1. Introduction

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) is a common condition characterized by pain behind or around the patella [

1] resulting from a biomechanical dysfunction between patella and femur [

2]. The pain is associated to activities such as: ascending or descending stairs, running, jumping, sitting with knee flexion, squatting or kneeling on the floor for a period of time [

3]. The annual prevalence of PFP is approximately 25% based on a review that included diverse population groups (USA, UK, Belgium, Denmark, etc.) [

4].

PFP pathogenesis is multifactorial. Thus, quadriceps vastus medialis and vastus lateralis imbalances [

5], dynamic valgus [

6], decreased hip muscle strength [

7], excessive foot pronation [

8] or hamstring stiffness [

9], among others, can lead to patella maltracking [

6] and, consequently, to the onset of this disorder [

6]. This results in PFP to continue to be a challenging musculoskeletal dysfunction in physiotherapy and sports medicine in general [

10].

Anamnesis and physical examination of patients are essential for proper diagnosis and treatment [

11]. Imaging tests do not always correlate with the subject’s symptomatology in PFP [

11,

12]. For this reason, well-known patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) are particularly useful as they enable, from the initial evaluation, learning about patients’ self-assessments of their health and quality of life [

13,

14].

PFP specific questionnaires are the only ones that provide detailed and accurate information about this joint [

15]. Among them, we can find Fulkerson Knee Instability Scale [

16] (FKIS), Kujala Patellofemoral Score [

17] (KPS) and Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score for Patellofemoral pain and osteoarthritis [

18](KOOS-PF), three self-administered questionnaires created and validated specifically for patellofemoral issues.

These questionnaires were originally created and validated in English. Their clinical application across various countries since their inception [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] has led to numerous cross-cultural adaptations into different languages, a procedure that encompasses both linguistic translation and cultural adaptation [

24]. Recent adaptations include KOOS-PF into Spanish [

25], KPS into Indonesian [

26] y FKIS into Italian [

11]. Despite Spanish is the second most widely spoken language globally [

27], FKIS is not yet adapted to this language. In addition to expanding worldwide the use of PROMs in clinics, it would enable the scientific community to learn about the properties of this instrument in Spanish [

27] and to make prospective comparisons among different population groups [

28].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to cross-culturally adapt to Spanish and to analyze the psychometric properties of Fulkerson Knee Instability Scale [

16] in Patellofemoral Pain.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study addressed the cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the FKIS into Spanish. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) reporting guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures [

29] and the Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) [

30] were used.

The main creator of the original questionnaire [

16] was previously notified and gave his approval.

Cross-cultural adaptation involved both cultural and linguistic adaptation (forward-backward translation) of FKIS, as well as the assessment of its psychometric properties concerning reliability and validity. This process was carried out following the international guidelines established by Beaton et al. [

24]:

Translation from English into Spanish by two bilingual people, whose mother tongue was Spanish, independently. One with extensive clinical experience in musculoskeletal disorders and the other with a degree in English and experience in translation and interpreting. Emphasis was placed on the need for translations to be semantic rather than literal, focusing on conceptual equivalence. Two translated Spanish versions of the original FKIS scale were obtained.

Synthesis: Three PFP experts assessed the two versions and agreed on the final version with the translators.

Back-translation: It was conducted independently by two native English speakers fluent in Spanish, one of them with a specialization in musculoskeletal pathology but without prior knowledge of FKIS. Both reached an agreement on the back-translated version.

Review by an expert committee, consisting of the translators involved and the three clinical experts mentioned in the previous phases, for the assessment of the agreed back-translation. Additionally, the new version was compared with the original.

Pretest: A pilot test of the final Spanish version with a sample of 10 subjects with PFP was conducted. Comprehension and/or clarity, appropriateness of vocabulary and relevance of expressions in the Spanish culture were assessed.

Validation of the Spanish version of FKIS.

Participants and Sample

Participants were recruited using a non-random consecutive sampling method in Seville and surrounding areas. Various outreach strategies were employed to engage potential participants, including social media, private clinics, sports clubs, and University dissemination through posters, emails, and direct contacts. Inclusion criteria were: individuals with symptomatic PFP with or without cartilage defect (bilateral or unilateral); aged between 16-55 years, to avoid the appearance of late symptoms of apophysitis (Osgood-Schlatter or Sinding-Larssen-Johansson) and early symptoms of osteoarthritis [

31]; and with Spanish as their mother tongue. Subjects with severe cognitive impairment or with symptomatology or dysfunction of the knee suffering from PFP due to other causes (e.g. joint effusion, degenerative disease, neurodegenerative pathology, tumor process, among others) were excluded.

Except for the descriptive ones, where the participants were considered, the study considered the affected knees as the sample.

Functional Assessment Tools Used

- -

Questionnaire to be adapted into Spanish: FKIS.

FKIS is a specific functional assessment scale for patellofemoral disorders or ligamentous instability of the knee developed by Fulkerson et al. (1990) [

16], derived from the Lysholm Knee Score [

32]. It was first validated by Paxton et al. [

33]. It consists of 7 items with variable scores assessing limp, need for support, stair climbing, squatting, instability, pain, and swelling. Scoring ranged from 0-100 points, where 100 is considered optimal.

- -

Questionnaires used for validation and already adapted to Spanish: KOOS-PF and KPS.

KOOS-PF, created by Crossley et al. (2018) to assesses PFP and/or osteoarthritis [

18], consists of 11 questions related to the pathology: stiffness (1 item), pain (9 items) and quality of life (1 item). Each question has 5 possible answers and is graded on a Likert scale from 0 points (none/never) to 4 points (extreme/always). The KOOS rating scales collection uses a formula [

34] that transforms the score obtained into a range from 0 (maximum impairment) to 100 (optimal state).

KPS, a questionnaire developed by Kujala et al. (1993) to evaluate patellofemoral pathologies [

17], consists of 13 questions, of which 3 refer to pain and physical alterations, 8 refer to a possible functional limitation in different activities, and 2 describe the difficulty in participating in sport activities. Each question has several possible answers (between 3 and 5), and is scored from 0 to 10 points except for some questions which are scored from 0 to 5. The maximum score, 100 points, corresponds to a healthy and asymptomatic state.

Protocol for Action

This study was conducted following the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Virgen Macarena-Virgen del Rocío Hospitals of the Andalusian Public Health System (C.I.0162-N-21) on December 3, 2021. All patients agreed to the Informed Consent after reading the User Information Sheet.

Once the content validity intrinsic to the translation and cultural adaptation process had been carried out, two researchers (FE and CR) experienced in the management of knee PROMs administered the questionnaires over the course of almost a year (March – December, 2023), after having shared the instructions. After collecting anthropometric and pathology data, each participant completed KOOS-PF, KPS and FKIS questionnaires, in that order. It was carried out over two separate sessions spaced 7-10 days apart to prevent participants from recalling their responses, while ensuring they weren’t too distant to avoid potential clinical changes in PFP [

25,

28], as the study did not aim to evaluate intervention effects. Participants with both knees affected answered for each one where applicable. All subjects had the opportunity to ask the researchers any questions they might have had.

Construct validity (convergent and discriminant), external validity, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, agreement, discriminant ability (floor and ceiling effects) and feasibility were analyzed. Note that criterion validity has not been addressed in this research as it is a PROMs study based on COSMIN’s recommendations, where gold standards are not considered [

35].

Construct validity. Concerning convergent validity, the overall FKIS and, KPS and KOOS-PF scores were correlated. Based on previous findings [

11,

33], clinical expertise, and the research team’s knowledge of PROMs, it was hypothesized that, given the nature of these PROMs, the Spanish FKIS would show the highest correlation (

r≥0.8) with the condition-specific KOOS-PF and a high correlation (

r≥0.7) with the body-part-specific KPS. For discriminant validity, the overall FKIS score was correlated with the variables: age, weight (kg), height (cm), body mass index (BMI), time since the onset of pain (months), Q-angle and hours of physical activity of the participants; as they were not determinants in the development or severity of the pathology [

36].

The external validity of FKIS was analyzed to evaluate its applicability and effectiveness in the assessment of PFP in various populations (age and anthropometric, occupational characteristics and amount of physical activity) and contexts (urban/rural areas and meteorological characteristics).

The reliability of the Spanish version of the FKIS was evaluated by assessing internal consistency, temporal stability or reproducibility using the test-retest method, and agreement parameters.

Discriminant ability. Floor and ceiling effects were analyzed for the overall scores and for each item as long as the items included more than 3 response options in order to have at least a 50% chance of the responses not being within the floor/ceiling effect. These effects were considered in the overall scores if at least 15% of the subjects obtained the lowest or the highest scores [

37]. For the items, this would be 75% of the subjects [

27].

For the feasibility of the questionnaire, unanswered items, questions raised by the participants and the time they spent filling in the questionnaire were considered.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was calculated with G*Power 3.1.9.2 based on the FKIS Italian adaptation study [

11]. A confidence level of 95% was considered, i.e. an α error of 5%, and a precision of 7%, resulting in the need for at least 101 knees. The final sample size included a few more subjects to cover possible dropouts.

As for the descriptive data of the participants and the sample, absolute (N) and relative (%) frequencies were considered for qualitative variables. For quantitative variables, normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test when n>50 or Shapiro-Wilks test when n<50. Depending on the sample size, the mean and standard deviation were used for parametric variables, while the median and interquartile range were reported for non-parametric variables.

Construct Validity. Convergent and discriminant validity were assessed using the Spearman correlation coefficient (

r). Its interpretation was according to Martínez-Ortega RM et al. [

38]:

r>0.7,

strong; 0.7≥

r>0.5,

moderate; 0.5≥

r>0.25,

weak; and

r≤0.25,

rare correlation.

Reliability. Internal consistency was evaluated with Cronbach α coefficient. Values between 0.6-0.9 were considered

adequate [

39,

40]. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used for test-retest reliability. The interpretation matches that provided for the correlation coefficients [

41]. Agreement was calculated using the smallest detectable change (SDC), defined as 1.96x√2SEM[

42]. Standard error of the mean (SEM) was previously calculated: SDx√(1−ICC) (SD, Standard Deviation) [

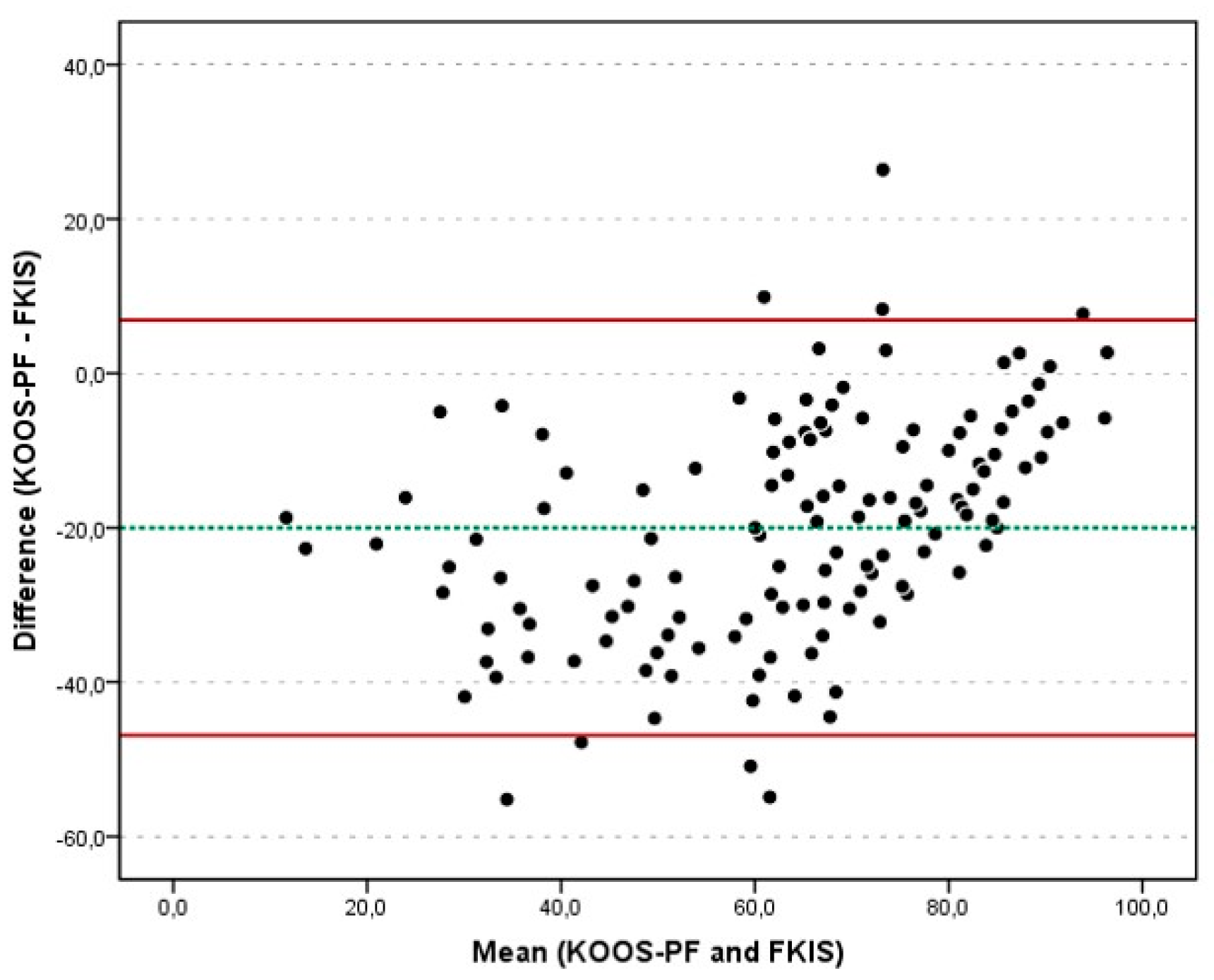

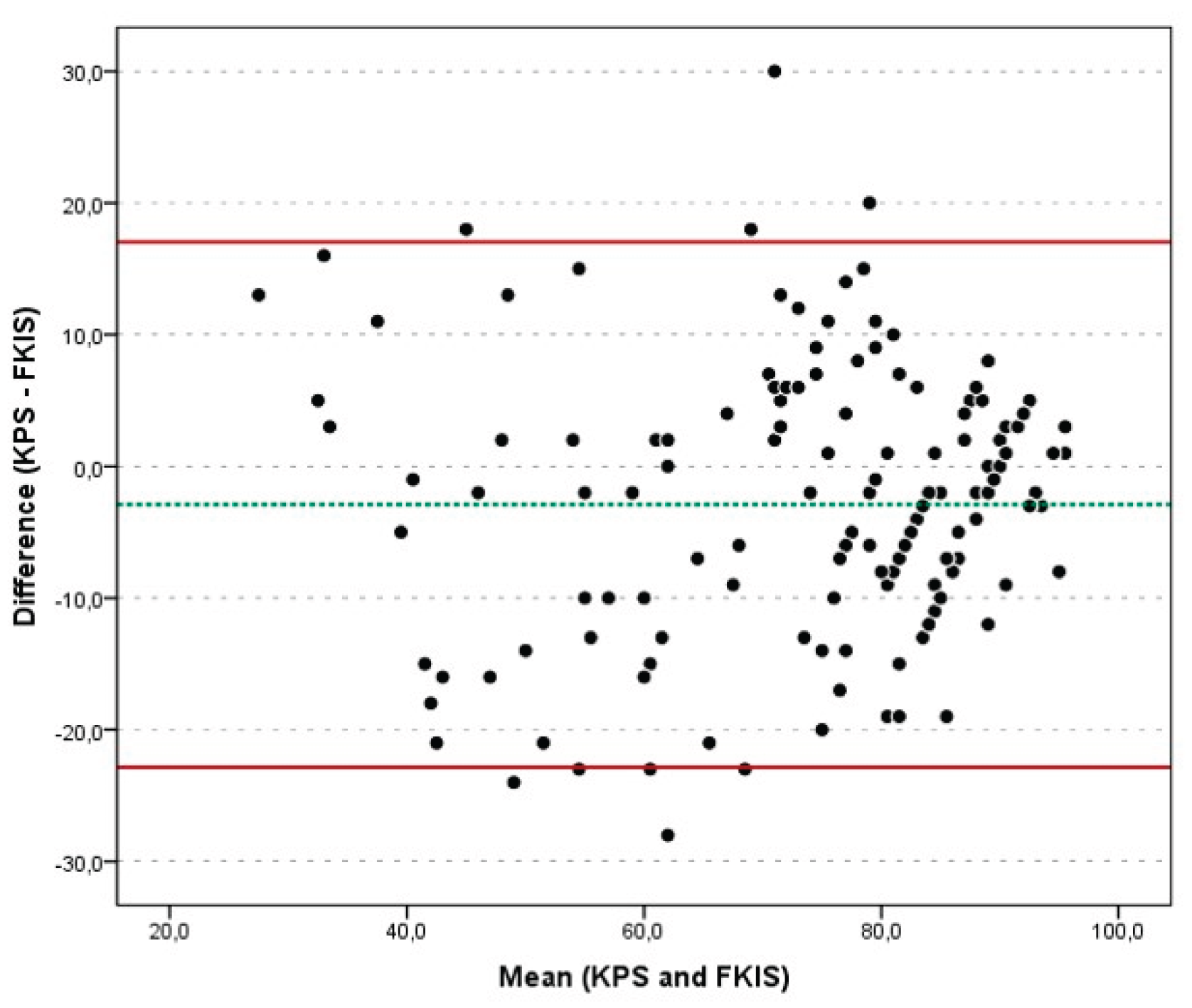

42]. Bland–Altman plots were included to assess homoscedasticity, showing the difference between FKIS and KOOS-PF on the one hand, y FKIS and KPS, on the other; against the mean of FKIS and each questionnaire in each plot.

Ceiling and floor effects were calculated with the percentage of participants with lower and higher scores (10th and 90th percentiles, respectively) [

37].

IBM SPSS STATISTICS 25® software was used for statistical analyses. The p<0.05 values were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The Spanish version of the FKIS carried out in this study can be found at Supplementary Digital Material 1 (Supplementary Text File 1).

3.1. Participants and Sample

The sample consisted of 106 affected knees, exceeding the 70 knees that Hair et al. [

43] suggest (10 subjects per item) for translations, cultural adaptations and validations; and even exceeding COSMIN recommendations [

44] (optimum ≥ 100). Seventy-five subjects were involved, of whom 31 were bilaterally affected. Tables I and II show the descriptive data of the participants and the sample (knees).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the participants.

| Participants |

|

Men (n=24) |

Women (n=51) |

Total (n=75) |

| Age (years) |

|

|

33.7 |

33.5 |

33.6 |

| |

SD |

12.3 |

13.1 |

12.8 |

| |

Med |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

| |

IQR |

21-45 |

22-48 |

21-46 |

| Weight (kg) |

|

|

87.4 |

66.9 |

73.5 |

| |

SD |

12.5 |

12.2 |

15.5 |

| |

Med |

87.5 |

65.0 |

74.0 |

| |

IQR |

77-98 |

57-75 |

61-84 |

| Height (cm) |

|

|

181.0 |

166.0 |

170.8 |

| |

SD |

5.7 |

6.3 |

9.4 |

| |

Med |

180.5 |

165.0 |

170.0 |

| |

IQR |

178-184 |

162-170 |

163-179 |

| BMI |

|

|

26.6 |

24.3 |

25.0 |

| |

SD |

3.7 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

| |

Med |

25.5 |

23.0 |

24.3 |

| |

IQR |

23-30 |

21-26 |

22-29 |

| Impairment |

Unilateral |

N |

15 |

29 |

44 |

| % |

20% |

39% |

59% |

| Bilateral |

N |

9 |

22 |

31 |

| % |

12% |

29% |

41% |

| Impaired limb* |

Dominant |

N |

10 |

17 |

27 |

| % |

23% |

39% |

62% |

| Non- dominant |

N |

5 |

12 |

17 |

| % |

11% |

27% |

38% |

| Physical activity (hours per week) |

|

6.5 |

5.1 |

5.5 |

| SD |

3.9 |

4.7 |

4.5 |

| Med |

5.5 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

| IQR |

4-10 |

1-7 |

3-7 |

| Area of origin |

Urban |

N |

11 |

31 |

42 |

| % |

15% |

41% |

56% |

| Rural |

N |

13 |

20 |

33 |

| % |

17% |

27% |

44% |

| Occupation |

Management / Professional |

N |

3 |

14 |

17 |

| % |

4% |

18.5% |

22.5% |

| Service |

N |

8 |

15 |

23 |

| % |

10.5% |

20% |

30.5% |

| Office work |

N |

6 |

5 |

11 |

| % |

8% |

7% |

15% |

| Student |

N |

7 |

17 |

24 |

| % |

9.5% |

22.5% |

32% |

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample.

| Knees (sample) |

|

Men (n=33) |

Women (n=73) |

Total (n=106) |

| Time with pain (months) |

|

95.0 |

65.4 |

74.6 |

| SD |

76.4 |

56.7 |

64.6 |

| Med |

72.0 |

54.0 |

60.0 |

| IQR |

39-144 |

24-84 |

24-98 |

| Affected knees Q-angle (degrees) |

|

16.0 |

20.0 |

18.8 |

| SD |

3.2 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

| Med |

16.0 |

19.0 |

18.0 |

| IQR |

14-18 |

17-24 |

16-22 |

| FKIS |

|

78.7 |

74.4 |

75.8 |

| SD |

11.5 |

18.0 |

16.4 |

| Med |

80.0 |

82.0 |

80.5 |

| IQR |

69-89 |

62-89 |

67-89 |

| KPS |

|

76.7 |

71.1 |

72.8 |

| SD |

11.4 |

19.7 |

17.7 |

| Med |

78.5 |

78.0 |

78.0 |

| IQR |

73-85 |

55-87 |

62-86 |

| KOOS-PF |

|

59.8 |

53.8 |

55.7 |

| SD |

19.0 |

23.7 |

22.4 |

| Med |

61.4 |

59.1 |

59.1 |

| IQR |

48-68 |

34-73 |

36-73 |

3.2. Validity

Table III shows correlation analysis between FKIS, KPS and KOOS-PF to assess convergent validity.

Table 3.

Correlation among FKIS, KOOS-PF and KPS.

Table 3.

Correlation among FKIS, KOOS-PF and KPS.

| r |

KOOS-PF |

FKIS |

| FKIS |

0.825 (p<0.001) |

|

| KPS |

0.851 (p<0.001) |

0.788 (p<0.001) |

Statistically significant correlation among the 3 questionnaires was obtained (p<0.05). In fact, all were p<0.001. All their correlation coefficients were>0.78, confirming the hypotheses.

Correlation coefficients among FKIS and the descriptive variables (age, weight, height, BMI, time with pain, Q-angle and physical activity) to evaluate discriminant validity were r<0.4 in all cases. Age, BMI and time with pain showed weak correlations (0.4>r>0.25), while weight obtained rare correlation (r=0.2). Height, Q-angle and physical activity were non-significant.

3.3. Reliability

Internal consistency and reproducibility: Cronbach α and ICC were 0.618 (IC95%: 0.534-0.692). The test-retest analysis was statistically significant (p<0,001).

Agreement: Overall mean FKIS, KOOS-PF and KPS scores were 75.75 (±16.39 SD), 55.71 (±22.44 SD) and 72.84 (±17.72 SD), respectively. SEM and SDC were 10.13 and 8.82, respectively. The mean of the differences between FKIS and KOOS-PF were -20.03 (±13.72 SD), with upper limit, 6.86, and lower limit, -46.93; while those between FKIS and KPS were -2.91 (±10.18 SD), with limits of 17.04 and -22.85. Bland-Altman plots (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) showed, in both analyses, that the differences between the 2 evaluations were within the limits of agreement (93.9% of the cases), except for some outliers. No systematic bias was detected, i.e. the zero line was within the 95% CI.

3.4. Discriminant Ability

No participant was below the 10th percentile, while 9.5% were above the 90th percentile. Regarding the items, the percentage of subjects who reached either the lowest or highest scores were: item-3, 49.5%; item-4, 35.9%; item-5, 46.2%; item-6, 4.3%; item-7, 60.4%. No floor or ceiling effects were found.

3.5. Feasibility

The mean time (seconds) to complete FKIS was 236 (±27 SD); KOOS-PF, 270 (±23 SD); and KPS, 299 (±17 SD).

FKIS was completed by all participants, although 17 of them raised questions about item-5. All the participants completed the full FKIS, resulting in a maximum response rate.

4. Discussion

This study approached the cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Spanish version of the FKIS questionnaire. The most relevant findings were strong validity, adequate internal consistency, moderate test-retest reliability; as well as agreement and discriminant ability analysis showed excellent results, making FKIS an adequate tool for assessing PFP in Spanish population.

Translation Process

Regarding the language adaptation process, the two translations of the questionnaire went without difficulty and both back-translations matched the original English version. In item-6 (“Pain”), answer options number 5, “Severe after walking 1 mile”, and number 6, “Severe after walking less than mile” required a modification of the units of measurement, i.e. miles are not commonly used in Spain. The choice was to use “…1 kilómetro” (1 kilometer = 0.62 miles) and “…medio kilómetro” ( kilometer =0.31 miles).

Validity

Our findings showed

strong correlations among FKIS and both KPS (

r=0.79) and KOOS-PF (

r=0.83), being similar to those obtained by Paxton et al. [

33] when correlating FKIS with KPS (

r=0.85) and with Lysholm Knee Score (

r=0.93). The latter value is the highest, probably due to the fact that Lysholm score, although designed for knee disorders in general [

45], is the precursor of the FKIS, and subsequently they have numerous similarities. The Italian adaptation of FKIS [

11], shows a

strong correlation as does our study, but with the Oxford knee score (

r=0.93). The latter was created for arthroplasties and replacements [

45], although it is also used in osteoarthritis [

46].The high correlations between Lysholm and Oxford with FKIS are striking, since the latter is a specific questionnaire for patellofemoral disorders or ligament instability, i.e. the assessment purpose of each questionnaire is different. In addition, statistically significant correlations between FKIS and descriptive data (

weak: age, BMI and time with pain; and

rare: weight), were not clinically relevant, demonstrating good discriminant validity.

In terms of external validity, three dimensions were taken into account: population, circumstances/settings and times [

47]. Thus, the sample was heterogeneous in terms of age, anthropometric characteristics, amount of physical activity and professional characteristics, taking into account urban and rural areas, as well as different time periods (cold, hot and wet seasons). All this in order to avoid biases mainly in the perception of pain [

48,

49,

50].

Reliability

The results obtained showed an

adequate internal consistency and

moderate test-retest reliability. Relative to internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.618), the appropriate correlation between items indicated that all items provided useful information [

51], as in the original validation by Paxton et al. [

33] (Cronbach α = 0.7). This result did possibly not score better because FKIS is a questionnaire for patellofemoral disorders or ligamentous instability, but with some items that are more related to instability. As our sample was only PFP, and therefore with numerous cases of patellar hypomobility, i.e. patellar hyper-pressure and limited movement, the tendency was towards the maximum score (stability intact) in item-5 “

Instability”. Furthermore, the difficulty in standing without additional support (item-2) is more typical in ligamentous instability, so this item tended to have the highest score (99% of the participants), and, consequently, a lower inter-item correlation. This data differs from that observed in the Italian adaptation [

11], which obtained a very high internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.91), indicating redundancy between items.

The ICC for FKIS (0.618) indicated a

moderate test-retest reliability, and therefore, a

moderate temporal stability, in contrast to its original validation [

33] (ICC=0.88) and the Italian adaptation [

11] (ICC=0.94). It should be noted that the latter study [

11] considered a washing period of 5 days. A washing period lower than 8 days would increase the recall effect [

37] and therefore the reliability.

Discriminant Ability

Ceiling and floor effects were not observed in our study, proving that the questionnaire distinguished severe cases from mild ones. This finding supports the validity and reliability of the Spanish version of FKIS. Similarly, the Italian version did not show floor or ceiling effects [

11]. However, Paxton et al. [

33] obtained a ceiling effect (21%) in their study.

Feasibility

FKIS was easily completed by all participants in general, considering that the questionnaire was pertinent to their pathology. However, some participants did not understand being asked about instability (item-5), as they did not associate it with PFP, as previously discussed. In terms of content comprehension, no participant needed clarification, unlike with KOOS-PF and KPS, where some items gave rise to confusion as stated by Chamorro-Moriana et al. in their study [

14]. The average completion time was about 4 minutes. Thus, FKIS was the fastest to complete compared to KOOS-PF and KPS. Finally, the calculation of the final score was simple for the researchers, in contrast to KOOS-PF, where a complex formula is required [

34].

These advantages would justify the use of FKIS as an assessment tool in physical therapy, as well as for evaluating the effectiveness of different surgical techniques affecting the patellofemoral joint, as was already done in patellofemoral autologous osteochondral transplantations [

19,

20,

52], Elmslie-Trillat procedures for dislocation of the patella [

22,

53,

54,

55,

56] or tibial derotation osteotomies [

23].

Regarding the limitations of the study, responsiveness could not be measured because the applications of the Fulkerson Scale did not aim to analyze the effectiveness of any intervention, i.e. our study did not include any treatment. Moreover, the sample consisted solely of affected knees, preventing comparisons between affected and non-affected subgroups. These could be the subject of prospective studies. Furthermore, future studies might explore the cross-cultural validity of new versions of FKIS to enhance its clinical applicability and establishing itself as a recognized benchmark outcome measure in PFP research.

In relation to the strengths of this study, we considered a heterogeneous and large sample, which exceeded: 10 subjects per item recommended by Hair et al. [

43], and even 100 subjects, considered optimal by COSMIN recommendations [

44]. All this provided robustness to the results obtained. Moreover, the appropriate validity and reliability data evidenced by this study make it possible to extend the availability of a useful tool for the assessment of PFP, both at a clinical and research level. The latter idea is the main strength and clinical implication.

5. Conclusions

A cross-cultural adaptation of the Fulkerson Knee Instability Scale into Spanish and an analysis of its psychometric properties in patellofemoral pain subjects were successfully conducted. The Spanish version showed appropriate measurement properties based on its validity, reliability, discriminant ability and feasibility. The results on construct, including convergent and discriminant, and external validity; agreement; and discriminant ability were positively highlighted. Consequently, the validated version of this Scale seems an adequate functional assessment tool for Spanish subjects with patellofemoral pain in clinical and research purposes enlarging its application to new populations.

This study suggests that the questionnaire is especially useful in PFP with instability due to hypermobile patella, as opposed to PFP with patellar stiffness.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Fernando Espuny-Ruiz and Gema Chamorro-Moriana; Data curation, Fernando Espuny-Ruiz, Carmen Ridao-Fernandez, Rocio Aldon-Villegas and Gema Chamorro-Moriana; Formal analysis, Fernando Espuny-Ruiz and Carmen Ridao-Fernandez; Investigation, Fernando Espuny-Ruiz and Carmen Ridao-Fernandez; Methodology, Gema Chamorro-Moriana; Project administration, Gema Chamorro-Moriana; Resources, Rocio Aldon-Villegas; Supervision, Gema Chamorro-Moriana; Writing – original draft, Fernando Espuny-Ruiz and Gema Chamorro-Moriana; Writing – review & editing, Fernando Espuny-Ruiz, Carmen Ridao-Fernandez, Rocio Aldon-Villegas and Gema Chamorro-Moriana.

All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Virgen Macarena-Virgen del Rocío Hospitals of the Andalusian Public Health System (C.I.0162-N-21) on December 3, 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Research Group “Area of Physiotherapy CTS-305” of the University of Seville, Spain; for its contribution in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest with any financial organization concerning the content discussed in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PFP |

Patellofemoral pain |

| PROMs |

Patient reported outcome measures |

| FKIS |

Fulkerson Knee Instability Scale |

| KPS |

Kujala Patellofemoral Score |

| KOOS-PF |

Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score for Patellofemoral pain and osteoarthritis |

| COSMIN |

COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments |

| GRRAS |

Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| ICC |

Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| SDC |

Smallest detectable change |

| SEM |

Standard error of the mean |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

References

- Constantinou, A.; Mamais, I.; Papathanasiou, G.; Lamnisos, D.; Stasinopoulos, D. Comparing Hip and Knee Focused Exercises versus Hip and Knee Focused Exercises with the Use of Blood Flow Restriction Training in Adults with Patellofemoral Pain. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 58 (2), 225–235. [CrossRef]

- Saltychev, M.; Dutton, R. A.; Laimi, K.; Beaupre, G. S.; Virolainen, P.; Fredericson, M. Effectiveness of Conservative Treatment for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 50 (5), 393–401. [CrossRef]

- Tramontano, M.; Pagnotta, S.; Lunghi, C.; Manzo, C.; Manzo, F.; Consolo, S.; Manzo, V. Assessment and Management of Somatic Dysfunctions in Patients With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2020, 120 (3), 165–173. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. E.; Selfe, J.; Thacker, D.; Hendrick, P.; Bateman, M.; Moffatt, F.; Rathleff, M. S.; Smith, T. O.; Logan, P. Incidence and Prevalence of Patellofemoral Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13 (1), e0190892. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Gong, D.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Peng, M.; Wu, B.; Wang, J.; Song, G.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; Dong, Y.; Wang, X. Effects of Neuromuscular Training on Pain Intensity and Self-Reported Functionality for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome in Runners: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Trials 2019, 20 (1), 409. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, W.; Ellermann, A.; Gösele-Koppenburg, A.; Best, R.; Rembitzki, I. V.; Brüggemann, G. P.; Liebau, C. Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. Off. J. ESSKA 2014, 22 (10), 2264–2274. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M. M.; Gamaleldein, M. H.; Hassa, K. A. Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises with or without Additional Hip Strengthening Exercises in Management of Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 49 (5), 687–698.

- Lankhorst, N. E.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M. A.; Van Middelkoop, M. Factors Associated with Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47 (4), 193–206. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Jang, K. M.; Kim, E.; Rhim, H. C.; Kim, H. D. Effects of Static and Dynamic Stretching With Strengthening Exercises in Patients With Patellofemoral Pain Who Have Inflexible Hamstrings: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sports Health 2021, 13 (1), 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Albornoz-Cabello, M.; Barrios-Quinta, C. J.; Escobio-Prieto, I.; Sobrino-Sánchez, R.; Ibáñez-Vera, A. J.; Espejo-Antúnez, L. Treatment of Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome with Dielectric Radiofrequency Diathermy: A Preliminary Single-Group Study with Six-Month Follow-Up. Med. Kaunas Lith. 2021, 57 (5), 429. [CrossRef]

- Cerciello, S.; Corona, K.; Morris, B. J.; Visonà, E.; Maccauro, G.; Maffulli, N.; Ronga, M. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Italian Versions of the Kujala, Larsen, Lysholm and Fulkerson Scores in Patients with Patellofemoral Disorders. J. Orthop. Traumatol. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Orthop. Traumatol. 2018, 19 (1), 18. [CrossRef]

- Horga, L. M.; Hirschmann, A. C.; Henckel, J.; Fotiadou, A.; Di Laura, A.; Torlasco, C.; D’Silva, A.; Sharma, S.; Moon, J. C.; Hart, A. J. Prevalence of Abnormal Findings in 230 Knees of Asymptomatic Adults Using 3.0 T MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2020, 49 (7), 1099–1107. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L. H.; Garratt, A.; Brealey, S. Comparative Responsiveness and Minimal Change of the Knee Quality of Life 26-Item (KQoL-26) Questionnaire. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2013, 22 (9), 2461–2475. [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Moriana, G.; Espuny-Ruiz, F.; Ridao-Fernández, C.; Magni, E. Clinical Value of Questionnaires & Physical Tests for Patellofemoral Pain: Validity, Reliability and Predictive Capacity. PloS One 2024, 19 (4), e0302215. [CrossRef]

- Putman, S.; Rémy, F.; Pasquier, G.; Gougeon, F.; Migaud, H.; Duhamel, A. Validation of a French Patient-Reported Outcome Measure for Patello-Femoral Disorders: The Lille Patello-Femoral Score. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. OTSR 2016, 102 (8), 1055–1059. [CrossRef]

- Fulkerson, J. P.; Becker, G. J.; Meaney, J. A.; Miranda, M.; Folcik, M. A. Anteromedial Tibial Tubercle Transfer without Bone Graft. Am. J. Sports Med. 1990, 18 (5), 490–497. [CrossRef]

- Kujala, U. M.; Jaakkola, L. H.; Koskinen, S. K.; Taimela, S.; Hurme, M.; Nelimarkka, O. Scoring of Patellofemoral Disorders. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. Off. Publ. Arthrosc. Assoc. N. Am. Int. Arthrosc. Assoc. 1993, 9 (2), 159–163. [CrossRef]

- Crossley, K. M.; Macri, E. M.; Cowan, S. M.; Collins, N. J.; Roos, E. M. The Patellofemoral Pain and Osteoarthritis Subscale of the KOOS (KOOS-PF): Development and Validation Using the COSMIN Checklist. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52 (17), 1130–1136. [CrossRef]

- Debieux, P.; dos Santos, M. V. R.; Astur, D. da C.; Sherman, S. L.; Cohen, M.; Kaleka, C. C. Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis versus Osteochondral Autograft Transfer System in Patellar Chondral Lesions: A Comparative Study with a 2-Year Follow-Up. J. Cartil. Jt. Preserv. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Astur, D. C.; Arliani, G. G.; Binz, M.; Astur, N.; Kaleka, C. C.; Amaro, J. T.; Pochini, A.; Cohen, M. Autologous Osteochondral Transplantation for Treating Patellar Chondral Injuries: Evaluation, Treatment, and Outcomes of a Two-Year Follow-up Study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2014, 96 (10), 816–823. [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, H.; Maruyama, Y.; Shitoto, K.; Yokoyama, M.; Kaneko, K. Survival and Clinical Results of a Modified “Crosse de Hockey” Procedure for Chronic Isolated Patellofemoral Joint Osteoarthritis: Mid-Term Follow-Up. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2017, 18 (1), 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Mitani, G.; Maeda, T.; Takagaki, T.; Hamahashi, K.; Serigano, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Sato, M.; Mochida, J. Modified Elmslie-Trillat Procedure for Recurrent Dislocation of the Patella. J. Knee Surg. 2017, 30 (5), 493–499. [CrossRef]

- Manilov, R.; Chahla, J.; Maldonado, S.; Altintas, B.; Manilov, M.; Zampogna, B. High Tibial Derotation Osteotomy for Distal Extensor Mechanism Alignment in Patients with Squinting Patella Due to Increased External Tibial Torsion. Knee 2020, 27 (6), 1931–1941. [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, F.; Bombardier, C.; Beaton, D. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Health-Related Quality of Life Measures: Literature Review and Proposed Guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993, 46 (12), 1417–1432.

- Martinez-Cano, J. P.; Vernaza-Obando, D.; Chica, J.; Castro, A. M. Cross-Cultural Translation and Validation of the Spanish Version of the Patellofemoral Pain and Osteoarthritis Subscale of the KOOS (KOOS-PF). BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14 (1), 220. [CrossRef]

- Mustamsir, E.; Phatama, K. Y.; Pratianto, A.; Pradana, A. S.; Sukmajaya, W. P.; Pandiangan, R. A. H.; Abduh, M.; Hidayat, M. Validity and Reliability of the Indonesian Version of the Kujala Score for Patients With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2020, 8 (5), 2325967120922943. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Sanchez, S.; Hidalgo, M. D.; Gomez, A. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of VISA-P Score for Patellar Tendinopathy in Spanish Population. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2011, 41 (8), 581–591. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Gámez, J.; Pecos-Martín, D.; Kujala, U. M.; Martínez-Merinero, P.; Montañez-Aguilera, F. J.; Romero-Franco, N.; Gallego-Izquierdo, T. Validation and Cultural Adaptation of “Kujala Score” in Spanish. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2016, 24 (9), 2845–2853. [CrossRef]

- Gagnier, J. J.; Lai, J.; Mokkink, L. B.; Terwee, C. B. COSMIN Reporting Guideline for Studies on Measurement Properties of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2021, 30 (8), 2197–2218. [CrossRef]

- Kottner, J.; Audigé, L.; Brorson, S.; Donner, A.; Gajewski, B. J.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Roberts, C.; Shoukri, M.; Streiner, D. L. Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) Were Proposed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64 (1), 96–106. [CrossRef]

- Garratt, A. M.; Brealey, S.; Robling, M.; Atwell, C.; Russell, I.; Gillespie, W.; King, D. Development of the Knee Quality of Life (KQoL-26) 26-Item Questionnaire: Data Quality, Reliability, Validity and Responsiveness. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2008, 6, 48. [CrossRef]

- Tegner, Y.; Lysholm, J. Rating Systems in the Evaluation of Knee Ligament Injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1985, 198, 43–49.

- Paxton, E.; Fithian, D.; Stone, M.; Silva, P. The Reliability and Validity of Knee-Specific and General Health Instruments in Assessing Acute Patellar Dislocation Outcomes. Am J Sports Med 2003, 31 (4), 487–492.

- Tayfur, A.; Salles, J.; Miller, S.; Screen, H.; Morrissey, D. Patellar Tendinopathy Outcome Predictors in Jumping Athletes: Feasibility of Measures for a Cohort Study. Phys Ther Sport 2020, 44, 75–84.

- Terwee, C. B.; Bot, S. D. M.; de Boer, M. R.; van der Windt, D. A. W. M.; Knol, D. L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L. M.; de Vet, H. C. W. Quality Criteria Were Proposed for Measurement Properties of Health Status Questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60 (1), 34–42. [CrossRef]

- Neal, B. S.; Lack, S. D.; Lankhorst, N. E.; Raye, A.; Morrissey, D.; Van Middelkoop, M. Risk Factors for Patellofemoral Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53 (5), 270–281. [CrossRef]

- Donat-Roca, R.; Tárrega, S.; Estapé-Madinabeitia, T.; Escalona-Marfil, C.; Ruíz-Moreno, J.; Seijas, R.; Romero-Cullerés, G.; Roig-Busquets, R.; Mohtadi, N. G. H. Spanish Version of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Quality of Life Questionnaire: Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2023, 11 (7), 23259671231183405. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ortega, R. M.; Tuya-Pendás, L. C.; Martínez-Ortega, M.; Pérez-Abreu, A.; Cánovas, A. M. El Coeficiente de Correlación de Los Rangos de Spearman, Caracterización. Rev. Habanera Cienc. Médicas 2009, 8 (2).

- Todd, C.; Bradley, C. Evaluating the Design and Development of Psychological Scales. In Handbook of Psychology and Diabetes: A Guide to Psychological Measurement in Diabetes Research and Practice; Harwood Academic Publishers: Chur, Switzerland, 1994.

- Loewenthal, K. An Introduction to Psychological Tests and Scales; UCL Press Limited: London, UK, 1996.

- Fleiss, J. L. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments; Wiley: New York, 1999.

- de Vet, H. C. W.; Terwee, C. B.; Knol, D. L.; Bouter, L. M. When to Use Agreement versus Reliability Measures. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2006, 59 (10), 1033–1039. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Análisis Multivariante, 5th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Madrid, Spain, 2004.

- Terwee, C. B.; Prinsen, C. A. C.; Chiarotto, A.; Westerman, M. J.; Patrick, D. L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L. M.; de Vet, H. C. W.; Mokkink, L. B. COSMIN Methodology for Evaluating the Content Validity of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Delphi Study. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2018, 27 (5), 1159–1170. [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Moriana, G.; Perez-Cabezas, V.; Espuny-Ruiz, F.; Torres-Enamorado, D.; Ridao-Fernández, C. Assessing Knee Functionality: Systematic Review of Validated Outcome Measures. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 65 (6), 101608. [CrossRef]

- Harris, K. K.; Dawson, J.; Jones, L. D.; Beard, D. J.; Price, A. J. Extending the Use of PROMs in the NHS--Using the Oxford Knee Score in Patients Undergoing Non-Operative Management for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Validation Study. BMJ Open 2013, 3 (8), e003365. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L. External Validity, Generalizability, and Knowledge Utilization. J Nurs Sch. 2004, 36 (1), 16–22. [CrossRef]

- Barros Dos Santos, A. O.; Pinto De Castro, J. B.; Da Silva, Di. R.; Oliveira Simões Ribeiro, I. De; Lima, V. P.; De Souza Vale, R. G. Correlation between Pain, Anthropometric Measurements, Stress and Biochemical Markers in Women with Low Back Pain. Pain Manag. 2021, 11 (6), 661–667. [CrossRef]

- Kivrak, Y.; Kose-Ozlece, H.; Ustundag, M. F.; Asoglu, M. Pain Perception: Predictive Value of Sex, Depression, Anxiety, Somatosensory Amplification, Obesity, and Age. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 1913–1918. [CrossRef]

- Strigo, I. A.; Carli, F.; Bushnell, M. C. Effect of Ambient Temperature on Human Pain and Temperature Perception. Anesthesiology 2000, 92 (3), 699–707. [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, H. C.; Campo-Arias, A. Aproximación al Uso Del Coeficiente Alfa de Cronbach. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr 2005, 34 (4), 572–580.

- Cohen, M.; Amaro, J. T.; De Souza Campos Fernandes, R.; Arliani, G. G.; Da Costa Astur, D.; Kaleka, C. C.; Skaf, A. Osteochondral Autologous Transplantation for Treating Chondral Lesions in the Patella. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2012, 47 (3), 348–353. [CrossRef]

- Dannawi, Z.; Khanduja, V.; Palmer, C. R.; El-Zebdeh, M. Evaluation of the Modified Elmslie-Trillat Procedure for Patellofemoral Dysfunction. Orthopedics 2010, 33 (1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Barber, F. A.; McGarry, J. E. Elmslie-Trillat Procedure for the Treatment of Recurrent Patellar Instability. Arthrosc. - J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2008, 24 (1), 77–81. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Wada, Y.; Minamide, M.; Tsuchiya, A.; Moriya, H. Deterioration of Long-Term Clinical Results after the Elmslie-Trillat Procedure for Dislocation of the Patella. J. Bone Jt. Surg. - Ser. B 2002, 84 (6), 861–864. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Jones, S.; Bickerstaff, D. R.; Smith, T. W. D. Functional Evaluation of the Modified Elmslie-Trillat Procedure for Patello-Femoral Dysfunction. Knee 2001, 8 (4), 287–292. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).