1. Introduction

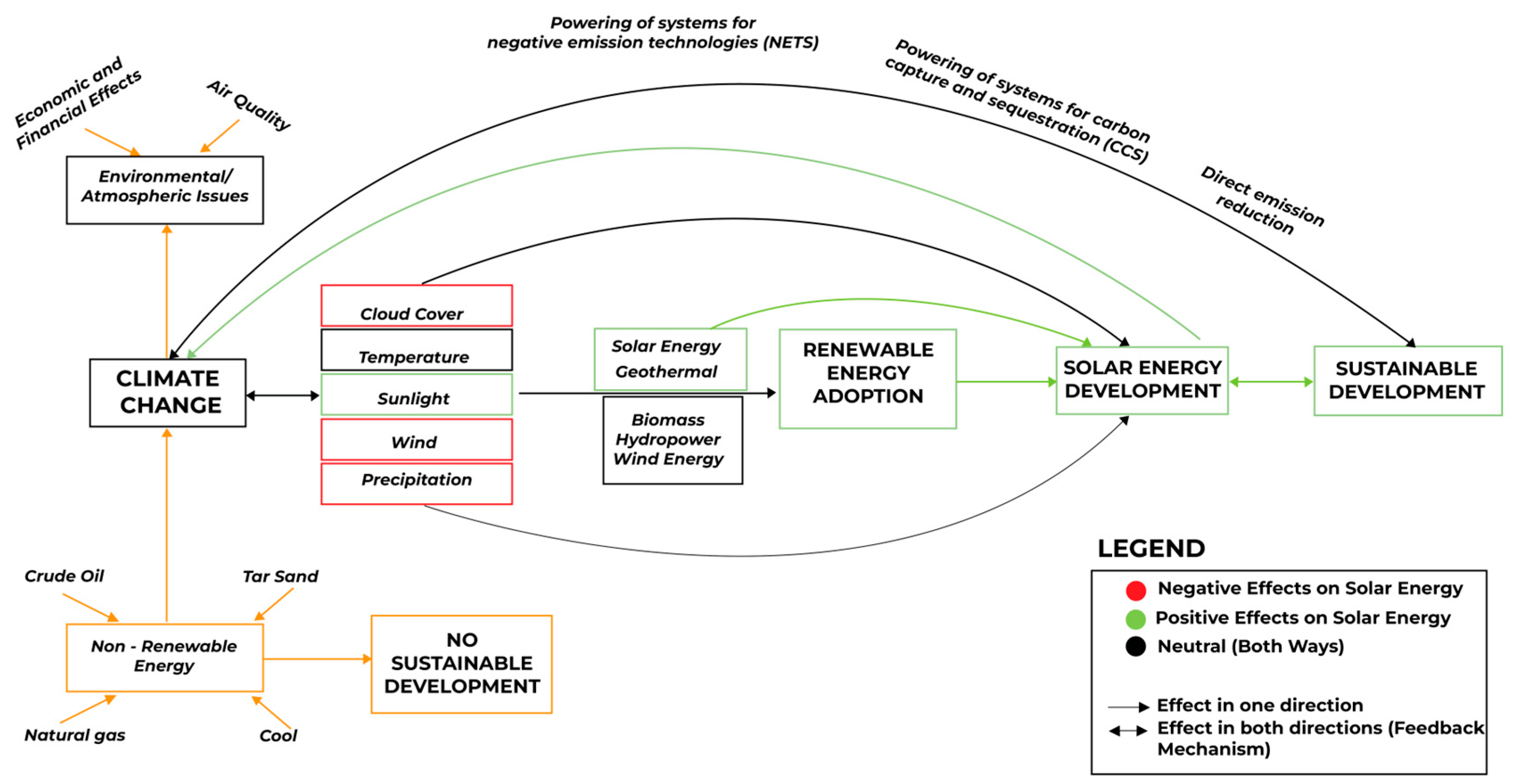

The subject of climate change has evidently been linked to the development of renewable energy (RE) technologies; various regions of the world continuously aim to directly or indirectly reduce their carbon footprint with a long-term view of sustainable development. The performance and reliability of these RE technologies are affected by the varying climates of regions (Panteli and Mancarella, 2015; Solaun and Cerdá, 2019). Historically, studies have been made to ascertain the positive impacts of the adoption of some RE technologies like wind (Barthelmie and Pryor, 2014; Belyaev et al., 2005), solar energy (Creutzig et al., 2017), hydropower (Berga, 2016; Lucena et al., 2018; Shaktawat and Vadhera, 2020), biomass (Bensch et al., 2021; Gustavsson et al., 2007), etc., for climate change mitigation. Conversely, little attention is being paid to the possibility of the effects of climate change / climatic variables on RE development; it is simply a feedback mechanism.

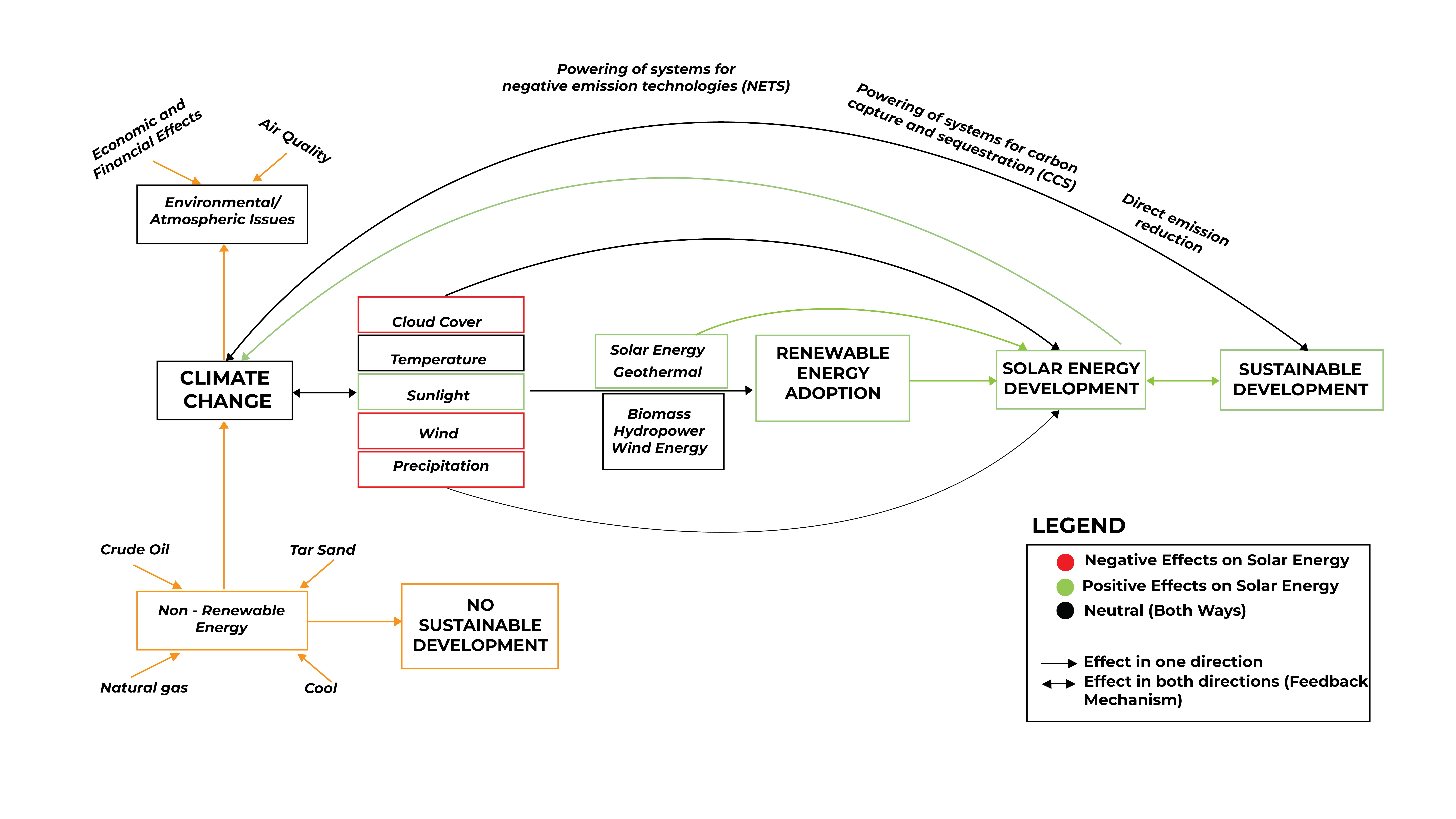

Solar energy development is one important aspect of RE that has the greatest potential for long-term growth as it embodies diverse technologies, including concentrated solar power (CSP) systems and photovoltaics (PV), which harness the thermal energy of the sun (Hernandez et al., 2015). Any region seeking to develop its processes for climate change mitigation will have to pay close attention to this development. Generally speaking, climate change management must involve at least one of these three technologies - carbon capture and sequestration/storage (CCS) (Hanssen et al., 2020; Kalkuhl et al., 2015; Wennersten et al., 2015), negative emission technologies (NETs) (Pires, 2019), and emission reduction (Fawzy et al., 2020). Only emission reduction can be affected directly by RE development (solar energy development for the sake of our study). CCS and NETs are two climate change mitigation techniques that do not directly take place as a result of RE development, except RE RE-powered systems are used to power these technologies. This proves that there is more to climate change mitigation than just RE or solar energy development, which is why the climate change impacts on solar energy development are being studied.

This paper will be narrowed down to the developing country of Nigeria and aimed at reviewing the impacts of climatic variables, including cloud cover, sunlight, temperature, wind, and precipitation, on the development of solar energy in Nigeria, with a broader view on RE. The next section will introduce the concept of climate change with its long-term progress and challenges in Nigeria.

Section 3 will provide a brief review of RE, which will be narrowed down to solar energy potential and past applications from a global perspective, and then narrowed down to Africa, West Africa, and Nigeria.

Section 4 will bring the two preceding sections together by drawing inferences from studies on the impacts of climate change on solar energy development. The utilization of solar energy – drivers, barriers, recent developments, and knowledge gaps will be presented in

Section 5. The paper closes with some concluding remarks.

2. General Overview of Climate Change in Nigeria

2.1. Concept of Climate Change

Climate change is a phenomenon encompassing the substantial fluctuations that are observable when monitoring climate conditions (Change, 2014; Parry et al., 2007). Often, such fluctuations in climate can occur gradually or it can be sporadic depending on influencing factors. Climate change is synonymous with action influenced by certain factors, both in frequency and magnitude, at diverse locations; these locations often experiencing different weather conditions are within a minimum land mass of 10 km sq. (Ibrahim et al., 2019). Ericksen et al. (2009) explains climate change as global warming based on pollution resulting in the production of greenhouse gases.

Climate change is often dependent on two factors: biogeographic (nature’s activities) and anthropogenic (human activities). The natural activities can be further divided into astronomical and extraterrestrial factors. The astronomical factors refer to changes in the Earth’s orbit eccentricity, the obliquity of the plane, and orbital procession; this has historically proven not to have severe effects on abrupt climate change (Tian et al., 2013). However, the extra-terrestrial factors refer to solar radiation quantity and quality (Akpodiogaga-a and Odjugo, 2010). Scientific research has shown that the earth is slowly warming up and the disastrous effects are gradually becoming evident as noted in the Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (Change, 2014; Parry et al., 2007) which documented evidence in explaining the devastating effects climate change has brought upon all parts of the human ecosystem.

2.2. Climatic Variations in Nigeria

Nigeria has an estimated population of over 200 million with a total land area of 923,800 sq. km. The country lies between latitudes 4 0N and 14 0N and between longitudes 3 0East and 10East. The country spans six major vegetative zones - mangrove forest, freshwater swamp forest, rain forest regions in the South, Guinea savanna in the middle belt, Sudan, and Sahel savanna are found in the North (Agbo and Ekpo, 2021; Alhaji et al., 2018; Haider, 2019; Otunla, 2019). Nigeria is located in the tropics and thus highly susceptible to high temperatures all year round (Agbo, 2021; E. P. Agbo et al., 2021; Agbo et al., 2022). The mean being 32 0C, but often the maximum average temperature can vary from 32 0C in the coastal area to 41 0C in the north. However, the mean minimum figures span from under 13 0C in the North to 21 0C along the coast (Balogun and Onokerhoraye, 2022; Oluwasegun and Olaniran, 2010; Shiru et al., 2019).

Topographically, the highest areas in the west, north, and east are 300m, 600m, and 1500m, respectively. The low-lying areas are typically below 300m and are typically along the coast and sometimes situated in the valleys of major rivers. The historic Udi plateau is aberrant among the typical coastal lowlands, where its predominantly coastal creeks and lagoons all encircle the Niger Delta. The Niger Delta comprises a lot of water channels, which in turn form many tributaries and estuaries, and is very rich in crude oil (Ugochukwu, 2008) and making it more susceptible to sea level rise, coastal flooding, and increased precipitation (Matemilola et al., 2019; Sayne, 2011). The water body’s volume and size are not independent of the rainfall volume in the western and southern parts of Nigeria.

The rainfall volume has experienced a decline in Nigeria, and evidence has shown that there has been a reduction in rainfall volume in Nigeria (1901-2005) by 81 mm (Akpodiogaga-a and Odjugo, 2010; Bello et al., 2012). The years between 1991 and 2005 have shown rainfall distribution increases in the coastal areas and decreased rainfall in continental interiors. The reduction is observed in the drop rate in rain days, which was 53% in North East Nigeria and 14% in the South-South Regions (Odjugo, 2005, 2007). Nigeria has been quite fortunate in not having experienced any serious global-induced catastrophe, but its agricultural effects have been felt especially in the North East regions, requiring a different methodology in crop rotation and migration of livestock in searching for grass resulting from a reduction in arable land (Akpodiogaga-a and Odjugo, 2010).

Nigeria possesses many climatic variated zones which can be broadly classified as vegetation and savanna zones. These zones experience diverse measures of temperature, precipitation, solar radiation and rainfall. Hence, it is pertinent to state that due to the fluctuations in such factors, the gradual reduction in rainfall is critically observed from North to South as is the gradual increase in mean temperatures observed from South to North. These climatic variations affect the level of solar radiation received in each climatic zone as does the seasons. Such climatic variations have been known to affect agriculture, urban planning, transportation etc. (Dillimono and Dickinson, 2015; Elias and Omojola, 2015; Onyeneke et al., 2018).

2.3. Ecological Effects of Climate Change in Nigeria

Climatic change is not without its ecological effects, which can either be good or bad. However, recent studies have explained increased temperature and decreased precipitation as being the greater results of climate change in Nigeria (Akande et al., 2017; Onah et al., 2016).

Table 1.

Ecological Dimensions reflecting key findings resulting from Climatic changes in Nigeria.

Table 1.

Ecological Dimensions reflecting key findings resulting from Climatic changes in Nigeria.

| Dimension |

Key findings |

References |

| Forest |

Desertification and flooding resulting in annual depletion rate of 400,000 hectares. Erosion, excessive winds and population demand due to supply shortage of wood in furniture making |

|

| Transportation |

|

(Idowu et al., 2011) (Idowu et al., 2011) |

| Health |

Increase in respiratory diseases, malaria, and skin pollution due to air and water pollution Predominant heat waves in the North Malnutrition resulting from poor harvest and water-borne diseases (diarrhea etc.) Average higher temperatures resulting in increased meningitis |

(Hassan et al., n.d.) (Woodley, 2011) (Abdulkadir et al., 2017) (Osuafor and Nnorom, 2014) |

| Agriculture |

Threatened possible starvation due to change in crop rotation cycle Unpredictable rain variations resulting low crop productivity Desertification has drastically reduced farmable land Loss of fertile ground, surface moisture, flora and fauna resources |

(Odjugo, 2009) (Amanchukwu et al., 2015; Ogbuabor and Egwuchukwu, 2017) (Odjugo and Isi, 2003) (Abdulkadir et al., 2017; Akande et al., 2017; Emodi and Ebele, 2016) |

| Hydrological cycle |

Extensive evidence of evaporation, precipitation, runoff etc. Lake Chad reduction approximately 95% since the 1960’s Reduced fishing productivity due to overrun of freshwater by increased salinity |

|

The ecological effects are felt in the aspect of vegetation reduction over Nigeria's vegetative zones. In the North, desertification and excessive winds have reduced the amount of farmable land, forest resources, and forced the migration of cattle rearers inland. Such migration has fueled an increase in population demand and health (Ogbuabor and Egwuchukwu, 2017; Woodley, 2011). The transportation sector, which is key in Nigeria's infrastructure, suffers predominantly during the rainy seasons following the destruction of roads and tracks and the overflow in drainage systems, thus making road transport slow and cumbersome. Climatic changes have become a health concern following the increased release of carbon and other effluents into the atmosphere. Respiratory and skin diseases are on the increase, as has been the spate of acid rains (Abdulkadir et al., 2017; Woodley, 2011). Climate change has impacted Nigeria's hydrological cycle and has reduced fresh water availability, as observed in Lake Chad and the evaporation rate; there has been a reduction in fishing due to increased salinity in fresh water sources. These adverse effects of climate change require government intervention in the effective implementation of policies and schemes that will aid in mitigating these disasters (Adebimpe, 2011; Emodi and Ebele, 2016; Woodley, 2011).

2.4. Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions in Nigeria

Edeoja and Edeoja (2015) In their work measured the resultant amount of carbon dioxide from the construction activities of some organizations. The results showed a substantial CO2 emission from the industries under review, and there was little or no emission management. The companies lacked the technical skills, and even those with them were uninterested in dealing with the emission and environmental problems. The Niger Delta, due to its large crude oil deposits, is consequently an area of high-density carbon emissions due to the region’s continuous gas flaring (Ibrahim et al., 2019). A study that aimed to gauge the level and distribution of carbon emissions by monitoring two flow stations of the Shell Petroleum Corporation for a quarter of a year (Nwaichi and Uzazobona, 2011) showed the region suffered a substantial impact from the flaring activities and is in dire need of contingency plans to efficiently combat this menace. Acid rain, which has become a common occurrence in the Niger Delta, is due to the massive amounts of gas flaring by oil companies situated in the region. The acid rain is formed from the sulfur and carbon emissions generated at the numerous flaring points located within the region (Nduka et al., 2016).

In reducing emission production, it has been recommended that the Nigerian oil and gas industry employ a different and less polluting production method. (Otene et al., 2016) researched converting flared gases to compressed natural gases (CNG), which could be a sufficient fuel alternative for the Lagos bus rapid transit scheme (BRT)-Lite. This study is conclusive on the idea that the substitute use of CNG as vehicle fuel will reduce Carbon emissions. Carbon emission management studies have pushed for research in carbon emission as observed in (OKhimamhe and Okelola, 2013). Carbon emissions in Niger state major cities were measured as surpassing the regulatory limits of 350 ppm of CO2 (atmospheric), however, it was less than 5000 ppm, which is the maximum safe limit of the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Administration. In rectifying the emission level Nigeria can resort to selling its emission as contained and propose by the Kyoto protocol based off the results measurement of Nigeria's emission of global world carbon emissions at 0.4% (Igwenagu, 2011).

The prior stated paragraph enumerates few of t the negative effects centering on GHG emissions and are dire reasons for championing a green economy. A green economy’s main idea is capitalizing on efficient production activities for sustainable development factoring the following three criteria; human, economic and environmental. Also the GHGs in the atmosphere do not suffer any territorial boundaries hence the high level of alertness it has received from developed and developing nations alike. Regarding renewable energy, investigations have reflected the need for adopting renewable energy structures in utilizing carbon emissions as fuels (Dogan and Ozturk, 2017).

Nigeria has reserves of about 184 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas and is possibly the nation with the 9th largest gas reserves in the world. It is estimated that the country loses over $2 billion annually in gas flaring (Mrabure and Ohimor, 2020; Oyedepo, 2012). Prohibiting gas flaring has proved impossible which has left the only reasonable pathway being carbon credit management (Böhm, 2009; Hepburn, 2007). Utilizing the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) of the Kyoto protocol has proved functional in this regard. Here parties included in the Annex I3 utilize projects based on Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) and nations in the Annex I utilize the CERs from such projects in meeting up their quota of their specific emission levels and depletion requirements stated in Article 3 of the Protocol. The petroleum industry in Nigeria is quite the stage for projects having emission reduction levels, however the Federal Government has been reluctant in setting up appropriate legislation as regards emission in the petroleum sector. If the Government can be proactive in their policies towards carbon emission trading and utilization for renewable energy, this will have a profound effect on the country’s energy utilization and reduction in GHG emission. This is where proposing sustainable and achievable policies comes in.

2.5. Policy Making Regarding Climate Change

There exist two categories under which response to climate change can be classified; mitigation and adaptation (Reckien et al., 2018; Van Vuuren et al., 2014). The mitigation aspect which the Federal Government is currently devising revolves around one of two; reducing GHG emissions or increasing carbon capture and sequestration (CCS). The adaptation refers to an adjustment of all climatic stimuli influencing systems aimed at reducing the possible adverse effects.

Nigeria has enacted policies which it has over the years use in combating the environmental adverse effects of climate change; National Policy on Drought and Desertification, and Drought Preparedness Plan (2007) (Medugu et al., 2008), the National Policy on Erosion, Flood Control and Coastal Zone Management (2005) (Sunday and Ajewole, 2006), Draft National Forest Policy (2006) (Fajemirokun, 2021; Ujor, 2018), National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (2004) (Akindele et al., 2021) etc.

There have been few enforced frameworks by the Nigerian Government towards specific niches in the ecosystem; Nigerian Agricultural Policy (2001), the National Water Policy (2004), the National Tourism Plan (2005). The prior listed policies implementation has been less than ideal however it has sensitized and pushed for better directives as regards managing the ecosystem, pollution and the variations of climate change (NPCC, 2013). Nigeria's Vision 2020 was severely weak in terms of current visible stability and long-term growth, necessitating the country's 2021 Climate Change Act. The new Act codified national climate policies by requiring the Ministry of Environment to establish a carbon budget, maintain average world temperature increases below 20 Celsius, and pursue efforts to prevent temperature increases to 1.50 Celsius over pre-industrial levels (IUCN, 2022).

3. Solar Energy as a Renewable Energy (RE) Resource

3.1. The Need for RE / Global, Africa and Nigeria’s RE Adoption

The need for renewable energy (RE) has become heightened over the past decades as the impacts of climate change has been erroneous in no small measure; the drawbacks arising from the negative effects of climate change cannot be over-emphasized. RE resources are as a result of inexhaustible sources of energy (Emmanuel P. Agbo et al., 2021a), and their use will not diminish their availability (Qazi et al., 2019). The word ‘renew’- ‘able’ etymologically means that these energy sources are not only “inexhaustible”, but can be replenished by natural means. The availability of these resources cannot be affected by their rate of consumption (Kehinde et al., 2018).

The combustion of fossil fuels has largely contributed to the increase of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the earth’s atmosphere; this development has hitherto brought about the creation of policies that support the adoption of renewable energy as a major source of energy generation.

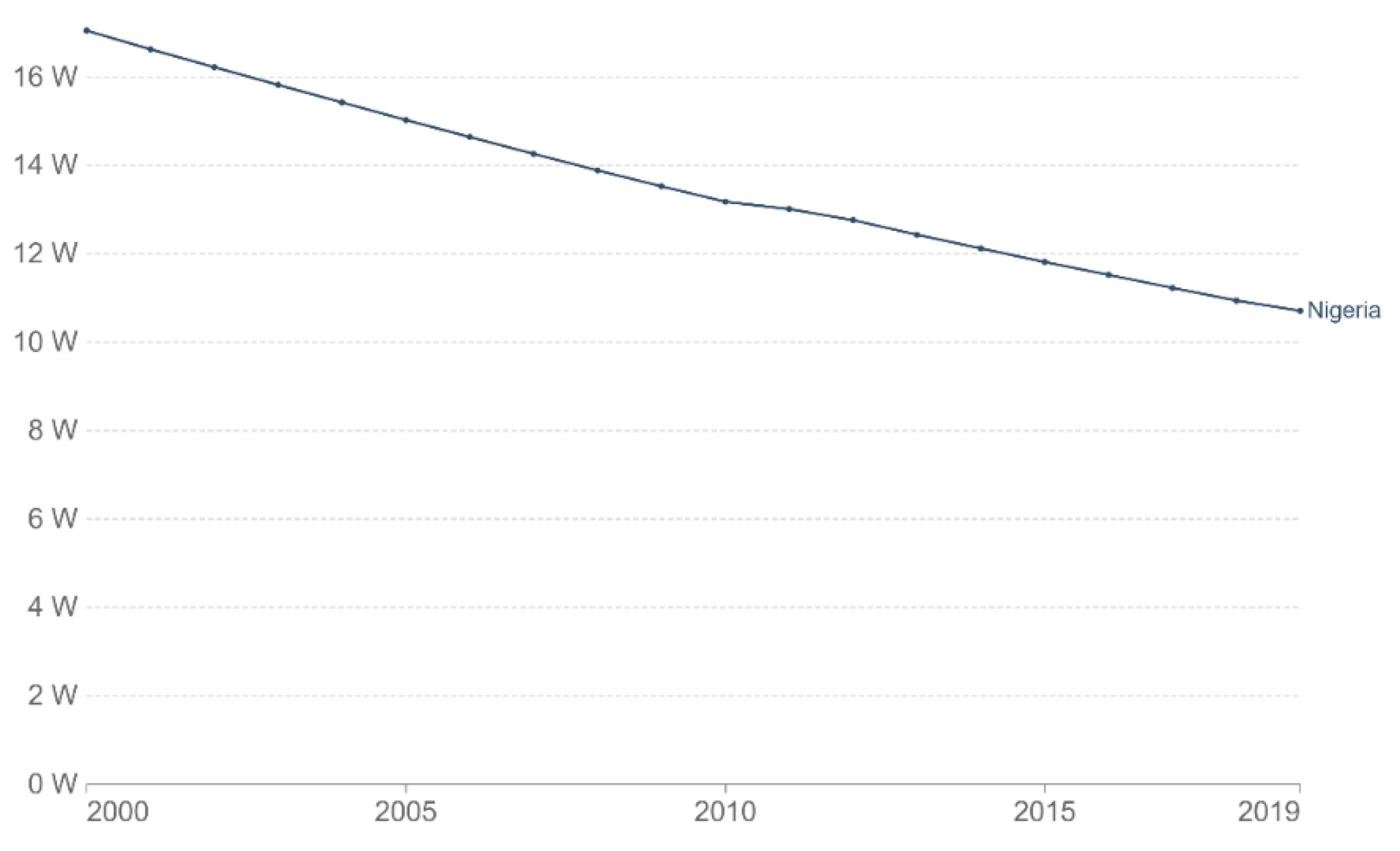

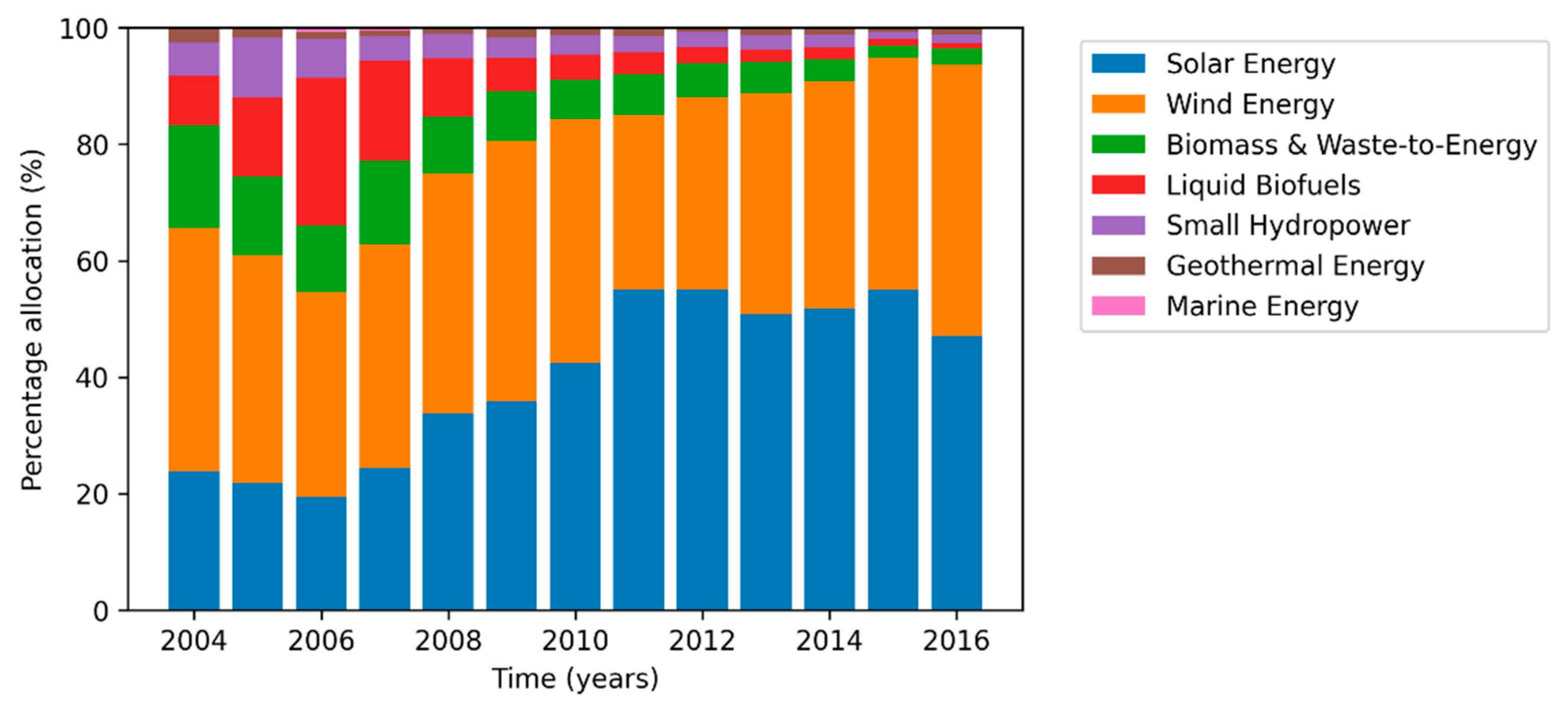

The achievement of Nigeria’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (which has one of its objectives as adopting clean energy in an ever increasing proportion) has always hit a brick wall in Nigeria and many other African countries. The existence of these challenges stems from either the adoption of strategies that are not sustainable or that are not followed up properly (Adewuyi, 2020). The renewable electricity generating capacity has been shown in

Figure 1; this daunting figure shows that the potential for an increased adoption of RE in the region is barely improving on a large scale.

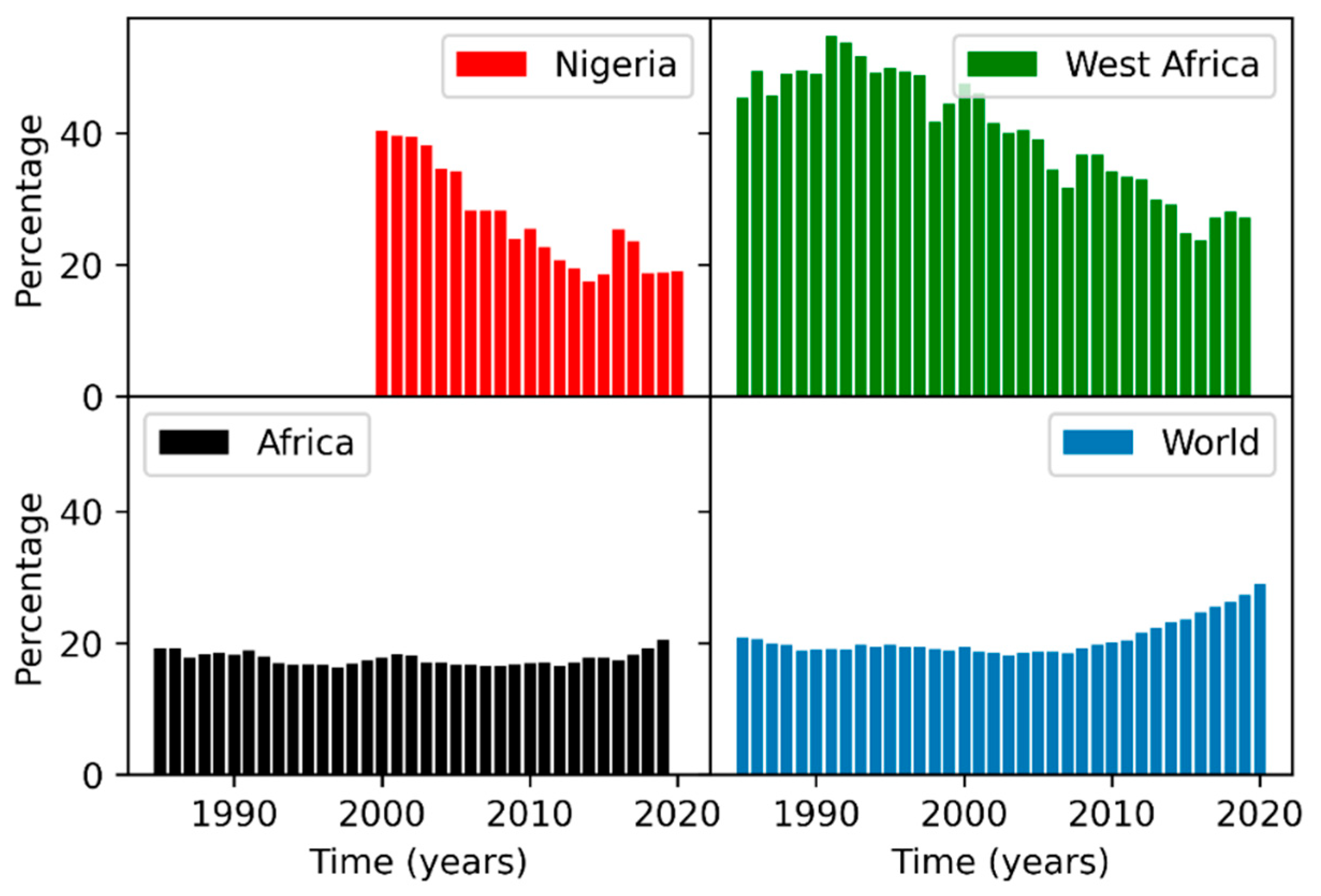

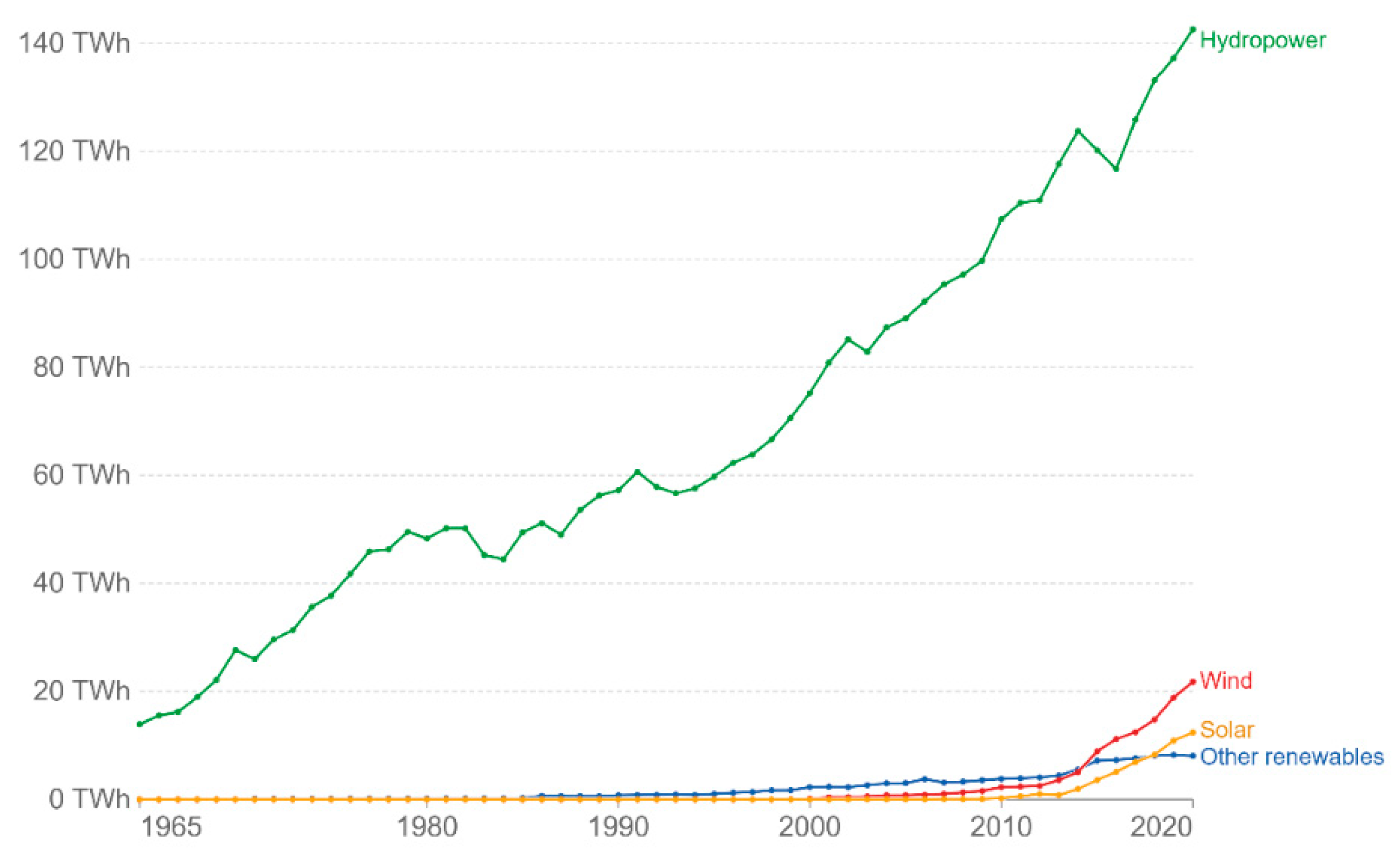

Figure 2 puts this potential into context by displaying the percentage of electricity generation from renewables from a Nigeria, West African, African and the world’s perspective. The figure shows that the percentage of Nigeria’s total electricity generation from RE has been reducing annually (about 40% to 20% ) since data was being kept (2000 – date) by ‘Our World in Data’ (Ritchie and Roser, 2020). The same trend is observed for West African countries. In a surprising turn of events, the trend for Africa has been relatively stable at about 20% since 1976 while the world’s percentage has grown in recent years to over 30%. Akinbami, (2001) explained that the projections for adoption of RE is non-linear, in contrast to the popular opinion that the growth of clean energy can be assumed to be linear. He went further to buttress on the fact that despite the high RE potential (especially in solar energy), hydropower takes the largest share of commercial RE; this can be seen from the figure of RE generation in Africa in

Figure 3. This large hydropower coupled with the prevalent use of fossil fuels (depleting hydro-carbon resources like coal, gas, oil, etc.) encompass a very large percentage of electricity generation in Nigeria (Aliyu et al., 2015). Renewable energy utilization demands the installation of control systems for their integration (Badal et al., 2019), and this results in majority of the costs for effective utilization (Foster et al., 2009).

The main purpose of RE adoption is for the application in our everyday lives. To maximize this potential (Ikuponisi, 2005) explained that for RE to become sustainable and successful in Nigeria or any region for that matter, its implementation along with the application in activities such as agriculture and other small scale industrial applications has to take place; this will prove fruitful, as these are areas that also need sustainable growth. This is true because as any region seeks to improve her agriculture and small business for example, the inclusion of RE in this single development will serve multiple benefits. Other areas where the energy production from RE can be adopted is in improving areas like education, health, transport sectors; furthermore, it can serve as instruments for politics and even security (Sambo, 2009). The problem with developing countries like Nigeria is that from the above, having different sectors like the aforementioned, that require growth and development along with RE, leads to a tendency to neglect the growth of RE and focus on these other sectors like education, agriculture, etc. This brings about the problem where these sectors grow above the RE and hence their energy required for maintenance is far greater than what RE can produce. The result of this will be a reduction in RE development and energy generation compared to fossil fuels (

Figure 2) when the pace of other sectors is being focused on. (Shaaban and Petinrin, 2014).

The adoption of RE has become more important as a result of an increasing population in Nigeria. Research has been made on the analysis of regional, climatic, social, economic and technical factors, etc., affecting the energy supply of rural areas based on predictive estimates and results from (Shaaban and Petinrin, 2014; Shepovalova, 2015) and (Lutz et al., 2017) revealed that knowledge exchange, the existence of key actors, and/or the use of goals and milestones are paramount together with stable policies for the improvement of RE adoption in rural areas. A study from (Ohunakin, 2010) and (Shaaban and Petinrin, 2014) revealed that even though Nigeria’s population is ever increasing (estimated to be over 200 million currently), the energy consumption per capita consumption from major fossil fuel sources has been declining, revealing the fact that Nigeria’s energy consumption for every citizen is reducing. This could easily be attributed to the fact that lower power consumption appliances have been produced, but another scenario us the lack of sufficient and sustainable energy from fossil fuels.

(Emmanuel P. Agbo et al., 2021a) described solar energy as the “primary RE resource”. This arose from the idea that all renewable energy resources are in one way or the other affected by sun rays which reaches the earth in (i) particle form, (ii) electromagnetic (EM) radiation and/or (iii) the magnetic field coupled with the intermixing particles. However, EM radiation is said to have the most effect on the earth’s RE variation. Solar energy is arguably the renewable energy resource that receives the most public attention, and although its adoption for the purpose of energy production has not been maximized, the knowledge that this sector has arguably the greatest potential for improvement due to availability of the resource cannot be overemphasized (Escobar et al., 2014). This makes solar energy arguably the most untapped RE resource (Bahadori and Nwaoha, 2013), making the improvement and adoption of solar energy very paramount.

The need to study the variations of climate change and how its change over a long period of time affects solar energy is of great importance. Meteorological variables like sunshine duration, ambient temperature (which relates to global warming), cloud cover, rainfall, etc. play an important role in photovoltaic systems applications (Myhan et al., 2017; Sağlam, 2010) and by default climate change increment should affect (increase or decrease) the availability of these meteorological variables (Burnett et al., 2014). The percentage of renewable investment from

Figure 4 shows that the global investment in solar energy is increasing, not just in the amount of funding but in the overall percentage when compared to other renewables.

3.2. Solar Energy Output Capacity and Generation

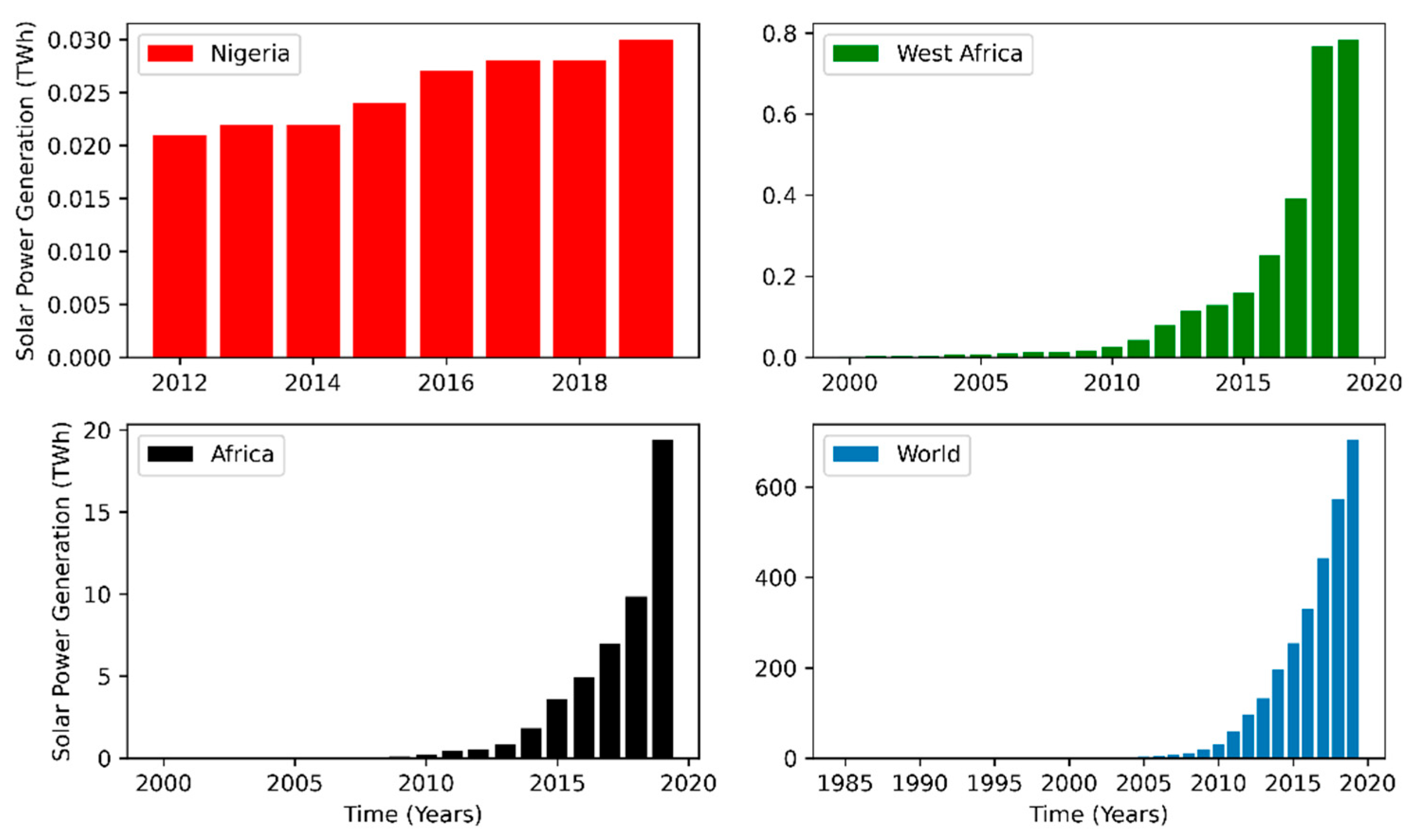

Nigeria’s solar energy potential is high as the country is located in a region where the sunshine duration and intensity is high and direct (Emmanuel P. Agbo et al., 2021a, 2021b), this is in contrast to most locations in the poles where the sunshine duration and radiation intensity is lower (Ozoegwu, 2018). The results of this is in massive contrast to what we see from

Figure 5, as the solar energy electricity generation in Nigeria only reached a mere 0.03TWh. This increase has been at a much slower rate when compared to West Africa, Africa and the World’s growth rate in the same figure.

One of the major barriers for that application and utilization of this resource ranges from technical issues like low efficiencies of solar cells, economic hindrances due to misplaced priorities leading to lack of proper financial allocation for research, development and follow-ups, (Kabir et al., 2018; Shahsavari and Akbari, 2018). This makes solar energy a profitable resource for managing long term energy issues (Kannan and Vakeesan, 2016).

Table 2.

Recent developments and research focus and applications of solar energy in Nigeria.

Table 2.

Recent developments and research focus and applications of solar energy in Nigeria.

| Recent Developments |

Area of Application/Research |

Comments |

References |

|

Agriculture |

Solar energy has been utilized for the production of required solar heaters (water or air) or by directly heating hatcheries (incubators) and brooding space. (solar chick brooders)

Solar modules are used for water pumping especially in rural areas where grid electricity is not predominant.

|

(Ilenikhena and Ezemonye, 2010; Ohunakin et al., 2014; Sambo, 2009; Yohanna and Umogbai, 2010) |

| Refrigerated food, drug store and pollution reduction |

Medical Sciences and Health Benefits |

Some food and drugs need to be kept at certain temperatures for preservation. The ability to meet the cold-chain requirements for the storage of vaccines and other sensitive medical equipment cannot be overemphasized.

Solar powered mini refrigerators have also been applied to preserve other edible medical products.

The Health benefits of solar energy has come as a result of less pollution in the environment. This is due to a reduction in the emission of fossil fuels arising from RE technologies. |

(Anabaraonye, 2020; Okoro and Madueme, 2006; Yohanna and Umogbai, 2010) |

| Policies to support cleaner and safer development in Nigeria |

Waste Management |

Setting up of policies to ensure that new Plants in Nigeria invest in recycling of already used solar PV modules. This has encouraged more adoption on the long run, although the initial adoption may prove difficult, government support will crystalize adoption |

(Chigbogu Godwin Ozoegwu and Akpan, 2021) |

| Improved Solar Cooker Performance |

Cooking |

This process applies phase change materials as thermal energy storage to delimit the main drawback of solar cookers which is their reduced performance during periods of sunlight shortage (when solar radiation is relatively low) |

(Omara et al., 2020) |

| Understanding PV Orientation for maximum energy capture |

Industrial Power Generation |

For even production throughout the year, add 15 degrees to the latitude of a location. This will create an average optimum angle. Systems can then be installed for optimum production after benefit-cost ratio can been determined to make informed long-term financial decisions on the choice to use manual or automatic tilting equipment. |

(Emmanuel P. Agbo et al., 2021a; Oji et al., 2012) |

| Rural electrification and street lighting |

Local Power Generation |

The percentage of power allocation to rural communities is relatively low when compared to urban areas. This has created an avenue to apply some newly inspired solar energy generation ideas for street lights and minor electrification by adopting storage devices and controllers.

Research has shown that the utilization of hybrid solar PV-diesel powered systems has reduced cost of electricity generation when compared to systems that uses only diesel. |

(Adaramola et al., 2014; Giwa et al., 2017; Mohammed et al., 2020; Ohunakin et al., 2014; Sambo, 2009) |

| Crop, fish and manure dryers |

Agriculture |

The processes for energy generation can be quite complicated when the requirement is just heat. Solar dryers have been formed by mechanizing the methods of using solar radiation to dry crops and other produce. This method excludes the ‘traditional’ open air drying. These dryers ensure a more complete drying and longer storage. |

(Ilenikhena and Ezemonye, 2010) |

| Building Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) System |

Domestic/residential use |

This innovative idea involves adopting PV modules in place of our conventional building materials. The BIPV system involves using building fabrics that have PV electricity technologies. This development will reduce cost drastically as the cost of PV modules will be offset by the building material cost which has been replaced. |

(Elinwa et al., 2021; Chigbogu Godwin Ozoegwu and Akpan, 2021) |

| System Advisor Model (SAM) |

Grid connected power projects (Domestic and Industrial) |

This recent development has been applied to give a better underrating of the financial viability of a project for the long term. The model takes into account the net present value (NPV) and brings forth different configurations for the power system.

The goal of all this is to be aware of the economic feasibility of project on the long term. This long-term look could be related to Climate Change. A positive NPV will show that the project is financially viable for the long term. |

(Elinwa et al., 2021) |

| Application of geostatistics technique |

Large Scale grid application |

The application of this technique is to access the viability of regions in the country to sustain large-scale solar energy generation.

Solar radiation reaches all open areas as we know, but the land areas that are exposed to Direct Normal Irradiation (DNI) are the exact locations that this analysis technique will reveal. The goal is to identify locations that will produce sustainable power. Results show that even with a small percentage of viable land area in the eastern region (0.67%), sustainable energy can be produced if well utilized |

(Chiemelu et al., 2021) |

| Application of the reduction factor analysis technique to reveal the available rooftop areas for possible PV utilization |

Household and building rooftops |

The accuracy of this analysis technique depends on the optimally inclined tilt angle for the particular location in study as well as the solar irradiation received on these tilted surfaces.

A widespread application and deployment of this would educate the average man on how to maximize radiation reception on their rooftops. The economic viability of this can prove beneficial on the long term, positively impacting quality of life |

(Ayodele et al., 2021; Ayodele and Ogunjuyigbe, 2015) |

| Solar green or glass house |

Agriculture |

This has not been applied to a reasonably large extent in Nigeria. But research shows that this will prove viable during the cold/harmattan season throughout regions of Nigeria. This creates a system where long-wave radiation can be controlled, unlike that which penetrates after the ozone layer. The goal is to help facilitate the healthy growth of agricultural plants regardless of times and seasons. Also served as a method to ensure controlled research. |

(Sheyin, 2000) |

| Solar Drying |

Agriculture and Commerce |

This includes but not limited to solar rice drying, solar wind ventilated cabinet drying, glass-roof solar drying, solar timber drying, etc.

All these methods of applying heat from solar radiation has proven to be better and more reliable than open air sun drying and natural drying in shade which is affected by storms, rain, and various pollution types. |

(Bolaji, 2003; Okoro and Madueme, 2006) |

|

Engineering |

Solar PV generators are being used for the powering of relay telecom stations (linked from one region of the nation to another). This is important because asides from improving communication, it reduces the frequency of road trips and fuel consumption from the transport sector. Large convex lenses or parabolic reflectors can be used to concentrate solar radiation on very small areas for the sole purpose of generating high temperatures for buildings. This will serve as a method of keeping buildings warm during cold seasons like the harmattan. |

(Okoro and Madueme, 2004) |

| Hybrid PV solar-diesel power system |

Small scale businesses |

Research using Hybrid Optimization Model for Electric Renewable (HOMER) software has shown that the long term financial effects of small scale businesses that uses diesel powered generators or other fuel sources are higher than businesses that use hybrid PV solar-diesel power system especially in the northern regions of Nigeria where solar radiation is comparatively higher than the southern region. |

(Adaramola et al., 2014) |

3.3. Solar Energy Applications and Recent Developments in Nigeria.

The recent developments and the applications of solar energy in Nigeria stem from the need for the creation of sustainable RE power.

Table 2 gives a necessary breakdown of the different areas where the recent development/research and applications of solar energy have been made in. The table gives a breakdown of 18 different studies cummutaively showing about 15 unique development and applications.

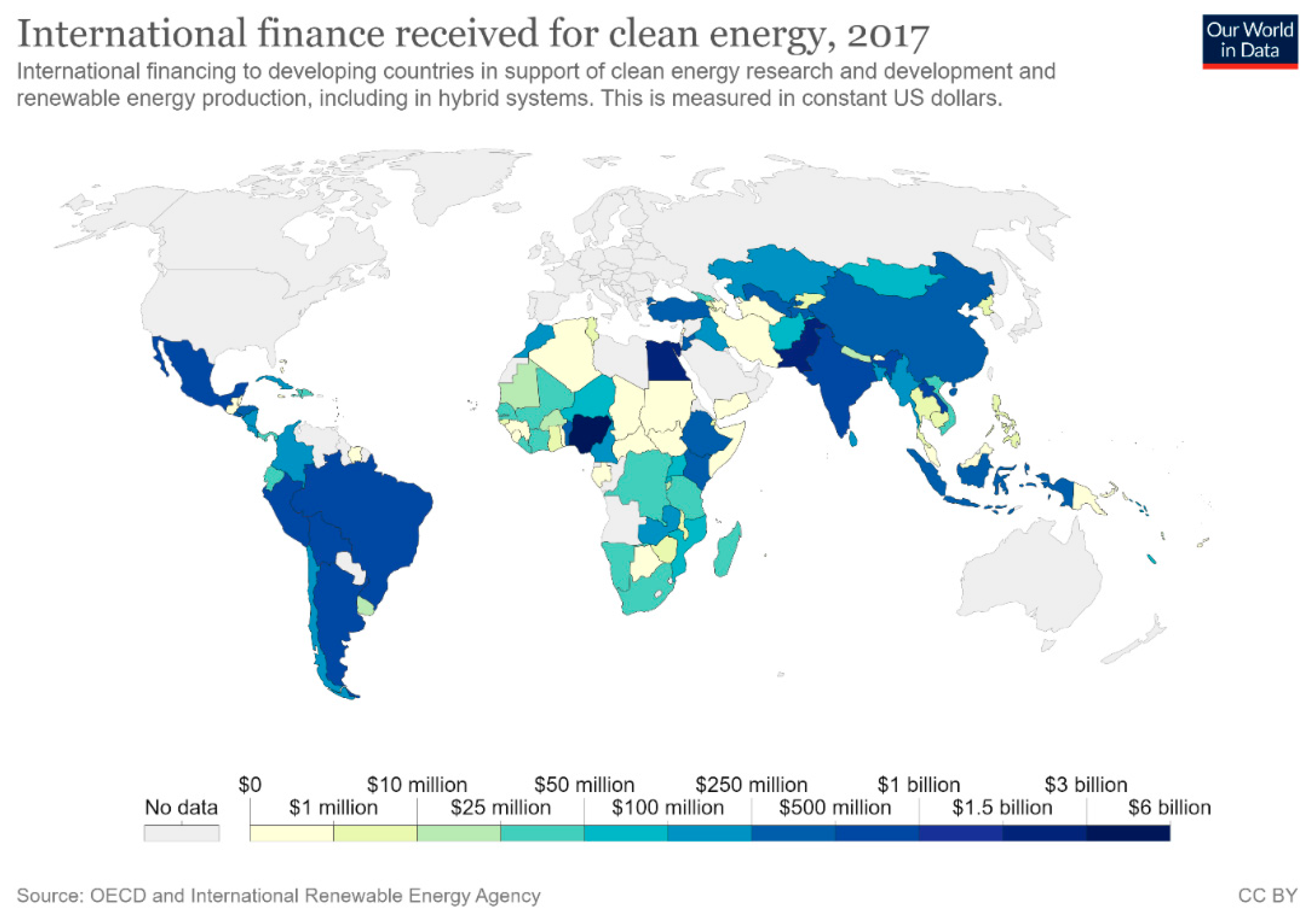

Table 2 shows that the most recent developments of solar energy in Nigeria has come as a result of innovative research that are consistenly improved upon to yield the best application methods. This reveals that the creation of policies that will support and encourage research development is the most important (Chigbogu Godwin Ozoegwu and Akpan, 2021; Chigbogu G. Ozoegwu and Akpan, 2021). The inclusion of adequate finance is an important driver in executing these policies; also disseminating these funds appropriately is important; the inclusion of finnace as a factor for these policies cannot be ignored as solar energy has been proven to be financially viable in a country like Nigeria where radiation intensity is high (Njoku and Omeke, 2020). But history has shown that financial access alone has not solved the problem of sustainable development; Nigeria received over 6 billion US dollars for solar energy investment in 2017 (

Figure 6). The policies being created must encourage research and development without being overly focused on finance.

Applications of solar energy in areas like medicine/health, agriculture, enginerring, telecommunication, domestic and commercial appliocations, etc., proves the diversivity in the application of this renewable resource in Nigeria and the importance of considering it important for consistent development in the same way with all other aforementioned areas.

The application of solar energy arises when the solar radiation from the sun’s disk is converted to biomass, heat, or electricity via solar PV or solar thermal conversions (Ilenikhena and Ezemonye, 2010). Applications and recent developments have also been achieved in the grid system, with specific applications in hybrid PV solar-diesel power systems (Emmanuel P. Agbo et al., 2021a); these hybrid systems have been made more effective by using automatic solar trackers and recent development in switching and control devices to make them more effective in areas like engineering and telecommunication.

Analysis techniques like the system advisor models (SAM) (Elinwa et al., 2021), geostatistics techniques (Chiemelu et al., 2021), reduction factor analysis (Ayodele et al., 2021; Ayodele and Ogunjuyigbe, 2015), etc., are being consistently applied to understand the financial viability, the production viability, the viability of a location to produce effective and sustainable solar energy.

The effect of long-term climate on the developments and applications of solar energy has led to more studies related to the forecast of the potential for electricity development from solar energy. This has arisen from the fact that global warming is being predicted through climate change modelling. Whereas, on the flipside, an improvement in the adoption of solar energy and even other renewables will bring about a long-term reduction in the annual rate of global surface temperature.

4. Impacts of Climate Change and Climatic Variables on Solar Energy Development

Climate encompasses the average weather patterns over a geographical area over a long period, exhibited by various climatic parameters. We can also define climate change as the unnatural display and unusual phenomenon of weather patterns caused mainly by anthropogenic disturbances. These weather or climatic patterns increase or decrease, causing abrupt changes. In other words, the bombardment of GHGs in our atmosphere affects both climatic patterns and renewable resources (Solaun and Cerdá, 2019) and thus has a direct impact on energy generation (Ohunakin et al., 2015). Studies from (Chiemeka, 2008; Olayinka, 2011; Osueke et al., 2013; Uko et al., 2016) have shown that solar irradiance varies across weather conditions and geographical locations in Nigeria. Hence, locations applicable for solar energy production are predicted to be less sustainable in the future due to climate change. We look at the various parameters associated with Climatic parameters and their effect on solar energy development in Nigeria:

4.1. Cloud Cover

Cloud cover is a major weather parameter for determining the amount of solar radiation reaching the earth’s surface. (Luo et al., 2010). The fraction of solar energy reaching the earth’s surface varies depending on the degree of cloudiness. Hence, all the different types of cloud raging from Nimbostratus, Altocumulus, Stratus sky and Cumulonimbus affects solar radiation reaching the earth’s surface (Blal et al., 2020).

Cloudy days reduce the amount of sunlight collected by solar panels (Gordo et al., 2015). Solar radiation can be intensified in certain weather conditions (Matuszko, 2012) or weakened through the reflection of the solar radiation back into space because of the abundance of air pollution – anthropogenic aerosol waste causes a ‘fog-like haze’ capable of absorbing or scattering the sunlight back to space or diffused in different directions over the earth’s surface. And from studies, we can see that diffused radiation has a reduced effect on solar PVs than direct radiation received especially at optimum angles (Kelly and Gibson, 2009; Redweik et al., 2013). An increased solar irradiance received from the sun disk is directly proportional to a lower degree of cloud cover, directly proportional to increased global mean surface temperature and vice versa (Blal et al., 2020; Yusuf et al., 2017).

The phenomenon associated with the interaction between solar radiation and cloud cover is of importance because the incoming radiation that passes through the cloud to the earth’s surface is what is converted into electricity and other solar energy uses like CSP (Olomiyesan et al., 2015). While the sun is the primary source of energy, solar energy is largely dependent on the nature of the cloud cover in various regions (local meteorological and eventually climatic conditions) and the abundance of air pollution which is majorly caused by the combustion of fossil fuels, especially in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria (Elum and Momodu, 2017). On cloudy days, solar panels produce only 10 – 25% of their capacity (Richardson and Harvey, 2015). Finally, the cloud cover from various factors like atmospheric aerosol and other carbon compounds contributes to a factor in climate modelling called ‘the effective number of layers’

4.2. Temperature

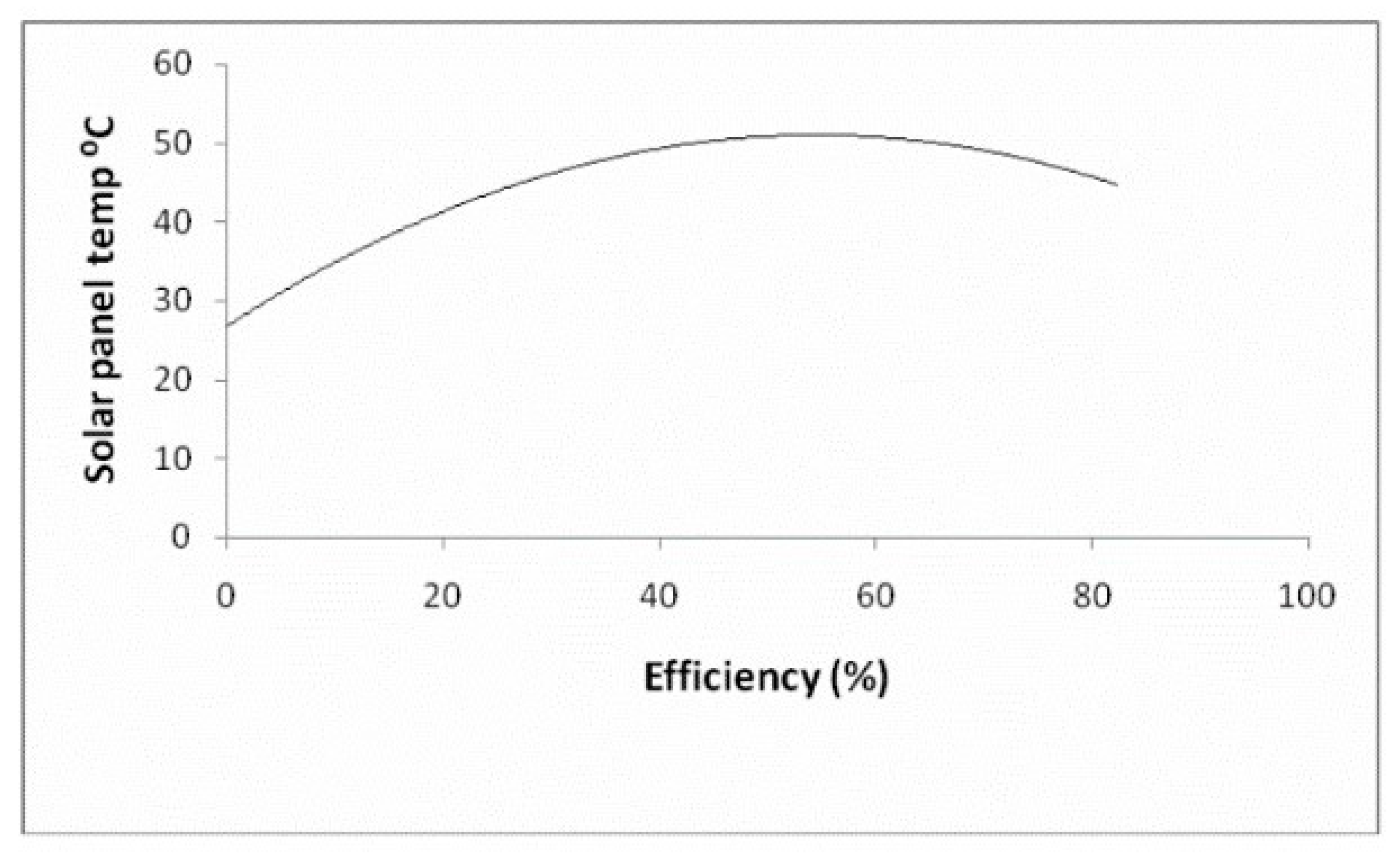

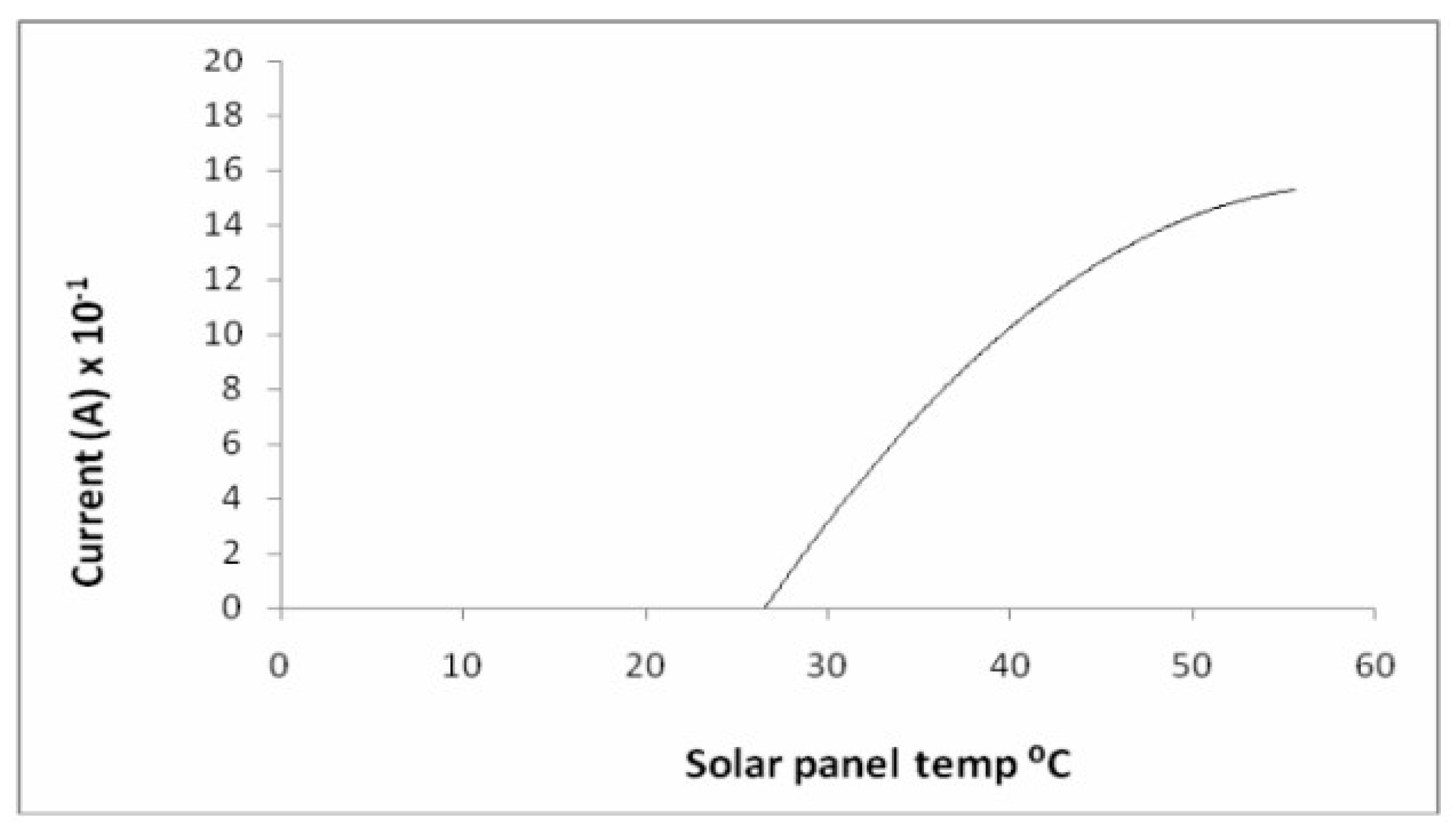

Solar energy is converted to electrical energy through a semiconductor PV cell using a p-n junction (Pospischil et al., 2014), Moreover, the maximum output power, short-circuit, and open-circuit voltage of the PV cell are affected by temperature fluctuations (Zaini et al., 2015). An increase in surface temperature caused by ambient temperature and operating temperature reduces the efficiency and performance of solar PV systems due to the internal carrier recombination rates in semiconductors, caused by increased carrier concentrations (Dubey et al., 2013; Salehi et al., 2021). According to (Salehi et al., 2021), for every degree increase in ambient temperature (in Celsius), the PV panel’s efficiency decreases by 0.5%. Research by Omubo-Pepple et al. (2009) shows that high temperature from 43

oC reduces the efficiency of solar panels (

Figure 9) as the current increases with increasing temperature to about 43

0C before it begins to drop (

Figure 10). An increase in heat reduces solar power output by 10% to 25% (Gordo et al., 2015)

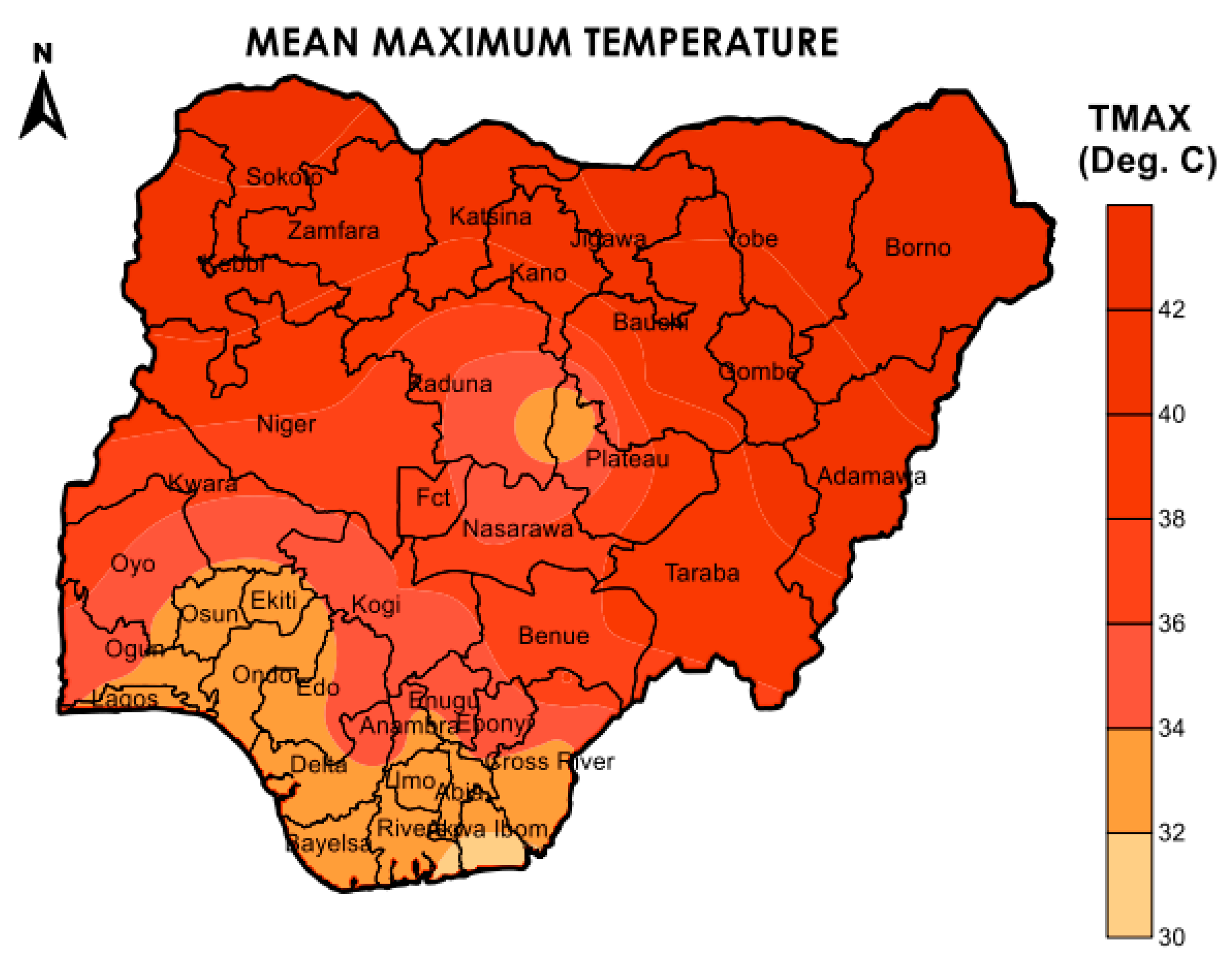

Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMet, 2022) in April (01 – 10), 2022 recorded the highest mean maximum temperature in Borno state, Nigeria as 44.1°C, while parts of Cross River State and Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria recorded the lowest at 30.1°C. Temperatures in some of the central cities as well as a few locations in the southern states, were colder than normal.

Figure 8 is the map of Nigeria capturing the recorded mean maximum temperature in degrees Celsius for all the thirty-six states in Nigeria and her capital cities; the northern part of Nigeria, particularly the North East and North Central, has a temperature that approaches about half the temperature of the boiling point of water with values ranging from 40

0C to 44.1

0C. The south-south and southwest states, excluding Oyo and some parts of Ogun state, record a temperature lower than normal, ranging from 30

0C to 34

0C, while the Middle belts and South East region read to a temperature from light orange to 40

0C.

Research conducted (Uko et al., 2016) at Rivers State University, Nigeria, shows an increase in the mean monthly solar energy in the dry season. (Osueke et al., 2013) cited Maiduguri as the state with the highest solar radiance and more suitable for mounting solar panels when compared to Enugu, Lagos and Abuja in Nigeria. In Yola, Adamawa, Nigeria, maximum values of global solar radiation were observed from March to May (during dry season) and minimum in August and September (wet season) (DW and Yakubu, 2011). But it should be noted that the efficiency of these PVs will be greatly affected negatively with high mean maximum temperature recorded in the region, and with the prevalent increase in global surface temperature, this will likely increase if nothing is done.

While the efficiency and performance of PV cells may differ in types and constructions, the above reviews and research have shown that climate change in terms of global warming and temperature fluctuations can curb solar energy development and adoption especially in Nigeria.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 represent temperature to efficiency and current using PV modules in Port Harcourt (tropical climate region) using a B-K precision model 615 digital light instrument. We see in

Figure 9 that efficiency is zero with a temperature lower than about 25 degrees Celsius and the efficiency increases with increasing temperature until it gets to the maximum operating temperature of the PV module.

Figure 10 shows that at a temperature of 25.2

0C current remains at zero amperes after which a gradual and steady flow of current increases as the temperature increases to about 43

0C and then begins to drop indicating the maximum operating temperature of the photovoltaic module (Omubo-Pepple et al., 2009)

4.3. Precipitation

A correlation between total solar irradiance and changes in regional precipitation exists (Agnihotri et al., 2011; Perr, 1994). Global warming has led to surface drying but greater evaporation, leading to more down pouring of water molecules. This has caused an increased duration of drought and increased water vapour (Karl et al., 2009). A study has shown that solar energy production output is at its minimum during rainy weather (April – September) (Okoye and Taylan, 2017; Uko et al., 2016). Also, solar PVs frames can be affected if water enters their frames. In extension CSP will be affected because of rainfall; and temperature drops.

4.4. Sunlight

The sun emits energy from its disk in form of light and heat, various conditions can affect the reception of this energy on the surface of the earth. Our focus in the section is visible light, one of the three relevant bands or ranges of the EM spectrum alongside infrared and ultraviolet (UV) radiation, encompassing about 43% of the total solar radiation received. Light (in form of photons) and not temperature is important for the photoelectric effect in PVs, and a region that can capitalize on this either through perfect conditions or optimizing the PVs through inclination or specific design/technology will benefit. Nigeria has a great sunlight reception and research in Nigeria has proven that the visible portion of the solar spectrum influences the performance of solar panels far more than infra-red light (Ogherohwo et al., 2015). The long sunshine hours in Nigeria proves that in addition with the optimization of solar panel angles (manually or automatically), visible light received can be utilized for solar energy development.

4.5. Wind

Wind energy as an RE resource is one of the most utilized.

Figure 3 showed that power generated from wind energy is even higher than that of solar energy in Africa. Globally speaking, investments in wind energy development is only

slightly led by solar energy (

Figure 4). This shows that wind energy is a significant RE resource with sustainable results in curbing climate change (Owusu and Asumadu-Sarkodie, 2016). Wind power generation systems can be included as part of hybrid PV systems to complement for consistent energy production; this is one of importance of hybrid systems (Nelson et al., 2006; Su et al., 2010). Finally, it can be concluded that solar PV systems can be affected by strong winds, leading to equipment destruction.

4.6. Relationship Between Climatic Variables, Climate Change and Solar Energy Development:

We see that climatic parameters such as precipitation, temperature variation/global warming, cloud cover, sunlight, and wind have an effect on solar energy development. The phenomenon of climate change is a threat to life existence, energy and power generation. Hence the drive to mitigate climate change and global warming needs to be intensified.

Figure 11 shows a flowchart of the relationship between climate change and sustainable development. Direct carbon emission is the most significant cause of

climate change through the consistent use of

non-renewable energy; this has its effect on

air quality, economic and financial sustainability (especially when fossil fuel prices fluctuate). Naturally, the emitted carbon into the atmosphere is almost equal to the carbon absorbed by natural processes (the carbon cycle).

Although naturally emitted carbon compounds (CO2, methane, etc.) are way above anthropogenic emissions per year (750 gigatons compared to a meagre 29 gigatons), anthropogenic emissions (released outside the carbon cycle) bring about a net-imbalance in atmospheric carbon and makes a major difference in climate change and contributes to more GHGs and resulting in earth warming.

Climatic variables outlined in the figure like

cloud cover, temperature, sunlight, wind, precipitation all contribute to, and are affected by climate change (a feedback mechanism). Although these aforementioned climatic variables contribute to climate change, curbing or utilizing them can lead to sustainable

renewable energy adoption like

solar, geothermal, wind, biomass, and hydropower (shown in

Figure 11). Only

solar and geothermal energies are our concern because proper utilization, research and investments of these energies leads to

solar energy development, bringing about

sustainable development.

This sustainable development from solar energy will seek to solve the climatic problem by direct emission reduction through the utilization and improvement of the technologies and recent developments outlined in the next section. NETs and CCS are other methods sustainable development that do not directly relate to solar energy utilization. Applying solar powered grids or other hybrid grid systems for NETs and CCS is possible. However, using hybrid powered grids that use fossil fuels will nullify the advantage from carbon storage and extraction from the atmosphere. Factors have to be considered before adopting CCS and NETs; their process simply have to be carbon friendly.

The government, agencies, organizations and everybody needs to collaborate to mitigate climate change and global energy before we all drown, starve or be roasted by our hands (anthropogenic activities). From this section, we can observe that the adverse effect of climate change and global warming may be underestimated and the interaction may be more than research have covered.

5. Solar Energy Utilization

Table 3.

Barriers to the utilization of solar energy in Nigeria .

Table 3.

Barriers to the utilization of solar energy in Nigeria .

| Barriers |

Comments/Inferences |

References |

| Lack of consistent utilization of environmental support programs |

Due to the increase in global climate change in developing countries, the need for consistent environmental support programs from the international community cannot be overemphasized. International community has shown interest in the long-term solar energy development in developing countries like Nigeria.

Supports from countries which come in the form of environmental support programs and history has shown that although Nigeria receives funds for this utilization (Figure 6), the funds are not properly managed and utilized. |

(Amankwah-Amoah, 2015; Emodi and Ebele, 2016) |

| Manufacturing and initial investment/installation expenses |

The development of solar energy especially for solar PVs require huge expenses for sustainability and also a high cost of the initial investment.

Even when investors know that on the long term, adopting this will save costs, the high cost of initial investment cannot be overlooked easily. |

(Kannan and Vakeesan, 2016; Lutz et al., 2017; Ohunakin et al., 2014; Okedu et al., 2015; Olanipekun and Adelakun, 2020; Ugulu, 2019) |

| Climate Change/Global warming/Climatic barrier |

The performance of solar PVs is hugely influenced by the factors of the environment like sunshine intensity, cloud cover, etc. This is in contrast to the belief that factors like higher radiation is positive for solar PVs. |

(Kannan and Vakeesan, 2016; Mohammed et al., 2020) |

| Reduced data aggregation leading to lack of access to informative data |

Data aggregation is very important because it brings about access to data for quality research and proper information dissemination. Accurate data on the installed capacity and wattage of PVs for example can be very informative for future directions.

One of the major causes of lack of access to data has been the difficulty for average people to access quality data from weather stations and other recording stations. |

(Adeyanju et al., 2020) |

| Low level of awareness and socio-cultural habits |

In a country like Nigeria, where the awareness especially in rural areas is very low. Small businesses do not have the exposure to utilize solar energy in form of a hybrid electricity generating source. This has proven to be financially viable on the long term. |

(Kannan and Vakeesan, 2016; Ohunakin et al., 2014; Okedu et al., 2015; Olanipekun and Adelakun, 2020; Ugulu, 2019) |

| Pollution |

Solar cells which are made up of chemicals can pollute the environment when they are not properly disposed. This has proven to be a challenge for manufacturers. Air pollutions from aerosol can cause solar radiation from reaching the PV cells (diffuse radiation) |

(Kannan and Vakeesan, 2016) |

| Inconsistent production leading to lack of reliability |

The variation of solar radiation through seasons in a year and of hours in a day makes the power production and supply inconsistent. For the avenge man that has a low understanding of the combination of other energy sources to the solar grid, their interest is minimal |

(Kannan and Vakeesan, 2016; Mohammed et al., 2020; Ohunakin et al., 2014) |

| Amount of devices required |

For the effective generation of electrical power especially from solar PVs, a lot of devices are required. For example, solar PVs produce direct current (DC) and most domestic and industrial applications require alternating current (AC), this will require charge controller devices as well as inverters |

(Kannan and Vakeesan, 2016) |

| Environmental laws and regulations and lack of strong political support |

Government laws and policies is a major factor in the proper application of new technologies and innovations in solar energy.

Supports from the government should come in subsidies, and also set laws on the proper allocation and unbiased distributions of funds. The Renewable Energy Master Plan (REMP) was brought up by the Energy commission of Nigeria (ECN).

The right policies will bring that attraction of domestic and international investments. The room for improvement is obvious and should be viewed as something positive. |

(Elum and Momodu, 2017; Emodi and Ebele, 2016; Lutz et al., 2017; Mohammed et al., 2020; Nwokocha et al., 2018; Ohunakin et al., 2014; Okedu et al., 2015; Olanipekun and Adelakun, 2020; Ozoegwu et al., 2017) |

| Unreliability of the grid |

Poor maintenance of the national grid has made them obsolete for long term production. |

(Ohunakin et al., 2014) |

| Ineffective quality control of products |

Quality control involves the proper control and standardization of products. The lack of proper standards in solar energy products in Nigeria has been identified as a major institutional challenge for RE adoption. Products exists without trademark certificates and even a brand name. This creates room for a large number of sub-standards products in the market, leading to lack of trust from the public in this technology. |

(Ohunakin et al., 2014; Olanipekun and Adelakun, 2020) |

| Insecurity and vandalism of Solar Plant infrastructure |

The majority of locations where solar energy technology has been adopted on a large scale has become a home for military insurgency. These areas are majorly located in the northern region of Nigeria where the intensity of irradiation received is quite high. |

(Adeyanju et al., 2020; Ohunakin et al., 2014) |

| Competition with land uses |

When a land that is suitable and to be used by the government for large scale solar energy adoption is not owned by the government, it poses as a major problem for initial investments. Securing permits for land areas that are not owned by you may prove hectic as not all locations have been proven to be financially viable for its adoption due to factors like altitude, wind, rainfall, security, etc. |

(Ohunakin et al., 2014) |

| Technical know-how/limited human capacity (capital) development |

The education sector still remains a challenge in a developing country like Nigeria Solar energy development requires proper training for sustainable utilization. The National University Commission (NUC) has been suggested to RE education in the curriculum of Nigeria schools. Howbeit, Getting educated in this area has been made easier with some private firms offering it at a price. |

(D. Abdullahi et al., 2017; Abdullahi et al., 2021; Amankwah-Amoah, 2015; Okedu et al., 2015; Okoye et al., 2016; Olanipekun and Adelakun, 2020) |

| Lack of widespread institutional investment and development |

The private sector is a very key part of any country’s development process. This is true because governments have consistently not proven to be consistent in adoption.

Lack of widespread institutional involvement in solar energy development will bring about lack of quality research centers, and all advantages that the private sector can bring into it. Majority of the research that is carried in Nigeria by Nigerians are not invested in enough to make any noticeable impact. The growth process has been slow and steady. |

(Okoye et al., 2016) |

| Overreliance on fossil fuels |

The ever-increasing percentage of energy production from fossil fuels has caused Nigeria to be over dependent on energy from this source. The fact that the country exports crude oil makes her comfortable in this position. This has been major barrier as fossil fuels have been the easy way out from the ‘challenging’ obstacles that comes from the sustainable electricity generation from solar energy. |

(Adeyanju et al., 2020) |

5.1. Barriers to the Utilization of Solar Energy in Nigeria

The challenges faced by solar energy in Nigeria has been outlined in

Table 2. In spite of the good solar radiation reception by major parts of the region, it takes a lot of dedication and optimization to convert this renewable resource into electrical power. Sixteen (16) barriers to the proper utilization of solar energy in Nigeria has been presented in

Table 3. One of the major and most significant problems of its utilization is the poor structuring and implementation of government policies. The environmental laws from the government has gone a long way to affect this utilization as government laws cannot be ignored in a development of a region. Proper allocation and utilization of funds for environmental support programs by international sources (Emodi and Ebele, 2016) for example, is one of the key end goals of some policies because the issue of financial constraints is a consistent barrier. The renewable energy master plan (REMP) was formed by the energy commission of Nigeria (ECN) (Ajayi and Ajayi, 2013; Akuru and Okoro, 2010; Emodi and Ebele, 2016; UNDP, 2005; Williams et al., 2019) for the purpose of establishing short, medium and long term RE goals. However most of the medium and short term goals have not been reached, this calls for proper revision of the REMP.

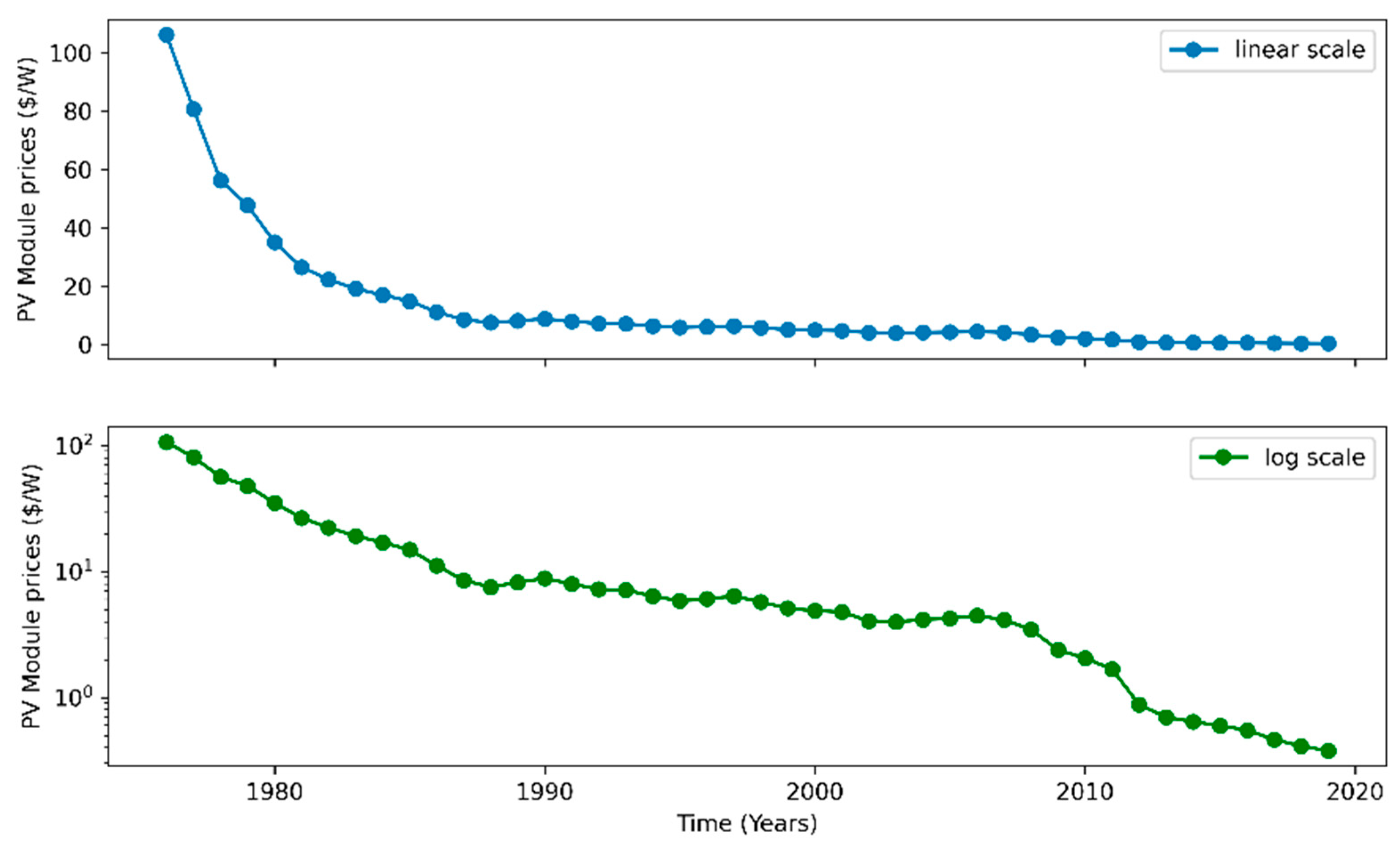

Finance has been identified as a major barrier to the utilization of solar energy technologies, but

Figure 7 shows that the global prices of PV modules is consistently reducing. The trend has been displaced in its linear and logarithmic scale to buttress on the consistent price reduction in US dollars for every wattage of energy produced.

Another major barrier as seen from the Table is the meagre human capital development. It has been recommended that the inclusion of the application of solar energy and RE at large in the curriculum by the National University Commission (NUC) will be needful; in extension, the lack of the inclusion of the private sector has proven as a major barrier also. This problem is directly affected by government policies which do not favour investments and research from the private sector. Related to proper research – apart from funding, data aggregation is a major factor. Proper data has proven to be important in models like the SAM (Elinwa et al., 2021), BIPV systems (Elinwa et al., 2021; Chigbogu Godwin Ozoegwu and Akpan, 2021) and in application in techniques like the applied geostatistics technique (Chiemelu et al., 2021). However, the availability of data provides information for future research, this has not been consistently made available in Nigeria. Most of the data that are available are difficult to access and are not available in online repositories unlike some developed countries that make some data freely available.

All these explained above and the barriers listed in

Table 2 leads to continuous problem of overreliance on fossil fuels. As long as the barriers outlined are not tackled, even with Nigeria’s high solar irradiation reception, the nation will always find an easy way out by settling for fossil fuels especially when she is blessed with large amount of crude oil.

Table 4.

Drivers to the utilization of solar energy in Nigeria .

Table 4.

Drivers to the utilization of solar energy in Nigeria .

| Drivers |

Inferences |

References |

| Energy Demand |

With the population in Nigeria expected to be ever increasing, a consistent demand on fossil fuels will eventually hit a brick wall. This keeps the region on its toes for the proper application of renewables like solar energy. The major drivers for energy demand are population growth and all round national development. With an estimated average rate of population growth capped at about 3.86%, long term energy demand and utilization cannot be trivialized. |

(Dahiru Abdullahi et al., 2017; Ohunakin et al., 2014; Ugulu, 2019) |

| Job creation |

Solar energy utilization will promote jobs in the area and create opportunities where there will be developments. Jobs could arise in areas including research and development, construction and management of PV and CSP devices, repairs and maintenance, etc. |

(Dahiru Abdullahi et al., 2017; Ohunakin et al., 2014) |

| GHG reduction/Climate change avoidance |

Climate change is arguably the highest driver of solar energy, at least on a global scale. The global funds received for solar energy development are mostly driven by the need to avoid GHG emissions in the atmosphere.

The consistent use of fossil fuels will bring about an increase in GHGs in the atmosphere, leading to an average increase in the global surface temperature and a sea level rise of a region like Nigeria. This will not only affect temperature, but other meteorological variables like, rainfall, precipitation, humidity as a result of this compounding effect. The application of solar energy can reduce this compounding effect notably. |

(Dahiru Abdullahi et al., 2017; Bello Yusuf and Bello, 2020; Ohunakin et al., 2014) |

| Rural electrification |

Nigeria has a lot of rural locations that are not connected to the national grid. Most consistent electrical power generated in those regions have been from renewables. The rural communities represents the highest potential to show the growth of solar energy in the country and this is enough motivation |

(Ohunakin et al., 2014) |

| The Electric Power Sector Reform Act (EPSRA) |

This Act was signed into law in 2005 by President Olusegun Obasanjo. The Act allowed private individuals and companies to take over the functions, liability and assets of the National authorities that produce electricity. This Act has empowered young entrepreneurs specially to own and invest in standalone power generation.

The Act lead to the avoidance of some long and unnecessary processes to get approval for investment and utilization. The maximum power that can be produced in a particular site without a license was kept at 1000KW. Policies like this will improve the adoption of RE by the general public and in extension, encourage research and development in the area. |

(Amankwah-Amoah, 2015; Ohunakin et al., 2014; Okoye and Taylan, 2017; Ugulu, 2019) |

| Reliable energy supply |

Even with the fact that Nigeria is an oil producing nation, majority of the regions complain of inconsistent power supply from the national grid.

This development has even caused some private organizations and households to invest in solar energy for the long-term. Energy production fluctuations from the national grid is a huge motivation because energy from solar energy can be personally managed, tracked and better forecasted. |

(Ugulu, 2019) |

| Long-term energy cost savings |

Analysis of the long term financial viability of solar energy utilization in Nigeria shows that on the long run, and with the identification of exact locations with great potential, the energy cost savings for solar energy far outweighs that of the conventional energy from fossil fuels. One factor that contributes to the lack of utilization is the high initial investment/installation cost. In spite of this, long term forecast shows that solar energy and RE utilization saves money more than fossil fuels.

A clear proof of this is the inclusion of solar energy installation in the long-term budget of institutions like major banks in the nation. |

(Njoku and Omeke, 2020; Saibu and Omoju, 2016; Tunji-Olayeni et al., 2020; Ugulu, 2019) |

5.2. Drivers to the Utilization of Solar Energy in Nigeria

Climate change has been the most notable and widely accepted driver for the utilization of solar energy around the world. At the mention of solar energy or any renewable, the idea of climate change mitigation comes to mind. Solar energy has been identified as the panacea to the electricity generation crisis and lacunae in the nation (Emmanuel P. Agbo et al., 2021a) with its ability to create sustainable power for rural electrification and small businesses.

Table 4 outlines some motivations for this adoption, drawn out from an empirical review of various studies and facts. GHGs are emitted when a region becomes over dependent on fossil fuels, and with energy demand outlined as one of the major drivers of solar energy adoption, slight complacency in this positive motive could lead to an increase in the total power generated from fossil fuels. Creation of policies like the Electric Power Sector Reform Act (EPSRA) which was created in 2005 and explained in

Table 4 can cause a positive ripple effect.

Another motivation which was not listed in the table is the fact that Nigeria is located at a latitude close to the equator, ultimately leading to the abundance of solar irradiance (Emmanuel P. Agbo et al., 2021a; Idowu et al., 2013; Ohunakin et al., 2013); optimum tilt angles has be easily determined for various locations to achieve maximum power generation (Idowu et al., 2013; Olatomiwa et al., 2016; Olusola et al., 2020).

Others areas where Nigeria’s solar energy adoption could be positively affected are the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Research conducted in Pakistan by (Qamar et al., 2022) relates to Nigeria’s situation and shows that the size of these enterprises, the apparent ease of use of the solar energy technology, and reliability are the top three (3) motivators for the adoption is MSMEs. All these factors are increasing in Nigeria.

Other motivators include international funding and support (

Figure 6), quiet operation, convenience, perceived overbilling from the national energy grid, marketing purposes, etc. (Soneye and Daramola, 2012; Ugulu, 2019).

5.3. Research Trends, Knowledge Gaps, Recommendations and Prospects

From this review, research trends have been observed as well as a few knowledge gaps that could guide future researchers to quality research.

As observed in several studies that were conducted, one major hindrance to the progress of solar energy adoption is the availability of consistent data to track the utilization progress. This problem was buttressed by (Adeyanju et al., 2020) and the recent past has not shown the importance of data in solar energy research in Nigeria.

Although a lot of research has been done to buttress the effect of climatic variables on Solar energy, it was observed that the long term knowledge on the effects of these variables like relative humidity, ambient temperature, solar radiation, rainfall, and cloud cover, have not been studied on the long term and compared to the long term progression of solar energy development in Nigeria. This brings us back to our data availability problem as previously mentioned. More studies have been focused on policies that should be enforced in other to curb the barriers that were identified and take advantage of the drivers that were identified. Regardless, little progress has been made on the development of the solar energy sector to show tangible outcome.

The region is more focused on actions for climate change mitigation than on solar energy utilization; this can be clearly seen from the increasing policies to reduce GHG emissions which does not tally to the actions taken to make sure that solar energy utilization is achieved. Research could be carried out to demystify this problem. Relating to industry policies, the Federal Government has instituted various climate change related policies aimed at combating climate change and often these policies have been ineffectual as their outcomes have been noted as below goal margins. Many of these policies need to researched and reviewed in order to see what specific results have been obtained from their implementation and how they could possibly be restructured for better efficacy.

For long term goals to be achieved, there must be evidence of progress. In this case, that is simply the reduction in the percentage of carbon emission. Gas has been tagged the future of the fuel industry and an extensive study on it is of great importance. Although it is still termed a ‘fossil fuel’, natural gas is relatively clean when combustion is carried out, having less CO2 emissions than coal and oil by 45% and 30% respectively; it is quite cheap and more available (Akansu et al., 2004). However little of this resource is implemented in power generation and although it’s a fossil fuel, development and research have to be consistently carried out to encourage its usage and progress to a carbon-free environment

The GHG emissions have been certified to contribute greatly to climatic variations, several protocols and mitigation schemes have been initiated to regulate its release into the atmosphere (Ahmed Ali et al., 2020; Edomah, 2016). However, research into how Nigeria can coordinate selling its carbon emissions for agricultural and other industrial purposes is lacking. A deep understanding of the importance and structure of a good carbon credit system requires an in-depth study.

6. Conclusion

Solar energy is arguably the RE that is being given the most public attention because virtually all the energy that we have been using, directly or indirectly, comes from the sun. Solar energy and RE in general have been consistently proposed to be one of the major solutions to the mitigation of climate change, either as a direct application that will lead to emission reduction, or indirect applications for carbon storage/sequestration and negative emission technologies. In spite of this, the effect of climate change can have a positive or negative effect on renewable energy and ultimately solar energy development; this review highlighted this with Nigeria as a case study. Results were gathered and presented.

From the study, it is obvious that solar energy is the most financially and generally supported renewable energy technology globally, this is because if its great potential for energy production and its relation with other renewables. For Nigeria, the difference between the climate conditions across various regions brings about ecological effects in areas like agriculture, health, transportation, forestation, etc. With an over-dependence on fossil fuels even for economic growth, emission reduction will be slow, but achievable. In order to ensure rapid improvement in RE, policies have been consistently improved to prevent temperature increases of up to 1.5o °C to 2o.c Findings show that Nigeria receives huge financial investments to make this adoption a possibility. With a reducing percentage or share of electricity production from renewables since the turn of the century, applications and developments have to progress from plans to actions; areas like agriculture, medicine, waste management, businesses and other large-scale applications were identified.

Regarding the effects of climate on solar energy development, a feedback mechanism was identified, where a lack of increasing solar energy adoption could lead to increased usage of nonrenewable energy, causing environmental issues. Conversely, climate changes/changes in the long-term trends of climatic variables like wind, sunlight, temperature, precipitation, and cloud cover also show effects (positive and/or negative) on solar energy development. All these were outlined with a vision of sustainable energy and development in mind.

It is forecasted that solar energy adoption will grow in Nigeria, especially after the drivers and barriers to their utilization were presented to show a possibility of taking advantage of this feedback mechanism, laying aside fossil fuels for a more sustainable future.

Author Contributions

IIO and EPA: Conceptualization, Data Curation and analysis, Methodology, Software; Visualization, Writing - original draft. GCO and EGN: Writing - original draft. GCE: Writing – review and editing, Resources, Design. NOO: Project administration, Writing – review and editing, Supervision

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request

Code Availability

Codes for visualization will be made available on request

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations:

| RE |

Renewable Energy |

| GHG(s) |

Greenhouse gas(es) |

| CCS |

Carbon Capture and Sequestration/Storage |

| NET(s) |

Negative Emission Technology(ies) |

| PV(s) |

Photovoltaic(s) |

| CSP |

Concentrated Solar Power |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| AR4 |

Fourth Assessment Report |

| CNG |

Compressed Natural Gases |

| OSH |

Occupational Safety and Health |

| CER(s) |

Certified Emission Reduction(s) |

| CDM |

Clean Development Mechanism |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| EM |

Electromagnetic |

| NiMet |

Nigerian Meteorological Agency |

| TWh |

terawatt-hours |

| USD |

United States Dollars |

| BIPV |

Building Integrated Photovoltaic |

| SAM |

System Advisor Model |

| NPV |

Net Present Value |

| DNI |

Direct Normal Irradiation |

| HOMER |

Hybrid Optimization Model for Electric Renewable |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| DC |

Direct Current |

| AC |

Alternating Current |

| REMP |

Renewable Energy Master Plan |

| ECN |

Energy Commission of Nigeria |

| NUC |

National University Commission |

| KW |

Kilowatts |

| EPSRA |

Electric Power Sector Reform Act |

| MSMEs |

Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises |

References

- Abdulkadir, A. , Lawal, A.M., Muhammad, T.I., 2017. Climate change and its implications on human existence in Nigeria: a review. Bayero Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 10, 152–158.

- Abdullahi, D. , Renukappa, S., Suresh, S., Oloke, D., 2021. Barriers for implementing solar energy initiatives in Nigeria: an empirical study. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment.

- Abdullahi, Dahiru, Suresh, S., Oloke, D., Renukappa, S., 2017. Solar Energy Development and Implementation in Nigeria: Drivers and Barriers, in: Proceedings of SWC2017/SHC2017. International Solar Energy Society, Abu Dhabi, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, D. , Suresh, S., Renukappa, S., Oloke, D., 2017. Key barriers to the implementation of solar energy in Nigeria: a critical analysis, in: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing, p. 012015.

- Adaramola, M.S. , Paul, S.S., Oyewola, O.M., 2014. Assessment of decentralized hybrid PV solar-diesel power system for applications in Northern part of Nigeria. Energy for Sustainable Development 19, 72–82. [CrossRef]

- Adebimpe, R.U. , 2011. Climate change related disasters and vulnerability: an appraisal of the Nigerian policy environment. Environmental Research Journal 5, 97–103.

- Adewuyi, A. , 2020. Challenges and prospects of renewable energy in nigeria: a case of bioethanol and biodiesel production. Energy Reports 6, 77–88.

- Adeyanju, G.C. , Osobajo, O.A., Otitoju, A., Ajide, O., 2020. Exploring the potentials, barriers and option for support in the Nigeria renewable energy industry. Discov Sustain 1, 7. [CrossRef]

- Agbo, E.P. , 2021. The role of statistical methods and tools for weather forecasting and modeling, in: Weather Forecasting. IntechOpen, pp. 3–22.

- Agbo, Emmanuel P., Edet, C.O., Magu, T.O., Njok, A.O., Ekpo, C.M., Louis, H., 2021a. Solar energy: A panacea for the electricity generation crisis in Nigeria. Heliyon 7, e07016.

- Agbo, E.P. , Ekpo, C.M., 2021. Trend analysis of the variations of ambient temperature using Mann-Kendall test and Sen’s estimate in Calabar, southern Nigeria, in: Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, p. 012016.