Introduction

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is a rare, severe, and progressive X-linked neuromuscular disorder that primarily affects boys, leading to muscle degeneration, loss of ambulation, and premature death due to cardiac or respiratory complications [

1,

2,

3]. With an estimated global prevalence of 19.8 per 100,000 live male births, DMD is the most common and debilitating dystrophinopathy [

4]. Despite advances in multidisciplinary care—including corticosteroids, physiotherapy, and novel molecular therapies [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]—life expectancy has only modestly improved [

15,

16,

17], while families continue to face profound challenges beyond the clinical course of the disease.

The need to assess health related quality of life (HRQoL) and the financial burden in rare diseases such as DMD has gained prominence in global health policy discourse. Organizations like the World Health Organization [

18] and the European Commission [

19] advocate for more comprehensive, patient-centered outcome measures that extend beyond clinical indicators. In parallel, health technology assessment (HTA) frameworks increasingly recognize the value of real-world data in rare disease settings, where randomized controlled trials are often logistically or ethically challenging [

20,

21,

22,

23]. These shifts reflect a growing consensus that equitable policy and resource allocation must be informed by both clinical and lived experiences.

Recent research has drawn increasing attention to the socioeconomic and health related quality of life impact of DMD [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Studies have documented the high direct and indirect costs of DMD care, such as in Egypt, where annual per-patient costs were estimated at USD 17.485, with substantial financial strain on households [

29]. However, such studies often rely on non-validated instruments, limiting comparability across settings. Furthermore, previous cost-of-illness studies in Southern Europe, including Spain [

30], Portugal [

31], and Italy [

32] have provided important estimates of the financial burden of DMD. However, these studies were conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, relied mainly on generic or ad-hoc instruments, and focused primarily on cost quantification or guideline adherence without systematically linking patient HRQoL with caregiver socioeconomic data. Beyond Southern Europe, recent studies from Denmark [

33], and Japan [

34], have also examined the cost of illness in DMD. While these provide valuable estimates of healthcare and societal costs, they relied primarily on register-based or economic approaches and did not incorporate validated disease-specific HRQoL instruments or systematically assess financial protection mechanisms.

Caregiver-focused research, such as Schwartz et al. 2020 [

35], has demonstrated the toll of DMD progression on family well-being, including sleep, mental health, and work productivity, yet these analyses were largely cross-sectional and based on generic tools, potentially overlooking disease-specific burdens. In India, Sirari et al. [

36], found that children’s HRQoL declined with age and disease severity, but no significant link to socioeconomic status was observed—contrasting with patterns reported in European contexts. Finally, a systematic review [

37], has highlighted inconsistencies in HRQoL findings, attributed to differences in measurement approaches, and emphasized the need for condition-specific tools and broader, multidimensional perspectives on family impact.

Collectively, these studies underscore several unresolved issues, such as limited use of validated, disease-specific HRQoL instruments across cultural and socioeconomic contexts; insufficient integration of financial burden, caregiver roles, and HRQoL into a single analytic framework; and a lack of data from Southern European countries, particularly in the post-pandemic era, where disruptions in health services and economic stressors may exacerbate existing vulnerabilities.

Our study addresses these gaps by providing the first assessment in Greece of the intersection between HRQoL, socioeconomic burden, and caregiving in families of children with DMD. Furthermore, our study aims to generate comprehensive evidence on the challenges faced by families of children with DMD in Greece during the post-pandemic period. Importantly, it employs the validated Greek version of the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module alongside the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales, ensuring cultural and linguistic appropriateness [

38,

39]. Furthermore, by incorporating detailed data on household income, maternal employment, state allowances, and out-of-pocket expenditures, this study uniquely captures the interplay between clinical severity, financial stress, and HRQoL outcomes in a real-world, resource-constrained healthcare system. Specifically, the objectives are to:

- (a)

quantify the regular and unexpected out-of-pocket expenditures;

- (b)

explore the impact of caregiving demands on maternal employment and household resilience;

- (c)

assess the HRQoL in children with DMD using validated tools; and

- (d)

evaluate how clinical and socioeconomic variables (e.g., allowance status, mobility, regional disparities) shape HRQoL outcomes.

By addressing these objectives, the study not only contributes new evidence from Greece but also provides insights with international relevance, informing policy and health system reforms in other countries where rare disease care is challenged by limited resources and fragmented support structures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

This multicenter, cross-sectional study was conducted between September 2022 and July 2023 among pediatric patients with DMD and their families in Greece. Participants were recruited from neuromuscular clinics and patient registries nationwide, with representation from 15 of the 51 regional prefectures. A total of two neuromuscular clinics were approached across Greece. Of the 125 eligible patients aged 5-18 years old identified through clinic registries and referrals, 75 were contacted, and 50 consented to participate, yielding a response rate of 67%. Reasons for non-participation included e.g., lack of interest, inability to travel, incomplete records. The study combined in-person interviews at AHEPA University Hospital (Thessaloniki) and the University General Hospital of Patras with remote interviews (via phone or videoconferencing), following ethical approvals from the respective institutions and the University of the Peloponnese.

Eligible participants were boys aged 5–18 years with a genetically confirmed diagnosis of DMD. The following independent variables were collected and analyzed: (i) demographic (child age, parental education, region of residence); (ii) clinical (age at diagnosis, ambulatory status, wheelchair dependency, corticosteroid use); (iii) socioeconomic (household income, state allowance status, insurance coverage, out-of-pocket costs — monthly and unexpected); (iv) caregiver-related (maternal employment, caregiving hours). In particular, as allowance was stated the receipt of state support (extrainstitutional allowance, social allowance, no allowance), as unexpected annual expenses were self-reported lump-sum health-related costs in the past 12 months, as monthly expenses were recurring out-of-pocket costs x 12, insurance was the coverage through public/private insurance or no insurance, the wheelchair use was dichotomous, abased on mobility status at interview and corticosteroid treatment referred to current status of costicosteroic use.

HRQoL was assessed using the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales and the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module. Children aged 8–18 completed self-report forms where possible, while parents or primary caregivers completed proxy versions for all children. Children aged 5–7 did not complete self-reports. When required, trained researchers assisted in reading items aloud and recording responses.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Peloponnese (prot.no. 11415/31-5-2023), AHEPA Hospital (prot.no. 239/16-5-2022), and Patras University Hospital (prot.no. 246/31-5-2022). Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians of all participants, and assent was obtained from children ≥8 years where appropriate.

2.2. Measures

HRQoL was assessed using two validated instruments: the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ (PedsQL™) 4.0 Generic Core Scales and the disease-specific PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module. We used the validated Greek version of the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales, previously adapted and tested for reliability and validity in Greek children [

38]. For the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module, we employed the Greek version recently adapted and validated in a separate study [

39], which confirmed linguistic equivalence, cultural appropriateness, and strong psychometric properties (Cronbach’s α = 0.80 for child self-report, α = 0.89 for parent proxy-report) . In the present sample, internal consistency reliability was also assessed. Cronbach’s α coefficients exceeded 0.70 across all subscales of the PedsQL™ 4.0 GC and 0.80 for the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module, supporting their use in this population.

The PedsQL™ 4.0 GC is designed to differentiate between children with chronic health conditions and their healthy peers, offering a general assessment of HRQoL across physical, emotional, social, and school functioning domains. In contrast, the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module allows for more disease-specific evaluation, facilitating comparisons in HRQoL among subgroups of DMD patients based on age, disease stage, and even cultural or ethnic background. The PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales comprise 23 items across four domains: Physical Functioning (8 items), Emotional Functioning (5 items), Social Functioning (5 items), and School Functioning (5 items). A Psychosocial Health Summary Score is computed as the mean of the Emotional, Social, and School subscales. The instrument includes age-appropriate self-report (ages 5–18) and proxy-report formats (ages 2–18), with higher scores indicating better HRQoL. The PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module assesses disease-specific HRQoL and includes 18 items grouped into four domains: Daily Activities (5 items), Treatment Barriers (4 items), Worry (6 items), and Communication (3 items). It is available in child self-report formats for ages 8–12 and 13–18 years and proxy versions for ages 5–7, 8–12, and 13–18 years. All items across both instruments are scored using a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never a problem to 4 = almost always a problem), reverse-scored, and transformed to a 0–100 scale, with higher scores reflecting better perceived quality of life. The instruments were administered based on the child’s age and cognitive capacity. Together, they offer a comprehensive assessment of general and condition-specific quality of life (HRQoL).

The socioeconomic questionnaire was developed based on European and international health economics frameworks for out-of-pocket health expenditures [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. The socioeconomic questionnaire included questions about household income, receipt of a state allowance, unexpected or on a regular basis out-of-pocket costs concerning medical or non-medical expenses related to the child’s condition, impact on parents’ employment, public of private insurance and benefits covered by insurance. Internal consistency was not computed given the multidimensional (non-scale) nature of the questionnaire.

Household income (€) was grouped in four categories with lower and upper limits. Regular out-of-pocket costs (€) were calculated as monthly reports × 12, unexpected costs were recorded as lump sums in the past 12 months. Financial burden was expressed both in absolute values (€) and relative to household income (%). Employment impact was coded as full-time, part-time, unemployed due to caregiving, or unemployed unrelated to caregiving. The status of insurance was indicated as public, private or no insurance and regarding the benefits covered by insurance the participants indicated whether they received it or not.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0. Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were applied to examine associations on patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and socioeconomic variables, presented as means, medians, standard deviations, ranges, and percentages where appropriate. Given the sample size (n = 50), analyses were restricted to descriptive statistics, bivariate comparisons, and correlation tests. Multivariable regression modeling was considered but not performed to avoid overfitting due to the limited number of observations relative to potential predictors. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were calculated for all continuous variables. Effect sizes were computed to aid interpretation of group differences. To evaluate agreement between child self-reports and parent proxy-reports on HRQoL outcomes, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated. Associations between PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales and PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module domains were examined using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients due to the non-normal distribution of the data. Non-parametric tests were employed to identify factors associated with HRQoL outcomes and financial burden. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparisons between two independent groups, while the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for comparisons across three or more groups. The significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 50 children with DMD, aged 5 to 18 years, were enrolled in the study. In terms of mode of inheritance, 68% (

n = 34) had maternal transmission of the disease. The mean age at the time of data collection was 12.52 years (SD =2.97), while the mean age at diagnosis was 3.58 years (SD = 2.53). Participants were grouped according to the PedsQL™ age brackets: 5–7 years: n=9 children, 8–12 years:

n= 24 children, 13–18 years:

n =17 children. Regarding clinical characteristics: 30% of the children (

n = 15) were non-ambulatory, 46% (

n = 23) were currently receiving corticosteroid therapy and 54% (

n = 27) were undergoing physiotherapy. A detailed summary of demographic and clinical characteristics is presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Household Financial Burden in Relation to Income and Allowance Status

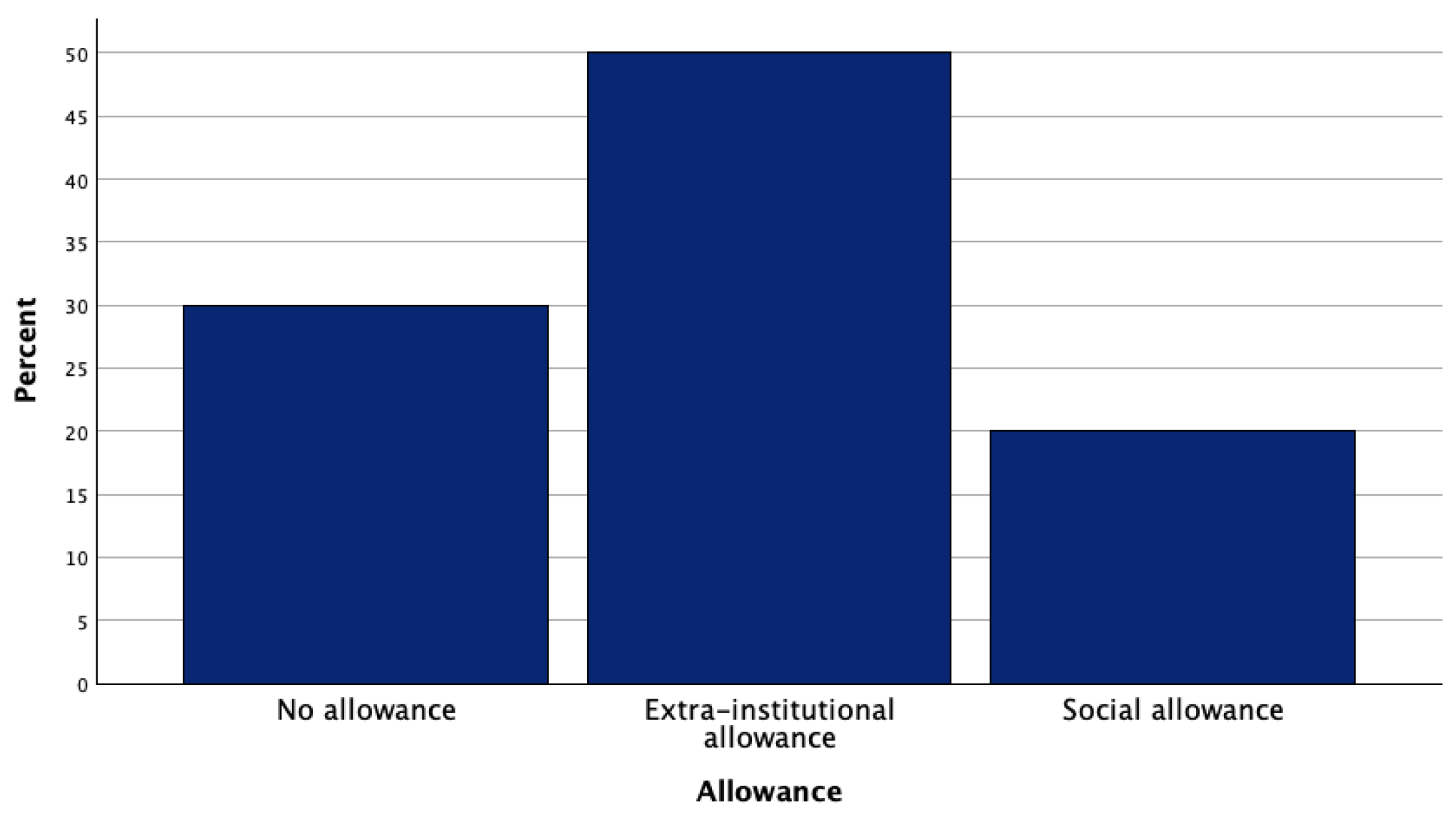

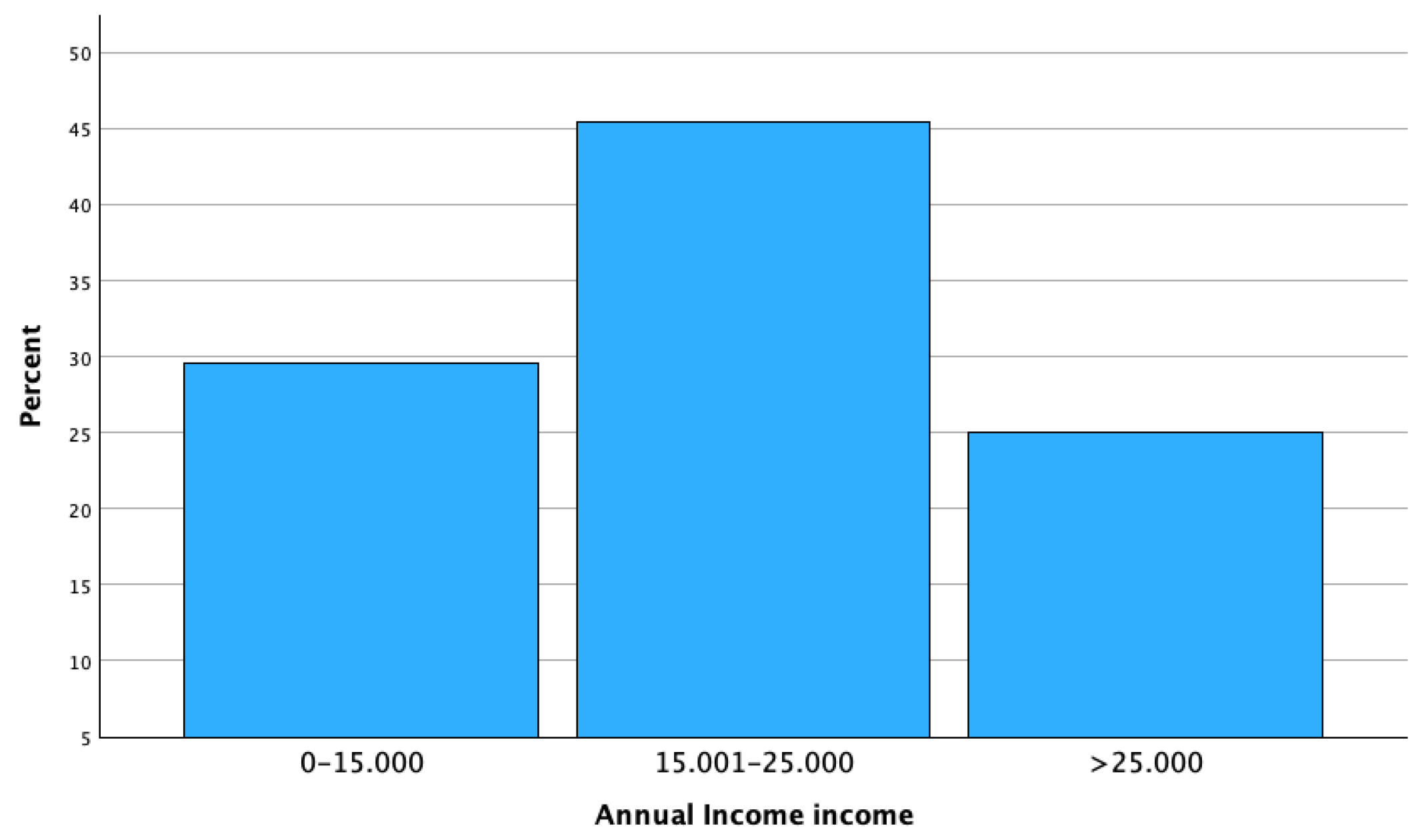

Financial data was available for 43 out of the 50 participating families, as only these respondents provided complete information regarding their household income (€), state allowance receipts (€), and out-of-pocket expenditures (€) related to the child’s condition. Among these families, 51.2% (n = 22) received the extra-institutional care allowance (€846/month), 20.9% (n = 9) received the social solidarity allowance (€338/month), and 27.9% (n = 12) reported receiving no state allowance. In terms of annual household income 30.2% (n = 13) reported income ≤ €15,000, 44.2% (n = 19) reported income between €15,001 - €25,000, 25.5% (n = 11) reported income > €25,001. Among the 12 families who did not receive any form of state allowance, 25% reported annual household income ≤ €15,000, 60% reported income between €15,001 and €25,000, and 25% reported income > €25,001.

The distribution of household income and state support is presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Additionally, among the 12 families who did not receive any form of state allowance (€), 41.6% (n = 5) reported monthly out-of-pocket expenditures (€) related to the child’s condition. Only two families in this group reported incurring unexpected annual expenses, while 41.7% accessed physiotherapy services reimbursed by public insurance. In contrast, among the 22 families receiving the extra-institutional allowance (€846/month), 50% of the children accessed publicly funded physiotherapy. Notably, 77.3% (n = 17) of these families reported monthly out-of-pocket expenses, with 17.6% of them indicating that these expenses exceeded the total value of the monthly allowance. Furthermore, 72.7% (n = 16) reported unexpected annual costs. In addition, families receiving the extra-institutional allowance consistently reported lower HRQoL scores in bivariate analyses Among the nine families receiving the lower social allowance (€338/month), the majority (66.6%) accessed publicly reimbursed physiotherapy. All nine families reported monthly out-of-pocket healthcare costs, and in 55.5% of these cases, the costs exceeded the value of the allowance. Only one family in this group reported unexpected annual expenses.

3.2.1. Overall Financial Burden

A closer examination of the financial data as assessed by the socioeconomic questionnaire for the 43 families who provided complete information revealed that approximately 75% had an annual household income below €25,000. Specifically, 30.2% reported income up to €15,000, 44.2% reported between €15,001 and €25,000, and only 25.6% earned more than €25,001. Importantly, in 28% (12 out of 43) of these families, monthly out-of-pocket expenses related to the child’s condition exceeded the amount of the state allowance, where such allowance was received. In 16.7% of cases (n = 7), the allowance only partially covered these expenses, while in 11.6% of cases (n = 5), families reported no financial relief from the allowance whatsoever. These findings highlight a substantial financial burden, particularly among low- to middle-income households. For the lowest income group, these out-of-pocket costs can represent up to one-quarter of the family’s total annual income.

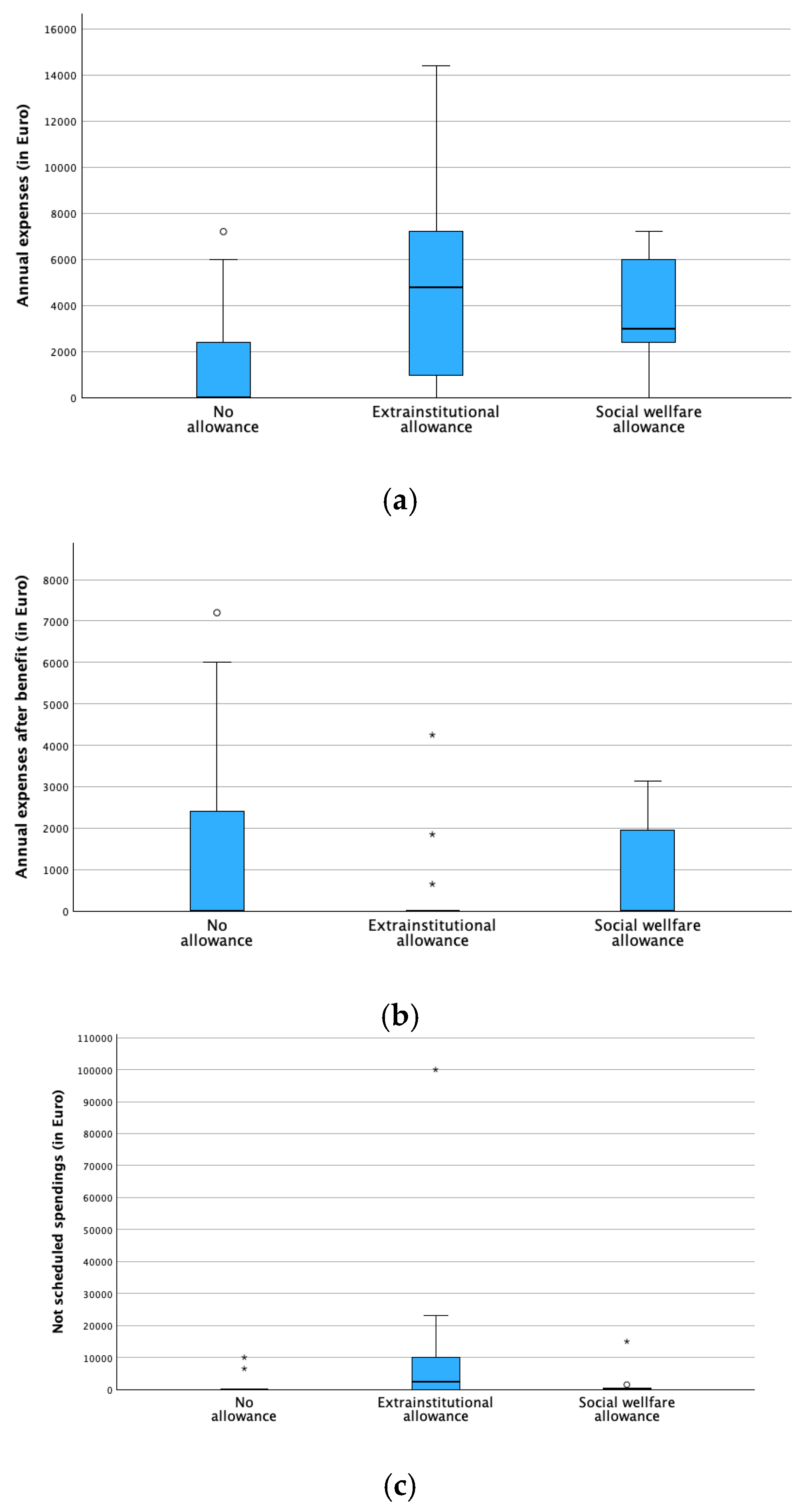

Figure 3 presents box plots comparing annual out-of-pocket expenses (before and after receiving allowances) and unexpected annual expenses across three allowance groups.

These visualizations clearly illustrate the financial burden differences and the mitigating impact of state support. Families receiving no allowance generally reported lower expenses but with considerable variability. Those receiving the extra-institutional allowance showed significantly higher gross annual expenses; however, their net financial burden dropped markedly after allowance receipt (mean: €306.55), indicating substantial financial relief. The social welfare group also experienced a reduction in net costs (mean: €897.60), though less pronounced. Notably, unexpected annual expenses were especially high and variable in the extra-institutional group, with a maximum of €100,000 and a median of €2,500 potentially reflecting a concentration of complex medical needs or acute events within this subgroup.

To further understand the determinants of financial burden among participating families, additional analyses were performed to identify factors associated with expenditures due to the child’s condition. The following results emerged:

a) Unexpected annual expenses (€). These were significantly associated with three factors: wheelchair dependency, receipt of a state allowance, and the geographic region of the family's residence. Regional comparisons categorized families into three groups: (i) those living in the prefecture of Attica (which includes the capital, Athens), (ii) those in the prefecture of Thessaloniki (the second-largest urban area), and (iii) families in all other regions, labeled as “Other” (typically rural or agricultural areas). Statistical testing indicated that the distribution of unexpected annual expenses differed significantly between “Attica” and “Other,” and between “Thessaloniki” and “Other.”

b) Regular annual expenses (€). Calculated by multiplying reported monthly out-of-pocket costs by 12, these expenses were also associated with allowance status and regional residence. Interestingly, a different pattern emerged compared to unexpected costs. In this case, significant differences were observed between “Attica” vs. “Other” and “Attica” vs. “Thessaloniki,” suggesting that families in urban centers like Athens are more likely to incur recurring costs, possibly due to greater access to specialized services or higher living costs. Similarly, high-cost, one-time expenditures such as home or vehicle modifications to accommodate wheelchair access were observed more frequently in urban areas compared to rural ones.

3.2.2. Impact of Caregiving on Maternal Employment

The demands of daily caregiving for a child with DMD significantly influence maternal employment patterns and household economic resilience. In most participating families, mothers assumed the primary caregiving role, often at the expense of their employment status. Among 43 families providing complete data, only half of the mothers were employed full-time, 14.2% part-time, and 35.7% were not employed due to their child’s condition. In families where mothers maintained full-time employment, most fathers were also employed, and these households tended to report higher incomes. However, one-third did not receive any form of state allowance, and several still faced monthly out-of-pocket expenditures that exceeded or matched the value of the benefits received. Families in which mothers worked part-time or were not employed reported lower household incomes and greater caregiving strain, both in time and resources. These families also experienced higher unmet financial needs, with many reporting that monthly expenditures were not adequately covered by allowances.

Wheelchair dependency used as a proxy for functional impairment was more common among children whose mothers were unemployed, indicating a direct link between care intensity and maternal labor force withdrawal. Overall, these findings highlight the dual economic burden of direct care costs and lost maternal income, underscoring the need for targeted support policies that recognize caregiving as a critical determinant of family vulnerability in the context of rare, chronic pediatric conditions.

3.3. Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes

The combined use of the Greek versions of the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales (GC) (Cronbach’s α > 0.70 across all subscales) [

38] and the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module with measured Cronbach’s α values: α = 0.80 for child self-report; α = 0.89 for parent proxy-report [

39] allowed for a comprehensive assessment of HRQoL in children with DMD. As shown in

Table 2, GC scores reported by both children and their parents indicated an overall moderate to good HRQoL. Interestingly, HRQoL scores were more favorable when assessed with the disease-specific DMD Module (

Table 3), which captures condition-related challenges and coping mechanisms. These findings suggest that, despite the clinical and functional limitations of DMD, families often perceive their children's HRQoL in a relatively positive light when framed within the context of disease-specific expectations and adaptations.

In our study sample, the degree of agreement between child self-reports and parent proxy-reports was excellent for the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales (ICC = 0.908; 95% CI: 0.870–0.938) and very good for the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module (ICC = 0.868; 95% CI: 0.815–0.911), indicating high consistency between informants. These findings highlight the continued importance and reliability of parent-reported outcomes in the post-COVID-19 era, particularly when healthcare access remains fragmented or constrained.

Table 4 presents the correlations between the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales and the disease-specific domains of the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module. Statistically significant associations were identified between the psychosocial functioning dimensions (emotional, social, and school functioning) of the Generic Core Scales and the “Worry” and “Communication” domains of the DMD Module.

These findings highlight the interconnectedness of general well-being and disease-specific challenges in children with DMD, particularly in the aftermath of pandemic-related disruptions in pediatric neuromuscular care. The results underscore the importance of maintaining integrated psychosocial support and clear communication pathways between healthcare providers, patients, and families, especially during periods of systemic strain. They also reinforce the value of patient- and proxy-reported outcomes in monitoring HRQoL when routine clinical care remains inconsistent or only partially restored in the post-pandemic landscape.

3.3.1. Quality of Life Compared to Healthy Peers

In our study, children with DMD exhibited significantly lower HRQoL scores on the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales compared to healthy peers [

45] and children with other chronic conditions [

45]. Specifically, their self-reported scores were markedly reduced (mean = 60.65, SD = 16.32 vs. 83.91, SD = 12.47), as were parent proxy-reports (mean = 57.80, SD = 19.42 vs. 82.29, SD = 15.55), when compared with healthy children in the validation study of PedsQL 4.0 GC by Varni [

45]. Moreover, their scores were also lower than those of children with other chronic conditions such as asthma, diabetes, ADHD, and depression (self-reports: mean = 74.16, SD = 15.38; parent proxy-reports: mean = 73.14, SD = 16.44). A similar pattern was observed in age-specific comparisons. In our Greek cohort of children aged 8–12 with DMD, self-reports (mean = 59.86, SD = 15.10) and parent proxy-reports (mean = 60.82, SD = 16.90) were significantly lower than those of both healthy peers [

38] (self-reports: mean = 82.52, SD = 11.28; parent proxy-reports: mean = 83.66, SD = 12.95) and children with chronic conditions [

38] (self-reports: mean = 71.94, SD = 12.60; parent proxy-reports: mean = 71.80, SD = 16.37) as reported by Gkoltsiou [

38]. These findings underscore the profound and unique burden of DMD on the HRQoL of affected children and their families.

3.4. Associations Between Socioeconomic and Clinical Variables and HRQoL domains

The findings presented in

Table 5 are based on non-parametric statistical tests (Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U, α = 0.05), which revealed significant differences in HRQoL scores across various socioeconomic and clinical categories. One of the most prominent findings relates to the receipt of state allowances. Significant associations were observed across all scales of the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module and nearly all scales of the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales (GC), apart from the school functioning domain. Families receiving the extra-institutional allowance consistently reported lower HRQoL scores compared to those not receiving any allowance, suggesting a diminished perceived HRQoL. A similar, albeit less pronounced, pattern was noted among families receiving the social allowance, who also tended to report lower scores than non-recipients. Furthermore, unexpected annual expenditures and continuous wheelchair use by the child were associated with significantly lower scores on the daily activities, worry, total DMD, physical health summary, and total GC scales. These findings emphasize the substantial burden these factors place on families' overall HRQoL. Monthly out-of-pocket expenses had a specific negative impact on the emotional and treatment domains. Families facing such regular expenses scored lower than those without this financial burden. In contrast, access to health insurance (public or private) was positively associated with emotional, social, and psychosocial functioning. Families with insurance coverage consistently reported higher scores in these domains than uninsured families. Child age also emerged as a significant determinant of HRQoL. Families of older children (ages 8–12 and 13–18) consistently reported lower scores than those with younger children, likely reflecting the progressive nature of DMD and the corresponding physical and psychosocial decline. Among the eleven factors assessed, parental employment status and educational level were not significantly associated with HRQoL outcomes. The receipt of state allowance appeared to be the most influential factor, significantly affecting the daily activities, worry, and communication domains of the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module, as well as physical health, social functioning, psychosocial health, and total scores in the PedsQL™ 4.0 GC. This influence was most pronounced in the treatment domain and total score of the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module, and the emotional domain of the PedsQL™ 4.0 GC, particularly when comparing non-recipients with recipients of extra-institutional or social benefits. Unexpected annual expenses and health insurance coverage also played a key role in shaping HRQoL. Unexpected costs were most strongly associated with the daily activities and worry domains of the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module, and with physical health and total scores of the PedsQL™ 4.0 GC. Insurance coverage was linked to better emotional functioning and overall scores.

Child age significantly influenced HRQoL, especially in the physical health domain (PedsQL™ 4.0 GC) and worry domain (PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module). Notable differences were observed between the 5–7 and 13–18 age groups for physical health, and between the 8–12 and 13–18 groups for worry. Other factors, such as monthly out-of-pocket expenses and clinical variables (e.g., corticosteroid use and wheelchair reliance), were associated with more modest differences in HRQoL. Given the strong influence of state allowance, additional analyses incorporating annual routine and unexpected out-of-pocket expenses revealed a moderate (~40%) correlation between allowance status and both HRQoL and disease severity. This correlation persisted even when expenses were expressed as a percentage of household income. In contrast, correlations involving unexpected expenses were substantially weaker.

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of the socioeconomic and psychosocial burden of DMD in Greece during the post-pandemic period. Consistent with international evidence [

46,

47,

48], our study confirmed that children with DMD experience substantially lower HRQoL compared not only to healthy peers but also to children with other chronic conditions, a pattern observed across age groups and reported in both self-reports and parent proxy-reports. Our findings extend the evidence from previous studies using the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales, which consistently demonstrated higher scores among healthy children and those with asthma, diabetes, ADHD, and depression [

38,

45]. Taken together, these comparisons highlight the unique and disproportionate burden of DMD on children’s daily functioning and family well-being, extending beyond the impairment typically observed in other pediatric chronic diseases. To further contextualize these findings, international comparisons reveal both shared patterns and country-specific differences. Analyses of PedsQL™ 4.0 scores demonstrated that physical health was consistently low across all cohorts, reflecting universal functional limitations in DMD. Greek children scored slightly higher than those in Switzerland and Australia [

46,

48], but somewhat lower than in China [

47]. In contrast, psychosocial functioning was relatively favorable, with Greek children and parents reporting outcomes comparable to or higher than those observed in China and the USA [

47,

49]. Parents rated school functioning particularly positively, yielding the highest scores among all international comparisons. Taken together, these results confirm that while physical functioning is uniformly impaired across contexts, psychosocial well-being varies by cultural and healthcare environment [

46,

47,

49,

50]. In Greece, the relatively favorable psychosocial outcomes may reflect strong family cohesion, effective school integration, and robust informal support networks.

Consistent with the relatively favorable psychosocial profile captured through the generic PedsQL™ 4.0, disease-specific assessments further underscore the adaptability and family-centered strengths characterizing Greek families affected by DMD. Disease-specific HRQoL, as measured with the PedsQL™ 3.0 DMD Module, was higher among Greek patients than in Canada [

48] and the USA [

49]. Strong concordance between child and parent reports was observed, diverging from the discrepancies typically found in pediatric chronic illness research [

51,

52]. This concordance may reflect the intensive involvement of caregivers, particularly mothers, within the Greek context. Notably, this pattern persisted even during the post-COVID period, as no decline in HRQoL was observed in Greece, further highlighting family resilience and the adaptability of support systems.

Despite these generally favorable outcomes, within-country differences were also evident, reflecting the influence of geographic and socioeconomic factors on the lived experience of DMD in Greece. Disparities emerged between urban and rural families: those in Athens reported higher expenditures, likely to reflect greater access to specialized services, while rural families incurred fewer costs due to barriers in access or financial constraints. COVID-19 restrictions further amplified these inequities. Beyond clinical and financial indicators, psychosocial functioning remained stable despite pandemic disruptions. Emotional and school functioning scores were relatively high, suggesting effective coping and integration mechanisms. Strong parent–child agreement supports the reliability of proxy reports when clinical access is limited, while differences in daily activity ratings underscore the importance of incorporating both perspectives into care.

The financial analysis illustrated the vulnerability of affected families. Nearly 28% reported monthly healthcare costs equal to or exceeding their state allowance, and among low-income households, out-of-pocket spending represented up to one quarter of annual income. Partial or absent insurance coverage compounded this burden. Gaps in the Greek health system, including limited reimbursement of recommended non-physiotherapy interventions [

5,

6,

7], further exacerbate inequities. Beyond these systemic shortcomings, families also faced substantial out-of-pocket expenditures and intensive caregiving demands. Those receiving the extra-institutional allowance often reported lower HRQoL scores, likely reflecting greater disease severity. Unexpected annual costs and wheelchair dependency were similarly associated with reduced HRQoL, underscoring the combined clinical and financial pressures experienced by families. Two main groups of influencing factors emerged. First, socioeconomic supports such as state allowances and insurance coverage were strongly associated with HRQoL, highlighting the protective role of adequate financial assistance. Second, clinical characteristics including age [

47,

53] and ambulation status [

54], directly affected functioning, in line with the progressive nature of DMD and previous studies. The effects of corticosteroids on HRQoL remain inconclusive, in line with mixed evidence in the literature [

45,

48,

53]. Interestingly, parental education, employment status, and household income were not directly associated with HRQoL, suggesting that condition-specific supports weigh more heavily than broader socioeconomic characteristics. The high prevalence of maternal caregiving further reinforces the gendered nature of care and its implications for family resilience.

Unlike previous Southern European investigations that primarily emphasized cost-of-illness estimates [

30,

31,

32], our study integrates validated disease-specific HRQoL measures with socioeconomic data on allowances, maternal employment, and regional disparities. This dual framework illustrates how financial strain and caregiving responsibilities intersect with clinical progression to shape patient and family outcomes. By situating these findings within a fragmented Southern European welfare model, we provide context-specific insights that complement existing international reviews and highlight challenges faced by other resource-constrained systems. Importantly, our combined approach revealed strong associations between financial protection mechanisms (such as state allowances and insurance coverage) and HRQoL outcomes—an issue insufficiently addressed in prior research [

29,

35,

36,

37], where HRQoL and cost dimensions were typically examined in isolation. These results therefore provide novel evidence on how financial supports interact with disease severity to influence the lived experience of families. Internationally, cost of illness studies from Denmark [

33] and Japan [

34] have quantified the long-term economic impact of DMD, focusing on healthcare expenditure and productivity loss. However, they did not integrate disease-specific HRQoL outcomes with socioeconomic indicators. Our study therefore extends this literature by explicitly linking financial protection mechanisms, caregiving roles, and clinical severity within a post-pandemic Southern European welfare context.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference regarding the relationships between disease severity, financial burden, and HRQoL. The lack of a control group and the inability to conduct multivariable regression further restricted causal interpretation. Nevertheless, these descriptive findings provide a valuable starting point for strengthening preparedness and support in rare disease care. Future longitudinal and comparative studies, ideally including pre- and post-pandemic cohorts, are needed to confirm associations and inform sustainable policy development. Second, although patients were recruited from two major neuromuscular clinics, the relatively small sample may limit generalizability. Third, the socioeconomic questionnaire, though adapted from European frameworks and piloted, was not formally validated, limiting comparability with other cost-of-illness studies. Most importantly, the absence of a pre-pandemic comparator cohort prevents direct attribution of changes in HRQoL or financial burden to COVID-19.

Despite these limitations, this study represents a significant contribution. It identifies three health policy priorities: (i) strengthening the adequacy and targeting of state allowances, (ii) expanding reimbursement to cover the full range of multidisciplinary therapies, and (iii) addressing regional inequities in access to specialized neuromuscular care. More broadly, it provides actionable evidence for clinicians, health system planners, and policymakers. By integrating clinical, financial, and caregiving dimensions within a post-pandemic context, the Greek experience adds to the international dialogue on improving resilience and equity in rare disease care. Moreover, the findings carry relevance not only for Greece but also for other countries facing similar challenges in rare disease management. By situating our findings within a Southern European welfare model characterized by fragmented social protection and limited reimbursement for multidisciplinary care, we highlight systemic challenges that are highly relevant in other resource-constrained settings.

5. Conclusion

This study provides context-specific evidence on the socioeconomic and psychosocial impact of DMD in Greece during the post-pandemic period. By integrating validated, disease-specific HRQoL measures with detailed socioeconomic data, it demonstrates that HRQoL cannot be explained by clinical factors alone. Financial strain, caregiving roles, and regional disparities emerge as equally critical determinants that must be embedded into HRQoL frameworks for rare diseases. Positioning our findings within a Southern European welfare model characterized by fragmented social protection and limited reimbursement for multidisciplinary care highlights systemic challenges with clear international relevance. Countries facing similar resource constraints may benefit from these insights when designing policies for rare disease management.

Although the cross-sectional design and absence of a pre-pandemic comparator limit causal inference, this study is among the first to document the intersection of clinical severity, socioeconomic support, and family resilience in a post-pandemic context. In doing so, the Greek experience contributes to the international dialogue on building more resilient and equitable health systems for rare pediatric diseases, emphasizing the importance of embedding financial and caregiving dimensions into both research and policy frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, E.K.; writing- review and editing, supervision C. K.; writing-review and editing, E.C.; software, data curation, validation, formal analysis, G.M.; review and editing E.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board University of Peloponnese (prot.no 11415/31-5-2023) and of AHEPA Hospital Ethics Committee (prot.no239/16-5-2022) Patras Hospital Ethics Committee (prot.no.246/31-5-2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from both parents or legal guardians in accordance with national regulations for pediatric research, unless sole custody/legal guardianship was documented. Assent was obtained from children aged ≥8 years when appropriate.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements to MDA-Hellas personnel for their contribution in communication with the patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ryder, S.; Leadley, RM.; Armstrong, N.; Westwood, M.; De Kock, S.; Butt, T.; Jai, M.; Kleijnen, J. The burden, epidemiology, costs and treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: An evidence review. Orphanet J of Rare Dis, 2017, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, S.; Vita, GL. ; Clinical management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: the state of the art. Neurol Sci, 2018, 39, 1837–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, S.; Sultana, J.; Fontana, A.; Salvo, F.; Messina, S.; Messina, S.; Trifiro, G. Global epidemiology of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J of Rare Dis, 2020, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Thongsing, A.; Likasitwattanakul, S.; Sanmaneechai, O. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the Pediatric Quality of Life inventoryTM 3.0 Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy module in Thai children with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2019, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnkrant, DJ.; Bushby, K.; Bann, CM.; Apkon, SD.; Blackwell, A.; Brumbaugh, D.; Case, L.; Clemens, P.; Hadjigiannakis, S.; Pandya, S.; et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol, 2018, 17, 251–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnkrant, DJ.; Bushby, K.; Bann, CM.; Alman, BA.; Apkon, SD.; Blackwell, A.; Case, L.; Cripe, L.; Hadjigiannakis, S.; Olson, A.; et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol, 2018, 17, 347–61. [Google Scholar]

- Birnkrant, DJ.; Bushby, K.; Bann, CM.; Apkon, SD.; Blackwell, A.; Colvin, M.; Cripe, L.; Herron, A.; Kennedy, A.; Kinnet, K.; et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol 2018, 17, 445-55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelini, C.; Peterle, E. Old and new therapeutic developments in steroid treatment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Myol, 2012, 31, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takeda, S.; Clemens, PR.; Hoffman, EP. Exon-Skipping in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis, 2021, 8, 343–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markati, T.; Oskoui, M.; Farrar, MA.; Duong, T.; Goemans, N.; Servais, L. Emerging therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Lancet Neurol 2022, 21, 814-29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, M.; Frey, J.; Shohan, MJ.; Malek, S.; Mousa, SA. Current and emerging therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy. Pharmacol Ther 2021, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, X. Therapeutic strategies for duchenne muscular dystrophy: An update. Genes, 2020, 11, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, RJ.; Kirkov, S.; Conway, KM.; Johnson, N.; Matthews, D.; Phan, H.; Cai, B.; Paramsothy, P.; Thomas, S.; Feldkamp, M. Evaluation of effects of continued corticosteroid treatment on cardiac and pulmonary function in non-ambulatory males with Duchenne muscular dystrophy from MD STARnet. Muscle Nerve, 2022, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, PB.; McIntosh, J.; Jin, F.; Souza, M.; Elfring, G.; Narayanan, S.; Thrifillis, P.; Peltz, S.; McDonald, C.; Darras, B.; et al. Deflazacort versus prednisone/prednisolone for maintaining motor function and delaying loss of ambulation: A Post Hoc analysis from the ACT DMD trial. Muscle Nerve, 2018, 58, 639–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landfeldt, E.; Edström, J.; Buccella, F.; Kirschner, J.; Lochmüller, H. Duchenne muscular dystrophy and caregiver burden: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol., 2018, 60, 987–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlgren, L.; Kroksmark, AK.; Tulinius, M.; Sofou, K. One in five patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy dies from other causes than cardiac or respiratory failure. Eur J Epidemiol, 2022, 37, 147–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broomfield, J.; Hill, M.; Guglieri, M.; Crowther, M.; Abrams, K. Life expectancy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology, 2021, 97, 304–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eu, WH.; Busse, R.; Klazinga, N.; Panteli, D.; Quentin, W. The editors Improving healthcare quality in Europe Characteristics, effectiveness and implementation of different strategies. Health Policy Series, 2019, 53, 4–30. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Health Union: acting together for people’s health COM (2024) 206 final. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/publications/communication-european-health-union_en#details (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Whittal, A.; Meregaglia, M.; Nicod, E. The Use of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Rare Diseases and Implications for Health Technology Assessment. Patient, 2021, 24, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettschneider, C.; Luhmann, D.; Raspe, H. Informative value of Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO) in Health Technology Assessment (HTA). Health Technol Assess, 2011, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kyte, D.; Duffy, H.; Fletcher, B.; Gheorghe, A.; Mercieca-Bebber, R.; King, M.; Draper, H.; Ives, J.; Brundage, M.; Blazeby, J.; et al. Systematic evaluation of the patient-reported outcome (PRO) content of clinical trial protocols. J Am Med Assoc, 2014, 319, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigg, A.; Howells, R. Patient-Reported Outcomes within Health Technology Assessment Decision Making: Current Status and Implications for Future Policy. Value Health 2015, 18, A 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazza, M.; Kodra, Y.; Armeni, P.; De Santis, M.; López-Bastida, J.; Linertová, R.; Oliva-Moreno, J.; Serano-Aguilar, P.; Posata-de la Paz, M.; Taruscio, D. , et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy in Europe. European J Health Econ, 2016, 17, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Teoh, LJ.; Geelhoed, EA.; Bayley, K.; Leonard, H.; Laing, NG. Health care utilization and costs for children and adults with duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve, 2016, 53, 877–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thayer, S.; Bell, C.; McDonald, C. The Direct Cost of Managing a Rare Disease: Assessing Medical and Pharmacy Costs Associated with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm, 2017, 23, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber-Katz, O.; Klug, C.; Thiele, S.; Schorling, E.; Zowe, J.; Reilich, P.; Nageis, K.; Walter, M. Comparative cost of illness analysis and assessment of health care burden of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies in Germany. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkindale, J.; Yang, W.; Hogan, PF.; Simon, CJ.; Zhang, Y.; Jain, A.; Habeeb-Louks, E.; Kennedy, A.; Cwik, V. Cost of illness for neuromuscular diseases in the United States. Muscle Nerve, 2014, 49, 431–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, Z.; Rabea, H.; El Sherif, R.; Abdelrahim, M.; Dawoud, D. Estimating Societal Cost of Illness and Patients’ Quality of Life of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in Egypt. Value Health Reg Issues, 2023, 33, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, D.; Ribate, M.; Montolio, M.; Ramos, F.; Gómez, M.; García, C. Quantifying the economic impact of caregiving for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in Spain. European J Health Econ, 2020, 7, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labisa, P.; Andreozzi, V.; Mota, M.; Monteiro, S.; Alves, R.; Almeida, J.; Vandewalle, B.; Felix, J.; Buesch, K.; Canhão, H.; et al. Cost of Illness in Patients with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in Portugal: The COIDUCH Study. PharmacoEconomics, 2022, 6, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orso, M.; Migliore, A.; Polistena, B.; Russo, E.; Gatto, F.; Monterubbianesi, M.; d’Angela, D.; Spandonaro, F.; Pane, M. Duchenne muscular dystrophy in Italy: A systematic review of epidemiology, quality of life, treatment adherence, and economic impact. PLos One, 2023, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolfsen, J.; Vissingb, J.; Werlauffc, U.; Olesend, C.; Illume, N.; Olsena, J.; Bo Poulsenf, P.; Strandg, M.; Bornh, A. Burden of Disease of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in Denmark – A National Register-Based Study of Individuals with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and their Closest Relatives. J Neuromusc Dis, 2024, 11, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori-Yoshimura, M.; Ishigaki, K.; Shimizu-Motohashi, Y.; Ishihara, N.; Unuma, A.; Yoshida, S.; Nakamura, H. Social difficulties and care burden of adult Duchenne muscular dystrophy in Japan: a questionnaire survey based on the Japanese Registry of Muscular Dystrophy (Remudy). Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2024, 19, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, C.; Stark, R.; Audhya, I.; Gooch, K. Characterizing the quality-of-life impact of Duchenne muscular dystrophy on caregivers: a case-control investigation. J Patient Rep Outcomes, 2021, 5, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirari, T.; Renu Suthar, R.; Kansra, P.; Singh, A.; Prinja, S.; Malviya, m.; Chauhan, A.; Viswanathan, V.; Gupta, V.; Sankhayan, N. Socioeconomic determinants of the quality of life in boys suffering from Duchenne muscular dystrophy & their caregivers. Indian J Med Res, 2025, 161, 215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Uttley, L.; Carlton, J.; Buckley Woods, H.; Brazier, J. A review of quality of life themes in Duchenne muscular dystrophy for patients and carers. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2018, 16, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkoltsiou, K.; Dimitrakaki, C.; Tzavara, C.; Papaevangelou, V.; Varni, JW.; Tountas, Y. Measuring health-related quality of life in Greek children: Psychometric properties of the Greek version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory TM 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Qual Life Res 2008, 17, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsomiti, E.; Kastanioti, C.; Chroni, E.; Mavridoglou. G. Reliability and validity of the Greek version of the Pediatric Quality of Life InventoryTM 3.0 Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy module in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Paliat Med Pract, 2025, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Angelis, A.; Tordrup, D.; Kanavos, P. Socio-economic burden of rare diseases: A systematic reviewof cost of illness evidence. Health Policy, 2015, 119, 964–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin Brodszky, V.; Beretzky, Z.; Baji, P.; Rencz, F.; Péntek, M.; Rotar, A.; Tachkov, K.; Mayer, S.; Judit Simon, J.; Niewada, M.; Hren, R.; Gulácsi, L. Cost-of-illness studies in nine Central and Eastern European countries. Eur J Health Economics, 2019, 20, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, L.; Linertová, R.; Valcárcel-Nazco, C.; Posada, M.; Gorostiza, I.; Serrano-Aguilar, P. Cost-of-illness studies in rare diseases: a scoping review. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2021, 16, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, C. Cost-of-illness studies: concepts, scopes, and methods. Clin Molec Hepatology, 2014, 20, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, K.; Grosse, S.; Ouyang, L.; Street, N.; Romitti, P. Direct costs of adhering to selected Duchenne muscular dystrophy Care Considerations: Estimates from a midwestern state. Muscle Nerve, 2022, 65, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, JW.; Seid, M.; Burwinkle, T.; Skarr, D. The PedsQLTM 4. 0 as a pediatric population health measure: Feasibility, Reliability and Validity Ambul Pediatr, 2003, 3, 329–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gocheva, V.; Schmidt, S.; Orsini, AL.; Hafner, P.; Schaedelin, S.; Rueedi, N.; Weber, P.; Fischer, D. Association Between Health-Related Quality of Life and Motor Function in Ambulant and Nonambulant Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patients. J Child Neurol, 2019, 34, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Chan, SHS. ; Ho, FKW.; Tang, OC.; Cherk, SWW.; Ip, P.; Ying Lau, EY. Health-related quality of life in Chinese boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and their families. J Child Health Care, 2019, 23, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzark, K.; King, E.; Cripe, L.; Spicer, R.; Sage, J.; Kinnett, K.; Wong, B.; Pratt, J.; Varni, J. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatrics, 2012, 130, 1559–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, SE.; Hynan, LS.; Limbers, CA.; Andersen, CM.; Greene, MC.; Varni, JW.; Iannaccone, S. The PedsQLTM in Pediatric Patients with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Feasibility, Reliability, and Validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Neuromuscular Module and Generic Core Scales. J Clin Neuromusc dis 2010, 11, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, P.; Bundy, AC.; Ryan, MM.; North, KN.; Everett, A. Health-related quality of life in boys with duchenne muscular dystrophy: Agreement between parents and their sons. J Child Neurol, 2010, 25, 1188–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanania, JW.; George, JE.; Rizzo, C.; Manjourides, J.; Goldstein, L. Agreement between child self-report and parent-proxy report for functioning in pediatric chronic pain. J Patient Rep Outcomes, 2024, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajmil, L.; López, AR.; López-Aguilà, S.; Alonso, J. Parent-child agreement on health-related quality of life (HRQOL): A longitudinal study. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2013, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, C.; Steffensen, BF.; Højberg, AL.; Barkmann, C.; Rahbek, J.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Mahoney, A.; Vry, J.; Gramsch, K.; Thompson, R.; et al. Predictors of Health-Related Quality of Life in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy from six European countries. J Neurol. 2017, 264, 709–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Speechley, KN.; Zou, G.; Campbell, C. Factors Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life in Children with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J Child Neurol, 2016, 31, 879–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).