Introduction

Sexism is defined as a form of discrimination based on differences, whether real or perceived, between men and women. This problem has an impact in different contexts, both private and public, and is expressed through beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors (Checa-Romero et al., 2021). It can also be defined as the belief that masculinity is superior to femininity, which creates a hierarchy between genders (Cáceres Campoverde, 2025).

Sexism is a system that perpetuates gender inequality. It manifests itself in four main ways: gender-based violence, segregation, exploitation, and domination (Checa-Romero et al., 2021).

In turn, (Fernández García et al., 2022) notes that sexism can also be presented in a covert manner, but because of its benevolent tone, it does not cause rejection in contrast to obvious hostile treatment, which hinders its recognition. It is estimated that people’s beliefs are ambiguous regarding tolerance of sexism.

In Peru, a study conducted by (Manrique Tapia & Flores Monzon, 2021) with 93 adolescents aged 15 to 19 indicates a direct relationship between intimate partner violence and sexism. It was found that 51.2% showed a high level of benevolent sexism, while 25.8% showed a medium-low level of hostile sexism. The results are associated with the fact that 29.0% of the population has suffered some form of intimate partner violence and 28.0% has committed it.

In this way, our research will provide evidence of the validity and reliability of an inventory on the prevalence of sexist thoughts among Peruvian adolescents, providing a tool that is appropriate to the cultural context. In turn, the research will serve as a valuable precedent for future studies in populations with similar characteristics, facilitating the objective assessment of sexist thoughts. Considering the impact of sexism on the mental health, academic performance, and social development of adolescents, having a psychometrically sound instrument is essential for designing relevant interventions.

Likewise, it is considered appropriate to create and analyze the psychometric properties of an inventory for adolescents based on the results obtained in Peruvian society, so that an objective metric adjusted to the population of this study can be obtained.

The research is justified primarily because it seeks to promote a society where adolescents interact in a fair, peaceful, respectful, and inclusive manner, which leads to living free from sexist and discriminatory comments, as well as maintaining relationships with the aim of prioritizing the well-being of each individual, thereby significantly reducing cultural gaps. In practical terms, it will allow the central theme to be explored in the sociocultural sphere, which will raise awareness of the issue at both the local and national levels. Therefore, it will be of great help in developing strategies and different policies that will address this problem in the various institutions whose purpose is to promote different environments that are inclusive and respectful of all. Furthermore, in the social sphere, this study will explore a topic of great cultural and social relevance, with the aim of validating the different experiences of those who have suffered different types of discrimination in order to promote social change that benefits everyone.

Given the above, the general objective is to determine the construction and psychometric properties of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts in adolescents in Trujillo, 2025, and the specific objectives are to construct the specification table, establish evidence of validity based on the content of the inventory, establish a descriptive analysis of the items in the inventory, establish evidence of validity based on the internal structure of the inventory, establish evidence of reliability based on the internal consistency of the inventory, and construct the norms and cut-off points for the scale.

Method

Study Desing

The research design is non-experimental and instrumental, as the variables are not deliberately manipulated, but rather seeks to create an instrument that measures the proposed theoretical dimensions in a given sample. This type of design is suitable for initial psychometric studies, as it allows for the examination of how the constructs to be measured are conceptually expressed without interfering with them (Veloza Gamba, 2023).

Procedure and Participants

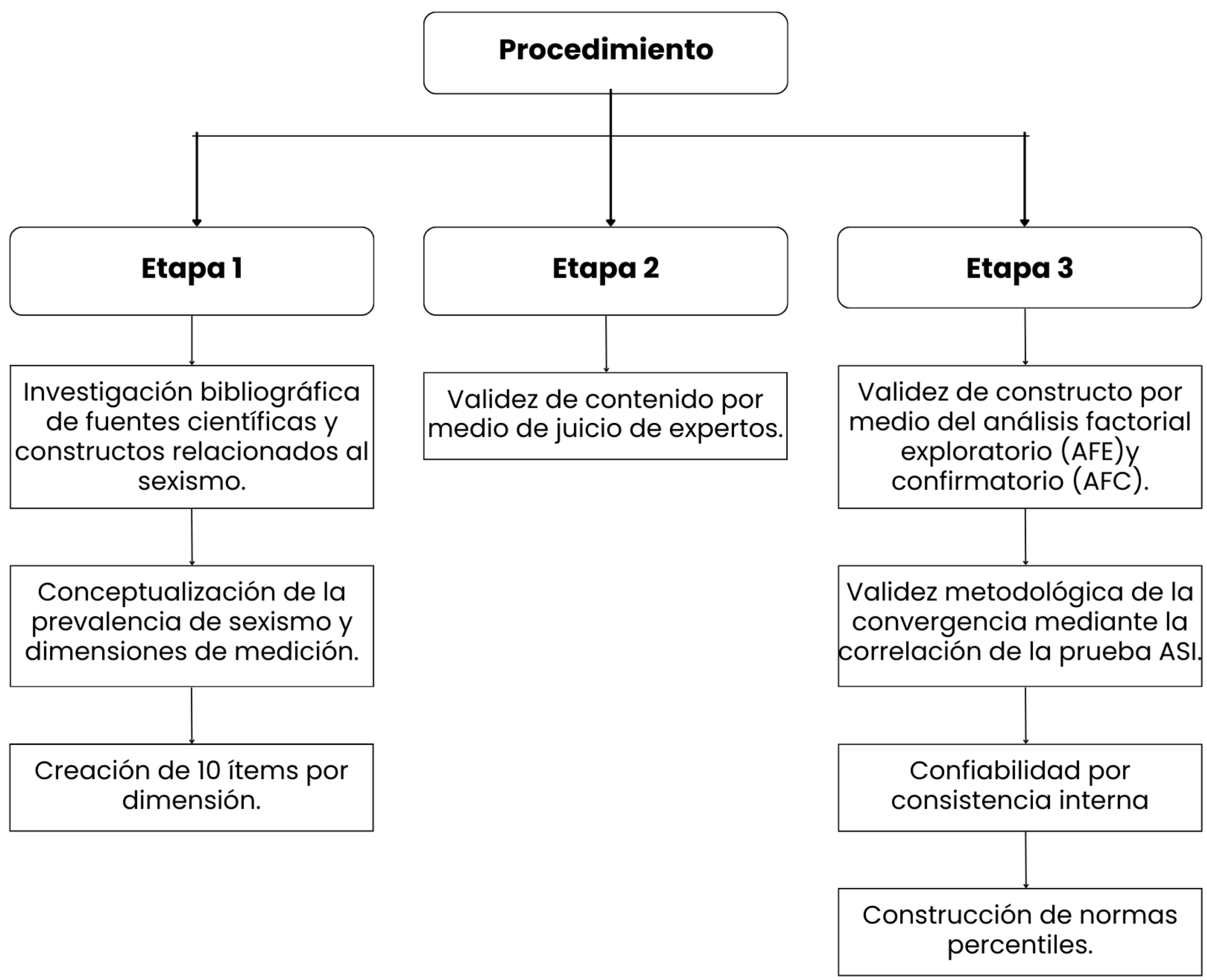

In conducting this research, rigorous processes were carried out to safeguard the validity and reliability of the Sexist Thoughts Prevalence Inventory. The procedures were sequenced and can be seen in

Figure 1. Overall, the population consisted of 505 adolescents, who were selected as participants using strictly followed inclusion and exclusion criteria. These criteria were useful in ensuring that the population used was representative. The structured and methodical process that was carried out supports the stability of the construct.

First Phase: Development of Items

To begin the research, a preliminary version of the inventory was constructed using various scientific sources and analyzing similar constructs developed previously to observe how the analysis could be appropriately conducted. Based on the observations, a conceptual definition of the prevalence of sexist thoughts was developed. Drawing on two theories, ambivalent sexism and social identity theory, five dimensions were constructed, with 10 items per dimension; that is, a total of 50 items. However, after analysis by nine experts, 46 items remained, which were applied in the exploratory factor analysis. Nevertheless, for the confirmatory factor analysis after exhaustive data analysis to ensure that the construct was valid and reliable, unnecessary items were discarded in order to consolidate a parsimonious construct. Thus, only 14 items remained, 7 items belonging to the dimension Hierarchies and social gender identity and the remaining 7 to Affective and behavioral expectations towards the other gender. Thus, the final version of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts (IPPS) has 14 items and two dimensions.

Second Phase: Content Validity of Items

In the second phase, concerning evidence of content validity, expert judgment was used, involving nine experts in psychology with master’s or doctoral degrees, who reviewed each of the items and also evaluated their clarity, consistency, relevance, and appropriateness of each item in order to evaluate the variable of sexist thoughts in adolescents in Trujillo. Items that achieved a value greater than 0.80 on the Aiken V test were considered adequate.

The measurement scale used in this research was interval, which indicates that the distance or value between one component and another is equal, thus making it possible to evaluate the elements consistently (Arias Gonzáles, 2021); as well as a Likert-type rating scale with four response options: 1 = Never, 2 = Almost never, 3 = Almost always, and 4 = Always.

Third Phase: Evaluation of Psychometric Properties

In the third phase, the psychometric properties of the IPPS were analyzed. In this part, the construct validity, convergent validity, and reliability of the instrument were assessed. he total population consisted of 505 adolescents from Trujillo aged between 12 and 19, most of whom were female (50.3%), although this did not represent a significant difference compared to males (49.7%). The average age was 14.8 years with a SD = 1.6, indicating that most of the population was between 13 and 16 years old.

The inclusion criteria indicated that participants must be between 12 and 19 years old, of either gender, enrolled in grades 1 through 5 of secondary school during the current year 2025, Peruvian nationals born in Trujillo who can speak and read Spanish appropriately in order to correctly mark the items on the questionnaire. Likewise, participants with special educational needs (such as language or cognitive disabilities) and/or serious psychological or emotional disorders were excluded, as were those who did not have the duly signed informed consent of their guardians or the educational institution where they were studying, and those who had participated in a similar study, so as not to alter the results.

The sample population formed two evaluation stages. In the first part, 250 adolescents participated in the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), of which those aged 15 years prevailed most frequently (SE = 1.25), with males belonging to this group in the majority (SE = 0.501). In the second stage, referring to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), a larger population aged 15 years (SD = 1.81) was observed, but unlike the first data processing, the population was mainly composed of females (SD = 0.501). The correlation between age and gender prevalence consistently supports the comparability between both groups for optimal data analysis.

This research involved a sample of 505 adolescents from the city of Trujillo, divided into three groups: 50 students for the pilot sample, 200 for the exploratory factor analysis, and 305 for the confirmatory factor analysis (Gutiérrez Prieto et al., 2022). The sampling method was non-probability convenience sampling (Hernández González, 2021).

The application was carried out in two educational institutions, one private and one public. The tests were distributed in physical format with prior authorization from the guardians through a written informed consent form in physical format. In addition, the degrees in the exploratory and confirmatory application were taken into consideration in order to find an adjustment between the estimated population.

Before completing the questionnaires, the population was instructed on how to do so correctly, indicating that they should read the items carefully and judge how often each statement matched their thoughts. In addition, they were instructed to observe the following classification scale for their answers, marking the category corresponding to their preference with an X or a circle, with an approximate time of 15 to 20 minutes.

After applying the instrument, upon receipt, it was verified that all items had been completed and that no items had been marked twice. Questionnaires with inconsistent response patterns would not be considered; however, this was not evident, so all 505 instruments applied were used for data analysis.

Ambivalent Sexism Scale (ASI)

The Ambivalent Sexism Scale (ASI) was an instrument used to measure sexist attitudes in the population evaluated. It consisted of 20 items distributed on a Likert scale with five response options: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neither agree nor disagree (3), agree (4), and strongly agree (5). This questionnaire assessed two main dimensions: hostile sexism (items 1–10), related to negative attitudes toward women who challenged traditional roles, and benevolent sexism (items 11–20), based on paternalistic stereotypes and protective attitudes toward women. The total score was obtained by adding the values for each dimension separately. High scores indicated a greater presence of sexist attitudes, while low scores reflected less acceptance of such beliefs. The scale showed adequate levels of internal consistency (α > 0.80).

Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts (IPPS-25)

The IPPS-25 was an instrument designed to measure the frequency of sexist thoughts in secondary school adolescents, understood as beliefs and attitudes that reinforce gender inequality. Initially, it consisted of 46 items organized into five dimensions: beliefs about gender roles and capabilities, power and control relationships between genders, gender group identification and favoritism, justification of sexist prevalence, and affective and behavioral expectations toward the other gender.

Responses were recorded on a four-point Likert scale: never (1), almost never (2), almost always (3), and always (4). The total score was obtained by adding the values for each item, so that high scores indicated a greater prevalence of sexist thoughts, while low scores reflected a lower acceptance of discriminatory beliefs. The theoretical range was between 46 points (minimum presence of sexist thoughts) and 184 points (maximum presence).

Subsequently, through the corresponding psychometric analyses, the scale was refined, resulting in 14 items grouped into two dimensions: gender hierarchy and social identity, and affective and behavioral expectations toward the other gender. This reduced version showed adequate levels of validity and reliability, achieving internal consistency coefficients above 0.80.

Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis of the ASI items was performed to assess the distribution and adequacy of the data. Means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis were calculated using SPSS software (version 27). In addition, multivariate normality was verified using the Mardia test, considering p values > 0.05 as indicative of normal distribution.

The suitability for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was assessed using Bartlett’s sphericity test and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index. The EFA was performed with a polychoric matrix and the least squares method, applying oblique rotation (Oblimin) as the factors were correlated. The KMO index was greater than 0.80 and Bartlett’s test was significant (p < 0.001). Items with factor loadings less than 0.30 were eliminated, ultimately yielding a two-dimensional structure: hostile sexism and benevolent sexism, which explained a significant percentage of the total variance.

Subsequently, the factor structure was verified using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The fit indices were considered adequate when the CFI and TLI were greater than 0.90, while the RMSEA and SRMR remained below 0.08. Likewise, the chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio was evaluated, with values less than 3.0 being acceptable. This procedure was carried out using JASP (version 0.19.0) and AMOS (version 30) software.

Concurrent validity was determined by correlating the dimensions of hostile and benevolent sexism with other psychosocial variables collected in the study, which confirmed the expected relationship between these attitudes and the factors of interest.

The reliability of the instrument was examined through internal consistency, calculating Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients, which showed values above 0.80 in both dimensions, demonstrating stability and robustness in the measurement.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in strict compliance with the ethical guidelines of César Vallejo University, as established in the Guide for the preparation of work leading to degrees and qualifications, approved by Resolution No. 062-2023-VI-UCV. Likewise, the research protocol was submitted for evaluation and obtained the approval of the university’s Ethics Committee.

Se garantizó el principio de autonomía mediante el consentimiento informado, el cual fue firmado por los participantes antes de iniciar la evaluación. Se brindó información clara sobre los objetivos, duración, posibles riesgos y beneficios, así como la posibilidad de retirarse del estudio en cualquier momento sin repercusiones negativas.

Similarly, the confidentiality and protection of participants’ identities were ensured by coding and storing the information anonymously and under the custody of the principal investigator. In addition, the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence were respected, avoiding situations that could cause discomfort or emotional distress during the administration of the questionnaires.

Finally, the researchers acted in accordance with the principles of truthfulness, honesty, and transparency in the collection, analysis, and presentation of results, avoiding bias, manipulation, or plagiarism, thereby ensuring the scientific integrity of the study.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

Table 1 shows that the study sample has a similar gender distribution, with a slight predominance of females at 50.3% (n = 254). In terms of age, the predominant range is 16, with 21.4% (n = 108), followed by 15, with 19.8% (n = 100). The predominant marital status was single, with 100% (n = 505). The average age of the participants was 14.8 years.

Content Validity Analysis

Table 2 presents the content validity of items j4 to j13 of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts (IPPS-25), evaluated by a group of nine expert judges using Aiken’s V coefficient, considering the criteria of clarity, coherence, and relevance. The results obtained indicate that all items achieved values above .80, which, together with confidence intervals within acceptable ranges, supports the suitability and consistency of the items evaluated. Consequently, it can be stated that the items analyzed in this dimension have adequate content validity, ensuring that they are clear, coherent, and relevant to the variable being measured.

Table 3 presents the content validity of items e1 to e14 of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts (IPPS-25), which were evaluated by a group of nine expert judges using Aiken’s V coefficient. This evaluation is based on criteria of clarity, consistency, and relevance. The results obtained indicate that all items exceed values of .80, which, added to the confidence intervals within acceptable ranges, supports the suitability and consistency of the items analyzed. Therefore, it can be stated that the items in this dimension have adequate content validity, which guarantees their clarity, consistency, and relevance for the variable to be measured.

Descriptive Analysis of the Items

Table 4 shows the analyses relating to the items corresponding to the Hierarchies and Social Gender Identity dimension of the IPPS-25. With regard to the frequency distribution, there is significant variability between the items. For example, item j7 accounts for 43.0% of responses in category 2, while item j13 shows a more balanced trend, with percentages distributed between 14.5% and 32.5% in the four response categories (Chávez-Ayala et al., 2024)

. The means ranged from 2.29 (item j7) to 2.71 (item j13), suggesting a spectrum ranging from slight disagreement to moderate agreement. Standard deviations ranged from 0.865 to 1.11, all within the recommended range (≤ 1.5), implying adequate stability in the responses obtained (Calvete et al., 2021). With regard to asymmetry (g1), values ranged from −0.259 to 0.214, while kurtosis (g2) varied between −1.34 and −0.597. These findings remain within the acceptable range of ±1.5, indicating the absence of extreme biases and adequate data distributions (Calvete et al., 2021). With regard to the corrected homogeneity index (IHC), the items presented values ranging from 0.3522 (j8) to 0.671 (j9), generally exceeding the threshold of 0.30, which indicates adequate internal consistency. Similarly, the communalities (h2) ranged from 0.418 (j7) to 0.656 (j12), demonstrating an appropriate relationship between the items and the general construct of the dimension (Calvete et al., 2021).

Table 5 presents the analyses of the items related to the dimension of Affective and Behavioral Expectations toward the Other Gender of the IPPS-25. Regarding the frequency distribution, there is evidence of variability in the responses. For example, item e3 shows a concentration of 43.5% in category 3, indicating a clear tendency toward moderate agreement. In contrast, item e10 exhibits a more dispersed distribution of responses, with a predominance in categories 1 (32.5%) and 2 (32.0%), suggesting higher levels of disagreement (Vargas Vargas & Vásquez Huamán, 2022). The means ranged from 2.14 (item e10) to 2.73 (item e3), showing a range from slight disagreement to moderate agreement. The standard deviation ranged from 0.88 to 1.06, which are appropriate values as they are below the threshold of 1.5, indicating stability in the responses (Cortés Rodríguez, 2023). With regard to asymmetry (g1), values ranged from −0.352 to 0.39, while kurtosis (g2) ranged from −1.17 to −0.668. These results are in line with the suggested range of ±1.5, suggesting the absence of extreme biases and adequate distributions (Vargas Vargas & Vásquez Huamán, 2022). In relation to the corrected homogeneity index (IHC), the values vary between 0.222 (e3) and 0.5663 (e11), exceeding the minimum threshold of 0.30 in all cases, which demonstrates adequate internal consistency. With regard to communalities (h2), these ranged between 0.4 (e2) and 0.764 (e3), confirming an appropriate relationship between the items and the general construct of the dimension (Cortés Rodríguez, 2023).

Evidence of Internal Structure Validity

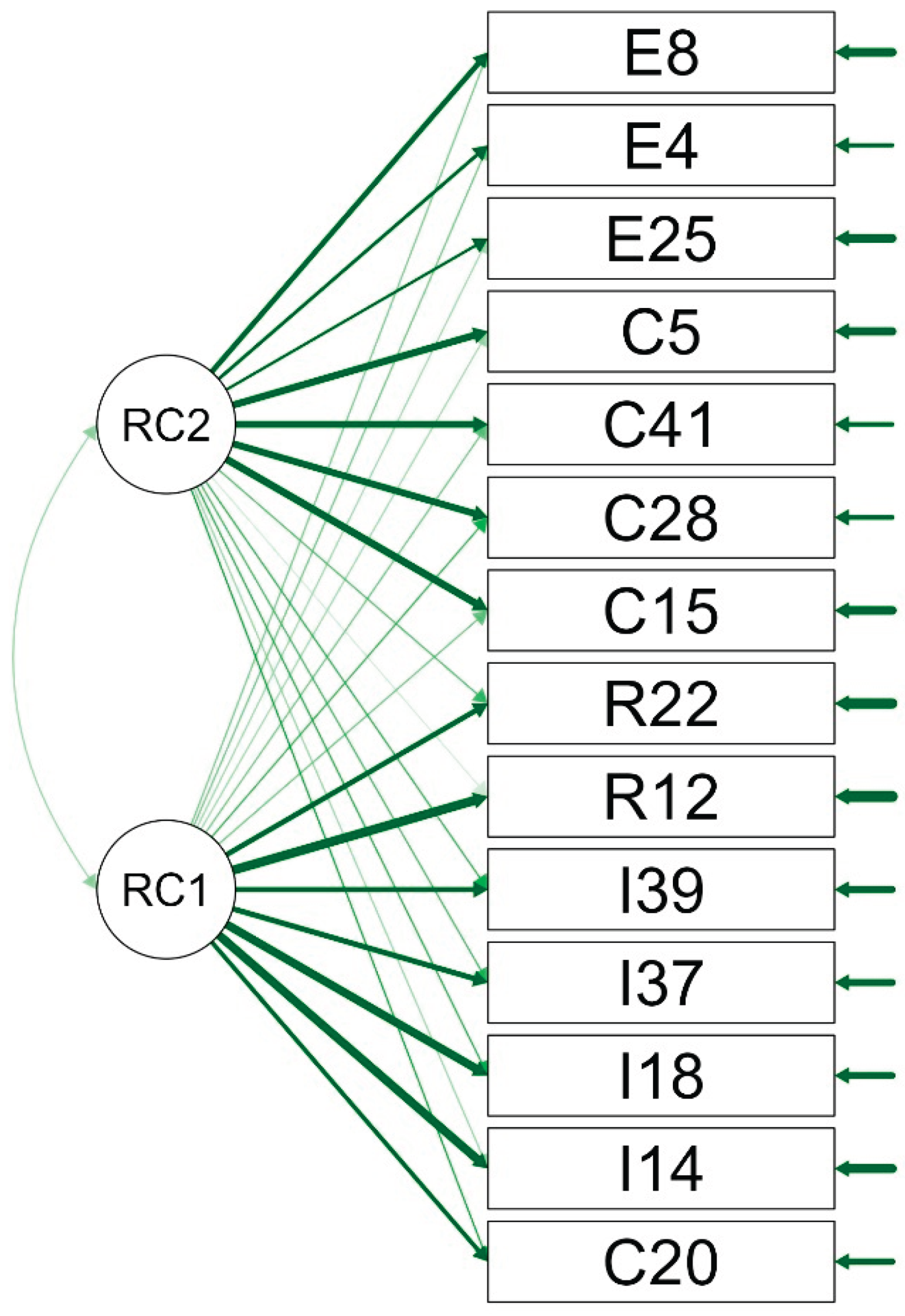

Table 6 presents the findings of the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) carried out on the IPPS-25. In an initial phase, a model composed of four factors with a total of 40 items was analyzed, which showed an adequate fit to the proposed theoretical structure, manifested in a χ² = 745.643, df = 626, p < .001. This result was complemented by indices that support the validity of the model, such as SRMR = 0.043, RMSEA = 0.031, CFI = 0.949, and TLI = 0.935. These values are within the recommended ranges, suggesting a good overall fit of the model; however, items with cross-factor loading were identified, which could complicate the clear differentiation of each of the dimensions separately (Chávez-Ayala et al., 2024). Next, a comparison was made of a two-factor model comprising 14 items, whose results also showed satisfactory indicators: χ² = 90.741, df = 64, p = .016, with values of SRMR = 0.042, RMSEA = 0.045, CFI = 0.957, and TLI = 0.939. This model, despite being more simplified, preserves adequate levels of fit, with CFI and TLI indices slightly higher than those of the original model, suggesting a simpler structure without compromising the quality of the fit (Casas-Caruajulca et al., 2021). Together, both models provide strong evidence of factorial validity; however, the two-factor model with 14 items is more efficient, improving fit and simplifying the structure without compromising consistency.

Table 7 shows the factor loadings associated with the two factors obtained through exploratory factor analysis. Factor 1, called Gender Hierarchies and Social Identity, groups items J4, J5, J7, J12, J9, J13, and J8, with factor loadings ranging from 0.456 to 0.740. These values suggest that the items maintain an appropriate relationship with the factor, with the highest loadings corresponding to items J4 (0.740) and J5 (0.708), implying a strong association with this dimension.

Factor 2, called Affective and behavioral expectations toward the opposite gender, comprises items E6, E2, E11, E14, E3, E1, and E10, whose factor loadings range from 0.367 to 0.633. On this occasion, the item with the highest weight is E6, with a loading of 0.633, while the item that contributes the least is E10, with a loading of 0.367. This finding indicates that, although the relationships are moderate, the items exhibit adequate internal consistency with the dimension being evaluated.

No cross-factor loadings were identified in either factor, reinforcing the clarity in the distinction between the two dimensions and the absence of ambiguity in the connection between the items and their respective constructs.

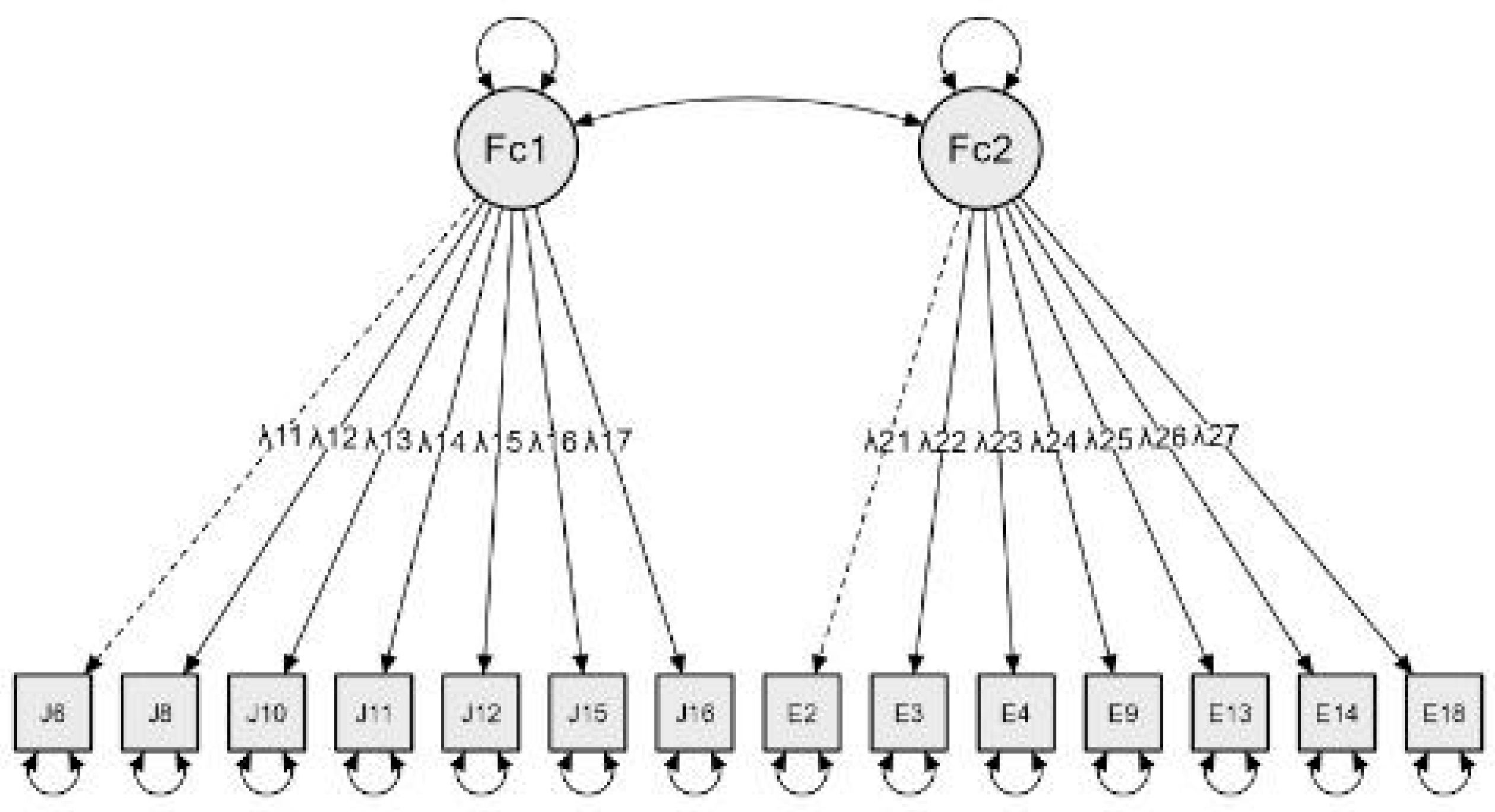

Diagram of the Factors That Make Up the Instrument

The structure of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts (IPPS-25) is observed, consisting of two dimensions: gender hierarchies and social identity, and affective and behavioral expectations toward the opposite gender. These two dimensions represent the two factors that make up the instrument.

Table 9 shows the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the Sexist Thoughts Prevalence Inventory (IPPS-25): one with a single factor and another with two additional dimensions. The unidimensional model did not show significance; however, the two-dimensional model showed statistical significance in the chi-square test. Nevertheless, additional fit indicators favored the two-dimensional model, thus exhibiting a better fit (X2/gl < 0.06, CFI = 0.949, TLI = 0.939, SRMR = 0.048, RMSEA = 0.038). In comparison, the one-dimensional model showed a lower fit (X2/df < .001, CFI = 0.680, TLI = 0.622, SRMR = 0.090, RMSEA = 0.096). Based on the data, it is confirmed that the exploratory factor analysis model of the Sexist Thoughts Prevalence Inventory (IPPS-25) has two factors and 14 items.

Table 9.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts (IPPS).

Table 9.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts (IPPS).

| Model |

X2 |

gl |

CFI |

TLI |

SRMR |

RMSEA |

| Unidimensional (14 items) |

292.760 |

77 |

0.680 |

0.622 |

0.090 |

0.096 |

| 2 factors (14 items) |

110.295 |

79 |

0.949 |

0.939 |

0.048 |

0.038 |

Table 10.

Factor loadings of the two dimensions of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts (IPPS).

Table 10.

Factor loadings of the two dimensions of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts (IPPS).

| Items |

Hierarchies and social gender identity |

Emotional and behavioral expectations toward the opposite gender |

| Feminism has gone too far and harms men (J4) |

0.740 |

|

| Today, men are losing rights because of feminism (J5) |

0.708 |

|

| New equality policies harm men (J7) |

0.693 |

|

| Defending men’s rights is frowned upon, and that is not fair (J12) |

0.522 |

|

| The rules should not be changed because of feminist complaints (J9) |

0.505 |

|

| Today, men can no longer express themselves freely without being judged (J13) |

0.500 |

|

| Women want more privileges than rights (J8) |

0.456 |

|

| Women are naturally sweeter and therefore should take care of others (E6) |

|

0.633 |

| A man is only a real man if he always takes care of and provides for a woman (E2) |

0.618 |

| Women should be protected by men (E11) |

0.601 |

| Women are more valuable when they are delicate and kind (E14) |

0.600 |

| Women look better when they act tenderly (E3) |

0.513 |

| Men should be the financial providers for the household (E1) |

0.404 |

| Women should prioritize their families over their careers (E10) |

0.367 |

Extraction: minimum residuals, rotation: varimax

Cumulative explained variance: 40%

Bartlett’s sphericity test: p<0.01

Sample adequacy test (KMO): 0.838 |

Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the Sexist Thoughts Prevalence Inventory (IPPS), which consists of two dimensions: social comparison and behavioral reaction. These two dimensions represent the two factors that make up the instrument.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor model of the Sexist Thoughts Prevalence Inventory (IPPS).

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor model of the Sexist Thoughts Prevalence Inventory (IPPS).

Table 11 shows the results of the convergent validity analysis of the inventory (IPPS-25), using the Adolescent Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI) as an external variable. Spearman’s correlation coefficient indicated a value of ρ = 0.535 (p < .001) based on a sample of 305 participants, indicating a positive and statistically significant correlation between the two measures.

Similarly, the value of r² = 0.345 suggests that approximately 34.5% of the variance in the inventory (IPPS-25) is justified by its relationship with the external scale, indicating a moderate level of association.

Overall, the results obtained support the convergent validity of the (IPPS-25), demonstrating that the instrument has an adequate capacity to assess the construct of prevalence of sexist thoughts, in line with other measures that have been established previously.

Table 12 shows the reliability coefficients for internal consistency Alpha (α) and Omega (ω); a value of ω of .749 was obtained on the total scale, while in terms of dimensions, social comparison obtained a ω= .495 and α = .719, and behavioral reaction obtained a ω=.728 α = .91; These omega and alpha reliability indices are acceptable values, as they are between .85 and .93.

Percentile Standards

Table 13 presents the percentile norms for the IPPS-25 in a sample of 305 adolescents. In the Hierarchy dimension, a mean of 17.57 was obtained, with a standard deviation of 4.141, a minimum of 7, a maximum of 28, and a mode of 19. In the Expectation dimension, the mean was 17.50, with a standard deviation of 4.092, a minimum of 7, a maximum of 27, and a mode of 15. Finally, the overall total average was 37.07, with a standard deviation of 6.658, a minimum of 16, a maximum of 55, and a mode of 33.

In relation to the percentiles, the highest score in the 100th percentile was 55 in the overall total, while the 50th percentile had a value of 35 points. At the lower end, the 5th percentile obtained a total of 23.30 points. This information facilitates the observation of the distribution of scores in each of the dimensions, as well as in the overall inventory score.

Individuals who score high on the Hierarchies and Gender Social Identity dimension tend to reproduce unequal power dynamics between genders. They are distinguished by exhibiting behaviors that negatively impact others, such as defamation, sabotage, derogatory comments, hostility, and gender-based competitiveness.

People who score high on the dimension of affective and behavioral expectations toward the opposite gender exhibit attitudes and behaviors that propagate stereotypes and comparisons between genders. This phenomenon involves evaluating and assessing others based on physical, intellectual, or achievement distinctions, perpetuating differentiated expectations regarding the behavior that each gender should adopt.

Discussion

The prevalence of sexist thoughts refers to the frequency with which cognitive expressions of gender discrimination manifest themselves in a population. This phenomenon may be linked to the perpetuation of notions of male superiority, which foster inequality in contemporary society. For this reason, it is essential to have an objective and validated instrument within the sociocultural context of the Peruvian population that can be used to support various research projects related to the variable in question. Consequently, a study was conducted to determine the construction and psychometric properties of the Sexist Thoughts Prevalence Inventory (IPPS) in adolescents in the city of Trujillo, 2025. The results of this research provided the following data:

The first objective achieved was the development of a table of specifications, which included both the consistency matrix and the operationalization of the variable, allowing the prevalence of sexist thoughts to be established as the main variable of the study. Its dimensions and indicators were also identified. Fifty items were created, distributed across five dimensions: Beliefs about gender roles and capabilities, Power and control relationships between genders, Identification and favoritism of gender groups, Justification of sexist prevalence, and Affective and behavioral expectations toward the other gender, resulting from the interaction between Ambivalent Sexism Theory (Glick & Fiske, 1996) and Social Identity Theory (Hogg, 2021). An interval scale was used as a measurement tool, complying with the statistical requirements necessary to ensure the validity and reliability of the tests, in accordance with the theoretical model of the variable in question (Rodríguez et al., 2021). Likewise, with the aim of reducing bias and the influence of social desirability among participants, an instrument was developed with items distributed randomly and organized by dimensions. It was ensured that the items were clear, simple, and easily understandable, in addition to including an approximate number of items for each dimension in order to ensure the relevance of the items on the scale.

The second objective was to evaluate content validity using Aiken’s V coefficient based on the criteria of nine judges. Four proposed items were eliminated, and in each case aspects such as clarity, relevance, consistency, and significance were verified. The values obtained ranged from a minimum of 0.89 to a maximum of 1, indicating that acceptable and valid values were met (Chávez-Ayala et al., 2024). Consequently, our research shows that all items fall within an acceptable range. Even so, one item has been modified to use more accessible language that is understandable to adolescents and more closely related to the variable that is theoretically intended to be measured, in accordance with the guidelines proposed by the American Psychological Association (APA) (Rodríguez et al., 2021)

Likewise, the third objective consisted of conducting a descriptive analysis of the elements of the instrument, following the information provided by the theories mentioned above. Two dimensions were established: the first referred to gender hierarchies and social identity (with items 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 12, and 13), and the second related to affective and behavioral expectations toward the other gender (with items 1, 2, 3, 6, 10, 11, and 14). The results showed maximum frequency values of up to 43.0%, without exceeding 80%, suggesting that these findings can be considered adequate (Vargas Vargas & Vásquez Huamán, 2022). With regard to asymmetry and kurtosis, results were observed that fell within the ranges of +/- 1.5, indicating that the responses are normally distributed (Cortés Rodríguez, 2023). On the other hand, the homogeneity index exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.30 in all cases, which is considered acceptable, except for item e3 (Calvete et al., 2021). Likewise, the communality showed scores above .40, which shows a relevant relationship between the items and their respective factors (Calvete et al., 2021).

In accordance with the fourth objective, which proposes exploratory factor analysis to corroborate the coherent organization of the dimensions presented in the construct, it was found that the items measure what is expected according to the theoretical model of ambivalent sexism and social identity theory. To carry out the proposed study, the population consisted of 200 adolescents, and a large part of the items initially projected were deleted to maintain validity in the internal structure; according to (Ondé & Alvarado, 2022), Item refinement allows for greater precision in the measurement of variables, as it controls the variance between factors. Through this process, the internal structure was consolidated from 50 items in 5 dimensions, with 10 items in each dimension, to 14 items in 2 dimensions, with 7 items in each dimension. The exploratory factor analysis found an adequate overall fit with 14 items, indicating: χ² = 90.741, gl = 64, p = .016, with values of SRMR = 0.042, RMSEA = 0.045, CFI = 0.957, and TLI = 0.939. It highlights parsimony and simplicity without losing validity. Regarding factor loading, there is no evidence of cross-loading, and the items are mostly > 0.50, exhibiting a favorable association of dimensions. This finding contrasts with that of (Galván-Cabello, 2021), who conducted a similar study based on the theory of ambivalent sexism, initially proposed 20 items, which were retained; that is, it was not necessary to delete any items. They considered two dimensions: “benevolent sexism” and “hostile sexism.” The fit indices showed viability, reflecting: p < .001, indicating significance, KMO (.91) exceeding .80, and GFI = .99, which is very close to 1, showing a very good fit. Thus, it is estimated that the contrasted model has greater psychometric properties for evaluation.

Regarding confirmatory factor analysis, significant chi-square data were observed; however, the fit indices are adequate, and therefore it is considered acceptable (X2/df < 0.06, CFI = 0.949, TLI = 0.939, SRMR = 0.048, RMSEA = 0.038). In relation to this, (Sideridis & Alghamdi, 2025) comment that it is common for the Chi-square test to be highly sensitive to the sample population (in this case, 350 adolescents) in large samples, which is why the model is often rejected, even though the indices show an adequate fit. In their research, the sample is large, so they consider it more appropriate to interpret the fit indices, as they provide more realistic and stable information about the model. Similarly, (Groskurth et al., 2023), indicates that goodness-of-fit indices behave differently under different situations, such as variety in the number of items, sample size, and others; but it particularly notes that when the sample is very large, the models may be rejected, but this does not determine that the indices do not have an appropriate fit. On the same line, (Goyal & Aleem, 2023), in their study, have a large sample, which makes it significant; however, the fit indices show a favorable fit (CFI close to .96-.97, TLI similar, low SRMR, and small RMSEA), so according to the indices, their model is acceptable.

Regarding the convergent validity of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts (IPPS-25), which was externally tested using the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI) for adolescents, a positive correlation was confirmed based on Spearman’s coefficient analysis of ρ = 0.535 (p < .001), and statistically significant between both measures. In turn, the association is considered moderate with 34.5% of the variance of the inventory (IPPS-25). In relation to the findings, a previous study conducted with adolescents in Spain corroborated the usefulness of the ASI test for measuring sexist behaviors and related it to romantic myths with double standards through the Romantic Love Myths Scale (EMA) test (p >.01). This result corroborates the methodological validity of the convergence between sexist attitudes and related constructs (Guerra-Marmolejo et al., 2021).

Furthermore, it is argued that the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI) can be applied to the adolescent population with a consistent and reliable structure, reinforcing the fact that it is possible to create similar constructs in young people (Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2023).

In relation to the fifth objective, we sought to establish evidence of reliability through internal consistency of the inventory using the Omega coefficient, which yielded an overall result of .749. This indicates that reliability is adequate and that the dimensions measure what is expected and are consistent. Likewise, the overall Alpha coefficient is .719, reaffirming that internal consistency is favorable. As reported (Colorado Romero et al., 2025), the interpretation of the results can be considered acceptable if the score is greater than .70 and less than .80. In contrast to the data found, in his similar research on sexism, he obtained an omega coefficient of .73, which is adequate, but it is estimated that his finding is slightly lower than that of the present research. Similarly, (Bonilla-Algovia et al., 2024), in contrast to the findings, the alpha coefficient is .92, which is very good for demonstrating reliability through internal consistency, slightly exceeding the IPPS-25.

The final objective sought to establish the norms and cut-off points for the scale. The average range lies between the 25th and 75th percentiles, indicating normative or typical scores for sexist thoughts, while scores above 75 show high levels of sexist thoughts and scores below 25 show low levels of sexist thoughts. Current literature suggests that percentile approaches are useful for establishing solid ranges within the usual standardization (Urban et al., 2025). In contrast to other studies, no rankings have been established to categorize levels of sexist thinking. However, it is estimated that a high level of sexism involves more frequent hostile behavior toward women through negative attitudes and rejection, while a low level encompasses egalitarian thinking between men and women, even though cultural stereotypes persist (Ayala et al., 2021).

Conclusions

The overall objective of this research study was to determine the construction and psychometric properties of the Inventory of Prevalence of Sexist Thoughts in adolescents in Trujillo, 2025. Therefore, we conclude that the scale is valid and reliable in this context and population group, as the results are considered adequate and acceptable values, emphasizing that the scale is consistent in measuring study variables. In addition, it was determined that the indices are favorable for achieving an adjustment of the instrument in the distribution of the different items (2 factors), and the scales could be divided into 3 cuts (low level, medium level, and high level).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Cortez Guadalupe, Daniela Alejandra; Luna Victoria Romero, Carlos Alexander; Niño Ciudad, Jhonny Moira; Silva Caldas, Geremias y Vigo Melendez, Yohana Elizabeth. Methodology: Cortez Guadalupe, Daniela Alejandra; Luna Victoria Romero, Carlos Alexander; Niño Ciudad, Jhonny Moira; Silva Caldas, Geremias y Vigo Melendez, Yohana Elizabeth. Formal analysis: Cortez Guadalupe, Daniela Alejandra; Luna Victoria Romero, Carlos Alexander; Niño Ciudad, Jhonny Moira; Silva Caldas, Geremias y Vigo Melendez, Yohana Elizabeth. Research: Cortez Guadalupe, Daniela Alejandra; Luna Victoria Romero, Carlos Alexander; Niño Ciudad, Jhonny Moira; Silva Caldas, Geremias y Vigo Melendez, Yohana Elizabeth. Data cleansing: Cortez Guadalupe, Daniela Alejandra. Drafting – original draft: Cortez Guadalupe, Daniela Alejandra; Luna Victoria Romero, Carlos Alexander; Niño Ciudad, Jhonny Moira; Silva Caldas, Geremias y Vigo Melendez, Yohana Elizabeth. Drafting – review and editing: Cortez Guadalupe, Daniela Alejandra; Luna Victoria Romero, Carlos Alexander; Niño Ciudad, Jhonny Moira; Silva Caldas, Geremias y Vigo Melendez, Yohana Elizabeth. Supervision: Paredes Jara, Fernando.

Funding

This research did not receive financial support from any entity.

Informed Consent Statement

All individuals involved in the research provided their informed consent before joining the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying the findings of this study may be requested from the lead author, provided that the request is justified.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all our collaborators for their dedication and support, whose contribution was crucial to the execution of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to the research presented.

References

- Alemany-Arrebola, I., González-Gijón, G., Ortiz-Gómez, M. D. M., & Ruiz-Garzón, F. (2024). Los estereotipos de género en adolescentes: Análisis en un contexto multicultural. Revista Colombiana de Educación, 90, 164-184. [CrossRef]

- Arias Gonzáles, J. L. (2021). Guía para elaborar la operacionalización de variables. Revista Espacio I+D Innovación más Desarrollo, X(28), 42-56. [CrossRef]

- Ávila Toscano, J. H., De La Rosa Ibáñez, G., Hernández Chang, E. A., Navarro Barreto, A., & Blanquicet Genes, R. (2024). Estereotipos de género como predictores de sexismo hostil y benevolente en hombres y mujeres heterosexuales. Psicología desde el Caribe, 40(1), 115-132. [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A., Vives--Cases, C., Davó--Blanes, C., Rodríguez--Blázquez, C., Forjaz, M. J., Bowes, N., DeClaire, K., Jaskulska, S., Pyżalski, J., Neves, S., Queirós, S., Gotca, I., Mocanu, V., Corradi, C., & Sanz--Barbero, B. (2021a). Sexism and its associated factors among adolescents in Europe: Lights4Violence baseline results. Aggressive Behavior, 47(3), 354-363. [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A., Vives--Cases, C., Davó--Blanes, C., Rodríguez--Blázquez, C., Forjaz, M. J., Bowes, N., DeClaire, K., Jaskulska, S., Pyżalski, J., Neves, S., Queirós, S., Gotca, I., Mocanu, V., Corradi, C., & Sanz--Barbero, B. (2021b). Sexism and its associated factors among adolescents in Europe: Lights4Violence baseline results. Aggressive Behavior, 47(3), 354-363. [CrossRef]

- Bareket, O., & Fiske, S. T. (2023). A systematic review of the ambivalent sexism literature: Hostile sexism protects men’s power; benevolent sexism guards traditional gender roles. Psychological Bulletin, 149(11-12), 637-698. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Algovia, E., Carrasco Carpio, C., & García-Pérez, R. (2024). Do Attitudes towards Gender Equality Influence the Internalization of Ambivalent Sexism in Adolescence? Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 805. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres Campoverde, J. A. (2025). El perfil psicológico y social del hombre sexista: Implicaciones para la violencia de pareja. [CrossRef]

- Calle Mollo, S. E. (2023). Diseños de investigación cualitativa y cuantitativa. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 7(4), 1865-1879. [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., Fernández-González, L., Orue, I., Machimbarrena, M., & González-Cabrera, J. (2021). Validación de un cuestionario para evaluar el abuso en relaciones de pareja en adolescentes (CARPA), sus razones y las reacciones. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 8(no 1), 60-69. [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Ayala, C. A., San Lucas Poveda, H. A., Ramirez Andrade, D. S., & Farfán-Córdova, N. S. (2024). Validation of a questionnaire on teacher attitudes towards values education in Piura. SCIÉNDO, 27(2), 173-180. [CrossRef]

- Checa-Romero, M., Rivas-Rivero, E., & Viuda-Serrano, A. (2021). Factors related to distorted thinking about women and violence in Secondary School students. Revista de Educación, 395, 363-389. [CrossRef]

- Chero-Pacheco, V. (2024). Población y muestra. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Dentistry, 17(2), 66-66. [CrossRef]

- Colorado Romero, J. R., Romero Montoya, M., Salazar Medina, M., Cabrera Zepeda, G., & Castillo Intriago, V. R. (2025). Análisis Comparativo de los Coeficientes Alfa de Cronbach, Omega de McDonald y Alfa Ordinal en la Validación de Cuestionarios. Estudios y Perspectivas Revista Científica y Académica, 4(4), 2738-2755. [CrossRef]

- Cortés Rodríguez, M. (2023). Biplot de datos composicionales, una nueva herramienta estadística para el estudio de test psicológicos: Aplicación al cuestionario de bienestar de Carol Ryff [Tesis de doctorado, Universidad de Salamanca]. https://gredos.usal.es/handle/10366/157702.

- Fernández García, O., Gil Lario, M. D., & Ballester Arnal, R. (2022). Prevalencia y Caracterización del Sexismo en el Contexto Español. Revista Contexto & Educação, 37(117), 118-127. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f31d/a00024d65e413b1fbaed9c0c49b03183ffde.pdf.

- Galván-Cabello, M. (2021). Inventario de Sexismo Ambivalente (ISA) en adolescentes chilenos: Estructura factorial, fiabilidad, validez e invarianza por sexo. Revista de Psicología Clínica Con Niños y Adolescentes, 8(3), 9-17. [CrossRef]

- García Viamontes, D., & Carbonell Vargas, M. S. (2023). Los estereotipos de género. Un estudio en adolescentes. Revista Estudios del Desarrollo Social: Cuba y América Latina, 11(1). http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S2308-01322023000100014&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en.

- García-González, J. R., & Sánchez-Sánchez, P. A. (2020). Diseño teórico de la investigación: Instrucciones metodológicas para el desarrollo de propuestas y proyectos de investigación científica. Información tecnológica, 31(6), 159-170. [CrossRef]

- García-Goñi, S., Loría-García, A., & Quesada-Leitón, H. (2023). Los Efectos del sexismo hacia las mujeres sobre la autoeficacia y desempeño en matemática de los hombres: Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales desde la teoría del sexismo ambivalente. Uniciencia, 37(1), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Glick, P. (2023). Social psychological research on gender, sexuality, and relationships: Reflections on contemporary scientific and cultural challenges. Frontiers in Social Psychology, 1. [CrossRef]

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491-512. [CrossRef]

- Glick, P., & Raberg, L. (2018). Benevolent sexism and the status of women. En APA handbook of the psychology of women: History, theory, and battlegrounds (Vol. 1). (pp. 363-380). American Psychological Association. https://content.apa.org/books/16034-018.

- González-Vega, A. M. D. C., Salazar, A. L., & Ramírez, J. M. (2023). LA ÉTICA EN LA INVESTIGACIÓN CUALITATIVA. UNA REFLEXIÓN DESDE LOS ESTUDIOS ORGANIZACIONALES. New Trends in Qualitative Research, 17, e808. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, H., & Aleem, S. (2023). Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Psychometric Validation of Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire (HLPCQ) in India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 48(3), 430-435. [CrossRef]

- Groskurth, K., Bluemke, M., & Lechner, C. M. (2023). Why we need to abandon fixed cutoffs for goodness-of-fit indices: An extensive simulation and possible solutions. Behavior Research Methods, 56(4), 3891-3914. [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Marmolejo, C., Fernández-Fernández, E., González-Cano-Caballero, M., García-Gámez, M., Del Río, F. J., & Fernández-Ordóñez, E. (2021). Factors Related to Gender Violence and Sex Education in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5836. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Prieto, B., Bringas Molleda, C., & Tornavacas Amado, R. (2022). Autopercepción de maltrato y actitudes ante la victimización en las relaciones interpersonales de pareja. Anuario de Psicología/The UB Journal of Psychology, 52(3). [CrossRef]

- Hernández González, O. (2021). Aproximación a los distintos tipos de muestreo no probabilístico que existen. 37(3). https://revmgi.sld.cu/index.php/mgi/article/view/1442.

- Hogg, M. A. (2021). Chapter Five—Self-uncertainty and group identification: Consequences for social identity, group behavior, intergroup relations, and society. En B. Gawronski (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 64, pp. 263-316). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Hooks, B. (2022). Enseñar pensamiento crítico. Rayo Verde Editorial.

- Huamán Rojas, J. A., Treviños Noa, L. L., & Medina Flores, W. A. (2022). Epistemología de las investigaciones cuantitativas y cualitativas. Horizonte de la Ciencia, 12(23). [CrossRef]

- Juarros-Basterretxea, J., Ocampo, N. Y., Rojas-Solis, J. L., Rodríguez-Díaz, F. J., & García-Cueto, E. (2023). Revisiting the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory’s Adolescent and Brief Versions: Problems, solutions, and considerations. Anales de Psicología, 39(2), 304-313. [CrossRef]

- Lescano López, G. S., & Ponce Yactayo, D. L. (2020). Adaptación, validez y confiabilidad de la escala de detección de sexismo (DSE) en estudiantes del nivel secundaria. Delectus, 3(2), 71-78. [CrossRef]

- Madrona-Bonastre, R., Sanz-Barbero, B., Pérez-Martínez, V., Abiétar, D. G., Sánchez-Martínez, F., Forcadell-Díez, L., Pérez, G., & Vives-Cases, C. (2023). Sexismo y violencia de pareja en adolescentes. Gaceta Sanitaria, 37, 102221. [CrossRef]

- Mancilla Barillas, M. R. (2024). Midiendo la realidad: El papel de las variables en la investigación científica. Revista Docencia Universitaria, 5(2), 51-68. [CrossRef]

- Manrique Tapia, C. R., & Flores Monzon, K. A. (2021). Sexismo y violencia en las relaciones de noviazgo en adolescentes de Lima. PSIQUEMAG/ Revista Científica Digital de Psicología, 10(1), 79-89. [CrossRef]

- Marín Hernández, R., Barajas Márquez, M. W., & Pineda Gómez, L. D. (2023). Relación de la insatisfacción corporal y la identificación grupal en hombres y mujeres universitarios durante el Covid19. Journal of Behavior, Health & Social Issues, 15(2), 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Martín Cabrera, E., Torbay Betancor, Á., & Alonso Sánchez, J. A. (2024). Mitos del amor romántico y sexismo ambivalente en adolescentes. Pedagogia Social Revista Interuniversitaria, 45, 137-148. [CrossRef]

- Martín, E., Torbay, Á., Alexis-Alonso, J., Gutiérrez, V., & Santos, I. (2025). Segregación por sexo en la adolescencia y su relación con el sexismo ambivalente. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 43. [CrossRef]

- Medina León, S. C., & Bravo Pisconti, C. A. (2021). Autoestima y sexismo ambivalente en adolescentes de una institución educativa del distrito de moche. WARMI, 1(1), 37-46. [CrossRef]

- Medina, M., Rojas, R., Bustamante, W., Loaiza, R., Martel, C., & Castillo, R. (2023). Metodología de la investigación: Técnicas e instrumentos de investigación (1.a ed.). Instituto Universitario de Innovación Ciencia y Tecnología Inudi Perú. [CrossRef]

- Navarro López, E., & Guerrero Martínez, M. A. (2023). La gestión de la amenaza a la identidad social en el hashtag de Twitter #CaravanaMigrante: Un estudio de caso sobre la narrativa en México. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 29(1), 177-193. [CrossRef]

- Navas, M. P., Gómez-Fraguela, J. A., & Sobral, J. (2022). Sexismo y tríada oscura de la personalidad en adolescentes: El rol mediador de la desconexión moral. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 54. [CrossRef]

- Ondé, D., & Alvarado, J. M. (2022). Contribución de los Modelos Factoriales Confirmatorios a la Evaluación de Estructura Interna desde la Perspectiva de la Validez. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación – e Avaliação Psicológica, 66(5), 5. [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. (2021). Estadísticas Sanitarias Mundiales 2020: Monitoreando la Salud para Los ODS, Objetivo de Desarrollo Sostenible (1st ed). World Health Organization.

- Ortega Sánchez, Delfín. (2023). ¿Cómo investigar en didáctica de las ciencias sociales? Fundamentos metodológicos, técnicas e instrumentos de investigación. Octaedro.

- Reyes-Solano, F. E., & Castaños-Cervantes, S. (2022). Sexismo Ambivalente como Correlato y Predictor de la Agresión Psicológica. Revista Lasallista de Investigación, 18(1), 280-293. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M. N., Martínez, E. R. P., Martínez, I. B. L., Cruz, D. H. M., Guerra, M. del R. A., Farías, J. O. I., Hachec, K. Y. B., López Olea, M., Iturribarri, S. L. C., Hurtado, J. S., Herrera, M. C., Luna, M. S. C., & Suazo, C. J. (2021). La evaluación de EO y EE en ELE : retos y propuestas. Centro de Enseñanza para Extranjeros. https://librosoa.unam.mx/handle/123456789/3286.

- Sideridis, G., & Alghamdi, M. (2025). Corrected goodness-of-fit index in latent variable modeling using non-parametric bootstrapping. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1562305. [CrossRef]

- Tenny, S., & Hoffman, M. R. (2025). Prevalence. En StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430867/.

- Unidad de Estadística Educativa. (2024). ¿QUÉ ES EL CENSO EDUCATIVO? [Ministerio Educación]. ESCALE. https://escale.minedu.gob.pe/censo-escolar-eol/.

- Urban, J., Scherrer, V., Strobel, A., & Preckel, F. (2025). Continuous Norming Approaches: A Systematic Review and Real Data Example. Assessment, 32(5), 654-674. [CrossRef]

- Vargas Vargas, S. P., & Vásquez Huamán, T. C. (2022). Propiedades Psicométricas del Cuestionario Copsoq-istas 21 en colaboradores que realizan home office en entidades privadas limeñas [Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas]. https://repositorioacademico.upc.edu.pe/handle/10757/661458.

- Veloza Gamba, R. (2023). Validez y fiabilidad del instrumento de análisis cuantitativo del uso de las redes sociales y el desarrollo de la inteligencia emocional en adolescentes. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 7(3), 4907-4933. [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, M. (2022). Understanding Intergroup Relations in Childhood and Adolescence. Review of General Psychology, 26(3), 282-297. [CrossRef]

- Vizcaíno Zúñiga, P. I., Cedeño Cedeño, R. J., & Maldonado Palacios, I. A. (2023). Metodología de la investigación científica: Guía práctica. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 7(4), 9723-9762. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).