Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Summary

1.2. 3D Printing

1.3. Prior 3D-Printed Electromechanical Actuators

1.4. Prior 3D-Printed Actuators and Magnets

1.5. Substantial Implications of This Work

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Integrated System Architecture

2.2. Experimental Summary

2.3. Memory Design

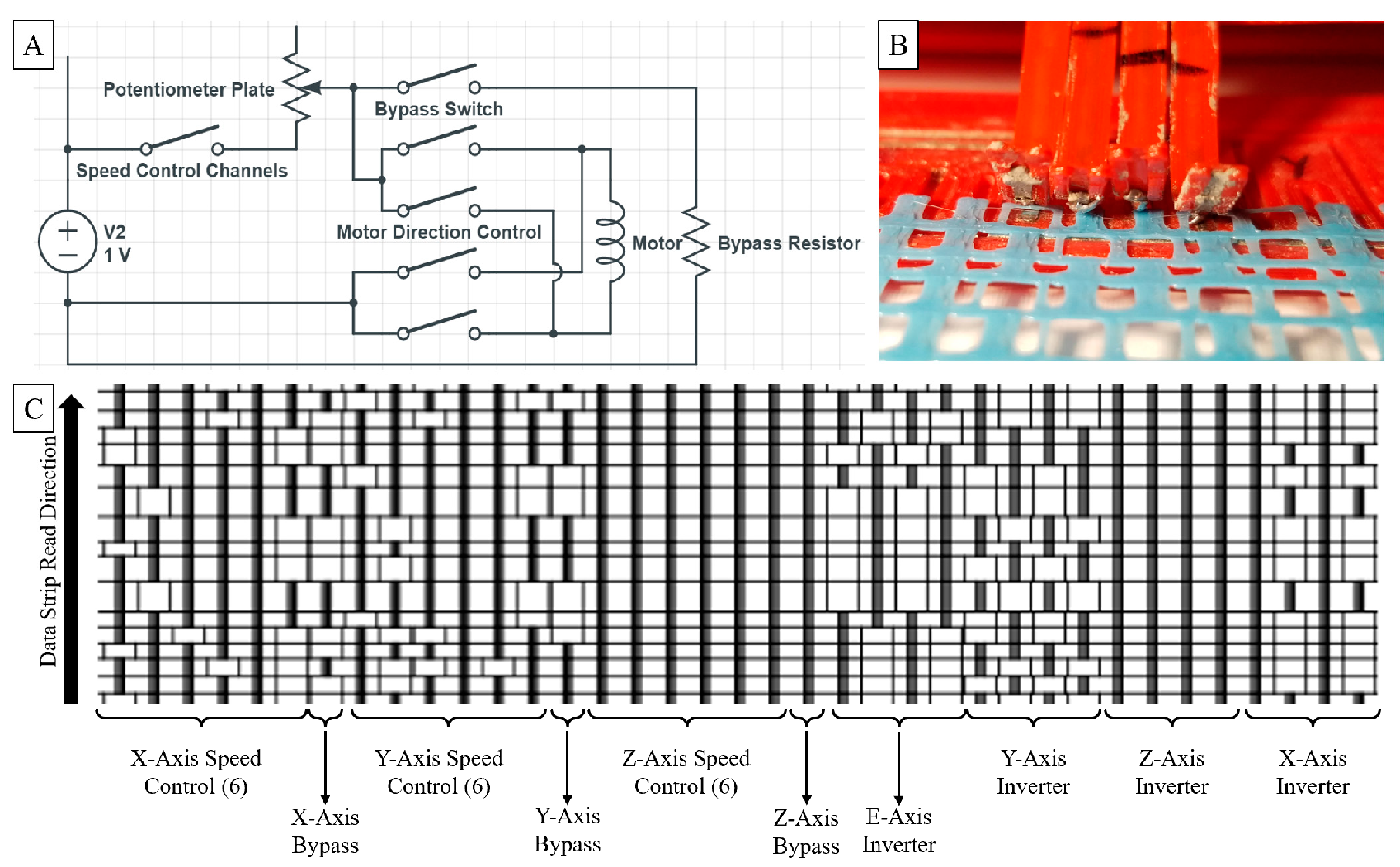

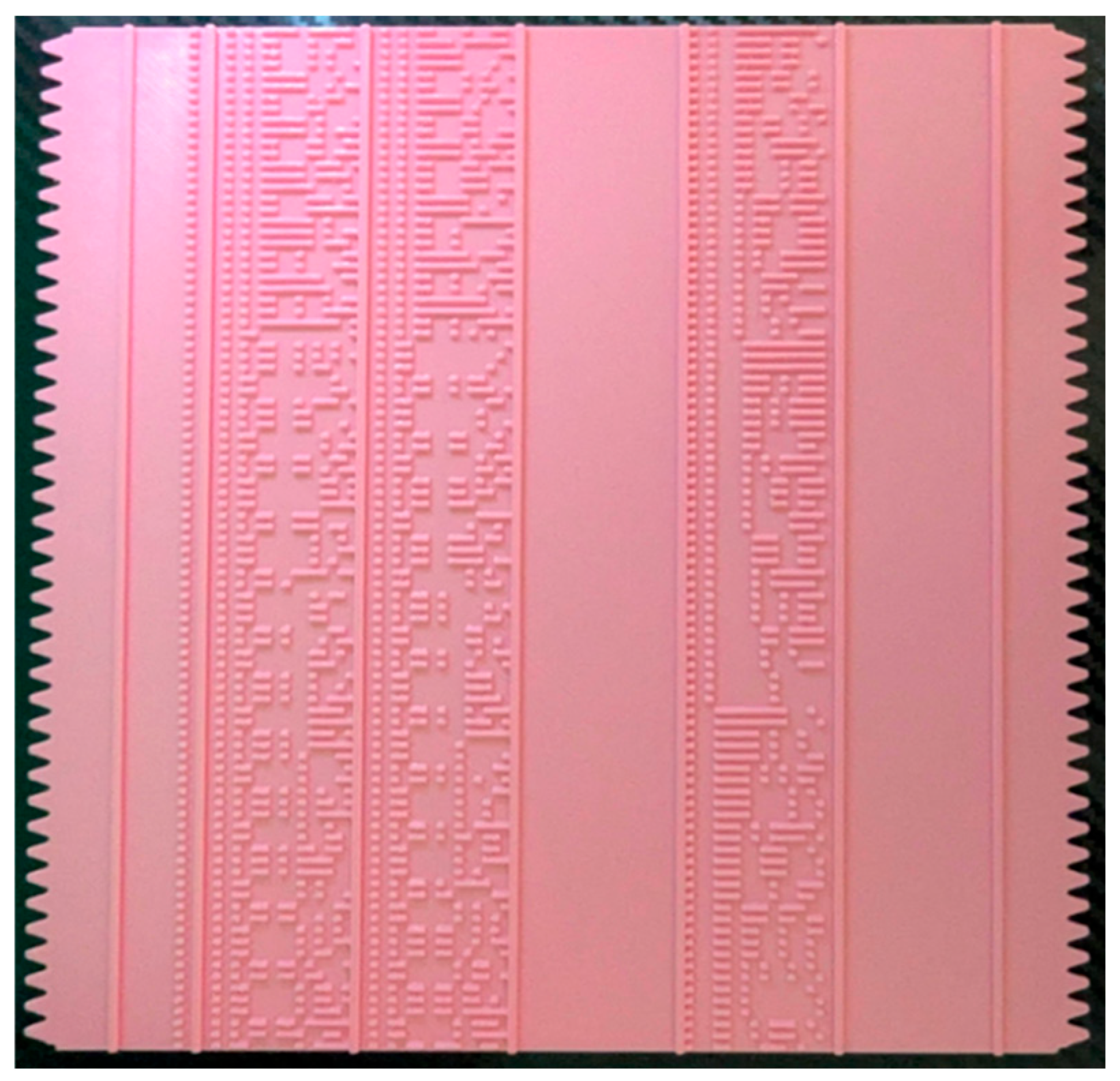

2.3.1. Piano Roll Design

2.3.2. Bump Memory System

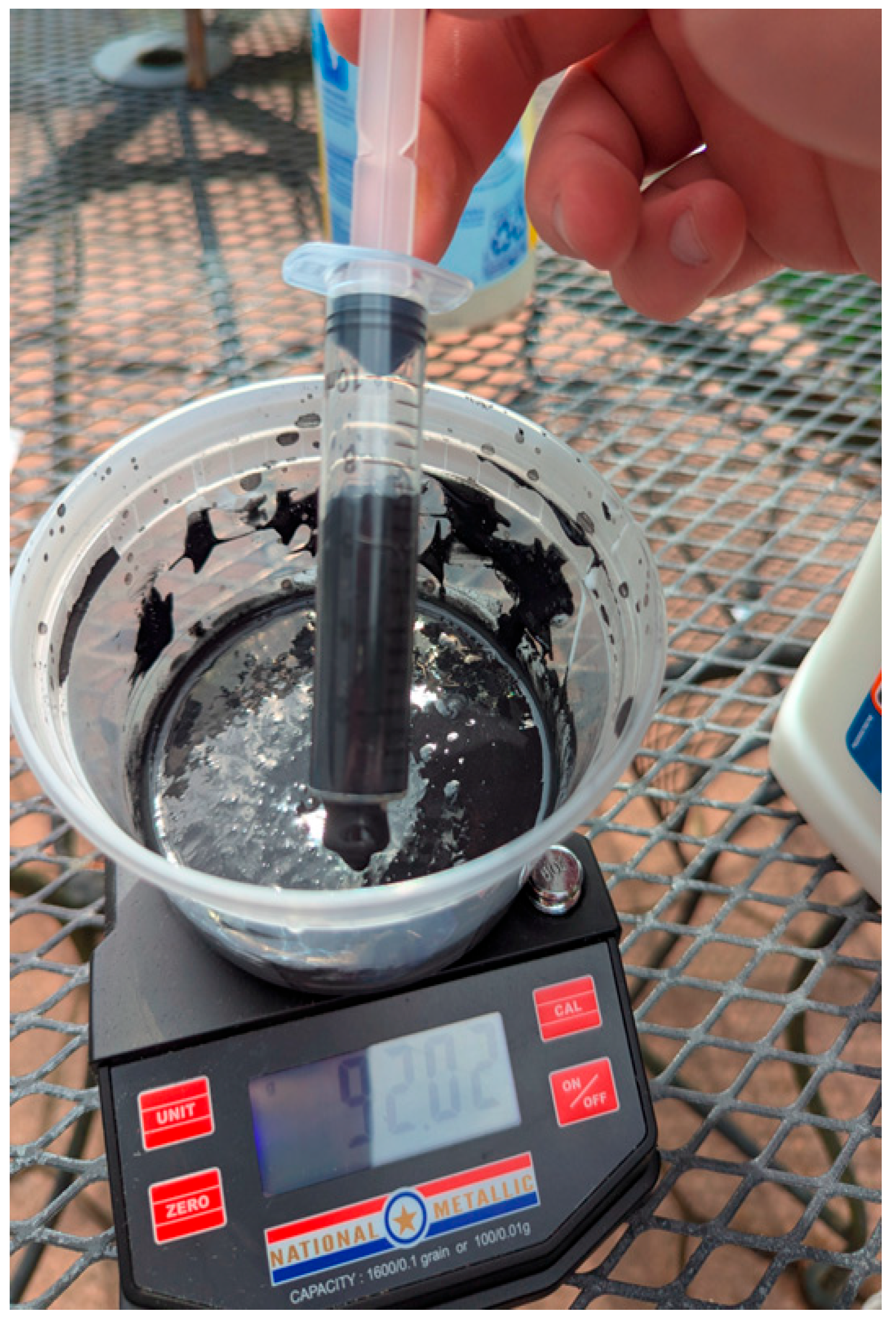

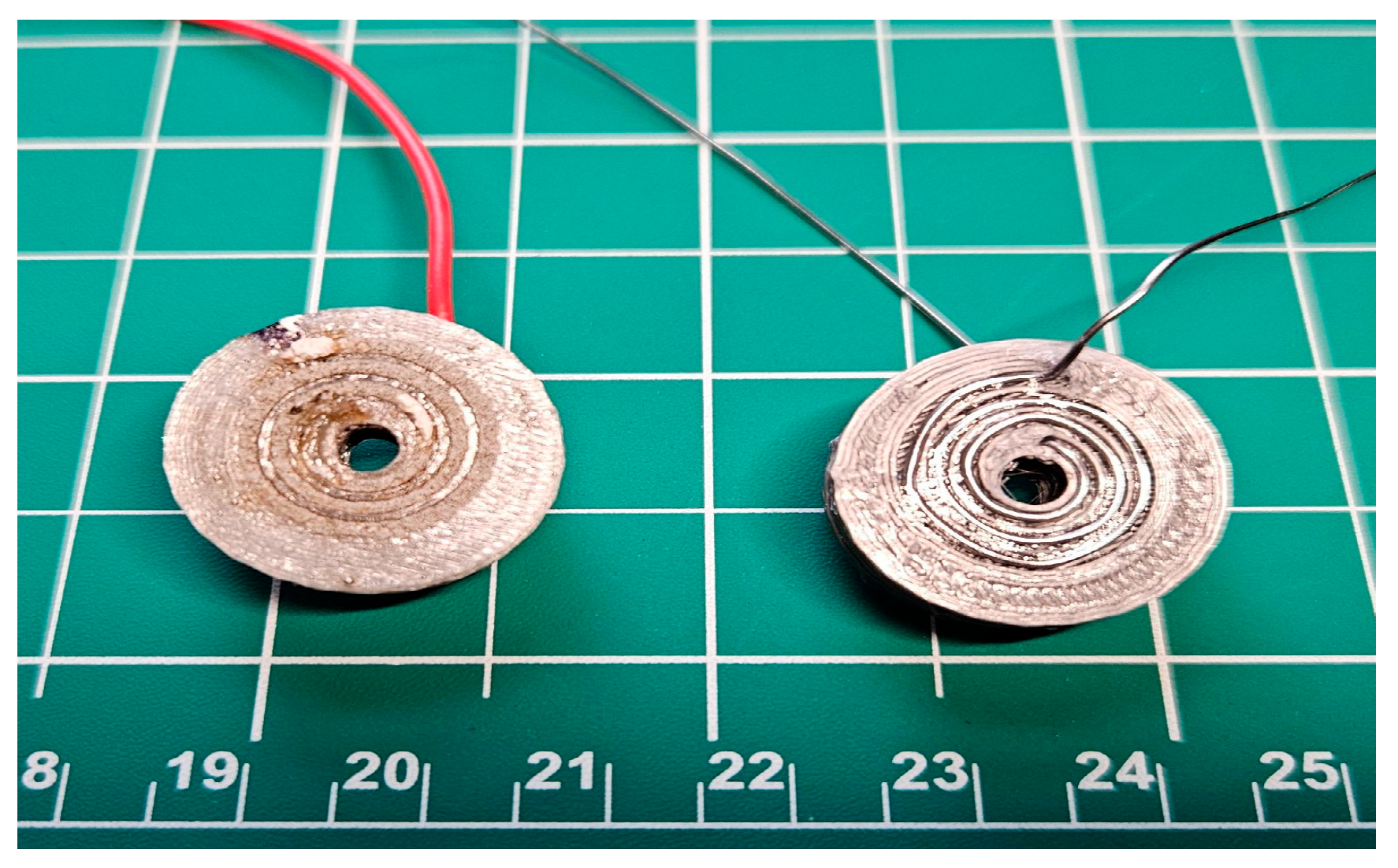

2.3.3. Magnetic Memory

2.4. Actuator Design

2.4.1. Solenoid Design

2.4.2. Motor Design

2.5. Experimental Analysis

2.5.1. General Memory Analysis

2.5.2. Magnet Measurement

2.5.3. Actuator Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overview

3.2. Magnet Characterization

Comparison of Printed Memories

3.3. Solenoid Outcomes

3.4. Motor Outcomes

3.5. Comparative Performance Metrics

| Component | Our System | Commercial Benchmark | Performance Ratio | Critical Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solenoid Energy Transfer | 108 ± 5 μJ | 99 ± 1.5 μJ | 109% | Trace density [0.8mm vs 0.1mm commercial] |

| Motor Torque | 88.1 g-cm | 515 g-cm [29SYT001] | 17% | Coil turns [42 vs 200+ commercial] |

| Motor Speed | 657 rpm | 483 rpm [29SYT001] | 136% | Lower torque compensated by speed |

| Mechanical Memory Density | 1639 bits/g | 8800 bits/g [piano roll] | 19% | Resolution limited by FDM accuracy |

| Magnetic Memory [theoretical] | 5468 bits/g | 10,000+ bits/g [early tape] | 55% | Magnetite distribution variance |

3.6. System Integration and Ecosystem Validation

3.7. Combination in a Fully 3D Printed 3D Printer

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview

4.2. Benefits and Limitations: Path to True Self-Replication

- 1.

- Passive component fabrication: Printable resistors using carbon-loaded filaments (demonstrated elsewhere but not integrated here)

- 2.

- Power systems: Printable batteries or energy harvesting (photovoltaic cells via conductive trace arrays)

- 3.

- Raw material processing: Filament recycling and conductor synthesis from base materials

4.2.1. Piano Roll Memory System

4.2.2. Bump Memory System

4.2.3. Magnetic System

4.3. Actuator Limitations

4.4. Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- J. S. Srai, Kumar ,Mukesh, Graham ,Gary, Phillips ,Wendy, Tooze ,James, Ford ,Simon, Beecher ,Paul, Raj ,Baldev, Gregory ,Mike, Tiwari ,Manoj Kumar, Ravi ,B., Neely ,Andy, Shankar ,Ravi, Charnley ,Fiona, A. and Tiwari, Distributed manufacturing: scope, challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Production Research 54, 6917–6935 [2016].

- L. Dong, P. Kouvelis, Impact of Tariffs on Global Supply Chain Network Configuration: Models, Predictions, and Future Research. M&SOM 22, 25–35 [2020].

- J. Persad, S. Rocke, Multi-material 3D printed electronic assemblies: A review. Results in Engineering 16, 100730 [2022].

- Red Sea Attacks Disrupt Global Trade, IMF [2024]. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/03/07/Red-Sea-Attacks-Disrupt-Global-Trade.

- Helwa, R., & Al-Riffai, P. [2025]. A lifeline under threat: Why the Suez Canal’s security matters for the world. Atlantic Council, 20.

- , A lifeline under threat: Why the Suez Canal’s security matters for the world, Atlantic Council [2025]. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/a-lifeline-under-threat-why-the-suez-canals-security-matters-for-the-world/.

- H. D. Budinoff, J. Bushra, M. Shafae, Community-driven PPE production using additive manufacturing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Survey and lessons learned. J Manuf Syst 60, 799–810 [2021].

- B. Wittbrodt, J. Laureto, B. Tymrak, J. M. Pearce, Distributed manufacturing with 3-D printing: a case study of recreational vehicle solar photovoltaic mounting systems. Journal of Frugal Innovation 1, 1 [2015].

- A. L. Woern, J. M. Pearce, Distributed Manufacturing of Flexible Products: Technical Feasibility and Economic Viability. Technologies 5, 71 [2017].

- D. Thomas, Costs, Benefits, and Adoption of Additive Manufacturing: A Supply Chain Perspective. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 85, 1857–1876 [2016].

- R. Perez-Mañanes, S. G. S. José, M. Desco-Menéndez, I. Sánchez-Arcilla, E. González-Fernández, J. Vaquero-Martín, J. P. González-Garzón, L. Mediavilla-Santos, D. Trapero-Moreno, J. A. Calvo-Haro, Application of 3D printing and distributed manufacturing during the first-wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Our experience at a third-level university hospital. 3D Printing in Medicine 7, 7 [2021].

- S. Ford, T. Minshall, “Defining the Research Agenda for 3D Printing-Enabled Re-distributed Manufacturing” in Advances in Production Management Systems: Innovative Production Management Towards Sustainable Growth, S. Umeda, M. Nakano, H. Mizuyama, H. Hibino, D. Kiritsis, G. von Cieminski, Eds. [Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2015], pp. 156–164.

- T. Rayna, J. West, Where digital meets physical innovation: Reverse salients and the unrealized dreams of 3D printing. Journal of Product Innovation Management 40, 530–553 [2023].

- J. Wiklund, A. Karakoç, T. Palko, H. Yiğitler, K. Ruttik, R. Jäntti, J. Paltakari, A Review on Printed Electronics: Fabrication Methods, Inks, Substrates, Applications and Environmental Impacts. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 5, 89 [2021].

- E. A. Medina, K. Schneider, A. Temmesfeld, J. Csavina-Raison, D. Hutchens, R. Drerup, R. Acosta, J. Ready, S. Sitaraman, S. Turano, C.-W. Chan, X. Song, M. King, B. Faust, S. Kaya, A. Temmesfeld, “Manufacturing Technology [MATES] II. Task Order 0006: Air Force Technology and Industrial Base Research Sub-Task 07: Future Advances in Electronic Materials and Processes-Flexible Hybrid Electronics:“ [Defense Technical Information Center, Fort Belvoir, VA, 2016]; https://doi.org/10.21236/AD1011193.

- E. MacDonald, R. Wicker, Multiprocess 3D printing for increasing component functionality. Science 353, aaf2093 [2016].

- B. Minnick, “A Self-Replicating 3D Printer” [2021]; https://clickprintchem.wordpress.com/2022/05/31/self-replicating-3d-printer-year-3-and-4-review/.

- J. Cañada, H. Kim, L. F. Velásquez-García, Three-dimensional, soft magnetic-cored solenoids via multi-material extrusion. Virtual and Physical Prototyping 19, e2310046 [2024].

- Z. Zhu, H. S. Park, M. C. McAlpine, 3D printed deformable sensors. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba5575 [2020].

- X. Cao, S. Xuan, Y. Gao, C. Lou, H. Deng, X. Gong, 3D Printing Ultraflexible Magnetic Actuators via Screw Extrusion Method. Advanced Science 9, 2200898 [2022].

- X. Cao, S. Xuan, S. Sun, Z. Xu, J. Li, X. Gong, 3D Printing Magnetic Actuators for Biomimetic Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 30127–30136 [2021].

- L. Pujari, S. Manoj, O. K. Gaddikeri, P. Shetty, M. B. Khot, Recent advancements in 3D printing for gear design and analysis: a comprehensive review. Multiscale and Multidiscip. Model. Exp. and Des. 7, 4979–5003 [2024].

- Y. L. Yap, S. L. Sing, W. Y. Yeong, A review of 3D printing processes and materials for soft robotics. Rapid Prototyping Journal 26, 1345–1361 [2020].

- B. Salam, W. L. Lai, L. C. W. Albert, L. B. Keng, “Low temperature processing of copper conductive ink for printed electronics applications” in 2011 IEEE 13th Electronics Packaging Technology Conference, EPTC 2011 [2011], pp. 251–255.

- H. Yuk, B. Lu, S. Lin, K. Qu, J. Xu, J. Luo, X. Zhao, 3D printing of conducting polymers. Nature Communications 11, 1–8 [2020].

- Z. Zhang, H. Zeng, Effects of thermal treatment on poly[ether ether ketone]. Polymer 34, 3648–3652 [1993].

- Q. Song, Y. Chen, P. Hou, P. Zhu, D. Helmer, F. Kotz-Helmer, B. E. Rapp, Fabrication of Multi-Material Pneumatic Actuators and Microactuators Using Stereolithography. Micromachines 14, 244 [2023].

- J. D. Carrico, T. Hermans, K. J. Kim, K. K. Leang, 3D-Printing and Machine Learning Control of Soft Ionic Polymer-Metal Composite Actuators. Sci Rep 9, 17482 [2019].

- Zolfagharian, A. Kaynak, A. Noshadi, A. Z. Kouzani, System identification and robust tracking of a 3D printed soft actuator. Smart Mater. Struct. 28, 075025 [2019].

- N. Peele, T. J. Wallin, H. Zhao, R. F. Shepherd, 3D printing antagonistic systems of artificial muscle using projection stereolithography. Bioinspir. Biomim. 10, 055003 [2015].

- S. Conrad, T. Speck, F. J. Tauber, “Multi-material FDM 3D Printed Arm with Integrated Pneumatic Actuator” in Biomimetic and Biohybrid Systems, A. Hunt, V. Vouloutsi, K. Moses, R. Quinn, A. Mura, T. Prescott, P. F. M. J. Verschure, Eds. [Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022], pp. 27–31.

- B. Lee, Y. Kim, S. Yang, I. Jeong, J. Moon, A low-cure-temperature copper nano ink for highly conductive printed electrodes. Current Applied Physics 9, e157–e160 [2009].

- S. Sundaram, M. Skouras, D. S. Kim, L. Van Den Heuvel, W. Matusik, Topology optimization and 3D printing of multimaterial magnetic actuators and displays. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw1160 [2019].

- H. Yuan, F. Chapelle, J.-C. Fauroux, X. Balandraud, Concept for a 3D-printed soft rotary actuator driven by a shape-memory alloy. Smart Mater. Struct. 27, 055005 [2018].

- Z. Zhang, G. Yang, B. Pan, M. Sun, G. Zhang, H. Chai, H. Wu, S. Jiang, Experimental study and numerical simulation of morphing characteristics of bistable laminates embedded with 3D printed shape memory polymers. Smart Mater. Struct. 33, 055031 [2024].

- C. Zhang, X. Li, L. Jiang, D. Tang, H. Xu, P. Zhao, J. Fu, Q. Zhou, Y. Chen, 3D Printing of Functional Magnetic Materials: From Design to Applications. Advanced Functional Materials 31, 2102777 [2021].

- Z. Xu, X. Wang, F. Chen, K. Chen, Effect of Fumed Silica Nanoparticles on the Performance of Magnetically Active Inks and DIW Printing. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 5, 5794–5804 [2023].

- X. Wei, M.-L. Jin, H. Yang, X.-X. Wang, Y.-Z. Long, Z. Chen, Advances in 3D printing of magnetic materials: Fabrication, properties, and their applications. J Adv Ceram 11, 665–701 [2022].

- G. A. Konov, A. K. Mazeeva, D. V. Masaylo, N. G. Razumov, A. A. Popovich, Exploring 3D printing with magnetic materials: Types, applications, progress, and challenges. Izv. VUZ. Poroshk. Met. 18, 6–19 [2024].

- S. Roh, L. B. Okello, N. Golbasi, J. P. Hankwitz, J. A. -C. Liu, J. B. Tracy, O. D. Velev, 3D-Printed Silicone Soft Architectures with Programmed Magneto-Capillary Reconfiguration. Adv Materials Technologies 4, 1800528 [2019].

- D. Kent, D. C. Worledge, A new spin on magnetic memories. Nature Nanotech 10, 187–191 [2015].

- R. Bradshaw, C. Schroeder, Fifty years of IBM innovation with information storage on magnetic tape. IBM J. Res. & Dev. 47, 373–383 [2003.

- https://www.ametekinterconnect.com/-/media/ametek-ecp/v2/files/cw_datasheets_sds_cfsi/datasheets/sn63pb37%20data%20sheet.pdf?la=en. https://www.ametekinterconnect.com/-/media/ametek-ecp/v2/files/cw_datasheets_sds_cfsi/datasheets/sn63pb37%20data%20sheet.pdf?la=en.

- F. Friedlaender, J. McMillen, A magnetic core analog memory. IEEE Trans. Magn. 3, 463–466 [1967].

| Average Values for Sample Set | Piano roll | Bump | Magnetic [estimated] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of G-code file [bits] |

17672 | 17672 | 17672 |

| Mass of full printed model [g] |

10.79 | 87.77 | 3.23 |

| Volume of full printed model [mm3] | 8,659.01 | 70,778.41 | 713.51 |

| Information mass density [bits/g] | 1639.26 | 201.35 | 5,468.22 |

| Information volume density [bits/mm3] | 0.69 | 0.14 | 24.77 |

| Information length density [bits/mm] | 40.59 | 79.34 | 31.5 |

| Can decode without microprocessors | Yes | No | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).