1. Introduction

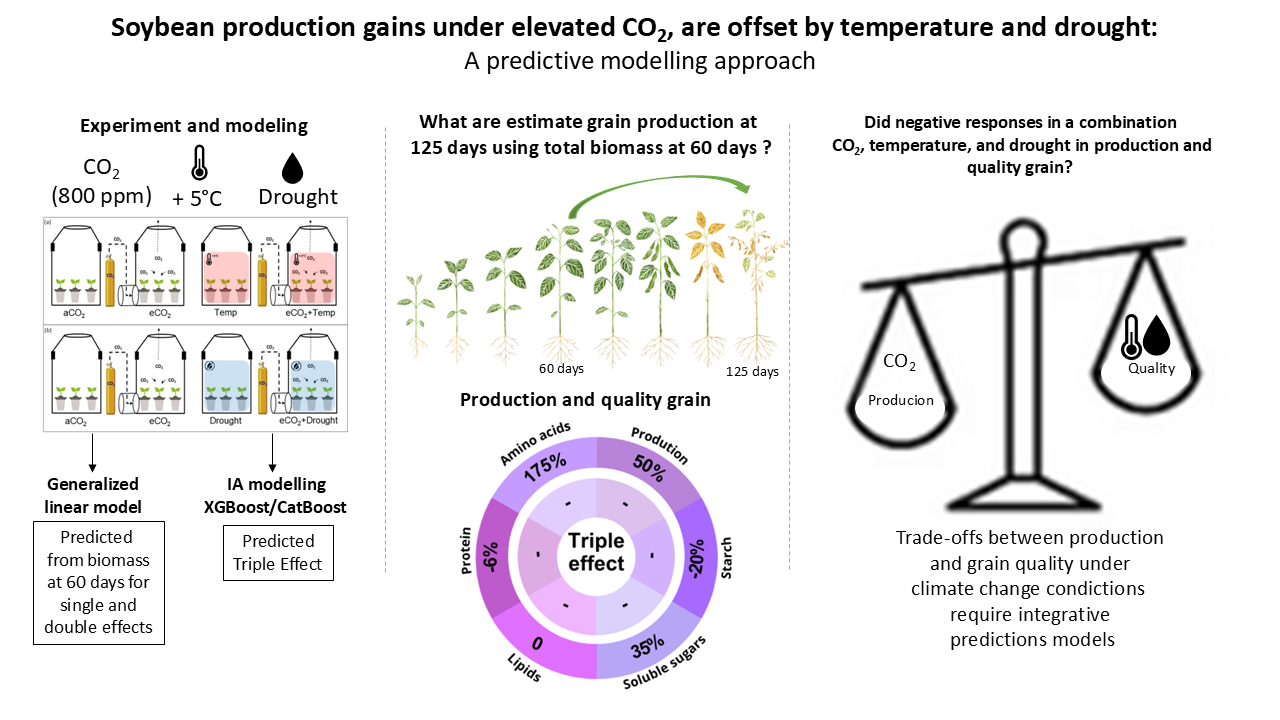

Soybean (Glycine max) plays a key role in global food systems, contributing significantly to nutrition, bioenergy, and biotechnological innovations (Palacios et al., 2019; X. Wu et al., 2018). It is the world's leading seed crop, supplying about 29% of global vegetable oil and serving as a major protein source (SoyStats, 2023). Brazil is the largest producer (157 Mt - million tons) that is responsible for 39% of global production, followed by the United States (113 Mt – 28%), Argentina (50 Mt – 13%), and China (20 Mt – 5%) (USDA, 2024). In 2021, Brazil’s soybean productivity (3.5 kg. ha-1) surpassed the global average (2.8 kg. ha-1), consolidating its position as the largest exporter with 86 million tons (ANEC, 2022; CONAB, 2021; USDA, 2024). However, soybean production is increasingly threatened by climate change scenarios, especially by elevated CO2, high temperature, and drought, which can disrupt both production and quality. Thereby impacting global food security and economic stability (Beck, 2013).

Climate change manifests through interconnected stressors affecting soybean growth and development. Elevated CO₂ (eCO2) is projected to increase crop biomass and yield by enhancing photosynthesis, though its effect on soybean quality remains unclear (D. Li et al., 2013; A. Wang et al., 2018). Studies show that soybeans under eCO2 increased in net photosynthesis which led to an increase in biomass and pod production (15%) (Zheng et al., 2020). However, eCO2 can simultaneously reduce grain size, weight, seed per pod, and nutritional content (Digrado et al., 2024; Poudel et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2020; Zipper et al., 2016).

Temperature and water availability are critical climate-related stressors affecting soybean production. Optimal growth occurs between 20–25°C, while prolonged exposure to temperatures above 29°C reduces pod number and seed weight, and temperatures exceeding 35°C severely disrupt flowering and pod set (Cai et al., 2020; Mourtzinis et al., 2015; Onat et al., 2017; Streck, 2005). Each 1°C increase has been linked to a 17% yield reduction (Yang et al., 2023). Water availability also plays a direct role in productivity (Manavalan et al., 2009; Rezaei et al., 2015); drought impairs photosynthesis and seed development, causing yield losses of up to 40% (Gray et al., 2016; Poudel et al., 2023; Zipper et al., 2016). Soybean yield is highly sensitive to climate variability and soil moisture during the growing season (Sentelhas et al., 2015). However, since 1961, global agricultural productivity has declined by 21%, particularly in tropical regions like Latin America, due to climate-induced stressors (Ortiz-Bobea et al., 2021).

Studies evaluating plant physiological responses to ambient stress often focus on isolated factors such as temperature, drought, and eCO2 (Ainsworth & Lemonnier, 2018; Ainsworth & Long, 2021; Fortirer et al., 2023; Fu et al., 2015). Therefore, experiments need to address these combined effects. In particular, variables like biomass offer projections for soybean production in Brazil, helping to address the challenges posed by climate change (Bui et al., 2024; Monteiro et al., 2022). Spatialized crop models are increasingly applied at multiple scales in modern agriculture, raising new questions about their performance evaluation and application in precision agriculture (Pasquel et al., 2022). Climate projections show a heightened frequency of drought periods (Assad et al., 2016; Beniston et al., 2007; FAO, 2023; Gourdji et al., 2013; Marengo et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2017), which reduce soybean production due to sensitivity to water deficit (Gray et al., 2016).

The complex interaction of climate variables on soybean production necessitates the use of modeling approaches. Traditional statistical models often fail to capture the nonlinear relationships and interactions between multiple environmental factors (Nelder & Wedderburn, 1972). Generalized Linear Models (GLM) extend traditional linear regression by allowing for response variables with non-normal distributions (Nelder & Wedderburn, 1972). GLM has been used to determine the physiological quality of seeds, enabling the estimation of both germination time and uniformity through this methodology (Jardim Amorim et al., 2021). GLM models have demonstrated superior performance in production prediction tasks, as evidenced by lower root mean square error (RMSE) compared to other models. These results highlight the GLM’s greater robustness in modeling complex agricultural data, reinforcing its suitability for predicting crop yields under varying environmental conditions (Shastry et al., 2017).

Predictive models that incorporate stressors such as eCO2, high temperature, and drought can guide decision-making and inform timely interventions (Jin et al., 2017). However, most existing models assess these factors in isolation, often overlooking their complex interactions (Jin et al., 2017; Zandalinas & Mittler, 2022). Machine learning approaches are capable of capturing nonlinear relationships between environmental variables and crop responses. Among these, two ensemble methods have stood out due to their robustness and predictive performance: Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), which is widely adopted for its ability to model structured data and capture complex, multivariate interactions (Chen & Guestrin, 2016; Y. Li et al., 2023); and CatBoost, a gradient boosting algorithm specifically designed to improve generalization through ordered boosting and efficient handling of categorical features (Hancock & Khoshgoftaar, 2020; Prokhorenkova et al., 2018). Its minimal preprocessing requirements and symmetric tree structures further enhance predictive robustness and efficiency. Building on these strengths, this study aimed to: I) Evaluate the predictive performance of generalized linear models (GLMs) using physiological and morphological variables measured at 60 DAE to forecast soybean grain production and quality at 125 DAE under different environmental conditions; and II) Model the combined effects of elevated CO₂, temperature, and drought (Triple Effect) on soybean grain production by leveraging experimental datasets with double-factor treatments (e.g., elevated CO₂ + temperature or elevated CO₂ + drought), and assess the predictive performance of advanced machine learning algorithms, including XGBoost and CatBoost.

This study aimed to: I) Evaluate the predictive performance of generalized linear models (GLMs) using physiological and morphological variables measured at 60 DAE to forecast soybean grain production and quality at 125 DAE under different environmental conditions; and II) Model the combined effects of elevated CO₂, temperature, and drought (Triple Effect) on soybean grain production by leveraging experimental datasets with double-factor treatments (e.g., elevated CO₂ + temperature or elevated CO₂ + drought), and assess the predictive performance of advanced machine learning algorithms, including XGBoost and CatBoost.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Design

Soybean were grown in open-top chambers (OTCs) in São Paulo, Brazil (23°34′1''S, 46°43′49″W) from September 2018 to February 2019 using seeds from the variety ‘MG/BR-46 Conquista’ (Embrapa, Brasília, DF - Brazil). Seeds were germinated at 25 °C with a 12/12 h photoperiod under natural light conditions in vermiculite. Five days after emergence (DAE), soybean seedlings were selected and transplanted into 5-liter plastic pots filled with the substrate. After, plants were transferred to open-top chambers (OTC) in two independent experiments (temperature and drought) coupled to ambient or elevated CO2 concentrations. DAE represents the period that initiated the CO2 injections in juvenile plants, starting 15 DAE. The models of OTCs are described in Arenque et al., (2014) and Palacios et al., (2019). Furthermore, microclimatic measurements (inside the OTCs) were monitored by temperature, gas, and humidity sensors and stored in Remote Integrated Control System software (RICS), during the experiment period.

Two independent experiments were conducted: The first experiment combined elevated CO

2 and elevated temperature in four treatments: i) ambient CO

2 (aCO

2 (400 ppm - parts per million)) and ambient temperature; ii) Temp (400 ppm and increased temperature +5°C); iii) elevated CO

2 (eCO

2 (800 ppm and ambient temperature)); and iv) eCO

2+Temp (800 ppm and increased temperature +5°C). The second experiment was conducted with drought and elevated CO

2 concentration including: i) aCO

2 (400 ppm) and ambient temperature; ii) Drought (400 ppm and watering reduction); iii) eCO

2 (800 ppm and well watering); and iv) eCO

2+Drought (800 ppm and watering reduction) (

Figure S1). Drought treatments (water restriction) received only 100 mL of water every three days, after the beginning of flowering (45 DAE) until the end of the experiment (125 DAE), simulating drought conditions during the flowering and grain development phases.

In addition, 100 mL of Hoagland's nutrient solution was added to all plants once a week (Hoagland et al., 1993). After 60 DAE and 125 DAE, ten individuals from each treatment were randomly selected for harvest. Leaves, stems, roots and pods were collected separately. All organs were collected at 60 and 125 DAE, except for pods, which were only collected at 125 DAE. Leaves, stems, and roots were dried at 70 °C until they reached constant mass, and the pods were frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized. After drying, the pods were separated into grains, including both developed and undeveloped pods. Grains were analyzed for quality and chemical composition, including soluble sugars, starch, amino acids, lipids, carbon, and nitrogen. All the organs were ball-milled into a fine powder and then isolated for biochemical analysis.

2.2. Non-Structural Carbohydrates in Grain

To analyze the soluble sugars, 10 mg of powdered grains were submitted to four extractions with 80% ethanol (v/v) at 80 °C (Arenque et al., 2014). The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 14,000 rcf at 4°C and vacuum-dried (Thermo Scientific, Savant SC 250 EXP, Asheville, NC, USA). The soluble sugars were resuspended in water and the pigments were separated by chloroform (Pagliuso et al., 2022). The aqueous portion containing the soluble sugars was analyzed using high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD-ICS 3000 system, Dionex-Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) with a CarboPac PA1 column in a 27-minute isocratic run, eluted with 150 µM sodium hydroxide.

For starch removal and quantification, the dried pellet from alcohol extraction was incubated with 120 U/mL of α-amylase (Megazyme) diluted in 10 mM MOPS pH 6.5 at 75 °C for 1h and followed by 30 U.mL-1 of amyloglucosidase diluted in 100 sodium acetate mM pH 4.5 at 50 °C for 1 h. To aliquots of the digestion was added a mixture containing glucose oxidase (1,100U.mL-1), peroxidase (700 U.mL-1), 4-aminoantipirin (290 µmol.L-1), and 50mM of phenol at pH 7.5. The reaction was heated at 30 °C for 15 min and read at 490 nm using a glucose (Sigma) standard curve (Amaral et al., 2007; Arenque et al., 2014).

2.3. Lipids and Fatty Acids in Grain

The total lipids were extracted from 50 mg of dry mass by three successive extractions with 1 mL of hexane at 50 °C for 30 min with continuous stirring. The hexane extract was dried by evaporation, and the gravimetric mass was measured to determine the total lipids. The total oil was resuspended in Milli-Q water, and the recovered fatty acids were subjected to a transesterification process to identify the methyl esters of the fatty acids (Christie & Hutton, 1993). Fatty acids were treated with 5% methanolic H2SO4 solution and toluene for 1 h at 80 °C and then homogenized with 0.5 M NaCl and 100% dichloromethane. The aqueous phase was discarded, and the organic phase (lower phase) was collected, washed with dichloromethane, purified with 0.05 M NaCl, and then treated with Na2SO4.

The fatty acid methyl esters after the dichloromethane reduction were resuspended in hexane for quantification in a gas chromatograph with flame ionization detector (GC-FID-model 6850) using HP-Innowax fused silica capillary column (Cross-Linked PEG, 30 m x 320 μm x 0.50 µm). The temperature ramp was 150 ºC for 1 min, 15 ºC/min until 225 ºC, 5 ºC/min until 260 ºC, 270 °C for 7 min. Fatty acid methyl esters were identified by comparing their retention times and concentrations with those of specific methyl ester standards.

2.4. Carbon, Nitrogen, C/N Ratio, and Total Proteins in Grain

A 1.5 mg powdered sample was weighed and placed in a plater capsule for combustion and volatilization to determine carbon and nitrogen. Compounds were analyzed using a mass spectrometer (Finnigan Delta Plus) for elemental carbon and nitrogen (Carlo Erba 1110). The carbon and nitrogen concentrations were expressed in percentage, and δ13C or δ14N was represented by the thousandths of the standard. The isotopic calculation was performed according to Equation 1, in which R represents the isotopic ratio 13C/12C or 15N/14N of the sample and the standard.

Protein content was determined based on the total nitrogen content, using a factor of 6.25 for soybean total protein (Mariotti et al., 2008).

2.5. Experimental Data Analysis

Data were analyzed separately for the two experiments with combinations of temperature and drought with eCO2. Treatments conducted on the same collection date were compared using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test (p-value < 0.05). Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to compare differences between the means for the main factors. The analysis was performed using R version 4.4.3 (Team, 2024). The analysis with R and Python script are given with in Supplementary materials 2.

2.6. Experimental Data Used in Models and Data Pre-Processing

The total dry biomass at 60 DAE (

Table S1), was used as input for model evaluation, encompassing soybean grain production, non-structural carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and carbon/nitrogen responses to different treatments at 125 DAE were used to validate the modeling. Scenarios were formulated to analyze the effects of individual factors and combined effects among aCO

2, eCO

2, Temp, and Drought. Categorical variable preprocessing involved encoding attributes such as aCO

2, eCO

2, Temp, eCO

2+Temp, Drought, and eCO

2+Drought. This process involved creating binary dummy variables, where each data entry was assigned a value of one for the corresponding dummy variable, while all other variables were set to zero. Furthermore, to ensure data balance and maintain a consistent sample number across all treatments, random sampling of aCO

2 and eCO

2 data was conducted, resulting in all samples containing n = 10 for each treatment.

Modeling grain production and quality data was verified according to linearity, normality, and homoscedasticity of variance of the measured parameters and predictor response variables. To estimate soybean production and quality under isolated and combined eCO2, temperature, and drought conditions. A Spearman correlation analysis was also performed to identify relationships among variables modeled (De Winter et al., 2016).

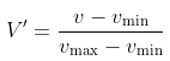

In a machine model approach with training data, all data were curated and standardized. Continuous variables were conducted using the min-max normalization technique to transform all input features into the [0, 1] range. This transformation was applied according to the following equation (2):

where v represents the original value of the feature, V' is the normalized value, and vmin and vmax denote the minimum and maximum values of the feature, respectively.

This method ensures that the smallest and largest values of each feature are mapped to 0 and 1, respectively. Categorical treatment variables were encoded using one-hot encoding. The dataset was randomly partitioned into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets, ensuring stratification across treatments.

2.7. Generalized Linear Model (GLM)

Generalized linear models provide a flexible approach to modeling relationships between predictors and various types of dependent variables. While conventional linear regression assumes normally distributed response variables, GLMs accommodate variables following various distributions, including gamma distributions, as shown in Equation 3 (Nelder & Wedderburn, 1972).

where y represents the transformation of the expectation of the dependent variable. The g is the link function, which connects the mean of the response variable to a linear combination of the predictors. β0 is the model intercept, and β1 through β5 are the coefficients associated with the interaction term between total biomass per treatment.

Production and quality responses in grain related to the influence of eCO

2, temperature, and drought were evaluated using model predictions, which involved calculating the percentage change relative to the baseline aCO

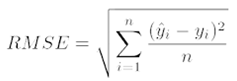

2. The model performance was evaluated by comparing the simulated and experimental data using the root mean square error (RMSE) (Loague & Green, 1991) with Equation 4:

where n is the number of treatments, ŷi represents the estimate of the ith treatment, and yi represents the ith observed value.

To investigate the relationships between eCO

2, Temp, and Drought, it was employed a path analysis-based approach, with modifications, as described by (Streiner, 2005). A model using generalized linear regression (GLM) was employed to account for potential deviations from normality in the data. The independent variables were eCO

2, Temp, and Drought treatment, while the dependent variables were soybean production and quality. To ensure comparability between variables with different scales and units of measurement, the data were standardized using the z-score (Altman, 1983). Z-score standardization was applied to each variable individually, according to the following, with Equation 5:

where x represents the original value of the variable, μ is the mean, and σ is the standard deviation. This procedure transforms the data so that each variable has a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. The standardization was performed using the R programming language (Team, 2024) through the “scale” function from the “dplyr” package (Wickham, 2025).

2.8. Machine Learning Modeling with XGBoost and CatBoost

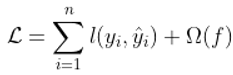

To develop the soybean production and quality grain prediction model, it was selected the Extreme Gradient Boosting algorithm (XGBoost) (Chen & Guestrin, 2016; Y. Li et al., 2023) and CatBoost (a gradient-boosting algorithm, similar to the XGBoost Regressor with key distinctions that enhance its performance and generalization ability) (Nishat et al., 2025). The function used by CatBoost, shown in Equation 6, follows a similar formulation to those adopted in XGBoost (Nishat et al., 2025).

where l is a loss function measuring the discrepancy between the predicted (ŷ) and observed values at 125 DAE (y), and Ω(f) is a regularization term that penalizes model complexity. To optimize the performance of XGBoost, a systematic hyperparameter was conducted, including learning rate, maximum tree depth, number of estimators, and minimum child weight for XGBoost. For CatBoost, the following parameters were used: iterations, depth, learning rate, and l2_leaf_reg (

Table S2) (Chen & Guestrin, 2016; Prokhorenkova et al., 2018). A randomized search strategy was employed over predefined parameter grids. Five-fold cross-validation ensured robust evaluation during hyperparameter tuning, while early stopping was applied to prevent overfitting (Kohavi & others, 1995; Prechelt, 2002). Model performance was assessed using evaluation metrics appropriate to the task, such as RMSE (Loague & Green, 1991).

3. Results

3.1. Microclimatic Data

The average temperature inside the OTCs in the aCO₂ and eCO

2 treatments was between 25–26°C, with relative humidity ranging from 68–71%. In the high temperature treatment, the average temperature was 29°C with a relative humidity of 57%. In the drought experiment, the average temperature was 24°C, and relative humidity ranged from 59% to 78% (

Figure S2).

3.2. Soybean Grain Production and Quality in Isolated and Combined Factors: Elevated CO2, Temperature, and Drought

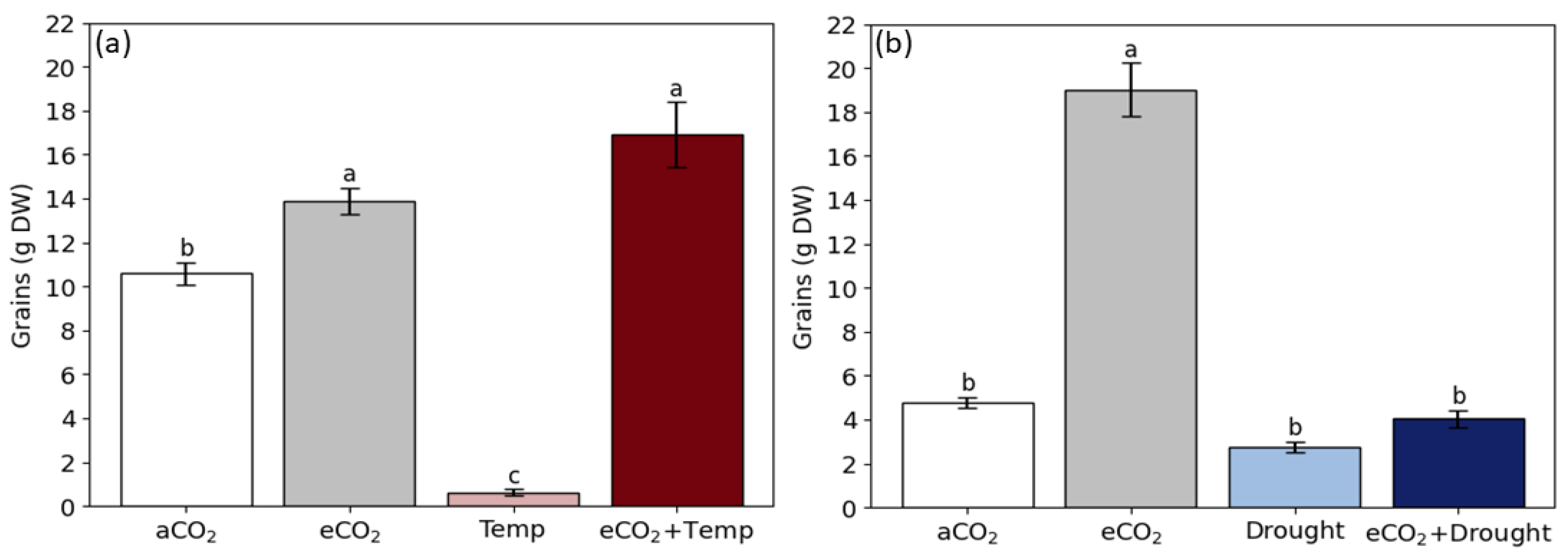

Grain production was consistently higher under eCO2 conditions compared to aCO₂. Grain biomass in eCO

2 treatments reached approximately 13.9 and 19.02 g, exceeding the values observed in aCO₂ treatments (10.6 and 4.79 g, respectively) (

Figure 1a, 1b). Variations in soybean production under ambient conditions were attributed to differences in sunlight exposure. Drought treatments experienced greater light incidence compared to temperature experiments (inside the greenhouse). Despite these differences, the overall trend of enhanced grain production under eCO

2 was consistent across both experimental conditions. High temperatures were associated with grain abortion and 91% reduction of grain biomass (0.63 g), whereas the combination of eCO

2+Temp led to a 59% increase (16.9 g) compared to aCO

2 (

Figure 1a).

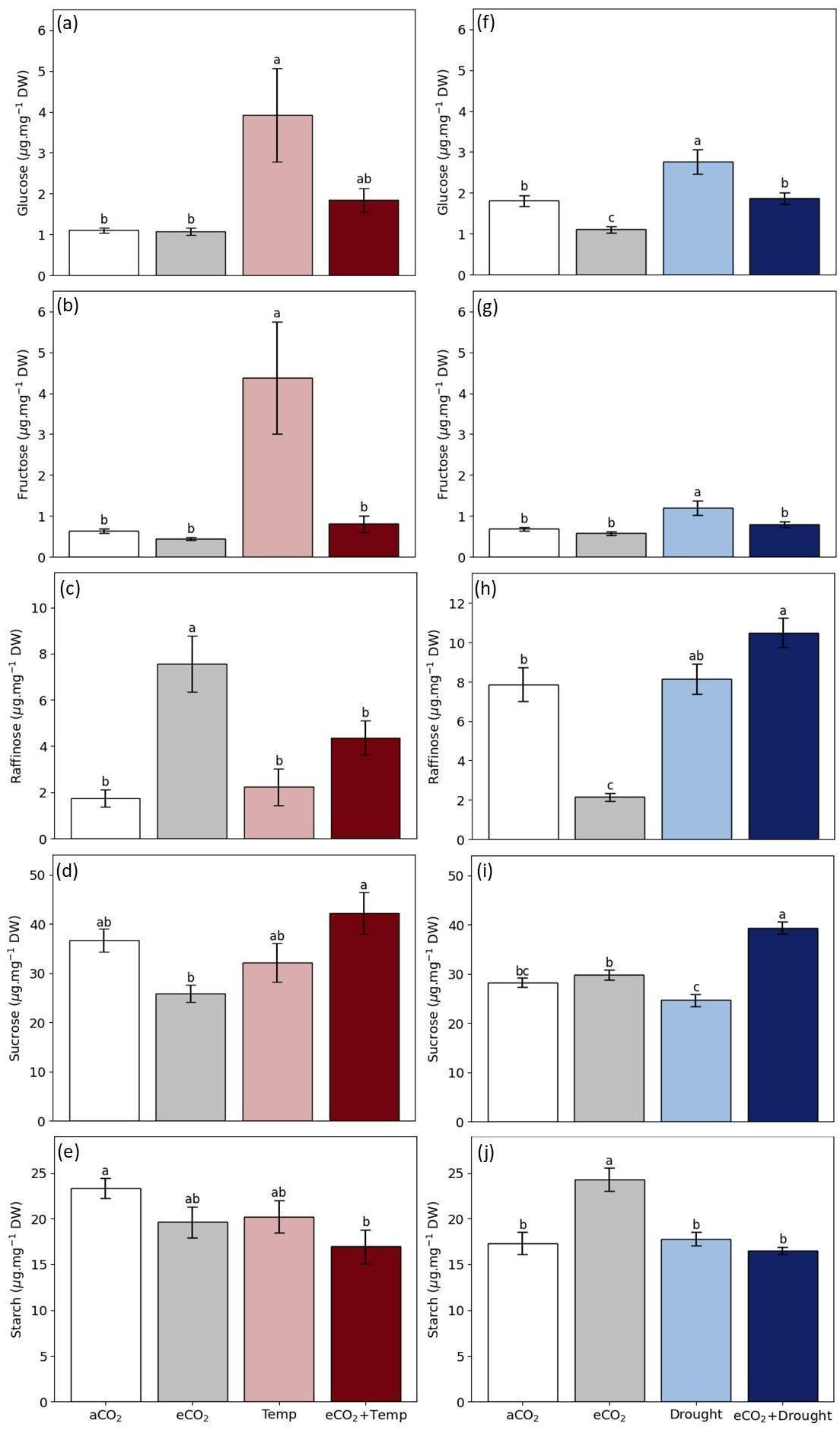

High temperature significantly increased the concentration of soluble sugars, with glucose and fructose levels rising by 4 folds, respectively, compared to aCO₂ (Figures 2a, 2b). Under eCO

2, raffinose concentrations increased by 335%, reaching 7.57 μg·mg⁻¹ compared to aCO₂ treatments (1.74 μg·mg⁻¹) (

Figure 2c). In contrast, sucrose levels did not show changes compared with ambient (

Figure 2d). Consequently, eCO

2 and eCO

2+Temp treatments result in greater grain biomass (

Figure 1a), potentially producing higher sugar concentrations than aCO₂ or Temp treatments alone (

Figure 2).

Drought conditions increased 52% glucose (2.76 μg.mg-1) and 76%, fructose (1.20 μg.mg-1) compared with aCO

2 (

Figure 2f,g). The lowest raffinose value in eCO

2 (2.14 μg.mg-1) compared with other treatments, Drought (8.14 μg.mg-1), and eCO

2+Drought (10.5 μg.mg-1), and aCO

2 (7.86 μg.mg-1) (

Figure 2h). Raffinose is a trisaccharide composed of galactose, glucose, and fructose, common in the Leguminosae family, and is important to carbohydrates in these grains. The sucrose increased by 39% only in eCO

2+Drought (39.34 μg.mg-1) (

Figure 2i), while starch concentrations were higher under eCO

2 (24.24 μg·mg⁻¹) compared to ambient treatments (16.47 μg·mg⁻¹) (

Figure 2j).

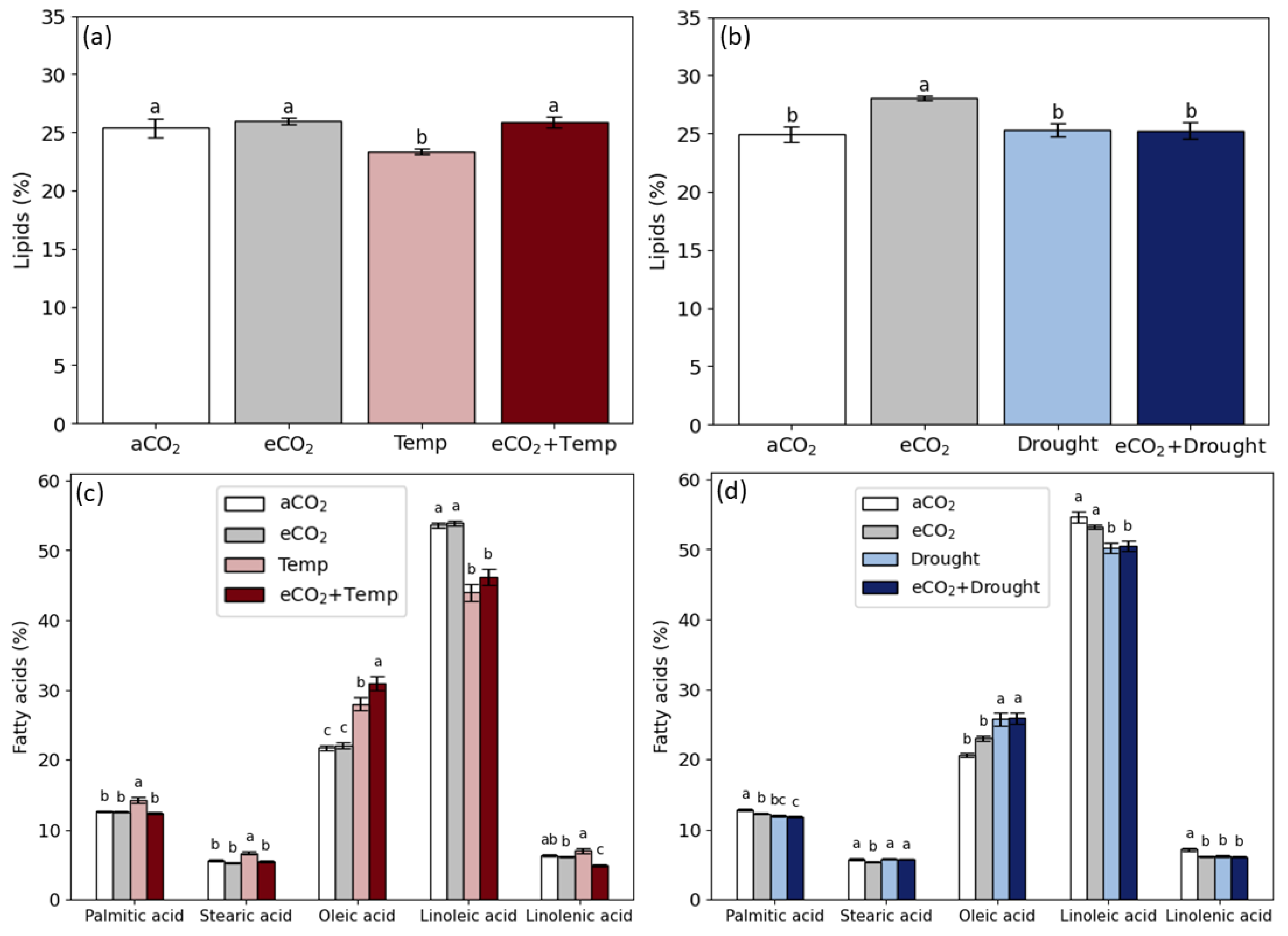

Another important component of soybean grains is lipid, which showed no differences between treatments (

Figure 3a,b). However, fatty acid composition varied, with a higher proportion of unsaturated fatty acid chains observed under aCO₂ and eCO

2 compared to stress conditions such as elevated temperature and drought (

Figure 3c,d). The fatty acid composition serves as a critical indicator of oil quality and reflects the seed's developmental stage. During grain development under high-temperature conditions, the proportions of palmitic, stearic, and oleic acid increased by 14%, 7% and 28%, respectively (

Figure 3c).

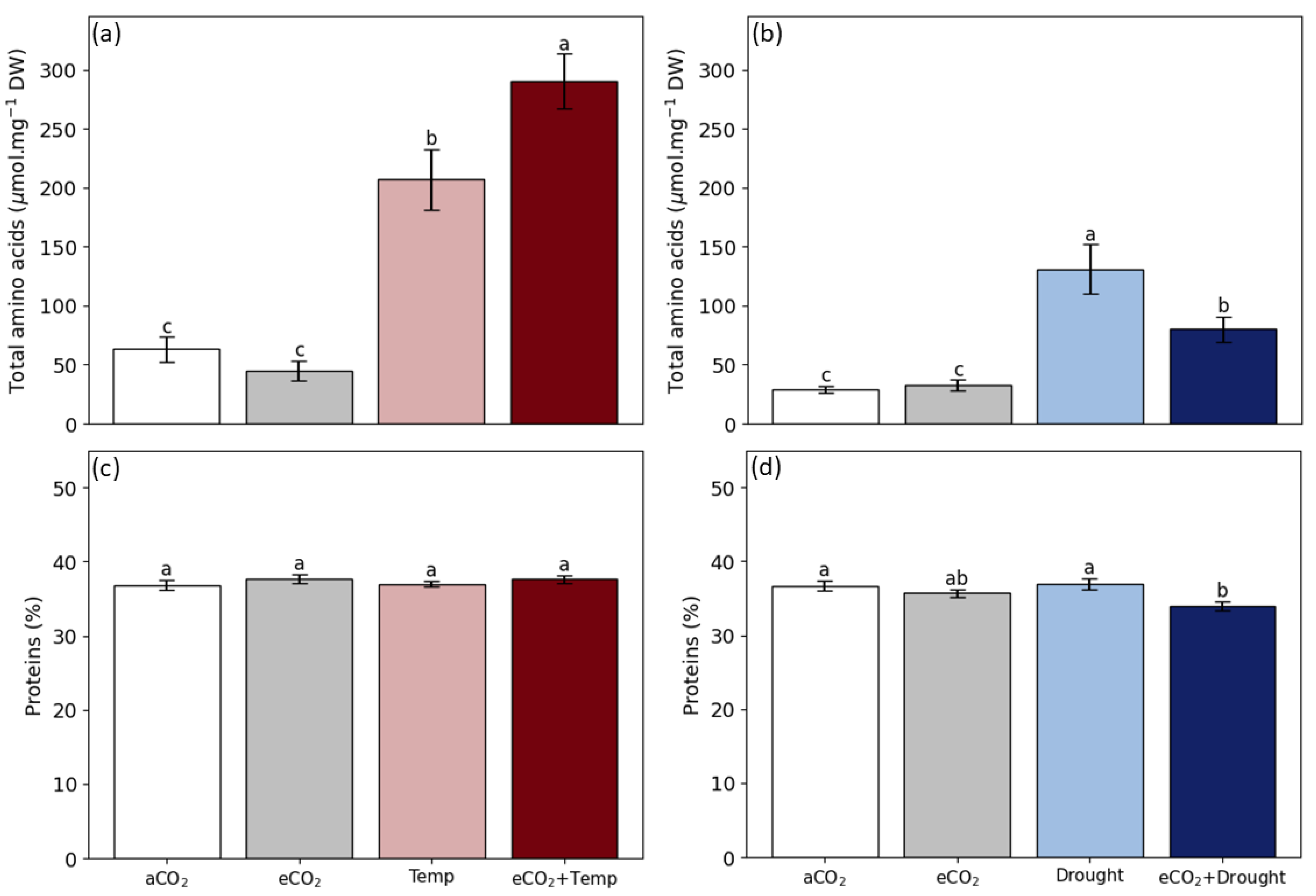

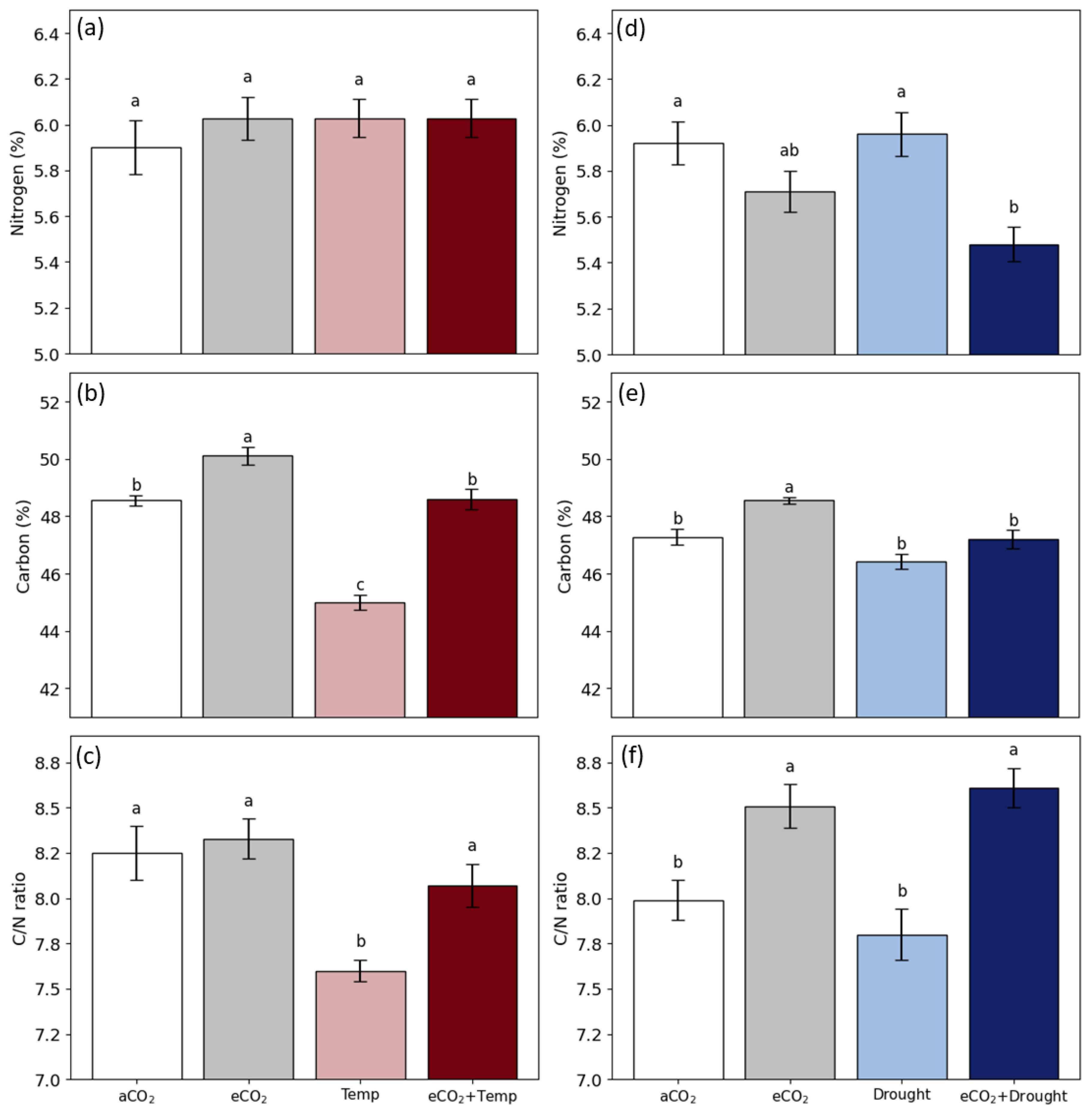

Temperature and drought, isolated or combined with eCO

2, increased total amino acid content (

Figure 4a, b). The highest value (5 folds more than aCO

2) was observed in the eCO

2+Temp, followed by Temp (4 folds) (

Figure 4a), Drought (3 folds more), and eCO

2+Drought (2 folds more) (

Figure 4b). However, there were no differences in nitrogen (

Figure 5a) and consequently in total protein content between the treatments (

Figure 4c,d). Regarding carbon percentage, the highest values were found in the eCO

2 treatment, reaching 48-50% (

Figure 5b,e). Furthermore, Temp treatments showed a reduction in carbon and C/N compared with the respective aCO

2 (

Figure 5c).

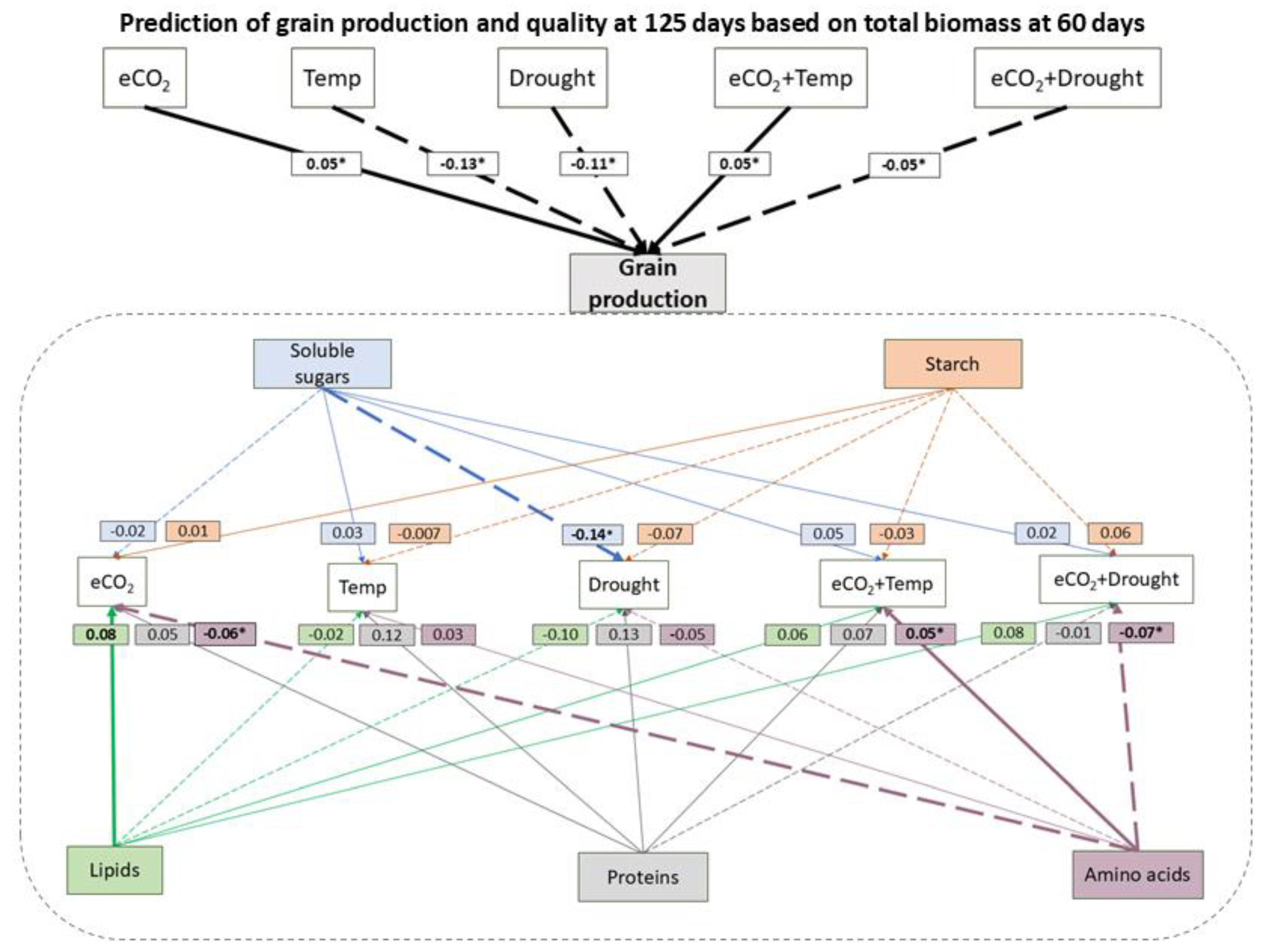

3.3. Modeling Using Experimental Data at 60 Days to Predict Grain Production and Quality at 125 Days

To predict soybean grain production and quality 125 DAE, total biomass data was obtained at 60 DAE, considering each experimental treatment condition. Generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to predict grain biochemical traits under different climate change scenarios. Across all variables analyzed — production, soluble sugars, starch, lipids, proteins, and amino acids — the models showed a good fit between observed and predicted values, with relatively low root mean square errors (RMSE). For grain production, the highest observed increase occurred under eCO

2, reaching 16.9 g ± 1.01, which was closely predicted by the model (16.56 g ± 0.79; RMSE = 3.85) (

Table 1). In contrast, drought led to substantial production and quality grain reductions across all traits (

Table 1). Soluble sugar content was particularly increased under combined eCO

2 and temperature stress (49.23 μg·mg⁻¹ ± 3.77), though predictions slightly underestimated observations (48.05 μg·mg⁻¹ ± 2.68; RMSE = 13.32) (

Table 1). Amino acid concentrations showed the most pronounced response to environmental drivers, with levels tripling under eCO

2+Temp (290.42 μmol.mg⁻¹ ± 23.23), yet the model slightly underestimated values (278.09 μmol.mg⁻¹ ± 15.54; RMSE = 85.59) (

Table 1). Prediction led to marked declines in amino acid drought and eCO

2+Drought (

Table 1).

Path diagrams are powerful tools for visualizing and quantifying direct and indirect relationships between variables (Hallgren et al., 2019). In this context, we used to show how different environmental treatments (e.g., eCO

2, Temp, Drought, eCO

2+Temp, and eCO

2+Drought) influence the production and quality parameters of soybean grains. The lines connecting variables represent the direct effects. The numbers associated with these lines are beta coefficients (β), which quantify the strength and direction of the relationship. A positive β indicates a positive correlation (as one variable increases, the other also tends to increase), while a negative β indicates a negative correlation (as one variable increases, the other tends to decrease). The bolding of lines and numbers within the diagram indicates statistically significant results. This significance is determined by p-values, which are presented in Table 2. Solid lines generally represent positive effects, while dashed lines represent negative effects. Our analysis reveals that total biomass at 60 days significantly predicts grain production at 125 days across all tested environmental conditions (eCO

2, Temp, Drought, eCO

2+Temp, eCO

2+Drought). The results showed that treatments were influenced by grain production, where the eCO

2 and eCO

2+Temp had positive effects, while Temp, Drought, and eCO

2+Drought showed a negative relation to grain production (

Figure 6; Table 2). Total soluble sugars showed significant positive direct effects under the treatment with Drought (β = -0.14) (

Figure 6; Table 2). Lipid content was positively related exclusively by the eCO

2 (β = 0.08), suggesting an increase in lipid (

Figure 6; Table 2). Amino acids showed a significant response that is positive in eCO

2+Temp (β = 0.05), and negative in eCO

2+Drought (β = -0.07) and eCO2 (β = -0.06) (

Figure 6; Table 2).

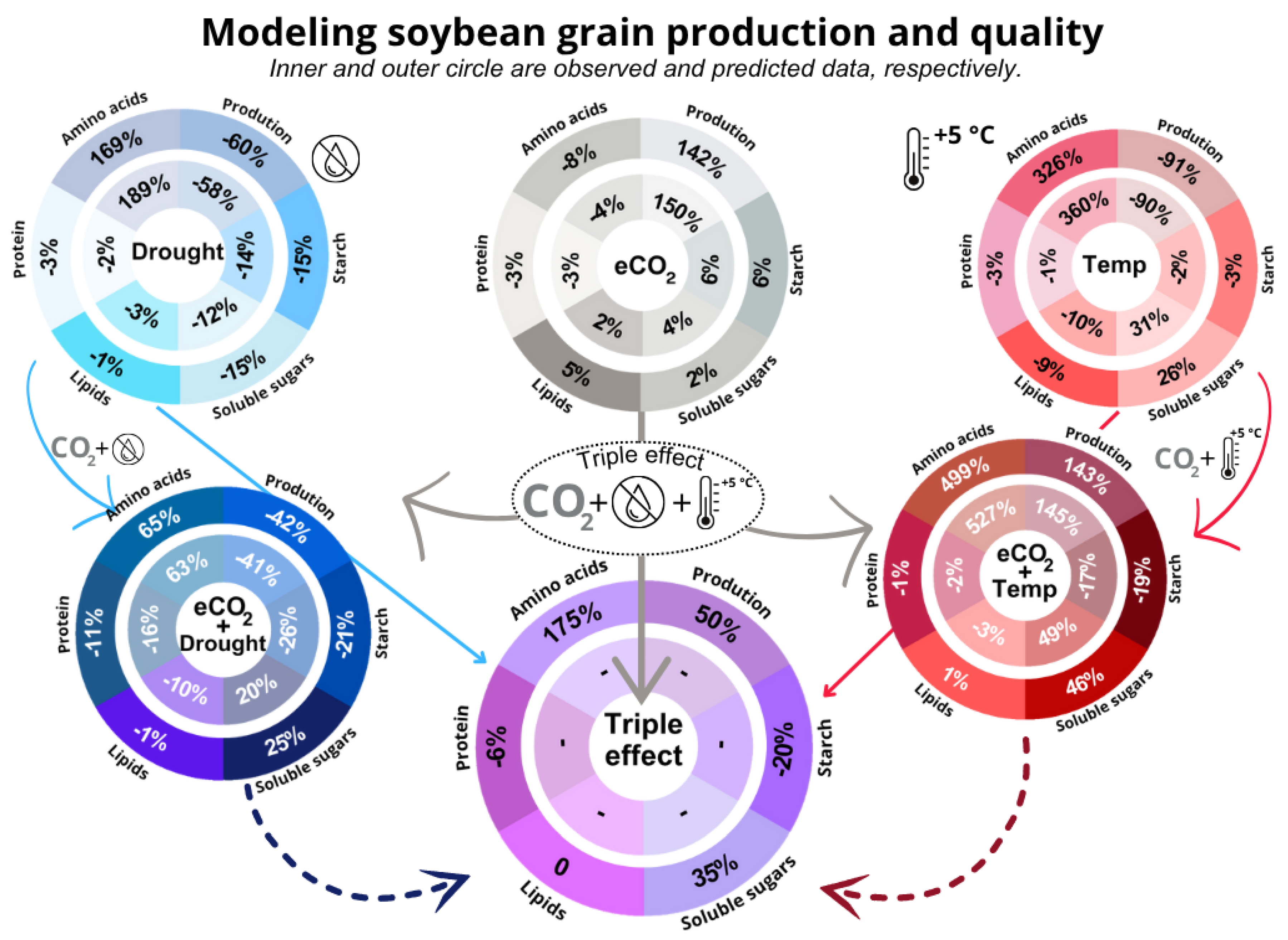

3.4. Machine Learning to Predict Grain Production in Climate Change Triple Effect

Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of the performance of two modeling approaches, XGBoost and CatBoost, in predicting soybean grain production and quality under the Triple Effect. The results indicate that the XGBoost model presented the best overall performance, both in estimating soybean grain production and quality (Table 3), considering 125 DAE data. XGBoost achieved the lowest root mean square error (RMSE = 0.04) for grain production, followed by CatBoost (RMSE = 1.50) (Table 3). To grain quality estimation under the same combined treatment, XGBoost consistently demonstrated a greater capacity to capture these complex interactions, reflecting its robustness and adaptability in simulating plant responses under Triple Effect conditions with lower RMSE (see Table 3). Compared with ambient observed results, Triple Effect soybean grain production increased by 50%, accompanied by a 35% rise in soluble sugars and a 175% increase in amino acid content. In contrast, starch and protein contents declined by 20% and 6%, respectively, while lipid levels remained unchanged (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

The interaction between elevated CO₂, high temperature, and drought are a challenge for understanding plant responses under future climate scenarios (Jin et al., 2017). By combining experimental data with predictive modeling, our study disentangles the interactive, additive, or antagonistic effects of these stressors on biomass, physiological traits, and grain quality. This integrative approach strengthens data interpretation and model validation (Qiao et al., 2019; X. Wu et al., 2018).

While models simulate crop growth based on weather, site, and management conditions, many still lack key factors, such as nutrient availability (Nendel et al., 2023). The findings here indicate that eCO2 enhances carbohydrate production. Increases in soluble sugars and amino acids reflect metabolic adjustments and stress signaling (Palacios et al., 2019; Zinta et al., 2018).

We modeled the individual and combined effects of eCO

2, Temp, and Drought, including Double Effect (eCO

2+Temp, eCO

2+Drought) and Triple Effect (eCO

2+Temp+Drought), to reveal distinct physiological and biochemical responses. GLM was applied to individual and dual treatments, while XGBoost effectively captured complex interactions in the Triple Effect, offering an integrated view of potential climate impacts on production and grain quality (

Figure 7).

4.1. Anticipating Crop Responses Under Climate Change

Modeling grain production and quality using early-stage experimental data provides a powerful approach to anticipate crop responses to climate change. Several studies highlight the importance of correlating early vegetative traits to final yield components to improve forecasting accuracy and reduce the need for long-term measurements (Van Eeuwijk et al., 2019). GLMs were applied using total biomass data collected at 60 DAE to predict grain production and biochemical traits at 125 DAE. This approach was effective, demonstrating that early stages vegetative responses can be strong predictors of later grain outcomes, particularly under multifactorial climate stress. Across all evaluated traits — grain production, soluble sugars, starch, lipids, proteins, and amino acids — the models showed good fit between observed and predicted values, with relatively low RMSE (

Table 1). These results align with previous studies, which have shown that statistical models based on early biomass or physiological indicators that can provide biologically meaningful estimations for predicting crop productivity and nutritional quality under abiotic stress (Chenu et al., 2017). Grain production under eCO

2 showed observed value (16.9 g ± 1.01), which the model predicted (16.56 g ± 0.79; RMSE = 3.85) (

Table 1), indicating the predictive of early biomass indicators, especially under carbon-enriched conditions.

Amino acid levels were 6-folds more under eCO

2+Temp than ambient (

Table 1). Nevertheless, the model captured the trend of increasing amino acid concentrations under eCO

2+Temp (

Table 1). This finding is consistent with those of Zinta et al. (2018), who reported that combined climate stressors modulate amino acid metabolism as part of an adaptive mechanism to maintain osmotic balance and metabolic flexibility. Overall, this modeling strategy supports the use of early physiological data to predict production and quality grain. Facilitating the development of climate-resilient crops and prediction of possible crop loss (Banga & Kang, 2014; Khan et al., 2022). It also underscores the utility of GLMs in integrating multiple variables and stress treatments to inform adaptive breeding and agronomic strategies under projected climate scenarios.

4.2. Validation Model with Out-of-Data Experiment

Model-based projections from GLM reveal differential impacts of eCO

2, temperature, drought, and their interactions on soybean (

Table 1). The model captured a trend of increased production under eCO

2, with predicted values (16.52 g ± 0.96) aligning with observations (14.67 g ± 0.39) (

Table S3). Starch predictions were also consistent with aCO

2 (11.27 µg.mg.-1 ± 0.87 predicted vs 11.54 µg.mg.-1 ± 0.93 observed) and eCO

2 (16.52 µg.mg.-1 ± 0.96 predicted vs 14.67 µg.mg.-1 ± 0.39 observed). However, under combined eCO

2+Temp, the model overestimated production (20.58 µg.mg.-1 ± 1.76 predicted vs. 10.04 µg.mg.-1 ± 1.26 observed) and failed to predict the drop in soluble sugars (15.68 µg.mg.-1 ± 0.30 predicted vs. 2.95 µg.mg.-1 ± 0.54 observed) (

Table S3). The observed inconsistencies, particularly the overestimation of protein content and the unexpected positive feedback in starch biosynthesis under dual stress, suggest possible overfitting and limitations in model assumptions related to source–sink dynamics and the complex C/N partitioning. These issues may stem from the restricted size and scope of the dataset, which may not capture the full variability of genotypes, developmental stages, and environmental conditions. Expanding the dataset to include a broader and more representative range of observations could enhance model realism and generalizability. Meta-analytical approaches that aggregate data across sites, years, and experimental setups may also improve the parameterization of key physiological processes. Moreover, integrating mechanistic insights from transcriptomic or metabolomic data could help constrain the model, reduce overfitting, and better reflect the complexity of plant responses under combined stressors (Y. Wang et al., 2024). This integrated approach, which combines experimental measurements with modeling, provides a robust framework for data integration, model validation, and enhanced analysis, as highlighted by previous research (Qiao et al., 2019; X. Wu et al., 2018; Y. Wu et al., 2019). Modeling is an invaluable tool for assessing environmental shifts and variations in grain production, aiding in the development of adaptive strategies for future climate scenarios (N. Wang et al., 2018). The intricate interactions among eCO

2 increased temperature, and drought present a significant challenge for accurately predicting crop responses under future climate conditions (Jin et al., 2017).

Model simulations need additional factors, such as physiological and biochemical characteristics - nutrient availability, plant susceptibility, and quality parameters - beyond the weather and management practices (Nendel et al., 2023). The integration of experimental data and predictive modeling provides valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying abiotic interactions. For instance, this model suggests that eCO2 enhances carbohydrate production and nitrogen content, although these effects are restricted by high temperature and drought. Furthermore, the accumulation of soluble sugars and amino acids highlights the role of stress signaling pathways and metabolic flexibility in mediating plant responses to combined stressors (Heinemann & Hildebrandt, 2021; Palacios et al., 2019; Zinta et al., 2018).

4.3. Elevated CO2 Promotes the Benefits of Grain Production and Changes Grain Quality

Elevated CO₂ enhances photosynthetic rates, improves water-use efficiency (WUE), and drives increased growth and yield in crops, like soybean (DaMatta et al., 2010; Digrado et al., 2024; Shanker et al., 2022). Soybean production, in particular, benefit from these physiological shifts, with evidence showing an increase in grain oil concentration under eCO

2 (

Figure 7). However, eCO

2 effects on soluble sugars, protein content, and nitrogen metabolism revealed complex trade-offs in seed composition and growth (Figures 3, 4, and 5).

Protein levels in soybean seeds exhibited inconsistent responses, with some studies reporting a modest 1.5% increase (Digrado et al., 2024), while others observed no significant change (Palacios et al., 2019). These findings suggest that the impact of eCO

2 on protein content may be context-dependent, potentially influenced by environmental conditions, nitrogen availability, cultivar differences, or even ontogenetic deviation during grain filling. Furthermore, eCO

2 generally shifts grain composition towards higher carbohydrate and reduced protein content (

Figure 7), lowering the metabolic costs of growth and reducing maintenance requirements (Boote et al., 1997), and increase the production.

4.4. Temperature and Drought Reduce Grain Production

Rising global temperatures and drought, pose a significant threat to agricultural productivity, particularly impacting soybean grain production (Long, 2025). High temperatures accelerate plant development, reduce pollen viability, and decrease grain set, collectively resulting in significant production losses in crops such as soybean (Müller & Rieu, 2016), which was observed in the present study, with a 91% reduction in grain biomass (

Figure 7). Drought significantly reduces soybean production, with its negative impacts being more pronounced under ambient CO₂ conditions compared to eCO₂ (Ferris et al., 1999; Gray et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2017, 2018; Singh et al., 2021). The observed 60% reduction in grain production under drought (

Figure 7) aligns with prior studies showing declines grain biomass under water stress (A. Wang et al., 2018). Under drought conditions combined with eCO

2, the reduction was mitigated to 42% (

Figure 7). This suggests that improved water-use efficiency under eCO

2 may provide partial mitigation of drought-induced yield losses (Singh et al., 2021).

4.5. Temperature Coupled to Elevated CO2, Promotes Grain Biomass

There are compensatory interactions between eCO

2+Temp on soybean grain biomass and quality (

Figure 7). The beneficial effects of eCO

2 in high temperature stress are primarily attributed to increased photosynthetic activity, enhanced water-use efficiency, and shifts in carbohydrate partitioning (Habermann et al., 2019; Haworth et al., 2021). Our model predicts that eCO

2+Temp stress could improve grain production by a substantial increase of 143% relative to ambient conditions, closely matching the observed increase of 145% (

Figure 7). This result highlights its potential to partially offset high temperature losses, particularly under moderate temperature increases (Ainsworth & Long, 2021; Gray et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2021). Our study also revealed the significant impact of eCO

2+Temp on the carbohydrate profiles of grains, reflecting metabolic adjustments during development can disrupt carbon partitioning and increase respiration, leading to reduced seed carbohydrate content and overall yield (Yang et al., 2023).

4.6. Triple Effect May Increase Grain Production, but Decrease Quality

Throughout, it is well-established that elevated CO₂ generally enhances production, and that temperature or drought tends to inhibit it. However, the interaction between these variables during key reproductive phases remains less understood, particularly regarding the quality of soybean production (Thomey et al., 2019). Triple Effect induces nuanced changes in soybean production and quality components, with agronomic implications. XGBoost demonstrated superior predictive performance in simulating soybean grain production and quality under the Triple Effect compared to CatBoost, with markedly lower RMSE (0.04 vs. 1.50) (Table 3). This aligns with global agricultural research showing that XGBoost often outperforms or matches neural networks in complex agronomic prediction (Bhat et al., 2024; Huber et al., 2022; M’hamdi et al., 2024; Taniushkina et al., 2024). The 50% increase in grain production under combined climate treatments is striking and suggests that our models captured a strong compensatory effect from elevated CO₂ (

Figure 7).

Quality changes in grain showed a 35% rise in soluble sugars and 175% increase in amino acids, paired with a 20% decline in starch and 6% in protein, reflecting plant metabolic adjustment under stress (

Figure 7). High amino acid levels are typically used as osmotic regulators and indicators of stress. While this may contribute to stress tolerance, it also reflects a metabolic shift that prioritizes immediate stress mitigation over long-term storage or structural compounds, such as proteins and starch (Song et al., 2025). The rapid and precise estimation of production and quality shifts under projected climate extremes offers valuable guidance for breeding, agronomic management, and policy adaptation. The metabolic insights reveal vulnerabilities in nutritional quality that could impact feed and food systems, data critical for developing climate-resilient cultivars.

These findings have important implications for climate-resilient agriculture. The increase in grain production under the Triple Effect demonstrates the potential for elevated CO₂ to mitigate some of the negative impacts of temperature and drought. However, the concurrent reductions in starch raise concerns about the nutritional quality of soybean grains under future climate scenarios. This trade-off between production and quality underscores the need for breeding programs that prioritize not only productivity but also the resilience of grain composition to environmental stressors.

5. Conclusions

This study addressed two objectives with implications for climate-resilient agriculture. First, we demonstrated that GLMs leveraging early-stage physiological and morphological traits, specifically total biomass at 60 DAE, can forecast soybean grain production and quality at 125 DAE across environmental conditions. The low prediction errors and consistent directional trends between observed and estimated values support the use of GLMs as reliable tools for anticipating crop responses, especially under single and dual climate stressors. This reinforces the utility of early-stage biomass as a predictive indicator for guiding agronomic interventions and breeding strategies. Second, we modeled the combined effects of elevated CO₂, high temperature, and drought (Triple Effect) on soybean grain production and quality. By integrating experimental datasets from double-factor treatments and applying machine learning techniques, we found that XGBoost outperformed CatBoost in predictive accuracy, effectively capturing the complex nonlinear interactions among stressors. Under the Triple Effect, model projections revealed a substantial increase in grain production (+50%) and specific quality components such as soluble sugars (+35%) and amino acids (+175%), alongside reductions in starch (−20%) and proteins (−6%). These findings highlight the dual nature of climate impacts: potential gains in yield mediated by elevated CO₂ may come at the cost of nutritional quality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Figure S1: Experimental design of temperature and drought experiments in Open Top Chambers; Figure S2: Meteorological conditions during the soybean experiment. Table S1: Soybean total biomass (g DW) within 60 days after the experiment across various treatment conditions. Table S2: Hyperparameter ranges used for tuning the XGBoost and CatBoost models. Table S3: Comparison between observed data and predicted values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AG, JSF, MSB; Experiment designed: AG, CEJP, EQPT, LPO; Data curation: AG, JSF, CEJP, CMR; Methodology: AG, CEJP, CMR, DP, JSF, LPO, LFO, PBC; Modeling analyses: AG, CMR, DP, JSF, MSB; Writing – original draft: AG, DP, JSF, MSB; Review and editing: AG, DP, CEJP, CMR, EISF, JSF, LPO, MSB.

Funding

This work has been partly financed by the National Institute of Science and Technology of Bioethanol (INCT- Bioethanol – FAPESP 2008/57908-6 and CNPq 574002/2008-1). JSF is financed by the FAPESP (2022/14886-0). LFO (RCGI 371055 and FAPESP 2024/12357-5). AG and MSB are fellow researchers of CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, Brazil).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data and scripts generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank CAPES for the fellowships granted and Dr. Vanoli Fronza, a researcher at the Embrapa Soybean Division (Londrina, PR), for providing the seeds of the cultivars used.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ainsworth, E. A. , & Lemonnier, P. (2018). Phloem function: A key to understanding and manipulating plant responses to rising atmospheric [CO2]? Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 43, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E. A. , & Long, S. P. (2021). 30 years of free-air carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE): What have we learned about future crop productivity and its potential for adaptation? Global Change Biology, 27(1), 27–49.

- Altman, E. I. (1983). Why businesses fail. Journal of Business Strategy, 3(4), 15–21.

- Amaral, L. I. V. do, Gaspar, M., Costa, P. M. F., Aidar, M. P. M., & Buckeridge, M. S. (2007). Novo método enzimático rápido e sensível de extração e dosagem de amido em materiais vegetais. Hoehnea, 34, 425–431.

- ANEC. (2022). Associação Nacional dos Exportadores de Cereais. In Https://anec.com.br/.

- Arenque, B. C., Grandis, A., Pocius, O., de Souza, A. P., & Buckeridge, M. S. (2014). Responses of Senna reticulata, a legume tree from the Amazonian floodplains, to elevated atmospheric CO 2 concentration and waterlogging. Trees, 28, 1021–1034.

- Assad, E. D. , Oliveira, A. F. de, Nakai, A. M., Pavão, E., Pellegrino, G. Q., & Monteiro, J. (2016). Impactos e vulnerabilidades da agricultura brasileira às mudanças climáticas. In Modelagem Climática e Vulnerabilidades Setoriais à Mudança do Clima no Brasil (pp. 127–188). Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação.

- Banga, S. S. , & Kang, M. S. (2014). Developing climate-resilient crops. Journal of Crop Improvement, 28(1), 57–87.

- Beck, J. (2013). Predicting climate change effects on agriculture from ecological niche modeling: Who profits, who loses? Climatic Change, 116(2), 177–189.

- Beniston, M. , Stephenson, D. B., Christensen, O. B., Ferro, C. A. T., Frei, C., Goyette, S., Halsnaes, K., Holt, T., Jylhä, K., Koffi, B., Palutikof, J., Schöll, R., Semmler, T., & Woth, K. (2007). Future extreme events in European climate: An exploration of regional climate model projections. Climatic Change, 81(S1), 71–95. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S. A. , Qadri, S. A. A., Dubbey, V., Sofi, I. B., & Huang, N.-F. (2024). Impact of crop management practices on maize yield: Insights from farming in tropical regions and predictive modeling using machine learning. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 18, 101392.

- Boote, K. , Pickering, N., & Allen Jr, L. (1997). Plant modeling: Advances and gaps in our capability to predict future crop growth and yield in response to global climate change. Advances in Carbon Dioxide Effects Research, 179–228.

- Bui, Q.-T., Pham, Q.-T., Pham, V.-M., Tran, V.-T., Nguyen, D.-H., Nguyen, Q.-H., Nguyen, H.-D., Do, N. T., & Vu, V.-M. (2024). Hybrid machine learning models for aboveground biomass estimations. Ecological Informatics, 79, 102421.

- Cai, Y. , Chen, L., Zhang, Y., Yuan, S., Su, Q., Sun, S., Wu, C., Yao, W., Han, T., & Hou, W. (2020). Target base editing in soybean using a modified CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 18(10), 1996.

- Chen, T. , & Guestrin, C. (2016). Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. Proceedings of the 22nd Acm Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–794.

- Chenu, K., Porter, J. R., Martre, P., Basso, B., Chapman, S. C., Ewert, F., Bindi, M., & Asseng, S. (2017). Contribution of crop models to adaptation in wheat. Trends in Plant Science, 22(6), 472–490.

- Christie, W. W., & Hutton, J. (1993). Preparation of ester derivatives of fatty acids for chromatographic analysis. Advances in Lipid Methodology, 2(69), e111.

- CONAB. (2021). Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento.

- DaMatta, F. M., Grandis, A., Arenque, B. C., & Buckeridge, M. S. (2010). Impacts of climate changes on crop physiology and food quality. Food Research International, 43(7), 1814–1823.

- De Winter, J. C. , Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2016). Comparing the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: A tutorial using simulations and empirical data. Psychological Methods, 21(3), 273.

- Digrado, A., Montes, C. M., Baxter, I., & Ainsworth, E. A. (2024). Seed quality under elevated CO2 differs in soybean cultivars with contrasting yield responses. Global Change Biology, 30(2), e17170.

- FAO. (2023). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Crops. In Http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/visualize.

- Ferris, R., Wheeler, T., Ellis, R., & Hadley, P. (1999). Seed yield after environmental stress in soybean grown under elevated CO2. Crop Science, 39(3), 710–718.

- Fortirer, J. da S., Grandis, A., Pagliuso, D., Castanho, C. de T., & Buckeridge, M. S. (2023). Meta-analysis of the responses of tree and herb to elevated CO2 in Brazil. Scientific Reports, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z. , Niu, S., & Dukes, J. S. (2015). What have we learned from global change manipulative experiments in China? A meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 5(19), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Gourdji, S. M. , Sibley, A. M., & Lobell, D. B. (2013). Global crop exposure to critical high temperatures in the reproductive period: Historical trends and future projections. Environmental Research Letters, 8(2), 024041. [CrossRef]

- Gray, S. B., Dermody, O., Klein, S. P., Locke, A. M., Mcgrath, J. M., Paul, R. E., Rosenthal, D. M., Ruiz-Vera, U. M., Siebers, M. H., Strellner, R., & others. (2016). Intensifying drought eliminates the expected benefits of elevated carbon dioxide for soybean. Nature Plants, 2(9), 1–8.

- Habermann, E. , Dias de Oliveira, E. A., Contin, D. R., San Martin, J. A., Curtarelli, L., Gonzalez-Meler, M. A., & Martinez, C. A. (2019). Stomatal development and conductance of a tropical forage legume are regulated by elevated [CO2] under moderate warming. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 609.

- Hallgren, K. A. , McCabe, C. J., King, K. M., & Atkins, D. C. (2019). Beyond path diagrams: Enhancing applied structural equation modeling research through data visualization. Addictive Behaviors, 94, 74–82.

- Hancock, J. , & Khoshgoftaar, T. (2020). CatBoost for big data: An interdisciplinary review. J Big Data 7 (1): 94.

- Haworth, M. , Marino, G., Loreto, F., & Centritto, M. (2021). Integrating stomatal physiology and morphology: Evolution of stomatal control and development of future crops. Oecologia, 197(4), 867–883.

- Heinemann, B. , & Hildebrandt, T. M. (2021). The role of amino acid metabolism in signaling and metabolic adaptation to stress-induced energy deficiency in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany, 72(13), 4634–4645.

- Hoagland, K. D. , Rosowski, J. R., Gretz, M. R., & Roemer, S. C. (1993). Diatom extracellular polymeric substances: Function, fine structure, chemistry, and physiology. Journal of Phycology, 29(5), 537–566.

- Huber, F., Yushchenko, A., Stratmann, B., & Steinhage, V. (2022). Extreme Gradient Boosting for yield estimation compared with Deep Learning approaches. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 202, 107346.

- Jardim Amorim, D. , Pereira dos Santos, A. R., Nunes da Piedade, G., Quelvia de Faria, R., Amaral da Silva, E. A., & Pereira Sartori, M. M. (2021). The use of the generalized linear model to assess the speed and uniformity of germination of corn and soybean seeds. Agronomy, 11(3), 588.

- Jin, Z., Ainsworth, E. A., Leakey, A. D., & Lobell, D. B. (2018). Increasing drought and diminishing benefits of elevated carbon dioxide for soybean yields across the US Midwest. Global Change Biology, 24(2), e522–e533.

- Jin, Z. , Zhuang, Q., Wang, J., Archontoulis, S. V., Zobel, Z., & Kotamarthi, V. R. (2017). The combined and separate impacts of climate extremes on the current and future US rainfed maize and soybean production under elevated CO2. Global Change Biology, 23(7), 2687–2704. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. H. U. , Wang, S., Wang, J., Ahmar, S., Saeed, S., Khan, S. U., Xu, X., Chen, H., Bhat, J. A., & Feng, X. (2022). Applications of artificial intelligence in climate-resilient smart-crop breeding. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(19), 11156.

- Kohavi, R. & others. (1995). A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. Ijcai, 14(2), 1137–1145.

- Li, D., Liu, H., Qiao, Y., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., Dong, B., Shi, C., Liu, Y., Li, X., & Liu, M. (2013). Effects of elevated CO2 on the growth, seed yield, and water use efficiency of soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) under drought stress. Agricultural Water Management, 129, 105–112.

- Li, Y. , Zeng, H., Zhang, M., Wu, B., Zhao, Y., Yao, X., Cheng, T., Qin, X., & Wu, F. (2023). A county-level soybean yield prediction framework coupled with XGBoost and multidimensional feature engineering. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 118, 103269.

- Loague, K. , & Green, R. E. (1991). Statistical and graphical methods for evaluating solute transport models: Overview and application. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 7(1–2), 51–73.

- Long, S. P. (2025). Needs and opportunities to future-proof crops and the use of crop systems to mitigate atmospheric change. Philosophical Transactions B, 380(1927), 20240229.

- Manavalan, L. P. , Guttikonda, S. K., Tran, L.-S. P., & Nguyen, H. T. (2009). Physiological and Molecular Approaches to Improve Drought Resistance in Soybean. Plant and Cell Physiology, 50(7), 1260–1276. [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J. A. , Torres, R. R., & Alves, L. M. (2017). Drought in Northeast Brazil—Past, present, and future. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 129(3–4), 1189–1200. [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, F. , Tomé, D., & Mirand, P. P. (2008). Converting nitrogen into protein—Beyond 6.25 and Jones’ factors. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 48(2), 177–184.

- M’hamdi, O., Takács, S., Palotás, G., Ilahy, R., Helyes, L., & Pék, Z. (2024). A comparative analysis of XGBoost and neural network models for predicting some tomato fruit quality traits from environmental and meteorological data. Plants, 13(5), 746.

- Monteiro, L. A. , Ramos, R. M., Battisti, R., Soares, J. R., Oliveira, J. C., Figueiredo, G. K., Lamparelli, R. A., Nendel, C., & Lana, M. A. (2022). Potential use of data-driven models to estimate and predict soybean yields at national scale in Brazil. International Journal of Plant Production, 16(4), 691–703.

- Mourtzinis, S. , Specht, J. E., Lindsey, L. E., Wiebold, W. J., Ross, J., Nafziger, E. D., Kandel, H. J., Mueller, N., Devillez, P. L., Arriaga, F. J., & others. (2015). Climate-induced reduction in US-wide soybean yields underpinned by region-and in-season-specific responses. Nature Plants, 1(2), 1–4.

- Müller, F., & Rieu, I. (2016). Acclimation to high temperature during pollen development. Plant Reproduction, 29, 107–118.

- Nelder, J. A. , & Wedderburn, R. W. (1972). Generalized linear models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society, 135(3), 370–384.

- Nendel, C., Reckling, M., Debaeke, P., Schulz, S., Berg-Mohnicke, M., Constantin, J., Fronzek, S., Hoffmann, M., Jakšić, S., Kersebaum, K.-C., & others. (2023). Future area expansion outweighs increasing drought risk for soybean in Europe. Global Change Biology, 29(5), 1340–1358.

- Nishat, M. H. , Khan, M. H. R. B., Ahmed, T., Hossain, S. N., Ahsan, A., El-Sergany, M., Shafiquzzaman, M., Imteaz, M. A., & Alresheedi, M. T. (2025). Comparative analysis of machine learning models for predicting water quality index in Dhaka’s rivers of Bangladesh. Environmental Sciences Europe, 37(1), 31.

- Onat, B. , Bakal, H., Gulluoglu, L., & Arıoglu, H. (2017). The effects of high temperature at the growing period on yield and yield components of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr] varieties. Turkish Journal of Field Crops, 22(2), 178–186.

- Ortiz-Bobea, A., Ault, T. R., Carrillo, C. M., Chambers, R. G., & Lobell, D. B. (2021). Anthropogenic climate change has slowed global agricultural productivity growth. Nature Climate Change, 11(4), 306–312. [CrossRef]

- Pagliuso, D. , Grandis, A., Fortirer, J. S., Camargo, P., Floh, E. I. S., & Buckeridge, M. S. (2022). Duckweeds as Promising Food Feedstocks Globally. Agronomy, 12(4). [CrossRef]

- Palacios, C. , Grandis, A., Carvalho, V., Salatino, A., & Buckeridge, M. (2019). Isolated and combined effects of elevated CO2 and high temperature on the whole-plant biomass and the chemical composition of soybean seeds. Food Chemistry, 275, 610–617.

- Pasquel, D., Roux, S., Richetti, J., Cammarano, D., Tisseyre, B., & Taylor, J. A. (2022). A review of methods to evaluate crop model performance at multiple and changing spatial scales. Precision Agriculture, 23(4), 1489–1513.

- Poudel, S. , Vennam, R. R., Shrestha, A., Reddy, K. R., Wijewardane, N. K., Reddy, K. N., & Bheemanahalli, R. (2023). Resilience of soybean cultivars to drought stress during flowering and early-seed setting stages. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 1277.

- Prechelt, L. (2002). Early stopping-but when? In Neural Networks: Tricks of the trade (pp. 55–69). Springer.

- Prokhorenkova, L. , Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V., & Gulin, A. (2018). CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 31.

- Qiao, Y., Miao, S., Li, Q., Jin, J., Luo, X., & Tang, C. (2019). Elevated CO2 and temperature increase grain oil concentration but their impacts on grain yield differ between soybean and maize grown in a temperate region. Science of the Total Environment, 666, 405–413.

- Rezaei, E. E. , Webber, H., Gaiser, T., Naab, J., & Ewert, F. (2015, March). Heat stress in cereals: Mechanisms and modelling. In European Journal of Agronomy (Vol. 64, pp. 98–113). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Sentelhas, P. C. , Battisti, R., Câmara, G. M. de S., Farias, J., Hampf, A., & Nendel, C. (2015). The soybean yield gap in Brazil–magnitude, causes and possible solutions for sustainable production. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 153(8), 1394–1411.

- Shanker, A. K. , Gunnapaneni, D., Bhanu, D., Vanaja, M., Lakshmi, N. J., Yadav, S. K., Prabhakar, M., & Singh, V. K. (2022). Elevated CO2 and water stress in combination in plants: Brothers in arms or partners in crime? Biology, 11(9), 1330.

- Shastry, A., Sanjay, H., & Bhanusree, E. (2017). Prediction of crop yield using regression techniques. International Journal of Soft Computing, 12(2), 96–102.

- Singh, S. K., Reddy, V. R., Devi, M. J., & Timlin, D. J. (2021). Impact of water stress under ambient and elevated carbon dioxide across three temperature regimes on soybean canopy gas exchange and productivity. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 16511.

- Song, Y. , John Martin, J. J., Liu, X., Li, X., Hou, M., Zhang, R., Xu, W., Li, W., & Cao, H. (2025). Unraveling the response of secondary metabolites to cold tolerance in oil palm by integration of physiology and metabolomic analyses. BMC Plant Biology, 25(1), 279.

- SoyStats. (2023). 2018 Soy Highlights. http://soystats.com.

- Streck, N. A. (2005). Mudança climática e agroecossistemas: Efeito do aumento de CO2 atmosférico e temperatura sobre o crescimento, desenvolvimento e rendimento das culturas. Ciência Rural, 35, 730–740.

- Streiner, D. L. (2005). Finding our way: An introduction to path analysis. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 50(2), 115–122.

- Taniushkina, D., Lukashevich, A., Shevchenko, V., Belalov, I. S., Sotiriadi, N., Narozhnaia, V., Kovalev, K., Krenke, A., Lazarichev, N., Bulkin, A., & others. (2024). Case study on climate change effects and food security in Southeast Asia. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 16150.

- Team, R. C. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 4.4. 0). 4.3. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Thomey, M. L. , Slattery, R. A., Köhler, I. H., Bernacchi, C. J., & Ort, D. R. (2019). Yield response of field-grown soybean exposed to heat waves under current and elevated [CO2]. Global Change Biology, 25(12), 4352–4368.

- USDA. (2024). Cropexplorer [Dataset]. https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/cropexplorer/cropview/commodityView.aspx?cropid=2222000.

- Van Eeuwijk, F. A., Bustos-Korts, D., Millet, E. J., Boer, M. P., Kruijer, W., Thompson, A., Malosetti, M., Iwata, H., Quiroz, R., Kuppe, C., & others. (2019). Modelling strategies for assessing and increasing the effectiveness of new phenotyping techniques in plant breeding. Plant Science, 282, 23–39.

- Wang, A. , Lam, S. K., Hao, X., Li, F. Y., Zong, Y., Wang, H., & Li, P. (2018). Elevated CO2 reduces the adverse effects of drought stress on a high-yielding soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) cultivar by increasing water use efficiency. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 132, 660–665.

- Wang, N., Wang, E., Wang, J., Zhang, J., Zheng, B., Huang, Y., & Tan, M. (2018). Modelling maize phenology, biomass growth and yield under contrasting temperature conditions. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 250, 319–329.

- Wang, Y. , Zhang, Q., Yu, F., Zhang, N., Zhang, X., Li, Y., Wang, M., & Zhang, J. (2024). Progress in Research on Deep Learning-Based Crop Yield Prediction. Agronomy, 14(10), 2264.

- Wickham, H. (2025). A personal history of the tidyverse.

- Wu, X., Liu, H., Li, X., Ciais, P., Babst, F., Guo, W., Zhang, C., Magliulo, V., Pavelka, M., Liu, S., Huang, Y., Wang, P., Shi, C., & Ma, Y. (2018). Differentiating drought legacy effects on vegetation growth over the temperate Northern Hemisphere. GLOBAL CHANGE BIOLOGY, 24(1), 504–516. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. , Wang, E., He, D., Liu, X., Archontoulis, S. V., Huth, N. I., Zhao, Z., Gong, W., & Yang, W. (2019). Combine observational data and modelling to quantify cultivar differences of soybean. European Journal of Agronomy, 111, 125940.

- Yang, L., Song, W., Xu, C., Sapey, E., Jiang, D., & Wu, C. (2023). Effects of high night temperature on soybean yield and compositions. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1065604.

- Zandalinas, S. I., & Mittler, R. (2022). Plant responses to multifactorial stress combination. New Phytologist, 234(4), 1161–1167. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N., Meng, P., He, Y., & Yu, X. (2017). Interaction of CO2 concentrations and water stress in semiarid plants causes diverging response in instantaneous water use efficiency and carbon isotope composition. BIOGEOSCIENCES, 14(14), 3431–3444. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G., Chen, J., & Li, W. (2020). Impacts of CO2 elevation on the physiology and seed quality of soybean. Plant Diversity, 42(1), 44–51.

- Zinta, G., AbdElgawad, H., Peshev, D., Weedon, J. T., Van den Ende, W., Nijs, I., Janssens, I. A., Beemster, G. T., & Asard, H. (2018). Dynamics of metabolic responses to periods of combined heat and drought in Arabidopsis thaliana under ambient and elevated atmospheric CO2. Journal of Experimental Botany, 69(8), 2159–2170.

- Zipper, S. C. , Qiu, J., & Kucharik, C. J. (2016). Drought effects on US maize and soybean production: Spatiotemporal patterns and historical changes. Environmental Research Letters, 11(9), 094021.

Figure 1.

Soybean grains (g) grams through 125 days after the experiment under ambient, elevated CO2, temperature, and drought conditions. Treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Data are represented by means ± standard errors (n = 10). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Soybean grains (g) grams through 125 days after the experiment under ambient, elevated CO2, temperature, and drought conditions. Treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Data are represented by means ± standard errors (n = 10). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Non-structural carbohydrates in soybean grains (µg.mg.DW-1) growth through 125 days under ambient, elevated CO2, temperature, and drought conditions. Panels on the left (a–e) represent temperature treatments, while the panels on the right (f–j) correspond to the drought treatments. Glucose (a, g), fructose (b, h), raffinose (c, i), sucrose (d, j), and starch (f, k) in mature grains harvested from soybean. Treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Data are represented by means ± standard errors (n = 10). Different letters have significant differences among treatments, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Non-structural carbohydrates in soybean grains (µg.mg.DW-1) growth through 125 days under ambient, elevated CO2, temperature, and drought conditions. Panels on the left (a–e) represent temperature treatments, while the panels on the right (f–j) correspond to the drought treatments. Glucose (a, g), fructose (b, h), raffinose (c, i), sucrose (d, j), and starch (f, k) in mature grains harvested from soybean. Treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Data are represented by means ± standard errors (n = 10). Different letters have significant differences among treatments, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Total lipids and fatty acids contents (%) in soybean grain growth through 125 days after the experiment under ambient, elevated CO2, temperature, and drought conditions. Panels on the left (a) represent temperature treatments, while the panels on the right (b) correspond to the drought treatments. Fatty acids are represented by palmitic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid, linoleic acid, and linolenic acid in mature grains harvested from soybeans. Treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Data are represented by means ± standard errors (n = 10). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments compared, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Total lipids and fatty acids contents (%) in soybean grain growth through 125 days after the experiment under ambient, elevated CO2, temperature, and drought conditions. Panels on the left (a) represent temperature treatments, while the panels on the right (b) correspond to the drought treatments. Fatty acids are represented by palmitic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid, linoleic acid, and linolenic acid in mature grains harvested from soybeans. Treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Data are represented by means ± standard errors (n = 10). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments compared, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Proteins and amino acids in soybean grain production growth through 125 days after the experiment under ambient, elevated CO2, temperature, and drought conditions. Total amino acids (a, b) and proteins (c, d) in mature grains harvested from soybean. Treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Data are represented by means ± standard errors (n = 10). Different letters indicate statistical differences among treatments compared, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Proteins and amino acids in soybean grain production growth through 125 days after the experiment under ambient, elevated CO2, temperature, and drought conditions. Total amino acids (a, b) and proteins (c, d) in mature grains harvested from soybean. Treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Data are represented by means ± standard errors (n = 10). Different letters indicate statistical differences among treatments compared, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Carbon and nitrogen content (%) in soybean grain growth through 125 days after the experiment under ambient, elevated CO2, temperature, and drought conditions. Panels on the left (a-c) represent temperature treatments, while the panels on the right (d-f) correspond to the drought treatments. Carbon and nitrogen content from soybean grains are represented by nitrogen (a, d), carbon (b, e), and carbon/nitrogen (c, f) in mature grains harvested from soybeans. Treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Data are represented by means ± standard errors (n = 10). Different letters indicate statistical differences among treatments compared, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Carbon and nitrogen content (%) in soybean grain growth through 125 days after the experiment under ambient, elevated CO2, temperature, and drought conditions. Panels on the left (a-c) represent temperature treatments, while the panels on the right (d-f) correspond to the drought treatments. Carbon and nitrogen content from soybean grains are represented by nitrogen (a, d), carbon (b, e), and carbon/nitrogen (c, f) in mature grains harvested from soybeans. Treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Data are represented by means ± standard errors (n = 10). Different letters indicate statistical differences among treatments compared, according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Path diagram using Generalized Linear Model (GLM) results illustrates relationships between total biomass at 60 days under elevated CO₂, temperature, and drought (isolated or combined), and their impacts on soybean production, and quality compared with ambient conditions at 125 days. According to treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Solid lines represent positive and dashed lines are negative values in soybean grain and quality. Bold labels with an asterisk (*) and thick lines denote statistically significant effects (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Path diagram using Generalized Linear Model (GLM) results illustrates relationships between total biomass at 60 days under elevated CO₂, temperature, and drought (isolated or combined), and their impacts on soybean production, and quality compared with ambient conditions at 125 days. According to treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Solid lines represent positive and dashed lines are negative values in soybean grain and quality. Bold labels with an asterisk (*) and thick lines denote statistically significant effects (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Path diagram using Generalized Linear Model (GLM) results illustrates relationships between total biomass at 60 days under elevated CO₂, temperature, and drought (isolated or combined), and their impacts on soybean production, and quality compared with ambient conditions at 125 days. According to treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Solid lines represent positive and dashed lines are negative values in soybean grain and quality. Bold labels with an asterisk (*) and thick lines denote statistically significant effects (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Path diagram using Generalized Linear Model (GLM) results illustrates relationships between total biomass at 60 days under elevated CO₂, temperature, and drought (isolated or combined), and their impacts on soybean production, and quality compared with ambient conditions at 125 days. According to treatments applied include [aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Temp (400 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); eCO2+Temp (800 ppm CO2 + 5 °C); aCO2 (400 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); eCO2 (800 ppm CO2 + ambient temperature); Drought (400 ppm CO2 + watering reduction); and eCO2+Drought (800 ppm + watering reduction)]. Solid lines represent positive and dashed lines are negative values in soybean grain and quality. Bold labels with an asterisk (*) and thick lines denote statistically significant effects (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Observed and predicted values of grain and quality (soluble sugars, starch, lipids, proteins, and amino acids) traits under different climate change treatments as estimated by generalized linear models (GLMs). Treatments include ambient CO₂ (aCO₂), elevated CO₂ (eCO2), increased temperature (Temp), drought, and their combinations. For each trait, the table shows the mean ± standard error of observed and predicted values, the root means square error (RMSE), and the fitted model equation in the form y = α + βx + ε, where α is the intercept and β the slope coefficient. Trait-specific intercepts (α) are provided above each group (production, soluble sugars, starch, lipids, proteins, and amino acids).

Table 1.

Observed and predicted values of grain and quality (soluble sugars, starch, lipids, proteins, and amino acids) traits under different climate change treatments as estimated by generalized linear models (GLMs). Treatments include ambient CO₂ (aCO₂), elevated CO₂ (eCO2), increased temperature (Temp), drought, and their combinations. For each trait, the table shows the mean ± standard error of observed and predicted values, the root means square error (RMSE), and the fitted model equation in the form y = α + βx + ε, where α is the intercept and β the slope coefficient. Trait-specific intercepts (α) are provided above each group (production, soluble sugars, starch, lipids, proteins, and amino acids).

| Grain |

Observed |

Predicted |

RMSE |

Model (y = α+ βx +ϵ)

|

|

Production (g DW) |

|

|

|

α = 1.67 |

| aCO2

|

6.97 ± 0.78 |

6.62 ± 0.33 |

3.04 |

y = 0.638x + 0.172 |

| eCO2

|

16.9 ± 1.01 |

16.56 ± 0.79 |

3.85 |

y = 0.809x + 0.142 |

| Temp |

0.63 ± 0.15 |

0.65 ± 0.02 |

0.47 |

y = -0.116x + 0.118 |

| Drought |

2.78 ± 0.24 |

2.76 ± 0.09 |

0.74 |

y = -0.138x + 0.141 |

| eCO2+Temp |

16.93 ± 1.48 |

16.24 ± 0.90 |

5.92 |

y = 0.879x + 0.154 |

| eCO2+Drought |

4.04 ± 0.41 |

3.90 ± 0.39 |

1.39 |

y = 0.208x + 0.107 |

|

Soluble sugars (µg.mg. DW-1) |

|

|

|

α = 40.28 |

| aCO2

|

33.73 ± 1.78 |

32.32 ± 1.61 |

9.91 |

y = -0.838x + 0.569 |

| eCO2

|

34.26 ± 1.33 |

33.66 ± 1.61 |

5.76 |