Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

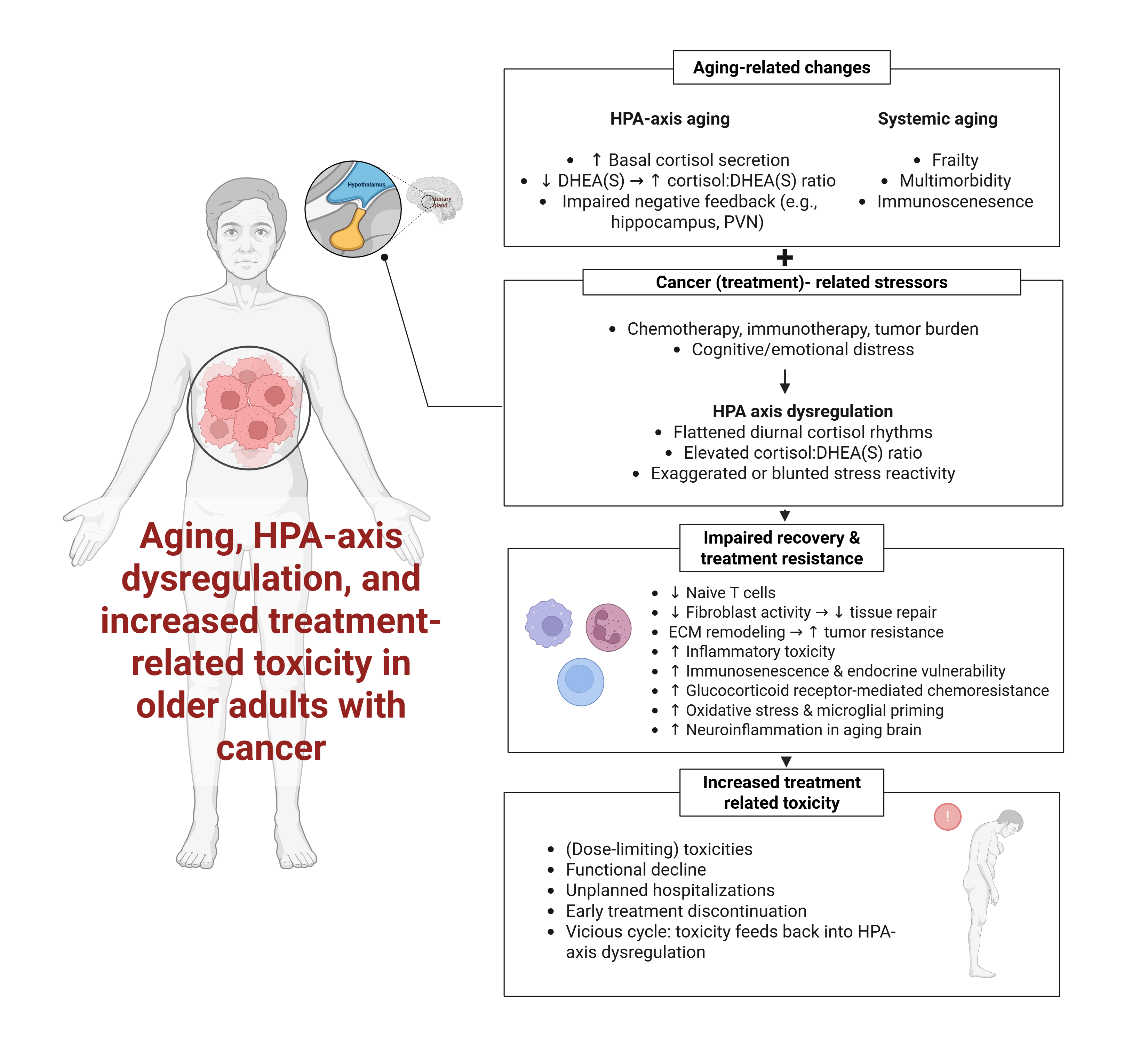

1. Introduction

2. HPA-Axis Dysregulation in Cancer Patients: Current Evidence

2.1. Prevalence and Patterns of HPA Axis Dysregulation

2.2. Associations with Clinical Outcomes

2.3. Mechanistic Pathways Relevant to Treatment Toxicity

2.3.1. Cortisol’s Role

2.3.2. DHEA(S)’s Role

2.4. Evidence Limitations and Unmet Needs

2.5. Section 2 Summary

- -

- HPA-axis dysregulation is prevalent across tumor types, most commonly manifesting as elevated cortisol levels and blunted circadian rhythms.

- -

- These abnormalities correlate with poorer survival and symptom burden but have not been validated as predictors of treatment toxicity.

- -

- Most evidence is prognostic and lacks specificity for treatment-related toxicities.

- -

- Prospective, age-stratified studies using standardized toxicity endpoints are urgently needed to determine the predictive and monitoring utility of cortisol and DHEA(S) in cancer care.

3. Treatment Outcomes in Older Adults

3.1. Age-Related Changes in Cortisol:DHEA Metabolism

3.2. Lack of Age-Stratified Analyses and Predictive Models

3.3. Mechanistic Pathways Linking Cortisol Dysregulation to Treatment Outcomes in Older Adults

3.4. Research Priorities

- (1)

- Conduct age-stratified analyses using reference-adjusted cortisol:DHEA(S) data. Future studies should explicitly stratify outcomes by age groups (e.g., 65–74, 75–84, ≥85 years) and apply age-appropriate reference ranges to distinguish normative aging effects from cancer-related dysregulation. Large-scale normative datasets already exist in endocrinology, but few oncology studies leverage this information to contextualize biomarker abnormalities in older patients.

- (2)

- Design longitudinal studies to track cortisol and DHEA(S) trajectories across treatment cycles. Rather than relying on single-time-point measures, research should evaluate temporal changes in cortisol slope, CAR, evening cortisol, and cortisol:DHEA(S) ratio at baseline, mid-treatment, and treatment completion. These trajectories may offer unique insights into dynamic resilience and physiological recovery. Real-time tracking may also support early toxicity detection and anticipatory supportive care.

- (3)

- Integrate endocrine biomarkers into multimodal prediction models. Validated risk scores such as CARG and CRASH could be enhanced by integrating endocrine markers. Alternatively, a new “Endocrine Resilience Index” incorporating salivary cortisol features, DHEA(S) levels, and clinical frailty indicators could be developed and validated in prospective cohorts.

- (4)

- Evaluate feasibility and implementation in vulnerable subgroups. Special attention should be given to frail, multimorbid, or cognitively impaired patients, who are often underrepresented in biomarker research. Studies should report not only biomarker-outcome associations but also feasibility metrics such as sample collection adherence, cost, acceptability, and usability in real-world geriatric oncology settings.

- (5)

- Explore DHEA(S)-specific effects and mechanisms. Compared to cortisol, DHEA(S) remains understudied in cancer populations. Its immuno-enhancing, anti-glucocorticoid, and anabolic properties may offer protective effects that deserve further exploration, especially in the context of sarcopenia, fatigue, and post-treatment recovery.

3.5. Section 3 Summary

- -

- Older adults exhibit distinct HPA-axis alterations that increase physiological vulnerability to cancer therapy.

- -

- Despite these biological vulnerabilities, most studies do not stratify biomarker data by age or integrate them into predictive models for toxicity.

- -

- Mechanistic pathways—including immune suppression, glucocorticoid receptor signaling, and impaired tissue repair—provide a biologically plausible rationale for the role of cortisol in mediating treatment intolerance.

- -

- Research priorities include age-adjusted reference use, longitudinal biomarker tracking, model integration, feasibility studies, and greater focus on DHEA(S).

- -

- These priorities lay the foundation for the standardization and clinical translation roadmap outlined in Section 5.

4. Methodological Heterogeneity: A Barrier to Clinical Translation

4.1. Sampling Matrices

4.2. Sample Timing Recommendations

4.3. Heterogeneity in Clinical Outcomes and Confounders

4.4. Lack of Reference Ranges for Older Adults

4.5. Section 4 Summary

- Biomarker research on cortisol and DHEA(S) is hindered by heterogeneity in matrix selection, sampling protocols, clinical outcome definitions, and covariate control.

- Salivary sampling is currently the most physiologically and logistically appropriate matrix for older cancer patients.

- Timing protocols should balance capturing diurnal variation with real-world feasibility in older adult populations.

- Standardized toxicity definitions, age-specific reference ranges, and rigorous confounder control are needed to enable biomarker qualification.

5. Future Research and Standardization Agenda

5.1. Standardization Priorities for Biomarker Development

- -

- Considering cortisol, at a minimum, collect five samples per day (awakening, +30 min, noon, afternoon, bedtime) over ≥3 consecutive days. In clinical contexts, simplified protocols (awakening + evening) may be acceptable if validated. Considering cortisol:DHEA(S), a morning two-day morning protocol could reduce random error relative to single-day sampling.

- -

- Time of awakening, medication use (especially corticosteroids), food intake, and sampling adherence must be systematically recorded and adjusted for.

- -

- Use validated immunoassays or LC-MS/MS with established inter-assay reliability.

- -

- Age- and treatment-stratified normative datasets must be established following existing guidance.

- -

- Adopt uniform clinical endpoints such as CTCAE grade ≥3 toxicities, dose reductions, treatment discontinuation, and unplanned hospitalizations.

5.2. Prospective Validation Studies

5.3. Interventional Research

5.4. Clinical Integration Framework

- -

- Pilot cortisol and DHEA(S) sampling as part of pre-treatment geriatric assessments.

- -

- Use alongside functional and inflammatory markers.

- -

- Evaluate logistical feasibility (e.g., sampling kits, lab capacity) and stakeholder acceptance.

- -

- Integrate validated HPA axis features (e.g., blunted slope, high cortisol:DHEA(S) ratio) into existing toxicity prediction tools (e.g., CARG, CRASH) or create new composite endocrineresilience scores.

- -

- Use automated interpretation platforms (e.g., electronic health record algorithms) to support clinical decision-making.

- -

- Conduct pragmatic trials or hybrid implementation-effectiveness studies [142] assessing if biomarker-informed care reduces severe toxicity rates, improves treatment adherence and dose intensity, and decreases hospitalization or functional decline.

5.5. Review Limitations

5.6. Section 5 Summary

- -

- Translation of HPA-axis biomarkers into geriatric oncology requires standardization, validation, interventional testing, and integration.

- -

- Prospective studies should assess predictive accuracy for treatment toxicity, including in frail and multimorbid patients.

- -

- Interventions targeting cortisol dysregulation—behavioral or pharmacological—should be tested for modifiability of toxicity risk.

- -

- Integration into oncology workflows demands demonstration of clinical utility and interdisciplinary collaboration.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgements

References

- NCI, N.C.I. Age and Cancer Risk. 2025 [cited 2025 July 23]; Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/age.

- Bhatt, V.R., Cancer in older adults: understanding cause and effects of chemotherapy-related toxicities. Future Oncol, 2019. 15(22): p. 2557-2560.

- Eochagain, C.M., et al., Management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated toxicities in older adults with cancer: recommendations from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG). Lancet Oncol, 2025. 26(2): p. e90-e102.

- Shahrokni, A., et al., Long-term Toxicity of Cancer Treatment in Older Patients. Clin Geriatr Med, 2016. 32(1): p. 63-80.

- Hurria, A., et al., Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol, 2011. 29(25): p. 3457-65.

- Extermann, M., et al., Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer, 2012. 118(13): p. 3377-86.

- Loh, K.P., et al., Adequate assessment yields appropriate care-the role of geriatric assessment and management in older adults with cancer: a position paper from the ESMO/SIOG Cancer in the Elderly Working Group. ESMO Open, 2024. 9(8): p. 103657.

- Hurria, A., et al., Validation of a Prediction Tool for Chemotherapy Toxicity in Older Adults With Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2016. 34(20): p. 2366-71.

- Chan, W.L., et al., Prediction models for severe treatment-related toxicities in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Age Ageing, 2025. 54(4).

- Chrousos, G.P., Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2009. 5(7): p. 374-81.

- Herman, J.P., et al., Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Compr Physiol, 2016. 6(2): p. 603-21.

- Alotiby, A., Immunology of Stress: A Review Article. J Clin Med, 2024. 13(21).

- Chrousos, G.P., The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and immune-mediated inflammation. N Engl J Med, 1995. 332(20): p. 1351-62.

- Gjerstad, J.K., S.L. Lightman, and F. Spiga, Role of glucocorticoid negative feedback in the regulation of HPA axis pulsatility. Stress, 2018. 21(5): p. 403-416.

- McEwen, B.S., Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. Eur J Pharmacol, 2008. 583(2-3): p. 174-85.

- McEwen, B.S., Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med, 1998. 338(3): p. 171-9.

- Kanter, N.G., et al., Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Dysfunction in People With Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancer Med, 2024. 13(22): p. e70366.

- Weinrib, A.Z., et al., Diurnal cortisol dysregulation, functional disability, and depression in women with ovarian cancer. Cancer, 2010. 116(18): p. 4410-9.

- Rasmuson, T., et al., Increased serum cortisol levels are associated with high tumour grade in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Acta Oncol, 2001. 40(1): p. 83-7.

- Ramirez-Exposito, M.J., et al., Circulating levels of beta-endorphin and cortisol in breast cancer. Compr Psychoneuroendocrinol, 2021. 5: p. 100028.

- Cruz, M.S.P., et al., Nighttime salivary cortisol as a biomarker of stress and an indicator of worsening quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep, 2022. 5(5): p. e783.

- Chang, W.P. and C.C. Lin, Relationships of salivary cortisol and melatonin rhythms to sleep quality, emotion, and fatigue levels in patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs, 2017. 29: p. 79-84.

- Bernabe, D.G., et al., Increased plasma and salivary cortisol levels in patients with oral cancer and their association with clinical stage. J Clin Pathol, 2012. 65(10): p. 934-9.

- Zeitzer, J.M., et al., Aberrant nocturnal cortisol and disease progression in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2016. 158(1): p. 43-50.

- Cash, E., et al., Evening cortisol levels are prognostic for progression-free survival in a prospective pilot study of head and neck cancer patients. Front Oncol, 2024. 14: p. 1436996.

- Volden, P.A. and S.D. Conzen, The influence of glucocorticoid signaling on tumor progression. Brain Behav Immun, 2013. 30 Suppl(0): p. S26-31.

- Ayroldi, E., et al., Role of Endogenous Glucocorticoids in Cancer in the Elderly. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(12).

- Spindler, M., et al., Dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis and its influence on aging: the role of the hypothalamus. Sci Rep, 2023. 13(1): p. 6866.

- Veldhuis, J.D., A. Sharma, and F. Roelfsema, Age-dependent and gender-dependent regulation of hypothalamic-adrenocorticotropic-adrenal axis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am, 2013. 42(2): p. 201-25.

- van den Beld, A.W., et al., The physiology of endocrine systems with ageing. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2018. 6(8): p. 647-658.

- Ferrari, E., et al., Age-related changes of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: pathophysiological correlates. Eur J Endocrinol, 2001. 144(4): p. 319-29.

- Buoso, E., et al., Opposing effects of cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone on the expression of the receptor for Activated C Kinase 1: implications in immunosenescence. Exp Gerontol, 2011. 46(11): p. 877-83.

- Pluchino, N., et al., Neurobiology of DHEA and effects on sexuality, mood and cognition. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2015. 145: p. 273-80.

- Butcher, S.K., et al., Raised cortisol:DHEAS ratios in the elderly after injury: potential impact upon neutrophil function and immunity. Aging Cell, 2005. 4(6): p. 319-24.

- Heaney, J.L., A.C. Phillips, and D. Carroll, Ageing, physical function, and the diurnal rhythms of cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2012. 37(3): p. 341-9.

- Schwartz, A.G., Dehydroepiandrosterone, Cancer, and Aging. Aging Dis, 2022. 13(2): p. 423-432.

- Bauer, M.E., Stress, glucocorticoids and ageing of the immune system. Stress, 2005. 8(1): p. 69-83.

- Chhabria, K., et al., Feasibility and value of salivary cortisol sampling to reflect distress in head and neck cancer patients undergoing chemoradiation: A proof-of-concept study. Int J Oncol Res, 2022. 5(2).

- Vizcaino, M., et al., Dysregulation in Cortisol Diurnal Activity among Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Cancer Patients. Open Access Text, 2018.

- Lutgendorf, S.K., et al., Interleukin-6, cortisol, and depressive symptoms in ovarian cancer patients. J Clin Oncol, 2008. 26(29): p. 4820-7.

- Abraham, S., et al., Accelerated Aging in Cancer and Cancer Treatment: Current Status of Biomarkers. Cancer Med, 2025. 14(9): p. e70929.

- Hubbard, J.M., H.J. Cohen, and H.B. Muss, Incorporating biomarkers into cancer and aging research. J Clin Oncol, 2014. 32(24): p. 2611-6.

- Sephton, S.E., et al., Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2000. 92(12): p. 994-1000.

- Reiche, E.M., S.O. Nunes, and H.K. Morimoto, Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol, 2004. 5(10): p. 617-25.

- Sephton, S. and D. Spiegel, Circadian disruption in cancer: a neuroendocrine-immune pathway from stress to disease? Brain Behav Immun, 2003. 17(5): p. 321-8.

- Colon-Echevarria, C.B., et al., Neuroendocrine Regulation of Tumor-Associated Immune Cells. Front Oncol, 2019. 9: p. 1077.

- Oh, I.J., et al., Altered Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Function: A Potential Underlying Biological Pathway for Multiple Concurrent Symptoms in Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer. Psychosom Med, 2019. 81(1): p. 41-50.

- Bower, J.E., Cancer-related fatigue: links with inflammation in cancer patients and survivors. Brain Behav Immun, 2007. 21(7): p. 863-71.

- Figueira, J.A., et al., Predisposing factors for increased cortisol levels in oral cancer patients. Compr Psychoneuroendocrinol, 2022. 9: p. 100110.

- Fang, Y.H., et al., Low Concentrations of Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate are Associated with Depression and Fatigue in Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer After Chemotherapy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2020. 16: p. 2103-2109.

- Taub, C.J., et al., Relationships Between Serum Cortisol, RAGE-Associated s100A8/A9 Levels, and Self-Reported Cancer-Related Distress in Women With Nonmetastatic Breast Cancer. Psychosom Med, 2022. 84(7): p. 803-807.

- Morrow, G.R., et al., Reduction in serum cortisol after platinum based chemotherapy for cancer: a role for the HPA axis in treatment-related nausea? Psychophysiology, 2002. 39(4): p. 491-5.

- Hursti, T.J., et al., Endogenous cortisol exerts antiemetic effect similar to that of exogenous corticosteroids. Br J Cancer, 1993. 68(1): p. 112-4.

- Toh, Y.L., et al., Prechemotherapy Levels of Plasma Dehydroepiandrosterone and Its Sulfated Form as Predictors of Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Breast Cancer Receiving Chemotherapy. Pharmacotherapy, 2019. 39(5): p. 553-563.

- Toh, Y.L. , et al., Longitudinal evaluation of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), its sulfated form and estradiol with cancer-related cognitive impairment in early-stage breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Sci Rep, 2022. 12(1): p. 16552.

- Lundstrom, S. and C.J. Furst, Symptoms in advanced cancer: relationship to endogenous cortisol levels. Palliat Med, 2003. 17(6): p. 503-8.

- Akiyama, Y. , et al., Peripherally administered cisplatin activates a parvocellular neuronal subtype expressing arginine vasopressin and enhanced green fluorescent protein in the paraventricular nucleus of a transgenic rat. J Physiol Sci, 2020. 70(1): p. 35.

- Melhem, A. , et al., Administration of glucocorticoids to ovarian cancer patients is associated with expression of the anti-apoptotic genes SGK1 and MKP1/DUSP1 in ovarian tissues. Clin Cancer Res, 2009. 15(9): p. 3196-204.

- Greenstein, A.E. and H.J. Hunt, Glucocorticoid receptor antagonism promotes apoptosis in solid tumor cells. Oncotarget, 2021. 12(13): p. 1243-1255.

- Olawaiye, A.B. , et al., Clinical Trial Protocol for ROSELLA: a phase 3 study of relacorilant in combination with nab-paclitaxel versus nab-paclitaxel monotherapy in advanced platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol, 2024. 35(4): p. e111.

- Demaria, M. , et al., Cellular Senescence Promotes Adverse Effects of Chemotherapy and Cancer Relapse. Cancer Discov, 2017. 7(2): p. 165-176.

- Hurria, A., L. Jones, and H.B. Muss, Cancer Treatment as an Accelerated Aging Process: Assessment, Biomarkers, and Interventions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 2016. 35: p. e516-22.

- Gomes, A. , AGE-INDUCED SYSTEMIC REPROGRAMMING DRIVES DRUG RESISTANCE IN LUNG CANCER. Innovation in Aging,, 2023. 7: p. Pages 139–140.

- Limberaki, E. , et al., Cortisol levels and serum antioxidant status following chemotherapy. Health Psychol, 2011. 3.

- Yu, S. , et al., Depression decreases immunity and PD-L1 inhibitor efficacy via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in triple-negative breast cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 2025. 1871(2): p. 167581.

- Patel, N. , et al., Immune checkpoint inhibitor induced hypophysitis: a specific disease of corticotrophs? Endocr Connect, 2024. 13(11).

- Di Stasi, V. , et al., Immunotherapy-Related Hypophysitis: A Narrative Review. Cancers (Basel), 2025. 17(3).

- von Bernhardi, R., L. Eugenin-von Bernhardi, and J. Eugenin, Microglial cell dysregulation in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Front Aging Neurosci, 2015. 7: p. 124.

- Sudheimer, K.D. , et al., Cortisol, cytokines, and hippocampal volume interactions in the elderly. Front Aging Neurosci, 2014. 6: p. 153.

- Suzuki, T. , et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone enhances IL2 production and cytotoxic effector function of human T cells. Clin Immunol Immunopathol, 1991. 61(2 Pt 1): p. 202-11.

- Martinez-Taboada, V. , et al., Changes in peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets in elderly subjects are associated with an impaired function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Mech Ageing Dev, 2002. 123(11): p. 1477-86.

- Araneo, B. and R. Daynes, Dehydroepiandrosterone functions as more than an antiglucocorticoid in preserving immunocompetence after thermal injury. Endocrinology, 1995. 136(2): p. 393-401.

- Blauer, K.L. , et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone antagonizes the suppressive effects of dexamethasone on lymphocyte proliferation. Endocrinology, 1991. 129(6): p. 3174-9.

- Perrini, S. , et al., Associated hormonal declines in aging: DHEAS. J Endocrinol Invest, 2005. 28(3 Suppl): p. 85-93.

- Erceg, N. , et al., The Role of Cortisol and Dehydroepiandrosterone in Obesity, Pain, and Aging. Diseases, 2025. 13(2).

- Dale, W. , et al., Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Systemic Cancer Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol, 2023. 41(26): p. 4293-4312.

- Battisti, N.M.L. and S.P. Arora, An overview of chemotherapy toxicity prediction tools in older adults with cancer: A young international society of geriatric oncology and nursing and allied health initiative. J Geriatr Oncol, 2022. 13(4): p. 521-525.

- Van Cauter, E., R. Leproult, and D.J. Kupfer, Effects of gender and age on the levels and circadian rhythmicity of plasma cortisol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1996. 81(7): p. 2468-73.

- Karlamangla, A.S. , et al., Daytime trajectories of cortisol: demographic and socioeconomic differences--findings from the National Study of Daily Experiences. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2013. 38(11): p. 2585-97.

- Stamou, M.I., C. Colling, and L.E. Dichtel, Adrenal aging and its effects on the stress response and immunosenescence. Maturitas, 2023. 168: p. 13-19.

- Ravaglia, G. , et al., The relationship of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) to endocrine-metabolic parameters and functional status in the oldest-old. Results from an Italian study on healthy free-living over-ninety-year-olds. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1996. 81(3): p. 1173-8.

- Phillips, A.C. , et al., Cortisol, DHEAS, their ratio and the metabolic syndrome: evidence from the Vietnam Experience Study. Eur J Endocrinol, 2010. 162(5): p. 919-23.

- Phillips, A.C. , et al., Cortisol, DHEA sulphate, their ratio, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the Vietnam Experience Study. Eur J Endocrinol, 2010. 163(2): p. 285-92.

- Tran Van Hoi, E. , et al., Toxicity in Older Patients with Cancer Receiving Immunotherapy: An Observational Study. Drugs Aging, 2024. 41(5): p. 431-441.

- Bouzan, J. and M. Horstmann, G8 screening and health-care use in patients with cancer. Lancet Healthy Longev, 2023. 4(7): p. e297-e298.

- Frelaut, M. , et al., External Validity of Two Scores for Predicting the Risk of Chemotherapy Toxicity Among Older Patients With Solid Tumors: Results From the ELCAPA Prospective Cohort. Oncologist, 2023. 28(6): p. e341-e349.

- Al-Danakh, A. , et al., Aging-related biomarker discovery in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer patients. Front Immunol, 2024. 15: p. 1348189.

- Morse, R.T. , et al., Sarcopenia and Treatment Toxicity in Older Adults Undergoing Chemoradiation for Head and Neck Cancer: Identifying Factors to Predict Frailty. Cancers (Basel), 2022. 14(9).

- Menjak, I.B. , et al., Predicting treatment toxicity in older adults with cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care, 2021. 15(1): p. 3-10.

- Li, D., E. Soto-Perez-de-Celis, and A. Hurria, Geriatric Assessment and Tools for Predicting Treatment Toxicity in Older Adults With Cancer. Cancer J, 2017. 23(4): p. 206-210.

- Salminen, A. , Immunosuppressive network promotes immunosenescence associated with aging and chronic inflammatory conditions. J Mol Med (Berl), 2021. 99(11): p. 1553-1569.

- Yu, W. , et al., Immune Alterations with Aging: Mechanisms and Intervention Strategies. Nutrients, 2024. 16(22).

- Chen, M., Z. Su, and J. Xue, Targeting T-cell Aging to Remodel the Aging Immune System and Revitalize Geriatric Immunotherapy. Aging Dis, 2025.

- Adelaiye-Ogala, R. , et al., Targeting the PI3K/AKT Pathway Overcomes Enzalutamide Resistance by Inhibiting Induction of the Glucocorticoid Receptor. Mol Cancer Ther, 2020. 19(7): p. 1436-1447.

- Kaboli, P.J. , et al., Chemoresistance in breast cancer: PI3K/Akt pathway inhibitors vs the current chemotherapy. Am J Cancer Res, 2021. 11(10): p. 5155-5183.

- Aggarwal, B.B. and B. Sung, NF-kappaB in cancer: a matter of life and death. Cancer Discov, 2011. 1(6): p. 469-71.

- Karin, M. , NF-kappaB as a critical link between inflammation and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2009. 1(5): p. a000141.

- Beesley, A.H. , et al., Glucocorticoid resistance in T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia is associated with a proliferative metabolism. Br J Cancer, 2009. 100(12): p. 1926-36.

- Niculet, E., C. Bobeica, and A.L. Tatu, Glucocorticoid-Induced Skin Atrophy: The Old and the New. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol, 2020. 13: p. 1041-1050.

- Chae, M. , et al., AP Collagen Peptides Prevent Cortisol-Induced Decrease of Collagen Type I in Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(9).

- Varani, J. , et al., Decreased collagen production in chronologically aged skin: roles of age-dependent alteration in fibroblast function and defective mechanical stimulation. Am J Pathol, 2006. 168(6): p. 1861-8.

- Quan, T. and G.J. Fisher, Role of Age-Associated Alterations of the Dermal Extracellular Matrix Microenvironment in Human Skin Aging: A Mini-Review. Gerontology, 2015. 61(5): p. 427-34.

- Fiacco, S., A. Walther, and U. Ehlert, Steroid secretion in healthy aging. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2019. 105: p. 64-78.

- Maninger, N. , et al., Neurobiological and neuropsychiatric effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate (DHEAS). Front Neuroendocrinol, 2009. 30(1): p. 65-91.

- Hulett, J.M. , et al., Rigor and Reproducibility: A Systematic Review of Salivary Cortisol Sampling and Reporting Parameters Used in Cancer Survivorship Research. Biol Res Nurs, 2019. 21(3): p. 318-334.

- Subnis, U.B. , et al., Psychosocial therapies for patients with cancer: a current review of interventions using psychoneuroimmunology-based outcome measures. Integr Cancer Ther, 2014. 13(2): p. 85-104.

- Vining, R.F. , et al., Salivary cortisol: a better measure of adrenal cortical function than serum cortisol. Ann Clin Biochem, 1983. 20 (Pt 6): p. 329-35.

- Gozansky, W.S. , et al., Salivary cortisol determined by enzyme immunoassay is preferable to serum total cortisol for assessment of dynamic hypothalamic--pituitary--adrenal axis activity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2005. 63(3): p. 336-41.

- Aardal-Eriksson, E., T. E. Eriksson, and L.H. Thorell, Salivary cortisol, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and general health in the acute phase and during 9-month follow-up. Biol Psychiatry, 2001. 50(12): p. 986-93.

- Hulett, J.M. , et al., Religiousness, Spirituality, and Salivary Cortisol in Breast Cancer Survivorship: A Pilot Study. Cancer Nurs, 2018. 41(2): p. 166-175.

- Ahn, R.S. , et al., Salivary cortisol and DHEA levels in the Korean population: age-related differences, diurnal rhythm, and correlations with serum levels. Yonsei Med J, 2007. 48(3): p. 379-88.

- Izawa, S. , et al., Salivary dehydroepiandrosterone secretion in response to acute psychosocial stress and its correlations with biological and psychological changes. Biol Psychol, 2008. 79(3): p. 294-8.

- Hucklebridge, F. , et al., The diurnal patterns of the adrenal steroids cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in relation to awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2005. 30(1): p. 51-7.

- Straub, R.H. , et al., Serum dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate are negatively correlated with serum interleukin-6 (IL-6), and DHEA inhibits IL-6 secretion from mononuclear cells in man in vitro: possible link between endocrinosenescence and immunosenescence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1998. 83(6): p. 2012-7.

- Prom-Wormley, E.C. , et al., Genetic and environmental effects on diurnal dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate concentrations in middle-aged men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2011. 36(10): p. 1441-52.

- Kudielka, B.M. and C. Kirschbaum, Awakening cortisol responses are influenced by health status and awakening time but not by menstrual cycle phase. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2003. 28(1): p. 35-47.

- Ryan, R. , et al., Use of Salivary Diurnal Cortisol as an Outcome Measure in Randomised Controlled Trials: a Systematic Review. Ann Behav Med, 2016. 50(2): p. 210-36.

- Zhao, Z.Y. , et al., Circadian rhythm characteristics of serum cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in healthy Chinese men aged 30 to 60 years. A cross-sectional study. Steroids, 2003. 68(2): p. 133-8.

- Laudenslager, M.L. , et al., Diurnal patterns of salivary cortisol and DHEA using a novel collection device: electronic monitoring confirms accurate recording of collection time using this device. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2013. 38(9): p. 1596-606.

- Hellhammer, J. , et al., Several daily measurements are necessary to reliably assess the cortisol rise after awakening: state- and trait components. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2007. 32(1): p. 80-6.

- Adam, E.K. and M. Kumari, Assessing salivary cortisol in large-scale, epidemiological research. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2009. 34(10): p. 1423-36.

- Fenech, A.L. , et al., Fear of cancer recurrence and change in hair cortisol concentrations in partners of breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv, 2024.

- Lambert, M. , et al., Behavioural, physical, and psychological predictors of cortisol and C-reactive protein in breast cancer survivors: A longitudinal study. Brain Behav Immun Health, 2021. 10: p. 100180.

- Andreano, J.M. , et al., Effects of breast cancer treatment on the hormonal and cognitive consequences of acute stress. Psychooncology, 2012. 21(10): p. 1091-8.

- Arlt, W. , et al., Frequent and frequently overlooked: treatment-induced endocrine dysfunction in adult long-term survivors of primary brain tumors. Neurology, 1997. 49(2): p. 498-506.

- van Waas, M. , et al., Adrenal function in adult long-term survivors of nephroblastoma and neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer, 2012. 48(8): p. 1159-66.

- Kunz, S. , et al., Age- and sex-adjusted reference intervals for steroid hormones measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using a widely available kit. Endocr Connect, 2024. 13(1).

- Frederiksen, H. , et al., Sex- and age-specific reference intervals of 16 steroid metabolites quantified simultaneously by LC-MS/MS in sera from 2458 healthy subjects aged 0 to 77 years. Clin Chim Acta, 2024. 562: p. 119852.

- Gregory, S. , et al., Using LC-MS/MS to Determine Salivary Steroid Reference Intervals in a European Older Adult Population. Metabolites, 2023. 13(2).

- Supe-Domic, D. , et al., Reference intervals for six salivary cortisol measures based on the Croatian Late Adolescence Stress Study (CLASS). Biochem Med (Zagreb), 2018. 28(1): p. 010902.

- Meszaros Crow, E. , et al., Psychosocial interventions reduce cortisol in breast cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol, 2023. 14: p. 1148805.

- Monaghan, P.J. , et al., Practical guide for identifying unmet clinical needs for biomarkers. EJIFCC, 2018. 29(2): p. 129-137.

- De Nys, L. , et al., The effects of physical activity on cortisol and sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2022. 143: p. 105843.

- Nys, L.D. , et al., Physical Activity Influences Cortisol and Dehydroepiandrosterone (Sulfate) Levels in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 2022-08-17. 31(2).

- Black, D.S. , et al., Mindfulness practice reduces cortisol blunting during chemotherapy: A randomized controlled study of colorectal cancer patients. Cancer, 2017. 123(16): p. 3088-3096.

- Phillips, K.M. , et al., Stress management intervention reduces serum cortisol and increases relaxation during treatment for nonmetastatic breast cancer. Psychosom Med, 2008. 70(9): p. 1044-9.

- Lengacher, C.A. , et al., A Large Randomized Trial: Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) for Breast Cancer (BC) Survivors on Salivary Cortisol and IL-6. Biol Res Nurs, 2019. 21(1): p. 39-49.

- Matiz, A. , et al., The effect of mindfulness-based interventions on biomarkers in cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review. Stress Health, 2024. 40(4): p. e3375.

- Giudice, E. , et al., Relacorilant in recurrent ovarian cancer: clinical evidence and future perspectives. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther, 2024. 24(8): p. 649-655.

- Nanda, R. , et al., A randomized phase I trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel with or without mifepristone for advanced breast cancer. Springerplus, 2016. 5(1): p. 947.

- Brandhagen, B.N. , et al., Cytostasis and morphological changes induced by mifepristone in human metastatic cancer cells involve cytoskeletal filamentous actin reorganization and impairment of cell adhesion dynamics. BMC Cancer, 2013. 13: p. 35.

- Landes, S.J., S. A. McBain, and G.M. Curran, An introduction to effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Psychiatry Res, 2019. 280: p. 112513.

| Study | Study design | Cancer & treatment context | Biomarkers & matrix | Sampling window | Toxicities / AE endpoint | Main toxicity(-related) finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oh et al., 2019 [47] | Cross-sectional observational | Advanced lung cancer (mixed age; mean 64.3 ± 9.2 → includes ≥65 subset) | Salivary cortisol | Upon awakening (0, +30, +60 min) and nighttime (~21:00–22:00) | Symptom burden (MDASI), performance status (toxicity-related) | Blunted CAR and flatter diurnal slope associated with worse performance status and higher burden of multiple concurrent symptoms (incl. nausea cluster), indicating HPA dysregulation tracks toxicity-related symptomatology. |

| Fang et al., 2020 [50] | Case–control (post-chemotherapy patients vs age-matched controls) | NSCLC after chemotherapy (population typically older; paper notes lung cancer median diagnosis age ≈70) | Salivary DHEA, DHEA-S, and cortisol | Daytime saliva (single-timepoint per protocol) | Fatigue & depression scores after chemotherapy (toxicity-related) | Patients had reduced salivary DHEA-S vs controls; lower DHEA-S associated with higher fatigue and depression after chemo—supporting relevance of the cortisol/DHEA(S) axis to post-treatment symptom toxicity. |

| Cruz et al., 2022 [21] | Cross-sectional | Head & neck cancer (HNC; adult cohort with older subset) | Nighttime salivary cortisol | Nighttime (single sample per protocol) | Quality of life (UW-QOL) and perceived stress (toxicity-related) | Higher nighttime cortisol associated with worse quality of life and higher perceived stress, consistent with cortisol dysregulation mapping onto toxicity-related well-being impairments in HNC. |

| Morrow et al., 2002 [52] | Repeated-measures within-subject | Ovarian cancer receiving cisplatin/carboplatin (disease predominantly in older women; median diagnosis age ≈63) | Serum cortisol (total) | Serial samples pre-infusion and hourly for 6 h across two chemotherapy cycles | Acute CINV (nausea/vomiting; treatment toxicity) | Serum cortisol fell immediately after platinum infusion (vs control day), supporting a direct chemo–HPA interaction potentially relevant to CINV pathophysiology. |

| Hursti et al., 1993 [53] | Observational | Cisplatin-treated ovarian cancer (adults incl. 65 years or older) | Nocturnal urinary cortisol | Night prior to chemotherapy | CINV (vomiting ± nausea) | Lower pre-chemo nighttime cortisol predicted more severe cisplatin-induced nausea/vomiting in 42 patients |

| Fang et al., 2020 [50] | Cross-sectional case-control | Advanced NSCLC after chemotherapy (adults incl. older) | Salivary DHEA & DHEAS & cortisol | Single post-chemo sampling | Fatigue and depression scores | Lower DHEAS associated with higher fatigue and depression after chemotherapy vs. controls; patients had reduced DHEA/DHEAS post-chemo. |

| Toh et al., 2019 [54] | Prospective cohort | Early breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy (mixed ages; includes older subset though mean ~49) | Plasma DHEAS & DHEA (UHPLC-MS/MS) | Pre-chemotherapy baseline | CRCI (FACT-Cog domains) during & after therapy | Higher pre-chemo DHEAS predicted lower odds of CRCI (verbal fluency, mental acuity) over treatment; DHEA not predictive. |

| Toh et al., 2022 [55] | Longitudinal cohort | Early breast cancer on anthracycline-based chemo (adults incl. older subset) | DHEA, DHEAS, estradiol (plasma) | Pre-, during, and post-chemo | CRCI trajectories | Within-patient DHEA(S) variations tracked with cognitive symptom trajectories across treatment. |

| Lundström et al., 2003 [56] | Cross-sectional | Advanced cancer, predominantly gastrointestinal canccer (mixed sites; adults incl. older) | Urinary free cortisol | Single timepoint | Symptom scores (fatigue, appetite loss, nausea/vomiting) | Higher endogenous cortisol correlated positively with fatigue, appetite loss, nausea/vomiting—toxicity-related symptom burden in advanced disease. |

| Cash et al., 2024 [25] | Prospective | Head and neck cancer - most patients >50 years (some 65+), late-stage oral/oropharyngeal cancer | Cortisol (salivary) - diurnal slope, mean, waking, evening levels | Twice daily for 6 consecutive days during diagnostic/treatment planning | Progression-free survival (treatment outcomes, not toxicity) | Elevated evening cortisol and diurnal mean cortisol associated with shorter progression-free survival |

| Phase | Objective | Key Actions | Expected Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Methodological standardization | Establish uniform, reproducible biomarker protocols | - Select salivary or serum cortisol and DHEA(S) as preferred matrices, depending on analytic tools and study objectives - Define minimum sampling protocol - Standardize pre-analytical variables (e.g., awakening time, corticosteroid use) - Employ validated assays (e.g., LC-MS/MS or calibrated immunoassays) - Stratify data by age, sex, cancer type, and treatment phase |

- Harmonized biomarker assessment protocol - Age- and treatment-specific reference ranges - Enhanced cross-study comparability |

| 2. Prospective Validation | Demonstrate predictive validity for treatment-related toxicity in older adults | - Recruit ≥65-year-old treatment-naïve patients - Collect cortisol and DHEA(S) ratio (baseline, mid-, post-treatment) - Assess toxicity endpoints: DLTs, dose reductions, hospitalizations, functional decline - Adjust for frailty, comorbidities, polypharmacy - Track adherence and patient burden |

- Predictive models incorporating cortisol:DHEA(S) ratio - Risk thresholds for toxicity stratification - Real-world feasibility and compliance data |

| 3. Interventional Trials | Test whether modifying HPA-axis dysregulation improves outcomes | - Identify patients with abnormal HPA profiles - Randomize to behavioural interventions (e.g., CBT, yoga, exercise) or pharmacologic agents - Embed serial biomarker sampling and toxicity tracking - Evaluate toxicity, functional, and QoL outcomes |

- Evidence for causal role of cortisol:DHEA(S) ratio - Demonstration of biomarker-guided toxicity reduction - Interventional proof-of-concept |

| 4. Clinical Integration | Embed biomarkers into oncology care pathways | - Pilot salivary sampling in pre-treatment geriatric assessments - Integrate cortisol/DHEA(S) features into existing tools (e.g., CARG, CRASH) or new endocrine-resilience indices - Develop EHR-integrated decision-support tools - Conduct implementation-effectiveness studies |

- Clinical workflows incorporating HPA-axis assessment - Improved patient stratification and individualized supportive care - Reduced toxicity and treatment discontinuation rates |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).