Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

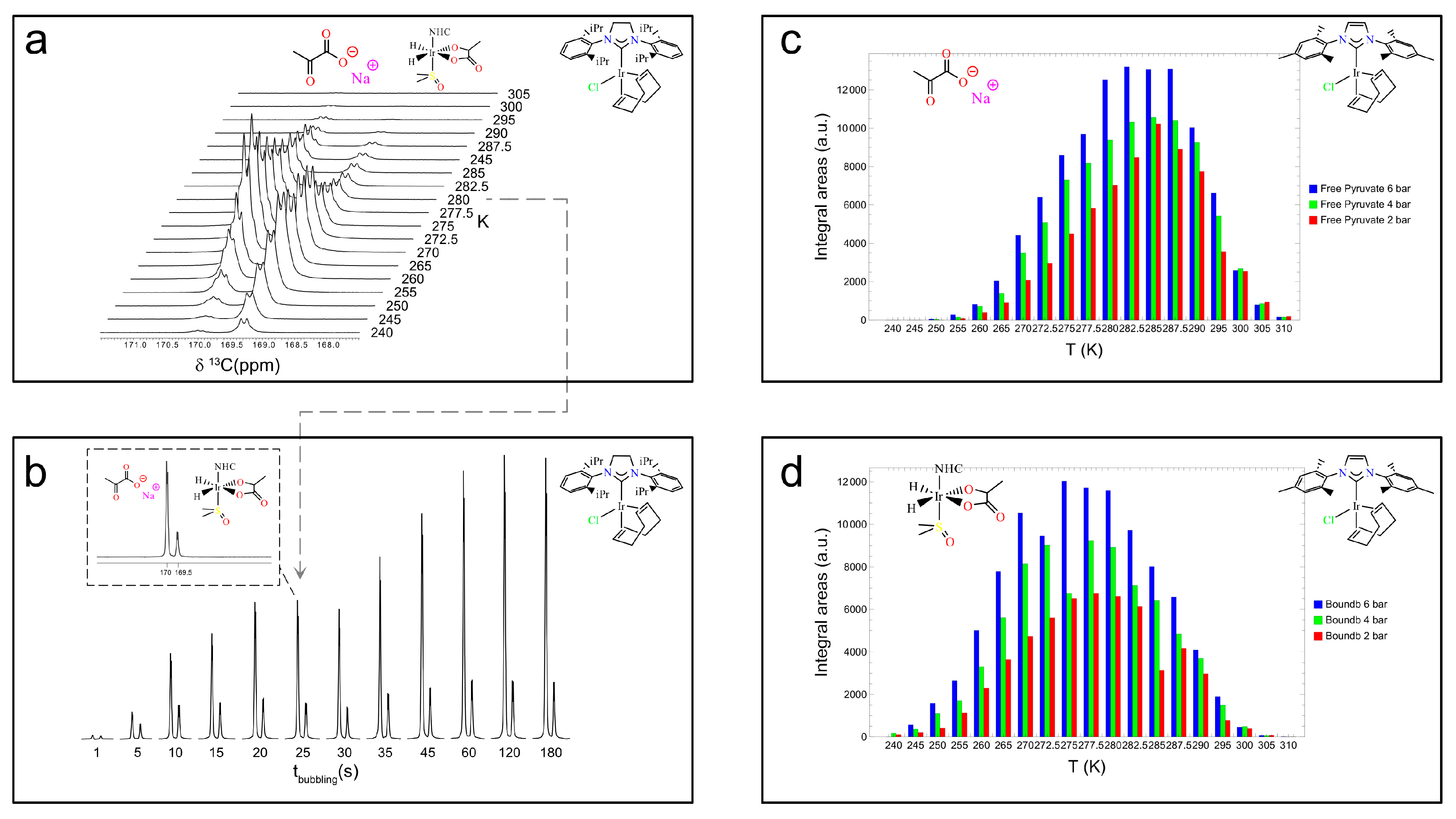

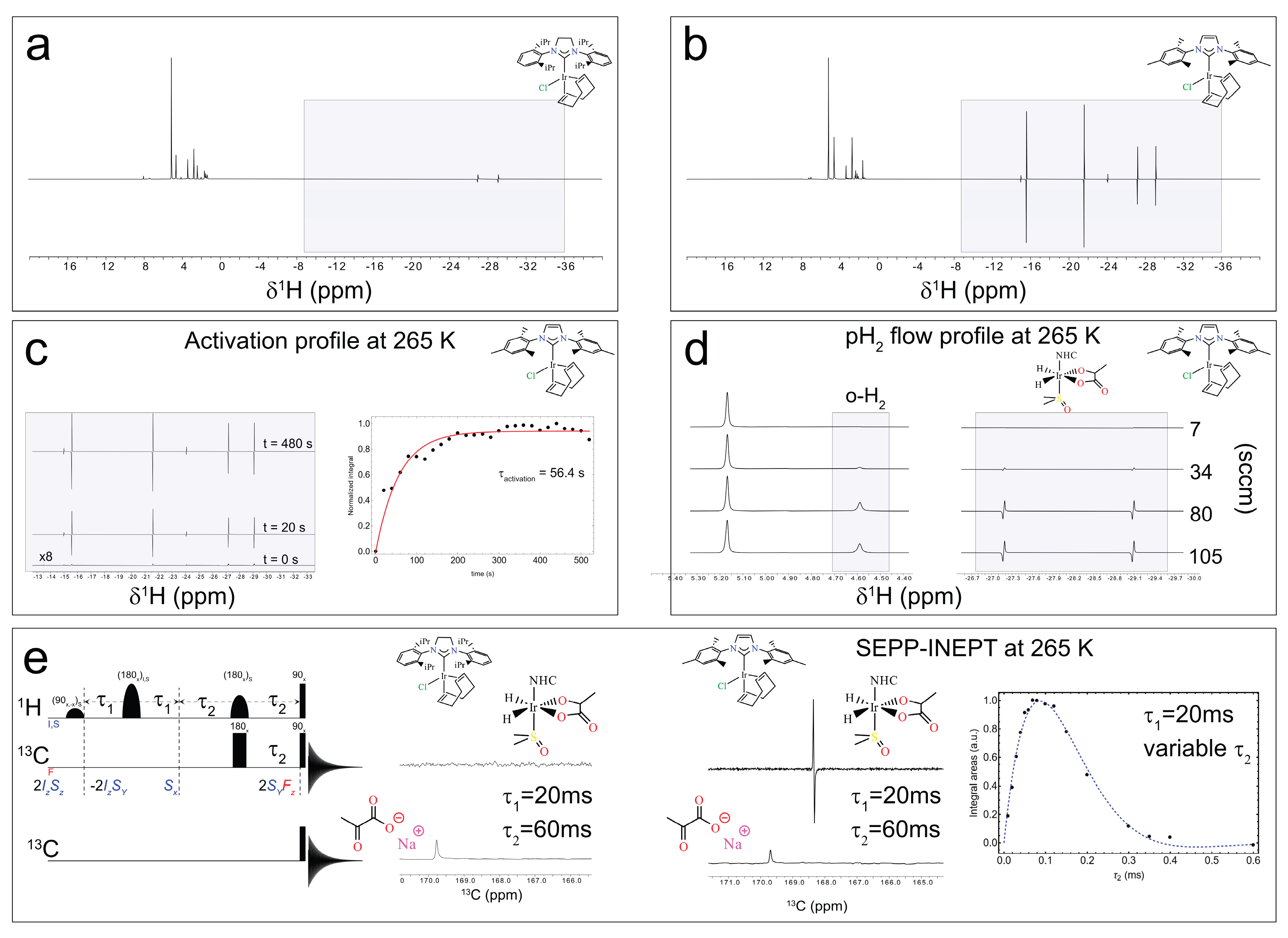

Parahydrogen-induced hyperpolarization (PHIP) was introduced nearly four decades ago as an elegant solution to one of the fundamental limitations of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) — its notoriously low sensitivity. By converting the spin order of parahydrogen into nuclear spin polarization, NMR signals can be boosted by several orders of magnitude. Here we present a portable, compact and cost-effective setup that brings PHIP and Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange (SABRE) experiments within easy reach, operating seamlessly across ultra-low-field (0–10 μT) and high-field (>1 T) conditions at 50% parahydrogen enrichment. The system provides precise control over bubbling pressure, temperature, and gas flow, enabling systematic studies of how these parameters shape hyperpolarization performance. Using the benchmark Ir-IMes catalyst, we explore the catalyst activation time and response to parahydrogen flow and pressure. Polarization transfer experiments from hydrides to [1-13C]pyruvate leading to the estimation of heteronuclear J-coupling are also presented. We further demonstrate the use of Chloro(1,5-cyclooctadiene)[1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazolidin-2-ylidene]iridium(I) (Ir-SIPr), a recently introduced catalyst that can also be used for pyruvate hyperpolarization. The proposed design is robust, reproducible, and easy to implement in any laboratory, widening the route to explore and expand the capabilities of parahydrogen-based hyperpolarization.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

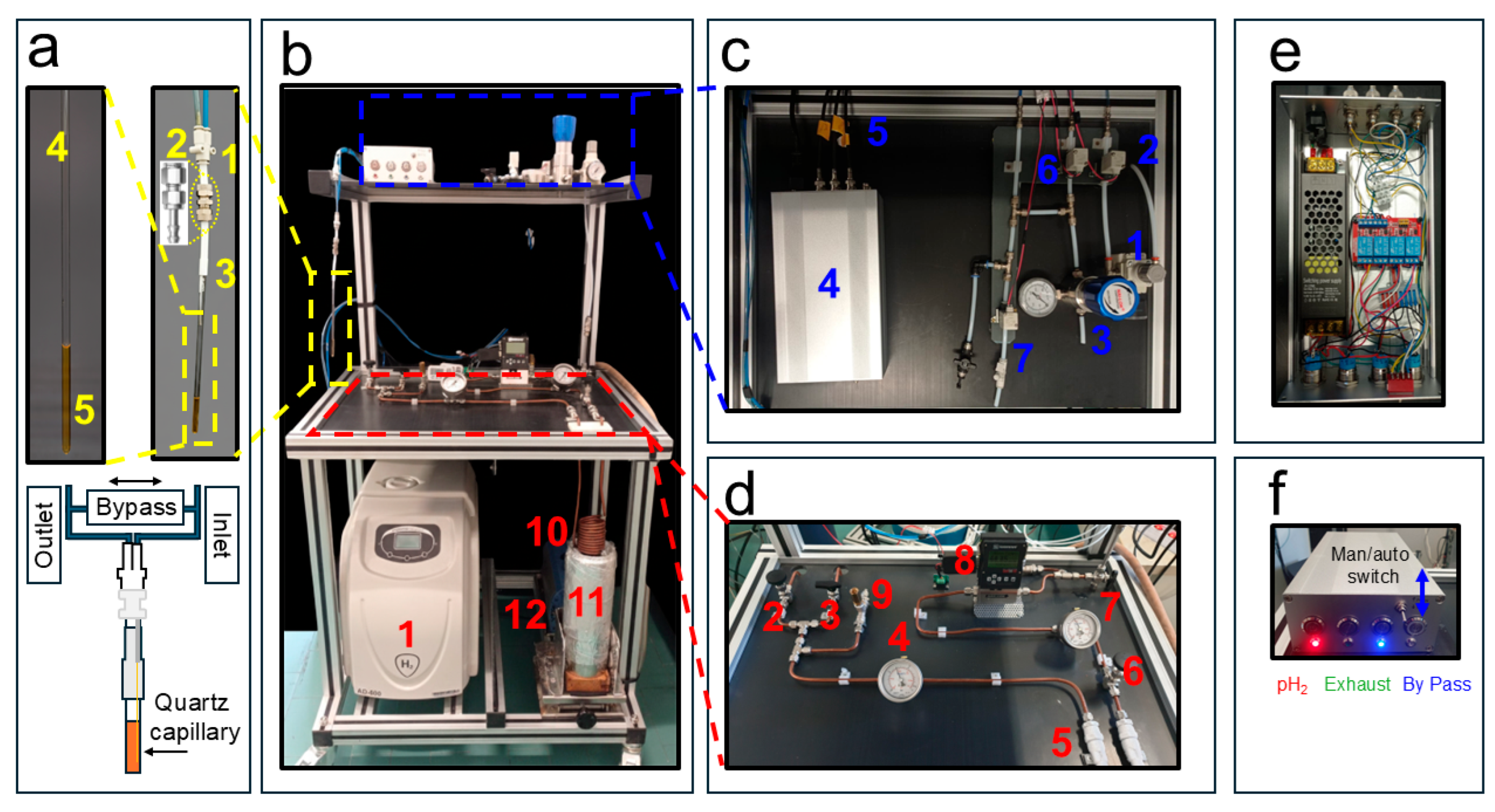

2. Description of the System

2.1. Parahydrogen Generator

2.2. The pH2 Distribution System

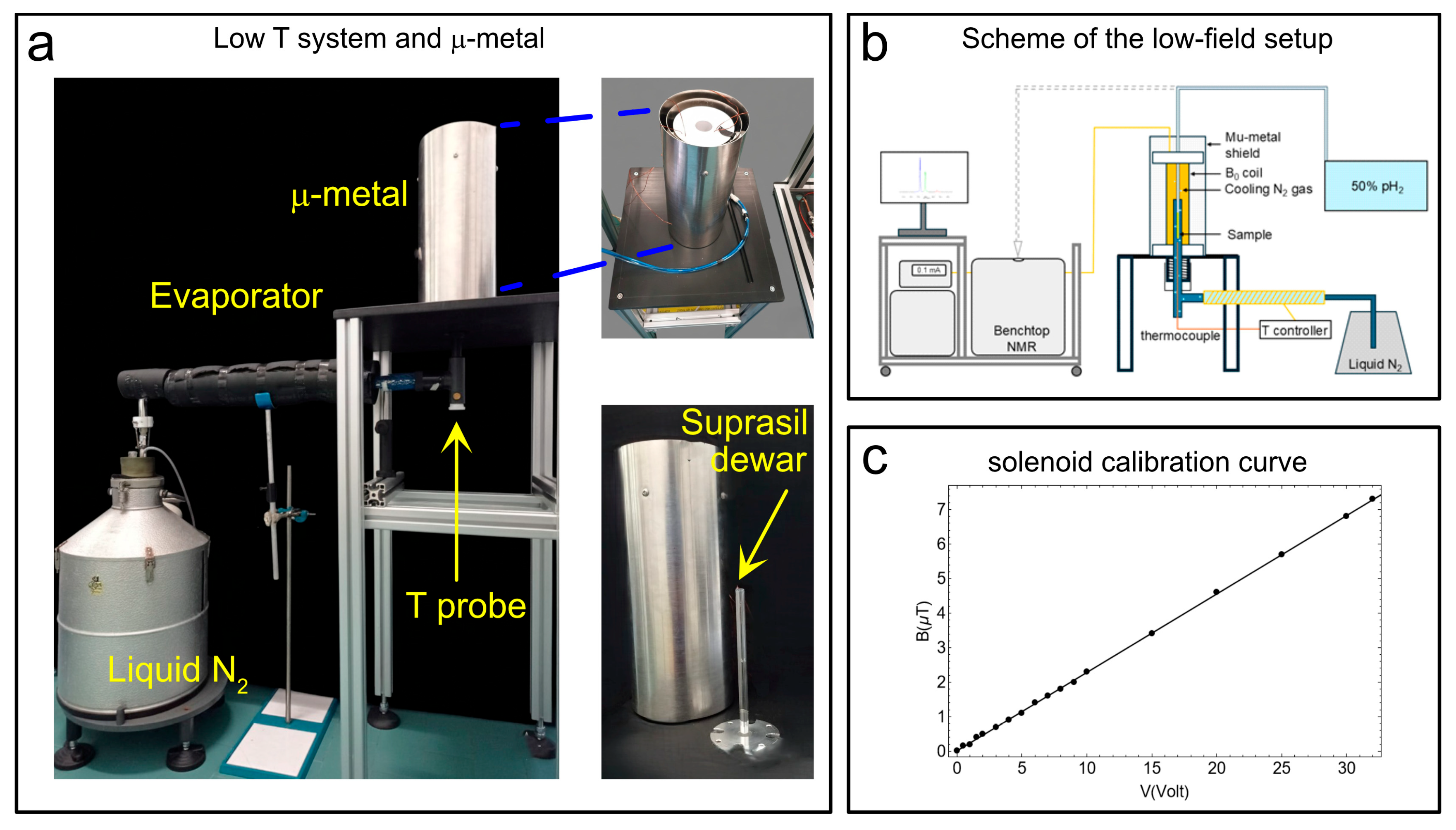

2.3. The Temperature Control unit and Mu-Metal for SABRE-SHEATH Experiments

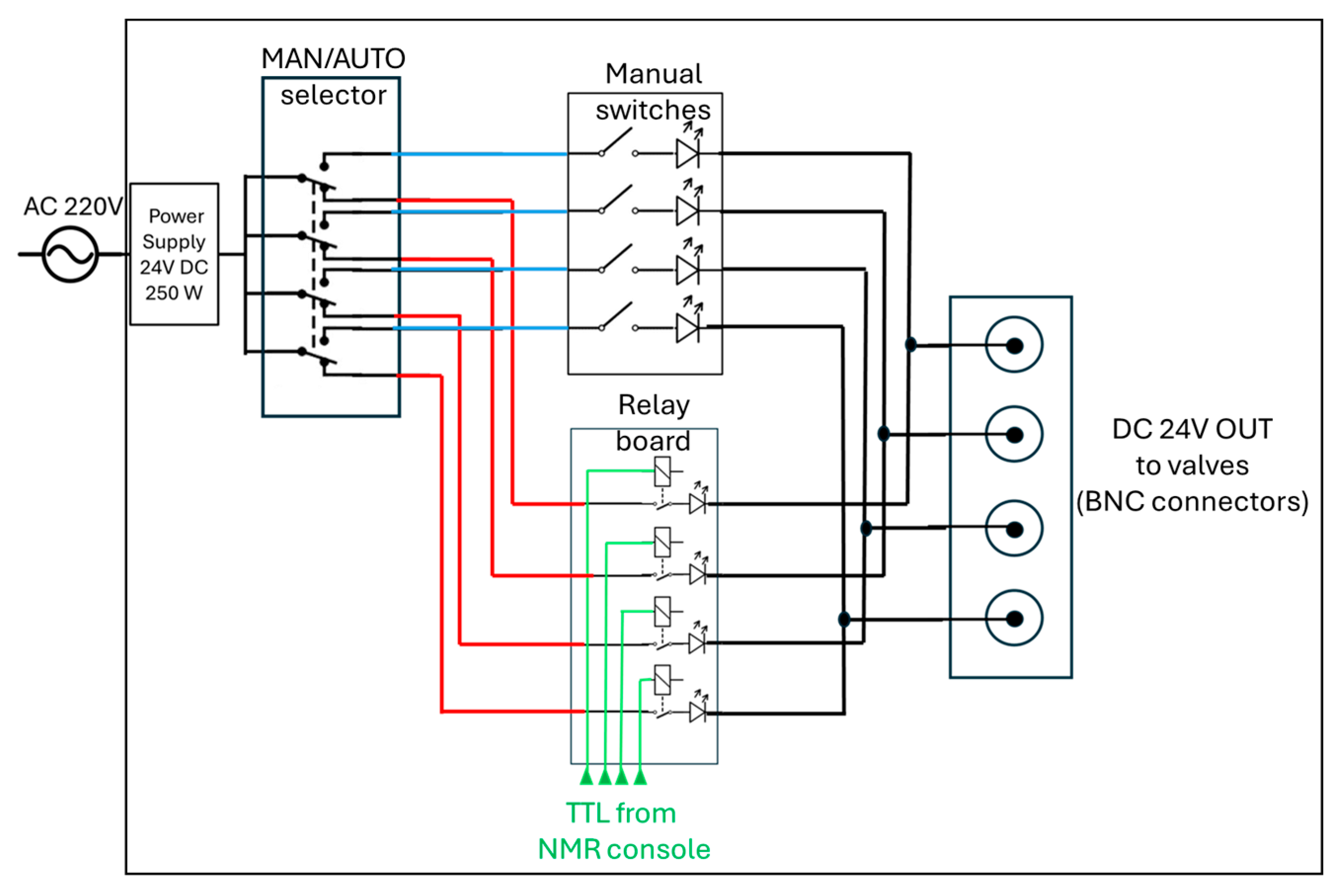

2.4. How to Cable the for Automatic Parahydrogen Experiments at High Magnetic Fields

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experiments at 1.4 T with a Benchtop NMR and at 9.4 T

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHIP | Parahydrogen Induced Hyper Polarization |

| SABRE | Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange |

| DNP | Dynamic Nuclear Polarization |

Appendix A. Estimated Component Costs for the Parahydrogen Generator and Control System

| ITEM | NAME | Q. | ESTIMATED PRICE/€ |

| H2 GENERATOR | AD-600 Cinel SRL | 1 | 6000.00 |

| Iron(III) oxide catalyst | Merck, 371254-50G, 30–50 mesh, CAS 20344-49-4 | 1 | 120.00 |

| LN2 Dewar | ISOTHERM DSS 2000 | 1 | 430.00 |

| Mu-metal Shield | Zero gauss chamber, model: ZG-100-300-3-0 | 1 | 3800.00 |

| Back pressure regulator | ROMETEC SRL | 1 | 500.00 |

| Mass Flow Controller | Sierra Instruments C100 | 1 | 2300.00 |

| Portable H2 gas detector | RS COMPONENTS - RS GD38 | 1 | 150.00 |

| Filters M6A-F4L-50-SS | RS COMPONENTS | 2 | 250.00 |

| Solenoid valves | SMC SMVDW20HA | 6 | 180.00 |

| Safety relief valve | S-Lok SRV30-S-6M | 1 | 160.00 |

| Ball valve | S-Lok SBV1-S-6M | 2 | 150.00 |

| Tube fitting | S-Lok SNV2-S-6M | 2 | 130.00 |

| Two-way ball valve | S-Lok SBV1-3B-S-6M | 1 | 90.00 |

| Soft copper | 4 mm O.D. -15 m- | 1 | 25.00 |

| Soft copper | 6 mm O.D. -15 m- | 1 | 40.00 |

| SMC pneumatic fitting | RS COMPONENTS - 771-5920 | 10 | 30.00 |

| Flow regulators | RS COMPONENTS – 748-0712 | 10 | 90.00 |

| Pressure gauge | MANS063010BR04NG | 4 | 80.00 |

| Pressure regulators | RS COMPONENTS – 204-0053 | 4 | 150.00 |

| Nickel-plated brass compression fittings | TECNOCAM | 10 | 20.00 |

| Capillary fiber | TUBING .010" ID SILICA 1=10M | 1 | 120.00 |

| Tubing | PTFE, Polyurethane, nylon | 1 | 100.00 |

| Push in fittings | RS COMPONENTS 121-6243 | 1 | 35.00 |

| Push in fittings | RS COMPONENTS 364-190 | 1 | 40.00 |

| Relays | DC 24 V 4-Channel Relay Module with Optocoupler Isolation | 1 | 10.00 |

| Power supply | 24V, 250 W V-TAC 3273 | 1 | 25.00 |

| Push Buttons with LED | 16 mm Self-Locking Push Button Switch, 12–24 V, 3 A | 4 | 50.00 |

| Cables and other components | 1 | 150.00 | |

| TOTAL | 15260.00 - (including hydrogen generator; excluding NMR hardware) |

Appendix B. Pulse Sequence for Automated Bubbling and Acquisition

| ;zgPHIP.gs : pulse sequence to perform automatized bubbling and acquisition | |

| ;avance-version (2/10/18) | |

| ;$CLASS=HighRes | |

| ;$DIM=1D | |

| ;$TYPE= | |

| ;$SUBTYPE= | |

| ;$COMMENT= | |

| #include <Avance.incl> | |

| #include <Delay.incl> | |

| #include <Grad.incl> | |

| "p2=p1*2" | |

| "p4=p3*2" | |

| ; Definitions | |

| ;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;; | |

| define delay dByPass | |

| "dByPass=cnst2" | |

| define delay dPressurization | |

| "dPressurization=cnst3" | |

| define delay dBubbling | |

| "dBubbling=cnst4" | |

| define delay dExhaust | |

| "dExhaust=cnst5" | |

| define delay dStabilization | |

| "dStabilization=cnst6" | |

| ;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;; | |

| ; Pulse sequence | |

| 1 ze | |

| 2 30m | |

| d1 | |

| ; Operations at the switch box | |

| TTL1_HIGH | ; Set the "By Pass" valve to off |

| TTL2_HIGH | ; Set the "pH2" valve to off |

| TTL3_HIGH | ; Set the "Exhaust" valve to off |

| TTL4_HIGH | ; Set the "N2" valve to off |

| dByPass TTL1_LOW | ; Activate "By Pass Valve" |

| 2s | |

| dPressurization TTL2_LOW | ; Pressurization with pH2 |

| dBubbling TTL1_HIGH | ; Bubbling Period |

| TTL1_LOW | ; Stop bubbling |

| 1s | |

| TTL2_HIGH | ; Stop pH2 |

| ;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;; | |

| dStabilization | ; Stabilization after bubbling |

| 4u pl1:f1 | ;power on F1 |

| (p1 ph1):f1 | |

| go=2 ph31 | |

| 30m mc #0 to 2 F0(zd) | |

| 100m | |

| dExhaust TTL3_LOW | ; Release pressure |

| TTL3_HIGH | |

| TTL1_HIGH | |

| exit | |

| ph1 = 1 | |

| ph31 = 0 | |

| ;pl1 : f1 channel - power level for pulse (default) HETERONUCLEAR | |

| ;pl2 : f2 channel - power level for pulse (default) PROTON | |

| ;p1 : f1 channel - 90 degree high power pulse HETERONUCLEAR | |

| ;p2 : f1 channel - 180 degree high power pulse HETERONUCLEAR | |

| ;p3 : f2 channel - 90 degree high power pulse PROTON | |

| ;p4 : f2 channel - 180 degree high power pulse PROTON | |

| ;d1 : relaxation delay | |

| ;cnst2 : switch on ByPass Valve (1s is OK) | |

| ;cnst3 : Pressurization of the system (>120s) | |

| ;cnst4 : Bubbling time | |

| ;cnst5 : Exhaust time | |

| ;cnst6 : Stabilization after bubbling | |

| Comments: | |

References

- Luchinat, E.; Cremonini, M.; Banci, L. Radio Signals from Live Cells: The Coming of Age of In-Cell Solution NMR. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 9267–9306. [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, D.; Sasaki, A.; Ikeya, T.; Hamatsu, J.; Hanashima, T.; Mishima, M.; Yoshimasu, M.; Hayashi, N.; Mikawa, T.; Wälchli, M.; et al. Protein structure determination in living cells by in-cell NMR spectroscopy. Nature 2009, 458, 102–105. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, F.A.; Bohndiek, S.E.; Kettunen, M.I.; Lewis, D.Y.; Soloviev, D.; Brindle, K.M. Hyperpolarized 13C MRI and PET: In Vivo Tumor Biochemistry. J. Nucl. Med. 2011, 52, 1333–1336. [CrossRef]

- Abragam A. Principles of nuclear magnetism. Clarendon Press, Oxford; 1961.

- Gadian, D.G.; Panesar, K.S.; Linde, A.J.P.; Horsewill, A.J.; Köckenberger, W.; Owers-Bradley, J.R. Preparation of highly polarized nuclear spin systems using brute-force and low-field thermal mixing. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 5397–5402. [CrossRef]

- Owers-Bradley JR, Horsewill AJ, Peat DT, Goh KSK, Gadian DG. High polarization of nuclear spins mediated by nanoparticles at millikelvin temperatures. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2013;15(25):10413.

- Hirsch, M.L.; Kalechofsky, N.; Belzer, A.; Rosay, M.; Kempf, J.G. Brute-Force Hyperpolarization for NMR and MRI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8428–8434. [CrossRef]

- Peat, D.T.; Hirsch, M.L.; Gadian, D.G.; Horsewill, A.J.; Owers-Bradley, J.R.; Kempf, J.G. Low-field thermal mixing in [1-13C] pyruvic acid for brute-force hyperpolarization. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 19173–19182. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, H.; Moskau, D.; Spraul, M. Cryogenically cooled probes—a leap in NMR technology. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2005, 46, 131–155. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.J.; Larive, C.K. Could smaller really be better? Current and future trends in high-resolution microcoil NMR spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 402, 61–68. [CrossRef]

- Overhauser AW. Polarization of Nuclei in Metals. Phys Rev. 1953 Oct 15;92(2):411–5.

- Carver, T.R.; Slichter, C.P. Polarization of Nuclear Spins in Metals. Phys. Rev. B 1953, 92, 212–213. [CrossRef]

- Eills, J.; Budker, D.; Cavagnero, S.; Chekmenev, E.Y.; Elliott, S.J.; Jannin, S.; Lesage, A.; Matysik, J.; Meersmann, T.; Prisner, T.; et al. Spin Hyperpolarization in Modern Magnetic Resonance. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 1417–1551. [CrossRef]

- Henstra, A.; Dirksen, P.; Wenckebach, W. Enhanced dynamic nuclear polarization by the integrated solid effect. Phys. Lett. A 1988, 134, 134–136. [CrossRef]

- Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Fridlund, B.; Gram, A.; Hansson, G.; Hansson, L.; Lerche, M.H.; Servin, R.; Thaning, M.; Golman, K. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of > 10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10158–10163. [CrossRef]

- Wenckebach WT. The Solid Effect. Appl Magn Reson. 2008 Aug;34(3–4):227.

- Lesage, A.; Lelli, M.; Gajan, D.; Caporini, M.A.; Vitzthum, V.; Miéville, P.; Alauzun, J.; Roussey, A.; Thieuleux, C.; Mehdi, A.; et al. Surface Enhanced NMR Spectroscopy by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15459–15461. [CrossRef]

- Jannin, S.; Bornet, A.; Colombo, S.; Bodenhausen, G. Low-temperature cross polarization in view of enhancing dissolution Dynamic Nuclear Polarization in NMR. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2011, 517, 234–236. [CrossRef]

- Corzilius B. Theory of solid effect and cross effect dynamic nuclear polarization with half-integer high-spin metal polarizing agents in rotating solids. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2016;18(39):27190–204.

- Wenckebach WTh. Dynamic nuclear polarization via thermal mixing: Beyond the high temperature approximation. J Magn Reson. 2017 Apr;277:68–78.

- Bowers, C.R.; Weitekamp, D.P. Transformation of Symmetrization Order to Nuclear-Spin Magnetization by Chemical Reaction and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 2645–2648. [CrossRef]

- Bowers CR, Weitekamp DP. Para-Hydrogen and Synthesis Allow Dramatically Enhanced Nuclear Alignment. J Am Chem Soc. 1987 Sept 2;109(18):5541–2.

- Natterer J, Bargon J. Parahydrogen induced polarization. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 1997 Nov;31(4):293–315.

- Koptyug, I.V.; Kovtunov, K.V.; Burt, S.R.; Anwar, M.S.; Hilty, C.; Han, S.-I.; Pines, A.; Sagdeev, R.Z. para-Hydrogen-Induced Polarization in Heterogeneous Hydrogenation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 5580–5586. [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.W.; Aguilar, J.A.; Atkinson, K.D.; Cowley, M.J.; Elliott, P.I.P.; Duckett, S.B.; Green, G.G.R.; Khazal, I.G.; López-Serrano, J.; Williamson, D.C. Reversible Interactions with para-Hydrogen Enhance NMR Sensitivity by Polarization Transfer. Science 2009, 323, 1708–1711. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, K.D.; Cowley, M.J.; Elliott, P.I.P.; Duckett, S.B.; Green, G.G.R.; López-Serrano, J.; Whitwood, A.C. Spontaneous Transfer of Parahydrogen Derived Spin Order to Pyridine at Low Magnetic Field. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13362–13368. [CrossRef]

- Kauczor, H.-U.; Surkau, R.; Roberts, T. MRI using hyperpolarized noble gases. Eur. Radiol. 1998, 8, 820–827. [CrossRef]

- Meier B, Dumez JN, Stevanato G, Hill-Cousins JT, Roy SS, Hakansson P, et al. Long-lived nuclear spin states in methyl groups and quantum-rotor-induced polarization. J Am Chem Soc. 2013 Dec 18;135(50):18746–9.

- Dumez, J.-N.; Vuichoud, B.; Mammoli, D.; Bornet, A.; Pinon, A.C.; Stevanato, G.; Meier, B.; Bodenhausen, G.; Jannin, S.; Levitt, M.H. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of Long-Lived Nuclear Spin States in Methyl Groups. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 3549–3555. [CrossRef]

- Corzilius, B.; Smith, A.A.; Barnes, A.B.; Luchinat, C.; Bertini, I.; Griffin, R.G. High-Field Dynamic Nuclear Polarization with High-Spin Transition Metal Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 5648–5651. [CrossRef]

- Corzilius B. Theory of solid effect and cross effect dynamic nuclear polarization with half-integer high-spin metal polarizing agents in rotating solids. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2016 Oct 5;18(39):27190–204.

- Corzilius, B. High-Field Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2020, 71, 143–170. [CrossRef]

- Jardón-Álvarez, D.; Leskes, M. Metal ions based dynamic nuclear polarization: MI-DNP. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2023, 138-139, 70–104. [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Jabbour, R.; Sadasivan, S.V.; Alsaghir, S.; Alhussni, A.; Jhamnani, M.; Equbal, A. Dynamic nuclear polarization: State of the art and future possibilities with light activation. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2025, 6. [CrossRef]

- Albers, M.J.; Bok, R.; Chen, A.P.; Cunningham, C.H.; Zierhut, M.L.; Zhang, V.Y.; Kohler, S.J.; Tropp, J.; Hurd, R.E.; Yen, Y.-F.; et al. Hyperpolarized 13C Lactate, Pyruvate, and Alanine: Noninvasive Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer Detection and Grading. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 8607–8615. [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, A.; Hyacinthe, J.-N.; Cheng, T.; Eichhorn, T.R.; Boero, G.; Roussel, C.; van der Klink, J.J.; Comment, A. Photoinduced Nonpersistent Radicals as Polarizing Agents for X-Nuclei Dissolution Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 22632–22639. [CrossRef]

- Reineri, F.; Boi, T.; Aime, S. ParaHydrogen Induced Polarization of 13C carboxylate resonance in acetate and pyruvate. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5858–5858. [CrossRef]

- Di Matteo, G.; Bondar, O.; Carrera, C.; Cavallari, E.; Mishra, S.; Reineri, F. Improving the Catalyst Efficiency for Hyperpolarization of Pyruvate Derivatives by Means of Hydrogenative PHIP. ChemMedChem 2025, 20, e202500379. [CrossRef]

- Kiryutin, A.S.; Sauer, G.; Hadjiali, S.; Yurkovskaya, A.V.; Breitzke, H.; Buntkowsky, G. A highly versatile automatized setup for quantitative measurements of PHIP enhancements. J. Magn. Reson. 2017, 285, 26–36. [CrossRef]

- Birchall JR, Coffey AM, Goodson BM, Chekmenev EY. High-Pressure Clinical-Scale 87% Parahydrogen Generator. Anal Chem. 2020 Dec 1;92(23):15280–4.

- Nantogma, S.; Joalland, B.; Wilkens, K.; Chekmenev, E.Y. Clinical-Scale Production of Nearly Pure (>98.5%) Parahydrogen and Quantification by Benchtop NMR Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 3594–3601. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, B.; Joalland, B.; Meersman, C.; Ettedgui, J.; Swenson, R.E.; Krishna, M.C.; Nikolaou, P.; Kovtunov, K.V.; Salnikov, O.G.; Koptyug, I.V.; et al. Low-Cost High-Pressure Clinical-Scale 50% Parahydrogen Generator Using Liquid Nitrogen at 77 K. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 8476–8483. [CrossRef]

- Ellermann, F.; Pravdivtsev, A.; Hövener, J.-B. Open-source, partially 3D-printed, high-pressure (50-bar) liquid-nitrogen-cooled parahydrogen generator. Magn. Reson. 2021, 2, 49–62. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.B.; Bowers, C.R.; Buckenmaier, K.; Chekmenev, E.Y.; de Maissin, H.; Eills, J.; Ellermann, F.; Glöggler, S.; Gordon, J.W.; Knecht, S.; et al. Instrumentation for Hydrogenative Parahydrogen-Based Hyperpolarization Techniques. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 479–502. [CrossRef]

- Duchowny, A.; Denninger, J.; Lohmann, L.; Theis, T.; Lehmkuhl, S.; Adams, A. SABRE Hyperpolarization with up to 200 bar Parahydrogen in Standard and Quickly Removable Solvents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2465. [CrossRef]

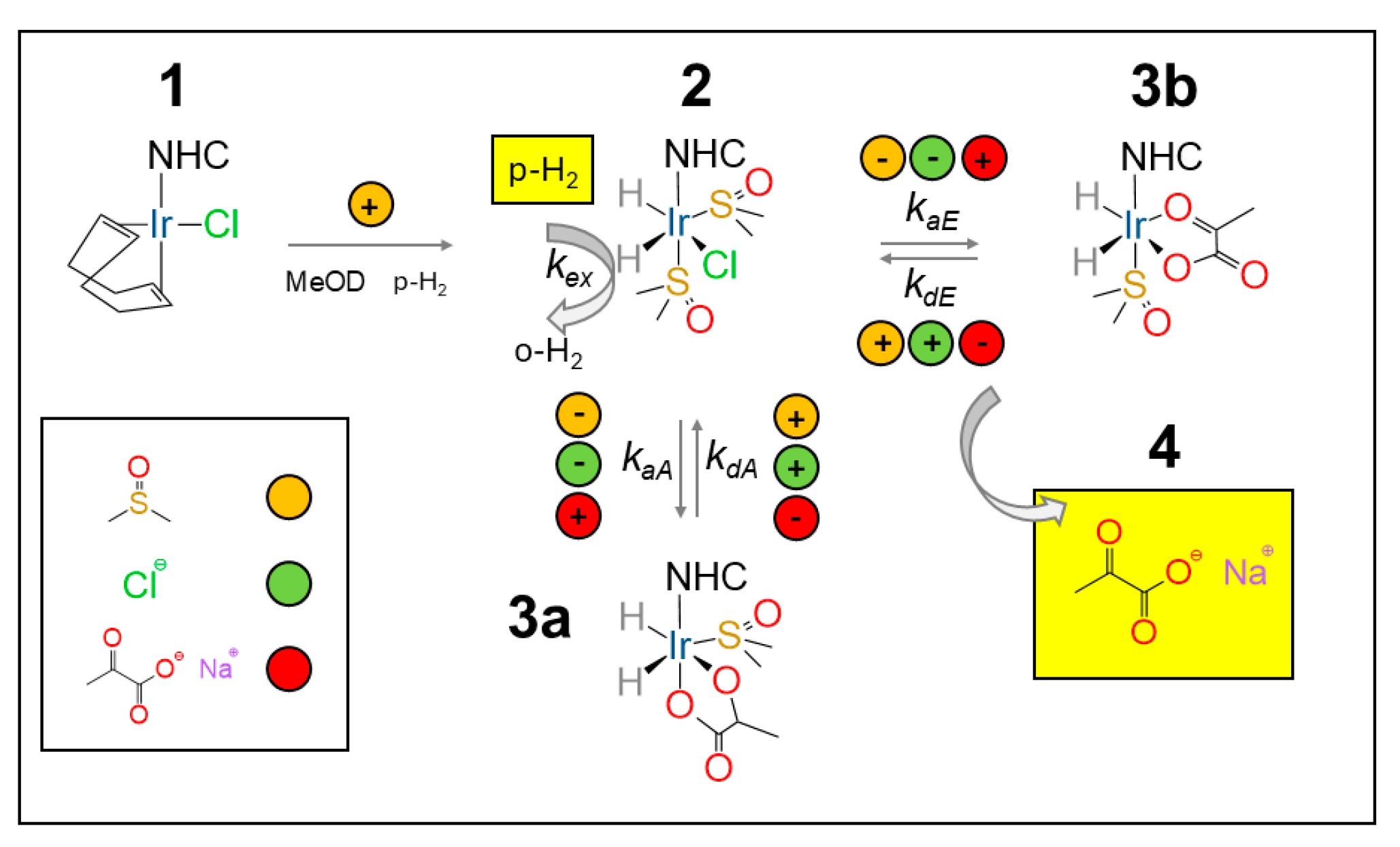

- Mamone S, Floreani F, Faramawy A, Graiff C, Franco L, Ruzzi M, et al. (De)coding SABRE of [1-13C]Pyruvate. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2025;10.1039.D5CP01773D.

- Tickner, B.J.; Lewis, J.S.; John, R.O.; Whitwood, A.C.; Duckett, S.B. Mechanistic insight into novel sulfoxide containing SABRE polarisation transfer catalysts. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 15198–15206. [CrossRef]

- Tickner, B.J.; Semenova, O.; Iali, W.; Rayner, P.J.; Whitwood, A.C.; Duckett, S.B. Optimisation of pyruvate hyperpolarisation using SABRE by tuning the active magnetisation transfer catalyst. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 1343–1355. [CrossRef]

- Verlinden K, Buhl H, Frank W, Ganter C. Determining the Ligand Properties of N-Heterocyclic Carbenes from 77Se NMR Parameters. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2015 May;2015(14):2416–25.

- Clavier, H.; Nolan, S.P. Percent buried volume for phosphine and N-heterocyclic carbene ligands: steric properties in organometallic chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 841–861. [CrossRef]

- Tolman CA. Steric effects of phosphorus ligands in organometallic chemistry and homogeneous catalysis. Chem Rev. 1977 June 1;77(3):313–48.

- Teng, Q.; Huynh, H.V. A unified ligand electronic parameter based on 13C NMR spectroscopy of N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. Dalton Trans. 2016, 46, 614–627. [CrossRef]

- Descamps, C.; Coquelet, C.; Bouallou, C.; Richon, D. Solubility of hydrogen in methanol at temperatures from 248.41 to 308.20K. Thermochim. Acta 2005, 430, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Assaf, C.D.; Gui, X.; Auer, A.A.; Duckett, S.B.; Hövener, J.-B.; Pravdivtsev, A.N. J Coupling Constants of <1 Hz Enable 13C Hyperpolarization of Pyruvate via Reversible Exchange of Parahydrogen. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 1195–1203. [CrossRef]

- Assaf, C.D.; Gui, X.; Salnikov, O.G.; Brahms, A.; Chukanov, N.V.; Skovpin, I.V.; Chekmenev, E.Y.; Herges, R.; Duckett, S.B.; Koptyug, I.V.; et al. Analysis of chemical exchange in iridium N-heterocyclic carbene complexes using heteronuclear parahydrogen-enhanced NMR. Commun. Chem. 2024, 7, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Salnikov, O.G.; Assaf, C.D.; Yi, A.P.; Duckett, S.B.; Chekmenev, E.Y.; Hövener, J.-B.; Koptyug, I.V.; Pravdivtsev, A.N. Modeling Ligand Exchange Kinetics in Iridium Complexes Catalyzing SABRE Nuclear Spin Hyperpolarization. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 11790–11799. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).