1. Introduction

Sign language (SL) is one of the most common ways for many deaf people to communicate information and consists of specific gestures. It is challenging for most non-disabled individuals to understand these gestures directly. SL recognition is a process of identifying and classifying gesture information obtained by sensors through a computer. SL recognition a crucial area in human-computer interaction research. SL can be translated into speech or text information, aiding communication for deaf and mute individuals with those who can hear and speak. It also finds applications in areas such as gesture control. In comparison with general gesture-based human-computer interaction, natural sign language involves hand shape, position, movement and other elements, making it more complex and variable [

1]. In recent years, it has become a focus area for people’s research. Many sign languages have been studied, such as American Sign Language [

2,

3], Korean Sign Language [

4], Indonesian Sign Language [

5] and Chinese sign language (CSL) [

1,

6] etc.

Traditional gesture recognition research can be divided into two categories in terms of sensors: data gloves [

7,

8] and computer vision-based technologies [

9]. The first computer vision-based technology uses cameras to obtain images and uses image processing techniques to complete the sign language recognition. This method does not need to wear any equipment and is low in cost, but the background environment and light source have a greater impact on the recognition result. The other is that data gloves often use multi-sensor fusion, which captures the hand’s position, direction, and finger bending to reflect the spatial motion trajectory, posture, and timing information of the hand. It has a good recognition effect because of the rich information. This method has a high recognition rate, but because the device is complex to wear and difficult to carry, the cost is high, and it is difficult to promote the use.

Compared with the traditional method, the surface electromyography (sEMG) signal can be used to measure the electrical signals of the muscles generated by the fingers of the arm when performing gestures by using the sEMG sensor placed on the skin surface of the human arm. The important method of artificial limbs [

10], using sEMG for sign language recognition has received more and more attention from researchers in recent years [

1,

2,

3,

11]. It has the advantages of low cost and no environmental impact. Especially after the emergence of the emerging multi-channel EMG arm ring, it has greatly increased its portability and practicality. The collected multi-channel EMG signals often have a large amount of data and also contain substantial noise, which takes time to process. However, sign language recognition often has real-time requirements. This poses challenges for researchers. This paper presents an improved artificial neural network (ANN)-based CSL prediction model that uses the method of segmenting the training set to reduce the amount of data processed and greatly improve the recognition speed.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) We proposed a real-time CSL recognition framework based on surface electromyography (sEMG), which adopts an efficient sub-window segmentation strategy to enable early gesture prediction before the action is completed.

(2) Using threshold segmentation, we can achieve a recognition accuracy of more than 91% using only 50% of the training data, which significantly shortens the training time.

(3) We use a lightweight ANN model with only three layers suitable for low-computing power devices, making our system easier to deploy in practical assistive scenarios.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section II describes related work, and details methods and experiments described in section III. Section IV introduces the experimental results and discusses the impact of different training set sizes on the experimental results. Section V gives the conclusions of the work.

2. Related Work

Recent research on SL recognition has increasingly explored sEMG, especially with the availability of wearable armbands such as the Myo, which allow multi-channel recording in a compact and portable form. As a subset of gesture recognition, SL recognition has also benefited from the broader advances in real-time gesture recognition.

Early sEMG studies demonstrated that compact time-domain features can achieve reliable classification with modest computational demand, laying the foundation for real-time SL systems. Many researchers have combined sEMG with other sensor modalities. For example, Wu et al. [

12] integrated sEMG and inertial measurement units (IMUs) to classify 80 ASLwords using classical classifiers, achieving promising user-dependent performance in online tests. Similarly, Yang et al. [

1] evaluated the classification capability of sEMG, accelerometer, and gyroscope signals, and proposed a tree-structured framework that achieved 94.31% and 87.02% accuracy in user-dependent and user-independent tests, respectively, for 150 CSL subwords. While sensor fusion often improves recognition accuracy, it also inevitably increases system complexity and latency.

Motivated by real-time constraints, several studies focused on sEMG-only approaches. Savur et al. [

13] collected eight-channel sEMG from the forearm and extracted ten features per channel, achieving 82.3% real-time accuracy on 26 ASL letters using SVM. With the rise of consumer wearable devices, the Myo armband has played a pivotal role in enabling SL recognition with low cost and high accessibility. Early Myo-based works established real-time baselines with classical classifiers, achieving sub-second latency on alphabetic gestures [

14]. More recently, Kadavath et al. [

15] designed an EMG-based SL system using Myo that combined wearability and rapid deployment with competitive performance, while Umut et al. [

16] demonstrated real-time SL-to-text/voice conversion, confirming its practicality for continuous assistive scenarios.

Another line of work investigates robustness to electrode displacement and user variability. For example, Wang et al. [

17] systematically analyzed the effect of limb position and electrode shift on recognition performance, and proposed strategies for faster re-calibration and improved robustness. Such studies reflect the community’s growing interest in adaptive sEMG systems suitable for daily deployment.

To further improve accuracy, deep learning models have also been applied. López et al. [

18] proposed a CNN–LSTM hybrid using spectrogram features, which improved robustness but significantly increased computational cost, illustrating the trade-off between modeling capacity and real-time feasibility on embedded devices. Similarly, [

19] compared four classifiers on 40 daily-life gestures, emphasizing that models with high training cost are not well-suited for real-time deployment, especially under small training sets.

Position of our work. Within this context, our study focuses on a lightweight ANN-based CSL recognition framework using Myo armband sEMG. By framing the task as short-window classification aligned with muscle activity and incorporating a sliding sub-window mechanism, our system enables early prediction before the gesture is completed. Furthermore, by segmenting the training set, we reduce training time while maintaining robust recognition of 20 CSL gestures, thereby complementing and extending prior Myo-based studies.

3. Methodology

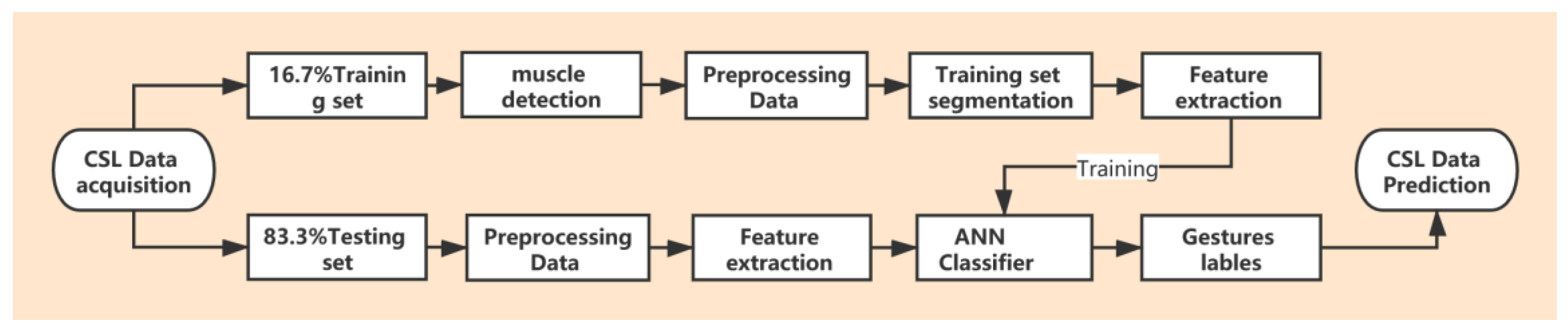

The sEMG signal is located in a high-dimensional space and takes into account the characteristics of nonlinearity and non-stationarity. Traditional gesture recognition models usually use high-complexity models, and training requires a large number of training data sets, long processing time and large memory requirements. From a practical point of view, developing a real-time sign language prediction model requires low complexity and a model that can achieve good results with a small number of samples. The model framework diagram we proposed is shown in

Figure 1. Using the training set segmentation method can save processing time very well, so as to achieve the purpose of real-time prediction of CSL gestures.

3.1. EMG Data Acquisition

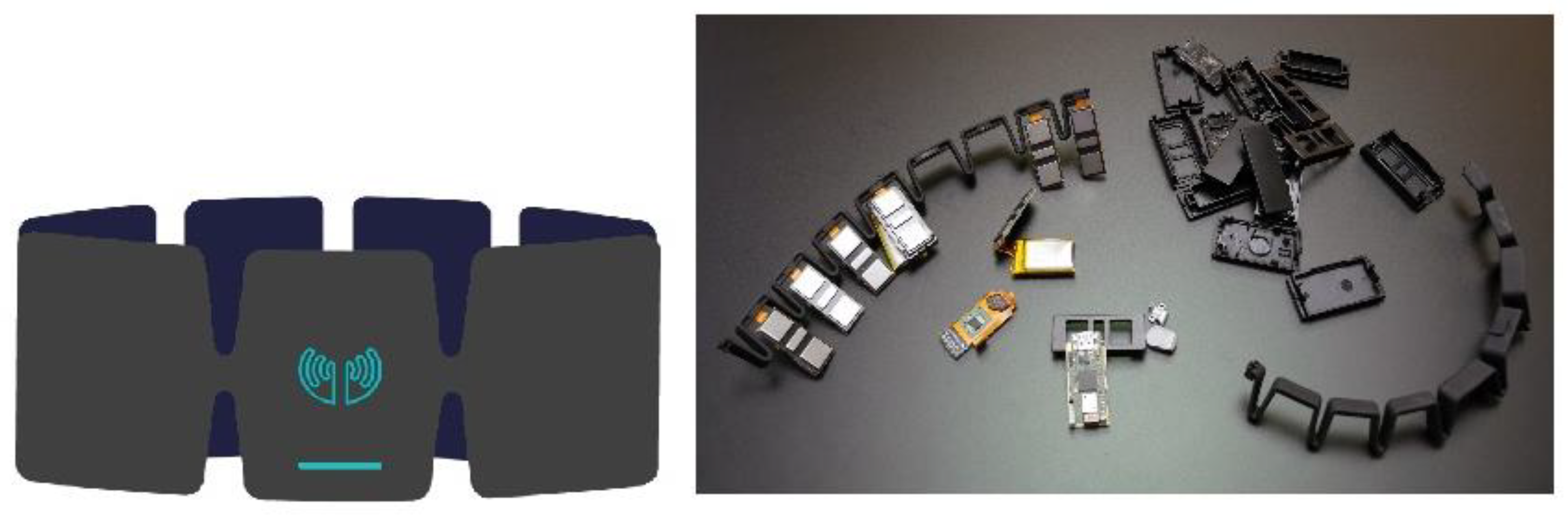

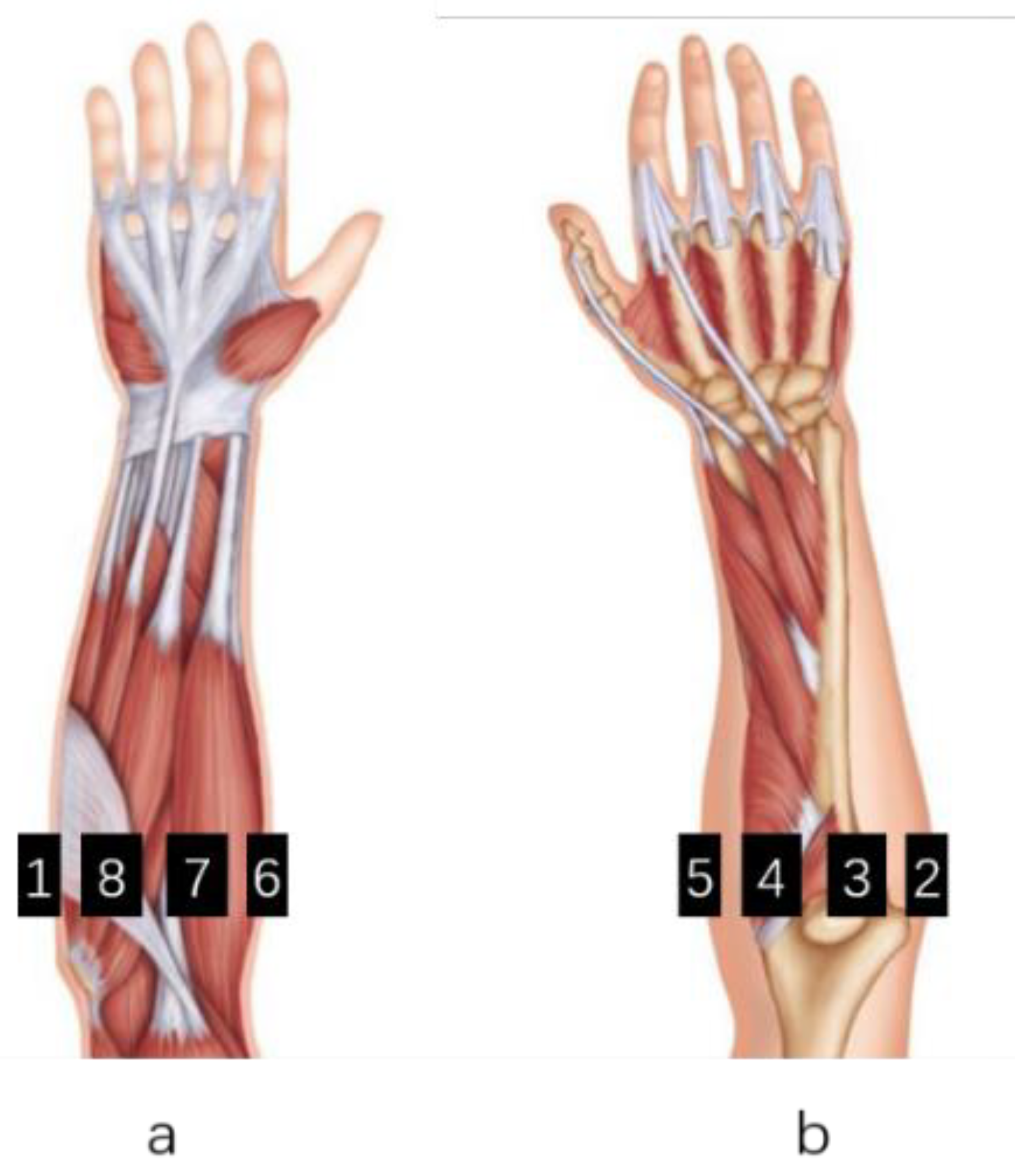

Eight healthy test subjects (Four males and four females, age range 22-27 years old, average age 23) participated in the experiment. They have not previously trained in CSL. During the experiment, they performed sign language actions by imitating pictures. To collect sEMG data, an eight channel low-cost consumption equipment MYO is used, as shown in

Figure 2, which consists of eight pairs of dry electrodes and with a low sampling rate (200Hz).

Although the dry electrode is less accurate and robust to motion artifact than traditional gel-based electrodes [

20]. But it can make the user do not need to shave and clean the skin in advance to obtain optimal contact between user’s skin and electrodes, it only needs to be worn directly on the arm, it is very easy to use (

Figure 3).

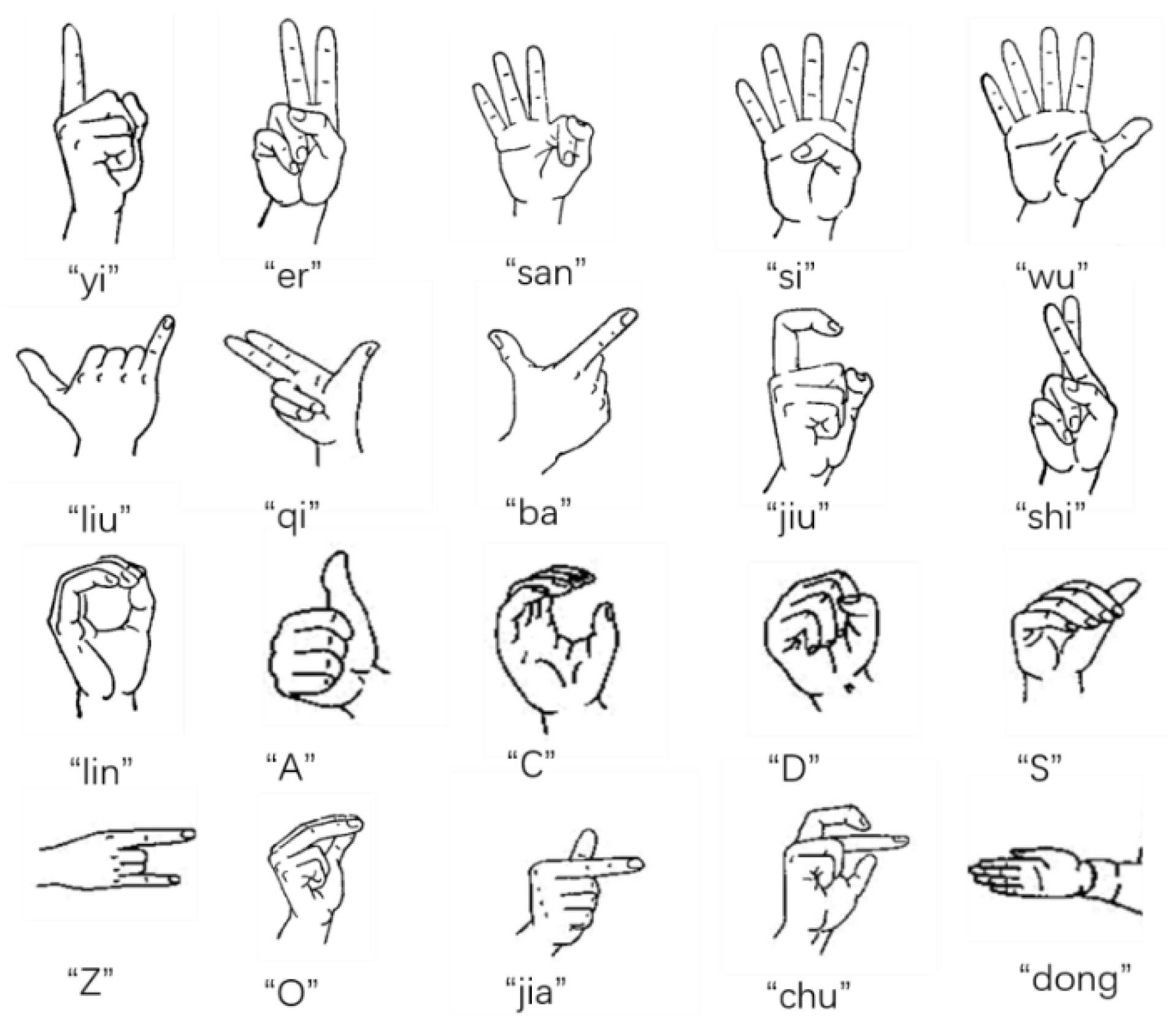

In order to facilitate the recording of experimental data, we selected 21 gestures, including 20 common sign language gestures in Chinese, and a relaxation gesture. The gesture illustration describes in

Figure 4.

In addition, there is also a gesture in a relaxed state, a total of 21 CSL are recognized, and these gestures are completed by the right hand alone. The collection device is uniformly worn on a fixed position on the subject’s right forearm. Each CSL gesture was performed for 30 sessions, and the sEMG signal was recorded for 2 seconds in an action cycle. Each action recorded 400 data points, and each participant systematically performed this operation in the same way. The data of each action is randomly divided into 5 groups for the training set, and the remaining 25 groups are used for the test set. The main parameters of sensors and data set collection are shown in

Table 1.

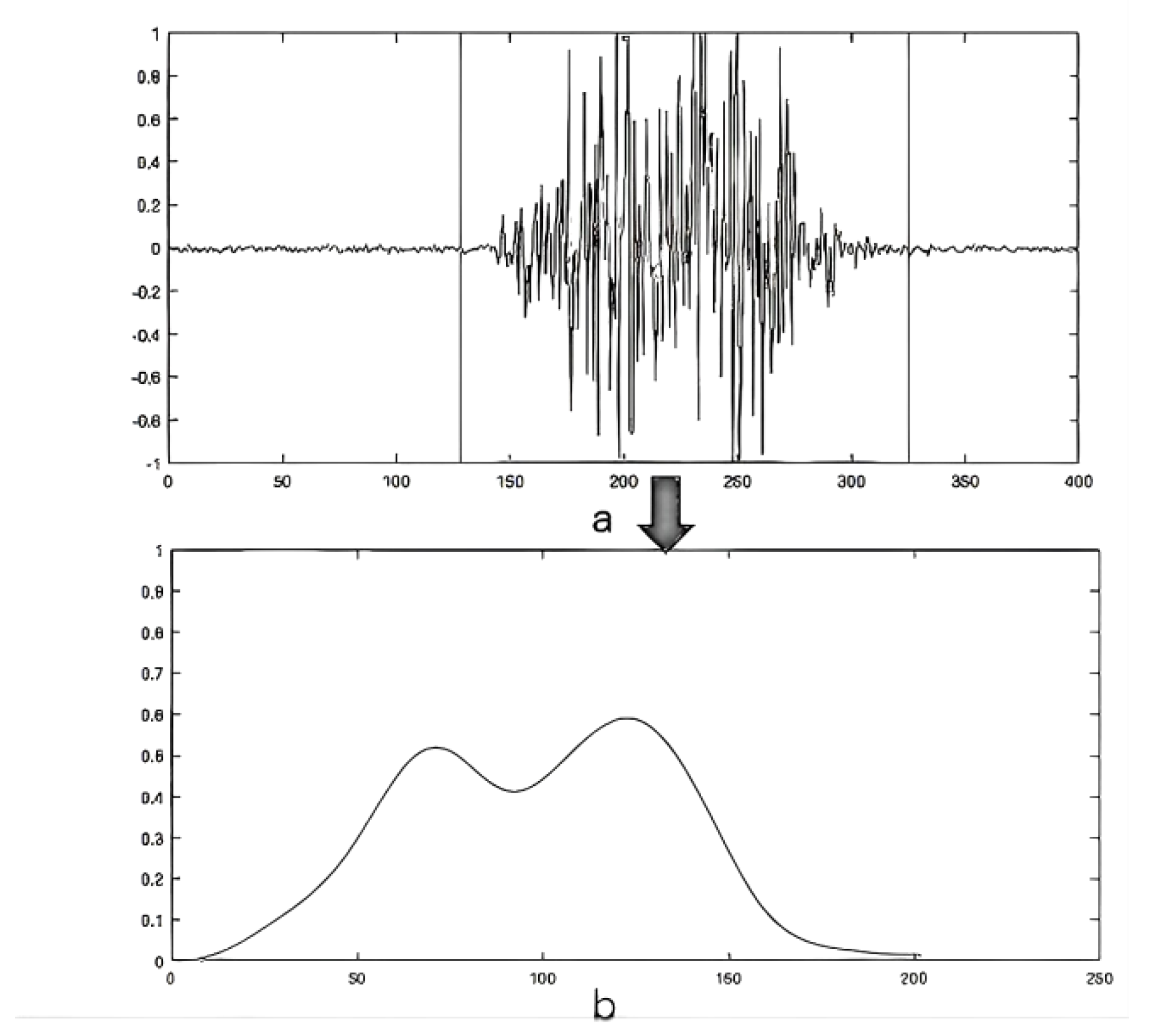

3.2. Data Preprocessing

When we obtain the original signal, due to the skin temperature, tissue structure, measurement site, etc., various noise signals or artifacts may be mixed, which may affect the result of feature extraction and thus the diagnosis of EMG signals [

21]. Therefore, the original signal needs to be preprocessed. First, it is standardized using Max-Min,obtaining. Then use the short-time Fourier transform to obtain the spectrum of the original signal, calculate the norm of the spectrum, to detect the area of muscle activity during hand movement and remove the inactive signal of the head and tail. Speed up training time and improve accuracy. Use an absolute value function and a 4th order Butterworth low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 5 Hz to smooth the signal and remove the original signal noise as shown in

Figure 5.

3.3. Data Segmentation

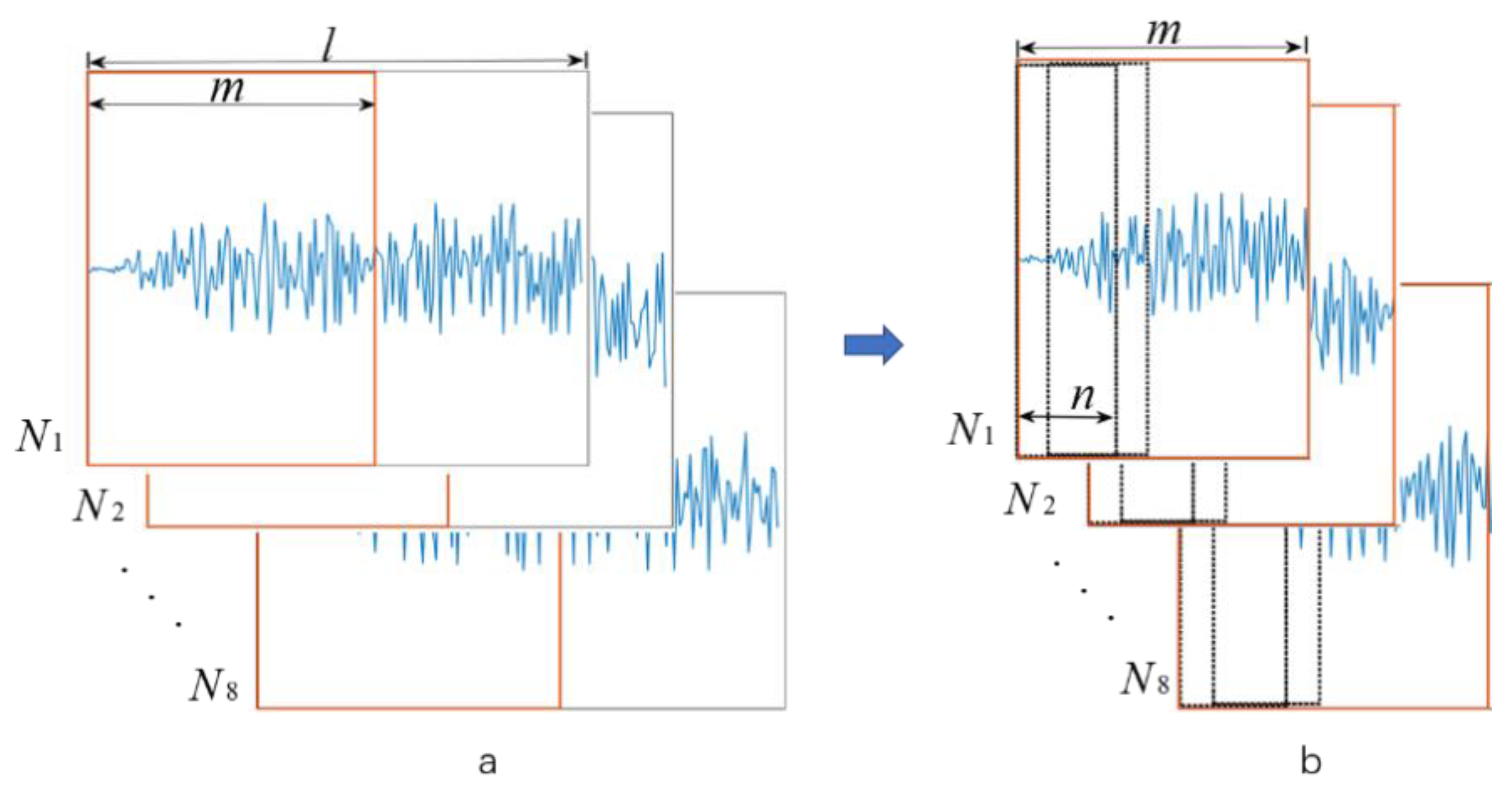

From the perspective of practical applications, it is difficult to obtain a large number of data sets for a specific user model, and the model needs to be trained for each person’s use. Therefore, it is very important to save the training time cost of real-time models on a limited data set. In our proposed model, after the data is preprocessed, we need to segment the training data in order to facilitate each user to train in the shortest time before use.

Since our model can recognize gestures and perform them at the same time, we can make predictions before the actions are completed. The specific method will be described later. Before training, we segment the training data, as shown in the figure, where the length of the training set returned after applying the muscle detection function is L, and we move to intercept the data of length m from the starting point to form a new training set T

N.

Where N denotes the number of sEMG channels, K represents the sub-windowing operation applied during segmentation, and FN indicates the original windowed signal from which features are extracted. This notation ensures that the segmentation and feature extraction process is explicitly defined for each channel and each sub-window. A new signal T is obtained after segmentation.

In this work, we adopt a two-stage segmentation strategy to support early gesture prediction. The process of data segmentation is shown in

Figure 6. First, once the muscle activity region is detected, we apply temporal truncation to retain only the initial portion of the gesture sequence. This fixed-window truncation ensures that the model focuses on the early stage of muscle activation, allowing the system to anticipate gestures before they are completed. Second, within the truncated segment, we introduce a sliding sub-window mechanism, where short overlapping windows are continuously extracted and processed by the classifier. This hierarchical segmentation, i.e., temporal truncation followed by a sliding sub-window strategy, combines the advantages of early decision making and fine-grained temporal resolution, improving responsiveness and prediction stability compared to traditional fixed-length or overlapping window strategies applied to the entire gesture. For this work, we used a uniform window length of 25 points for training set and testing set and a shorter window length can get better real-time performance. Given our sampling frequency of 200 Hz, each window corresponds to a time duration of 125 MS, which is sufficient to capture the dynamic muscle activity for the majority of CSL gestures. We deliberately frame the task as a short-window classification problem. Each 25-point sub-window provides sufficient temporal context such that a lightweight ANN can achieve accurate recognition while maintaining an inference time of about 20 ms per cycle, which is crucial for deployment on embedded devices. A shorter window would not include enough temporal information, while longer windows introduce latency and may reduce real-time responsiveness.

3.4. Feature Extraction and CSL Classification

After the signal has been pre-processed and segmented, feature extraction is first performed. Appropriate feature extraction is very important for the identification and classification of sEMG signals. The characteristics based on time statistics have been widely used in research. Compared with the frequency domain and time-frequency methods, real-time constraints can be performed under simple hardware conditions [

22]. In order to facilitate the calculation, we extracted 6 representative eigenvalues with lower calculation dimensions in the preprocessed EMG signal, which are waveform length (WL), scope sign changes (SSC), root mean square (RMS), variance (VAR), and average frequency. These features were adopted based on their demonstrated effectiveness in previous EMG-based gesture recognition studies, including our own prior work [

23,

24]. Following established practices ensures consistency with the literature and provides reliable performance without introducing unnecessary computational overhead. In this study, we also re-validated their empirical performance under a constrained real-time setting. Compared with frequency-domain, Fourier-based, or wavelet-based time–frequency descriptors, time-domain features can be extracted with minimal latency and do not require extensive windowing or large-scale matrix operations, thereby maintaining very low computational cost. At the same time, they capture essential information on amplitude variation, signal complexity, and spectral dynamics, which makes them particularly suitable for deployment on wearable or embedded devices with limited processing power and strict latency constraints.

For the classification part, we used a simple three-layer feedforward ANN classifier because it is computationally efficient, easy to implement, and well suited for low-latency, real-time prediction when the dataset is limited. Given the real-time constraints and the relatively small size of the training dataset, ANN offer a good balance between performance and computational complexity. Although recurrent models such as LSTM and GRU are effective for modeling long-term dependencies in sequential data, they typically incur higher computational and memory costs, which would hinder deployment on resource-constrained platforms where low-latency operation is critical. The size of the parameter depends on the complexity of the network structure and the input dimension. In the gesture recognition application of this study, compared with CNN and LSTM, ANN structure is relatively simple, and the number of parameters is proportional to the number of layers and the number of neurons in each layer; CNN extracts local features through convolution kernels, and the number of parameters is less than that of the fully connected network, but it will still increase due to the increase in the number of channels; LSTM has a gating mechanism, and there are multiple weight matrices in each LSTM unit, so the number of parameters far exceeds ANN[

25].

In this study, ANN has three layers, namely the input layer, hidden layer, and output layer. The number of nodes in the input layer includes the sub-window data and the extracted feature vector, with 8 channels and a total of 48 neurons; the number of nodes in the hidden layer is 128, and the tanh transfer function is used to introduce the necessary nonlinearity into the model; the output layer uses a softmax activation function to normalize the output into a probability distribution, and the number of nodes is 20 for gesture categories. The model is trained using the Adam optimizer, which combines the advantages of momentum-based methods and adaptive learning rates. The Adam optimizer was chosen because it is efficient and suitable for our relatively small dataset. The model was trained for 150 iterations, which was sufficient to achieve convergence according to preliminary tests, and the batch size was 64 to balance training speed and memory usage. We counted the labels returned by ANN and set a threshold.

Where represents the recognized gesture and m returns the count label. Real-time prediction was made during the sub-window moving backward, and the gesture category is output after the threshold is reached, which can effectively improve the real-time response of the system.

4. Analysis of Results

We used three different methods to evaluate and analyze the performance of the system. The first is to analyze the prediction accuracy of all 21 gestures of all subjects. The next is to discuss our data segmentation to identify the accuracy. And the evaluation of the change in training time for the segmented dataset. Finally, we evaluate the superiority of our proposed real-time system in response time.

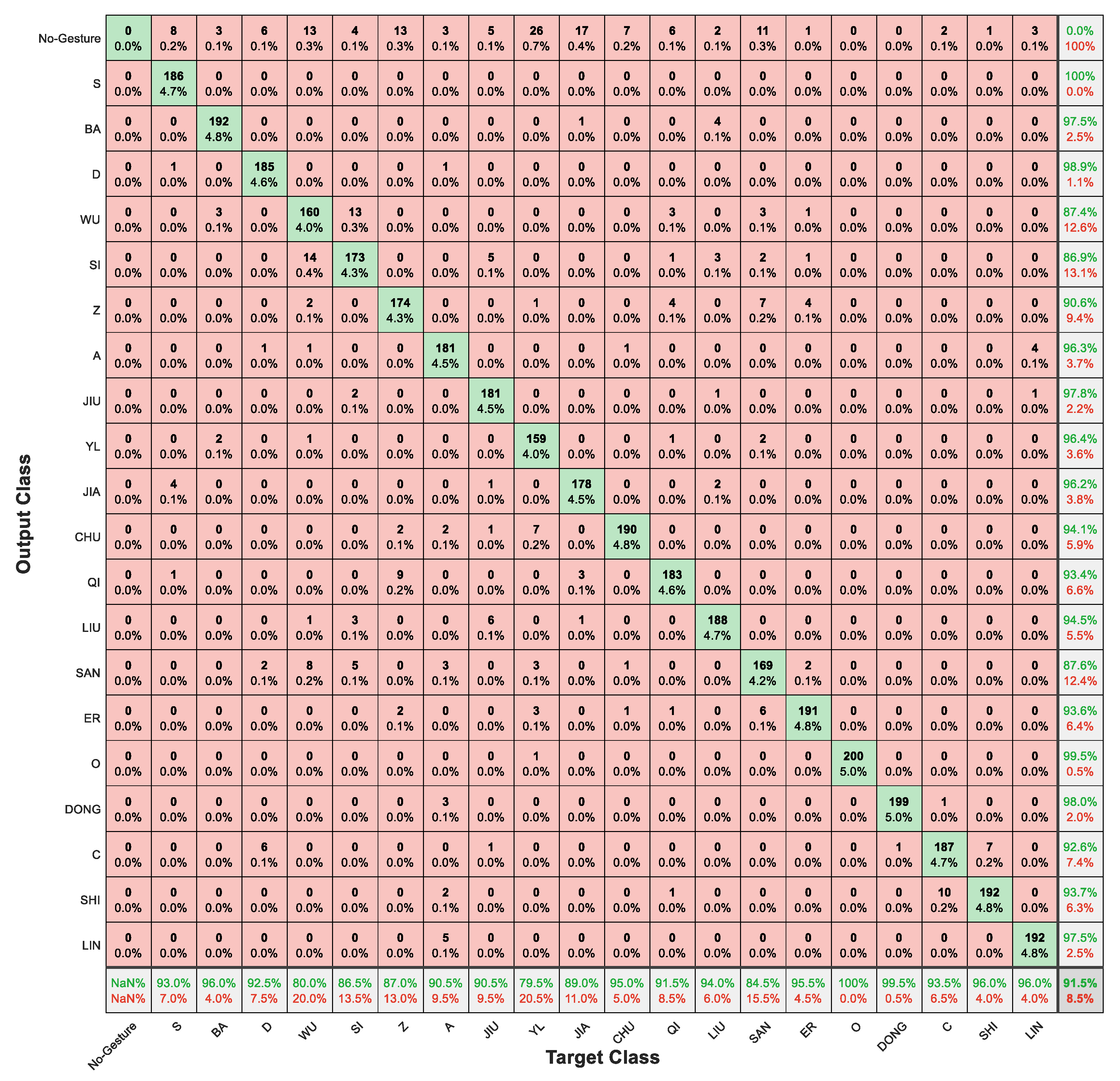

4.1. SL Gestures Prediction Performance Evaluation

In this article, we use the confusion matrix results obtained from all the training sets as shown in the figure, showing the results of all the non-test sets of all the subjects. As can be seen from the

Figure 7, the overall prediction accuracy of 21 actions has reached 91.5%, the best performing gestures reached 100%, and the worst performing also reached 79.5%.

The evaluation results presented in

Figure 7 reflect the aggregated classification performance across all eight participants (four males and four females). Each subject contributed 30 repetitions per gesture, resulting in a comprehensive multi-user dataset. While Table II highlights accuracy and training time for four representative users to illustrate training scalability, the confusion matrix in

Figure 7 provides a complete visualization of the system’s prediction accuracy across all 21 gesture classes and all eight users. This aggregation ensures that the model’s performance reflects inter-user variability and generalization capability.

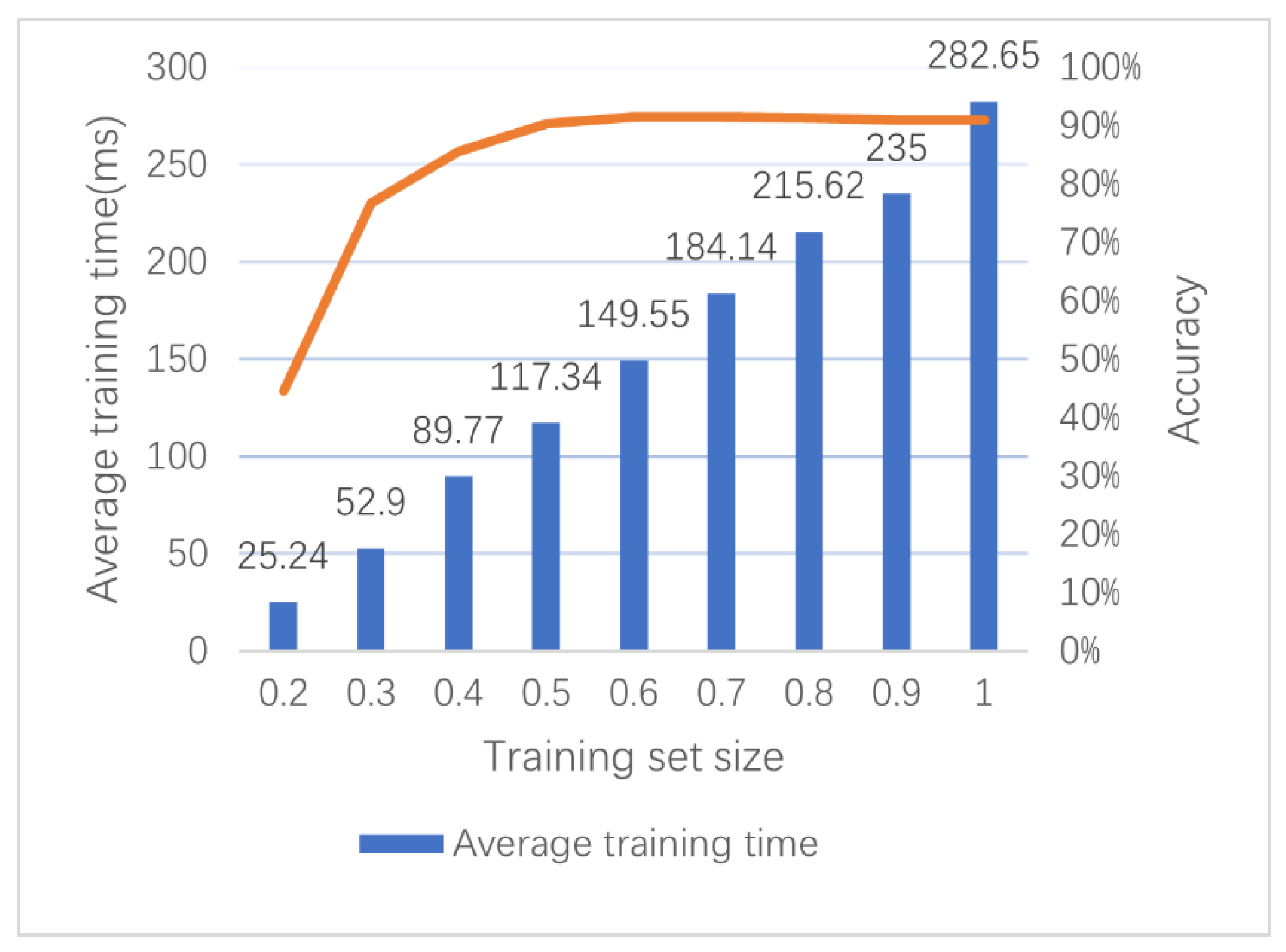

4.2. Evaluation of Training Set Size

In our model, only a part of the training set is segmented for training to achieve the purpose of saving training time. We evaluated training sets of different sizes, ranging from 20% to 100%. We analyze from the two aspects of prediction accuracy and average training time, and the results are shown in

Figure 6, where the accuracy refers to the overall accuracy rate including all test sets, and the average training time is the training time of each group of data calculated on the host MATLAB 2018b, (OS: Windows 10; CPU: i7-9750H; RAM: 16GB).

From

Figure 8, we can see that as the length of the training set increases, the accuracy rate increases first, then gradually approaches plateau, and finally stabilizes at about 91%. After the training set size is 50%, the accuracy changes are small, because our real-time system can complete gesture prediction when almost all gestures are not completed. The 50% training data does not refer to reducing the number of gesture repetitions, but to the time truncation of each gesture instance. Specifically, each gesture duration is 2 seconds and contains 400 samples, and we only extract the first 50% of the time series, or 200 samples, from each repetition for training. The training time increases almost linearly with the increase of the training set length. This is as we expected. As the training data increases, the training time cost will inevitably increase. Therefore, for our proposed model, time can be saved by reducing the amount of training data, and the original data can be reduced by half and the expected prediction result can be achieved. This design enables the system to learn to predict gestures in the early stages of gesture execution, thereby improving real-time responsiveness. The total number of training samples (i.e., gesture instances) remains unchanged; only the signal duration used for each instance is shortened. This strategy ensures both training efficiency and early prediction capabilities without compromising category coverage or representation balance.

In

Table 2, we can see that when the training set is only 20%, the accuracy of user 2 is only 17%. This is probably because the length of the training set is too small, which is less than the length of the sub-window, and a large number of gestures are recognized as No-gesture. As the training set increases, the accuracy rate increases rapidly and eventually remains stable.

To further quantify the inter-subject differences, we calculated the average classification accuracy and standard deviation for all subjects at each training set size. As shown in

Table 2, the average accuracy when using 50% of the training data is 0.90, with a standard deviation of ±0.03. In addition, the 95% confidence interval at this data ratio is [0.86, 0.95], indicating that the model performance remains at a high level across different users. Although not subjected to ANOVA/t-tests in this study, the observed performance trends were consistent across users, and more rigorous statistical vali. This also shows that the system maintains good generalization capabilities despite natural variations in muscle activation patterns, arm size, and electrode alignment.

4.3. Real-Time Performance of the Model

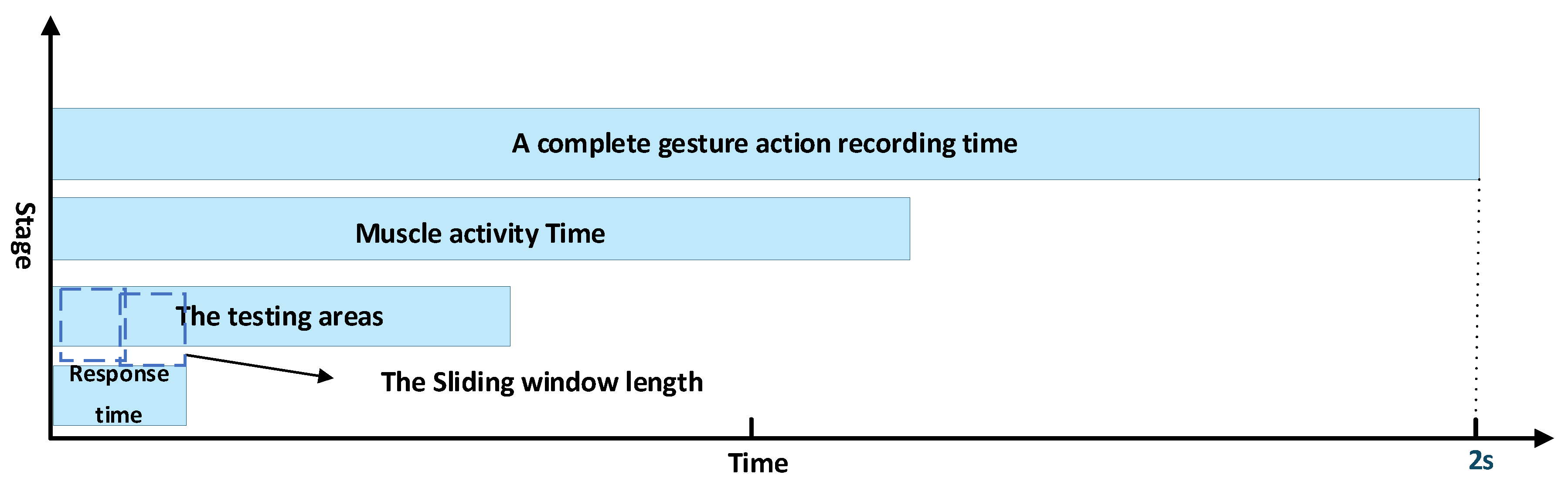

The overall processing timeline of gesture recognition is illustrated in

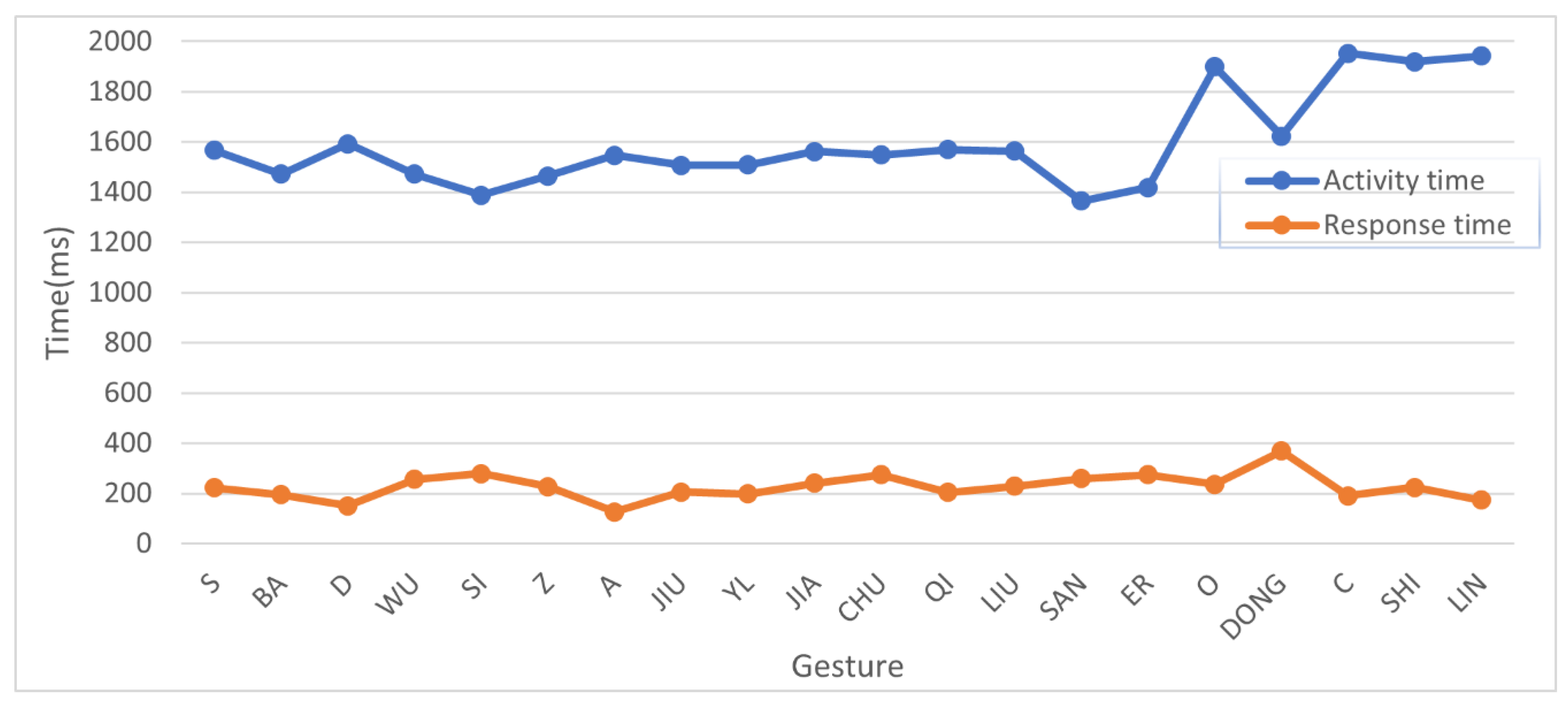

Figure 9. A complete gesture spans approximately 2 seconds, although the detected muscle activity occupies only part of this interval. Within the active region, the system applies sliding sub-windows of 25 points (≈125 ms) to generate predictions. This design enables early decision-making, with the system consistently producing a stable prediction within 200 ms of gesture onset (response time), rather than waiting for the gesture to finish.

Figure 10 further compares gesture action time with response time. Here, movement time represents the duration of detected muscle activity, while response time denotes the interval from gesture onset to the first correct prediction produced by the sliding sub-window mechanism. As shown, a full gesture takes about 1500 ms, but the system outputs a reliable prediction after only ~200 ms, thereby significantly reducing overall recognition delay.

To validate the real-time capability of the proposed CSL recognition system under continuous use, we conducted a streaming experiment in which subjects performed CSL gestures sequentially without interruption. The system continuously acquired and processed sEMG signals in real time using the sliding sub-window strategy. The measured end-to-end latency—including acquisition, preprocessing, feature extraction, and ANN inference—was approximately 20 ms per prediction cycle. This latency remained consistent across gesture types and subjects, and the system maintained robust performance even during overlapping gesture transitions.

4.4. Comparison with Other Methods

To contextualize the effectiveness of our proposed method, we compare it with several representative works on sEMG-based gesture recognition, as shown in

Table 3 Simao et al. [

26] applied recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for online gesture classification and achieved 92.2% accuracy on a small set of six gestures. Xie et al. [

27] utilized convolutional networks for gesture recognition using wearable sensors, attaining 90.0% accuracy over 10 classes, though real-time capability was not specified. Zhang et al. [

28] also employed RNNs for sEMG-based prediction and reported 89.7% accuracy across 12 hand gestures.

In contrast, our proposed ANN-based model achieves 91.3% accuracy on 21 CSL gestures, using only sEMG signals collected from the MYO armband. ANNs are preferred over more complex architectures such as CNNs, LSTMs, or Transformers because our target application prioritizes low latency and low computational cost in a real-time environment. Unlike more complex RNN or CNN architectures, our approach maintains a lightweight structure suitable for real-time deployment and supports early prediction via a moving sub-window strategy. Furthermore, our model achieves high accuracy using just 50% of training data, highlighting its training efficiency. These results demonstrate that, while competitive with recent deep learning methods, our system balances accuracy, simplicity, and speed, which is critical for real-world assistive applications.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a real-time gesture prediction model. This model takes the sEMG of the forearm muscles measured by the muscle arm band as input. For any user, the model can learn to recognize gestures through a training process. Unlike other high-complexity methods that require a large number of samples to train, we employed a low-complexity model trained with a limited number of samples and evaluated on a larger dataset, achieving competitive prediction accuracy.

The model proposed in this paper has higher real-time performance than traditional gesture recognition, which is mainly reflected in three aspects to save time. First, we used a muscle detection function during training to quickly remove the inactive head and tail of the original signal. We then segmented the training set and used only some of the signals to train the model. Experimental results prove that only about 50% of the training set data is needed to reach the final prediction accuracy. Finally, we use an improved ANN classifier to count and classify the labels returned by the sliding sub-window in real time, so that the sign language gestures can be predicted in real time. Future work will consider adding sign language gestures with two-handed movements to improve the practical applicability of the model.

Although the current system focuses on the recognition of single-hand CSL gestures using a single sEMG armband, many real-world CSL gestures involve both hands, either synchronously or with distinct roles. To address this, future work will explore the extension of our system to support bimanual gesture recognition by equipping both forearms with sEMG sensors. The signal features from each arm can be synchronized and fused to form a comprehensive input representation. Additionally, we plan to investigate temporal coordination modeling techniques—such as attention-based fusion or sequence learning networks to effectively capture the interaction between the two hands. These efforts will allow our system to support a wider range of CSL vocabulary and further improve its applicability in real-world assistive communication scenarios. We also plan to extend our framework by benchmarking temporal deep learning models, such as LSTM, GRU, or attention-based networks, under the same real-time constraints. This will allow us to more systematically investigate the trade-offs between accuracy, latency, and deployment feasibility.

In addition to extending the system to support bimanual CSL gestures, we plan to make several methodological improvements to improve statistical robustness and deployment reliability. Future work will incorporate stratified k-fold cross-validation to better assess the generalization ability of the model, especially under class imbalance and small sample conditions. This will allow us to more rigorously evaluate the between-class variance and support model selection to reduce bias. Second, the current decision threshold in the sliding window voting mechanism is empirically chosen by validation on a holdout subset. While these methods are effective, more adaptive methods such as confidence-weighted fusion or dynamic temporal voting can further improve robustness, especially in noisy signal conditions or in the presence of user-specific variables.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Video S1: supplementary video S1.avi.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jinrun Cheng and Kuo Yang; methodology, Jinrun Cheng; software, Kuo Yang; validation, Jinrun Cheng, Xing Hu and Kuo Yang; formal analysis, Jinrun Cheng; investigation, Xing Hu; resources, Jinrun Cheng, Kuo Yang; data curation, Jinrun Cheng; writing—original draft preparation, Jinrun Cheng; writing—review and editing, Xing Hu and Kuo Yang; visualization, Kuo Yang; project administration, Jinrun Cheng. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.:

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSL |

Chinese sign language |

| sEMG |

surface electromyography |

| ANN |

artificial neural network |

References

- Yang, X., Chen, X., Cao, X., Wei, S., & Zhang, X. (2016). Chinese sign language recognition based on an optimized tree-structure framework. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics, 21(4), 994-1004. 7. [CrossRef]

- Hellara, H., Barioul, R., Sahnoun, S., Fakhfakh, A., & Kanoun, O. (2025). Improving the accuracy of hand sign recognition by chaotic swarm algorithm-based feature selection applied to fused surface electromyography and force myography signals. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 154, 110878. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. K., & Chaturvedi, A. (2023). A reliable and efficient machine learning pipeline for American Sign Language gesture recognition using EMG sensors. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 82(15), 23833-23871. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J., Miah, A. S. M., Suzuki, K., Hirooka, K., & Hasan, M. A. M. (2023). Dynamic Korean sign language recognition using pose estimation based and attention-based neural network. IEEE Access, 11, 143501-143513. [CrossRef]

- Nadaf, A. I., Pardeshi, S., & Gupta, R. (2025). Efficient gesture recognition in Indian sign language using SENet fusion of multimodal data. Journal of Integrated Science and Technology, 13(6), 1145-1145. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Chen, X., Zhang, X., Wang, K., & Wang, Z. J. (2012). A sign-component-based framework for Chinese sign language recognition using accelerometer and sEMG data. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 59(10), 2695–2704. [CrossRef]

- Galka, J., Masior, M., Zaborski, M., & Barczewska, K. (2016). Inertial Motion Sensing Glove for Sign Language Gesture Acquisition and Recognition. IEEE Sensors Journal, 16(16), 6310–6316. [CrossRef]

- Gao, W., Fang, G., Zhao, D., & Chen, Y. (2004). A Chinese sign language recognition system based on SOFM/SRN/HMM. Pattern Recognition, 37(12), 2389–2402. [CrossRef]

- Molchanov, P., Gupta, S., Kim, K., & Kautz, J. (2015). Hand gesture recognition with 3D convolutional neural networks. IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 2015-Octob, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Oskoei, M. A., & Hu, H. (2007). Myoelectric control systems—A survey. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 2(4), 275–294. [CrossRef]

- Cheok, M. J., Omar, Z., & Jaward, M. H. (2019). A review of hand gesture and sign language recognition techniques. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics, 10(1), 131–153. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Sun, L., & Jafari, R. (2016). A Wearable System for Recognizing American Sign Language in Real-Time Using IMU and Surface EMG Sensors. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 20(5), 1281–1290. [CrossRef]

- Savur, C., & Sahin, F. (2017). American Sign Language Recognition system by using surface EMG signal. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, SMC 2016 - Conference Proceedings, 2872–2877. [CrossRef]

- Tepe, C., & Demir, M. C. (2022). Real-time classification of emg myo armband data using support vector machine. IRBM, 43(4), 300-308. [CrossRef]

- Kadavath, M. R. K., Nasor, M., & Imran, A. (2024). Enhanced hand gesture recognition with surface electromyogram and machine learning. Sensors, 24(16), 5231. [CrossRef]

- Umut, İ., & Kumdereli, Ü. C. (2024). Novel Wearable System to Recognize Sign Language in Real Time. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 24(14), 4613. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Li, J., Hargrove, L., & Kamavuako, E. N. (2024). Unravelling influence factors in pattern recognition myoelectric control systems: The impact of limb positions and electrode shifts. Sensors, 24(15), 4840. [CrossRef]

- López, L. I. B., Ferri, F. M., Zea, J., Caraguay, Á. L. V., & Benalcázar, M. E. (2024). CNN-LSTM and post-processing for EMG-based hand gesture recognition. Intelligent Systems with Applications, 22, 200352. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Tian, Z., Sun, L., Estevez, L., & Jafari, R. (2015). Real-time American Sign Language Recognition using wrist-worn motion and surface EMG sensors. 2015 IEEE 12th International Conference on Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks, BSN 2015, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- D. Stegeman and B. L. B.U. Kleine. (2012). High-density surface emg: Techniques and applications at a motor unit level. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering, vol. 32(3), 2012. [CrossRef]

- Benalcazar, M. E., Motoche, C., Zea, J. A., Jaramillo, A. G., Anchundia, C. E., Zambrano, P., … Perez, M. (2018). Real-time hand gesture recognition using the Myo armband and muscle activity detection. 2017 IEEE 2nd Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting, ETCM 2017, 2017-Janua, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Tkach, D., Huang, H., & Kuiken, T. A. (2010). Study of stability of time-domain features for electromyographic pattern recognition. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 7(21), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Z Zhang, K Yang, J Qian, & L Zhang. (2019). Real-Time Surface EMG Pattern Recognition for Hand Gestures Based on an Artificial Neural Network. Sensors, 19(14), 3170. [CrossRef]

- Le, H., Panhuis, M. I. H., Spinks, G. M., & Alici, G. (2024). The effect of dataset size on EMG gesture recognition under diverse limb positions. In 2024 10th IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference for Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob) (pp. 303-308). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Wei, H., Nie, J., & Yang, H. (2025). Rapid Calibration of High-Performance Wavelength Selective Switches Based on the Few-Shot Transfer Learning. Journal of Lightwave Technology. 43(14), 6682-6689. [CrossRef]

- Simao, M.A.; Neto, P.; Gibaru, O. (2019). EMG-based Online Classification of Gestures with Recurrent Neural Networks. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2019, 128, 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Li, B.; Harland, A. (2018). Movement and Gesture Recognition Using Deep Learning and Wearable-sensor Technology. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Pattern Recognition, Beijing, China, 18–20 August 2018; pp. 26–31. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, He C, Yang K. (2020). A novel surface electromyographic signal-based hand gesture prediction using a recurrent neural network. Sensors, 2020, 20(14): 3994. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, J. G., Teixeira, J. M., Figueiredo, L. S., & Teichrieb, V. (2016). Evaluating Sign Language Recognition Using the Myo Armband. Proceedings - 18th Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality, SVR 2016, (June), 64–70. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).