

11,

12]. An individual’s response to limb loss directly affects their perception of body image, and low satisfaction may lead to prosthesis rejection, limiting functional and social recovery [

13,

14,

15]. Rybarczyk et al. emphasized that amputees must reconcile three distinct body images: the body before limb loss, the body without a prosthesis, and the body with a prosthesis. This highlights the complexity of this adjustment [

16]. Similarly, Horgan and MacLachlan argued that adaptation to a changed body image is a central indicator of psychosocial adjustment, making it a key factor in clinical assessments [

17].

Empirical evidence supports these findings showing that low body image satisfaction is associated with depression, anxiety, poorer quality of life, reduced self-esteem, and lower satisfaction with the prosthesis [

16,

18]. Holzer et al. found that while lower-limb amputees reported diminished body image and quality of life, self-esteem was not significantly affected [

15]. Satisfaction with body image has also been linked to prosthesis satisfaction and use, as well as to higher levels of physical activity [

19]. Gender differences have been noted: Murray and Fox reported that for men, greater functional satisfaction with the prosthesis corresponded with fewer body image disturbances, whereas for women, satisfaction encompassed both aesthetic and functional aspects [

20]. Beyond individual outcomes, Murray et al. underscored the broader social and personal significance of prosthesis use, particularly in restoring a sense of “normal” appearance and everyday life [

8,

9,

13]. Taken together, these findings suggest that systematic assessment of body image is essential for understanding adjustment to limb loss and for guiding rehabilitation interventions.

One of the tools that have been commonly used for assessing body image is the amputee body image scale (ABIS). The ABIS is a unidimensional questionnaire developed by Breakey in 1997 that consists of 20 items to assess how the amputee perceives and feels about his or her experience of amputation. The response to these questions is rated from 1-5 (Never to All the time), the score ranges from 20 to 100; high score indicates high body image disturbance [

1].

The ABIS has been translated into different languages, such as Chinese, Turkish, French, German, Brazilian and Portuguese, and many other versions have shown that the scale has significant psychological and clinical impacts [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. This tool is essential for the rehabilitation services for amputees, and it has been used in numerous studies [

27,

28,

29].

In the Arabic-speaking population, the numbers of validated assessment tools are limited, and most of the available instruments primarily focus on the functional ability of amputees. In a recent study that investigated the relationships between body image, self-esteem, and quality of life in adults who experienced trauma-related limb loss during the Syrian war [

30], the ABIS was translated into Arabic to facilitate assessment in the local population. However, the study did not describe the translation process or clarify whether it followed established international guidelines for culture adaptation, and it also did not perform a full validation or establish the reliability of the translated version. The present study, therefore, aimed to cross-culturally adapt the ABIS for Arabic-speaking lower limb amputees and to determine its validity and reliability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation

The translation of the ABIS into Arabic followed internationally recommended guidelines for the adaptation of self-report measures [

31,

32]. Permission to use and translate the original English ABIS was obtained. The translation process involved three main steps to ensure linguistic accuracy and cultural relevance [

33]. First, a certified translation center translated the original English version into Arabic. The translators had no medical background, minimizing potential bias in interpreting clinical terminology. Next, an independent certified translator, unfamiliar with the original version, conducted a back-translation into English. The back-translated version was then compared with the original ABIS by an English native speaker specializing in prosthetics and orthotics to ensure accuracy and equivalence. Clinics with long/substantial experience in the field carefully reviewed the translated Arabic version to ensure clarity, technical precision, and appropriate terminology, particularly regarding prosthetic and orthotic concepts, body image, and phantom limb phenomena. Minor modifications were suggested to improve linguistic clarity and cultural relevance, without altering the original meaning of the questions. Finally, a pilot test of the Arabic version was conducted with six Arabic-speaking amputees attending routine follow-up appointments at the University of Jordan’s Prosthetics and Orthotics Clinic. The purpose was to assess clarity and comprehensibility. No major comprehension issues were reported, supporting the face validity of the Arabic ABIS and hence its suitability for further use in the study.

2.2. Participants

Ethical approval for the study was obtained prior to piloting and data collection from the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of the Jordanian Ministry of Health (Approval No. MOH/REC/2024/579) on December 26, 2024, and from the Directorate of Medical Education and Training (Approval No. 19037/Information) on December 30, 2024. Participants were recruited via convenience sampling using a previously established database from a governmental rehabilitation center (Al-Bashir Hospital) and a private center (Al Handasiyeh Prosthetic and Orthotic Company) The recruitment period extended from 10 January 2025 to 07 April 2025. Prior to taking part in the study, all participants signed a written informed consent. Inclusion criteria were age over 18 years, regular use of a prosthesis, and no cognitive or mental impairments that could affect the ability to complete the survey. Participants also needed to be proficient in reading, speaking, and understanding Arabic. Data was collected by a trained research team, who administered the questionnaires, ensured accurate recording of responses, and assisted participants as needed throughout the process.

2.3. Measures

The instrument used in this study was the Arabic version of the Amputee Body Image Scale (Ar-ABIS) translated by the authors.

Table 1 shows the original version of ABIS. As in the original version, the Ar-ABIS consists of 20 items designed to assess body image perception among amputees. The scale evaluates the emotional and psychological impact of limb loss and the individual’s feelings towards their body, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“All the time”),

Table 2.

The Ar-ABIS was developed and administered using Google Forms and was structured into three sections. The first section provided participants with an overview of the Ar-ABIS, the aims of the study, confidentiality assurances, and the consent statement. The second section collected demographic data, including participants’ phone number, sex, age, and marital status, alongside clinical information such as the level of amputation, the side affected, the cause of amputation, and the date of amputation. The third section presented the full Ar-ABIS questionnaire. The questionnaire was distributed to participants via their mobile phone numbers and was completed electronically for most of the participants. A hard copy was offered for those who did not wish or could not complete it via their mobile phone. One of the research team members then entered the responses to Google Forms.

2.4. Data Analysis

All data analysis was performed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0.1.0 (142))

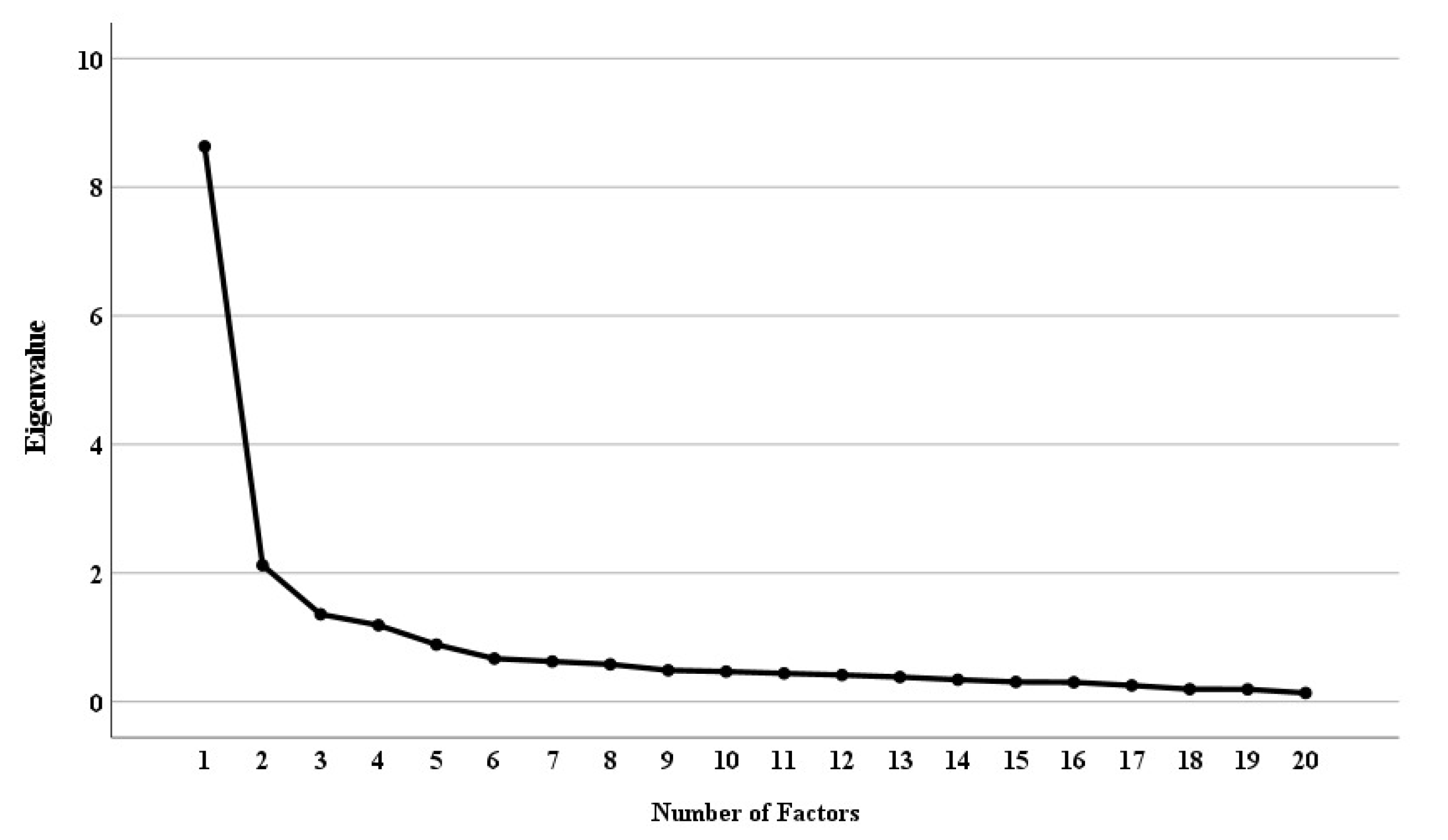

2.5. Validity and Reliability

To evaluate the construct validity of the Arabic version of the ABIS, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted. The data was first assessed for adequacy and suitability for factor analysis using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, respectively. Factor extraction was performed using principal axis factoring with a Varimax rotation, which is an orthogonal rotation. For factor retention, the eigenvalues were considered greater than 1, the scree plot was inspected, and a threshold of 60% of the cumulative percentage of variance was set as an acceptable level to be explained by the factors [

34]. Items with factor loadings below 0.30 were considered for removal. The internal consistency of the scale was examined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients calculated for the overall scale and for each extracted factor.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 100 individuals with lower-limb amputations participated in the study. Their demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 2. Most participants were male (71.3%), while 28.7% were female. Regarding marital status, 68.3% were married, 22.8% were single, 6.9% were widowed, and 2% were divorced.

In terms of amputation level, 57.4% had below-knee amputations, 41.6% had above-knee amputations, and 1% had ankle disarticulations. The right lower limb was more commonly affected (53.5%) than the left (42.6%), and 4% had bilateral amputations. The leading cause of amputation was peripheral vascular disease (31.4%), followed by traffic accidents (24.3%), malignant tumours (18.6%), other causes (17.1%), work-related injuries (5.7%), and gunshot wounds (2.9%).

3.2. Validity

The KMO of 0.898 is a strong enough factor structure, and it is well above 0.6 threshold limit widely used in the literature. The Bartlett test of sphericity is significant (χ2= 1143.09, p < .001), indicating significant correlations between items. Both results confirm that the data were adequate and suitable for factor analysis.

The results of the factor analysis indicated that 4 factors had eigenvalues greater than 1 (8.63, 2.12, 1.36, and 1.19), and the inspection of the scree plot suggested 4 factors (

Figure 1).

After rotation, items were clearly indexed in the 4 Factors. As shown in

Table 3, Factor 1 included

11 items (items 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 10, 14, 15, 18, and 20

), with loadings ranging from 0.53 to 0.81, explaining 30.7% of the variance. Factor 2 comprised

5 items (items 4, 7, 9, 11, and 13

), with loadings between 0.54 and 0.67, explaining 18% of the variance. Factor 3 comprised

3 items (items 3, 12, and 16

), with loadings between 0.55 and 0.86, explaining 10.2% of the variance. Factor 4 comprised

1 item (item 19), with loadings of 0.82, explaining 7.6% of the variance. The 4-factor solution accounted for 66.2% of the total variance.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

| Variable |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| Male |

72 |

71.3 |

| Female |

29 |

28.7 |

| Single |

23 |

22.8 |

| Married |

69 |

68.3 |

| Divorced |

2 |

2.0 |

| Widowed |

7 |

6.9 |

| Below-knee |

58 |

57.4 |

| Above-knee |

42 |

41.6 |

| Ankle disarticulation |

1 |

1.0 |

| Right |

54 |

53.5 |

| Left |

43 |

42.6 |

| Bilateral |

4 |

4.0 |

| Peripheral vascular disease |

22 |

31.4 |

| Traffic accident |

17 |

24.3 |

| Malignant tumor |

13 |

18.6 |

| Other causes |

12 |

17.1 |

| Work-related injury |

4 |

5.7 |

| Gunshot wound |

2 |

2.9 |

Table 4.

Rotated component matrix.

Table 4.

Rotated component matrix.

| No. Item |

Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

Factor 4 |

| 1 |

0.78 |

|

|

|

| 2 |

0.64 |

|

|

|

| 5 |

0.72 |

|

|

|

| 6 |

0.81 |

|

|

|

| 8 |

0.69 |

|

|

|

| 10 |

0.66 |

|

|

|

| 14 |

0.76 |

|

|

|

| 15 |

0.63 |

|

|

|

| 17 |

0.79 |

|

|

|

| 18 |

0.53 |

|

|

|

| 20 |

0.62 |

|

|

|

| |

| 4 |

|

0.64 |

|

|

| 7 |

|

0.69 |

|

|

| 9 |

|

0.54 |

|

|

| 11 |

|

0.61 |

|

|

| 13 |

|

0.67 |

|

|

| |

| 3 |

|

|

0.55 |

|

| 12 |

|

|

0.84 |

|

| 16 |

|

|

0.86 |

|

| |

| 19 |

|

|

|

0.82 |

Based on the factor structure, the number of items within each factor, and the theoretical interpretability of the factors, factor four was removed. Accordingly, the Ar-ABIS can be represented by three main constructs or factors:

3.2.1. Social Appearance Anxiety, Factor 1

This factor included items reflecting social concerns and anxiety regarding body image appearance (items 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 10, 14, 15, 17, 18, and 20). These items represent concerns about others’ perceptions, avoidance behaviors related to the prosthesis, and societal standards of appearance.

3.2.2. Functional and Body Identity Anxiety, Factor 2

This factor comprised items addressing concerns about functionality and body identity post-amputation (items 4, 7, 9, 11, and 13). These items focused on fears of diminished physical ability, protection, and personal identity as an amputee.

3.2.3. Satisfaction and Physical Appearance, Factor 3

This factor grouped items reflecting acceptance and satisfaction with physical appearance (items 3, 12, and 16).

3.3. Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha, demonstrating excellent internal consistency for the overall scale (without item 19) (α = 0.92). Subscale reliability values were as follows: Social Appearance Anxiety (α = 0.926), Functional and Body Identity Anxiety (α = 0.794), and Satisfaction with Physical Appearance (α = 0.718). These results indicate strong internal coherence of items within each subscale.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to translate, adapt, and validate the Arabic version of the Amputee Body Image Scale (Ar-ABIS) for use among Arabic-speaking lower-limb amputees and to assess its psychometric properties. The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) confirmed a four-factor structure explaining 66.5% of the total variance. The fourth factor consists of only one item, which was distinctly separated from other items in the scale. The question, perhaps, was confusing to the prosthesis user, particularly when it was translated to Arabic. Additionally, being about both the anatomical body and the prosthesis at the same time obscured the clarity of this item. Therefore, it was decided to remove this item and consequently the factor. Item 19 has been removed in many international validations of the ABIS as part of the shortened ABIS-R version, including in the English, French, and German adaptations [

3,

21,

24].

The original version of the scale, however, was assumed to be unidimensional, which contradicts our findings. Our finding of the multidimensionality of the scale, nevertheless, is not surprising and is in line with previous adaptations in other languages. The Turkish, Spanish and Chinese version for instance, where a three-factor structure (personal, social, and functional) was observed [

22,

25,

26].

In this study, the identified factors were named slightly differently to reflect the psychosocial nature of the scale. The factors were named: Social Appearance Anxiety, Functional and Body Identity Anxiety, and Satisfaction with Physical Appearance. Factors 1 and 2, were found to be correlated. This might indicate that these two facts are concerned with different aspects of the same construct, which is “Appearance Anxiety”. However, this assumption needs further investigation.

The internal consistency of the Arabic ABIS was excellent, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 for the overall scale, which is consistent with the original English version (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88) [

12] and other validated adaptations in Chinese (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85) [

26], French (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91

) [

21], and Portuguese (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90) [

23], demonstrating that the Arabic translation maintains the scale’s strong reliability across different cultural contexts.

Overall, the Ar-ABIS can be a valid and reliable tool for evaluating body image among amputees. This would provide clinicians and researchers in Arabic-speaking countries with a valuable instrument for assessing psychological adjustment and guiding rehabilitation planning, particularly with the lack of an alternative validated tool in Arabic.

Generally, the scale is culturally relevant; however, it can be further improved to comply with the Arabic culture. For instance, in item 2, wearing shorts is not common and can be unacceptable in certain settings and occasions; therefore, the answer for this item may be related to the social acceptance of revealing the person’s legs or not, regardless of being intact or prosthetic legs.

5. Study Limitations

This study was limited to lower-limb amputees in Jordan, restricting generalizability to broader Arabic-speaking populations. Upper-limb amputees were not included, yet they may experience distinct body image and psychosocial challenges. Recruitment difficulties due to outdated contact information may have affected the sample size. Future longitudinal studies including different amputation types are recommended to assess the Arabic ABIS’s sensitivity and the long-term psychological adjustment of amputees.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, Reem Massarweh.; methodology, Reem Massarweh.; software, Mohammad Sobuh.; validation, Mohammad Sobuh.; formal analysis, Mohammad Sobuh.; investigation, Reem Massarweh.; resources, Reem Massarweh.; data curation, Mohammad Sobuh.; writing—original draft preparation, Reem Massarweh.; writing—review and editing, Reem Massarweh and Mohammad Sobuh.; visualization, Reem Massarweh.; supervision, Reem Massarweh and Mohammad Sobuh.; project administration, Reem Massarweh.; funding acquisition, Reem Massarweh. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author received funding from the University of Jordan (grant number 671/2025/19). This financial support covered the costs associated with obtaining the license to use the ABIS. Detailed information about the funder is available at https://www.ju.edu.jo.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ministry of Health, Jordan (Approval No. MOH/REC/2024/579). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee and with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants through an online written consent form prior to their enrolment in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during this study cannot be shared publicly due to ethical restrictions and the protection of participant confidentiality, in accordance with the approval granted by the Ministry of Health, Jordan. Access to the data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission from the Ministry of Health.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses sincere gratitude to Dr. David Rusaw for his invaluable support. The author also wishes to acknowledge the team who collected the data and the patients who participated in this study for their time, trust, and meaningful contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABIS |

Amputee Body Image Scale |

| Ar-ABIS |

Arabic Amputee Body Image Scale |

References

- Breakey, J.W., Body Image: The Lower-Limb Amputee. JPO: Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics, 1997. 9(2): p. 58-66.

- Fisher, K. and R. Hanspal, Body image and patients with amputations: does the prosthesis maintain the balance? Int J Rehabil Res. 1998 Dec;21(4):355-63. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, P., et al., Body image in people with lower-limb amputation: a Rasch analysis of the Amputee Body Image Scale. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007 Mar;86(3):205-15. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K., et al., Theory assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Thomson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe MN, Tantlee-Dunn. Exacting beauty: theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999.

- Demirdel, S. and Ã. Ãœlger, Body image disturbance, psychosocial adjustment and quality of life in adolescents with amputation. Disabil Health J. 2021 Jul;14(3):101068. [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F., Body image: past, present, and future: Body Image. 2004 Jan;1(1):1-5. [CrossRef]

- Beisheim-Ryan, E.H., et al., Body image and perception among adults with and without phantom limb pain. PM R. 2023 Mar;15(3):278-290. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.D., Being like everybody else: the personal meanings of being a prosthesis user. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(7):573-81. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.D., The social meanings of prosthesis use. J Health Psychol. 2005 May;10(3):425-41. [CrossRef]

- Şimsek, N., G.K. Öztürk, and Z.N. Nahya, The Mental Health of Individuals With Post-Traumatic Lower Limb Amputation: A Qualitative Study. J Patient Exp. 2020 Dec;7(6):1665-1670. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.D. and J. Fox, Body image and prosthesis satisfaction in the lower limb amputee. Disabil Rehabil. 2002 Nov 20;24(17):925-31. [CrossRef]

- Alessa, M., et al., The Psychosocial Impact of Lower Limb Amputation on Patients and Caregivers. Cureus. 2022 Nov 8;14(11):e31248. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.D. and M.J. Forshaw, The experience of amputation and prosthesis use for adults: a metasynthesis. Disabil Rehabil. 2013 Jul;35(14):1133-42. [CrossRef]

- Batten, H., et al., What are the barriers and enablers that people with a lower limb amputation experience when walking in the community? Disabil Rehabil. 2020 Dec;42(24):3481-3487. [CrossRef]

- Holzer, L.A., et al., Body image and self-esteem in lower-limb amputees. PLoS One. 2014 Mar 24;9(3):e92943. [CrossRef]

- Rybarczyk, B., et al., Body Image, Perceived Social Stigma, and the Prediction of Psychosocial Adjustment to Leg Amputation. Rehabilitation psychology, 1995. 40: p. 95-110.

- Horgan, O. and M. MacLachlan, Psychosocial adjustment to lower-limb amputation: a review. Disabil Rehabil. 2004 Jul 22-Aug 5;26(14-15):837-50. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., et al., Prosthetic Satisfaction and Body Image among Lower Limb Amputee: A Cross-sectional Study. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH.

- Wetterhahn, K.A., C. Hanson, and C.E. Levy, Effect of participation in physical activity on body image of amputees. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002 Mar;81(3):194-201. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.D., & Fox, J., Body image and prosthesis satisfaction in the lower limb amputee. Disability and Rehabilitation, 2002. 24(17): p. 925–931.

- Vouilloz, A., et al., Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the ABIS questionnaire for French speaking amputees. Disabil Rehabil. 2020 Mar;42(5):730-736. [CrossRef]

- GÃ33mez-Calcerrada-Garcà a-Navas, E.A., et al., Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Spanish Version of the Amputee Body Image Scale (ABIS-E). Applied Sciences. 14(16): p. 6963.

- Ferreira, L., et al., Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Amputee Body Image Scale: Cultural Adaptation and a Psychometric Analysis. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 125(3): p. 507-524.

- Bekrater-Bodmann, R., The German adaptation of the Amputee Body Image Scale and the importance of psychosocial adjustment to prosthesis use. Sci Rep. 2025 Feb 20;15(1):6204. [CrossRef]

- Bumin, G., et al., Cross cultural adaptation and reliability of the Turkish version of Amputee Body Image Scale (ABIS). J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2009;22(1):11-6. [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.H.-y., et al. Development and Validation of a Body Image Assessment for Patient after Lower Limb Amputation” The Chinese Amputee Body Image Scale-CABIS”. 2005.

- Massarweh, R. and M. Sobuh, The Arabic Version of Trinity Amputation and Prosthetic Experience Scale - Revised (TAPES-R) for Lower Limb Amputees: Reliability and Validity. Disability, CBR & Inclusive Development. Vol. 30 No. 1 (2019): Spring 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, H.R., et al., Activities-specific balance confidence scale: a Rasch evaluation of the Arabic version in lower-limb prosthetic users. Disabil Rehabil. 2025 Apr;47(8):2114-2122. [CrossRef]

- Alhowimel, A., et al., Test-retest reliability of the Arabic translation of the Lower Extremity Functional Status of the Orthotics and Prosthetics Users’ Survey. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2022 Jun 1;46(3):290-293. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F., et al., The relationships between body image, self-esteem and quality of life in adults with trauma-related limb loss sustained in the Syrian war. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 42(3): p. 191-202.

- Guillemin, F., C. Bombardier, and D. Beaton, Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993 Dec;46(12):1417-32. [CrossRef]

- Acquadro, C., et al., Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value Health. 2008 May-Jun;11(3):509-21. [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E., et al., Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000 Dec 15;25(24):3186-91. [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M., et al., Exploratory factor analysis and principal component analysis in clinical studies: Which one should you use?: J Adv Nurs. 2020 Aug;76(8):1886-1889. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).