Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

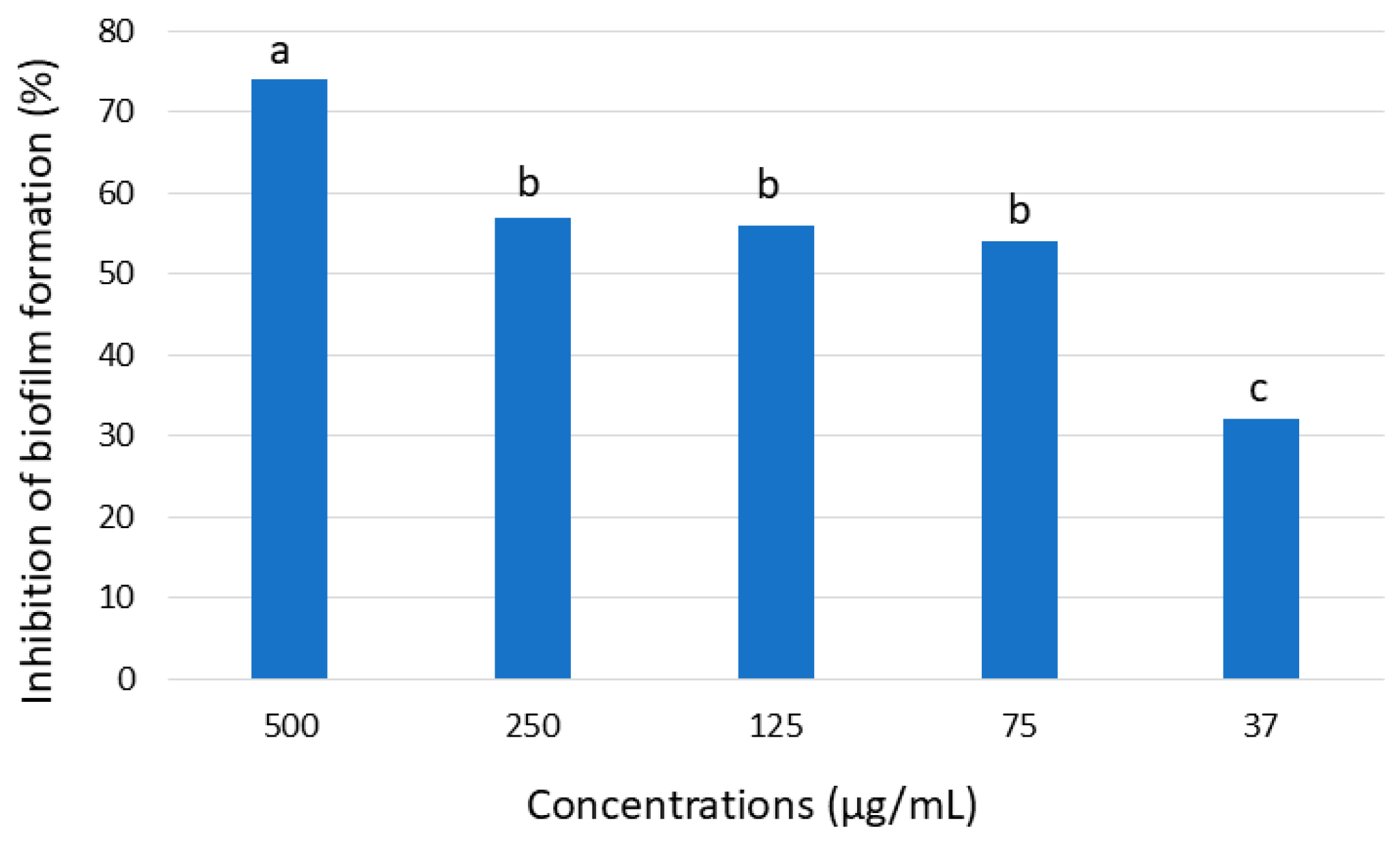

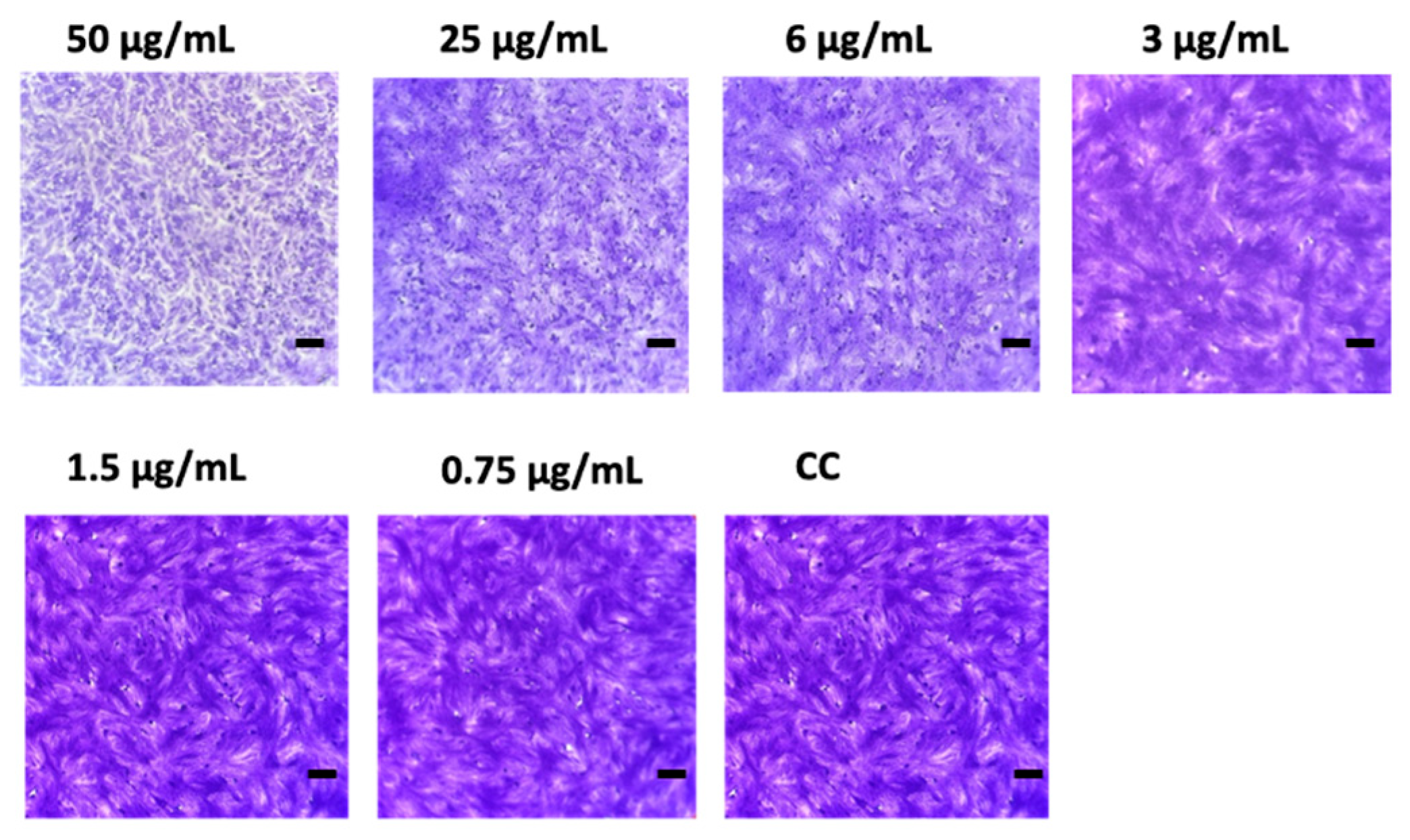

In this study, seven Pleosporaceae strains isolated from the seagrass Posidonia oceanica and the jellyfish Pelagia noctiluca in the central Tyrrhenian Sea were characterized using a polyphasic approach (morpho-physiological, molecular, and phylogenetic analyses). Based on multi-locus phylogenetic inference and morphological characters, a new species, Tamaricicola fenicis was proposed. Multi-locus phylogenetic analyses, using the nuclear ribosomal regions of DNA (nrITS1-nr5.8S-nrITS2, nrLSU, and nrSSU) as well as the rpb-2 and tef-1α gene sequences, strongly supported the new taxon. The phylogenetic inference, estimated using Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference, clearly indicates that Tamaricicola fenicis sp. nov. forms a distinct clade within the monospecific genus Tamaricicola. The antimicrobial activity of the chloroformic and butanolic extracts from malt agar cultures of the new species exhibited interesting antiviral and antibiofilm properties. In particular, a MIC of 3.0 µg/mL was observed against the Echovirus E11 in Vero-76 cells; moreover, a biofilm BIC50 reduction at 53 µg/mL was observed against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Isolates

2.2. Morphological Analysis on Different Media

2.3. Molecular Analysis

2.4. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analyses

2.5. Antimicrobial and Antiviral Activity

2.5.1. Cultivation and Extraction

2.5.2. Antimicrobial Activity Assay

2.5.3. Antiviral Activity Assay

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Inference

3.2. Taxonomy

3.3. Screening for Antimicrobial and Antiviral Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Jones, E.G.; Pang, K.L.; Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Scholz, B.; Hyde, K.D.; Boekhout, T.; Ebel, R.; Rateb, M.E.; Henderson, L.; Sakayaroj, J.; et al. An online resource for marine fungi. Fungal Divers. 2019, 96, 347–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualetti, M.; Braconcini, M.; Barghini, P.; Gorrasi, S.; Schillaci, D.; Ferraro, D.; et al. From marine neglected substrata new fungal taxa of potential biotechnological interest: the case of Pelagia noctiluca. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1473269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, V.; Barghini, P.; Gorrasi, S.; Massimiliano, F.; Pasqualetti, M. Marine fungi: A potential source of novel enzymes for environmental and biotechnological applications. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2019, 20, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualetti, M.; Barghini, P.; Giovannini, V.; Fenice, M. High production of chitinolytic activity in halophilic conditions by a new marine strain of Clonostachys rosea. Molecules 2019, 24, 101880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.M.; Hai, Y.; Gu, Y.C.; Wang, C.Y.; Shao, C.L. Chemical and bioactive marine natural products of coral-derived microorganisms (2015–2017). Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 6930–6941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, L.; Saladino, R.; Barghini, P.; Fenice, M.; Pasqualetti, M. Production and identification of two antifungal terpenoids from the Posidonia oceanica epiphytic Ascomycota Mariannaea humicola IG100. Microb. Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.F.; Xu, L.; Wei, M.Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Gu, Y.C.; Shao, C.L. Recent progresses in marine microbial-derived antiviral natural products. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2020, 43, 1215–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, F.; AlNadhari, S.; Al-Homaidan, A.A. Marine microorganisms as an untapped source of bioactive compounds. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualetti, M.; Gorrasi, S.; Giovannini, V.; Braconcini, M.; Fenice, M. Polyextremophilic chitinolytic activity by a marine strain (IG119) of Clonostachys rosea. Molecules 2022, 27, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, K.L.; Jones, E.G.; Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Adams, S.J.; Alves, A.; Azevedo, E.; et al. Recent progress in marine mycological research in different countries, and prospects for future developments worldwide. Bot. Mar. 2023, 66, 239–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabon, M.S.; Jones, E.G.; Pang, K.L.; Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Jin, J.; Devadatha, B.; et al. Updates on the classification and numbers of marine fungi. Bot. Mar. 2023, 66, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: www.indexfungorum.org (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Dong, J.; Chen, W.; Crane, J.L. Phylogenetic studies of the Leptosphaeriaceae, Pleosporaceae and some other Loculoascomycetes based on nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycol. Res. 1998, 102, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyawansa, H.A.; Thambugala, K.M.; Manamgoda, D.S.; Jayawardena, R.; Camporesi, E.; Boonmee, S.; et al. Towards a natural classification and backbone tree for Pleosporaceae. Fungal Divers. 2015, 71, 85–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Garcia, D.; García, D.; Cano-Lira, J.F.; Gené, J. Two novel genera, Neostemphylium and Scleromyces (Pleosporaceae) from freshwater sediments and their global biogeography. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thambugala, K.M.; Daranagama, D.A.; Phillips, A.J.; Bulgakov, T.S.; Bhat, D.J.; Camporesi, E.; et al. Microfungi on Tamarix. Fungal Divers. 2017, 82, 239–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Menéndez, V.; Crespo, G.; De Pedro, N.; Diaz, C.; Martín, J.; Serrano, R.; et al. Fungal endophytes from arid areas of Andalusia: high potential sources for antifungal and antitumoral agents. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utermann, C.; Echelmeyer, V.A.; Oppong-Danquah, E.; Blümel, M.; Tasdemir, D. Diversity, bioactivity profiling and untargeted metabolomics of the cultivable gut microbiota of Ciona intestinalis. Mar. Drugs 2020, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Hamm, P.S.; Gadek, C.R.; Mann, M.A.; Steinberg, M.; Montoya, K.N.; Behnia, M.; et al. Phylogenetic and ecological drivers of the avian lung mycobiome and its potentially pathogenic component. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Liu, X.X.; Zhang, W.J.; Hu, S.S.; Lin, L.P.; et al. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory compounds from a marine fungus Pleosporales sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 6183–6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jiao, R.H.; Yao, L.Y.; Han, W.B.; Lu, Y.H.; Tan, R.X. Control of fungal morphology for improved production of a novel antimicrobial alkaloid by marine-derived fungus Curvularia sp. IFB-Z10 under submerged fermentation. Process Biochem. 2016, 51, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Meng, Z.H.; Mu, X.; Yue, Y.F.; Zhu, H.J. Absolute configuration of bioactive azaphilones from the marine-derived fungus Pleosporales sp. CF09-1. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Sun, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, T.; Li, D.; Che, Q. Antibacterial phenalenone derivatives from marine-derived fungus Pleosporales sp. HDN1811400. Tetrahedron Lett. 2021, 68, 152938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualetti, M.; Giovannini, V.; Barghini, P.; Gorrasi, S.; Fenice, M. Diversity and ecology of culturable marine fungi associated with Posidonia oceanica leaves and their epiphytic algae Dictyota dichotoma and Sphaerococcus coronopifolius. Fungal Ecol. 2020, 44, 100906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braconcini, M.; Gorrasi, S.; Fenice, M.; Barghini, P.; Pasqualetti, M. Rambellisea gigliensis and Rambellisea halocynthiae gen. et spp. nov. (Lulworthiaceae) from the marine tunicate Halocynthia papillosa. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehner, S.A.; Buckley, E. A Beauveria phylogeny inferred from nuclear ITS and EF1-α sequences: evidence for cryptic diversification and links to Cordyceps teleomorphs. Mycologia 2005, 97, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerase II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Gibson, T.J.; Plewniak, F.; Jeanmougin, F.; Higgins, D.G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4876–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. 1990, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Osieck, E.R.; Shivas, R.G.; Tan, Y.P.; Bishop-Hurley, S.L.; Esteve-Raventós, F.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 1478–1549. Persoonia 2023, 50, 158–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, M.F.; Esteves, A.C.; Alves, A. Marine fungi: opportunities and challenges. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovio, E.; Garzoli, L.; Poli, A.; Prigione, V.; Firsova, D.; McCormack, G.; et al. The culturable mycobiota associated with three Atlantic sponges, including two new species: Thelebolus balaustiformis and T. spongiae. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2018, 1, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuomo, V.; Vanzanella, F.; Fresi, E.; Cinelli, F.; Mazzella, L. Fungal flora of Posidonia oceanica and its ecological significance. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1985, 84, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, V.; Jones, E.B.G.; Grasso, S. Occurrence and distribution of marine fungi along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 1988, 21, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, L.; Bruno, M.; Voyron, S.; Anastasi, A.; Gnavi, G.; Miserere, L.; Varese, G.C. Diversity, ecological role and potential biotechnological applications of marine fungi associated to the seagrass Posidonia oceanica. New Biotechnol. 2013, 30, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnavi, G.; Ercole, E.; Panno, L.; Vizzini, A.; Varese, G.C. Dothideomycetes and Leotiomycetes sterile mycelia isolated from the Italian seagrass Posidonia oceanica based on rDNA data. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohník, M.; Borovec, O.; Župan, I.; Vondrášek, D.; Petrtýl, M.; Sudová, R. Anatomically and morphologically unique dark septate endophytic association in the roots of the Mediterranean endemic seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Mycorrhiza 2015, 25, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohník, M.; Borovec, O.; Kolařík, M.; Sudová, R. Fungal root symbionts of the seagrass Posidonia oceanica in the central Adriatic Sea revealed by microscopy, culturing and 454-pyrosequencing. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2017, 583, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohník, M.; Borovec, O.; Kolaříková, Z.; Sudová, R.; Réblová, M. Extensive sampling and high-throughput sequencing reveal Posidoniomyces atricolor gen. et sp. nov. (Aigialaceae, Pleosporales) as the dominant root mycobiont of the Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica. MycoKeys 2019, 55, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, A.; Bovio, E.; Ranieri, L.; Varese, G.C.; Prigione, V. Fungal diversity in the Neptune forest: Comparison of the mycobiota of Posidonia oceanica, Flabellia petiolata, and Padina pavonica. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torta, L.; Burruano, S.; Giambra, S.; Conigliaro, G.; Piazza, G.; Mirabile, G.; et al. Cultivable fungal endophytes in roots, rhizomes and leaves of Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile along the coast of Sicily, Italy. Plants 2022, 11, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panebianco, C.; Tam, W.Y.; Jones, E.B.G. The effect of pre-inoculation of balsa wood by selected marine fungi and their effect on subsequent colonisation in the sea. Fungal Divers. 2002, 10, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.Y.; Qi, Y.L.; Cai, L. Induction of sporulation in plant pathogenic fungi. Mycology 2012, 3, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, I.C.; Rathnayaka, A.R.; Marasinghe, D.S.; Calabon, M.S.; Gentekaki, E.; Lee, H.B.; et al. Morphological approaches in studying fungi: collection, examination, isolation, sporulation and preservation. Mycosphere 2020, 11, 2678–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualetti, M.; Mulas, B.; Rambelli, A.; Tempesta, S. Saprotrophic litter fungi in a Mediterranean ecosystem: Behaviour on different substrata. Plant Biosystems, 2014, 148, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying L, Qiang S, Jinbo X, Binzhi R, Hua Z, Yong S et al. Genetic variation and evolutionary characteristics of Echovirus 11: new variant within genotype D5 associated with neonatal death found in China. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2024; 13, 2361814. [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, H.J.; Leyssen, P.; Puerstinger, G.; Muigg, A.; Neyts, J.; De Palma, A.M. Towards the design of combination therapy for the treatment of enterovirus infections. Antivir. Res. 2011, 90, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, M. Enterovirus A71 antivirals: past, present, and future. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 1542–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Molecular Marker (Primer F/ Primer R) |

Thermocycler conditions | References |

| nrITS (ITS5/ITS4) |

94 °C x 2 min, (94 °C x 40 s, 55 °C: 30 s, 72 °C: 45 s) × 35 cycles; 72 °C: 10 min | [27] |

| nrLSU (LR0R/LR7) |

95 °C: 10 min, (95 °C: 60 s, 50 °C: 30 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 40 cycles; 72 °C: 10 min | [28] |

| nrSSU (NS1/NS4) |

95 °C: 10 min, (95 ◦C: 60 s, 50 °C: 30 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 40 cycles; 72 °C: 10 min | [27] |

| tef-1α (EF1-983F/EF1-2218R) |

95 °C: 10 min, (95 °C: 30 s, 55 °C: 30 s, 72 °C: 60 s) × 40 cycles; 72 °C: 10 min | [29] |

| rpb-2 (fRPB2-5F/fRPB2-7CR) |

94 °C: 5 min, (94 °C: 45 s, 60 °C: 45 s, 72 °C: 120 s) × 5 cycles; (94 °C: 45 s, 58 °C: 45 s, 72 °C: 120 s) × 5 cycles; (94 °C: 45 s, 54 °C: 45 s, 72 °C: 120 s) × 30 cycles; 72 °C: 8 min | [30] |

| Species | Strain | GenBank Accesion Number | ||||

| nrITS | nrLSU | nrSSU | rpb-2 | tef-1α | ||

| Alternaria alternata | MFLUCC 14-1184 | KP334711 | KP334701 | KP334721 | KP334737 | KP334735 |

| A. alternata | MFLUCC 14-0756 | KP334712 | KP334702 | KP334722 | KP334738 | KP334736 |

| Alternaria solani | CBS 116651 | KC584217 | KC584306 | KC584562 | KC584430 | KC584688 |

| Alternaria tenuissima | MFLUCC140441 | KU752186 | KU561876 | KU870907 | - | KU577440 |

| Alternaria cruciatus | CBS 171.63 | MH858254 | MH869856 | - | ON703247 | ON542234 |

| A. cruciatus | CBS 536.92 | ON773141 | ON773155 | - | ON703248 | ON542235 |

| Bipolaris cynodontis | ICMP 6128 | JX256412 | JX256380 | - | - | JX266581 |

| Bipolaris maydis | CBS 136.29 | MH855024 | MH866491 | - | HF934828 | - |

| Bipolaris melinidis | BRIP 12898 | JN192382 | JN600994 | - | - | KM093771 |

| Clathrospora elynae | CBS 196.54 | MH857290 | KC584371 | KC584629 | KC584496 | - |

| CBS 161.51 | KC584370 | KC584628 | KC584495 | - | - | |

| Cnidariophoma eilatica | CPC 44117 | OQ628480 | OQ629062 | - | OQ627943 | - |

| Comoclathris incompta | CBS 467.76 | KY940770 | GU238087 | GU238220 | KC584504 | - |

| Comoclathris sedi | MFLUCC13-0817 | KP334715 | KP334705 | KP334725 | - | - |

| Comoclathris spartii | MFLUCC13-0214 | KM577159 | KM577160 | KM577161 | - | - |

| Curvularia heteropogonis | CBS 284.91 | MH862253 | LT631396 | - | HF934821 | - |

| Curvularia lunata | CBS 730.96 | MG722981 | LT631416 | - | HF934813 | - |

| Curvularia ravenelii | BRIP 13165 | JN192386 | JN601001 | - | - | JN601024 |

| Decorospora gaudefroyi | CBS 250.60 | MH857974 | MH869526 | - | - | - |

| Decorospora gaudefroyi | CBS 332.63 | MH858305 | MH869915 | - | - | - |

| Dichotomophthora lutea | CBS 145.57 | MH857676 | NG069497 | - | LT990634 | - |

| D. portulacae | CBS 174.35 | NR158421 | MH867137 | - | LT990638 | LT990668 |

| Exserohilum monoceras | CBS 239.77 | LT837474 | LT883405 | - | LT852506 | - |

| Exserohilum rostratum | CBS 128061 | KT265240 | MH877986 | - | LT715752 | - |

| Exserohilum turcicum | CBS 387.58 | MH857820 | LT883412 | - | LT852514 | - |

| Gibbago trianthemae | NFCCI 1886 | HM448998 | - | - | - | - |

| Gibbago trianthemae | GT-VM | KJ825852 | - | - | - | - |

| Halojulella avicenniae | BCC 20173 | - | GU371822 | GU371830 | GU371786 | GU371815 |

| Johnalcornia aberrans | CBS 510.91 | MH862272 | KM243286 | - | LT715737 | - |

| Johnalcornia aberrans | BRIP 16281 | KJ415522 | KJ415475 | - | - | KJ415473 |

| Neostemphylium polymorphum | FMR 17886 | OU195609 | OU195892 | - | OU196009 | ON368192 |

| FMR 17889 | OU195610 | OU195914 | - | OU196957 | ON368193 | |

| FMR 17893 | OU195631 | OU195915 | - | OU197255 | ON368194 | |

| Paradendriphyella arinariae | CBS 181.58 | MH857747 | KC793338 | NG062992 | DQ435065 | - |

| Paradendriphyella salina | CBS 302.84 | MH873443 | KC584325 | KC584583 | KC584450 | KC584709 |

| Paradendriphyella salina | CBS 142.60 | MH857928 | MH869472 | KF156098 | DQ435066 | DQ414251 |

| Porocercospora seminalis | CPC 21332 | HF934941 | HF934862 | - | HF934843 | - |

| Porocercospora seminalis | CPC 21349 | HF934945 | HF934861 | - | HF934845 | - |

| Pyrenophora dictyoides | DAOM 75616 | JN943654 | JN940079 | JN940962 | JN993617 | - |

| Pyrenophora dictyoides | DAOM 63666 | JN943653 | JN940080 | - | - | - |

| Pyrenophora phaeocomes | DAOM 222769 | JN943649 | JN940093 | JN940960 | DQ497614 | DQ497607 |

| P. pseudoerythrospila | CBS 127931 | NR164465 | NG066344 | - | - | - |

| Tamaricicola fenicis | IG108 | MG977425 | MG976984 | MG976980 | PX411237 | PX431678 |

| Tamaricicola tyrrhenica | IG114 | - | PX091581 | PX412374 | - | PX431679 |

| Tamaricicola tyrrhenica | PN23 | OP793911 | PX412372 | PX412375 | PX431674 | PX431680 |

| Tamaricicola tyrrhenica | PN28 | OP793912 | PX412373 | PX412376 | PX431675 | PX431681 |

| Tamaricicola tyrrhenica | PN32 | OP793995 | PX412371 | PX412377 | PX431676 | PX431682 |

| Tamaricicola tyrrhenica | PN38 | ON807355 | PX091580 | PX412378 | ON887328 | ON952522 |

| Tamaricicola tyrrhenica | PN39 | OP794025 | PX412370 | PX412379 | PX431677 | PX431683 |

| Tamaricicola muriformis | MFLUCC150488 | KU752187 | KU561879 | KU870909 | KU820870 | KU577441 |

| Tamaricicola muriformis | MFLUCC150489 | KU752188 | KU729857 | KU870910 | - | KU600013 |

| Tamaricicola muriformis | MFLUCC150490 | KU752189 | KU729856 | KU870911 | - | KU600014 |

| Tamaricicola muriformis | MFLUCC160488 | KU900317 | KU900293 | KU870908 | - | - |

| Tamaricicola sp. | CF-288959 | MG065814 | - | - | - | - |

| CF-288916 | MG065815 | - | - | - | - | |

| CF-090279 | MG065816 | - | - | - | - | |

| CHG59 | MW064152 | - | - | - | - | |

| 56405C | PP804371 | - | - | - | - | |

| 56406A | PP804313 | - | - | - | - | |

| Scleromyces submersus | FMR 18289 | OU195893 | OU195959 | - | OU197244 | OU196982 |

| Stemphylium lycopersici | CNU 070067 | JF417683 | - | - | JF417698 | JX213347 |

| Stemphylium vesicarium | CBS 191.86 | MH861935 | JX681120 | - | KC584471 | KC584731 |

| Stemphylium vesicarium | MFLUCC 140442 | KU752185 | KU561878 | KU870906 | - | - |

| Typhicola typharum | CBS 145043 | MK442590 | MK442530 | - | MK442666 | MK442696 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).