Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability Integration

2.2. Existing Frameworks’ Contributions and Limitations

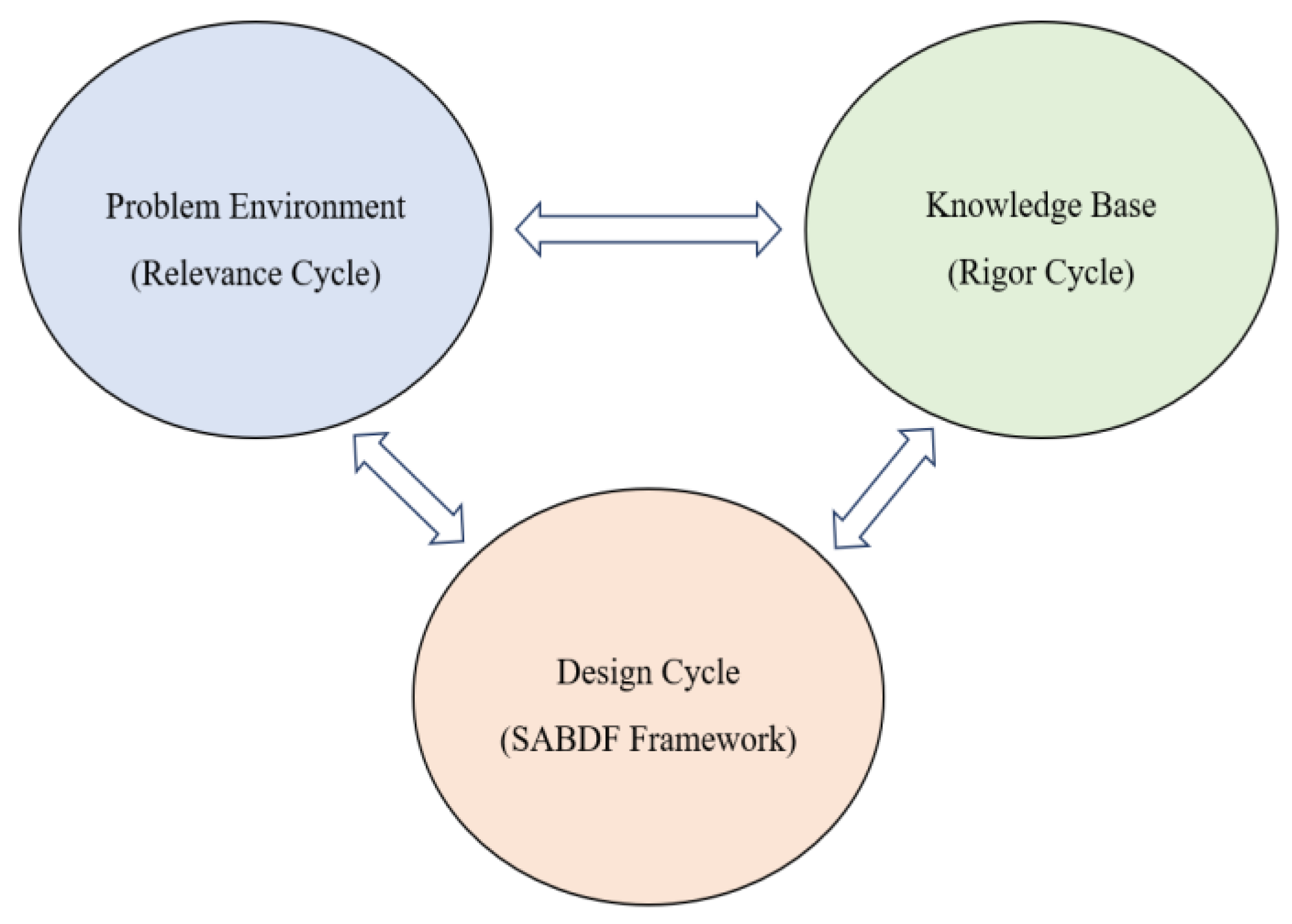

2.3. Design Science Bridging

2.4. Stakeholder/Resource Theories

2.5. Data Infrastructure

2.6. Synthesis & Research Gap

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overview

3.2. Research Paradigm and Justification

3.3. Problem Environment and Knowledge Base

3.4. Framework Design and Development

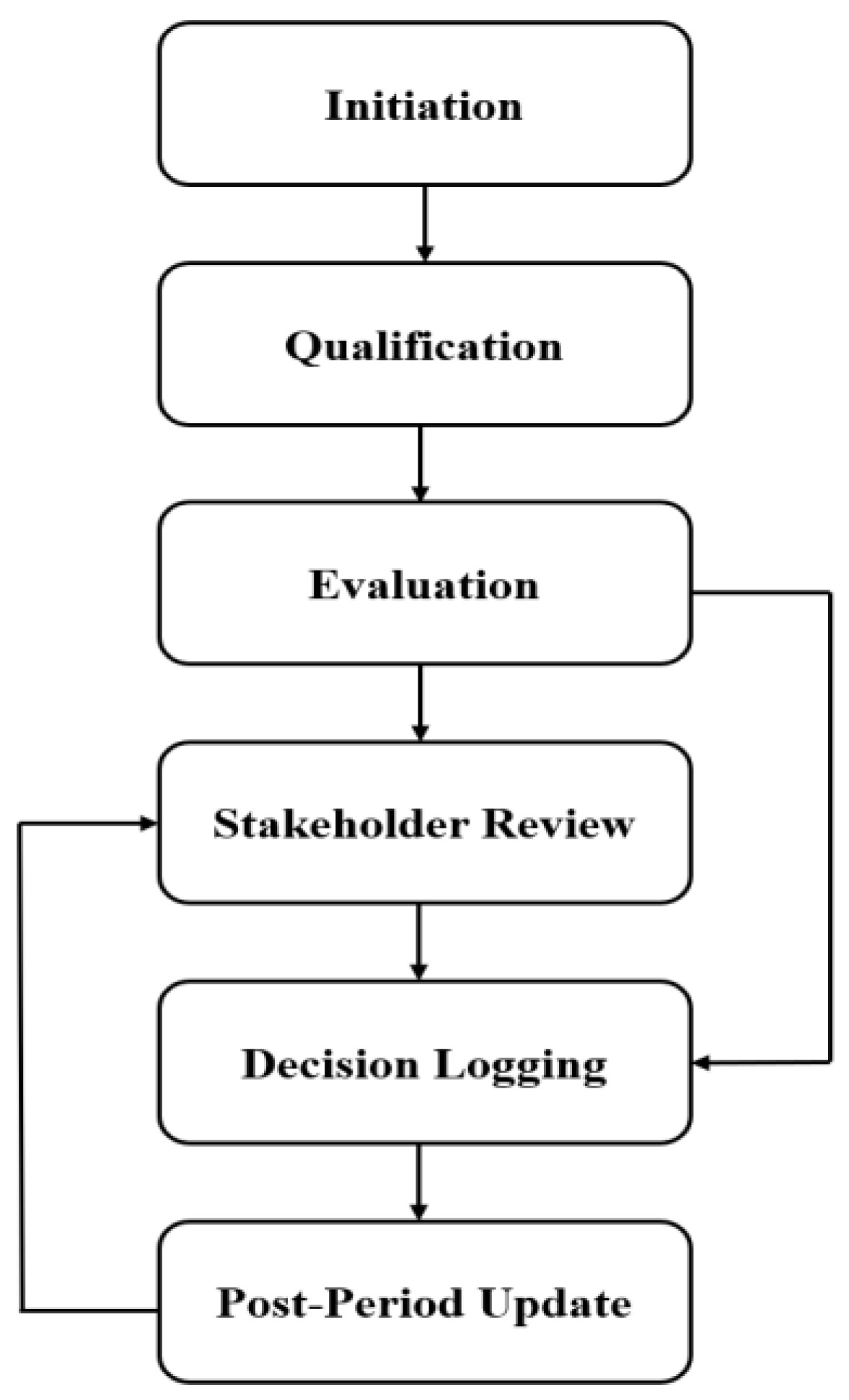

3.5. Evaluation Strategy

3.6. Summary

4. Design and Construction of the Sustainability-Aligned Business Development Framework (SABDF)

4.1. Design Objectives and Requirements

4.2. Design Principles (DP1 to DP6)

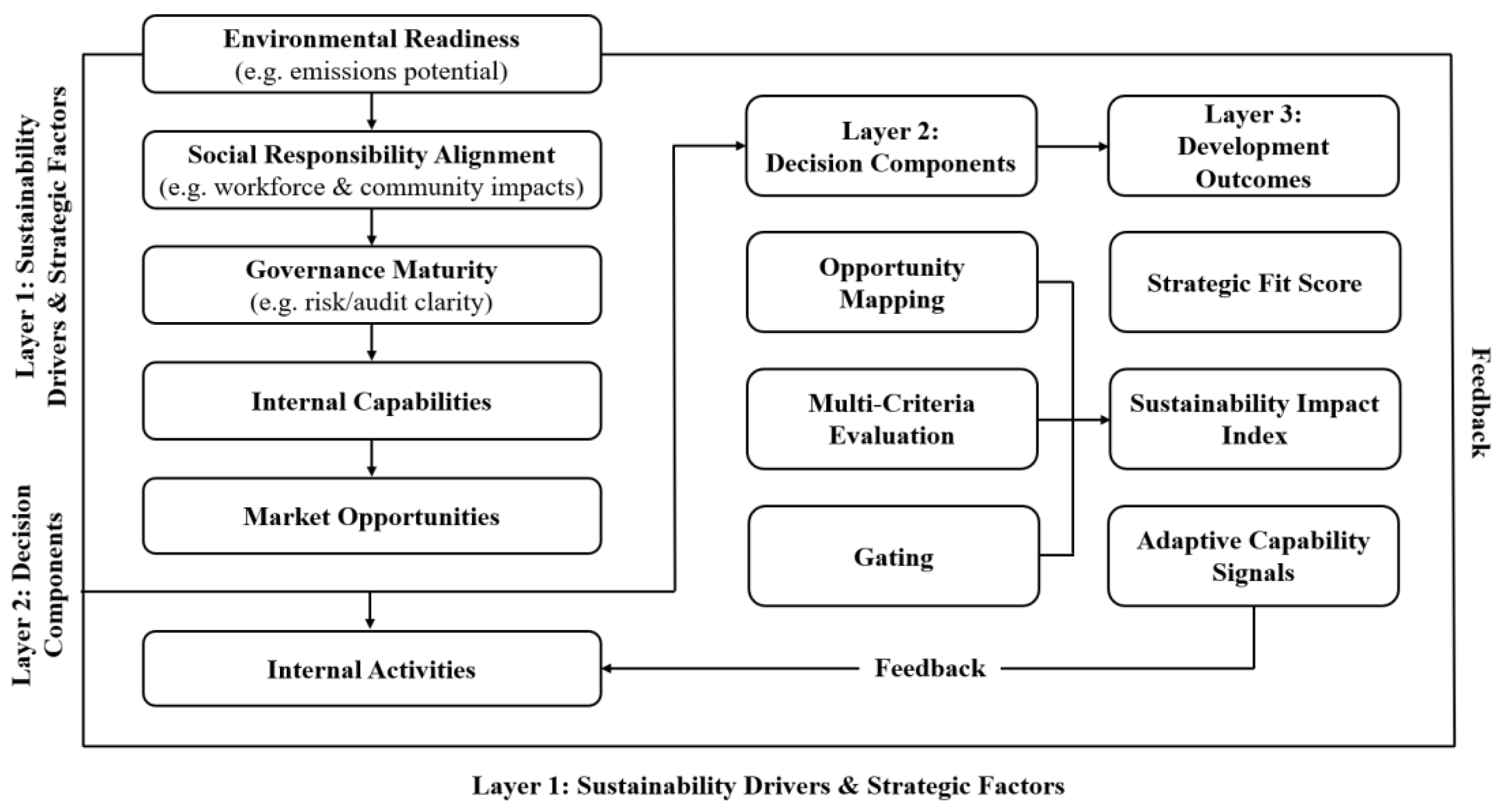

4.3. Layered Conceptual Architecture

- Layer 1: Sustainability Drivers and Strategic Factors This layer captures both external and internal signals relevant to sustainability and strategic positioning. It includes environmental readiness (e.g., emissions reduction potential, resilience contribution), social alignment (e.g., labor practices, community engagement), governance maturity (e.g., transparency, audit structures), internal capabilities, and market opportunities;

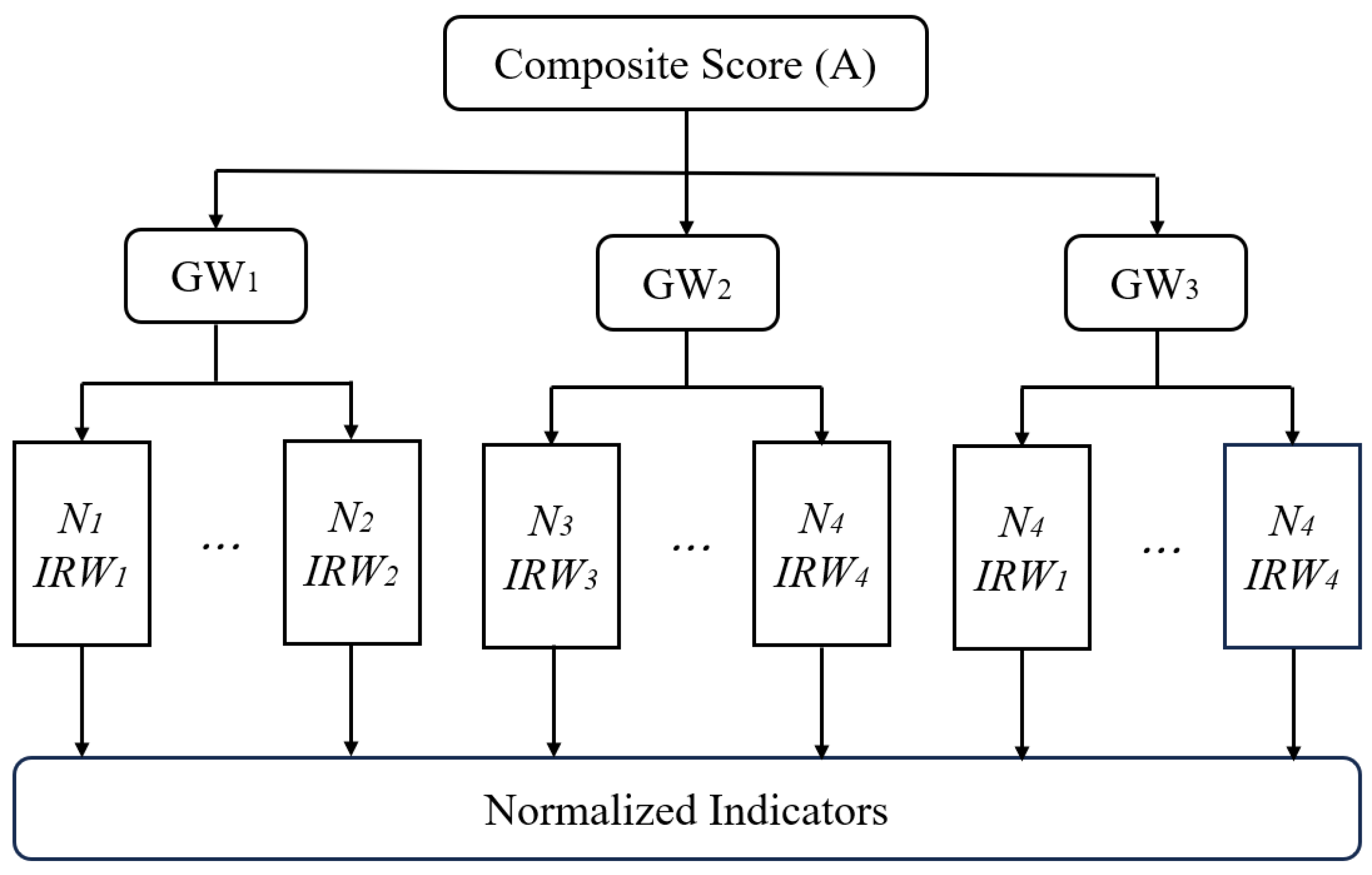

- Layer 2: Decision Components This layer operationalizes the evaluation logic through opportunity mapping, internal capability assessment, and multi-criteria analysis. The latter includes indicator normalization, hierarchical weighting (group and intra-group), composite score generation, and threshold-based gating;

- Layer 3: Development Outcomes The final outputs of the framework include a Strategic Fit Score (aggregated opportunity suitability), a Sustainability Impact Index (disaggregated ESG contribution), and Adaptive Capability Signals (e.g., ranking stability, trigger activations).

4.4. Conceptual Indicator and Scoring Design

4.5. Decision Flow and Gating Mechanism

4.6. Operational Mechanisms

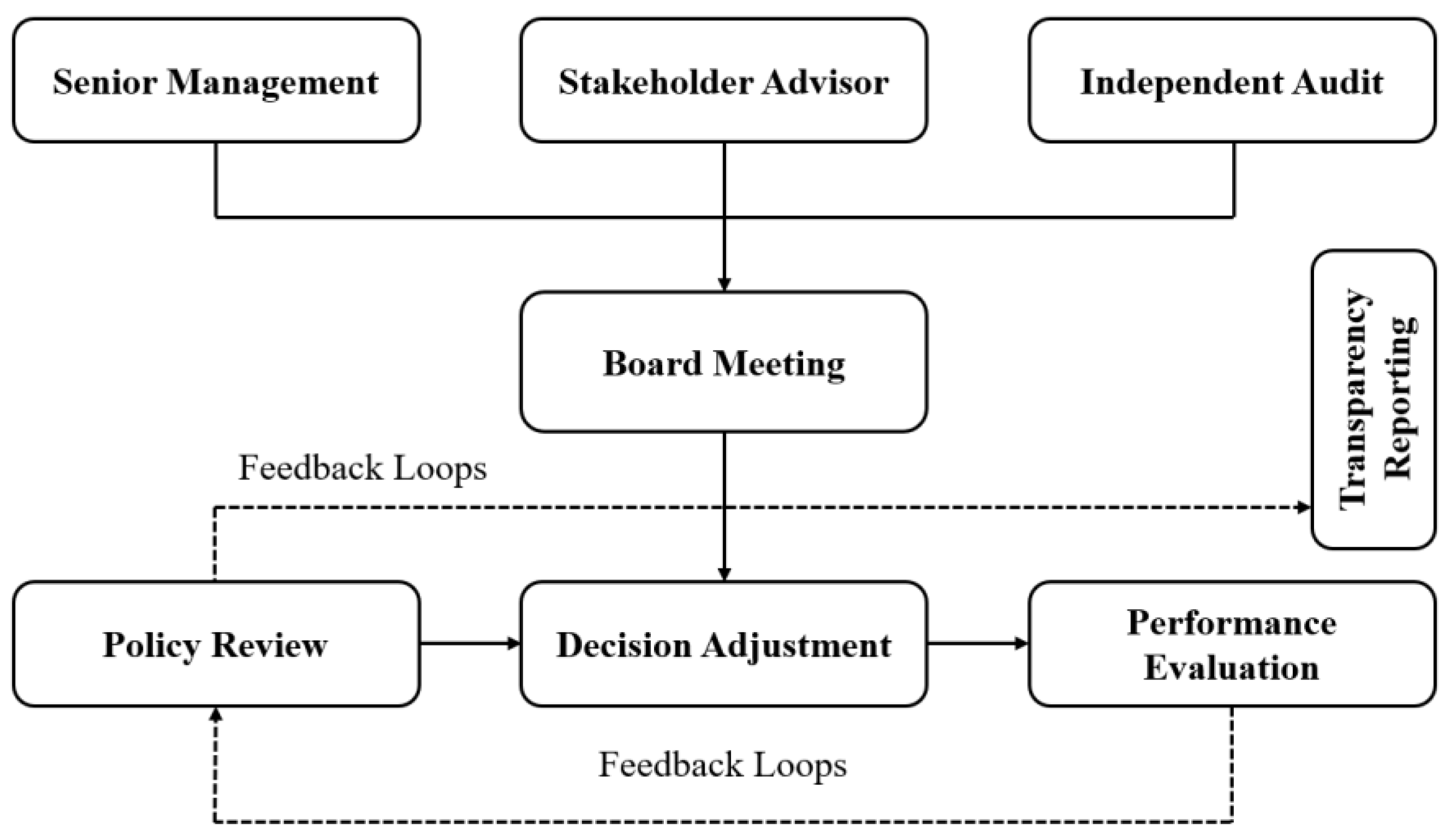

4.7. Extensibility, Governance, and Summary

5. Evaluation and Case Validation

5.1. Purpose of Evaluation

5.2. Cases and Data Sources

- Case A: An energy alliance centered on decarbonization infrastructure and grid resilience [39].

- Case B: A group of multinational manufacturing companies of innovation and efficiency initiatives [40].

- Case C: An agribusiness value chain program emphasizing soil health, water efficiency, biodiversity, and smallholder inclusion [41].

- Case A: proposals mapped N=27, with indicator coverage of 82%;

- Case B: initiatives mapped N=34, with indicator coverage of 77%;

- Case C: pilot briefs mapped N=21, with indicator coverage of 88%.

5.3. Evaluation Procedures and Metrics

5.4. Case Findings

5.5. Cross Case Synthesis and Principal Support

5.6. Validity Considerations, Refinements and Design Propositions

5.7. Limitations and Future Research Path

5.8. Summary

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| SABDF | Sustainability-Aligned Business Development Framework |

| FRE | Forecast–Realized Error |

| SDI | Sustainability Data Integration |

Appendix A: Evaluation and Coding Rubric for Design Principles (DP1–DP6)

| Design Principle | Definition / Operationalization | Evaluation Source & Criteria | Observable Evidence / Coding Levels |

| DP1 – Transparency / Goal Coherence | ESG goals align with business strategy and are traceable to data, weights, thresholds, and rationale. | Strategic planning documents, indicator registries, metadata logs, version history. | Absent: No source or version traceability. Emerging: Partial source attribution, incomplete records. Moderate: Most indicators linked to source and version info. Strong: Full coverage of indicator provenance, weight logic, audit trail. |

| DP2 – Embedded Integration / Role Alignment | ESG indicators integrated with capability and strategic metrics in a unified evaluation model. | Scoring architecture diagrams, weight matrices, cross-functional planning records. | Absent: ESG isolated from decision logic. Emerging: ESG noted in reports but excluded from evaluation model. Moderate: Partial integration with business/capability metrics. Strong: Full integration in multi-criteria model with business logic. |

| DP3 – Iterative Feedback / Temporal Integration | Existence of feedback loops and recalibration triggers across short-, medium-, and long-term horizons. | Trigger definitions (FRE, SDI), update protocols, roadmaps. | Absent: No feedback or recalibration mechanism. Emerging: Feedback logic defined but not activated. Moderate: System in place, partial pilots or trials. Strong: At least one recalibration cycle completed and documented. |

| DP4 – Modular Adaptability / Process Consistency | Ability to add or replace indicator groups without altering architecture; ESG logic consistent across stages. | Substitution logs, modularity diagrams, stability checks, strategy–review documents. | Absent: Fixed architecture, no modularity. Emerging: Adjustments require code/schema changes. Moderate: Indicators modified with minimal disruption. Strong: Plug-and-play modularity, zero structural edits. |

| DP5 – Stakeholder Inclusion | Stakeholder inputs elicited, translated into weights, consensus assessed. | Input logs, preference elicitation (e.g., AHP), Kendall’s W, reconciliation records. | Absent: No stakeholder input. Emerging: Informal or qualitative input, not quantified. Moderate: Structured methods applied. Strong: Weights validated with consensus (Kendall’s W ≥ 0.7). |

| DP6 – Score-Based Comparability / Traceability | Normalization and stability metrics ensure scores are comparable across options and time; ESG actions traceable to reasoning. | Normalization techniques, CV, Kendall’s τ, decision logs. | Absent: No normalization or comparability controls. Emerging: Basic normalization, no stability checks. Moderate: Some comparability metrics implemented. Strong: Full safeguards, CV and Kendall’s τ meet thresholds (τ ≥ 0.7). |

Appendix B: Coding Results, Examples, and Statistics

| Design Principle | Case A (Energy) |

Case B (Industrial) |

Case C (Agri) |

Overall Rating Count |

| DP1: Transparency | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | 1 Moderate, 2 Strong |

| DP2: Embedded Integration | Strong | Strong | Strong | 3 Strong |

| DP3: Iterative Feedback | Emerging | Emerging | Emerging | 3 Emerging |

| DP4: Modular Adaptability | Emerging | Strong | Strong | 1 Emerging, 2 Strong |

| DP5: Stakeholder Inclusion | Emerging | Moderate | Strong | 1 Emerging, 1 Moderate, 1 Strong |

| DP6: Score-Based Comparability | Emerging | Moderate | Strong | 1 Emerging, 1 Moderate, 1 Strong |

Appendix C: Variable Definitions and Data Sources

| Code | Variable Name | Description | Data Source Examples | Frequency | Data Type |

| D1 | Environmental Readiness | Measures environmental compliance, emissions transparency, and efficiency | ISO 14001, Scope 1/2/3 emissions reports, CDP, regulatory filings | Annual | Observed |

| D2 | Social Responsibility Alignment | Assesses stakeholder engagement, equity, and social initiatives | GRI 413, DEI policies, sustainability reports, HR records | Quarterly to Annual | Estimated |

| D3 | Governance Maturity | Assesses governance oversight and ESG capabilities | Corporate governance committee records, SASB scores | Annual | Observed |

| P1 | Market Opportunity Mapping | Identifies ESG-aligned strategic growth opportunities | Regulatory incentives, industry forecasts, policy briefings | Project-based | Simulated |

| P2 | Internal Capability Assessment | Evaluates organizational readiness to execute ESG strategies | Internal KPIs, ESG training logs, budget records | Semi-Annual | Observed |

| P3 | Multi-Criteria Evaluation | Applies structured tools to balance ESG and business viability | Weighted scoring matrices, stakeholder workshops | Project-based | Simulated |

| O1 | Strategic Fit Score | Alignment between ESG factors and strategic initiatives | Composite score from P1-P3 evaluation | Per decision cycle | Simulated |

| O2 | Sustainability Impact Projection | Forecasts ESG impact of initiatives | Derived from environmental, social, governance indicators | Per decision cycle | Estimated |

| O3 | Outcome Realization Tracking | Captures realized ESG outcomes to validate forecast accuracy and adaptive learning. | Post-implementation reports, sustainability audits, stakeholder feedback records | Post-deployment | Observed |

Appendix D: Evaluation Criteria and Case Evidence Matrix

| Case Study | Evaluation Dimension | Indicator | Type of Evidence | Rating or Outcome | Notes |

| Smart Power Alliance A |

D1 – Environmental Readiness | Renewable integration compliance | National policy, project data | High | Enabled by Germany’s energy transition policy |

| O1 – Strategic Fit Score | Alignment of ESG and business | Project portfolio and criteria | 4.5 / 5 | Strong co-design and policy alignment | |

| O2 – Sustainability Impact | CO2e reduction, grid optimization | Audit reports, KPIs | Strong | Reported metrics show measurable impact | |

| Multinational manufacturing companies B |

D3 – Governance Maturity | ESG oversight structure | Internal decision tools | Moderate to High | Documented procedures and reporting cycles |

| O3 – Adaptive Capability | ESG embedded in product design | R&D integration evidence | Medium | Gradual institutionalization of ESG criteria | |

| Agribusiness Firm C |

D2 – Social Responsibility | Labor standards, fair trade | Sustainability audits | High | Certified supply chain and fair labor policies |

| P1 – Market Opportunity | Organic and traceable demand | Market data, customer research | High | ESG-aligned product expansion |

References

- Pörtner, H.O.; Scholes, R.J.; Arneth, A.; Barnes, D.K.A.; Burrows, M.T.; Diamond, S.E.; Val, A.L. Overcoming the Coupled Climate and Biodiversity Crises and Their Societal Impacts. Science 2023, 380, eabl4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, S. Global Sustainability: Trends, Challenges, and Case Studies. In Global Sustainability: Trends, Challenges & Case Studies. In Global Sustainability: Trends, Challenges & Case Studies; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyoob, A.; Sajeev, A. Navigating Sustainability: Assessing the Imperative of ESG Considerations in Achieving SDGs. In ESG Frameworks for Sustainable Business Practices; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, K. Balancing Corporate Social Responsibility, Environmental Policies, and Stakeholder Expectations for Sustainable Development: A Stakeholder-Centric Analysis. Sustain. Dev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Mohapatra, A.K.; Albishri, N.; Liguori, R.; Stilo, P. A Knowledge Management Perspective on ESG 2.0 and Policy Implications toward Corporate Sustainability. J. Knowl. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivinen, S.; Integrating Innovations into a Company’s Strategy through a Concept of Sustainable Futures Business Design. Theseus 2023. Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/801002 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Morris, J.; Sassen, R.; McGuinness, M. Beyond Water Scarcity and Efficiency? Water Sustainability Disclosures in Corporate Reporting. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 14, 490–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Pan, H.; Feng, Y.; Du, S. How Do ESG Practices Create Value for Businesses? Research Review and Prospects. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 15, 1155–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin-Behravesh, S.A.; Gomez-Trujillo, A.M.; Perdomo-Charry, G.; Djunaedi, M.K.D.; Ong, A.K.S. Sustainability Strategies and Corporate Legitimacy: Analyzing Firm Performance through Green Innovation and Technological Turbulence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.M.; Van, H.V.; Vo, D.T.T.; Nguyen, O.K.T.; Bui, D.V. ESG Practices and Firm Value: A Novel Perspective from Mediating and Moderating Components. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shatila, K.; Martínez-Climent, C.; Enri-Peiró, S. The Mediating Roles of Corporate Reputation, Employee Engagement, and Innovation in the CSR—Performance Relationship: Insights from the Middle Eastern Banking Sector. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Xue, H.; Yang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Fan, B. Green Credit Policy and Corporate Green Innovation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 99, 104031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat, N.C.; Mandouri, J.; Kucukvar, M.; Kutty, A.A.; Al-Muftah, A.A. Driving Sustainable Business Practices with Carbon Accounting and Reporting: A Holistic Framework and Empirical Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 2795–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusif, S.; Hafeez-Baig, A. Impact of Stakeholder Engagement Strategies on Managerial Cognitive Decision-Making: The Context of CSP and CSR. Soc. Responsib. J. 2024, 20, 1101–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Quigley, N.R. Responsible Leadership and Stakeholder Management: Influence Pathways and Organizational Outcomes. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraojimba, C.; Okogwu, C.; Egbokhaebho, B.A.; Raji, A.; Kolade, A.O.; Olalere, B.I. Cross-Industry Insights: A Comprehensive Review of Effective Stakeholder Management Benefits. Mater. Corros. Eng. Manag. 2023, 4, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minatogawa, V.; Franco, M.; Rampasso, I.S.; Holgado, M.; Garrido, D.; Pinto, H.; Quadros, R. Towards Systematic Sustainable Business Model Innovation: What Can We Learn from Business Model Innovation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Phan, P.Y.; Krishnan, S.N.; Agarwal, R.; Sohal, A. Industry 4.0-Driven Business Model Innovation for Supply Chain Sustainability: An Exploratory Case Study. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Mishra, R.; He, Q. Sustainable Supply Chain and Environmental Collaboration in the Supply Chain Management: Agenda for Future Research and Implications. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M.S. Corporate Sustainability Reimagined: A Bibliometric–Systematic Literature Review of Governance, Technology, and Stakeholder-Driven Strategies for SDG Impact. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmidt, J.; Burtscher, J.; Gast, J.; Kraus, S.; Puumalainen, K. Navigating the Twin Transformation: How Digitalization and Sustainability Shape the Future. Strateg. Change 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarelli, M.; Cosimato, S.; Landi, G.; Iandolo, F. Socially Responsible Investment Strategies for the Transition towards Sustainable Development: The Importance of Integrating and Communicating ESG. TQM J. 2021, 33, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldowaish, A.; Kokuryo, J.; Almazyad, O.; Goi, H.C. Environmental, Social, and Governance Integration into the Business Model: Literature Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feilhauer, S.; Hahn, R. Formalization of Firms’ Evaluation Processes in Cross-Sector Partnerships for Sustainability. Bus. Soc. 2021, 60, 684–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo-Lahti, M.; Haapio, H. Possibility-Driven Design and Responsible Use of AI for Sustainability. In Design(s) for Law; Ledizioni: Milan, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Almnadheh, Y.; Samara, H.; AlQudah, M.Z. Enhancing ESG Integration in Corporate Strategy: A Bibliometric Study and Content Analysis. Int. J. Law Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevner, N.; March, N.; Park, N.; Ram, N. Design Science in Information Systems Research. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, S.; Hevner, A.R. Positioning and Presenting Design Science Research for Maximum Impact. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuan, N.H.; Antunes, P. Positioning Design Science as an Educational Tool for Innovation and Problem Solving. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2022, 51, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuunanen, T.; Winter, R.; vom Brocke, J. Dealing with Complexity in Design Science Research: A Methodology Using Design Echelons. MIS Q. 2024, 48, 427–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.S. Strategic Sustainability: ESG Integration in Contemporary Business. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Sci. 2024, 7, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavurova, B.; Polishchuk, I.; Polishchuk, V. Multi-Criteria Hybrid Model of Region Assessment in the Context of Sustainable Tourism. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2025, 26, 880–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weda, I. Autonomous Maritime Logistics in the Age of Sustainable Digital Transformation: An Integrative Framework for Smart and Green Shipping. Int. J. Entrep. Bus. Dev. 2025, 8, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırmızı, M.; Kocaoglu, B. Digital Transformation Maturity Model Development Framework Based on Design Science: Case Studies in Manufacturing Industry. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 33, 1319–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksel, J.; Bakshi, B.R. Designing for Resilience and Sustainability: An Integrated Systems Approach. In Engineering and Ecosystems: Seeking Synergies toward a Nature-Positive World; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 469–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataleblu, A.A.; Rauch, E.; Cochran, D.S. Resilient Sustainability Assessment Framework from a Transdisciplinary System-of-Systems Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, R.Y.C. Transforming ESG Analytics with Machine Learning: A Systematic Literature Review Using TCCM Framework. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Malla, D.; El-Gayar, O. Framework for Benchmarking Machine Learning Models: Integrating Performance Metrics, Explainability Techniques, and Robustness Assessments. In Proceedings of the Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS 2025), SIG-DSA Data Science, Data Science Applications, Austin, TX, USA; 2025; p. 7. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2025/data_science/sig_dsa/7 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zioło, M.; Bąk, I.; Spoz, A. Incorporating ESG Risk in Companies’ Business Models: State of Research and Energy Sector Case Studies. Energies 2023, 16, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayaka, I.I.K.; Bandara, M.N.G.K. Strategic Integration of Sustainable Development Goals in Manufacturing Multinational Enterprises in Sweden: A Qualitative Case Study on Swedish Multinational Enterprises. Unpublished Manuscript, (accessed on 30 August 2025)5624. [Google Scholar]

- Sadovska, V. Change for Sustainable Agricultural Business. Addressing Business Model Transformation and Sustainable Value Creation. Acta Univ. Agric. Sueciae 2023, 27, 1–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating Sustainable Value. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocmanová, A.; Šimberová, I. Determination of Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance Indicators: Framework in the Measurement of Sustainable Performance. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2014, 15, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annesi, N.; Battaglia, M.; Ceglia, I.; Mercuri, F. Navigating Paradoxes: Building a Sustainable Strategy for an Integrated ESG Corporate Governance. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 531–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashitew, A.A. Corporate Uptake of the Sustainable Development Goals: Mere Greenwashing or an Advent of Institutional Change? J. Int. Bus. Policy 2021, 4, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Khatib, S.F.; Lee, Y. The Power and Paradox of ESG: Unlocking New Quality Productivity for Sustainable Innovation. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugaard, D.; Ding, A. Global Drivers for ESG Performance: The Body of Knowledge. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Thapa, D. Clarifying the Business Model Construct: A Theory-Driven Integrative Literature Review through Ecosystems and Open Systems Perspectives. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.C.; Carvalho, T.C.M.D.B. Maturity Models and Sustainable Indicators—A New Relationship. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guandalini, I. Sustainability through Digital Transformation: A Systematic Literature Review for Research Guidance. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasrotia, S.S.; Rai, S.S.; Rai, S.; Giri, S. Stage-Wise Green Supply Chain Management and Environmental Performance: Impact of Blockchain Technology. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2024, 4, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peças, P.; John, L.; Ribeiro, I.; Baptista, A.J.; Pinto, S.M.; Dias, R.; Cunha, F. Holistic Framework to Data-Driven Sustainability Assessment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doni, F.; Fiameni, M. Can Innovation Affect the Relationship between Environmental, Social, and Governance Issues and Financial Performance? Empirical Evidence from the STOXX200 Index. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 546–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayar, D. A Design-Oriented Framework on Theory Development around Emerging Phenomena. J. Eng. Des. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffay, M.; Bocken, N. Sustainable by Design: An Organizational Design Tool for Sustainable Business Model Innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 427, 139294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimov, D.; Maula, M.; Romme, A.G.L. Crafting and Assessing Design Science Research for Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2023, 47, 1543–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender-Salazar, R. Design Thinking as an Effective Method for Problem-Setting and Needfinding for Entrepreneurial Teams Addressing Wicked Problems. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magas, M.; Kiritsis, D. Industry Commons: An Ecosystem Approach to Horizontal Enablers for Sustainable Cross-Domain Industrial Innovation (A Positioning Paper). Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, J.; Ketokivi, M.; Hameri, A.P. Bridging Practice and Theory: A Design Science Approach. Decis. Sci. 2009, 40, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A. The Business Model Ontology: A Proposition in a Design Science Approach; Doctoral Dissertation, Université de Lausanne, Faculté des Hautes Études Commerciales, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- De Sordi, J.O. Design Science Research Methodology: Theory Development from Artifacts; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, C.; Ahmed, T.; Khashru, M.A.; Ahmed, R.; Ratten, V.; Jayaratne, M. The Complexity of Stakeholder Pressures and Their Influence on Social and Environmental Responsibilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 358, 132038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furr, N.R.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Strategy and Uncertainty: Resource-Based View, Strategy-Creation View, and the Hybrid between Them. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1915–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier, E.; Knight, G.; Luo, Y.; Delios, A. Corporate Social Performance in International Business. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2022, 54, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R. An Organizational Capacity for Trustworthiness: A Dynamic Routines Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 188, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raha, A.; Kazemi, S.H. How to Have the Best of Both Worlds: Value-Based Decision-Making through Stakeholder Value Trade-Offs. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2025, 34, 1432–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilakopoulou, P.; Hustad, E. Bridging Digital Divides: A Literature Review and Research Agenda for Information Systems Research. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagals, M. Expanding Data Governance across Company Boundaries—An Inter-Organizational Perspective of Roles and Responsibilities. In Proceedings of the IFIP Working Conference on the Practice of Enterprise Modeling, Cham, Switzerland, November 2021; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodendorf, F.; Bayr, C. Shaping Platform Governance Principles to Manage Interorganizational Data Exchange. Inf. Syst. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.W.; Beath, C.M.; Mocker, M. Designed for Digital: How to Architect Your Business for Sustained Success; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Benbya, H.; Nan, N.; Tanriverdi, H.; Yoo, Y. Complexity and Information Systems Research in the Emerging Digital World. MIS Q. 2020, 44, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsunova, A.; Goodman, J.C.; Halme, M. Activities and Roles of Stakeholders in Sustainability-Oriented Innovation of Firms. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, ; No, 2016; 1; Volume 2016, p. 15594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiatma, T. Integrating Sustainability into Strategic Management. In Proceedings of the 12th Gadjah Mada International Conference on Economics and Business (GAMAICEB 2024), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, May 2025; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 319, p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal, S.; Jovanovic, P.; Bilalli, B.; Romero, O. Operationalizing and Automating Data Governance. J. Big Data 2022, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadström, P. Aligning Corporate and Business Strategy: Managing the Balance. J. Bus. Strategy 2019, 40, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pixton, P.; Nickolaisen, N.; Little, T.; McDonald, K.J. Stand Back and Deliver: Accelerating Business Transformation; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Theoretical Source | Core Concept | Design Translation | Framework Component |

| Stakeholder Theory | Balancing multiple interests and expectations | Supports decision rules for stakeholder alignment | Governance input |

| Resource-Based View | Dynamic capabilities and resource reconfiguration | Shapes drivers linked to strategy flexibility and resilience | Sustainability drivers |

| ESG Integration Literature | Quantitative indicators, reporting consistency, strategic linkage | Enables scoring templates, operational metrics, and process structure | Scoring logic and evaluation components |

| Design Principle (DP) | Description | Addresses Requirement(s) |

| DP1: Transparency | Version control, metadata, audit trail for indicators, thresholds, weights. | R1, R5 |

| DP2: Embedded Integration | ESG logic embedded with strategic and operational metrics. | R1, R2 |

| DP3: Iterative Feedback | Variance triggers initiate recalibration; adaptive design. | R3, R5 |

| DP4: Modular Adaptability | Cluster-level modularity and substitution without redesign. | R2, R3 |

| DP5: Stakeholder Inclusion | Weight generation from participatory processes with consensus metrics. | R4 |

| DP6: Score-Based Comparability | Normalization, dispersion, and time-series comparability safeguards. | R5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).