Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

11 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Anticancer Properties of the Olive Leaves Compounds

| Complex | Range of Concentration | Types of Cancer | Cell based Models | Examined | References |

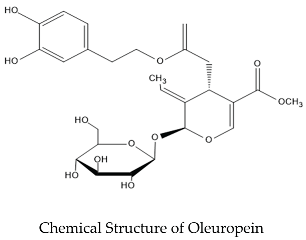

| Oleuropein | 1, 10, 100 μM | Breast | MCF-7 and T-47D | Decline in cell viability with cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase. | [8] |

| Oleuropein | 100, 200 μM | Breast | MCF-7 | Bax Gene Upregulation and activation of p53-dependent apoptotic pathways through increased expression of p53 gene. | [17] |

| Oleuropein | 0 to 100 μM | Breast | MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 | Viability of cell and migration were decreased, with cell cycle arrest at the sub-G1 phase was observed. Apoptosis was increased, indicated by elevated PARP and caspase-3/7 cleavage, along with reduced the activation of NF-κB. | [18] |

| Oleuropein | 0 to 700 μM | Breast | MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 | Reduced the viability of cell, with apoptosis primarily driven by downregulation of the anti-apoptotic genes TNFRSF11B, BIRC5, and CASP4. | [19] |

| Oleuropein | 20 to 100 μM | HCC | HepG2 | Cells showed morphological changes and reduced proliferation, with increased caspase activity and the involvement of family Bcl-2, reduced signaling of PI3K/AKT, but was no change in feasibility. | [20] |

| Oleuropein | 10 to 100 μmol/L | HCC | HepG2 | Cell viability was maintained, with lowered caspase-3 activation. | [21] |

| Oleuropein | 200 μM and 50 μM | HCC | HepG2 | Modulation of the Pro-NGF/NGF ratio through regulation of MMP-7 activity. | [22] |

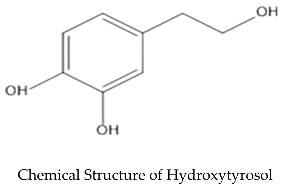

| Hydroxytyrosol | 10 to 40 μM | HCC | HepG2 | No variations in cell integrity or antioxidant levels were observed. | [23] |

| Hydroxytyrosol | 0.5, 1.0, 5.0 and 10.0 μM | HCC | HepG2 | Increased appearance of antioxidant enzymes, enhanced the activation of ERK and AKT pathways, and promoted nuclear translocation of Nrf2 transcription aspect. | [24] |

| Hydroxytyrosol | 30 to 200 μM | HCC | Hep3B e HepG2 | Cytostatic effects through increased FAS expression, enhancement of the endogenous antioxidant system, increased the IL-6 reduction. | [25] |

| Hydroxytyrosol | 1 μM and 5 μM | HCC | HepG2 | Reduced ER stress. | [26] |

| Hydroxytyrosol | 100 to 400 μM | HCC | HepG2, Hep3B, SK-HEP-1 and Huh-7 | Reduced cell proliferation with G2-M arrest, increased cleavage of PARP, suppression of the NF-κB and PI3K/AKT pathways | [27] |

| Hydroxytyrosol | 0 to 100 μM | HCC | HepG2 | Reduced cell viability accompanied by increased cytosolic calcium. | [28] |

2.1. In Vitro Antitumor Effects of Oleuropein

2.2. In Vitro Antitumor Effect of Hydroxytyrosol

3. Olive-Derived Antioxidants: Anti-Inflammatory Properties in In Vitro Studies

3.1. Olive Polyphenols as Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Agents in Animal Studies

3.2. Molecular Mechanism of Antioxidant Activity

3.3. Molecular Mechanism of Anti-inflammatory of Olive Plant In Vitro

4. In Vivo and In Vitro Studies of Antidiabetic Activities of Oleuropein and Hydroxytyrosol:

4.1. In Vitro Studies of Oleuropein's Impact on Skeletal Muscle Cells

1.1. Oleuropein's Effects on Hepatocytes (In Vitro)

1.1. Effect of Oleuropein on Animal Models of Diet-Induced Diabetes (In Vivo)

1.1. Hydroxytyrosol (HT) Effects on Hepatocytes (In Vitro)

1.1. Effect of Hydroxytyrosol (HT) on In Vivo Diabetes in Rodents Caused by Alloxan

5. Conclusion

6. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hashmi, M.A.; Khan, A.; Hanif, M.; Farooq, U.; Perveen, S. Traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology of Olea europaea (olive). Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2015, 2015, 541591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilgar, R. Çanakkale ilinde zeytin yetiştiriciliği ve yaşanan sorunlar. Coğrafya Dergisi 2016, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Breton, C.; Terral, J.-F.; Pinatel, C.; Médail, F.; Bonhomme, F.; Bervillé, A. The origins of the domestication of the olive tree. Comptes rendus biologies 2009, 332, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, H.A.; Al-Bamarny, S.F. Influence of light intensity and some chemical compounds on physiological responses in olive transplants (Olea europaea L.). Pak. J. Bot 2020, 52, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scicchitano, S.; Vecchio, E.; Battaglia, A.M.; Oliverio, M.; Nardi, M.; Procopio, A.; Costanzo, F.; Biamonte, F.; Faniello, M.C. The double-edged sword of oleuropein in ovarian cancer cells: From antioxidant functions to cytotoxic effects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, B.d.F.; Otero, D.M.; Bonemann, D.H.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Jacques, A.C.; Zambiazi, R.C. Evaluation of physicochemical, bioactive composition and profile of fatty acids in leaves of different olive cultivars. Revista Ceres 2021, 68, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Navarro, M.E.; Kaparakou, E.H.; Kanakis, C.D.; Cebrián-Tarancón, C.; Alonso, G.L.; Salinas, M.R.; Tarantilis, P.A. Quantitative determination of the main phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, and toxicity of aqueous extracts of olive leaves of Greek and Spanish genotypes. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulotta, S.; Corradino, R.; Celano, M.; D’Agostino, M.; Maiuolo, J.; Oliverio, M.; Procopio, A.; Iannone, M.; Rotiroti, D.; Russo, D. Antiproliferative and antioxidant effects on breast cancer cells of oleuropein and its semisynthetic peracetylated derivatives. Food chemistry 2011, 127, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, P.; Christoforidou, N.; Lemus, C.; Argyropoulou, A.; Ioannou, K.; Vougogiannopoulou, K.; Aligiannis, N.; Paronis, E.; Gaboriaud-Kolar, N.; Tsitsilonis, O. New semi-synthetic analogs of oleuropein show improved anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2017, 137, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nediani, C.; Ruzzolini, J.; Romani, A.; Calorini, L. Oleuropein, a bioactive compound from Olea europaea L., as a potential preventive and therapeutic agent in non-communicable diseases. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulotta, S.; Oliverio, M.; Russo, D.; Procopio, A. Biological activity of oleuropein and its derivatives. In Handbook of Natural Products, KG Ramawat, JM Merillon: 2013; pp. 3605-3638.

- Ruzzolini, J.; Peppicelli, S.; Bianchini, F.; Andreucci, E.; Urciuoli, S.; Romani, A.; Tortora, K.; Caderni, G.; Nediani, C.; Calorini, L. Cancer glycolytic dependence as a new target of olive leaf extract. Cancers 2020, 12, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Villalba, R.; Larrosa, M.; Possemiers, S.; Tomás-Barberán, F.; Espín, J. Bioavailability of phenolics from an oleuropein-rich olive (Olea europaea) leaf extract and its acute effect on plasma antioxidant status: Comparison between pre-and postmenopausal women. European journal of nutrition 2014, 53, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-García, B.; Verardo, V.; León, L.; De la Rosa, R.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M. GC-QTOF-MS as valuable tool to evaluate the influence of cultivar and sample time on olive leaves triterpenic components. Food Research International 2019, 115, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Santiago, M.; Fonollá, J.; Lopez-Huertas, E. Human absorption of a supplement containing purified hydroxytyrosol, a natural antioxidant from olive oil, and evidence for its transient association with low-density lipoproteins. Pharmacological Research 2010, 61, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torić, J.; Barbarić, M.; Brala, J. Hydroxytyrosol, Tyrosol and Derivatives and Their Potential Effects on Human Health. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 24, E2001–E2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Z.K.; Elamin, M.H.; Omer, S.A.; Daghestani, M.H.; Al-Olayan, E.S.; Elobeid, M.A.; Virk, P. Oleuropein induces apoptosis via the p53 pathway in breast cancer cells. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2013, 14, 6739–6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ahn, K.S.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Wang, H.; Shen, H.; Arfuso, F.; Chinnathambi, A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Chang, Y.; Sethi, G. Oleuropein induces apoptosis via abrogating NF-κB activation cascade in estrogen receptor–negative breast cancer cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2019, 120, 4504–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messeha, S.S.; Zarmouh, N.O.; Asiri, A.; Soliman, K.F. Gene expression alterations associated with oleuropein-induced antiproliferative effects and S-phase cell cycle arrest in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.M.; Chai, E.Q.; Cai, H.Y.; Miao, G.Y.; Ma, W. Oleuropein induces apoptosis via activation of caspases and suppression of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway in HepG2 human hepatoma cell line. Molecular Medicine Reports 2015, 11, 4617–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulieris, E.N. The olive leaf extract oleuropein exerts protective effects against oxidant-induced cell death, concurrently displaying pro-oxidant activity in human hepatocarcinoma cells. Redox report 2016, 21, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, I.O.; Al-Gayyar, M.M. Oleuropein potentiates anti-tumor activity of cisplatin against HepG2 through affecting proNGF/NGF balance. Life Sciences 2018, 198, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goya, L.; Mateos, R.; Bravo, L. Effect of the olive oil phenol hydroxytyrosol on human hepatoma HepG2 cells: Protection against oxidative stress induced by tert-butylhydroperoxide. European Journal of Nutrition 2007, 46, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.A.; Ramos, S.; Granado-Serrano, A.B.; Rodríguez-Ramiro, I.; Trujillo, M.; Bravo, L.; Goya, L. Hydroxytyrosol induces antioxidant/detoxificant enzymes and Nrf2 translocation via extracellular regulated kinases and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B pathways in HepG2 cells. Molecular nutrition & food research 2010, 54, 956–966. [Google Scholar]

- Tutino, V.; Caruso, M.G.; Messa, C.; Perri, E.; Notarnicola, M. Antiproliferative, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of hydroxytyrosol on human hepatoma HepG2 and Hep3B cell lines. Anticancer research 2012, 32, 5371–5377. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, E.; Davalos, A.; Nicod, N.; Visioli, F. Hydroxytyrosol attenuates tunicamycin-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in human hepatocarcinoma cells. Molecular nutrition & food research 2014, 58, 954–962. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, D.; Pan, S.; Wu, Y.; Pan, H.; Xu, D. Hydroxytyrosol, a natural molecule from olive oil, suppresses the growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells via inactivating AKT and nuclear factor-kappa B pathways. Cancer letters 2014, 347, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.-H.; Liao, W.-C.; Lin, R.-A.; Chen, I.-S.; Wang, J.-L.; Chien, J.-M.; Kuo, C.-C.; Hao, L.-J.; Chou, C.-T.; Jan, C.-R. Hydroxytyrosol [2-(3, 4-dihydroxyphenyl)-ethanol], a natural phenolic compound found in the olive, alters Ca2+ signaling and viability in human HepG2 hepatoma cells. Journal of Physiology Investigation 2022, 65, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serreli, G.; Deiana, M. Extra virgin olive oil polyphenols: Modulation of cellular pathways related to oxidant species and inflammation in aging. Cells 2020, 9, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsour, E.H.; Kumar, M.G.; Kalen, A.L.; Goswami, M.; Buettner, G.R.; Goswami, P.C. MnSOD activity regulates hydroxytyrosol-induced extension of chronological lifespan. Age 2012, 34, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.B.; Rizvi, S.I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2009, 2, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuelo, A.; Gilbert-Lopez, B.; Pacheco-Linan, P.; Martínez-Lara, E.; Siles, E.; Miranda-Vizuete, A. Tyrosol, a main phenol present in extra virgin olive oil, increases lifespan and stress resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mechanisms of ageing and development 2012, 133, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Hou, C.; Yang, Z.; Li, C.; Jia, L.; Liu, J.; Tang, Y.; Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Long, J. Hydroxytyrosol mildly improve cognitive function independent of APP processing in APP/PS1 mice. Molecular nutrition & food research 2016, 60, 2331–2342. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Hou, C.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Guo, J.; Huo, C.; Wang, M.; Miao, Y.; Liu, J. Oleuropein improves mitochondrial function to attenuate oxidative stress by activating the Nrf2 pathway in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neuropharmacology 2017, 113, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Alarcon, S.A.; Valenzuela, R.; Valenzuela, A.; Videla, L.A. Liver protective effects of extra virgin olive oil: Interaction between its chemical composition and the cell-signaling pathways involved in protection. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Immune, Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders) 2018, 18, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.M.U.; Luo, L.; Namani, A.; Wang, X.J.; Tang, X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: Pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular basis of disease 2017, 1863, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fki, I.; Sayadi, S.; Mahmoudi, A.; Daoued, I.; Marrekchi, R.; Ghorbel, H. Comparative study on beneficial effects of hydroxytyrosol-and oleuropein-rich olive leaf extracts on high-fat diet-induced lipid metabolism disturbance and liver injury in rats. BioMed Research International 2020, 2020, 1315202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luccarini, I.; Dami, T.E.; Grossi, C.; Rigacci, S.; Stefani, M.; Casamenti, F. Oleuropein aglycone counteracts Aβ42 toxicity in the rat brain. Neuroscience Letters 2014, 558, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diomede, L.; Rigacci, S.; Romeo, M.; Stefani, M.; Salmona, M. Oleuropein aglycone protects transgenic C. elegans strains expressing Aβ42 by reducing plaque load and motor deficit. PLoS one 2013, 8, e58893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luccarini, I.; Grossi, C.; Rigacci, S.; Coppi, E.; Pugliese, A.M.; Pantano, D.; la Marca, G.; Dami, T.E.; Berti, A.; Stefani, M. Oleuropein aglycone protects against pyroglutamylated-3 amyloid-ß toxicity: biochemical, epigenetic and functional correlates. Neurobiology of aging 2015, 36, 648–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, D.; Luccarini, I.; Nardiello, P.; Servili, M.; Stefani, M.; Casamenti, F. Oleuropein aglycone and polyphenols from olive mill waste water ameliorate cognitive deficits and neuropathology. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2017, 83, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardiello, P.; Pantano, D.; Lapucci, A.; Stefani, M.; Casamenti, F. Diet supplementation with hydroxytyrosol ameliorates brain pathology and restores cognitive functions in a mouse model of amyloid-β deposition. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2018, 63, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress and cancer: have we moved forward? Biochemical Journal 2007, 401, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ďuračková, Z. Some current insights into oxidative stress. Physiological research 2010, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, K.-h.; Tian, J.-h.; Guan, Q.-l.; Yao, N.; Cao, N.; Mi, D.-h.; Wu, J.; Ma, B.; Yang, S.-h. Efficacy of antioxidant vitamins and selenium supplement in prostate cancer prevention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition and cancer 2010, 62, 719–727. [Google Scholar]

- Bendini, A.; Cerretani, L.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Lercker, G. Phenolic molecules in virgin olive oils: a survey of their sensory properties, health effects, antioxidant activity and analytical methods. An overview of the last decade. Molecules 2007, 12, 1679–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servili, M.; Montedoro, G. Contribution of phenolic compounds to virgin olive oil quality. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2002, 104, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carluccio, M.A.; Massaro, M.; Scoditti, E.; De Caterina, R. Vasculoprotective potential of olive oil components. Molecular nutrition & food research 2007, 51, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Cicerale, S.; Lucas, L.; Keast, R. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory phenolic activities in extra virgin olive oil. Current opinion in biotechnology 2012, 23, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicerale, S.; Lucas, L.; Keast, R. Biological activities of phenolic compounds present in virgin olive oil. International journal of molecular sciences 2010, 11, 458–479. [Google Scholar]

- Visioli, F.; Poli, A.; Gall, C. Antioxidant and other biological activities of phenols from olives and olive oil. Medicinal research reviews 2002, 22, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, L.; Russell, A.; Keast, R. Molecular mechanisms of inflammation. Anti-inflammatory benefits of virgin olive oil and the phenolic compound oleocanthal. Current pharmaceutical design 2011, 17, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visioli, F.; Bellomo, G.; Galli, C. Free radical-scavenging properties of olive oil polyphenols. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 1998, 247, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouka, P.; Priftis, A.; Stagos, D.; Angelis, A.; Stathopoulos, P.; Xinos, N.; Skaltsounis, A.-L.; Mamoulakis, C.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Spandidos, D.A. Assessment of the antioxidant activity of an olive oil total polyphenolic fraction and hydroxytyrosol from a Greek Olea europea variety in endothelial cells and myoblasts. International journal of molecular medicine 2017, 40, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Liew, W.-P.-P.; Sulaiman Rahman, H. Antioxidant and oxidative stress: a mutual interplay in age-related diseases. Frontiers in pharmacology 2018, 9, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. The Nrf2 regulatory network provides an interface between redox and intermediary metabolism. Trends in biochemical sciences 2014, 39, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadrich, F.; Garcia, M.; Maalej, A.; Moldes, M.; Isoda, H.; Feve, B.; Sayadi, S. Oleuropein activated AMPK and induced insulin sensitivity in C2C12 muscle cells. Life Sciences 2016, 151, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Tsukahara, C.; Ikeda, N.; Sone, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Ichi, I.; Koike, T.; Aoki, Y. Oleuropein improves insulin resistance in skeletal muscle by promoting the translocation of GLUT4. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 2017, 61, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikusato, M.; Muroi, H.; Uwabe, Y.; Furukawa, K.; Toyomizu, M. Oleuropein induces mitochondrial biogenesis and decreases reactive oxygen species generation in cultured avian muscle cells, possibly via an up-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α. Animal Science Journal 2016, 87, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, W.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, Y.K.; Choi, J.E.; Hong, S.W.; Song, M.J.; Bae, S.H.; Park, T.; Um, S.-J.; Yoon, S.K. Oleuropein reduces free fatty acid-induced lipogenesis via lowered extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation in hepatocytes. Nutrition Research 2012, 32, 778–786. [Google Scholar]

- Vergani, L.; Vecchione, G.; Baldini, F.; Grasselli, E.; Voci, A.; Portincasa, P.; Ferrari, P.F.; Aliakbarian, B.; Casazza, A.A.; Perego, P. Polyphenolic extract attenuates fatty acid-induced steatosis and oxidative stress in hepatic and endothelial cells. European journal of nutrition 2018, 57, 1793–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliou, F.; Andreadou, I.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Lazou, A.; Xepapadaki, E.; Vallianou, I.; Lambrinidis, G.; Mikros, E.; Marselos, M.; Skaltsounis, A.-L. The olive constituent oleuropein, as a PPARα agonist, markedly reduces serum triglycerides. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 2018, 59, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, S.J.; Porcu, C.; Tarantino, G.; Amicarelli, F.; Balsano, C. Oleuropein overrides liver damage in steatotic mice. Journal of Functional Foods 2020, 65, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oi-Kano, Y.; Kawada, T.; Watanabe, T.; Koyama, F.; Watanabe, K.; Senbongi, R.; Iwai, K. Oleuropein, a phenolic compound in extra virgin olive oil, increases uncoupling protein 1 content in brown adipose tissue and enhances noradrenaline and adrenaline secretions in rats. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology 2008, 54, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemai, H.; Bouaziz, M.; Fki, I.; El Feki, A.; Sayadi, S. Hypolipidimic and antioxidant activities of oleuropein and its hydrolysis derivative-rich extracts from Chemlali olive leaves. Chemico-biological interactions 2008, 176, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, Y.; Park, T. Hepatoprotective effect of oleuropein in mice: mechanisms uncovered by gene expression profiling. Biotechnology journal 2010, 5, 950–960. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Choi, Y.; Um, S.-J.; Yoon, S.K.; Park, T. Oleuropein attenuates hepatic steatosis induced by high-fat diet in mice. Journal of hepatology 2011, 54, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.; Liu, L.; Pan, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, D.; Kang, K.; Wang, J.; Sun, B.; Sun, X.; Jiang, H. Protective effects of hydroxytyrosol on liver ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2013, 57, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priore, P.; Siculella, L.; Gnoni, G.V. Extra virgin olive oil phenols down-regulate lipid synthesis in primary-cultured rat-hepatocytes. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2014, 25, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Senent, F.; de Roos, B.; Duthie, G.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G. Inhibitory and synergistic effects of natural olive phenols on human platelet aggregation and lipid peroxidation of microsomes from vitamin E-deficient rats. European Journal of Nutrition 2015, 54, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G.; Rubio-Senent, F.; Gómez-Carretero, A.; Maya, I.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.; Duthie, G.G.; de Roos, B. Selenium and sulphur derivatives of hydroxytyrosol: inhibition of lipid peroxidation in liver microsomes of vitamin E-deficient rats. European journal of nutrition 2019, 58, 1847–1851. [Google Scholar]

- Hamden, K.; Allouche, N.; Damak, M.; Elfeki, A. Hypoglycemic and antioxidant effects of phenolic extracts and purified hydroxytyrosol from olive mill waste in vitro and in rats. Chemico-biological interactions 2009, 180, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemai, H.; El Feki, A.; Sayadi, S. Antidiabetic and antioxidant effects of hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein from olive leaves in alloxan-diabetic rats. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2009, 57, 8798–8804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Cell | Treatment of Cells | Conclusions | References |

| C2C12 myotubes n = 3 | With OLE the cells were exposed at a concentration of 200 µM or 400 µM for 30 minutes, followed by exposure to 400 µM H₂O₂ for 24 h. | Increased glucose consumption and insulin sensitivity, reduced H₂O₂-induced ROS, and elevated levels of phosphorylated AMPK, ACC, and ERK proteins | [57] |

| C2C12 myotubes n = 3 | With OLE the cells were exposed at a concentration of 1 µM, 10 µM, or 100 µM for 30 minutes to 24 hours, followed by exposure to 250 µM palmitic acid for a period of 24 h. | Increased glucose uptake, elevated GLUT4 mRNA expression, and higher levels of phosphorylated AMPK (p-AMPK) protein. | [58] |

| Male chicks (Ross strain, Gallus Domesticus) n = 4–6 | OLE was administered orally at 5 mg/kg body weight per day for 15 days | Increased mRNA levels of avUCP, PGC1-α, TFAM, NRF1, ATP5a1, and SIRT1, elevated cytochrome c oxidase activity, and reduced mitochondrial superoxide activity, indicating decreased ROS production | [59] |

| Cell Types | Treatment of cells | Conclusions | References |

| HepG2 and FL83B hepatocytes n = 3 | With OLE the cells were exposed at a concentration of 10 and 50 µM for 24 hours, followed by exposure to 0.5 mmol/L of a 2:1 oleic acid–palmitic acid mixture. | Lipid growth and size of droplet were decreased, TIP47 and ADRP mRNA levels were reduced, FFA-induced p-ERK protein levels were lowered, and p-JNK and p-Akt protein levels were unchanged/modulated. | [60] |

| FaO cells n = 3 | With OLE the cells were exposed with at a concentration of 50 µg/mL for 24 hours, followed by exposure to 0.75 mM of a 2:1 oleate–palmitate mixture. | Triglyceride accumulation was decreased, and lipid peroxidation/oxidative stress was reduced. | [61] |

| HepG2 hepatocytes n = 6 | Cells were treated with OLE at 10 µM for 2 and 24 hours | OLE acts as a PPARα ligand, increasing PPARα mRNA and protein levels, as well as upregulating ACOX1, CYP4A14, Lipin 1, and ACOT4 mRNA levels. | [62] |

| HepG2 hepatocytes n= 5 | ells were treated with OLE at 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µM for 24 hours in a steatosis model using 0.5 mM palmitic acid/oleic acid (PA/OA). | Lipid accumulation was decreased at concentrations of 50, 100, and 200 µM. | [63] |

| Cell Types | Treatment | Findings | References |

| Male Sprague–Dawley rats n = 6 | OLE was administered at 1, 2, or 4 mg/kg, or provided as a 0.1%, 0.2%, or 0.4% dietary supplement for 28 days in a high-fat diet containing 30% shortening. Additionally, cells were treated with OLE at 10–50 mmol/L for 10 minutes |

Body weight and weight gain, as well as epididymal and perirenal fat pad weights, were reduced. Plasma TG, TC, FFA, and leptin levels were lowered, while IBAT UCP-1 protein levels and urine and plasma norepinephrine and epinephrine levels were increased. | [64] |

| Male Wistar rats n = 10 | OLE was administered at 3 mg/kg body weight for a period of 16 weeks in a high-cholesterol diet containing 1% cholesterol and 0.25% bile salts. | Liver-to-body weight ratio was decreased, along with reduced plasma levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and LDL-C. Plasma HDL-C levels were increased, as were SOD and CAT activities and overall antioxidant capacity measured by the TEAC assay. Lipid peroxidation was reduced, and OLE prohibited cardiac muscle hypertrophy, aortic wall lesions, and hepatic steatosis. | [65] |

| Male C57BL/6N mice n = 8 |

Oleuropein was provided as a 0.03% (w/w) dietary supplement for a period of 10 weeks. | Oxidative stress- and pro-inflammatory–related hepatic genes were downregulated, hepatic genes involved in lipid peroxidation product detoxification were reduced, and hepatic mRNA levels of fatty acid absorbed and transporter of genes were decreased. | [66] |

| Male C57BL/6N mice n = 8 | OLE was administered ad libitum at 0.03% (w/w) for 10 weeks. | Body weight gain and liver weight were reduced, along with decreased plasma levels of AST and ALT. Plasma and liver levels of free fatty acids (FFA), total cholesterol (TC), and triglycerides (TG) were lowered. Hepatic mRNA levels of LXR, PPARγ2, LPL, aP2, Cyc-D, E2F1, CTSS, SFRP5, and DKK2 were decreased, and liver p-ERK protein levels were reduced, while β-catenin protein levels were increased. | [67] |

| Cell Type | Hydroxytyrosol Concentration/Duration | Effect | References |

| Mouse hepatocytes | 100 µM for 4 hrs. (hypoxia); followed by reoxygenation | Cell apoptosis decreased, while hepatocyte viability and the activities of SOD1, SOD2, and CAT increased. | [68] |

| Rat hepatocytes | 25 µM for 2 h | Lipid synthesis, including fatty acids, cholesterol, and triglycerides was reduced, accompanied by decreased expression of ACC, diacylglycerol acyltransferase, and HMG-CoA reductase, while AMPK and ACC phosphorylation were increased. | [69] |

| Vit. E-deficient rat liver microsomes | 0.05–2 mM for 30 min | Lipid peroxidation and TBARS levels were decreased. | [70] |

| microsomes from vitamin E-deprived rats | 0.05–0.25 mM for 20 min | Lipid peroxidation, as indicated by TBARS levels, was reduced. | [71] |

| Model of Study |

Hydroxytyrosol Concentration/ Duration |

Effects | References |

| Alloxan-induced diabetic male Wistar rats | 20 mg/kg for 2 months; intraperitoneal injection | decreased blood glucose levels, reduced liver TBARS, bilirubin, and fatty cysts; increased hepatic glycogen and HDL, enhanced antioxidant enzyme activities such as SOD, CAT, and GPX in the liver and kidney; and diminished β-cell damage | [72] |

| Alloxan-induced diabetic male Wistar rats | 8 or 16 mg/kg orally for 4 weeks; | Reduced blood glucose levels, decrease TC and hepatic oxidative damage (TBARS), increased hepatic glycogen and antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT) | [73] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).