Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Research Team and Reflexivity

2.3. Context and Setting

2.4. Sampling Strategies and Participants

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Analysis

2.7. Rigor Criteria

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

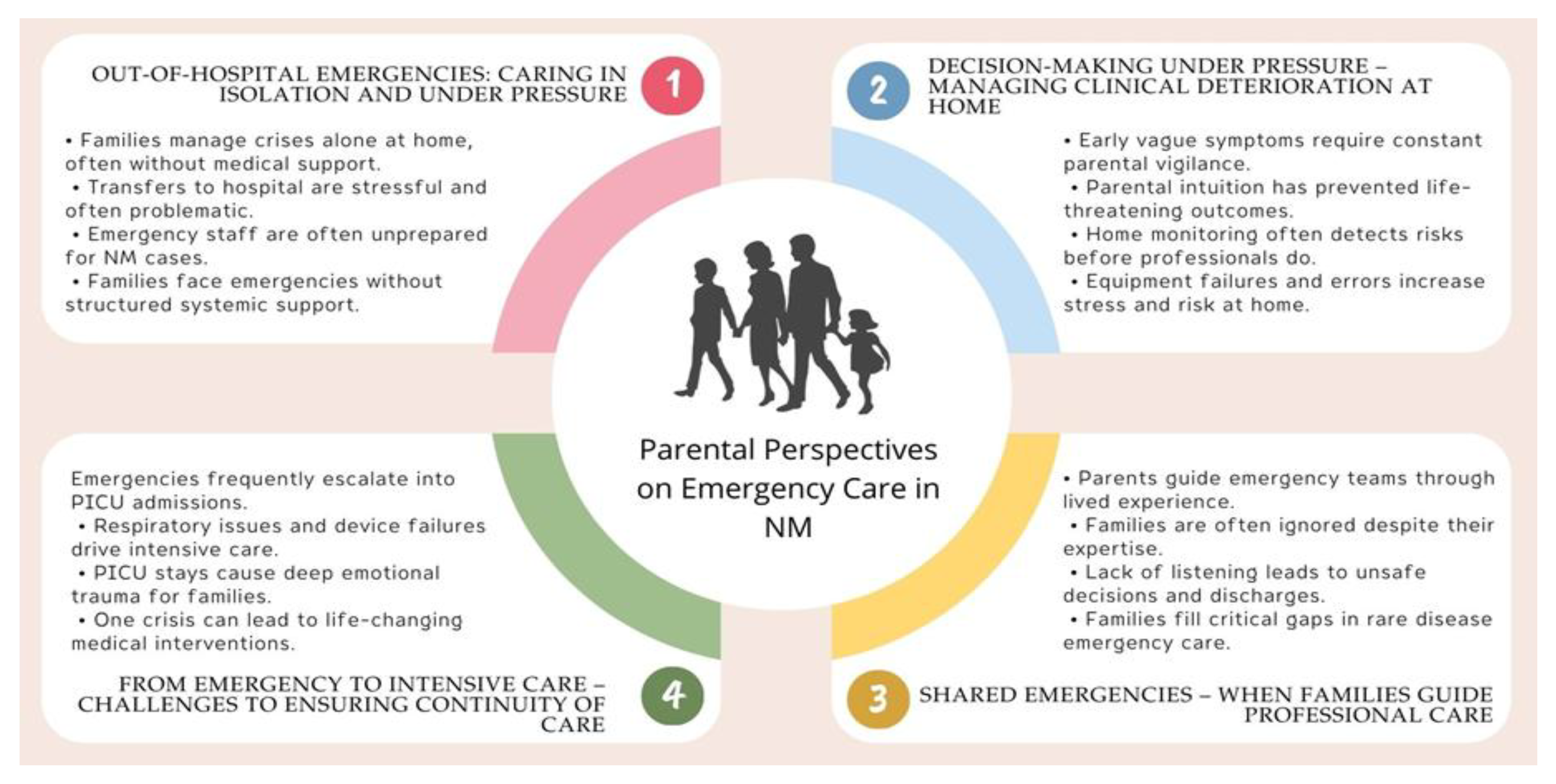

Theme 1. Out-of-Hospital Emergencies: Caring in Isolation and Under Pressure

Theme 2. Decision-Making Under Pressure: Managing Clinical Deterioration at Home

Theme 4. From Emergency to Intensive Care: Challenges to Ensuring Continuity of Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguengang Wakap, S.; Lambert, D.M.; Olry, A.; et al. Estimating cumulative point prevalence of rare diseases: Analysis of the Orphanet database. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haendel M, Vasilevsky N, Unni D, Bologa C, Harris N, Rehm H, et al. How many rare diseases are there? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(2):77–78. [CrossRef]

- Lehtokari VL, Similä M, Tammepuu M, Wallgren-Pettersson C, Strang-Karlsson S, Hiekkala S. Self-reported functioning among patients with ultra-rare nemaline myopathy or a related disorder in Finland: a pilot study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023 Nov 30;18(1):374. [CrossRef]

- Yuen M, Sandaradura SA, Dowling JJ, Kostyukova AS, Moroz N, Quinlan KG, et al. Leiomodin-3 dysfunction results in thin filament disorganization and nemaline myopathy. J Clin Invest. 2014 Nov;124(11):4693–708. Erratum in: J Clin Invest. 2015 Jan;125(1):456–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI80057. [CrossRef]

- Ravenscroft G, Miyatake S, Lehtokari VL, Todd EJ, Vornanen P, Yau KS, et al. Mutations in KLHL40 are a frequent cause of severe autosomal-recessive nemaline myopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2013 Jul 11;93(1):6–18. [CrossRef]

- Polastri M, Schifino G, Tonveronachi E, Tavalazzi F. Respiratory treatment in a patient with nemaline myopathy. Clin Pract. 2019 Dec 19;9(4):1209. [CrossRef]

- Argov Z, de Visser M. Dysphagia in adult myopathies. Neuromuscul Disord. 2021 Jan;31(1):5–20. [CrossRef]

- Finsterer J, Stöllberger C. Review of cardiac disease in nemaline myopathy. Pediatr Neurol. 2015 Dec;53(6):473–7. [CrossRef]

- Alhammadi F, Mohammed AM, Hamad M, Al-Tamimi M. Respiratory failure in a patient with late-onset nemaline myopathy: a case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 2022;37:101651. https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(22)00194-8/fulltext.

- Wang CH, Dowling JJ, North K, Schroth MK, Sejersen T, Shapiro F, et al. Consensus statement on standard of care for congenital myopathies. J Child Neurol. 2012 Mar;27(3):363–82. [CrossRef]

- Benedetto L, Musumeci O, Giordano A, Porcino M, Ingrassia M. Assessment of parental needs and quality of life in children with a rare neuromuscular disease (Pompe disease): a quantitative-qualitative study. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023 Nov 21;13(12):956. [CrossRef]

- Witt S, Schuett K, Wiegand-Grefe S, Boettcher J, Quitmann J. Living with a rare disease—experiences and needs in pediatric patients and their parents. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023;18(1):242. [CrossRef]

- Buckle N, Doyle O, Kodate N, Somanadhan S. The economic impact of living with a rare disease for children and their families: a scoping review. Health Policy. 2023;127(5):575–86. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2007.

- Carpenter C, Suto M. Qualitative research for occupational and physical therapists: a practical guide. Oxford (UK): Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

- Klem NR, Smith A, Shields N, Bunzli S. Demystifying qualitative research for musculoskeletal practitioners Part 1: what is qualitative research and how can it help practitioners deliver best-practice musculoskeletal care? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51(11):531–2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34719941/.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [CrossRef]

- Asociación Yo Nemalínica. Inicio. Available from: https://www.yonemalinica.org/ [Accessed 26 May 2025].

- García-Armesto S, Abaitua I, Durán A, Hernández-Quevedo C. Spain: Health System Summary. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2024. Available from: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/docs/librariesprovider3/publicationsnew/hit-summaries-no-flags/hit-summary-spain-2024-2p.pdf.

- Gimenez-Lozano C, Páramo-Rodríguez L, Cavero-Carbonell C, Corpas-Burgos F, López-Maside A, Guardiola-Vilarroig S, et al. Rare diseases: needs and impact for patients and families: a cross-sectional study in the Valencian Region, Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):10366. [CrossRef]

- Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):9–18. [CrossRef]

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–1907. [CrossRef]

- Archibald MM, Ambagtsheer RC, Casey MG, Lawless M. Using Zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int J Qual Methods. 2019;18:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Hernán-García M, Lineros-González C, Ruiz-Azarola A. How to adapt qualitative research to confinement contexts. Gac Sanit. 2020. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE; 2018.

- Giorgi, A. The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: a modified Husserlian approach. Pittsburgh (PA): Duquesne University Press; 2009.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245–51. [CrossRef]

- Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24:120–4.

- Satchell E, Carey M, Dicker B, Drake H, Gott M, Moeke-Maxwell T, et al. Family & bystander experiences of emergency ambulance services care: a scoping review. BMC Emerg Med. 2023 Jun 14;23(1):68. [CrossRef]

- Yao H, Li K, Li C, Hu S, Huang Z, Chen J, et al. Caregiving burden, depression, and anxiety in informal caregivers of people with mental illness in China: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2024 Nov 19;24(1):824. [CrossRef]

- Racca F, Sansone VA, Ricci F, Filosto M, Pedroni S, Mazzone E, et al. Emergencies cards for neuromuscular disorders: 1st Consensus Meeting from UILDM - Italian Muscular Dystrophy Association Workshop report. Acta Myol. 2022 Dec 31;41(4):135–77. [CrossRef]

- Baker K, Claridge AM. "I have a Ph.D. in my daughter": mother and child experiences of living with childhood chronic illness. J Child Fam Stud. 2022 Dec 12:1–12. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Somanadhan S, McAneney H, Awan A, McNulty S, Sweeney A, Buckle N, et al. Assessing the supportive care needs of parents of children with rare diseases in Ireland. J Pediatr Nurs. 2025;81:31–42. [CrossRef]

- Ronan S, Brown M, Marsh L. Parents’ experiences of transition from hospital to home of a child with complex health needs: a systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(17–18):3222–35. [CrossRef]

- Gong S, Wang X, Wang Y, Qu Y, Tang C, Yu Q, et al. A descriptive qualitative study of home care experiences in parents of children with tracheostomies. J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;45:7–12. [CrossRef]

- Mah JK, Thannhauser JE, McNeil DA, Dewey D. Being the lifeline: the parent experience of caring for a child with neuromuscular disease on home mechanical ventilation. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18(12):983–8. [CrossRef]

- Leske V, Guerdile MJ, Gonzalez A, Testoni F, Aguerre V. Feasibility of a pediatric long-term Home Ventilation Program in Argentina: 11 years’ experience. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55(3):780–7. [CrossRef]

- Adachi T, El-Hattab AW, Jain R, Nogales Crespo KA, Quirland Lazo CI, Scarpa M, et al. Enhancing equitable access to rare disease diagnosis and treatment around the world: a review of evidence, policies, and challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(6):4732. [CrossRef]

- Coller RJ, Lerner CF, Berry JG, Klitzner TS, Allshouse C, Warner G, et al. Linking parent confidence and hospitalization through mobile health: a multisite pilot study. J Pediatr. 2021;230:207–14.e1. [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Toledano F, Luna D. The psychosocial profile of family caregivers of children with chronic diseases: a cross-sectional study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2020;14:29. [CrossRef]

- Cormican O, Dowling M. The hidden psychosocial impact of caregiving with chronic haematological cancers: a qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2023;64:102319. [CrossRef]

- Pelentsov LJ, Fielder AL, Laws TA, Esterman AJ. The supportive care needs of parents with a child with a rare disease: results of an online survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:88. [CrossRef]

- Verberne LM, Schouten-van Meeteren AY, Bosman DK, Colenbrander DA, Jagt CT, Grootenhuis MA, et al. Parental experiences with a paediatric palliative care team: A qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2017;31(10):956–63. [CrossRef]

- Boivin A, Lehoux P, Lacombe R, Burgers J, Grol R. Involving patients in setting priorities for healthcare improvement: A cluster randomized trial. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):45. [CrossRef]

- Carel H, Kidd IJ. Epistemic injustice in healthcare: a philosophical analysis. Med Health Care Philos. 2014;17(4):529–40. [CrossRef]

- Zurynski Y, Friesen CA, Williams K, Elliott EJ; Rare Disease Working Group. Rare disease: A national survey of paediatricians’ experiences and needs. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2017;1(1):e000172. [CrossRef]

- Kao WT, Tseng YH, Jong YJ, Chen TH. Emergency room visits and admission rates of children with neuromuscular disorders: A 10-year experience in a medical center in Taiwan. Pediatr Neonatol. 2019;60(4):405–10. [CrossRef]

- Lean RE, Rogers CE, Paul RA, Gerstein ED. NICU hospitalization: Long-term implications on parenting and child behaviors. Curr Treat Options Pediatr. 2018;4(1):49. [CrossRef]

- Brødsgaard A, Pedersen JT, Larsen P, Weis J. Parents’ and nurses’ experiences of partnership in neonatal intensive care units: A qualitative review and meta-synthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(17-18):3117–39. [CrossRef]

- Hill C, Knafl KA, Docherty S, Santacroce SJ. Parent perceptions of the impact of the PICU environment on delivery of family-centered care. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;50:88. [CrossRef]

- Butler AE, Krall F, Shinewald A, Manning JC, Choong K, Dryden-Palmer K. Family-centered care in the PICU: Strengthening partnerships in pediatric critical care medicine. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2024;25(12):1192–8. [CrossRef]

| Research Areas and Questions |

|---|

| Parental Emergency Management: This area explores how parents handle critical situations at home without immediate professional support, and how this impacts their caregiving experience and their role as first responders. Interview questions: Could you describe an emergency situation you experienced with your child at home? How did you respond? Did you feel technically and emotionally prepared to act in those situations? What helped you—or what did you feel was missing? How did you experience the hospital transfer during those critical moments? What emotions do you recall from that time? |

| Home-Based Response to Clinical Deterioration: This area aims to understand how families identify warning signs, make decisions, and cope with the emotional and technical implications of managing clinical decline in the home setting. Interview questions: Have you ever noticed signs of deterioration in your child’s health? How did you know it was time to act? What tools or devices do you use to monitor your child? How do they influence your decision-making? Have you experienced failures of medical equipment at home? How did you manage the situation? How have you experienced moments when you had to intervene in response to a potential clinical decline? |

| Parental Involvement in Pediatric Emergency Care: This area examines how parents take on an active role during hospital emergencies, compensate for system shortcomings, and face the emotional challenge of not being fully recognized as part of the care team. Interview questions: What has your experience been like during emergency visits with your child?To what extent have you been involved in your child’s care during those episodes?Have you ever had to explain your child’s condition or instruct professionals on how to act? How did you handle that situation?What do you think healthcare professionals should understand about your role as a caregiver in emergency situations? |

| Transition from Emergency Care to the PICU: This area explores how families experience the transition from the emergency department to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), how they cope with the emotional impact, and how they take on an active role in medical decision-making. Interview questions: How did you experience your child’s transition from the emergency department to the PICU?What emotions did you feel during the admission? How did it affect you and your family?To what extent were you involved in the decision-making process?Could you describe any intervention or procedure that marked a turning point in your child’s clinical progression? |

| Throughout the interviews, researchers employed prompts and probes as needed to deepen the discussion. These included encouraging participants to elaborate, maintaining the conversational flow, clarifying unclear statements through paraphrasing, and demonstrating active listening. Examples of such prompts included: “Could you tell me more about that?”, “Have you experienced something similar since?”, and “That’s really interesting—please go on.” |

| Marital Status | Married 64,7% | Single 29,4% | Divorced 5,9% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Children | 1 child: 41,2% | 2 children: 41,2% | 3 children: 17,6% | ||

| Child’s Sex | 50% Female | 50% Male | |||

| Type of Residence | 70,6% Urban | 17,6% Rural | 11,8% Semi-urban | ||

| Housing Tenure | 88,2% Owned | 11,8% Social housing | |||

| Vehicle Ownership | 70,6% Yes | 29,4% No | |||

| Educational Attainment | 70,6% University | 17,6%Vocational training | 11,8% Secondary | ||

| Employment Status | 5,9% Homemaker | 5,9% Unemployed | 17,6% Parental leave | ||

| Monthly Household Income | 41,2% ≥2000 € |

29,4% 1500 - 2000 € |

17,6% 1000 - 1500 € |

11,8% ≤1000 € |

|

| Theme 1 |

| Alone in the face of an emergency:“…if you’re in the hospital, you try to solve it, and if not, you press a button and the nurse comes running. At home, you can’t press a button—you’re alone with yourself.” (M1) Home accident and resuscitation: “H2 was taking a bath, I was alone with both kids, his sister was playing and pulled his hand, and he fell with his head into the water. I don’t know how I reacted so fast—I called 112, put the phone on speaker; he turned very purple and I couldn’t find a pulse, so I started doing chest compressions. H2 came back, his color improved. I kept talking to them, explaining everything. They sent an ambulance; meanwhile, I placed the BiPAP and his oxygen started going up—by the time they arrived, it was at 88–90.” (P2) Dramatic transfer on the highway:“…she became very unstable at the hospital, and the transfer could be risky—even they were uncertain. We were driving ahead in our car, and the ambulance was following behind. At one point, the ambulance just stopped in the middle of the highway. It was very dramatic.” (P5) Desperation and a miracle:“…I called the ambulance in a panic… we were so nervous, so scared, I told the person on the phone, please, my daughter is dying. A doctor came who had no idea what to do, gave her oxygen, and we transferred her to the PICU—they told us she had been saved by a miracle.” (M8) |

| Theme 2 |

| Life-saving intuition: “If I hadn’t been so stubborn, my daughter wouldn’t be here. They wanted to send her home, but I kept saying something wasn’t right—I refused to leave. Soon after, her heart rate started climbing, her oxygen dropped, and she went into cardiac arrest. They had to resuscitate her. That image is burned into my memory, no matter how much I want to forget it.” (M4) CO₂ retention:“One day I took her to school, and she fell asleep. When we realized it, her fingernails were blue—she was running out of oxygen. She had been retaining CO₂ for nearly a month. That was her first hospital admission. At two years old, her oxygen dropped to 65 and her CO₂ went up to 210. She was asleep for four days in the PICU.” (M4) Dangerously low oxygen saturation:“At home, my daughter said she felt anxious, unwell, hadn’t wanted to eat for days, just wanted to lie down—she was very tired. I checked her with the pulse oximeter, and she was at 68.” (M8) Ventilator failure:“H3 had a crisis, and the ventilator disconnected. It failed, and by the time we noticed, he was already desaturating.” (P3) Home bronchoaspiration:“Many times I would insert the feeding tube through his nose, and I didn’t know if it was reaching his stomach… He choked twice—one of them was really serious. I was alone and thought he wasn’t going to make it… he started aspirating until it turned into aspiration pneumonia.” (M7) CPR at home:“I’ve never experienced anything worse in my life. I was doing chest compressions, and he was turning grey. I kept thinking, ‘Oh my God, this can’t be happening to me, please.’ I completely broke down when the ambulance arrived—I cried all the way to the hospital. If another parent didn’t know how to react in that moment, their child wouldn’t survive.” (M2) |

| Theme 3 |

| Active role in the emergency department: “We go to the emergency room a lot, and we know what needs to be said—you know when things are going wrong.” (M1) Clinical translator: “Sometimes I can tell the staff feels relieved when I explain everything clearly… I tell them the name of the disease, what could happen, and then they act more calmly. It’s like I’m translating what’s happening for them.” (M1) Unprepared professional:“They sent a pediatrician from the health center who didn’t know anything about NM and told me there was nothing he could do—it devastated me. He was unable to help.” (M8) Misdiagnosis: “They told us it was just gastroenteritis… but it was actually a bowel obstruction. By the time they realized, it was too late… she ended up in emergency surgery.” (M8) Underestimation of respiratory distress: “I kept telling them my child’s oxygen was low, and the doctor said he was fine. Then they used the pulse oximeter, and it read 88 and dropping… that’s when they realized he wasn’t doing as well as they thought.” (M9) Premature discharge:“…we went into the ER in very, very bad shape. The ER was overwhelmed, and they discharged us. The trip home was awful—it was so hard because I could see my son’s lips changing color, but I had no idea what was happening… something told me that color wasn’t normal…” (M7) |

| Theme 4 |

| Frequent readmissions:“Being readmitted felt like coming home—you’d arrive at the PICU, and they treated you like one of their own. After so much time there, you know how everything works.” (P3) From the ER to the PICU:“After a cannula change, she came home with severe tachycardia. I called the complex chronic care unit, and they told us to come back. We went through the ER, and from there straight to the PICU… her left lung had collapsed… it was bronchomalacia in the upper left bronchus.” (M1) Respiratory failure and ventilator malfunction: “Her more severe symptoms started around age two… she had several PICU admissions up to age three—three or four very serious episodes of respiratory failure, and also problems with the ventilator.” (P4) Emotional impact: “She had a PICU admission where she just went lifeless… Thank goodness they were there, they reacted immediately, and later the nurses told us how bad it really was.” (M8) A traumatic admission: “A PICU admission is very, very, very traumatic—until everything stabilizes… that’s when they scheduled the PEG. There was a failed extubation attempt, and in the end, of course, a tracheostomy and invasive ventilation.” (M7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).