Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

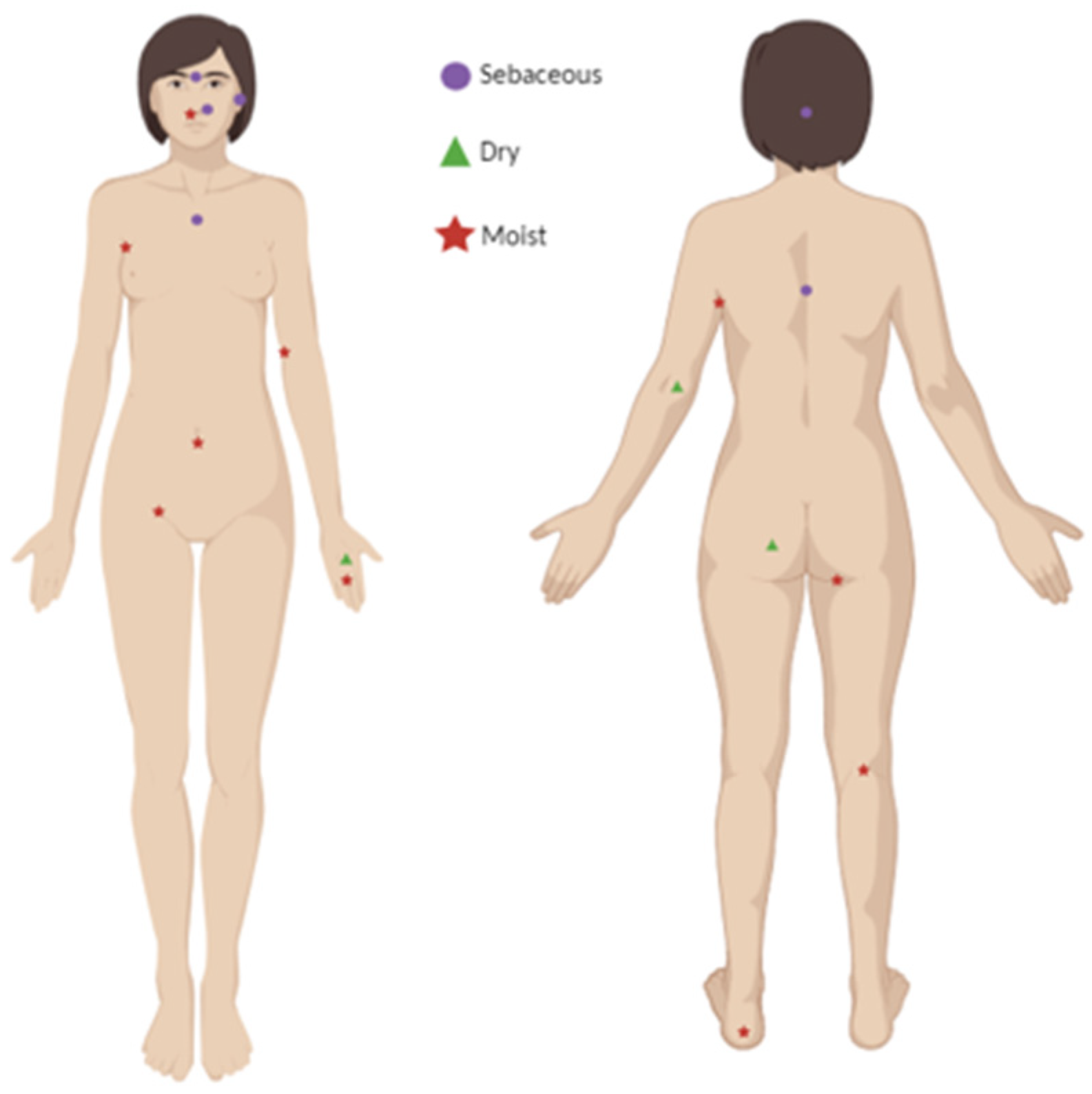

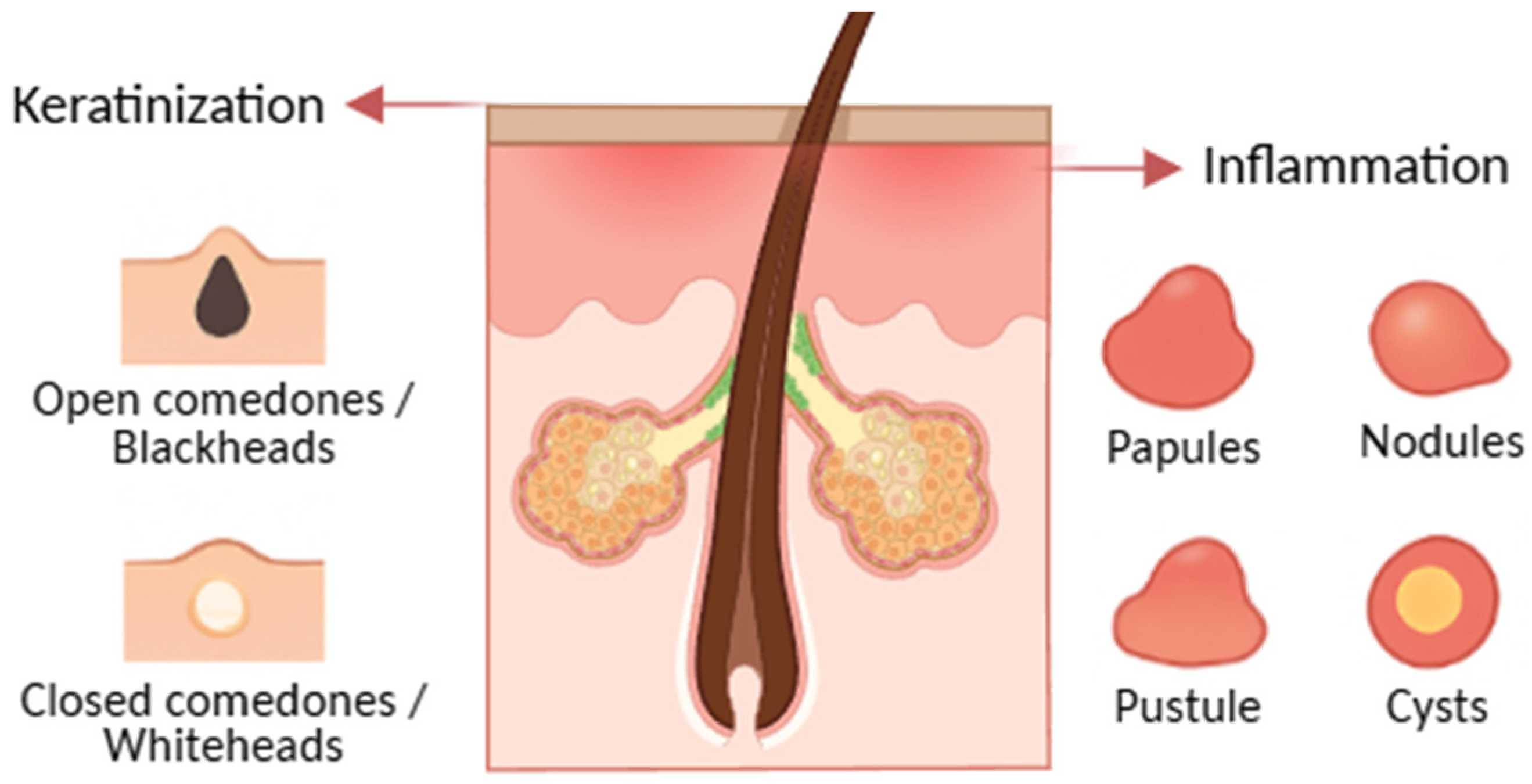

The skin serves as the primary interface between the human body and the external environment, functioning both as a protective barrier and a habitat for a diverse array of microorganisms. The skin's varying conditions—dry, moist, and sebaceous—foster the growth of different microbial communities. While these microorganisms typically exist in a beneficial symbiosis with the host, some bacteria, such as Propionibacterium acnes, can lead to skin disorders like acne. Acne is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous units, predominantly affecting high-density pilosebaceous regions such as the face, back, and neck. This condition not only results in physical scarring but also has significant psychological impacts due to societal appearance standards. This review explores the skin and its microbiome, examining their interactions in detail. Additionally, it delves into the pathogenesis of acne, discussing its underlying mechanisms and potential treatments.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Acne

- Definition and clinical spectrum.

- Distribution and onset.

- Modifiers and triggers.

- Burden and psychosocial impact.

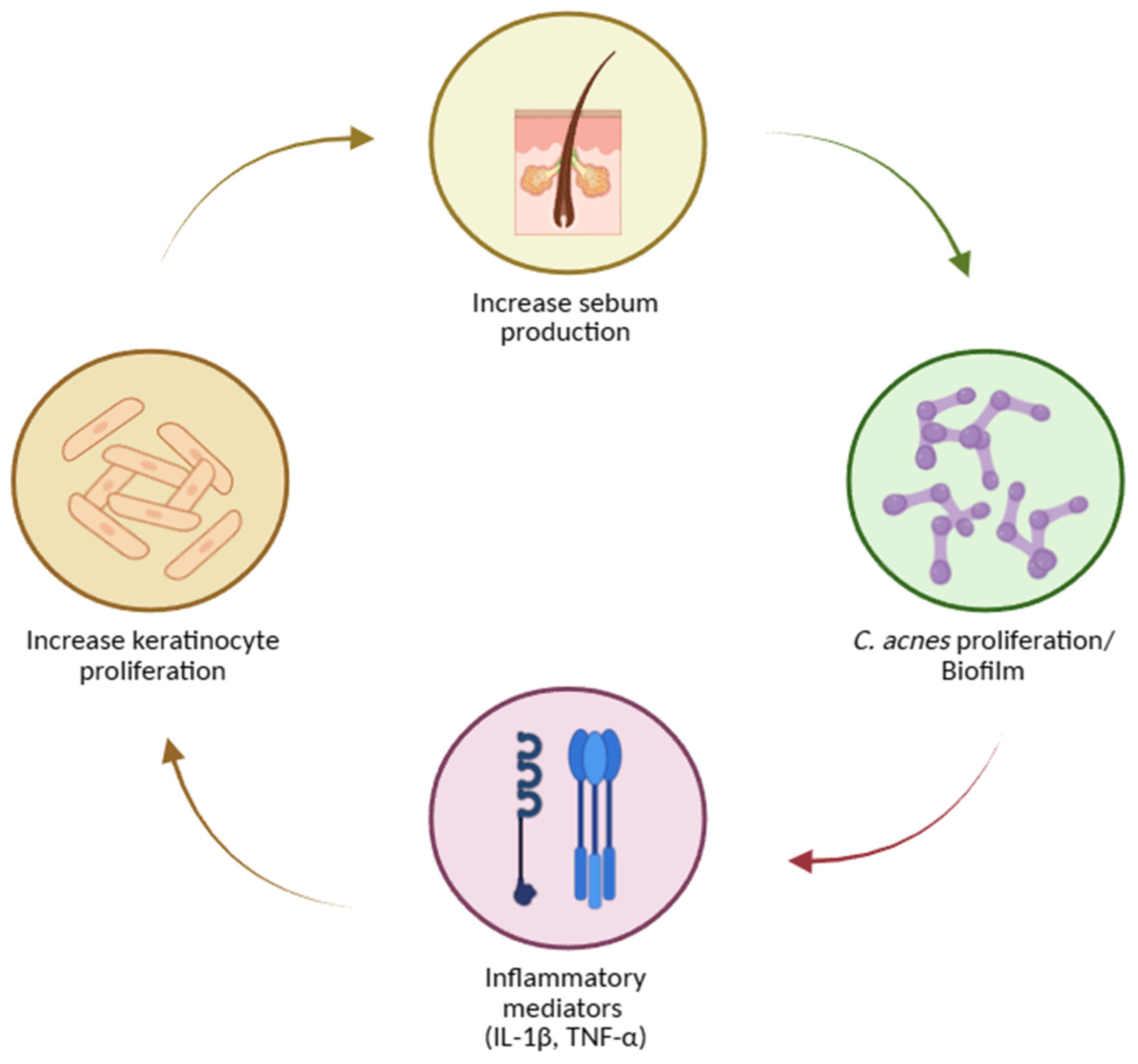

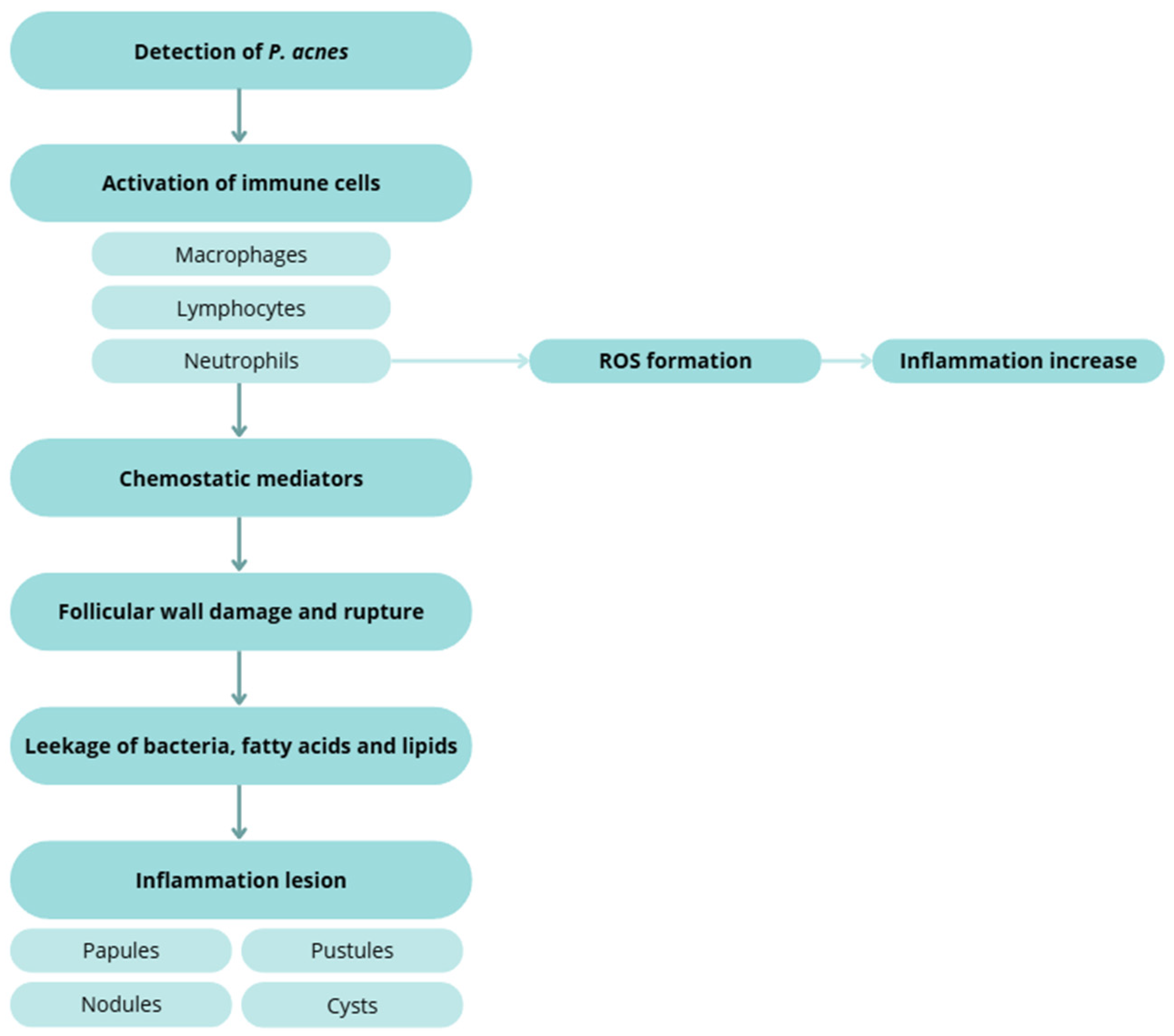

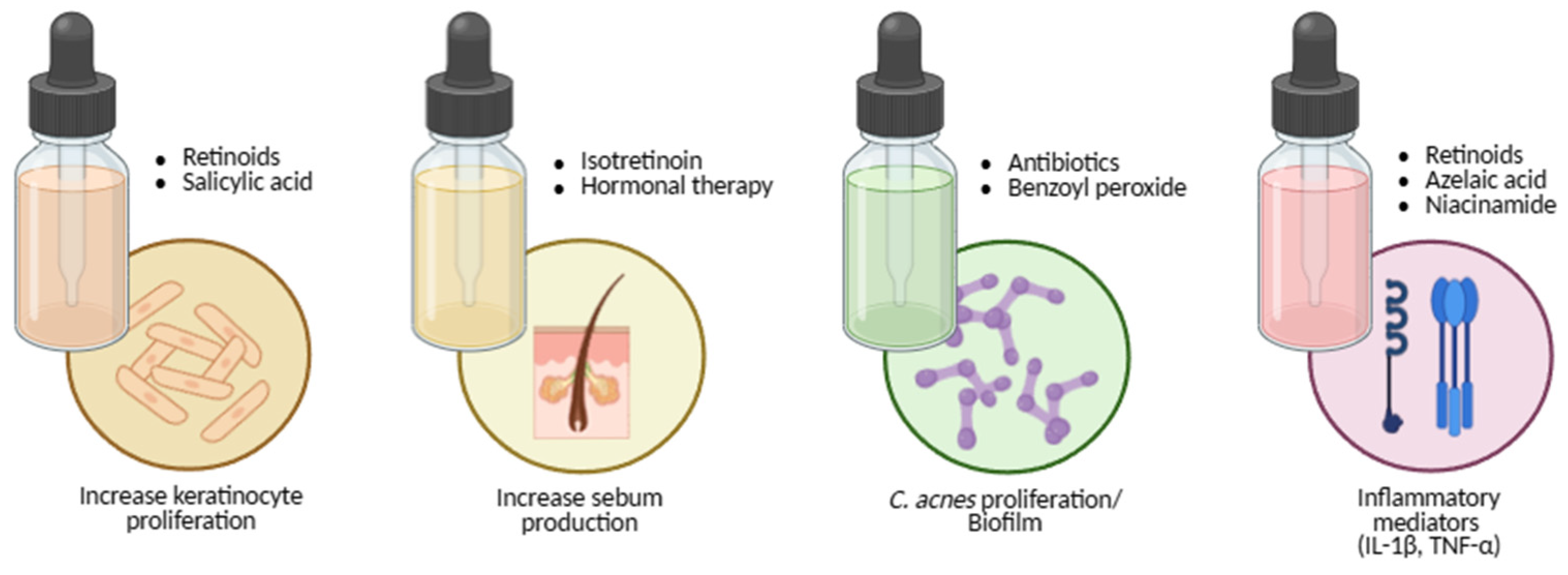

Pathogenesis: Four Interlocking Processes

- Inflammation and innate–adaptive crosstalk amplifies and sustain lesions: IL-1 signalling, neutrophil recruitment and ROS generation, and leukotriene B4–mediated cascades are implicated. Sebocytes synthesize neuropeptides, antimicrobial peptides, and antibacterial lipids, linking stress (CRH axis) and vitamin D signalling to sebaceous activity [62,63,64,68,69,73].

Acne Treatments

Topical Treatments

Systemic Treatments

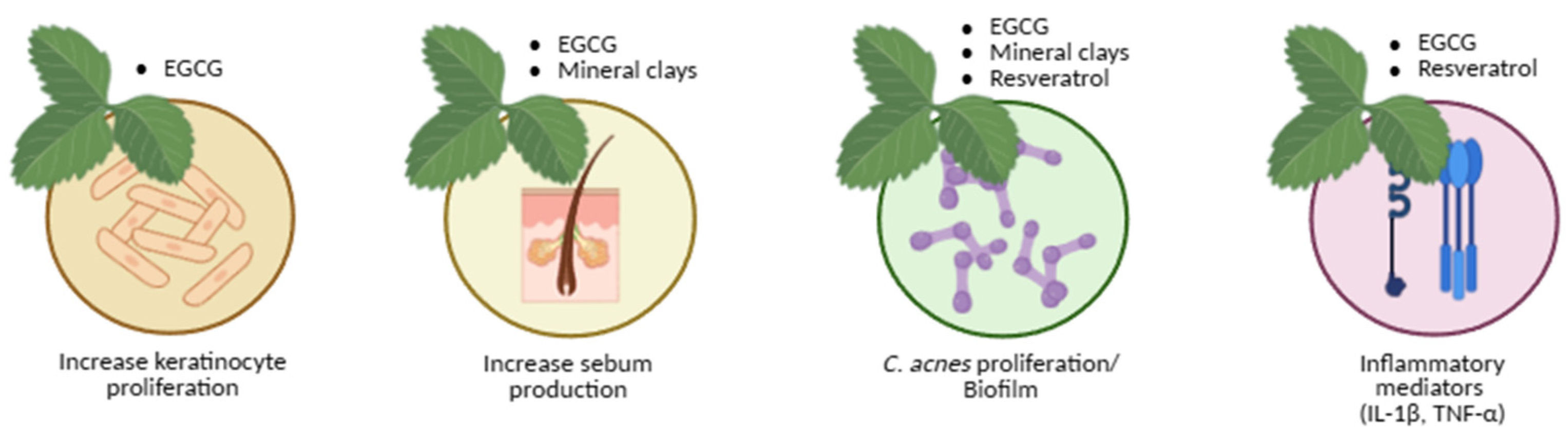

Natural and Adjunct Approaches

Natural Products Treatment

- Green tea

- Mineral clays

- Resveratrol

Clinical Integration and Outlook

Critical Perspective

Traditional, Synthetic, and Natural Approaches

2. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bojar, R.A.; Holland, K.T. Acne and Propionibacterium Acnes. Clinics in Dermatology 2004, 22, 375–379. [CrossRef]

- Segre, J.A. Epidermal Barrier Formation and Recovery in Skin Disorders. J Clin Invest 2006, 116, 1150–1158. [CrossRef]

- Marples, M.J. The Ecology of the Human Skin; Ch. C. Thomas: Springfield (Illinois), 1965;

- Schommer, N.N.; Gallo, R.L. Structure and Function of the Human Skin Microbiome. Trends in Microbiology 2013, 21, 660–668. [CrossRef]

- Grice, E.A.; Segre, J.A. The Skin Microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011, 9, 244–253. [CrossRef]

- Holland, K.T.; Cunliffe, W.J.; Roberts, C.D. The Role of Bacteria in Acne Vulgaris: A New Approach. Clin Exp Dermatol 1978, 3, 253–257. [CrossRef]

- Holland, K.T.; Ingham, E.; Cunliffe, W.J. A Review, the Microbiology of Acne. J Appl Bacteriol 1981, 51, 195–215. [CrossRef]

- Eady, E.A.; Ingham, E. Propionibacterium Acnes - Friend or Foe?: Reviews in Medical Microbiology 1994, 5, 163–173. [CrossRef]

- Grice, E.A.; Kong, H.H.; Conlan, S.; Deming, C.B.; Davis, J.; Young, A.C.; NISC COMPARATIVE SEQUENCING PROGRAM; Bouffard, G.G.; Blakesley, R.W.; Murray, P.R.; et al. Topographical and Temporal Diversity of the Human Skin Microbiome. Science 2009, 324, 1190–1192. [CrossRef]

- Structure, Function and Diversity of the Healthy Human Microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [CrossRef]

- Costello, E.K.; Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Fierer, N.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R. Bacterial Community Variation in Human Body Habitats Across Space and Time. Science 2009, 326, 1694–1697. [CrossRef]

- Faust, K.; Raes, J. Microbial Interactions: From Networks to Models. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012, 10, 538–550. [CrossRef]

- Grice, E.A.; Kong, H.H.; Renaud, G.; Young, A.C.; Bouffard, G.G.; Blakesley, R.W.; Wolfsberg, T.G.; Turner, M.L.; Segre, J.A. A Diversity Profile of the Human Skin Microbiota. Genome Res. 2008, 18, 1043–1050. [CrossRef]

- Tagami, H. Location-Related Differences in Structure and Function of the Stratum Corneum with Special Emphasis on Those of the Facial Skin. Int J Cosmet Sci 2008, 30, 413–434. [CrossRef]

- Fulton, C.; Anderson, G.M.; Zasloff, M.; Bull, R.; Quinn, A.G. Expression of Natural Peptide Antibiotics in Human Skin. Lancet 1997, 350, 1750–1751. [CrossRef]

- Schittek, B.; Hipfel, R.; Sauer, B.; Bauer, J.; Kalbacher, H.; Stevanovic, S.; Schirle, M.; Schroeder, K.; Blin, N.; Meier, F.; et al. Dermcidin: A Novel Human Antibiotic Peptide Secreted by Sweat Glands. Nat Immunol 2001, 2, 1133–1137. [CrossRef]

- Gribbon, E.M.; Cunliffe, W.J.; Holland, K.T. Interaction of Propionibacterium Acnes with Skin Lipids in Vitro. J Gen Microbiol 1993, 139, 1745–1751. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, R.L.; Hooper, L.V. Epithelial Antimicrobial Defence of the Skin and Intestine. Nat Rev Immunol 2012, 12, 503–516. [CrossRef]

- Roth, R.R.; James, W.D. Microbial Ecology of the Skin. Annu Rev Microbiol 1988, 42, 441–464. [CrossRef]

- Elias, P.M. The Skin Barrier as an Innate Immune Element. Semin Immunopathol 2007, 29, 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Aly, R.; Shirley, C.; Cunico, B.; Maibach, H.I. Effect of Prolonged Occlusion on the Microbial Flora, pH, Carbon Dioxide and Transepidermal Water Loss on Human Skin. J Invest Dermatol 1978, 71, 378–381. [CrossRef]

- Korting, H.C.; Hübner, K.; Greiner, K.; Hamm, G.; Braun-Falco, O. Differences in the Skin Surface pH and Bacterial Microflora Due to the Long-Term Application of Synthetic Detergent Preparations of pH 5.5 and pH 7.0. Results of a Crossover Trial in Healthy Volunteers. Acta Derm Venereol 1990, 70, 429–431.

- Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Costello, E.K.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Delivery Mode Shapes the Acquisition and Structure of the Initial Microbiota across Multiple Body Habitats in Newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 11971–11975. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.T.; Bakacs, E.; Combellick, J.; Grigoryan, Z.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G. The Infant Microbiome Development: Mom Matters. Trends Mol Med 2015, 21, 109–117. [CrossRef]

- Somerville, D.A. The Normal Flora of the Skin in Different Age Groups. Br J Dermatol 1969, 81, 248–258. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Conlan, S.; Polley, E.C.; Segre, J.A.; Kong, H.H. Shifts in Human Skin and Nares Microbiota of Healthy Children and Adults. Genome Med 2012, 4, 77. [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.-H.; Deming, C.; Kennedy, E.A.; Conlan, S.; Polley, E.C.; Ng, W.-I.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Segre, J.A.; Kong, H.H. Diverse Human Skin Fungal Communities in Children Converge in Adulthood. J Invest Dermatol 2016, 136, 2356–2363. [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.-H.; Kennedy, E.A.; Kong, H.H. Topographical and Physiological Differences of the Skin Mycobiome in Health and Disease. Virulence 2017, 8, 324–333. [CrossRef]

- Havlickova, B.; Czaika, V.A.; Friedrich, M. Epidemiological Trends in Skin Mycoses Worldwide. Mycoses 2008, 51 Suppl 4, 2–15. [CrossRef]

- Seebacher, C.; Bouchara, J.-P.; Mignon, B. Updates on the Epidemiology of Dermatophyte Infections. Mycopathologia 2008, 166, 335–352. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakis, K.P.; Terzoudi, S.; Palamaras, I.; Pagana, G.; Michailides, C.; Emmanuelides, S. Pityriasis Versicolor Prevalence by Age and Gender. Mycoses 2006, 49, 517–518. [CrossRef]

- Marples, R.R. Sex, Constancy, and Skin Bacteria. Arch Dermatol Res 1982, 272, 317–320. [CrossRef]

- Giacomoni, P.U.; Mammone, T.; Teri, M. Gender-Linked Differences in Human Skin. J Dermatol Sci 2009, 55, 144–149. [CrossRef]

- Leeming, J.P.; Holland, K.T.; Cunliffe, W.J. The Microbial Ecology of Pilosebaceous Units Isolated from Human Skin. J Gen Microbiol 1984, 130, 803–807. [CrossRef]

- McGinley, K.J.; Webster, G.F.; Leyden, J.J. Regional Variations of Cutaneous Propionibacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 1978, 35, 62–66.

- Findley, K.; Oh, J.; Yang, J.; Conlan, S.; Deming, C.; Meyer, J.A.; Schoenfeld, D.; Nomicos, E.; Park, M.; Kong, H.H.; et al. Topographic Diversity of Fungal and Bacterial Communities in Human Skin. Nature 2013, 498, 367–370. [CrossRef]

- Paulino, L.C.; Tseng, C.-H.; Blaser, M.J. Analysis of Malassezia Microbiota in Healthy Superficial Human Skin and in Psoriatic Lesions by Multiplex Real-Time PCR. FEMS Yeast Research 2008, 8, 460–471. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Saunders, C.W.; Hu, P.; Grant, R.A.; Boekhout, T.; Kuramae, E.E.; Kronstad, J.W.; DeAngelis, Y.M.; Reeder, N.L.; Johnstone, K.R.; et al. Dandruff-Associated Malassezia Genomes Reveal Convergent and Divergent Virulence Traits Shared with Plant and Human Fungal Pathogens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 18730–18735. [CrossRef]

- Iebba, V.; Totino, V.; Gagliardi, A.; Santangelo, F.; Cacciotti, F.; Trancassini, M.; Mancini, C.; Cicerone, C.; Corazziari, E.; Pantanella, F.; et al. Eubiosis and Dysbiosis: The Two Sides of the Microbiota. New Microbiol 2016, 39, 1–12.

- Byrd, A.L.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. The Human Skin Microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16, 143–155. [CrossRef]

- Leyden, J.J.; McGinley, K.J.; Mills, O.H.; Kligman, A.M. Propionibacterium Levels in Patients with and without Acne Vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol 1975, 65, 382–384. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, J.S.; Krowchuk, D.P.; Leyden, J.J.; Lucky, A.W.; Shalita, A.R.; Siegfried, E.C.; Thiboutot, D.M.; Van Voorhees, A.S.; Beutner, K.A.; Sieck, C.K.; et al. Guidelines of Care for Acne Vulgaris Management. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007, 56, 651–663. [CrossRef]

- Degitz, K.; Placzek, M.; Borelli, C.; Plewig, G. Pathophysiology of Acne. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2007, 5, 316–323. [CrossRef]

- Tomida, S.; Nguyen, L.; Chiu, B.-H.; Liu, J.; Sodergren, E.; Weinstock, G.M.; Li, H. Pan-Genome and Comparative Genome Analyses of Propionibacterium Acnes Reveal Its Genomic Diversity in the Healthy and Diseased Human Skin Microbiome. mBio 2013, 4, e00003-00013. [CrossRef]

- Fitz-Gibbon, S.; Tomida, S.; Chiu, B.-H.; Nguyen, L.; Du, C.; Liu, M.; Elashoff, D.; Erfe, M.C.; Loncaric, A.; Kim, J.; et al. Propionibacterium Acnes Strain Populations in the Human Skin Microbiome Associated with Acne. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2013, 133, 2152–2160. [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Shi, B.; Erfe, M.C.; Craft, N.; Li, H. Vitamin B12 Modulates the Transcriptome of the Skin Microbiota in Acne Pathogenesis. Sci Transl Med 2015, 7, 293ra103. [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.C.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Garner, S. Acne Vulgaris. The Lancet 2012, 379, 361–372. [CrossRef]

- Lucky, A.W. A Review of Infantile and Pediatric Acne. Dermatology 1998, 196, 95–97. [CrossRef]

- Adebamowo, C.A.; Spiegelman, D.; Berkey, C.S.; Danby, F.W.; Rockett, H.H.; Colditz, G.A.; Willett, W.C.; Holmes, M.D. Milk Consumption and Acne in Teenaged Boys. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008, 58, 787–793. [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, S.F.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Fowler, J.F.; Fried, R.G.; Levy, M.L.; Webster, G.F. Acne Epidemiology and Pathophysiology. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2010, 29, 2–4. [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, S.Z.; Orawa, H.; Zouboulis, C.C. Prevalence, Severity, and Severity Risk Factors of Acne in High School Pupils: A Community-Based Study. J Invest Dermatol 2009, 129, 2136–2141. [CrossRef]

- Stoll, S.; Shalita, A.R.; Webster, G.F.; Kaplan, R.; Danesh, S.; Penstein, A. The Effect of the Menstrual Cycle on Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001, 45, 957–960. [CrossRef]

- Yosipovitch, G.; Tang, M.; Dawn, A.G.; Chen, M.; Goh, C.L.; Huak, Y.; Seng, L.F. Study of Psychological Stress, Sebum Production and Acne Vulgaris in Adolescents. Acta Derm Venereol 2007, 87, 135–139. [CrossRef]

- Plewig, G.; Fulton, J.E.; Kligman, A.M. Pomade Acne. Arch Dermatol 1970, 101, 580–584.

- Valeyrie-Allanore, L.; Sassolas, B.; Roujeau, J.-C. Drug-Induced Skin, Nail and Hair Disorders. Drug Saf 2007, 30, 1011–1030. [CrossRef]

- Melnik, B.; Jansen, T.; Grabbe, S. Abuse of Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids and Bodybuilding Acne: An Underestimated Health Problem. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2007, 5, 110–117. [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Sinclair, R.D. Perceptions of Acne Vulgaris in Final Year Medical Student Written Examination Answers. Australas J Dermatol 2001, 42, 98–101. [CrossRef]

- Magin, P.; Pond, D.; Smith, W.; Watson, A. A Systematic Review of the Evidence for “myths and Misconceptions” in Acne Management: Diet, Face-Washing and Sunlight. Fam Pract 2005, 22, 62–70. [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, A.; Bershad, S. Topical Acne Drugs: Review of Clinical Properties, Systemic Exposure, and Safety. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003, 4, 473–492. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, S.; Careccia, R.E.; Barham, K.L.; Hancox, J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acne. Am Fam Physician 2004, 69, 2123–2130.

- Ayer, J.; Burrows, N. Acne: More than Skin Deep. Postgrad Med J 2006, 82, 500–506. [CrossRef]

- Jeremy, A.H.T.; Holland, D.B.; Roberts, S.G.; Thomson, K.F.; Cunliffe, W.J. Inflammatory Events Are Involved in Acne Lesion Initiation. J Invest Dermatol 2003, 121, 20–27. [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, I.; Danby, F.W.; Ju, Q.; Wang, X.; Xiang, L.F.; Xia, L.; Chen, W.; Nagy, I.; Picardo, M.; Suh, D.H.; et al. New Developments in Our Understanding of Acne Pathogenesis and Treatment. Exp Dermatol 2009, 18, 821–832. [CrossRef]

- Alestas, T.; Ganceviciene, R.; Fimmel, S.; Müller-Decker, K.; Zouboulis, C.C. Enzymes Involved in the Biosynthesis of Leukotriene B4 and Prostaglandin E2 Are Active in Sebaceous Glands. J Mol Med (Berl) 2006, 84, 75–87. [CrossRef]

- Gollnick, H. Current Concepts of the Pathogenesis of Acne: Implications for Drug Treatment. Drugs 2003, 63, 1579–1596. [CrossRef]

- Gollnick, H.; Cunliffe, W.; Berson, D.; Dreno, B.; Finlay, A.; Leyden, J.J.; Shalita, A.R.; Thiboutot, D. Management of Acne: A Report From a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2003, 49, S1–S37. [CrossRef]

- Webster, G.F. Acne. Current Problems in Dermatology 1996, 8, 237–268. [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Böhm, M. Neuroendocrine Regulation of Sebocytes -- a Pathogenetic Link between Stress and Acne. Exp Dermatol 2004, 13 Suppl 4, 31–35. [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Baron, J.M.; Böhm, M.; Kippenberger, S.; Kurzen, H.; Reichrath, J.; Thielitz, A. Frontiers in Sebaceous Gland Biology and Pathology. Exp Dermatol 2008, 17, 542–551. [CrossRef]

- Iinuma, K.; Sato, T.; Akimoto, N.; Noguchi, N.; Sasatsu, M.; Nishijima, S.; Kurokawa, I.; Ito, A. Involvement of Propionibacterium Acnes in the Augmentation of Lipogenesis in Hamster Sebaceous Glands In Vivo and In Vitro. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2009, 129, 2113–2119. [CrossRef]

- McDowell, A.; Gao, A.; Barnard, E.; Fink, C.; Murray, P.I.; Dowson, C.G.; Nagy, I.; Lambert, P.A.; Patrick, S. A Novel Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme for the Opportunistic Pathogen Propionibacterium Acnes and Characterization of Type I Cell Surface-Associated Antigens. Microbiology 2011, 157, 1990–2003. [CrossRef]

- Burkhart, C.G.; Burkhart, C.N.; Lehmann, P.F. Acne: A Review of Immunologic and Microbiologic Factors. Postgrad Med J 1999, 75, 328–331. [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, H.; Horio, T.; Hattori, K. Increased Hydrogen Peroxide Generation by Neutrophils from Patients with Acne Inflammation. International Journal of Dermatology 2003, 42, 366–369. [CrossRef]

- Thiboutot, D.; Gollnick, H.; Bettoli, V.; Dréno, B.; Kang, S.; Leyden, J.J.; Shalita, A.R.; Lozada, V.T.; Berson, D.; Finlay, A.; et al. New Insights into the Management of Acne: An Update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne Group. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009, 60, S1-50. [CrossRef]

- Białecka, A.; Mak, M.; Biedroń, R.; Bobek, M.; Kasprowicz, A.; Marcinkiewicz, J. Different Pro-Inflammatory and Immunogenic Potentials of Propionibacterium Acnes and Staphylococcus Epidermidis: Implications for Chronic Inflammatory Acne. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2005, 53, 79–85.

- Webster, G.F.; Poyner, T.; Cunliffe, B. Clinical reviewAcne vulgarisCommentary: A UK Primary Care Perspective on Treating Acne. BMJ 2002, 325, 475–479. [CrossRef]

- Jahns, A.C.; Lundskog, B.; Ganceviciene, R.; Palmer, R.H.; Golovleva, I.; Zouboulis, C.C.; McDowell, A.; Patrick, S.; Alexeyev, O.A. An Increased Incidence of Propionibacterium Acnes Biofilms in Acne Vulgaris: A Case–Control Study. British Journal of Dermatology 2012, 167, 50–58. [CrossRef]

- Krautheim, A.; Gollnick, H. Transdermal Penetration of Topical Drugs Used in the Treatment of Acne. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003, 42, 1287–1304. [CrossRef]

- Olutunmbi, Y.; Paley, K.; English, J.C. Adolescent Female Acne: Etiology and Management. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2008, 21, 171–176. [CrossRef]

- Bowe, W.P.; Shalita, A.R. Effective Over-the-Counter Acne Treatments. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2008, 27, 170–176. [CrossRef]

- Fox, L.; Csongradi, C.; Aucamp, M.; Du Plessis, J.; Gerber, M. Treatment Modalities for Acne. Molecules 2016, 21, 1063. [CrossRef]

- Bershad, S.V. The Modern Age of Acne Therapy: A Review of Current Treatment Options. Mt Sinai J Med 2001, 68, 279–286.

- Shaw, L.; Kennedy, C. The Treatment of Acne. Paediatrics and Child Health 2007, 17, 385–389. [CrossRef]

- Gollnick, H.P.M.; Krautheim, A. Topical Treatment in Acne: Current Status and Future Aspects. Dermatology 2003, 206, 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Lavers, I. Diagnosis and Management of Acne Vulgaris. Nurse Prescribing 2014, 12, 330–336. [CrossRef]

- Webster, G.F.; Graber, E.M. Antibiotic Treatment for Acne Vulgaris. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2008, 27, 183–187. [CrossRef]

- Namazi, M.R. Nicotinamide in Dermatology: A Capsule Summary. Int J Dermatol 2007, 46, 1229–1231. [CrossRef]

- Draelos, Z.D.; Matsubara, A.; Smiles, K. The Effect of 2% Niacinamide on Facial Sebum Production. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2006, 8, 96–101. [CrossRef]

- Draelos, Z.D. Novel Topical Therapies in Cosmetic Dermatology. Current Problems in Dermatology 2000, 12, 235–239. [CrossRef]

- Gehring, W. Nicotinic Acid/Niacinamide and the Skin. J Cosmet Dermatol 2004, 3, 88–93. [CrossRef]

- Katsambas, A.; Papakonstantinou, A. Acne: Systemic Treatment. Clin Dermatol 2004, 22, 412–418. [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Piquero-Martin, J. Update and Future of Systemic Acne Treatment. Dermatology 2003, 206, 37–53. [CrossRef]

- Leyden, J.J.; McGinley, K.J.; Foglia, A.N. Qualitative and Quantitative Changes in Cutaneous Bacteria Associated with Systemic Isotretinoin Therapy for Acne Conglobata. J Invest Dermatol 1986, 86, 390–393. [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, W.; Jordaan, H.F.; Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne Acne Guideline 2005 Update. S Afr Med J 2005, 95, 881–892.

- Fisk, W.A.; Lev-Tov, H.A.; Sivamani, R.K. Botanical and Phytochemical Therapy of Acne: A Systematic Review. Phytother Res 2014, 28, 1137–1152. [CrossRef]

- Magin, P.J.; Adams, J.; Pond, C.D.; Smith, W. Topical and Oral CAM in Acne: A Review of the Empirical Evidence and a Consideration of Its Context. Complement Ther Med 2006, 14, 62–76. [CrossRef]

- Gaur, S.; Agnihotri, R. Green Tea: A Novel Functional Food for the Oral Health of Older Adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2014, 14, 238–250. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.Y.; Kwon, H.H.; Min, S.U.; Thiboutot, D.M.; Suh, D.H. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Improves Acne in Humans by Modulating Intracellular Molecular Targets and Inhibiting P. Acnes. J Invest Dermatol 2013, 133, 429–440. [CrossRef]

- Carretero, M.I. Clay Minerals and Their Beneficial Effects upon Human Health. A Review. Applied Clay Science 2002, 21, 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Lee, C.W.; Lee, M.Y. Antibacterial Effects of Minerals from Ores Indigenous to Korea. J Environ Biol 2009, 30, 151–154.

- Simonart, T. Newer Approaches to the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. Am J Clin Dermatol 2012, 13, 357–364. [CrossRef]

- Docherty, J.J.; McEwen, H.A.; Sweet, T.J.; Bailey, E.; Booth, T.D. Resveratrol Inhibition of Propionibacterium Acnes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007, 59, 1182–1184. [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, L.E.; Newton, R.; Kennedy, G.E.; Fenwick, P.S.; Leung, R.H.F.; Ito, K.; Russell, R.E.K.; Barnes, P.J. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Resveratrol in Lung Epithelial Cells: Molecular Mechanisms. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004, 287, L774-783. [CrossRef]

- Fabbrocini, G.; Staibano, S.; De Rosa, G.; Battimiello, V.; Fardella, N.; Ilardi, G.; La Rotonda, M.I.; Longobardi, A.; Mazzella, M.; Siano, M.; et al. Resveratrol-Containing Gel for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris: A Single-Blind, Vehicle-Controlled, Pilot Study. Am J Clin Dermatol 2011, 12, 133–141. [CrossRef]

- Frémont, L. Biological Effects of Resveratrol. Life Sciences 2000, 66, 663–673. [CrossRef]

| Treatment Method | Products |

| Topical | Retinoids: tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene • Antibiotics: erythromycin, clindamycin • Diverse: benzoyl peroxide, azelaic acid, niacinamide, salicylic acid |

| Systemic | Retinoids: isotretinoin • Antibiotics: erythromycin, clindamycin, levofloxacin, doxycycline • Hormonal: combined contraceptives, spironolactone |

| Natural/Adjunct | Green tea polyphenols (EGCG) • Minerals (clay-based) • Resveratrol |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).