Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Extraction of DNA

2.3. Next Generation Sequencing

2.4. Analysis of the Microbiome

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

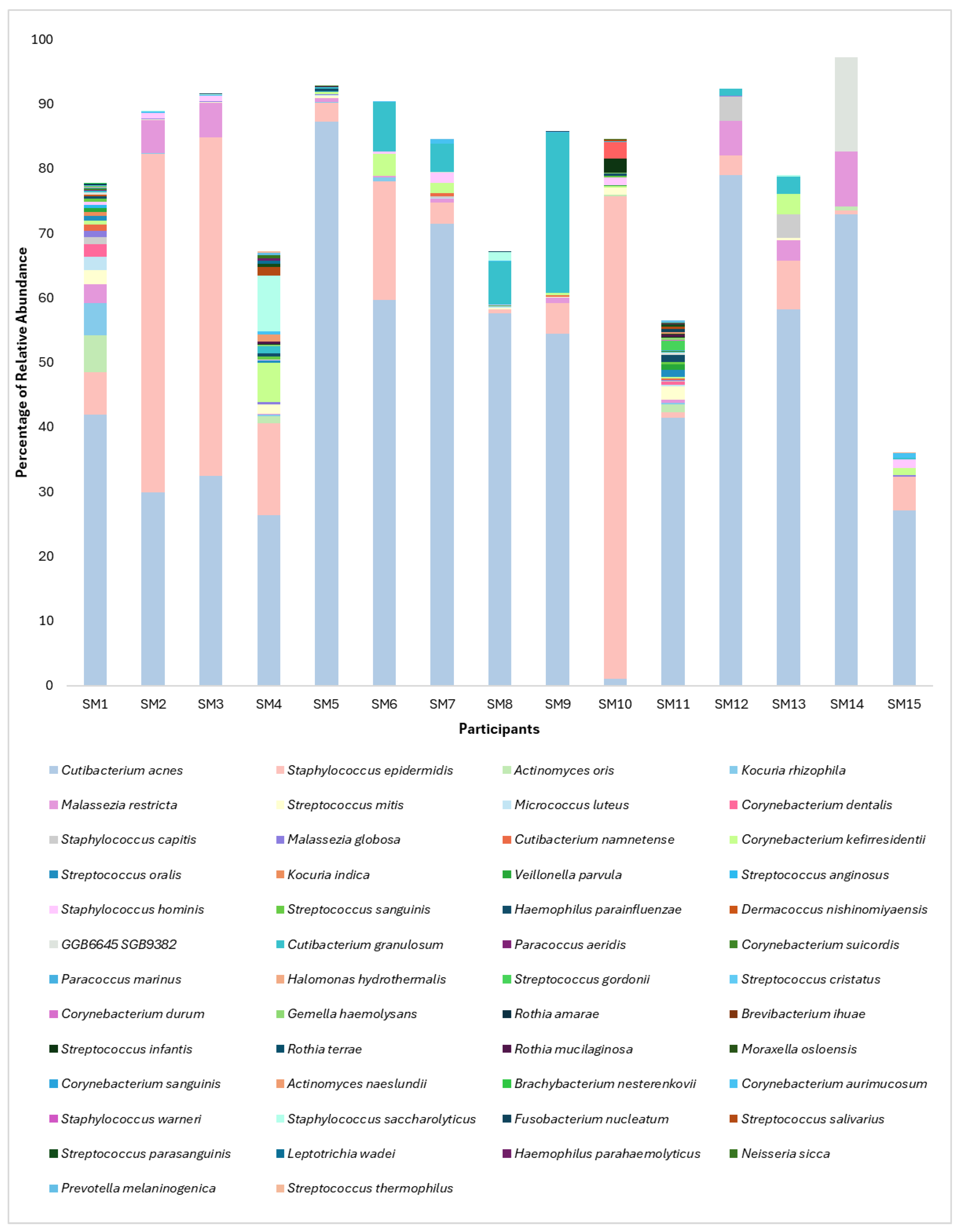

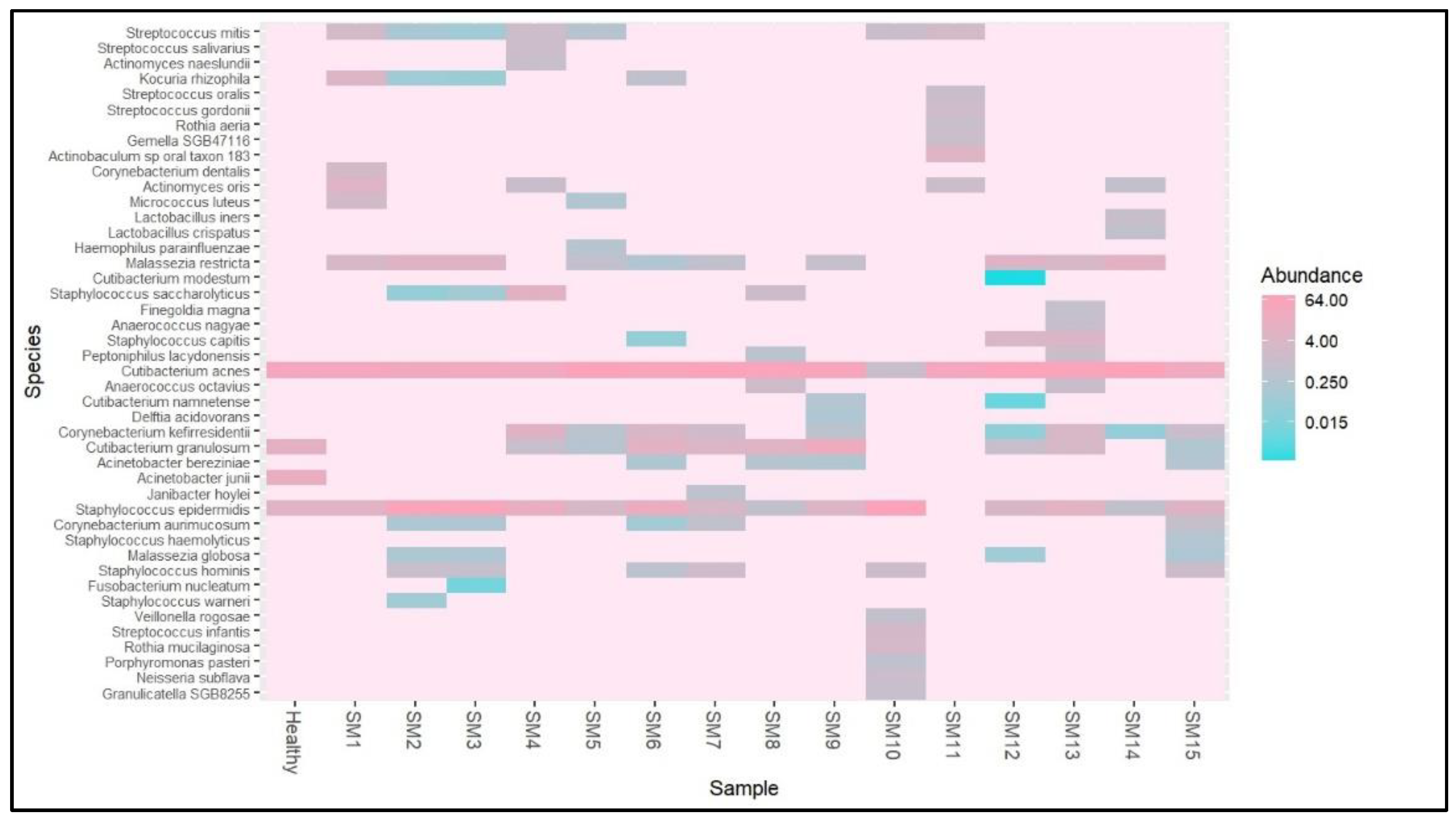

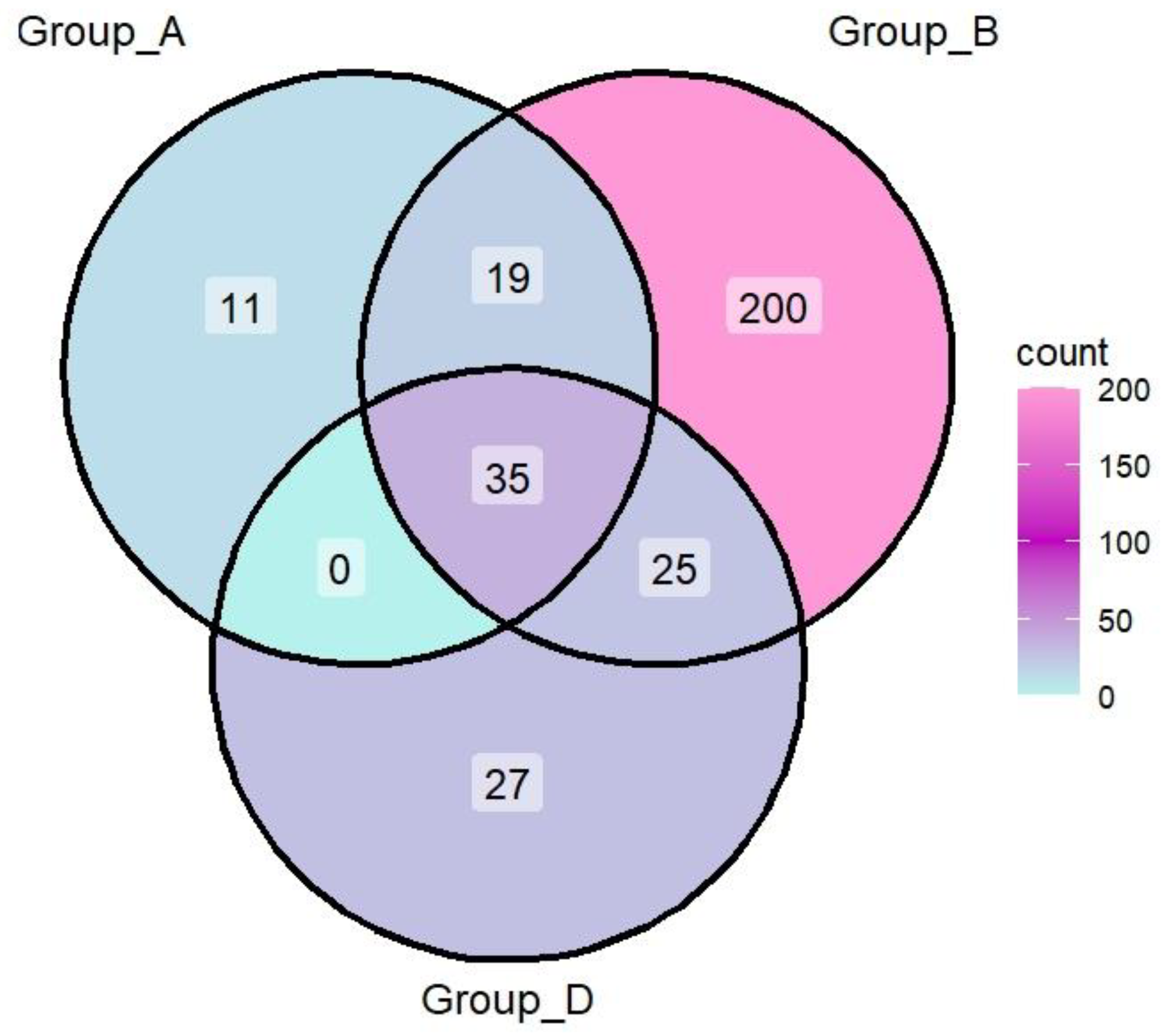

3.1. Microbiome Composition and Alpha Diversity

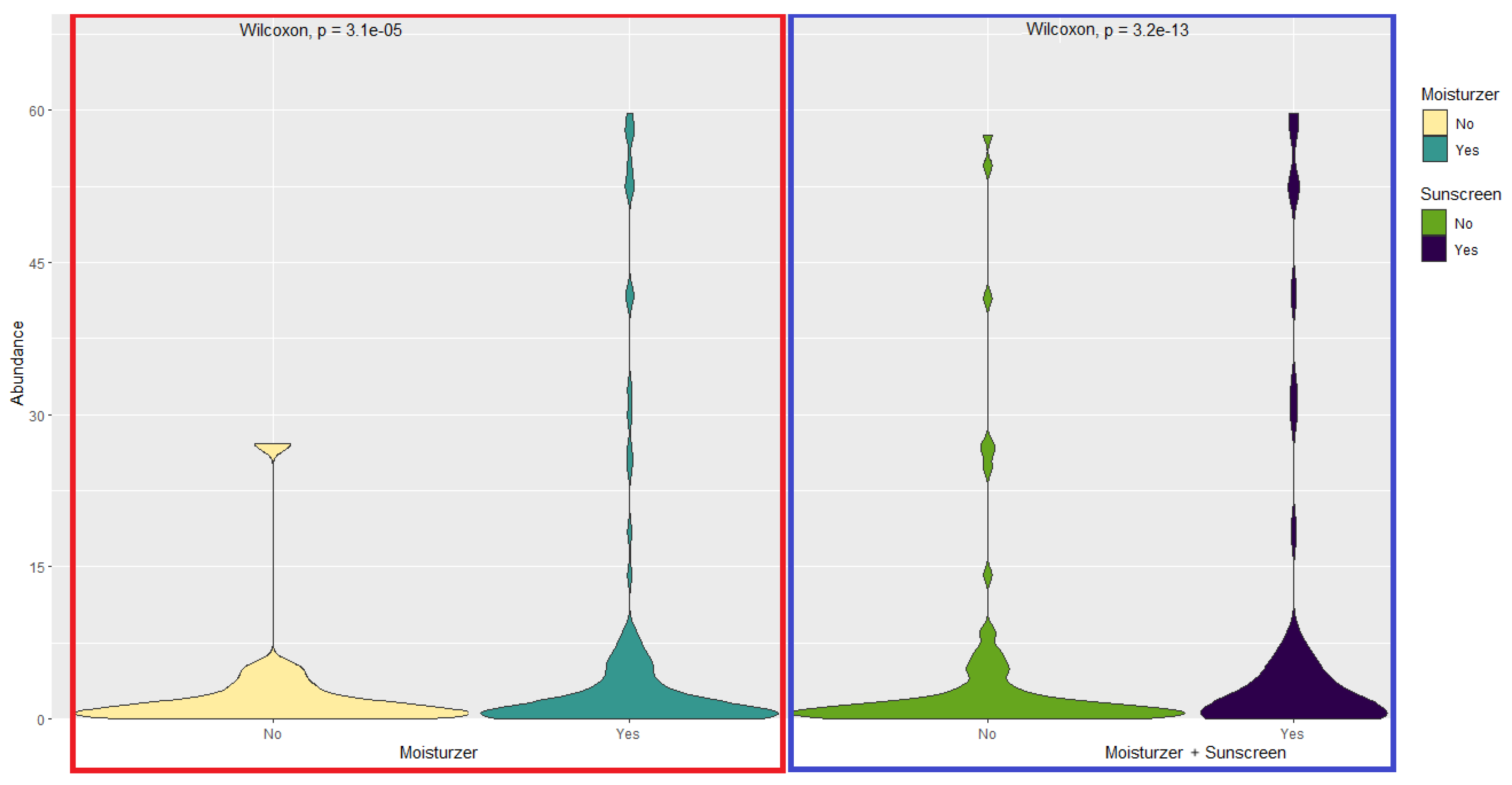

3.2. Relationship Between Skin Care Routine and Skin Microbiome

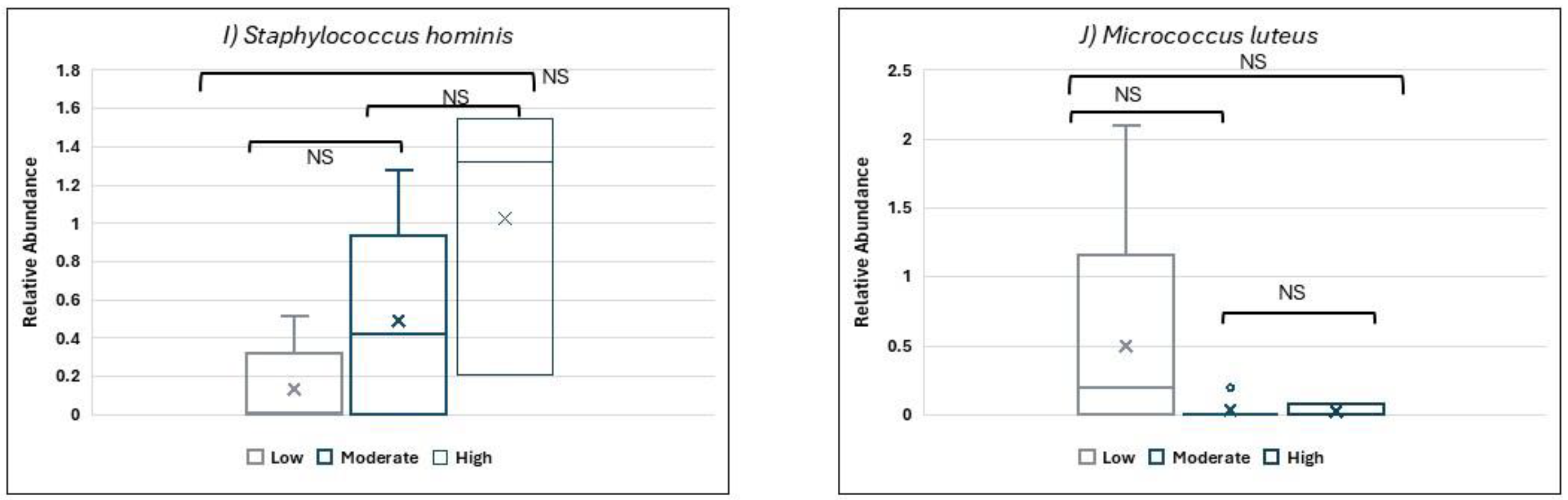

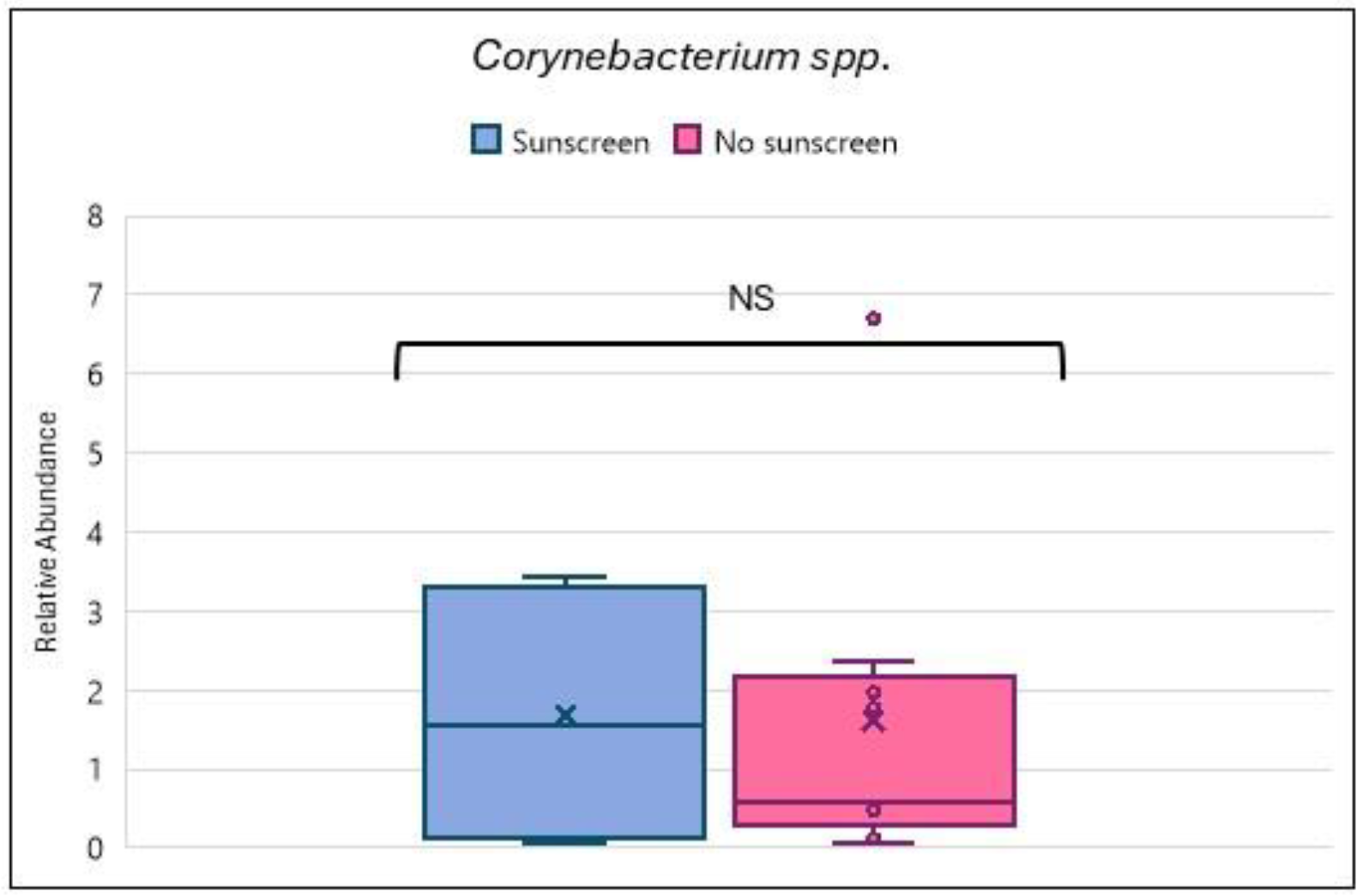

3.3. Skin Microbiome and Sun Exposure

3.4. Skin Microbiome, Moisturizer and Atopic Dermatitis

3.5. Skin Microbiome, Moisturizer and Hyperpigmentation

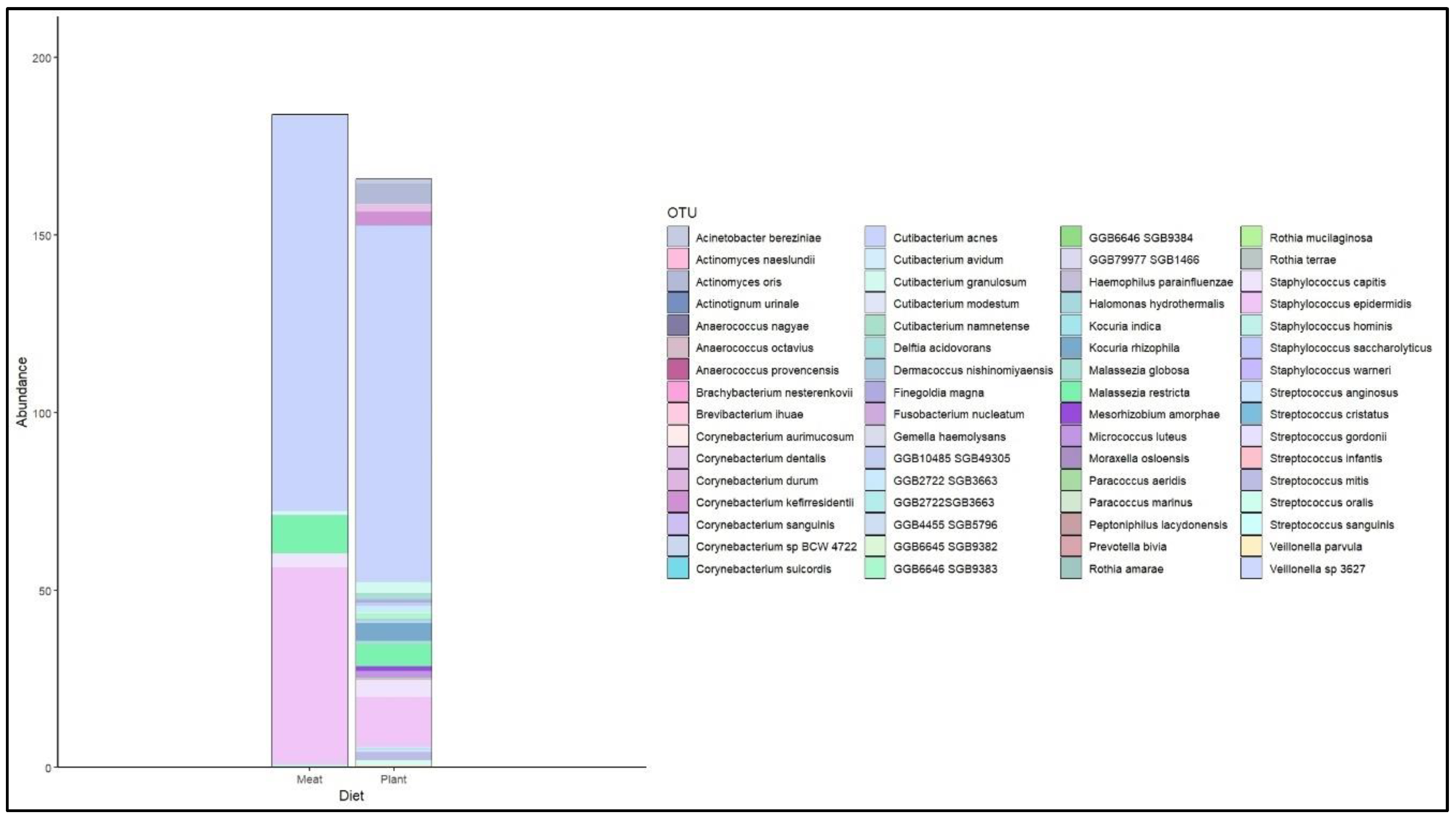

3.6. Skin Microbiome and Plant-Based Diet

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murphy B, Grimshaw S, Hoptroff M, Paterson S, Arnold D, Cawley A, Adams SE, Falciani F, Dadd T, Eccles R, Mitchell A, Lathrop WF, Marrero D, Yarova G, Villa A, Bajor JS, Feng L, Mihalov D, Mayes AE. Alteration of barrier properties, stratum corneum ceramides and microbiome composition in response to lotion application on cosmetic dry skin. Sci Rep. Nature Research; 2022 Dec 1;12(1). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagase S, Ogai K, Urai T, Shibata K, Matsubara E, Mukai K, Matsue M, Mori Y, Aoki M, Arisandi D, Sugama J, Okamoto S. Distinct Skin Microbiome and Skin Physiological Functions Between Bedridden Older Patients and Healthy People: A Single-Center Study in Japan. Front Med (Lausanne). Frontiers Media S.A.; 2020 Apr 8;7. [CrossRef]

- Dréno B, Araviiskaia E, Berardesca E, Gontijo G, Sanchez Viera M, Xiang LF, Martin R, Bieber T. Microbiome in healthy skin, update for dermatologists. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2016. p. 2038–2047. [PubMed]

- Sanford JA, Gallo RL. Functions of the skin microbiota in health and disease. Seminars in Immunology. 2013. p. 370–377. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roux PF, Oddos T, Stamatas G. Deciphering the Role of Skin Surface Microbiome in Skin Health: An Integrative Multiomics Approach Reveals Three Distinct Metabolite‒Microbe Clusters. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. Elsevier B.V.; 2022 Feb 1;142(2):469-479.e5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang BK, Lee S, Myoung J, Hwang SJ, Lim JM, Jeong ET, Park SG, Youn SH. Effect of the skincare product on facial skin microbial structure and biophysical parameters: A pilot study. Microbiologyopen. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2021 Oct 1;10(5). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcella P, Wijaya TH, Kurniawan DW. Narrative Review: Herbal Nanocosmetics for Anti Aging. JPSCR: Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Clinical Research. Universitas Sebelas Maret; 2023 Apr 10;8(1):63.

- Lindh JD, Bradley M. Clinical Effectiveness of Moisturizers in Atopic Dermatitis and Related Disorders: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 341–359. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansuri R, Diwan A, Kumar H, Dangwal K, Yadav D. Potential of Natural Compounds as Sunscreen Agents. Pharmacogn Rev. EManuscript Technologies; 2021 Jun 7;15(29):47–56. [CrossRef]

- Ying S, Zeng DN, Chi L, Tan Y, Galzote C, Cardona C, Lax S, Gilbert J, Quan ZX. The influence of age and gender on skin-associated microbial communities in urban and rural human populations. PLoS One. Public Library of Science; 2015 Oct 28;10(10). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harel N, Reshef L, Biran D, Brenner S, Ron EZ, Gophna U. Effect of Solar Radiation on Skin Microbiome: Study of Two Populations. Microorganisms. MDPI; 2022 Aug 1;10(8). [CrossRef]

- Skowron K, Bauza-kaszewska J, Kraszewska Z, Wiktorczyk-kapischke N, Grudlewska-buda K, Kwiecińska-piróg J, Wałecka-zacharska E, Radtke L, Gospodarek-komkowska E. Human skin microbiome: Impact of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on skin microbiota. Microorganisms. MDPI AG; 2021. p. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Balderas X, Peña-Peña M, Rada KM, Alvarez-Alvarez YQ, Guzmán-Martín CA, Sánchez-Gloria JL, Huang F, Ruiz-Ojeda D, Morán-Ramos S, Springall R, Sánchez-Muñoz F. Beneficial Effects of Plant-Based Diets on Skin Health and Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Nutrients. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna PC. Skin Microbiome as Years Go By. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. Adis; 2020. p. 12–17. [PubMed]

- Isler MF, Coates SJ, Boos MD. Climate change, the cutaneous microbiome and skin disease: implications for a warming world. International Journal of Dermatology. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2023. p. 337–345. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khmaladze I, Leonardi M, Fabre S, Messaraa C, Mavon A. The skin interactome: A holistic “genome-microbiome-exposome” approach to understand and modulate skin health and aging. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. Dove Medical Press Ltd; 2020. p. 1021–1040. [CrossRef]

- Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S, Deming CB, Davis J, Young AC, Bouffard GG, Blakesley RW, Murray PR, Green ED, Turner ML, Segre JA. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science (1979). 2009 May 29;324(5931):1190–1192. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li M, Budding AE, van der Lugt-Degen M, Du-Thumm L, Vandeven M, Fan A. The influence of age, gender and race/ethnicity on the composition of the human axillary microbiome. Int J Cosmet Sci. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2019;41(4):371–377. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith ML, O’Neill CA, Dickinson MR, Chavan B, McBain AJ. Exploring associations between skin, the dermal microbiome, and ultraviolet radiation: advancing possibilities for next-generation sunscreens. Frontiers in Microbiomes. Frontiers Media SA; 2023 Jun 23;2. [CrossRef]

- Grant GJ, Kohli I, Mohammad TF. A narrative review of the impact of ultraviolet radiation and sunscreen on the skin microbiome. Photodermatology Photoimmunology and Photomedicine. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willmott T, Campbell PM, Griffiths CEM, O’Connor C, Bell M, Watson REB, McBain AJ, Langton AK. Behaviour and sun exposure in holidaymakers alters skin microbiota composition and diversity. Frontiers in Aging. Frontiers Media SA; 2023;4. [CrossRef]

- Patra VK, Byrne SN, Wolf P. The skin microbiome: Is it affected by UV-induced immune suppression? Front Microbiol. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2016 Aug 10;7(AUG).

- Keshari S, Balasubramaniam A, Myagmardoloonjin B, Herr DR, Negari IP, Huang CM. Butyric acid from probiotic staphylococcus epidermidis in the skin microbiome down-regulates the ultraviolet-induced pro-inflammatory IL-6 cytokine via short-chain fatty acid receptor. Int J Mol Sci. MDPI AG; 2019 Sep 2;20(18). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuetz R, Claypool J, Sfriso R, Vollhardt JH. Sunscreens can preserve human skin microbiome upon erythemal UV exposure. Int J Cosmet Sci. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2024 Feb 1;46(1):71–84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalka S. New data on hyperpigmentation disorders. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2017. p. 18–21. [PubMed]

- Henning SM, Yang J, Lee RP, Huang J, Hsu M, Thames G, Gilbuena I, Long J, Xu Y, Park EHI, Tseng CH, Kim J, Heber D, Li Z. Pomegranate Juice and Extract Consumption Increases the Resistance to UVB-induced Erythema and Changes the Skin Microbiome in Healthy Women: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Sci Rep. Nature Publishing Group; 2019 Dec 1;9(1). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad T, Kohli I, Hamzavi I. The role of sunscreen in melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Indian Journal of Dermatology. Wolters Kluwer Medknow Publications; 2020. p. 5–10. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriu PA, Iker B, Malik K, Leung H, Mohn WW, Hillebrand GG. New Insights into the Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors That Shape the Human Skin Microbiome. 2019; Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Edslev SM, Agner T, Andersen PS. Skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. Medical Journals/Acta D-V; 2020;100(100-year theme Atopic dermatitis):358–366. [PubMed]

- Fölster-Holst R. The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis – correlations and consequences. JDDG - Journal of the German Society of Dermatology. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2022. p. 571–577. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerre RD, Bandier J, Skov L, Engstrand L, Johansen JD. The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. British Journal of Dermatology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2017. p. 1272–1278. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadka VD, Key FM, Romo-González C, Martínez-Gayosso A, Campos-Cabrera BL, Gerónimo-Gallegos A, Lynn TC, Durán-McKinster C, Coria-Jiménez R, Lieberman TD, García-Romero MT. The Skin Microbiome of Patients With Atopic Dermatitis Normalizes Gradually During Treatment. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2021 Sep 24;11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Cruz S, Orozco-Covarrubias L, Sáez-de-Ocariz M. The Human Skin Microbiome in Selected Cutaneous Diseases. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicol NH, Rippke F, Weber TM, Hebert AA. Daily Moisturization for Atopic Dermatitis: Importance, Recommendations, and Moisturizer Choices. Journal for Nurse Practitioners. Elsevier Inc.; 2021 Sep 1;17(8):920–925. [CrossRef]

- Pace LA, Crowe SE. Complex Relationships Between Food, Diet, and the Microbiome. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. W.B. Saunders; 2016. p. 253–265. [PubMed]

- Mahmud MR, Akter S, Tamanna SK, Mazumder L, Esti IZ, Banerjee S, Akter S, Hasan MR, Acharjee M, Hossain MS, Pirttilä AM. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes. Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 2022. [PubMed]

- Thye AYK, Bah YR, Law JWF, Tan LTH, He YW, Wong SH, Thurairajasingam S, Chan KG, Lee LH, Letchumanan V. Gut–Skin Axis: Unravelling the Connection between the Gut Microbiome and Psoriasis. Biomedicines. MDPI; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lee SY, Lee E, Park YM, Hong SJ. Microbiome in the gut-skin axis in atopic dermatitis. Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Research. Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Clinical Immunology; 2018. p. 354–362. [CrossRef]

- Szántó M, Dózsa A, Antal D, Szabó K, Kemény L, Bai P. Targeting the gut-skin axis—Probiotics as new tools for skin disorder management? Exp Dermatol. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2019 Nov 1;28(11):1210–1218. [PubMed]

- Prescott SL, Larcombe DL, Logan AC, West C, Burks W, Caraballo L, Levin M, Etten E Van, Horwitz P, Kozyrskyj A, Campbell DE. The skin microbiome: Impact of modern environments on skin ecology, barrier integrity, and systemic immune programming. World Allergy Organization Journal. BioMed Central Ltd; 2017. [CrossRef]

- Bouslimani A, Da Silva R, Kosciolek T, Janssen S, Callewaert C, Amir A, Dorrestein K, Melnik A V., Zaramela LS, Kim JN, Humphrey G, Schwartz T, Sanders K, Brennan C, Luzzatto-Knaan T, Ackermann G, McDonald D, Zengler K, Knight R, Dorrestein PC. The impact of skin care products on skin chemistry and microbiome dynamics. BMC Biol. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2019 Jun 12;17(1). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Míguez, A., Beghini, F., Cumbo, F. et al. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat Biotechnol 41, 1633–1644 (2023). [CrossRef]

| Sample | Gender | Skin Type | Diet | Moisturizer | Sunscreen | Sun Exposure* | Shannon Diversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM1 | Female | Oily | Plant | Yes | Yes | Low | 2.12 |

| SM2 | Female | Dry | Meat | Yes | Yes | Moderate | 0.93 |

| SM3 | Female | Dry | Meat | Yes | Yes | Moderate | 0.94 |

| SM4 | Male | Dry | Meat | Yes | No | High | 2.4 |

| SM5 | Female | Dry | Meat | Yes | No | Low | 0.43 |

| SM6 | Female | Dry | Meat | Yes | Yes | Moderate | 1.02 |

| SM7 | Male | Dry | Meat | No | No | High | 1.04 |

| SM8 | Female | Oily | Meat | Yes | No | Low | 1.32 |

| SM9 | Female | Dry | Meat | Yes | No | Low | 1.14 |

| SM10 | Male | Dry | Meat | Yes | No | Moderate | 0.99 |

| SM11 | Male | Oily | Meat | Yes | No | Moderate | 2.73 |

| SM12 | Female | Oily | Meat | Yes | Yes | Low | 0.61 |

| SM13 | Female | Oily | Plant | Yes | Yes | Moderate | 1.27 |

| SM14 | Female | Dry | Meat | Yes | No | Moderate | 0.91 |

| SM15 | Male | Dry | Meat | No | No | High | 1.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).