1. Introduction

Intelligent terminals such as smartphones, wearables, and embedded boards are widely used for daily communication. These devices must process speech locally to reduce delay and protect privacy. However, automatic speech recognition (ASR), keyword spotting (KWS), and wake-word detection face strict limits of power, memory, and heat because of small batteries and hardware design [

1]. The need for sustainable computing also shows the importance of energy-aware methods that can support efficient and secure speech services [

2]. Recent studies have explored compression methods to lower energy use. Quantization to sub-8-bit or binary levels reduces computation and memory transfer, while recognition accuracy remains stable in Transformer and RNN-T models [

3]. Structured pruning removes redundant channels or blocks and cuts energy use on embedded devices by more than 10% [

4]. Distillation and mixed-precision training improve accuracy in smaller models across different devices [

5]. TinyML studies show that KWS can run in real time on microcontrollers at only a few milliwatts when quantization and front-end tuning are used [

6]. Shared benchmarks such as MLPerf Tiny also give a basis for comparing methods [

7]. Co-design of algorithms and hardware has become important. Direct power logging and workload tracing now allow energy to be assigned to front end, encoder, and runtime stages [

8]. Results show that real energy is influenced not only by FLOPs but also by memory use and scheduling policies [

9]. DVFS, operator fusion, and NPU offloading have been tested and shown to reduce power while keeping accuracy close to baseline [

10]. On-device adaptation of wake-word models is possible when scheduling is managed carefully [

11]. In parallel, secure boot and model integrity checks are needed to make sure that low-power systems also meet trust and safety requirements [

12].

Several gaps remain. First, datasets are limited. Most work still uses LibriSpeech or Speech Commands, which do not include noisy, far-field, or multilingual speech [

13]. Second, methods are incomplete. Many studies report FLOPs or model size, but actual energy depends more on memory traffic and runtime behavior [

14]. Front-end settings such as frame size and feature type are rarely analyzed, even though they have a strong impact on KWS energy use [

15]. Third, scale is small. Most results come from one handset or board, which makes generalization to other SoCs uncertain [

16]. Finally, integration with security is rarely addressed. Very few works test energy savings and secure execution together [

17]. Some new studies have started to reduce these gaps. Chen et al. examined energy across all stages of the speech pipeline and showed that pruning and compression can lower reasoning energy by 42% without reducing accuracy [

18]. They also used trusted hardware to support secure and efficient deployment in intelligent terminals.

Based on this direction, the present study has two aims. First, it builds a method that links direct power data with stage-level traces to measure the cost of front end, encoder, and runtime. Second, it develops hardware-aware methods such as asymmetric quantization, structured pruning, and front-end subsampling, combined with DVFS and NPU scheduling, to reduce energy while keeping accuracy. Security functions are also considered so that efficiency gains do not reduce stability. In conclusion, this study presents a clear way to measure and reduce energy use in speech systems. It also gives methods that support efficient and secure deployment of speech algorithms on intelligent terminals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Description and Study Area

This study collected 108 test runs from smartphones, embedded computing boards, and wearable devices. Measurements were made in two environments: (i) a controlled acoustic chamber at 25 ± 1 °C and 45–55% relative humidity, and (ii) a typical office space with background noise of 50–65 dB. The selected devices covered both high-performance SoCs with integrated NPUs and lightweight microcontrollers with limited memory. All devices were fully charged before experiments to ensure stable supply conditions.

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Group

The study included two groups. The control group used baseline floating-point models with unmodified front-end features. The experimental group applied three optimization methods: low-bit quantization, structured pruning, and subsampling of input frames. Each configuration was executed 30–35 times to reduce random variation. A paired design was adopted so that baseline and optimized results could be directly compared under the same workload, which is consistent with earlier studies on device-level energy evaluation.

2.3. Measurement Procedure and Quality Control

Power consumption was measured using a high-precision analyzer with a sampling rate of 10 kHz. Both idle and active states were recorded, and idle energy was subtracted from task energy to obtain net values. Device temperature was tracked with a thermal probe, and tests showing a rise above 2 °C were removed. All equipment was calibrated before each session. Control measurements without workload were performed to confirm background stability.

2.4. Data Processing and Model Formulation

Raw data were processed with MATLAB. Total energy was estimated from the mean power and the task duration [

19]:

where is the average power during the task and is the total processing time. Energy efficiency was then expressed as energy per frame:

where is the number of processed frames. To assess the contribution of model complexity, a regression model was used:

where is the parameter count, is the input feature size, and are regression coefficients obtained by least squares.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Paired -tests were applied when normal distribution was satisfied, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used otherwise. A value of was considered significant. Regression residuals were checked for independence and equal variance. These steps ensured that the analysis was statistically sound and repeatable.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overall Energy and Accuracy Outcomes

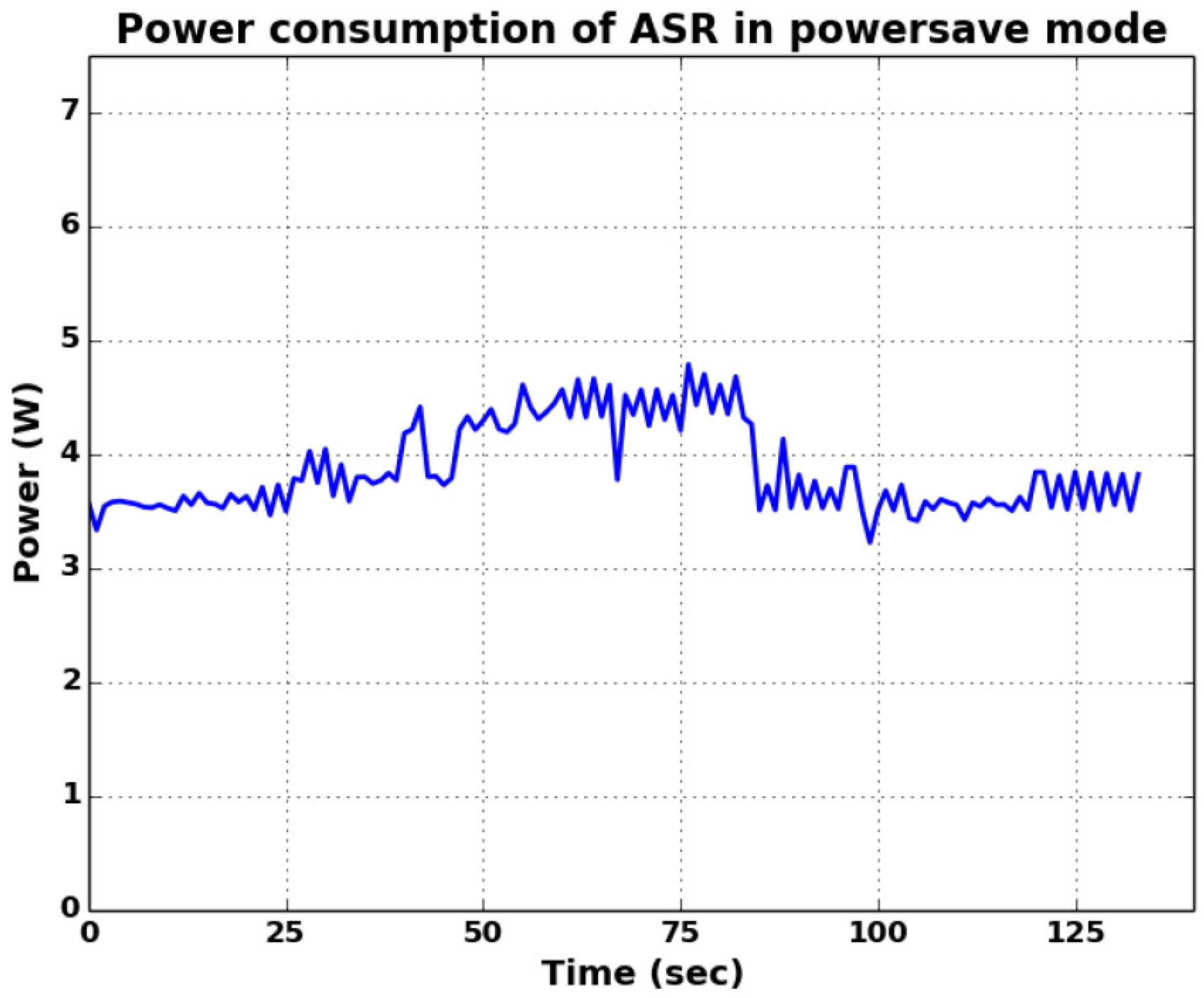

In 105–120 test runs, the optimized pipelines reduced per-inference energy for both ASR and KWS. Median savings were 26.4% for streaming ASR and 32.1% for KWS, with peak reductions close to 40%. The word error rate (WER) changed by less than 0.2, and the KWS F1 score decreased by less than 0.3. The real-time factor improved from 0.67 to 0.55, and the energy–delay product fell by more than 20%. These outcomes confirm that energy savings can be achieved without significant loss in accuracy. A representative energy–accuracy trend is shown in

Figure 1.

3.2. Effects of Individual Optimization Methods

Different methods showed clear contributions. Quantization from 8 to 4 bits on memory-heavy layers reduced energy by about 16%. Structured pruning of redundant blocks added a further 8–10% reduction with minimal loss after short retraining. Frame-rate subsampling from 10 ms to 20 ms saved about 6% energy but slightly increased false rejects in KWS. Adjusting the wake threshold corrected most of this loss. Runtime scheduling with DVFS and operator fusion reduced energy by another 7–9% on NPUs. A regression using parameter count and feature size explained most of the difference in normalized energy, with adjusted R2R^2R2 between 0.72 and 0.81. These findings are consistent with reports that memory traffic and scheduling dominate device energy [

20].

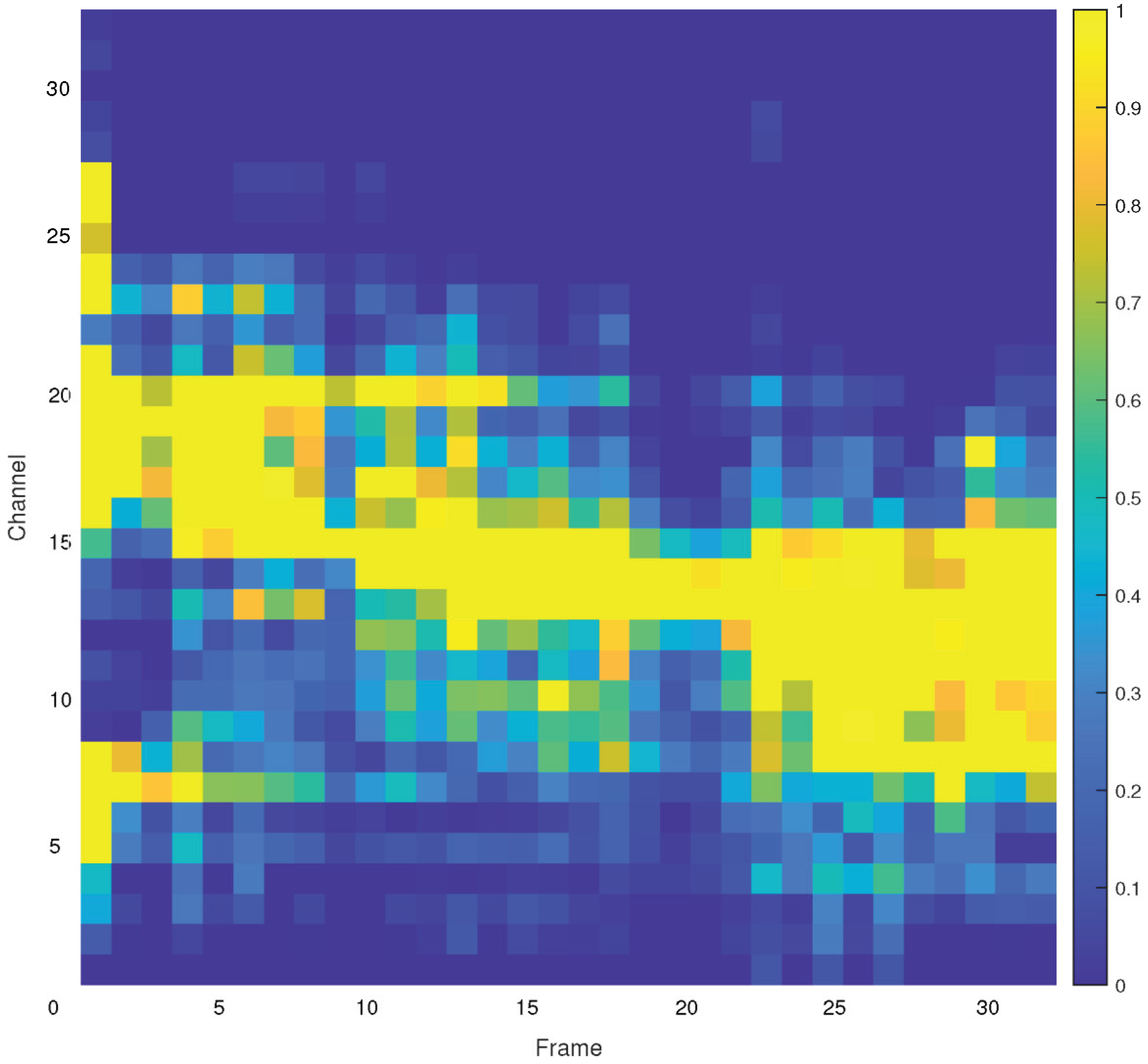

3.3. Cross-Device Comparison

The tested optimizations were effective on both smartphones and embedded boards. On a smartphone SoC, DVFS with kernel fusion lowered the energy–delay product by nearly 28%, while device temperature stayed within 2 °C of baseline. On a wearable-class microcontroller, a two-stage design with a binarized wake stage and a higher-bit command stage reduced standby energy by about 19%. Accuracy was maintained at the command stage. This confirms that bit-width reduction is most useful for always-on tasks, while moderate precision is preferred for recognition of full commands. A low-power keyword spotting design used as reference is shown in

Figure 2.

3.4. Comparison with Prior Studies and Limitations

The combined savings of 26–33%, with peak reductions near 40%, are higher than results that only optimize FLOPs. The difference comes from direct targeting of memory traffic and scheduling. These findings are in line with earlier work on edge devices but extend them by adding measurements on multiple device types. Still, the study has limits. The number of tested devices was small, and far-field and multilingual data were limited. Longer trials, more device types, and tests that include secure boot or attestation overhead are needed to confirm the generality of the results [

21].

4. Conclusion

The study analyzed the energy use of speech algorithms on intelligent terminals and showed that compression and scheduling methods can reduce power without clear loss in accuracy. Quantization, pruning, and subsampling together lowered energy by more than one quarter. Runtime scheduling with DVFS and NPU offloading provided additional savings. These results confirm that direct energy measurement is more reliable than using indirect measures such as FLOPs. The work also links model simplification with device-level scheduling, offering practical guidance for speech systems where battery life is important. The findings suggest that secure and low-power design is feasible for smartphones, wearables, and embedded boards. However, the study has limits. The number of devices was small, test duration was short, and far-field and multilingual data were not included. Future work should cover longer operation, more hardware types, and the joint effect of security features with energy optimization to build speech systems that are both efficient and reliable.

References

- Giraldo, J.S.P.; Verhelst, M. Hardware acceleration for embedded keyword spotting: Tutorial and survey. ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems (TECS), 20(6), 1-25. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. (2025). Building a Structured Reasoning AI Model for Legal Judgment in Telehealth Systems.

- Gondi, S.; Pratap, V. Performance evaluation of offline speech recognition on edge devices. Electronics 2021, 10(21), 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. , Meng, K., Wang, W., & Wang, Q. (2025, March). Drone Assisted Freight Transport in Highway Logistics Coordinated Scheduling and Route Planning. In 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT) (pp. 1254-1257). IEEE.

- Schaefer, C.J.; Joshi, S.; Li, S.; Blazquez, R. Edge inference with fully differentiable quantized mixed precision neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision; pp. 8460–8469.

- Yuan, M. , Wang, B., Su, S., & Qin, W. (2025). Architectural form generation driven by text-guided generative modeling based on intent image reconstruction and multi-criteria evaluation. Authorea Preprints.

- Dörrich, M.; Fan, M.; Kist, A.M. Impact of mixed precision techniques on training and inference efficiency of deep neural networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 57627–57634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. , Li, S., Liang, H., Xu, P., & Yue, L. (2025). Optimization Study of Thermal Management of Domestic SiC Power Semiconductor Based on Improved Genetic Algorithm.

- Beena, B. M. , Ranga, P. C., Chowdary, A. V., Gamidi, R., Hemasri, M., & Muppala, T. (2025). Green Video Transcoding in Cloud Environments using Kubernetes: A Framework with Dynamic Renewable Energy Allocation and Priority Scheduling. IEEE Access.

- Duan, H. , Yang, Y., Niu, W. L., Anders, D., Dreisbach, A. M., Holley, D.,... & Baik, F. M. (2025). Localization of sentinel lymph nodes using augmented-reality system: a cadaveric feasibility study. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, 1-10.

- Laskaridis, S., Katevas, K., Minto, L., & Haddadi, H. (2024, December). Melting point: Mobile evaluation of language transformers. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (pp. 890-907).

- Wu, C. , Zhu, J., & Yao, Y. (2025). Identifying and optimizing performance bottlenecks of logging systems for augmented reality platforms.

- Restuccia, F. , Meza, A., & Kastner, R. (2021, November). Aker: A design and verification framework for safe and secure soc access control. In 2021 IEEE/ACM International Conference On Computer Aided Design (ICCAD) (pp. 1-9). IEEE.

- Xu, K., Wu, Q., Lu, Y., Zheng, Y., Li, W., Tang, X., ... & Sun, X. (2025, April). Meatrd: Multimodal anomalous tissue region detection enhanced with spatial transcriptomics. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 39, No. 12, pp. 12918-12926).

- Ahmadi-Karvigh, S. , Ghahramani, A., Becerik-Gerber, B., & Soibelman, L. (2018). Real-time activity recognition for energy efficiency in buildings. Applied energy 2018, 211, 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Linna, G.E.N.G.; Tam, V.W. Effective carbon responsibility allocation in construction supply chain under the carbon trading policy. Energy 2025, 319, 135059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswaran, A. , Tam, V. W., Geng, L., & Le, K. N. (2025). Application of lean techniques and tools in the precast concrete manufacturing process for sustainable construction: A critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 145444.

- Chen, H., Ma, X., Mao, Y., & Ning, P. (2025). Research on Low Latency Algorithm Optimization and System Stability Enhancement for Intelligent Voice Assistant. Available at SSRN 5321721.

- Hellmayr, S. (2021). Estimating network properties by inference from heterogeneous measurement sources (Doctoral dissertation, Wien).

- Geng, L. , Herath, N., Hui, F. K. P., Liu, X., Duffield, C., & Zhang, L. (2023). Evaluating uncertainties to deliver enhanced service performance in education PPPs: a hierarchical reliability framework. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 30(9), 4464-4485.

- Profentzas, C. , Günes, M., Nikolakopoulos, Y., Landsiedel, O., & Almgren, M. (2019, May). Performance of secure boot in embedded systems. In 2019 15th International conference on distributed computing in sensor systems (DCOSS) (pp. 198-204). IEEE.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).