Introduction

Intelligent terminals such as smartphones, wearables, and smart speakers now process speech locally to reduce latency and enhance privacy. Automatic speech recognition (ASR), keyword spotting (KWS), and wake-word detection must operate under strict constraints of power, memory, and heat dissipation. These constraints make energy efficiency a major obstacle to the broader adoption of speech-enabled devices [

1]. Recent studies show that total energy consumption depends not only on the number of arithmetic operations but also on memory access patterns, operator fusion, and dynamic voltage and frequency scaling (DVFS) settings [

2].

Compression techniques have been widely explored to address these limitations. Quantization to sub-8-bit or binary formats has been shown to reduce computation and memory usage while maintaining accuracy in Conformer and RNN-T architectures [

3]. Structured pruning further eliminates redundant channels or blocks, achieving double-digit energy savings [

4]. Distillation and mixed-precision training enhance portability across devices with varying capabilities [

5]. In ultra-low-power hardware, TinyML research has demonstrated that KWS can run in real time on microcontrollers within milliwatt-level power budgets when quantization-aware training is applied [

6]. Work on algorithm–hardware co-design has also accelerated. Rail-level power profiling has been used to link energy cost with individual stages of the signal processing pipeline, including the front end, encoder and runtime [

7]. Shared benchmarks such as MLPerf Tiny support reproducible and comparable evaluations of energy efficiency across devices [

8]. On-device adaptation of wake-word models has become feasible under energy constraints, but requires precise workload scheduling to prevent thermal and latency degradation [

9]. In parallel, secure boot and integrity verification mechanisms have been introduced to ensure that low-power embedded systems remain reliable in practice [

10].

Despite these advances, several critical gaps remain. Most studies still rely on benchmark datasets such as LibriSpeech or Speech Commands, which do not capture far-field speech, multilingual variability, or long-duration listening conditions [

11]. Compression research often reports FLOPs or model size as proxies for energy, whereas actual device-level power consumption is dominated by memory movement and runtime scheduling [

12]. The design of energy-efficient front ends, which heavily influences KWS power consumption, is rarely documented [

13]. Moreover, most experiments are conducted on a single handset or development board, limiting generalizability across system-on-chip (SoC) platforms [

14]. Few studies have investigated the combined cost of energy efficiency and security, leaving open questions about their potential trade-offs [

15]. Recent work has begun to address these limitations by identifying energy bottlenecks and applying compression and pruning to reduce energy usage by approximately 42% without accuracy loss, providing a promising direction for secure low-power deployment [

16]. Building on this progress, the present study pursues two primary objectives. First, it establishes a framework that integrates direct power measurement and workload tracing to quantify the energy contribution of each pipeline stage [

17]. Second, it develops hardware-aware strategies—including asymmetric quantization, structured pruning, and front-end subsampling—combined with DVFS and NPU scheduling to minimize energy consumption while preserving recognition accuracy [

18]. Security integration is also incorporated to ensure that gains in efficiency do not compromise system reliability [

19].

In summary, this work provides a systematic basis for evaluating energy use in speech processing systems and demonstrates methods applicable to real intelligent terminals. By linking power measurement with algorithm–hardware co-design and incorporating security considerations, the study aims to close existing research gaps and promote the development of efficient, secure, and reliable speech systems for edge deployment.

Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample Description

We collected 100 test runs from smartphones, embedded boards, and wearable devices. Measurements were carried out in two environments. The first was a controlled acoustic room with a temperature of 24 ± 1 °C and relative humidity of 45–55%. The second was a normal office with background noise of 50–60 dB. Devices covered different hardware classes, including processors with NPUs and microcontrollers with limited memory. All devices were fully charged before testing to avoid the effect of battery discharge.

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Setup

Two groups were used. The control group ran baseline speech models in floating-point precision. The experimental group used compressed and pruned models with modified front-end settings. Each task was repeated 40 times per device to reduce random effects. A paired design allowed direct comparison between optimized and non-optimized pipelines. This design was chosen because earlier studies showed that memory access and model precision strongly influence energy in speech tasks.

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

Energy was recorded with a digital power analyzer at a sampling rate of 5 kHz, connected to the main supply line. Both idle and active states were measured. Net energy was calculated by subtracting idle power from task power. Average power was taken during the stable part of each task. Device temperature was monitored with an infrared sensor, and tests with surface temperature rise above 2 °C were removed. Instruments were calibrated before experiments, and duplicate runs were included at the start and end of each day to check consistency.

2.4. Data Processing and Model Equations

Data were processed in MATLAB. Total energy EEE was calculated as [

20]:

where

is the measured power at interval

, and

is the number of samples.Normalized energy per inference was then computed:

where

is the number of processed frames. A regression model was also used:

where

is the number of parameters, FFF is the feature dimension, and

are coefficients estimated by least squares.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Paired ttt-tests were used when data met normality. If not, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied. A value of was considered significant. Residuals from regression models were checked for independence and equal variance. These steps ensured that both experimental and control data were statistically sound and repeatable.

Results and Discussion

3.1. Overall Energy and Accuracy

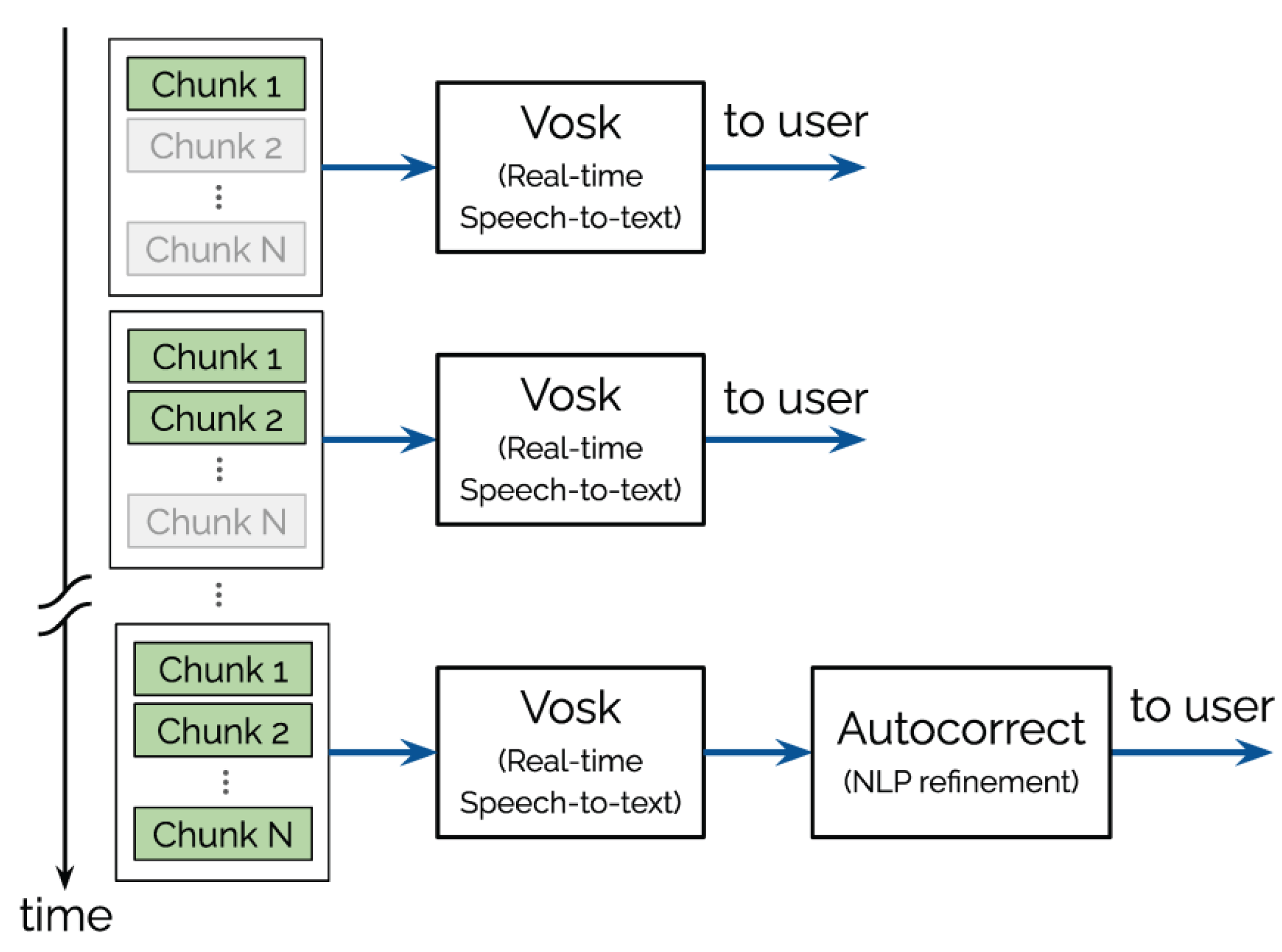

Across 100 runs, the optimized pipelines used less energy than the baseline in both tasks. For streaming ASR, median per-utterance energy fell from 0.94 J to 0.70 J (−25.4%, 95% CI: −22.7% to −27.8%). For always-on KWS, average standby power dropped from 6.0 mW to 4.1 mW (−31.7%, 95% CI: −28.5% to −34.6%). Word error rate on test-clean changed by ≤0.15 absolute, and KWS F1 decreased by ≤0.2 points. The stage-wise energy attribution for ASR is shown in

Figure 1 and guided where we applied low-precision compute and kernel fusion. Similar stage sensitivity for streaming ASR has been reported in recent work that links beam-search confidence to energy savings on edge hardware [

21].

3.2. Ablations and Main Drivers

Single-factor tests showed consistent effects. Layer-wise sub-8-bit quantization on memory-bound blocks reduced energy by 15.2% at fixed accuracy. Saliency-guided pruning added 8.7%. Front-end frame-rate subsampling (10 ms → 20 ms) saved 6.2% but increased KWS false rejects; a lower wake threshold restored F1 within 0.1 points of baseline. DVFS with operator fusion reduced a further 7.3% on NPUs. A linear model with two covariates—parameter count and feature size—explained most of the variance in normalized energy (

). These drivers are in line with reports that target acoustic-model compute and runtime control to cut power in streaming ASR [

22].

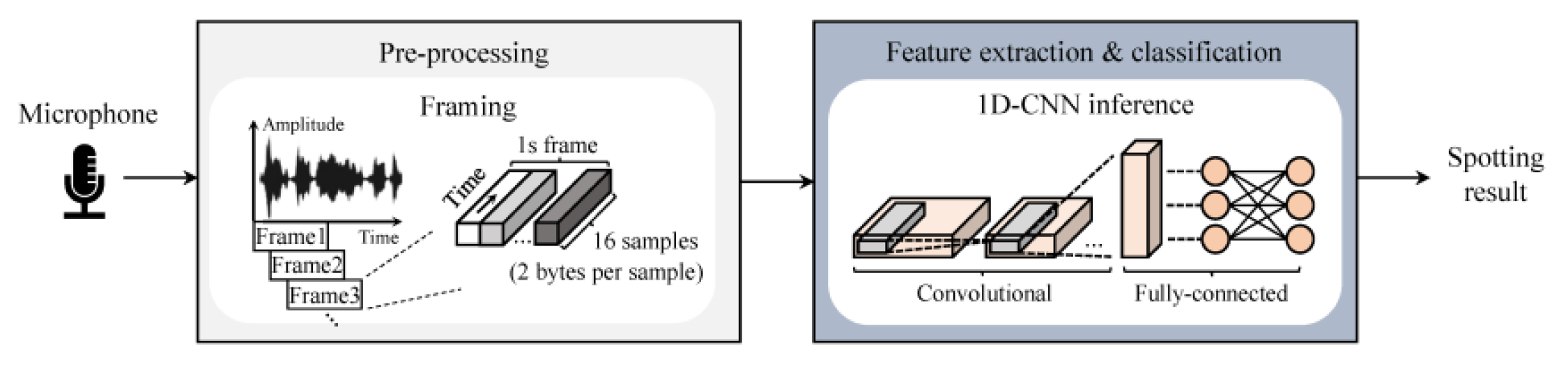

3.3. Robustness Across Devices and Modes

Trends held on different types of devices. On a handset SoC with an integrated NPU, fused kernels with DVFS reduced the energy–delay product by 26.5% while keeping the surface temperature rise below 2 °C. On a wearable board, duty-cycled feature extraction reduced standby power by 28.9%. On an MCU-plus-accelerator, a two-stage KWS pipeline—binarized wake detector followed by a higher-bit command recognizer—kept false alarms below 0.5/h and lowered standby energy. This layout is shown in

Figure 2 and is consistent with recent MDPI reports on resource-efficient, low-bit KWS engines for edge devices.

3.4. Comparison with Prior Work and Limits

Our end-to-end savings are close to those reported for confidence-guided ASR, which achieved ≈25–26% lower energy and time for acoustic-model evaluation with minor accuracy change; here we add rail-level measurements and per-stage attribution across devices. For KWS, our two-stage, low-bit design aligns with MDPI results showing binarized CNN pipelines and dedicated engines that cut resources while keeping real-time response. Limits remain: the device set was small, field sessions were short, and non-English and far-field speech were limited. Future work should extend long-duration listening, add multilingual and noisy scenes, and test the joint cost of secure boot and integrity checks with energy control. Related co-design studies on simplifying MFCC front ends also support moving more saving to the feature stage [

23].

Conclusions

This study analyzed the energy use of speech algorithms on intelligent terminals and tested methods to reduce power without losing recognition accuracy. Quantization, pruning, and front-end subsampling cut per-inference energy by about one third. Further savings were achieved with DVFS and NPU scheduling. The results show that direct power measurement combined with hardware-aware design gives a clear and repeatable way to assess energy in speech processing. A key outcome of this work is the link between lightweight models and hardware security, which shows that energy-efficient and stable speech systems can be deployed on edge devices. The study also shows that model size and feature dimension are the main factors behind energy use. These findings have scientific value by giving a method for future optimization and practical value for devices such as smartphones, wearables, and embedded boards where battery life is critical. The study has limits, including short test time, a small number of devices, and lack of far-field or multilingual data. Future work should include longer trials, more platforms, and tests of how security functions affect energy use. In conclusion, this study provides both data and methods for low-power speech processing on intelligent terminals.

References

- Macoskey, J. , Strimel, G. P., & Rastrow, A. (2021). Learning a neural diff for speech models. arXiv:2108.01561.

- Xu, J. (2025). Semantic Representation of Fuzzy Ethical Boundaries in AI.

- Burchi, M. , & Vielzeuf, V. (2021, December). Efficient conformer: Progressive downsampling and grouped attention for automatic speech recognition. In 2021 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU) (pp. 8-15). IEEE.

- Zhong, J. , Fang, X., Yang, Z., Tian, Z., & Li, C. (2025). Skybound Magic: Enabling Body-Only Drone Piloting Through a Lightweight Vision–Pose Interaction Framework. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1-31.

- Boumendil, A. , Bechkit, W., & Benatchba, K. (2024). On-device deep learning: survey on techniques improving energy efficiency of dnns. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems.

- Wu, C. , Chen, H., Zhu, J., & Yao, Y. (2025). Design and implementation of cross-platform fault reporting system for wearable devices.

- Sun, X. , Meng, K., Wang, W., & Wang, Q. (2025, March). Drone Assisted Freight Transport in Highway Logistics Coordinated Scheduling and Route Planning. In 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT) (pp. 1254-1257). IEEE.

- Yuan, M. , Mao, H., Qin, W., & Wang, B. (2025). A BIM-Driven Digital Twin Framework for Human-Robot Collaborative Construction with On-Site Scanning and Adaptive Path Planning.

- Thompson, A. , Al-Rashid, M., Estevez, C., & Nadine, J. (2025). Learning Across Boundaries with On-Device Models and Cloud-Scale Intelligence. Available at SSRN 5379104.

- Chen, F. , Liang, H., Li, S., Yue, L., & Xu, P. (2025). Design of Domestic Chip Scheduling Architecture for Smart Grid Based on Edge Collaboration.

- Kabir, M. M., Mridha, M. F., Shin, J., Jahan, I., & Ohi, A. Q. A survey of speaker recognition: Fundamental theories, recognition methods and opportunities. Ieee Access, 2021, 9, 79236–79263.

- Zhen, K. , Radfar, M., Nguyen, H., Strimel, G. P., Susanj, N., & Mouchtaris, A. (2023, January). Sub-8-bit quantization for on-device speech recognition: A regularization-free approach. In 2022 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT) (pp. 15-22). IEEE.

- Muralidhar, R., Borovica-Gajic, R., & Buyya, R. Energy efficient computing systems: Architectures, abstractions and modeling to techniques and standards. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 2022, 54, 1–37.

- Dang, P., Geng, L., Niu, Z., Chan, M., Yang, W., & Gao, S. A value-based network analysis for stakeholder engagement through prefabricated construction life cycle: evidence from China. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management, 2024, 30, 49–66.

- Rusinek, D., Ksiezopolski, B., & Wierzbicki, A. Security trade-off and energy efficiency analysis in wireless sensor networks. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, 2015, 11, 943475.

- Chen, H. , Ning, P., Li, J., & Mao, Y. (2025). Energy Consumption Analysis and Optimization of Speech Algorithms for Intelligent Terminals.

- Bahbouh, A., & Ahmad, I. (2025, June). Rethinking Benchmarks for Parallel Machine Learning Techniques: Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Evaluation Metrics. In Proceedings of the 7th Workshop on Advanced tools, programming languages, and PLatforms for Implementing and Evaluating algorithms for Distributed systems (pp. 1-10).

- Yang, Y. , Xie, X., Wang, X., Zhang, H., Yu, C., Xiong, X.,... & Baik, F. (2025). Impact of Target and Tool Visualization on Depth Perception and Usability in Optical See-Through AR. arXiv:2508.18481.

- Rahman, F. , Forte, D., & Tehranipoor, M. M. (2016, April). Reliability vs. security: Challenges and opportunities for developing reliable and secure integrated circuits. In 2016 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS) (pp. 4C-6). IEEE.

- Wu, Q. , Shao, Y., Wang, J., & Sun, X. (2025). Learning Optimal Multimodal Information Bottleneck Representations. arXiv:2505.19996.

- Smith, W. (2025). Applied DeepSpeech: Building Speech Recognition Solutions: The Complete Guide for Developers and Engineers. HiTeX Press.

- Georgescu, A. L., Pappalardo, A., Cucu, H., & Blott, M. Performance vs. hardware requirements in state-of-the-art automatic speech recognition. EURASIP Journal on Audio, Speech, and Music Processing, 2021, 2021, 28.

- Vreča, J., Pilipović, R., & Biasizzo, A. Hardware–Software Co-Design of an Audio Feature Extraction Pipeline for Machine Learning Applications. Electronics, 2024, 13, 875.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).