Introduction

This article is devoted to classical thermodynamics, so the term thermodynamics without further clarification means classical thermodynamics.

The second law of thermodynamics for a closed system is expressed by the Clausius inequality. In modern form:

| Reversible process |

|

| Irreversible process |

|

where S is entropy, Q is heat, and T is absolute temperature.

Often both expressions are written as a single inequality with a sign greater than equal, but it is useful to separate equality from inequality. First difference is with the temperature; the temperature of the environment stays in the inequality, and the temperature of the system is in the equality. Also, the derivation of the equality and the inequality is different from each other. The Clausius inequality is based on of physical arguments that is hard to express in language of mathematics as everything depends on continuum mechanics. The difficulties in studying thermodynamics are related to the inequality.

The equations above do not contain time explicitly, but the inequality is identified with the arrow of time—inequality prohibits the flow of processes in the opposite direction. The second law of thermodynamics is derived from the study of real systems and real processes that happens in time. The Clausius inequality generalizes these observations and relates them to the function of state, the entropy of the system.

The foundation of statistical mechanics is related to the problem of time-symmetrical laws of fundamental physics. The Clausius inequality sets the asymmetry between past and future states. Thus, the foundation of statistical mechanics relates to the question of how to obtain an asymmetry in time within the framework of time-symmetric laws of physics.

Jos Uffink is well known for his work in the field of statistical mechanics. Yet, he thought that it would be possible to simplify the foundation of statistical mechanics by removing the connection between the Clausius inequality and the arrow of time. This idea is presented in a paper with a vivid title ‘

Bluff Your Way in the Second Law of Thermodynamics’ in 2001 [

1]. The philosophers of physics apparently liked the paper. For example, in the 2022 book [

2] philosopher Brian Roberts is happy to refer to Uffink’s paper and in the chapter with another expressive title ‘

There is no thermodynamic arrow’ puts forward an even more radical position.

Uffink examines the Clausius inequality in the context of the history of thermodynamics, but the consideration is limited to five scientists: Carnot, Clausius, Thomson (Kelvin), Planck, Gibbs. In addition, the axiomatization of thermodynamics by mathematicians (Carathéodory and Lieb & Yngvason) is considered. The main conclusion of the paper is that the relationship between the arrow of time and the Clausius inequality is wrong, which implicitly leads to the denial of the Clausius inequality.

Let me give a quote from the paper conclusion; it shows the first problem with understanding thermodynamics:

‘It is often said that this behaviour of thermodynamical systems (i.e., the approach to equilibrium) is accompanied by an increase of entropy, and a consequence of the second law. But this idea actually lacks a theoretical foundation: for a non-equilibrium state there is in general no thermodynamic entropy—or temperature—at all.’

Unfortunately, this assertion is oversimplified. Let me give a simple example that clearly shows the relativity of the concepts of equilibrium and non-equilibrium state. Let us take a diamond under normal conditions in the air atmosphere. Is the diamond in an equilibrium or non-equilibrium state? There is a mechanical and thermal equilibrium, but there is no chemical equilibrium, because from the point of view of thermodynamics, the equilibrium state in this case is carbon dioxide. According to thermodynamics, the combustion reaction of a diamond should occur spontaneously, but, fortunately, such a reaction does not begin due to the high activation barrier; therefore, despite the thermodynamic instability, a diamond remains a good investment.

In this paper, I will not consider chemical reactions, but stay with temperature and temperature field, the initial area of applicability of the Clausius inequality. Unfortunately, the historical analysis in the paper [

1] is incomplete—the interaction of thermodynamics and continuum mechanics has not been considered. In the case of temperature, this means the Fourier heat equation.

I start by an overview of temperature and temperature field in 19th-century physics. Already Maxwell [

3] gave a definition of temperature that includes both the zeroth law and part of proposed in the next paper by Uffink [

4] the minus first law. The main difference is that Maxwell believed that the temperature introduced in this way can be easily generalized to the temperature field, whereas in papers [

1,

4] the temperature field is not even mentioned.

A simple example of using the Clausius inequality for a thermal system is presented, which is further generalized to the temperature field. A thermal field is an example of a non-equilibrium state, but in this case, both temperature and entropy exist. With this example, the concepts of local and global equilibrium are discussed. The difference between them is missed in [

1], which is one of the reasons for the incorrect conclusions.

The example shows the interplay between the heat equation and thermodynamics. This in turn reveals the logic to introduce the arrow of time during the development of thermodynamics. Thermodynamics does not contain time explicitly, but the Clausius inequality is a bridge between thermodynamics and continuum mechanics. In [

1] continuum mechanics is not mentioned, and this is the second reason for incorrect conclusions.

At the end, I discuss the axiomatization of thermodynamics from the point of view of scientific research. I have been engaged in chemical thermodynamics for a long time, and I discuss the axiomatization from this point of view. Also, the close connection between continuum mechanics and thermodynamics implies that the axiomatization of thermodynamics without continuum mechanics cannot deal with the Clausius inequality.

Temperature and Temperature Field in 19th Century Physics

In a follow-up paper, Brown and Uffink [

4] discuss the zeroth law of thermodynamics. They suggest leaving only the transitivity of temperature behind it, as defined by Fowler. Let me quote Fowler and Guggenheim from the book ‘

Statistical Thermodynamics’ [

5] of 1939:

‘The first step is to introduce the concept of temperature. As a natural generalization of experience we introduce the postulate: If two assemblies are each in thermal equilibrium with a third assembly, they are in thermal equilibrium with each other. From this it may be shown to follow that the condition for thermal equilibrium between several assemblies is the equality of a certain single-valued function of the thermodynamic states of the assemblies, which may be called the temperature t, any one of the assemblies being used as a “thermometer” reading the temperature t on a suitable scale. This postulate of the “Existence of temperature” could with advantage be known as the zeroth law of thermodynamics.’

Yet to use the zeroth law, the establishment of thermal equilibrium is required and in [

4] it is suggested to define one more law before the zeroth law; hence it is called the minus the first law:

‘An isolated system in an arbitrary initial state within a finite fixed volume will spontaneously attain a unique state of equilibrium.’

The question raised in [

4] is correct: where the asymmetry in time appears in the structure of thermodynamics. Let us however consider it in the context of the historical development of thermodynamics. James Maxwell was the first to give a formal definition of temperature in 1871 in his book ‘

Theory of Heat’ [

3]; before Maxwell, this was apparently taken for granted:

‘Definition of Temperature.—The temperature of a body is its thermal state considered with reference to its power of communicating heat to other bodies.’

‘Definition of Higher and Lower Temperature.—If when two bodies are placed in thermal communication one of the bodies loses heat, and the other gains heat, that body which gives out heat is said to have a higher temperature than that which receives heat from it.’

‘Cor. If when two bodies are placed in thermal communication neither of them loses or gains heat, the two bodies are said to have equal temperatures or the same temperature. The two bodies are then said to be in thermal equilibrium.’

‘Law of Equal Temperatures.—Bodies whose temperatures are equal to that of the same body have themselves equal temperatures.’

Maxwell summarizes the practice of thermometry and gives a formal definition that is enough to construct the practical temperature scale. A similar formal introduction of temperature is an integral part of subsequent books on thermodynamics in the 19th century.

Thus, in the 19th century, it was understood that temperature is a prerequisite for thermodynamics and therefore it must be formally introduced before the first and second laws. In Maxwell’s consideration, the concept of temperature is combined with the establishment of thermal equilibrium. Otherwise, the operation of a thermometer would be impossible.

Yet, for the first law the establishment of mechanical equilibrium is also necessary; the pressure in the system becomes equal to the pressure above the piston. The question is now whether this requirement should belong to the construction of thermodynamics, in other words, whether thermodynamics requires an analogous definition of pressure. Thermodynamics was developed in close connection with other areas of physics. Pressure was a part of hydrodynamics and mechanics; approach to mechanical equilibrium was a part of these disciplines. Therefore, in the development of thermodynamics it was assumed that mechanics was responsible for pressure. In thermodynamics, only a reference to mechanics was sufficient: the achievement of mechanical equilibrium was a part of mechanics.

Moreover, temperature was required in the study of transport equations and mechanics of a deformable body. The modern name is continuum mechanics, which includes the mechanics of solids, liquids, and gases. Thus, Maxwell’s temperature definition was used not only in thermodynamics but it was an integral part of the development of continuum mechanics. Perhaps this was one of the reasons why the term zeroth law of thermodynamics was not introduced in the 19th century—the practical temperature scale belonged not only to thermodynamics. Fowler and Guggenheim [

5] have forgotten about this circumstance.

The above raises the question of the relationship between thermodynamics and other theories in continuum mechanics. Let us consider the minus first law of thermodynamics proposed in [

4]. The question is whether this is a law of thermodynamics or a law for all theories of continuum mechanics. In other words, whether the foundation of thermodynamics must include the foundation of mechanics. Unfortunately, in papers [

1,

4] there is no answer to this question, since the authors have forgotten about the existence of continuum mechanics.

In continuum mechanics, temperature gradients (temperature fields) are introduced; for example, the Fourier heat equation and the Navier-Stokes equation contain a thermal field. Maxwell, in his book [

3] considered the temperature field and he did not see a problem with the transition from his temperature definition to temperature field; this is also true of other physicists of the 19th century. In general, the asymmetry of past and future states belongs to continuum mechanics, as the equations there are asymmetrical in time. The Clausius inequality follows from asymmetry in time in continuum mechanics. Below this is considered with an example of interaction between thermodynamics and the heat equation.

Simple Example of Establishing Thermal Equilibrium

For an isolated system, the second law is reduced to the statement that the entropy of an isolated system increases in a spontaneous process (the internal energy

U and volume

V remain constant), and when equilibrium is reached, the entropy reaches a maximum:

Let us consider a simple example of achieving thermal equilibrium in an isolated system; this will be as a basis for the discussion that follows. The example shows how inequality above is used in practice, and thus it reveals the meaning and connection of the inequality with the arrow of time.

The internal energy and entropy of simple substances with constant mass—

U(

T,

V) and

S(

T,

V)—according to the thermodynamics laws are related to heat capacity and the thermal equation of state:

Let us employ these equations and the equilibrium criterion on the simplest example, when an isolated system consists of two subsystems with the same heat capacity (

CV,1 =

CV,2) that does not depend on temperature. Two subsystems are separated from each other by a fixed wall—index 0 characterizes the initial temperature values:

The subsystem volume does not change, and the only possibility of change is related to temperature: the wall allows heat to pass through. Thus, in the equations above, only the temperature part remains (dV=0). Let us assume that each subsystem is in a state of local equilibrium, that is, there are no temperature gradients in each of the subsystems. In the discussion that follows, a more general case will be considered.

The total energy of the system is conserved:

U =

U1 +

U2 = const; hence in the case of the equal heat capacities, a simple relation between the temperatures is obtained:

The variable x shows the changes in temperature, the increase in temperature in one subsystem is equal to the decrease in temperature in the other. The total internal energy does not depend on x, since the last relation is obtained from the total internal energy being constant.

At the same time, the total entropy depends on the values of the current temperatures in the subsystems, that is, on the value of

x. In the equation below, the integral of entropy over temperature is taken, and

S0 denotes the total entropy in the initial state:

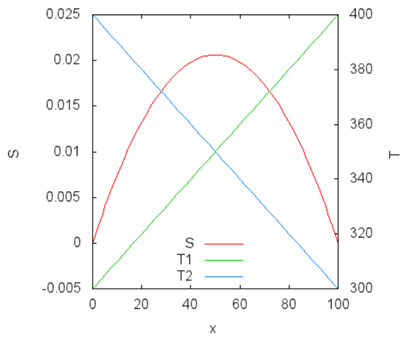

Let us plot this function—the dependence of the total entropy on

x. Below this is plotted for the case of initial temperatures of 300 K and 400 K, with

S0=0,

CV=1 with Gnuplot (the script is in the

Appendix).

The change in temperature is shown on the right axis of the ordinate: T1 = 300 + x, T2 = 400 − x, the change in entropy on the left. The entropy reaches the maximum value at x = 50 when the temperatures of the subsystems become equal.

The maximum of entropy corresponds to zero of the entropy derivative over

x, which allows us to get the answer in a general form:

The example shows the use of the entropy of an isolated system to compute the equilibrium state. The red curve in the figure corresponds to all possible non-equilibrium states of the system, and the maximum value on this curve corresponds to the global equilibrium. The Clausius inequality also sets the direction of a spontaneous process—the entropy of an isolated system can only increase. This was the reason to connect the change in entropy of an isolated system and the arrow of time.

In the language of heat engines, the inequality reflects the asymmetry of work and heat. All work can be converted into heat, but only a part of heat can be converted into work. In an isolated system, which includes both the heat engine and the surrounding bodies, the possibility to perform work is eventually lost as energy is dissipated.

The concept of local equilibrium is a key to use thermodynamics. In the paper ‘

What if energy flowed from cold to hot?’ [

6], the authors propose the counterfactual thought experiment expressed in the title. The authors believe that the denial of the Clausius formulation of the second law “heat cannot pass by itself from a cold body to a hot body” leads to the denial of the existence of thermal equilibrium. This, according to authors, makes it impossible to introduce temperature and heat, and thus the first law of thermodynamics. The logic for such a conclusion is related to the connection of the temperature definition with the establishment of thermal equilibrium. Authors thus argue that the Clausius formulation is related to the establishment of thermal equilibrium.

The introduction of local and global equilibrium allows us to solve such a problem easily. The temperature definition should be considered as local equilibrium (subsystem in an isolated system) and not as global equilibrium (uniform temperature in the entire isolated system). This was the logic by the development of thermodynamics in the 19th century. Clausius would have been surprised to learn that his formulation of the second law influences the temperature definition.

The example in this section reveals the logic of considering the first and second laws in the 19th century. There is a clear separation between the first law from the second. According to the first law, energy can pass from one subsystem to another in any direction, while maintaining the concept of the subsystem temperature (local equilibrium). At the level of the first law, there is a set of possible non-equilibrium states, shown by the red line in the figure above. The Clausius inequality makes it possible to find a state of global equilibrium that corresponds to the maximum entropy of the isolated system.

Continuum Mechanics and Clausius Inequality

In the example in the previous section, there is no time. This is a distinctive feature of thermodynamics; it says nothing about how fast the equilibrium will be reached. In an isolated system, thermodynamics ranks states according to the value of entropy, and from this follows a conclusion about global equilibrium, as well as the possibility or impossibility of the transition from one state to another.

The heat equation determines the process speed, but the heat equation is compatible with the Clausius inequality. The example above corresponds to high thermal conductivity of the substance in the subsystems and the high thermal resistance between them. In the one-dimensional case, the direction of the process is unambiguous, and therefore it can be easily shown that the solution of the heat equation agrees both with the equilibrium state and with the direction of the process.

To consider a more general case, it is necessary to introduce more subsystems. In each of them, the temperature will be considered uniform (local equilibrium), but there will be no global equilibrium. In the multidimensional case, thermodynamics does not allow us to predict either the time to reach the equilibrium or the path of the process. The Clausius inequality in an isolated system ranks possible states by the value of entropy, sets the global equilibrium, and shows the possible transitions from the previous state to the next one. However, in the multidimensional case, for a single state there are several states with higher entropy, so at the level of thermodynamics it is impossible to choose the real path of the process; the latter is given by the heat equation.

A temperature field is obtained in the limit by dividing the initial system into infinitesimal subsystems. This opens the way to employ entropy when dealing with non-equilibrium states with a thermal field. For example, Poincaré in his book on thermodynamics [

7] thus generalized the Clausius inequality to the case of the temperature field; he remained within the framework of thermodynamics without time in the explicit form.

The heat equation was obtained independently of thermodynamics. In an isolated system, it leads to the global equilibrium state when time goes to infinity without using entropy explicitly. To prove the compatibility of the heat equation and the Clausius inequality in the general case is a more difficult task, but this has been successfully done. A general question arises as to why then thermodynamics was not combined with the heat equation.

The reason was that thermodynamics was developed in parallel with continuum mechanics (the heat equation, the Navier-Stokes equations, mechanics of a deformable body, etc.) and their integration happens to be too difficult. Moreover, attempts for such integration continue to the present day in the form of non-equilibrium thermodynamics, see, for example, [

8,

9]. Thus, the separation of thermodynamics from continuum mechanics was a useful compromise during the development of physics in the 19th century. This also opened the way to the rapid solution of many practical problems related to the search for the maximum possible efficiency and the calculation of equilibrium composition.

The Clausius inequality is based on good physical arguments. Also, the Clausius inequality is consistent with both the heat equation and other transport equations. All together led to the generalization of time asymmetry in different equations of continuum mechanics within the united framework of the Clausius inequality. It was assumed that all the equations of continuum mechanics should ultimately satisfy the Clausius inequality, which was regarded as a bridge between thermodynamics and continuum mechanics.

A few words about the status of Clausius inequality in modern thermodynamics. It is based on the statement about the impossibility of a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. In the case of heat engines, the Clausius inequality follows, but then it is extended to all processes in continuum mechanics. Thus, the main justification for the Clausius inequality is the practice of thermodynamic research and practical applications developed on its basis. Classical thermodynamics has been actively used in practice for more than a century and a half. A perpetual motion machine of the second kind has not yet been created, which gives reason to believe that the Clausius inequality is correct. Here is a quote from a 2005 book with the expressive title ‘

Challenges to the Second Law of Thermodynamics’ [

10]; the book deals with many attempts to create the perpetual motion machine of the second kind:

‘In this volume we will attempt to remain clear on this point; that is, while the second law might be potentially violable, it has not been violated in practice.’

In the 20th century, the goal was to unify thermodynamics with continuum mechanics by means of non-equilibrium thermodynamics. However, in [

1] it was decided to ignore this development:

‘Here, a more interesting connection with the arrow of time could result. This work seems to have resulted in a large number schools, and I can therefore say little about it. It is characteristic of this type of work that it is focused on applications and gives comparatively little attention to the foundations and logical formulation of the theory. Usually, a time-asymmetric statement about entropy production is postulated. The question how the entropy of a non-equilibrium state is to be defined, and the proof that it exists and is unique for all non-equilibrium states, still seem to be largely unexplored.’

To some extent, this statement is true, since there are many different cases in continuum mechanics that require an extension of existing theories. At the same time, the arrow of time (the asymmetry of past and future states) comes from continuum mechanics, so a discussion of the time arrow without continuum mechanics would be incomplete. In [

1] there are many Truesdell’s quotes with the critic of thermodynamics, but Truesdell did not reject the Clausius inequality; Truesdell believed that it must be related to non-equilibrium thermodynamics. Truesdell would have been clearly offended and disappointed by the statement above.

Physics and Mathematics in Thermodynamics

The question of axiomatization leads to a discussion of the relationship between physics and mathematics. Thermodynamics is based on the Gibbs mathematical formalism, developed in the 1870s. It took time for this formalism to enter the practice of scientific research, but in general the Gibbs formalism remains to the present day. The formalism is based on the fundamental equation:

which combines the laws of thermodynamics, as well as on the Clausius inequality, which serves as a criterion for the spontaneous change and a criterion for equilibrium. In the equation above, to consider additional effects, such as in electrochemistry, additional terms appear.

There were many successful applications thermodynamics in many areas. I worked in the field of chemical thermodynamics, so I will give an example of creating thermodynamic tables [

11,

12], which combined a huge number of results of experiments conducted by chemists and physicists. The tables tabulate, among other things, the entropy of substances; to discuss the question of what entropy is, it is extremely useful to understand which experiments and how led to the entropy column in these tables.

The development of these thermodynamic tables is related to the launch of missiles—this is vividly shown by the name of the American reference book: Joint-Army-Navy-Air Force Thermochemical Tables. The name of the Soviet handbook is more peaceful, but the goals were the same. Thermodynamics allows us to compute the adiabatic temperature of the flame during the combustion of rocket fuel, which in turn leads to a quick assessment of the thrust. This example displays one of the areas of application—the calculation of equilibrium composition without knowledge of the mechanism and kinetics of the ongoing processes. This once again emphasizes the usefulness of separating thermodynamics from continuum mechanics by eliminating time in the explicit form.

Let us consider what the axiomatization of thermodynamics could add to the Gibbs formalism. I will begin a wonderful quote by mathematician V. I. Arnold [

13]. In [

1] the first sentence is given to show how poorly the teaching of thermodynamics is organized. I will give two sentences, since the second explains the first:

‘Every mathematician knows it is impossible to understand an elementary course in thermodynamics. The reason is that thermodynamics is based—as Gibbs has explicitly proclaimed—on a rather complicated mathematical theory, on the contact geometry.’

Without the second sentence, the first one looks ambiguous, but in this form everything becomes clearer. There is a mathematical formalism to analyze differential forms that fits the fundamental equation. I must confess that I first saw the term contact geometry from Arnold’s paper. My cursory acquaintance with the topic showed that everything remains—the Gibbs mathematical formalism does not change. The changes concern the use of a new mathematical ‘bird’ language to work with differentials of a function in several variables, which, however, makes this consideration more rigorous. Of course, it is impossible to find a proof of the Clausius inequality in contact geometry—the Clausius inequality still remains at the level of physical arguments.

In [

1] the axiomatization of Lieb & Yngvason’s [

14] was considered. This axiomatization of thermodynamics appeared in 1999, and I was surprised that mathematicians decided to develop a new formalism after the successful use of the Gibbs formalism in practice for more than a hundred years. I opened this work—it is written in dry mathematical language and begins with fifteen axioms.

I respect the work of mathematicians; my personal work was inextricably linked to the use of mathematical results. I must admit that I only briefly browsed the paper [

14], so it is possible that I have missed something important. I have not understood the relation of the new development to the Gibbs formalism. Whether the Gibbs formalism is to be used as usual, or whether the authors [

14] believe that everyone should switch to the use of the new formalism. In the introduction to the paper only greater rigor was mentioned and I could not find the answer to such a question.

It was unclear to me what kind of rigor was suggested—mathematical or physical. From the point of view of mathematics, the relationship of the new formalism with contact geometry remained unclear. From the point of view of physics, thermodynamics is inextricably linked with continuum mechanics; I repeat—the Clausius inequality is a bridge between thermodynamics and continuum mechanics. Therefore, it is impossible to prove the Clausius inequality in a strictly mathematical way without axiomatization of complete continuum mechanics. At the same time without the Clausius inequality, thermodynamics would be empty, as one could not use it in practice. The example considered in this paper shows that to understand the Clausius inequality, the axiomatization at least must include a temperature field, but in [

14] the temperature field is not even mentioned.

In conclusion, my personal view—a viewpoint of a person who has used thermodynamics to solve practical problems. Specific research includes the implicit interaction of three groups of scientists: mathematicians (mathematical formalism), theoretical physicists (theories of physics) and practitioners (engineers, chemists, experimental physicists—who conduct specific research). In the case of thermodynamics, there is the established Gibbs formalism based on the Clausius inequality, and in practice thermodynamics is used together with continuum mechanics. There are scientists who study kinetic and transport phenomena, and there are scientists who study the equilibrium state. They work together as they study the same physical systems. The Clausius inequality emphasizes the unity of physics—different scientists study the same system, but they study different aspects of that system.

There are disagreements among scientists. Mathematicians criticize the lack of rigor in the transition between the mathematical equations, theoretical physicists are dissatisfied with the incompatibility of the theories of physics, experimental physicists complain about the imperfection of measuring instruments and the impossibility of measuring the necessary property, chemists and engineers complain about the lack of possibility in existing theories to consider a new problem that has appeared. At the same time, there are internal disputes about what rigor is, what a unified theory is, and what equation should be used in a particular case.

I don’t see how the axiomatization of thermodynamics can help in this case. Once again, I respect the work of mathematicians and have always tried to use new available mathematical tools to solve problems. However, changing the existing Gibbs formalism in thermodynamics seems to me an insurmountable and unnecessary task. In this case, it would be necessary to start by demonstrating the problems in the Gibbs formalism, only in this case a mathematician can attract interest from other groups of scientists. Also, we must not forget about the close connection between thermodynamics and continuum mechanics. The axiomatization of thermodynamics in isolation from continuum mechanics will not lead to the physical rigor.

Conclusion

If a ball is thrown on the floor, then after a few jumps, the ball stops. In this respect, Poincaré noted [

7] that in mechanics of the early 19th century, the principle of the impossibility of perpetual motion was in force, but energy was not conserved. It was clear to everyone that resistance forces and frictional forces lead to the disappearance of energy, and perhaps this was the reason why the concept of energy was at that time absent.

The introduction of the law of conservation of energy in thermodynamics changed the situation. Now it was necessary to show that the energy is conserved when the ball falls and stops moving. Resistance and frictional forces release heat and hence the ball and the environment get hotter. The Clausius inequality serves as a universal explanation. Energy is dissipated; energy is conserved, but it is converted into a form that can no longer be used to obtain work.

It is unlikely that there are physicists who doubt the increase in the entropy of an isolated system in which the ball falls and stops moving. However, writing down the corresponding equations is an extremely non-trivial task. Moreover, proof is ultimately impossible without the use of continuum mechanics.

It is important to remember that the asymmetry in time comes from the equations of continuum mechanics. In this sense, it would be reasonable to start the discussion of the arrow of time with continuum mechanics rather than with thermodynamics.

Appendix A

Gnuplot script to produce the figure:

set terminal png enhanced size 500,400

set output ‘fig1.png’

set xlabel ‘x’

set ylabel ‘S’

set y2label ‘T’

Set y2tics

set ytics nomirror

set key center bottom

plot [x=0:100] log((300+x)/300)+log((400-x)/400) title ‘S’, 300+x axis x1y2 title ‘T1’, 400-x axis x1y2 title ‘T2’

References

- Jos Uffink, Bluff your way in the second law of thermodynamics. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 32, no. 3 (2001): 305-394.

- Bryan W. Roberts, Reversing the arrow of time. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Maxwell, Theory of Heat, 1871 (first edition).

- Harvey R. Brown, Jos Uffink. The origins of time-asymmetry in thermodynamics: The minus first law. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 32, no. 4 (2001): 525-538. [CrossRef]

- R. Fowler, E. Guggenheim, Statistical Thermodynamics, 1956, the first edition in 1939.

- Harvey S. Leff, Richard Kaufman. What if energy flowed from cold to hot? Counterfactual thought experiments. The Physics Teacher 58, no. 7 (2020): 491-493. [CrossRef]

- Henri Poincaré, Termodynamique, 1908, first published in 1892. I have read Russian translation, 2005.

- Georgy Lebon, D. Jou. Early history of extended irreversible thermodynamics (1953–1983): An exploration beyond local equilibrium and classical transport theory. The European Physical Journal H 40, no. 2 (2015): 205-240. [CrossRef]

- Ingo Müller, Wolf Weiss. Thermodynamics of irreversible processes—past and present. The European Physical Journal H 37, no. 2 (2012): 139-236. [CrossRef]

- Vladislav Capek and Daniel P. Sheehan. Challenges to the second law of thermodynamics, 2005.

-

Thermodynamic properties of individual substances (In Russian). In four volumes, third edition, 1978 - 1982.

- IST-JANAF Thermochemical Tables, Fourth Edition, Monograph No. 9, Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 1998.

- V. I. Arnold, Contact geometry: The geometrical method of Gibbs’s thermodynamics, in Proc. Gibbs Symp (New Haven, CT,), pp. 163-179, 1990.

- Elliott H. Lieb and Jakob Yngvason. The physics and mathematics of the second law of thermodynamics. Physics Reports 310, no. 1 (1999): 1-96. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).