Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

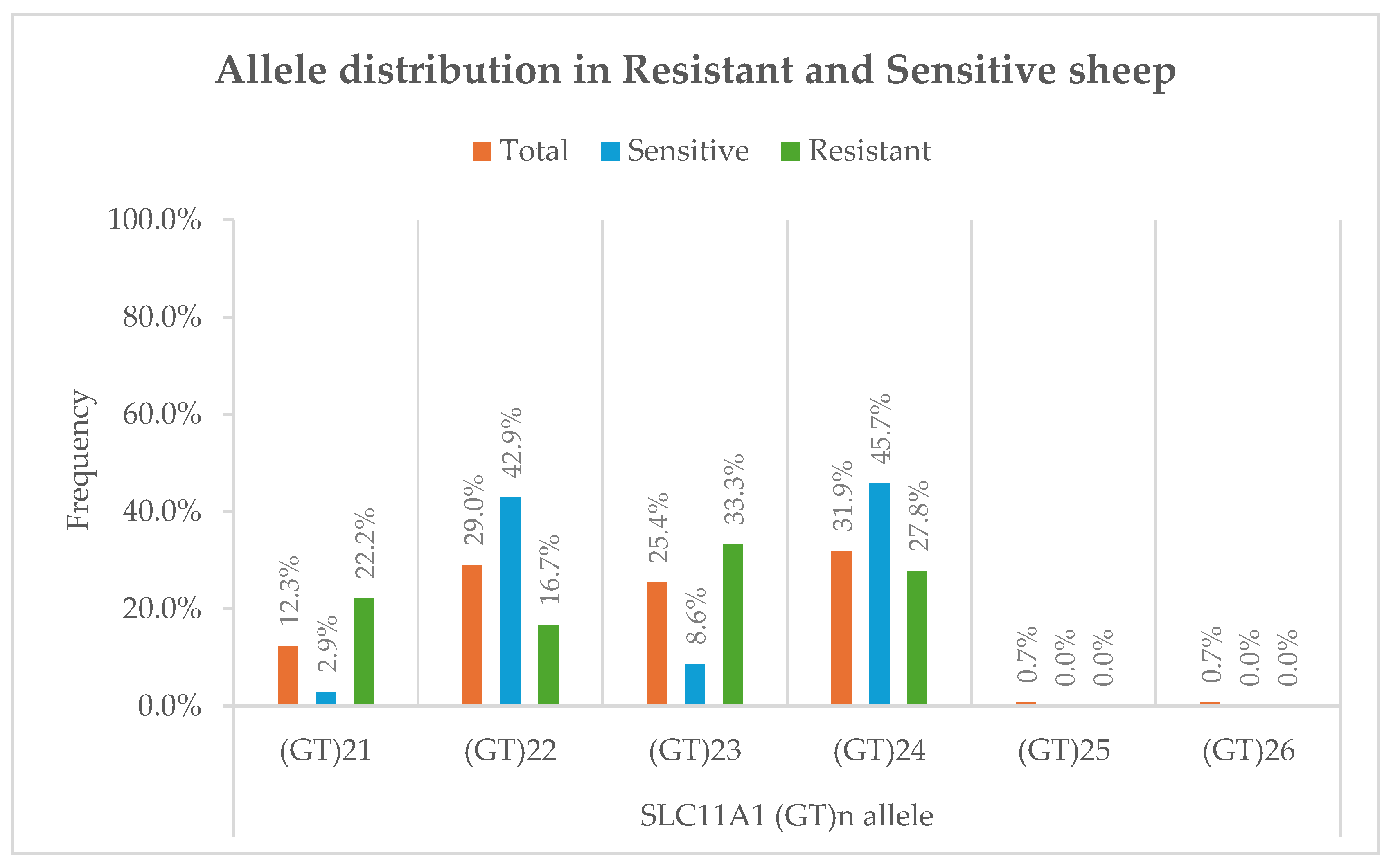

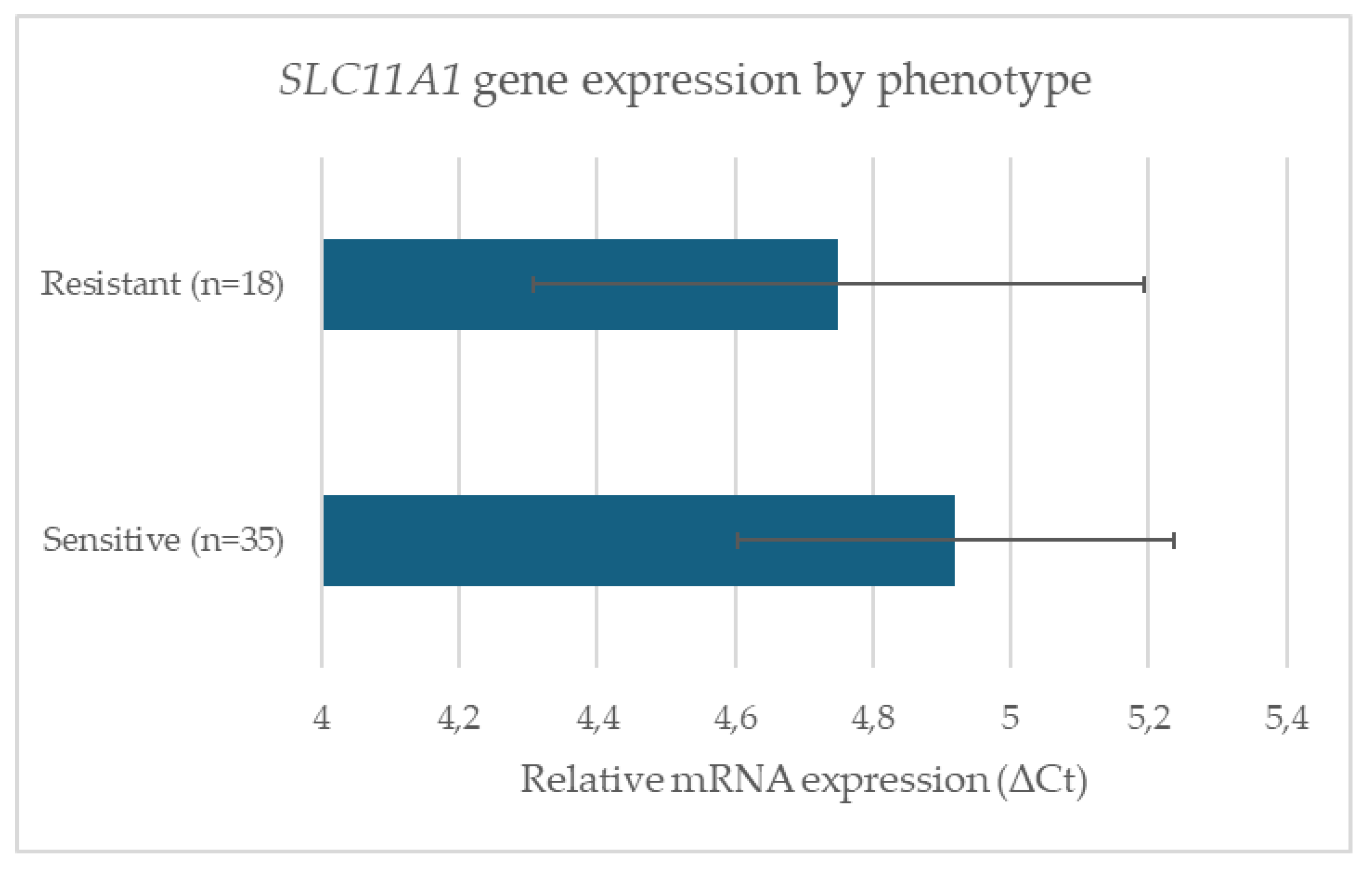

Paratuberculosis (Johne’s disease), caused by Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP), is a chronic enteric infection that significantly impacts small ruminant health and productivity. Genetic variation in host immune genes, particularly SLC11A1, has been implicated in resistance to intracellular pathogens. The aim of this study was to investigate whether polymorphisms in the 3′UTR (GT)n microsatellite of SLC11A1 are associated with resistance or susceptibility to paratuberculosis in sheep, complementing existing SNP-based genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in cattle and goats. A total of 138 animals were genotyped, and a subset of 53 was analyzed for SLC11A1 expression. Six alleles were identified, with (GT)21 and (GT)23 significantly enriched in resistant sheep (p < 0.05), while (GT)22 and (GT)24 were more common in sensitive animals. Overall allele distribution showed a significant genotype–phenotype association (χ2 = 12.4, p = 0.006, Cramér’s V = 0.38). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in basal SLC11A1 mRNA expression between groups or across genotypes. Our findings extend previous GWAS results in sheep by providing preliminary allele-level resolution of a functional microsatellite locus. Identification of resistance-associated alleles provides a foundation for genetic selection strategies that complement vaccination and management, supporting sustainable control of paratuberculosis in sheep.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population and sample collection

2.2. DNA and RNA isolation

2.3. Sequence analysis of the ovine SLC11A1 gene

2.4. Gene expression analysis

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1.(. GT)n repeat polymorphism frequencies

3.2. Genotype–Phenotype association

3.3. SLC11A1 gene expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harris, N. B., & Barletta, R. G. (2001). Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in Veterinary Medicine. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 14(3), 489–512.

- Clarke, C. J. (1997). The pathology and pathogenesis of paratuberculosis in ruminants and other species. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 116(3), 217–261. [CrossRef]

- Bush, R. D., Windsor, P. A., & Toribio, J. A. L. M. L. (2006). Losses of adult sheep due to ovine Johne’s disease in 12 infected flocks over a 3-year period. Australian Veterinary Journal, 84(7), 246–253. [CrossRef]

- Hasonova, L., & Pavlik, I. (2006). Economic impact of paratuberculosis in dairy cattle herds: A review. Veterinarni Medicina, 51(5), 193–211. [CrossRef]

- Raizman, E. A., Fetrow, J., Wells, S. J., Godden, S. M., Oakes, M. J., & Vazquez, G. (2007). The association between Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis fecal shedding or clinical Johne’s disease and lactation performance on two Minnesota, USA dairy farms. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 78(3–4), 179–195. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S. S., & Toft, N. (2009). A review of prevalences of paratuberculosis in farmed animals in Europe. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 88(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- di Marco Lo Presti, V., Ippolito, D., Migliore, S., Tolone, M., Mignacca, S. A., Marino, A. M. F., Amato, B., Calogero, R., Vitale, M., Vicari, D., Ciarello, F. P., & Fiasconaro, M. (2024). Large-scale serological survey on Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection in sheep and goat herds in Sicily, Southern Italy. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 11, 1334036. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, M., Ridler, A., Wilson, P. R., & Heuer, C. (2018). Control of clinical paratuberculosis in New Zealand pastoral livestock. New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 66(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Windsor, P., & Whittington, R. (2020). Ovine Paratuberculosis Control in Australia Revisited. Animals : An Open Access Journal from MDPI, 10(9), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, R. J., Maattanen, P., Daigle, J., Potter, A., Griebel, P., & Napper, S. (2014). From mouth to macrophage: Mechanisms of innate immune subversion by Mycobacterium avium subsp. Paratuberculosis. Veterinary Research, 45(1). [CrossRef]

- Whittington, R. J., Begg, D. J., de Silva, K., Plain, K. M., & Purdie, A. C. (2012). Comparative immunological and microbiological aspects of paratuberculosis as a model mycobacterial infection. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 148(1–2), 29–47. [CrossRef]

- González, J., Geijo, M. v., García-Pariente, C., Verna, A., Corpa, J. M., Reyes, L. E., Ferreras, M. C., Juste, R. A., García Marín, J. F., & Pérez, V. (2005). Histopathological classification of lesions associated with natural paratuberculosis infection in cattle. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 133(2–3), 184–196. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. L., West, D. M., Wilson, P. R., de Lisle, G. W., Collett, M. G., Heuer, C., & Chambers, J. P. (2013). The prevalence of disseminated Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection in tissues of healthy ewes from a New Zealand farm with Johne’s disease present. New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 61(1), 41–44. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D. J., Vaughan, J. A., Stiles, P. L., Noske, P. J., Tizard, M. L. V., Prowse, S. J., Michalski, W. P., Butler, K. L., & Jones, S. L. (2004). A long-term study in Merino sheep experimentally infected with Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis: Clinical disease, faecal culture and immunological studies. Veterinary Microbiology, 104(3–4), 165–178. [CrossRef]

- Begg, D. J., & Whittington, R. J. (2008). Experimental animal infection models for Johne’s disease, an infectious enteropathy caused by Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Veterinary Journal, 176(2), 129–145. [CrossRef]

- Begg, D. J., & Griffin, J. F. T. (2005). Vaccination of sheep against M. paratuberculosis: Immune parameters and protective efficacy. Vaccine, 23(42), 4999–5008. [CrossRef]

- Gwozdz, J. M., Thompson, K. G., Manktelow, B. W., Murray, A., & West, D. M. (2000). Vaccination against paratuberculosis of lambs already infected experimentally with Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. Australian Veterinary Journal, 78(8), 560–566. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. v., Singh, P. K., Singh, A. v., Sohal, J. S., Gupta, V. K., & Vihan, V. S. (2007). Comparative efficacy of an indigenous “inactivated vaccine” using highly pathogenic field strain of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis “Bison type” with a commercial vaccine for the control of Capri-paratuberculosis in India. Vaccine, 25(41), 7102–7110. [CrossRef]

- Dhand, N. K., Johnson, W. O., Eppleston, J., Whittington, R. J., & Windsor, P. A. (2013). Comparison of pre- and post-vaccination ovine Johne’s disease prevalence using a Bayesian approach. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 111(1–2), 81–91. [CrossRef]

- Koets, A. P., Adugna, G., Janss, L. L. G., van Weering, H. J., Kalis, C. H. J., Wentink, G. H., Rutten, V. P. M. G., & Schukken, Y. H. (2000). Genetic variation of susceptibility to Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection in dairy cattle. Journal of Dairy Science, 83(11), 2702–2708. [CrossRef]

- Reddacliff, L. A., Beh, K., McGregor, H., & Whittington, R. J. (2005). A preliminary study of possible genetic influences on the susceptibility of sheep to Johne’s disease. Australian Veterinary Journal, 83(7), 435–441. [CrossRef]

- Lugton, I. W. (2004). Cross-sectional study of risk factors for the clinical expression of ovine Johne’s disease on New South Wales farms. Australian Veterinary Journal, 82(6), 355–365. [CrossRef]

- Bermingham, M. L., Bishop, S. C., Woolliams, J. A., Pong-Wong, R., Allen, A. R., McBride, S. H., Ryder, J. J., Wright, D. M., Skuce, R. A., McDowell, S. W., & Glass, E. J. (2014). Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci associated with resistance to bovine tuberculosis. Heredity, 112(5), 543–551. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Jiang, J., Yang, S., Cao, J., Han, B., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Yu, Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, Q., Fang, L., Cantrell, B., & Sun, D. (2018). Genome-wide association study of Mycobacterium avium subspecies Paratuberculosis infection in Chinese Holstein. BMC Genomics, 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Canive, M., González-Recio, O., Fernández, A., Vázquez, P., Badia-Bringué, G., Lavín, J. L., Garrido, J. M., Juste, R. A., & Alonso-Hearn, M. (2021). Identification of loci associated with susceptibility to Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection in Holstein cattle using combinations of diagnostic tests and imputed whole-genome sequence data. PLoS ONE, 16(8 August). [CrossRef]

- Canive, M., Badia-Bringué, G., Vázquez, P., Garrido, J. M., Juste, R. A., Fernandez, A., González-Recio, O., & Alonso-Hearn, M. (2022). A Genome-Wide Association Study for Tolerance to Paratuberculosis Identifies Candidate Genes Involved in DNA Packaging, DNA Damage Repair, Innate Immunity, and Pathogen Persistence. Frontiers in Immunology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Hearn, M., Badia-Bringué, G., & Canive, M. (2022). Genome-wide association studies for the identification of cattle susceptible and resilient to paratuberculosis. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 9, 935133. [CrossRef]

- Usai, M. G., Casu, S., Sechi, T., Salaris, S. L., Miari, S., Mulas, G., Cancedda, M. G., Ligios, C., & Carta, A. (2024). Advances in understanding the genetic architecture of antibody response to paratuberculosis in sheep by heritability estimate and LDLA mapping analyses and investigation of candidate regions using sequence-based data. Genetics Selection Evolution, 56(1). [CrossRef]

- Moioli, B., D’Andrea, S., de Grossi, L., Sezzi, E., de Sanctis, B., Catillo, G., Steri, R., Valentini, A., & Pilla, F. (2015). Genomic scan for identifying candidate genes for paratuberculosis resistance in sheep. Animal Production Science, 56(7), 1046–1055. [CrossRef]

- Iacoboni, P. A., Hasenauer, F. C., Caffaro, M. E., Gaido, A., Rossetto, C., Neumann, R. D., Salatin, A., Bertoni, E., Poli, M. A., & Rossetti, C. A. (2014). Polymorphisms at the 3′ untranslated region of SLC11A1 gene are associated with protection to Brucella infection in goats. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 160(3–4), 230–234. [CrossRef]

- Suwannawong, N., Thumarat, U., & Phongphanich, P. (2022). Association of natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 polymorphisms with Salmonella fecal shedding and hematological traits in pigs. Veterinary World, 15(11), 2738–2743. [CrossRef]

- Allen, A. R., Minozzi, G., Glass, E. J., Skuce, R. A., McDowell, S. W. J., Woolliams, J. A., & Bishop, S. C. (2010). Bovine tuberculosis: The genetic basis of host susceptibility. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1695), 2737–2745. [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, J. M., & Searle, S. (1999). Genetic regulation of macrophage activation: Understanding the function of Nramp1 (=Ity/Lsh/Bcg). Immunology Letters, 65(1–2), 73–80. [CrossRef]

- Buschman, E., Vidal, S., & Skamene, E. (1997). Nonspecific resistance to Mycobacteria: the role of the Nramp1 gene. Behring Institute Mitteilungen, 99, 51–57.

- Vidal, S., Gros, P., & Skamene, E. (1995). Natural resistance to infection with intracellular parasites: Molecular genetics identifies Nramp1 as the Bcg/Ity/Lsh locus. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 58(4), 382–390. [CrossRef]

- Wyllie, S., Seu, P., & Goss, J. A. (2002). The natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 Slc11a1 (formerly Nramp1) and iron metabolism in macrophages. Microbes and Infection, 4(3), 351–359. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N., & Joseph, S. (2012). Role of SLC11A1 gene in disease resistance. Biotechnology in Animal Husbandry, 28(1), 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Awomoyi, A. A., Marchant, A., Howson, J. M. M., McAdam, K. P. W. J., Blackwell, J. M., & Newport, M. J. (2002). Interleukin-10, polymorphism in SLC11A1 (formerly NRAMP1), and susceptibility to tuberculosis. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 186(12), 1808–1814. [CrossRef]

- Meilang, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Zhao, Y., Tian, C., Huang, J., & Fan, H. (2012). Polymorphisms in the SLC11A1 gene and tuberculosis risk: A meta-analysis update. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 16(4), 437–446. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X., Zhang, X., Yang, Y., Ding, Y., Xue, W., Meng, Y., Zhu, W., & Yin, Z. (2014). Polymorphism, Expression of Natural Resistance-associated Macrophage Protein 1 Encoding Gene (NRAMP1) and Its Association with Immune Traits in Pigs. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 27(8), 1189–1195. [CrossRef]

- Taka, S., Gazouli, M., Sotirakoglou, K., Liandris, E., Andreadou, M., Triantaphyllopoulos, K., & Ikonomopoulos, J. (2015). Functional analysis of 3’UTR polymorphisms in the caprine SLC11A1 gene and its association with the Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 167(1–2), 75–79. [CrossRef]

- Taka, S., Liandris, E., Gazouli, M., Sotirakoglou, K., Theodoropoulos, G., Bountouri, M., Andreadou, M., & Ikonomopoulos, J. (2013). In vitro expression of the SLC11A1 gene in goat monocyte-derived macrophages challenged with Mycobacterium avium subsp paratuberculosis. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 17, 8–15. [CrossRef]

- Korou, L. M., Liandris, E., Gazouli, M., & Ikonomopoulos, J. (2010). Investigation of the association of the SLC11A1 gene with resistance/sensitivity of goats (Capra hircus) to paratuberculosis. Veterinary Microbiology, 144(3–4), 353–358. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A., Naicy, T., Raghavan, K. C., Siju, J., & Aravindakshan, T. (2017). Evaluation of the association of SLC11A1 gene polymorphism with incidence of paratuberculosis in goats. Journal of Genetics, 96(4), 641–646. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, S., Kumar, S., Sharma, A., & Mitra, A. (2013). Microsatellite (GT)n polymorphism at 3′UTR of SLC11A1 influences the expression of brucella LPS induced MCP1 mRNA in buffalo peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 152(3–4), 295–302. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Larrañaga, O., Garrido, J. M., Manzano, C., Iriondo, M., Molina, E., Gil, A., Koets, A. P., Rutten, V. P. M. G., Juste, R. A., & Estonba, A. (2010). Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the bovine solute carrier family 11 member 1 (SLC11A1) gene and their association with infection by Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. Journal of Dairy Science, 93(4), 1713–1721. [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, A., Liao, M., Morota, G., Tyler, R., Cockrum, R., Manohar, B. M., Ronald, B. S. M., Collins, M. T., & Sriranganathan, N. (2024). Retrospective Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Analysis of Host Resistance and Susceptibility to Ovine Johne’s Disease Using Restored FFPE DNA. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(14). [CrossRef]

- Tam, V., Patel, N., Turcotte, M., Bossé, Y., Paré, G., & Meyre, D. (2019). Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nature Reviews Genetics, 20(8), 467–484. [CrossRef]

- Mataragka, A., Sotirakoglou, K., Gazouli, M., Triantaphyllopoulos, K. A., & Ikonomopoulos, J. (2019). Parturition affects test-positivity in sheep with subclinical paratuberculosis; investigation following a preliminary analysis. Journal of King Saud University – Science, 31(4), 1399–1403. [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R. J. O., & Bienzle, D. (2005). Gene-expression changes induced by Feline immunodeficiency virus infection differ in epithelial cells and lymphocytes. Journal of General Virology, 86(8), 2239–2248. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. G., Kim, E. H., Lafferty, C. J., Miller, L. J., Koo, H. J., Stehman, S. M., & Shin, S. J. (2004). Use of conventional and real-time polymerase chain reaction for confirmation of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in a broth-based culture system ESP II. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 16(5), 448–453. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. L., Zhong, L., Begg, D. J., de Silva, K., & Whittington, R. J. (2008). Toll-like receptor genes are differentially expressed at the sites of infection during the progression of Johne’s disease in outbred sheep. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 124(1–2), 132–151. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K. J., & Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods, 25(4), 402–408. [CrossRef]

- Corneli, S., di Paolo, A., Vitale, N., Torricelli, M., Petrucci, L., Sebastiani, C., Ciullo, M., Curcio, L., Biagetti, M., Papa, P., Costarelli, S., Cagiola, M., Dondo, A., & Mazzone, P. (2021). Early Detection of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis Infected Cattle: Use of Experimental Johnins and Innovative Interferon-Gamma Test Interpretative Criteria. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 638890. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, C. B., Alonso-Hearn, M., Juste, R. A., Canive, M., Iglesias, T., Iglesias, N., Amado, J., Vicente, F., Balseiro, A., & Casais, R. (2020). Detection of latent forms of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection using host biomarker-based ELISAs greatly improves paratuberculosis diagnostic sensitivity. PLoS ONE, 15(9 September 2020). [CrossRef]

- Pinedo, P. J., Buergelt, C. D., Donovan, G. A., Melendez, P., Morel, L., Wu, R., Langaee, T. Y., & Rae, D. O. (2009). Candidate gene polymorphisms (BoIFNG, TLR4, SLC11A1) as risk factors for paratuberculosis infection in cattle. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 91(2–4), 189–196. [CrossRef]

- Canive, M., Casais, R., Jimenez, J. A., Blanco-Vazquez, C., Amado, J., Garrido, J. M., Juste, R. A., & Alonso-Hearn, M. (2020). Correlations between single nucleotide polymorphisms in bovine CD209, SLC11A1, SP110 and TLR2 genes and estimated breeding values for several traits in Spanish Holstein cattle. Heliyon, 6(6), e04254. [CrossRef]

- Okuni, J. B., Afayoa, M., & Ojok, L. (2021). Survey of Candidate Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in SLC11A1, TLR4, NOD2, PGLYRP1, and IFNγ in Ankole Longhorn Cattle in Central Region of Uganda to Determine Their Role in Mycobacterium avium Subspecies paratuberculosis Infection Outcome. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 614518. [CrossRef]

- Gopi, B., Vir Singh, R., Kumar, S., Kumar, S., Chauhan, A., Sonwane, A., Kumar, A., Bharati, J., & Vir Singh, S. (2022). Effect of selected single nucleotide polymorphisms in SLC11A1, ANKRA2, IFNG and PGLYRP1 genes on host susceptibility to Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis infection in Indian cattle. Veterinary Research Communications, 46(1), 209–221. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Cheng, D., & Wang, L. (2008). Association of polymorphisms of Nramp1 gene with immune function and production performance of large white pig. Journal of Genetics and Genomics, 35(2), 91–95. [CrossRef]

- Sechi, L. A., & Dow, C. T. (2015). Mycobacterium avium ss. paratuberculosis Zoonosis - The Hundred Year War - Beyond Crohn’s Disease. Frontiers in Immunology, 6, 96. [CrossRef]

- Badia-Bringué, G., Canive, M., & Alonso-Hearn, M. (2023). Control of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis load within infected bovine monocyte-derived macrophages is associated with host genetics. Frontiers in Immunology, 14. [CrossRef]

- Pinedo, P. J., Buergelt, C. D., Donovan, G. A., Melendez, P., Morel, L., Wu, R., Langaee, T. Y., & Rae, D. O. (2009). Association between CARD15/NOD2 gene polymorphisms and paratuberculosis infection in cattle. Veterinary Microbiology, 134(3–4), 346–352. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wang, S., Liu, T., Tu, W., Li, W., Dong, G., Xu, C., Qin, B., Liu, K., Yang, J., Chai, J., Shi, X., & Zhang, Y. (2015). CARD15 gene polymorphisms are associated with tuberculosis susceptibility in Chinese Holstein cows. PLoS ONE, 10(8). [CrossRef]

- Yaman, Y., Aymaz, R., Keleş, M., Bay, V., Ün, C., & Heaton, M. P. (2021). Association of TLR2 haplotypes encoding Q650 with reduced susceptibility to ovine Johne’s disease in Turkish sheep. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Juste, R. A., Vazquez, P., Ruiz-Larrañaga, O., Iriondo, M., Manzano, C., Agirre, M., Estonba, A., Geijo, M. v, Molina, E., Sevilla, I. A., Alonso-Hearn, M., Gomez, N., Perez, V., Cortes, A., & Garrido, J. M. (2018). Association between combinations of genetic polymorphisms and epidemiopathogenic forms of bovine paratuberculosis. Heliyon, 4(2), e00535. [CrossRef]

- Purdie, A. C., Plain, K. M., Begg, D. J., de Silva, K., & Whittington, R. J. (2011). Candidate gene and genome-wide association studies of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection in cattle and sheep: A review. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 34(3), 197–208. [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, A., Pelzer, K., & Sriranganathan, N. (2021). The Paratuberculosis Paradigm Examined: A Review of Host Genetic Resistance and Innate Immune Fitness in Mycobacterium avium subsp. Paratuberculosis Infection. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8. [CrossRef]

- Sadana, T., Vir Singh, R., Vir Singh, S., Kumar Saxena, V., Sharma, D., Kumar Singh, P., Kumar, N., Gupta, S., Kumar Chaubey, K., Jayaraman, S., Tiwari, R., Dhama, K., Kumar Bhatia, A., Singh Sohal, J., & Pradesh Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhayay Pashu Chikitsa Vigyan Vishwa Vidyalaya Evam Go-Anusandhan Sansthan, U. (2015). Single nucleotide polymorphism of SLC11A1, CARD15, IFNG and TLR2 genes and their association with Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis infection in native Indian cattle population. Indian Journal of Biotechnology, 14(4), 469–475.

- Dukkipati, V. S. R., Blair, H. T., Garrick, D. J., Lopez-Villalobos, N., Whittington, R. J., Reddacliff, L. A., Eppleston, J., Windsor, P., & Murray, A. (2010). Association of microsatellite polymorphisms with immune responses to a killed Mycobacterium avium subsp. Paratuberculosis vaccine in Merino sheep. New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 58(5), 237–245. [CrossRef]

- Kadarmideen, H. N., Ali, A. A., Thomson, P. C., Müller, B., & Zinsstag, J. (2011). Polymorphisms of the SLC11A1 gene and resistance to bovine tuberculosis in African Zebu cattle. Animal Genetics, 42(6), 656–658. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K., Zhang, B., Teng, Z., Wang, Y., Dong, G., Xu, C., Qin, B., Song, C., Chai, J., Li, Y., Shi, X., Shu, X., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Association between SLC11A1 (NRAMP1) polymorphisms and susceptibility to tuberculosis in Chinese Holstein cattle. Tuberculosis, 103, 10–15. [CrossRef]

- Holder, A., Garty, R., Elder, C., Mesnard, P., Laquerbe, C., Bartens, M. C., Salavati, M., Shabbir, M. Z., Tzelos, T., Connelly, T., Villarreal-Ramos, B., & Werling, D. (2020). Analysis of Genetic Variation in the Bovine SLC11A1 Gene, Its Influence on the Expression of NRAMP1 and Potential Association With Resistance to Bovine Tuberculosis. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Malo, D., Vogan, K., Vidal, S., Hu, J., Cellier, M., Schurr, E., Fuks, A., Bumstead, N., Morgan, K., & Gros, P. (1994). Haplotype mapping and sequence analysis of the mouse nramp gene predict susceptibility to infection with intracellular parasites. Genomics, 23(1), 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Paixão, T. A., Ferreira, C., Borges, Á. M., Oliveira, D. A. A., Lage, A. P., & Santos, R. L. (2006). Frequency of bovine Nramp1 (Slc11a1) alleles in Holstein and Zebu breeds. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 109(1–2), 37–42. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Larrañaga, O., Langa, J., Rendo, F., Manzano, C., Iriondo, M., & Estonba, A. (2018). Genomic selection signatures in sheep from the Western Pyrenees. Genetics Selection Evolution, 50(1). [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, B. M., Gupta, J. P., Pandey, D. P., Parmar, G. A., & Chaudhari, J. D. (2017). Molecular markers for resistance against infectious diseases of economic importance. Veterinary World, 10(1), 112–120. [CrossRef]

| Target | Primers (5’-3’) | Size | Thermal profile | Reference |

| IS900 | F1: AATGACGGTTACGGAGGTGGT R2: GCAGTAATGGTCGGCCTTACC Pr3: TCCACGCCCGCCCAGACAGG |

76 bp | 95°C for 3min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 3sec, 60°C for 20sec, 72°C for 1sec; 43°C for 30sec | [51] |

| 3’UTR SLC11A1 | F: ACCTGGTCTGGACCTGTCTCATCA R: CATTGCAAGGTAGGTGTCCCCAT |

346 bp | 95°C for 3min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 10sec, 59°C for 20sec, 72°C for 1sec; 43°C for 30sec | [43] |

| GAPDH | F: TTCCAGTATGATTCCACCCATG R: GCCTTTCCATTGATGACGAG |

80 bp | 42°C for 5min; 95°C for 15sec; 40 cycles of 95°C for 5sec, 52°C for 20sec, 72°C for 1sec; 43°C for 30sec | [52] |

| SLC11A1 mRNA | F: GGCTGTGGCTGGATTCAAAC R: ATGGTCAGCCAGAGGAGAATG |

168 bp | 42°C for 5min; 95°C for 15sec; 40 cycles of 95°C for 5sec, 57°C for 20sec, 72°C for 1sec; 43°C for 30sec | [43] |

| β-actin | F: TGTCTCTGTACGCTTCTGG R: GTGGTGGTGAAACTGTAGC |

190 bp | 95°C for 3min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30sec, 55°C for 30sec, 72°C for 30sec; 72°C for 3min | [50] |

| Species | Variant/Region Analyzed | Association with Resistance/Susceptibility | Notes | References |

| Sheep | Genetic influences (preliminary, candidate-based) | Suggested possible genetic effect on Johne’s disease susceptibility | Early evidence, not locus-specific | [21] |

| Sheep | GWAS (SNPs across genome) | Regions associated with MAP resistance; included SLC11A1 | SNP-based, no microsatellite resolution | [29] |

| Sheep | GWAS (antibody response to MAP) | Regions linked to immune response; SLC11A1 implicated | High-resolution genomic mapping | [28] |

| Sheep | Retrospective SNP analysis | Identified associations near SLC11A1 with MAP resistance | Based on FFPE DNA, SNP focus | [47] |

| Sheep | 3'UTR (GT)n microsatellite | (GT)21 and (GT)23 associated with resistance; (GT)22 and (GT)24 with susceptibility | Association found despite no difference in basal expression | This study |

| Goats | 3′UTR (GT)n microsatellite | Shorter alleles enriched in resistant goats | Consistent with ovine findings | [43] |

| Goats | Functional analysis, 3′UTR microsatellite | Variants affected inducible expression under MAP challenge | Demonstrated functional mechanism | [41] |

| Goats | 3′UTR microsatellite | Specific alleles associated with reduced paratuberculosis incidence | Validated earlier results | [44] |

| Cattle | Candidate gene SNPs (SLC11A1, TLR4, IFNG) | Associations with MAP susceptibility | Population-specific variation | [56] |

| Cattle | SNPs in SLC11A1 | Associated with MAP infection risk | Consistent across populations | [46] |

| Cattle | SNPs in SLC11A1 and others | Linked with breeding values for MAP traits | Large-scale genomic approach | [57] |

| Cattle | SNPs in SLC11A1 | No association with MAP infection | SNPs polymorphic variants showed no allele/genotype differences between cattle | [58] |

| Cattle | SLC11A1 SNP rs109453173 | Associated with resistance (GG genotype/G allele protective; CC/CG linked to susceptibility) | Case–control study; suggests potential resistance marker | [59] |

| Buffalo | 3′UTR microsatellite | Allelic variation influenced MCP1 mRNA after Brucella challenge | Functional immune effects | [45] |

| Pigs | SLC11A1 polymorphisms | Associated with immune traits | Cross-species evidence of functional role | [60] |

| Humans | SLC11A1 SNPs and promoter variants | Associated with tuberculosis susceptibility | Strong parallels with livestock | [38,61] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).